Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Health system

View on Wikipedia

A health system, health care system or healthcare system is an organization of people, institutions, and resources that delivers health care services to meet the health needs of target populations.

There is a wide variety of health systems around the world, with as many histories and organizational structures as there are countries. Implicitly, countries must design and develop health systems in accordance with their needs and resources, although common elements in virtually all health systems are primary healthcare and public health measures.[1]

In certain countries, the orchestration of health system planning is decentralized, with various stakeholders in the market assuming responsibilities. In contrast, in other regions, a collaborative endeavor exists among governmental entities, labor unions, philanthropic organizations, religious institutions, or other organized bodies, aimed at the meticulous provision of healthcare services tailored to the specific needs of their respective populations. Nevertheless, it is noteworthy that the process of healthcare planning is frequently characterized as an evolutionary progression rather than a revolutionary transformation.[2][3]

As with other social institutional structures, health systems are likely to reflect the history, culture and economics of the states in which they evolve. These peculiarities bedevil and complicate international comparisons and preclude any universal standard of performance.

Goals

[edit]According to the World Health Organization (WHO), the directing and coordinating authority for health within the United Nations system, healthcare systems' goals are good health for the citizens, responsiveness to the expectations of the population, and fair means of funding operations. Progress towards them depends on how systems carry out four vital functions: provision of health care services, resource generation, financing, and stewardship.[4] Other dimensions for the evaluation of health systems include quality, efficiency, acceptability, and equity.[2] They have also been described in the United States as "the five C's": Cost, Coverage, Consistency, Complexity, and Chronic Illness.[5] Also, continuity of health care is a major goal.[6]

Definitions

[edit]Often health system has been defined with a reductionist perspective. Some authors[7] have developed arguments to expand the concept of health systems, indicating additional dimensions that should be considered:

- Health systems should not be expressed in terms of their components only, but also of their interrelationships;

- Health systems should include not only the institutional or supply side of the health system but also the population;

- Health systems must be seen in terms of their goals, which include not only health improvement, but also equity, responsiveness to legitimate expectations, respect of dignity, and fair financing, among others;

- Health systems must also be defined in terms of their functions, including the direct provision of services, whether they are medical or public health services, but also "other enabling functions, such as stewardship, financing, and resource generation, including what is probably the most complex of all challenges, the health workforce."[7]

World Health Organization

[edit]The World Health Organization defines health systems as follows:

A health system consists of all organizations, people and actions whose primary intent is to promote, restore or maintain health. This includes efforts to influence determinants of health as well as more direct health-improving activities. A health system is, therefore, more than the pyramid of publicly owned facilities that deliver personal health services. It includes, for example, a mother caring for a sick child at home; private providers; behaviour change programmes; vector-control campaigns; health insurance organizations; occupational health and safety legislation. It includes inter-sectoral action by health staff, for example, encouraging the ministry of education to promote female education, a well-known determinant of better health.[8]

Financial resources

[edit]

There are generally five primary methods of funding health systems:[9]

- general taxation to the state, county or municipality

- national health insurance

- voluntary or private health insurance

- out-of-pocket payments

- donations to charities

| Universal | Non-universal | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Single payer | Multi-payer | Multi-payer | No insurance | |

| Single provider | Beveridge model, Semashko model | |||

| Multiple Providers | National Health Insurance | Bismarck model | Private health insurance | Out-of-pocket |

Most countries' systems feature a mix of all five models. One study[10] based on data from the OECD concluded that all types of health care finance "are compatible with" an efficient health system. The study also found no relationship between financing and cost control.[citation needed] Another study examining single payer and multi payer systems in OECD countries found that single payer systems have significantly less hospital beds per 100,000 people than in multi payer systems.[11]

The term health insurance is generally used to describe a form of insurance that pays for medical expenses. It is sometimes used more broadly to include insurance covering disability or long-term nursing or custodial care needs. It may be provided through a social insurance program, or from private insurance companies. It may be obtained on a group basis (e.g., by a firm to cover its employees) or purchased by individual consumers. In each case premiums or taxes protect the insured from high or unexpected health care expenses.[citation needed]

Through the calculation of the comprehensive cost of healthcare expenditures, it becomes feasible to construct a standard financial framework, which may involve mechanisms like monthly premiums or annual taxes. This ensures the availability of funds to cover the healthcare benefits delineated in the insurance agreement. Typically, the administration of these benefits is overseen by a government agency, a nonprofit health fund, or a commercial corporation.[12]

Many commercial health insurers control their costs by restricting the benefits provided, by such means as deductibles, copayments, co-insurance, policy exclusions, and total coverage limits. They will also severely restrict or refuse coverage of pre-existing conditions. Many government systems also have co-payment arrangements but express exclusions are rare or limited because of political pressure. The larger insurance systems may also negotiate fees with providers.[citation needed]

Many forms of social insurance systems control their costs by using the bargaining power of the community they are intended to serve to control costs in the health care delivery system. They may attempt to do so by, for example, negotiating drug prices directly with pharmaceutical companies, negotiating standard fees with the medical profession, or reducing unnecessary health care costs. Social systems sometimes feature contributions related to earnings as part of a system to deliver universal health care, which may or may not also involve the use of commercial and non-commercial insurers. Essentially the wealthier users pay proportionately more into the system to cover the needs of the poorer users who therefore contribute proportionately less. There are usually caps on the contributions of the wealthy and minimum payments that must be made by the insured (often in the form of a minimum contribution, similar to a deductible in commercial insurance models).[citation needed]

In addition to these traditional health care financing methods, some lower income countries and development partners are also implementing non-traditional or innovative financing mechanisms for scaling up delivery and sustainability of health care,[13] such as micro-contributions, public-private partnerships, and market-based financial transaction taxes. For example, as of June 2011, Unitaid had collected more than one billion dollars from 29 member countries, including several from Africa, through an air ticket solidarity levy to expand access to care and treatment for HIV/AIDS, tuberculosis and malaria in 94 countries.[14]

Payment models

[edit]In most countries, wage costs for healthcare practitioners are estimated to represent between 65% and 80% of renewable health system expenditures.[15][16] There are three ways to pay medical practitioners: fee for service, capitation, and salary. There has been growing interest in blending elements of these systems.[17]

Fee-for-service

[edit]Fee-for-service arrangements pay general practitioners (GPs) based on the service.[17] They are even more widely used for specialists working in ambulatory care.[17]

There are two ways to set fee levels:[17]

- By individual practitioners.

- Central negotiations (as in Japan, Germany, Canada and in France) or hybrid model (such as in Australia, France's sector 2, and New Zealand) where GPs can charge extra fees on top of standardized patient reimbursement rates.

Capitation

[edit]In capitation payment systems, GPs are paid for each patient on their "list", usually with adjustments for factors such as age and gender.[17] According to OECD (Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development), "these systems are used in Italy (with some fees), in all four countries of the United Kingdom (with some fees and allowances for specific services), Austria (with fees for specific services), Denmark (one third of income with remainder fee for service), Ireland (since 1989), the Netherlands (fee-for-service for privately insured patients and public employees) and Sweden (from 1994). Capitation payments have become more frequent in "managed care" environments in the United States."[17]

According to OECD, "capitation systems allow funders to control the overall level of primary health expenditures, and the allocation of funding among GPs is determined by patient registrations". However, under this approach, GPs may register too many patients and under-serve them, select the better risks and refer on patients who could have been treated by the GP directly. Freedom of consumer choice over doctors, coupled with the principle of "money following the patient" may moderate some of these risks. Aside from selection, these problems are likely to be less marked than under salary-type arrangements.'[citation needed]

Salary arrangements

[edit]In several OECD countries, general practitioners (GPs) are employed on salaries for the government.[17] According to OECD, "Salary arrangements allow funders to control primary care costs directly; however, they may lead to under-provision of services (to ease workloads), excessive referrals to secondary providers and lack of attention to the preferences of patients."[17] There has been movement away from this system.[17]

Value-based care

[edit]In recent years, providers have been switching from fee-for-service payment models to a value-based care payment system, where they are compensated for providing value to patients. In this system, providers are given incentives to close gaps in care and provide better quality care for patients. [18]

Information resources

[edit]Sound information plays an increasingly critical role in the delivery of modern health care and efficiency of health systems. Health informatics – the intersection of information science, medicine and healthcare – deals with the resources, devices, and methods required to optimize the acquisition and use of information in health and biomedicine. Necessary tools for proper health information coding and management include clinical guidelines, formal medical terminologies, and computers and other information and communication technologies. The kinds of health data processed may include patients' medical records, hospital administration and clinical functions, and human resources information.[19]

The use of health information lies at the root of evidence-based policy and evidence-based management in health care. Increasingly, information and communication technologies are being utilised to improve health systems in developing countries through: the standardisation of health information; computer-aided diagnosis and treatment monitoring; informing population groups on health and treatment.[20]

Management

[edit]The management of any health system is typically directed through a set of policies and plans adopted by government, private sector business and other groups in areas such as personal healthcare delivery and financing, pharmaceuticals, health human resources, and public health.[citation needed]

Public health is concerned with threats to the overall health of a community based on population health analysis. The population in question can be as small as a handful of people, or as large as all the inhabitants of several continents (for instance, in the case of a pandemic). Public health is typically divided into epidemiology, biostatistics and health services. Environmental, social, behavioral, and occupational health are also important subfields.[citation needed]

Today, most governments recognize the importance of public health programs in reducing the incidence of disease, disability, the effects of ageing and health inequities, although public health generally receives significantly less government funding compared with medicine. For example, most countries have a vaccination policy, supporting public health programs in providing vaccinations to promote health. Vaccinations are voluntary in some countries and mandatory in some countries. Some governments pay all or part of the costs for vaccines in a national vaccination schedule.[citation needed]

The rapid emergence of many chronic diseases, which require costly long-term care and treatment, is making many health managers and policy makers re-examine their healthcare delivery practices. An important health issue facing the world currently is HIV/AIDS.[21] Another major public health concern is diabetes.[22] In 2006, according to the World Health Organization, at least 171 million people worldwide had diabetes. Its incidence is increasing rapidly, and it is estimated that by 2030, this number will double. A controversial aspect of public health is the control of tobacco smoking, linked to cancer and other chronic illnesses.[23]

Antibiotic resistance is another major concern, leading to the reemergence of diseases such as tuberculosis. The World Health Organization, for its World Health Day 2011 campaign, called for intensified global commitment to safeguard antibiotics and other antimicrobial medicines for future generations.[24]

Health systems performance

[edit]

Since 2000, more and more initiatives have been taken at the international and national levels in order to strengthen national health systems as the core components of the global health system. Having this scope in mind, it is essential to have a clear, and unrestricted, vision of national health systems that might generate further progress in global health. The elaboration and the selection of performance indicators are indeed both highly dependent on the conceptual framework adopted for the evaluation of the health systems performance.[26] Like most social systems, health systems are complex adaptive systems where change does not necessarily follow rigid management models.[27] In complex systems path dependency, emergent properties and other non-linear patterns are seen,[28] which can lead to the development of inappropriate guidelines for developing responsive health systems.[29]

Quality frameworks are essential tools for understanding and improving health systems. They help define, prioritize, and implement health system goals and functions. Among the key frameworks is the World Health Organization's building blocks model, which enhances health quality by focusing on elements like financing, workforce, information, medical products, governance, and service delivery. This model influences global health evaluation and contributes to indicator development and research.[30]

The Lancet Global Health Commission's 2018 framework builds upon earlier models by emphasizing system foundations, processes, and outcomes, guided by principles of efficiency, resilience, equity, and people-centeredness. This comprehensive approach addresses challenges associated with chronic and complex conditions and is particularly influential in health services research in developing countries.[31] Importantly, recent developments also highlight the need to integrate environmental sustainability into these frameworks, suggesting its inclusion as a guiding principle to enhance the environmental responsiveness of health systems.[32]

An increasing number of tools and guidelines are being published by international agencies and development partners to assist health system decision-makers to monitor and assess health systems strengthening[33] including human resources development[34] using standard definitions, indicators and measures. In response to a series of papers published in 2012 by members of the World Health Organization's Task Force on Developing Health Systems Guidance, researchers from the Future Health Systems consortium argue that there is insufficient focus on the 'policy implementation gap'. Recognizing the diversity of stakeholders and complexity of health systems is crucial to ensure that evidence-based guidelines are tested with requisite humility and without a rigid adherence to models dominated by a limited number of disciplines.[29][35] Healthcare services often implement Quality Improvement Initiatives to overcome this policy implementation gap. Although many of these initiatives deliver improved healthcare, a large proportion fail to be sustained. Numerous tools and frameworks have been created to respond to this challenge and increase improvement longevity. One tool highlighted the need for these tools to respond to user preferences and settings to optimize impact.[36]

Health Policy and Systems Research (HPSR) is an emerging multidisciplinary field that challenges 'disciplinary capture' by dominant health research traditions, arguing that these traditions generate premature and inappropriately narrow definitions that impede rather than enhance health systems strengthening.[37] HPSR focuses on low- and middle-income countries and draws on the relativist social science paradigm which recognises that all phenomena are constructed through human behaviour and interpretation. In using this approach, HPSR offers insight into health systems by generating a complex understanding of context in order to enhance health policy learning.[38] HPSR calls for greater involvement of local actors, including policy makers, civil society and researchers, in decisions that are made around funding health policy research and health systems strengthening.[39]

Spending

[edit]Expand the OECD charts below to see the breakdown:

- "Government/compulsory": Government spending and compulsory health insurance.

- "Voluntary": Voluntary health insurance and private funds such as households' out-of-pocket payments, NGOs and private corporations.

- They are represented by columns starting at zero. They are not stacked. The 2 are combined to get the total.

- At the source you can run your cursor over the columns to get the year and the total for that country.[42]

- Click the table tab at the source to get 3 lists (one after another) of amounts by country: "Total", "Government/compulsory", and "Voluntary".[42]

International comparisons

[edit]

Health systems can vary substantially from country to country, and in the last few years, comparisons have been made on an international basis. The World Health Organization, in its World Health Report 2000, provided a ranking of health systems around the world according to criteria of the overall level and distribution of health in the populations, and the responsiveness and fair financing of health care services.[4] The goals for health systems, according to the WHO's World Health Report 2000 – Health systems: improving performance (WHO, 2000),[43] are good health, responsiveness to the expectations of the population, and fair financial contribution. There have been several debates around the results of this WHO exercise,[44] and especially based on the country ranking linked to it,[45] insofar as it appeared to depend mostly on the choice of the retained indicators.

Direct comparisons of health statistics across nations are complex. The Commonwealth Fund, in its annual survey, "Mirror, Mirror on the Wall", compares the performance of the health systems in Australia, New Zealand, the United Kingdom, Germany, Canada and the United States. Its 2007 study found that, although the United States system is the most expensive, it consistently underperforms compared to the other countries.[46] A major difference between the United States and the other countries in the study is that the United States is the only country without universal health care. The OECD also collects comparative statistics, and has published brief country profiles.[47][48][49] Health Consumer Powerhouse makes comparisons between both national health care systems in the Euro health consumer index and specific areas of health care such as diabetes[50] or hepatitis.[51]

Ipsos MORI produces an annual study of public perceptions of healthcare services across 30 countries.[52]

| Country | Life expectancy[53] | Infant mortality rate[54] | Preventable deaths per 100,000 people in 2007[55] | Physicians per 1000 people | Nurses per 1000 people | Per capita expenditure on health (USD PPP) | Healthcare costs as a percent of GDP | % of government revenue spent on health | % of health costs paid by government |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Australia | 83.0 | 4.49 | 57 | 2.8 | 10.1 | 3,353 | 8.5 | 17.7 | 67.5 |

| Canada | 82.0 | 4.78 | 77[56] | 2.2 | 9.0 | 3,844 | 10.0 | 16.7 | 70.2 |

| Finland | 79.5 | 2.6 | 2.7 | 15.5 | 3,008 | 8.4 | |||

| France | 82.0 | 3.34 | 55 | 3.3 | 7.7 | 3,679 | 11.6 | 14.2 | 78.3 |

| Germany | 81.0 | 3.48 | 76 | 3.5 | 10.5 | 3,724 | 10.4 | 17.6 | 76.4 |

| Italy | 83.0 | 3.33 | 60 | 4.2 | 6.1 | 2,771 | 8.7 | 14.1 | 76.6 |

| Japan | 84.0 | 2.17 | 61 | 2.1 | 9.4 | 2,750 | 8.2 | 16.8 | 80.4 |

| Norway | 83.0 | 3.47 | 64 | 3.8 | 16.2 | 4,885 | 8.9 | 17.9 | 84.1 |

| Spain | 83.0 | 3.30 | 74 | 3.8 | 5.3 | 3,248 | 8.9 | 15.1 | 73.6 |

| Sweden | 82.0 | 2.73 | 61 | 3.6 | 10.8 | 3,432 | 8.9 | 13.6 | 81.4 |

| UK | 81.6 | 4.5 | 83 | 2.5 | 9.5 | 3,051 | 8.4 | 15.8 | 81.3 |

| US | 78.74 | 5.9 | 96 | 2.4 | 10.6 | 7,437 | 16.0 | 18.5 | 45.1 |

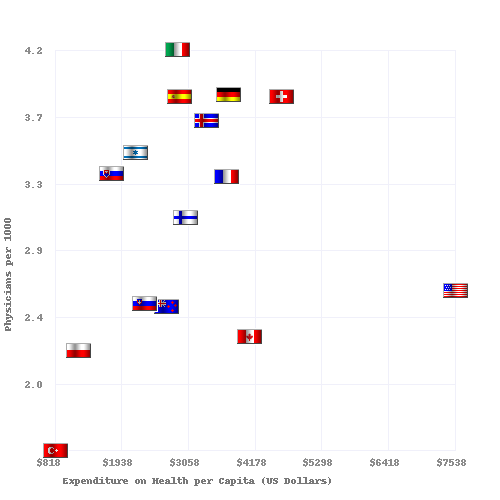

Physicians and hospital beds per 1000 inhabitants vs Health Care Spending in 2008 for OECD Countries. The data source is OECD.org - OECD.[48][49] Since 2008, the US experienced big deviations from 16% GDP. In 2010, the year the Affordable Care Act was enacted, health care spending accounted for approximately 17.2% of the U.S. GDP. By 2019, before the pandemic, it had risen to 17.7%. During the COVID-19 pandemic, this percentage jumped to 18.8% in 2020, largely due to increased health care costs and economic contraction. Post-pandemic, health care spending relative to GDP declined to 16.6% by 2022.[57][58]

See also

[edit]- Acronyms in healthcare

- Catholic Church and health care

- Clinical Health Promotion

- Community health

- Comparison of the health care systems in Canada and the United States

- Consumer-driven health care

- Cultural competence in health care

- Global health

- Genetic testing

- List of countries by health insurance coverage

- Health administration

- Health care

- Health care provider

- Health care reform

- Health crisis

- Health equity

- Health human resources

- Health insurance

- Health policy

- Health promotion

- Health services research

- Healthy city

- Hospital network

- Medicine

- National health insurance

- Occupational safety and health

- Philosophy of healthcare

- Primary care

- Primary health care

- Public health

- Publicly funded health care

- Single-payer health care

- Social determinants of health

- Socialized medicine

- Timeline of global health

- Two-tier health care

- Universal health care

References

[edit]- ^ White F (2015). "Primary health care and public health: foundations of universal health systems". Med Princ Pract. 24 (2): 103–116. doi:10.1159/000370197. PMC 5588212. PMID 25591411.

- ^ a b "Health care system". Liverpool-ha.org.uk. Archived from the original on 25 January 2021. Retrieved 6 August 2011.

- ^ New Yorker magazine article: "Getting there from here." Archived 28 May 2014 at the Wayback Machine 26 January 2009

- ^ a b World Health Organization. (2000). World Health Report 2000 – Health systems: improving performance. Geneva, WHO [1]

- ^ Remarks by Johns Hopkins University President William Brody: "Health Care '08: What's Promised/What's Possible?" Archived 11 February 2009 at the Wayback Machine 7 September 2007

- ^ Cook, R. I.; Render, M.; Woods, D. (2000). "Gaps in the continuity of care and progress on patient safety". BMJ. 320 (7237): 791–794. doi:10.1136/bmj.320.7237.791. PMC 1117777. PMID 10720370.

- ^ a b Frenk J (2010). "The global health system: strengthening national health systems as the next step for global progress". PLOS Med. 7 (1) e1000089. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.1000089. PMC 2797599. PMID 20069038.

- ^ "Everybody's business. Strengthening health systems to improve health outcomes: WHO's framework for action" (PDF). WHO. 2007. Archived (PDF) from the original on 28 December 2021. Retrieved 4 October 2020.

- ^ "Regional Overview of Social Health Insurance in South-East Asia Archived 24 February 2007 at the Wayback Machine, World Health Organization. And [2] Archived 3 September 2012 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved 18 August 2006.

- ^ Glied, Sherry A. "Health Care Financing, Efficiency, and Equity." Archived 24 February 2012 at the Wayback Machine National Bureau of Economic Research, March 2008. Accessed 20 March 2008.

- ^ Bengali, Shawn M (13 April 2021). "A COMPARISON OF HOSPITAL CAPACITIES BETWEEN SINGLE-PAYER AND MULTIPAYER HEALTHCARE SYSTEMS AMONG OECD NATIONS" (PDF). Washington, D.C. Retrieved 5 July 2024.

- ^ How Private Insurance Works: A Primer Archived 21 December 2008 at the Wayback Machine by Gary Claxton, Institution for Health Care Research and Policy, Georgetown University, on behalf of the Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation

- ^ Bloom, G; et al. (2008). "Markets, Information Asymmetry And Health Care: Towards New Social Contracts". Social Science and Medicine. 66 (10): 2076–2087. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2008.01.034. PMID 18316147. Archived from the original on 27 April 2021. Retrieved 26 May 2012.

- ^ UNITAID. Republic of Guinea Introduces Air Solidarity Levy to Fight AIDS, TB and Malaria. Archived 12 November 2011 at the Wayback Machine Geneva, 30 June 2011. Accessed 5 July 2011.

- ^ Saltman RB, Von Otter C. Implementing Planned Markets in Health Care: Balancing Social and Economic Responsibility. Buckingham: Open University Press 1995.

- ^ Kolehamainen-Aiken RL (1997). "Decentralization and human resources: implications and impact". Human Resources for Health Development. 2 (1): 1–14.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Elizabeth Docteur; Howard Oxley (2003). "Health-Care Systems: Lessons from the Reform Experience" (PDF). OECD. Archived (PDF) from the original on 22 December 2015. Retrieved 22 January 2009.

- ^ "What is Value-Based Care and How to Make the Transition - Measures Manager". Archived from the original on 13 May 2019. Retrieved 13 May 2019.

- ^ "Records Management Code of Practice". NHS England. 2023. Retrieved 29 June 2023.

- ^ Lucas, H (2008). "Information And Communications Technology For Future Health Systems In Developing Countries". Social Science and Medicine. 66 (10): 2122–2132. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2008.01.033. PMID 18343005. Archived from the original on 27 April 2021. Retrieved 26 May 2012.

- ^ "European Union Public Health Information System – HIV/Aides page". Euphix.org. Archived from the original on 26 July 2011. Retrieved 6 August 2011.

- ^ "European Union Public Health Information System – Diabetes page". Euphix.org. Archived from the original on 26 July 2011. Retrieved 6 August 2011.

- ^ "European Union Public Health Information System – Smoking Behaviors page". Euphix.org. Archived from the original on 1 August 2011. Retrieved 6 August 2011.

- ^ "World Health Day 2011". www.who.int. World Health Organisation. Retrieved 25 October 2025.

- ^ Link between health spending and life expectancy: US is an outlier Archived 11 March 2022 at the Wayback Machine. May 26, 2017. By Max Roser at Our World in Data. Click the sources tab under the chart for info on the countries, healthcare expenditures, and data sources. See the later version of the chart here Archived 5 March 2022 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ Handler A, Issel M, Turnock B. A conceptual framework to measure performance of the public health system. American Journal of Public Health, 2001, 91(8): 1235–39.

- ^ Wilson, Tim; Plsek, Paul E. (29 September 2001). "Complexity, leadership, and management in healthcare organisations". BMJ. 323 (7315): 746–749. doi:10.1136/bmj.323.7315.746. ISSN 0959-8138. PMC 1121291. PMID 11576986.

- ^ Paina, Ligia; David Peters (5 August 2011). "Understanding pathways for scaling up health services through the lens of complex adaptive systems". Health Policy and Planning. 26 (5): 365–373. doi:10.1093/heapol/czr054. PMID 21821667. Archived from the original on 30 May 2013. Retrieved 18 May 2012.

- ^ a b Peters, David; Sara Bennet (2012). "Better Guidance Is Welcome, but without Blinders". PLOS Med. 9 (3) e1001188. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.1001188. PMC 3308928. PMID 22448148.

- ^ Organization, World Health (2010). Monitoring the building blocks of health systems: a handbook of indicators and their measurement strategies. World Health Organization. ISBN 978-92-4-156405-2. Archived from the original on 3 May 2024. Retrieved 15 May 2024.

- ^ Kruk, Margaret E.; Gage, Anna D.; Arsenault, Catherine; Jordan, Keely; Leslie, Hannah H.; Roder-DeWan, Sanam; Adeyi, Olusoji; Barker, Pierre; Daelmans, Bernadette; Doubova, Svetlana V.; English, Mike; García-Elorrio, Ezequiel; Guanais, Frederico; Gureje, Oye; Hirschhorn, Lisa R. (2018). "High-quality health systems in the Sustainable Development Goals era: time for a revolution". The Lancet. Global Health. 6 (11): e1196 – e1252. doi:10.1016/S2214-109X(18)30386-3. ISSN 2214-109X. PMC 7734391. PMID 30196093.

- ^ Padget, Michael; Peters, Michael A.; Brunn, Matthias; Kringos, Dionne; Kruk, Margaret E. (30 April 2024). "Health systems and environmental sustainability: updating frameworks for a new era". BMJ. 385 e076957. doi:10.1136/bmj-2023-076957. ISSN 1756-1833. PMID 38688557. Archived from the original on 3 May 2024. Retrieved 15 May 2024.

- ^ World Health Organization. Monitoring the building blocks of health systems: a handbook of indicators and their measurement strategies. Geneva, WHO Press, 2010.

- ^ Dal Poz MR et al. Handbook on monitoring and evaluation of human resources for health. Geneva, WHO Press, 2009

- ^ Hyder, A; et al. (2007). "Exploring health systems research and its influence on policy processes in low income countries". BMC Public Health. 7 309. doi:10.1186/1471-2458-7-309. PMC 2213669. PMID 17974000.

- ^ Lennox, Laura; Doyle, Cathal; Reed, Julie E.; Bell, Derek (1 September 2017). "What makes a sustainability tool valuable, practical and useful in real-world healthcare practice? A mixed-methods study on the development of the Long Term Success Tool in Northwest London". BMJ Open. 7 (9) e014417. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2016-014417. ISSN 2044-6055. PMC 5623390. PMID 28947436.

- ^ Sheikh, Kabir; Lucy Gilson; Irene Akua Agyepong; Kara Hanson; Freddie Ssengooba; Sara Bennett (2011). "Building the Field of Health Policy and Systems Research: Framing the Questions". PLOS Medicine. 8 (8) e1001073. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.1001073. PMC 3156683. PMID 21857809.

- ^ Gilson, Lucy; Kara Hanson; Kabir Sheikh; Irene Akua Agyepong; Freddie Ssengooba; Sara Bennet (2011). "Building the Field of Health Policy and Systems Research: Social Science Matters". PLOS Medicine. 8 (8) e1001079. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.1001079. PMC 3160340. PMID 21886488.

- ^ Bennet, Sara; Irene Akua Agyepong; Kabir Sheikh; Kara Hanson; Freddie Ssengooba; Lucy Gilson (2011). "Building the Field of Health Policy and Systems Research: An Agenda for Action". PLOS Medicine. 8 (8) e1001081. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.1001081. PMC 3168867. PMID 21918641.

- ^ "OECD.StatExtracts, Health, Non-Medical Determinants of Health, Body weight, Overweight or obese population, self-reported and measured, Total population" (Online Statistics). stats.oecd.org. OECD's iLibrary. 2013. Archived from the original on 2 April 2019. Retrieved 24 April 2014.

- ^ "OECD.StatExtracts, Health, Non-Medical Determinants of Health, Body weight, Obese population, self-reported and measured, Total population" (Online Statistics). stats.oecd.org. OECD's iLibrary. 2013. Archived from the original on 2 April 2019. Retrieved 24 April 2014.

- ^ a b c d OECD Data. Health resources - Health spending Archived 12 April 2020 at the Wayback Machine. doi:10.1787/8643de7e-en. 2 bar charts: For both: From bottom menus: Countries menu > choose OECD. Check box for "latest data available". Perspectives menu > Check box to "compare variables". Then check the boxes for government/compulsory, voluntary, and total. Click top tab for chart (bar chart). For GDP chart choose "% of GDP" from bottom menu. For per capita chart choose "US dollars/per capita". Click fullscreen button above chart. Click "print screen" key. Click top tab for table, to see data.

- ^ World Health Organization. (2000) World Health Report 2000 – Health systems: improving performance. Geneva, WHO Press.

- ^ World Health Organization. Health Systems Performance: Overall Framework. Archived 17 June 2012 at the Wayback Machine Accessed 15 March 2011.

- ^ Navarro V (2000). "Assessment of the World Health Report 2000". Lancet. 356 (9241): 1598–601. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(00)03139-1. PMID 11075789. S2CID 18001992.

- ^ "Mirror, Mirror on the Wall: An International Update on the Comparative Performance of American Health Care". The Commonwealth Fund. 15 May 2007. Archived from the original on 29 March 2009. Retrieved 7 March 2009.

- ^ Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. "OECD Health Data 2008: How Does Canada Compare" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 31 May 2013. Retrieved 9 January 2009.

- ^ a b "Updated statistics from a 2009 report". Oecd.org. Archived from the original on 5 March 2010. Retrieved 6 August 2011.

- ^ a b "OECD Health Data 2009 – Frequently Requested Data". Oecd.org. Archived from the original on 24 September 2015. Retrieved 6 August 2011.

- ^ "The Euro Consumer Diabetes Index 2008". Health Consumer Powerhouse. Archived from the original on 22 April 2016. Retrieved 29 April 2013.

- ^ "Euro Hepatitis Care Index 2012". Health Consumer Powerhouse. Archived from the original on 12 April 2016. Retrieved 29 April 2013.

- ^ "Mental health replaces Covid as the top health concern among Americans". ITIJ. 5 October 2022. Archived from the original on 14 October 2022. Retrieved 14 October 2022.

- ^ "Life expectancy at birth, total (years) | Data". data.worldbank.org. Archived from the original on 2 February 2021. Retrieved 3 August 2018.

- ^ CIA – The World Factbook: Infant Mortality Rate. Archived from the original on 18 December 2012 (Older data). Retrieved 15 May 2013.

- ^ "Mortality amenable to health care" Nolte, Ellen (2011). "Variations in Amenable Mortality—Trends in 16 High-Income Nations". Health Policy (Amsterdam, Netherlands). 103 (1). Commonwealth Fund: 47–52. doi:10.1016/j.healthpol.2011.08.002. PMID 21917350. Archived from the original on 5 February 2012. Retrieved 10 February 2012.

- ^ data for 2003

Nolte, Ellen (2008). "Measuring the Health of Nations: Updating an Earlier Analysis". Health Affairs. 27 (1). Commonwealth Fund: 58–71. doi:10.1377/hlthaff.27.1.58. PMID 18180480. Archived from the original on 11 January 2012. Retrieved 8 January 2012. - ^ Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS), National Health Expenditure Data

- ^ Peterson-KFF Health System Tracker, U.S. Health Spending Overview

External links

[edit]- World Health Organization: Health Systems

- HRC/Eldis Health Systems Resource Guide Archived 2 August 2005 at the Wayback Machine research and other resources on health systems in developing countries

- OECD: Health policies, a list of latest publications by OECD

Health system

View on GrokipediaDefinitions and Core Concepts

Definitions Across Frameworks

The World Health Organization (WHO) provides a foundational definition of a health system as comprising all organizations, people, and actions whose primary intent is to promote, restore, or maintain health, extending beyond clinical care to include financing, stewardship, resource generation, and service delivery. This framework, articulated in the 2000 World Health Report, emphasizes systemic functions like responsiveness to population needs and equity in access, though critics argue its breadth can obscure accountability for core medical outcomes by incorporating non-health determinants such as sanitation and nutrition.[6] Empirical analyses, such as those reviewing health system performance, highlight that this definition facilitates cross-country comparisons but may underemphasize causal links between inputs like spending and verifiable health metrics, such as life expectancy gains.[2] In economic frameworks, health systems are defined more narrowly as integrated arrangements of resources, financing mechanisms, organizational structures, and management processes that culminate in the provision of health services to defined populations.[7] The National Bureau of Economic Research, for example, conceptualizes a health system as a network of affiliated entities—including hospitals, physician groups, and insurers—bound by shared ownership, contracts, or governance to optimize resource allocation and efficiency.[8] This perspective prioritizes measurable outcomes like cost-effectiveness and productivity, as evidenced by studies showing that systems with integrated financing reduce administrative overhead by up to 20% in high-income settings, though real-world data reveal persistent inefficiencies where spending correlates weakly with health improvements.[9] Such definitions underscore causal realism in evaluating systems through econometric models, contrasting with broader views by focusing on incentives and market dynamics rather than universal coverage ideals. Sociological frameworks approach health systems as dynamic social institutions embedded in cultural, structural, and power relations, where definitions incorporate the role of norms, deviance management, and inequality reproduction.[10] Functionalist theory, originating from Talcott Parsons' work in the mid-20th century, posits health systems as mechanisms for societal equilibrium, enabling individuals to resume roles via regulated "sick roles" while maintaining workforce productivity—supported by data indicating that effective systems correlate with lower absenteeism rates, such as a 1-2% GDP boost in nations with robust occupational health integration.[11] Conflict-oriented views, however, define systems as arenas of class or power struggles, where access disparities reflect broader inequities; for instance, analyses of U.S. data from 2020-2023 show racial gaps in preventive care utilization persisting despite expanded coverage, attributing this to institutional biases rather than individual choices.[12] These frameworks reveal limitations in purely functional definitions by integrating empirical evidence of social determinants, such as how income inequality explains 30-50% of variance in health outcomes across OECD countries.[13] Governance-centric definitions, often used in policy analysis, frame health systems as the ensemble of processes, institutions, and rules steering resource allocation and accountability, with stewardship as a core function to align incentives amid principal-agent problems.[14] Drawing from institutional economics, this view—evident in frameworks assessing oversight in low-resource settings—emphasizes verifiable metrics like corruption indices or regulatory compliance, where strong governance correlates with 15-25% better resource utilization, as per World Bank evaluations from 2015-2022.[15] Across these frameworks, common elements include inputs (e.g., personnel, beds per 1,000 population) and outputs (e.g., disease-specific mortality rates), yet divergences persist: WHO's holistic approach favors equity metrics, while economic models stress efficiency ratios, and sociological lenses highlight distributive justice, informing hybrid analyses for causal policy inference.[16]Fundamental Goals from First Principles

The primary objective of a health system, derived from the causal necessities of human biology, is to extend lifespan by countering threats to survival such as infectious diseases, injuries, and chronic conditions through targeted interventions. For instance, widespread vaccination programs have reduced global under-5 mortality from approximately 93 deaths per 1,000 live births in 1990 to 37 in 2023, demonstrating the direct impact of preventive measures on population-level survival. Similarly, advancements in surgical and pharmaceutical treatments have lowered maternal mortality ratios from 385 deaths per 100,000 live births in 1990 to 223 in 2020, underscoring the role of curative care in preserving life. These outcomes prioritize empirical efficacy over equitable distribution alone, as resources are finite and causal effectiveness determines net lives saved. A complementary goal is to alleviate suffering and restore functional capacity, addressing not just mortality but the quality of lived experience. This involves managing pain, disability, and mental health impairments, as untreated conditions impose non-fatal burdens equivalent to years of healthy life lost—estimated globally at 2.5 billion DALYs from non-communicable diseases in 2019 alone. Metrics like disability-adjusted life years (DALYs), which combine premature mortality and morbidity into a single measure, provide a rigorous framework for evaluating interventions' causal contributions to human flourishing, as developed through epidemiological modeling by the Global Burden of Disease Study. Effective systems thus focus on high-impact actions, such as antimicrobial therapies that have reduced post-surgical infection rates by up to 50% in controlled settings, enabling recovery and productivity. Efficiency in resource allocation supports these ends by ensuring interventions yield maximal health returns, avoiding dilution from low-evidence practices. From a first-principles perspective, health systems must discriminate based on verifiable causal chains—favoring treatments with randomized controlled trial evidence over unproven alternatives—rather than uniform access mandates that ignore varying individual risks and responses. Historical data affirm this: countries emphasizing evidence-based prioritization, like those achieving polio eradication via focused immunization campaigns (reducing cases by 99% since 1988), outperform systems burdened by inefficiency. While frameworks like the WHO's emphasize health improvement alongside responsiveness and financial protection, the intrinsic priority remains outcome maximization, as instrumental goals serve only to enable biological imperatives of survival and function.Historical Evolution

Pre-20th Century Systems

In ancient Egypt, medical care was organized around professional healers known as swnw, who applied empirical knowledge of anatomy, surgery, and pharmacology derived from mummification practices and textual records like the Ebers Papyrus (c. 1550 BCE), with treatment often provided in temple complexes serving both elites and commoners through a mix of ritual and practical interventions.[17] In classical Greece (c. 5th–4th centuries BCE), health systems centered on Asclepeia sanctuaries dedicated to Asclepius, where patients underwent incubation rituals, dietary regimens, and early forms of hydrotherapy, financed by votive offerings and state support, marking a shift toward rational observation over pure mysticism as exemplified by Hippocratic principles emphasizing natural causes of disease.[18] The Roman Empire (c. 1st century BCE–5th century CE) advanced organized public health infrastructure, including aqueducts, sewers, and public baths to prevent epidemics, alongside military valetudinaria—dedicated hospitals for legionaries providing surgical care and herbal remedies—while civilian care relied on private physicians and charity for the poor, with urban iactores offering rudimentary outpatient services.[19][20] During the medieval Islamic world (8th–13th centuries CE), bimaristans emerged as state-endowed institutions in cities like Baghdad and Damascus, offering free, comprehensive care including surgery, pharmacy, and mental health treatment to all patients regardless of faith or ability to pay, staffed by salaried physicians and supported by waqf endowments, which pioneered specialized wards and medical education integrated with practice.[21] In contrast, medieval European systems (c. 5th–15th centuries) were predominantly church-operated, with monastic infirmaries providing custodial care for the indigent and pilgrims, leper asylums for isolation, and early hospices like the Hôtel-Dieu in Paris (founded c. 651 CE) relying on alms and ecclesiastical tithes, though medical intervention remained limited by humoral theory and infrequent professional guilds until the 12th-century Salerno school revived Greek texts.[22] By the 18th and 19th centuries in Europe and North America, voluntary hospitals proliferated as charitable institutions funded by subscriptions, philanthropy, and bequests—such as Pennsylvania Hospital (1751) and New York Hospital (1773)—offering inpatient care primarily to the "deserving poor" screened by almoners to exclude the idle, while out-of-pocket payments dominated for the middle class and self-treatment via apothecaries prevailed among laborers.[23] In England, the Poor Law Amendment Act of 1834 centralized relief in workhouses with attached infirmaries, mandating medical attendance for paupers but prioritizing deterrence over comprehensive care, resulting in austere conditions that treated illness amid labor discipline, with about 20% of hospital beds under Poor Law control by the 1890s.[24][25] These systems reflected causal priorities of contagion control and moral welfare, with limited state involvement beyond military valetudinaria or plague quarantines, until industrialization spurred demands for reformed provision amid rising urban morbidity.[26]20th Century Foundations and Models

In the early 20th century, public health systems worldwide expanded through state-led interventions emphasizing sanitation, vaccination, and disease surveillance, building on bacteriological discoveries of the late 19th century. Local and national health departments grew in scope, shifting from reactive quarantine measures to proactive tracking of disease trends and vital statistics standardization, which enabled better resource allocation and mortality reductions. For instance, clean water technologies like filtration and chlorination in U.S. cities contributed to significant infant mortality declines by the 1930s. These foundations prioritized infectious disease control over comprehensive curative care, with limited insurance mechanisms outside voluntary mutual aid societies.[23][27][28] The Bismarck model, originating in Germany's 1883 Health Insurance Act under Chancellor Otto von Bismarck, provided a template for social health insurance that proliferated across Europe in the 20th century. This system mandated contributions from workers and employers to nonprofit sickness funds, covering about 10% of the population initially and expanding to nearly universal coverage by the 1920s through occupational funds managing benefits and provider payments. It emphasized decentralized administration while ensuring broad access to ambulatory and hospital care, influencing adaptations in countries like France (with its 1898 mutualist expansions) and Japan (1922 health insurance law). Proponents viewed it as a pragmatic response to industrial worker needs, though funds' fragmentation led to administrative inefficiencies critiqued in later analyses.[29][30]31280-1/fulltext) In contrast, the Soviet Union's Semashko model, established in the 1920s under People's Commissar Nikolai Semashko, centralized healthcare under state ownership with funding from the national budget, offering free services at the point of use through polyclinics and hospitals. By 1924, it integrated preventive and curative care in a hierarchical structure, achieving high physician density (one per 1,000 citizens by the 1930s) but prioritizing urban and industrial areas, which exacerbated rural disparities and resource misallocation amid political purges. This state-monopoly approach aimed at egalitarian access but relied on ideological conformity over market signals, resulting in inefficiencies like medicine shortages documented in post-Soviet evaluations.[31]32339-5/abstract) The Beveridge model emerged mid-century from the 1942 Beveridge Report in the UK, which advocated a unified national health service to address wartime deprivations and the "five giants" of want, disease, ignorance, squalor, and idleness. Implemented as the National Health Service in 1948, it featured tax-financed, government-provided care with salaried providers and centralized planning, covering 100% of the population and emphasizing universal access without user fees for core services. This taxpayer-funded prototype influenced single-payer systems elsewhere, such as Sweden's expansions in the 1950s, though it faced challenges like waiting lists and rationing, as evidenced by early NHS expenditure data showing costs exceeding initial projections by 50% within a decade.[32][33] In the United States, health systems developed through private voluntary insurance rather than state mandates, with Blue Cross plans launching in 1929 as hospital prepayment arrangements for teachers in Texas, expanding to 26 million enrollees by 1940 amid the Great Depression. Employer-sponsored coverage surged during World War II due to wage freezes, stabilizing it as 90% of insured workers' primary source by 1950, while federal roles remained limited to public health programs like the 1946 Hill-Burton Act funding 500,000 hospital beds. This market-driven path avoided universal coverage, leaving 20-30% uninsured in the mid-century and fostering cost escalations tied to fee-for-service reimbursements.[34][35][36]Late 20th to Early 21st Century Shifts

During the late 20th century, health systems in developed nations faced escalating costs driven by technological adoption, demographic aging, and expanded service utilization, with U.S. health expenditures rising from $74.1 billion in 1970 to $1.4 trillion by 2000 in nominal terms.[37] This pressure prompted widespread cost-containment strategies, particularly the expansion of managed care in the United States, where health maintenance organization (HMO) enrollment surged from 36.5 million in 1990 to 58.2 million by 1995, temporarily slowing premium growth through capitation and utilization review.[38] Globally, similar efforts included payment reforms like diagnosis-related groups in Europe and Japan, aiming to curb fee-for-service incentives, though these often prioritized short-term fiscal restraint over long-term efficiency.[39] The managed care model encountered significant backlash by the mid-1990s for perceived restrictions on patient-provider relationships and care quality, leading to regulatory "patients' bill of rights" legislation in several U.S. states and a pivot toward preferred provider organizations (PPOs) with broader networks.[38] In Europe, national systems like the UK's National Health Service underwent market-oriented reforms, such as the 1990 internal market introducing purchaser-provider splits to enhance competition and efficiency, though evaluations showed mixed results in reducing wait times without proportional cost savings.[40] These shifts reflected a broader tension between market mechanisms and public entitlements, with out-of-pocket costs declining as a share of total spending—from over 50% in the 1960s to under 20% by 2000 in the U.S.—while third-party payers (public and private) dominated financing.[41] The HIV/AIDS epidemic profoundly reshaped public health infrastructure from the 1980s onward, with U.S. incidence peaking at approximately 78,000 cases in 1992 before declining sharply after highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART) introduction in 1996, reducing mortality by over 50% within two years.[42] This crisis accelerated surveillance systems, contact tracing, and community-based care models, influencing responses to subsequent threats like SARS in 2003, while exposing systemic gaps in stigma management and access for marginalized groups; globally, it spurred international funding mechanisms like the Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria in 2002.[43] Concurrently, the rise of chronic non-communicable diseases, fueled by obesity rates doubling in OECD countries from 1980 to 2010, shifted systems toward preventive and integrated care, challenging acute-care dominance.[44] Technological integration marked another pivotal change, with the Human Genome Project's draft sequence in 2000 enabling precision medicine foundations and molecular diagnostics for personalized treatments, while electronic health records proliferated in the 2000s, improving data interoperability despite adoption barriers in fragmented systems.[45] Evidence-based practice gained traction through guidelines from bodies like the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force, established in 1984 but influential by the 1990s, emphasizing randomized trials over anecdotal care to optimize resource allocation.[46] These advancements, however, amplified cost pressures, as procedures like MRI scans—first routine in the 1980s—drove imaging expenditures up tenfold by 2000, underscoring causal links between innovation and fiscal strain without corresponding productivity gains in all systems.[47]Typology of Health Systems

Beveridge Model (Government Ownership)

The Beveridge model, named after British economist William Beveridge, features direct government ownership and provision of healthcare services, primarily funded through general taxation.[48] This system emerged from Beveridge's 1942 report, which proposed a comprehensive welfare state including universal health coverage, leading to the establishment of the United Kingdom's National Health Service (NHS) in 1948.[49] Under this model, the state employs healthcare providers, owns facilities, and delivers care free at the point of use to all citizens, emphasizing equity and universality over market mechanisms.[50] Key characteristics include centralized planning, with funding derived from progressive income taxes rather than insurance premiums or out-of-pocket payments, minimizing financial barriers to access.[51] Governments set budgets, allocate resources, and regulate services, often resulting in standardized care protocols but potential rationing through wait times for non-emergency procedures.[52] Examples include the UK's NHS, where all residents receive automatic coverage for hospital, physician, and mental health services; Spain's publicly owned regional systems; and Nordic countries like Sweden and Norway, which integrate similar state-dominated delivery.[50][53] Empirical assessments reveal mixed performance relative to other models. Beveridge systems achieve high equity in access and lower per-capita spending—e.g., the UK spends about 10% of GDP on health versus higher figures in Bismarck-model countries—but often lag in outcomes like amenable mortality and life expectancy.[54] A comparative analysis of Beveridge (NHS-style) versus Bismarck systems found no significant differences in overall health outcomes or patient satisfaction, though Beveridge models exhibit lower expenditures.[55] However, studies indicate Bismarck systems outperform Beveridge on metrics such as life expectancy and overall mortality rates, attributing this to greater provider incentives and efficiency.[56] During economic crises, Beveridge models demonstrate resilience in maintaining access but face challenges with waitlists and resource constraints.[57] Public satisfaction tends to be higher in publicly funded systems like Beveridge due to perceived fairness, though real-world issues like the UK's NHS waiting lists exceeding 7 million patients in 2023 highlight operational strains.[58]Bismarck Model (Social Insurance)

The Bismarck model, also known as the social insurance model, finances health care through mandatory, employment-based contributions shared between employers and employees, administered by non-profit insurance funds rather than direct government taxation or ownership of providers.[48] Originating in Germany with the Health Insurance Act of 1883 under Chancellor Otto von Bismarck, it aimed to provide coverage to industrial workers amid rising social unrest, marking one of the earliest efforts toward universal health protection via decentralized, solidarity-based insurance.[30] This system emphasized risk-pooling across income groups without means-testing, funded by payroll deductions typically split evenly between workers and employers, with contribution rates set as a fixed percentage of income—around 14.6% in Germany as of 2023, capped for higher earners.[59] Key features include multiple competing non-profit sickness funds (e.g., over 100 in Germany) that collect premiums, negotiate provider payments, and reimburse services, promoting choice for enrollees while regulating benefits to ensure comprehensive coverage for essentials like hospital care, physician visits, and pharmaceuticals.[60] Providers operate primarily as private entities or non-profits, with patients enjoying free choice among doctors and hospitals, contrasting with more centralized delivery in tax-funded models; governments oversee solvency, benefit standards, and price controls but do not directly employ most providers.[29] Coverage is near-universal, as participation is compulsory for employees below income thresholds (e.g., €64,350 annually in Germany in 2023), with about 90% of the population in statutory funds and the remainder opting into private insurance for potentially broader benefits.[61] This model operates in countries including Germany, France, Japan, Belgium, the Netherlands, and Switzerland, where it supports high provider density—Germany had 4.5 physicians per 1,000 people in 2022—yet faces challenges like escalating costs from aging populations and administrative fragmentation.[48] [62] Empirical comparisons with the Beveridge model (e.g., UK's National Health Service) reveal no consistent superiority in health outcomes such as life expectancy or infant mortality, which vary more by socioeconomic factors and spending levels than system type; Bismarck systems often achieve efficient access via competition among funds but incur higher administrative overhead (around 5-8% of spending) due to multiple insurers.[55] In Germany, health expenditure reached 12.8% of GDP in 2022, funding robust infrastructure but prompting reforms like diagnosis-related group payments to curb hospital overuse.[63] Despite regulatory harmonization, disparities persist, with private insurees accessing faster elective care, highlighting tensions between equity and efficiency in contribution-based designs.[29]National Health Insurance and Private-Dominated Models

The National Health Insurance (NHI) model establishes a single-payer system in which the government acts as the sole insurer, funding coverage through taxes or mandatory premiums while allowing private providers to deliver services.[48] This structure achieves universal coverage without profit-driven denial of claims, as the insurer operates as a non-profit entity with centralized bargaining power over prices and utilization.[64] Examples include Canada's provincial plans, established under the 1984 Canada Health Act, which prohibit private insurance for core medically necessary services to prevent two-tier care, and Taiwan's National Health Insurance program, implemented in 1995, covering 99.9% of the population via a single public fund.[65] In these systems, administrative costs remain low—Canada's at approximately 2% of total health spending—due to streamlined claims processing without competing insurers.[48] Despite broad access, NHI models often ration care through non-price mechanisms, leading to extended wait times for elective and specialist procedures. In Canada, the median wait from general practitioner referral to treatment reached 30.0 weeks in 2024, up from 25.6 weeks in 2023, with orthopedic surgery averaging 57.5 weeks.[66] Statistics Canada data from 2024 indicate that while 66% of patients waited under three months for initial specialist consultations, provincial variations persist, with Quebec reporting longer emergency department stays exceeding 20 hours for many.[67] Proponents attribute lower per capita costs—Canada's at $6,319 USD (PPP) in 2022—to bulk purchasing, yet critics note suppressed innovation, as evidenced by Canada's reliance on U.S.-developed technologies and pharmaceuticals.[68] Private-dominated models, as in the United States, feature decentralized financing primarily through employer-sponsored private insurance, supplemented by public programs like Medicare for seniors and Medicaid for low-income groups, but lacking a universal mandate prior to partial expansions.[69] Coverage is predominantly private, with 201.1 million Americans insured via employers or direct purchase as of 2015, though the uninsured rate stood at 8.5% in 2020, equating to about 28 million people facing out-of-pocket barriers.[70] This fragmentation drives high administrative overhead—up to 12-18% of spending—due to multiple payers negotiating varied rates, contributing to U.S. health expenditures reaching 17.3% of GDP in 2022, or $12,555 per capita.[71] The private model's emphasis on market incentives fosters rapid innovation, with the U.S. accounting for over 50% of global new drug approvals and leading in medical device advancements, such as minimally invasive surgeries and biologics, largely funded by private R&D investments exceeding $100 billion annually.[68] Private equity and for-profit entities have accelerated operational efficiencies, including ambulatory care centers that reduced procedure costs by 20-30% in competitive markets.[72] However, outcomes reflect trade-offs: insured Americans experience shorter waits—often days for specialists versus months in NHI systems—but face higher costs, with average family premiums at $23,968 in 2023, exacerbating inequities for the uninsured, who incur 62% lower health expenses but delayed care and worse health metrics.[73] Empirical comparisons show mixed quality; private coverage correlates with higher utilization of preventive services yet elevated overall societal costs without proportional life expectancy gains, attributable partly to behavioral factors beyond system design.[74]Out-of-Pocket and Hybrid Systems

Out-of-pocket health systems rely primarily on direct payments by patients to providers for medical services, with minimal or no involvement from government subsidies or insurance mechanisms as the dominant financing source. These systems predominate in many low- and lower-middle-income countries, where out-of-pocket expenditures often exceed 50% of total health spending; for instance, in sub-Saharan African nations, out-of-pocket payments constituted the majority of healthcare financing in 24 out of 49 countries as of 2021.[75] Examples include Cambodia, rural India, and parts of Nigeria and Pakistan, where patients typically pay fees at the point of service to both public and private facilities, supplemented sporadically by charitable aid or informal networks.[1] This model aligns provider incentives with patient demand but exposes households to financial risk, as evidenced by global data showing out-of-pocket spending pushing millions into poverty annually, particularly in regions lacking risk-pooling.[76] Empirical evidence indicates that predominant out-of-pocket financing correlates with reduced healthcare utilization among low-income groups due to cost barriers, leading to delayed treatment and poorer health outcomes compared to insured populations. A systematic review found no positive association between higher out-of-pocket costs and improved inpatient quality or health results, while uninsured individuals exhibit lower rates of preventive care and higher mortality risks from treatable conditions.[77] [78] On the efficiency side, direct payments can curb moral hazard by discouraging overuse of services, fostering price competition among providers and potentially containing overall system costs in resource-constrained settings; however, this benefit is often offset by inefficiencies from fragmented markets and supplier-induced demand.[79] In 2022, low-income countries averaged 43% of health expenditures as out-of-pocket, far exceeding the 19% in high-income nations, underscoring how such systems exacerbate inequities without broad risk protection.[80] Hybrid systems integrate out-of-pocket payments with elements of insurance, social funds, or government support, creating blended financing where direct costs remain substantial but are mitigated by partial coverage for specific populations or services. These arrangements are common in middle-income countries transitioning from pure out-of-pocket dominance, such as India and China, where public insurance schemes cover segments of the population while out-of-pocket expenses still account for 40-60% of total spending.[81] Singapore exemplifies a hybrid approach through mandatory savings accounts (Medisave) combined with subsidized public care and private options, resulting in out-of-pocket shares around 30-40% but with strong outcomes in cost control and access.[82] Similarly, the Netherlands and Switzerland mandate private insurance with regulated premiums and subsidies, blending employer contributions, individual payments, and out-of-pocket deductibles to balance risk-sharing against personal responsibility.[83] In hybrid models, empirical data show moderated financial burdens compared to pure out-of-pocket systems, as partial insurance reduces catastrophic expenditures by 2-2.4% in covered groups, though high deductibles can still deter utilization among the uninsured.[84] These systems often achieve better resource allocation through competition and innovation, as seen in Singapore's life expectancy gains alongside contained per-capita spending, but challenges persist in ensuring equitable coverage amid varying income levels.[85] Overall, hybrids demonstrate that combining direct payments with pooled funding can enhance efficiency without fully sacrificing access, provided regulatory frameworks prevent adverse selection and cream-skimming by insurers.[86]Financing Mechanisms

Primary Revenue Sources

Public funding through general taxation and compulsory social health insurance contributions constitutes the predominant revenue source for health systems in high-income countries, accounting for 73% of total health expenditure across OECD nations in 2021.[87] [88] This public share encompasses government schemes financed by taxes, which averaged 59% of current health spending in OECD countries in 2021, and social health insurance funds derived from mandatory payroll contributions, which added another 14%.[88] In tax-financed systems like the United Kingdom's National Health Service, nearly all revenue derives from progressive general taxation, minimizing direct patient costs while relying on fiscal sustainability amid rising expenditures.[88] Social health insurance, prevalent in Bismarck-model countries such as Germany and France, generates revenue via earmarked contributions typically split between employers and employees at rates of 14-15% of gross wages, pooled into nonprofit funds that reimburse providers.[88] These schemes ensure broad compulsory coverage, with revenues insulated from annual budget cycles but vulnerable to economic downturns affecting employment and wage bases; in 2021, they financed 14% of OECD health spending on average, though shares exceed 50% in nations like Japan and the Netherlands.[88] [87] Private health insurance premiums, collected voluntarily, supplement public systems and fund about 6% of health expenditure in OECD countries, rising to over 25% in the United States where employer-sponsored plans predominate.[88] These premiums, often risk-rated or experience-rated, incentivize cost control through competition but can exacerbate inequities by favoring healthier or higher-income enrollees; revenues totaled approximately USD 500 billion across OECD in recent years, concentrated in hybrid systems.[88] Out-of-pocket payments, including copayments, deductibles, and informal fees, remain a universal but variable source, comprising 20% of OECD health spending in 2021 and up to 40-50% in low- and middle-income countries per WHO data.[88] [81] These direct household expenditures, while providing immediate revenue to providers, correlate with financial hardship and reduced access, particularly for catastrophic costs exceeding 10% of income; globally, they financed USD 1.5 trillion in 2021 estimates, underscoring the need for protective mechanisms like caps in sustainable systems.[81] [89]Payment and Reimbursement Models

Payment and reimbursement models dictate how health care providers receive compensation, directly influencing incentives for service volume, efficiency, and quality. In fee-for-service (FFS) systems, providers are reimbursed for each discrete service or procedure delivered, which empirical analyses link to higher utilization rates and escalating costs, as payments reward quantity over outcomes; for instance, U.S. Medicare data prior to reforms showed FFS contributing to annual spending growth exceeding 5% in certain periods due to fragmented care incentives.[90] [91] Capitation models, conversely, allocate a fixed per-patient payment to providers or organizations regardless of services rendered, fostering preventive care and cost containment but risking undertreatment or patient selection biases; studies of managed care plans indicate capitation reduces expenditures by 10-20% compared to FFS in some cohorts, though with variable impacts on chronic disease management.[92] [93] Bundled payments consolidate reimbursements for an entire episode of care—such as a joint replacement including pre- and post-operative services—shifting risk to providers to coordinate across settings and control total costs. Prospective payment systems (PPS), exemplified by Medicare's diagnosis-related groups (DRGs) implemented in 1983, exemplify this approach for inpatient care, standardizing fixed rates per diagnosis to curb length-of-stay inflation; international evaluations, including in Germany and the Netherlands, report bundled models slowing spending growth by 3-5% per episode without consistent quality declines, though success depends on robust data infrastructure for risk adjustment.[91] [94] Value-based payment (VBP) and pay-for-performance (P4P) mechanisms tie portions of reimbursement—often 5-10% of total fees—to metrics like readmission rates or patient-reported outcomes, aiming to prioritize evidence-based practices. OECD analyses of VBP implementations across member countries find modest efficiency gains, such as reduced low-value care, but limited broad impacts on overall spending or mortality, with challenges including measurement errors and provider gaming of indicators.[95] [96]| Model | Key Features | Incentives | Empirical Outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fee-for-Service | Per-unit billing for services | Volume-driven care | Higher costs (e.g., +10-15% utilization in U.S. studies); neutral or variable quality[90] |

| Capitation | Fixed per-enrollee payment | Efficiency and prevention | Cost savings (10-20% vs. FFS); potential access barriers for high-need patients[92] |

| Bundled/PPS | Fixed rate per episode/diagnosis | Care coordination | Spending reductions (3-5% growth slowdown); stable quality in orthopedic episodes[94] |

| Value-Based/P4P | Performance-linked adjustments | Outcome alignment | Modest quality improvements; inconsistent cost control (e.g., <2% net savings in OECD reviews)[95] |

Service Delivery and Management

Providers, Infrastructure, and Workforce

Healthcare providers include licensed professionals such as physicians, nurses, nurse practitioners, physician assistants, and allied health workers like pharmacists and therapists, who deliver diagnostic, therapeutic, and preventive services across primary, secondary, and tertiary care levels.[100] In various health systems, physicians are divided into generalists for initial care and specialists for complex conditions, with nurse practitioners and physician assistants expanding access in underserved areas by handling routine tasks under varying degrees of supervision.[101] Facilities serving as providers encompass acute hospitals for inpatient treatment, outpatient clinics for ambulatory services, and long-term care institutions for chronic needs, with ownership ranging from public in Beveridge models to private in market-oriented systems.[102] Infrastructure supporting service delivery consists of physical assets like hospital buildings, diagnostic equipment, and supply chains, with capacity often gauged by hospital beds per 1,000 population. In 2021, OECD countries averaged 4.3 beds per 1,000 people, ranging from over 12 in Japan and South Korea to under 3 in the United States and Australia, reflecting differences in admission practices and aging populations rather than spending alone.[103] [104] Investments in infrastructure have increasingly involved private capital to bridge funding gaps, particularly for resilient facilities in developing regions, amid global trends toward modular and sustainable builds.[105] The health workforce, totaling around 65 million globally in 2020 including 12.7 million physicians and 29.1 million nurses, faces projected shortfalls of 11 million workers by 2030, concentrated in low- and middle-income countries due to training lags, migration to high-income nations, and burnout exacerbated by the COVID-19 pandemic.[106] [107] In OECD nations, physician density varied from below 2.5 per 1,000 in Mexico and Turkey to over 5 in Austria and Greece in 2021, with shortages driven by aging demographics increasing demand and geographic maldistribution favoring urban areas.[108] Causes include extended training periods, high attrition from workload and low pay in public systems, and policy failures to align supply with epidemiological shifts like rising chronic diseases.[109] Workforce strategies emphasize task-shifting to non-physicians and international recruitment, though these risk depleting source countries without reciprocal investments.[110]Information Technology and Data Resources

Information technology in health systems encompasses electronic health records (EHRs), telemedicine platforms, health information exchanges (HIEs), and data analytics tools that facilitate patient data management, clinical decision-making, and service coordination.[111] These systems enable real-time access to patient histories, reducing redundant tests and errors, while supporting population health management through aggregated data.[112] Adoption varies by country, with OECD nations showing increased EHR implementation, though full interoperability remains limited.[112] EHR systems, central to modern health IT, have seen global expansion, with the market projected to reach $800 billion by 2033 from $36 billion in 2023, driven by demands for digitized records.[113] In OECD countries, a 2021 survey indicated widespread adoption, but only 15 of 27 respondents had national patient summary systems accessible across providers, highlighting fragmentation that impedes seamless data sharing.[112] For instance, systems like the UK's National Health Service's EHR backbone allow cross-provider access, yet challenges persist in integrating legacy systems from Beveridge-model public providers.[114] Telemedicine, accelerated by the COVID-19 pandemic, expanded virtual care delivery, with U.S. office-based physician use rising from 16% in 2019 to 80.5% in 2021, though utilization later stabilized below peak levels.[115] Post-2020, telemedicine volumes in the U.S. dropped 54.7% from their Q2 2020 high but retained gains in behavioral health and non-primary care specialties, enabling remote monitoring in Bismarck-model insurance networks.[116] Evidence shows no increased need for in-person follow-ups in most specialties, supporting its role in reducing unnecessary visits without compromising outcomes.[117] Data resources, including HIEs and registries, aggregate clinical and administrative data for analytics, aiding predictive modeling and resource allocation.[118] Artificial intelligence applications, such as diagnostic imaging analysis and risk stratification, rely on these datasets, with peer-reviewed evidence demonstrating improved accuracy in pattern detection over traditional methods.[119] However, interoperability barriers—stemming from non-standardized formats, proprietary silos, and regulatory variances—persist, leading to data duplication and delayed care; solutions involve FHIR standards and policy alignment, though implementation lags in fragmented private-dominated systems.[120] Privacy regulations like HIPAA in the U.S. and GDPR in Europe add layers of compliance, balancing data utility against breach risks, with cybersecurity incidents underscoring vulnerabilities in interconnected networks.[121]Performance Assessment

Metrics of Access, Quality, and Health Outcomes