Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Medical image computing

View on WikipediaMedical image computing (MIC) is the use of computational and mathematical methods for solving problems pertaining to medical images and their use for biomedical research and clinical care. It is an interdisciplinary field at the intersection of computer science, information engineering, electrical engineering, physics, mathematics and medicine.

The main goal of MIC is to extract clinically relevant information or knowledge from medical images. While closely related to the field of medical imaging, MIC focuses on the computational analysis of the images, not their acquisition. The methods can be grouped into several broad categories: image segmentation, image registration, image-based physiological modeling, and others.[1]

Data forms

[edit]Medical image computing typically operates on uniformly sampled data with regular x-y-z spatial spacing (images in 2D and volumes in 3D, generically referred to as images). At each sample point, data is commonly represented in integral form such as signed and unsigned short (16-bit), although forms from unsigned char (8-bit) to 32-bit float are not uncommon. The particular meaning of the data at the sample point depends on modality: for example a CT acquisition collects radiodensity values, while an MRI acquisition may collect T1 or T2-weighted images. Longitudinal, time-varying acquisitions may or may not acquire images with regular time steps. Fan-like images due to modalities such as curved-array ultrasound are also common and require different representational and algorithmic techniques to process. Other data forms include sheared images due to gantry tilt during acquisition; and unstructured meshes, such as hexahedral and tetrahedral forms, which are used in advanced biomechanical analysis (e.g., tissue deformation, vascular transport, bone implants).

Segmentation

[edit]

Segmentation is the process of partitioning an image into different meaningful segments. In medical imaging, these segments often correspond to different tissue classes, organs, pathologies, or other biologically relevant structures.[2] Medical image segmentation is made difficult by low contrast, noise, and other imaging ambiguities. Although there are many computer vision techniques for image segmentation, some have been adapted specifically for medical image computing. Below is a sampling of techniques within this field; the implementation relies on the expertise that clinicians can provide.

- Atlas-based segmentation: For many applications, a clinical expert can manually label several images; segmenting unseen images is a matter of extrapolating from these manually labeled training images. Methods of this style are typically referred to as atlas-based segmentation methods. Parametric atlas methods typically combine these training images into a single atlas image,[3] while nonparametric atlas methods typically use all of the training images separately.[4] Atlas-based methods usually require the use of image registration in order to align the atlas image or images to a new, unseen image.

- Shape-based segmentation: Many methods parametrize a template shape for a given structure, often relying on control points along the boundary. The entire shape is then deformed to match a new image. Two of the most common shape-based techniques are active shape models[5] and active appearance models.[6] These methods have been very influential, and have given rise to similar models.[7]

- Image-based segmentation: Some methods initiate a template and refine its shape according to the image data while minimizing integral error measures, like the active contour model and its variations.[8]

- Interactive segmentation: Interactive methods are useful when clinicians can provide some information, such as a seed region or rough outline of the region to segment. An algorithm can then iteratively refine such a segmentation, with or without guidance from the clinician. Manual segmentation, using tools such as a paint brush to explicitly define the tissue class of each pixel, remains the gold standard for many imaging applications. Recently, principles from feedback control theory have been incorporated into segmentation, which give the user much greater flexibility and allow for the automatic correction of errors.[9]

- Subjective surface segmentation: This method is based on the idea of evolution of segmentation function which is governed by an advection-diffusion model.[10] To segment an object, a segmentation seed is needed (that is the starting point that determines the approximate position of the object in the image). Consequently, an initial segmentation function is constructed. The idea behind the subjective surface method [11][12][13] is that the position of the seed is the main factor determining the form of this segmentation function.

- Convolutional neural networks (CNNs): The computer-assisted fully automated segmentation performance has been improved due to the advancement of machine learning models. CNN based models such as SegNet,[14] UNet,[15] ResNet,[16] AATSN,[17] Transformers[18] and GANs[19] have fastened the segmentation process. In the future, such models may replace manual segmentation due to their superior performance and speed.

There are other classifications of image segmentation methods that are similar to categories above. Another group, which is based on combination of methods, can be classified as "hybrid".[20]

Registration

[edit]

Image registration is a process that searches for the correct alignment of images.[21][22][23][24] In the simplest case, two images are aligned. Typically, one image is treated as the target image and the other is treated as a source image; the source image is transformed to match the target image. The optimization procedure updates the transformation of the source image based on a similarity value that evaluates the current quality of the alignment. This iterative procedure is repeated until a (local) optimum is found. An example is the registration of CT and PET images to combine structural and metabolic information (see figure).

Image registration is used in a variety of medical applications:

- Studying temporal changes. Longitudinal studies acquire images over several months or years to study long-term processes, such as disease progression. Time series correspond to images acquired within the same session (seconds or minutes). They can be used to study cognitive processes, heart deformations and respiration.

- Combining complementary information from different imaging modalities. An example is the fusion of anatomical and functional information. Since the size and shape of structures vary across modalities, it is more challenging to evaluate the alignment quality. This has led to the use of similarity measures such as mutual information.[25]

- Characterizing a population of subjects. In contrast to intra-subject registration, a one-to-one mapping may not exist between subjects, depending on the structural variability of the organ of interest. Inter-subject registration is required for atlas construction in computational anatomy.[26] Here, the objective is to statistically model the anatomy of organs across subjects.

- Computer-assisted surgery. In computer-assisted surgery pre-operative images such as CT or MRI are registered to intra-operative images or tracking systems to facilitate image guidance or navigation.

There are several important considerations when performing image registration:

- The transformation model. Common choices are rigid, affine, and deformable transformation models. B-spline and thin plate spline models are commonly used for parameterized transformation fields. Non-parametric or dense deformation fields carry a displacement vector at every grid location; this necessitates additional regularization constraints. A specific class of deformation fields are diffeomorphisms, which are invertible transformations with a smooth inverse.

- The similarity metric. A distance or similarity function is used to quantify the registration quality. This similarity can be calculated either on the original images or on features extracted from the images. Common similarity measures are sum of squared distances (SSD), correlation coefficient, and mutual information. The choice of similarity measure depends on whether the images are from the same modality; the acquisition noise can also play a role in this decision. For example, SSD is the optimal similarity measure for images of the same modality with Gaussian noise.[27] However, the image statistics in ultrasound are significantly different from Gaussian noise, leading to the introduction of ultrasound specific similarity measures.[28] Multi-modal registration requires a more sophisticated similarity measure; alternatively, a different image representation can be used, such as structural representations[29] or registering adjacent anatomy.[30][31] A 2020 study[32] employed contrastive coding to learn shared, dense image representations, referred to as contrastive multi-modal image representations (CoMIRs), which enabled the registration of multi-modal images where existing registration methods often fail due to a lack of sufficiently similar image structures. It reduced the multi-modal registration problem to a mono-modal one, in which general intensity based, as well as feature-based, registration algorithms can be applied.

- The optimization procedure. Either continuous or discrete optimization is performed. For continuous optimization, gradient-based optimization techniques are applied to improve the convergence speed.

Visualization

[edit]

Visualization plays several key roles in medical image computing. Methods from scientific visualization are used to understand and communicate about medical images, which are inherently spatial-temporal. Data visualization and data analysis are used on unstructured data forms, for example when evaluating statistical measures derived during algorithmic processing. Direct interaction with data, a key feature of the visualization process, is used to perform visual queries about data, annotate images, guide segmentation and registration processes, and control the visual representation of data (by controlling lighting rendering properties and viewing parameters). Visualization is used both for initial exploration and for conveying intermediate and final results of analyses.

The figure "Visualization of Medical Imaging" illustrates several types of visualization: 1. the display of cross-sections as gray scale images; 2. reformatted views of gray scale images (the sagittal view in this example has a different orientation than the original direction of the image acquisition; and 3. A 3D volume rendering of the same data. The nodular lesion is clearly visible in the different presentations and has been annotated with a white line.

Atlases

[edit]Medical images can vary significantly across individuals due to people having organs of different shapes and sizes. Therefore, representing medical images to account for this variability is crucial. A popular approach to represent medical images is through the use of one or more atlases. Here, an atlas refers to a specific model for a population of images with parameters that are learned from a training dataset.[33][34]

The simplest example of an atlas is a mean intensity image, commonly referred to as a template. However, an atlas can also include richer information, such as local image statistics and the probability that a particular spatial location has a certain label. New medical images, which are not used during training, can be mapped to an atlas, which has been tailored to the specific application, such as segmentation and group analysis. Mapping an image to an atlas usually involves registering the image and the atlas. This deformation can be used to address variability in medical images.

Single template

[edit]The simplest approach is to model medical images as deformed versions of a single template image. For example, anatomical MRI brain scans are often mapped to the MNI template [35] as to represent all the brain scans in common coordinates. The main drawback of a single-template approach is that if there are significant differences between the template and a given test image, then there may not be a good way to map one onto the other. For example, an anatomical MRI brain scan of a patient with severe brain abnormalities (i.e., a tumor or surgical procedure), may not easily map to the MNI template.

Multiple templates

[edit]Rather than relying on a single template, multiple templates can be used. The idea is to represent an image as a deformed version of one of the templates. For example, there could be one template for a healthy population and one template for a diseased population. However, in many applications, it is not clear how many templates are needed. A simple albeit computationally expensive way to deal with this is to have every image in a training dataset be a template image and thus every new image encountered is compared against every image in the training dataset. A more recent approach automatically finds the number of templates needed.[36]

Statistical analysis

[edit]Statistical methods combine the medical imaging field with modern computer vision, machine learning and pattern recognition. Over the last decade, several large datasets have been made publicly available (see for example ADNI, 1000 functional Connectomes Project), in part due to collaboration between various institutes and research centers. This increase in data size calls for new algorithms that can mine and detect subtle changes in the images to address clinical questions. Such clinical questions are very diverse and include group analysis, imaging biomarkers, disease phenotyping and longitudinal studies.

Group analysis

[edit]In the group analysis, the objective is to detect and quantize abnormalities induced by a disease by comparing the images of two or more cohorts. Usually one of these cohorts consist of normal (control) subjects, and the other one consists of abnormal patients. Variation caused by the disease can manifest itself as abnormal deformation of anatomy (see voxel-based morphometry). For example, shrinkage of sub-cortical tissues such as the hippocampus in brain may be linked to Alzheimer's disease. Additionally, changes in biochemical (functional) activity can be observed using imaging modalities such as positron emission tomography.

The comparison between groups is usually conducted on the voxel level. Hence, the most popular pre-processing pipeline, particularly in neuroimaging, transforms all of the images in a dataset to a common coordinate frame via medical image registration in order to maintain correspondence between voxels. Given this voxel-wise correspondence, the most common frequentist method is to extract a statistic for each voxel (for example, the mean voxel intensity for each group) and perform statistical hypothesis testing to evaluate whether a null hypothesis is or is not supported. The null hypothesis typically assumes that the two cohorts are drawn from the same distribution, and hence, should have the same statistical properties (for example, the mean values of two groups are equal for a particular voxel). Since medical images contain large numbers of voxels, the issue of multiple comparison needs to be addressed,.[37][38] There are also Bayesian approaches to tackle group analysis problem.[39]

Classification

[edit]Although group analysis can quantify the general effects of a pathology on an anatomy and function, it does not provide subject level measures, and hence cannot be used as biomarkers for diagnosis (see Imaging biomarkers). Clinicians, on the other hand, are often interested in early diagnosis of the pathology (i.e. classification,[40][41]) and in learning the progression of a disease (i.e. regression [42]). From methodological point of view, current techniques varies from applying standard machine learning algorithms to medical imaging datasets (e.g. support vector machine[43]), to developing new approaches adapted for the needs of the field.[44] The main difficulties are as follows:

- Small sample size (curse of dimensionality): a large medical imaging dataset contains hundreds to thousands of images, whereas the number of voxels in a typical volumetric image can easily go beyond millions. A remedy to this problem is to reduce the number of features in an informative sense (see dimensionality reduction). Several unsupervised and semi-/supervised,[44][45][46][47] approaches have been proposed to address this issue.

- Interpretability: A good generalization accuracy is not always the primary objective, as clinicians would like to understand which parts of anatomy are affected by the disease. Therefore, interpretability of the results is very important; methods that ignore the image structure are not favored. Alternative methods based on feature selection have been proposed,.[45][46][47][48]

Clustering

[edit]Image-based pattern classification methods typically assume that the neurological effects of a disease are distinct and well defined. This may not always be the case. For a number of medical conditions, the patient populations are highly heterogeneous, and further categorization into sub-conditions has not been established. Additionally, some diseases (e.g., autism spectrum disorder, schizophrenia, mild cognitive impairment can be characterized by a continuous or nearly-continuous spectra from mild cognitive impairment to very pronounced pathological changes. To facilitate image-based analysis of heterogeneous disorders, methodological alternatives to pattern classification have been developed. These techniques borrow ideas from high-dimensional clustering [49] and high-dimensional pattern-regression to cluster a given population into homogeneous sub-populations. The goal is to provide a better quantitative understanding of the disease within each sub-population.

Shape analysis

[edit]Shape analysis is the field of medical image computing that studies geometrical properties of structures obtained from different imaging modalities. Shape analysis recently become of increasing interest to the medical community due to its potential to precisely locate morphological changes between different populations of structures, i.e. healthy vs pathological, female vs male, young vs elderly. Shape analysis includes two main steps: shape correspondence and statistical analysis.

- Shape correspondence is the methodology that computes correspondent locations between geometric shapes represented by triangle meshes, contours, point sets or volumetric images. Obviously definition of correspondence will influence directly the analysis. Among the different options for correspondence frameworks are: anatomical correspondence, manual landmarks, functional correspondence (i.e. in brain morphometry locus responsible for same neuronal functionality), geometry correspondence, (for image volumes) intensity similarity, etc. Some approaches, e.g. spectral shape analysis, do not require correspondence but compare shape descriptors directly.

- Statistical analysis will provide measurements of structural change at correspondent locations.

Longitudinal studies

[edit]In longitudinal studies the same person is imaged repeatedly. This information can be incorporated both into the image analysis, as well as into the statistical modeling.

- In longitudinal image processing, segmentation and analysis methods of individual time points are informed and regularized with common information usually from a within-subject template. This regularization is designed to reduce measurement noise and thus helps increase sensitivity and statistical power. At the same time over-regularization needs to be avoided, so that effect sizes remain stable. Intense regularization, for example, can lead to excellent test-retest reliability, but limits the ability to detect any true changes and differences across groups. Often a trade-off needs to be aimed for, that optimizes noise reduction at the cost of limited effect size loss. Another common challenge in longitudinal image processing is the, often unintentional, introduction of processing bias. When, for example, follow-up images get registered and resampled to the baseline image, interpolation artifacts get introduced to only the follow-up images and not the baseline. These artifact can cause spurious effects (usually a bias towards overestimating longitudinal change and thus underestimating required sample size). It is therefore essential that all-time points get treated exactly the same to avoid any processing bias.

- Post-processing and statistical analysis of longitudinal data usually requires dedicated statistical tools such as repeated measure ANOVA or the more powerful linear mixed effects models. Additionally, it is advantageous to consider the spatial distribution of the signal. For example, cortical thickness measurements will show a correlation within-subject across time and also within a neighborhood on the cortical surface - a fact that can be used to increase statistical power. Furthermore, time-to-event (aka survival) analysis is frequently employed to analyze longitudinal data and determine significant predictors.

Image-based physiological modelling

[edit]Traditionally, medical image computing has seen to address the quantification and fusion of structural or functional information available at the point and time of image acquisition. In this regard, it can be seen as quantitative sensing of the underlying anatomical, physical or physiological processes. However, over the last few years, there has been a growing interest in the predictive assessment of disease or therapy course. Image-based modelling, be it of biomechanical or physiological nature, can therefore extend the possibilities of image computing from a descriptive to a predictive angle.

According to the STEP research roadmap,[50][51] the Virtual Physiological Human (VPH) is a methodological and technological framework that, once established, will enable the investigation of the human body as a single complex system. Underlying the VPH concept, the International Union for Physiological Sciences (IUPS) has been sponsoring the IUPS Physiome Project for more than a decade,.[52][53] This is a worldwide public domain effort to provide a computational framework for understanding human physiology. It aims at developing integrative models at all levels of biological organization, from genes to the whole organisms via gene regulatory networks, protein pathways, integrative cell functions, and tissue and whole organ structure/function relations. Such an approach aims at transforming current practice in medicine and underpins a new era of computational medicine.[54]

In this context, medical imaging and image computing play an increasingly important role as they provide systems and methods to image, quantify and fuse both structural and functional information about the human being in vivo. These two broad research areas include the transformation of generic computational models to represent specific subjects, thus paving the way for personalized computational models.[55] Individualization of generic computational models through imaging can be realized in three complementary directions:

- definition of the subject-specific computational domain (anatomy) and related subdomains (tissue types);

- definition of boundary and initial conditions from (dynamic and/or functional) imaging; and

- characterization of structural and functional tissue properties.

In addition, imaging also plays a pivotal role in the evaluation and validation of such models both in humans and in animal models, and in the translation of models to the clinical setting with both diagnostic and therapeutic applications. In this specific context, molecular, biological, and pre-clinical imaging render additional data and understanding of basic structure and function in molecules, cells, tissues and animal models that may be transferred to human physiology where appropriate.

The applications of image-based VPH/physiome models in basic and clinical domains are vast. Broadly speaking, they promise to become new virtual imaging techniques. Effectively more, often non-observable, parameters will be imaged in silico based on the integration of observable but sometimes sparse and inconsistent multimodal images and physiological measurements. Computational models will serve to engender interpretation of the measurements in a way compliant with the underlying biophysical, biochemical or biological laws of the physiological or pathophysiological processes under investigation. Ultimately, such investigative tools and systems will help our understanding of disease processes, the natural history of disease evolution, and the influence on the course of a disease of pharmacological and/or interventional therapeutic procedures.

Cross-fertilization between imaging and modelling goes beyond interpretation of measurements in a way consistent with physiology. Image-based patient-specific modelling, combined with models of medical devices and pharmacological therapies, opens the way to predictive imaging whereby one will be able to understand, plan and optimize such interventions in silico.

Mathematical methods in medical imaging

[edit]A number of sophisticated mathematical methods have entered medical imaging, and have already been implemented in various software packages. These include approaches based on partial differential equations (PDEs) and curvature driven flows for enhancement, segmentation, and registration. Since they employ PDEs, the methods are amenable to parallelization and implementation on GPGPUs. A number of these techniques have been inspired from ideas in optimal control. Accordingly, very recently ideas from control have recently made their way into interactive methods, especially segmentation. Moreover, because of noise and the need for statistical estimation techniques for more dynamically changing imagery, the Kalman filter[56] and particle filter have come into use. A survey of these methods with an extensive list of references may be found in.[57]

Modality-specific computing

[edit]Some imaging modalities provide very specialized information. The resulting images cannot be treated as regular scalar images and give rise to new sub-areas of medical image computing. Examples include diffusion MRI and functional MRI.

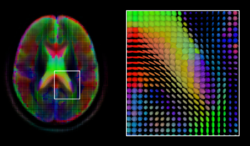

Diffusion MRI

[edit]

Diffusion MRI is a structural magnetic resonance imaging modality that allows measurement of the diffusion process of molecules. Diffusion is measured by applying a gradient pulse to a magnetic field along a particular direction. In a typical acquisition, a set of uniformly distributed gradient directions is used to create a set of diffusion weighted volumes. In addition, an unweighted volume is acquired under the same magnetic field without application of a gradient pulse. As each acquisition is associated with multiple volumes, diffusion MRI has created a variety of unique challenges in medical image computing.

In medicine, there are two major computational goals in diffusion MRI:

- Estimation of local tissue properties, such as diffusivity;

- Estimation of local directions and global pathways of diffusion.

The diffusion tensor,[58] a 3 × 3 symmetric positive-definite matrix, offers a straightforward solution to both of these goals. It is proportional to the covariance matrix of a Normally distributed local diffusion profile and, thus, the dominant eigenvector of this matrix is the principal direction of local diffusion. Due to the simplicity of this model, a maximum likelihood estimate of the diffusion tensor can be found by simply solving a system of linear equations at each location independently. However, as the volume is assumed to contain contiguous tissue fibers, it may be preferable to estimate the volume of diffusion tensors in its entirety by imposing regularity conditions on the underlying field of tensors.[59] Scalar values can be extracted from the diffusion tensor, such as the fractional anisotropy, mean, axial and radial diffusivities, which indirectly measure tissue properties such as the dysmyelination of axonal fibers [60] or the presence of edema.[61] Standard scalar image computing methods, such as registration and segmentation, can be applied directly to volumes of such scalar values. However, to fully exploit the information in the diffusion tensor, these methods have been adapted to account for tensor valued volumes when performing registration [62][63] and segmentation.[64][65]

Given the principal direction of diffusion at each location in the volume, it is possible to estimate the global pathways of diffusion through a process known as tractography.[66] However, due to the relatively low resolution of diffusion MRI, many of these pathways may cross, kiss or fan at a single location. In this situation, the single principal direction of the diffusion tensor is not an appropriate model for the local diffusion distribution. The most common solution to this problem is to estimate multiple directions of local diffusion using more complex models. These include mixtures of diffusion tensors,[67] Q-ball imaging,[68] diffusion spectrum imaging [69] and fiber orientation distribution functions,[70][71] which typically require HARDI acquisition with a large number of gradient directions. As with the diffusion tensor, volumes valued with these complex models require special treatment when applying image computing methods, such as registration[72][73][74] and segmentation.[75]

Functional MRI

[edit]Functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) is a medical imaging modality that indirectly measures neural activity by observing the local hemodynamics, or blood oxygen level dependent signal (BOLD). fMRI data offers a range of insights, and can be roughly divided into two categories:

- Task related fMRI is acquired as the subject is performing a sequence of timed experimental conditions. In block-design experiments, the conditions are present for short periods of time (e.g., 10 seconds) and are alternated with periods of rest. Event-related experiments rely on a random sequence of stimuli and use a single time point to denote each condition. The standard approach to analyze task related fMRI is the general linear model (GLM).[76]

- Resting state fMRI is acquired in the absence of any experimental task. Typically, the objective is to study the intrinsic network structure of the brain. Observations made during rest have also been linked to specific cognitive processes such as encoding or reflection. Most studies of resting state fMRI focus on low frequency fluctuations of the fMRI signal (LF-BOLD). Seminal discoveries include the default network,[77] a comprehensive cortical parcellation,[78] and the linking of network characteristics to behavioral parameters.

There is a rich set of methodology used to analyze functional neuroimaging data, and there is often no consensus regarding the best method. Instead, researchers approach each problem independently and select a suitable model/algorithm. In this context there is a relatively active exchange among neuroscience, computational biology, statistics, and machine learning communities. Prominent approaches include

- Massive univariate approaches that probe individual voxels in the imaging data for a relationship to the experiment condition. The prime approach is the general linear model.[76]

- Multivariate- and classifier based approaches, often referred to as multi voxel pattern analysis or multi-variate pattern analysis probe the data for global and potentially distributed responses to an experimental condition. Early approaches used support vector machines to study responses to visual stimuli.[79] Recently, alternative pattern recognition algorithms have been explored, such as random forest based gini contrast [80] or sparse regression and dictionary learning.[81]

- Functional connectivity analysis studies the intrinsic network structure of the brain, including the interactions between regions. The majority of such studies focus on resting state data to parcelate the brain [78] or to find correlates to behavioral measures.[82] Task specific data can be used to study causal relationships among brain regions (e.g., dynamic causal mapping[83]).

When working with large cohorts of subjects, the normalization (registration) of individual subjects into a common reference frame is crucial. A body of work and tools exist to perform normalization based on anatomy (FSL, FreeSurfer, SPM). Alignment taking spatial variability across subjects into account is a more recent line of work. Examples are the alignment of the cortex based on fMRI signal correlation,[84] the alignment based on the global functional connectivity structure both in task-, or resting state data,[85] and the alignment based on stimulus specific activation profiles of individual voxels.[86]

Software

[edit]Software for medical image computing is a complex combination of systems providing IO, visualization and interaction, user interface, data management and computation. Typically system architectures are layered to serve algorithm developers, application developers, and users. The bottom layers are often libraries and/or toolkits which provide base computational capabilities; while the top layers are specialized applications which address specific medical problems, diseases, or body systems.

Additional notes

[edit]Medical image computing is also related to the field of computer vision. An international society, The MICCAI Society, represents the field and organizes an annual conference and associated workshops. Proceedings for this conference are published by Springer in the Lecture Notes in Computer Science series.[87] In 2000, N. Ayache and J. Duncan reviewed the state of the field.[88]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Perera Molligoda Arachchige, Arosh S.; Svet, Afanasy (2021-09-10). "Integrating artificial intelligence into radiology practice: undergraduate students' perspective". European Journal of Nuclear Medicine and Molecular Imaging. 48 (13): 4133–4135. doi:10.1007/s00259-021-05558-y. ISSN 1619-7089. PMID 34505175. S2CID 237459138.

- ^ Forghani, M.; Forouzanfar, M.; Teshnehlab, M. (2010). "Parameter optimization of improved fuzzy c-means clustering algorithm for brain MR image segmentation". Engineering Applications of Artificial Intelligence. 23 (2): 160–168. doi:10.1016/j.engappai.2009.10.002.

- ^ J Gee; M Reivich; R Bajcsy (1993). "Elastically Deforming a Three-Dimensional Atlas to Match Anatomical Brain Images". Journal of Computer Assisted Tomography. 17 (1): 225–236. doi:10.1097/00004728-199303000-00011. PMID 8454749. S2CID 25781937.

- ^ MR Sabuncu; BT Yeo; K Van Leemput; B Fischl; P Golland (June 2010). "A Generative Model for Image Segmentation Based on Label Fusion". IEEE Transactions on Medical Imaging. 29 (10): 1714–1729. Bibcode:2010ITMI...29.1714S. doi:10.1109/TMI.2010.2050897. PMC 3268159. PMID 20562040.

- ^ Cootes TF, Taylor CJ, Cooper DH, Graham J (1995). "Active shape models-their training and application" (PDF). Computer Vision and Image Understanding. 61 (1): 38–59. doi:10.1006/cviu.1995.1004. S2CID 15242659.

- ^ Cootes, T.F.; Edwards, G.J.; Taylor, C.J. (2001). "Active appearance models". IEEE Transactions on Pattern Analysis and Machine Intelligence. 23 (6): 681–685. Bibcode:2001ITPAM..23..681C. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.128.4967. doi:10.1109/34.927467.

- ^ G. Zheng; S. Li; G. Szekely (2017). Statistical Shape and Deformation Analysis. Academic Press. ISBN 9780128104941.

- ^ R. Goldenberg, R. Kimmel, E. Rivlin, and M. Rudzsky (2001). "Fast geodesic active contours" (PDF). IEEE Transactions on Image Processing. 10 (10): 1467–1475. Bibcode:2001ITIP...10.1467G. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.35.1977. doi:10.1109/83.951533. PMID 18255491.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Karasev, P.; Kolesov I.; Chudy, K.; Vela, P.; Tannenbaum, A. (2011). "Interactive MRI segmentation with controlled active vision". IEEE Conference on Decision and Control and European Control Conference. pp. 2293–2298. doi:10.1109/CDC.2011.6161453. ISBN 978-1-61284-801-3. PMC 3935399. PMID 24584213.

- ^ K. Mikula, N. Peyriéras, M. Remešíková, A.Sarti: 3D embryogenesis image segmentation by the generalized subjective surface method using the finite volume technique. Proceedings of FVCA5 – 5th International Symposium on Finite Volumes for Complex Applications, Hermes Publ., Paris 2008.

- ^ A. Sarti, G. Citti: Subjective surfaces and Riemannian mean curvature flow graphs. Acta Math. Univ. Comenian. (N.S.) 70 (2000), 85–103.

- ^ A. Sarti, R. Malladi, J.A. Sethian: Subjective Surfaces: A Method for Completing Missing Boundaries. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. mi 12, No. 97 (2000), 6258–6263.

- ^ A. Sarti, R. Malladi, J.A. Sethian: Subjective Surfaces: A Geometric Model for Boundary Completion, International Journal of Computer Vision, mi 46, No. 3 (2002), 201–221.

- ^ Badrinarayanan, Vijay; Kendall, Alex; Cipolla, Roberto (2015-11-02). "SegNet: A Deep Convolutional Encoder-Decoder Architecture for Image Segmentation". arXiv:1511.00561 [cs.CV].

- ^ Ronneberger, Olaf; Fischer, Philipp; Brox, Thomas (2015-05-18). "U-Net: Convolutional Networks for Biomedical Image Segmentation". arXiv:1505.04597 [cs.CV].

- ^ He, Kaiming; Zhang, Xiangyu; Ren, Shaoqing; Sun, Jian (June 2016). "Deep Residual Learning for Image Recognition". 2016 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR). Las Vegas, NV, USA: IEEE. pp. 770–778. doi:10.1109/CVPR.2016.90. ISBN 978-1-4673-8851-1. S2CID 206594692.

- ^ Ahmad, Ibtihaj; Xia, Yong; Cui, Hengfei; Islam, Zain Ul (2023-05-01). "AATSN: Anatomy Aware Tumor Segmentation Network for PET-CT volumes and images using a lightweight fusion-attention mechanism". Computers in Biology and Medicine. 157 106748. doi:10.1016/j.compbiomed.2023.106748. ISSN 0010-4825. PMID 36958235. S2CID 257489603.

- ^ Vaswani, Ashish; Shazeer, Noam; Parmar, Niki; Uszkoreit, Jakob; Jones, Llion; Gomez, Aidan N.; Kaiser, Lukasz; Polosukhin, Illia (2017-06-12). "Attention Is All You Need". arXiv:1706.03762 [cs.CL].

- ^ Sorin, Vera; Barash, Yiftach; Konen, Eli; Klang, Eyal (August 2020). "Creating Artificial Images for Radiology Applications Using Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs) – A Systematic Review". Academic Radiology. 27 (8): 1175–1185. doi:10.1016/j.acra.2019.12.024. ISSN 1076-6332. PMID 32035758. S2CID 211072078.

- ^ Ehsani Rad, Abdolvahab; Mohd Rahim Mohd Shafry; Rehman Amjad; Altameem Ayman; Saba Tanzila (May 2013). "Evaluation of Current Dental Radiographs Segmentation Approaches in Computer-aided Applications". IETE Technical Review. 30 (3): 210. doi:10.4103/0256-4602.113498 (inactive 1 July 2025). S2CID 62571134.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: DOI inactive as of July 2025 (link) - ^ Lisa Gottesfeld Brown (1992). "A survey of image registration techniques". ACM Computing Surveys. 24 (4): 325–376. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.35.2732. doi:10.1145/146370.146374. S2CID 14576088.

- ^ J. Maintz; M. Viergever (1998). "A survey of medical image registration". Medical Image Analysis. 2 (1): 1–36. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.46.4959. doi:10.1016/S1361-8415(01)80026-8. PMID 10638851.

- ^ J. Hajnal; D. Hawkes; D. Hill (2001). Medical Image Registration. Baton Rouge, Florida: CRC Press.

- ^ Barbara Zitová; Jan Flusser (2003). "Image registration methods: a survey". Image Vision Comput. 21 (11): 977–1000. doi:10.1016/S0262-8856(03)00137-9. hdl:10338.dmlcz/141595.

- ^ J. P. W. Pluim; J. B. A. Maintz; M. A. Viergever (2003). "Mutual information based registration of medical images: A survey". IEEE Trans. Med. Imaging. 22 (8): 986–1004. Bibcode:2003ITMI...22..986P. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.197.6513. doi:10.1109/TMI.2003.815867. PMID 12906253. S2CID 2605077.

- ^ Grenander, Ulf; Miller, Michael I. (1998). "Computational anatomy: an emerging discipline". Q. Appl. Math. LVI (4): 617–694. doi:10.1090/qam/1668732.

- ^ P. A. Viola (1995). Alignment by Maximization of Mutual Information (Thesis). Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

- ^ C. Wachinger; T. Klein; N. Navab (2011). "Locally adaptive Nakagami-based ultrasound similarity measures". Ultrasonics. 52 (4): 547–554. doi:10.1016/j.ultras.2011.11.009. PMID 22197152.

- ^ C. Wachinger; N. Navab (2012). "Entropy and Laplacian images: structural representations for multi-modal registration". Medical Image Analysis. 16 (1): 1–17. doi:10.1016/j.media.2011.03.001. PMID 21632274.

- ^ Hill, Derek LG; Hawkes, David J (1994-04-01). "Medical image registration using knowledge of adjacency of anatomical structures". Image and Vision Computing. 12 (3): 173–178. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.421.5162. doi:10.1016/0262-8856(94)90069-8. ISSN 0262-8856.

- ^ Toth, Daniel; Panayiotou, Maria; Brost, Alexander; Behar, Jonathan M.; Rinaldi, Christopher A.; Rhode, Kawal S.; Mountney, Peter (2016-10-17). "Registration with Adjacent Anatomical Structures for Cardiac Resynchronization Therapy Guidance". Statistical Atlases and Computational Models of the Heart. Imaging and Modelling Challenges (Submitted manuscript). Lecture Notes in Computer Science. Vol. 10124. pp. 127–134. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-52718-5_14. ISBN 9783319527178. S2CID 1698371.

- ^ Pielawski, N., Wetzer, E., Ofverstedt, J., Lu, J., Wählby, C., Lindblad, J., & Sladoje, N. (2020). "CoMIR: Contrastive Multimodal Image Representation for Registration". In Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems (pp. 18433–18444). Curran Associates, Inc.

- ^ M. De Craene; A. B. d Aische; B. Macq; S. K. Warfield (2004). "Multi-subject Registration for Unbiased Statistical Atlas Construction" (PDF). Medical Image Computing and Computer-Assisted Intervention – MICCAI 2004. Lecture Notes in Computer Science. Vol. 3216. pp. 655–662. doi:10.1007/978-3-540-30135-6_80. ISBN 978-3-540-22976-6.

- ^ C. J. Twining; T. Cootes; S. Marsland; V. Petrovic; R. Schestowitz; C. Taylor (2005). "A Unified Information-Theoretic Approach to Groupwise Non-rigid Registration and Model Building". Information Processing in Medical Imaging. Lecture Notes in Computer Science. Vol. 19. pp. 1–14. doi:10.1007/11505730_1. ISBN 978-3-540-26545-0. PMID 17354680.

- ^ "The MNI brain and the Talairach atlas".

- ^ M. Sabuncu; S. K. Balci; M. E. Shenton; P. Golland (2009). "Image-driven Population Analysis through Mixture Modeling". IEEE Transactions on Medical Imaging. 28 (9): 1473–1487. Bibcode:2009ITMI...28.1473S. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.158.3690. doi:10.1109/TMI.2009.2017942. PMC 2832589. PMID 19336293.

- ^ J. Ashburner; K.J. Friston (2000). "Voxel-Based Morphometry – The Methods". NeuroImage. 11 (6): 805–821. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.114.9512. doi:10.1006/nimg.2000.0582. PMID 10860804. S2CID 16777465.

- ^ C. Davatzikos (2004). "Why voxel-based morphometric analysis should be used with great caution when characterizing group differences". NeuroImage. 23 (1): 17–20. doi:10.1016/j.neuroimage.2004.05.010. PMID 15325347. S2CID 7452089.

- ^ K.J. Friston; W.D. Penny; C. Phillips; S.J. Kiebel; G. Hinton; J. Ashburner (2002). "Classical and Bayesian Inference in Neuroimaging: Theory". NeuroImage. 16 (2): 465–483. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.128.8333. doi:10.1006/nimg.2002.1090. PMID 12030832. S2CID 14911371.

- ^ Yong Fan; Nematollah Batmanghelich; Chris M. Clark; Christos Davatzikos (2008). "Spatial patterns of brain atrophy in MCI patients, identified via high-dimensional pattern classification, predict subsequent cognitive decline". NeuroImage. 39 (4): 1731–1743. doi:10.1016/j.neuroimage.2007.10.031. PMC 2861339. PMID 18053747.

- ^ Rémi Cuingnet; Emilie Gerardin; Jérôme Tessieras; Guillaume Auzias; Stéphane Lehéricy; Marie-Odile Habert; Marie Chupin; Habib Benali; Olivier Colliot (2011). "The Alzheimer's Disease Neuroimaging Initiative, Automatic classification of patients with Alzheimer's disease from structural MRI: A comparison of ten methods using the ADNI database" (PDF). NeuroImage. 56 (2): 766–781. doi:10.1016/j.neuroimage.2010.06.013. PMID 20542124. S2CID 628131.

- ^ Y. Wang; Y. Fan; P. Bhatt P; C. Davatzikos (2010). "High-dimensional pattern regression using machine learning: from medical images to continuous clinical variables". NeuroImage. 50 (4): 1519–35. doi:10.1016/j.neuroimage.2009.12.092. PMC 2839056. PMID 20056158.

- ^ Benoît Magnin; Lilia Mesrob; Serge Kinkingnéhun; Mélanie Pélégrini-Issac; Olivier Colliot; Marie Sarazin; Bruno Dubois; Stéphane Lehéricy; Habib Benali (2009). "Support vector machine-based classification of Alzheimer's disease from whole-brain anatomical MRI". Neuroradiology. 51 (2): 73–83. doi:10.1007/s00234-008-0463-x. PMID 18846369. S2CID 285128.

- ^ a b N.K. Batmanghelich; B. Taskar; C. Davatzikos (2012). "Generative-discriminative basis learning for medical imaging". IEEE Trans Med Imaging. 31 (1): 51–69. Bibcode:2012ITMI...31...51B. doi:10.1109/TMI.2011.2162961. PMC 3402718. PMID 21791408.

- ^ a b Glenn Fung; Jonathan Stoeckel (2007). "SVM feature selection for classification of SPECT images of Alzheimer's disease using spatial information". Knowledge and Information Systems. 11 (2): 243–258. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.62.6245. doi:10.1007/s10115-006-0043-5. S2CID 9901011.

- ^ a b R. Chaves; J. Ramírez; J.M. Górriz; M. López; D. Salas-Gonzalez; I. Álvarez; F. Segovia (2009). "SVM-based computer-aided diagnosis of the Alzheimer's disease using t-test NMSE feature selection with feature correlation weighting". Neuroscience Letters. 461 (3): 293–297. doi:10.1016/j.neulet.2009.06.052. PMID 19549559. S2CID 9981775.

- ^ a b

Yanxi Liu; Leonid Teverovskiy; Owen Carmichael; Ron Kikinis; Martha Shenton; Cameron S. Carter; V. Andrew Stenger; Simon Davis; Howard Aizenstein; James T. Becker (2004). "Discriminative MR Image Feature Analysis for Automatic Schizophrenia and Alzheimer's Disease Classification" (PDF). Medical Image Computing and Computer-Assisted Intervention – MICCAI 2004. Lecture Notes in Computer Science. Vol. 3216. pp. 393–401. doi:10.1007/978-3-540-30135-6_48. ISBN 978-3-540-22976-6.

{{cite book}}:|journal=ignored (help) - ^ Savio A.; Graña M. (2013). "Deformation based feature selection for Computer Aided Diagnosis of Alzheimer's Disease". Expert Systems with Applications. 40 (5): 1619–1628. doi:10.1016/j.eswa.2012.09.009. ISSN 0957-4174.

- ^ R. Filipovych; S. M. Resnick; C. Davatzikos (2011). "Semi-supervised cluster analysis of imaging data". NeuroImage. 54 (3): 2185–2197. doi:10.1016/j.neuroimage.2010.09.074. PMC 3008313. PMID 20933091.

- ^ STEP research roadmap Archived 2008-08-28 at the Wayback Machine. europhysiome.org

- ^ J. W. Fenner; B. Brook; G. Clapworthy; P. V. Coveney; V. Feipel; H. Gregersen; D. R. Hose; P. Kohl; P. Lawford; K. M. McCormack; D. Pinney; S. R. Thomas; S. Van Sint Jan; S. Waters; M. Viceconti (2008). "The EuroPhysiome, STEP and a roadmap for the virtual physiological human" (PDF). Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society A. 366 (1878): 2979–2999. Bibcode:2008RSPTA.366.2979F. doi:10.1098/rsta.2008.0089. hdl:2013/ULB-DIPOT:oai:dipot.ulb.ac.be:2013/98205. PMID 18559316. S2CID 1211981.

- ^ J. B. Bassingthwaighte (2000). "Strategies for the Physiome Project". Annals of Biomedical Engineering. 28 (8): 1043–1058. doi:10.1114/1.1313771. PMC 3425440. PMID 11144666.

- ^ P. J. Hunter; T. K. Borg (2003). "Integration from proteins to organs: The Physiome Project". Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 4 (3): 237–243. doi:10.1038/nrm1054. PMID 12612642. S2CID 25185270.

- ^ R. L.Winslow; N. Trayanova; D. Geman; M. I. Miller (2012). "Computational medicine: Translating models to clinical care". Sci. Transl. Med. 4 (158): 158rv11. doi:10.1126/scitranslmed.3003528. PMC 3618897. PMID 23115356.

- ^ N. Ayache, J.-P. Boissel, S. Brunak, G. Clapworthy, G. Lonsdale, J. Fingberg, A. F. Frangi, G.Deco, P. J. Hunter, P.Nielsen, M.Halstead, D. R. Hose, I. Magnin, F. Martin-Sanchez, P. Sloot, J. Kaandorp, A. Hoekstra, S. Van Sint Jan, and M. Viceconti (2005) "Towards virtual physiological human: Multilevel modelling and simulation of the human anatomy and physiology". Directorate General INFSO & Directorate General JRC, White paper

- ^ Boulfelfel D.; Rangayyan R.M.; Hahn L.J.; Kloiber R.; Kuduvalli G.R. (1994). "Restoration of single photon emission computed tomography images by the Kalman filter". IEEE Transactions on Medical Imaging. 13 (1): 102–109. doi:10.1109/42.276148. PMID 18218487.

- ^ Angenent, S.; Pichon, E.; Tannenbaum, A. (2006). "Mathematical methods in medical image processing". Bulletin of the AMS. 43 (3): 365–396. doi:10.1090/S0273-0979-06-01104-9. PMC 3640423. PMID 23645963.

- ^ P Basser; J Mattiello; D LeBihan (January 1994). "MR diffusion tensor spectroscopy, imaging". Biophysical Journal. 66 (1): 259–267. Bibcode:1994BpJ....66..259B. doi:10.1016/S0006-3495(94)80775-1. PMC 1275686. PMID 8130344.

- ^ P Fillard; X Pennec; V Arsigny; N Ayache (2007). "Clinical DT-MRI estimation, smoothing,, fiber tracking with log-Euclidean metrics". IEEE Transactions on Medical Imaging. 26 (11): 1472–1482. Bibcode:2007ITMI...26.1472F. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.218.6380. doi:10.1109/TMI.2007.899173. PMID 18041263.

- ^ S-K Song; S-W Sun; M Ramsbottom; C Cheng; J Russell; A Cross (November 2002). "Dysmyelination Revealed through MRI as Increased Radial (but Unchanged Axial) Diffusion of Water". NeuroImage. 13 (3): 1429–1436. doi:10.1006/nimg.2002.1267. PMID 12414282. S2CID 43229972.

- ^ P Barzo; A Marmarou; P Fatouros; K Hayasaki; F Corwin (December 1997). "Contribution of vasogenic and cellular edema to traumatic brain swelling measured by diffusion-weighted imaging". Journal of Neurosurgery. 87 (6): 900–907. doi:10.3171/jns.1997.87.6.0900. PMID 9384402.

- ^ D Alexander; C Pierpaoli; P Basser (January 2001). "Spatial transformation of diffusion tensor magnetic resonance images" (PDF). IEEE Transactions on Medical Imaging. 20 (11): 1131–1139. Bibcode:2001ITMI...20.1131A. doi:10.1109/42.963816. PMID 11700739. S2CID 6559551.

- ^ Y Cao; M Miller; S Mori; R Winslow; L Younes (June 2006). "Diffeomorphic Matching of Diffusion Tensor Images". Proceedings of IEEE Computer Society Conference on Computer Vision, Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Workshop on Mathematical Methods in Biomedical Image Analysis (MMBIA 2006). New York. p. 67. doi:10.1109/CVPRW.2006.65. PMC 2920614.

- ^ Z Wang; B Vemuri (October 2005). "DTI segmentation using an information theoretic tensor dissimilarity measure". IEEE Transactions on Medical Imaging. 24 (10): 1267–1277. Bibcode:2005ITMI...24.1267W. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.464.9059. doi:10.1109/TMI.2005.854516. PMID 16229414. S2CID 32724414.

- ^ Melonakos, J.; Pichon, E.; Angenent, S.; Tannenbaum, A. (2008). "Finsler active contours". IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 30 (3): 412–423. Bibcode:2008ITPAM..30..412M. doi:10.1109/TPAMI.2007.70713. PMC 2796633. PMID 18195436.

- ^ S Mori; B Crain; V Chacko; P van Zijl (February 1999). "Three-dimensional tracking of axonal projections in the brain by magnetic resonance imaging". Annals of Neurology. 45 (2): 265–269. doi:10.1002/1531-8249(199902)45:2<265::AID-ANA21>3.0.CO;2-3. PMID 9989633. S2CID 334903.

- ^ D Tuch; T Reese; M Wiegell; N Makris; J Belliveau; V Wedeen (October 2002). "High angular resolution diffusion imaging reveals intravoxel white matter fiber heterogeneity". Magnetic Resonance in Medicine. 48 (4): 577–582. doi:10.1002/mrm.10268. PMID 12353272.

- ^ D Tuch (December 2004). "Q-ball imaging". Magnetic Resonance in Medicine. 52 (6): 1358–1372. doi:10.1002/mrm.20279. PMID 15562495.

- ^ V Wedeen; P Hagmann; W-Y Tseng; T Reese (December 2005). "Mapping complex tissue architecture with diffusion spectrum magnetic resonance imaging". Magnetic Resonance in Medicine. 54 (6): 1377–1386. doi:10.1002/mrm.20642. PMID 16247738.

- ^ K Jansons; D Alexander (July 2003). "Persistent angular structure: new insights from diffusion magnetic resonance imaging data". Proceedings of Information Processing in Medical Imaging (IPMI) 2003, LNCS 2732. pp. 672–683. doi:10.1007/978-3-540-45087-0_56.

- ^ J-D Tournier; F Calamante; D Gadian; A Connelly (2007). "Direct estimation of the fiber orientation density function from diffusion-weighted MRI data using spherical deconvolution". NeuroImage. 23 (3): 1176–1185. doi:10.1016/j.neuroimage.2004.07.037. PMID 15528117. S2CID 24169627.

- ^ X Geng; T Ross; W Zhan; H Gu; Y-P Chao; C-P Lin; G Christensen; N Schuff; Y Yang (July 2009). "Diffusion MRI Registration Using Orientation Distribution Functions". Proceedings of Information Processing in Medical Imaging (IPMI) 2009, LNCS 5636. Vol. 21. pp. 626–637. doi:10.1007/978-3-642-02498-6_52. PMC 3860746.

- ^ P-T Yap; Y Chen; H An; Y Yang; J Gilmore; W Lin; D Shen (2011). "SPHERE: SPherical Harmonic Elastic REgistration of HARDI data". NeuroImage. 55 (2): 545–556. doi:10.1016/j.neuroimage.2010.12.015. PMC 3035740. PMID 21147231.

- ^ P Zhang; M Niethammer; D Shen; P-T Yap (2012). "Large Deformation Diffeomorphic Registration of Diffusion-Weighted Images" (PDF). Proceedings of Medical Image Computing and Computer-Assisted Intervention (MICCAI). doi:10.1007/978-3-642-33418-4_22.

- ^ M Descoteaux; R Deriche (September 2007). "Segmentation of Q-Ball Images Using Statistical Surface Evolution". Proceedings of Medical Image Computing and Computer-Assisted Intervention (MICCAI) 2007, LNCS 4792. pp. 769–776. doi:10.1007/978-3-540-75759-7_93.

- ^ a b Friston, K.; Holmes, A.; Worsley, K.; Poline, J.; Frith, C.; Frackowiak, R.; et al. (1995). "Statistical parametric maps in functional imaging: a general linear approach". Hum Brain Mapp. 2 (4): 189–210. doi:10.1002/hbm.460020402. S2CID 9898609.

- ^ Buckner, R. L.; Andrews-Hanna, J. R.; Schacter, D. L. (2008). "The brain's default network: anatomy, function, and relevance to disease". Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 1124 (1): 1–38. Bibcode:2008NYASA1124....1B. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.689.6903. doi:10.1196/annals.1440.011. PMID 18400922. S2CID 3167595.

- ^ a b Yeo, B. T. T.; Krienen, F. M.; Sepulcre, J.; Sabuncu, M. R.; Lashkari, D.; Hollinshead, M.; Roffman, J. L.; Smoller, J. W.; Zöllei, L.; Polimeni, J. R.; Fischl, B.; Liu, H.; Buckner, R. L. (2011). "The organization of the human cerebral cortex estimated by intrinsic functional connectivity". J Neurophysiol. 106 (3): 1125–65. doi:10.1152/jn.00338.2011. PMC 3174820. PMID 21653723.

- ^ J. V. Haxby; M. I. Gobbini; M. L. Furey; A. Ishai; J. L. Schouten; P. Pietrini (2001). "Distributed and overlapping representations of faces and objects in ventral temporal cortex". Science. 293 (5539): 2425–30. Bibcode:2001Sci...293.2425H. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.381.2660. doi:10.1126/science.1063736. PMID 11577229. S2CID 6403660.

- ^ Langs, G.; Menze, B. H.; Lashkari, D.; Golland, P. (2011). "Detecting stable distributed patterns of brain activation using Gini contrast". NeuroImage. 56 (2): 497–507. doi:10.1016/j.neuroimage.2010.07.074. PMC 3960973. PMID 20709176.

- ^ Varoquaux, G.; Gramfort, A.; Pedregosa, F.; Michel, V.; Thirion, B. (2011). "Multi-subject dictionary learning to segment an atlas of brain spontaneous activity". Inf Process Med Imaging. Vol. 22. pp. 562–73.

- ^ van den Heuvel, M. P.; Stam, C. J.; Kahn, R. S.; Hulshoff Pol, H. E. (2009). "Efficiency of functional brain networks and intellectual performance". J Neurosci. 29 (23): 7619–24. doi:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1443-09.2009. PMC 6665421. PMID 19515930.

- ^ Friston, K. (2003). "Dynamic causal modelling". NeuroImage. 19 (4): 1273–1302. doi:10.1016/S1053-8119(03)00202-7. PMID 12948688. S2CID 2176588.

- ^ Sabuncu, M. R.; Singer, B. D.; Conroy, B.; Bryan, R. E.; Ramadge, P. J.; Haxby, J. V. (2010). "Function-based Intersubject Alignment of Human Cortical Anatomy". Cerebral Cortex. 20 (1): 130–140. doi:10.1093/cercor/bhp085. PMC 2792192. PMID 19420007.

- ^ Langs, G.; Lashkari, D.; Sweet, A.; Tie, Y.; Rigolo, L.; Golby, A. J.; Golland, P. (2011). "Learning an atlas of a cognitive process in its functional geometry". Inf Process Med Imaging. Vol. 22. pp. 135–46.

- ^ Haxby, J. V.; Guntupalli, J. S.; Connolly, A. C.; Halchenko, Y. O.; Conroy, B. R.; Gobbini, M. I.; Hanke, M.; Ramadge, P. J. (2011). "A common, high-dimensional model of the representational space in human ventral temporal cortex". Neuron. 72 (2): 404–416. doi:10.1016/j.neuron.2011.08.026. PMC 3201764. PMID 22017997.

- ^ Wells, William M; Colchester, Alan; Delp, Scott (1998). Lecture Notes in Computer Science (Submitted manuscript). Vol. 1496. doi:10.1007/BFb0056181. ISBN 978-3-540-65136-9. S2CID 31031333.

- ^ JS Duncan; N Ayache (2000). "Medical image analysis: Progress over two decades and the challenges ahead". IEEE Transactions on Pattern Analysis and Machine Intelligence. 22 (1): 85–106. Bibcode:2000ITPAM..22...85D. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.410.8744. doi:10.1109/34.824822.

Journals on medical image computing

[edit]- Medical Image Analysis (MedIA) ; also the official journal of The MICCAI Society, which organizes the Annual MICCAI Conference a premier conference for medical image computing

- IEEE Transactions on Medical Imaging (IEEE TMI)

- Medical Physics

- Journal of Digital Imaging (JDI) ; the official journal of the Society of Imaging Informatics

- Computerized Medical Imaging and Graphics

- Journal of Computer Aided Radiology and Surgery

- BMC Medical Imaging

In addition the following journals occasionally publish articles describing methods and specific clinical applications of medical image computing or modality specific medical image computing