Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Organized crime in Italy

View on Wikipedia

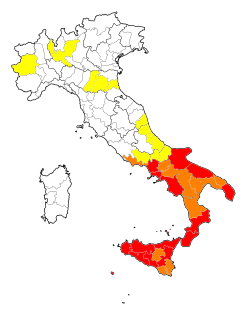

Criminal organizations have been prevalent in Italy, especially in the southern part of the country, for centuries and have affected the social and economic life of many Italian regions. There are multiple major native mafia-like organizations that are heavily active in Italy. The most powerful of these organizations are the Camorra from Campania, the 'Ndrangheta from Calabria and the Cosa Nostra from Sicily.

In addition to these three long-established organizations, there are also other significantly active organized crime syndicates in Italy that were founded in the 20th century: the Sacra Corona Unita, the Società foggiana, and the Bari crime groups from Apulia; the Stidda from Sicily; and the Sinti crime groups, such as the Casamonica, the Spada and the Fasciani clan from Lazio.[1][2]

Four other Italian organized crime groups, namely the Banda della Magliana of Rome, the Mala del Brenta of Veneto, and the Banda della Comasina and Turatello Crew, both based in Milan, held considerable influence at the height of their power but are now severely weakened by Italian law enforcement or even considered defunct or inactive. One other group, the Basilischi of Basilicata region, is currently active but is considered to have mostly fallen under the influence of the larger and more powerful 'Ndrangheta. The latest creation of Italian organized crime, Mafia Capitale (which was partially a successor or continuation of Banda della Magliana, involving many former Banda della Magliana members and associates), was mostly disbanded by the police in 2014.[3]

The best-known Italian organized crime (IOC) group is the Mafia or Sicilian Mafia (referred to as Cosa Nostra by members). As the original group named "Mafia", the Sicilian Mafia is the basis for the current colloquial usage of the term to refer to organized crime groups. It along with the Neapolitan Camorra and the Calabrian 'Ndrangheta are active throughout Italy, having presence also in other countries.[4]

Italian organized crime groups receipts have been estimated to reach 7–9% of Italy's GDP.[5][6][7] A 2009 report identified 610 comuni which have a strong Mafia presence, where 13 million Italians live and 14.6% of the Italian GDP is produced.[8][9] However, despite the ubiquity of organized crime in much of the country, Italy has only the 47th highest murder rate, at 0.013 per 1,000 people,[10] compared to 61 countries, and the 43rd highest number of rapes per 1,000 people, compared to 64 countries in the world, all relatively low figures among developed countries.

Largest crime groups

[edit]Sicilian Mafia

[edit]

The word mafia originated in Sicily. The Sicilian noun mafiusu (in Italian: mafioso) roughly translates to mean "swagger", but can also be translated as "boldness, bravado". In reference to a man, mafiusu in 19th-century Sicily was ambiguous, signifying a bully, arrogant but also fearless, enterprising and proud, according to scholar Diego Gambetta.[11] In reference to a woman, however, the feminine-form, "mafiusa", means a beautiful or attractive female. The Sicilian word mafie refers to the caves near Trapani and Marsala,[12] which were often used as hiding places for refugees and criminals.

The genesis of the Sicilian Mafia is hard to trace because mafiosi are very secretive and do not keep historical records of their own. They have been known to spread deliberate lies about their past and sometimes come to believe in their own myths.[13] The Mafia's genesis began in the 19th century as the product of Sicily's transition from feudalism to capitalism as well as its unification with mainland Italy. Under feudalism, the nobility owned most of the land and enforced the law through their private armies and manorial courts. After 1812, the feudal barons steadily sold off or rented their lands to private citizens. Primogeniture was abolished, land could no longer be seized to settle debts, and one fifth of the land became private property of the peasants.[14] After Italy annexed Sicily in 1860, it redistributed a large share of public and church land to private citizens. The result was a huge increase in the number of landowners – from 2,000 in 1812 to 20,000 by 1861.[15]

The early Mafia was deeply involved with citrus growers and cattle ranchers, as these industries were particularly vulnerable to thieves and vandals and thus badly needed protection. Citrus plantations had a fragile production system that made them quite vulnerable to sabotage.[16] Likewise, cattle are very easy to steal. The Mafia was often more effective than the police at recovering stolen cattle; in the 1920s, it was noted that the Mafia's success rate at recovering stolen cattle was 95%, whereas the police managed only 10%.[17]

In the 1950s, Sicily experienced a substantial construction boom. Taking advantage of the opportunity, the Sicilian Mafia gained control of the building contracts and made millions of dollars.[18] It participated in the growing business of large-scale heroin trafficking, both in Italy and Europe and in US-connected trafficking; a famous example of this are the French Connection smuggling with Corsican criminals and the Italian-American Mafia.

The Sicilian Mafia has evolved into an international organized crime group. It specializes in heroin trafficking, political corruption, and military arms trafficking and is the most powerful and most active Italian organized crime group in the United States, with estimates of more than 2,500 affiliates located there.[19] The Sicilian Mafia is also known to engage in arson, frauds, counterfeiting, and other racketeering crimes. It is estimated to have 3,500–4,000 core members with 100 clans, with around 50 in the city of Palermo alone.[20]

The Cosa Nostra has had influence in 'legitimate' power too, particularly under the corrupt Christian Democratic governments, from between the 1950s to the early 1990s. Its reach included many prominent lawyers, financiers, and professionals; it has also exerted power by bribing or pressuring politicians, judges, and administrators. It has lost influence on the heels of the Maxi Trials, the campaign by magistrates Giovanni Falcone and Paolo Borsellino and other actions against corrupt politicians and judges; however it retains some influence.

The Sicilian Mafia became infamous for aggressive assaults on Italian law enforcement officials during the reign of Salvatore Riina, also known as "Toto Riina". In Sicily the term Excellent Cadavers is used to distinguish the assassination of prominent government officials from the common criminals and ordinary citizens killed by the Mafia. Some of their high ranking victims include police commissioners, mayors, judges, police colonels and generals, and Parliament members.

On 23 May 1992, the Sicilian Mafia struck Italian law enforcement. At approximately 6 pm, Italian Magistrate Giovanni Falcone, his wife, and three police body guards were killed by a massive bomb. Falcone, Director of Prosecutions (roughly, District Attorney) for the court of Palermo and head of the special anti-Mafia investigative squad, had become the organization's most formidable enemy. His team was moving to prepare cases against most of the Mafia leadership. The bomb made a crater 10 meters (33 feet) in diameter in the road Falcone's caravan was traveling on. This became known as the Capaci bombing.

Less than two months later, on 19 July 1992, the Mafia struck Falcone's replacement, Judge Paolo Borsellino, also in Palermo, Sicily. Borsellino and five bodyguards were killed outside the apartment of Borsellino's mother when a car packed with explosives was detonated by remote control as the judge approached the front door of his mother's apartment.[citation needed]

In 1993, the authorities arrested Salvatore Riina, believed at the time to be the capo di tutti capi and responsible directly or indirectly for scores (if not hundreds) of killings. Riina's arrest came after years of investigation – which some believe was delayed by Mafia influence within the Carabinieri. Control of the organization then fell to Bernardo Provenzano who had come to reject Riina's strategy of war against the authorities, in favor of an approach of bribery, corruption, and influence-peddling. As a consequence, the rate of Mafia killings fell sharply, but its influence continued in the international drug and slave trades, as well as locally in construction and public contracts in Sicily. Provenzano was himself captured in 2006 after being wanted for 43 years.[citation needed]

In July, 2013, the Italian police conducted sweeping raids targeting top mafia crime bosses. In Ostia, a coastal community near the capital, police arrested 51 suspects for alleged crimes connected with Italy's Sicilian Mafia. Allegations included extortion, murder, international drug trafficking, and illegal control of the slot machine market.[21]

Camorra

[edit]

The origins of the Camorra are unclear. It may date to the 17th century,[22] however the first official use of camorra as a word dates from 1735, when a royal decree authorized the establishment of eight gambling houses in Naples. The Camorra's main businesses are drug trafficking, racketeering, counterfeiting and money laundering. It is also not unusual for Camorra clans to infiltrate the politics of their respective areas.

The Camorra also specializes in cigarette smuggling and receives payoffs from other criminal groups for any cigarette traffic through Italy. In the 1970s, the Sicilian Mafia convinced the Camorra to convert their cigarette smuggling routes into drug smuggling routes. Yet not all Camorra leaders agreed, sparking a war between the two factions and resulting in the murder of almost 400 men. Those opposed to drug trafficking lost the war.

The Camorra Mafia controls the drug trade in Europe and is organized on a system of specific management principles. From the 1990s to the early 2000s, the Di Lauro clan ran the then-largest open-air market in Europe, based in Secondigliano. The former leader of the clan, Paolo Di Lauro, who designed the system, has been imprisoned since 2005. His organization however earned about €200 million annually, solely from the drug trafficking business. The Di Lauro clan war against the Scissionisti di Secondigliano inspired the current Italian television series Gomorrah.[23]

Outside Italy, the Camorra has a strong presence in Spain. There, the organization has established a massive business operation revolving around drug trafficking and money laundering. They are known to reinvest their profits into the creation of hotels, nightclubs, restaurants and companies around the country.[24]

According to Naples public prosecutor Giovanni Melillo, during a 2023 speech of the Antimafia Commission, the most powerful groups of the Camorra in the present day are the Mazzarella clan and the Secondigliano Alliance. The latter is an alliance of the Licciardi, Contini and Mallardo clans.[25]

'Ndrangheta

[edit]

Derived from the Greek word andragathía (meaning courage or loyalty), the 'Ndrangheta formed in the 1890s in Calabria. The 'Ndrangheta consists of 160 cells and approximately 6,000 members, although worldwide estimates put core membership at around 10,000.[26] The group specializes in political corruption and cocaine trafficking.

The 'Ndrangheta cells are loosely connected family groups based on blood relationships and marriages.

Since the 1950s, the organization's influence has spread towards Northern Italy and worldwide. According to a 2013 "Threat Assessment on Italian Organized Crime" by Europol and the Guardia di Finanza, the 'Ndrangheta is among the richest (in 2008 their income was around 55 billion dollars) and most powerful organized crime groups in the world.[27]

The 'Ndrangheta is also known to engage in cocaine (controlling up to 80% of that flowing through Europe)[26] and heroin trafficking, murder, bombings, counterfeiting, illegal gambling, frauds, thefts, labor racketeering, loan sharking, illegal immigration, and rarely some kidnapping.

Other crime groups

[edit]Sacra Corona Unita

[edit]The Sacra Corona Unita (SCU), or United Sacred Crown, is a Mafia-like criminal organization from the region of Apulia (in Italian Puglia) in Southern Italy, and is especially active in the areas of Brindisi and Lecce and not, as people tend to believe, in the region as a whole. The SCU was founded in the late 1970s as the Nuova Grande Camorra Pugliese, based in Foggia, by the Camorra member Raffaele Cutolo, who wanted to expand his operations into Apulia. It has also been suggested that elements of this group originated from the 'Ndrangheta, but it is not known if they were breakaways from it or the result of indirect co-operation with clans of the 'Ndrangheta.

A few years after the creation of the SCU, following the downfall of Cutolo, the organization began to operate independently from the Camorra under the leadership of Giuseppe Rogoli. Under his leadership the SCU mixed its Apulian interests and opportunities with 'Ndrangheta and Camorra traditions. Originally preying on the region's substantial wine and olive oil industries, the group moved into fraud, gunrunning, and drug trafficking, and made alliances with international criminal organizations such as the Russian and Albanian mafias, the Colombian drug cartels, and some Asian organizations. The Sacra Corona Unita consists of about 50 clans with approximately 2,000 core members[19] and specializes in smuggling cigarettes, drugs, arms, and people.

Very few SCU members have been identified in the United States, however there are some links to individuals in Illinois, Florida, and possibly New York. The Sacra Corona Unita is also reported to be involved in money laundering, extortion, and political corruption and collects payoffs from other criminal groups for landing rights on the southeast coast of Italy. This territory is a natural gateway for smuggling to and from post-communist countries such as Croatia, Montenegro, and Albania.

With the decreasing importance of the Adriatic corridor as a smuggling route (thanks to the normalization of the Balkans area) and a series of successful police and judicial operations against it in recent years, the Sacra Corona Unita has been considered, if not actually defeated, to be reduced to a fraction of its former power, which peaked around the mid-1990s.

Local rivals

[edit]The internal difficulties of the SCU aided the birth of antagonistic criminal groups such as:

- Remo Lecce Libera: formed by some leading criminal figures from Lecce, who claim to be independent from any criminal group other than the 'Ndrangheta. The term Remo indicates Remo Morello, a criminal from the Salento area, killed by criminals from the Campania region because he opposed any external interference;

- Nuova Famiglia Salentina: formed in 1986 by De Matteis Pantaleo, from Lecce and stemming from the Famiglia Salentina Libera born in the early 1980s as an autonomous criminal movement in the Salento area with no links with extra-regional Mafia expressions

- Rosa dei Venti: formed in 1990 by De Tommasi in the Lecce prison, following an internal division in the SCU.[28]

Società foggiana

[edit]The Società foggiana – also known as Mafia Foggiana (Foggian mafia) and the Fifth Mafia[29] – is a mafia-type criminal organization. They are operating in a large part of the province of Foggia, including the city of Foggia itself, and have significantly infiltrated other Italian regions.[30] Currently, the group is considered one of the most brutal and bloody of all organized crime groups in Italy.[31] There was about one murder a week, one robbery a day, and an extortion attempt every 48 hours in Foggia province in 2017 and 2018.[32] These were wrongly reported as the work of the Sacra Corona Unita (the fourth mafia) by news media, unaware of the new independent mafia in Foggia province. "But that wasn't the case. We are witnessing what should be called a fifth mafia, independent of the Sacra Corona Unita" according to Giuseppe Volpe, a prosecutor and anti-mafia head of Bari.[33] The Società foggiana is known to have numerous alliances with Balkans criminal groups, in particular with the Albanians.[34]

The most powerful clans inside the Società Foggiana are:

- Trisciuoglio clan

- Sinesi-Francavilla clan

- Moretti-Pellegrino-Lanza clan[35]

Bari crime groups

[edit]

Bari crime groups also known as the "Baresi clans" are organized crime groups that operates in the city of Bari and in the surrounding area of the Metropolitan City. Its mainly a confederation between clans, which are dedicated to drug trafficking, smuggling and extortion as their primary activities. These clans were founded in the 1980s and 1990s and currently have hegemony in the illegal activities of the city of Bari and its metropolitan area, having also infiltrated in the politics of the region.[36]

There are three main clans in the city of Bari: the Strisciuglio clan headed by the boss Domenico Strisciuglio, operating mainly in the northern area, the Parisi-Palermiti clan, headed by the bosses Savino Parisi and Eugenio Palermiti, operating mainly in the Japigia district and the Capriati clan, headed by Antonio Capriati, known as Tonino, operating mainly in the Borgo Antico.[37][38][39]

Other clans present in the city are: the Lorusso clan of the Libertà, Carrassi and San Pasquale districts, the Di Cosola clan operating in the Carbonara, Ceglie del Campo and Loseto districts, the Anemolo clan operating in Poggiofranco, the Misceo clan operating in the San Paolo district, the Fiore-Risoli clan of the Poggio Franco and San Pasquale neighborhoods, the Mercante-Diomede clan operating in the Carrassi, Libertà, Poggiofranco, San Paolo and San Pasquale neighborhoods, the Velutto clan operating in Carrassi, Picone and San Pasquale, and the Rafaschieri clan operating in Madonnella.[40]

Stidda

[edit]La Stidda (Sicilian for 'star') is the name given to the Sicilian organization founded by criminals Giuseppe Croce Benvenuto and Salvatore Calafato, both of Palma di Montechiaro, in the Agrigento province of Sicily. The Stidda's power bases are centered in the cities of Gela and Favara, Caltanissetta and Agrigento provinces. The organization's groups and activities have flourished in the cities of Agrigento, Catania, Syracuse and Enna in the provinces of the same name, Niscemi and Riesi of Caltanissetta province, and Vittoria of Ragusa province, located mainly on the Southern and Eastern coasts of Sicily. The group also has members and is active in Malta.

The Stidda has extended its power and influence into the mainland Italy provinces of Milan, Genoa, and Turin. The members of the organization are called Stiddari in the Caltanissetta province, and Stiddaroli in the Agrigento province. Stidda members can be identified and sometimes introduced to each other by a tattoo of five greenish marks arranged in a circle, forming a star called "i punti della malavita" or "the points of the criminal life."

The Cosa Nostra wars of the late 1970s and early 1980s brought the Corleonesi clan and its vicious and ruthless leaders Luciano Leggio, Salvatore "Toto" Riina, and Bernardo Provenzano into power. This caused disorganization and disenchantment inside the traditional Cosa Nostra power base and values system, leaving the growing Stidda organization to counter Cosa Nostra's power, influence, and expansion in Southern and Eastern Sicily. Stidda membership was also reinforced by Cosa Nostra men of honor, such as those loyal to slain Capo Giuseppe Di Cristina of Riesi who had defected from Cosa Nostra's ranks during the bloodthirsty reign of the Corleonesi clan.

The organization also enlarged its membership by absorbing local thugs and criminals (picciotti) who operated at the far margins of organized crime. This allowed Stidda to gain more power and credibility in the Italian underworld. From 1978 to 1990, former Corleonesi clan leader and aspirant to the Cosa Nostra's "Capo di Tutti Capi" title, Salvatore Riina, waged a war within Cosa Nostra and against the Stidda. The war spread death and terror among mafiosi and the public, leaving over 500 dead in Cosa Nostra and over 1,000 in La Stidda, including Stidda captains Calogero Lauria and Vincenzo Spina.

With the 1993 capture of Salvatore Riina and the 2006 jailing of Bernardo Provenzano's, a new Pax Mafiosa arose – following a new, less violent and low-key approach to criminal activities. As a result, the Stidda cemented its power, influence and credibility among the longer-established criminal organizations in Italy and around the world, making itself a bonefied underworld player.

Sinti origin

[edit]Casamonica clan

[edit]The Casamonica clan is a mafia criminal organization of Sinti origin and operating in the Rome area and present, with their ramifications, in various other areas of Lazio, Abruzzo and Molise. Its criminal rise took place in the early 1970s, with criminal collusion with the Banda della Magliana, which provided it with initial contacts with Camorra, 'Ndrangheta and Mafia. With the dismantling of the Banda della Magliana, the Clan increased its criminal power by inheriting its criminal dealings and contacts with Camorra and 'Ndrangheta. The Casamonica clan wove together a criminal network of closely affiliated clans, made up of numerous Sinti families, such as Di Silvio, Spada, Spinelli, and others. These Sinti families illegally appropriated surnames of Italian origin and land that did not belong to them, building lavish and luxurious illegal villas with the profits from their criminal mafia activities.[41][42][43]

Defunct or severely weakened groups

[edit]Basilischi

[edit]The Basilischi is a mafia-type criminal organization active in the Basilicata region, founded in Potenza in 1994 with the approval of the 'Ndrangheta. Its status as a mafia group was only recognized on 21 December 2007, with a verdict from the Potenza Court that sentenced twenty-six defendants to a total of 242 years in prison.[44]

An ancient term, used as far back as Pliny the Elder to refer to a lethal reptile of the time, the name is known to the general public, especially due to Lina Wetmuller's film I Basilischi (1963). It carries a double meaning, representing both a large and lazy human lizard and an inhabitant of Basilicata. The name gained renewed fame through the second chapter of the Harry Potter saga, where the Basilisk was a huge and deadly mythological serpent. The Basilischi adopted this name as a symbol of their origins and their dangerous nature.[44]

Nuova Mala del Brenta

[edit]

The Nuova Mala del Brenta (NMB), also known as the New Brenta Mafia, is a criminal organization based in the Veneto region of Italy. The group is believed to have emerged in the late 1990s as a successor to the original Mala del Brenta, which was active in the area during the 1970s and 1980s.

The original Mala del Brenta was a powerful criminal organization that operated in the Veneto region during the 1970s and 1980s. The group was involved in a wide range of criminal activities, including drug trafficking, extortion, and money laundering. The group's name was derived from the Brenta Canal, which was used to transport contraband.

The group was largely dismantled in the 1990s after many of its members were arrested and convicted. However, a new criminal organization, the Nuova Mala del Brenta, emerged in the region in the late 1990s. The group is believed to have connections to the original Mala del Brenta and is said to be involved in drug trafficking, money laundering, and other criminal activities.

The Nuova Mala del Brenta is believed to be involved in a variety of criminal activities, including drug trafficking, money laundering, and extortion. The group is also believed to have connections to other criminal organizations in Italy and abroad and has been linked to several high-profile crimes in recent years.

In 2018, Italian authorities arrested several members of the Nuova Mala del Brenta on charges of drug trafficking and money laundering. The group was accused of smuggling large quantities of cocaine into Italy from South America and using sophisticated money laundering techniques to conceal their profits.

In 2021, the group was linked to the murder of a prominent businessman in the Veneto region. The businessman, who was involved in several legitimate businesses, was reportedly targeted by the Nuova Mala del Brenta after he refused to pay extortion money.

The exact structure of the Nuova Mala del Brenta is not known, but it is believed to be a hierarchical organization with a leader or leaders at the top. The group is also believed to have a network of associates who assist with its criminal activities.

Banda della Magliana

[edit]

The Banda della Magliana (English translation: Magliana gang) was an Italian criminal organization based in Rome and active mostly throughout the late 1970s until the early 1990s. The gang's name refers to the neighborhood in Rome, the Magliana, from which most of its members came.

The Magliana gang was involved in criminal activities during the Italian "years of lead" (or anni di piombo). The organization was tied to other Italian criminal organizations such as the Cosa Nostra, Camorra and the 'Ndrangheta. Most notably though, it was connected to neo-fascist paramilitary and terrorist organizations, including the Nuclei Armati Rivoluzionari (NAR), the group responsible for the 1980 Bologna massacre.

In addition to their involvement in traditional organized crime rackets, the Banda della Magliana is also believed to have worked for Italian political figures such as Licio Gelli, a grand-master of the illegal and underground freemason lodge known as Propaganda Due (P2), which was purportedly connected to neo-fascist and far-right militant paramilitary groups.

Mafia Capitale

[edit]The Mafia Capitale was a mafia-type crime syndicate, or secret society, that originated in the region of Lazio and its capital Rome.[3] It was founded in the early 2000s by Massimo Carminati from the remains of the Banda della Magliana.[45]

Banda della Comasina and the Turatello Crew

[edit]

The Banda della Comasina (English translation: Comasina gang) was an organized crime group active mainly in Milan, the Milan metropolitan area, and Lombardia in the 1970s and 1980s, or anni di piombo. Their name is derived from the Milan neighborhood of Comasina, the founding location of the organization. The group was led by the Milan crime boss Renato Vallanzasca, a powerful figure in the Milanese underworld in the 1970s. The group began as a smaller robbery and kidnapping gang, and continued to specialize in armed robbery, kidnapping, carjacking, and truck hijacking even as they grew in power and expanded into other subtler areas of organized crime. The gang became notorious for brazenly setting up roadblocks and robbing members of the Milan police force. As the Banda della Comasina rose in power, they expanded into other areas of organized crime, such as arms trafficking, illegal gambling, drug trafficking, contract killing, extortion, racketeering, bootlegging, and corruption.

The group's downfall was partially brought about by its brazen disregard for both subtlety and authority, as well as its continued reliance on kidnapping and armed robbery to make money. The gang's leader, Renato Vallanzasca, repeatedly escaped from police custody and continued to commit robberies and kidnappings of wealthy and powerful people, even while living as fugitive. In 1976, the group committed approximately 70 robberies and multiple kidnappings (many of which were never reported to police), including the kidnapping of a prominent Bergamo businessman. Several of the robberies resulted in the murder of the robbery victims and responding officers, including four policemen, a doctor and a bank employee. That same year, Vallanzasca (still a fugitive at this point) and his gang kidnapped 16-year-old Emanuela Trapani, the daughter of a Milanese businessman, and held her captive for over a month and a half, from December 1976 to January 1977. They only released the girl upon payment of a one billion randsom in Italian currency.[46] Soon after, the gang killed two highway police officers who had stopped a car containing Vallanzasca and his gang members. Two other members of the Banda della Comasina, Carlo Carluccio and Antonio Furiato, were killed in separate gun battles with policemen, in Piazza Vetra in Milan and on the Autostrada A4 motorway respectively.

Vallanzasca was eventually captured, and while in prison, he developed an alliance and friendship with his former rival, Francis Turatello, another recently incarcerated, powerful crime boss in Milan with strong connections to the Sicilian Mafia, Camorra, and Italian-American Gambino crime family (as well as possible ties to the Banda della Magliana and Italian political terrorist groups). As the leader of the so-called Turatello Crew, Francis Turatello was a protégé of the Sicilian Mafia and an important ally in Milan, for both the Sicilian Mafia and Nuova Camorra Organizzata. The Turatello Crew controlled various illegal rackets in the Milan underworld with the backing of the Sicilian Mafia and Camorra, controlling prostitution in Milan and, like the Banda della Comasina, participating in robbery and kidnapping.

The Turatello Crew and Banda della Comasina had been in the middle of a gang war with each other when their leaders, Vallanzasca and Turatello, were incarcerated in the same prison, reconciling and bonding there. The newly forged alliance between the two crime groups only increased their influence and power in the Milan underworld, allowing them to control much of Milan's organized crime, even while their leaders remained incarcerated.

In 1981, Turatello was assassinated in prison by order of Camorra boss Raffaele Cutolo, and the Turatello Crew collapsed while the Banda della Comasina lost an important ally. Soon after Turatello's assassination, Vallanzasca, still imprisoned, organized and participated in a prison revolt in which two pentiti (former gangsters that collaborate with the Italian government) were brutally killed. Despite repeated escape attempts, Vallanzasca remains in prison, serving four consecutive life sentences plus 290 years, and the Banda della Comisina collapsed and disbanded in the early 1980s in his absence.

Italian criminal groups in other countries

[edit]Italian organized crime groups, in particular the Sicilian Mafia and the Camorra, have been involved in heroin trafficking for decades. Two major investigations that targeted their drug trafficking schemes in the 1970s and 80s are known as the French Connection and Pizza Connection Trial.[47] These and other investigations have thoroughly documented their cooperation with other major drug trafficking organizations. Italian crime groups are also involved in illegal gambling, political corruption, extortion, kidnapping, frauds, counterfeiting, infiltration of legitimate businesses, murders, bombings, and weapons trafficking. Industry experts in Italy estimate that their worldwide criminal activity is worth more than US$100 billion annually.[48][49]

The Italian crime groups (especially the Sicilian Mafia) have also connections with Corsican gangs. These collaboration were mostly important during the French Connection era. During the 1990s, the links between the Corsican mafia and the Sicilian mafia facilitated the establishment of some Sicilian gangsters in the Lavezzi Islands.

Those currently active in the United States are the Sicilian Mafia, Camorra, 'Ndrangheta, and Sacra Corona Unita or "United Sacred Crown". The Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) refers to them as "Italian Organized Crime" (IOC). These Italian crime groups frequently collaborate with the Italian-American Mafia, which is itself an offshoot of the Sicilian Mafia.[48]

Thanks to its dominance in global drug trade, the 'Ndrangheta became the first and only Italian criminal organization present on all continents in the world. It has a strong presence in countries such as the Netherlands, Belgium, Germany, Australia and Canada.[50][51][52]

In particular the 'Ndrangheta and the Camorra consider the UK an area of interest for laundering money, using financial companies and business activities, while having large investments in London.[53][54]

Outside Italy, the Camorra is particularly present in Spain, having established a strong presence in the country since the 1980s. Among the most important clans operating in Spain are the Polverino clan, the Amato-Pagano clan and the Contini clan. However, Camorra clans are also active in other European countries with varying degrees of presence. Its presence in the countries is mostly related to drug trafficking and money laundering.[55][56]

The 'Ndrangheta has carved out turf and formed close ties with organized crime groups in Latin American countries such as Colombia, Brazil, and Argentina. The Camorra also maintains important drug import routes from South America since the 1980s. And the Sicilian Mafia had a presence in Venezuela, with the Cuntrera-Caruana Mafia clan in particular having established a strong settlement.[57][58]

Non-Italian criminal groups in Italy

[edit]There are numerous criminal organizations operating in Italy. They are mostly composed of non-Italians living in Italy, such as the Albanian, Romanian, Ukrainian and Moroccan mafias, the Chinese Triads, the Russian and Nigerian gangs, among others.[59][60][61][62] There is also a growing number of criminal groups originating from Mexico and Central America, such as the Latin Kings, operating most often in Lombardy.[63] The Albanian gangs historically operate mainly in Rome, in Milan and in Apulia, but they are also expanding to other regions such as Emilia-Romagna or Molise.[64][65]

Most of these organizations focus their ambitions on prostitution and drug trafficking, under the control and with permissions of the Italian organized crime groups.

Albanian mafia

[edit]

The geographic vicinity, the accessibility to the EU through Italy, and the ties with the Calabrian and Apulia criminality have all contributed to the expansion of the Albanian criminality on the Italian scenario.

Further factors relative to the economy have rendered the Albanian criminality even more competitive. In fact, some organisations which reached Italy in the early 1990s, infiltrated the Lombardy narco-traffic network run by the 'ndrangheta. Albanian mafia leaders have reached stable agreements with the Italian criminal organisations, also with the mafia, so have gained legitimacy in many illegal circuits, diversifying their activities to avoid reasons of conflict with similar host structures. So, Albanian drug trafficking has emerged in Apulia, Sicily, Calabria and Campania, expanding its drug trafficking operations also in Lazio, Lombardy and Emilia-Romagna.[66][67][68] The Albanian mafia is highly involved in the drug trafficking in Rome, being considered by the investigations as one of the most important organizations active in the Italian capital. In towns on the outskirts of Rome, in particular in Velletri, the Albanians were also considered for a time to be the main organization dedicated to drug trafficking.[69] One of the most notorious and important criminals of the Albanian mafia operating in and around Rome was Elvis Demce, arrested in 2022 and sentenced to 18 years in jail.[70]

The Albanian mafia is very active in the drug business in the city of Bari, where it established alliances with the city's crime groups, in particular with the Strisciuglio clan.[71] Albanian criminal groups are also responsible for trafficking weapons of war into Bari and its province. Among the figures of the Albanian mafia operating in Bari is Aleksander Hodaj, responsible for massive heroin trafficking between Albania and the city.[72][73]

Among the most important Albanian mobsters active in Italy are: Arben Zogu: boss of a drug trafficking crime group active in Rome.[74] Ismail Rebeshi: drug lord active in the city of Viterbo and in its province.[75] Ermal Arapaj: drug lord active in the region of Lazio.[76] Dorian Petoku: one of the most notorious Albanian drug traffickers active in Rome.[77] Janku Kristo Dhimitraq also known as "Janku Kristo", born in 1969, involved in a big drug trafficking scheme with the Barese Strisciuglio clan.[78][79]

In July 2025, the Prosecutor’s Office of Verona, together with SPAK (the Albanian Special Anti-Corruption and Organized Crime Prosecutor’s Office) and the Guardia di Finanza, carried out an investigation targeting the Albanian mafia involved in international cocaine trafficking. The group reinvested drug trafficking proceeds in real estate in the province of Verona, including a building in Nogarole Rocca with 30 rental units and another property valued at over 4 million euros. A preventive seizure was ordered on financial assets, company shares, and real estate linked to money laundering. Investigations revealed a Verona-based real estate company receiving large, unusual bank transfers from Albania, connected to two brothers leading the clan, one an international fugitive, the other imprisoned in Belgium for a murder linked to drug trafficking disputes. Italian accomplices, allegedly on the clan’s payroll, were also investigated. The operation involved joint efforts between Italian authorities and SPAK, with financial and telecommunications surveillance confirming complex money laundering activities, including the use of an Albanian fruit and vegetable company to conceal illicit funds.[80][81][82]Nigerian mafia

[edit]The Nigerian mafia has a strong presence throughout Italy. Castel Volturno in Campania is considered the headquarters of the Nigerian mafia in Europe.[83] The country is used as a hub by the Nigerian mafia for the trafficking of cocaine from South America, heroin from Asia and women from Africa. Nigerian gangs have established partnerships with local organised crime groups and have adopted the structure and operational methods of Italian crime syndicates.[84] The Nigerian mafia pays tribute (a percentage of its profits from criminal rackets) to the Camorra and Sicilian Mafia.[85] In Palermo, a group of drug dealers linked to the Neo-Black Movement were convicted as members of a "mafialike organization" in 2018.[86]

In January 2025, the Italian police dismantled a drug trafficking scheme between a Nigerian crime group and the historic Capriati clan in the city of Bari in the region of Apulia. The alliance between the two organizations aimed to supply drugs to Capriati affiliates who sold it in the nightclubs of the zones of influence of the clan.[87]Romanian mafia

[edit]One of the most notorious aspects of the Romanian mafia in Italy is its involvement in human trafficking. Many women and children from Romania are trafficked into Italy, often subjected to sexual exploitation and forced into prostitution. These criminal networks play a significant role in the trafficking of women and minors into highly exploitative conditions.The Romanian mafia is also heavily involved in drug trafficking. Italy is a key point in the global drug trade, and Romanian groups act as intermediaries in the distribution of substances such as cocaine and heroin. They have established networks within Italy, working alongside other Italian criminal organizations to control the flow of drugs across the country. Additionally, Romanian crime groups are involved in thefts and robberies. Thefts can range from breaking into homes and cars to stealing valuable goods like jewelry. Robbery is often a major income source for these criminal groups, who use the profits to further fund their operations.[88]

Extortion is another key activity of the Romanian mafia in Italy. They target local businesses and sometimes even other Romanian immigrants, coercing them into paying for "protection." Those who resist or refuse to comply may face violent repercussions, reinforcing the mafia's control over certain territories. Romanian crime groups operates in a decentralized manner in Italy, with various cells or factions working independently, but still maintaining links to one another.[89]

Violence is a common tool used by these groups to intimidate victims, enforce control, and establish dominance over certain areas. While they may not have the same level of public visibility or political influence as some of Italy's other criminal organizations, Romanian mafia groups still collaborate with other criminal entities, particularly when it comes to drug trafficking and sexual exploitation. The Italian authorities have made efforts to crack down on the Romanian mafia in recent years, launching more investigations and carrying out numerous arrests.[90][91]

In Italy, most of the Romanian criminals are involved in theft and pimping, however, in Turin, they created an Italian-style mafia within their local community, extorting money from Romanian night-clubs that ran prostitutes, and would impose their own businesses and singers on weddings by force.[92]

Also in Turin, Romanian criminals created the 'Brigada Oarza' group, specialized in extortion, robbery and drug trafficking. In 2014, 15 members of the Brigada Oarza were convicted of mafia affiliation, being sentenced up to 15 years in prison. It was the first Italian sentence that condemned a group of Romanian people for mafia-style criminal association.[93] The leader of the Brigada Oarza was allegedly the former professional boxer Viorel Lovu.[94]Chinese triads

[edit]According to the expert on terrorist organizations and mafia-type organized crime Antonio De Bonis, there is a close relationship between the Triad and the Camorra and the Port of Naples is the most important landing point for the activities managed by the Chinese groups in cooperation with the camorra. Among the illegal activities in which the two criminal organizations work together are human trafficking and illegal immigration aimed at the sexual and labor exploitation of Chinese people on Italian territory, drug trafficking and the laundering of illicit capital through the purchase of real estate, commercial establishments and businesses.[95]

In 2017, investigators uncovered a plan between the Camorra and Chinese gangs: these exported industrial waste from Italy to China which guaranteed revenues of millions of euros for both organizations. Industrial waste left Prato and arrived in Hong Kong. Among the clans involved in this alliance were the Casalesi clan, the Fabbrocino clan and the Ascione clan.[96]

In 2018, Naizhong Zhang, a 58-year-old Chinese crime boss, was arrested in Rome for leading a powerful criminal organization that dominated Chinese goods transportation across much of Europe through violence and extortion. Based in Prato, where 50,000 Chinese nationals reside, Zhang imposed control over rival gangs after a deadly turf war and expanded into illegal activities such as gambling, drug trafficking, counterfeiting, and money lending. Authorities, led by the Florence anti-mafia unit, issued 33 arrest warrants and investigated 54 other individuals as part of the "China Truck" operation that began in 2011. Zhang flaunted his power with luxury cars, extravagant weddings, and public shows of respect from followers. His organization also operated illegal gambling dens in bars, brothels disguised as massage parlors, and invested criminal profits into ambitious projects, including purchasing part of a coal mine in China. Zhang was arrested along with his secretary and lover, Chen Xiaomian, who was found with €30,000 in cash.[97]

Zhang Dayong, known as Asheng, was executed in Rome, in April 2025, with a gunshot to the head and three to the chest. He was the right-hand man of Naizhong Zhang, the alleged head of the Chinese mafia in Europe, and served as his representative in Rome. Zhang Dayong had a history of violent offenses and was considered a key player in the organization's illegal activities in Italy, including loan sharking and running underground gambling operations. Although he officially ran a store in Rome's Esquilino neighbourhood, Asheng was in charge of the Chinese mafia's operations in the Italian capital. Investigators link him to past violence, including the enforcement of payments through beatings. He was also present at the lavish 2013 wedding of Zhang Naizhong's son, attended by major figures in the Chinese criminal underworld. Asheng reportedly lost favor within the organization after several missteps, including getting drunk and assaulting women at a brothel managed by a fellow gang member. Intercepted conversations reveal how his disrespect toward superiors and erratic behavior eventually sealed his fate. His murder is believed to be connected to the ongoing turf war among Chinese gangs, known as the "hanger war" of Prato, which has now spread to Rome. His death marks a significant escalation in the mafia conflict.[98]

Fight against organized crime in Italy

[edit]

In order to combat the phenomenon more effectively, some legislative measures on the subject began to be created starting from the 1980s, such as the introduction of the crimes of mafia-type association and political-mafia electoral exchange, of a special prison regime, with the introduction of article 41 bis in the law on the Italian penitentiary system, international judicial cooperation[99] and the creation of some ad hoc bodies such as the High Commissioner for the coordination of the fight against mafia delinquency (later abolished). In the 1990s, due to the work of some Italian magistrates such as Giovanni Falcone, Paolo Borsellino and Antonino Caponnetto, the Direzione Investigativa Antimafia and the Direzione Nazionale Antimafia e Antiterrorismo were created. Many of the provisions on the matter were then collected in Legislative Decree no. 59 of 6 September 2011.

The Antimafia Pool was a group of investigating magistrates at the Prosecuting Office of Palermo (Sicily) who closely worked together sharing information and developing new investigative and prosecutorial strategies against the Sicilian Mafia. An informal pool had been created by Judge Rocco Chinnici in the early 1980s following the example of anti-terrorism judges in Northern Italy in the 1970s.[100] Most important, they assumed collective responsibility for carrying Mafia prosecutions forward: all the members of the pool signed prosecutorial orders to avoid exposing any one of them to particular risk, such as the one that had cost Judge Gaetano Costa his life. Costa had signed the indictments of 55 against the Mafia heroin-trafficking network of the Spatola-Inzerillo-Gambino clan after virtually all of the other prosecutors in his office had declined to do so – a fact that leaked out of the office and eventually cost him his life. He was murdered on 6 August 1980, on the orders of Salvatore Inzerillo.[101] In July 1983, Rocco Chinnici was killed by the Mafia. His place as head of the ‘Office of Instruction’ (Ufficio istruzione), the investigative branch of the Prosecution Office of Palermo, was taken by Antonino Caponnetto, who formalized the pool. Next to Giovanni Falcone, the group included Paolo Borsellino, Giuseppe Di Lello and Leonardo Guarnotta.[101][102] The group subsequently pooled together several investigations into the Mafia, which would result in the Maxi Trial against the Mafia starting in February 1986 and which lasted until December 1987.

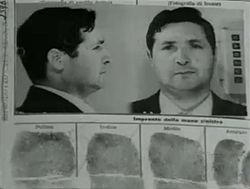

The Maxi Trial (Italian: Maxiprocesso) was a criminal trial against the Sicilian Mafia that took place in Palermo, Sicily. The trial lasted from 10 February 1986 (the first day of the Corte d'Assise) to 30 January 1992 (the final day of the Supreme Court of Cassation), and was held in a bunker-style courthouse specially constructed for this purpose inside the walls of the Ucciardone prison. Sicilian prosecutors indicted 475 mafiosi for a multitude of crimes relating to Mafia activities, based primarily on testimonies given as evidence from former Mafia bosses turned informants, known as pentiti, in particular Tommaso Buscetta and Salvatore Contorno. Most were convicted, 338 people, sentenced to a total of 2,665 years, not including life sentences handed to 19 bosses; the convictions were upheld on 30 January 1992 by the Supreme Court of Italy, after the final stage of appeal. The importance of the trial was that the existence of Cosa Nostra was finally judicially confirmed.[101] It is considered to be the most significant trial ever against the Sicilian Mafia, as well as the largest trial in world history.[103] Throughout and after the trial, several judges and magistrates were killed by the Mafia, including the two who led it—Giovanni Falcone and Paolo Borsellino.

The Spartacus Trial (Italian: Processo Spartacus) was a series of criminal trials, each specifically directed against the activities of the powerful Casalesi clan of the Camorra. The trial was opened at the Corte d'Assise of Santa Maria Capua Vetere in Caserta. It was named after the historical gladiator, Spartacus, who led a rebellion of slaves beginning in old Capua against the ancient Roman Empire. The trial was initially chaired by its president, Catello Marano on 1 July 1998. It continued just over ten years, until its final verdict was eventually read on 19 June 2008.[104][105] In that 10-year legal trial, 36 members of the clan were charged with a string of murders and other crimes. The Casalesi clan had exploited and extorted from every business and economic opportunity, from waste disposal to construction, in creating a monopoly in the cement market for their own building businesses to the distribution of materials. Building business would have to pay for the contracts, buy material from the clan, and keep paying for protection. The clan also controlled elections.[106] More than 1,300 people were investigated, 508 witnesses gave evidence and 626 were interviewed in the trial which saw the heaviest penalties ever for organised crime with a total of 700 years of imprisonment. Over the course of the initial trial and the appeal, five people involved in the case were murdered, including a court interpreter. A judge and two journalists were threatened with death.[106][107] In all, 115 people were prosecuted, 27 life sentences, plus 750 years in prison were handed out to the defendants. On 15 January 2010, Italy's Supreme Court confirmed the sentence.[108][109]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ ""In Puglia effervescenza criminale tra mafia foggiana, criminalità barese e sacra corona unita"". Corriere della Sera (in Italian). 13 April 2023. Archived from the original on 5 February 2024. Retrieved 21 March 2024.

- ^ "Impatto della criminalità organizzata sul territorio laziale". Rivista Antiriciclaggio & Compliance (in Italian). 11 October 2023. Archived from the original on 22 March 2024. Retrieved 22 March 2024.

- ^ a b "La Procura spiega il sistema-Roma: "È la 'Mafia Capitale', romana e originale"". Rainews.it. Rai - Radiotelevisione Italiana. 2 December 2014. Archived from the original on 25 October 2023. Retrieved 17 June 2015.

- ^ "Direzione Investigativa Antimafia". direzioneinvestigativaantimafia.interno.gov.it. Archived from the original on 15 February 2019. Retrieved 31 May 2020.

- ^ Kiefer, Peter (22 October 2007). "Mafia crime is 7% of GDP in Italy, group reports". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 1 May 2011. Retrieved 19 April 2011.

- ^ Claudio Tucci (11 November 2008). "Confesercenti, la crisi economica rende ancor più pericolosa la mafia". Confesercenti (in Italian). Ilsole24ore.com. Archived from the original on 27 April 2011. Retrieved 21 April 2011.

- ^ Nick Squires (9 January 2010). "Italy claims finally defeating the mafia". The Daily Telegraph. Archived from the original on 29 April 2011. Retrieved 21 April 2011.

- ^ Maria Loi (1 October 2009). "Rapporto Censis: 13 milioni di italiani convivono con la mafia". Censis (in Italian). Antimafia Duemila. Archived from the original on 29 April 2011. Retrieved 21 April 2011.

- ^ Kington, Tom (1 October 2009). "Mafia's influence hovers over 13 m Italians, says report". The Guardian. London. Archived from the original on 8 September 2013. Retrieved 5 May 2010.

- ^ "Crime Statistics – Murders (per capita) (more recent) by country". NationMaster.com. Archived from the original on 29 September 2008. Retrieved 4 April 2010.

- ^ This etymology is based on the books Mafioso by Gaia Servadio, The Sicilian Mafia by Diego Gambetta, and Cosa Nostra by John Dickie.

- ^ Gambetta, Diego (1996) [1993]. The Sicilian Mafia: The Business of Private Protection. Princeton University Press. ISBN 0-674-80742-1.

- ^ HachetteAustralia (9 February 2011). "John Dickie on Blood Brotherhoods". YouTube. Archived from the original on 15 February 2013. Retrieved 11 December 2011.

- ^ Jason Sardell, Economic Origins of the Mafia and Patronage System in Sicily Archived 2011-07-20 at the Wayback Machine, 2009.

- ^ Oriana Bandiera (2002). "Private States and the Enforcement of Property Rights – Theory and Evidence on the Origins of the Sicilian Mafia," CEPR Discussion Papers 3123, C.E.P.R. Discussion Papers. Archived 2012-03-19 at the Wayback Machine, 2001, pp. 8–10

- ^ Dickie, John (2007). Cosa Nostra: A History of the Sicilian Mafia. Hodder. p. 39. ISBN 978-0-340-93526-2.

- ^ Paoli, Letizia (2003). Mafia Brotherhoods: Organized Crime, Italian Style. New York: Oxford University Press. p. 161. ISBN 0-19-515724-9.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: publisher location (link) - ^ Arlacchi. Men of Dishonour. p. 119

- ^ a b "FBI – Italian Organized Crime". Archived from the original on 7 October 2010. Retrieved 28 July 2016.

- ^ "Museum of Learning -- Mafia: Current Clans". Archived from the original on 11 January 2012. Retrieved 23 August 2010.

- ^ Santana, Jen (19 July 2013). "Italian Police Make Over 100 Arrests in Massive Mafia Bust". Interpacket. Archived from the original on 24 December 2013. Retrieved 23 December 2013.

- ^ Montanelli, Indro; Gervaso, Roberto (1969). L'Italia del Seicento. (1600-1700) (in Italian). Rizzoli. ISBN 9788817420112. Archived from the original on 6 May 2024. Retrieved 3 October 2020.

- ^ Schumpeter (column) (27 August 2016). "Mafia management". The Economist. Archived from the original on 8 September 2017. Retrieved 31 January 2017.

- ^ Farano, Adriano (16 October 2007). "Roberto Saviano: Spain in mafia hands". Cafébabel. Archived from the original on 1 October 2019. Retrieved 31 May 2020.

- ^ Mangione, Antonio (15 September 2023). "La mappa della camorra a Napoli, 2 grandi clan e tanti gruppi piccoli gruppi criminali si dividono la città". Internapoli.it (in Italian). Archived from the original on 13 October 2023. Retrieved 6 May 2024.

- ^ a b John Hooper, John Hooper on the Calabrian Mob that really runs Italy Archived 1 December 2016 at the Wayback Machine, The Guardian, 8 Jun 2006

- ^ Italian Organised Crime: Threat Assessment Archived 22 July 2016 at the Wayback Machine, Europol, The Hague, June 2013

- ^ Le criminalità organizzate nell'Italia meridionale continentale: camorra, 'ndrangheta, sacra corona unita Carlo Alfiero, Generale di Brigata - Comandante Scuola Ufficiali CC

- ^ "Puglia crimewave points to emergence of 'fifth' Italian mafia | World news | The Guardian". TheGuardian.com. 19 May 2020. Archived from the original on 31 May 2020.

- ^ "La Mafia di Foggia è la "nuova Gomorra"". Panorama (in Italian). 9 May 2019. Archived from the original on 9 August 2020. Retrieved 31 May 2020.

- ^ Civillini, Matteo (21 March 2016). "Come la Società Foggiana è diventata la mafia più brutale e sanguinosa d'Italia". Vice (in Italian). Archived from the original on 12 June 2020. Retrieved 31 May 2020.

- ^ Lorenzo Tondo (19 May 2020). "Puglia crimewave points to emergence of 'fifth' Italian mafia". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 31 May 2020. Retrieved 31 May 2020.

- ^ Tondo, Lorenzo (19 May 2020). "Puglia crimewave points to emergence of 'fifth' Italian mafia". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Archived from the original on 31 May 2020. Retrieved 31 May 2020.

- ^ "Il ruolo della 'Società Foggiana' su San Severo, dove è guerra aperta tra clan per la conquista del business della droga". FoggiaToday (in Italian). Archived from the original on 19 January 2020. Retrieved 31 May 2020.

- ^ Ondaradio, Redazione. "I tre clan in guerra ma con il direttorio. Per il controllo di cassa comune e lista estorsioni. La nuova relazione dell'antimafia (4) - Rete Gargano". www.retegargano.it (in Italian). Retrieved 31 May 2020.[permanent dead link]

- ^ "I tentacoli dei clan baresi nella vita della città, don Angelo Cassano: "Organizzazioni criminali diventate potenza economica"". BariToday (in Italian). Retrieved 21 March 2024.

- ^ "Il clan Parisi torna in cella - la Repubblica.it". Archivio - la Repubblica.it (in Italian). 24 September 2008. Archived from the original on 21 March 2024. Retrieved 21 March 2024.

- ^ "Associazione mafiosa, traffico di droga, armi ed estorsioni: 121 condanne per il clan Strisciuglio". BariToday (in Italian). Archived from the original on 28 January 2023. Retrieved 21 March 2024.

- ^ "Bari, fra i clan della città vecchia equilibri a rischio dopo l'assoluzione di Filippo Capriati". la Repubblica (in Italian). 11 September 2022. Archived from the original on 25 January 2024. Retrieved 21 March 2024.

- ^ Francklin, Eleonora (14 September 2023). "Conflitti tra clan per il controllo del territorio, dall'ascesa dei Parisi allo stato di fibrillazione degli Strisciuglio: la mappa criminale di Bari". Quinto Potere (in Italian). Archived from the original on 21 March 2024. Retrieved 21 March 2024.

- ^ "casamonica". tg24.sky.it. tg24.sky.it. 19 November 2025. Retrieved 19 November 2025.

- ^ "Mafia a Roma, più di 40 condanne al clan Casamonica". tg24.sky.it. tg24.sky.it. 20 September 2021. Retrieved 19 November 2025.

- ^ "Mafia: indagine su clan Casamonica, 7 condanne definitive". ansa.it. ansa.it. 29 November 2024. Retrieved 19 November 2025.

- ^ a b Sergi, Anna. "Fifth Column: Italy's Fifth Mafia, the Basilischi". Archived from the original on 2 November 2023. Retrieved 2 December 2017.

- ^ "Mafia capitale, il libro mastro del clan di Carminati e i "doppi" stipendi dei politici". Rainews.it. Rai - Radiotelevisione Italiana. 4 December 2014. Archived from the original on 17 June 2015. Retrieved 17 June 2015.

- ^ "Notte Criminale". Archived from the original on 8 March 2011. Retrieved 10 July 2017.

- ^ Blumenthal, Ralph (28 July 1988). "Acquitted in 'Pizza Connection' Trial, Man Remains in Prison". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on 2 May 2019. Retrieved 31 May 2020.

- ^ a b "Organized Crime". Federal Bureau of Investigation. Archived from the original on 29 March 2019. Retrieved 31 May 2020.

- ^ Giuffrida, Angela (30 October 2019). "Italy mafia networks are more complex and powerful, says minister". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Archived from the original on 20 May 2020. Retrieved 31 May 2020.

- ^ Grossi, Luca (4 August 2022). "L'Olanda: una narco-colonia della 'Ndrangheta a nord dell'Europa". Antimafia Duemila | Fondatore Giorgio Bongiovanni (in Italian). Archived from the original on 6 June 2023. Retrieved 10 April 2024.

- ^ "Gratteri: "La Germania è il secondo Paese con la più alta presenza di 'ndrangheta. Nessuno fa nulla, i clan portano soldi e aiutano il pil"". Il Fatto Quotidiano (in Italian). 1 February 2024. Archived from the original on 13 February 2024. Retrieved 10 April 2024.

- ^ "La frontiera belga della 'ndrangheta. "Qui appoggi familiari e lo snodo per il narcotraffico"". Corriere della Calabria (in Italian). 4 May 2023. Archived from the original on 16 May 2023. Retrieved 10 April 2024.

- ^ "Mafia nel Regno unito: la relazione della Dia | Il Tacco d'Italia" (in Italian). 15 April 2020. Archived from the original on 4 June 2020. Retrieved 4 June 2020.

- ^ Civillini, Matteo; Anesi, Cecilia; Rubino, Giulio. "How the Camorra Went Global". www.occrp.org. Archived from the original on 3 June 2020. Retrieved 4 June 2020.

- ^ Redazione (31 December 2023). "Camorra, arrestato in Spagna boss del clan Contini: era in fuga da tre mesi". Anteprima24.it (in Italian). Archived from the original on 21 March 2024. Retrieved 21 March 2024.

- ^ "CrimiNapoli / 28: come la Spagna divenne rifugio dei clan di camorra". www.ilmattino.it (in Italian). 30 April 2022. Archived from the original on 21 March 2024. Retrieved 21 March 2024.

- ^ "Huge seizure of 'Ndrangheta drugs from Colombia". www.italianinsider.it. Archived from the original on 16 February 2021. Retrieved 31 May 2020.

- ^ Tondo, Lorenzo (8 July 2019). "One of Italy's top drug dealers arrested in Brazil after five years on the run". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Archived from the original on 12 June 2020. Retrieved 31 May 2020.

- ^ Tp24.it (14 October 2023). "Le mafie straniere in Italia. Ecco le più pericolose e cosa fanno". TP24.it (in Italian). Archived from the original on 6 May 2024. Retrieved 10 April 2024.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ Varese, Federico (2013). "The Structure and the Content of Criminal Connections: The Russian Mafia in Italy". European Sociological Review. 29 (5): 899–909. doi:10.1093/esr/jcs067. ISSN 0266-7215. JSTOR 24479836. Archived from the original on 11 March 2023. Retrieved 11 March 2023.

- ^ Vergine (info.nodes), Davide Del Monte, Gloria Riva and Stefano. "Murder, Drugs and Extortion in Tuscany's Chinese Underworld". OCCRP. Archived from the original on 11 March 2023. Retrieved 11 March 2023.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "'You can't tell people a place like this exists in Italy. No-one would believe it'". ABC News. 16 March 2020. Archived from the original on 11 March 2023. Retrieved 11 March 2023.

- ^ "Milano, ricostruirono banda dei Latin King: 9 condanne. Due anni all' 'Inca Supremo'. Pena più alta a 3 anni e 4 mesi". la Repubblica (in Italian). 2 October 2023. Archived from the original on 8 October 2023. Retrieved 10 April 2024.

- ^ Redazione (31 May 2019). "Mafia albanese consolida "business" droga in Basso Molise. Parla Musacchio dell'Osservatorio Antimafia Molise". myNews Termoli e Molise (in Italian). Archived from the original on 6 May 2024. Retrieved 10 April 2024.

- ^ "Arrestati 13 membri di un sodalizio albanese di Modena per spaccio di cocaina: maxi-operazione internazionale". notizie.virgilio.it (in Italian). 9 April 2024. Archived from the original on 9 April 2024. Retrieved 10 April 2024.

- ^ "The growing Albanian Mafia: from the risk of area to the great alliaces". Gnosis.aisi.gov.it. Archived from the original on 26 October 2014. Retrieved 26 October 2014.

- ^ ""Infitrazioni consolidate", il report della DIA. A Modena organizzazioni nigeriane e albanesi". ModenaToday (in Italian). Retrieved 10 April 2024.

- ^ "Livigno e Bormio, spacciavano cocaina sulle piste da sci: sgominata banda legata alla mafia albanese". Corriere della Sera (in Italian). 14 March 2024. Retrieved 10 April 2024.

- ^ "La piazza di spaccio dei Castelli contesa tra italiani e albanesi". RomaToday (in Italian). Retrieved 9 April 2024.

- ^ "Gomorra albanese: condannato il boss che si proclamava "Dio". A lui 18 anni, 16 al rivale". RomaToday (in Italian). Retrieved 9 April 2024.

- ^ "Tonnellate di droga e armi da guerra sui gommoni tra Puglia e Albania, 20 arresti. In manette anche "Lo Zio" e "Piripicchio" - l'Immediato" (in Italian). 12 December 2019. Retrieved 10 April 2024.

- ^ "Trafficava eroina fra Bari e l'Albania. Arrestato latitante a Trieste". BariViva (in Italian). 6 December 2019. Retrieved 10 April 2024.

- ^ "Trafficante di droga ricercato da 4 anni, era Austria con passaporto falso: preso latitante, fiumi di eroina dall'Albania alla Puglia". BariToday (in Italian). Retrieved 10 April 2024.

- ^ admin (6 May 2022). "Historia e 3 "zotave" shqiptarë të drogës në Romë, çfarë e veçon Elvis Demçen". Albeu.com. Retrieved 5 March 2025.

- ^ "Narcotraffico, sulla piazza coca ed eroina valevano 10 milioni di euro". Tusciaweb.eu (in Italian). 29 November 2018. Retrieved 6 March 2025.

- ^ "Processo "Alba Bianca", la cocaina "affidata" al gatto". www.latinaoggi.eu (in Italian). 17 April 2024. Retrieved 5 March 2025.

- ^ Bodrero, Lorenzo (18 January 2023). "Così i narcos albanesi fanno affari con le organizzazioni criminali che dominano Roma". IrpiMedia (in Italian). Retrieved 5 March 2025.

- ^ "Armi e droga dall'Albania, venti arresti a Bari Vecchia". Corriere della Sera (in Italian). 12 December 2019. Retrieved 5 March 2025.

- ^ "Armë dhe drogë nga Shqipëria, sekuestrohet mbi një milion euro pasuri në Bari/ Arrestohen 20 persona mes tyre bosi shqiptar/ EMRAT". www.panorama.com.al (in Albanian). 6 March 2025. Retrieved 6 March 2025.

- ^ Verona, Cronaca di (3 July 2025). "Un clan albanese con le mani su Verona". La Cronaca di Verona (in Italian). Retrieved 15 October 2025.

- ^ Piovesan, Alessia (3 July 2025). Verona, soldi del narcotraffico reinvestiti nel mercato immobiliare dalla mafia albanese (in Italian). Retrieved 15 October 2025 – via www.rainews.it.

- ^ Stoppele, Luca. "Mafia albanese, soldi riciclati del narcotraffico investiti nel Veronese: due immobili sequestrati". VeronaSera (in Italian). Retrieved 15 October 2025.

- ^ In a ruined city on the Italian coast, the Nigerian mafia is muscling in on the old mob Emma Alberici and Giulia Sirignani, ABC News (16 March 2020)

- ^ Migration of the Nigerian mafia Carla Bernardo, University of Cape Town (16 May 2017)

- ^ A foreign mafia has come to Italy and further polarized the migration debate Chico Harlan and Stefano Pitrelli, The Washington Post (25 June 2019)

- ^ ""The Black Axe" - investigation on the Neo-Black Movement´s international activities". Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung. 17 August 2020.

- ^ "Bari, la droga del clan nigeriano viaggiava sui pullman, arrivava nei b&b e anche nel Cara di Palese". la Repubblica (in Italian). 30 January 2025. Retrieved 1 February 2025.

- ^ "Clan mafiot românesc, înființat în Italia. Infracțiunile pentru care au fost arestați 18 conaționali". Știrile ProTV (in Romanian). Retrieved 7 March 2025.

- ^ "Cum a băgat spaima în italieni brigada interlopilor români din Torino. Și albanezii fugeau de ei". Newsweek Romania. 27 March 2023. Retrieved 7 March 2025.

- ^ "Italia, tara Cosa Nostra, invadata de mafia romaneasca". Ziare.com (in Romanian). Retrieved 7 March 2025.

- ^ "Românca din Italia care a înfruntat mafia, premiată de Ambasada României". romania-actualitati.ro (in Romanian). Retrieved 7 March 2025.

- ^ "Expat Romanians: their own worst enemy". theblacksea.eu. Retrieved 1 November 2019.

- ^ "Torino, 15 romeni condannati per mafia: la prima volta in Italia". Corriere della Sera (in Italian). 27 October 2014. Retrieved 1 November 2019.

- ^ "FOTO VIDEO Il capo di tutti capi. Povestea boxerului român care conducea un clan de mafioţi din puşcărie". adevarul.ro. 22 June 2013. Retrieved 30 August 2020.

- ^ "Così la mafia cinese se la intende con la camorra". www.ilfoglio.it (in Italian). Archived from the original on 23 November 2020. Retrieved 10 April 2024.

- ^ TG24, Sky (26 April 2017). "Rifiuti, scoperto un traffico di plastica da Prato a Hong Kong". tg24.sky.it (in Italian). Archived from the original on 18 September 2020. Retrieved 10 April 2024.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ "Il capo dei capi della mafia cinese finisce in manette: affari in tutta l'Ue". ilGiornale.it (in Italian). 19 January 2018. Retrieved 16 April 2025.

- ^ "Zhang Dayong, re delle bische e braccio destro dell'Uomo nero: chi era il boss ucciso al Pigneto". la Repubblica (in Italian). 16 April 2025. Retrieved 16 April 2025.

- ^ Italy seeks worldwide help in war on Mafia. John Phillips. The Times (London, England), Wednesday, 29 July 1992; pg. 8; Issue 64397.

- ^ Jamieson, The Antimafia, p. 29

- ^ a b c Giovanni Falcone, Paolo Borsellino and the Procura of Palermo Archived 21 October 2012 at the Wayback Machine, Peter Schneider & Jane Schneider, May 2002, essay is based on excerpts from Chapter Six of Jane Schneider and Peter Schneider, Reversible Destiny: Mafia, Antimafia and the Struggle for Palermo, Berkeley: U. of California Press

- ^ Stille, Excellent Cadavers, pp. 85-90

- ^ Alfonso Giordano, Il maxiprocesso venticinque anni dopo – Memoriale del presidente, p. 68, Bonanno Editore, 2011. ISBN 978-88-7796-845-6

- ^ (in Italian) Il maxiprocesso Spartacus e il silenzio della stampa Archived 9 January 2010 at the Wayback Machine, Cuntrastamu, 30 September 2005

- ^ (in Italian) «Processo Spartacus», 16 ergastoli ai Casalesi Archived 3 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine, Corriere del Mezzogiorno, 20 June 2008

- ^ a b Camorra get terms they can't refuse Archived 16 February 2017 at the Wayback Machine, Sydney Morning Herald, 21 June 2008

- ^ Godfathers of €25bn mafia family get life after epic trial Archived 20 May 2011 at the Wayback Machine, The Independent, 20 June 2008

- ^ (in Italian) La Cassazione conferma le condanne al clan dei Casalesi Archived 26 December 2023 at the Wayback Machine, Corriere della Sera, 15 January 2010

- ^ (in Italian) La Cassazione conferma la sentenza: Sedici ergastoli contro i Casalesi Archived 25 April 2024 at the Wayback Machine, La Repubblica, 15 January 2010

Organized crime in Italy

View on GrokipediaHistorical Development

Origins in Southern Italian Societies

Organized crime in southern Italy arose from the interplay of weak governance, economic structures favoring large estates, and social reliance on private enforcement in regions like Sicily, Calabria, and Campania, where central authority was historically limited under foreign dominions and the Bourbon Kingdom of the Two Sicilies until unification in 1861. Pre-unification feudalism concentrated land in absentee owners' hands, fostering banditry, vendettas, and informal power brokers to resolve disputes absent reliable public justice.[5] The 1812 abolition of feudal privileges intensified these dynamics by fragmenting property rights without bolstering state capacity, creating demand for protection against theft in vulnerable agrarian economies. In Sicily, proto-mafia groups coalesced in the mid-19th century around gabellotti—estate managers who enforced contracts and guarded against predation in the absence of state policing, particularly for theft-prone citrus groves and sulfur mines that boomed post-feudal reform.[5] These actors monetized protection services in areas of high land inequality and cereal suitability, where extortion was feasible due to perishable goods requiring credible enforcement amid interpersonal distrust.[6] Empirical mapping from 1902–1909 data traces mafia footholds to western Sicily's plains, where weak coastal state presence and economic opportunities enabled syndicates to supplant feudal intermediaries, evolving into hierarchical cosche by the late 1800s.[6] Calabria's 'ndrangheta emerged from rural picciotterie—informal youth associations in isolated mountain hamlets enforcing honor codes and retaliatory justice amid chronic poverty and minimal Bourbon oversight, solidifying post-1861 as unification failed to extend effective rule.[7] In Campania, the Camorra took shape in the early 19th century within Naples' prisons and slums, where lower-class sects controlled urban rackets like smuggling and gambling, capitalizing on the kingdom's overcrowded ports and lax enforcement to form initiatory brotherhoods predating formal unification.[3] Across these societies, kinship ties and omertà-like silences reinforced group loyalty, but structural voids in property defense and dispute resolution—rather than inherent cultural pathologies—drove the shift from ad hoc vigilantism to enduring criminal enterprises.Formation and Consolidation Post-Unification

Following Italy's unification in 1861, the central government's limited administrative reach in the rural south enabled pre-existing informal networks of bandits, private guards, and secret societies to consolidate into hierarchical criminal syndicates, filling the void left by ineffective policing and land reforms that disrupted traditional feudal protections without establishing reliable alternatives. In regions like Sicily and Calabria, where agricultural productivity was low and land inequality high, these groups imposed private order through extortion rackets and arbitration, often aligning with local elites to control resources such as citrus groves and sulfur mines. Economic analyses of 1880s data indicate that Mafia-type organizations correlated positively with areas of weak state capacity and agrarian disputes, evolving from ad hoc protection services into enduring clans that infiltrated municipal governance and electoral processes.[8] In Sicily, the proto-Mafia—rooted in gabelloti (middlemen leaseholders) and armed campieri (field guards)—gained traction by the 1870s, dominating the lemon export trade in Palermo province through coercive intermediation, where mafiosi ensured shipment to ports in exchange for fees, leveraging violence to resolve disputes amid absent judicial enforcement. Official reports from the era, including prefectural inquiries, documented the Mafia's emergence as a distinct entity around 1865, characterized by oaths of loyalty and codes of silence that distinguished it from mere banditry, which had peaked during the 1861–1865 post-unification uprisings. By the 1880s, these syndicates extended influence into politics, rigging votes for aligned candidates and suppressing peasant leagues, thereby embedding themselves in the social fabric of western Sicily while the state focused repression on transient brigands rather than entrenched networks. Parallel developments occurred in Campania, where the Camorra, originating from Neapolitan prison sects prior to unification, reorganized post-1861 amid urban poverty and government purges, shifting from loose gambling rings to structured extortion of construction and markets in Naples. Repressive campaigns, such as the 1870s manhunts, temporarily fragmented the group, but incomplete eradication allowed clans to rebound by allying with corrupt officials, as revealed in the 1900–1901 Saredo Commission inquiry documenting systemic infiltration of public contracts. In Calabria, the 'Ndrangheta coalesced in the late 19th century from rural honor-based picciotterie (youth gangs) and ex-prisoner networks, capitalizing on isolation and family ties to monopolize smuggling and feud mediation, with early structures evident by the 1880s in Reggio Calabria province.[9][7] These syndicates' consolidation was abetted by the south's cultural and institutional distance from northern-imposed laws, fostering resistance manifested as brigandage and criminal entrenchment, with quantitative studies linking higher organized crime prevalence to communes exhibiting lower tax compliance and judicial efficacy in the decades following 1861. Unlike transient banditry, which declined after military crackdowns, Mafia groups endured by adapting to economic niches, such as Sicily's export booms, and avoiding direct state confrontation through omertà and elite complicity, setting the stage for 20th-century expansion.[10]20th-Century Expansion and Global Reach

During the post-World War II period, Italian organized crime groups capitalized on Italy's economic reconstruction, infiltrating sectors like construction and public contracts, which facilitated capital accumulation for further expansion. The Sicilian Cosa Nostra, for instance, leveraged alliances with American counterparts to import and refine heroin from Turkey, establishing Sicily as a key processing hub by the 1970s after the dismantling of the French Connection routes. This heroin trade generated substantial revenues, with the "Pizza Connection" network alone facilitating the importation of approximately 1,650 kilograms of heroin into the United States between 1979 and 1984, valued at around $1.6 billion wholesale.[11] The operation involved Sicilian clans transporting refined heroin via couriers and laundering proceeds through pizzerias and other businesses in North America, marking a peak in Cosa Nostra's transatlantic reach before intensified law enforcement responses.[11] [12] The Calabrian 'Ndrangheta underwent significant territorial and international growth from the 1950s onward, driven by mass emigration from Calabria to northern Italy, Germany, Australia, and Canada, where kin-based networks formed "locali" (branches) that mirrored the group's familial structure. By the late 20th century, these diaspora communities enabled the 'Ndrangheta to dominate cocaine importation from South America, controlling key European ports like Gioia Tauro for transshipment and collaborating with Colombian cartels, which positioned it as a primary supplier to markets in Europe and beyond.[1] This expansion was underpinned by the group's cohesion through blood ties, allowing it to avoid the informant betrayals that weakened rivals, and by the 1990s, it had supplanted Cosa Nostra in global drug revenues, estimated at billions annually from narcotics alone.[3] The Campanian Camorra, fragmented into clans but opportunistic, extended its reach internationally from the 1980s through drug trafficking partnerships, particularly in heroin and later cocaine, establishing footholds in Spain, the Netherlands, and the United Kingdom for distribution and money laundering via legitimate fronts like waste management firms. Post-war, Camorra bosses provided intelligence to Allied forces in 1943, gaining leverage that aided survival and adaptation, while by the 1980s, clans like the Casalesi group controlled smuggling routes into northern Europe, diversifying into counterfeiting and arms trade to sustain operations amid internal wars.[3] Overall, these groups' global footprint by century's end reflected adaptation to liberalization and globalization, with drug trafficking revenues comprising the bulk of their estimated $8.9 billion annual intake across major syndicates, though state crackdowns like Italy's Maxi Trial (1986–1992) curbed Cosa Nostra's dominance while 'Ndrangheta's lower profile enabled unchecked proliferation.[3]Major Italian Syndicates

Sicilian Cosa Nostra