Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Washington and Lee University

View on Wikipedia

Washington and Lee University (Washington and Lee or W&L) is a private liberal arts college in Lexington, Virginia, United States. Established in 1749 as Augusta Academy, it is among the oldest institutions of higher learning in the US.

Key Information

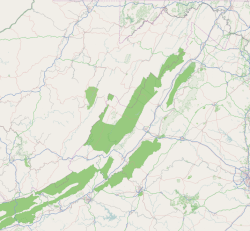

Washington and Lee's 325-acre campus sits at the edge of Lexington and abuts the campus of the Virginia Military Institute in the Shenandoah Valley region between the Blue Ridge Mountains and the Allegheny Mountains. The institution consists of three academic units: the college itself; the Williams School of Commerce, Economics, and Politics; and the School of Law. It hosts 24 intercollegiate varsity athletic teams which compete as part of the Old Dominion Athletic Conference of the National Collegiate Athletic Association (NCAA Division III).

History

[edit]The classical school from which Washington and Lee descended was established in 1749 by Scots-Irish Presbyterian pioneers and soon named Augusta Academy,[7] about 20 miles (32 km) north of its present location.[7] In 1776, it was renamed Liberty Hall in a burst of revolutionary fervor.[7] A number of prominent men from the area acted as its original trustees, including Andrew Lewis, Thomas Lewis, Sampson Mathews, Samuel McDowell, George Moffett, William Preston, and James Waddel.[8] The academy moved to Lexington in 1780, when it was chartered as Liberty Hall Academy, and built its first facility near town in 1782. The academy granted its first bachelor's degree in 1785.[7][9]

Liberty Hall is said to have admitted its first African American student when John Chavis, a free Black, enrolled in 1795.[10] Chavis accomplished much in his life including fighting in the American Revolution, studying at both Liberty Hall and the College of New Jersey (now Princeton University), becoming an ordained Presbyterian minister, and opening a school that instructed white and poor black students in North Carolina. He is believed to be the first black student to enroll in higher education in the United States, although he did not receive a degree.[11] Washington and Lee enrolled its next African American student in 1966 in the law school.

In 1796, George Washington endowed the academy with $20,000 in the form of 100 shares of James River Canal stock, at the time one of the largest gifts ever given to an educational institution in the United States. The shares were originally a gift given to Washington by the Virginia General Assembly.[12] Washington's gift continues to provide nearly $1.87 a year toward every student's tuition.[7] The gift rescued Liberty Hall from near-certain insolvency. In gratitude, the trustees changed the school's name to Washington Academy; in 1813 it was chartered as Washington College.[7] An 8-foot-tall (2.4 m) statue of George Washington, carved by Matthew Kahle and known as Old George, was placed atop Washington Hall on the historic Colonnade in 1844 in memory of Washington's gift. The current statue is made of bronze; the original wooden statue was restored and now resides in the library.[13]

The campus took its current architectural form in the 1820s when a local merchant, "Jockey" John Robinson, an uneducated Irish immigrant, donated funds to build a central building. For the dedication celebration in 1824, Robinson supplied a huge barrel of whiskey, which he intended for the dignitaries in attendance. But according to a contemporary history, the rabble broke through the barriers and created pandemonium, which ended only when college officials demolished the whiskey barrel with an axe. A justice of the Virginia State Supreme Court, Alex. M. Harman, Jr. ('44 Law), re-created the episode in 1976 for the dedication of the new law school building by having several barrels of Scotch imported (without the unfortunate dénouement). Robinson also left his estate to Washington College. The estate included between 70 and 80 enslaved people. Until 1852, the institution benefited from their enslaved labor and, in some cases, from their sale.[14] In 2014, Washington and Lee University joined such colleges as Harvard University, Brown University, the University of Virginia, and The College of William & Mary in researching, acknowledging, and publicly regretting their participation in the institution of slavery.[15][16]

During the Civil War, the students of Washington College raised the Confederate flag in support of Virginia's secession. The students formed the Liberty Hall Volunteers, as part of the Stonewall Brigade under Confederate States Army general Stonewall Jackson and marched from Lexington. Later in the war, during Hunter's Raid, Union Captain Henry A. du Pont refused to destroy the Colonnade due to its support of the statue of George Washington, Old George.[citation needed]

Lee years

[edit]

In the Fall of 1865, Robert E. Lee, the former general of the Confederacy, accepted an offer to become president of Washington College. Despite suffering financial hardship at the time and having offers for several business opportunities, he said he chose to become the college president because he wanted to train "young men to do their duty".[17] (Lee believed that the business offers were meant primarily to trade on his name). During his tenure, Lee established the first journalism courses (which were limited and only lasted several years)[18] and added engineering courses, a business school, and law school to the college curriculum, under the conviction that those occupations should be intimately and inextricably linked with the liberal arts. That was a radical idea: engineering, journalism, and law had always been considered technical crafts, not intellectual endeavors, and the study of business was viewed with skepticism.

Lee's emphasis on student self-governance for Washington College remains the distinguishing character of the student-run Honor System today. And, ardent about restoring national unity, he successfully recruited white men as students from throughout the reunited nation, North and South.

However, it has been argued that one of Lee's failings as president of Washington College was an apparent indifference to crimes of violence towards blacks committed by students at the college. Historian Elizabeth Brown Pryor notes that students at Washington College formed their own chapter of the KKK and were known by the local Freedmen's Bureau to attempt to abduct and rape black schoolgirls from the nearby black schools. There were also at least two attempted lynchings by Washington students during Lee's tenure. Yet Lee seemed to punish the racial harassment more laxly than he did more trivial offenses or turned a blind eye to it altogether.[19]

Lee died on October 12, 1870, after five years as Washington College president. The college's name was almost immediately changed to Washington and Lee University to honor Lee. On February 4, 1871, the name change was formalized by the Virginia General Assembly.[12] The university's motto, Nōn Incautus Futūrī', meaning "Not unmindful of the future", is an adaptation of the Lee family motto. Lee's son, George Washington Custis Lee, followed his father as the institution's president. Robert E. Lee and much of his family—including his wife, his seven children, and his parents, the Revolutionary War hero Major-General Henry "Light-Horse Harry" Lee and Anne Hill Carter Lee—are buried in University Chapel (formerly Lee Chapel) on campus, which faces the main row of antebellum college buildings. Robert E. Lee's beloved horse Traveller is buried outside, near the wall of the chapel.

20th century and beyond

[edit]After Lee's death, the institution continued his program of educational innovation, modernization, and expansion. In 1905, the board of trustees formally organized a School of Commerce in order to train students in business and finance alongside the college and the School of Law. In 1995, Ernest Williams II of the Class of 1938 endowed the School of Commerce which was renamed the Ernest Williams II School of Commerce, Economics, and Politics. Also in 1905, Andrew Carnegie donated $55,000 to the Washington and Lee for the erection of a new library.

Omicron Delta Kappa or ODK, a national honor society, was founded at Washington and Lee on December 3, 1914. For many years ODK's annual convocation was held at the school in University Chapel on or about Robert E. Lee's birthday, January 19, in conjunction with a board of trustees-mandated holiday/Lee commemoration called "Founders Day", a version of the Robert E. Lee Day birthday holiday still officially celebrated in a few southern states.[20] (The board of trustees announced the discontinuation of "Founders Day" on June 4, 2021.[21]) ODK Chapters, known as Circles, are located on over 300 college campuses. The society recognizes achievement in the five areas of scholarship; athletics; campus/community service, social/religious activities, and campus government; journalism, speech and the mass media; and creative and performing arts. ODK is a quasi-secret society with regard to the way in which its members are selected and kept secret for a period of time. Membership in the Omicron Delta Kappa Society is regarded as one of the highest collegiate honors that can be awarded to an individual, along with Phi Kappa Phi and Phi Beta Kappa. Some circles limit membership to less than the top one quarter of one percent of students on their respective campuses. Omicron Delta Kappa continues to maintain its headquarters in Lexington and is a major presence at W&L.

During the first half of the 20th century, the institution began its traditions of the Fancy Dress Ball and Mock Convention. Both of these are still staples of the W&L experience.

The second half of the 20th century saw Washington and Lee move from being an all-men's college to a co-ed institution. The School of Law enrolled its first women in 1972 and the undergraduate program enrolled its first woman in 1985. Washington and Lee built new buildings to house its science departments as well as a new School of Law facility. Further, W&L successfully completed several multimillion-dollar capital campaigns.

Among many alumni who have followed in George Washington's footsteps by donating generously, Rupert Johnson Jr., a 1962 graduate who is vice chairman of the $600 billion Franklin Templeton investment management firm, gave $100 million to Washington and Lee in June 2007, establishing a merit-based financial aid and curriculum-enrichment program.[7][22][23]

In 2014, a large Confederate battle flag and a number of related state flags were removed from University Chapel, after a group of black students protested that the school was unwelcoming to minorities. In his letter, President Kenneth P. Ruscio publicly apologized for the school's ownership of about 80 enslaved people during the period from 1826 to 1852, some of whom were forced to build a dormitory on campus.[24][25]

Some students, faculty, and alumni have advocated that Washington and Lee disassociate itself from Lee, including advocating a change of name. Other students and alumni have defended the association with Lee.[26] In July 2020, for the first time, faculty (by more than a three-quarters vote) and the executive committee of the Student Body called for Robert E. Lee's name to be removed from the name of the institution.[27] The board of trustees announced the formation of a committee to consider name-change, removing portraits of Lee from diplomas, and how names and symbols of Lee and confederates "uphold slavery" and "abhorrent racist sentiment."[28] On June 4, 2021, after 11 months of deliberation, the board voted 22–6 to keep the name.[29]

Campus

[edit]

Washington and Lee University Historic District | |

Washington College at Lexington, 1845 | |

| Location | Washington and Lee University campus, Lexington, Virginia |

|---|---|

| Built | 1824 |

| Architect | Jordan, John |

| Architectural style | Greek Revival, Neo-Classical |

| NRHP reference No. | 71001047[30] |

| VLR No. | 117-0022 |

| Significant dates | |

| Added to NRHP | November 11, 1971 |

| Designated NHLD | November 11, 1971 |

| Designated VLR | October 6, 1970[31] |

The central core of the campus, including the row of brick buildings that form the Colonnade, are a designated National Historic Landmark District for their architecture.[32] The University Chapel, separately designated a National Historic Landmark, is also a part of that district.[33]

In 1926, the poet and dramatist John Drinkwater, author of Robert E. Lee and other plays, wrote of W&L, "This Lexington university is one of the loveliest spots in the world."[34] Jonathan W. Daniels, North Carolina author, newspaper editor and White House Press Secretary to President Franklin D. Roosevelt, wrote that it was "the South at its most beautiful: the green sloping campus to the red-brick buildings with the tall white porticoes. ... I wish it were the picture of the South. I wish, indeed, it were the picture of America."[35] Washington and Lee History Professor Ted DeLaney, who was born and grew up in Lexington during Jim Crow and spent more than 45 years of his 60-year career at W&L, more than a quarter-century as a professor, including serving as the first Black chair of the History Department, said in 2019, "W&L is unique because the entire campus is a Confederate monument."[36]

In recent years, Washington and Lee has invested heavily in upgrading and expanding its academic, residential, athletic, research, arts and extracurricular facilities. The new facilities include an undergraduate library, gymnasium, art/music/theater complex, dorms, student center, student activities pavilion and tennis pavilion, as well as renovation of the journalism and commerce buildings and renovation of every fraternity house and construction of several sorority houses. Lewis Hall, the 30-year-old home of the law school, as well as athletic fields and the antebellum Historic Front Campus buildings, are all currently undergoing major renovation.

Constructed in 1991, the Lenfest Center for the Arts has presented both performances from students and presentations that are open to the community. The Reeves Center houses a notable ceramics collection that spans 4,000 years and includes ceramics from Asia, Europe and America, and examples of Chinese export porcelain. The indoor athletics facility, Duchossois, is undergoing renovation and is scheduled to be reopened in fall 2020.

Organization and administration

[edit]The school is governed by a board of trustees that has a maximum of 34 members.[37]

The undergraduate calendar is an unusual three-term system with 13-week fall and winter terms followed by a four-week spring term. The spring-term courses include topical, often unique, seminars, faculty-supervised study abroad, and some domestic and international internships. The law calendar consists of the more traditional early semester system.

Honor system

[edit]Washington and Lee maintains a rigorous honor system that dates from the 1840s.[38] Students, upon entering the institution, vow to act honorably in all academic and nonacademic endeavors.

The honor system is administered by students through the executive committee of the Student Body (and has been since 1905).[39] Students found guilty of an Honor Violation by their peers are subject to a single sanction: expulsion.[40] The honor system is defined solely by students, and there is an appeal process. Appeals are heard by juries composed of students drawn randomly by the University Registrar. A formal assessment of the honor system's "White Book",[41] occasionally including referendums, is held every three years to review the tenets of the honor system. Overwhelmingly, students continue to support the honor system and its single sanction, and they and alumni point to the honor system as one of the distinctive marks they carry with them from their W&L experience.[42]

Washington and Lee's honor system does not have a list of rules that define punishable behavior—beyond the traditional guide of the offenses lying, cheating or stealing. Exams at W&L are ordinarily unproctored and self-scheduled. It is not unusual for professors to assign take-home, closed-book finals with an explicit trust in their students not to cheat.[43]

The honor system is strongly enforced. In most years, only a few students withdraw in the face of an honor charge or after investigations and closed hearings conducted by the executive committee of the Student Body, the elected student government (with the accused counseled by Honor Advocates, often law students). In recent years, four or five students have left each year.[citation needed] Students found guilty in a closed hearing may appeal the verdict to an open hearing before the entire student body, although this option is rarely exercised. If found guilty at an open trial, the student is dismissed permanently.[42]

Separately from the student-run honor system, the Student Judicial Council and the Student-Faculty Hearing Board hear allegations of student misconduct.[44]

Academics

[edit]Rankings and reputation

[edit]| Academic rankings | |

|---|---|

| Liberal arts | |

| U.S. News & World Report[45] | 21 |

| Washington Monthly[46] | 7 |

| National | |

| Forbes[47] | 47 |

| WSJ/College Pulse[48] | 70 |

In the 2026 U.S. News & World Report rankings, the undergraduate college is tied for 21st among national liberal arts colleges and 14th among Best Value Schools,[49] and the law school is ranked tied for 33rd nationally among all law schools.[50] Forbes magazine college rankings placed W&L 47th among the top 500 universities, liberal arts colleges, and service academies for their 2024-25 list.[51] For the 2024 Rankings, Washington Monthly ranked Washington and Lee 7th among 197 liberal arts colleges in the U.S. based on its contribution to the public good, as measured by social mobility, research, and promoting public service.[52] In 2023, Degreechoices ranked Washington and Lee 3rd out of 209 liberal arts colleges and 14th for business.[53]

Kiplinger's Personal Finance ranked the college 3rd in its 2019 list of 149 best private liberal arts college values and 6th overall among 500 colleges and universities.[54] In 2015, The Economist ranked Washington and Lee first among all undergraduate institutions in the United States in terms of the positive gap between its students' actual median earnings ten years from graduation and what the publication's statistical model would suggest. Of its findings, the newspaper wrote that "No other college combines the intimate academic setting and broad curriculum of a LAC [liberal arts college] with a potent old-boy network."[55]

Admissions and financial aid

[edit]For the class of 2029, W&L reported the following:[56]

Admissions information

- 13% Selectivity rate ~ 1,216 admitted out of 8,969 applications

Statue of Cyrus McCormick - 41% Yield rate ~ 499 enrolled out of 1,216 admitted

- 22% Domestic students of color (students identifying as Asian American, African American, Hispanic, Native American, Pacific Islander and multi-racial)

- 10% First-generation college students

- 11% Children of alumni

- 9% International students

- Scores (52% of students who submitted scores during this test-optional year)

- 33–34 Middle 50% ACT Composite

- 34 Median ACT

- 1450–1510 Middle 50% SAT

- 1480 Median SAT

Financial aid information

- 63% Students receiving W&L grant assistance

- $66,084 Average need-based grant

- $71,792 Average institutional award (need and/or merit-based)

- 15% Pell Grant recipients

Organization

[edit]

Washington and Lee is divided into three schools: (1) The College, where all undergraduates begin their studies, encompassing the liberal arts, humanities and hard sciences, with notable interest among students in pre-health and pre-law studies; (2) the Williams School of Commerce, Economics, and Politics, which offers majors in accounting, business administration, economics, and politics; and (3) the School of Law, which offers the Juris Doctor degree.

More than 800 undergraduate courses are offered. With no graduate program (except in law), every course is taught by a faculty member.[57] The libraries contain more than 700,000 volumes as well as a vast electronic network. The law library has an additional 400,000 volumes as well as extensive electronic resources.

Washington and Lee offers 40 undergraduate majors (including interdisciplinary majors in neuroscience, Medieval and Renaissance studies, and Russian area studies) and 30 minors, including interdisciplinary programs in Africana studies, East Asian studies, Education and Education policy, environmental studies, Latin American & Caribbean studies, Middle East and South Asian studies, poverty and human capability studies (Shepherd Program),[58] and women's, gender, and sexuality studies. Its most popular undergraduate majors, based on 2021 graduates, were:[59]

- Business Administration and Management (90)

- Economics (49)

- Accounting (45)

- Political Science and Government (35)

- Research and Experimental Psychology (24)

- History (21)

Though Washington and Lee has refused since 2003 to submit data to The Princeton Review, the 2006 edition of The Best 357 Colleges ranked W&L highly for "Best Overall Academic Experience", "Professors Get High Marks", and "Professor Accessibility". In the 2007 edition, Washington and Lee was ranked fourth in "Professors Get High Marks" and sixth in "Professor Accessibility". Combining academics with an active social culture, Washington and Lee ranked 14th in "Best Overall Academic Experience for Undergraduates".[60]

Washington and Lee University is accredited by the Commission on Colleges of the Southern Association of Colleges and Schools.[61]

Student life

[edit]The institution has 1829 students as of 2019[update]. The median family income is $261,100, with 55% of students coming from the top 5% highest-earning families, 8% from the bottom 60%, and 1.5% from the bottom 20% (among the lowest of any U.S. college or university).[62] 82% of students are white, 4.5% are Hispanic, 3.4% are Asian, and 2.2% are Black.[63]

Athletics

[edit]

The school's teams are known as "The Generals" and compete in NCAA Division III in the Old Dominion Athletic Conference and the Centennial Conference for wrestling. Washington and Lee has 12 men's teams (baseball, basketball, cross country, football, golf, lacrosse, soccer, swimming, tennis, indoor and outdoor track & field, and wrestling) and 12 women's teams (basketball, cross country, field hockey, golf, lacrosse, riding, soccer, swimming, tennis, indoor and outdoor track & field, and volleyball). Washington and Lee holds two NCAA National Championship team titles. In 1988, the men's tennis team won the NCAA Division III National Championship title and holds 35 ODAC championships. In 2007, the women's tennis team claimed the NCAA Division III National Championship title. In 2018, the men's golf team finished as runner-up in the NCAA Division III championship. In 2006, 2010, 2011, 2012, and 2015, the Generals football team won the Old Dominion Athletic Conference championship. In 2009, the Generals baseball team won the ODAC championship.[64]

Athletic exclusion was manifest in the early 20th century, when the school forced Rutgers to sit out star African American football player Paul Robeson for a 1916 football game and later forfeited a 1923 game when Washington and Jefferson refused to comply with a similar demand.[65]

Student activities

[edit]Traditions

[edit]Every four years, the school sponsors the Washington and Lee Mock Convention for whichever political party (Democratic or Republican) does not hold the presidency. The convention has received gavel-to-gavel coverage on C-SPAN and attention from many other national media outlets. The convention has correctly picked the out-of-power nominee for 20 of the past 27 national elections. It has been wrong three times since 1948,[66] including its incorrect choice of Bernie Sanders in 2020. In 1984, the failure of the scoreboard significantly slowed the vote tally process and almost led to a wrong selection.[67] The Washington Post declared Washington and Lee's Mock Convention "one of the nation's oldest and most prestigious mock conventions."[68]

The school also hosts an annual Fancy Dress Ball, a 117-year-old formal black-tie event started in 1907. It is put on by a committee of students appointed by the executive committee. The committee is responsible each year to create a theme and handle the logistics of setting up the Fancy Dress Ball. The Fancy Dress Ball has a budget of over $80,000.[69]

Washington and Lee University also follows the "speaking tradition" which traces its history to Robert E. Lee. Under this tradition, students are suggested to greet one another upon passing on campus. This tradition is not enforced.[69]

Fraternities and sororities

[edit]Greek letter organizations play a major role in Washington and Lee's social scene. The university has several houses of fraternities and sororities.[70]

Media and culture

[edit]The eminent photographer Sally Mann got her start at Washington and Lee, photographing the construction of the law school while an employee. The photos eventually became the basis of a one-woman exhibition at the Corcoran Gallery in Washington, D.C.[citation needed]

Secretariat, who holds the record for the fastest time in the Kentucky Derby, Preakness Stakes, and Belmont Stakes, and the winner of the Triple Crown in 1973, wore royal blue and white (as shown in the 2010 film) because his co-owner, Christopher Chenery, was a graduate and trustee of Washington and Lee.[citation needed]

Alumnus George William Crump, while a student (in 1804) at Washington College (predecessor to Washington and Lee University) circa 1800 to 1804, was arrested for running naked through Lexington, Virginia: it was the United States' first recorded incident of streaking.[71] Crump is better known as member of the United States House of Representatives in the 19th United States Congress and the U.S. Ambassador to Chile.[72]

A Washington and Lee art history professor, Pamela Hemenway Simpson, in 1999 wrote the first scholarly book on linoleum, giving it the title Cheap, Quick and Easy.[73] The book also examines other lower-cost home-design materials.

Washington and Lee is home to a collection of 18th- and 19th-century Chinese and European porcelain, the gift of Euchlin Dalcho Reeves, a 1927 graduate of the law school, and his wife, Louise Herreshoff. In 1967, Reeves contacted Washington and Lee about making "a small gift", which turned out to be a collection of porcelain so vast that it filled two entire houses which he and his wife owned in Providence, Rhode Island. A number of dirt-covered picture frames, found in the two houses, were put on the van along with the porcelain. Soon it was discovered that the frames actually contained Impressionist-like paintings created by Herreshoff as a young woman in the early days of the century. In 1976 the Corcoran Gallery in Washington, D.C., mounted a posthumous one-woman exhibition of Herreshoff's works.[citation needed]

Music

[edit]Before it morphed into a swing, Dixieland and bluegrass standard, "The Washington and Lee Swing" was one of the most well known—and widely borrowed—football marches ever written, according to Robert Lissauer's Encyclopedia of Popular Music in America. Schools and colleges from Tulane to Slippery Rock copied it (sometimes with attribution). It was written in 1910 by Mark W. Sheafe, '06, Clarence A. (Tod) Robbins, '11, and Thornton W. Allen, '13. It has been recorded by virtually every important jazz and swing musician, including Glenn Miller (with Tex Beneke on vocals), Louis Armstrong, Kay Kyser, Hal Kemp and the Dukes of Dixieland.[74] "The Swing" was a trademark of the New Orleans showman Pete Fountain. The trumpeter Red Nichols played it (and Danny Kaye pretended to play it) in the 1959 movie The Five Pennies. (Here[75] is an audio excerpt from a 1944 recording by Jan Garber, a prominent dance-band leader of the era. Here[76] is an exuberant instrumental version by a group called the Dixie Boys, which YouTube dates to 2006.)

Notable alumni

[edit]

Washington and Lee University is the alma mater of three United States Supreme Court justices, a Nobel Prize laureate, winners of the Pulitzer Prize, the Tony Award, and the Emmy Award, as well as 27 U.S. senators, 67 U.S. representatives, 31 state governors, as well as numerous other government officials, judges, business leaders, entertainers, and athletes.

Several well-known alumni include past American Bar Association President Linda Klein (School of Law), Utah Governor Spencer Cox (School of Law), Kentucky Governor Matt Bevin, Virginia Governor Linwood Holton, United States Supreme Court Justice Lewis F. Powell Jr.; United States Senator John Warner from Virginia; United States Solicitor General John W. Davis, Democratic Party nominee for President of the United States during the 1924 presidential election; author Tom Wolfe, founder of New Journalism; broadcast journalist Roger Mudd; Anglican bishop Steve Breedlove; artist Cy Twombly; voice actor Mike Henry; Federal Judge and Civil Rights champion John Minor Wisdom; billionaire Rupert Johnson Jr. of Franklin Templeton Investments; financial journalist, and non-fiction writer Mary Childs and Mark Sappenfield, editor-in-chief of The Christian Science Monitor.

Archives of the papers of notable alumni and other resources relating to the history of the institution may be found in the manuscript collections at Washington and Lee's James Graham Leyburn Library. Publication of the 1995 guide to the collections was made possible by a grant from the Jessie Ball DuPont Fund.[77]

In literature

[edit]A fictionalized representation of the institution appears in L'Étudiant étranger by Philippe Labro (1986, Editions Gallimard), translated into English two years later and published as The Foreign Student (Ballantine Books). In 1994 it was made into a movie, starring Robin Givens and Marco Hofschneider, but it grossed only $113,000 at the box office.[78]

Other novels about Washington and Lee University include Geese in the Forum (Knopf, 1940) by Lawrence Edward Watkin, a professor of English who went on to become a screenwriter for Disney (the college faculty were the titular geese); The Hero (Julian Messner, 1949), by Millard Lampell, filmed as Saturday's Hero, starring Donna Reed and John Derek (Columbia Studios, 1951), about a football player who struggles to balance athletics, academics and a social life; and A Sound of Voices Dying by Glenn Scott (E.P. Dutton, 1954), released in a paperback edition in 1955 under the new title Farewell My Young Lover (replete with a lurid illustration on the cover). The Russian-born American author Maxim D. Shrayer depicted a fictionalized version of the Washington & Lee campus in the story "Trout Fishing in Virginia" (2007), included in his collection Yom Kippur in Amsterdam (2009).

References

[edit]- ^ As of March 7, 2022. U.S. and Canadian Institutions Listed by Fiscal Year 2021 Endowment Market Value and Change in Endowment Market Value from FY20 to FY21 (Report). National Association of College and University Business Officers and TIAA. 2022. Archived from the original on April 10, 2023. Retrieved June 5, 2023.

- ^ "President's Office". Washington and Lee University. Archived from the original on January 6, 2017. Retrieved January 5, 2017.

- ^ "Lena Hill Named Provost at Washington and Lee University". November 10, 2020. Archived from the original on March 28, 2021. Retrieved July 1, 2021.

- ^ "College Navigator - Washington and Lee University".

- ^ "Graphics Standards - Complementary Typeface and Colors". Archived from the original on June 26, 2022. Retrieved July 27, 2022.

- ^ "Complementary Typeface and Color : Washington and Lee University". Wlu.edu. Archived from the original on August 15, 2018. Retrieved November 12, 2015.

- ^ a b c d e f g "A History :: Washington and Lee University". Wlu.edu. Archived from the original on February 26, 2012. Retrieved February 28, 2011.[dead link]

- ^ Education, United States Office of (1887). Contributions to American Educational History.

- ^ "Washington And Lee University". Braintrack.com. Archived from the original on September 23, 2010. Retrieved February 28, 2011.

- ^ "Chavis Hall". Washington and Lee University. Archived from the original on March 30, 2023. Retrieved October 24, 2022.

- ^ "Timeline of Affirmative Action". The Journal of Blacks in Higher Education. 2007. Archived from the original on October 31, 2012. Retrieved July 19, 2015.

- ^ a b "University History". wlu.edu. Retrieved August 24, 2022.

- ^ Eckert, Brian (April 22, 2014). "Copy of "Old George" Joins Museum of the Shenandoah Valley Exhibit". Washington and Lee University. Archived from the original on February 7, 2016. Retrieved February 7, 2016.

- ^ "Continuing the Community Conversation : Washington and Lee University". Wlu.edu. Archived from the original on July 14, 2014. Retrieved November 12, 2015.

- ^ T. Rees Shapiro (July 8, 2014). "Washington and Lee University to remove Confederate flags following protests". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on September 17, 2017. Retrieved November 12, 2015.

- ^ Chen, Karen (July 8, 2014). "U.S. colleges have worked to address ties to slavery, Confederacy". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on March 17, 2018. Retrieved November 12, 2015.

- ^ Lawton, Christopher R. (2009). "Constructing the Cause, Bridging the Divide: Lee's Tomb at Washington's College". Southern Cultures. 15 (2): 9. ISSN 1068-8218. JSTOR 26214206.

- ^ Washington and Lee University Archived August 11, 2014, at the Wayback Machine website.

- ^ "The Myth of Kindly General Lee". theatlantic.com. June 4, 2017. Archived from the original on June 5, 2017. Retrieved June 4, 2017.

Lee was as indifferent to crimes of violence towards blacks carried out by his students as he was when they was carried out by his soldiers.

- ^ Dudley, Will (January 18, 2018). "2018 Founders Day Remarks". Washington and Lee University. Retrieved March 13, 2021.

- ^ "The Future of Washington and Lee University". Washington and Lee University. Archived from the original on June 6, 2021. Retrieved June 8, 2021.

- ^ "W&L Concludes Outstanding Fund-Raising Year". W&L. August 12, 2008. Archived from the original on June 2, 2010. Retrieved August 20, 2012.

- ^ "Washington and Lee University Receives $100 Million Gift". Washington and Lee University Press Release. June 11, 2007. Retrieved October 24, 2022.

- ^ "Virginia university to remove Confederate flags from chapel". CNN Wire. July 9, 2014. Archived from the original on September 6, 2017. Retrieved September 6, 2017.

- ^ Shapiro, T. Rees (July 8, 2014). "Washington and Lee University to remove Confederate flags following protests". The Washington Post.

- ^ Toscano, Pasquale S. (August 22, 2017). "My University Is Named for Robert E. Lee. What Now?". The New York Times.

- ^ Bell, Elizabeth (July 6, 2020). "Washington and Lee faculty vote to change the institution's name". Richmond Times-Dispatch. Archived from the original on December 10, 2020. Retrieved March 11, 2021.

- ^ McAlevey, Mike (July 7, 2020). "Board of Trustees' Plan to Address Issues of Racial Justice and University History". Washington and Lee University. Retrieved March 11, 2021.

- ^ Thomas, Pat (June 4, 2021). "Washington and Lee University will not change name". Archived from the original on June 5, 2021. Retrieved June 5, 2021.

- ^ "National Register Information System – (#71001047)". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service. July 9, 2010.

- ^ "Virginia Landmarks Register". Virginia Department of Historic Resources. Archived from the original on September 21, 2013. Retrieved March 19, 2013.

- ^ "About W&L :: Washington and Lee University". Wlu.edu. Archived from the original on December 23, 2009. Retrieved February 28, 2011.

- ^ "Washington and Lee University: Virginia Main Street Communities: A National Register of Historic Places Travel Itinerary". Nps.gov. Archived from the original on November 23, 2008. Retrieved February 28, 2011.

- ^ "Drinkwater pays tribute to W. & L." (PDF). The Ring-tum Phi. February 17, 1926. pp. 1, 4. Archived from the original (PDF) on March 3, 2022. Retrieved March 18, 2021.

- ^ Daniels, Jonathan (November 1941). "Seeing the South". Harper's.

- ^ Covington, Abigail (November 4, 2019). "What Do We Do With Robert E. Lee?". The Delacorte Review. Retrieved March 14, 2021.

- ^ "Board of Trustees". Washington and Lee Univ. Archived from the original on November 29, 2010. Retrieved September 20, 2010.

- ^ "Report of the Commission on Institutional History and Community". Washington and Lee University. May 2, 2018. Retrieved November 18, 2023.

- ^ "The Honor System". Archived from the original on May 29, 2015. Retrieved May 20, 2015.

- ^ "Enforcement Procedure". Archived from the original on December 9, 2014. Retrieved February 7, 2012.

- ^ "White Book". Washington and Lee Univ. Archived from the original on September 10, 2015. Retrieved September 1, 2015.

- ^ a b "The Honor System". Washington and Lee Univ. Archived from the original on December 29, 2010. Retrieved September 20, 2010.

- ^ Anderson, Nick (December 14, 2012). "Washington Post: Honor and Testing at Washington and Lee University". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on May 25, 2014. Retrieved December 17, 2012.

- ^ "Student-Faculty Hearing Board". Washington and Lee Univ. Archived from the original on May 28, 2010. Retrieved September 20, 2010.

- ^ "2024-2025 National Liberal Arts Colleges Rankings". U.S. News & World Report. September 23, 2024. Retrieved November 22, 2024.

- ^ "2024 Liberal Arts Colleges Rankings". Washington Monthly. August 25, 2024. Retrieved August 29, 2024.

- ^ "America's Top Colleges 2025". Forbes. September 6, 2025. Retrieved October 3, 2025.

- ^ "2025 Best Colleges in the U.S." The Wall Street Journal/College Pulse. September 4, 2025. Retrieved October 3, 2025.

- ^ "U.S. News Best Colleges Rankings – Washington and Lee University". U.S. News & World Report. 2020. Archived from the original on November 23, 2018. Retrieved September 12, 2019.

- ^ "U.S. News Best Law Schools – Washington and Lee University". U.S. News & World Report. 2020. Archived from the original on October 24, 2016. Retrieved May 26, 2020.

- ^ "Forbes America's Top Colleges List 2025 - Best US Universities Ranked". Forbes. Archived from the original on January 15, 2018. Retrieved February 20, 2025.

- ^ "2024 Liberal Arts Colleges Ranking". Washington Monthly. Retrieved March 12, 2025.

- ^ "The best liberal arts colleges in the U.S." Degreechoices.com. Archived from the original on August 25, 2023. Retrieved August 25, 2023.

- ^ "Kiplinger's Best College Values". Kiplinger's Personal Finance. July 2019. Archived from the original on August 23, 2019. Retrieved September 12, 2019.

- ^ "Where's Best". The Economist. October 31, 2015. Archived from the original on October 18, 2017. Retrieved September 18, 2017.

- ^ "2029 Class Profile". Archived from the original on May 16, 2025. Retrieved September 8, 2025.

- ^ "Departments and Programs:: Washington and Lee University". Wlu.edu. Archived from the original on February 8, 2012. Retrieved February 28, 2011.

- ^ "Shepherd Program". Washington & Lee University. Archived from the original on February 17, 2001.

- ^ "Washington and Lee University". nces.ed.gov. U.S. Dept of Education. Archived from the original on February 20, 2023. Retrieved February 20, 2023.

- ^ "Washington and Lee University". Princetonreview.com. Archived from the original on February 18, 2008. Retrieved February 28, 2011.

- ^ "Accreditation :: Washington and Lee University". Washington and Lee University. Archived from the original on April 11, 2017. Retrieved April 10, 2017.

- ^ Aisch, Gregor; Buchanan, Larry; Cox, Amanda; Quealy, Kevin (January 18, 2017). "Economic diversity and student outcomes at Washington and Lee". The New York Times. Archived from the original on March 14, 2024. Retrieved August 9, 2020.

- ^ "Undergraduate Ethnic Diversity at Washington and Lee University". College Factual. February 20, 2013. Archived from the original on October 2, 2023. Retrieved August 9, 2020.

- ^ "Athletics at W&L :: Washington and Lee University". Wlu.edu. Archived from the original on June 6, 2010. Retrieved February 28, 2011.

- ^ "African Americans at Washington and Lee :: Washington and Lee University". Wlu.edu. Archived from the original on September 21, 2015. Retrieved October 14, 2015.

- ^ U.S. News & World Report, "Campus Pundits' Winning Record", January 28, 2008

- ^ W&L Mock Convention 2008 Official Site

- ^ Washington Post, 1996

- ^ a b "Our Traditions". Washington and Lee University. Archived from the original on June 23, 2016. Retrieved June 18, 2016.

- ^ "Welcome to Kappa Alpha Order, Zeta Zeta Chapter". Ka-zetazeta.com. Archived from the original on July 13, 2011. Retrieved February 28, 2011.

- ^ "Streaking: A timeline". The Week. Dennis Publishing Limited. January 8, 2015. Archived from the original on October 21, 2021. Retrieved October 21, 2021.

1804: George William Crump becomes the first American college student arrested for streaking. Crump is suspended for the term from his Virginia school, Washington College (now Washington and Lee), but goes on to serve in Congress and as ambassador to Chile. With Robert E. Lee's blessing, streaking later becomes a rite of passage for Washington and Lee men.

- ^ McDonnell, Hannah. "People Who Went To Penn: George William Crump". Under the Button. Archived from the original on October 2, 2023. Retrieved January 27, 2024.

- ^ Simpson, Pamela Hemenway (1999). Cheap, Quick and Easy. Univ. of Tennessee Press. ISBN 1572330376.

- ^ "Washington and Lee University Store - for W&L; I Yell". Archived from the original on September 28, 2007. Retrieved July 22, 2019.

- ^ The Washington and Lee Swing. www.bizpubs.com (MP3). Archived from the original on June 15, 2007. Retrieved August 14, 2022.

- ^ drh1589. "Dixie Boys – FIARTIL – Estoril 2006 (Washington and Lee Swing)". YouTube. Archived from the original on January 5, 2016. Retrieved February 28, 2011.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ Vaughan, Stanley (1995). A Guide to the Manuscripts Collection of the James Graham Leyburn Library (1995 ed.). Lexington, Virginia: Washington and Lee University.

- ^ "Foreign Student (1994) – Box office / business". IMDb. July 29, 1994. Archived from the original on March 20, 2016. Retrieved June 28, 2018.

Further reading

[edit]- Crenshaw, Ollinger. General Lee's College: The Rise and Growth of Washington and Lee University (Random House, 1969), the major history; online

- Owens, Joshua. "Case Study of the Founding Years of Liberty Hall Academy: The Struggle Between Enlightenment and Protestant Values on the Virginia Frontier" Journal of Backcountry Studies, (2009) 4#2 p1+ online

External links

[edit]- Official website

- Athletics website

- . New International Encyclopedia. 1905.

- . The American Cyclopædia. 1879.

- Washington and Lee University, Lexington, Lexington, VA: 1 photo at Historic American Buildings Survey

- Washington and Lee University, Washington Hall, Jefferson Street, Lexington, Lexington, VA: 4 photos, 8 data pages, and 1 photo caption page at Historic American Buildings Survey

- Washington and Lee University, Lexington, Lexington, VA at HABS

Washington and Lee University

View on GrokipediaHistory

Founding and Early Development (1749–1796)

The institution originating Washington and Lee University was established in 1749 as Augusta Academy, a small classical grammar school founded by Scots-Irish Presbyterian pioneers in Augusta County, Virginia, near Greenville, marking the first school of consequence west of the Blue Ridge Mountains.[13][14] This founding date, while traditionally accepted and positioning the school as the ninth-oldest in the United States, relies partly on oral traditions formalized in the late 19th century.[15] In its initial decades, Augusta Academy endured instability, relocating multiple times amid challenges such as fires and inadequate facilities, before stabilizing near Lexington.[3] By 1776, reflecting revolutionary fervor, the trustees renamed it Liberty Hall Academy.[14] The Virginia General Assembly chartered it as a degree-granting institution in 1782, authorizing a move to Rockbridge County on the western edge of Lexington and funding construction of a three-story stone edifice to house classes, library, and dormitories.[13][16] Enrollment remained modest, with instruction emphasizing classical languages, rhetoric, and moral philosophy under Presbyterian oversight. Financial distress intensified by the mid-1790s, prompting trustees in December 1795 to solicit aid from George Washington, highlighting the academy's role in educating frontier youth.[17] Washington responded in 1796 by donating 100 shares of James River Company stock, initially valued at about $20,000 and constituting the largest gift to an American educational institution to date, which provided critical endowment income and averted closure.[17][18] In gratitude, the trustees renamed it Washington Academy that year, later evolving to Washington College.[14]Washington College Period (1796–1865)

In 1796, George Washington donated 100 shares of stock in the James River Company, valued at approximately $20,000, to the financially struggling Liberty Hall Academy in Lexington, Virginia, providing crucial support that prevented its closure.[18][19] In gratitude, the trustees renamed the institution Washington Academy later that year.[14] The ongoing dividends from this endowment offered financial stability amid persistent monetary challenges during the early 19th century.[20] The academy transitioned to Washington College in 1813, reflecting its evolution into a more formal collegiate structure focused on classical liberal arts education under Presbyterian influence.[20][21] Enrollment remained modest, with around 65 students reported in 1825, indicative of its regional scope and limited resources.[10] Leadership during this era included several Presbyterian clergymen serving as presidents, emphasizing moral and intellectual discipline; notable among them was George Junkin, who assumed the presidency in 1848 and navigated the institution through growing sectional tensions.[20] As the United States approached civil conflict, Washington College's student body, numbering about 140 in 1861, largely favored Virginia's secession, forming the Liberty Hall Volunteers company that joined the Stonewall Brigade in the Confederate Army.[20] Faculty opinions diverged, with some Union sympathizers amid the predominantly Southern context. The college remained operational throughout the war, unlike many peers, though it suffered looting by Union General David Hunter's forces in June 1864, who ransacked buildings and confiscated resources.[20] By 1865, enrollment had dwindled to fewer than 50 students, reflecting wartime attrition and devastation.[3]Robert E. Lee's Presidency and Reconstruction (1865–1870)

Following the surrender at Appomattox Court House on April 9, 1865, Robert E. Lee accepted the presidency of Washington College on August 4, 1865, at the urging of the board of trustees, who sought his prestige to revive the war-ravaged institution.[14] [22] The college had suffered extensive damage during the conflict, including occupation by Union forces, destruction of facilities, and a drastic decline in enrollment to approximately 40 students served by four faculty members.[23] [20] Lee, pardoned by President Andrew Johnson in June 1865 and barred from federal office but free to pursue civilian roles, viewed the position as an opportunity to counsel Southern youth toward reconciliation with the Union and productive citizenship, emphasizing self-reliance over resentment.[22] He assumed duties in September 1865, commuting from his nearby White House plantation before relocating to Lexington.[22] Under Lee's administration, enrollment surged from fewer than 50 students in 1865 to a peak of 411 in 1868 and 345 by 1870, drawing pupils from across the South and even some from the North, attracted by his reputation and the institution's recovery.[24] [23] He broadened the curriculum beyond classical liberal arts to include practical fields such as engineering, applied science, journalism, and commerce, aiming to equip graduates for economic reconstruction in a defeated South lacking its prior agrarian base.[22] [4] Lee also secured endowments through appeals to donors nationwide, enhancing financial stability, and oversaw infrastructure projects like the construction of the President's House in 1868 and the University Chapel between 1866 and 1868.[22] [14] A key innovation was the establishment of an honor system, rooted in Lee's trust-based approach to discipline; he reduced faculty oversight of exams and daily conduct, relying on students' self-enforcement of integrity, which laid the groundwork for the first student-run honor code in an American college.[25] [26] [4] In the Reconstruction context, Lee's presidency emphasized stoic adaptation to federal policies, urging students to prioritize education and loyalty to Virginia's laws over political agitation, though he privately opposed African American suffrage and supported conservative efforts to restore white Democratic control in Virginia by 1869.[22] This pragmatic focus helped the college navigate Radical Republican oversight and economic hardship, transforming it from near collapse into a viable institution serving 415 students at his death on October 12, 1870, from a stroke.[24] [22] His tenure, marked by personal oversight of classes and correspondence with alumni, fostered a culture of discipline and utility that endured beyond the era's turmoil.[4]Renaming and Late 19th Century Growth

Following Robert E. Lee's death on October 12, 1870, the board of trustees of Washington College renamed the institution Washington and Lee University later that year, honoring Lee's presidency from 1865 to 1870 during which he had revitalized the struggling postwar school by expanding enrollment from fewer than 50 students to over 400, diversifying the curriculum with new fields such as journalism, applied mathematics, and modern languages, and instituting an honor system that emphasized student self-governance.[3] The renaming reflected the faculty's request and the trustees' recognition of Lee's role in transforming the college from near financial ruin amid Reconstruction-era challenges into a viable institution attracting students primarily from the South.[3] George Washington Custis Lee, Robert E. Lee's eldest son and a former Confederate general and West Point graduate, was inaugurated as the university's ninth president on February 6, 1871, succeeding his father and serving until his resignation in 1897.[14] Under Custis Lee's administration, the university experienced steady progress amid economic recovery in the post-Civil War South, maintaining the academic innovations and honor tradition established by his father while navigating limited resources and regional instability. Enrollment stabilized and gradually increased as the institution drew students seeking classical and professional education, though specific figures for the period remain sparse in historical records; by the late 1880s, the university had begun to solidify its reputation for rigorous liberal arts instruction. Key developments included internal debates, such as the 1873 Graham-Lee Society discussion on coeducation, which ultimately preserved the all-male student body until the 20th century, reflecting conservative institutional priorities focused on academic continuity rather than rapid modernization.[14] Custis Lee's tenure emphasized administrative stability, with the university benefiting from its historic ties to George Washington—whose 1796 endowment had earlier saved the school—and Lee's legacy, which continued to draw alumni loyalty and modest philanthropic support despite broader Southern economic hardships. No major new buildings were constructed during this era, but the campus core, including structures like Lee Chapel completed in 1868, served as enduring symbols of the university's heritage.[14] This period laid the groundwork for later expansions by prioritizing fiscal prudence and fidelity to the founders' vision over aggressive growth.20th Century Modernization and Expansion

In the early 20th century, Washington and Lee University built upon its foundational programs by formalizing the School of Commerce, which evolved from a student business initiative started under Robert E. Lee in 1867 and became a structured department by around 1905, emphasizing practical business education alongside the liberal arts core.[4] This development reflected broader national trends in higher education toward professional training, with successive presidents like Henry St. George Tucker (acting 1904–1905) and later leaders prioritizing curricular adaptation while preserving institutional traditions such as the Honor System.[27] By the 1930s, the university navigated economic challenges of the Great Depression and World War II, maintaining enrollment stability through targeted administrative reforms that enhanced faculty recruitment and academic rigor, as chronicled in institutional histories covering 1930–2000.[28] Mid-century expansion included infrastructural improvements and diversification efforts. Enrollment, which hovered around 500–600 students in the 1920s based on state-by-state breakdowns in alumni records, gradually increased amid post-war demand for higher education, supported by federal initiatives like the GI Bill.[29] In 1964, the Board of Trustees adopted a nondiscriminatory admissions policy, leading to the enrollment of the first Black undergraduates in 1966, marking a shift from de facto segregation and aligning with federal civil rights pressures while expanding the student body's demographic scope without altering core academic standards.[30] The law school, meanwhile, underwent periodic critiques and reforms to modernize legal pedagogy, incorporating case methods and clinical training by the mid-20th century.[31] The late 20th century featured significant modernization through coeducation. The law school admitted its first women in 1972, reflecting incremental gender integration in professional programs.[14] For undergraduates, the Board of Trustees voted on July 14, 1984, to admit women starting in fall 1985, a decision reached after extensive debate and surveys showing majority alumni support despite vocal opposition from some traditionalists concerned about cultural shifts.[32][33] This transition boosted enrollment from approximately 1,200 male students pre-1985 to over 1,800 by 2000, enhancing academic vitality and competitiveness in liberal arts rankings while sustaining small class sizes and the Honor System's emphasis on personal integrity.[28] Overall, these changes positioned the university as a selective, residential liberal arts institution adapting to demographic and societal demands without diluting its commitment to rigorous, honor-bound education.[14]21st Century Developments and Challenges

In the early 2000s, Washington and Lee University undertook significant campus renovations, including updates to the historic Colonnade buildings to accommodate modern pedagogical needs, as part of broader efforts to enhance facilities for liberal arts education.[34] The university also constructed the Washington and Lee Center for Global Learning, a facility designed to foster interdisciplinary engagement with international issues, reflecting a push toward expanded academic infrastructure.[35] Undergraduate enrollment remained relatively stable throughout the period, averaging approximately 1,849 students over the past decade, with recent figures around 1,898, supported by an 8:1 student-faculty ratio that underscores the institution's emphasis on small-class instruction.[36] [5] By the 2010s and into the 2020s, the university adopted a strategic plan positioning itself as a model for 21st-century liberal arts education, with initiatives focused on innovation in teaching, research, and community trust.[37] Ongoing construction projects, including science lab upgrades and flexible classroom expansions, continued as of late 2024 to address demands for advanced STEM and humanities spaces.[38] These developments coincided with efforts to broaden access, though the undergraduate population hovered around 1,885 in recent years, indicative of steady but not expansive growth amid competitive liberal arts admissions.[39] A major challenge emerged in 2020 amid national reckonings with historical symbols, when protests and petitions demanded removal of Robert E. Lee's name from the institution due to his role as a Confederate general, arguing it perpetuated associations with slavery and racial injustice.[40] [41] In June 2021, the Board of Trustees voted 22-6 to retain the name Washington and Lee, citing Lee's post-Civil War contributions as president, which transformed the struggling college into a rigorous academic entity, while acknowledging the need for contextualization of history.[42] [43] The decision drew criticism from advocates for change but led to commitments for enhanced diversity initiatives, revisions to campus practices, and governance adjustments, including modifications to symbols in Lee Chapel without altering its core structure.[44] [45] The university's student-run Honor System, a hallmark since Lee's era emphasizing a single sanction of expulsion for violations like lying, cheating, or stealing, faced internal scrutiny in the 2020s. Critics, including some faculty and students, argued it fosters overly punitive enforcement perceived as discriminatory or lacking nuance, with calls for reforms to codify procedures and reconsider the single sanction amid declining faith in self-governance.[46] [47] Community discussions as recent as 2025 highlighted tensions between preserving the system's trust-based freedoms—such as unproctored exams—and adapting to modern concerns over equity and transparency in adjudication.[48] [49] Despite these debates, the system retains strong support for upholding institutional integrity, though it underscores broader challenges in balancing tradition with evolving campus expectations.[50]Campus and Infrastructure

Historic Core and Architecture

The historic core of Washington and Lee University's campus comprises the Colonnade, a unified ensemble of neo-classical buildings that constitutes the architectural and symbolic heart of the institution. This district, listed on the National Register of Historic Places and designated a National Historic Landmark in 1961, exemplifies early 19th-century educational architecture through its cohesive design, evolving from Federal to Greek Revival influences over more than a century. The Colonnade's structures, primarily brick with classical detailing, reflect regional adaptations of Roman and Greek Revival styles, emphasizing symmetry, porticos, and pediments.[51] Washington Hall, erected in 1824 by builder John Jordan, serves as the Colonnade's centerpiece with its three-story brick facade in the Federal style, topped by a cupola housing a statue. Originally the principal academic facility, the temple-form building features sturdy quoins and entablatures, transforming prevailing Roman Revival elements into a robust local idiom suited to Virginia's climate and materials. Flanking it are the two wings of Payne Hall, constructed in 1831 as dormitories with rectangular brick forms, shallow hipped roofs, and coupled Doric pilasters; these have since been repurposed for administrative and classroom use while retaining their classical proportions.[51][52]

Lee Chapel, situated adjacent to the Colonnade, was constructed between 1867 and 1868 under the supervision of university president Robert E. Lee, utilizing brick in a restrained Greek Revival design with a pedimented portico. Designed by Virginia Military Institute engineering professor Thomas Williamson, with input from Lee and his son George Washington Custis Lee, the structure initially functioned as a nondenominational assembly and prayer hall, dedicated on June 14, 1868. An 1883 rear extension by architect J. Crawford Neilson added space for Edward V. Valentine's recumbent statue of Lee, enhancing its role as a memorial site while preserving the original facade's simplicity. The chapel's architecture underscores Lee's emphasis on functional, dignified spaces amid post-Civil War reconstruction constraints.[53][54][55] These buildings collectively convey a sense of continuity and institutional prestige, with the Colonnade's harmonious progression influencing later campus developments and underscoring the university's commitment to classical educational ideals. Preservation efforts, including restorations funded by entities like the Ford Motor Company in the mid-20th century, have maintained the core's integrity despite expansions.[51]

Recent Facilities and Construction Projects

In alignment with its 2021 Campus Master Plan, Washington and Lee University has pursued multiple capital projects since 2023 to enhance academic, wellness, and infrastructure facilities while preserving historic elements.[34] These initiatives, funded through institutional resources and targeted donations, emphasize functionality, sustainability, and accessibility.[56] The Williams School building, a 44,500-square-foot structure dedicated to commerce, economics, and politics programs, broke ground in June 2023 and reached substantial completion by August 2025, enabling occupancy for Fall Term.[57] It includes 10 classrooms, two innovation labs, 52 faculty offices, and collaborative spaces designed to foster interdisciplinary work.[57] [38] Construction of the Lindley Center for Student Wellness, spanning 14,600 square feet, commenced in April 2024 and concluded on August 4, 2025, relocating and expanding student health services with clinical treatment rooms, counseling suites, and ambulance-accessible entry points.[57] [56] University Chapel renovations, addressing a National Historic Landmark, began in October 2024 following the Opening Convocation and are projected to span up to six months, incorporating gallery modernization with updated cabinetry, lighting, and exhibits; HVAC system overhauls; and expanded fire and life safety measures to support preservation and public access.[58] The $1.35 million renovation of the Tom Wolfe ’51 Reading Room in Leyburn Library's Special Collections and Archives started April 21, 2025, after Winter Term exams, transforming the former Boatwright Room into a dedicated research area with enhanced lighting, wood coffered ceilings, tech infrastructure, ergonomic seating, and displays of Wolfe artifacts; completion occurred by September 1, 2025.[59] [57] Sustainability efforts advanced with the summer 2025 installation of over 1,000 high-efficiency solar panels on Sydney Lewis Hall, capping prior roof and landscaping upgrades initiated in May 2023.[57] Elrod Commons received structural patio stabilization and a new ADA-compliant ramp, finalized in summer 2025 as Phase 2 of dining venue enhancements that expanded seating and outdoor terraces by August 2024.[57] [38] Infrastructure improvements encompass a multi-year campus utility overhaul, launched in June 2025, to replace heating and cooling distribution with low-temperature hot water systems, beginning along East Denny Circle.[57] Athletic facilities saw the lower Washburn Tennis Courts resurfaced with an asphalt base, new fencing, and added doubles/pickleball lines starting June 2025, achieving completion by Labor Day.[57] Preparations for golf course lengthening at Lexington Golf & Country Club, including a temporary practice range, extended from August 2025 through May 2027.[57]Governance and Administration

Organizational Structure and Leadership

Washington and Lee University is governed by its Board of Trustees, which holds ultimate fiduciary responsibility for the institution's management and oversight in accordance with its charter, bylaws, and strategic plans.[60] The board executes these duties through standing and ad hoc committees, convening in three annual plenary sessions to review operations, finances, and academic policies.[60] Wangdali C. “Wali” Bacdayan serves as Rector of the Board.[61] The university president, as chief executive officer, reports to the Board of Trustees and directs day-to-day administration, strategic initiatives, and implementation of board policies.[61] William C. Dudley has held the position since January 1, 2017, succeeding Kenneth P. Ruscio.[62] [63] Supporting the president is a senior administrative team comprising the provost and vice presidents overseeing academic, financial, student, and advancement functions. The provost, Lena Hill, serves as chief academic officer since July 2021, managing faculty affairs, curriculum, and deans of the College and School of Law.[64] [65] Key vice presidents include:| Position | Name | Responsibilities |

|---|---|---|

| Vice President for Admissions and Financial Aid | Sally Stone Richmond | Oversees undergraduate and law school recruitment, enrollment, and aid distribution.[61] |

| Vice President for Finance, University Treasurer | Steven G. McAllister | Manages budget, treasury, and financial operations.[61] |

| Vice President for Student Affairs | Alex Miller | Directs residential life, health services, and extracurricular support.[61] |

| Vice President for University Advancement | Susan Wood | Leads fundraising, alumni relations, and communications strategies.[61] |

| Secretary of the University, Vice President for Communications and Strategic Initiatives | Jessica Willett | Handles public affairs, media, and policy coordination.[61] |

The Honor System: Origins and Principles

The Honor System at Washington and Lee University originated in the mid-1840s during the Washington College era, predating Robert E. Lee's presidency by two decades.[67] It evolved from informal practices of student self-governance rooted in early 19th-century Southern collegiate traditions, where faculty ceded oversight of academic integrity to peers under an assumption of personal honor.[68] Although Lee is frequently credited with its institutionalization—due to his emphasis on character development amid post-Civil War reconstruction—the system's foundational elements, including unproctored examinations, were already in place before his 1865 arrival.[26] The first fully student-run iteration emerged under Lee's tenure, aligning with his vision of autonomous student accountability to rebuild institutional trust.[67] Formal codification advanced in 1902, when the university catalog explicitly stated: "Every student is assumed to be a man of honor, and is treated as such. In the recitation rooms and examination halls no watchfulness on the part of the professors is exercised."[14] By 1905, students established the Executive Committee of the Student Body to administer the system directly, marking a shift to complete peer governance without faculty intervention in adjudication.[67] The system's core principles center on a single-sanction model, where proven violations—defined as lying, cheating, stealing, or other breaches of communal trust—result in mandatory dismissal, reinforcing absolute accountability over graduated penalties.[26] This approach presumes inherent student integrity, eliminating proctors, locked doors during tests, and routine faculty surveillance, which enables practices like take-home exams and open access to academic resources.[67] Adjudication occurs through the student-led Executive Committee, which conducts open hearings, reviews evidence from peer reports (mandatory under the system's "report or affirm" clause), and votes on guilt by a two-thirds majority, with the university administration enforcing outcomes without override. The White Book, the codified Honor System manual, outlines these rules, emphasizing transparency via publicized verdicts to deter misconduct and sustain community norms, though it lacks exhaustive enumeration of offenses to avoid loopholes.[25] This framework, among the oldest single-sanction systems in U.S. higher education, prioritizes causal deterrence through swift, uniform consequences over rehabilitative measures, predicated on the empirical observation that peer-enforced honor reduces violations more effectively than external monitoring in self-selecting communities.[26]Academics

Programs and Schools

Washington and Lee University structures its academic offerings across three primary divisions: The College, which serves as the liberal arts core; the Williams School of Commerce, Economics, and Politics, focused on undergraduate business and policy disciplines; and the School of Law, providing graduate legal education.[69][70] This model integrates specialized programs within a broader liberal arts framework, emphasizing interdisciplinary study and a unique three-term academic calendar.[69] The College offers 37 undergraduate majors and 29 minors spanning humanities, social sciences, natural sciences, fine arts, journalism, and STEM fields, with students pursuing Bachelor of Arts or Bachelor of Science degrees.[71][72] Disciplines include anthropology, biology, chemistry, computer science, English, history, mathematics, physics, and interdisciplinary options such as neuroscience and environmental studies.[71] Approximately half of undergraduates major in College programs, often combining them with minors in areas like creative writing or archaeology to foster critical thinking and broad intellectual development.[69] Established in 1905, the Williams School provides accredited undergraduate programs in commerce, economics, and politics, granting degrees such as the B.S. in accounting and B.A. in business administration.[73] About 50% of students enroll in its majors, which emphasize quantitative analysis, ethics, and real-world applications within a liberal arts context, distinguishing it as one of the few such embedded business schools at a top liberal arts university.[1] Politics majors within the school focus on governance, international relations, and policy, often intersecting with economics coursework.[74] The School of Law, operational since the 19th century, confers the Juris Doctor degree through a curriculum noted for its integration of practical training and ethical reasoning.[75] It admits students with strong academic records, typically reflected in mean entering GPAs around 3.56 and LSAT scores near 160, and maintains national accreditation.[76] The program enrolls roughly 400 students and prioritizes small classes and clinical experiences over traditional lecture formats.[75]Rankings, Reputation, and Outcomes

Washington and Lee University is ranked #21 among National Liberal Arts Colleges in the U.S. News & World Report 2026 edition, reflecting performance in factors such as graduation rates, faculty resources, and peer assessments.[1] In the Forbes 2026 America's Top Colleges ranking, it places #47 overall among universities, liberal arts colleges, and service academies, emphasizing alumni earnings, student debt, and return on investment.[77] Niche ranks it #4 among Best Liberal Arts Colleges in America for 2026, based on metrics including academics, value, and student surveys.[78] These positions have fluctuated in recent years; for instance, it ranked higher in some prior assessments but experienced variability due to changes in ranking methodologies.[79] The university's professional schools also receive recognition. The School of Law is tied for #36 in U.S. News & World Report's 2025 Best Law Schools, evaluated on employment outcomes, bar passage rates, and peer reputation.[80] It ranks #2 among private law schools for value and #5 nationally in two-year post-graduation employment outcomes per a 2025 National Jurist analysis.[81] Undergraduate outcomes demonstrate strong post-graduation success. The six-year graduation rate is 95%, among the highest nationally.[82] Graduates earn a median early-career salary of approximately $59,000, exceeding expectations for similar institutions by about $9,000.[83] Six years after graduation, alumni average $56,300 annually, rising to $89,000 after ten years.[84] For the law school, 98.1% of the class of 2023 obtained full-time, long-term positions requiring bar passage or advantaged by a J.D., with 95% for the class of 2024.[85][86] The university's reputation stems from its emphasis on the honor system, rigorous academics, and alumni network, which contribute to high employer regard and career placement.[87] A 2023 Wall Street Journal student poll ranked it first among all U.S. colleges for career preparation, based on perceptions of job readiness and networking.[88] This prestige is evidenced by consistent top-20 placements in credible national liberal arts rankings and strong alumni outcomes in fields like finance, law, and consulting.[87]Admissions, Financial Aid, and Enrollment Trends

Washington and Lee University employs a holistic admissions process emphasizing academic rigor, leadership potential, extracurricular engagement, and alignment with institutional values such as the Honor System. For the Class of 2029, the university received 8,969 applications—a record high—admitting 1,216 students for an acceptance rate of 13.6%, with 499 enrolling. Over the past decade, acceptance rates have fluctuated between 14% and 24%, reflecting rising applicant volume and sustained selectivity. The process includes Early Decision I, Early Decision II, QuestBridge, and Regular Decision options, with 290 of the Class of 2029 enrolling via early programs.[89][39][90] Standardized testing is optional, with 52% of the Class of 2029 submitting scores; the middle 50% ranged from 1450–1510 on the SAT and 33–34 on the ACT. Admitted students hail from 408 secondary schools, including 9% international applicants, 22% domestic students of color, 11% first-generation college attendees, 11% children of alumni, and 26% recruited athletes. This profile underscores a focus on diverse yet high-achieving cohorts committed to community involvement.[89][91] The university meets 100% of demonstrated financial need for all admitted undergraduates via grants and work-study, excluding loans from need-based packages. In October 2024, a $132 million endowment gift enabled adoption of need-blind admissions, removing family financial considerations from undergraduate evaluations starting with the Class of 2029. Among enrollees, 63% receive institutional grants averaging $66,084 annually, while 15% qualify for Pell Grants with an average total award of $71,792; overall, about 60–64% of first-year students access aid packages exceeding $67,000 on average. Only 13–15% of first-years receive Pell aid, indicating a predominantly non-low-income student body.[92][93][89][39] Undergraduate enrollment has stabilized at around 1,885 students annually over the last five years, with 1,886 full-time undergraduates in fall 2024 and 499 first-year additions projected for fall 2025. Law school enrollment averages 372. This consistency follows historical growth in applications and selectivity, with no significant fluctuations tied to external events in recent data. Total enrollment stands at approximately 2,277, with undergraduates comprising 83%.[39][1][94]Student Life

Traditions and Campus Culture

Washington and Lee University's campus culture emphasizes interpersonal courtesy and community engagement, rooted in longstanding customs that promote trust and familiarity among students. Central to this is the Speaking Tradition, an informal practice dating back over a century where students greet one another by name when passing on campus paths, fostering a sense of hospitality and reducing anonymity in daily interactions.[95][96] This custom, while challenged by modern distractions like wireless earbuds, remains a hallmark of the university's emphasis on personal accountability and social bonds, distinct from more impersonal environments at larger institutions.[97] A prominent quadrennial tradition is the Mock Convention, a student-led simulation of a presidential nominating convention held every four years for the party out of the White House, with a history of high predictive accuracy for nominees.[98] The 2024 event, focusing on the Republican contest, forecasted Donald Trump's nomination and featured speakers including Donald Trump Jr., Georgia Governor Brian Kemp, and Virginia Governor Glenn Youngkin, drawing national attention to campus political discourse.[99][100] Organized entirely by undergraduates, it involves detailed research, delegate selection, and logistical planning, serving as an experiential learning opportunity in civics and prediction modeling.[101] Annually, the Fancy Dress ball, inaugurated in 1907, stands as the university's premier social event, evolving from costumed gatherings to a black-tie gala typically held in March with elaborate themes, live performances, and decorations transforming the gymnasium into immersive settings.[102][103] Past iterations have included circus motifs with acrobats and bands, as in 2023's "The Greatest Show," attracting students, alumni, and guests for formal attire and dancing.[104] This tradition underscores a culture of refined social rituals, though it has occasionally intersected with debates over historical imagery tied to the university's namesake.[105] Overall, these elements contribute to a campus atmosphere described in university guidelines as courteous and visitor-welcoming, with students and faculty exchanging greetings as a norm, complemented by diverse religious observances and community involvement in the adjacent town of Lexington.[106][107] The culture prioritizes small-scale interactions in a residential setting where 74% of undergraduates live on campus, supporting traditions that reinforce collective identity amid rigorous academics.[108]Student Organizations and Activities