Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Classical element

View on Wikipedia

| Classical elements |

|---|

The classical elements typically refer to earth, water, fire, air, and (later) aether which were proposed to explain the nature and complexity of all matter in terms of simpler substances.[1][2] Ancient cultures in Greece, Angola, Tibet, India, and Mali had similar lists which sometimes referred, in local languages, to "air" as "wind", and to "aether" as "space".

These different cultures and even individual philosophers had widely varying explanations concerning their attributes and how they related to observable phenomena as well as cosmology. Sometimes these theories overlapped with mythology and were personified in deities. Some of these interpretations included atomism (the idea of very small, indivisible portions of matter), but other interpretations considered the elements to be divisible into infinitely small pieces without changing their nature.

While the classification of the material world among the ancient Indians, Hellenistic Egyptians, and ancient Greeks into air, earth, fire, and water was more philosophical; scientists of the Middle Ages used practical, experimental observation to classify materials.[3] In Europe, the ancient Greek concept, devised by Empedocles, evolved into the systematic classifications of Aristotle and Hippocrates. This evolved slightly into the medieval system,[citation needed] and eventually became the object of experimental verification in the 17th century, at the start of the Scientific Revolution.[4]

Modern science does not support the classical elements to classify types of substances. Atomic theory classifies atoms into more than a hundred chemical elements such as oxygen, iron, and mercury, which may form chemical compounds and mixtures. The modern categories roughly corresponding to the classical elements are the states of matter produced under different temperatures and pressures. Solid, liquid, gas, and plasma share many attributes with the corresponding classical elements of earth, water, air, and fire, but these states describe the similar behaviour of different types of atoms at similar energy levels, not the characteristic behaviour of certain atoms or substances.

Hellenistic philosophy

[edit]| Part of a series on |

| Platonism |

|---|

|

| The Republic |

| Timaeus |

| Related articles |

| Related categories |

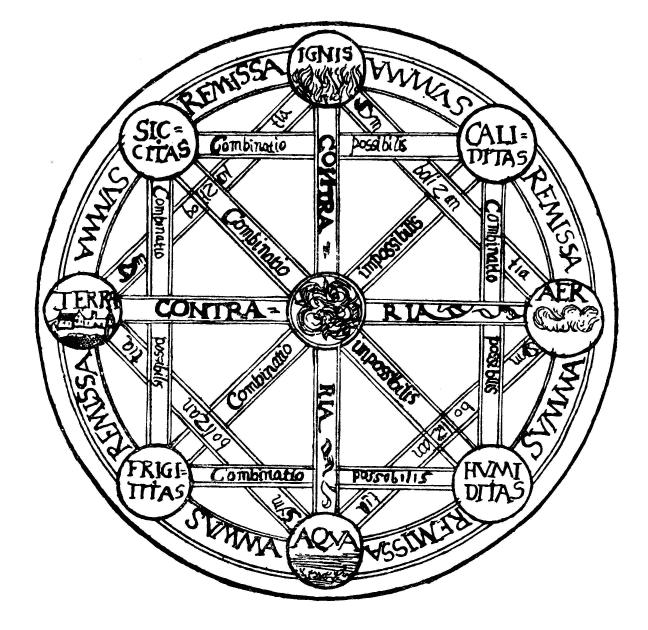

| Aristotelian elements and qualities |

Empedoclean elements |

The ancient Greek concept of four basic elements, these being earth (γῆ gê), water (ὕδωρ hýdōr), air (ἀήρ aḗr), and fire (πῦρ pŷr), dates from pre-Socratic times and persisted throughout the Middle Ages and into the Early modern period, deeply influencing European thought and culture.[5]

Pre-Socratic elements

[edit]Primordal element

[edit]

The classical elements were first proposed independently by several early Pre-Socratic philosophers.[6] Greek philosophers had debated which substance was the arche ("first principle"), or primordial element from which everything else was made. Thales (c. 626/623 – c. 548/545 BC) believed that water was this principle. Anaximander (c. 610 – c. 546 BC) argued that the primordial substance was not any of the known substances, but could be transformed into them, and they into each other.[7][5] Anaximenes (c. 586 – c. 526 BC) favoured air, and Heraclitus (fl. c. 500 BC) championed fire.[8]

Fire, earth, air, and water

[edit]The Greek philosopher Empedocles (c. 450 BC) was the first to propose the four classical elements as a set: fire, earth, air, and water.[9] He called them the four "roots" (ῥιζώματα, rhizōmata). Empedocles also proved (at least to his own satisfaction) that air was a separate substance by observing that a bucket inverted in water did not become filled with water, a pocket of air remaining trapped inside.[10]

Fire, earth, air, and water have become the most popular set of classical elements in modern interpretations. One such version was provided by Robert Boyle in The Sceptical Chymist, which was published in 1661 in the form of a dialogue between five characters. Themistius, the Aristotelian of the party, says:[11]

If You but consider a piece of green-Wood burning in a Chimney, You will readily discern in the disbanded parts of it the four Elements, of which we teach It and other mixt bodies to be compos'd. The fire discovers it self in the flame ... the smoke by ascending to the top of the chimney, and there readily vanishing into air ... manifests to what Element it belongs and gladly returnes. The water ... boyling and hissing at the ends of the burning Wood betrayes it self ... and the ashes by their weight, their firiness, and their dryness, put it past doubt that they belong to the Element of Earth.

Humorism (Hippocrates)

[edit]

According to Galen, these elements were used by Hippocrates (c. 460 – c. 370 BC) in describing the human body with an association with the four humours: yellow bile (fire), black bile (earth), blood (air), and phlegm (water). Medical care was primarily about helping the patient stay in or return to their own personal natural balanced state.[12]

Plato

[edit]

Plato (428/423 – 348/347 BC) seems to have been the first to use the term "element (στοιχεῖον, stoicheîon)" in reference to air, fire, earth, and water.[13] The ancient Greek word for element, stoicheion (from stoicheo, "to line up") meant "smallest division (of a sun-dial), a syllable", as the composing unit of an alphabet it could denote a letter and the smallest unit from which a word is formed.

Aristotle

[edit]

In On the Heavens (350 BC), Aristotle defines "element" in general:[14][15]

An element, we take it, is a body into which other bodies may be analysed, present in them potentially or in actuality (which of these, is still disputable), and not itself divisible into bodies different in form. That, or something like it, is what all men in every case mean by element.[16]

— Aristotle, On the Heavens, Book III, Chapter III

In his On Generation and Corruption,[17][18] Aristotle related each of the four elements to two of the four sensible qualities:

- Fire is both hot and dry.

- Air is both hot and wet (for air is like vapour, ἀτμὶς).

- Water is both cold and wet.

- Earth is both cold and dry.

A classic diagram has one square inscribed in the other, with the corners of one being the classical elements, and the corners of the other being the properties. The opposite corner is the opposite of these properties, "hot – cold" and "dry – wet".

Aether

[edit]Aristotle added a fifth element, aether (αἰθήρ aither), as the quintessence, reasoning that whereas fire, earth, air, and water were earthly and corruptible, since no changes had been perceived in the heavenly regions, the stars cannot be made out of any of the four elements but must be made of a different, unchangeable, heavenly substance.[19] It had previously been believed by pre-Socratics such as Empedocles and Anaxagoras that aether, the name applied to the material of heavenly bodies, was a form of fire. Aristotle himself did not use the term aether for the fifth element, and strongly criticised the pre-Socratics for associating the term with fire. He preferred a number of other terms indicating eternal movement, thus emphasising the evidence for his discovery of a new element.[20] These five elements have been associated since Plato's Timaeus with the five platonic solids. Earth was associated with the cube, air with the octahedron, water with the icosahedron, and fire with the tetrahedron. Of the fifth Platonic solid, the dodecahedron, Plato obscurely remarked, "...the god used [it] for arranging the constellations on the whole heaven". Aristotle added a fifth element, aither (aether in Latin, "ether" in English) and postulated that the heavens were made of this element, but he had no interest in matching it with Plato's fifth solid.[21]

Neo-Platonism

[edit]The Neoplatonic philosopher Proclus rejected Aristotle's theory relating the elements to the sensible qualities hot, cold, wet, and dry. He maintained that each of the elements has three properties. Fire is sharp (ὀξυτητα), subtle (λεπτομερειαν), and mobile (εὐκινησιαν) while its opposite, earth, is blunt (αμβλυτητα), dense (παχυμερειαν), and immobile (ακινησιαν[22]); they are joined by the intermediate elements, air and water, in the following fashion:[23]

| Fire | Sharp | Subtle | Mobile |

|---|---|---|---|

| Air | Blunt | Subtle | Mobile |

| Water | Blunt | Dense | Mobile |

| Earth | Blunt | Dense | Immobile |

Hermeticism

[edit]A text written in Egypt in Hellenistic or Roman times called the Kore Kosmou ("Virgin of the World") ascribed to Hermes Trismegistus (associated with the Egyptian god Thoth), names the four elements fire, water, air, and earth. As described in this book:

And Isis answer made: Of living things, my son, some are made friends with fire, and some with water, some with air, and some with earth, and some with two or three of these, and some with all. And, on the contrary, again some are made enemies of fire, and some of water, some of earth, and some of air, and some of two of them, and some of three, and some of all. For instance, son, the locust and all flies flee fire; the eagle and the hawk and all high-flying birds flee water; fish, air and earth; the snake avoids the open air. Whereas snakes and all creeping things love earth; all swimming things love water; winged things, air, of which they are the citizens; while those that fly still higher love the fire and have the habitat near it. Not that some of the animals as well do not love fire; for instance salamanders, for they even have their homes in it. It is because one or another of the elements doth form their bodies' outer envelope. Each soul, accordingly, while it is in its body is weighted and constricted by these four.[24]

Ancient Indian philosophy

[edit]Hinduism

[edit]

The system of five elements are found in Vedas, especially Ayurveda, the pancha mahabhuta, or "five great elements", of Hinduism are:

- bhūmi or pṛthvī (earth),[25]

- āpas or jala (water),

- agní or tejas (fire),

- vāyu, vyāna, or vāta (air or wind)

- ākāśa, vyom, or śūnya (space or zero) or (aether or void).[26]

They further suggest that all of creation, including the human body, is made of these five essential elements and that upon death, the human body dissolves into these five elements of nature, thereby balancing the cycle of nature.[27]

The five elements are associated with the five senses, and act as the gross medium for the experience of sensations. The basest element, earth, created using all the other elements, can be perceived by all five senses — (i) hearing, (ii) touch, (iii) sight, (iv) taste, and (v) smell. The next higher element, water, has no odour but can be heard, felt, seen and tasted. Next comes fire, which can be heard, felt and seen. Air can be heard and felt. "Akasha" (aether) is beyond the senses of smell, taste, sight, and touch; it being accessible to the sense of hearing alone.[28][29][30]

Buddhism

[edit]

Buddhism has had a variety of thought about the five elements and their existence and relevance, some of which continue to this day.

In the Pali literature, the mahabhuta ("great elements") or catudhatu ("four elements") are earth, water, fire and air. In early Buddhism, the four elements are a basis for understanding suffering and for liberating oneself from suffering. The earliest Buddhist texts explain that the four primary material elements are solidity, fluidity, temperature, and mobility, characterised as earth, water, fire, and air, respectively.[31]

The Buddha's teaching regarding the four elements is to be understood as the base of all observation of real sensations rather than as a philosophy. The four properties are cohesion (water), solidity or inertia (earth), expansion or vibration (air) and heat or energy content (fire). He promulgated a categorisation of mind and matter as composed of eight types of "kalapas" of which the four elements are primary and a secondary group of four are colour, smell, taste, and nutriment which are derivative from the four primaries.[32][a][33]

Thanissaro Bhikkhu (1997) renders an extract of Shakyamuni Buddha's from Pali into English thus:

Just as a skilled butcher or his apprentice, having killed a cow, would sit at a crossroads cutting it up into pieces, the monk contemplates this very body — however it stands, however it is disposed — in terms of properties: 'In this body there is the earth property, the liquid property, the fire property, & the wind property.'[34]

Tibetan Buddhist medical literature speaks of the pañca mahābhūta (five elements) or "elemental properties":[35] earth, water, fire, wind, and space.[35] The concept was extensively used in traditional Tibetan medicine.[36][37][35] Tibetan Buddhist theology, tantra traditions, and "astrological texts" also spoke of them making up the "environment, [human] bodies," and at the smallest or "subtlest" level of existence, parts of thought and the mind.[35] Also at the subtlest level of existence, the elements exist as "pure natures represented by the five female buddhas", Ākāśadhātviśvarī, Buddhalocanā, Mamakī, Pāṇḍarāvasinī, and Samayatārā, and these pure natures "manifest as the physical properties of earth (solidity), water (fluidity), fire (heat and light), wind (movement and energy), and" the expanse of space.[35] These natures exist as all "qualities" that are in the physical world and take forms in it.[35]

Ancient African philosophy

[edit]Central Africa

[edit]

In traditional Bakongo religion, the five elements are incorporated into the Kongo cosmogram. This sacred symbol also depicts the physical world (Nseke), the spiritual world of the ancestors (Mpémba), the Kalûnga line that runs between the two worlds, the circular void that originally formed the two worlds (mbûngi), and the path of the sun. Each element correlates to a period in the life cycle, which the Bakongo people also equate to the four cardinal directions. According to their cosmology, all living things go through this cycle.[38]

- Aether represents mbûngi, the circular void that begot the universe.

- Air (South) represents musoni, the period of conception that takes place during spring.

- Fire (East) represent kala, the period of birth that takes place during summer.

- Earth (North) represents tukula, the period of maturity that takes place during fall.

- Water (West) represents luvemba, the period of death that takes place during winter

West Africa

[edit]In traditional Bambara spirituality, the Supreme God created four additional essences of himself during creation. Together, these five essences of the deity correlate with the five classical elements.[39][40]

- Koni is the thought and void (aether).

- Bemba (also called Pemba) is the god of the sky and air.

- Nyale (also called Koroni Koundyé) is the goddess of fire.

- Faro is the androgynous god of water.

- Ndomadyiri is the god and master of the earth.

Post-classical history

[edit]Alchemy

[edit]

The elemental system used in medieval alchemy was developed primarily by the anonymous authors of the Arabic works attributed to Pseudo Apollonius of Tyana.[41] This system consisted of the four classical elements of air, earth, fire, and water, in addition to a new theory called the sulphur-mercury theory of metals, which was based on two elements: sulphur, characterising the principle of combustibility, "the stone which burns"; and mercury, characterising the principle of metallic properties. They were seen by early alchemists as idealised expressions of irreducible components of the universe[42] and are of larger consideration within philosophical alchemy.

The three metallic principles—sulphur to flammability or combustion, mercury to volatility and stability, and salt to solidity—became the tria prima of the Swiss alchemist Paracelsus. He reasoned that Aristotle's four element theory appeared in bodies as three principles. Paracelsus saw these principles as fundamental and justified them by recourse to the description of how wood burns in fire. Mercury included the cohesive principle, so that when it left in smoke the wood fell apart. Smoke described the volatility (the mercurial principle), the heat-giving flames described flammability (sulphur), and the remnant ash described solidity (salt).[43]

Chinese

[edit]Chinese traditional concepts adopt a set of elements called the 五行 (wuxing, literally "five phases"). These five are Metal or Gold (金 Jīn), Wood (木 Mù), Water (水 Shuǐ), Fire (火 Huǒ), and Earth or Soil (土 Tǔ).[44] These can be linked to Taiji, Yinyang, Four Symbols, Bagua, Hexagram and I Ching.

- Gold (West) represents the lesser yin symbol, autumn, the white colour, and White Tiger mascot, Taotie creature (Earth).

- Wood (East) represents the lesser yang symbol, spring, the green colour, and Azure Dragon mascot, Feilian creature (Wind).

- Water (North) represents the great yin symbol, winter, the black colour, and Black Turtle-Snake mascot.

- Fire (South) represents the great yang symbol, summer, the red colour, and Vermilion Bird mascot.

- Soil (Center) represents the Qi symbol, intermediate season, the yellow colour, and Yellow Dragon mascot, Hundun creature (Void).

Japanese

[edit]

Japanese traditions use a set of elements called the 五大 (godai, literally "five great"). These five are earth, water, fire, wind/air, and void. These came from Indian Vastu shastra philosophy and Buddhist beliefs; in addition, the classical Chinese elements (五行, wu xing) are also prominent in Japanese culture, especially to the influential Neo-Confucianists during the medieval Edo period.[45]

- Earth (地 Chi) represented rocks and stability.

- Water (水 Sui) represented fluidity and adaptability.

- Fire (火 Ka) represented life and energy.

- Wind (風 Fuu) represented movement and expansion.

- Void (空 Kuu) or Sky/Heaven represented spirit and creative energy.

Medieval Aristotelian philosophy

[edit]The Islamic philosophers al-Kindi, Avicenna and Fakhr al-Din al-Razi followed Aristotle in connecting the four elements with the four natures heat and cold (the active force), and dryness and moisture (the recipients).[46]

Medicine Wheel

[edit]The medicine wheel symbol is a modern invention attributed to Native American peoples dating to approximately 1972, with the following descriptions and associations being a later addition. The associations with the classical elements are not grounded in traditional Indigenous teachings and the symbol has not been adopted by all Indigenous American nations.[47][48][49][50][51]

- Earth (South) represents the youth cycle, summer, the Indigenous race, and cedar medicine.

- Fire (East) represents the birth cycle, spring, the Asian race, and tobacco medicine.

- Wind/Air (North) represents the elder cycle, winter, the European race, and sweetgrass medicine.

- Water (West) represents the adulthood cycle, autumn, the African race, and sage medicine.

Modern history

[edit]

Chemical element

[edit]The Aristotelian tradition and medieval alchemy eventually gave rise to modern chemistry, scientific theories and new taxonomies. By the time of Antoine Lavoisier, for example, a list of elements would no longer refer to classical elements.[52] Some modern scientists see a parallel between the classical elements and the four states of matter: solid, liquid, gas and weakly ionized plasma.[53]

Modern science recognises classes of elementary particles which have no substructure (or rather, particles that are not made of other particles) and composite particles having substructure (particles made of other particles).

Western astrology

[edit]

Western astrology uses the four classical elements in connection with astrological charts and horoscopes. The twelve signs of the zodiac are divided into the four elements: Fire signs are Aries, Leo and Sagittarius, Earth signs are Taurus, Virgo and Capricorn, Air signs are Gemini, Libra and Aquarius, and Water signs are Cancer, Scorpio, and Pisces.[54]

Criticism

[edit]The Dutch historian of science Eduard Jan Dijksterhuis writes that the theory of the classical elements "was bound to exercise a really harmful influence. As is now clear, Aristotle, by adopting this theory as the basis of his interpretation of nature and by never losing faith in it, took a course which promised few opportunities and many dangers for science."[55] Bertrand Russell says that Aristotle's thinking became imbued with almost biblical authority in later centuries. So much so that "Ever since the beginning of the seventeenth century, almost every serious intellectual advance has had to begin with an attack on some Aristotelian doctrine".[56]

See also

[edit]- Arche – Basic proposition or assumption

- Bagua – Eight trigrams used in Taoist cosmology

- Elemental – Mythic entity personifying one of the classical elements

- Jabir ibn Hayyan § The sulfur–mercury theory of metals – Early Islamic alchemy

- Periodic table – Tabular arrangement of the chemical elements

- Phlogiston theory – Superseded theory of combustion

- Prima materia – First or prime matter

- Qi – Vital force in traditional Chinese philosophy

- States of matter – Forms which matter can take

Notes

[edit]- ^ Thera (1956), pp. 318–320: "the atomic theory prevailed in India in the time of the Buddha. Paramàõu was the ancient term for the modern atom. According to the ancient belief one rathareõu consists of 16 tajjàris, one tajjàri, 16 aõus; one aõu, 16 paramàõus. The minute particles of dust seen dancing in the sunbeam are called rathareõus. One para-màõu is, therefore, 4096th part of a rathareõu. This para-màõu was considered indivisible. With His supernormal knowledge the Buddha analysed this so-called paramàõu and declared that it consists of paramatthas—ultimate entities which cannot further be subdivided." "ñhavi in earth, àpo in water, tejo in fire, and vàyo in air. They are also called Mahàbhåtas or Great Essentials because they are invariably found in all material substances ranging from the infinitesimally small cell to the most massive object. Dependent on them are the four subsidiary material qualities of colour (vaõõa)., smell (gandha), taste (rasa), and nutritive essence (ojà). These eight coexisting forces and qualities constitute one material group called 'Suddhaññhaka Rupa kalàpa—pure-octad material group'."

References

[edit]- ^ Boyd, T.J.M.; Sanderson, J.J. (2003). The Physics of Plasmas. Cambridge University Press. p. 1. ISBN 9780521459129. LCCN 2002024654.

- ^ Ball, P. (2004). The Elements: A Very Short Introduction. Very Short Introductions. OUP Oxford. p. 33. ISBN 9780191578250.

- ^ Al-Khalili, Jim (2009). Science and Islam. BBC.

- ^ agranoff, bernard (1 August 2008). "Brain Food". Gastronomica. 8 (3): 79–85. doi:10.1525/gfc.2008.8.3.79. ISSN 1529-3262.

- ^ a b Curd (2020).

- ^ Ross (2020).

- ^ Russell (1991), p. 46.

- ^ Russell (1991), p. 61.

- ^ Russell (1991), pp. 62, 75.

- ^ Russell (1991), p. 72.

- ^ Boyle, Robert (1661). The Sceptical Chymist: or Chymico-Physical Doubts & Paradoxes, Touching the Spagyrist's Principles Commonly call'd Hypostatical; As they are wont to be Propos'd and Defended by the Generality of Alchymists. Whereunto is præmis'd Part of another Discourse relating to the same Subject. Printed by J. Cadwell for J. Crooke. pp. 21–22.

- ^ Lindemann, Mary (2010). Medicine and Society in early Modern Europe. Cambridge University Press. p. 19. ISBN 978-0-521-73256-7.

- ^ Plato, Timaeus, 48b

- ^ Weisberg, M.; Needham, P.; Hendry, R. (2019), "Philosophy of Chemistry", in Zalta, E. N. (ed.), The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Spring 2019 ed.), Metaphysics Research Lab, Stanford University

- ^ Aristotle (1922) [350 BCE]. On the Heavens. Translated by Stocks, J. L. pp. 3.3, 302a17–19.

- ^ Aristotle, On the Heavens, translated by Stocks, J.L., III.3.302a17–19

- ^ Aristotle. (in Greek) – via Wikisource.

τὸ μὲν γὰρ πῦρ θερμὸν καὶ ξηρόν, ὁ δ' ἀὴρ θερμὸν καὶ ὑγρόν (οἷον ἀτμὶς γὰρ ὁ ἀήρ), τὸ δ' ὕδωρ ψυχρὸν καὶ ὑγρόν, ἡ δὲ γῆ ψυχρὸν καὶ ξηρόν

- ^ Lloyd (1968), pp. 166–169.

- ^ Lloyd (1968), pp. 133–139.

- ^ Chung-Hwan, Chen (1971). "Aristotle's analysis of change and Plato's theory of Transcendent Ideas". In Anton, John P.; Preus, Anthony (eds.). Ancient Greek Philosophy. Vol. 2. SUNY Press. pp. 406–407. ISBN 0873956230..

- ^ Wildberg (1988): Wildberg discusses the correspondence of the Platonic solids with elements in Timaeus but notes that this correspondence appears to have been forgotten in Epinomis, which he calls "a long step towards Aristotle's theory", and he points out that Aristotle's ether is above the other four elements rather than on an equal footing with them, making the correspondence less apposite.

- ^ Siorvanes, Lucas (1986). Proclus on the Elements and the Celestial Bodies: Physical Thought in Late Neoplatonism (PDF) (Thesis). p. 168.

- ^ Proclus, Commentary on Plato's Timaeus, 3.38.1–3.39.28

- ^ Mead, G. R. S. (1906). Thrice-Greatest Hermes. Vol. 3. London & Benares: The Theosophical Publishing Society. pp. 133–134. OCLC 76743923.

- ^ Gopal, Madan (1990). K.S. Gautam (ed.). India through the ages. Publication Division, Ministry of Information and Broadcasting, Government of India. p. 78.

- ^ Ranade, Subhash (December 2001). Natural Healing Through Ayurveda. Motilal Banarsidass Publisher. p. 32. ISBN 9788120812437.

- ^ Jagannathan, Maithily. South Indian Hindu Festivals and Traditions. Abhinav Publications. pp. 60–62.

- ^ Meyer-Dinkgräfe, Daniel (2005). Theatre and Consciousness: Explanatory Scope and Future Potential. Intellect Books. ISBN 9781841501307.

- ^ Nath, Samir (1998). Encyclopaedic Dictionary of Buddhism. Sarup & Sons. p. 653. ISBN 9788176250191.

- ^ Tirupati Raju, Poola. Structural Depths of Indian Thought: Toward a Constructive Postmodern Ethics. SUNY Press. p. 81.

- ^ Bodhi, ed. (1995). "28, Mahāhatthipadopamasutta". The Middle Length Discourses of the Buddha: a New Translation of the Majjhima Nikaya. Boston: Wisdom Publications in association with the Barre Center for Buddhist Studies. ISBN 0-86171-072-X. OCLC 31331607.

- ^ Thera, Narada (1956). A Manual of Abhidhamma. Buddhist Missionary Society. pp. 318–320.

- ^ Anuruddha (1993). Bodhi (ed.). A Comprehensive Manual of Abhidhamma: the Abhidhammattha Sangaha of Ācariya Anuruddha. Kandy, Sri Lanka: Buddhist Publication Society. p. 260. ISBN 955-24-0103-8. OCLC 33088951.

Thus as fourfold the Tathagatas reveal the ultimate realities-consciousness, mental factors, matter, and Nibbana.

- ^ "Kayagata-sati Sutta". Majjhima Nikaya. p. 119. Retrieved 30 January 2009 – via accesstoinsight.org.

- ^ a b c d e f The Tibetan Book of the Dead. Translated by Dorje, Gyurnme; Coleman, Graham; Jinpa, Thupten. Introductory commentary by the 14th Dalai Lama (First American ed.). New York: Viking Press. 2005. p. 502. ISBN 0-670-85886-2.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - ^ Gurmet, Padma (2004). "'Sowa – Rigpa': Himalayan art of healing". Indian Journal of Traditional Knowledge. 3 (2): 212–218.

- ^ Bigalke, Boris (11 January 2013). "Behavioral and Nutritional Therapy in Patients With Coronary Artery Disease According to Traditional Tibetan Medicine Protocol". University Hospital Tuebingen.

- ^ Fu-Kiau, Kimbwandènde Kia Bunseki (2001). African cosmology of the Bântu-Kôngo : tying the spiritual knot : principles of life & living. Brooklyn, N.Y.: Athelia Henrietta Press, Pub. ISBN 978-1-890157-28-9.

- ^ Lugira, Aloysius Muzzanganda (2009). African Traditional Religion. Infobase Publishing. p. 39. ISBN 978-1-4381-2047-8.

- ^ "Bambara Religion | Encyclopedia.com". www.encyclopedia.com. Retrieved 21 April 2024.

- ^ Norris (2006), pp. 43–65.

- ^ Clulee, Nicholas H. (1988). John Dee's Natural Philosophy. Routledge. p. 97. ISBN 978-0-415-00625-5.

- ^ Strathern (2001), p. 79.

- ^ Theobald, Ulrich (2011) "Yin-Yang and Five Agents Theory, Correlative Thinking" in ChinaKnowledge.de - An Encyclopaedia on Chinese History, Literature and Art

- ^ "Encountering the '5 elements' in Japan's national parks". Travel. 22 February 2022. Archived from the original on 23 February 2022. Retrieved 7 May 2023.

- ^ Rafati, Vahid. "Lawh-i-Hikmat: The Two Agents and the Two Patients". 'Andalib. 5 (19): 29–38.

- ^ Shaw, Christopher (August 1995). "A Theft of Spirit?". New Age Journal. Retrieved 28 April 2021.

- ^ Thomason, Timothy C (27 October 2013). "The Medicine Wheel as a Symbol of Native American Psychology". The Jung Page. The Jung Center of Houston. Retrieved 28 April 2021.

- ^ Chavers, Dean (15 October 2014). "5 Fake Indians: Checking a Box Doesn't Make You Native". Indian Country Today. Retrieved 28 April 2021.

- ^ Beyer, Steve (3 February 2008). "Selling Spirituality". Singing to the Plants. Retrieved 28 April 2021.

- ^ Bear Nicholas, Andrea (April 2008). "The Assault on Aboriginal Oral Traditions: Past and Present". In Hulan, Renée; Eigenbrod, Renate (eds.). Aboriginal Oral Traditions: Theory, Practice, Ethics. Halifax, NS: Fernwood Pub Co Ltd. pp. 7–43. ISBN 9781552662670.

- ^ Lavoisier, Antoine. "Elements of Chemistry". In Giunta, Carmen (ed.). Classic Chemistry.

- ^ Kikuchi, Mitsuru (2011), Frontiers in Fusion Research: Physics and Fusion, London: Springer Science and Business Media, p. 12, ISBN 978-1-84996-411-1,

Empedocles (495–435 BC) proposed that the world was made of earth, water, air, and fire, which may correspond to solid, liquid, gas, and weakly ionized plasma. Surprisingly, this idea may catch the essence.

- ^ Tester (1999), pp. 59–61, 94.

- ^ Dijksterhuis (1969), p. 71.

- ^ Russell (1991), p. 173.

Bibliography

[edit]- Curd, Patricia. "Presocratic Philosophy". In Zalta, Edward N. (ed.). Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Fall 2020 ed.).

- Dijksterhuis, Eduard Jan (1969). The Mechanization of the World Picture. Translated by Dikshoorn, C. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

- Lloyd, G. E. R. (1968). Aristotle: The Growth and Structure of his Thought. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-09456-6.

- Norris, John A. (2006). "The Mineral Exhalation Theory of Metallogenesis in Pre-Modern Mineral Science". Ambix. 53 (1): 43–65. doi:10.1179/174582306X93183. S2CID 97109455.

- Ross, Kelley L. (2020). "The Greek Elements". Retrieved 2 March 2023.

- Russell, Bertrand (1991). History of Western Philosophy (2nd ed.). London: Routledge. ISBN 0-415-07854-7. OCLC 221108071.

- Strathern, Paul (21 April 2001). Mendeleyev's Dream: The Quest for the Elements. Macmillan. ISBN 978-0-312-26204-4.

- Tester, S. J. (1999). A History of Western Astrology. Boydell & Brewer.

External links

[edit] Media related to Classical elements at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Classical elements at Wikimedia Commons- Section on 4 elements in Buddhism