Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Event horizon

View on Wikipedia

| General relativity |

|---|

|

In astrophysics, an event horizon is a boundary beyond which events cannot affect an outside observer. Wolfgang Rindler coined the term in the 1950s.[1]

In 1784, John Michell proposed that gravity can be strong enough in the vicinity of massive compact objects that even light cannot escape.[2] At that time, the Newtonian theory of gravitation and the so-called corpuscular theory of light were dominant. In these theories, if the escape velocity of the gravitational influence of a massive object exceeds the speed of light, then light originating inside or from it can escape temporarily but will return. In 1958, David Finkelstein used general relativity to introduce a stricter definition of a local black hole event horizon as a boundary beyond which events of any kind cannot affect an outside observer, leading to information and firewall paradoxes, encouraging the re-examination of the concept of local event horizons and the notion of black holes. Several theories were subsequently developed, some with and some without event horizons. One of the leading developers of theories to describe black holes, Stephen Hawking, suggested that an apparent horizon should be used instead of an event horizon, saying, "Gravitational collapse produces apparent horizons but no event horizons." He eventually concluded that "the absence of event horizons means that there are no black holes – in the sense of regimes from which light can't escape to infinity."[3][4]

Any object approaching the horizon from the observer's side appears to slow down, never quite crossing the horizon.[5] Due to gravitational redshift, its image reddens over time as the object moves closer to the horizon.[6]

In an expanding universe, the speed of expansion reaches — and even exceeds — the speed of light, preventing signals from traveling to some regions. A cosmic event horizon is a real event horizon because it affects all kinds of signals, including gravitational waves, which travel at the speed of light.

More specific horizon types include the related but distinct absolute and apparent horizons found around a black hole. Other distinct types include:

- The Cauchy and Killing horizons.

- The photon spheres and ergospheres of the Kerr solution.

- Particle and cosmological horizons relevant to cosmology.

- Isolated and dynamical horizons, which are important in current black hole research.

Cosmic event horizon

[edit]

In cosmology, the event horizon of the observable universe is the largest comoving distance from which light emitted now can ever reach the observer in the future. This differs from the concept of the particle horizon, which represents the largest comoving distance from which light emitted in the past could reach the observer at a given time. For events that occur beyond that distance, light has not had enough time to reach our location, even if it was emitted at the time the universe began. The evolution of the particle horizon with time depends on the nature of the expansion of the universe. If the expansion has certain characteristics, parts of the universe will never be observable, no matter how long the observer waits for the light from those regions to arrive. The boundary beyond which events cannot ever be observed is an event horizon, and it represents the maximum extent of the particle horizon.

The criterion for determining whether a particle horizon for the universe exists is as follows. Define a comoving distance dp as

In this equation, a is the scale factor, c is the speed of light, and t0 is the age of the Universe. If dp → ∞ (i.e., points arbitrarily as far away as can be observed), then no event horizon exists. If dp ≠ ∞, a horizon is present.

Examples of cosmological models without an event horizon are universes dominated by matter or by radiation. An example of a cosmological model with an event horizon is a universe dominated by the cosmological constant (a de Sitter universe).

A calculation of the speeds of the cosmological event and particle horizons was given in a paper on the FLRW cosmological model, approximating the Universe as composed of non-interacting constituents, each one being a perfect fluid.[7][8]

Apparent horizon of an accelerated particle

[edit]

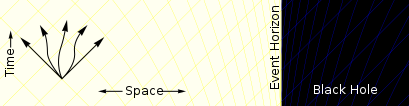

If a particle is moving at a constant velocity in a non-expanding universe free of gravitational fields, any event that occurs in that Universe will eventually be observable by the particle, because the forward light cones from these events intersect the particle's world line. On the other hand, if the particle is accelerating, in some situations light cones from some events never intersect the particle's world line. Under these conditions, an apparent horizon is present in the particle's (accelerating) reference frame, representing a boundary beyond which events are unobservable.

For example, this occurs with a uniformly accelerated particle. A spacetime diagram of this situation is shown in the figure to the right. As the particle accelerates, it approaches, but never reaches, the speed of light with respect to its original reference frame. On the spacetime diagram, its path is a hyperbola, which asymptotically approaches a 45-degree line (the path of a light ray). An event whose light cone's edge is this asymptote or is farther away than this asymptote can never be observed by the accelerating particle. In the particle's reference frame, there is a boundary behind it from which no signals can escape (an apparent horizon). The distance to this boundary is given by , where a is the constant proper acceleration of the particle.

While approximations of this type of situation can occur in the real world[citation needed] (in particle accelerators, for example), a true event horizon is never present, as this requires the particle to be accelerated indefinitely (requiring arbitrarily large amounts of energy and an arbitrarily large apparatus).

Interacting with a cosmic horizon

[edit]In the case of a horizon perceived by a uniformly accelerating observer in empty space, the horizon seems to remain a fixed distance from the observer no matter how its surroundings move. Varying the observer's acceleration may cause the horizon to appear to move over time or may prevent an event horizon from existing, depending on the acceleration function chosen. The observer never touches the horizon and never passes a location where it appeared to be.

In the case of a horizon perceived by an occupant of a de Sitter universe, the horizon always appears to be a fixed distance away for a non-accelerating observer. It is never contacted, even by an accelerating observer.

Event horizon of a black hole

[edit] Far away from the black hole, a particle can move in any direction. It is only restricted by the speed of light. |

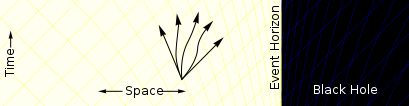

Closer to the black hole spacetime starts to deform. In some convenient coordinate systems, there are more paths going towards the black hole than paths moving away.[Note 1] |

Inside the event horizon all future time paths bring the particle closer to the center of the black hole. It is no longer possible for the particle to escape, no matter the direction the particle is traveling. |

One of the best-known examples of an event horizon derives from general relativity's description of a black hole, a celestial object so dense that no nearby matter or radiation can escape its gravitational field. Often, this is described as the boundary within which the black hole's escape velocity is greater than the speed of light. However, a more detailed description is that within this horizon, all lightlike paths (paths that light could take) (and hence all paths in the forward light cones of particles within the horizon) are warped so as to fall farther into the hole. Once a particle is inside the horizon, moving into the hole is as inevitable as moving forward in time – no matter in what direction the particle is travelling – and can be thought of as equivalent to doing so, depending on the spacetime coordinate system used.[10][9][11][12]

The surface at the Schwarzschild radius acts as an event horizon in a non-rotating body that fits inside this radius (although a rotating black hole operates slightly differently). The Schwarzschild radius of an object is proportional to its mass. Theoretically, any amount of matter will become a black hole if compressed into a space that fits within its corresponding Schwarzschild radius. For the mass of the Sun, this radius is approximately 3 kilometers (1.9 miles); for Earth, it is about 9 millimeters (0.35 inches). In practice, however, neither Earth nor the Sun have the necessary mass (and, therefore, the necessary gravitational force) to overcome electron and neutron degeneracy pressure. The minimal mass required for a star to collapse beyond these pressures is the Tolman–Oppenheimer–Volkoff limit, which is approximately three solar masses.

According to the fundamental gravitational collapse models,[13] an event horizon forms before the singularity of a black hole. If all the stars in the Milky Way would gradually aggregate towards the galactic center while keeping their proportionate distances from each other, they will all fall within their joint Schwarzschild radius long before they are forced to collide.[4] Up to the collapse in the far future, observers in a galaxy surrounded by an event horizon would proceed with their lives normally.

Black hole event horizons are widely misunderstood. Common, although erroneous, is the notion that black holes "vacuum up" material in their neighborhood, where in fact they are no more capable of seeking out material to consume than any other gravitational attractor. As with any mass in the universe, matter must come within its gravitational scope for the possibility to exist of capture or consolidation with any other mass. Equally common is the idea that matter can be observed falling into a black hole. This is not possible. Astronomers can detect only accretion disks around black holes, where material moves with such speed that friction creates high-energy radiation that can be detected (similarly, some matter from these accretion disks is forced out along the axis of spin of the black hole, creating visible jets when these streams interact with matter such as interstellar gas or when they happen to be aimed directly at Earth). Furthermore, a distant observer will never actually see something reach the horizon. Instead, while approaching the hole, the object will seem to go ever more slowly, while any light it emits will be further and further redshifted.

Topologically, the event horizon is defined from the causal structure as the past null cone of future conformal timelike infinity. A black hole event horizon is teleological in nature, meaning that it is determined by future causes.[14][15][16] More precisely, one would need to know the entire history of the universe and all the way into the infinite future to determine the presence of an event horizon, which is not possible for quasilocal observers (not even in principle).[17][18] In other words, there is no experiment and/or measurement that can be performed within a finite-size region of spacetime and within a finite time interval that answers the question of whether or not an event horizon exists. Because of the purely theoretical nature of the event horizon, the traveling object does not necessarily experience strange effects and does, in fact, pass through the calculated boundary in a finite amount of its proper time.[19]

Interacting with black hole horizons

[edit]A misconception concerning event horizons, especially black hole event horizons, is that they represent an immutable surface that destroys objects that approach them. In practice, all event horizons appear to be some distance away from any observer, and objects sent towards an event horizon never appear to cross it from the sending observer's point of view (as the horizon-crossing event's light cone never intersects the observer's world line). Attempting to make an object near the horizon remain stationary with respect to an observer requires applying a force whose magnitude increases unboundedly (becoming infinite) the closer it gets.

In the case of the horizon around a black hole, observers stationary with respect to a distant object will all agree on where the horizon is. While this seems to allow an observer lowered towards the hole on a rope (or rod) to contact the horizon, in practice this cannot be done. The proper distance to the horizon is finite,[20] so the length of rope needed would be finite as well, but if the rope were lowered slowly (so that each point on the rope was approximately at rest in Schwarzschild coordinates), the proper acceleration (G-force) experienced by points on the rope closer and closer to the horizon would approach infinity, so the rope would be torn apart. If the rope is lowered quickly (perhaps even in freefall), then indeed the observer at the bottom of the rope can touch and even cross the event horizon. But once this happens it is impossible to pull the bottom of rope back out of the event horizon, since if the rope is pulled taut, the forces along the rope increase without bound as they approach the event horizon and at some point the rope must break. Furthermore, the break must occur not at the event horizon, but at a point where the second observer can observe it.

Assuming that the possible apparent horizon is far inside the event horizon, or there is none, observers crossing a black hole event horizon would not actually see or feel anything special happen at that moment. In terms of visual appearance, observers who fall into the hole perceive the eventual apparent horizon as a black impermeable area enclosing the singularity.[21] Other objects that had entered the horizon area along the same radial path but at an earlier time would appear below the observer as long as they are not entered inside the apparent horizon, and they could exchange messages. Increasing tidal forces are also locally noticeable effects, as a function of the mass of the black hole. In realistic stellar black holes, spaghettification occurs early: tidal forces tear materials apart well before the event horizon. However, in supermassive black holes, which are found in centers of galaxies, spaghettification occurs inside the event horizon. A human astronaut would survive the fall through an event horizon only in a black hole with a mass of approximately 10,000 solar masses or greater.[22]

Beyond general relativity

[edit]A cosmic event horizon is commonly accepted as a real event horizon, whereas the description of a local black hole event horizon given by general relativity is found to be incomplete and controversial.[3][4] When the conditions under which local event horizons occur are modeled using a more comprehensive picture of the way the Universe works, that includes both relativity and quantum mechanics, local event horizons are expected to have properties that are different from those predicted using general relativity alone.

At present, it is expected by the Hawking radiation mechanism that the primary impact of quantum effects is for event horizons to possess a temperature and so emit radiation. For black holes, this manifests as Hawking radiation, and the larger question of how the black hole possesses a temperature is part of the topic of black hole thermodynamics. For accelerating particles, this manifests as the Unruh effect, which causes space around the particle to appear to be filled with matter and radiation.

According to the controversial black hole firewall hypothesis, matter falling into a black hole would be burned to a crisp by a high energy "firewall" at the event horizon.

An alternative is provided by the complementarity principle, according to which, in the chart of the far observer, infalling matter is thermalized at the horizon and reemitted as Hawking radiation, while in the chart of an infalling observer matter continues undisturbed through the inner region and is destroyed at the singularity. This hypothesis does not violate the no-cloning theorem as there is a single copy of the information according to any given observer. Black hole complementarity is actually suggested by the scaling laws of strings approaching the event horizon, suggesting that in the Schwarzschild chart they stretch to cover the horizon and thermalize into a Planck length-thick membrane.

A complete description of local event horizons generated by gravity is expected to, at minimum, require a theory of quantum gravity. One such candidate theory is M-theory. Another such candidate theory is loop quantum gravity.

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ The set of possible paths, or more accurately the future light cone containing all possible world lines (in this diagram represented by the yellow/blue grid), is tilted in this way in Eddington–Finkelstein coordinates (the diagram is a "cartoon" version of an Eddington–Finkelstein coordinate diagram), but in other coordinates the light cones are not tilted in this way, for example in Schwarzschild coordinates they simply narrow without tilting as one approaches the event horizon, and in Kruskal–Szekeres coordinates the light cones don't change shape or orientation at all.[9]

References

[edit]- ^ Rindler, Wolfgang (1956-12-01). "Visual Horizons in World Models". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. 116 (6). [Also reprinted in General Relativity and Gravitation, 34, 133–153 (2002), doi: 10.1023/A:1015347106729]: 662–677. doi:10.1093/mnras/116.6.662. ISSN 0035-8711.

- ^ Michell, John (1784). "VII. On the means of discovering the distance, magnitude, &c. of the fixed stars, in consequence of the diminution of the velocity of their light, in case such a diminution should be found to take place in any of them, and such other data should be procured from observations, as would be farther necessary for that purpose. By the Rev. John Michell, B.D. F.R.S. In a letter to Henry Cavendish, Esq. F.R.S. and A.S". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London. 74. The Royal Society: 35–57. Bibcode:1784RSPT...74...35M. doi:10.1098/rstl.1784.0008. ISSN 0261-0523. JSTOR 106576.

- ^ a b Hawking, Stephen W. (2014). "Information Preservation and Weather Forecasting for Black Holes". arXiv:1401.5761v1 [hep-th].

- ^ a b c Curiel, Erik (2019). "The many definitions of a black hole". Nature Astronomy. 3: 27–34. arXiv:1808.01507. Bibcode:2019NatAs...3...27C. doi:10.1038/s41550-018-0602-1. S2CID 119080734.

- ^ Chaisson, Eric J. (1990). Relatively Speaking: Relativity, Black Holes, and the Fate of the Universe. W. W. Norton & Company. p. 213. ISBN 978-0393306750.

- ^ Bennett, Jeffrey; Donahue, Megan; Schneider, Nicholas; Voit, G. Mark (2014). The Cosmic Perspective. Pearson Education. p. 156. ISBN 978-0-134-05906-8.

- ^ Margalef-Bentabol, Berta; Margalef-Bentabol, Juan; Cepa, Jordi (21 December 2012). "Evolution of the cosmological horizons in a concordance universe". Journal of Cosmology and Astroparticle Physics. 2012 (12): 035. arXiv:1302.1609. Bibcode:2012JCAP...12..035M. doi:10.1088/1475-7516/2012/12/035. hdl:10016/39774. S2CID 119704554. Archived from the original on 8 December 2019. Retrieved 3 December 2013.

- ^ Margalef-Bentabol, Berta; Margalef-Bentabol, Juan; Cepa, Jordi (8 February 2013). "Evolution of the cosmological horizons in a universe with countably infinitely many state equations". Journal of Cosmology and Astroparticle Physics. 015. 2013 (2): 015. arXiv:1302.2186. Bibcode:2013JCAP...02..015M. doi:10.1088/1475-7516/2013/02/015. S2CID 119614479. Archived from the original on 8 December 2019. Retrieved 3 December 2013.

- ^ a b Misner, Thorne & Wheeler 1973, p. 848

- ^ Hawking, Stephen W.; Ellis, G.F.R. (1975). The Large Scale Structure of Space-Time. Cambridge University Press.[page needed]

- ^ Wald, Robert M. (1984). General Relativity. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0-2268-7033-5.[page needed]

- ^ Peacock, John A. (1999). Cosmological Physics. Cambridge University Press. doi:10.1017/CBO9780511804533. ISBN 978-0-511-80453-3.[page needed]

- ^ Penrose, Roger (1965). "Gravitational collapse and space-time singularities". Physical Review Letters. 14 (3): 57. Bibcode:1965PhRvL..14...57P. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.14.57.

- ^ Ashtekar, Abhay; Krishnan, Badri (2004). "Isolated and dynamical horizons and their applications". Living Reviews in Relativity. 7 (1): 10. arXiv:gr-qc/0407042. Bibcode:2004LRR.....7...10A. doi:10.12942/lrr-2004-10. PMC 5253930. PMID 28163644. S2CID 16566181.

- ^ Senovilla, José M. M. (2011). "Trapped surfaces". International Journal of Modern Physics D. 20 (11): 2139–2168. arXiv:1107.1344. Bibcode:2011IJMPD..20.2139S. doi:10.1142/S0218271811020354.

- ^ Mann, Robert B.; Murk, Sebastian; Terno, Daniel R. (2022). "Black holes and their horizons in semiclassical and modified theories of gravity". International Journal of Modern Physics D. 31 (9): 2230015–2230276. arXiv:2112.06515. Bibcode:2022IJMPD..3130015M. doi:10.1142/S0218271822300154. S2CID 245123647.

- ^ Visser, Matt (2014). "Physical observability of horizons". Physical Review D. 90 (12) 127502. arXiv:1407.7295. Bibcode:2014PhRvD..90l7502V. doi:10.1103/PhysRevD.90.127502. S2CID 119290638.

- ^ Murk, Sebastian (2023). "Nomen non est omen: Why it is too soon to identify ultra-compact objects as black holes". International Journal of Modern Physics D. 32 (14) 2342012: 2342012–2342235. arXiv:2210.03750. Bibcode:2023IJMPD..3242012M. doi:10.1142/S0218271823420129. S2CID 252781040.

- ^ Joshi, Pankaj; Narayan, Ramesh (2016). "Black Hole Paradoxes". Journal of Physics: Conference Series. 759 (1): 12–60. arXiv:1402.3055. Bibcode:2016JPhCS.759a2060J. doi:10.1088/1742-6596/759/1/012060. S2CID 118592546.

- ^ Misner, Thorne & Wheeler 1973, p. 824

- ^ Hamilton, Andrew J. S. "Journey into a Schwarzschild black hole". jila.colorado.edu. Archived from the original on 3 September 2019. Retrieved 28 June 2020.

- ^ Hobson, Michael Paul; Efstathiou, George; Lasenby, Anthony N. (2006). "11. Schwarzschild black holes". General Relativity: An introduction for physicists. Cambridge University Press. p. 265. ISBN 978-0-521-82951-9. Archived from the original on 2019-03-31. Retrieved 2018-01-26.

Further reading

[edit]- Misner, Charles W.; Thorne, Kip S.; Wheeler, John Archibald (1973). Gravitation (27. printing ed.). New York, NY: Freeman. ISBN 978-0-7167-0344-0.

- Hawking, Stephen W. (2001). The universe in a nutshell. New York: Bantam. ISBN 978-0-553-80202-3.

- Thorne, Kip S. (1994). Black holes and time warps: Einstein's outrageous legacy. The Commonwealth Fund Book Program. New York / London: Norton. ISBN 978-0-393-31276-8.

- Ashtekar, Abhay; Krishnan, Badri (2004). "Isolated and dynamical horizons and their applications". Living Reviews in Relativity. 7 (1): 10. arXiv:gr-qc/0407042. Bibcode:2004LRR.....7...10A. doi:10.12942/lrr-2004-10. ISSN 2367-3613. PMC 5253930. PMID 28163644.