Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Rule of inference

View on Wikipedia

Rules of inference are ways of deriving conclusions from premises. They are integral parts of formal logic, serving as norms of the logical structure of valid arguments. If an argument with true premises follows a rule of inference then the conclusion cannot be false. Modus ponens, an influential rule of inference, connects two premises of the form "if then " and "" to the conclusion "", as in the argument "If it rains, then the ground is wet. It rains. Therefore, the ground is wet." There are many other rules of inference for different patterns of valid arguments, such as modus tollens, disjunctive syllogism, constructive dilemma, and existential generalization.

Rules of inference include rules of implication, which operate only in one direction from premises to conclusions, and rules of replacement, which state that two expressions are equivalent and can be freely swapped. Rules of inference contrast with formal fallacies—invalid argument forms involving logical errors.

Rules of inference belong to logical systems, and distinct logical systems use different rules of inference. Propositional logic examines the inferential patterns of simple and compound propositions. First-order logic extends propositional logic by articulating the internal structure of propositions. It introduces new rules of inference governing how this internal structure affects valid arguments. Modal logics explore concepts like possibility and necessity, examining the inferential structure of these concepts. Intuitionistic, paraconsistent, and many-valued logics propose alternative inferential patterns that differ from the traditionally dominant approach associated with classical logic. Various formalisms are used to express logical systems. Some employ many intuitive rules of inference to reflect how people naturally reason while others provide minimalistic frameworks to represent foundational principles without redundancy.

Rules of inference are relevant to many areas, such as proofs in mathematics and automated reasoning in computer science. Their conceptual and psychological underpinnings are studied by philosophers of logic and cognitive psychologists.

Definition

[edit]A rule of inference is a way of drawing a conclusion from a set of premises.[1] Also called inference rule and transformation rule,[2] it is a norm of correct inferences that can be used to guide reasoning, justify conclusions, and criticize arguments. As part of deductive logic, rules of inference are argument forms that preserve the truth of the premises, meaning that the conclusion is always true if the premises are true.[a] An inference is deductively correct or valid if it follows a valid rule of inference. Whether this is the case depends only on the form or syntactical structure of the premises and the conclusion. As a result, the actual content or concrete meaning of the statements does not affect validity. For instance, modus ponens is a rule of inference that connects two premises of the form "if then " and "" to the conclusion "", where and stand for statements. Any argument with this form is valid, independent of the specific meanings of and , such as the argument "If it rains, then the ground is wet. It rains. Therefore, the ground is wet". In addition to modus ponens, there are many other rules of inference, such as modus tollens, disjunctive syllogism, hypothetical syllogism, constructive dilemma, and destructive dilemma.[4]

There are different formats to represent rules of inference. A common approach is to use a new line for each premise and separate the premises from the conclusion using a horizontal line. With this format, modus ponens is written as:[5][b]

Some logicians employ the therefore sign () together or instead of the horizontal line to indicate where the conclusion begins.[7] The sequent notation, a different approach, uses a single line in which the premises are separated by commas and connected to the conclusion with the turnstile symbol (), as in .[8] The letters and in these formulas are so-called metavariables: they stand for any simple or compound proposition.[9]

Rules of inference belong to logical systems and distinct logical systems may use different rules of inference. For example, universal instantiation is a rule of inference in the system of first-order logic but not in propositional logic.[10] Rules of inference play a central role in proofs as explicit procedures for arriving at a new line of a proof based on the preceding lines. Proofs involve a series of inferential steps and often use various rules of inference to establish the theorem they intend to demonstrate.[11] Rules of inference are definitory rules—rules about which inferences are allowed. They contrast with strategic rules, which govern the inferential steps needed to prove a certain theorem from a specific set of premises. Mastering definitory rules by itself is not sufficient for effective reasoning since they provide little guidance on how to reach the intended conclusion.[12] As standards or procedures governing the transformation of symbolic expressions, rules of inference are similar to mathematical functions taking premises as input and producing a conclusion as output. According to one interpretation, rules of inference are inherent in logical operators[c] found in statements, making the meaning and function of these operators explicit without adding any additional information.[14]

Logicians distinguish two types of rules of inference: rules of implication and rules of replacement.[d] Rules of implication, like modus ponens, operate only in one direction, meaning that the conclusion can be deduced from the premises but the premises cannot be deduced from the conclusion. Rules of replacement, by contrast, operate in both directions, stating that two expressions are equivalent and can be freely replaced with each other. In classical logic, for example, a proposition () is equivalent to the negation[e] of its negation ().[f] As a result, one can infer one from the other in either direction, making it a rule of replacement. Other rules of replacement include De Morgan's laws as well as the commutative and associative properties of conjunction and disjunction. While rules of implication apply only to complete statements, rules of replacement can be applied to any part of a compound statement.[19]

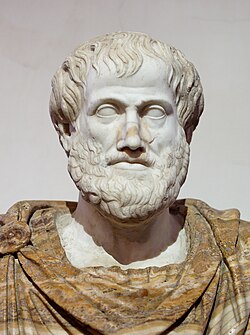

One of the earliest discussions of formal rules of inference is found in antiquity in Aristotle's logic. His explanations of valid and invalid syllogisms were further refined in medieval and early modern philosophy. The development of symbolic logic in the 19th century led to the formulation of many additional rules of inference belonging to classical propositional and first-order logic. In the 20th and 21st centuries, logicians developed various non-classical systems of logic with alternative rules of inference.[20]

Basic concepts

[edit]Rules of inference describe the structure of arguments, which consist of premises that support a conclusion.[21] Premises and conclusions are statements or propositions about what is true. For instance, the assertion "The door is open." is a statement that is either true or false, while the question "Is the door open?" and the command "Open the door!" are not statements and have no truth value.[22] An inference is a step of reasoning from premises to a conclusion while an argument is the outward expression of an inference.[23]

Logic is the study of correct reasoning and examines how to distinguish good from bad arguments.[24] Deductive logic is the branch of logic that investigates the strongest arguments, called deductively valid arguments, for which the conclusion cannot be false if all the premises are true. This is expressed by saying that the conclusion is a logical consequence of the premises. Rules of inference belong to deductive logic and describe argument forms that fulfill this requirement.[25] In order to precisely assess whether an argument follows a rule of inference, logicians use formal languages to express statements in a rigorous manner, similar to mathematical formulas.[26] They combine formal languages with rules of inference to construct formal systems—frameworks for formulating propositions and drawing conclusions.[g] Different formal systems may employ different formal languages or different rules of inference.[28] The basic rules of inference within a formal system can often be expanded by introducing new rules of inference, known as admissible rules. Admissible rules do not change which arguments in a formal system are valid but can simplify proofs. If an admissible rule can be expressed through a combination of the system's basic rules, it is called a derived or derivable rule.[29] Statements that can be deduced in a formal system are called theorems of this formal system.[30] Widely-used systems of logic include propositional logic, first-order logic, and modal logic.[31]

Rules of inference only ensure that the conclusion is true if the premises are true. An argument with false premises can still be valid, but its conclusion could be false. For example, the argument "If pigs can fly, then the sky is purple. Pigs can fly. Therefore, the sky is purple." is valid because it follows modus ponens, even though it contains false premises. A valid argument is called a sound argument if all of its premises are true.[32]

Rules of inference are closely related to tautologies. In logic, a tautology is a statement that is true only because of the logical vocabulary it uses, independent of the meanings of its non-logical vocabulary. For example, the statement "if the tree is green and the sky is blue then the tree is green" is true independently of the meanings of terms like tree and green, making it a tautology. Every argument following a rule of inference can be transformed into a tautology. This is achieved by forming a conjunction (and) of all premises and connecting it through implication (if ... then ...) to the conclusion, thereby combining all the individual statements of the argument into a single statement. For example, the valid argument "The tree is green and the sky is blue. Therefore, the tree is green." can be transformed into the tautology "if the tree is green and the sky is blue then the tree is green".[33] Rules of inference are also closely related to laws of thought, which are basic principles of logic that can take the form tautologies. For example, the law of identity asserts that each entity is identical to itself. Other traditional laws of thought include the law of non-contradiction and the law of excluded middle.[34]

Rules of inference are not the only way to demonstrate that an argument is valid. Alternative methods include the use of truth tables, which applies to propositional logic, and truth trees, which can also be employed in first-order logic.[35]

Systems of logic

[edit]Classical

[edit]Propositional logic

[edit]Propositional logic examines the inferential patterns of simple and compound propositions. It uses letters, such as and , to represent simple propositions. Compound propositions are formed by modifying or combining simple propositions with logical operators, such as (not), (and), (or), and (if ... then ...). For example, if stands for the statement "it is raining" and stands for the statement "the streets are wet", then expresses "it is not raining" and expresses "if it is raining then the streets are wet". These logical operators are truth-functional, meaning that the truth value of a compound proposition depends only on the truth values of the simple propositions composing it. For instance, the compound proposition is only true if both and are true; in all other cases, it is false. Propositional logic is not concerned with the concrete meaning of propositions other than their truth values.[36] Key rules of inference in propositional logic are modus ponens, modus tollens, hypothetical syllogism, disjunctive syllogism, and double negation elimination. Further rules include conjunction introduction, conjunction elimination, disjunction introduction, disjunction elimination, constructive dilemma, destructive dilemma, absorption, and De Morgan's laws.[37]

| Rule of inference | Form | Example |

|---|---|---|

| Modus ponens | ||

| Modus tollens | ||

| Hypothetical syllogism | ||

| Disjunctive syllogism | ||

| Double negation elimination |

First-order logic

[edit]

First-order logic also employs the logical operators from propositional logic but includes additional devices to articulate the internal structure of propositions. Basic propositions in first-order logic consist of a predicate, symbolized with uppercase letters like and , which is applied to singular terms, symbolized with lowercase letters like and . For example, if stands for "Aristotle" and stands for "is a philosopher", the formula means that "Aristotle is a philosopher". Another innovation of first-order logic is the use of the quantifiers and , which express that a predicate applies to some or all individuals. For instance, the formula expresses that philosophers exist while expresses that everyone is a philosopher. The rules of inference from propositional logic are also valid in first-order logic.[40] Additionally, first-order logic introduces new rules of inference that govern the role of singular terms, predicates, and quantifiers in arguments. Key rules of inference are universal instantiation and existential generalization. Other rules of inference include universal generalization and existential instantiation.[41]

| Rule of inference | Form | Example |

|---|---|---|

| Universal instantiation | [h] | |

| Existential generalization |

Modal logics

[edit]Modal logics are formal systems that extend propositional logic and first-order logic with additional logical operators. Alethic modal logic introduces the operator to express that something is possible and the operator to express that something is necessary. For example, if the means that "Parvati works", then means that "It is possible that Parvati works" while means that "It is necessary that Parvati works". These two operators are related by a rule of replacement stating that is equivalent to . In other words: if something is necessarily true then it is not possible that it is not true. Further rules of inference include the necessitation rule, which asserts that a statement is necessarily true if it is provable in a formal system without any additional premises, and the distribution axiom, which allows one to derive from . These rules of inference belong to system K, a weak form of modal logic with only the most basic rules of inference. Many formal systems of alethic modal logic include additional rules of inference, such as system T, which allows one to deduce from .[42]

Non-alethic systems of modal logic introduce operators that behave like and in alethic modal logic, following similar rules of inference but with different meanings. Deontic logic is one type of non-alethic logic. It uses the operator to express that an action is permitted and the operator to express that an action is required, where behaves similarly to and behaves similarly to . For instance, the rule of replacement in alethic modal logic asserting that is equivalent to also applies to deontic logic. As a result, one can deduce from (e.g. Quinn has an obligation to help) that (e.g. Quinn is not permitted not to help).[43] Other systems of modal logic include temporal modal logic, which has operators for what is always or sometimes the case, as well as doxastic and epistemic modal logics, which have operators for what people believe and know.[44]

Others

[edit]

Many other systems of logic have been proposed. One of the earliest systems is Aristotelian logic, according to which each statement is made up of two terms, a subject and a predicate, connected by a copula. For example, the statement "all humans are mortal" has the subject "all humans", the predicate "mortal", and the copula "is". All rules of inference in Aristotelian logic have the form of syllogisms, which consist of two premises and a conclusion. For instance, the Barbara rule of inference describes the validity of arguments of the form "All men are mortal. All Greeks are men. Therefore, all Greeks are mortal."[46]

Second-order logic extends first-order logic by allowing quantifiers to apply to predicates in addition to singular terms. For example, to express that the individuals Adam () and Bianca () share a property, one can use the formula .[47] Second-order logic also comes with new rules of inference.[i] For instance, one can infer (Adam is a philosopher) from (every property applies to Adam).[49]

Intuitionistic logic is a non-classical variant of propositional and first-order logic. It shares with them many rules of inference, such as modus ponens, but excludes certain rules. For example, in classical logic, one can infer from using the rule of double negation elimination. However, in intuitionistic logic, this inference is invalid. As a result, every theorem that can be deduced in intuitionistic logic can also be deduced in classical logic, but some theorems provable in classical logic cannot be proven in intuitionistic logic.[50]

Paraconsistent logics revise classical logic to allow the existence of contradictions. In logic, a contradiction happens if the same proposition is both affirmed and denied, meaning that a formal system contains both and as theorems. Classical logic prohibits contradictions because classical rules of inference bring with them the principle of explosion, an admissible rule of inference that makes it possible to infer from the premises and . Since is unrelated to , any arbitrary statement can be deduced from a contradiction, making the affected systems useless for deciding what is true and false.[51][j] Paraconsistent logics solve this problem by modifying the rules of inference in such a way that the principle of explosion is not an admissible rule of inference. As a result, it is possible to reason about inconsistent information without deriving absurd conclusions.[53]

Many-valued logics modify classical logic by introducing additional truth values. In classical logic, a proposition is either true or false with nothing in between. In many-valued logics, some propositions are neither true nor false. Kleene logic, for example, is a three-valued logic that introduces the additional truth value undefined to describe situations where information is incomplete or uncertain.[54] Many-valued logics have adjusted rules of inference to accommodate the additional truth values. For instance, the classical rule of replacement stating that is equivalent to is invalid in many three-valued systems.[55]

Formalisms

[edit]Various formalisms or proof systems have been suggested as distinct ways of codifying reasoning and demonstrating the validity of arguments. Unlike different systems of logic, these formalisms do not impact what can be proven; they only influence how proofs are formulated. Influential frameworks include natural deduction systems, Hilbert systems, and sequent calculi.[56]

Natural deduction systems aim to reflect how people naturally reason by introducing many intuitive rules of inference to make logical derivations more accessible. They break complex arguments into simple steps, often using subproofs based on temporary premises. The rules of inference in natural deduction target specific logical operators, governing how an operator can be added with introduction rules or removed with elimination rules. For example, the rule of conjunction introduction asserts that one can infer from the premises and , thereby producing a conclusion with the conjunction operator from premises that do not contain it. Conversely, the rule of conjunction elimination asserts that one can infer from , thereby producing a conclusion that no longer includes the conjunction operator. Similar rules of inference are disjunction introduction and elimination, implication introduction and elimination, negation introduction and elimination, and biconditional introduction and elimination. As a result, systems of natural deduction usually include many rules of inference.[57][k]

Hilbert systems, by contrast, aim to provide a minimal and efficient framework of logical reasoning by including as few rules of inference as possible. Many Hilbert systems only have modus ponens as the sole rule of inference. To ensure that all theorems can be deduced from this minimal foundation, they introduce axiom schemes.[59] An axiom scheme is a template to create axioms or true statements. It uses metavariables, which are placeholders that can be replaced by specific terms or formulas to generate an infinite number of true statements.[60] For example, propositional logic can be defined with the following three axiom schemes: (1) , (2) , and (3) .[61] To formulate proofs, logicians create new statements from axiom schemes and then apply modus ponens to these statements to derive conclusions. Compared to natural deduction, this procedure tends to be less intuitive since its heavy reliance on symbolic manipulation can obscure the underlying logical reasoning.[62]

Sequent calculi, another approach, introduce sequents as formal representations of arguments. A sequent has the form , where and stand for propositions. Sequents are conditional assertions stating that at least one is true if all are true. Rules of inference operate on sequents to produce additional sequents. Sequent calculi define two rules of inference for each logical operator: one to introduce it on the left side of a sequent and another to introduce it on the right side. For example, through the rule for introducing the operator on the left side, one can infer from . The cut rule, an additional rule of inference, makes it possible to simplify sequents by removing certain propositions.[63]

Formal fallacies

[edit]While rules of inference describe valid patterns of deductive reasoning, formal fallacies are invalid argument forms that involve logical errors. The premises of a formal fallacy do not properly support its conclusion: the conclusion can be false even if all premises are true. Formal fallacies often mimic the structure of valid rules of inference and can thereby mislead people into unknowingly committing them and accepting their conclusions.[64]

The formal fallacy of affirming the consequent concludes from the premises and , as in the argument "If Leo is a cat, then Leo is an animal. Leo is an animal. Therefore, Leo is a cat." This fallacy resembles valid inferences following modus ponens, with the key difference that the fallacy swaps the second premise and the conclusion.[65] The formal fallacy of denying the antecedent concludes from the premises and , as in the argument "If Laya saw the movie, then Laya had fun. Laya did not see the movie. Therefore, Laya did not have fun." This fallacy resembles valid inferences following modus tollens, with the key difference that the fallacy swaps the second premise and the conclusion.[66] Other formal fallacies include affirming a disjunct, the existential fallacy, and the fallacy of the undistributed middle.[67]

In various fields

[edit]Rules of inference are relevant to many fields, especially the formal sciences, such as mathematics and computer science, where they are used to prove theorems.[68] Mathematical proofs often start with a set of axioms to describe the logical relationships between mathematical constructs. To establish theorems, mathematicians apply rules of inference to these axioms, aiming to demonstrate that the theorems are logical consequences.[69] Mathematical logic, a subfield of mathematics and logic, uses mathematical methods and frameworks to study rules of inference and other logical concepts.[70]

Computer science also relies on deductive reasoning, employing rules of inference to establish theorems and validate algorithms.[71] Logic programming frameworks, such as Prolog, allow developers to represent knowledge and use computation to draw inferences and solve problems.[72] These frameworks often include an automated theorem prover, a program that uses rules of inference to generate or verify proofs automatically.[73] Expert systems utilize automated reasoning to simulate the decision-making processes of human experts in specific fields, such as medical diagnosis, and assist in complex problem-solving tasks. They have a knowledge base to represent the facts and rules of the field and use an inference engine to extract relevant information and respond to user queries.[74]

Rules of inference are central to the philosophy of logic regarding the contrast between deductive-theoretic and model-theoretic conceptions of logical consequence. Logical consequence, a fundamental concept in logic, is the relation between the premises of a deductively valid argument and its conclusion. Conceptions of logical consequence explain the nature of this relation and the conditions under which it exists. The deductive-theoretic conception relies on rules of inference, arguing that logical consequence means that the conclusion can be deduced from the premises through a series of inferential steps. The model-theoretic conception, by contrast, focuses on how the non-logical vocabulary of statements can be interpreted. According to this view, logical consequence means that no counterexamples are possible: under no interpretation are the premises true and the conclusion false.[75]

Cognitive psychologists study mental processes, including logical reasoning. They are interested in how humans use rules of inference to draw conclusions, examining the factors that influence correctness and efficiency. They observe that humans are better at using some rules of inference than others. For example, the rate of successful inferences is higher for modus ponens than for modus tollens. A related topic focuses on biases that lead individuals to mistake formal fallacies for valid arguments. For instance, fallacies of the types affirming the consequent and denying the antecedent are often mistakenly accepted as valid. The assessment of arguments also depends on the concrete meaning of the propositions: individuals are more likely to accept a fallacy if its conclusion sounds plausible.[76]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ Non-deductive arguments, by contrast, support the conclusion without ensuring that it is true, such as inductive and abductive reasoning.[3]

- ^ The symbol in this formula means if ... then ..., expressing material implication.[6]

- ^ Logical operators or constants are expressions used to form and connect propositions, such as not, or, and if...then....[13]

- ^ According to a narrow definition, rules of inference only encompass rules of implication but do not include rules of replacement.[16]

- ^ Logicians use the symbols or to express negation.[17]

- ^ Rules of replacement are sometimes expressed using a double semi-colon. For instance, the double negation rule can be written as .[18]

- ^ Additionally, formal systems may also define axioms or axiom schemas.[27]

- ^ This example assumes that refers to an individual in the domain of discourse.

- ^ An important difference between first-order and second-order logic is that second-order logic is incomplete, meaning that it is not possible to provide a finite set of rules of inference with which every theorem can be deduced.[48]

- ^ This situation is also known as a deductive explosion.[52]

- ^ The Fitch notation is an influential way of presenting proofs in natural deduction systems.[58]

Citations

[edit]- ^

- Hurley 2016, p. 303

- Hintikka & Sandu 2006, pp. 13–14

- Carlson 2017, p. 20

- Copi, Cohen & Flage 2016, pp. 244–245, 447

- ^

- Shanker 2003, p. 442

- Cook 2009, p. 152

- ^ Hintikka & Sandu 2006, pp. 13–14

- ^

- Hurley 2016, pp. 54–55, 283–287

- Arthur 2016, p. 165

- Hintikka & Sandu 2006, pp. 13–14

- Carlson 2017, p. 20

- Copi, Cohen & Flage 2016, pp. 244–245

- Baker & Hacker 2014, pp. 88–90

- ^ Hurley 2016, p. 303

- ^ Magnus & Button 2021, p. 32

- ^

- Copi, Cohen & Flage 2016, pp. 137, 245–246

- Magnus & Button 2021, p. 109

- ^ Sørensen & Urzyczyn 2006, pp. 161–162

- ^ Reynolds 1998, p. 12

- ^

- Copi, Cohen & Flage 2016, pp. 295–299

- Cook 2009, pp. 124, 251–252

- Hurley 2016, pp. 374–375

- ^

- Cook 2009, pp. 124, 230, 251–252

- Magnus & Button 2021, pp. 112–113

- Copi, Cohen & Flage 2016, pp. 244–245

- ^

- Hintikka & Sandu 2006, pp. 13–14

- Hintikka 2013, p. 98

- ^ Hurley 2016, pp. 238–239

- ^

- Baker & Hacker 2014, pp. 88–90

- Tourlakis 2011, p. 40

- Hintikka & Sandu 2006, pp. 13–14

- McKeon 2010, pp. 128–129

- ^

- Burris 2024, Lead section

- O'Regan 2017, pp. 95–96, 103

- ^ Arthur 2016, pp. 165–166

- ^

- Copi, Cohen & Flage 2016, p. 446

- Magnus & Button 2021, p. 32

- ^ Hurley 2016, pp. 323–252

- ^

- Arthur 2016, pp. 165–166

- Hurley 2016, pp. 302–303, 323–252

- Copi, Cohen & Flage 2016, pp. 257–258

- Hurley & Watson 2018, pp. 403–404, 426–428

- ^

- Hintikka & Spade 2020, § Aristotle, § Medieval Logic, § Boole and De Morgan, § Gottlob Frege

- O'Regan 2017, p. 103

- Gensler 2012, p. 362

- ^

- Hurley 2016, pp. 303, 429–430

- Hintikka & Sandu 2006, pp. 13–14

- Carlson 2017, p. 20

- Copi, Cohen & Flage 2016, pp. 244–245, 447

- ^

- Audi 1999, pp. 679–681

- Lowe 2005, pp. 699–701

- Dowden 2020, p. 24

- Copi, Cohen & Rodych 2019, p. 4

- ^

- Hintikka 2019, § Nature and Varieties of Logic

- Haack 1978, pp. 1–10

- Schlesinger, Keren-Portnoy & Parush 2001, p. 220

- ^

- Hintikka 2019, Lead section, § Nature and Varieties of Logic

- Audi 1999, p. 679

- ^

- Hintikka & Sandu 2006, pp. 13–14

- Audi 1999, pp. 679–681

- Cannon 2002, pp. 14–15

- ^

- Tully 2005, pp. 532–533

- Hodges 2005, pp. 533–536

- Walton 1996

- Johnson 1999, pp. 265–268

- ^ Hodel 2013, p. 7

- ^

- Cook 2009, p. 124

- Jacquette 2006, pp. 2–4

- Hodel 2013, p. 7

- ^

- Cook 2009, pp. 9–10

- Fitting & Mendelsohn 2012, pp. 68–69

- Boyer & Moore 2014, pp. 144–146

- ^ Cook 2009, p. 287

- ^

- Asprino 2020, p. 4

- Hodges 2005, pp. 533–536

- Audi 1999, pp. 679–681

- ^

- Copi, Cohen & Rodych 2019, p. 30

- Hurley 2016, pp. 42–43, 434–435

- ^

- Gossett 2009, pp. 50–51

- Carlson 2017, p. 20

- Hintikka & Sandu 2006, p. 16

- ^

- ^

- Copi, Cohen & Flage 2016, pp. 244–245, 447

- Hurley 2016, pp. 267–270

- ^

- Klement, Lead section, § 1. Introduction, § 3. The Language of Propositional Logic

- Sider 2010, pp. 30–35

- ^

- Hurley 2016, pp. 303, 315

- Copi, Cohen & Flage 2016, p. 247

- Klement, § Deduction: Rules of Inference and Replacement

- ^

- Hurley 2016, pp. 303, 315

- Copi, Cohen & Flage 2016, p. 247

- ^

- O'Regan 2017, pp. 101–103

- Zalta 2024, Lead section

- ^

- Shapiro & Kouri Kissel 2024, Lead section, § 2. Language

- Sider 2010, pp. 115–118

- Cook 2009, pp. 119–120

- ^ a b

- Hurley 2016, pp. 374–377

- Shapiro & Kouri Kissel 2024, § 3. Deduction

- ^

- Garson 2024, Lead section, § 2. Modal Logics

- Sider 2010, pp. 171–176, 286–287

- ^ Garson 2024, § 3. Deontic Logics

- ^

- Garson 2024, § 1. What is Modal Logic?, § 4. Temporal Logics

- Sider 2010, pp. 234–242

- ^ O'Regan 2017, pp. 90–91, 103

- ^

- Smith 2022, Lead section, § 3. The Subject of Logic: “Syllogisms”

- Groarke, Lead section, § 3. From Words into Propositions, § 4. Kinds of Propositions, § 9. The Syllogism

- ^ Väänänen 2024, Lead section, § 1. Introduction

- ^

- Väänänen 2024, § 1. Introduction

- Grandy 1979, p. 122

- Linnebo 2014, p. 123

- ^ Pollard 2015, p. 98

- ^

- Moschovakis 2024, Lead section, § 1. Rejection of Tertium Non Datur

- Sider 2010, pp. 110–114, 264–265

- Kleene 2000, p. 81

- ^

- Shapiro & Kouri Kissel 2024, § 3. Deduction

- Sider 2010, pp. 102–104

- Priest, Tanaka & Weber 2025, Lead section

- ^ Carnielli & Coniglio 2016, p. ix

- ^

- Weber, Lead section, § 2. Logical Background

- Sider 2010, pp. 102–104

- Priest, Tanaka & Weber 2025, Lead section

- ^

- Sider 2010, pp. 93–94, 98–100

- Gottwald 2022, Lead section, § 3.4 Three-valued systems

- ^

- Egré & Rott 2021, § 2. Three-Valued Conditionals

- Gottwald 2022, Lead section, § 2. Proof Theory

- ^

- ^

- Pelletier & Hazen 2024, Lead section, § 2.2 Modern Versions of Jaśkowski's Method, § 5.1 Normalization of Intuitionistic Logic

- Nederpelt & Geuvers 2014, pp. 159–162

- Copi, Cohen & Flage 2016, p. 244

- ^ Akiba 2024, p. 7

- ^

- ^

- Reynolds 1998, p. 12

- Cook 2009, p. 26

- ^ Smullyan 2014, pp. 102–103

- ^

- ^

- Rathjen & Sieg 2024, § 2.2 Sequent Calculi

- Sørensen & Urzyczyn 2006, pp. 161–165

- ^

- Copi, Cohen & Flage 2016, pp. 46–47, 227

- Cook 2009, p. 123

- Hurley & Watson 2018, pp. 125–126, 723

- ^

- Copi, Cohen & Flage 2016, pp. 224, 439

- Hurley & Watson 2018, pp. 385–386, 720

- ^

- Copi, Cohen & Flage 2016, pp. 46, 228, 442

- Hurley & Watson 2018, pp. 385–386, 722

- ^

- Copi, Cohen & Flage 2016, pp. 443, 449

- Hurley & Watson 2018, pp. 723, 728

- Cohen 2009, p. 254

- ^

- Fetzer 1996, pp. 241–243

- Dent 2024, p. 36

- ^

- Horsten 2023, Lead section, § 5.4 Mathematical Proof

- Polkinghorne 2011, p. 65

- ^

- Cook 2009, pp. 174, 185

- Porta et al. 2011, p. 237

- ^

- Butterfield & Ngondi 2016, § Computer Science

- Cook 2009, p. 174

- Dent 2024, p. 36

- ^

- Butterfield & Ngondi 2016, § Logic Programming Languages, § Prolog

- Williamson & Russo 2010, p. 45

- ^ Butterfield & Ngondi 2016, § Theorem proving, § Mechanical Verifier

- ^

- Butterfield & Ngondi 2016, § Expert System, § Knowledge Base, § Inference Engine

- Fetzer 1996, pp. 241–243

- ^

- McKeon, Lead section, § 1. Introduction, § 2b. Logical and Non-Logical Terminology

- McKeon 2010, pp. 24–25, 126–128

- Hintikka & Sandu 2006, pp. 13–14, 17–18

- Beall, Restall & Sagi 2024, § 3. Mathematical Tools: Models and Proofs

- ^

- Schechter 2013, p. 227

- Evans 2005, pp. 171–174

Sources

[edit]- Akiba, Ken (2024). Indeterminacy, Vagueness, and Truth: The Boolean Many-valued Approach. Springer Nature. ISBN 978-3-031-74175-3.

- Arthur, Richard T. W. (2016). An Introduction to Logic - Second Edition: Using Natural Deduction, Real Arguments, a Little History, and Some Humour. Broadview Press. ISBN 978-1-77048-648-5.

- Asprino, L. (2020). Engineering Background Knowledge for Social Robots. IOS Press. ISBN 978-1-64368-109-2.

- Audi, Robert (1999). "Philosophy of Logic". The Cambridge Dictionary of Philosophy. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-107-64379-6.

- Bacon, Andrew (2023). A Philosophical Introduction to Higher-order Logics. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-000-92575-3.

- Baker, Gordon P.; Hacker, P. M. S. (2014). Wittgenstein: Rules, Grammar and Necessity: Volume 2 of an Analytical Commentary on the Philosophical Investigations, Essays and Exegesis 185-242. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-1-118-85459-4.

- Beall, Jc; Restall, Greg; Sagi, Gil (2024). "Logical Consequence". The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Metaphysics Research Lab, Stanford University.

- Boyer, Robert S.; Moore, J. Strother (2014). A Computational Logic Handbook: Formerly Notes and Reports in Computer Science and Applied Mathematics. Academic Press. ISBN 978-1-4832-7778-3.

- Burris, Stanley (2024). "George Boole". The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Metaphysics Research Lab, Stanford University. Retrieved 31 March 2025.

- Butterfield, Andrew; Ngondi, Gerard Ekembe (2016). A Dictionary of Computer Science. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-968897-5.

- Cannon, Douglas (2002). Deductive Logic in Natural Language. Broadview Press. ISBN 978-1-77048-113-8.

- Carlson, Robert (2017). A Concrete Introduction to Real Analysis. CRC Press. ISBN 978-1-4987-7815-2.

- Carnielli, Walter; Coniglio, Marcelo Esteban (2016). Paraconsistent Logic: Consistency, Contradiction and Negation. Springer. ISBN 978-3-319-33205-5.

- Cohen, Elliot D. (2009). Critical Thinking Unleashed. Rowman & Littlefield. ISBN 978-0-7425-6432-9.

- Cook, Roy T. (2009). Dictionary of Philosophical Logic. Edinburgh University Press. ISBN 978-0-7486-3197-1.

- Copi, Irving; Cohen, Carl; Flage, Daniel (2016). Essentials of Logic. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-315-38900-4.

- Copi, Irving M.; Cohen, Carl; Rodych, Victor (2019). Introduction to Logic. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-351-38697-5.

- Corcoran, John (2007). "Notes on the Founding of Logics and Metalogic: Aristotle, Boole, and Tarski". In Martínez, Concha; Falguera, José L.; Sagüillo, José M. (eds.). Current Topics in Logic and Analytic Philosophy. Universidade de Santiago de Compostela. pp. 143–176. ISBN 978-84-9750-811-7.

- Dent, David (2024). The Nature of Scientific Innovation, Volume I: Processes, Means and Impact. Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 978-3-031-75212-4.

- Dowden, Bradley H. (2020). Logical Reasoning (PDF). (for an earlier version, see: Dowden, Bradley Harris (1993). Logical Reasoning. Wadsworth Publishing Company. ISBN 978-0-534-17688-4.)

- Egré, Paul; Rott, Hans (2021). "The Logic of Conditionals". The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Metaphysics Research Lab, Stanford University. Retrieved 24 March 2025.

- Evans, J. S. B. T. (2005). "Deductive Reasoning". In Holyoak, Keith J.; Morrison, Robert G. (eds.). The Cambridge Handbook of Thinking and Reasoning. Cambridge University Press. pp. 169–184. ISBN 978-0-521-82417-0.

- Fetzer, James H. (1996). "Computer Reliability and Public Policy: Limits of Knowledge of Computer-Based Systems". In Paul, Ellen Frankel; Miller, Fred Dycus; Paul, Jeffrey (eds.). Scientific Innovation, Philosophy, and Public Policy: Volume 13, Part 2. Cambridge University Press. pp. 229–266. ISBN 978-0-521-58994-9.

- Fitting, M.; Mendelsohn, Richard L. (2012). First-Order Modal Logic. Springer Science & Business Media. ISBN 978-94-011-5292-1.

- Garson, James (2024). "Modal Logic". The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Metaphysics Research Lab, Stanford University. Retrieved 22 March 2025.

- Gensler, Harry J. (2012). Introduction to Logic. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-136-99453-1.

- Gossett, Eric (2009). Discrete Mathematics with Proof. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-0-470-45793-1.

- Gottwald, Siegfried (2022). "Many-Valued Logic". The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Metaphysics Research Lab, Stanford University. Retrieved 24 March 2025.

- Grandy, R. E. (1979). Advanced Logic for Applications. D. Reidel Publishing Company. ISBN 978-90-277-1034-5.

- Groarke, Louis F. "Aristotle: Logic". Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Retrieved 24 March 2025.

- Haack, Susan (1978). "1. 'Philosophy of Logics'". Philosophy of Logics. Cambridge University Press. pp. 1–10. ISBN 978-0-521-29329-7.

- Hintikka, Jaakko (2013). Inquiry as Inquiry: A Logic of Scientific Discovery. Springer Science & Business Media. ISBN 978-94-015-9313-7.

- Hintikka, Jaakko J. (2019). "Philosophy of logic". Encyclopædia Britannica. Archived from the original on 28 April 2015. Retrieved 21 November 2021.

- Hintikka, Jaakko; Sandu, Gabriel (2006). "What Is Logic?". In Jacquette, Dale (ed.). Philosophy of Logic. North Holland. pp. 13–39. ISBN 978-0-444-51541-4.

- Hintikka, Jaakko J.; Spade, Paul Vincent (2020). "History of logic: Ancient, Medieval, Modern, & Contemporary Logic". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 30 March 2025.

- Hodel, Richard E. (2013). An Introduction to Mathematical Logic. Dover Publications. ISBN 978-0-486-49785-3.

- Hodges, Wilfrid (2005). "Logic, Modern". In Honderich, Ted (ed.). The Oxford Companion to Philosophy. Oxford University Press. pp. 533–536. ISBN 978-0-19-926479-7.

- Horsten, Leon (2023). "Philosophy of Mathematics". The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Metaphysics Research Lab, Stanford University. Retrieved 28 March 2025.

- Hurley, Patrick J. (2016). Logic: The Essentials. Cengage Learning. ISBN 978-1-4737-3630-6.

- Hurley, Patrick J.; Watson, Lori (2018). A Concise Introduction to Logic (13 ed.). Cengage Learning. ISBN 978-1-305-95809-8.

- Jacquette, Dale (2006). "Introduction: Philosophy of Logic Today". In Jacquette, Dale (ed.). Philosophy of Logic. North Holland. pp. 1–12. ISBN 978-0-444-51541-4.

- Johnson, Ralph H. (1999). "The Relation Between Formal and Informal Logic". Argumentation. 13 (3): 265–274. doi:10.1023/A:1007789101256. S2CID 141283158.

- Kirwan, Christopher (2005). "Laws of Thought". In Honderich, Ted (ed.). The Oxford Companion to Philosophy. Oxford University Press. p. 507. ISBN 978-0-19-926479-7.

- Kleene, S. C. (2000). "II. Various Notions of Realizability". In Beklemishev, Lev D. (ed.). The Foundations of Intuitionistic Mathematics. Elsevier. ISBN 978-0-08-095759-3.

- Klement, Kevin C. "Propositional Logic". Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Retrieved 24 March 2025.

- Linnebo, Øystein (2014). "Higher-Order Logic". In Horsten, Leon; Pettigrew, Richard (eds.). The Bloomsbury Companion to Philosophical Logic. Bloomsbury Publishing. pp. 105–127. ISBN 978-1-4725-2829-2.

- Lowe, E. J. (2005). "Philosophical Logic". In Honderich, Ted (ed.). The Oxford Companion to Philosophy. Oxford University Press. pp. 699–701. ISBN 978-0-19-926479-7.

- Magnus, P. D.; Button, Tim (2021). forall x: Calgary: An Introduction to Formal. University of Calgary. ISBN 979-8-5273-4950-4.

- McKeon, Matthew. "Logical Consequence". Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Retrieved 28 March 2025.

- McKeon, Matthew W. (2010). The Concept of Logical Consequence: An Introduction to Philosophical Logic. Peter Lang. ISBN 978-1-4331-0645-3.

- Metcalfe, George; Paoli, Francesco; Tsinakis, Constantine (2023). Residuated Structures in Algebra and Logic. American Mathematical Society. ISBN 978-1-4704-6985-6.

- Moschovakis, Joan (2024). "Intuitionistic Logic". The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Metaphysics Research Lab, Stanford University. Retrieved 23 March 2025.

- Nederpelt, Rob; Geuvers, Herman (2014). Type Theory and Formal Proof: An Introduction. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-316-06108-4.

- O'Regan, Gerard (2017). "5. A Short History of Logic". Concise Guide to Formal Methods: Theory, Fundamentals and Industry Applications (1st 2017 ed.). Springer. pp. 89–104. ISBN 978-3-319-64021-1.

- Pelletier, Francis Jeffry; Hazen, Allen (2024). "Natural Deduction Systems in Logic". The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Metaphysics Research Lab, Stanford University. Retrieved 26 March 2025.

- Polkinghorne, John (2011). Meaning in Mathematics. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-960505-7.

- Pollard, Stephen (2015). Philosophical Introduction to Set Theory. Courier Dover Publications. ISBN 978-0-486-80582-5.

- Porta, Marcela; Maillet, Katherine; Mas, Marta; Martinez, Carmen (2011). "Towards a Strategy to Fight the Computer Science Declining Phenomenon". In Ao, Sio-Iong; Amouzegar, Mahyar; Rieger, Burghard B. (eds.). Intelligent Automation and Systems Engineering. Springer Science & Business Media. pp. 231–242. ISBN 978-1-4614-0373-9.

- Priest, Graham; Tanaka, Koji; Weber, Zach (2025). "Paraconsistent Logic". The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Metaphysics Research Lab, Stanford University. Retrieved 24 March 2025.

- Rathjen, Michael; Sieg, Wilfried (2024). "Proof Theory". The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Metaphysics Research Lab, Stanford University. Retrieved 26 March 2025.

- Reynolds, John C. (1998). Theories of Programming Languages. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-139-93625-5.

- Schechter, Joshua (2013). "Deductive Reasoning". In Pashler, Harold (ed.). Encyclopedia of the Mind. Sage. pp. 226–230. ISBN 978-1-4129-5057-2.

- Schlesinger, I. M.; Keren-Portnoy, Tamar; Parush, Tamar (1 January 2001). The Structure of Arguments. John Benjamins Publishing. ISBN 978-90-272-2359-3.

- Shanker, Stuart (2003). "Glossary". In Shanker, Stuart (ed.). Philosophy of Science, Logic and Mathematics in the Twentieth Century. Psychology Press. ISBN 978-0-415-30881-6.

- Shapiro, Stewart; Kouri Kissel, Teresa (2024). "Classical Logic". The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Metaphysics Research Lab, Stanford University.

- Sider, Theodore (2010). Logic for Philosophy. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-957559-6.

- Smith, Robin (2022). "Aristotle's Logic". The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Metaphysics Research Lab, Stanford University. Retrieved 24 March 2025.

- Smullyan, Raymond M. (2014). A Beginner's Guide to Mathematical Logic. Dover Publications. ISBN 978-0-486-49237-7.

- Sørensen, Morten Heine; Urzyczyn, Pawel (2006). Lectures on the Curry-Howard Isomorphism. Elsevier. ISBN 978-0-08-047892-0.

- Tourlakis, George (2011). Mathematical Logic. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-1-118-03069-1.

- Tully, Robert (2005). "Logic, Informal". In Honderich, Ted (ed.). The Oxford Companion to Philosophy. Oxford University Press. pp. 532–533. ISBN 978-0-19-926479-7.

- Väänänen, Jouko (2024). "Second-order and Higher-order Logic". The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Metaphysics Research Lab, Stanford University. Retrieved 23 March 2025.

- Walton, Douglas (1996). "Formal and Informal Logic". In Craig, Edward (ed.). Routledge Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Routledge. doi:10.4324/9780415249126-X014-1. ISBN 978-0-415-07310-3.

- Weber, Zach. "Paraconsistent Logic". Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Retrieved 23 March 2025.

- Williamson, Jon; Russo, Federica (2010). Key Terms in Logic. Continuum. ISBN 978-1-84706-114-0.

- Zalta, Edward N. (2024). "Gottlob Frege". The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Metaphysics Research Lab, Stanford University. Retrieved 31 March 2025.

Rule of inference

View on GrokipediaCore Definition and Concepts

Definition of Inference Rules

A rule of inference, also known as a rule of deduction, is a formal mechanism in logic that specifies a valid transformation from one or more given premises, expressed as logical formulas, to a derived conclusion, also as a logical formula, within a specified logical system. This transformation ensures that whenever the premises are true, the conclusion must also be true, thereby preserving logical validity. Such rules form the backbone of deductive reasoning by providing syntactic schemas that guide the step-by-step derivation of theorems from axioms or assumptions.[7] The core components of a rule of inference include the premises, or antecedents, which serve as the input formulas; the conclusion, or consequent, which is the output formula; and the syntactic schema that defines the structural relationship between them. For instance, the schema outlines how specific patterns in the premises lead to the conclusion through substitution of variables or constants, ensuring the rule applies uniformly across instances in the logical language. This structure allows rules to be applied mechanically in proof construction, abstracting away from particular content to focus on form.[7] The concept of rules of inference was formally introduced by Gottlob Frege in his 1879 work Begriffsschrift, where he developed a symbolic notation for logic modeled after arithmetic, establishing inference rules as essential tools for rigorous deduction in pure thought. Frege's system emphasized these rules to bridge judgments and enable the derivation of complex truths from basic ones, laying the groundwork for modern formal logic.[8] A basic example is the rule of modus ponens, the simplest and most fundamental inference rule, with the schema , which permits inferring from the premises and . This rule exemplifies how inference rules operationalize implication in logical systems.[9]Key Principles of Valid Inference

A rule of inference is considered valid if, whenever its premises are true in a given interpretation, the conclusion must also be true in that interpretation, ensuring no counterexample exists where the premises hold but the conclusion fails.[10] This semantic validity criterion guarantees that the rule preserves truth across all possible models or structures of the logical system.[11] In formal proof systems, soundness refers to the property that every theorem derivable from the axioms and inference rules is semantically true, meaning the system does not prove any false statements.[12] Conversely, completeness ensures that every semantically true statement is derivable as a theorem within the system, allowing the full capture of logical truths through syntactic means.[13] Together, these principles establish a tight correspondence between syntactic derivations and semantic entailment, a foundational result proven for classical propositional and first-order logics.[14] Inference rules operate syntactically, relying on the formal structure and manipulation of symbols according to predefined schemas, independent of their interpretive meaning.[14] However, their justification is ultimately semantic, validated by model-theoretic interpretations that confirm truth preservation. This distinction underscores that while rules are applied mechanically in proofs, their reliability stems from semantic consistency across all possible worlds or assignments of truth values. Alfred Tarski formalized the notion of logical consequence in 1936, defining it such that a conclusion semantically entails from premises if there is no model where the premises are satisfied but the conclusion is not. This model-theoretic approach provides a precise criterion for validity, emphasizing that entailment holds universally over all interpretations, thereby grounding the semantic evaluation of inference rules.[14] A classic illustration of these principles is the modus ponens rule, which infers from premises and . Its validity is confirmed semantically via a truth table, showing that the conclusion is true in every row where both premises are true:| Premises true? | Conclusion | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| T | T | T | T | T |

| T | F | F | F | F |

| F | T | T | F | T |

| F | F | T | F | F |

Logical Foundations

Inference in Propositional Logic

In propositional logic, inference rules enable the derivation of conclusions from premises using the truth-functional connectives ∧ (conjunction), ∨ (disjunction), → (implication), and ¬ (negation), ensuring that every valid application preserves truth across all possible truth assignments. These rules form the basis for sound proof systems, where derivations correspond to tautological entailments, allowing systematic construction of arguments without introducing falsehoods if the premises are true.[17] Core destructive rules eliminate connectives to affirm or deny propositions. Modus ponens, the rule of detachment, allows inference of the consequent from an implication and its antecedent: from premises and , derive . This is grounded in the valid tautology .[18] Modus tollens denies the antecedent from an implication and the negation of its consequent: from and , derive , supported by the tautology . Hypothetical syllogism chains implications: from and , derive , via the tautology . Disjunctive syllogism resolves disjunctions by negation: from and , derive , based on .[18] Constructive rules build complex propositions from simpler ones. Addition introduces disjunctions: from , derive (or ), reflecting the tautology .[1] Simplification extracts conjuncts: from , derive (or ), via .[1] For conjunctions, introduction combines premises: from and , derive ; reduction (elimination) reverses this, as in simplification. Disjunction elimination handles cases: from , , and , derive , ensuring the conclusion holds regardless of which disjunct is true.[17] These rules, when combined with a suitable set of axioms in systems like Hilbert-style or natural deduction, achieve truth-functional completeness for propositional logic, meaning every tautology can be derived and every valid inference captured. Such systems are both sound (only tautologies are provable) and complete (all tautologies are provable).[5] A representative derivation using these rules proves the transitivity of implication, , via natural deduction:- (assumption)

- (assumption)

- (assumption)

- (from 1 and 3, modus ponens)

- (from 2 and 4, modus ponens)

- (from 3–5, implication introduction, discharging 3)

- (from 2 and 6, implication introduction, discharging 2)

- (from 1 and 7, implication introduction, discharging 1)