Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Russian Orthodox Church

View on Wikipedia

Russian Orthodox Church (Moscow Patriarchate) | |

|---|---|

| Русская православная церковь | |

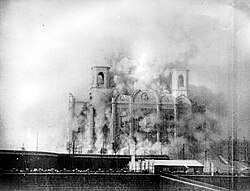

Cathedral of Christ the Saviour in Moscow, Russia | |

| Abbreviation | ROC |

| Type | Autocephaly |

| Classification | Christian |

| Orientation | Eastern Orthodox |

| Scripture | Elizabeth Bible (Church Slavonic) Synodal Bible (Russian) |

| Theology | Eastern Orthodox theology |

| Polity | Episcopal |

| Governance | Holy Synod of the Russian Orthodox Church |

| Structure | Communion |

| Primate | Patriarch Kirill of Moscow |

| Bishops | 382 (2019)[1] |

| Clergy | 40,514 full-time clerics, including 35,677 presbyters and 4,837 deacons[1] |

| Parishes | 38,649 (2019)[1] |

| Dioceses | 314 (2019)[2] |

| Monasteries | 972 (474 male and 498 female) (2019)[1] |

| Associations | World Council of Churches[3] |

| Region | Russia, post-Soviet states, Russian diaspora |

| Language | Church Slavonic (worship), Russian (sermon and paperwork); in addition: languages of national minorities in Russia professing Eastern Orthodoxy; local languages in diaspora (first of all, English) |

| Liturgy | Byzantine Rite |

| Headquarters | Danilov Monastery, Moscow, Russia 55°42′40″N 37°37′45″E / 55.71111°N 37.62917°E |

| Founder | Vladimir the Great[4] |

| Origin | 988 Kievan Rus' |

| Independence | 1448, de facto[5] |

| Recognition |

|

| Separations |

|

| Members | 110 million (95 million in Russia, total of 15 million in the linked autonomous churches)[6][7][8][9] |

| Other names |

|

| Official website | patriarchia.ru |

| Part of a series on the |

| Eastern Orthodox Church |

|---|

| Overview |

The Russian Orthodox Church (ROC; Russian: Русская православная церковь, РПЦ, romanized: Russkaya pravoslavnaya tserkov, RPTs;[a]), also officially known as the Moscow Patriarchate (Russian: Московский патриархат, romanized: Moskovskiy patriarkhat),[10] is an autocephalous Eastern Orthodox Christian church. It has 194 dioceses inside Russia.[11] The primate of the ROC is the patriarch of Moscow and all Rus'.

The history of the ROC begins with the Christianization of Kievan Rus', which commenced in 988 with the baptism of Vladimir the Great and his subjects by the clergy of the ecumenical patriarch of Constantinople.[12][13] Starting in the 14th century, Moscow served as the primary residence of the Russian metropolitan.[14] The ROC declared autocephaly in 1448 when it elected its own metropolitan.[15] In 1589, the metropolitan was elevated to the position of patriarch with the consent of Constantinople.[16] In the mid-17th century, a series of reforms led to a schism in the Russian Church, as the Old Believers opposed the changes.[17]

The ROC currently claims exclusive jurisdiction over the Eastern Orthodox Christians, irrespective of their ethnic background, who reside in the former member republics of the Soviet Union, excluding Georgia. The ROC also created the autonomous Church of Japan and Chinese Orthodox Church. The ROC eparchies in Belarus and Latvia, since the fall of the Soviet Union in the 1990s, enjoy various degrees of self-government, albeit short of the status of formal ecclesiastical autonomy.

The ROC should also not be confused with the Russian Orthodox Church Outside of Russia (or ROCOR, also known as the Russian Orthodox Church Abroad), headquartered in the United States. The ROCOR was instituted in the 1920s by Russian communities outside the Soviet Union, which had refused to recognise the authority of the Moscow Patriarchate that was de facto headed by Metropolitan Sergius Stragorodsky. The two churches reconciled on 17 May 2007; the ROCOR is now a self-governing part of the Russian Orthodox Church.

History

[edit]

Apostle Andrew

[edit]One of the foundational narratives associated with the history of Orthodoxy in Russia is found in the 12th-century Primary Chronicle, which says that the Apostle Andrew visited Scythia and Greek colonies along the northern coast of the Black Sea before making his way to Chersonesus in Crimea.[18][19] According to the legend, Andrew reached the future location of Kiev and foretold the foundation of a great Christian city with many churches.[20] Then, "he came to the [land of the] Slovenians where Novgorod now [stands]" and observed the locals, before eventually arriving in Rome.[21] Despite the lack of historical evidence supporting this narrative, modern church historians in Russia have often incorporated this tale into their studies.[12]

Kievan Rus'

[edit]In the 10th century, Christianity began to take root in Kievan Rus'.[22] Towards the end of the reign of Igor, Christians are mentioned among the Varangians.[23] In the text about the treaty with the Byzantine Empire in 944–945, the chronicler also records the oath-taking ceremony that took place in Constantinople for Igor's envoys as well as the equivalent ceremony that took place in Kiev.[22] Igor's wife Olga was baptized sometime in the mid-10th century; however, scholars have disputed the exact year and place of her conversion, with dates ranging from 946 to 960.[24] Most scholars tend to agree that she was baptized in Constantinople, though some argue that her conversion took place in Kiev.[25] Olga's son Sviatoslav opposed conversion, despite persuasion from his mother,[22] and there is little information about Christianity in sources in the period between 969 and 988.[26]

Ten years after seizing power, Grand Prince Vladimir was baptized in 988 and began Christianizing his people upon his return.[27] That year was decreed by the Russian Orthodox Church in 1988 as the date of the Christianization of the country.[27] According to the Chronicle, Vladimir had previously sent envoys to investigate the different faiths.[27] After receiving glowing reports about Constantinople,[27] he captured Chersonesus in Crimea and demanded that the sister of Basil II be sent there.[28] The marriage took place on the condition that Vladimir would be also baptized there.[28] Vladimir had lent considerable military support to the Byzantine emperor and may have besieged the city due to it having sided with the rebellious Bardas Phokas.[28] By the early 11th century, Christianity was established as the state religion.[29] By the early 13th century, some 40 episcopal sees had been established, all of which ultimately answered to Constantinople.[30]

Transfer of the see to Moscow; de facto independence of the Russian Church

[edit]After Kiev lost its significance following the Mongol invasions, Metropolitan Maximus moved his seat to Vladimir in 1299.[31] His successor, Peter, found himself caught in the conflict between the principalities of Tver and Moscow for supremacy in northwest Russia.[32][33] Peter moved his residence to Moscow in 1325 and became a strong ally of the prince of Moscow.[34] During Peter's tenure in Moscow, the foundation for the Dormition Cathedral was laid and Peter was buried there.[35] By choosing to reside and be buried in Moscow, Peter had designated Moscow as the future center of the Russian Orthodox Church.[34]

Peter was succeeded by Theognostus, who, like his predecessor, pursued policies that supported the rise of the Moscow principality.[36][37] During the first four years of his tenure, the Dormition Cathedral was completed and an additional four stone churches were constructed in Moscow.[36] By the end of 1331, Theognostus was able to restore ecclesiastical control over Lithuania.[38] Theognostus also proceeded with the canonization of Peter in 1339, which helped to increase Moscow's prestige.[36] His successor Alexius lost ecclesiastical over Lithuania in 1355, but kept the traditional title.[39]

On 5 July 1439, at the Council of Florence, the only Russian prelate present at the council signed the union, which, according to his companion, was only under duress.[40] Metropolitan Isidore left Florence on 6 September 1439 and returned to Moscow on 19 March 1441.[41] The chronicles say that three days after arriving in Moscow, Grand Prince Vasily II arrested Isidore and placed him under supervision in the Chudov Monastery.[42] According to the chroniclers of the grand prince, "the princes, the boyars and many others — and especially the Russian bishops — remained silent, slumbered and fell asleep" until "the divinely wise, Christ-loving sovereign, Grand Prince Vasily Vasilyevich shamed Isidor and called him not his pastor and teacher, but a wicked and baneful wolf".[43] Despite the chronicles calling him a heretical apostate, Isidore was recognized as the lawful metropolitan by Vasily II until he left Moscow on 15 September 1441.[43]

For the following seven years, the seat of the metropolitan remained vacant.[44] Vasily II defeated the rebellious Dmitry Shemyaka and returned to Moscow in February 1447.[45] On 15 December 1448, a council of Russian bishops elected Jonah as metropolitan, without the consent of the patriarch of Constantinople, which marked the beginning of autocephaly of the Russian Church.[45] Although not all Russian clergy supported Jonah, the move was subsequently justified in the Russian point of view following the fall of Constantinople in 1453, which was interpreted as divine punishment.[46] While it is possible that the failure to obtain the blessing from Constantinople was not intentional, nevertheless, this marked the beginning of independence of the Russian Church.[47]

Autocephaly and schism

[edit]

Jonah's policy as metropolitan was to recover the areas lost to the Uniate church.[48] He was able to include Lithuania and Kiev to his title, but not Galicia.[48] Lithuania was separated from his jurisdiction in 1458, and the influence of Catholicism increased in those regions.[48] As soon as Vasily II heard about the ordination of Gregory as metropolitan of the newly established metropolis of Kiev, he sent a delegation to the king of Poland warning him not to accept Gregory; Jonah also attempted to persuade feudal princes and nobles who resided in Lithuania to continue to side with Orthodoxy, but this attempt failed.[48]

The fall of Constantinople and the beginning of autocephaly of the Russian Church contributed to political consolidation in Russia and the development of a new identity based on awareness that Moscow was only metropolitanate in the Orthodox oikoumene that remained politically independent.[47] The formulation of the idea of Moscow as the "third Rome" is primarily associated with the monk Philotheus of Pskov, who stated that "Moscow alone shines over all the earth more radiantly than the sun" because of its fidelity to the faith.[47] The marriage of Ivan III to Sophia Palaiologina, the niece of the last Byzantine emperor, and the defeat of the Tatars, helped to solidify this view.[47][49][50]

By the turn of the 16th century, the consolidation of Orthodoxy in Russia continued as Archbishop Gennady of Novgorod created the first complete manuscript translation of the Bible into Church Slavonic in 1499, known as Gennady's Bible.[16] At the same time, two movements within the Russian Church had emerged with differing ecclesial visions.[16] Nilus of Sora (1433–1508) led the non-possessors, who opposed monastic landholding except for the purposes of charity in addition to strong involvement of the church in the affairs of the state, while Joseph of Volotsk (1439–1515) led a movement that supported strong church involvement in the state's affairs.[16] By 1551, the Stoglav Synod addressed the lack of uniformity in existing ecclesial practices.[16] Metropolitan Macarius also collected "all holy books... available in the Russian land" and completed the Grand Menaion, which was influential in shaping the narrative tradition of Russian Orthodoxy.[16] In 1589, during the reign of Feodor I and under the direction of Boris Godunov, the metropolitan of Moscow, Job, was consecrated as the first Russian patriarch with the blessing of Jeremias II of Constantinople.[51][16] In the decree establishing the patriarchate, the whole Russian tsardom is called a "third Rome".[52]

By the mid-17th century, the religious practices of the Russian Orthodox Church were distinct from those of the Greek Orthodox Church.[17] Patriarch Nikon reformed the church in order to bring most of its practices back into accommodation with the contemporary forms of Greek Orthodox worship.[17] Nikon's efforts to correct the translations of texts and institute liturgical reforms were not accepted by all.[17] Archpriest Avvakum accused the patriarch of "defiling the faith" and "pouring wrathful fury upon the Russian land".[17] The result was a schism, with those who resisted the new practices being known as the Old Believers.[17]

In the aftermath of the Treaty of Pereyaslav, the Ottomans, supposedly acting on behalf of the Russian regent Sophia Alekseyevna, pressured the patriarch of Constantinople into transferring the metropolis of Kiev from the jurisdiction of Constantinople to that of Moscow. The handover brought millions of faithful and half a dozen dioceses under the ultimate administrative care of the patriarch of Moscow, and later of the Holy Synod of Russia, leading to a significant Ukrainian presence in the Russian Church, which continued well into the 18th century.[53] The exact terms and conditions of the handover of the metropolis remains a contested issue.[54][55][56][57]

Synodal period

[edit]

Following the death of Patriarch Adrian in 1700, Peter I of Russia (r. 1682–1725) decided against an election of a new patriarch, and drawing on the clergy that came from Ukraine, he appointed Stefan Yavorsky as locum tenens.[58] Peter believed that Russia's resources, including the church, could be used to establish a modern European state and he sought to strengthen the authority of the monarch.[58] He was also inspired by church–state relations in the West and therefore brought the institutional structure of the church in line with other ministries.[59] Theophan Prokopovich wrote Peter's Spiritual Regulation, which no longer legally recognized the separation of the church and the state.[59]

Peter replaced the patriarch with a council known as the Most Holy Synod in 1721, which consisted of appointed bishops, monks, and priests.[59] The church was also overseen by an ober-procurator that would directly report to the emperor.[59] Peter's reforms marked the beginning of the Synodal period of the Russian Church, which would last until 1917.[59] In order to make monasticism more socially useful, Peter began the processes that would eventually lead to the large-scale secularization of monastic landholdings in 1764 under Catherine II.[59][60] 822 monasteries were closed between 1701 and 1805, and monastic communities became highly regulated, receiving funds from the state for support.[59]

The late 18th century saw the rise of starchestvo under Paisiy Velichkovsky and his disciples at the Optina Monastery. This marked a beginning of a significant spiritual revival in the Russian Church after a lengthy period of modernization, personified by such figures as Demetrius of Rostov and Platon of Moscow. Aleksey Khomyakov, Ivan Kireevsky and other lay theologians with Slavophile leanings elaborated some key concepts of the renovated Orthodox doctrine, including that of sobornost. The resurgence of Eastern Orthodoxy was reflected in Russian literature, an example is the figure of Starets Zosima in Fyodor Dostoyevsky's Brothers Karamazov.

In the Russian Orthodox Church, the clergy, over time, formed a hereditary caste of priests. Marrying outside of these priestly families was strictly forbidden; indeed, some bishops did not even tolerate their clergy marrying outside of the priestly families of their diocese.[61]

Fin-de-siècle religious renaissance

[edit]

In 1909, a volume of essays appeared under the title Vekhi ("Milestones" or "Landmarks"), authored by a group of leading left-wing intellectuals, including Sergei Bulgakov, Peter Struve and former Marxists.

It is possible to see a similarly renewed vigor and variety in religious life and spirituality among the lower classes, especially after the upheavals of 1905. Among the peasantry, there was widespread interest in spiritual-ethical literature and non-conformist moral-spiritual movements, an upsurge in pilgrimage and other devotions to sacred spaces and objects (especially icons), persistent beliefs in the presence and power of the supernatural (apparitions, possession, walking-dead, demons, spirits, miracles and magic), the renewed vitality of local "ecclesial communities" actively shaping their own ritual and spiritual lives, sometimes in the absence of clergy, and defining their own sacred places and forms of piety. Also apparent was the proliferation of what the Orthodox establishment branded as "sectarianism", including both non-Eastern Orthodox Christian denominations, notably Baptists, and various forms of popular Orthodoxy and mysticism.[62]

Russian Revolution and Civil War

[edit]In 1914, there were 55,173 Russian Orthodox churches and 29,593 chapels, 112,629 priests and deacons, 550 monasteries and 475 convents with a total of 95,259 monks and nuns in Russia.[63]

The year 1917 was a major turning point in Russian history, and also the Russian Orthodox Church.[64] In early March 1917 (O.S.), the Tsar was forced to abdicate, the Russian empire began to implode, and the government's direct control of the Church was all but over by August 1917. On 15 August (O.S.), in the Moscow Dormition Cathedral in the Kremlin, the Local (Pomestniy) Council of the ROC, the first such convention since the late 17th century, opened. The council continued its sessions until September 1918 and adopted a number of important reforms, including the restoration of Patriarchate, a decision taken 3 days after the Bolsheviks overthrew the Provisional Government in Petrograd on 25 October (O.S.). On 5 November, Metropolitan Tikhon of Moscow was selected as the first Russian Patriarch after about 200 years of Synodal rule.

In early February 1918, the Bolshevik-controlled government of Soviet Russia enacted the Decree on separation of church from state and school from church that proclaimed separation of church and state in Russia, freedom to "profess any religion or profess none", deprived religious organisations of the right to own any property and legal status. Legal religious activity in the territories controlled by Bolsheviks was effectively reduced to services and sermons inside church buildings. The Decree and attempts by Bolshevik officials to requisition church property caused sharp resentment on the part of the ROC clergy and provoked violent clashes on some occasions: on 1 February (19 January O.S.), hours after the bloody confrontation in Petrograd's Alexander Nevsky Lavra between the Bolsheviks trying to take control of the monastery's premises and the believers, Patriarch Tikhon issued a proclamation that anathematised the perpetrators of such acts.[65]

The church was caught in the crossfire of the Russian Civil War that began later in 1918, and church leadership, despite their attempts to be politically neutral (from the autumn of 1918), as well as the clergy generally were perceived by the Soviet authorities as a "counter-revolutionary" force and thus subject to suppression and eventual liquidation.

In the first five years after the Bolshevik revolution, 28 bishops and 1,200 priests were executed.[66]

Soviet period

[edit]

The Soviet Union, formally created in December 1922, was the first state to have elimination of religion as an ideological objective espoused by the country's ruling political party, which held the doctrine of state atheism.[67][68] Toward that end, the Communist regime confiscated church property, ridiculed religion, harassed believers, and propagated materialism and atheism in schools.[69] Actions toward particular religions, however, were determined by State interests, and most organized religions were never outlawed.

Orthodox Christian clergy and active believers, among Christians from other denominations, were treated by the Soviet law-enforcement apparatus as anti-revolutionary elements and were habitually subjected to formal prosecutions on political charges, arrests, exiles, imprisonment in camps, and later could also be incarcerated in mental hospitals.[70][71][72]

However, the Soviet policy vis-a-vis organised religion vacillated over time between, on the one hand, a utopian determination to substitute secular rationalism for what they considered to be an outmoded "superstitious" worldview and, on the other, pragmatic acceptance of the tenaciousness of religious faith and institutions. In any case, religious beliefs and practices did persist, not only in the domestic and private spheres but also in the scattered public spaces allowed by a state that recognized its failure to eradicate religion and the political dangers of an unrelenting culture war.[73]

The Russian Orthodox church was drastically weakened in May 1922, when the Renovated (Living) Church, a reformist movement backed by the Soviet secret police, broke away from Patriarch Tikhon (also see the Josephites and the Russian True Orthodox Church), a move that caused division among clergy and faithful that persisted until 1946.

Between 1917 and 1935, 130,000 Eastern Orthodox priests were arrested. Of these, 95,000 were put to death.[citation needed] Many thousands of victims of persecution became recognized in a special canon of saints known as the "new martyrs and confessors of Russia".[citation needed]

When Patriarch Tikhon died in 1925, the Soviet authorities forbade patriarchal election. Patriarchal locum tenens (acting Patriarch) Metropolitan Sergius (Stragorodsky, 1887–1944), going against the opinion of a major part of the church's parishes, in 1927 issued a declaration accepting the Soviet authority over the church as legitimate, pledging the church's cooperation with the government and condemning political dissent within the church. By this declaration, Sergius granted himself authority that he, being a deputy of imprisoned Metropolitan Peter and acting against his will, had no right to assume according to the XXXIV Apostolic canon, which led to a split with the Russian Orthodox Church Outside Russia abroad and the Russian True Orthodox Church (Russian Catacomb Church) within the Soviet Union, as they allegedly remained faithful to the Canons of the Apostles, declaring the part of the church led by Metropolitan Sergius schism, sometimes coined Sergianism. Due to this canonical disagreement it is disputed which church has been the legitimate successor to the Russian Orthodox Church that had existed before 1925.[74][75][76][77]

In 1927, Metropolitan Evlogy of Paris broke with the ROCOR (along with Metropolitan Platon (Rozhdestvensky) of New York, leader of the Russian Metropolia in America). In 1930, after taking part in a prayer service in London in supplication for Christians suffering under the Soviets, Evlogy was removed from office by Sergius and replaced. Most of Evlogy's parishes in Western Europe remained loyal to him; Evlogy then petitioned Ecumenical Patriarch Photius II to be received under his canonical care and was received in 1931, making a number of parishes of Russian Orthodox Christians outside Russia, especially in Western Europe an Exarchate of the Ecumenical Patriarchate as the Archdiocese of Russian Orthodox churches in Western Europe.

With aid from the Methodist Church, two Russian Orthodox seminaries were reopened in the 1920s as a result of their ecumenical commitments.[78] Moreover, in the 1929 elections, the Orthodox Church attempted to formulate itself as a full-scale opposition group to the Communist Party, and attempted to run candidates of its own against the Communist candidates. Article 124 of the 1936 Soviet Constitution officially allowed for freedom of religion within the Soviet Union, and along with initial statements of it being a multi-candidate election, the Church again attempted to run its own religious candidates in the 1937 elections. However the support of multicandidate elections was retracted several months before the elections were held and in neither 1929 nor 1937 were any candidates of the Orthodox Church elected.[79]

After Nazi Germany's attack on the Soviet Union in 1941, Joseph Stalin revived the Russian Orthodox Church to intensify patriotic support for the war effort. In the early hours of 5 September 1943, Metropolitans Sergius (Stragorodsky), Alexius (Simansky) and Nicholas (Yarushevich) had a meeting with Stalin and received permission to convene a council on 8 September 1943, which elected Sergius Patriarch of Moscow and all the Rus'. This is considered by some as violation of the Apostolic canon, as no church hierarch could be consecrated by secular authorities.[74] A new patriarch was elected, theological schools were opened, and thousands of churches began to function. The Moscow Theological Academy Seminary, which had been closed since 1918, was re-opened.

In December 2017, the Security Service of Ukraine lifted classified top secret status of documents revealing that the NKVD of the USSR and its units were engaged in the selection of candidates for participation in the 1945 Local Council from the representatives of the clergy and the laity. NKVD demanded "to outline persons who have religious authority among the clergy and believers, and at the same time checked for civic or patriotic work". In the letter sent in September 1944, it was emphasized: "It is important to ensure that the number of nominated candidates is dominated by the agents of the NKBD, capable of holding the line that we need at the Council".[80][81]

Persecution under Khrushchev

[edit]A new and widespread persecution of the Christians was subsequently instituted under the leadership of Nikita Khrushchev and Leonid Brezhnev. A second round of repression, harassment and church closures took place between 1959 and 1964 when Nikita Khrushchev was in office. The number of Orthodox churches fell from around 22,000 in 1959 to around 8,000 in 1965;[82] priests, monks and faithful were killed or imprisoned[citation needed] and the number of functioning monasteries was reduced to less than twenty.

Subsequent to Khrushchev's ousting, the Church and the government remained on unfriendly terms[vague] until 1988. In practice, the most important aspect of this conflict was that openly religious people could not join the Communist Party of the Soviet Union, which meant that they could not hold any political office. However, among the general population, large numbers[clarification needed] remained religious.

Some Orthodox believers and even priests took part in the dissident movement and became prisoners of conscience. The Orthodox priests Gleb Yakunin, Sergiy Zheludkov and others spent years in Soviet prisons and exile for their efforts in defending freedom of worship.[83] Among the prominent figures of that time were Dmitri Dudko[84] and Aleksandr Men. Although he tried to keep away from practical work of the dissident movement intending to better fulfil his calling as a priest, there was a spiritual link between Men and many of the dissidents. For some of them he was a friend; for others, a godfather; for many (including Yakunin), a spiritual father.[85][obsolete source][unreliable source?]

According to Metropolitan Vladimir, by 1988 the number of functioning churches in the Soviet Union had fallen to 6,893 and the number of functioning convents and monasteries to just 21.[86][87] In 1987 in the Russian SFSR, between 40% and 50% of newborn babies (depending on the region) were baptized. Over 60% of all deceased received Christian funeral services.[citation needed]

Glasnost and evidence of collaboration with the KGB

[edit]Beginning in the late 1980s, under Mikhail Gorbachev, the new political and social freedoms resulted in the return of many church buildings to the church, so they could be restored by local parishioners. A pivotal point in the history of the Russian Orthodox Church came in 1988, the millennial anniversary of the Christianization of Kievan Rus'. Throughout the summer of that year, major government-supported celebrations took place in Moscow and other cities; many older churches and some monasteries were reopened. An implicit ban on religious propaganda on state TV was finally lifted. For the first time in the history of the Soviet Union, people could watch live transmissions of church services on television.

Gleb Yakunin, a critic of the Moscow Patriarchate who was one of those who briefly gained access to the KGB's archives in the early 1990s, argued that the Moscow Patriarchate was "practically a subsidiary, a sister company of the KGB".[88] Critics charge that the archives showed the extent of active participation of the top ROC hierarchs in the KGB efforts overseas.[89][90][91][92][93][94] George Trofimoff, the highest-ranking US military officer ever indicted for, and convicted of, espionage by the United States and sentenced to life imprisonment on 27 September 2001, had been "recruited into the service of the KGB"[95] by Igor Susemihl (a.k.a. Zuzemihl), a bishop in the Russian Orthodox Church (subsequently, a high-ranking hierarch—the ROC Metropolitan Iriney of Vienna, who died in July 1999).[96]

Konstanin Kharchev, former chairman of the Soviet Council on Religious Affairs, explained: "Not a single candidate for the office of bishop or any other high-ranking office, much less a member of the Holy Synod, went through without confirmation by the Central Committee of the CPSU and the KGB".[92] Professor Nathaniel Davis points out: "If the bishops wished to defend their people and survive in office, they had to collaborate to some degree with the KGB, with the commissioners of the Council for Religious Affairs, and with other party and governmental authorities".[97] Patriarch Alexy II, acknowledged that compromises were made with the Soviet government by bishops of the Moscow Patriarchate, himself included, and he publicly repented for these compromises.[98][99]

Post-Soviet era

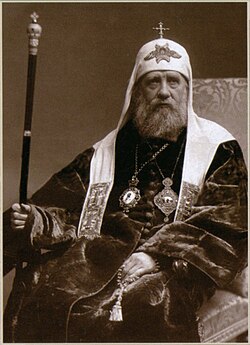

[edit]Patriarch Aleksey II (1990–2008)

[edit]

Metropolitan Alexy (Ridiger) of Leningrad, ascended the patriarchal throne in 1990 and presided over the partial return of Orthodox Christianity to Russian society after 70 years of repression, transforming the ROC to something resembling its pre-communist appearance; some 15,000 churches had been re-opened or built by the end of his tenure, and the process of recovery and rebuilding has continued under his successor Patriarch Kirill. According to official figures, in 2016 the Church had 174 dioceses, 361 bishops, and 34,764 parishes served by 39,800 clergy. There were 926 monasteries and 30 theological schools.[100]

The Russian Church also sought to fill the ideological vacuum left by the collapse of Communism and even, in the opinion of some analysts, became "a separate branch of power".[101]

In August 2000, the ROC adopted its Basis of the Social Concept[102] and in July 2008, its Basic Teaching on Human Dignity, Freedom and Rights.[103]

Under Patriarch Aleksey, there were difficulties in the relationship between the Russian Orthodox Church and the Vatican, especially since 2002, when Pope John Paul II created a Catholic diocesan structure for Russian territory. The leaders of the Russian Church saw this action as a throwback to prior attempts by the Vatican to proselytize the Russian Orthodox faithful to become Roman Catholic. This point of view was based upon the stance of the Russian Orthodox Church (and the Eastern Orthodox Church) that the Church of Rome is in schism, after breaking off from the Orthodox Church. The Roman Catholic Church, on the other hand, while acknowledging the primacy of the Russian Orthodox Church in Russia, believed that the small Roman Catholic minority in Russia, in continuous existence since at least the 18th century, should be served by a fully developed church hierarchy with a presence and status in Russia, just as the Russian Orthodox Church is present in other countries (including constructing a cathedral in Rome, near the Vatican).

There occurred strident conflicts with the Ecumenical Patriarchate, most notably over the Orthodox Church in Estonia in the mid-1990s, which resulted in unilateral suspension of eucharistic relationship between the churches by the ROC.[104] The tension lingered on and could be observed at the meeting in Ravenna in early October 2007 of participants in the Orthodox–Catholic Dialogue: the representative of the Moscow Patriarchate, Bishop Hilarion Alfeyev, walked out of the meeting due to the presence of representatives from the Estonian Apostolic Orthodox Church which is in the jurisdiction of the Ecumenical Patriarchate. At the meeting, prior to the departure of the Russian delegation, there were also substantive disagreements about the wording of a proposed joint statement among the Orthodox representatives.[105] After the departure of the Russian delegation, the remaining Orthodox delegates approved the form which had been advocated by the representatives of the Ecumenical Patriarchate.[106] The Ecumenical See's representative in Ravenna said that Hilarion's position "should be seen as an expression of authoritarianism whose goal is to exhibit the influence of the Moscow Church. But like last year in Belgrade, all Moscow achieved was to isolate itself once more since no other Orthodox Church followed its lead, remaining instead faithful to Constantinople."[107][108]

Canon Michael Bourdeaux, former president of the Keston Institute, said in January 2008 that "the Moscow Patriarchate acts as though it heads a state church, while the few Orthodox clergy who oppose the church-state symbiosis face severe criticism, even loss of livelihood."[109] Such a view is backed up by other observers of Russian political life.[110] Clifford J. Levy of The New York Times wrote in April 2008: "Just as the government has tightened control over political life, so, too, has it intruded in matters of faith. The Kremlin's surrogates in many areas have turned the Russian Orthodox Church into a de facto official religion, warding off other Christian denominations that seem to offer the most significant competition for worshipers. [...] This close alliance between the government and the Russian Orthodox Church has become a defining characteristic of Mr. Putin's tenure, a mutually reinforcing choreography that is usually described here as working 'in symphony'."[111]

Throughout Patriarch Alexy's reign, the massive program of costly restoration and reopening of devastated churches and monasteries (as well as the construction of new ones) was criticized for having eclipsed the church's principal mission of evangelizing.[112][113]

On 5 December 2008, the day of Patriarch Alexy's death, the Financial Times said: "While the church had been a force for liberal reform under the Soviet Union, it soon became a center of strength for conservatives and nationalists in the post-communist era. Alexei's death could well result in an even more conservative church."[114]

Patriarch Kirill (since 2009)

[edit]

On 27 January 2009, the ROC Local Council elected Metropolitan Kirill of Smolensk Patriarch of Moscow and All Rus′ by 508 votes out of a total of 700.[115] He was enthroned on 1 February 2009.

Patriarch Kirill implemented reforms in the administrative structure of the Moscow Patriarchate: on 27 July 2011 the Holy Synod established the Central Asian Metropolitan District, reorganizing the structure of the Church in Tajikistan, Uzbekistan, Kyrgyzstan and Turkmenistan.[116] In addition, on 6 October 2011, at the request of the Patriarch, the Holy Synod introduced the metropoly (Russian: митрополия, mitropoliya), administrative structure bringing together neighboring eparchies.[117]

Under Patriarch Kirill, the ROC continued to maintain close ties with the Kremlin enjoying the patronage of president Vladimir Putin, who has sought to mobilize Russian Orthodoxy both inside and outside Russia.[118][119] Patriarch Kirill endorsed Putin's election in 2012, referring in February to Putin's tenure in the 2000s as "God's miracle".[120][121] Nevertheless, Russian inside sources were quoted in the autumn 2017 as saying that Putin's relationship with Patriarch Kirill had been deteriorating since 2014 due to the fact that the presidential administration had been misled by the Moscow Patriarchate as to the extent of support for pro-Russian uprising in eastern Ukraine; also, due to Kirill's personal unpopularity he had come to be viewed as a political liability.[122][123][124]

Schism with Constantinople

[edit]In 2018, the Moscow Patriarchate's traditional rivalry with the Patriarchate of Constantinople, coupled with Moscow's anger over the decision to grant autocephaly to the Ukrainian church by the Ecumenical Patriarch, led the ROC to boycott the Holy Great Council that had been prepared by all the Orthodox Churches for decades.[125][126]

The Holy Synod of the ROC, at its session on 15 October 2018, severed full communion with the Ecumenical Patriarchate of Constantinople.[127][128] The decision was taken in response to the move made by the Patriarchate of Constantinople a few days prior that effectively ended the Moscow Patriarchate's jurisdiction over Ukraine and promised autocephaly to Ukraine,[129] the ROC's and the Kremlin's fierce opposition notwithstanding.[118][130][131][132]

While the Ecumenical Patriarchate finalised the establishment of the Orthodox Church of Ukraine on 5 January 2019, the ROC continued to claim that the only legitimate Orthodox jurisdiction in the country, was its branch.[133] Under a law of Ukraine adopted at the end of 2018, the latter was required to change its official title so as to disclose its affiliation with the Russian Orthodox Church based in an "aggressor state".[134][135] On 11 December 2019 the Supreme Court of Ukraine allowed the Ukrainian Orthodox Church of the Moscow Patriarchate (UOC-MP) to retain its name.[136]

In October 2019, the ROC unilaterally severed communion with the Church of Greece following the latter's recognition of the Ukrainian autocephaly.[137] On 3 November, Patriarch Kirill failed to commemorate the Primate of the Church of Greece, Archbishop Ieronymos II of Athens, during a liturgy in Moscow.[138] Additionally, the ROC leadership imposed pilgrimage bans for its faithful in respect of a number of dioceses in Greece, including that of Athens.[139]

On 8 November 2019, the Russian Orthodox Church announced that Patriarch Kirill would stop commemorating the Patriarch of Alexandria and all Africa after the latter and his Church recognized the OCU that same day.[140][141][142]

On 27 September 2021, the ROC established a religious day of remembrance for all Eastern Orthodox Christians which were persecuted by the Soviet regime. This day is the 30 October.[143][144]

Russian invasion of Ukraine

[edit]

Metropolitan Onufriy of Kyiv, primate of the Ukrainian Orthodox Church (Moscow Patriarchate) (UOC-MP) called the war "a disaster" stating that "The Ukrainian and Russian peoples came out of the Dnieper Baptismal font, and the war between these peoples is a repetition of the sin of Cain, who killed his own brother out of envy. Such a war has no justification either from God or from people".[146] He also appealed directly to Putin, asking for an immediate end to the "fratricidal war".[147][148] In April 2022, after the Russian invasion, many UOC-MP parishes signaled their intention to switch allegiance to the Orthodox Church of Ukraine.[149] The attitude and stance of Patriarch Kirill of Moscow to the war is one of the oft quoted reasons.[145] The head of the Russian Orthodox Church in Lithuania, Metropolitan Innocent (Vasilyev), called Patriarch Kirill's "political statements about the war" his "personal opinion".[145] On 7 March 2022, Aleksandrs Kudrjašovs, head of the Latvian Orthodox Church, condemned the Russian invasion of Ukraine.[150]

On 27 February 2022, a group of 286 Russian Orthodox priests published an open letter calling for an end to the war and criticised the suppression of non-violent anti-war protests in Russia.[151] On 6 March 2022, Russian Orthodox priest of Moscow Patriarchate's Kostroma Diocese was fined by Russian authorities for anti-war sermon and stressing the importance of the commandment "Thou shalt not kill".[152] Some priests in the Russian Orthodox Church have publicly opposed the invasion, with some facing arrest under the Russian 2022 war censorship laws.[153][154][155] In Kazakhstan, Russian Orthodox priest Iakov Vorontsov, who signed an open letter condemning the invasion of Ukraine, was forced to resign.[156] Former Russian Orthodox priest Father Grigory Michnov-Vaytenko, head of the Russian Apostolic Church — a recognized religious organization founded by other dissident priests such as Father Gleb Yakunin — said that "The [Russian Orthodox] church now works like the commissars did in the Soviet Union. And people of course see it. People don't like it. Especially after February [2022], a lot of people have left the church, both priests and people who were there for years."[157]

Patriarch Kirill has referred to the 2022 Russian invasion of Ukraine as "current events" and has avoided using terms like war or invasion,[159] thereby complying with Russian censorship law.[160] Kirill approves the invasion, and has blessed the Russian soldiers fighting there. As a consequence, several priests of the Russian Orthodox Church in Ukraine have stopped mentioning Kirill's name during the divine service.[161] The Moscow patriarchate views Ukraine as a part of their "canonical territory". Kirill has said that the Russian army has chosen a very correct way.[162]

Kirill sees gay pride parades as a part of the reason behind Russian warfare against Ukraine.[163] He has said that the war is not physically, but rather metaphysically, important.[164]

Following the Bucha massacre, Kirill said that his faithful should be ready to "protect our home" under any circumstances.[165]

On 6 March 2022 (Forgiveness Sunday holiday), during the liturgy in the Church of Christ the Savior, he justified Russia's attack on Ukraine, stating that it was necessary to side with "Donbas" (i.e. Donetsk and Luhansk People's Republic), where he said there is an ongoing 8-year "genocide" by Ukraine and where, Kirill said, Ukraine wants to enforce gay pride events upon local population. Despite the holiday being dedicated to the concept of forgiveness, Kirill said there can't be forgiveness without delivering "justice" first, otherwise it's a capitulation and weakness.[166] The speech came under international scrutiny, as Kirill parroted President Putin's claim that Russia was fighting "fascism" in Ukraine.[167] Throughout the speech, Kirill did not use the term "Ukrainian", but rather referred to both Russians and Ukrainians simply as "Holy Russians", also claiming Russian soldiers in Ukraine were "laying down their lives for a friend", referencing the Gospel of John.[167]

On 9 March 2022, after the liturgy, he declared that Russia has the right to use force against Ukraine to ensure Russia's security, that Ukrainians and Russians are one people, that Russia and Ukraine are one country, that the West incites Ukrainians to kill Russians to sow discord between Russians and Ukrainians and gives weapons to Ukrainians for this specific purpose, and therefore the West is an enemy of Russia and God.[168]

In a letter to the World Council of Churches (WCC) sent in March 2022, Kirill justified the attack on Ukraine by NATO enlargement, the protection of Russian language, and the establishment of the Orthodox Church of Ukraine. In this letter, he did not express condolences over deaths among Ukrainians.[169][170]

Kirill participated in a Zoom video call with Pope Francis on 16 March 2022, of which Francis stated in an interview[171] that Kirill "read from a piece of paper he was holding in his hand all the reasons that justify the Russian invasion."[172]

Representatives of the Vatican have criticized Kirill for his lack of willingness to seek peace in Ukraine.[173] On 3 April, the former Archbishop of Canterbury Rowan Williams said there was a strong case for expelling the Russian Orthodox Church from the WCC, saying, "When a Church is actively supporting a war of aggression, failing to condemn nakedly obvious breaches of any kind of ethical conduct in wartime, then other Churches do have the right to raise the question ... I am still waiting for any senior member of the Orthodox hierarchy to say that the slaughter of the innocent is condemned unequivocally by all forms of Christianity."[174]

The Russian Orthodox St Nicholas church in Amsterdam, Netherlands, has declared that it is no longer possible to function within the Moscow patriarchate because of the attitude that Kirill has taken to the Russian invasion, and instead requested to join the Ecumenical Patriarchate of Constantinople.[175] The Russian Orthodox Church in Lithuania has declared that they do not share the political views and perception of Kirill and therefore are seeking independence from Moscow.[176]

On 10 April 2022, 200 priests from the Ukrainian Orthodox Church (Moscow Patriarchate) released an open request to the primates of the other autocephalous Eastern Orthodox Churches, asking them to convene a Council of Primates of the Ancient Eastern Churches at the Pan-Orthodox level and try Kirill for the heresy of preaching the "Doctrine of the Russian world" and the moral crimes of "blessing the war against Ukraine and fully supporting the aggressive nature of Russian troops on the territory of Ukraine." They noted that they "can't continue to remain in any form of canonical subordination to the Moscow Patriarch," and requested that the Council of Primates "bring Patriarch Kirill to justice and deprive him of the right to hold the patriarchal throne."[177][178]

When the Ukrainian Orthodox Church (Moscow Patriarchate) removed itself from the Moscow Patriarchate on 27 May 2022, Kirill claimed that the "spirits of malice" wanted to separate the Russian and Ukrainian peoples but they will not succeed.[179] The Ukrainian church released a declaration in which it stated "it had adopted relevant additions and changes to the Statute on the Administration of the Ukrainian Orthodox Church, which testify to the complete autonomy and independence of the Ukrainian Orthodox Church."[180] The church did not publish its new constitution.[181] Although in this Ukrainian Orthodox Church clergymen now claims that 'any provisions that at least somehow hinted at or indicated the connection with Moscow were excluded' the Russian Orthodox Church ignores this and continues to include UOC-MP clerics in its various commissions or working groups despite these individuals not agreeing to this nor even wanting to be included.[182]

Cardinal Kurt Koch, president of the Pontifical Council for Promoting Christian Unity, said that the patriarch's legitimization of the "brutal and absurd war" is "a heresy."[183]

Kirill supported the mobilization of citizens to go to the front in Ukraine, he urged citizens to fulfill their military duty and that if they gave their lives for their country they will be with God in his kingdom.[184][185][186]

North Macedonia and Bulgaria expelled senior members of the Russian Orthodox Church for acts contravening their national security in 2023, raising questions about the church using their position to spy and to spread Russian political propaganda.[187] In 2023 Patriarch Bartholomew criticised the Russian church, which he says is teaching a "theology of war". "This is the theology that the sister Church of Russia began to teach, trying to justify an unjust, unholy, unprovoked, diabolical war against a sovereign and independent country – Ukraine."[188] In January 2024, the senior priest of the Church of the Life-Giving Trinity in Ostankino, Moscow, was removed from his post for calling for peace.[189]

During the World Russian People's Council headed and led by Kirill of late March 2024 a document was approved that stated that the Russian invasion of Ukraine was a "Holy War".[190] The document stated that the war had the goal of "protecting the world from the onslaught of globalism and the victory of the West, which has fallen into Satanism".[190] The document also stated that following the war "the entire territory of modern Ukraine should enter the zone of Russia's exclusive influence".[190] This was to be done so "the possibility of the existence of a Russophobic political regime hostile to Russia and its people on this territory, as well as a political regime controlled from an external center hostile to Russia, should be completely excluded".[190] The document also made reference to the "triunity of the Russian people" and it claimed that Belarusians and Ukrainians "should be recognised only as sub-ethnic groups of the Russians".[190]

On August 20, 2024, the Verkhovna Rada of Ukraine banned the Russian Orthodox Church in Ukraine by adopting the Law of Ukraine "On the Protection of the Constitutional Order in the Sphere of Activities of Religious Organizations".[191][192] Ukrainian religious organizations affiliated with the Russian Orthodox Church will be banned 9 months from the moment the State Service of Ukraine for Ethnopolicy and Freedom of Conscience issues the order, if this religious organization does not sever relations with the Russian Orthodox Church in accordance with Orthodox canon law.[193][194][195] This prohibition did not extend to Eastern Orthodoxy in general, contrary to what some online claims asserted.[196][197]

Structure and organization

[edit]

The ROC constituent parts in other than the Russian Federation countries of its exclusive jurisdiction such as Ukraine, Belarus et al., are legally registered as separate legal entities in accordance with the relevant legislation of those independent states.

Ecclesiastiacally, the ROC is organized in a hierarchical structure. The lowest level of organization, which normally would be a single ROC building and its attendees, headed by a priest who acts as Father superior (Russian: настоятель, nastoyatel), constitute a parish (Russian: приход, prihod). All parishes in a geographical region belong to an eparchy (Russian: епархия—equivalent to a Western diocese). Eparchies are governed by bishops (Russian: епископ, episcop or архиерей, archiereus). There are 261 Russian Orthodox eparchies worldwide (June 2012).

Further, some eparchies may be organized into exarchates (currently the Belarusian exarchate), and since 2003 into metropolitan districts (митрополичий округ), such as the ROC eparchies in Kazakhstan and the Central Asia (Среднеазиатский митрополичий округ).

Since the early 1990s, the ROC eparchies in some newly independent states of the former USSR enjoy the status of self-governing Churches within the Moscow Patriarchate (which status, according to the ROC legal terminology, is distinct from the "autonomous" one): the Estonian Orthodox Church of Moscow Patriarchate, Latvian Orthodox Church, Moldovan Orthodox Church, Ukrainian Orthodox Church (Moscow Patriarchate) (UOC-MP), the last one being virtually fully independent in administrative matters. (Following Russia's 2014 Invasion of Ukraine, the UOC-MP—which held nearly a third of the ROC(MP)'s churches—began to fragment, particularly since 2019, with some separatist congregations leaving the ROC(MP) to join the newly independent Orthodox Church of Ukraine (OCU) despite strident objections from the Moscow Patriarchate and the Russian government.[198][125])

Similar status, since 2007, is enjoyed by the Russian Orthodox Church Outside Russia (previously fully independent and deemed schismatic by the ROC). The Chinese Orthodox Church and the Japanese Orthodox Churches were granted full autonomy by the Moscow Patriarchate, but this autonomy is not universally recognized.

Smaller eparchies are usually governed by a single bishop. Larger eparchies, exarchates, and self-governing Churches are governed by a Metropolitan archbishop and sometimes also have one or more bishops assigned to them.

The highest level of authority in the ROC is vested in the Local Council (Pomestny Sobor), which comprises all the bishops as well as representatives from the clergy and laypersons. Another organ of power is the Bishops' Council (Архиерейский Собор). In the periods between the Councils the highest administrative powers are exercised by the Holy Synod of the Russian Orthodox Church, which includes seven permanent members and is chaired by the Patriarch of Moscow and All Russia, Primate of the Moscow Patriarchate.

Although the Patriarch of Moscow enjoys extensive administrative powers, unlike the Pope, he has no direct canonical jurisdiction outside the Urban Diocese of Moscow[citation needed], nor does he have single-handed authority over matters pertaining to faith as well as issues concerning the entire Orthodox Christian community such as the Catholic-Orthodox split.

Canonical territory

[edit]The Russian Orthodox Church claims the following sixteen countries as its canonical territory:[199]

- Azerbaijan

- Belarus

- China

- Estonia

- Japan

- Kazakhstan

- Kyrgyzstan

- Latvia

- Lithuania

- Moldova

- Mongolia

- Russia

- Tajikistan

- Turkmenistan

- Ukraine

- Uzbekistan

However, these claims are not universally recognized; in particular, the Orthodox Church of Ukraine claims Ukraine as its canonical territory and is recognized as such by the Ecumenical Patriarchate of Constantinople. Similarly, the Romanian Orthodox Church claims Moldova as part of its own canonical territory and the Ecumenical Patriarchate claims Estonia as the autonomous Estonian Apostolic Orthodox Church.

Orthodox Church in America (OCA)

[edit]

The OCA has its origins in a mission established by eight Russian Orthodox monks in Alaska, then part of Russian America, in 1794. This grew into a full diocese of the Russian Orthodox Church after the United States purchased Alaska from Russia in 1867. By the late 19th century, the Russian Orthodox Church had grown in other areas of the United States due to the arrival of immigrants from areas of Eastern and Central Europe, many of them formerly of the Eastern Catholic Churches ("Greek Catholics"), and from the Middle East. These immigrants, regardless of nationality or ethnic background, were united under a single North American diocese of the Russian Orthodox Church.

During the Second World War, the Patriarchate of Moscow unsuccessfully attempted to regain control of the groups which were located abroad. After it resumed its communication with Moscow in the early 1960s, and after it was granted autocephaly in 1970, the Metropolia became known as the Orthodox Church in America.[200] But its autocephalous status is not universally recognized. The Ecumenical Patriarch (who has jurisdiction over the Greek Orthodox Archdiocese of America) and some other jurisdictions have not officially accepted it. The Ecumenical Patriarch and the other jurisdictions remain in communion with the OCA. The Patriarchate of Moscow thereby renounced its former canonical claims in the United States and Canada; it also acknowledged the establishment of an autonomous church in Japan in 1970.

Russian Orthodox Church Outside Russia (ROCOR)

[edit]

Russia's Church was devastated by the repercussions of the Bolshevik Revolution. One of its effects was a flood of refugees from Russia to the United States, Canada, and Europe. The Revolution of 1918 severed large sections of the Russian church—dioceses in America, Japan, and Manchuria, as well as refugees in Europe—from regular contacts with the main church.

On 28 December 2006, it was officially announced that the Act of Canonical Communion would finally be signed between the ROC and ROCOR. The signing took place on 17 May 2007, followed immediately by a full restoration of communion with the Moscow Patriarchate, celebrated by a Divine Liturgy at the Cathedral of Christ the Saviour in Moscow, at which the Patriarch of Moscow and All Russia Alexius II and the First Hierarch of ROCOR concelebrated for the first time.

Under the Act, the ROCOR remains a self-governing entity within the Church of Russia. It is independent in its administrative, pastoral, and property matters. It continues to be governed by its Council of Bishops and its Synod, the council's permanent executive body. The First-Hierarch and bishops of the ROCOR are elected by its council and confirmed by the Patriarch of Moscow. ROCOR bishops participate in the Council of Bishops of the entire Russian Church.

In response to the signing of the act of canonical communion, Bishop Agathangel (Pashkovsky) of Odesa and parishes and clergy in opposition to the Act broke communion with ROCOR, and established ROCA(A).[201] Some others opposed to the Act have joined themselves to other Greek Old Calendarist groups.[202]

Currently both the OCA and ROCOR, since 2007, are in communion with the ROC.

Self-governing branches of the ROC

[edit]

The Russian Orthodox Church has four levels of self-government.[203][204][clarification needed]

The autonomous churches which are part of the ROC are:

- Ukrainian Orthodox Church (Moscow Patriarchate), a special status autonomy close to autocephaly

- Self-governed churches (Estonia, Latvia, Moldova, Russian Orthodox Church Outside of Russia)

- Belarusian Orthodox Church, an exarchate; Patriarchal Exarchate in South-East Asia; Patriarchal Exarchate in Western Europe; Patriarchal Exarchate of Africa

- Pakistan Orthodox Church

- Metropolitan District of Kazakhstan

- Japanese Orthodox Church

- Chinese Orthodox Church

Although the Ukrainian Orthodox Church (Moscow Patriarchate) claims that 'any provisions that at least somehow hinted at or indicated the connection with Moscow were excluded' (following the 2022 Russian invasion of Ukraine) the Russian Orthodox Church ignores this and continues to include UOC-MP clerics in various commissions or working groups despite these individuals not agreeing to this nor even wanting to be included.[205]

Worship and practices

[edit]

Canonization

[edit]In accordance with the practice of the Orthodox Church, a particular hero of faith can initially be canonized only at a local level within local churches and eparchies. Such rights belong to the ruling hierarch and it can only happen when the blessing of the patriarch is received. The task of believers of the local eparchy is to record descriptions of miracles, to create the hagiography of a saint, to paint an icon, as well as to compose a liturgical text of a service where the saint is canonized. All of this is sent to the Synodal Commission for canonization which decides whether to canonize the local hero of faith or not. Then the patriarch gives his blessing and the local hierarch performs the act of canonization at the local level. However, the liturgical texts in honor of a saint are not published in all Church books but only in local publications. In the same way, these saints are not yet canonized and venerated by the whole Church, only locally. When the glorification of a saint exceeds the limits of an eparchy, then the patriarch and Holy Synod decides about their canonization on the Church level. After receiving the Synod's support and the patriarch's blessing, the question of glorification of a particular saint on the scale of the entire Church is given for consideration to the Local Council of the Russian Orthodox Church.

In the period following the revolution, and during the communist persecutions up to 1970, no canonizations took place. In 1970, the Holy Synod decided to canonize a missionary to Japan, Nicholas Kasatkin (1836–1912). In 1977, St. Innocent of Moscow (1797–1879), the Metropolitan of Siberia, the Far East, the Aleutian Islands, Alaska, and Moscow was also canonized. In 1978 it was proclaimed that the Russian Orthodox Church had created a prayer order for Meletius of Kharkov, which practically signified his canonization because that was the only possible way to do it at that time. Similarly, the saints of other Orthodox Churches were added to the Church calendar: in 1962 St. John the Russian, in 1970 St. Herman of Alaska, in 1993 Silouan the Athonite, the elder of Mount Athos, already canonized in 1987 by the Ecumenical Patriarchate of Constantinople. In the 1980s the Russian Orthodox Church re-established the process for canonization; a practice that had ceased for half a century.

In 1989, the Holy Synod established the Synodal Commission for canonization. The 1990 Local Council of the Russian Orthodox Church gave an order for the Synodal Commission for Canonisation to prepare documents for canonization of new martyrs who had suffered from the 20th century Communist repressions. In 1991 it was decided that a local commission for canonization would be established in every eparchy which would gather the local documents and would send them to the Synodal Commission. Its task was to study the local archives, collect memories of believers, record all the miracles that are connected with addressing the martyrs. In 1992 the Church established 25 January as a day when it venerates the new 20th century martyrs of faith. The day was specifically chosen because on this day in 1918 the Metropolitan of Kiev Vladimir (Bogoyavlensky) was killed, thus becoming the first victim of communist terror among the hierarchs of the Church.

During the 2000 Council of the Russian Orthodox Church, the greatest general canonization in the history of the Orthodox Church took place: not only regarding the number of saints but also as in this canonization, all unknown saints were mentioned. There were 1,765 canonized saints known by name and others unknown by name but "known to God".[206]

Icon painting

[edit]

The use and making of icons entered Kievan Rus' following its conversion to Orthodox Christianity in AD 988. As a general rule, these icons strictly followed models and formulas hallowed by Byzantine art, led from the capital in Constantinople. As time passed, the Russians widened the vocabulary of types and styles far beyond anything found elsewhere in the Orthodox world. Russian icons are typically paintings on wood, often small, though some in churches and monasteries may be much larger. Some Russian icons were made of copper.[207] Many religious homes in Russia have icons hanging on the wall in the krasny ugol, the "red" or "beautiful" corner. There is a rich history and elaborate religious symbolism associated with icons. In Russian churches, the nave is typically separated from the sanctuary by an iconostasis (Russian ikonostas, иконостас), or icon-screen, a wall of icons with double doors in the centre. Russians sometimes speak of an icon as having been "written", because in the Russian language (like Greek, but unlike English) the same word (pisat', писать in Russian) means both to paint and to write. Icons are considered to be the Gospel in paint, and therefore careful attention is paid to ensure that the Gospel is faithfully and accurately conveyed. Icons considered miraculous were said to "appear". The "appearance" (Russian: yavlenie, явление) of an icon is its supposedly miraculous discovery. "A true icon is one that has 'appeared', a gift from above, one opening the way to the Prototype and able to perform miracles".[208]

Ecumenism and interfaith relations

[edit]

In May 2011, Hilarion Alfeyev, the Metropolitan of Volokolamsk and head of external relations for the Moscow Patriarchate of the Russian Orthodox Church, stated that Orthodox and Evangelical Christians share the same positions on "such issues as abortion, the family, and marriage" and desire "vigorous grassroots engagement" between the two Christian communions on such issues.[209]

The Metropolitan also believes in the possibility of peaceful coexistence between Islam and Christianity because the two religions have never fought religious wars in Russia.[210] Alfeyev stated that the Russian Orthodox Church "disagrees with atheist secularism in some areas very strongly" and "believes that it destroys something very essential about human life."[210]

Today, the Russian Orthodox Church has ecclesiastical missions in Jerusalem and some other countries around the world.[211][212]

Membership

[edit]

The ROC is often said[213] to be the largest of all of the Eastern Orthodox churches in the world. Including all the autocephalous churches under its supervision, its adherents number more than 112 million worldwide—about half of the 200 to 220 million[9][214] estimated adherents of the Eastern Orthodox Church. Among Christian churches, the Russian Orthodox Church is only second to the Roman Catholic Church in terms of numbers of followers. Within Russia the results of a 2007 VTsIOM poll indicated that about 75% of the population considered itself Orthodox Christian.[215] Up to 65% of ethnic Russians[216][217] as well as Russian-speakers from Russia who are members of other ethnic groups (Ossetians, Chuvash,[218] Caucasus Greeks, Kryashens[219] etc.) and a similar percentage of Belarusians and Ukrainians identify themselves as "Orthodox".[215][216] However, according to a poll published by the church related website Pravmir.com in December 2012, only 41% of the Russian population identified itself with the Russian Orthodox Church.[220] Pravmir.com also published a 2012 poll by the respected Levada organization VTsIOM indicating that 74% of Russians considered themselves Orthodox.[221] The 2017 Survey Religious Belief and National Belonging in Central and Eastern Europe made by the Pew Research Center showed that 71% of Russians declared themselves as Orthodox Christian,[222] and in 2021, the Russian Public Opinion Research Center (VCIOM) estimated that 66% of Russians were Orthodox Christians.[223]

In 2017, Pew Research published research indicating that only 6% of Russian Orthodox Church members attend services "at least weekly."[224] The same study also found that 15% of Russian Orthodox say religion is "very important" in their lives and 18% say that they pray daily; a much larger number, 87% of Russian Orthodox, say that they keep icons at home.[224]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ Church Slavonic: Рꙋ́сскаѧ правосла́внаѧ цр҃ковь

Citations

[edit]- ^ a b c d "Внутренняя жизнь и внешняя деятельность Русской Православной Церкви с 2009 года по 2019 год". www.patriarchia.ru (in Russian).

- ^ "Доклад Святейшего Патриарха Кирилла на Епархиальном собрании г. Москвы (20 декабря 2019 года) / Патриарх / Патриархия.ru". www.patriarchia.ru (in Russian).

- ^ "Russian Orthodox Church (Moscow Patriarchate)". World Council of Churches. January 1961. Retrieved 25 December 2022.

- ^ Voronov, Theodore (13 October 2001). "The Baptism of Russia and Its Significance for Today". orthodox.clara.net. Archived from the original on 18 April 2007. Retrieved 12 July 2007.

- ^ "Primacy and Synodality from an Orthodox Perspective". Retrieved 5 March 2015.

- ^ "Religions in Russia: a New Framework". www.pravmir.com. Archived from the original on 25 December 2012. Retrieved 25 December 2012.

- ^ "Number of Orthodox Church Members Shrinking in Russia, Islam on the Rise - Poll". www.pravmir.com. Archived from the original on 30 May 2013. Retrieved 25 December 2012.

- ^ "Russian Orthodox Church | History & Facts". Encyclopedia Britannica. 27 January 2024.

- ^ a b Brien, Joanne O.; Palmer, Martin (2007). The Atlas of Religion. Univ of California Press. p. 22. ISBN 978-0-520-24917-2.

- ^ "I. Общие положения – Русская православная Церковь". www.patriarchia.ru (in Russian). Retrieved 5 March 2015.

- ^ Hanna, Alfred. "Union Between Christians".

- ^ a b Shevzov 2012, p. 16.

- ^ Robson 2010, p. 1108.

- ^ Shevzov 2012, p. 17.

- ^ Shevzov 2012, pp. 18–19.

- ^ a b c d e f g Shevzov 2012, p. 20.

- ^ a b c d e f Shevzov 2012, p. 22.

- ^ Fennell 2014, p. 20, Apostle Andrew, while preaching in the Greek colony of Sinope on the south shore of the Black Sea, decided to journey to Rome... via Cherson in the Crimea.

- ^ Shevzov 2012, p. 16, The history of Orthodoxy in Russia is associated with two foundational narratives. The first relates to its apostolic roots.

- ^ Fennell 2014, p. 20, On the way he stopped first at the site of the future city of Kiev, where, predictably, he prophesied the founding of a great town with many churches.

- ^ Fennell 2014, p. 20.

- ^ a b c Fennell 2014, p. 25.

- ^ Fennell 2014, p. 24.

- ^ Fennell 2014, p. 26, Not that anyone doubts that she was baptized. All are agreed on that. But when, where and under what circumstances? These are the questions that divide the academics.

- ^ Fennell 2014, p. 26.

- ^ Fennell 2014, p. 31.

- ^ a b c d Fennell 2014, p. 35.

- ^ a b c Fennell 2014, p. 37.

- ^ Kent 2021, p. 12.

- ^ Kent 2021, p. 15.

- ^ Fennell 2014, p. 134.

- ^ Fennell 2014, p. 134, Petr arrived in Vladimir from Constantinople in 1309 at the height of the conflict between Tver' and Moscow for supremacy in northwest Russia.

- ^ Meyendorff 2010, p. 149.

- ^ a b Fennell 2014, p. 136.

- ^ Meyendorff 2010, p. 153.

- ^ a b c Meyendorff 2010, p. 156.

- ^ Fennell 2023, p. 192.

- ^ Fennell 2023, p. 134.

- ^ Fennell 2014, p. 141.

- ^ Fennell 2014, p. 175.

- ^ Fennell 2014, pp. 177–179.

- ^ Fennell 2014, p. 180.

- ^ a b Fennell 2014, p. 181.

- ^ Fennell 2014, p. 183.

- ^ a b Fennell 2014, p. 185.

- ^ Shevzov 2012, p. 19, While not all Russian clergymen supported this decision, the move was subsequently justified in Russian eyes by the fall of Constantinople in 1453.

- ^ a b c d Shevzov 2012, p. 19.

- ^ a b c d Shubin 2004, pp. 132–133.

- ^ Strémooukhoff, Dimitri (1953). "Moscow the Third Rome: Sources of the Doctrine". Speculum. 28 (1): 84–101. doi:10.2307/2847182. JSTOR 2847182. S2CID 161446879.

- ^ Parry, Ken; Melling, David, eds. (1999). The Blackwell Dictionary of Eastern Christianity. Malden, MA: Blackwell Publishing. p. 490. ISBN 978-0-631-23203-2.

- ^ McGuckin, John Anthony (3 February 2014). The Concise Encyclopedia of Orthodox Christianity. John Wiley & Sons. p. 405. ISBN 978-1-118-75933-2.

- ^ Rock 2006, p. 272, ...in the decree establishing the Moscow patriarchate in 1589, the whole of the 'great Russian Tsarstvo' is called a third Rome.

- ^ Yuri Kagramanov, The war of languages in Ukraine Archived 1 October 2007 at the Wayback Machine", Novy Mir, 2006, № 8

- ^ "РПЦ: вмешательство Константинополя в ситуацию на Украине может породить новые расколы". TACC (in Russian). Retrieved 25 December 2022.

- ^ "Ecumenical Patriarch Takes Moscow Down a Peg Over Church Relations With Ukraine". orthodoxyindialogue.com. 2 July 2018. Retrieved 25 December 2022.

- ^ Ecumenical Patriarch Bartholomew: "As the Mother Church, it is reasonable to desire the restoration of unity for the divided ecclesiastical body in Ukraine" (The Homily by Patriarch Bartholomew I of Constantinople after the memorial service for the late Metropolitan of Perge, Evangelos), The official website of the Ecumenical Patriarchate, 2 July 2018.

- ^ "«Передача» Киевской митрополии Московскому патриархату в 1686 году: канонический анализ". risu.ua. Retrieved 25 December 2022.

- ^ a b Shevzov 2012, p. 23.

- ^ a b c d e f g Shevzov 2012, p. 24.

- ^ Lindsey Hughes, Russia in the Age of Peter the Great (1998) pp. 332–56.

- ^ GAGARIN, Ivan (25 December 1872). "The Russian Clergy. Translated from the French ... By C. Du Gard Makepeace". Retrieved 25 December 2022 – via Google Books.

- ^ A. S. Pankratov, Ishchushchie boga (Moscow, 1911); Vera Shevzov, Russian Orthodoxy on the Eve of Revolution (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2004); Gregory Freeze, 'Subversive Piety: Religion and the Political Crisis in Late Imperial Russia', Journal of Modern History, vol. 68 (June 1996): 308–50; Mark Steinberg and Heather Coleman, eds. Sacred Stories: Religion and Spirituality in Modern Russia (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2007)

- ^ "What role did the Orthodox Church play in the Reformation in the 16th Century?". Living the Orthodox Life. Archived from the original on 29 August 2015. Retrieved 25 August 2015.

- ^ Palmieri, F. Aurelio. "The Church and the Russian Revolution," Part II, The Catholic World, Vol. CV, N°. 629, August 1917.

- ^ "Анафема св. патриарха Тихона против советской власти и призыв встать на борьбу за веру Христову". Retrieved 5 March 2015.

- ^ Ostling, Richard (24 June 2001). "Cross meets Kremlin". TIME Magazine. Archived from the original on 13 August 2007.

- ^ Bailey, Budd (15 July 2018). The Formation and Dissolution of the Soviet Union. Cavendish Square Publishing, LLC. p. 57-58. ISBN 978-1-5026-3565-5.

He reminded the Poles of their religious heritage, and act that was strongly discouraged by the USSR's state atheism doctrine.

- ^ Pospielovsky, Dimitry (1987). A History of Marxist-Leninist Atheism and Soviet Antireligious Policies. Macmillan Publishers. p. 18-20. ISBN 9780312381325.

- ^ Religious Persecution in the Soviet Union (Part II): Hearings before the U.S. House of Representatives Committee on Foreign Affairs, 99th Cong. (1986). https://www.csce.gov/wp-content/uploads/2016/02/19862D072D1020hearing20religious20persecution20in20USSR20part202_0.pdf

- ^ Maren, Jonathon Van (23 March 2023). "The Lutheran martyrs of the Soviet Union". The Bridgehead.

- ^ Father Arseny 1893–1973 Priest, Prisoner, Spiritual Father. Introduction pp. vi–1. St Vladimir's Seminary Press ISBN 0-88141-180-9

- ^ Sullivan, Patricia (26 November 2006). "Anti-Communist Priest Gheorghe Calciu-Dumitreasa". The Washington Post. p. C09.

- ^ John Shelton Curtis, The Russian Church and the Soviet State (Boston: Little Brown, 1953); Jane Ellis, The Russian Orthodox Church: A Contemporary History (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1986); Dimitry V. Pospielovsky, The Russian Church Under the Soviet Regime 1917–1982 (St. Vladimir's Seminary Press, 1984); idem., A History of Marxist–Leninist Atheism and Soviet Anti-Religious Policies (New York; St. Martin's Press, 1987); Glennys Young, Power and the Sacred in Revolutionary Russia: Religious Activists in the Village (University Park: Pennsylvania State University Press, 1997); Daniel Peris, Storming the Heavens: The Soviet League of the Militant Godless (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1998); William B. Husband, "Godless Communists": Atheism and Society in Soviet Russia (DeKalb: Northern Illinois University Press, 2000; Edward Roslof, Red Priests: Renovationism, Russian Orthodoxy, and Revolution, 1905–1946 (Bloomington, Indiana, 2002)

- ^ a b (in Russian) Alekseev, Valery. Historical and canonical reference for reasons making believers leave the Moscow patriarchate. Created for the government of Moldova Archived 29 November 2006 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Talantov, Boris. 1968. The Moscow Patriarchate and Sergianism (English translation).

- ^ Protopriest Yaroslav Belikow. 11 December 2004. The Visit of His Eminence Metropolitan Laurus to the Parishes of Argentina and Venezuela Archived 29 April 2007 at the Wayback Machine."

- ^ "Церковные Церковные Ведомости: Духовное наследие Катакомбной Церкви и Русской Православной Церкви Заграницей - Patriarch Tikhon's Catacomb Church. History of the Russian True Orthodox Church] Ведомости: Духовное наследие Катакомбной Церкви и Русской Православной Церкви Заграницей – Patriarch Tikhon's Catacomb Church. History of the Russian True Orthodox Church". catacomb.org.ua. Retrieved 25 December 2022.

- ^ Rev. Thomas Hoffmann; William Alex Pridemore. "Esau's Birthright and Jacob's Pottage: A Brief Look at Orthodox-Methodist Ecumenism in Twentieth-Century Russia" (PDF). Demokratizatsiya. Archived from the original (PDF) on 29 September 2011. Retrieved 19 October 2009.

The Methodists continued their ecumenical commitments, now with the OC. This involved a continuance of financial assistance from European and American resources, enough to reopen two OC seminaries in Russia (where all had been previously closed). OC leaders wrote in two unsolicited statements: The services rendered... by the American Methodists and other Christian friends will go down in history of the Orthodox Church as one of its brightest pages in that dark and trying time of the church.... Our Church will never forget the Samaritan service which... your whole Church unselfishly rendered us. May this be the beginning of closer friendship for our churches and nations. (as quoted in Malone 1995, 50–51)

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Fitzpatrick, Sheila. 1999. Everyday Stalinism: Ordinary Life in Extraordinary Times: Soviet Russia in the 1930s. New York: Oxford University Press, pp. 179-82.

- ^ "Московський патріархат створювали агенти НКВС, – свідчать розсекречені СБУ документи". espreso.tv.

- ^ "СБУ рассекретила архивы: московского патриарха в 1945 году избирали агенты НКГБ". www.znak.com. Archived from the original on 11 December 2017. Retrieved 11 December 2017.

- ^ Sally, Waller (30 April 2015). Tsarist and Communist Russia 1855–1964 (Second ed.). Oxford. ISBN 9780198354673. OCLC 913789474.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ "Dissent in the Russian Orthodox Church," Russian Review, Vol. 28, N 4, October 1969, pp. 416–27.

- ^ "Fr Dmitry Dudko". The Independent. 30 June 2004. Retrieved 25 December 2022.

- ^ Keston Institute and the Defence of Persecuted Christians in the USSR

- ^ Dunlop, John B. (December 1990). "The Russian Orthodox Church and nationalism after 1988" (PDF). Religion in Communist Lands. 18 (4): 292–306. doi:10.1080/09637499008431483. ISSN 0307-5974.

- ^ Bell, Helen; Ellis, Jane (December 1988). "The millennium celebrations of 1988 in the USSR" (PDF). Religion in Communist Lands. 16 (4): 292–328. doi:10.1080/09637498808431389. ISSN 0307-5974.

- ^ Andrew Higgins (18 December 2007). "Born Again. Putin and Orthodox Church Cement Power in Russia". Wall Street Journal.