Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

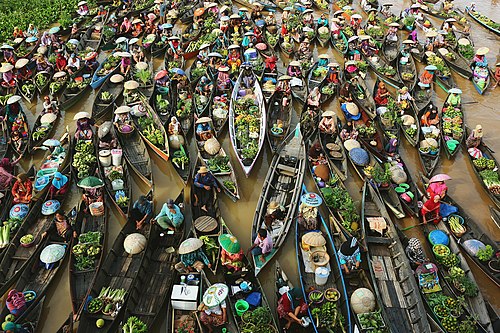

Floating market

View on WikipediaThis article is missing information about history of the floating market in countries other than Thailand. (May 2022) |

A floating market is a market where goods are sold from boats. Originating in times and places where water transport played an important role in daily life, most floating markets operating today mainly serve as tourist attractions, and are chiefly found in Myanmar, Thailand, Indonesia, Vietnam, Sri Lanka, Bangladesh, and India.

Bangladesh

[edit]The 200-year-old floating market at Kuriana in Swarupkati has become a tourist spot. Guava floating market is a unique market. Hundreds of tourists from home and abroad visit the place every day to enjoy the beauty of the market and its surrounding landscape.

Thailand

[edit]

In Thailand, floating markets (Thai: ตลาดน้ำ talāt nām lit. transl. water market) are well supported locally and mainly serve as tourist attractions.[1] One of their purposes is to allow domestic visitors and international tourists to be able to experience the culture of riverside shopping.

History

[edit]Historically,[2] the areas adjacent to the rivers were the first to be populated. Thus, most communities in Thailand were built at the sides of rivers. The waterways served as means of transportation and the center of economic activity, as well. Boats were mainly used for local and regional trade, bringing goods from those that produced to those that could barter and trade. Such ways of life of the riverside communities, especially in the Chao Phraya River Basin, increased the number of floating markets.

Floating markets became the hubs of the communities in the central plain of Thailand for centuries.[3] In the Ayutthaya Period (1350–1767), due to the existence of several adjoining canals that were suitable for trading, they helped to gain popularity for this type of market.

Early in the Rattanakosin Period (1782–1868), this kind of market was still lively with the crowds. Nonetheless, soon after the region grew and Bangkok began to develop, road and rail networks were increasingly constructed in place of the canals. This resulted in people choosing to travel by land instead of by water. Therefore, some of the floating markets were forced to move onto land, some were renovated, and some were closed down.

Originally, the term meaning floating market in Thai, used to be called (Thai: ตลาดท้องน้ำ tāː.làt tʰɔ̂ːŋ nâːm lit. transl. floor of the water market). Until in the reign of King Vajiravudh (Rama VI), therefore saying only talat nam.[4]

Notable floating markets

[edit]Amphawa floating market

[edit]

Amphawa floating market is not as large as Damnoen Saduak floating market[5] but it is more authentic, with visitors almost exclusively Thais. It is an evening floating market but some stalls are opened at noon too. The market operates on Friday, Saturday and Sunday from 1600 to around 2100 hrs. It is in Amphawa District, Samut Songkhram Province (72 km from Bangkok). Moreover, due to its popularity, the food stalls have grown from the riverbanks and stretched far into the surrounding buildings. Another popular activity in Amphawa District is to take a boat and watch the flickering fireflies at night, especially in the waxing-moon nights.

Damnoen Saduak floating market

[edit]Damnoen Saduak floating market in Damnoen Saduak District is undoubtedly the largest and most well-known floating market among Thai and foreign tourists. It is located in Ratchaburi Province, about 100 km southwest of Bangkok. The market is open every day from around 0630 to 1100 hr, but the best time to visit is in the early morning. The market is crowded with hundreds of vendors and purchasers floating in their small boats selling and buying agricultural products and local food, which are mostly brought from their own nearby orchards. It is a very attractive place for tourists to see the old style and traditional way of selling and buying goods.

Don Wai floating market

[edit]Don Wai floating market is not far from Bangkok, in Sam Phran District, Nakhon Pathom Province on the Tha Chin River. This market is famous for a variety of foods such as stewed Java barb in salty soup especially Chinese stewed duck. Moreover, it is not far from one of the most prominent temples of Nakhon Pathom, Wat Rai Khing, which can be reached by boat on the Tha Chin River.[6]

Khlong Hae floating market

[edit]Khlong Hae floating market is the first and only floating market in Southern Thailand presently. Located in Hat Yai District, Songkhla Province, it is unique in that it blends between Buddhist Thai and Muslim cultures.[7]

Kwan Riam floating market

[edit]Kwan Riam floating market is in Min Buri District, Bangkok, near Khlong Saen Saep; its name comes from the name of characters in a popular Thai romance-drama novel titled Plae Kao, as Khlong Saen Saep was used as the backdrop of this novel.

Taling Chan floating market

[edit]Taling Chan floating market, also in Bangkok is located near Khlong Chak Phra in front of Taling Chan District Office adjacent to the Southern Railway Line. The market is open only on Saturdays, Sundays, and public holidays. Visitors can also take a boat from here to other attractions in this area, such as other floating markets or pay homage to Luang Pho Dam, an ancient sacred Buddha image at a nearby Wat Chang Lek temple. The market is also one of six no-smoking areas in Bangkok's project in 2019.[8][9]

4 Region floating market

[edit]Si Pak Floating market or Pattaya Floating market. Another charm of Pattaya is the 4-region floating market, cultural and tourist attractions. It is the center of a variety of activities regarding Conservation of art and culture. 4 regions floating market had Collect all 4 good products here blended perfectly. The source of local handicrafts and cultural tourist attractions combined into one place, considered a new shopping area with unique selling points.[10][11]

Indonesia

[edit]

The floating markets in Indonesia are a collection of vendors selling various produce and product on boats. Floating markets initially are not created as tourist attractions, but as necessities in Indonesian cities that have large river especially in several cities and towns in Kalimantan and Sumatra. However, they have been promoted in the tourism itinerary, especially in Kalimantan cities. For example, the Siring floating market in Banjarmasin, and Lok Baintan floating market in Martapura are both located in South Kalimantan.

India

[edit]A floating market exists in Srinagar in Jammu and Kashmir on the Dal Lake that operates daily, with vendors selling produce grown on the banks of the lake.[12]

A floating 'mall' operates in the Kerala backwaters, offering subsidised rates on sales. Named Floating Triveni Super Store, it was launched in 2012 by the Kerala State Co-operative Consumers Federation.[13]

A floating market was opened in Patuli, Kolkata, on a canal adjacent to the Eastern Metropolitan Bypass in January 2018. It features more than 200 vendors and 100 boats selling fish, fruit and vegetables.[14] However, the market is struggling to stay open with declining sales.[15] The lighting used by the municipal authorities and shopkeepers is reported to have driven away migratory birds from the region.[16]

Vietnam

[edit]Floating markets (chợ nổi in Vietnamese) have existed in Vietnam for many generations. Archaeologists have found evidence that extensive trading networks likely existed in Vietnam's river deltas from as far back as 4,500 years ago.[17][18]

With a rich system of rivers, Mekong Delta is the place where many weekly floating markets take place. This is an opportunity for small traders to exchange goods, and tourists can experience with the locals. Some of the famous floating markets in this area are Cai Rang Market, Long Xuyen Market, Cai Be Market, etc.

Product categories

[edit]Produce and fruit

[edit]Ideally, the floating market's produce and fruit are normally grown from nearby gardens or local orchards.[19] Such produce comprises assorted tropical fruits[20] and vegetables, such as Guava, banana, jackfruit, rambutan, mango, pineapple, dragon fruit, carambola, fresh coconut, and durian.

Dishes

[edit]Local dishes are cooked and prepared by the vendors from their floating kitchens located on their boats. They offer various kinds of food ranging from traditional Thai meat to vegetarian dishes such as papaya salad (som tum). Boat noodles and traditional Thai dessert (khanom wan Thai) such as mango sticky rice and coconut rice dumplings (khanom krok) are also available for tasting.

Products

[edit]Hundreds of locally produced goods are available for purchase; bargaining is common. Examples of these types of merchandise include:

- Clothes

- Conical hats

- Crafted candles

- Handicrafts

- Paintings

- Post cards

- Thai silk

Gallery

[edit]-

Floating market in Cần Thơ, Vietnam, Mekong Delta.

-

Floating market around Cần Thơ, Vietnam.

-

Floating market in Phong Điền, Vietnam, Mekong Delta.

-

Muara Kuin floating market in Banjarmasin, South Kalimantan, Indonesia

-

Damnoen Saduak floating market is a floating market outside of Bangkok

-

Pettah Floating Market in Colombo, Sri Lanka

-

Lok Baintan floating market in Banjar Regency, South Kalimantan

-

Southern Railway Bridge over Taling Chan floating market

-

Taling Chan floating market

-

Pork satay boat hawker at Taling Chan floating market

-

Typical atmosphere of Taling Chan floating market

-

Hawker selling food to customer, Khlong Hae floating market, southern Thailand

-

Traditional Thai wooden houses and two Thai child's dolls at Ayothaya floating market, another renowned floating market in Thailand

References

[edit]- ^ Floating Market (Famous Wonders of the World Best Places to Visit See Travel Pictures Floating Market Comments)

- ^ History of Floating Markets (Around the World)

- ^ Floating Markets (Floating Markets)

- ^ Sanfah (2012-02-29). "พินิจนคร (Season 3) ตอน บางช้าง" [Pinijnakorn (Season3) ep Bang Chang]. TPBS (in Thai). Retrieved 2019-08-25.

- ^ Floating Markets (Floating Markets)

- ^ "WAT DON WAI FLOATING MARKET". TAT.

- ^ "5 Places to Visit in Hat Yai". go SHOPPING THAILAND.[permanent dead link]

- ^ "TALINGCHAN FLOATING MARKET". TAT. Archived from the original on 2016-02-26. Retrieved 2019-05-16.

- ^ "กทม.จัดพื้นที่ต้นแบบปลอดบุหรี่ 6 แห่ง หวังให้ ปชช.มีสุขภาพดี" [BKK organizes six no-smoking prototype areas, hoping for healthy people]. ASTV Manager (in Thai). 2019-05-31. Retrieved 2019-06-02.

- ^ รีวิวตลาดน้ำ 4 ภาคพัทยา โฉมใหม่!! ล่องเรือชมวิว ชิมของอร่อยหลักสิบ Pattaya

- ^ "Thailand Tourism Directory - Digital Tourism". Archived from the original on 2022-06-02. Retrieved 2020-06-29.

- ^ "Before Kolkata's floating market, did you know about these 2 floating markets of India?". India Today. 15 December 2017. Retrieved 22 June 2019.

- ^ "Floating Triveni store launched". The Hindu. 24 July 2011. Retrieved 22 June 2019.

- ^ Banerjee, Pritha (1 July 2018). "A reality check on India's first floating market in Kolkata". Free Press Journal. Retrieved 22 June 2019.

- ^ Mitra, Bishwabijoy (27 July 2018). "Kolkata's only floating market struggles to stay afloat - Times of India". The Times of India. Retrieved 22 June 2019.

- ^ Chaudhuri, Moumita (4 November 2018). "Birds disappear as India's first floating market flourishes". The Telegraph. Retrieved 22 June 2019.

- ^ "Archaeologists uncover ancient trading network in Vietnam -- ScienceDaily". ScienceDaily. November 26, 2021. Archived from the original on November 28, 2021. Retrieved May 26, 2022.

- ^ Frieman, Catherine J.; Piper, Phillip J.; Nguyen, Khanh Trung Kien; Tran, Thi Kim Quy; Oxenham, Marc (2017). "Rach Nui: ground stone technology in coastal Neolithic settlements of southern Vietnam". Antiquity. 91 (358). Antiquity Publications: 933–946. doi:10.15184/aqy.2017.71. ISSN 0003-598X. S2CID 164252301.

- ^ Floating Market (Famous Wonders of the World Best Places to Visit See Travel Pictures Floating Market Comments)

- ^ Floating Markets (Floating Markets)