Recent from talks

Contribute something

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Environmental justice

View on Wikipedia

| Part of a series on |

| Environmental justice |

|---|

|

|

Environmental justice is a social movement that addresses injustice that occurs when poor or marginalized communities are harmed by hazardous waste, resource extraction, and other land uses from which they do not benefit.[1][2] The movement has generated hundreds of studies showing that exposure to environmental harm is inequitably distributed.[3] Additionally, many marginalized communities, including Black/racialized communities and the LGBTQ community, are disproportionately impacted by natural disasters.

The movement began in the United States in the 1980s. It was heavily influenced by the American civil rights movement and focused on environmental racism within rich countries. The movement was later expanded to consider gender, LGBTQ people, international environmental injustice, and inequalities within marginalized groups. As the movement achieved some success in rich countries, environmental burdens were shifted to the Global South (as for example through extractivism or the global waste trade). The movement for environmental justice has thus become more global, with some of its aims now being articulated by the United Nations. The movement overlaps with movements for Indigenous land rights and for the human right to a healthy environment.[4]

The goal of the environmental justice movement is to achieve agency for marginalized communities in making environmental decisions that affect their lives. The global environmental justice movement arises from local environmental conflicts in which environmental defenders frequently confront multi-national corporations in resource extraction or other industries. Local outcomes of these conflicts are increasingly influenced by trans-national environmental justice networks.[5][6]

Environmental justice scholars have produced a large interdisciplinary body of social science literature that includes contributions to political ecology, environmental law, and theories on justice and sustainability.[2][7][8][9]

Scope

[edit]Environmental justice has evolved into a comprehensive global movement, introducing numerous concepts to political ecology, including ecological debt, environmental racism, climate justice, food sovereignty, corporate accountability, ecocide, sacrifice zones, and environmentalism of the poor. It aims, in part, to augment human rights law, which traditionally overlooked the relationship between the environment and human rights. Despite attempts to integrate environmental protection into human rights law, challenges persist, particularly concerning climate justice.

Scholars such as Kyle Powys Whyte and Dina Gilio-Whitaker have extended the discourse on environmental justice concerning Indigenous peoples and settler-colonialism. Gilio-Whitaker critiques distributive justice, which assumes a capitalistic commodification of land inconsistent with many Indigenous worldviews. Whyte explores environmental justice within the context of colonialism's catastrophic environmental impacts on Indigenous peoples' traditional livelihoods and identities.

Definitions

[edit]

The United States Environmental Protection Agency defines environmental justice as:[10]

the fair treatment and meaningful involvement of all people regardless of race, color, national origin, or income with respect to the development, implementation, and enforcement of environmental laws, regulations and policies. Fair treatment means that no group of people, including racial, ethnic, or socio-economic groups, should bear a disproportionate share of the negative environmental consequences resulting from industrial, municipal, and commercial operations or the execution of federal, state, local, and tribal programs and policies

Environmental justice is also discussed as environmental racism or environmental inequality.[11]

Environmental justice is typically defined as distributive justice, which is the equitable distribution of environmental risks and benefits.[12] Some definitions address procedural justice, which is the fair and meaningful participation in decision-making. Other scholars emphasise recognition justice, which is the recognition of oppression and difference in environmental justice communities. People's capacity to convert social goods into a flourishing community is a further criteria for a just society.[2][12][13] However, initiatives have been taken to expand the notion of environmental justice beyond the three pillars of distribution, participation, and recognition to also include the dimensions of self-governing authority, relational ontologies, and epistemic justice.[14]

Robert D. Bullard writes that environmental justice, as a social movement and ideological stewardship, may instead be seen as a conversation of equity. Bullard writes that equity is distilled into three board categories: procedural, geographic, and social.[1] From his publication "Confronting Environmental Racism in the Twenty-First Century," he draws out the difference between the three within the context of environmental injustices:

Procedural equity refers to the "fairness" question: the extent that rules, regulations, evaluation criteria and enforcement are applied uniformly across the board and in a non-discriminatory way. Unequal protection might result from nonscientific and undemocratic decisions, exclusionary practices, public hearings held in remote locations and at inconvenient times, and use of English-only material as the language in which to communicate and conduct hearings for non-English-speaking publics.

Geographic equity refers to the location and spatial configuration of communities and their proximity to environmental hazards, noxious facilities and locally unwanted land uses (Lulus) such as landfills, incinerators, sewage treatment plants, lead smelters, refineries and other noxious facilities. For example, unequal protection may result from land-use decisions that determine the location of residential amenities and disamenities. The poor and communities of colour often suffer a "triple" vulnerability of noxious facility siting, as do the unincorporated—sparsely populated communities that are not legally chartered as cities or municipalities and are therefore usually governed by distant county governments rather than having their own locally elected officials.

Social equity assesses the role of sociological factors (race, ethnicity, class, culture, life styles, political power, etc.) on environmental decision making. Poor people and people of colour often work in the most dangerous jobs and live in the most polluted neighbourhoods, their children exposed to all kinds of environmental toxins in the playgrounds and in their homes.

Indigenous environmental justice

[edit]In non-Native communities, where toxic industries and other discriminatory practices are disproportionately occurring, residents rely on laws and statutory frameworks outlined by the EPA. They rely on distributive justice, centered around the nature of private property. Native Americans do not fall under the same statutory frameworks as they are citizens of Indigenous nations, not ethnic minorities. As individuals, they are subject to American laws. As nations, they are subject to a separate legal regime, constructed on the basis of pre-existing sovereignty acknowledged by treaty and the U.S. Constitution. Environmental justice to Indigenous persons is not understood by legal entities but rather their distinct cultural and religious doctrines.[15]

Environmental Justice for Indigenous peoples follows a model that frames issues in terms of their colonial condition and can affirm decolonization as a potential framework within environmental justice.[16] While Indigenous peoples' lived experiences vary from place to place, David Pellow writes that there are "common realities they all share in their experience of colonization that make it possible to generalize an Indigenous methodology while recognizing specific, localized conditions".[16] Even abstract ideas like the right to a clean environment, a human right according to the United Nations,[17] contradicts Indigenous peoples understanding of environmental justice as it reflects the commodification of land when seen in light of property values.[15]

Environmentalism of the poor

[edit]Joan Martinez-Alier's influential concept of the environmentalism of the poor highlights the ways in which marginalized communities, particularly those in the Global South, are disproportionately affected by environmental degradation and the importance of including their perspectives and needs in environmental decision-making. Many wealthy countries forcibly extract resources from countries in the Global South, causing severe environmental and economic damage. For instance, companies such as Shell Oil have conducted drilling in Nigeria, specifically in Ogoniland, for decades. This drilling has required a $1 billion cleanup of the Niger River Delta due to severe pollution.[18] In response to such damage, Ogoni residents, including the Ogoni Nine and Ken Saro-Wiwa, began leading large-scale protests. The Nigerian government, which was backed by Shell Oil, violently suppressed protestors through arrests and executions.[19] Martinez-Alier's work also introduces the concept of "ecological distribution conflicts," which are conflicts over access to and control of natural resources and the environmental impacts that result from their use, and which are often rooted in social and economic inequalities.[4]

Another example of environmentalism of the poor is how low-income communities are disproportionately impacted by environmental hazards. For instance, low-income communities tend to be located closer to sources of pollution, with one study by the University of Michigan finding that more than half of those living within three kilometers of hazardous waste facilities were impoverished.[20]

Slow violence

[edit]The term "slow violence" was coined by author Rob Nixon in his 2011 book Slow Violence and the Environmentalism of the Poor.[21] Slow violence is defined as "violence that occurs gradually and out of sight, a violence of delayed destruction that is dispersed across time and space, an attritional violence that is typically not viewed as violence at all".[21] Examples include the effects of climate change, toxic drift, deforestation, oil spills, and the environmental aftermath of war.

Slow violence exacerbates the vulnerability of ecosystems and of people who are poor, disempowered, and often involuntarily displaced, while fueling social conflicts that arise from desperation. Environmental justice as a social movement addresses environmental issues that may be defined as slow violence and otherwise may not be addressed by legislative bodies.

Critical environmental justice

[edit]Drawing on concepts of anarchism, posthumanism, critical theory,[22] and intersectional feminism, author David Naguib Pellow created the concept of Critical Environmental Justice (CEJ).[23] Critical EJ is a perspective intended to address a number of limitations and tensions within EJ Studies. Critical EJ calls for scholarship that builds on environmental justice studies by questioning assumptions and gaps in earlier work, embracing greater interdisciplinary, and moving towards methodologies and epistemologies including and beyond the social sciences.[24] Critical EJ scholars believe that multiple forms of inequality drive and characterize the experience of environmental injustice.[25]

Differentiation between conventional environmental studies and Critical EJ studies is done through four distinctive "pillars". These include: (1) intersectionality; (2) spatial and temporal scale; (3) working toward solutions and justice outside of the state; and (4) as beings as indispenable.[25]

In What is Critical Environmental Justice, Pellow explains:[24]

Where we find rivers dammed for hydropower plants we also tend to find indigenous peoples and fisherfolk, as well as other working people, whose livelihoods and health are harmed as a result; when sea life suffers from exposure to toxins such as mercury, we find that human beings also endure the effects of mercury when they consume those animals; and the intersecting character of multiple forms of inequality is revealed when nuclear radiation or climate change affects all species and humans across all social class levels, racial/ethnic groups, genders, abilities, and ages.

First Pillar: Intersectionality

[edit]The first pillar of Critical EJ Studies involves the recognition that social inequality and oppression in all forms intersect, and that actors in the more-than-human world are subjects of oppression and frequently agents of social change.[24] Developed by Kimberlé Crenshaw in 1989, intersectionality theory states that individuals exist in a crossroads of all their identities, with privilege and marginalization in the intersection between their class, race, gender, sexuality, queerness, cis- or transness, ethnicity, ability, and other facts of identity.[26][27] As David Nibert and Michael Fox put it in the context of injustice, "The oppression of various devalued groups in human societies is not independent and unrelated; rather, the arrangements that lead to various forms of oppression are integrated in such a way that the exploitation of one group frequently augments and compounds the mistreatment of others." Thus, Critical EJ views racism, heteropatriarchy, classism, nativism, ableism, ageism, speciesism (the belief that one species is superior to another), and other forms of inequality as intersecting axes of domination and control.[24]

Second Pillar: Spatial and Temporal Scale

[edit]The second pillar of Critical EJ is a focus on the role of scale in the production and possible resolution of environmental injustices.[24] Critical EJ embraces multi-scalar methodological and theoretical approaches order to better comprehend the complex spatial and temporal causes, consequences, and possible resolutions of EJ struggles.[25] Scale is deeply racialized, gendered, and classed. While the conclusions of climate scientists are remarkably clear that anthropogenic climate change is occurring at a dramatic pace and with increasing intensity, Pellow writes in his 2016 publication Toward A Critical Environmental Justice Studies that "this is also happening unevenly, with people of color, the poor, indigenous peoples, peoples of the global South, and women suffering the most."[25]

Pellow further contextualizes scale through temporal dimensions. For instance, Pellow observes in his 2017 publication What is Critical Environmental Justice that while "a molecule of carbon dioxide or nitrous oxide can occur in an instant, … it remains in the atmosphere for more than a century, so the decisions we make at one point in time can have dramatic ramifications for generations to come".[24] Pollution does not stay where it starts, and so consideration must be taken as to the scale of an issue rather than solely its effects.

Third Pillar: Working Toward Solutions Outside the State

[edit]The third pillar of Critical EJ is the view that social inequalities - from racism to speciesism - are deeply embedded in society and reinforced by state power, and therefore the current social order stands as a fundamental obstacle to social and environmental justice.[24] Pellow argues in his 2017 publication What is Critical Environmental Justice that social change movements may be better off thinking and acting beyond the state and capital as targets of reform and/or as reliable partners.[25] Furthermore, that scholars and activists are not asking how they might build environmentally resilient communities that exist beyond the state, but rather how they might do so with a different model of state intervention.SOURCE Pellow believes that by building and supporting strongly democratic practices, relationships, and institutions, movements for social change will become less dependent upon the state, while any elements of the state they do work through may become more robustly democratic.[24]

He contextualizes this pillar with activist the anarchist-inspired Common Ground Collective, which was co-created by Scott Crow to provide services for survivors of Hurricane Katrina on the Gulf Coast in 2005.[24] Crow gave insight as to what change outside of state power looks like, telling Pellow:[24]

We did service work, but it was a revolutionary analysis and practice. We created a horizontal organization that defied the state and did our work in spite of the state … not only did we feed people and give them aid and hygiene kits and things like that, but we also stopped housing from being bulldozed, we cut the locks on schools when they said schools couldn't be opened, and we cleaned the schools out because the students and the teachers wanted that to happen. And we didn't do a one size fits all like the Red Cross would do – we asked the communities, every community we went into, we asked multiple people, the street sex workers, the gangsters, the church leaders, everybody, we talked to them: what can we do to help your neighborhood, to help your community, to help you? And that made us different because for me, it's the overlay of anarchism. Instead of having one franchise thing, you just have concepts, and you just pick the components that match the needs of the people there.

Fourth Pillar: Indispensability

[edit]The fourth pillar of Critical EJ centers on a concept Pellow calls "Indispensability". Critical EJ builds on this work by countering the ideology of white supremacy and human dominionism, and articulating the perspective that excluded, marginalized, and other populations, beings, and things - both human and nonhuman - must be viewed not as expensable but rather an indispensable to our collective futures.[25] Pellow uses racial indispensability when referring to people of color and socioecological indispensability when referring to broader communities within and across the human/nonhuman divide and their relationships to one another.[25] Pellow expands writing in Toward A Critical Environmental Justice Studies that "racial indispensability is intended to challenge the logic of racial expendability and is the idea that institutions, policies, and practices that support and perpetrate anti-Black racism suffer from the flawed assumption that the future of African Americans is somehow de-linked from the future of White communities."[25]

History

[edit]

Traces of environmental injustices span millennia of unrecorded history. For instance, Indigenous peoples have experienced environmental devastation of a genocidal kind for several centuries. Origins of the environmental justice movement can be traced to the Indigenous Environmental Movement, which has involved Indigenous populations fighting against displacement and assimilation for sovereignty and land rights for hundreds of years. For instance, Chaco Culture National Historical Park, a landscape that is sacred to the Diné people and part of the Navajo Nation, was once a center of uranium mining and a hotspot for oil and gas production. Although now closed, the mines continue to impact the health of the surrounding Indigenous community, leaving members continuously advocating for community protection. Ironically, the various Indigenous territories, which make up 22% of the world's land surface, hold about 80% of the world's remaining biodiversity.

The terms 'environmental justice' and 'environmental' racism' did not enter the common vernacular until the first environmental justice cases were brought to court in 1979 in Texas, and in 1982 in North Carolina. The 1979 case, Bean v. Southwestern Waste Management Corporation was in response to a decision placing a garbage dump in Northwood Manor in East Houston.[28] Citing that this decision was racially motivated, R. Bullard was asked to compile data from 1970 to 1979 addressing "all landfills, incinerators and solid waste sites" located in Houston, TX at that time.[29] While the case was lost, it set the legal precedent for environmental justice as a legislative term, with Bullard's findings being later confirmed in a 1983 federal report.[30]

Origins of the Warren County, North Carolina Environmental Justice Movement

Much of the thinking, language, and strategy for the environmental justice movement emerged from the rural, sparsely populated community of Afton, Warren County, North Carolina in late 1978 in response to an explosive December 21st surprise announcement by Governor James B. Hunt Jr.'s Administration that "public sentiment would not deter the state's plan to purchase private land in Warren County." [31] to bury PCB-tainted soil that had been spewed the previous summer along some 270 miles of roadsides in fourteen counties and at the Ft. Bragg Army Base.[32][33]

With the announcement came notice of an EPA Public Hearing scheduled in Warren County for January 4, 1979, where the state would present its PCB landfill plan for EPA approval. Warren County residents responded with a fury, first forming a steering committee, and then uniting on December 26, 1978, as a multi-racial coalition of some 150 citizens who formed themselves into an official body, Warren County Citizens Concerned About PCBs (WCCC).[34]

In 1982, the residents of Warren County, North Carolina protested against a landfill designed to accept polychlorinated biphenyls in the 1982 PCB protests. Thirty-thousand gallons of PCB fluid lined 270 miles of roadway in fourteen North Carolina Counties, and the state announced that a landfill would be built rather than undergoing permanent detoxification.[35] Warren County was chosen, the poorest county in the state with a per capita income of around $5,000 in 1980[1], and the site was set for the predominantly Black community of Afton. Its residents protested for six-weeks, leading to over 500 arrests.[36][37]

That the protests in Warren County were led by civilians led to the basis of future and modern-day environmental, grassroots organizations fighting for environmental justice. Rev. Benjamin Chavis was serving for the United Church of Christ (UCC) Commission for Racial Justice when he was sent to Warren County for the protests. Chavis was among the 500 arrested for taking part in the nonviolent protests and is credited with having coined the term "environmental racism" while in the Warren County jail.[38] His involvement, alongside Rev. Leon White, who also served for the UCC, laid the foundation for more activism and consciousness-raising.[39] Chavis would later recall in a New Yorker's article titled "Fighting Environmental Racism in North Carolina" that while "Warren County made headlines … [he] knew in the eighties you couldn't just say there was discrimination. You had to prove it."[40] Fighting for change, not recognition, is an additional factor of environmental justice as a social movement.

In response to the Warren County Protests, two cross-sectional studies were conducted to determine the demographics of those exposed to uncontrolled toxic waste sites and commercial hazardous waste facilities. The United Church of Christ's Commission for Racial Justice studied the placement of hazardous waste facilities in the US and found that race was the most important factor predicting placement of these facilities.[41] These studies were followed by widespread objections and lawsuits against hazardous waste disposal in poor, generally Black, communities.[42][43] The mainstream environmental movement began to be criticized for its predominately white affluent leadership, emphasis on conservation, and failure to address social equity concerns.[44][45]

The EPA established the Environmental Equity Work Group (EEWG) in 1990 in response to additional findings by social scientists that "racial minority and low-income populations bear a higher environmental risk burden than the general population' and that the EPA's inspections failed to adequately protect low-income communities of color".[16] In 1992, the EPA published Environmental Equity: Reducing Risks for All Communities - the first time the agency embarked on a systematic examination of environmental risks to communities of color. This acted as their direction of addressing environmental justice.[16]

In 1993 the EPA founded the National Environmental Justice Advisory Council (NEJAC). In 1994 the office's name was changed to the Office of Environmental Justice as a result of public criticism on the difference between equity and justice. SOURCE That same year, President Bill Clinton issued Executive Order 12898, which created the Interagency Working Group on Environmental Justice.[16] The working group sought to address environmental justice in minority populations and low-income populations.[16] David Pellow writes that the executive order "remains the cornerstone of environmental justice regulation in the US, with the EPA as its ventral arbiter".[16]

Emergence of global movement

[edit]Throughout the 1970s and 1980s, grassroots movements and environmental organizations advocated for regulations that increased the costs of hazardous waste disposal in the US and other industrialized nations. However, this led to a surge in exports of hazardous waste to the Global South during the 1980s and 1990s. This global environmental injustice, including the disposal of toxic waste, land appropriation, and resource extraction, sparked the formation of the global environmental justice movement.

Environmental justice as an international subject commenced at the First National People of Color Environmental Leadership Summit in 1991, held in Washington, DC. The four-day summit was sponsored by the United Church of Christ's Commission for Racial Justice. With around 1,100 persons in attendance, representation included all 50 states as well as Puerto Rico, Brazil, Chile, Mexico, Ghana, Liberia, Nigeria, and the Marshall Islands.[46][47] The summit broadened the environmental justice movement beyond its anti-toxins focus to include issues of public health, worker safety, land use, transportation, housing, resource allocation, and community empowerment.[47] The summit adopted 17 Principles of Environmental Justice, which were later disseminated at the 1992 Earth Summit in Rio, Brazil. The 17 Principles have a likeness in the Rio Declaration on Environment and Development.[48]

In the summer of 2002, a coalition of non-governmental organizations met in Bali to prepare final negotiations for the 2002 Earth Summit. Organizations included CorpWatch, World Rainforest Movement, Friends of the Earth International, the Third World Network, and the Indigenous Environmental Network.[49] They sought to articulate the concept of climate justice.[50] During their time together, the organizations codified the Bali Principles of Climate Justice, a 27-point program identifying and organizing the climate justice movement. Meena Raman, Head of Programs at the Third World Network, explained that in their writing they "drew heavily on the concept of environmental justice, with a significant contribution from movements in the United States, and recognized that economic inequality, ethnicity, and geography played roles in determining who bore the brunt of environmental pollution". At the 2007 United Nations Climate Conference, or COP13, in Bali, representatives from the Global South and low-income communities from the North created a coalition titled "Climate Justice Now!". CJN! Issued a series of "genuine solutions" that echoed the Bali Principles.[49]

Initially, the environmental justice movement focused on addressing toxic hazards and injustices faced by marginalized racial groups within affluent nations. However, during the 1991 Leadership Summit, its scope broadened to encompass public health, worker safety, land use, transportation, and other issues. Over time, the movement expanded further to include considerations of gender, international injustices, and intra-group disparities among disadvantaged populations.

Environmental discrimination and conflict

[edit]The environmental justice movement seeks to address environmental discrimination and environmental racism associated with hazardous waste disposal, resource extraction, land appropriation, and other activities.[51] This environmental discrimination results in the loss of land-based traditions and economies,[52] armed violence (especially against women and indigenous people)[53] environmental degradation, and environmental conflict.[54] The global environmental justice movement arises from these local place-based conflicts in which local environmental defenders frequently confront multi-national corporations. Local outcomes of these conflicts are increasingly influenced by trans-national environmental justice networks.[5][6]

There are many divisions along which an unjust distribution of environmental burdens may fall. Within the US, race is the most important determinant of environmental injustice.[55][56] In other countries, poverty or caste (India) are important indicators.[57] Tribal affiliation is also important in some countries.[57] Environmental justice scholars Laura Pulido and David Pellow argue that recognizing environmental racism, as an element stemming from the entrenched legacies of racial capitalism, is crucial to the movement, with white supremacy continuing to shape human relationships with nature and labor.[58][59][60]

Environmental racism

[edit]Environmental racism is a pervasive and complex issue that affects communities all over the world. It is a form of systemic discrimination that is grounded in the intersection of race, class, and environmental factors.[43] At its core, environmental racism refers to the disproportionate exposure of people of color to environmental hazards such as pollution, toxic waste, and other environmental risks. Environmental racism has a long and troubling history, with many examples dating back to the early 20th century. For instance, the practice of "redlining" in the US, which involved denying loans and insurance to communities of colour, often led to these communities being located in areas with high levels of pollution and environmental hazards.[61]

These communities are often located near industrial sites, waste facilities, and other sources of pollution that can have serious health impacts. Today, environmental racism continues to be a significant environmental justice issue, with many low-income communities and communities of colour facing disproportionate exposure to pollution and other environmental risks. This can have serious consequences for the health and well-being of these communities, leading to higher rates of asthma, cancer, and other illnesses.[43] Addressing environmental racism requires a multifaceted approach that tackles the underlying social, economic, and political factors that contribute to its persistence. In the US, The Low country Alliance for Model Communities (LAMC) combats environmental racism by empowering marginalized neighborhoods in North Charleston, South Carolina, using community-based research and collaborative problem-solving to identify solutions to health and environmental disparities.[62] These communities are often located near industrial sites, waste facilities, and other sources of pollution that can have serious health impacts.

Similarly, environmental justice scholars from Latin America and elsewhere advocate to understand this issue through the lens of decolonisation.[63][64] The latter underlies the fact that environmental racism emanates from the colonial projects of the West and its current reproduction of colonial dynamics.

Hazardous waste

[edit]As environmental justice groups have grown more successful in developed countries such as the United States, the burdens of global production have been shifted to the Global South where less-strict regulations make waste disposal cheaper. Export of toxic waste from the US escalated throughout the 1980s and 1990s.[65][51] Many impacted countries do not have adequate disposal systems for this waste, and impacted communities are not informed about the hazards they are being exposed to.[66][67]

The Khian Sea waste disposal incident was a notable example of environmental justice issues arising from international movement of toxic waste. Contractors disposing of ash from waste incinerators in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania illegally dumped the waste on a beach in Haiti after several other countries refused to accept it. After more than ten years of debate, the waste was eventually returned to Pennsylvania.[66] The incident contributed to the creation of the Basel Convention that regulates international movement of toxic waste.[68]

Land appropriation

[edit]Countries in the Global South disproportionately bear the environmental burden of global production and the costs of over-consumption in Western societies. This burden is exacerbated by changes in land use that shift vast tracts of land away from family and subsistence farming toward multi-national investments in land speculation, agriculture, mining, or conservation.[52] Land grabs in the Global South are engendered by neoliberal ideology and differences in legal frameworks, land prices, and regulatory practices that make countries in the Global South attractive to foreign investments.[52] These land grabs endanger indigenous livelihoods and continuity of social, cultural, and spiritual practices. Resistance to land appropriation through transformative social action is also made difficult by pre-existing social inequity and deprivation; impacted communities are often already struggling just to meet their basic needs.

Water

[edit]Access to clean water is an indispensable aspect of human life, yet it remains very unequal, disproportionately affecting marginalized communities globally. The burden of water scarcity is particularly noticeable in impoverished urban settings and remote rural areas where inadequate infrastructure, limited financial resources, and environmental degradation converge to create formidable challenges. Marginalized populations, often already grappling with systemic inequalities, encounter heightened vulnerabilities when it comes to securing safe and reliable water sources. Discriminatory practices can further compound these challenges.[69] The ramifications of limited water access are profound, permeating various facets of daily life, including health, education, and overall well-being. Recognizing and addressing these disparities is not only a matter of justice but also crucial for sustainable development. Consequently, there must be efforts towards implementing inclusive water management strategies that prioritize the specific needs of marginalized communities, ensuring equitable access to this fundamental resource and fostering resilience in the face of global water challenges. One way this has been proposed is through Community Based Participatory Development. When this has been applied, as in the case of the Six Nations Indigenous peoples in Canada working with McMaster University researchers, it has shown how community-led sharing and integrating of science and local knowledge can be partnered in response to water quality.[70]

Resource extraction

[edit]Resource extraction is a prime example of a tool based on colonial dynamics that engenders environmental racism.[71] Hundreds of studies have shown that marginalized communities, often indigenous communities, are disproportionately burdened by the negative environmental consequences of resource extraction.[3] Communities near valuable natural resources are frequently saddled with a resource curse wherein they bear the environmental costs of extraction and a brief economic boom that leads to economic instability and ultimately poverty.[3] Indigenous communities living near valuable natural resources face even more discrimination, since they are in most cases simply displaced from their home.[71] Power disparities between extraction industries and impacted communities lead to acute procedural injustice in which local communities are unable to meaningfully participate in decisions that will shape their lives.

Studies have also shown that extraction of critical minerals, timber, and petroleum may be associated with armed violence in communities that host mining operations.[53] The government of Canada found that resource extraction leads to missing and murdered indigenous women in communities impacted by mines and infrastructure projects such as pipelines.[72] The Environmental Justice Atlas, that documents conflicts of environmental justice, demonstrates multiple conflicts with high violence on indigenous populations around resource extraction.[73]

Unequal exchange

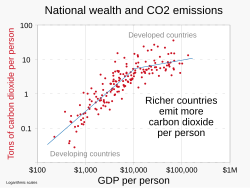

[edit]Unequal exchange is a term used to describe the unequal economic and trade relationship between countries from the Global North and the Global South. The idea is that the exchange of goods and services between these countries is not equal, with Global North countries benefiting more than the others.[74] This occurs for a variety of reasons such as differences in labor costs, technology, and access to resources. Unequal exchange perceives this framework of trade through the lens of decolonisation: colonial power dynamics have led to a trade system where northern countries can trade their knowledge and technology at a very high price against natural resources, materials and labor at a very low price from southern countries.[75] This is kept in place by mechanisms such as enforceable patents, trade regulations and price setting by institutions such as the World Bank or the International Monetary Fund, where northern countries hold most of the voting power.[76] Hence, unequal exchange is a phenomenon that is based on and perpetuates colonial relationships, as it leads to exploitation and enforces existing inequalities between countries of the Global North and Global South. This western paradigm of extraction exacerbates climate change and is a direct result of European colonialism, as it is a continuation of the exploitative ways in which colonization occurred in the past and present. This marginalization especially disadvantages Indigenous women globally in particular, as it superimposes an additional layer of discrimination on an already extensively marginalized group.[77] This interdependence also explains the differences in CO2 emissions between northern and southern countries: evidently, since northern countries use many resources and materials of the South, they produce and pollute more.[78][74]

Health impacts of disparate exposure in EJ communities

[edit]Environmental justice communities that are disproportionately exposed to chemical pollution, reduced air quality, and contaminated water sources may experience overall reduced health.[79] Poverty in these communities can be a factor that increases their exposure to occupational hazards such as chemicals used in agriculture or industry.[80] When workers leave the work environment they may bring chemicals with them on their clothing, shoes, skin, and hair, creating further impacts on their families, including children.[80] Children in EJ communities are uniquely exposed, because they metabolize and absorb contaminants differently than adults.[80] These children are exposed to a higher level of contaminants throughout their lives, beginning in utero (through the placenta), and are at greater risk for adverse health effects like respiratory conditions, gastrointestinal conditions, and mental conditions.[80]

Fast fashion exposes environmental justice communities to occupational hazards such as poor ventilation that can lead to respiratory problems from inhalation of synthetic particles and cotton dust.[81] Textile dyeing can also expose EJ communities to toxins and heavy metals when untreated wastewater enters water systems used by residents and for livestock.[81] 95% of clothing production takes place in low- or middle-income countries where the workers are under-resourced.[81]

Erasure of women

[edit]Though the environmental justice movement seeks to address discrimination, women have historically been discriminated against as the movement evolves from advocacy to institutional change. While grassroots campaigning activities are often dominated by women, gender inequality is more prevalent in institutionalized activities of organizations dominated by salaried professionals.[82] Women have fought back against this trend by establishing their own domestic and international non-governmental organizations, such as the Women's Earth and Climate Action Network (WECAN) and Women's Earth Alliance (WEA).

The US Environmental Protection Agency's definition of environmental injustice does not include gender, instead mentioning environmental injustice to concern race, color, national origin, and income. Gender inequalities in governing bodies have been noted to have an impact on the nature of decisions made, and so consequently federal legislation and discussion surrounding environmental justice often does not include factors of sex. Authors David Pellow and Robert Brulle write in "Environmental justice: human health and environmental inequalities" that environmental injustices "affect human beings unequally along the lines of race, gender, class and nation, so an emphasis on any one of these will dilute the explanatory power of any analytical approach".[82][83]

These inequalities have led to the establishment of the Global Gender and Climate Alliance, set up jointly by the United Nations, the IUCN (International Union for Conservation of Nature), and WEDO (Women, Environment and Development Organization). These have all been founded to raise the profile of gender issues in climate change policymaking.[82]

LGBTQ+ Environmental Justice

[edit]The LGBT+ community experiences environmental injustice in a variety of ways. For instance, the LGBT+ community experiences disproportionately worse living conditions than straight, cisgendered people, as they are more likely to experience identity-based discrimination, rejection from housing opportunities, and higher rents, compared to outside of the community.[84] These poorer housing conditions lead to higher risks of air pollution and a lack of air conditioning. For instance, one study found that neighborhoods with high concentrations of same-sex couples had greater exposure to hazardous air pollutants and a 9.8-13.3% higher risk of respiratory illness. Additionally, the LGBT+ community experiences higher rates of poverty: the poverty rate for the LGBT+ community was 17% in 2021, compared to 12% in non-LGBT+ communities.[85]

These issues are likely to worsen with climate change. As extreme high temperatures and heat waves become more common, the LGBT+ community will be less likely to have access to air conditioning due to higher poverty rates. When there are extreme temperatures, there are higher rates of heat-related deaths through heat stroke, dehydration, and cardiovascular and respiratory diseases.[86] These increased health risks will lead to disparate health burdens on the LGBT+ community, as LGBT+ community members, already experiencing higher poverty and homelessness rates, will likely experience higher rates of heat-related illnesses and deaths than straight, cisgendered people.

Another way that the LGBT+ community experiences environmental injustice is through a lack of support after natural disasters. In the US, the LGBT+ community has a 120% higher risk of experiencing homelessness than those outside the community, with 40% of homeless youth identifying as LGBT.[87] This leaves the community on the front lines of natural disasters.

Additionally, LGBT+ people experience discrimination from natural disaster relief programs. For instance, during Hurricane Katrina, a transgender person was jailed for showering in a women's restroom after being permitted to do so by a relief volunteer. Similarly, after the 2004 Indian Ocean tsunami, the Aravanis (who do not identify as male or female) were excluded from relief programs, temporary shelters, and official death records.[88] These instances of discrimination make it harder for LGBT+ people to recover from natural disasters.

However, LGBT+ community members have created ways to overcome discrimination during natural disasters by creating their own communities of care. For instance, after Hurricane Maria caused severe damage to Puerto Rico, LGBT+ community members created their own food collection drives to provide residents with access to healthy, culturally relevant food. This was done to reduce hunger for a community that experiences higher poverty rates and less support from disaster organization.[89]

In environmental law

[edit]Cost barriers

[edit]One of the prominent barriers to minority participation in environmental justice is the initial costs of trying to change the system and prevent companies from dumping their toxic waste and other pollutants in areas with high numbers of minorities living in them. There are massive legal fees involved in fighting for environmental justice and trying to shed environmental racism.[90] For example, in the United Kingdom, there is a rule that the claimant may have to cover the fees of their opponents, which further exacerbates any cost issues, especially with lower-income minority groups; also, the only way for environmental justice groups to hold companies accountable for their pollution and breaking any licensing issues over waste disposal would be to sue the government for not enforcing rules. This would lead to the forbidding legal fees that most could not afford.[91] This can be seen by the fact that out of 210 judicial review cases between 2005 and 2009, 56% did not proceed due to costs.[92]

Relationships to other movements and philosophies

[edit]Climate justice

[edit]

Climate change and climate justice have also been a component when discussing environmental justice and the greater impact it has on environmental justice communities.[96] Air pollution and water pollution are two contributors of climate change that can have detrimental effects such as extreme temperatures, increase in precipitation, and a rise in sea level.[96][97] Because of this, communities are more vulnerable to events including floods and droughts potentially resulting in food scarcity and an increased exposure to infectious, food-related, and water-related diseases.[96][97][98] Currently, without sufficient treatment, more than 80% of all wastewater generated globally is released into the environment. High-income nations treat, on average, 70% of the wastewater they produce, according to UN Water.[99][100][101]

It has been projected that climate change will have the greatest impact on vulnerable populations.[98]

Climate justice has been influenced by environmental justice, especially grassroots climate justice.[102]

Ocean justice

[edit]The head of "Ocean Collectiv" and "Urban Ocean Lab", marine biologist, Ayana Elizabeth Johnson describes ocean justice as: "where ocean conservation and issues of social equity meet: Who suffers most from flooding and pollution, and who benefits from conservation measures? As sea levels rise and storms intensify, such questions will only grow more urgent, and fairness must be a central consideration as societies figure out how to answer them"[103]

In December 2023 Biden's administration unveiled a whole strategy to improve ocean justice. The main targets of this strategy:

- Repair past injustice when people depending on the ocean and contributing very little to environmental destruction, suffered from the impacts of this destruction on the oceans. Those include Indigenous peoples, African Americans, Hispanic and Latino Americans.

- Use the knowledge of indigenous people and marine communities in general for restore ocean justice and help ocean conservation.

Environmental groups supported the decision. According to Beth Lowell, the vice president of Oceana (non-profit group): "Offshore drilling, fisheries management and reducing plastic pollution are just a few of the areas where these voices are needed".[104]

In the official document summarizing the new strategy, the administration gave several examples of past implementation of those principles. One of them is Mai Ka Po Mai a strategy for the management of the Papahānaumokuākea Marine National Monument near the Hawaiian Islands conceived after consultations with native communities.[105]

Environmentalism

[edit]Relative to general environmentalism, environmental justice is seen as having a greater focus on the lives of everyday people and being more grassroots.[106] Environmental justice advocates have argued that mainstream environmentalist movements have sometimes been racist and elitist.[106][107] This is because the environmental movement was originally composed of White men. People of color were banned from entering national and state parks and other public recreational sites until 1964, severely hindering their ability to participate in the environmental movement. This led to White environmental activists ignoring environmental justice issues like environmental racism.[108] Although more people of color have joined the environmental movement, a 2018 study found that people of color account for only 20% of the staff of environmental organizations despite making up 36% of the overall US population, indicating that barriers still persist.[109]

[i] Added explanation for why the environmental movement has been called racist

Degrowth

[edit]Environmental justice and degrowth have been considered to be complementary movements, because they both seek a political-ecological reorganisation of societies towards sustainability and both are concerned with questions of justice.[110] Scholars have argued that degrowth can support environmental justice by asking for resource caps and implementing policies that reduce the extraction of materials,[111] while fostering relations of care between members of both movements has been proposed as a requirement to achieve their goals.[112] For these reasons, the possibility of an alliance between degrowth and environmental justice has been proposed.[113][114]

The possibility of an alliance, however, remains contested. Scholars from the Global South identify tensions and divergences in their aims and tactics.[115] Similarly, degrowth's emphasis on frugality has led to criticisms of it being a Eurocentric project and unsuitable for social groups in other parts of the world.[116] Ultimately, scholars argue that more research is needed, for example by quantifying the ecological stressors externalized to the Global South, by estimating the effects of degrowth policies,[117] by identifying resonant narratives shared between both movements,[118] and by explicitly integrating an internationalist agenda in degrowth's proposals that supports environmental justice movements in the Global South [119]

Reproductive justice

[edit]Many participants in the Reproductive Justice Movement see their struggle as linked with those for environmental justice, and vice versa. Loretta Ross describes the reproductive justice framework as addressing "the ability of any woman to determine her own reproductive destiny" and argues this is "linked directly to the conditions in her community – and these conditions are not just a matter of individual choice and access."[120] Such conditions include those central to environmental justice – including the siting of toxic waste and pollution of food, air, and waterways.

Mohawk midwife Katsi Cook founded the Mother's Milk Project in the 1980s to address the toxic contamination of maternal bodies through exposure to fish and water contaminated by a General Motors Superfund site. In underscoring how contamination disproportionately impacted Akwesasne women and their children through gestation and breastfeeding, this project illustrates the intersections between reproductive and environmental justice.[121] Cook explains that, "at the breasts of women flows the relationship of those generations both to society and to the natural world."[122]

Ecofeminism

[edit]Ecofeminst find the intersection between environmentalism and feminist philosophy. Ecofeminism is not to be confused with movements or studies on the health impacts of women in the environment. Researcher and author Sarah Buckingham explains that the basis of ecofeminism is rooted in the argument that "women's equality should not be achieved at the expense of worsening the environment, and neither should environmental improvements be gained at the expense of women."[123] Its origins are drawn in feminist theory, feminist spirituality, animal rights, social ecology, and antinuclear, antimilitarist organizing.[124] On account of its range of intersectionality, ecofeminism has been criticized for its incoherency and lack of potential in addressing climate crisis.[125]

Ecofeminist concerns are taken up by feminist researchers who participate in environmental organizations or contribute to national and international debates. Examples of such include the National Women's Health Network's research around industrial and environmental health; critiques of reproductive technology and genetic engineering by the Feminist Network of Resistance to Reproductive and Genetic Engineering (FINRRAGE); and critiques of environmental approaches to population control by the Committee on Women, Population, and the Environment.[124]

Queer Ecology

[edit]Queer ecology is a philosophy that aims to disrupt dominant heteronormative environmental theories and restrictive binaries. The movement began to gain prominence in the mid-1990s, when queer ecology scholarship started to become more mainstream. This research attempted to draw connections between sexual and ecological politics, often based in ecofeminist and environmental justice perspectives. Additionally, queer ecology brings attention to the racialized, gendered, and colonial frameworks that influence how sex and nature are portrayed.[126]

Many LGBT+ environmentalist movements have emerged in response to the growing prominence of the queer ecology scholarship. These include programs skill building initiatives, such as Queer Nature (an organization that provides multi-day courses for building wildlife tracking and survival skills for those in the LGBT+ community) and Out for Sustainability (an organization promotes disaster preparedness and resilience among LGBT+ people). Other LGBT+ environmentalist movements include the Queer Ecojustice Project (an organization that promotes queer ecology and queer ecojustice in communities) and Queers X Climate (an international organization that encourages members to pledge a 50 percent reduction in their carbon emissions).[127]

Queer ecology imagines new futures in scientific research by acknowledging the diversity in the natural world that exists outside of manmade binaries and gender norms. For instance, researchers have discovered that clown fish can change their sex when needed to encourage reproduction. Similarly, researchers have found that female Laysan albatrosses enter same sex relationships to protect their chicks. These organisms existing outside of heteronormative standards can encourage future researchers to gain a better understanding of how species react to population threats, especially as climate change leads to more species extinctions.[128]

Many queer ecology movements exist around the world. For instance, one queer ecology movement in Mexico is breaking down restrictive binaries in agricultural practices. In "A Queer Ecological Reading of Ecocultural Identity in Contemporary Mexico", author Gabriela Méndez Cota describes how plants become viewed as weeds, stating that "a cultural contempt for weeds may come not from Spain in particular but from a Christian agricultural philosophy that makes it difficult to conceive of food as proper if it does not result from an elaborate process of extraction and domestication". However, she explains how queer ecology shifting agricultural perspectives. Due to this shift, some Mexican farmers are allowing for weeds, to continue to grow because they can lead to a healthier biome for milpa and can be used as a source of food and medicine. Queer ecology helps remove these plants from their political and agricultural ideals.[129]

Similarly, queer ecology movements are gaining prominence in the United States. Many queer ecologists in the US are speaking out about how restrictive binaries have harmed scientific research; fungi are typically left out of conservation efforts due to existing outside of the binaries of plants or animals. Additionally, scientists have only recently discovered that many species exist outside of manmade gender norms and are hermaphrodites or intersex. Queer ecologists in the US are encouraging researchers to move away from placing organisms and ecosystems into manmade binaries.[130]

Around the world

[edit]Environmental justice campaigns have arisen from local conflicts all over the world. The Environmental Justice Atlas documented 3,100 environmental conflicts worldwide as of April 2020 and emphasised that many more conflicts remained undocumented.[5]

Africa

[edit]Democratic Republic of the Congo

[edit]Mining for cobalt and copper in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) has resulted in environmental injustice and numerous environmental conflicts including

Conflict minerals mined in the DRC perpetuate armed conflict.

Ethiopia

[edit]Mining for gold and other minerals has resulted in environmental injustice and environmental conflict in Ethiopia including

- Lega Dembi mine: thousands of people were exposed to mercury by MIDROC corporation, resulting in poisoned food, death of livestock and many miscairrages and birth defects.

- Kenticha mine

Kenya

[edit]Kenya has, since independence in 1963, focused on environmental protectionism. Environmental activists such as Wangari Maathai stood for and defend natural and environmental resources, often coming into conflict with the Daniel Arap Moi and his government. The country has suffered Environmental issues arising from rapid urbanization especially in Nairobi, where the public space, Uhuru Park, and game parks such as the Nairobi National Park have suffered encroachment to pave way for infrastructural developments like the Standard Gage Railway and the Nairobi Expressway. One of the environmental lawyers, Kariuki Muigua, has championed environmental justice and access to information and legal protection, authoring the Environmental Justice Thesis on Kenya's milestones.[131]

Nigeria

[edit]From 1956 to 2006, up to 1.5 million tons of oil were spilled in the Niger Delta, (50 times the volume spilled in the Exxon Valdez disaster).[132][133] Indigenous people in the region have suffered the loss of their livelihoods as a result of these environmental issues, and they have received no benefits in return for enormous oil revenues extracted from their lands. Environmental conflicts have exacerbated ongoing conflict in the Niger Delta.[134][135][136]

Ogoni people, who are indigenous to Nigeria's oil-rich Delta region have protested the disastrous environmental and economic effects of Shell Oil's drilling and denounced human rights abuses by the Nigerian government and by Shell. Their international appeal intensified dramatically after the execution in 1995 of nine Ogoni activists, including Ken Saro-Wiwa, who was a founder of the nonviolent Movement for the Survival of the Ogoni People (MOSOP).[137][134][135][136]

South Africa

[edit]Under colonial and apartheid governments in South Africa, thousands of black South Africans were removed from their ancestral lands to make way for game parks. Earthlife Africa was formed in 1988, making it Africa's first environmental justice organisation. In 1992, the Environmental Justice Networking Forum (EJNF), a nationwide umbrella organization designed to coordinate the activities of environmental activists and organizations interested in social and environmental justice, was created. By 1995, the network expanded to include 150 member organizations and by 2000, it included over 600 member organizations.[138]

With the election of the African National Congress (ANC) in 1994, the environmental justice movement gained an ally in government. The ANC noted "poverty and environmental degradation have been closely linked" in South Africa.[attribution needed] The ANC made it clear that environmental inequalities and injustices would be addressed as part of the party's post-apartheid reconstruction and development mandate. The new South African Constitution, finalized in 1996, includes a Bill of Rights that grants South Africans the right to an "environment that is not harmful to their health or well-being" and "to have the environment protected, for the benefit of present and future generations through reasonable legislative and other measures that

- prevent pollution and ecological degradation;

- promote conservation; and

- secure ecologically sustainable development and use of natural resources while promoting justifiable economic and social development".[138]

South Africa's mining industry is the largest single producer of solid waste, accounting for about two-thirds of the total waste stream.[vague] Tens of thousands of deaths have occurred among mine workers as a result of accidents over the last century.[139] There have been several deaths and debilitating diseases from work-related illnesses like asbestosis.[140] For those who live next to a mine, the quality of air and water is poor. Noise, dust, and dangerous equipment and vehicles can be threats to the safety of those who live next to a mine as well.[citation needed] These communities are often poor and black and have little choice over the placement of a mine near their homes. The National Party introduced a new Minerals Act that began to address environmental considerations by recognizing the health and safety concerns of workers and the need for land rehabilitation during and after mining operations. In 1993, the Act was amended to require each new mine to have an Environmental Management Program Report (EMPR) prepared before breaking ground. These EMPRs were intended to force mining companies to outline all the possible environmental impacts of the particular mining operation and to make provision for environmental management.[138]

In October 1998, the Department of Minerals and Energy released a White Paper entitled A Minerals and Mining Policy for South Africa, which included a section on Environmental Management. The White Paper states "Government, in recognition of the responsibility of the State as custodian of the nation's natural resources, will ensure that the essential development of the country's mineral resources will take place within a framework of sustainable development and in accordance with national environmental policy, norms, and standards". It adds that any environmental policy "must ensure a cost-effective and competitive mining industry."[138]

Asia

[edit]Noah Diffenbaugh and Marshall Burke in their study of inequality in Asia demonstrated the interactionalism of economic inequality and global warming. For instance, globalization and industrialization increased the chances of global warming. However, industrialization also allowed wealth inequality to perpetuate. For example, New Delhi is the epicenter of the industrial revolution in the Indian continent, but there is significant wealth disparity. Furthermore, because of global warming, countries like Sweden and Norway can capitalize on warmer temperatures, while most of the world's poorest countries are significantly poorer than they would have been if global warming had not occurred.[141][142]

China

[edit]

In China, factories create harmful waste such as nitrogen oxide and sulfur dioxide which cause health risks. Journalist and science writer Fred Pearce notes that in China "most monitoring of urban air still concentrates on one or at most two pollutants, sometimes particulates, sometimes nitrogen oxides or sulfur dioxides or ozone. Similarly, most medical studies of the impacts of these toxins look for links between single pollutants and suspected health effects such as respiratory disease and cardiovascular conditions."[143] The country emits about a third of all the human-made sulfur dioxide (SO2), nitrogen oxides (NOx), and particulates pollution in the world.[143] The Global Burden of Disease Study, an international collaboration, estimates that 1.1 million Chinese die from the effects of this air pollution each year, roughly a third of the global death toll."[143] The economic cost of deaths due to air pollution is estimated at 267 billion yuan (US$38 billion) per year.[144]

Indonesia

[edit]Environmental conflicts in Indonesia include:

- The Arun gas field where ExxonMobil's development of a natural gas export industry contributed to the insurgency in Aceh in which secessionist fighters led by the Free Aceh Movement attempted to gain independence from the central government which had taken billions in gas revenues from the region without much benefit to the Aceh province. Violence directed toward the gas industry led Exxon to contract with the Indonesian military for protection of the Arun field and subsequent human rights abuses in Aceh.[145]

Malaysia

[edit]Environmental justice movements in Malaysia have arisen from conflicts including:

- Lynas Advanced Materials Plant: rare earth processing plant producing over a million tonnes of radioactive waste from 2012-2023.

South Korea

[edit]Environmental justice movements in South Korea have arisen from conflicts including:

Australia

[edit]

Australia has suffered from a number of environmental injustices, which have usually been caused by polluting corporate projects geared towards extracting natural resources. For example, discriminatory siting of nuclear and hazardous waste facilities.[146][147] These projects have been detrimental to local climates, biodiversity, and the health of local citizen populations from poorer economic areas. They have also faced little resistance from local and national governments, who tend to cite their 'economic' benefits. However, these projects have faced strong resistance from environmental justice organizations, community, and indigenous groups.[148] Australia has a prominent Indigenous population, and they often disproportionately face some of the worst impacts of these projects.

- WestConnex Highway Project, Sydney and New South Wales (NSW)

The WestConnex Highway Project emerged as an answer to Sydney's lack of infrastructure to cope as a fast growing city. The highway project is currently under construction, covers 33 km of new and improved highway, and will link up to the city's M4 and M5 highways.The newest WestConnex toll roads opened in 2019. The NSW government believe that the highway is the 'missing link' to the city's problem of traffic congestion, and has argued that the project will provide further economic benefits such as job creation.

The WestConnex Action Group (WAG) have said that residents close to the highway have been negatively affected by its high levels of air pollution, caused by an increase in traffic and unventilated smokestacks in its tunnels. Protesters have also argued that the close proximity of the highway will put children especially at risk.

The highway has faced resistance in a variety of forms, including a long-running occupation camp in Sydney Park, as well as confrontations with police and construction workers that have led to arrests. The WAG has set up a damage register for people whose property has been damaged by the highway, in order to document the extent of the damages, and support those who have been affected. The WAG have done this through campaigning for a damage repaid fund, independent damage assessment and potential class action.[149]

- Yeelirrie Uranium Mine, Western Australia

The Yeelirrie Uranium Mine was facilitated by Canadian company Cameco. The mine aimed to dig a 9 km open mine pit and destroy 2,400 hectares of traditional lands, including the Seven Sisters Dreaming Songline, important to the Tjiwarl people. The mine has faced strong resistance from the Tjiwral people, especially its women, for over decade.

The mine is the largest uranium deposit in the country, and uses nine million litres of water, whilst generating millions of tonnes of radioactive waste. Around 36 million tonnes of this waste will be produced whilst the mine is operational, which is set to be until 2043.

A group of Tjiwral women took Cameco to court, to initial success. The Environmental Protection Authority (EPA) halted the mine because it was very likely to wipe out several species, including rare stygofauna, the entire western population of a rare saltbush, and harm other wild life like the Malleefowl, Princess parrot and Greater bilby. The state and federal authorities, however, went against the EPA and approved the mine in 2019.[150]

- SANTOS Barossa offshore gas in Timor Sea, Northern Territory (NT)

In March 2021, South Australia Northern Territory Oil Search (SANTOS) invested in the Barossa gas field in the Timor Sea, Northern Territory, to great reception from the NT government, saying that it will provide jobs for the local area. The move was condemned by environmental justice organisations, saying that it will have grave impacts on the climate and biodiversity. Crucially, they stressed that the Tiwi people, owners of the local islands, were not adequately consulted, and were worried that any spills would damage local flatback and Olive Ridley turtle populations.

This disregard for the Tiwi people sparked protests from a number of groups, including one in front of the SANTOS Darwin headquarters demanding an end to the Barossa gas project. In September 2021, a coalition of environmental justice organisations from Australia, South Korea and Japan, united under the name Stop Barossa Gas to oppose the project.[151] In March 2022, the Tiwi people filed for a court injunction to stop KEXIM and Korea Trade and Investment Corporation (Korean development finance institutions) funding the project with almost $1bn. The Tiwi people did this on the basis of a lack of consultation from SANTOS, and the detrimental environmental impacts the project will have. In June 2022, the Tiwi people filed another lawsuit for the same reasons, but this time directly against SANTOS.[152]

Europe

[edit]The European Environment Agency (EEA) reports that exposure to environmental harms such as pollution is correlated with poverty,[153] and that poorer countries suffer from environmental harms while higher income countries produce the majority of the pollution. Western Europe has more extensive evidence of environmental inequality.[153]

Romani peoples are ethnic minorities that experience environmental discrimination. Discriminatory laws force Romani people In many countries to live in slums or ghettos with poor access to running water and sewage, or where they are exposed to hazardous wastes.[154]

The European Union is trying to strive towards environmental justice by putting into effect declarations that state that all people have a right to a healthy environment. The Stockholm Declaration, the 1987 Brundtland Commission's Report – "Our Common Future", the Rio Declaration, and Article 37 of the Charter of Fundamental Rights of the European Union, all are ways that the Europeans have put acts in place to work toward environmental justice.[154]

Sweden

[edit]Sweden became the first country to ban DDT in 1969.[155] In the 1980s, women activists organized around preparing jam made from pesticide-tainted berries, which they offered to the members of parliament.[156][157] Parliament members refused, and this has often been cited as an example of direct action within ecofeminism.

United Kingdom

[edit]Whilst the predominant agenda of the Environmental Justice movement in the United States has been tackling issues of race, inequality, and the environment, environmental justice campaigns around the world have developed and shifted in focus. For example, the EJ movement in the United Kingdom is quite different. It focuses on issues of poverty and the environment, but also tackles issues of health inequalities and social exclusion.[158] A UK-based NGO, named the Environmental Justice Foundation, has sought to make a direct link between the need for environmental security and the defense of basic human rights.[159] They have launched several high-profile campaigns that link environmental problems and social injustices. A campaign against illegal, unreported and unregulated (IUU) fishing highlighted how 'pirate' fisherman are stealing food from local, artisanal fishing communities.[160][161] They have also launched a campaign exposing the environmental and human rights abuses involved in cotton production in Uzbekistan. Cotton produced in Uzbekistan is often harvested by children for little or no pay. In addition, the mismanagement of water resources for crop irrigation has led to the near eradication of the Aral Sea.[162] The Environmental Justice Foundation has successfully petitioned large retailers such as Wal-mart and Tesco to stop selling Uzbek cotton.[163]

Building of alternatives to climate change

[edit]In France, numerous Alternatiba events, or villages of alternatives, are providing hundreds of alternatives to climate change and lack of environmental justice, both in order to raise people's awareness and to stimulate behaviour change. They have been or will be organized in over sixty different French and European cities, such as Bilbao, Brussels, Geneva, Lyon or Paris.

North and Central America

[edit]Belize

[edit]Environmental justice movements arising from local conflicts in Belize include:

- The government of Belize began granting oil concessions without consulting local communities since 2010, with offshore oil drilling being allowed without consultation with local fishermen or the tourism sector, which are the main economic activities in the area, and affecting Mayan and Garifuna communities. Environmental advocacy group, Oceana, collected over 20,000 signatures in 2011 to trigger a national referendum on offshore oil drilling; however, the government of Belize invalidated over 8,000 signatures, preventing the possibility of an official referendum. In response, Oceana and partner organizations organized an unofficial "People's Referendum," which resulted in 90% of Belizeans voting against offshore exploration and drilling. Belize's Supreme Court declared offshore drilling contracts issued by the Government of Belize in 2004 and 2007 invalid in 2013, but the government reconsidered initiating offshore drilling in 2015, with possible new regulations allowing oil and gas exploration in 99% of Belize's territorial waters. In 2022, Oceana began collecting signatures for another moratorium referendum.[164]

- Chalillo Dam

Canada

[edit]Environmental justice movements arising from local conflicts in Canada include:

- Coastal GasLink pipeline

- Fairy Creek timber blockade

- Grassy Narrows road blockade

- Grassy Narrows mercury poisoning

- Trans Mountain pipeline

- Cases of Environmental racism in Nova Scotia

Dominican Republic

[edit]Environmental justice movements arising from local conflicts in the Dominican Republic:

Guatemala

[edit]Environmental justice movements arising from local conflicts in Guatemala include

El Salvador

[edit]Environmental justice movements arising from local conflicts in El Salvador include:

- El Dorado Mine, owned by Pacific Rim Mining Corporation

The Canadian company Pacific Rim Mining Corporation operates a gold mine on the site of El Dorado, San Isidro, in the department of Cabañas. The mine has had hugely negative impacts on the local environment, including the reduction of accessibility to fresh water due to the water intensive mining process, as well as the contamination of the local water supply, which negatively affected the health of local citizens and their live stock. Also, Salvadorian investigators found dangerously high levels of arsenic in two rivers close to the mine.

The operations of the mine has caused conflicts, increased divisions in the community, and prompted threats and violence against opposition to the mine. Following the suspension of the project in 2008 due to resistance from local groups, this violence escalated. As of today, at least half a dozen deaths among local group opposing the mine have been related with the presence of Pacific Rim. The strength of opposition to the mine contributed towards a national movement against the project. In 2008 and 2009, both the incumbent and elected Salvadorian presidents agreed publicly to deny the extension of the licence to Pacific Rim to connote its operations. More recently, the new president Sanchéz Cerén stated "mining is not viable in El Salvador."[165]

Honduras

[edit]Honduras has experienced a number of environmental justice struggles, particularly related to the mining, hydroelectric, and logging industries. One of the most high-profile cases was the assassination of Berta Caceres, a Honduran indigenous and environmental rights activist who opposed the construction of the Agua Zarca Dam on the Gualcarque River. Caceres' murder in 2016 sparked widespread outrage and drew international attention to the risks faced by environmental and indigenous activists in Honduras.[166]

Mexico

[edit]Environmental justice movements arising from local conflicts in Mexico include

Nicaragua

[edit]Environmental justice movements arising from local conflicts in Nicaragua include:

In 2012, the Nicaraguan government approved the construction of the Grand Canal, which will be 286 km long. A large section of the new canal will run through Lake Nicaragua, which is an important source of fresh water for the country. The canal will also have a width of 83 meters, and depth of 27.5 meters, making it suitable for large-range ships. Related infrastructures include two ports, an airport and an oil pipeline.