Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Merkit

View on WikipediaThis article needs additional citations for verification. (December 2011) |

Key Information

| Part of a series on the |

| History of Mongolia |

|---|

|

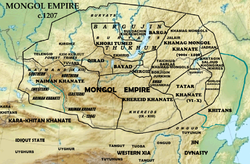

The Merkit (/ˈmɜːrkɪt/; Mongolian: [ˈmircɪt]; lit. 'Wise Ones') was one of the five major tribal confederations of Mongol[2][3][4][5] or Turkic origin[6][7][note 2] in the 12th-century Mongolian Plateau.

The Merkits lived in the basins of the Selenga and lower Orkhon River (modern south Buryatia, Bulgan Province and Selenge Province).[9] After a struggle of over 20 years, they were defeated in 1200 by Genghis Khan and their lands were incorporated into the Mongol Empire.

Etymology

[edit]The word Merkit (Merged) with a hard "g" is a plural form derived from the Mongolian word mergen (мэргэн), which means both "wise" and "skillful marksperson", e.g. adept in the use of bow and arrow. The word is also used in many phrases in which it connotes magic, oracles, divination, augury, or religious power. Mongolian language has no clear morphological or grammatical distinction between nouns and adjectives, so mergen may mean "a sage" as much as "wise" or mean "skillful" just as much as "a master". Merged becomes plural as in "wise ones" or "skillful markspeople". In the general sense, mergen usually denotes someone who is skillful and wise in their affairs.[citation needed]

Three Merkits

[edit]The Merkits were a confederation of three tribes, inhabiting the basin of the Selenga and Orkhon Rivers.

- The Uduyid Merkits lived in Buur-kheer, near the lower Orkhon River;

- The Uvas Merkits lived in Tar, between the Orkhon and Selenge Rivers;

- The Khaad Merkits ("Kings" Merkits) lived in Kharaji-kheer, on the Selenge River.

Relations

[edit]The Merkits established contact with the Mongol Confederation and Keraites. They were related to Naimans, Khitans,[10] Telengits and Kirghiz.[11]

According to Rashid al-Din Hamadani, the Merkits were a branch of the Mongols.[12] Western European authors of the 13th century mention the Merkits. They believed that they shared a similar appearance and spoke the same language with other Mongol tribes.[13]

Conflict with Genghis Khan

[edit]Temüjin's mother Hoelun, originally from the Olkhonud, had been engaged to the Merkit chief Yehe Chiledu. She was abducted by Temüjin's father Yesugei, while being escorted home by Yehe Chiledu.

In turn, Temüjin's new wife Börte was kidnapped by Merkit raiders from their campsite by the Onon river around 1181 and given to one of their warriors the brother of Yehe Chiledu named Chilger-Bökö. Temüjin, supported by his brother (not blood-related) Jamukha and his khan etseg ('khan father') Toghrul of the Keraites, attacked the Merkit and rescued Börte within the year. The Merkits were dispersed after this attack. Shortly thereafter she gave birth to a son named Jochi. Temüjin accepted Jochi as his eldest son, but the question lingered throughout Jochi's life of whether he was the son of Genghis Khan or Chilger-Bökö. These incidents caused a strong animosity between Temüjin's family and the Merkits. From 1191 to 1207, Temujin fought the Merkits five times.

By the time he had united the other Mongol tribes and received the title Genghis Khan in 1206, the Merkits seem to have disappeared as an ethnic group. Those who survived were absorbed by other Mongol (Oirats,[14] Buryats,[15] Khalkhas[16]) and Turkic tribes (Kazakhs, Kyrgyzes) and others who fled to the Kipchaks mixed with them. In 1215–1218, Jochi and Subutai crushed the remnants of them under their former leader Toghta Beki's family. The Mongols clashed with the Kankalis or the Kipchaks because they had sheltered the Merkit.

Genghis Khan had a Merkit khatun (queen) named Khulan. She died while Mongol forces besieged Ryazan in 1236.

Late Merkits

[edit]A few Merkits achieved prominent positions among the Mongols. Great Khan Guyuk's beloved khatun Oghul Qaimish, who was a regent from 1248 to 1251, was a Merkit woman. The traditionalist Bayan and his nephew Toqto'a served as grand chancellors of the Yuan dynasty.

Notes

[edit]- ^ Toqto'a Beki was the principal chieftain of the Uduyid Merkits. His younger brothers included Yehe Chiledu, who had originally been engaged to Hö'elün, the mother of Temüjin (Genghis Khan), before Yesugei married her under unclear circumstances; and Chilger-Bökö, a subordinate chieftain known for kidnapping Temüjin's wife Börte and possibly raping her, which may have led to questions over the paternity of Genghis Khan's eldest son Jochi.[1]

- ^ They were always counted as a part of the Mongols within the Mongol Empire, however, some scholars believe that they were Turkic people.[8]

References

[edit]- ^ Atwood 2004.

- ^ History of the Mongolian People's Republic. — Nauka Pub. House, Central Dept. of Oriental Literature, 1973. — p. 99.

- ^ Jeffrey Tayler. Murderers in Mausoleums: Riding the Back Roads of Empire Between Moscow and Beijing. — Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2009. — p. 1. — ISBN 9780547523828.

- ^ Bertold Spuler. The Muslim world: a historical survey. — Brill Archive, 1969. — p. 118.

- ^ Elza-Bair Mataskovna Gouchinova. The Kalmyks. — Routledge, 2013. — p. 10. — ISBN 9781135778873.

- ^ Soucek, Svat. A History of Inner Asia. — Cambridge University Press, 2000. — p. 104. — ISBN 978-0521657044.

- ^ Гурулёв С. А. Реки Байкала: Происхождение названий. – Иркутск: Восточно-Сибирское книжное издательство, 1989 – 122 с. ISBN 5-7424-0286-4

- ^ Christopher P. Atwood – Encyclopedia of Mongolia and the Mongol Empire ISBN 9780816046713, Facts on File, Inc. 2004.

- ^ History of Mongolia, Volume II, 2003

- ^ Weatherford, Jack (2005). Genghis Khan and the Making of the Modern World. Crown/Archetype. p. 12. ISBN 978-0-307-23781-1.

- ^ Акеров Т. А. Великий Кыргызский каганат: Роль этнополитических факторов в консолидации кочевых племен Притяньшанья и сопредельных регионов (VIII—XIV вв.). – Баку: Институт истории и культурного наследия Национальной академии наук Кыргызской Республики, 2012. – P. 40-42. – ISBN 5-7424-0286-4

- ^ Jamiʻuʼt-tawarikh. Compendium of chronicles. A History of the Mongols. Part One / Translated and Annotated by W. M. Thackston. Harvard university. 1998. p. 52.

- ^ Ушницкий В. В. (2013). "Загадка племени меркитов: проблема происхождения и потомства". Вестник Томского государственного университета. История (in Russian) (1 (21)): 191–195.

- ^ Авляев, Г. О. (2002). Происхождение калмыцкого народа (in Russian). Калм. кн. изд-во. p. 13.

- ^ Ушницкий В. В. (2009). "Исчезнувшее племя меркитов (мекритов): к вопросу о происхождении и истории". Вестник НГУ. Серия: История, филология (in Russian) (3): 212–221.

- ^ Аюудайн, Очир (2016). Монгольские этнонимы: вопросы происхождения и этнического состава монгольских народов (in Russian). КИГИ РАН. p. 109.