Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Lignin

View on Wikipedia

Lignin is a class of complex organic polymers that form key structural materials in the support tissues of most plants.[1] Lignins are particularly important in the formation of cell walls, especially in wood and bark, because they lend rigidity and do not rot easily. Chemically, lignins are polymers made by cross-linking phenolic precursors.[2]

History

[edit]Lignin was first mentioned in 1813 by the Swiss botanist A. P. de Candolle, who described it as a fibrous, tasteless material, insoluble in water and alcohol but soluble in weak alkaline solutions, and which can be precipitated from solution using acid.[3] He named the substance "lignine", which is derived from the Latin word lignum,[4] meaning wood. It is one of the most abundant organic polymers on Earth, exceeded only by cellulose and chitin. Lignin constitutes 30% of terrestrial non-fossil organic carbon[5] on Earth, and 20 to 35% of the dry mass of wood.[6]

Lignin is present in red algae, which suggest that the common ancestor of plants and red algae may have been pre-adapted to synthesize lignin. This finding also suggests that the original function of lignin may have been structural as it plays this role in the red alga Calliarthron, where it supports joints between calcified segments.[7]

Composition and structure

[edit]The composition of lignin varies from species to species. An example of composition from an aspen[8] sample is 63.4% carbon, 5.9% hydrogen, 0.7% ash (mineral components), and 30% oxygen (by difference),[9] corresponding approximately to the formula (C31H34O11)n.

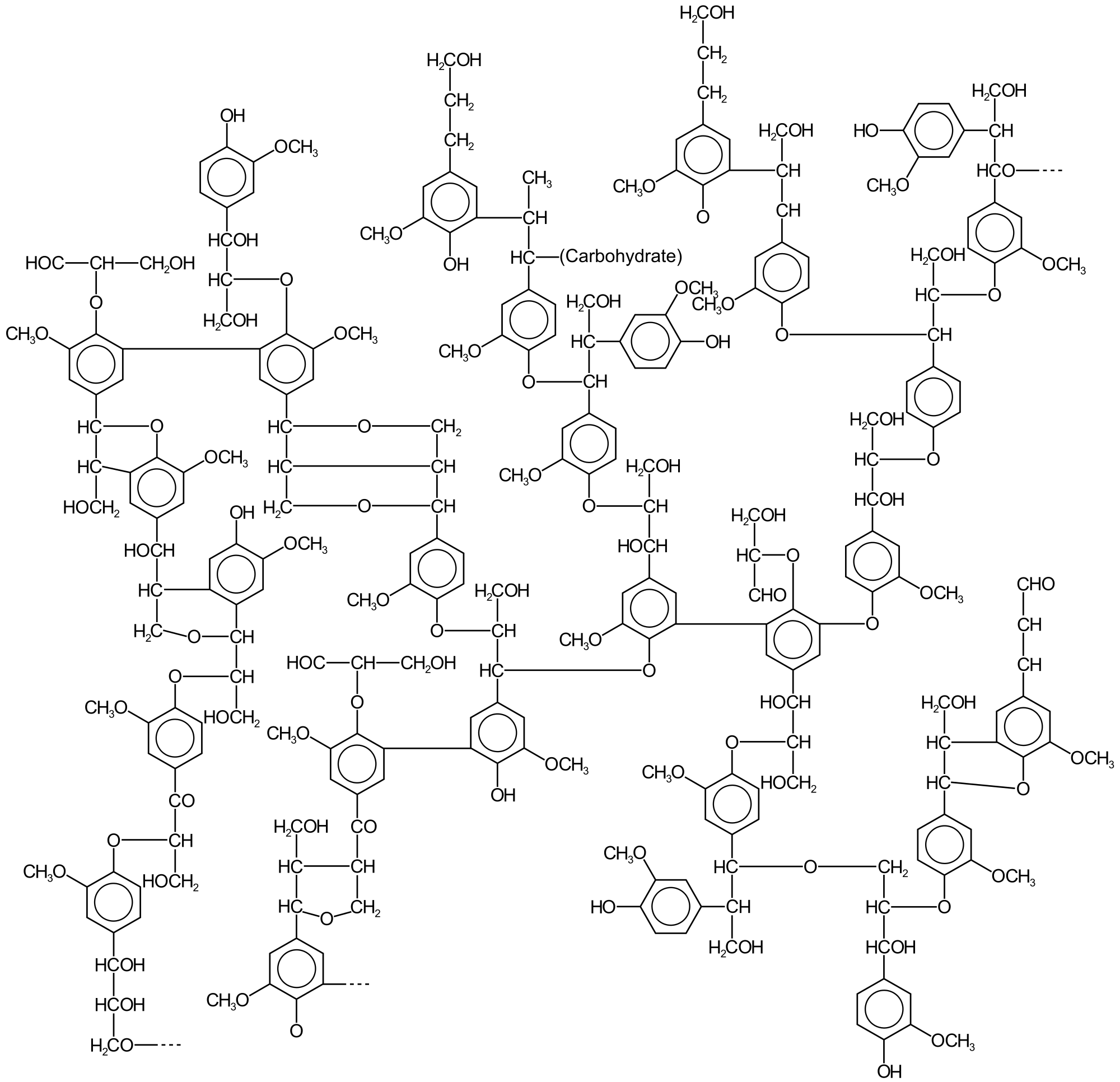

Lignin is a collection of highly heterogeneous polymers derived from a handful of precursor lignols. Heterogeneity arises from the diversity and degree of crosslinking between these lignols. The lignols that crosslink are of three main types, all derived from phenylpropane: coniferyl alcohol (3-methoxy-4-hydroxyphenylpropane; its radical, G, is sometimes called guaiacyl), sinapyl alcohol (3,5-dimethoxy-4-hydroxyphenylpropane; its radical, S, is sometimes called syringyl), and paracoumaryl alcohol (4-hydroxyphenylpropane; its radical, H, is sometimes called 4-hydroxyphenyl).[citation needed]

The relative amounts of the precursor "monomers" (lignols or monolignols) vary according to the plant source.[5] Lignins are typically classified according to their syringyl/guaiacyl (S/G) ratio. Lignin from gymnosperms is derived from the coniferyl alcohol, which gives rise to G upon pyrolysis. In angiosperms some of the coniferyl alcohol is converted to S. Thus, lignin in angiosperms has both G and S components.[10][11]

Lignin's molecular masses exceed 10,000 u. It is hydrophobic as it is rich in aromatic subunits. The degree of polymerisation is difficult to measure, since the material is heterogeneous. Different types of lignin have been described depending on the means of isolation.[12]

Many grasses have mostly G, while some palms have mainly S.[13] All lignins contain small amounts of incomplete or modified monolignols, and other monomers are prominent in non-woody plants.[14]

Biological function

[edit]Lignin fills the spaces in the cell wall between cellulose, hemicellulose, and pectin components, especially in vascular and support tissues: xylem tracheids, vessel elements and sclereid cells.[citation needed]

Lignin plays a crucial part in conducting water and aqueous nutrients in plant stems. The polysaccharide components of plant cell walls are highly hydrophilic and thus permeable to water, whereas lignin is more hydrophobic. The crosslinking of polysaccharides by lignin is an obstacle for water absorption to the cell wall. Thus, lignin makes it possible for the plant's vascular tissue to conduct water efficiently.[15] Lignin is present in all vascular plants,[16] but not in bryophytes, supporting the idea that the original function of lignin was restricted to water transport.

It is covalently linked to hemicellulose and therefore cross-links different plant polysaccharides, conferring mechanical strength to the cell wall and by extension the plant as a whole.[17] Its most commonly noted function is the support through strengthening of wood (mainly composed of xylem cells and lignified sclerenchyma fibres) in vascular plants.[18][19][20]

Finally, lignin also confers disease resistance by accumulating at the site of pathogen infiltration, making the plant cell less accessible to cell wall degradation.[21]

Economic significance

[edit]

Global commercial production of lignin is a consequence of papermaking. In 1988, more than 220 million tons of paper were produced worldwide.[22] Much of this paper was delignified; lignin comprises about 1/3 of the mass of lignocellulose, the precursor to paper. Lignin is an impediment to papermaking as it is colored, it yellows in air, and its presence weakens the paper. Once separated from the cellulose, it is burned as fuel. Only a fraction is used in a wide range of low volume applications where the form but not the quality is important.[23]

Mechanical, or high-yield pulp, which is used to make newsprint, still contains most of the lignin originally present in the wood. This lignin is responsible for newsprint's yellowing with age.[4] High quality paper requires the removal of lignin from the pulp. These delignification processes are core technologies of the papermaking industry as well as the source of significant environmental concerns.[citation needed]

In sulfite pulping, lignin is removed from wood pulp as lignosulfonates, for which many applications have been proposed.[24] They are used as dispersants, humectants, emulsion stabilizers, and sequestrants (water treatment).[25] Lignosulfonate was also the first family of water reducers or superplasticizers to be added in the 1930s as admixture to fresh concrete in order to decrease the water-to-cement (w/c) ratio, the main parameter controlling the concrete porosity, and thus its mechanical strength, its diffusivity and its hydraulic conductivity, all parameters essential for its durability. It has application in environmentally sustainable dust suppression agent for roads. Also, lignin can be used in making biodegradable plastic along with cellulose as an alternative to hydrocarbon-made plastics if lignin extraction is achieved through a more environmentally viable process than generic plastic manufacturing.[26]

Lignin removed by the kraft process is usually burned for its fuel value, providing energy to power the paper mill. Two commercial processes exist to remove lignin from black liquor for higher value uses: LignoBoost (Sweden) and LignoForce (Canada). Higher quality lignin presents the potential to become a renewable source of aromatic compounds for the chemical industry, with an addressable market of more than $130bn.[27]

Given that it is the most prevalent biopolymer after cellulose, lignin has been investigated as a feedstock for biofuel production and can become a crucial plant extract in the development of a new class of biofuels.[28][29]

Biosynthesis

[edit]Lignin biosynthesis begins in the cytosol with the synthesis of glycosylated monolignols from the amino acid phenylalanine. These first reactions are shared with the phenylpropanoid pathway. The attached glucose renders them water-soluble and less toxic. Once transported through the cell membrane to the apoplast, the glucose is removed, and the polymerisation commences.[30] Much about its anabolism is not understood even after more than a century of study.[5]

The polymerisation step, that is a radical-radical coupling, is catalysed by oxidative enzymes. Both peroxidase and laccase enzymes are present in the plant cell walls, and it is not known whether one or both of these groups participates in the polymerisation. Low molecular weight oxidants might also be involved. The oxidative enzyme catalyses the formation of monolignol radicals. These radicals are often said to undergo uncatalyzed coupling to form the lignin polymer.[31] An alternative theory invokes an unspecified biological control.[1]

Biodegradation

[edit]In contrast to other bio-polymers (e.g. proteins, DNA, and even cellulose), lignin resists degradation. It is immune to both acid- and base-catalyzed hydrolysis. The degradability varies with species and plant tissue type. For example, syringyl (S) lignin is more susceptible to degradation by fungal decay as it has fewer aryl-aryl bonds and a lower redox potential than guaiacyl units.[32][33] Because it is cross-linked with the other cell wall components, lignin minimizes the accessibility of cellulose and hemicellulose to microbial enzymes (e.g. Steric hindrance), leading to a reduced digestibility of biomass.[15]

Some ligninolytic enzymes include heme peroxidases such as lignin peroxidases, manganese peroxidases, versatile peroxidases, and dye-decolourizing peroxidases as well as copper-based laccases. Lignin peroxidases oxidize non-phenolic lignin, whereas manganese peroxidases only oxidize the phenolic structures. Dye-decolorizing peroxidases, or DyPs, exhibit catalytic activity on a wide range of lignin model compounds, but their in vivo substrate is unknown. In general, laccases oxidize phenolic substrates but some fungal laccases have been shown to oxidize non-phenolic substrates in the presence of synthetic redox mediators.[34][35]

Lignin degradation by fungi

[edit]Well-studied ligninolytic enzymes are found in Phanerochaete chrysosporium[36] and other white rot fungi. Some white rot fungi, such as Ceriporiopsis subvermispora, can degrade the lignin in lignocellulose, but others lack this ability. Most fungal lignin degradation involves secreted peroxidases. Many fungal laccases are also secreted, which facilitate degradation of phenolic lignin-derived compounds, although several intracellular fungal laccases have also been described. An important aspect of fungal lignin degradation is the activity of accessory enzymes to produce the H2O2 required for the function of lignin peroxidase and other heme peroxidases.[34]

Lignin degradation by bacteria

[edit]Bacteria lack most of the enzymes employed by fungi to degrade lignin, and lignin derivatives (aliphatic acids, furans, and solubilized phenolics) inhibit the growth of bacteria.[37] Yet, bacterial degradation can be quite extensive,[38] especially in aquatic systems such as lakes, rivers, and streams, where inputs of terrestrial material (e.g. leaf litter) can enter waterways. The ligninolytic activity of bacteria has not been studied extensively even though it was first described in 1930. Many bacterial DyPs have been characterized. Bacteria do not express any of the plant-type peroxidases (lignin peroxidase, Mn peroxidase, or versatile peroxidases), but three of the four classes of DyP are only found in bacteria. In contrast to fungi, most bacterial enzymes involved in lignin degradation are intracellular, including two classes of DyP and most bacterial laccases.[35]

In the environment, lignin can be degraded either biotically via bacteria or abiotically via photochemical alteration, and oftentimes the latter assists in the former.[39] In addition to the presence or absence of light, several of environmental factors affect the biodegradability of lignin, including bacterial community composition, mineral associations, and redox state.[40][41]

In shipworms, the lignin it ingests is digested by "Alteromonas-like sub-group" bacteria symbionts in the typhlosole sub-organ of its cecum.[42]

Pyrolysis

[edit]Pyrolysis of lignin during the combustion of wood or charcoal production yields a range of products, of which the most characteristic ones are methoxy-substituted phenols. Of those, the most important are guaiacol and syringol and their derivatives. Their presence can be used to trace a smoke source to a wood fire. In cooking, lignin in the form of hardwood is an important source of these two compounds, which impart the characteristic aroma and taste to smoked foods such as barbecue. The main flavor compounds of smoked ham are guaiacol, and its 4-, 5-, and 6-methyl derivatives as well as 2,6-dimethylphenol. These compounds are produced by thermal breakdown of lignin in the wood used in the smokehouse.[43]

Chemical analysis

[edit]The conventional method for lignin quantitation in the pulp industry is the Klason lignin and acid-soluble lignin test, which is standardized procedures. The cellulose is digested thermally in the presence of acid. The residue is termed Klason lignin. Acid-soluble lignin (ASL) is quantified by the intensity of its Ultraviolet spectroscopy. The carbohydrate composition may be also analyzed from the Klason liquors, although there may be sugar breakdown products (furfural and 5-hydroxymethylfurfural).[44]

A solution of hydrochloric acid and phloroglucinol is used for the detection of lignin (Wiesner test). A brilliant red color develops, owing to the presence of coniferaldehyde groups in the lignin.[45]

Thioglycolysis is an analytical technique for lignin quantitation.[46] Lignin structure can also be studied by computational simulation.[47]

Thermochemolysis (chemical break down of a substance under vacuum and at high temperature) with tetramethylammonium hydroxide (TMAH) or cupric oxide[48] has also been used to characterize lignins. The ratio of syringyl lignol (S) to vanillyl lignol (V) and cinnamyl lignol (C) to vanillyl lignol (V) is variable based on plant type and can therefore be used to trace plant sources in aquatic systems (woody vs. non-woody and angiosperm vs. gymnosperm).[49] Ratios of carboxylic acid (Ad) to aldehyde (Al) forms of the lignols (Ad/Al) reveal diagenetic information, with higher ratios indicating a more highly degraded material.[32][33] Increases in the (Ad/Al) value indicate an oxidative cleavage reaction has occurred on the alkyl lignin side chain which has been shown to be a step in the decay of wood by many white-rot and some soft rot fungi.[32][33][50][51][52]

Lignin and its models have been well examined by 1H and 13C NMR spectroscopy. Owing to the structural complexity of lignins, the spectra are poorly resolved and quantitation is challenging.[53]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b Saake, Bodo; Lehnen, Ralph (2007). "Lignin". Ullmann's Encyclopedia of Industrial Chemistry. Weinheim: Wiley-VCH. doi:10.1002/14356007.a15_305.pub3. ISBN 978-3527306732.

- ^ Lebo, Stuart E. Jr.; Gargulak, Jerry D.; McNally, Timothy J. (2001). "Lignin". Kirk-Othmer Encyclopedia of Chemical Technology. Kirk‑Othmer Encyclopedia of Chemical Technology. John Wiley & Sons, Inc. doi:10.1002/0471238961.12090714120914.a01.pub2. ISBN 978-0-471-23896-6. Retrieved 2007-10-14.

- ^ de Candolle, M.A.P. (1813). Theorie Elementaire de la Botanique ou Exposition des Principes de la Classification Naturelle et de l'Art de Decrire et d'Etudier les Vegetaux. Paris: Deterville. See p. 417.

- ^ a b E. Sjöström (1993). Wood Chemistry: Fundamentals and Applications. Academic Press. ISBN 978-0-12-647480-0.

- ^ a b c W. Boerjan; J. Ralph; M. Baucher (June 2003). "Lignin biosynthesis". Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 54 (1): 519–549. doi:10.1146/annurev.arplant.54.031902.134938. PMID 14503002.

- ^ "Lignin". Encyclopedia Brittanica. 2023-10-05. Retrieved 2023-10-26.

- ^ Martone, Pt; Estevez, Jm; Lu, F; Ruel, K; Denny, Mw; Somerville, C; Ralph, J (Jan 2009). "Discovery of Lignin in Seaweed Reveals Convergent Evolution of Cell-Wall Architecture". Current Biology. 19 (2): 169–75. Bibcode:2009CBio...19..169M. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2008.12.031. ISSN 0960-9822. PMID 19167225. S2CID 17409200.

- ^ In the referenced article, the species of aspen is not specified, only that it was from Canada.

- ^ Hsiang-Hui King; Peter R. Solomon; Eitan Avni; Robert W. Coughlin (Fall 1983). "Modeling Tar Composition in Lignin Pyrolysis" (PDF). Symposium on Mathematical Modeling of Biomass Pyrolysis Phenomena, Washington, D.C., 1983. p. 1. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2017-08-08. Retrieved 2024-01-29.

- ^ Letourneau, Dane R.; Volmer, Dietrich A. (2021-07-22). "Mass spectrometry-based methods for the advanced characterization and structural analysis of lignin: A review". Mass Spectrometry Reviews. 42 (1): 144–188. doi:10.1002/mas.21716. ISSN 0277-7037. PMID 34293221. S2CID 236200196.

- ^ Li, Laigeng; Cheng, Xiao Fei; Leshkevich, Jacqueline; Umezawa, Toshiaki; Harding, Scott A.; Chiang, Vincent L. (2001). "The Last Step of Syringyl Monolignol Biosynthesis in Angiosperms is Regulated by a Novel Gene Encoding Sinapyl Alcohol Dehydrogenase". The Plant Cell. 13 (7): 1567–1586. doi:10.1105/tpc.010111. PMC 139549. PMID 11449052.

- ^ "Lignin and its Properties: Glossary of Lignin Nomenclature". Dialogue/Newsletters Volume 9, Number 1. Lignin Institute. July 2001. Archived from the original on 2007-10-09. Retrieved 2007-10-14.

- ^ Kuroda K, Ozawa T, Ueno T (April 2001). "Characterization of sago palm (Metroxylon sagu) lignin by analytical pyrolysis". J Agric Food Chem. 49 (4): 1840–7. doi:10.1021/jf001126i. PMID 11308334. S2CID 27962271.

- ^ J. Ralph; et al. (2001). "Elucidation of new structures in lignins of CAD- and COMT-deficient plants by NMR". Phytochemistry. 57 (6): 993–1003. Bibcode:2001PChem..57..993R. doi:10.1016/S0031-9422(01)00109-1. PMID 11423146. Archived from the original on 2021-04-28. Retrieved 2018-12-29.

- ^ a b K.V. Sarkanen & C.H. Ludwig, eds. (1971). Lignins: Occurrence, Formation, Structure, and Reactions. New York: Wiley Intersci.

- ^ Isikgor, Furkan H.; Becer, C. Remzi (2015). "Lignocellulosic biomass: a sustainable platform for the production of bio-based chemicals and polymers". Polymer Chemistry. 6 (25): 4497–4559. arXiv:1602.01684. doi:10.1039/C5PY00263J. ISSN 1759-9954.

- ^ Chabannes, M.; et al. (2001). "In situ analysis of lignins in transgenic tobacco reveals a differential impact of individual transformations on the spatial patterns of lignin deposition at the cellular and subcellular levels". Plant J. 28 (3): 271–282. doi:10.1046/j.1365-313X.2001.01159.x. PMID 11722770.

- ^ Arms, Karen; Camp, Pamela S. (1995). Biology. Saunders College Pub. ISBN 978-0-03-050003-9.

- ^ Esau, Katharine (1977). Anatomy of Seed Plants. Wiley. ISBN 978-0-471-24520-9.

- ^ Wardrop; The (1969). "Eryngium sp.;". Aust. J. Bot. 17 (2): 229–240. doi:10.1071/bt9690229.

- ^ Bhuiyan, Nazmul H; Selvaraj, Gopalan; Wei, Yangdou; King, John (February 2009). "Role of lignification in plant defense". Plant Signaling & Behavior. 4 (2): 158–159. Bibcode:2009PlSiB...4..158B. doi:10.4161/psb.4.2.7688. ISSN 1559-2316. PMC 2637510. PMID 19649200.

- ^ Rudolf Patt et al. (2005). "Pulp". Paper and Pulp. Ullmann's Encyclopedia of Industrial Chemistry. Weinheim: Wiley-VCH. pp. 1–92. doi:10.1002/14356007.a18_545.pub4. ISBN 978-3-527-30673-2.

- ^ Higson, A; Smith, C (25 May 2011). "NNFCC Renewable Chemicals Factsheet: Lignin". Archived from the original on 20 July 2011.

- ^ "Uses of lignin from sulfite pulping". Archived from the original on 2007-10-09. Retrieved 2007-09-10.

- ^ Barbara A. Tokay (2000). "Biomass Chemicals". Ullmann's Encyclopedia Of Industrial Chemistry. doi:10.1002/14356007.a04_099. ISBN 978-3-527-30673-2.

- ^ Patt, Rudolf; Kordsachia, Othar; Süttinger, Richard; Ohtani, Yoshito; Hoesch, Jochen F.; Ehrler, Peter; Eichinger, Rudolf; Holik, Herbert; Hamm, Udo; Rohmann, Michael E.; Mummenhoff, Peter; Petermann, Erich; Miller, Richard F.; Frank, Dieter; Wilken, Renke; Baumgarten, Heinrich L.; Rentrop, Gert-Heinz (2000). "Paper and Pulp". Ullmann's Encyclopedia of Industrial Chemistry. Weinheim: Wiley-VCH. doi:10.1002/14356007.a18_545. ISBN 3527306730.

- ^ "Frost & Sullivan: Full Speed Ahead for the Lignin Market with High-Value Opportunities as early as 2017".

- ^ Folkedahl, Bruce (2016), "Cellulosic ethanol: what to do with the lignin", Biomass, retrieved 2016-08-10.

- ^ Abengoa (2016-04-21), The importance of lignin for ethanol production, retrieved 2016-08-10.

- ^ Samuels AL, Rensing KH, Douglas CJ, Mansfield SD, Dharmawardhana DP, Ellis BE (November 2002). "Cellular machinery of wood production: differentiation of secondary xylem in Pinus contorta var. latifolia". Planta. 216 (1): 72–82. Bibcode:2002Plant.216...72A. doi:10.1007/s00425-002-0884-4. PMID 12430016. S2CID 20529001.

- ^ Davin, L.B.; Lewis, N.G. (2005). "Lignin primary structures and dirigent sites". Current Opinion in Biotechnology. 16 (4): 407–415. doi:10.1016/j.copbio.2005.06.011. PMID 16023847.

- ^ a b c Vane, C. H.; et al. (2003). "Biodegradation of Oak (Quercus alba) Wood during Growth of the Shiitake Mushroom (Lentinula edodes): A Molecular Approach". Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry. 51 (4): 947–956. doi:10.1021/jf020932h. PMID 12568554.

- ^ a b c Vane, C. H.; et al. (2006). "Bark decay by the white-rot fungus Lentinula edodes: Polysaccharide loss, lignin resistance and the unmasking of suberin". International Biodeterioration & Biodegradation. 57 (1): 14–23. Bibcode:2006IBiBi..57...14V. doi:10.1016/j.ibiod.2005.10.004.

- ^ a b Gadd, Geoffrey M; Sariaslani, Sima (2013). Advances in applied microbiology. Vol. 82. Oxford: Academic. pp. 1–28. ISBN 978-0-12-407679-2. OCLC 841913543.

- ^ a b de Gonzalo, Gonzalo; Colpa, Dana I.; Habib, Mohamed H.M.; Fraaije, Marco W. (2016). "Bacterial enzymes involved in lignin degradation". Journal of Biotechnology. 236: 110–119. doi:10.1016/j.jbiotec.2016.08.011. PMID 27544286.

- ^ Tien, M (1983). "Lignin-Degrading Enzyme from the Hymenomycete Phanerochaete chrysosporium Burds". Science. 221 (4611): 661–3. Bibcode:1983Sci...221..661T. doi:10.1126/science.221.4611.661. PMID 17787736. S2CID 8767248.

- ^ Cerisy, Tristan (May 2017). "Evolution of a Biomass-Fermenting Bacterium To Resist Lignin Phenolics". Applied and Environmental Microbiology. 83 (11). Bibcode:2017ApEnM..83E.289C. doi:10.1128/AEM.00289-17. PMC 5440714. PMID 28363966.

- ^ Pellerin, Brian A.; Hernes, Peter J.; Saraceno, JohnFranco; Spencer, Robert G. M.; Bergamaschi, Brian A. (May 2010). "Microbial degradation of plant leachate alters lignin phenols and trihalomethane precursors". Journal of Environmental Quality. 39 (3): 946–954. Bibcode:2010JEnvQ..39..946P. doi:10.2134/jeq2009.0487. ISSN 0047-2425. PMID 20400590.

- ^ Hernes, Peter J. (2003). "Photochemical and microbial degradation of dissolved lignin phenols: Implications for the fate of terrigenous dissolved organic matter in marine environments". Journal of Geophysical Research. 108 (C9): 3291. Bibcode:2003JGRC..108.3291H. doi:10.1029/2002JC001421. Retrieved 2018-11-27.

- ^ "Persistence of Soil Organic Matter as an Ecosystem Property". ResearchGate. Retrieved 2018-11-27.

- ^ Dittmar, Thorsten (2015-01-01). "Reasons Behind the Long-Term Stability of Dissolved Organic Matter". Biogeochemistry of Marine Dissolved Organic Matter. pp. 369–388. doi:10.1016/B978-0-12-405940-5.00007-8. ISBN 978-0-12-405940-5.

- ^ Goodell, Barry; Chambers, James; Ward, Doyle V.; Murphy, Cecelia; Black, Eileen; Mancilio, Lucca Bonjy Kikuti; Perez- Gonzalez, Gabriel; Shipway, J. Reuben (2024). "First report of microbial symbionts in the digestive system of shipworms; wood boring mollusks". International Biodeterioration & Biodegradation. 192 105816. Bibcode:2024IBiBi.19205816G. doi:10.1016/j.ibiod.2024.105816.

- ^ Wittkowski, Reiner; Ruther, Joachim; Drinda, Heike; Rafiei-Taghanaki, Foroozan (1992). Formation of smoke flavor compounds by thermal lignin degradation. ACS Symposium Series (Flavor Precursors). Vol. 490. pp. 232–243. ISBN 978-0-8412-1346-3.

- ^ "TAPPI. T 222 om-02 – Acid-insoluble lignin in wood and pulp" (PDF).

- ^ Harkin, John M. (November 1966). "Lignin production and detection in wood" (PDF). U.S. Forest Service Research. Note FPL-0148. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2020-03-05. Retrieved 2012-12-30.

- ^ Lange, B. M.; Lapierre, C.; Sandermann, Jr (1995). "Elicitor-Induced Spruce Stress Lignin (Structural Similarity to Early Developmental Lignins)". Plant Physiology. 108 (3): 1277–1287. doi:10.1104/pp.108.3.1277. PMC 157483. PMID 12228544.

- ^ Glasser, Wolfgang G.; Glasser, Heidemarie R. (1974). "Simulation of Reactions with Lignin by Computer (Simrel). II. A Model for Softwood Lignin". Holzforschung. 28 (1): 5–11, 1974. doi:10.1515/hfsg.1974.28.1.5. S2CID 95157574.

- ^ Hedges, John I.; Ertel, John R. (February 1982). "Characterization of lignin by gas capillary chromatography of cupric oxide oxidation products". Analytical Chemistry. 54 (2): 174–178. doi:10.1021/ac00239a007. ISSN 0003-2700.

- ^ Hedges, John I.; Mann, Dale C. (1979-11-01). "The characterization of plant tissues by their lignin oxidation products". Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta. 43 (11): 1803–1807. Bibcode:1979GeCoA..43.1803H. doi:10.1016/0016-7037(79)90028-0. ISSN 0016-7037.

- ^ Vane, C. H.; et al. (2001). "The effect of fungal decay (Agaricus bisporus) on wheat straw lignin using pyrolysis–GC–MS in the presence of tetramethylammonium hydroxide (TMAH)". Journal of Analytical and Applied Pyrolysis. 60 (1): 69–78. Bibcode:2001JAAP...60...69V. doi:10.1016/s0165-2370(00)00156-x.

- ^ Vane, C. H.; et al. (2001). "Degradation of Lignin in Wheat Straw during Growth of the Oyster Mushroom (Pleurotus ostreatus) Using Off-line Thermochemolysis with Tetramethylammonium Hydroxide and Solid-State 13C NMR". Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry. 49 (6): 2709–2716. doi:10.1021/jf001409a. PMID 11409955.

- ^ Vane, C. H.; et al. (2005). "Decay of cultivated apricot wood (Prunus armeniaca) by the ascomycete Hypocrea sulphurea, using solid state 13C NMR and off-line TMAH thermochemolysis with GC–MS". International Biodeterioration & Biodegradation. 55 (3): 175–185. doi:10.1016/j.ibiod.2004.11.004.

- ^ Ralph, John; Landucci, Larry L. (2010). "NMR of Lignin and Lignans". Lignin and Lignans: Advances in Chemistry. Boca Raton, FL: Taylor & Francis. pp. 137–244. ISBN 978-1-57444-486-5.

Further reading

[edit]- Freudenberg, K. & Nash, A. C., eds. (1968). Constitution and Biosynthesis of Lignin. Berlin: Springer-Verlag.

- Lignins: Occurrence, formation, structure and reactions; edited by K. V. Sarkanen and C. H. Ludwig, John Wiley & Sons, Inc., New York, 1971

External links

[edit]Lignin

View on GrokipediaIntroduction

Definition and Occurrence

Lignin is a complex, heterogeneous aromatic polymer derived from phenylpropanoid precursors, serving as a key structural component in plant cell walls.[4] It is the second most abundant biopolymer on Earth after cellulose,[5] accounting for approximately 30% of the organic carbon in the biosphere.[6] Lignin occurs primarily as a major constituent in vascular plants, where it makes up 20-30% of the dry weight, especially in woody tissues such as xylem.[7] Its content varies between plant groups, typically reaching about 30% in gymnosperms and 20% in angiosperms, reflecting differences in wood composition and density.[8] While lignin is absent in non-vascular plants like mosses, lignin-like compounds have been identified in minor amounts in certain algae, such as red algae and some seaweeds, suggesting early evolutionary precursors.[9] The evolutionary significance of lignin lies in its role in enabling land plants to adapt to terrestrial environments by providing mechanical support for upright growth and facilitating efficient water transport through vascular tissues.[10] This innovation allowed early tracheophytes to achieve greater height and complexity, contributing to the diversification of vascular flora during the Devonian period.[8]Physical and Chemical Properties

Lignin exists as an amorphous solid polymer with a high molecular weight, typically ranging from 10,000 to 20,000 Da in technical lignins isolated from various sources. This high molecular weight contributes to its structural rigidity and resistance to mechanical stress. Due to its complex, cross-linked nature, lignin is insoluble in water but demonstrates solubility in certain organic solvents, such as dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO), and in alkaline media like sodium hydroxide solutions. These solubility characteristics stem from its polar hydroxyl groups and non-polar aromatic components, influencing its processing in industrial applications. Chemically, lignin is distinguished by its aromatic and polyphenolic composition, which results in strong ultraviolet (UV) absorption, peaking at approximately 280 nm. This property arises from the conjugated π-electron systems in its aromatic rings and is commonly exploited for quantitative analysis via UV spectroscopy. Lignin exhibits notable reactivity toward oxidants, including enzymes like laccases and chemical agents such as hydrogen peroxide, enabling controlled depolymerization or functionalization. Additionally, it displays thermal stability up to 200–250°C under inert atmospheres, after which pyrolysis and decomposition occur, releasing volatile compounds. The physical and chemical properties of lignin exhibit significant variability based on the botanical origin of the plant material. For instance, softwood-derived lignin, predominant in coniferous species, tends to have higher hydrophobicity and greater thermal stability compared to hardwood lignin from deciduous trees, owing to differences in subunit composition and cross-linking density. Hardwood lignin, conversely, often shows enhanced solubility in organic solvents due to a higher proportion of methoxylated units. These source-dependent variations affect lignin's processability and potential uses in materials science.History

Discovery and Isolation

The discovery of lignin traces back to the early 19th century, when botanists began investigating the non-carbohydrate components of wood. In 1813, Swiss botanist Augustin Pyramus de Candolle first described lignin as a fibrous, tasteless substance insoluble in water and alcohol, distinguishing it as the primary non-cellulosic residue in woody tissues. This observation laid the groundwork for recognizing lignin as a distinct entity separate from cellulose, though its chemical nature remained unclear at the time. A significant advancement occurred in 1838, when French chemist Anselme Payen isolated a material he termed "lignine" from spruce wood. Payen achieved this by treating wood with nitric acid to dissolve carbohydrates, followed by an alkaline solution, resulting in an insoluble residue that constituted about one-quarter of the wood's dry weight.[11] This method marked the first practical isolation of lignin, highlighting its resistance to acid and base hydrolysis compared to cellulose and hemicellulose.[12] Early isolation techniques primarily relied on acid hydrolysis to separate lignin from lignocellulosic matrices. In 1897, Swedish chemist Peter Klason developed a method using 72% sulfuric acid (later refined to 66%) to hydrolyze polysaccharides, yielding an acid-insoluble residue known as Klason lignin, which provided a quantitative measure of lignin's content in wood.[13] Concurrently, alkaline extraction emerged in the pulp industry as a complementary approach, employing sodium hydroxide or other bases to solubilize lignin under heat and pressure, facilitating its removal during papermaking processes.[14] By the early 1900s, British chemists Charles F. Cross and Edward J. Bevan advanced the understanding of lignin as a distinct polymeric substance through their extensive studies on wood chemistry. In their seminal works, they proposed that lignin forms via condensation reactions involving phenolic precursors, solidifying its status as a unique, non-saccharidic polymer encrusting cellulosic fibers.[15]Evolution of Structural Understanding

The structural understanding of lignin evolved through successive models that refined its conceptualization from simple units to a complex, heterogeneous polymer, driven by advances in analytical techniques. In the 1930s, Karl Freudenberg established the foundational arylpropane (C9) unit as the basic building block of lignin based on degradative analyses of spruce wood, proposing an initial hypothesis of irregular polymerization without a defined repeating motif.[16] By the 1950s, Freudenberg advanced this to a random polymer model, suggesting that lignin forms via non-enzymatic, radical-mediated dehydrogenative coupling of monolignols like coniferyl alcohol, resulting in a disordered network lacking stereoregularity or optical activity.[17] This model, supported by in vitro synthesis of dehydrogenation polymers (DHPs) mimicking natural lignin, emphasized combinatorial linkage formation over templated assembly.[18] Concurrently in the 1950s, Erik Adler proposed a more ordered linear linkage model specifically for spruce (softwood) lignin, depicting it as predominantly chain-like structures composed of guaiacyl units connected mainly through β-aryl ether bonds, derived from quantitative studies of alkaline nitrobenzene oxidation and periodate degradation products.[19] Adler's model highlighted a higher degree of regularity than Freudenberg's random hypothesis, estimating that ether linkages outnumbered carbon-carbon bonds and attributing about 60% of interunit connections to β-O-4 types based on yield data from selective cleavage reactions.[16] Mid-20th-century progress solidified the predominance of β-O-4 (arylglycerol-β-aryl ether) linkages through degradative techniques, including acidolysis (yielding Hibbert's ketones) and alkaline oxidation, which collectively indicated that these structures constitute 45–60% of linkages in gymnosperm lignins, with subordinate roles for β-5, 5-5', and β-β' bonds.[20] These findings, building on Freudenberg and Adler's frameworks, shifted emphasis from purely random or linear architectures to a hybrid where β-O-4 units form the core scaffold, enabling partial predictability in reactivity despite overall irregularity.[21] From the 1980s to the 2000s, nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectroscopy revolutionized analysis by providing non-destructive, in situ insights, confirming lignin's branched and heterogeneous architecture with diverse monolignol ratios (e.g., guaiacyl-dominant in softwoods, syringyl-guaiacyl in hardwoods) and a mix of linear and cross-linked domains. Two-dimensional NMR techniques, such as HSQC, quantified linkage distributions—revealing β-O-4 at 50–70%, alongside 10–20% condensed structures—across native and milled wood lignins, underscoring spatial variability within cell walls.[21] Post-2010 genomic studies have further illuminated structural variability by linking monolignol pathway genes (e.g., PAL, 4CL, CAD) to compositional differences, showing how allelic variations and expression patterns in diverse species yield tailored lignin architectures for environmental adaptation.[22]Chemical Structure and Composition

Monomeric Units

Lignin is primarily composed of three canonical monolignols: p-coumaryl alcohol (also known as H-unit, with the chemical formula ), coniferyl alcohol (G-unit, ), and sinapyl alcohol (S-unit, ).[22] These monolignols are phenylpropanoid alcohols derived from the shikimate pathway and differ in their degree of methoxylation at the 3- and 5-positions of the aromatic ring.[23] p-Coumaryl alcohol features no methoxy groups, coniferyl alcohol has one at the 3-position, and sinapyl alcohol has two at the 3- and 5-positions.[24] The proportions of these monolignols vary significantly across plant taxa, influencing lignin's overall structure and properties. In gymnosperms, such as softwoods, lignin is predominantly composed of G-units (derived from coniferyl alcohol), typically accounting for 90-95% of the polymer, with minor contributions from H-units.[25] In contrast, angiosperms, particularly hardwoods, feature a mixture of G- and S-units, where S-units (from sinapyl alcohol) often predominate at 45-55%, alongside 20-30% G-units and trace H-units.[26] Grasses and herbaceous plants exhibit more balanced H:G:S ratios with significant H-type contributions (including derivatives like p-coumarates), approximately 20:40:40, reflecting adaptations to their environments.[27] Beyond the primary monolignols, lignin incorporates derivatives such as 5-hydroxyconiferyl alcohol, a catechol monolignol prevalent in grasses, which arises from the hydroxylation of coniferyl alcohol precursors and contributes to the diversity of lignin units in monocots.[28] In native lignin, monolignol aldehydes (e.g., p-coumaraldehyde, coniferaldehyde, sinapaldehyde) and acids (e.g., p-coumaric, ferulic, sinapic acids) are also incorporated, often as end-groups or through direct polymerization, enhancing the polymer's chemical heterogeneity and reactivity.[29][30] These non-canonical units can constitute up to 10-20% in certain species, particularly where biosynthetic pathways are perturbed or specialized.[31]Polymer Linkages and Architecture

Lignin is formed through the polymerization of monolignol precursors, primarily via ether and carbon-carbon interunit linkages that create a complex three-dimensional network. The most prevalent linkage is the β-O-4 (aryl glycerol-β-aryl ether) type, accounting for 50–65% of linkages in softwood lignins and 50–65% in hardwood lignins. Other significant linkages include β-5 (phenylcoumaran, 9–12% in softwood and 3–11% in hardwood), β-β (resinol, 2–6% in softwood and 3–16% in hardwood), 5-5 (biphenyl, 2.5–11% in softwood and <1–4% in hardwood), and 4-O-5 (diaryl ether, 2–8% in softwood and 2–7% in hardwood). These relative abundances vary by plant type due to differences in monolignol composition, with softwoods dominated by guaiacyl units favoring more condensed C-C linkages like β-5 and 5-5, while hardwoods incorporate syringyl units that promote higher β-O-4 ether content.[32] The architecture of lignin is characterized by a highly branched and cross-linked structure, arising from the diversity of interunit linkages, particularly the carbon-carbon bonds (β-5, 5-5, β-β) that form recalcitrant nodes resistant to degradation. This results in a heterogeneous polymer with no fixed molecular formula, as the sequence and branching patterns differ across plant species and even within tissues. The degree of polymerization typically ranges from 50 to 100 monolignol units, contributing to molecular weights of several thousand daltons, though the networked nature leads to effective chain lengths that vary widely.[32][33] Lignin is often modeled as a random copolymer of monolignols connected by these linkage types, with computational and graphical representations illustrating the probabilistic assembly of linear chains interrupted by branches and cross-links. For instance, schematic diagrams depict β-O-4 as the dominant linear motif flanked by condensed structures like 5-5 biphenyls at branch points, emphasizing the irregular, amorphous topology rather than a regular repeating unit. Such models facilitate understanding of lignin's structural variability without implying a uniform sequence.[32]| Linkage Type | Softwood (%) | Hardwood (%) |

|---|---|---|

| β-O-4 | 50–65 | 50–65 |

| β-5 | 9–12 | 3–11 |

| β-β | 2–6 | 3–16 |

| 5-5 | 2.5–11 | <1–4 |

| 4-O-5 | 2–8 | 2–7 |