Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

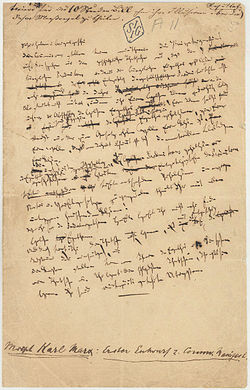

Handwriting

View on WikipediaThis article needs additional citations for verification. (April 2011) |

Handwriting is the personal and unique style of writing with a writing instrument, such as a pen or pencil in the hand. Handwriting includes both block and cursive styles and is separate from generic and formal handwriting script/style, calligraphy or typeface. Because each person's handwriting is unique and different, it can be used to verify a document's writer.[1] The deterioration of a person's handwriting is also a symptom or result of several different diseases. The inability to produce clear and coherent handwriting is also known as dysgraphia.

Uniqueness

[edit]Each person has their own unique style of handwriting, whether it be everyday handwriting or their personal signature. Cultural environment and the characteristics of the written form of the first language that one learns to write are the primary influences on the development of one's own unique handwriting style.[2] Even identical twins who share appearance and genetics do not have the same handwriting.[3]

Characteristics of handwriting include:

- the specific shape of letters, e.g. their roundness or sharpness

- regular or irregular spacing between letters

- the slope of the letters

- the rhythmic repetition of the elements or arrhythmia

- the pressure to the paper

- the average size of letters

- the thickness of letters

- the spacing between letters, words and sentences

Medical conditions

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (October 2021) |

Developmental dysgraphia is very often accompanied by other learning and/or neurodevelopmental disorder[4] like ADHD. Similarly, people with ADD/ADHD have higher rates of dyslexia.[medical citation needed] It is unknown how many individuals with ADD/ADHD who also struggle with penmanship actually have undiagnosed specific learning disabilities like developmental dyslexia or developmental dysgraphia causing their handwriting difficulties.[medical citation needed]

Children with ADHD have been found to be more likely to have less legible handwriting, make more spelling errors, more insertions and/or deletions of letters and more corrections. In children with these difficulties, the letters tend to be larger with wide variability of letters, letter spacing, word spacing, and the alignment of letters on the baseline. Variability of handwriting increases with longer texts. Fluency of the movement is normal but children with ADHD were more likely to make slower movements during the handwriting task and hold the pen longer in the air between movements, especially when they had to write complex letters, implying that planning the movement may take longer. Children who have ADHD were more likely to have difficulty parameterising movements in a consistent way. This has been explained with motor skill impairment either due to lack of attention or lack of inhibition. To anticipate a change of direction between strokes, constant visual attention is essential. With inattention, changes will occur too late, resulting in higher letters and poor alignment of letters on the baseline. The influence of medication on the quality of handwriting is not clear.[5]

Graphology

[edit]Graphology is the pseudoscientific[6][7][8] study and analysis of handwriting in relation to human psychology. Graphology is primarily used as a recruiting tool in the applicant screening process for predicting personality traits and job performance, despite research showing consistently null correlations for these uses.[9][10][11]

Handwriting recognition

[edit]

Pedagogy

[edit]Significance in education

[edit]

As pen-and-paper assignments remain common throughout the century, handwriting practice exercises are still issued by instructors worldwide because handwriting is recognized as a primary tool for the communication of ideas. In order for handwriting to be efficiently utilized by students, it is ideal for the process to be familiar and automatic.[14] The letter-writing skill can reflect the beginnings of orthographic knowledge well, and this knowledge has been shown to be important to spelling in older children.[15] Better letter recognition can be facilitated by practicing handwriting in late preschool, as studies suggest that elementary students benefit from explicit handwriting instruction. With sufficient practice, legibility tends to improve over time.[16]

Additionally, research indicates that handwriting production is more cognitively costly and challenging for children than oral language production.[17] Poor handwriting skills and autonomy have been shown to often impair higher-level cognition and creative thinking in children, leading them to become labelled by their instructors as dysgraphic or clumsy.[18] Meta-analysis of classroom assignments also found that the legibility of handwriting affects the grading of work as clearer handwriting tends to receive better marks than illegible or messier handwriting, the phenomenon of which has been coined "the presentation effect."[19]

Also, it was found that movements through handwriting help children organize their perceptions and improve their ability to recognize letters by shaping their spatial understanding.[20] In further study, because of the implied importance of handwriting to academic success, considerable research has been conducted into the efficacy of a variety of teaching methods. When quantifying writing fluency through parameters such as writing speed and duration of intermissions, teaching handwriting through digital tablets/technology, individualized instruction, and rote motor practice produced statistically significant increases in legibility and writing fluency which were able to be quantified.[19][21]

Students with different levels of handwriting ability, including those with physical challenges, showed greater improvements in manuscript handwriting after receiving instruction through a computer-based system, compared to traditional methods.[22]

Cognitive processes in writers

[edit]Children with specific learning disorders, such as poor/slow handwriting, have been observed in psychological study to follow specific mental frameworks which instructors can use to help pinpoint weakness in linguistic skill and develop their students' fluency and writing composition. The Hayes & Berninger framework is a stratified web of interconnected thought processes which relate different cognitive processes to each other in their function of writing in general, and this framework has seen considerable use in pedagological research.[23] For example, underdevelopment of long-term memory, which is in the lower "resource level" of cognitive strata, can then be linked to underdeveloped motor planning for hand-writing individual letters, which bottleneck higher-order cognitive processes such as sentence structure and other critical thinking.[23]

Phenomenology

[edit]For a wide variety of writers, writing by hand has been described as a process which enhances expressivity and the discovery of individuality. The act of writing has been described as more "intimate", and the physical manipulation of a writing utensil on another physical medium, such as paper and pen, has been asserted to be more effective in conveying personal experiences and creating writing as art.[24] In comparison to technological methods of printing writing, such as with a typewriter or a word processor, handwriting is said to be less impersonal and distancing by writers such as Pablo Neruda and William Barrett. Among many writers who agree with such viewpoints, the sensuality, touch, feel and materiality of handwriting seem to all contribute to a bodily experience which allegedly enhance creative writing.[24]

See also

[edit]- Asemic writing – Wordless open semantic form of writing

- Bastarda – Blackletter script used in France and Germany

- Blackletter – Historic European script and typeface

- Block letters – Style of writing Latin script

- Book hand – Legible handwriting style

- Calligraphy – Visual art related to writing

- Chancery hand – Two styles of historic handwriting

- Court hand – Style of handwriting used in medieval English law courts

- Cursive – Style of penmanship

- Handwriting movement analysis – Analysis of handwriting and drawing

- History of writing

- Italic script – Style of handwriting and calligraphy developed in Italy

- Literacy – Ability to read and write

- Manuscript – Document written by hand

- Palaeography – Study of handwriting and manuscripts

- Penmanship – Technique of writing with the hand

- Ronde script (calligraphy) – Sixteenth-century handwriting script

- Rotunda (script) – Medieval blackletter script

- Round hand – Type of handwriting

- Secretary hand – Style of European handwriting

- Shakespeare's handwriting

- Signature – Mark made as a proof of identity and intent

References

[edit]- ^ Huber, Roy A.; Headrick, A.M. (April 1999), Handwriting Identification: Facts and Fundamentals, New York: CRC Press, p. 84, ISBN 978-0-8493-1285-4, archived from the original on 2011-09-28, retrieved 2015-12-27

- ^ Sargur Srihari, Chen Huang and Harish Srinivasan (March 2008). "On the Discriminability of the Handwriting of Twins". J Forensic Sci.; 53(2):430–46.

- ^ Tomasz Dziedzic, Ewa Fabianska, and Zuzanna Toeplitz (2007). Handwriting of Monozygotic and Dizygotic Twins. Problems of Forensic Sciences.

- ^ Gargot, Thomas; Asselborn, Thibault; Pellerin, Hugues; Zammouri, Ingrid; Anzalone, Salvatore M.; Casteran, Laurence; Johal, Wafa; Dillenbourg, Pierre; Cohen, David; Jolly, Caroline (2020-09-11). "Acquisition of handwriting in children with and without dysgraphia: A computational approach". PLOS ONE. 15 (9): –0237575. Bibcode:2020PLoSO..1537575G. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0237575. ISSN 1932-6203. PMC 7485885. PMID 32915793.

- ^ Kaiser, M.L.; Schoemaker, M.M.; Albaret, J.M.; Geuze, R.H. (January 2015). "What is the evidence of impaired motor skills and motor control among children with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD)? Systematic review of the literature". Research in Developmental Disabilities. 36: 338–357. doi:10.1016/j.ridd.2014.09.023. PMID 25462494.

- ^ "Barry Beyerstein Q&A". Ask the Scientists. Scientific American Frontiers. Archived from the original on 2007-02-20. Retrieved 2008-02-22. "they simply interpret the way we form these various features on the page in much the same way ancient oracles interpreted the entrails of oxen or smoke in the air. I.e., it's a kind of magical divination or fortune telling where 'like begets like.'"

- ^ James, Barry (3 August 1993). "Graphology Is Serious Business in France : You Are What You Write?". The New York Times. Retrieved 18 September 2010.

- ^ Goodwin, C. James (2010). Research in Psychology: Methods and Design. John Wiley & Sons. p. 36. ISBN 978-0-470-52278-3.

- ^ Roy N. King and Derek J. Koehler (2000), "Illusory Correlations in Graphological Inference", Journal of Experimental Psychology: Applied, 6 (4): 336–348, CiteSeerX 10.1.1.135.8305, doi:10.1037/1076-898X.6.4.336, PMID 11218342.

- ^ Lockowandte, Oskar (1976), "Lockowandte, Oskar Present status of the investigation of handwriting psychology as a diagnostic method", Catalog of Selected Documents in Psychology (6): 4–5.

- ^ Nevo, B Scientific Aspects of Graphology: A Handbook Springfield, IL: Thomas: 1986

- ^ Förstner, Wolfgang (1999). Mustererkennung 1999 : 21. DAGM-Symposium Bonn, 15.-17. September 1999. Joachim M. Buhmann, Annett Faber, Petko Faber. Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer Berlin Heidelberg. ISBN 978-3-642-60243-6. OCLC 913706869.

- ^ Schenk, Joachim (2010). Mensch-maschine-kommunikation : grundlagen von sprach- und bildbasierten benutzerschnittstellen. Gerhard Rigoll. Heidelberg: Springer. ISBN 978-3-642-05457-0. OCLC 609418875.

- ^ Sassoon, Rosemary (1986). "A handwriting for life". Child Language Teaching and Therapy. 2 (1): 20–30. doi:10.1177/026565908600200102. ISSN 0265-6590 – via SAGE Publications.

- ^ Puranik, Cynthia S.; Lonigan, Christopher J.; Kim, Young-Suk (2011-10-01). "Contributions of emergent literacy skills to name writing, letter writing, and spelling in preschool children". Early Childhood Research Quarterly. 26 (4): 465–474. doi:10.1016/j.ecresq.2011.03.002. ISSN 0885-2006. PMC 3172137. PMID 21927537.

- ^ Fancher, Lee Ann; Priestley-Hopkins, Deborah A.; Jeffries, Lynn M. (2018-10-02). "Handwriting Acquisition and Intervention: A Systematic Review". Journal of Occupational Therapy, Schools, & Early Intervention. 11 (4): 454–473. doi:10.1080/19411243.2018.1534634. ISSN 1941-1243.

- ^ Grabowski, Joachim (2009-11-12). "Speaking, writing, and memory span in children: Output modality affects cognitive performance". International Journal of Psychology. 45 (1): 28–39. doi:10.1080/00207590902914051. ISSN 0020-7594.

- ^ Rosenblum, Sara; Weiss, Patrice L.; Parush, Shula (2003). "Product and Process Evaluation of Handwriting Difficulties". Educational Psychology Review. 15 (1): 41–81. ISSN 1040-726X.

- ^ a b Santangelo, Tanya; Graham, Steve (2016). "A Comprehensive Meta-analysis of Handwriting Instruction". Educational Psychology Review. 28 (2): 225–265. ISSN 1040-726X.

- ^ Longcamp, Marieke; Zerbato-Poudou, Marie-Thérèse; Velay, Jean-Luc (May 2005). "The influence of writing practice on letter recognition in preschool children: A comparison between handwriting and typing". Acta Psychologica. 119 (1): 67–79. doi:10.1016/j.actpsy.2004.10.019.

- ^ Graham, Steve; Weintraub, Naomi (1996-03-01). "A review of handwriting research: Progress and prospects from 1980 to 1994". Educational Psychology Review. 8 (1): 7–87. doi:10.1007/BF01761831. ISSN 1573-336X.

- ^ Graham, Steve; Weintraub, Naomi (March 1996). "A review of handwriting research: Progress and prospects from 1980 to 1994". Educational Psychology Review. 8 (1): 7–87. doi:10.1007/BF01761831. ISSN 1040-726X.

- ^ a b O’Rourke, Lynsey; Connelly, Vincent; Barnett, Anna (2018), Connelly, Vincent; Miller, Brett; McCardle, Peggy (eds.), "Understanding Writing Difficulties through a Model of the Cognitive Processes Involved in Writing", Writing Development in Struggling Learners, Understanding the Needs of Writers across the Lifecourse, vol. 35, Brill, pp. 11–28, doi:10.1163/j.ctv3znwkm.5, retrieved 2023-03-13

- ^ a b Chandler, Daniel (1992-05-01). "The phenomenology of writing by hand". Intelligent Tutoring Media. 3 (2–3): 65–74. doi:10.1080/14626269209408310. ISSN 0957-9133.

Further reading

[edit]- Douglas, A. (2017). Work in hand: script, print, and writing, 1690-1840. Oxford University Press.

- Gaze, T. & Jacobson, M. (editors), (2013). An Anthology of Asemic Handwriting. Uitgeverij. ISBN 978-9081709170

- Giesbrecht, Josh (28 August 2015). "How The Ballpoint Pen Killed Cursive". The Atlantic. Retrieved August 28, 2015.

- Hofer, Philip, and John Howard Benson. 1953. The art of handwriting: a loan exhibition of writing books and manuscripts from the collections of Philip Hofer, Harvard University, and John Howard Benson. [Providence]: Rhode Island School of Design, Museum of Art.

- Kaiser, M.-L.; Schoemaker, M.M.; Albaret, J.-M.; Geuze, R.H. (2015). "What is the evidence of impaired motor skills and motor control among children with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD)? Systematic review of the literature". Research in Developmental Disabilities. 36: 338–357. doi:10.1016/j.ridd.2014.09.023. PMID 25462494. Retrieved January 1, 2015.

- Thornton, Tamara Plakins (1998). Handwriting in America: A Cultural History. Yale University Press.

- Renton, Alexander Wood (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 12 (11th ed.). p. 916.