Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Immurement

View on Wikipedia

Immurement (from Latin im- 'in' and murus 'wall'; lit. 'walling in'), also called immuration or live entombment, is a form of imprisonment, usually until death, in which someone is placed within an enclosed space without exits.[1] This includes instances where people have been enclosed in extremely tight confinement, such as within a coffin. When used as a means of execution, the prisoner is simply left to die from starvation or dehydration. This form of execution is distinct from being buried alive, in which the victim typically dies of asphyxiation. By contrast, immurement has also occasionally been used as an early form of life imprisonment, in which cases the victims were regularly fed and given water. There have been a few cases in which people have survived for months or years after being walled up, as well as some people, such as anchorites, who were voluntarily immured.

Notable examples of immurement as an established execution practice (with death from thirst or starvation as the intended aim) are attested. In the Roman Empire, Vestal Virgins faced live entombment as punishment if they were found guilty of breaking their chastity vows. Immurement has also been well established as a punishment of robbers in Persia, even into the early 20th century. Some ambiguous evidence exists of immurement as a practice of coffin-type confinement in Mongolia. One famous, but likely mythical, immurement was that of Anarkali by Emperor Akbar because of her supposed relationship with Prince Saleem.

Isolated incidents of immurement, rather than elements of continuous traditions, are attested or alleged from numerous other parts of the world. Instances of immurement as an element of massacre within the context of war or revolution are also noted. Entombing living persons as a type of human sacrifice is also reported, for example, as part of grand burial ceremonies in some cultures.

As a motif in legends and folklore, many tales of immurement exist. In the folklore, immurement is prominent as a form of capital punishment, but its use as a type of human sacrifice to make buildings sturdy has many tales attached to it as well. Skeletal remains have been, from time to time, found behind walls and in hidden rooms, and on several occasions have been asserted to be evidence of such sacrificial or punitive practices.

History

[edit]Europe

[edit]

According to Finnish legend, a young maiden was wrongfully immured into the castle wall of Olavinlinna as a punishment for treason. The subsequent growth of a rowan tree at the location of her execution, whose flowers were as white as her innocence and berries as red as her blood, inspired a ballad.[2] Similar legends stem from Haapsalu,[3] Kuressaare,[4] Põlva[5] and Visby.[6]

According to a Latvian legend, as many as three people might have been immured in tunnels under the Grobiņa Castle. A daughter of a knight living in the castle did not approve of her father's choice of a young nobleman as her future husband. Said knight also pillaged surrounding areas and took prisoners to live in the tunnels, among these a handsome young man whom the daughter took a liking to, helping him escape. Her fate was not so lucky as the knight and his future son-in-law punished her by immuring her in one of the tunnels. Another nobleman's daughter and a Swedish soldier are also said to be immured in one of the tunnels after she had fallen in love with the Swedish soldier and requested her father to allow her to marry him. According to another legend, a maiden and a servant were immured after a failed attempt at spying on Germans to gain intelligence on their plans for what is now Latvia.[7]

In book 3 of his History of the Peloponnesian War, Thucydides goes into great detail on the revolution that broke out at Corfu in 427 BC:[8]

Death thus raged in every shape; and, as usually happens at such times, there was no length to which violence did not go; sons were killed by their fathers, and suppliants dragged from the altar or slain upon it; while some were even walled up in the temple of Dionysus and died there.

The Vestal Virgins in ancient Rome constituted a class of priestesses whose principal duty was to maintain the sacred fire dedicated to Vesta (goddess of the home and the family), and they lived under a strict vow of chastity and celibacy. If that vow of chastity was broken, the offending priestess was immured alive as follows:[9]

When condemned by the college of pontifices, she was stripped of her vittae and other badges of office, was scourged, attired like a corpse, placed in a closed litter, borne through the forum attended by her weeping kindred with all the ceremonies of a real funeral to a rising ground called the Campus Sceleratus. This was located just within the city walls, close to the Colline gate. A small vault underground had been previously prepared, containing a couch, a lamp, and a table with a little food. The pontifex maximus, having lifted up his hands to heaven and uttered a secret prayer, opened the litter, led forth the culprit, and placed her on the steps of the ladder which gave access to the subterranean cell. He delivered her over to the common executioner and his assistants, who led her down, drew up the ladder, and having filled the pit with earth until the surface was level with the surrounding ground, left her to perish deprived of all the tributes of respect usually paid to the spirits of the departed.

The order of the Vestal Virgins existed for about 1,000 years, but only about 10 effected immurements are attested in extant sources.[10]

Flavius Basiliscus, emperor of the Eastern Roman Empire from AD 475–476, was deposed, and in winter he was sent to Cappadocia with his family. There they were imprisoned in either a dry cistern,[11] or a tower,[12] and perished. The historian Procopius said they died exposed to cold and hunger,[13] while other sources, such as Priscus, merely speaks of death by starvation.[14]

The patriarch of Aquileia, Poppo of Treffen (r. 1019–1045), was a mighty secular potentate, and in 1044 he sacked Grado. The newly elected Doge of Venice, Domenico I Contarini, captured him and allegedly let him be buried up to his neck, and left guards to watch over him until he died.[15]

In 1149, Duke Otto III of Olomouc of the Moravian Přemyslid dynasty immured the abbot Deocar and 20 monks in the refectory in the monastery of Rhadisch, where they starved to death. Ostensibly this was because one of the monks had fondled his wife Duranna when she had spent the night there. However, Otto III confiscated the monastery's wealth, and some said this was the motive for the immurement.[16]

In the ruins of Thornton Abbey, Lincolnshire, an immured skeleton was found behind a wall along with a table, a book, and a candlestick. By some, he is believed to be the fourteenth abbot, immured for some crime he had committed.[17]

The actual punishment meted out to men found guilty of paederasty might vary between different status groups. In 1409 and 1532 in Augsburg, two men were burned alive for their offences; a rather different fate was prescribed to four clerics found guilty of the same offence in another 1409 case. Instead of burning, they were locked into a wooden casket that was hung up in the Perlachturm, and they starved to death.[18]

After confessing in an Inquisition Court to an alleged conspiracy involving lepers, the Jewry, the King of Granada, and the Sultan of Babylon, Guillaume Agassa, head of the leper asylum at Lestang, was condemned in 1322 to be immured in shackles for life.[19]

Hungarian countess Elizabeth Báthory de Ecsed (Báthory Erzsébet in Hungarian; 1560–1614) was immured in a set of rooms in 1610 for the death of several girls, with figures being as high as several hundred, though the actual number of victims is uncertain. The highest number of victims cited during the trial of Báthory's accomplices was 650; this number comes from a claim by a servant girl named Susannah that Jakab Szilvássy, Báthory's court official, had seen that figure in one of Báthory's private books. The book was never revealed and Szilvássy never mentioned it in his testimony.[20] Being labeled the most prolific female serial killer in history has earned her the nickname of the "Blood Countess", and she is often compared with Vlad III the Impaler of Wallachia in folklore. She was allowed to live in immurement until she died, four years after being sealed, ultimately dying of causes other than starvation; evidently her rooms were well supplied with food. According to other sources (written documents from the visit of priests, July 1614), she was able to move freely and unhindered within the castle, more akin to house arrest.[21][22]

Asceticism

[edit]A particularly severe form of asceticism within Christianity is that of anchorites, who typically allowed themselves to be immured, and subsisted on minimal food. For example, in the 4th century AD, one nun named Alexandra immured herself in a tomb for ten years with a tiny aperture enabling her to receive meager provisions. Saint Jerome (c. 340–420) spoke of one follower who spent his entire life in a cistern, consuming no more than five figs a day.[23] Gregory of Tours, in his writings, related two stories of immurement, including that of a nun in Poitiers. She was immured in a cell at her own request after experiencing a vision of Salvius of Albi, who was himself immured for a period prior to becoming bishop.[24]

In Catholic monastic tradition, there existed a type of enforced, solitary confinement for nuns or monks who had broken their vows of chastity, or espoused heretical ideas. Henry Charles Lea offers an example:[25]

In the case of Jeanne, widow of B. de la Tour, a nun of Lespenasse, in 1246, who had committed acts of both Catharan and Waldensian heresy, and had prevaricated in her confession, the sentence was confinement in a separate cell in her own convent, where no one was to enter or see her, her food being pushed in through an opening left for the purpose—in fact, the living tomb known as the "in pace".

Indeed, the punitive function of in pace was that of perpetual seclusion. The guilty were condemned not to starve to death quickly, but to live in utter isolation from other human beings. As Lea describes in a footnote to this case:[26]

The cruelty of the monastic system of imprisonment known as in pace, or vade in pacem, was such that those subjected to it speedily died in all the agonies of despair. In 1350 the Archbishop of Toulouse appealed to King John to interfere for its mitigation, and he issued an Ordonnance that the superior of the convent should twice a month visit and console the prisoner, who, moreover, should have the right twice a month to ask for the company of one of the monks. Even this slender innovation provoked the bitterest resistance of the Dominicans and Franciscans, who appealed to Pope Clement VI, but in vain.

Meanwhile, Sir Walter Scott, himself an antiquarian, favors the alternative in a remark to his epic poem Marmion (1808):[27]

It is well known, that the religious, who broke their vows of chastity, were subjected to the same penalty as the Roman Vestals in a similar case. A small niche, sufficient to enclose their bodies, was made in the massive wall of the convent; a slender pittance of food and water was deposited in it and the awful words Vade in pace, were the signal for immuring the criminal. It is not likely that, in latter times, this punishment was often resorted to; but, among the ruins of the abbey of Coldingham were some years ago discovered the remains of a female skeleton which, from the shape of the niche, and the position of the figure seemed to be that of an immured nun.

The practice of immuring nuns or monks on breaches of chastity continued for several centuries into the early modern period. Francesca Medioli writes the following in her essay "Dimensions of the Cloister":[28]

At Lodi in 1662 Sister Antonia Margherita Limera stood trial for having introduced a man into her cell and entertained him for a few days; she was sentenced to be walled in alive on a diet of bread and water. In the same year, the trial for breach of enclosure and sexual intercourse against the cleric Domenico Cagianella and Sister Vincenza Intanti of the convent of San Salvatore in Ariano had an identical outcome.

Asia

[edit]In the ancient Sumerian city of Ur some graves (as early as 2500 BC.) clearly show the burial of attendants, along with that of the principal dead person. In one such grave, as Gerda Lerner wrote on page 60 of her book The Creation of Patriarchy:

The human sacrifices were probably first drugged or poisoned, as evidenced by a drinking cup near each body, then the pit was immured, and covered with earth[29]

The Neo-Assyrian Empire is notorious for its brutal repression techniques. Several of its rulers memorialized their victories in self-congratulatory detail. Here is a commemoration Ashurnasirpal II (r. 883–859 BC) made that includes immurement:[30]

I erected a wall in front of the great gate of the city. I flayed the chiefs and covered this wall with their skins. Some of them were walled in alive in the masonry; others were impaled along the wall. I flayed a great number of them in my presence, and I clothed the wall with their skins. I collected their heads in the form of crowns, and their corpses I pierced in the shape of garlands ... My figure blooms on the ruins; in the glutting of my rage I find my content

Émile Durkheim in his work Suicide writes the following about certain followers of Amida Buddha:[31]

The sectarians of Amida have themselves immured in caverns where there is barely space to be seated and where they can breathe only through an air shaft. There they quietly allow themselves to die of hunger.

By popular legend, Anarkali was immured between two walls in Lahore by order of Mughal Emperor Akbar for having a relationship with crown prince Salim (later Emperor Jehangir) in the 16th century. A bazaar developed around the site, and was named Anarkali Bazaar in her honour.[32] A tradition existed in Persia of walling up criminals and leaving them to die of hunger or thirst. The traveller M. E. Hume-Griffith stayed in Persia from 1900 to 1903, and she wrote the following:[33]

Another sad sight to be seen in the desert sometimes, are brick pillars in which some unfortunate victim is walled up alive ... The victim is put into the pillar, which is half built up in readiness; then if the executioner is merciful he will cement quickly up to the face, and death comes speedily. But sometimes a small amount of air is allowed to permeate through the bricks, and in this case the torture is cruel and the agony prolonged. Men bricked up in this way have been heard groaning and calling for water at the end of three days.

Travelling back and forth to Persia from 1630 to 1668 as a gem merchant, Jean-Baptiste Tavernier observed much the same custom that Hume-Griffith noted some 250 years later. Tavernier notes that immuring was principally a punishment for thieves, and that immurement left the convict's head out in the open. According to him, many of these individuals would implore passers-by to cut off their heads, an amelioration of the punishment forbidden by law.[34] John Fryer,[35] travelling Persia in the 1670s, writes:[36]

From this Plain to Lhor, both in the Highways, and on the high Mountains, were frequent Monuments of Thieves immured in Terror of others who might commit the like Offence; they having literally a Stone-Doublet, whereas we say metaphorically, when any is in Prison, He has it Stone Doublet on; for these are plastered up, all but their Heads, in a round Stone Tomb, which are left out, not out of kindness, but to expose them to the Injury of the Weather, and Assaults of the Birds of Prey, who wreak their Rapin with as little Remorse, as they did devour their Fellow-Subjects.

In the late 1650s, various sons of the Mughal emperor Shah Jahan became embroiled in wars of succession, in which Aurangzeb was victorious. One of his half-brothers, Shah Shujah proved particularly troublesome, but in 1661 Aurangzeb defeated him, and Shah Shuja and his family sought the protection of the King of Arakan. According to Francois Bernier, the King reneged on his promise of asylum, and Shuja's sons were decapitated, while his daughters were immured and died of starvation.[37]

During Mughal rule in early 18th century India, the two youngest sons of Guru Gobind Singh were sentenced to death by being bricked in alive for their refusal to convert to Islam and abandon the Sikh faith. On 26 December 1705, Fateh Singh was killed in this manner at Sirhind along with his elder brother, Zorawar Singh. Gurdwara Fatehgarh Sahib which is situated 5 km north of Sirhind marks the site of the execution of the two younger sons of Guru Gobind Singh at the behest of Wazir Khan of Kunjpura, the Governor of Sirhind. The three shrines within this Gurdwara complex mark the exact spot where these events were witnessed in 1705.[38][39]

Jezzar Pasha, the Ottoman governor of provinces in modern Lebanon, and Palestine from 1775 to 1804, was infamous for his cruelties. When building the new walls of Beirut, he was charged with, among other things, the following:[40]

... and this monster had taken the name of Dgezar (Butcher) as an illustrious addition to his title. It was, no doubt, well deserved; for he had immured alive a great number of Greek Christians when he rebuilt the Walls of Barut..The heads of these miserable victims, which the butcher had left out, in order to enjoy their tortures, are still to be seen.

Staying as a diplomat in Persia from 1860 to 1863, E. B. Eastwick met at one time, the Sardar i Kull, or military high commander, Aziz Khan. Eastwick notes that he "did not strike me as one who would greatly err on the side of leniency". Eastwick was told that just recently, Aziz Khan had ordered 14 robbers walled up alive, two of them head-downwards.[41] Staying for the year 1887–1888 primarily in Shiraz, Edward Granville Browne noted the gloomy reminders of a particularly bloodthirsty governor there, Firza Ahmed, who in his four years of office (ending circa 1880) had caused, for example, more than 700 hands cut off for various offences. Browne continues:[42]

Besides these minor punishments, many robbers and others suffered death; not a few were walled up alive in pillars of mortar, there to perish miserably. The remains of these living tombs may still be seen outside Derwaze-i-kassah-khane ("Slaughter-house Gate") at Shiraz, while another series lines the road as it enters the little town of Abade...

Immurement was practiced in Mongolia as recently as the early 20th century. It is not clear that all thus immured were meant to die of starvation. In a newspaper report from 1914, it is written:[43]

... the prisons and dungeons of the Far Eastern country contain a number of refined Chinese shut up for life in heavy iron-bound coffins, which do not permit them to sit upright or lie down. These prisoners see daylight for only a few minutes daily when the food is thrown into their coffins through a small hole.

North Africa

[edit]In 1906, Hadj Mohammed Mesfewi, a cobbler from Marrakesh, was found guilty of murdering 36 women; the bodies were found buried underneath his shop and nearby. Due to the nature of his crimes, he was walled up alive. For two days his screams were heard incessantly before silence by the third day.[44][45][46]

Sacrificial variations

[edit]Construction

[edit]A number of cultures have tales and ballads containing as a motif the sacrifice of a human being to ensure the strength of a building. For example, there was a culture of human sacrifice in the construction of large buildings in East and Southeast Asia. Such practices ranged from da sheng zhuang (打生樁) in China to hitobashira in Japan and myosade (မြို့စတေး) in Burma.

The folklore of many Southeastern European peoples refers to immurement as the mode of death for the victim sacrificed during the completion of a construction project, such as a bridge or fortress (mostly real buildings). The Castle of Shkodra is the subject of such stories in both the Albanian oral tradition and in the Slavic one. The Albanian version is The Legend of Rozafa, in which three brothers uselessly toil at building walls which always disappear at night: when told that they must bury one of their wives in the wall, they pledge to choose the one that brings them luncheon the next day, and not to warn their respective spouses. However, two brothers secretly inform their wives (the topos of two fellows betraying one being common in Balkan poetry, cf. Miorița or the Song of Çelo Mezani), leaving Rozafa, wife of the honest brother, to die. She accepts her fate, but asks that they leave exposed a foot to rock the infant son's cradle, a breast to feed him, and a hand to stroke his hair.

One of the most famous versions of the same legend is the Serbian epic poem called The Building of Skadar (Зидање Скадра, Zidanje Skadra) published by Vuk Karadžić, after he recorded a folk song sung by a Herzegovinian storyteller named Old Rashko.[47][48][49] The version of the song in the Serbian language is the oldest collected version of the legend, and the first one which earned literary fame.[50] The three brothers in the legend were represented by members of the noble Mrnjavčević family, Vukašin, Uglješa and Gojko.[51] In 1824, Karadžić sent a copy of his folksong collection to Jacob Grimm, who was particularly enthralled by the poem. Grimm translated it into German, and described it as "one of the most touching poems of all nations and all times".[52] Johann Wolfgang von Goethe published the German translation, but did not share Grimm's opinion because he found the poem's spirit "superstitiously barbaric".[52][48] Alan Dundes, a famous folklorist, noted that Grimm's opinion prevailed and that the ballad continued to be admired by generations of folksingers and ballad scholars.[52]

A very similar Romanian legend, that of Meşterul Manole, tells of the building of the Curtea de Argeș Monastery. Ten expert masons, among them Master Manole himself, are ordered by Neagu Voda to build a beautiful monastery, but incur the same fate, and also decide to immure the wife who will bring them luncheon. Manole, working on the roof, sees her approach, and pleads in vain with God to unleash the elements in order to stop her. When she arrives, he proceeds to wall her in, pretending to be doing so in jest, while she cries out increasingly in pain and distress. When the building is finished, Neagu Voda takes away the masons' ladders, fearing they will build a more beautiful building. They try to escape, but all fall to their deaths. Only from Manole's fall a stream is created.[53]

Many other Bulgarian and Romanian folk poems and songs describe a bride offered for such purposes, and her subsequent pleas to the builders to leave her hands and breasts free, that she might still nurse her child. Later versions of the songs revise the bride's death; her fate to languish entombed within the construction is transmuted to her nonphysical shadow, and its loss yet leads to her pining away and eventual death.[54]

Other variations include the Hungarian folk ballad "Kőmíves Kelemen" (Kelemen the Stonemason). This is the story of twelve unfortunate stonemasons tasked with building the fort of Déva. To remedy its recurring collapses, it is agreed that one of the builders must sacrifice his bride, and the bride to be sacrificed will be she who first comes to visit.[55] In some versions of the ballad the victim is shown some mercy; rather than being trapped alive she is burned and only her ashes are immured.[56]

A Greek story, "The Bridge of Arta" (Greek: Γεφύρι της Άρτας), describes numerous failed attempts to build a bridge in that city. Again, a cycle wherein a team of skilled builders toils all day only to return the next morning to find their work demolished is eventually ended when the master mason's wife is immured.[57] Legend has it that a maiden was immured in the walls of Madliena church as a sacrifice or offering after continuous failed construction attempts. The pastor achieved this by inviting all of the most beautiful maidens to a feast; the most beautiful one, Madaļa, falls into a deep sleep after the pastor offers wine from "certain goblet".[58]

Ceremonial

[edit]Within Inca culture, it is reported that one element in the great Sun festival was the sacrifice of young maidens (between ten and twelve years old), who after their ceremonial duties were done were lowered down in a waterless cistern and immured alive.[59] The children of Llullaillaco represent another form of Incan child sacrifice.

Acknowledging the traditions of human sacrifice in the context of the building of structures within German and Slavic folklore, Jacob Grimm offers some examples of the sacrifice of animals as well. According to him, within Danish traditions, a lamb was immured under an erected altar in order to preserve it, while a churchyard was to be ensured protection by immuring a living horse as part of the ceremony. In the ceremonies of erection of other types of constructions, Grimm notices that other animals were sacrificed as well, such as pigs, hens and dogs.[60]

Harold Edward Bindloss, in his 1898 non-fiction In the Niger country, writes of the funeral of a great chief:

Only a few years ago, when a powerful headman died not very far from Bonny, several of his wives had their legs broken, and were buried alive with him[61]

Similarly, the 14th century traveller Ibn Batuta observed the burial of a great khan:[62]

The Khan who had been killed, with about a hundred of his relatives, was then brought, and a large sepulchre was dug for him under the earth, in which a most beautiful couch was spread, and the Khan was with his weapons laid upon it. With him they placed all the gold and silver vessels he had in his house, together with four female slaves, and six of his favourite Mamluks, with a few vessels of drink. They were then all closed up, and the earth heaped upon them to the height of a large hill.

In literature and the arts

[edit]- Opera

At the end of Verdi's opera Aida the Egyptian General Radames is found guilty of treason and is immured in a cave as punishment. Once the cave is enclosed, he discovers that his lover Aida has hidden in the cave to be with him, and they die there together.

- Literature

In Honoré de Balzac's 1831 story "La Grande Bretèche," Madame de Merret is accused by her husband of hiding a lover in her bedroom closet; she swears on a crucifix that no one is in there and threatens to leave him if he casts doubt on her character by checking. In response, her husband has the closet door sealed and plastered over, then spends the next twenty days living in his wife's room to ensure her lover cannot escape.

Edgar Allan Poe's short story "The Cask of Amontillado" involves the narrator murdering a rival by immuring him in a crypt. This story has been adapted for screen over the years

Ariana Franklin's Mistress of the Art of Death (2007) includes the execution of a nun by walling her into her cell, to circumvent the protection usually afforded by her vows.

In the 1978 novel The Three-Arched Bridge by Albanian writer Ismail Kadare, the immurement of a villager plays an important role; whether or not he volunteered or was punished remains unclear. The book also contains discussion on the background and motives of the characters in the Legend of Rozafa.

- Stage, film, and television

In the 1944 film The Canterville Ghost, Sir Simon (Charles Laughton) is immured by his father while he is hiding to avoid fighting a duel.

At the end of the 1955 movie Land of the Pharaohs, scheming Princess Nellifer (Joan Collins) is shocked to learn that she has been immured in the tomb of her husband Pharaoh Khufu (Jack Hawkins).

In "The Ikon of Elijah", a 1960 episode of Alfred Hitchcock Presents, the main character is immured in a monastic cell as penance for having killed a monk.

Poe's The Cask of Amontillado has been adapted for film and television, including a segment in Roger Corman's anthology Tales of Terror (1962) and an episode of the 2023 Netflix series The Fall of the House of Usher.

The walling-in of wayward monastics, individuals and entire cloisters alike, is common in the genre of nunsploitation; several such films draw on the historical case of the Nun of Monza in particular. Though in reality she was released from immurement after serving some 10 or 15 years, some movies dramatize her fate as one of permanent confinement.

In the 1976 Danish comedy film The Olsen Gang Sees Red the protagonist is momentarily immured in a castle dungeon next to actual immurements.

In a 1984 episode of Thomas the Tank Engine "The Sad Story of Henry[63]" the engine Henry was immured as punishment for disobeying the orders of The Fat Controller.

In a 1999 episode of Angel, "Room of a Vu", Maude Pearson immured her son Dennis.

In a 2003 episode of The Simpsons, "C.E.D'oh", Mr. Burns unsuccessfully tries to immure Homer Simpson as revenge for taking over the Springfield Nuclear Power Plant.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Definition of Immurement

- ^ Olavinlinna Legends

- ^ The Immured Lady Archived 2009-08-19 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ The immured knight Archived 2013-12-03 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Legend has it that a girl was immured in the wall of the church in a kneeling position and thus the place came to be called Põlva (the Estonian word põlv means knee in English)." Põlva linn Archived 2013-12-03 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "... is the Maiden's Tower (Jungfrutornet), in which legend has it that the daughter of a Visby goldsmith was walled up alive for betraying the town to the Danes out of love for the Danish king Valdemar Atterdag."Visby Tourist Attractions

- ^ Jansone, Una. "Grobiņas pils". Archived from the original on January 19, 2012. Retrieved November 9, 2013.

- ^ Thucydides, 3.81.5 Archived 2013-12-15 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Smith (1846), p. 353

- ^ Dowling (2001), "Vestal Virgins: Chaste keepers of the flame"

- ^ Peter Sarris opts for freezing to death, rather than death by starvation. Sarris (2011), p. 252

- ^ Evagrius (2000), p. 143, footnote 31

- ^ Procopius (2007), p. 71

- ^ Rohrbacher (2013), p. 89

- ^ Hübner (1700), p. 590

- ^ Wekebrod (1814), pp. 118–119

- ^ Dodsley (1744), p. 103. On suspicion of it being the remains of the fourteenth abbot, Thornton Abbey; and its "immured" Abbot Archived 2011-06-12 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Osenbrüggen (1860), p. 290

- ^ Carlo Ginzburg, Ecstasies, p. 43

- ^ Thorne, Tony (1997). Countess Dracula. London, England: Bloomsbury. p. 53. ISBN 978-1408833650.

- ^ Bledsaw, Rachael (20 February 2014). "No Blood in the Water: The Legal and Gender Conspiracies Against Countess Elizabeth Bathory in Historical Context". MS Thesis. doi:10.30707/ETD2014.Bledsaw.R – via Illinois State University doi:10.30707/ETD2014.Bledsaw.R.

- ^ Ferencné, Palkó (2014). "Báthory Erzsébet Pere". BA Thesis – via University of Miskolc.

- ^ O'Reilly (2000), p. 180

- ^ Gregory of Tours. A History of the Franks. Pantianos Classics, 1916

- ^ Lea (2012), p. 487

- ^ Lea (2012), footnote 444

- ^ Scott (1833), p. 392

- ^ Medioli, Schutte, Kuehn, Menchi (2001), pp. 170–171

- ^ Lerner (1986), p. 60

- ^ Kurkijan (2008), p. 17[permanent dead link]

- ^ Durkheim (2010), p. 224

- ^ On Anarkali legend and tomb, Anarkali's Tomb Archived 2022-03-18 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Hume-Griffith (1909), pp. 138–139

- ^ Tavernier, Phillips (1678), p. 233

- ^ John Fryer

- ^ Fryer (1698), p. 318

- ^ Bernier (1916), pp. 114–115

- ^ Joseph Davey Cunningham, History of the Sikhs, Published by Rupa Publications India Pvt Ltd, page 76.

- ^ "The story of Sahibzada Zorawar Singh and Sahibzada Fateh Singh". 31 December 2018.

- ^ de Tott (1786), p. 97

- ^ Eastwick (1864), p. 186

- ^ Browne (2013), pp. 117–118

- ^ New Zealand Herald (1914), p. 7

- ^ "Tempering Justice in America; Making it Cruel Abroad". The St. John. September 8, 1906. p. 13.

- ^ Zeitungsartikel (1) von 1906

- ^ Zeitungsartikel (2) von 1906

- ^ Dundes 1996, pp. 3, 146.

- ^ a b Cornis-Pope & Neubauer 2004, p. 273.

- ^ Skëndi 2007, p. 75.

- ^ Dundes 1996, p. 146.

- ^ Dundes 1996, p. 150.

- ^ a b c Dundes 1996, p. 3.

- ^ Tappe (1984), A Rumanian Ballad and its English Adaptation

- ^ Моллов, Тодор (14 August 2002). "Троица братя града градяха" (in Bulgarian). LiterNet. Retrieved 2007-05-19. Examples of Bulgarian songs: Three Brothers Were Building a Fortress recorded near Smolyan, Immured Bride recorded in Struga.

- ^ Called "Clemens" in Eliade, Dundes (1996), p. 77

- ^ On the sacrifice, with ashes immured, see for example: Mallows (2013), p. 219

- ^ Eliade, Dundes (1996), pp. 75–76

- ^ Pozemovskis, Kā cēlies Madlienas nosaukums

- ^ French (2000), p. 78

- ^ Grimm (1854), p. 1095

- ^ Bindloss (1898), p. 169

- ^ Batuta, Lee (1829), p. 220

- ^ ""Thomas & Friends" The Sad Story of Henry (TV Episode 1984)", IMDb, retrieved 2023-05-03

Bibliography

[edit]- Altekar, Anant S. (1959). The Position of Women in Hindu Civilization: From Prehistoric Times to the Present Day. Madras: Motilal Banarsidass Publ. ISBN 9788120803244.

{{cite book}}: ISBN / Date incompatibility (help) - Baltikumresan. "The immured knight". aulik.se. Baltikumresan. Archived from the original on 2013-12-03.

- ibn Batuta; Lee (1829). The Travels of Ibn Batuta. London: Oriental Translation Committee.

- Bechstein, Ludwig (1858). Thüringer sagenbuch. Coburg: C. A. Hartleben.

- Bernier, Francois (1916). Travels in the Mogul Empire, A.D. 1656–1668. London: Milford, Oxford University Press.

- Bindloss, Harold (1898). In the Niger country. Edinburgh and London: W. Blachwood and Sons.

- Brown, Harry J. (2004). Injun Joe's Ghost: The Indian Mixed-blood in American Writing. Columbia, Missouri: University of Missouri Press. ISBN 9780826262448.

- Browne, Edward G. (2013). A Year Amongst The Persians. London: Routledge. ISBN 9781136183966.

- Burian, Peter; Shapiro, Alan (2010). The Complete Sophocles: Volume I: The Theban Plays. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780199830930.

- Chmel, Joseph (1841). Der österreichische Geschichtsforscher, Volume 2. Vienna: Carl Gerold.

- Cornis-Pope, Marcel; Neubauer, John (2004). History of the Literary Cultures of East-Central Europe: Junctures and Disjunctures in the 19th and 20th Centuries. John Benjamins Publishing. ISBN 978-90-272-3455-1.

- Dowling, Melissa (2001). "Vestal Virgins – Chaste keepers of the flame". BAS Library. Biblical Archaeological Society.

- Dundes, Alan (1996). The Walled-Up Wife: A Casebook. University of Wisconsin Press. ISBN 9780299150730.

- Durkheim, Emile (2010). Suicide. Simon and Schuster. ISBN 9781439118269.

- Elliade, Mircea (1996). Dundes, Alan (ed.). The Walled-up Wife: A Casebook. Madison, Wisconsin: Univ of Wisconsin Press. ISBN 9780299150730.

- Eastwick, Edward B. (1864). Journal of a Diplomate's Three Years' Residence in Persia, Volume 1. London: Smith, Elder and Company.

- Evagrius (2000). The Ecclesiastical History of Evagrius Scholasticus. Liverpool: Liverpool University Press. ISBN 9780853236054.

- ExecutedToday.com (19 July 2019). "1762: Crown Prince Sado, locked in a rice chest". ExecutedToday.com.

- French, Marilyn (2008). From Eve to Dawn: A History of Women, Volume 1. New York: Feminist Press at CUNY. ISBN 9781558616196.

- Fryer, John (1698). A New Account of East-India and Persia, in Eight Letters: Being Nine Years Travels Begun 1672 and Finished 1681. London: Chiswell.

- Fumagalli, Maria C. (2001). The Flight of the Vernacular: Seamus Heaney, Derek Walcott and the Impress of Dante. Amsterdam: Rodopi. ISBN 9789042014763.

- Grimm, Jacob (1854). Deutsche Mythologie. [With] Anhang. Göttingen: Dieterische Buchh.

- Haapsalu. "The Immured Lady". haapsalu.ee. Haapsalu township. Archived from the original on 2009-08-19.

- Hayes, Kevin, ed. (2012). Edgar Allan Poe in Context. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9781107009974.

- Hübner, Johann (1700). Kurze Fragen aus der politischen Historia biß auf gegenwärtige Zeit, Volume 3. Gleditsch.

- Hume-Griffith, M.E. (1909). Behind the veil in Persia and Turkish Arabia; an account of an Englishwoman's eight years' residence amongst the women of the East. With narratives of experiences in both countries. Philadelphia: J. B. Lippincott & Co.

- Jansone, Una. "Grobiņas pils". pasakas.net. Archived from the original on January 19, 2012. Retrieved November 9, 2013.

- Krehbiel, Henry (2006). Book of Operas EasyRead Edition. ReadHowYouWant.com. ISBN 9781442938106.

- Kurkijan, Vahan M. (2008). A History of Armenia. New York: Indo-European Publishing. ISBN 9781604440126.

- Lea, Henry C (2012). A History of The Inquisition of The Middle Ages; volume I. Project Gutenberg.

- Lerner, Gerda (1986). The Creation of Patriarchy, Volume 1. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780195051858.

- Levy, Reuben (1957). The Social Structure of Islam: Being the Second Edition of The Sociology of Islam. Cambridge: CUP Archive. ISBN 9780521091824.

{{cite book}}: ISBN / Date incompatibility (help) - Mallows, Lucy (2013). Transylvania. Bradt Travel Guides. ISBN 9781841624198.

- Medioli, Francesca (2001). Schutte, Anna Jacobson; Kuehn, Thomas; Menchi, Silvana Seidel (eds.). Time, Space, and Women's Lives in Early Modern Europe. Kirksville, MO: Truman State University Press. ISBN 9780943549903.

- Моллов, Тодор (14 August 2002). "Троица братя града градяха" (in Bulgarian). LiterNet. Retrieved 2007-05-19.

- Muhammad Ali, Maulana (2011). Holy Quran, English Translation and Commentary. eBookIt.com. ISBN 9781934271148.

- New Zealand Herald (17 February 1914). "Immured in Coffins". New Zealand Herald. LI.

- Noor, Raza. "Anarkali's Tomb". Staff Page for Raza Noor. University of Alberta. Archived from the original on 2022-03-18. Retrieved 2017-09-01.

- O'Reilly, Sean; O'Reilly, James (2000). Pilgrimage: Adventures of the Spirit. Travelers' Tales. ISBN 9781885211569.

- Osenbrüggen, Eduard (1860). Das alamannische Strafrecht im deutschen Mittelalter. Schaffhausen: Hurter.

- Planetware. "Visby Tourist Attractions". Planetware.

- Mistérios do Mundo (12 June 2019). "A história do emparedamento, uma das formas mais cruéis de tortura e execução já inventadas". Mistérios do Mundo.

- "Põlva linn". polva.ee/tourism. Polva Tourism. Archived from the original on 2013-12-03. Retrieved 2013-12-02.

- Pozemovskis, Ēriks. "Kā cēlies Madlienas nosaukums". Archived from the original on August 31, 2009. Retrieved November 9, 2013.

- Procopius (2007). History of the Wars: Books 3–4 (Vandalic War). Cosimo, Inc. ISBN 9781602064461.

- Riepl, Ludwig. "Aus der Geschichte von Weitersfelden". weitersfelden.ooe.gv.at. Weitersfelden Government.

- Rohrbacher, David (2013). The Historians of Late Antiquity. London: Routledge. ISBN 9781134628858.

- Sarris, Peter (2011). Empires of Faith: The Fall of Rome to the Rise of Islam, 500–700. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780191620027.

- Sbornici. "Three Brothers Were Building a Fortress". liternet.bg.

- Sbornici. "Immured Bride". liternet.bg.

- Scott, Walter (1833). The Complete Works of Sir Walter Scott: With a Biography, and His Last Additions and Illustrations, Volume 1. New York: Conner & Cooke.

- Skëndi, Stavro (2007). Poezia epike gojore e shqiptarëve dhe e sllavëve të jugut. Instituti i Dialogut & Komunikimit. ISBN 9789994398201.

- Smith, Anthon (1846). A school dictionary of Greek and Roman antiquities. London: Harper.

- Tappe, Eric (1984). "A Rumanian Ballad and its English Adaptation". Folklore. 95 (1). Folklore Enterprises Ltd.: 113–119. doi:10.1080/0015587x.1984.9716302. ISSN 0015-587X. JSTOR 1259765.

- Tavernier, Jean-Baptiste; Phillips, John (1678). The six voyages of John Baptista Tavernier. London: R.L and M.P.

- Taylor, Lou (2009) [1983]. Mourning Dress (Routledge Revivals): A Costume and Social History. London: Routledge. ISBN 9780203871324.

- The St.John Sun (8 September 1906). "Walled in Alive". The St.John Sun. 30. Ruby Douglas: 13.

- Thucydides. "The Pelopennesian War 3.69–3.85:Civil War at Corcyra". The Perseus Digital Library. Tufts University. Archived from the original on 2014-03-22. Retrieved 2013-12-01.

- de Tott, Francois (1786). Memoirs of Baron de Tott: Containing the State of the Turkish Empire & the Crimea, During the Late War with Russia. With Numerous Anecdotes, Facts, & Observations, on the Manners & Customs of the Turks & Tartars, Volume 2. London: G.G.J. & J. Robinson.

- Varner, Eric R. (2004). Monumenta Graeca et Romana: Mutilation and transformation : damnatio memoriae and Roman imperial portraiture. Leiden: Brill. ISBN 9789004135772.

- Wekebrod, Franz Xaver (1814). Mährens Kirchengeschichte, Volume 1. Brünn (Brno): Traßler.

- Wilde, Oscar (1998). Murray, Isobel (ed.). Complete Shorter Fiction. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780192833761.

External links

[edit] Quotations related to Immurement at Wikiquote

Quotations related to Immurement at Wikiquote

Immurement

View on GrokipediaDefinition and Terminology

Etymology and Conceptual Scope

The term immurement originates from the Medieval Latin verb immurare, meaning "to wall in" or "to enclose within walls," formed by the prefix in- ("in") combined with murus ("wall").[7][8] The English verb immure first appeared in the late 16th century, denoting the act of shutting up or imprisoning someone behind walls, while the noun immurement emerged in the mid-18th century to describe the state or process of such enclosure.[8][9] Conceptually, immurement refers to the intentional confinement of a person within a sealed or enclosed space, typically constructed from masonry or other barriers, with death resulting from suffocation, starvation, or dehydration due to the absence of air, food, or water.[5] This practice is primarily lethal, distinguishing it from mere temporary isolation by its design to preclude survival, though non-fatal variants involve prolonged but survivable enclosure.[10] Key variations include full immurement, entailing complete sealing without escape, and partial forms where initial access exists before final closure, but both prioritize structural entrapment over restraint by non-architectural means.[11] Immurement differs from burial alive or premature interment, which entail covering the victim with earth or placing them in a grave-like pit, as it specifically employs built enclosures such as walls, chambers, or niches integrated into architecture rather than soil displacement.[11] This structural emphasis underscores immurement's reliance on constructed immobility, where the primary mechanisms of fatality—deprivation of essentials—arise from the impervious nature of the enclosing material, not compressive burial forces.[5]Purposes and Contexts

Punitive Applications

Immurement served as a form of capital punishment in certain pre-modern legal systems for offenses deemed threats to social order or moral fabric, such as violations of chastity oaths or adultery, where the method's slow lethality underscored deterrence through visible suffering. In ancient Rome, Vestal Virgins convicted of unchastity—interpreted as incestum, a sacrilege endangering the state's divine favor—faced immurement to avoid direct bloodshed, which was ritually prohibited for these priestesses. The condemned was lowered into an underground chamber stocked with minimal provisions like a lamp, bread, water, and milk, then sealed in to perish from starvation and dehydration over several days, as documented in Plutarch's accounts of cases like that of Cornelia in 90 BCE.[1][5] This punishment's rationale lay in its capacity to prolong agony, amplifying the exemplary function beyond instantaneous methods like decapitation or hanging, thereby reinforcing communal norms through public dread and moral instruction. Historical analyses of Roman penal practices indicate that the extended torment served causal deterrence, as witnesses internalized the crime's gravity via the victim's audible decline, fostering social control in hierarchical societies reliant on exemplary justice rather than codified rehabilitation.[10] Comparative records from antiquity show immurement inflicted greater physiological and psychological terror than strangulation, with death ensuing from asphyxiation, exposure, and organ failure after 3–10 days, heightening its perceived retributive justice.[5] In analogous systems, such as certain nomadic traditions, immurement targeted adultery to preserve lineage purity, entombing offenders in confined structures to mirror the offense's enduring social contamination, though empirical verification remains sparse beyond traveler accounts emphasizing deterrence over mercy. Legal codes prioritizing retributive proportionality favored this over swift execution, as the method's inevitability without escape symbolized inescapable moral reckoning, though its application waned with centralized states favoring efficient hangings for scalability.[12]Sacrificial and Ritualistic Uses

Immurement served sacrificial purposes in certain cultures as a foundational rite, wherein a living human was entombed within a structure to symbolically infuse it with life force, thereby ensuring stability against natural forces or supernatural threats. This practice stemmed from causal beliefs that the victim's vitality would "bind" the edifice, preventing collapse; such rituals predate modern engineering and reflect pre-scientific understandings of material durability tied to organic sacrifice. Archaeological instances are infrequent and interpretive, contrasting with abundant folklore where the act is mythologized as essential for prosperity or divine appeasement.[13] In the ancient Near East, potential evidence emerges from excavations at Gezer, a Bronze Age site in modern Israel. British archaeologist R.A.S. Macalister's digs from 1902 to 1909 unearthed infant skeletons positioned under foundation stones of buildings, which he documented as deliberate human sacrifices to consecrate and fortify the constructions. These findings, detailed in early 20th-century reports, included multiple such interments aligned with structural bases, though later scholars debate whether they represent ritual immurement or opportunistic use of nearby child graves amid high infant mortality rates.[14] A more unambiguous case dates to the Silla Kingdom in 6th-century Korea, where 2021 excavations at Wolseong Fortress in Gyeongju exposed the remains of a woman, aged 25-30, buried alive in a pit integrated into the fortress foundations. Forensic examination revealed no signs of disease or injury prior to entombment, with her positioned face-down in a manner inconsistent with standard burials, indicating intentional sacrificial immurement to safeguard the military structure against erosion or invasion. This discovery, from a peer-reviewed dig by the Gyeongju National Research Institute of Cultural Heritage, aligns with historical texts referencing human offerings for monumental builds in East Asian kingdoms.[15] Ceremonial variants appear in sparse records from steppe nomad traditions, including Mongolian contexts under Qing influence, where entombment in wooden enclosures occasionally featured in rites to avert communal calamities, though primary evidence ties more to punitive than purely ritual ends. Across these examples, verifiable cases underscore rarity; most attestations derive from oral traditions or secondary inferences, with no widespread empirical pattern beyond isolated sites, emphasizing the practice's marginal role amid dominant non-human foundation deposits like artifacts or animals in Near Eastern and Asian archaeology.Ascetic and Voluntary Practices

In medieval Christian Europe, anchorites—individuals, often women known as anchoresses—voluntarily enclosed themselves in small cells adjoining church walls to dedicate their lives to prayer, penance, and spiritual contemplation, viewing the act as a symbolic death to worldly existence.[16] The enclosure rite, conducted by a bishop around the 12th to 15th centuries, involved a funeral liturgy where the anchorite was sealed in with provisions for minimal sustenance, typically through narrow squints or windows allowing food delivery and limited verbal counsel to visitors.[17] This practice stemmed from eremitic traditions emphasizing isolation for union with God, as outlined in guides like the 13th-century Ancrene Wisse, which prescribed ascetic regimens including sparse meals of bread, water, and occasional fish or vegetables to sustain but weaken the body.[18] Cells measured roughly 6 by 9 feet, furnished with a bed, altar, and crucifix, designed to enforce perpetual enclosure under vows of stability, with exits bricked over post-entry.[19] Waste management relied on chamber pots emptied via servants through the apertures, mitigating but not eliminating hygiene risks in confined spaces lacking ventilation or bathing facilities.[16] Archaeological remnants, such as those at Norwich Cathedral where Julian of Norwich lived enclosed from 1373 until her death around 1416, confirm these austere setups supported long-term survival for some, though reliant on communal support.[17] Doctrinal rationales framed immurement as emulation of Christ's tomb or saintly precedents like St. Anthony, fostering mystical experiences through sensory deprivation and bodily mortification.[18] However, hagiographies often romanticize endurance, overlooking empirical realities: restricted movement induced muscle atrophy and joint degeneration, while proximity to waste and limited nutrition elevated mortality from infections, as evidenced by a 15th-century anchoress burial revealing syphilis and nutritional deficiencies.[20] Survival beyond a decade was exceptional, with many succumbing within years to disease or starvation lapses, underscoring that purported spiritual gains lacked verifiable causal links beyond subjective accounts prone to pious exaggeration.[17] Voluntary immurement appears rarer in Islamic or Eastern traditions, with Sufi practitioners favoring cave khalwa (retreats) for temporary isolation rather than permanent walling, and Buddhist ascetics pursuing extreme fasts or self-mummification (sokushinbutsu) in Japan from the 11th century, entailing gradual dehydration in lotus posture within lidded stone tombs rather than ongoing enclosure.[21] These variants prioritized enlightenment through bodily transcendence but similarly entailed high physiological tolls, including organ failure from caloric deficits exceeding 3,000 days of preparation in sokushinbutsu cases, without documented long-term viability akin to anchoritic cells.[22] Such practices, while agent-driven, reflect causal patterns where extreme isolation amplifies health deterioration absent modern interventions, challenging idealized narratives of transcendent purity.Historical Practices

In Europe

In ancient Rome, immurement was employed as a capital punishment for Vestal Virgins who broke their vow of chastity, a practice rooted in the prohibition against shedding their blood, which was believed essential to preserving the city's sacred integrity. The condemned priestess was stripped, beaten, dressed in funerary garments, and lowered into an underground chamber stocked with minimal provisions such as a lamp, bread, water, and a couch, after which the entrance was sealed with bricks, leading to death by starvation and suffocation over days or weeks. This method is attested in classical sources for roughly ten cases over the order's millennium-long existence, including the execution of three Vestals in 19 BCE under Emperor Augustus for alleged unchastity, as documented by historians like Plutarch and Dionysius of Halicarnassus.[1][23] During the medieval period, punitive immurement persisted in Christian Europe but became rarer and more localized, often tied to ecclesiastical offenses rather than widespread heresy trials, where burning predominated. A documented instance occurred in 1409 in Augsburg, Germany, where four Bavarian clerics convicted of child sexual abuse were immured alive within a church wall as a form of retribution short of direct bloodshed, reflecting symbolic entombment for sacrilegious crimes. Similar applications targeted nuns or monks who violated vows, with temporary or permanent walling in convent structures to enforce penance or execution, though such cases blend into voluntary anchorite practices and lack the volume of Roman precedents. In Eastern Europe under Ottoman administration from the 15th to 19th centuries, immurement reemerged in records as a deterrent for betrayal or dissent, particularly in fortress construction or against spies, with rulers sealing offenders into walls to invoke supernatural retribution, as noted in Balkan chronicles amid cultural exchanges with Islamic traditions. The practice waned after the Enlightenment, supplanted by codified legal systems emphasizing swift executions like hanging or the guillotine, amid broader shifts toward humanitarian reforms in penal philosophy across Europe. By the 18th and 19th centuries, verifiable cases dwindled, confined to isolated fortifications or peripheral regions, with no systematic application in major states; potential late instances, such as rumored entombments in military walls during conflicts, remain anecdotal rather than evidentially robust.[24]In Asia and the Middle East

In historical Persia under the Qajar dynasty, immurement served as a punitive measure for criminals, with individuals sealed alive into brick pillars or walls to perish from starvation and dehydration. A documented instance occurred during the reign of Naser al-Din Shah (r. 1848–1896), when the governor Lutf 'Ali Khan ordered several offenders walled up in pillars along the road at Abadeh as a deterrent.[25] Such practices, reported by contemporary observers like medical officer C.J. Wills, deviated from standard Islamic hudud penalties—such as stoning for adultery derived from certain hadith—yet persisted regionally despite jurisprudential prohibitions on excessive cruelty, which emphasized measured retribution to avoid disproportionate suffering.[25] In ancient China, immurement featured prominently in funerary rituals as human sacrifice, where attendants were buried alive with deceased rulers to serve in the afterlife. During the Shang dynasty (c. 1600–1046 BCE), excavations at sites like Houjiazhuang in Yinxu uncovered 164 skeletons likely immured to accompany kings, corroborated by oracle bone inscriptions detailing sacrificial killings.[26] This extended into the Zhou (1046–256 BCE) and Qin (221–206 BCE) periods; for instance, Qin Shi Huang's mausoleum complex reportedly involved thousands of concubines and workers entombed alive, as recorded in Sima Qian's Records of the Grand Historian, though the scale reflects elite excess later condemned and progressively banned starting with Han emperors like Wu (r. 141–87 BCE).[26] Practices lingered sporadically into the Ming (1368–1644) and early Qing (1644–1912) dynasties before formal prohibitions, such as Emperor Yingzong's 1464 edict.[26] Among Mongolian communities under Manchu Qing influence, immurement functioned as execution for offenses like adultery, entailing confinement in sealed wooden crates abandoned in remote areas to ensure death by exposure and privation. A photographed case from July 1913 depicts a woman thus punished in the Gobi Desert, reaching from a porthole in her crate; initial provisions of water were provided but not replenished, extending torment as she begged from rare passersby.[27] This method, documented by photographer Stéphane Passet for Albert Kahn's Archives of the Planet, reflected enduring nomadic traditions of isolation-based capital punishment into the early 20th century.[27]In North Africa and Other Regions

In North Africa, immurement served as a rare but documented form of capital punishment during the early 20th century under Moroccan authority. On June 11, 1906, Hadj Mohammed Mesfewi, a Marrakesh cobbler convicted of murdering at least 36 women by drugging and dismembering them for profit, was subjected to public immurement following daily whippings. Sealed alive into a narrow niche in a city wall with minimal provisions, Mesfewi succumbed to dehydration and starvation on June 13, 1906, exemplifying the practice's intent to prolong suffering through confinement.[28][10] Archaeological inferences from ancient Egyptian contexts suggest possible links to protective or funerary rituals, but these diverge from strict immurement. Early dynastic retainer sacrifices (ca. 3100–2900 BCE) involved interring servants in subsidiary graves near pharaohs' tombs, yet examinations of remains indicate prior dispatch via strangulation, poisoning, or blunt trauma rather than live entombment in walls to die gradually.[29] Such practices, evidenced at sites like Abydos, prioritized accompaniment in the afterlife over punitive enclosure, with no skeletal or textual confirmation of victims sealed alive in architectural features. Berber tomb traditions in the region, including rock-cut hypogea, similarly emphasize post-mortem burial for ancestral veneration, lacking empirical traces of live immurement despite occasional ethnographic reports of ritual confinement that remain unverified by excavation.[30] Beyond North Africa, verifiable instances in sub-Saharan or Mesoamerican settings are absent, with scattered colonial-era accounts often conflating immurement with distinct rites like ordeal burials or cenote sacrifices. In Mesoamerica, Aztec and Maya evidence points to ritual dismemberment or defenestration, not walling alive, as confirmed by osteological analyses at sites such as Templo Mayor, where victims show perimortem trauma inconsistent with prolonged enclosure. Sub-Saharan ethnographic data, drawn from cross-cultural anthropology, describe analogous punishments like pit confinement among certain groups, but these lack the structural sealing characteristic of immurement and are typically lethal through exposure rather than entombment, with no corroborated archaeological parallels. Global outliers, including purported Native American enclosure rites or Polynesian taboos, rely on unrigorous folklore interpretations critiqued for evidential weakness in peer-reviewed syntheses.[31]Methods and Physiological Realities

Execution Techniques

Immurement generally employed readily available construction materials such as bricks, stones, or wooden enclosures reinforced with mortar or earth to create a confined space integrated into a wall, foundation, or separate chamber. The enclosure was typically narrow, sized to restrict movement and fitted to the victim's body dimensions, often requiring them to stand upright, sit, or crouch to align with structural elements like niches or voids prepared in advance. In punitive applications, the space was deliberately tight to heighten physical constraint, while ritualistic variants might incorporate slightly larger voids within building foundations to symbolize incorporation into the edifice.[32][10] The procedure commenced with positioning the victim within the designated space, sometimes after binding limbs or clothing to immobilize resistance and ensure proper alignment against the enclosing surfaces. Executioners then sealed the enclosure progressively, laying courses of bricks or stones from the lower extremities upward or from the periphery inward, applying wet mortar between materials to bind and airtight seal gaps, thereby methodically eliminating avenues of escape as the aperture diminished. This sequential closure, documented in historical punitive accounts, allowed oversight to confirm containment before finalizing the structure, with tools like trowels and levels used for precision in load-bearing contexts.[5][33] Variations in technique aligned with intent: punitive immurements prioritized rapid isolation in minimal-volume spaces without structural integration, often in pre-existing walls or ad hoc barriers, to enforce solitary confinement unto death; sacrificial uses, conversely, embedded the victim during active construction—such as in bridge piers or fortress bases—employing looser initial sealing to facilitate symbolic "living foundation" roles before full entombment. Provisions like minimal rations (e.g., bread or water) were occasionally inserted prior to sealing in punitive cases to extend conscious suffering, distinguishing from immediate lethality in rituals where entombment signified perpetual guardianship rather than torment.[13][34]Effects on the Victim

The primary physiological effect on victims of immurement is asphyxiation resulting from oxygen depletion and carbon dioxide accumulation in the enclosed space. In a confined volume with limited initial air—typically equivalent to a few cubic meters or less—the human body consumes approximately 0.25-0.5 liters of oxygen per minute at rest, leading to critically low oxygen levels (below 10-15%) within 1-6 hours, depending on the exact enclosure size and victim's activity level. Hypercapnia from CO2 buildup exacerbates this, causing respiratory acidosis, rapid breathing, headache, dizziness, and eventual unconsciousness followed by cardiac arrest.[35][36] If the enclosure allows minimal air exchange or a larger initial air pocket, asphyxiation may be delayed, shifting the terminal cause to dehydration (survival limited to 3-5 days without water intake) or starvation (potentially weeks), though panic-induced exertion accelerates oxygen use and metabolic demands, shortening the timeline. Victims often succumb to positional asphyxia if restrained in awkward postures, where body weight compresses the chest or diaphragm, preventing adequate ventilation even with available air. Historical medical analogies from accidental entombments, such as coal mine entrapments, confirm that survival rarely exceeds 24-48 hours in near-sealed voids without rescue.[37][38] Psychologically, immurement induces acute claustrophobia and terror, triggering sympathetic nervous system overactivation with elevated heart rate and hyperventilation, which further depletes oxygen and hastens physical collapse. Prolonged awareness in darkness and isolation leads to sensory deprivation effects, including auditory and visual hallucinations, disorientation, and severe anxiety akin to extreme solitary confinement cases, where inmates report perceptual distortions after hours. Analogous experiments in simulated confinement demonstrate that such stressors cause cortisol surges and potential dissociative states, compounding the victim's distress until hypoxia impairs cognition.[39][40] Forensic examination of rare exhumed immurement victims reveals post-mortem indicators such as petechial hemorrhages in the lungs from asphyxia, skeletal trauma from futile escape attempts (e.g., fractured phalanges or ribs), and desiccated tissues consistent with prolonged hypovolemia rather than rapid putrefaction. In one documented homicidal burial case analyzed via post-mortem computed tomography, airway occlusion by sediment and hypoxic brain changes were evident, mirroring expected immurement pathologies. Archaeological recoveries occasionally show victims in fetal positions with no decomposition escape artifacts, supporting death by gradual suffocation over violence.[37][41]Empirical Evidence and Verification

Archaeological Discoveries

Archaeological evidence for immurement remains exceedingly rare, with verified skeletal finds typically limited to isolated cases embedded in foundations or walls, where positioning and trauma analysis suggest ritual or sacrificial intent rather than widespread punitive practice. Distinguishing live entombment from post-mortem burial proves challenging, as decomposition obscures signs of prolonged suffocation, and most remains exhibit perimortem violence indicative of prior execution. For instance, in 2020 excavations at 11th-century Břeclav Castle in the Czech Republic, three skeletons—two adults and one juvenile—were discovered directly within the stone foundations, aligned parallel to the structure's base in postures compatible with foundation sacrifice rituals, though radiocarbon dating and osteological review confirmed death by blunt force trauma prior to placement rather than enclosure-induced asphyxiation.[42][43] Potential Bronze Age examples are even more equivocal, often conflated with tomb accompaniments rather than structural immurement; no skeletal assemblages from this era have been forensically linked to live walling, with foundation deposits more commonly featuring animal remains or disarticulated bones from earlier graves repurposed for symbolic stability. Claims of human immurement in early fortifications, such as those inferred from scattered European sites, lack corroboration from systematic excavation, as isotopic and trauma studies prioritize evidence of ritual killing over confinement.[44] Post-2000 forensic applications, including CT scanning and trace element analysis of remains from medieval European structures, have debunked interpretive overreach in folklore-driven myths, such as mass immurement of nuns, revealing no osteological clusters supporting enclosed live burials and instead attributing isolated wall finds to secondary interments or structural collapses. A 1912 discovery of a single skeleton within a Romanian monastery wall was preliminarily viewed as sacrificial but yielded no verifiable indicators of vitality at enclosure upon re-examination. Similarly, a 2025 wall collapse in a 15th-century Portuguese church exposed at least 12 skeletons, prompting ongoing analysis that preliminary reports attribute to charnel reuse rather than deliberate immurement, underscoring the prevalence of incidental over intentional entombments in historical architecture.[45][46]Documentary and Eyewitness Accounts

Ancient Roman sources document immurement as a prescribed punishment for Vestal Virgins convicted of violating chastity vows, enacted to avoid shedding sacred blood within city limits or formal burial. The procedure, detailed by historian Dionysius of Halicarnassus in his Roman Antiquities (ca. 20 BCE), involved transporting the offender to a subterranean cell provisioned with minimal sustenance—a lamp, bed, bread, water, and milk—before sealing the entrance with bricks, ensuring death by gradual suffocation and starvation over days.[10] This method underscored ritual purity, with the Pontifex Maximus overseeing the rite, as corroborated in multiple classical texts emphasizing legal and religious rationales.[47] In Persian traditions, primary traveler accounts from the 17th century, such as those by gem merchant Jean Baptiste Tavernier, describe immurement of thieves by encasing them in stone pillars, limbs protruding as warnings, a practice persisting into the 19th and early 20th centuries for robbers.[10] These reports, while firsthand, warrant scrutiny for European observers' tendencies to sensationalize exotic punishments, though cross-referenced chronicles confirm its use for deterrence without direct judicial records specifying dates or trials. European medieval trial records rarely detail immurement explicitly, suggesting it was an exceptional penalty reserved for ecclesiastical crimes like heresy or sacrilege rather than secular law, with sparse documentation possibly reflecting underreporting or conflation with voluntary anchorite enclosures.[5] Eyewitness photographic evidence from early 20th-century Asia includes a 1913 image by French photographer Stéphane Passet capturing a Mongolian woman confined in a wooden crate in the desert, sentenced to starve for adultery—a variant of immurement emphasizing isolation and deprivation.[27] In North Africa, the 1906 trial of serial killer Hadj Mohammed Mesfewi in Marrakesh provides a verified punitive case: convicted on May 2 of murdering at least 36 women, he endured public whippings before immurement on June 11 in a niche, perishing June 13 amid documented crowd observations and newspaper illustrations.[48] Such accounts, drawn from contemporary judicial proceedings and visual records, offer higher reliability than anecdotal traveler tales, yet gaps persist in oral-dominant cultures where practices evaded literacy, potentially inflating folklore for propagandistic emphasis on severity.[4] Cross-verification reveals biases in Western reports, prioritizing empirical consistency over unconfirmed embellishments.Cultural and Symbolic Representations

In Literature and Folklore

Immurement features prominently in folklore as a motif of foundation sacrifices, where a living individual, typically a woman, is entombed in a structure's base to secure its stability against supernatural forces. The ancient ballad "The Walled-Up Wife," dating back at least 1,000 years, narrates a woman voluntarily or coercively immured during construction to avert collapse, serving as a metaphorical critique of marital entrapment while echoing rare historical rituals.[49] Similar narratives appear in Balkan and Western Himalayan traditions, such as tales of women sealed into bridge or waterway foundations, blending potential kernels of pre-modern building superstitions with amplified mythic elements of heroic self-sacrifice or ghostly retribution.[50][51] These stories posit immured victims as protective spirits, yet lack empirical evidence for any causal mechanism beyond psychological placebo effects in superstitious builders. European folklore abounds with legends of walled-up nuns, punished for breaking vows or illicit affairs, whose restless spirits haunt convents or ruins. One recurrent tale involves Constance de Beverley, a nun at Whitby Abbey in England, immured alive around 1100 for an affair with a sailor, manifesting as apparitions in the abbey's remnants.[52] Comparable accounts, like those at Chicksands Priory or Borley Rectory, recycle this archetype, often investigated skeptically as unsubstantiated ghost lore derived from architectural anomalies or oral embellishments rather than verified entombments.[53][54] Such motifs mythologize sporadic ecclesiastical punishments—documented in medieval canon law for grave sins—but exaggerate them into spectral guardians or vengeful entities without physiological or archaeological corroboration for supernatural outcomes.[55] In literature, particularly Gothic fiction, immurement symbolizes existential confinement and retributive justice, drawing from folkloric roots but amplifying psychological horror. Edgar Allan Poe's "The Cask of Amontillado" (1846) depicts the narrator Montresor chaining and bricking up rival Fortunato in a catacomb niche during Carnival, reveling in the victim's futile pleas as mortar sets, a motif extending Poe's explorations of repressed perversity and live burial phobia in tales like "The Black Cat."[56] This narrative reflects 19th-century taphephobia—fear of premature interment—fueled by medical reports of catalepsy misdiagnosed as death, though Poe's version prioritizes vengeful enclosure over folkloric sacrifice, critiquing human denial of innate destructiveness without endorsing occult efficacy.[57] Later works, influenced by these traditions, perpetuate immurement as a trope of societal dread toward isolation, distinct from historical verifiability yet rooted in exaggerated accounts of punitive walling.In Visual Arts and Modern Media

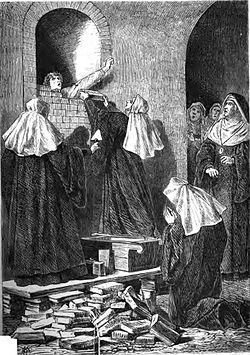

Depictions of immurement in visual arts often reflect its dual historical roles as punitive measure and ascetic practice. In medieval contexts, voluntary immurement of anchorites—individuals enclosed alive in cells for religious devotion—was portrayed in hagiographic illustrations as a symbol of spiritual piety and separation from worldly concerns, though surviving examples in frescoes or icons remain sparse due to the practice's emphasis on seclusion over visual commemoration.[16] Nineteenth-century romantic art shifted toward dramatic representations of involuntary immurement, emphasizing horror and tragedy. Austrian artist Vinzenz Katzler's 1868 lithograph Die eingemauerte Nonne illustrates a nun being walled up as punishment for transgression, capturing the moment of enclosure with figures laboring to seal the niche, thereby evoking themes of betrayal and eternal confinement drawn from folklore.[58] In modern media, particularly horror films and television from the late twentieth century onward, immurement serves as a motif for psychological terror and isolation, often stripped of historical or ritualistic context to heighten brutality. The 2009 film Walled In, directed by Bastien Boucheron, features serial immurement in an apartment building, where victims are entombed alive to appease structural curses, portraying the act through claustrophobic visuals of bricking and suffocation.[59] Similarly, the 2018 horror film The Nun includes scenes of live entombment akin to immurement, with a priest buried in a wall, underscoring supernatural dread over punitive rationale.[60] These portrayals prioritize visceral fear, evolving from symbolic piety to exploit the method's inherent slow asphyxiation and sensory deprivation for narrative tension.[61] Contemporary short films further explore immurement experimentally; the 2021 horror short Immure depicts a man confronting the consequences of entombing his mother to sustain her life, using confined framing to simulate entrapment without glorifying violence.[62] Such works occasionally incorporate forensic-inspired simulations to convey physiological realities, like gradual oxygen depletion, aiding educational insights into historical executions while avoiding gratuitous sensationalism.[63]References

- https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Die_eingemauerte_Nonne.jpg