Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Nanyue

View on Wikipedia

Key Information

| Nanyue | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chinese name | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Chinese | 南越 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Hanyu Pinyin | Nányuè | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Jyutping | Naam4 Jyut6 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Literal meaning | "Southern Yue" | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Vietnamese name | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Vietnamese alphabet | Nam Việt | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Chữ Hán | 南越 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Zhuang name | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Zhuang | Namz Yied | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Nanyue (Chinese: 南越[1] or 南粵[2]; pinyin: Nányuè; Jyutping: Naam4 Jyut6; lit. 'Southern Yue', Vietnamese: Nam Việt, Zhuang: Namz Yied),[3] was an ancient kingdom founded in 204 BC by the Chinese general Zhao Tuo, whose family (known in Vietnamese as the Triệu dynasty) continued to rule until 111 BC.[4][5] Nanyue's geographical expanse covered the modern Chinese subdivisions of Guangdong,[6] Guangxi,[6] Hainan,[7] Hong Kong,[7] Macau,[7] southern Fujian[8] and central to northern Vietnam.[6] Zhao Tuo, then Commander of Nanhai Commandery of the Qin dynasty, established Nanyue in 204 BC after the collapse of the Qin dynasty. At first, it consisted of the commanderies of Nanhai, Guilin, and Xiang.

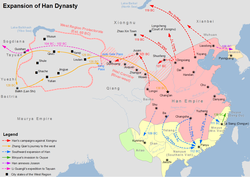

Nanyue and its rulers had an adversarial relationship with the Han dynasty, which referred to Nanyue as a vassal state while in practice it was autonomous. Nanyue rulers sometimes paid symbolic obeisance to the Han dynasty but referred to themselves as emperor. In 113 BC, fourth-generation leader Zhao Xing sought to have Nanyue formally included as part of the Han Empire. His prime minister Lü Jia objected vehemently and subsequently killed Zhao Xing, installing his elder brother Zhao Jiande on the throne and forcing a confrontation with the Han dynasty. The next year, Emperor Wu of Han sent 100,000 troops to war against Nanyue. By the year's end, the army had destroyed Nanyue and established Han rule. The dynastic state lasted 93 years and had five generations of monarchs.

The existence of Nanyue allowed the Lingnan region to avoid the chaos and hardship surrounding the collapse of the Qin dynasty experienced by the northern, predominantly Han Chinese regions. The kingdom was founded by leaders originally from the Central Plain of China and were all of Han Chinese in origin.[5] They were responsible for bringing Chinese-style bureaucracy and handicraft techniques to inhabitants of southern regions, as well as knowledge of the Chinese language and writing system. Nanyue rulers promoted a policy of "Harmonizing and Gathering the Hundred Yue tribes" (Chinese: 和集百越), and encouraged ethnic Han to immigrate from the Yellow River region to the south. Nanyue rulers were then not against the assimilation of Yue and Han cultures.[9]

In Vietnam, the rulers of Nanyue are referred to as the Triệu dynasty. The name "Vietnam" (Việt Nam) is derived and reversed from Nam Việt, the Vietnamese pronunciation of Nanyue.[10] In traditional Vietnamese historiography, important works such as the Đại Việt sử ký considered Nanyue to be a legitimate state of Vietnam and the official starting point of their history. However, starting in the 18th century, the view that Nanyue was not a legitimate Vietnamese state and Zhao Tuo was a foreign invader started gaining traction. After World War II, this became the mainstream view among Vietnamese historians in North Vietnam and after Vietnam was reunified, it became the official state orthodoxy promoted by the ruling Vietnamese Communist Party. Nanyue was removed from the national history while Zhao Tuo was established as a foreign invader.[11]

History

[edit]| Part of a series on the |

| History of China |

|---|

| History of Vietnam |

|---|

|

|

|

A detailed history of Nanyue was written in Records of the Grand Historian by Han dynasty historian Sima Qian. It is mostly contained in section (juan) 113, Ordered Annals of Nanyue (Chinese: 南越列傳; pinyin: Nányuè Liè Zhuàn; Jyutping: Naam4jyut6 Lit6 Zyun2).[12] A similar record is also found in the Book of Han Volume 95: The Southwest Peoples, Two Yues, and Chaoxian.[13]

Founding

[edit]Qin southward expansion (218 BC)

[edit]

After Qin Shi Huang conquered the six other Chinese kingdoms of Han, Zhao, Wei, Chu, Yan, and Qi, he turned his attention to the Xiongnu tribes of the north and west and the Hundred Yue peoples of what is now southern China. Around 218 BC, the First Emperor dispatched General Tu Sui with an army of 500,000 Qin soldiers to divide into five companies and attack the Hundred Yue tribes of the Lingnan region. The first company gathered at Yuhan (modern Yugan County in Jiangxi) and attacked the Minyue, defeating them and establishing the Minzhong Commandery. The second company fortified at Nanye (in modern Nankang, Jiangxi), and was designed to put defensive pressure on the southern clans. The third company occupied Panyu. The fourth company garrisoned near the Jiuyi Mountains, and the fifth company garrisoned outside Tancheng (in southwest Jingzhou Miao and Dong Autonomous County, Hunan). The First Emperor assigned official Shi Lu to oversee supply logistics. Shi first led a regiment of soldiers through the Lingqu Canal (which connected the Xiang River and the Li River), then navigated through the Yangtze and Pearl River water systems ensure the safety of the Qin supply routes. The Qin attack of the Western Valley (Chinese: 西甌) Yue tribe went smoothly, and Western Valley chieftain Yi-Xu-Song was killed. However, the Western Valley Yue were unwilling to submit to the Qin and fled into the jungle where they selected a new leader to continue resisting the Chinese armies. Later, a night-time counterattack by the Western Valley Yue devastated the Qin troops, and General Tu Sui was killed in the fighting. The Qin suffered heavy losses, and the imperial court selected General Zhao Tuo to assume command of the Chinese army. In 214 BC, the First Emperor dispatched Ren Xiao and Zhao Tuo at the head of reinforcements to once again mount an attack. This time, the Western Valley Yue were completely defeated, and the Lingnan region was brought entirely under Chinese control.[14][15][16] In the same year, the Qin court established the Nanhai, Guilin, and Xiang Commanderies, and Ren Xiao was made Lieutenant of Nanhai. Nanhai was further divided into Panyu, Longchuan, Boluo, and Jieyang counties (among several others), and Zhao Tuo was made magistrate of Longchuan.

Qin Shi Huang died in 210 BC, and his son Huhai became the Second Emperor of Qin. The following year, soldiers Chen Sheng, Wu Guang, and others seized the opportunity to revolt against the Qin government. Insurrections spread throughout much of China (including those led by Xiang Yu and Liu Bang, who would later face off over the founding of the next dynasty) and the entire Yellow River region devolved into chaos. Soon after the first insurrections, Nanhai Lieutenant Ren Xiao became gravely ill and summoned Zhao Tuo to hear his dying instructions. Ren described the natural advantages of the southern region and described how a kingdom could be founded with the many Chinese settlers in the area to combat the warring groups in the Chinese north.[17] He drafted a decree instating Zhao Tuo as the new Lieutenant of Nanhai, and died soon afterward.

After Ren's death, Zhao Tuo, sent orders to his troops in Hengpu Pass (north of modern Nanxiong, Guangdong), Yangshan Pass (northern Yangshan County), Huang Stream Pass (modern Yingde region, where the Lian River enters the Bei River), and other garrisons to fortify themselves against any northern troops. He also executed Qin officials still stationed in Nanhai and replaced them with his own trusted friends.[18]

Conquest of Âu Lạc

[edit]The kingdom of Âu Lạc, which was a merger of Nam Cương (Âu Việt) and Văn Lang (Lạc Việt),[19][20] lay south of Nanyue in the early years of Nanyue's existence, with Âu Lạc located primarily in the Red River delta area, and Nanyue encompassing Nanhai, Guilin, and Xiang Commanderies. During the time when Nanyue and Âu Lạc co-existed, Âu Lạc acknowledged Nanyue's suzerainty, especially because of their mutual anti-Han sentiment. Zhao Tuo also built up and reinforced his army, fearing an attack by the Han. However, when relations between the Han and Nanyue improved, in 179 BC Zhao Tuo marched southward and successfully annexed Âu Lạc.[21]

Proclamation (204 BC)

[edit]In 206 BC the Qin dynasty ceased to exist, and the Yue peoples of Guilin and Xiang were largely independent once more. In 204 BC, Zhao Tuo founded the Kingdom of Nanyue, with Panyu as capital, and declared himself the Martial King of Nanyue (Chinese: 南越武王, Vietnamese: Nam Việt Vũ Vương).

Nanyue under Zhao Tuo

[edit]After years of war with his rivals, Liu Bang established the Han dynasty and reunified Central China in 202 BC. The fighting had left many areas of China depopulated and impoverished, and feudal lords continued to rebel while the Xiongnu made frequent incursions into northern Chinese territory. The precarious state of the empire therefore forced the Han court to treat Nanyue initially with utmost circumspection. In 196 BC, Liu Bang, now Emperor Gaozu, sent Lu Jia (陸賈, not to be confused with Lü Jia 呂嘉) to Nanyue in hopes of obtaining Zhao Tuo's allegiance. After arriving, Lu met with Zhao Tuo and is said to have found him dressed in Yue clothing and being greeted after their customs, which enraged him. A long exchange ensued,[22] wherein Lu is said to have admonished Zhao Tuo, pointing out that he was Chinese, not Yue, and should have maintained the dress and decorum of the Chinese and not have forgotten the traditions of his ancestors. Lu lauded the strength of the Han court and warned against a kingdom as small as Nanyue daring to oppose it. He further threatened to kill Zhao's kinsmen in China proper and destroying their ancestral graveyards, as well as coercing the Yue into deposing Zhao himself. Following the threat, Zhao Tuo then decided to receive Emperor Gaozu's seal and submit to Han authority. Trade relations were established at the border between Nanyue and the Han kingdom of Changsha. Although formally a Han subject state, Nanyue seems to have retained a large measure of de facto autonomy.

After the death of Liu Bang in 195 BC, the government was put in the hands of his wife, Empress Lü Zhi, who served as Empress Dowager over their son Emperor Hui of Han and then Emperor Hui's sons Liu Gong and Liu Hong. Enraged, Empress Lü sent men to Zhao Tuo's hometown of Zhending (modern Zhengding County, Hebei) who killed much of Zhao's extended family and desecrated the ancestral graveyard there. Zhao Tuo believed that Wu Chen, the Prince of Changsha, had made false accusations against him to get Empress Dowager Lü to block the trade between the states and to prepare to conquer the Nanyue to merge into his principality of Changsha. In revenge, he then declared himself the emperor of Nanyue and attacked the principality of Changsha and captured some neighboring towns under Han domain. Lü sent general Zhou Zao to punish Zhao Tuo. However, in the hot and humid climate of the south, an epidemic broke out quickly amongst the soldiers, and the weakened army was unable to cross the mountains, forcing them to withdraw which ended in Nanyue victory, but the military conflict did not stop until the Empress died. Zhao Tuo then annexed the neighboring state of Minyue in the east as subject kingdom. The kingdom of Yelang and Tongshi (通什) also submitted to Nanyue rule.

In 179 BC, Liu Heng ascended the throne as Emperor of the Han. He reversed many of the previous policies of Empress Lü and took a conciliatory attitude toward Zhao Tuo and Nanyue. He ordered officials to revisit Zhending, garrison the town, and make offerings to Zhao Tuo's ancestors regularly. His prime minister Chen Ping suggested sending Lu Jia to Nanyue as they were familiar with each other. Lu arrived once more in Panyu and delivered a letter from the Emperor emphasizing that Empress Lü's policies were what had caused the hostility between Nanyue and the Han court and brought suffering to the border citizens. Zhao Tuo decided to submit to the Han once again, withdrawing his title of "emperor" and reverting to "king", and Nanyue became Han's subject state. However, most of the changes were superficial, and Zhao Tuo continued to be referred to as "emperor" throughout Nanyue.[24]

Zhao Mo

[edit]In 137 BC, Zhao Tuo died, having lived over one hundred years. Because of his great age, his son, the Crown Prince Zhao Shi, had preceded him in death, and therefore Zhao Tuo's grandson Zhao Mo became king of Nanyue. In 135 BC, the king of neighboring Minyue launched an attack on the towns along the two kingdoms' borders. Because Zhao Mo hadn't yet consolidated his rule, he was forced to implore Emperor Wu of Han to send troops to Nanyue's aid against what he called "the rebels of Minyue". The Emperor lauded Zhao Mo for his vassal loyalty and sent Wang Hui, an official governing ethnic minorities, and agricultural official Han Anguo at the head of an army with orders to separate and attack Minyue from two directions, one from Yuzhang Commandery, and the other from Kuaiji Commandery. Before they reached Minyue, however, the Minyue king was assassinated by his younger brother Yu Shan, who promptly surrendered.[25][26]

The Emperor sent court emissary Yan Zhu to the Nanyue capital to give an official report of Minyue's surrender to Zhao Mo, who had Yan return his gratitude to the Emperor along with a promise that Zhao would come visit the Imperial Court in Chang'an, and even sent his son Zhao Yingqi to return with Yan to the Chinese capital. Before the king could ever leave for Chang'an himself, one of his ministers strenuously advised against going for fear that Emperor Wu would find some pretext to prevent him from returning, thus leading to the destruction of Nanyue. King Zhao Mo thereupon feigned illness and never travelled to the Han capital.

Immediately following Minyue's surrender to the Han army, Wang Hui had dispatched a man named Tang Meng, local governor of Panyang County, to deliver the news to Zhao Mo. While in Nanyue, Tang Meng was introduced to the Yue custom of eating a sauce made from medlar fruit imported from Shu Commandery. Surprised that such a product was available, he learned that there was a route from Shu (modern Sichuan) to Yelang, and then along the Zangke River (now known as the Beipan River of Yunnan and Guizhou) which allowed direct access to the Nanyue capital Panyu. Tang Meng thereupon drafted a memorial to Emperor Wu suggesting a gathering of 100,000 elite soldiers at Yelang who would navigate the Zangke River and launch a surprise attack on Nanyue. Emperor Wu agreed with Tang's plan and promoted him to General of Langzhong and had him lead a thousand soldiers with a multitude of provisions and supply carts from Bafu Pass (near modern Hejiang County) into Yelang. Many of the carts carried ceremonial gifts which Yelang presented to the feudal lords of Yelang as bribes to declare allegiance to the Han dynasty, which they did, and Yelang became Qianwei Commandery of the Han Empire.[27]

Zhao Mo fell ill and died around 122 BC.

Zhao Yingqi

[edit]After hearing of his father's serious illness, Zhao Yingqi received permission from Emperor Wu to return to Nanyue. After Zhao Mo's death, Yingqi assumed the Nanyue throne. Before leaving for Chang'an he had married a young Yue woman and had his eldest son Zhao Jiande. While in Chang'an, he also married a Han Chinese woman, like himself, who was from Handan. Together they had a son Zhao Xing. After assuming the Nanyue kingship, he petitioned the emperor to appoint his Chinese wife (who was from the Jiu 樛 family) as Queen and Zhao Xing as Crown Prince, a move that eventually brought disaster upon Nanyue. Zhao Yingqi was reputed to be a tyrant who killed citizens with flippant abandon. He died of illness around 113 BC.

Zhao Xing and Zhao Jiande

[edit]

Zhao Xing succeeded his father as king, and his mother became Queen Dowager. In 113 BC, Emperor Wu of Han sent senior minister Anguo Shaoji to Nanyue summon Zhao Xing and his mother to Chang'an for an audience with the Emperor, as well as two other officials with soldiers to await a response at Guiyang. At the time, Zhao Xing was still young and the Queen Dowager was a recent immigrant to Nanyue, so final authority in matters of state rested in the hands of Prime Minister Lü Jia. Before the Queen Dowager married Zhao Yingqi, it was widely rumored that she had had an affair with Anguo Shaoji, and they were said to have renewed it when he was sent to Nanyue, which caused the Nanyue citizens to lose confidence in her rule.

Fearful of losing her position of authority, Queen Dowager Jiu persuaded Zhao Xing and his ministers to fully submit to Han dynasty rule, shifting Nanyue from an outer vassal state (外属诸侯国) to an inner vassal state (内属诸侯国) to Han dynasty.[28] At the same time, she dispatched a memorial to Emperor Wu requesting that they would join Han China, that they might have an audience with the Emperor every third year, and that the borders between Han China and Nanyue might be dissolved. The Emperor Wu granted her requests and sent Imperial seals to the Prime Minister and other senior officials, symbolizing that the Han court expected to directly control the appointments of senior officials. He also abolished the penal tattooing and nose-removal criminal punishments that were practiced among the Yue and instituted Han legal statutes. Emissaries that had been sent to Nanyue were instructed to remain there to ensure the stability of Han control. Upon receiving their Imperial decrees, King Zhao and the Queen Dowager began planning to leave for Chang'an.[29]

Prime Minister Lü Jia was much older than most officials and had served since the reign of Zhao Xing's grandfather Zhao Mo. His family was the preeminent Yue family in Nanyue and was thoroughly intermarried with the Zhao royal family. He vehemently opposed Nanyue's submission to the Han dynasty and criticized Zhao Xing on numerous occasions, though his outcries were ignored. Lü decided to begin planning a coup and feigned illness to avoid meeting the emissaries of the Han court. The emissaries were well aware of Lü's influence in the kingdom – it easily rivalled that of the king – but were never able to remove him. Sima Qian recorded a story that the Queen Dowager and the Zhao Xing invited Lü to a banquet with several Han emissaries where they hoped to find a chance to kill Lü: during the banquet, the Queen Dowager mentioned that Prime Minister Lü was against Nanyue submitting to the Han dynasty, with the hope that the Han emissaries would become enraged and kill Lü. However, Lü's younger brother had surrounded the palace with armed guards, and the Han emissaries, led by Anguo Shaoji, didn't dare attack Lü. Sensing the danger of the moment, Lü excused himself and stood to leave the palace. The Queen Dowager herself became furious and tried to grab a spear with which to kill the Prime Minister personally, but she was stopped by her son, the king. Lü Jia instructed his brother's armed men to surround his compound and stand guard and feigned illness, refusing to meet with King Zhao or any Han emissaries. At the same time, he began seriously plotting the upcoming coup with other officials.[30]

When news of the situation reached Emperor Wu, he dispatched a man named Han Qianqiu with 2,000 officials to Nanyue to wrest control from Lü Jia. In 112 BC, the men crossed into Nanyue territory, and Lü Jia finally executed his plan. He and those loyal to him appealed to the citizens that Zhao Xing was but a youth, Queen Dowager Jiu a foreigner who was plotting with the Han emissaries with the intent to turn the country over to Han China, giving over all of Nanyue's treasures to the Han Emperor and selling Yue citizens to the Imperial court as slaves with no thought for the welfare of the Yue people themselves. With the people's support, Lü Jia and his younger brother led a large group of men into the king's palace, killing Zhao Xing, Queen Dowager Jiu, and all the Han emissaries in the capital.

After the assassinations of Zhao Xing, the Queen Dowager, and the Han emissaries, Lü Jia ensured that Zhao Jiande, Zhao Yingqi's eldest son by his native Yue wife, took the throne, and quickly sent messengers to spread the news to the feudal rulers and officials of various areas of Nanyue.

War and the decline of Nanyue

[edit]

The 2,000 men led by Han Qianqiu began attacking towns along the Han-Nanyue border, and the Yue residents ceased resisting them, instead giving them supplies and safe passage. The group of men advanced quickly through Nanyue territory and were only 40 li from Panyu when they were ambushed by a regiment of Nanyue soldiers and completely annihilated. Lü Jia then took the imperial tokens of the Han emissaries and placed them in a ceremonial wooden box, then attached to it a fake letter of apology and installed it on the border of Han and Nanyue, along with military reinforcements. When Emperor Wu heard of the coup and Prime Minister Lü's actions, he became enraged. After issuing compensation to the families of the slain emissaries, he decreed the immediate mobilization of an army to attack Nanyue.

In autumn of 111 BC, Emperor Wu sent an army of 100,000 men divided into five companies to attack Nanyue. The first company was led by General Lu Bode and advanced from Guiyang (modern Lianzhou) down the Huang River (now called the Lian River). The second company was led by Commander Yang Pu and advanced from Yuzhang Commandery (modern Nanchang) through the Hengpu Pass and down the Zhen River. The third and fourth companies were led by Zheng Yan and Tian Jia, both Yue chieftains who had joined the Han dynasty. The third company left from Lingling (modern Yongzhou) and sailed down the Li River, while the fourth company went directly to garrison Cangwu (modern Wuzhou). The fifth company was led by He Yi and was composed mainly of prisoners from Shu and Ba with soldiers from Yelang; they sailed directly down the Zangke River (modern Beipan River). At the same time, Yu Shan, a king of Dong'ou, declared his intention to participate in the Han dynasty's attack on Nanyue and sent 8,000 men to support Yang Pu's company. However, upon reaching Jieyang, they pretended to have encountered severe winds that prevented them from advancing, and secretly sent details of the invasion to Nanyue.

By winter of that year, Yang Pu's company had attacked Xunxia and moved on to destroy the northern gates of Panyu (modern Guangzhou), capturing Nanyue's naval fleet and provisions. Seizing the opportunity, they continued south and defeated the first wave of Nanyue defenders before stopping to await the company led by Lu Bode. Lu's forces were mostly convicts freed in exchange for military service and made slow time, so at the planned rendezvous date with Yang Pu only a thousand of Lu's men had arrived. They went ahead with the attack anyway, and Yang's men led the advance into Panyu where Lü Jia and Zhao Jiande had fortified inside the inner walls. Yang Pu set up a camp southeast of the city and, as darkness fell, set the city on fire. Lu Bode encamped the northwest side of the city and sent soldiers up to the walls to encourage the Nanyue soldiers to surrender. As the night passed, more and more Panyu defenders defected to Lu Bode's camp out of desperation, so that as dawn arrived most of the Nanyue soldiers were gone. Lü Jia and Zhao Jiande realized Panyu was lost and fled the city by boat, heading west before the sun rose. Upon interrogating the surrendered soldiers, the Han generals learned of the two Nanyue leaders' escape and sent men after them. Zhao Jiande was caught first, and Lü Jia was captured in what is now northern Vietnam. Based on many temples of Lü Jia (Lữ Gia), his wives and soldiers scattering in Red River Delta of northern Vietnam, the war might last until 98 BC.[31][32]

After the fall of Panyu, Tây Vu Vương (the captain of Tây Vu area of which the center is Cổ Loa) revolted against the First Chinese domination from Western Han dynasty.[33] He was killed by his assistant Hoàng Đồng (黄同).[34][35]

Afterwards, the other commanderies and counties of Nanyue surrendered to the Han dynasty, ending Nanyue's 93-year existence as an autonomous and mostly sovereign kingdom. When news of Nanyue's defeat reached Emperor Wu, he was staying in Zuoyi County in Shanxi while travelling to perform imperial inspections, and promptly created the new county of Wenxi, meaning "Hearing of Glad News". After Lü Jia's capture he was executed by the Han soldiers and his head was sent to the emperor. Upon receiving it, he created Huojia County where he was travelling, meaning "Capturing [Lü] Jia".

Geography and demographics

[edit]Borders

[edit]

Nanyue originally comprised the Qin commanderies of Nanhai, Guilin, and Xiang. After 179 BC, Zhao Tuo persuaded Minyue, Yelang, Tongshi, and other areas to submit to Nanyue rule, but they were not strictly under Nanyue control. After the Western Han dynasty defeated Nanyue, its territory was divided into the seven commanderies of Nanhai, Cangwu, Yulin, Hepu, Jiaozhi, Jiuzhen, and Rinan. It was traditionally believed that the Qin conquest of the southern regions included the northern half of Vietnam, and that this area was also under Nanyue control. However, scholars have recently stated that the Qin likely never conquered territory in what is now Vietnam, and that Chinese domination there was first accomplished by the Nanyue themselves.[36]

Administrative Divisions

[edit]Zhao Tuo followed the Commandery-County system of the Qin dynasty when organizing the Kingdom of Nanyue. He left Nanhai Commandery and Guilin Commandery intact, then divided Xiang Commandery into the Jiaozhi and Jiuzhen Commanderies.[37] Nanhai comprised most of modern Guangdong, and was divided by the Qin into Panyu, Longchuan, Boluo, and Jieyang Counties, to which Zhao Tuo added Zhenyang and Hankuang.

Ethnicities

[edit]The majority of Nanyue's residents consisted of mainly Yue peoples. The Han Chinese population consisted of descendants of Qin armies sent to conquer the south, as well as girls who worked as army prostitutes, exiled Qin officials, exiled criminals, merchants and so on.

The Yue people were divided into numerous branches, tribes, and clans.

The Nanyue lived in north, east, and central Guangdong, as well as a small group in east Guangxi.

The Xi'ou lived in most of Guangxi and western Guangdong, with most of the population concentrated along the Xun River region and areas south of the Gui River, both part of the Xi River watershed. Descendants of Yi-Xu-Song, the chieftain killed resisting the Qin armies, acted as self-imposed governors of the Xi'ou clans. At the time of Nanyue's defeat by the Han dynasty, there were several hundred thousand Xi'ou people in Guilin Commandery alone.

The Luoyue clans lived in what is now western and southern Guangxi, northern Vietnam, the Leizhou Peninsula, Hainan, and southwest Guizhou. Populations were centered in the Zuo and You watersheds in Guangxi, the Red River Delta in northern Vietnam, and the Pan River watershed in Guizhou. The Chinese name "Luo", which denoted a white horse with a black mane, is said to have been applied to them after the Chinese saw their slash-and-burn method of hillside cultivation.

Government

[edit]Administrative system

[edit]

Because the Kingdom of Nanyue was established by Zhao Tuo, a Chinese general of the Qin dynasty, Nanyue's political and bureaucratic systems were, at first, essentially just continuations of those of the Qin Empire itself. Because of Zhao Tuo's submissions to the Han dynasty, Nanyue also adopted many of the changes enacted by the Han, as well. At the same time, Nanyue enjoyed complete autonomy – and de facto sovereignty – for most of its existence, so its rulers did enact several systems that were entirely unique to Nanyue.[38]

Nanyue was a monarchy, and its head of state generally held the title of "king" (Chinese: 王), though its first two rulers Zhao Tuo and Zhao Mo were referred to as "Emperor" within Nanyue's borders. The kingdom had its own Calendar era system based (like China's) on Emperors' reign periods. Succession in the monarchy was based on hereditary rule, with the King or Emperor's successor designated as crown prince. The ruler's mother was designated empress dowager, his wife as empress or queen, and his concubines as "Madam" (Chinese: 夫人). The formalities extended to the ruler's family were on the level of that of the Han dynasty Emperor, rather than that of a feudal king.[39]

Although Nanyue continued the Commandery-County system of the Qin dynasty, its leaders later enfeoffed their own feudal princes and lords – a mark of its sovereignty – in a manner similar to that of the Western Han. Imperial documents from Nanyue record that princes were enfeoffed at Cangwu, Xixu, as well as local lords at Gaochang and elsewhere. Zhao Guang, a relative of Zhao Tuo, was made King of Cangwu, and his holdings were what is now Wuzhou in the Guangxi Zhuang Autonomous Region. In what is considered a manifestation of Zhao Tuo's respect for the Hundred Yue, he enfeoffed a Yue chieftain as King of Xixu in order to allow the Yue of that area to enjoy autonomy under a ruler of their own ethnicity. The chieftain's name is unknown, but he was a descendant of Yi-Xu-Song, the chieftain killed while fighting the original Chinese invasion under the Qin dynasty.[40]

Nanyue's bureaucracy was, like the famed bureaucracy of the Qin dynasty, divided into central and regional governments. The central government comprised a prime minister who held military and administrative authority, inner scribes who served under the prime minister, overseeing Censors of various rank and position, commanders of the Imperial Guard, senior officials who carried out the King's official administration, as well as all military officers and officials of the Food, Music, Transportation, Agriculture, and other bureaus.[41]

Nanyue enacted several other policies that reflected Chinese dominance, such as the household registration system (an early form of census), as well as the promulgation of the use of Chinese characters among the Hundred Yue population and the use of Chinese weights and measures.[42]

Military

[edit]

Nanyue's army was largely composed of the several hundred thousand (up to 500,000) Qin Chinese troops that invaded during the Qin dynasty and their descendants. After the kingdom's founding in 204 BC, some Yue citizens also joined the army. Nanyue's military officers were known as General, General of the Left, Xiao ("Colonel"), Wei ("Captain"), etc., essentially identical to the Chinese system. The army had infantry, naval troops, and cavalry.[43]

Ethnic policy

[edit]The Kingdom continued most of the Qin Commanderies' policies and practices dealing with the interactions between the local Yue and the Han immigrants, and Zhao Tuo proactively promoted a policy of assimilating the two cultures into each other. Although the Han were certainly dominant in holding leadership positions, the overwhelming disparity was largest immediately after the Qin conquest. Over time, the Yue gradually began holding more positions of authority in the government. Lü Jia, the last prime minister of the Kingdom, was a Yue citizen, and over 70 of his kinsmen served as officials in various parts of the government. In areas of particular "complexity", as they were called, Yue chieftains were often enfeoffed with great autonomy, such as in Xixu. Under the impetus of Zhao Tuo's leadership, Chinese immigrants were encouraged to adopt the customs of the Yue. Marriages between the Han Chinese and Yue became increasingly common throughout Nanyue's existence, and even occurred in the Zhao royal family. Many marriages between the Zhao royal family (who were Han Chinese) and the Lü family (Yue – they likely adopted Chinese names early in Nanyue's history) were recorded. Zhao Jiande, Nanyue's last king, was the son of previous king Zhao Yingqi and his Yue wife. Despite the dominating influence of the Chinese newcomers on the Hundred Yue, the amount of assimilation gradually increased over time.[44]

Language

[edit]Other than Old Chinese, which was used by Han settlers and government officials, native Nanyue people likely spoke Ancient Yue, a now extinct language. Some scholars suggest that they spoke a language related to the modern Zhuang language. Some suggest that the descendants spoke Austroasiatic languages instead.[45] It is plausible to say that the Yue spoke more than one language. Old Chinese in the region was likely much influenced by Yue speech (and vice versa), and many loanwords in Chinese have been identified by modern scholars.[46]

Diplomacy

[edit]With the Western Han

[edit]Beginning with its first allegiance to the Han dynasty in 196 BC, Nanyue alternately went through two periods of allegiance to and then opposition with the Han dynasty that continued until Nanyue's destruction at the hands of the Han dynasty in early 111 BC.

The first period of Nanyue's subordination to the Han dynasty began in 196 BC when Zhao Tuo met Lü Jia, an emissary from Emperor Gaozu of Han, and received from him a Han imperial seal enthroning Zhao Tuo as King of Nanyue. This period lasted thirteen years until 183 BC, during which time significant trade took place. Nanyue paid tribute in rarities from the south, and the Han court bestowed gifts of iron tools, horses, and cattle upon Nanyue. At the same time, the countries' borders were always heavily guarded.[47]

Nanyue's first period of antagonism with the Han dynasty lasted from 183 BC to 179 BC, when trade was suspended and Zhao Tuo severed relations with the Han. During this period, Zhao Tuo openly referred to himself as Emperor and launched an attack against the Changsha Kingdom, a feudal state of the Han dynasty, and Han troops were sent to engage Nanyue. Nanyue's armies successfully halted the southern progress of the advance, winning the respect and then allegiance of the neighboring kingdoms of Minyue and Yelang.[48]

Nanyue's second period of submission to the Han dynasty lasted from 179 BC to 112 BC. This period began with Zhao Tuo abandoning his title of "Emperor" and declaring allegiance to the Han Empire, but the submission is mostly superficial as Zhao Tuo was referred to as emperor throughout Nanyue and the kingdom retained its autonomy. Zhao Tuo's four successors did not display the strength he had, and Nanyue dependence on Han China slowly grew, characterized by second king Zhao Mo calling upon Emperor Wu of Han to defend Nanyue from Minyue.

Nanyue's final period of antagonism with Han China was the war that proved Nanyue's destruction as a kingdom. At the time of Prime Minister Lü Jia's rebellion, Han China was enjoying a period of growth, economic prosperity, and military success, having consistently defeated the Xiongnu tribes along China's northern and northwestern borders. The weakened state of Nanyue and the strength of China at the time allowed Emperor Wu to unleash a devastating attack on Nanyue, as described above.

With Changsha

[edit]

The Changsha Kingdom was, at the time, a feudal kingdom that was part of Han dynasty. Its territory comprised most of modern Hunan Province and part of Jiangxi Province. When Emperor Gaozu of Han enfeoffed Wu Rui as the first King of Changsha, he also gave him the power to govern Nanhai, Xiang, and Guiling Commanderies, which caused strife between Changsha and Nanyue from the start. The Han China-Nanyue border was essentially that of Changsha, and therefore was constantly fortified on both sides. In terms of policies, because the Kingdom of Changsha had no sovereignty whatsoever, any policy of the Han court toward Nanyue was by default also Changsha's policy.

With Minyue

[edit]Minyue was located northeast of Nanyue along China's southeast coast, and comprised much of modern Fujian Province. The Minyue were defeated by the armies of the Qin dynasty in the 3rd century BC and the area was organized under Qin control as the Minzhong Commandery, and Minyue ruler Wuzhu was deposed. Because of Wuzhu's support for Liu Bang after the collapse of the Qin dynasty and the founding of the Han, he was reinstated by the Han court as King of Minyue in 202 BC.

The relations between Nanyue and Minyue can be classified into three stages: the first, from 196 BC to 183 BC, was during Zhao Tuo's first submission to the Han dynasty, and the two kingdoms were on relatively equal footing. The second stage was from 183 BC to 135 BC, when Minyue submitted to Nanyue after seeing it defeat the Han dynasty's first attack on Nanyue. The third stage began in 135 BC when King Wang Ying attacked a weakened Nanyue, forcing Zhao Mo to seek aid from Han China. Minyue once again submitted to the Han dynasty, making itself and Nanyue equals once more.

With the Yi tribes

[edit]The southwestern Yi people lived west of Nanyue, and shared borders with Nanyue in Yelang, Wulian, Juding, and other regions. Yelang was the largest state of the Yi people, comprising most of modern Guizhou and Yunnan Provinces, as well as the southern part of Sichuan Province. Some believe the ancient Yi to have been related to the Hundred Yue, with this explaining the close relationship between Yelang and Nanyue. After Nanyue first repelled the Han, nearly all of the Yi tribes declared allegiance to Nanyue, and most of them retained that allegiance until Nanyue's demise in 111 BC. During Emperor Wu of Han's final attack on Nanyue, most of the Yi tribes refused to assist in the invasion. One chieftain called Qie-Lan went so far as to openly oppose the move, later killing the emissary sent by the Han to his territory as well as the provincial governor installed in the Qianwei Commandery.

Monarchs

[edit]| Personal Name | Reign Period | Reigned From | Other Names | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Name | Cantonese | Standard Mandarin | Zhuang | Vietnamese | Name | Cantonese | Standard Mandarin | Vietnamese | ||

| 趙佗 | ziu6 to4 | Zhào Tuó | Ciuq Doz | Triệu Đà | 武王 | mou5 wong4 | Wǔ Wáng | Vũ Vương | 203–137 BC | |

| 趙眜 | ziu6 mut6 | Zhào Mò | Ciuq Huz | Triệu Mạt | 文王 | man4 wong4 | Wén Wáng | Văn Vương | 137–122 BC | 趙胡 |

| 趙嬰齊 | ziu6 jing1 cai4 | Zhào Yīngqí | Ciuq Yinghcaez | Triệu Anh Tề | 明王 | ming4 wong4 | Míng Wáng | Minh Vương | 122–113 BC | |

| 趙興 | ziu6 hing1 | Zhào Xīng | Ciuq Hingh | Triệu Hưng | 哀王 | oi1 wong4 | Āi Wáng | Ai Vương | 113–112 BC | |

| 趙建德 | ziu6 gin3 dak1 | Zhào Jiàndé | Ciuq Gendwz | Triệu Kiến Đức | 陽王 | joeng4 wong4 | Yáng Wáng | Dương Vương | 112–111 BC | |

Archaeological findings

[edit]

The Nanyue Kingdom Palace Ruins, located in the city of Guangzhou, covers 15,000 square metres. Excavated in 1995, it contains the remains of the ancient Nanyue palace. In 1996, it was listed as protected National Cultural Property by the Chinese government. Crescent-shaped ponds, Chinese gardens and other Qin architecture were discovered in the excavation.

In 1983, the ancient tomb of the Nanyue King Wáng Mù (王墓) was discovered in Guangzhou, Guangdong. It was later identified as the tomb of Zhào Mò, the second ruler of Nanyue. The tomb was never disturbed by tomb robbers prior to this discovery, leaving most of the artifacts intact. In 1988, the Nanyue King Museum was constructed on this site, to display more than 1,000 excavated artefacts including 500 pieces of Chinese bronzes, 240 pieces of Chinese jade and 246 pieces of metal, all of which provide invaluable information about Nanyue. In 1996, the Chinese government listed this site as a national priority protected site.

A bronze seal inscribed "Tư Phố hầu ấn" (胥浦侯印, Seal for Captain of Tu Pho County) was uncovered at Thanh Hoa in northern Vietnam during the 1930s.[49] Owing to the similarity to seals found at the tomb of the second king of Nam Viet, this bronze seal is recognized as an official seal of the Nam Viet Kingdom. There were artifacts that were found in which belonged to the Dong Son culture of northern Vietnam. The goods were found buried alongside the tomb of the second king of Nam Viet.

Status in Vietnamese historiography

[edit]In Vietnam, the rulers of Nanyue are referred to as the Triệu dynasty, the Vietnamese pronunciation of the surname Chinese: 趙; pinyin: Zhào. While traditional Vietnamese historiography considered the Triệu dynasty to be an orthodox regime, modern Vietnamese scholars generally regard it as a foreign regime that ruled Vietnam. The oldest text compiled by a Vietnamese court, the 13th century Đại Việt sử ký, considered Nanyue to be the official starting point of their history. According to the Đại Việt sử ký, Zhao Tuo established the foundation of Đại Việt. However, later historians in the 18th century started questioning this view. Ngô Thì Sĩ (1726–1780) argued that Zhao Tuo was a foreign invader based in Panyu (Guangzhou) who ruled the Hong River Delta indirectly, and Nanyue was a foreign dynasty like the Southern Han that should not be included in Vietnamese history. This view became the mainstream among Vietnamese historians in North Vietnam and later became the state orthodoxy after reunification. Nanyue was removed from the national history while Zhao Tuo was recast as a foreign invader.[50][51]

The name "Vietnam" is derived from Nam Việt (Southern Việt), the Vietnamese pronunciation of Nanyue.[11] However, it has also suggested that the name "Vietnam" was derived from a combination of Quảng Nam Quốc (the domain of the Nguyen lords, from whom the Nguyễn dynasty descended) and Đại Việt (which the first emperor of the Nguyễn dynasty, Gia Long, conquered).[52] Qing emperor Jiaqing refused Gia Long's request to change his country's name to Nam Việt, and changed the name instead to Việt Nam.[53] Đại Nam thực lục contains the diplomatic correspondence over the naming.[54]

Culture

[edit]There was a fusion of Han and Nanyue cultures in significant ways, as shown by the artifacts unearthed by archaeologists from the tomb of King Zhao Mo in Guangzhou. The Nanyue tomb in Guangzhou is extremely rich. There are quite a number of bronzes that show cultural influences from the Han, Chu, Yue and Ordos regions.[55]

Gallery

[edit]-

Gold seal

-

Jade Drinking Vessel in Rhino Horn Shape

-

Jade Openwork Disk with Dragon and Phoenix

-

Jade Drinking Cup for Collecting Sweet Dew

-

Jade Covered Box

-

Bronze screen parts

-

Bronze screen parts

-

Bronze screen parts

-

Bronze Tripod Ding

-

Bronze Beaker Mounted with Jade Plaques

-

Bronze wine vessel

-

Bronze disk

-

Brozen Canister with lacquer drawing

-

Nanyue Sluice Model

-

Mausoleum of King Triệu Mạt (Zhao Mo)

-

Đông Sơn bronze jar

-

Bronze mortar and pestle

-

Bronze mirror inlaid with silver

-

Game of Liubo

-

Game of Liubo

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ 司马迁 (1959). 史記·南越列传(卷113). 北京: 中华书局. pp. 2967–2977.

- ^ 班固 (1962). 漢書·西南夷两粤朝鲜传(卷95). 北京: 中华书局. pp. 3837–3863.

- ^ "Site of Southern Yue State". United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization. Retrieved 26 August 2019.

- ^ Wicks, Robert (2018). Money, Markets, and Trade in Early Southeast Asia: The Development of Indigenous Monetary Systems to AD 1400. Cornell University Press. p. 27. ISBN 9781501719479.

- ^ a b Walker, Hugh (2012). East Asia: A New History. AuthorHouse. p. 107. ISBN 9781477265178.

- ^ a b c Yang, Wanxiu; Zhong, Zhuo'an (1996). 廣州簡史. 广东人民出版社. p. 24. ISBN 9787218020853.

- ^ a b c 南越国史迹研讨会论文选集. 文物出版社. 2005. p. 225. ISBN 9787501017348.

- ^ Xie, Xuanjun (2017). 中国的本体、现象、分裂、外延、外扩、回想、前瞻、整合. Lulu.com. p. 57. ISBN 9781365677250.

- ^ Zhang Rongfang, Huang Miaozhang, Nan Yue Guo Shi, 2nd ed., pp. 418–422

- ^ Shelton Woods, L. (2002). Vietnam: a global studies handbook. ABC-CLIO. p. 38. ISBN 1576074161.

- ^ a b Ooi, Keat Gin (2004). Southeast Asia: A Historical Encyclopedia. ABC-CLIO. pp. 932–934. ISBN 1-57607-770-5.

- ^ Sima Qian – Records of the Grand Historian, section 113 《史記·南越列傳》

- ^ Amies, Alex; Ban, Gu (2020). Hanshu Volume 95 The Southwest Peoples, Two Yues, and Chaoxian: Translation with Commentary. Gutenberg Self Publishing Press. pp. 26–42. ISBN 978-0-9833348-7-3.

- ^ Sima Qian, Records of the Grand Historian, section 112.

- ^ Huai Nan Zi, section 18

- ^ Zhang & Huang, pp. 26–31.

- ^ Taylor (1983), p. 23

- ^ Hu Shouwei, Nan Yue Kai Tuo Xian Qu – Zhao Tuo, pp. 35–36.

- ^ Hoàng 2007, p. 12.

- ^ Dutton, Werner & Whitmore 2012, p. 9.

- ^ Taylor, Keith Weller (1991). Birth of Vietnam, The. University of California Press. pp. 23–27. ISBN 0520074173.

- ^ Records of the Grand Historian, section 97 《史記·酈生陸賈列傳》

- ^ Hansen, Valerie (2000). The Open Empire: A History of China to 1600. New York: W. W. Norton. p. 125. ISBN 0-393-97374-3.

- ^ Zhang and Huang, pp. 196-200; also Shi Ji 130

- ^ Records of the Grand Historian, section 114.

- ^ Hu Shouwei, Nan Yue Kai Tuo Xian Qu --- Zhao Tuo, pp. 76–77.

- ^ Records of the Grand Historian, section 116.

- ^ "丝绸之路多媒体系列资源库". www.sxlib.org.cn. Retrieved 11 September 2024.

- ^ Zhang & Huang, pp. 401–402

- ^ Records of the Grand Historian, section 113.

- ^ "Lễ hội chọi trâu xã Hải Lựu (16–17 tháng Giêng hằng năm) Phần I (tiep theo)". 3 February 2010.

Theo nhiều thư tịch cổ và các công trình nghiên cứu, sưu tầm của nhiều nhà khoa học nổi tiếng trong nước, cùng với sự truyền lại của nhân dân từ đời này sang đời khác, của các cụ cao tuổi ở Bạch Lưu, Hải Lựu và các xã lân cận thì vào cuối thế kỷ thứ II trước công nguyên, nhà Hán tấn công nước Nam Việt của Triệu Đề, triều đình nhà Triệu tan rã lúc bấy giờ thừa tướng Lữ Gia, một tướng tài của triều đình đã rút khỏi kinh đô Phiên Ngung (thuộc Quảng Đông – Trung Quốc ngày nay). Về đóng ở núi Long Động – Lập Thạch, chống lại quân Hán do Lộ Bác Đức chỉ huy hơn 10 năm (từ 111- 98 TCN), suốt thời gian đó Ông cùng các thổ hào và nhân dân đánh theo quân nhà Hán thất điên bát đảo."

- ^ "List of temples related to Triệu dynasty and Nam Việt kingdom in modern Vietnam and China". 28 January 2014.

- ^ Từ điển bách khoa quân sự Việt Nam, 2004, p564 "KHỞI NGHĨA TÂY VU VƯƠNG (lll TCN), khởi nghĩa của người Việt ở Giao Chỉ chống ách đô hộ của nhà Triệu (TQ). Khoảng cuối lll TCN, nhân lúc nhà Triệu suy yếu, bị nhà Tây Hán (TQ) thôn tính, một thủ lĩnh người Việt (gọi là Tây Vu Vương, "

- ^ Viet Nam Social Sciences vol.1-6, p91, 2003 "In 111 B.C. there prevailed a historical personage of the name of Tay Vu Vuong who took advantage of troubles circumstances in the early period of Chinese domination to raise his power, and finally was killed by his general assistant, Hoang Dong. Professor Tran Quoc Vuong saw in him the Tay Vu chief having in hands tens of thousands of households, governing thousands miles of land and establishing his center in Co Loa area (59.239). Tay Vu and Tay Au is in fact the same.

- ^ Book of Han, Vol. 95, Story of Xi Nan Yi Liang Yue Zhao Xian, wrote: "故甌駱將左黃同斬西于王,封爲下鄜侯"

- ^ Zhang & Huang, pp. 83–84.

- ^ Zhang & Huang, p. 114.

- ^ Zhang & Huang, pp. 112–113.

- ^ Yu Tianchi, Qin Shengmin, Lan Riyong, Liang Xuda, Qin Cailuan, Gu Nan Yue Guo Shi, pp. 60–63.

- ^ Zhang & Huang, pp. 113–121

- ^ Zhang & Huang, pp. 134–152

- ^ Zhang & Huang, pp. 121–126, 133–134.

- ^ Zhang & Huang, pp. 127–131

- ^ Zhang & Huang, pp. 170–174

- ^ Loewe, Michael; Shaughnessy, Edward L. (13 March 1999). The Cambridge History of Ancient China: From the Origins of Civilization to 221 BC. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521470308.

- ^ Zhang & Huang, 320-321.

- ^ Zhang & Huang, pp. 189-191.

- ^ Liu Min, "Ultimate Conclusions on 'Kai Guan' – A View of Han-Nanyue Relations From the Wen Di Seal Chinese: '开棺' 定论 – 从文帝行玺看汉越关系), in Nanyue Guo Shiji Yantaohui Lunwen Xuanji 南越国史迹研讨会论文选集, pp. 26-27.

- ^ "Thạp đồng Đông Sơn của Huyện lệnh Long Xoang (Xuyên) Triệu Đà". 11 March 2011. Archived from the original on 25 September 2015.

Chiếc ấn đồng khối vuông "Tư (Việt) phố hầu ấn" có đúc hình rùa trên lưng được thương nhân cũng là nhà sưu tầm người Bỉ tên là Clement Huet mua được ở Thanh Hóa hồi trước thế chiến II (hiện bày ở Bảo tàng Nghệ thuật và Lịch sử Hoàng Gia Bỉ, Brussel) được cho là của viên điển sứ tước hầu ở Cửu Chân. Tư Phố là tên quận trị đóng ở khu vực làng Ràng (Thiệu Dương, Thanh Hóa) hiện nay.

- ^ Yoshikai Masato, "Ancient Nam Viet in historical descriptions", Southeast Asia: a historical encyclopedia, from Angkor Wat to East Timor, Volume 2, ABC-CLIO, 2004, p. 934.

- ^ Ngô, Thì Sĩ. "Ngoại Kỷ Quyển II". Đại Việt sử ký tiền biên.

- ^ See, e.g., Bo Yang, Outlines of the History of the Chinese (中國人史綱), vol. 2, pp. 880-881.

- ^ Alexander Woodside (1971). Vietnam and the Chinese Model: A Comparative Study of Vietnamese and Chinese Government in the First Half of the Nineteenth Century. Harvard Univ Asia Center. pp. 120–. ISBN 978-0-674-93721-5.

- ^ Jeff Kyong-McClain; Yongtao Du (2013). Chinese History in Geographical Perspective. Rowman & Littlefield. pp. 67–. ISBN 978-0-7391-7230-8.

- ^ Guangzhou Xi Han Nanyue wang mu bo wu guan, Peter Y. K. Lam, Chinese University of Hong Kong. Art Gallery – 1991 – 303 pages – Snippet view [1]

Further reading

[edit]- Taylor, Keith Weller. (1983). The Birth of Vietnam (illustrated, reprint ed.). University of California Press. ISBN 0520074173. Retrieved 7 August 2013.

- Records of the Grand Historian, vol. 113.

- Book of Han, vol. 95.

- Zizhi Tongjian, vols. 12, 13, 17, 18, 20.

External links

[edit]Nanyue

View on GrokipediaHistory

Qin Expansion and Establishment (218–204 BC)

In 214 BC, Qin Shi Huang mobilized approximately 500,000 troops, including conscripted laborers and merchants, to conquer the Baiyue territories in Lingnan (modern Guangdong, Guangxi, and northern Vietnam), dispatching generals Ren Xiao and Zhao Tuo to lead the campaigns.[4][5] These expeditions subdued numerous Yue tribes through direct military assaults and established three commanderies—Nanhai (centered at Panyu, modern Guangzhou), Guilin, and Xiang—to administer the region and facilitate resource extraction.[4][6] To enable army supply lines across rugged terrain, Qin engineers under overseer Shi Lu constructed the Lingqu canal, linking the Xiang River basin to the Li River and enabling water transport for provisions and troops southward.[5] Additional road networks were built from the central Yangtze regions to Cangwu and other frontier points, supporting sustained occupation amid malaria-prone lowlands and guerrilla resistance from Yue forces.[7] The primary drivers were pragmatic: securing tribute of pearls from coastal fisheries, metals like copper and tin from inland mines, and exotic goods such as ivory and rhinoceros horns, rather than cultural assimilation or ideological unification.[8] Following the Qin dynasty's collapse in 207 BC amid widespread rebellions, Zhao Tuo—initially appointed as a Qin military commander and later viceroy of Nanhai commandery—consolidated control over the southern territories as central authority disintegrated.[6] In 204 BC, exploiting the power vacuum and local instability, Zhao Tuo proclaimed himself Martial King of Nanyue (South Yue), formally establishing the kingdom with Panyu as its capital and incorporating former Qin commanderies into a semi-independent polity blending Qin administrative practices with Yue customs.[8][6] This breakaway move capitalized on the remoteness of Lingnan from northern warlords, ensuring de facto autonomy amid the Chu-Han Contention.[9]Zhao Tuo's Consolidation and Independence (204–137 BC)

Following the collapse of the Qin dynasty, Zhao Tuo proclaimed himself King of Nanyue in 204 BC, establishing Panyu as the capital and consolidating control over the region through military campaigns that subdued local chieftains and ensured internal stability.[6] He centralized authority by adapting Qin administrative structures, such as commandery systems, while incorporating indigenous Yue customs to govern a diverse population effectively.[6] This hybrid model facilitated pragmatic rule, prioritizing territorial integrity over strict Sinicization.[6] Economic imperatives underpinned Zhao Tuo's independence, as Nanyue's command of southern trade routes—yielding resources like pearls, ivory, and rhinoceros hides—provided leverage against northern powers reliant on such imports.[10] When Han Empress Lü imposed a trade ban on iron and horses circa 184 BC to coerce submission, Zhao retaliated by proclaiming himself Emperor Wu of Nanyue in 183 BC, adopting imperial regalia and launching incursions into the Han-aligned kingdom of Changsha to seize border territories.[11] This escalation asserted sovereignty without provoking all-out conflict, exploiting the Han court's internal divisions.[11] Han military probes followed in 181 BC and 180 BC, but Nanyue forces repelled them, hampered by the region's harsh climate, diseases, and terrain unfamiliar to northern troops.[6] After Lü's death in 180 BC, Emperor Wen dispatched envoy Lu Jia, who persuaded Zhao Tuo to renounce the imperial title and accept nominal Han vassalage in exchange for resuming trade and autonomy.[6] This diplomatic maneuver, leveraging Han regency instability, preserved Nanyue's de facto independence until Zhao's death in 137 BC, demonstrating calculated restraint amid power asymmetries.[6]Rule of Successors and Internal Instability (137–113 BC)

Upon the death of Zhao Tuo in 137 BC, his grandson Zhao Mo ascended the throne of Nanyue, ruling until 122 BC. Unlike his grandfather, who had proclaimed himself emperor and maintained fierce independence, Zhao Mo adopted a conciliatory stance toward the Han dynasty, submitting as a marquis to avert conflict and secure tributary relations. This shift reflected the successors' reduced military autonomy, as Nanyue's forces, primarily composed of Yue tribal levies, proved inadequate against organized threats without external aid. In 135 BC, when the kingdom of Minyue invaded, Zhao Mo appealed to Emperor Wu of Han for intervention, prompting Han forces to defeat Minyue and install a puppet ruler, thereby deepening Nanyue's dependence on Han protection.[12][13] Zhao Mo's son, Zhao Yingqi, succeeded him in 122 BC and reigned until approximately 115 BC, further entrenching pro-Han orientations through personal ties. Having been sent to the Han capital Chang'an as a youth to serve as an attendant-hostage, Yingqi forged alliances, including marriage to a Han Chinese woman from the Jiu clan of Handan, whose influence grew posthumously as queen dowager. These connections symbolized the Sinicization of the ruling elite, prioritizing Han cultural and political norms over local Yue traditions, which alienated native aristocrats favoring autonomy. Brief stability under Yingqi masked underlying factionalism, as the court's growing reliance on Han diplomatic and military support eroded Nanyue's sovereign capacity.[8][11] Internal divisions culminated under Yingqi's young son Zhao Xing, who briefly ruled from 115 BC. The pro-Han queen dowager Jiu advocated incorporating Nanyue as a Han prefecture, prompting vehement opposition from Prime Minister Lü Jia, a key figure representing indigenous interests. In 113 BC, Lü Jia orchestrated a coup, executing Zhao Xing and the queen dowager to preserve independence, but this act exposed the kingdom's fractures between Sinicized rulers and local elites protective of Yue customs and self-rule. Nanyue's military, still dependent on loosely organized Yue warriors rather than a centralized standing army, lacked the cohesion to withstand ensuing pressures, highlighting the successors' failure to consolidate power akin to Zhao Tuo's era.[12][11]Han Conquest and Dissolution (113–111 BC)

In 113 BC, Prime Minister Lü Jia of Nanyue staged a coup, assassinating the pro-Han king Zhao Xing, his mother the Queen Dowager Jiu, and Han emissaries, while installing the anti-Han Zhao Jiande as puppet ruler.[14] This act of defiance prompted Emperor Wu of Han to declare war, exploiting the internal instability to justify invasion.[15] Han forces initially dispatched under Han Qianqiu were repelled, but the coup fragmented Nanyue's leadership, weakening coordinated defense.[14] The Han campaign escalated in 112–111 BC with a coordinated multi-pronged assault involving over 100,000 troops, including naval fleets from the east under Yang Pu and land armies converging from the north, west, and south.[16] Superior Han logistics, drawn from the empire's vast resources, overwhelmed Nanyue's defenses despite the kingdom's reliance on riverine terrain and tribal levies.[13] By late 111 BC, Han general He Bo captured Panyu after encircling the capital, where resisting forces, led by Lü Jia, suffered heavy casualties; Zhao Jiande fled but was soon apprehended and executed.[17] Many Yue chieftains surrendered, highlighting the fragility of Nanyue's loose confederation of Han elites and indigenous groups. Post-conquest, the Han dissolved Nanyue's monarchy and reorganized its territories into nine commanderies—Nanhai, Cangwu, Yulin, Hepu, Jiaozhi, Jiuzhen, Dayuan, Zhuya, and Dan'er—to integrate the region administratively.[17] This fragmentation underscored causal vulnerabilities: Nanyue's geographic isolation and dependence on unreliable tribal alliances precluded effective mobilization against the Han's unified imperial apparatus, which leveraged centralized taxation and conscription for sustained operations.[13] Resistance pockets were quelled by 110 BC, marking the end of Nanyue's autonomy after 93 years.[18] Primary accounts from Sima Qian's Shiji, while glorifying Han achievements, align with archaeological evidence of widespread disruption, including deforestation for siege engines near Panyu.[16]Geography and Demographics

Territorial Boundaries

The Kingdom of Nanyue occupied the Lingnan region south of the Nanling Mountains, known as the Five Ridges, which formed a formidable natural barrier and northern defensive boundary against incursions from the Han dynasty's Yangtze River territories.[1][19] This subtropical frontier extended from the Pearl River Delta westward across modern Guangdong and Guangxi provinces, incorporating the former Qin commanderies of Nanhai, Guilin, and Xiang, with Panyu—contemporary Guangzhou—serving as the political and economic hub.[20] Archaeological evidence, including palace ruins spanning approximately 400,000 square meters in Guangzhou's Yuexiu district and over 1,000 bronze and iron artifacts, corroborates the kingdom's centralized control in this core area.[21][22] Under Zhao Tuo's expansion, Nanyue incorporated the kingdom of Âu Lạc through conquest around 179 BC, thereby extending its southern reach to the Red River Delta in present-day northern Vietnam, merging these territories with the Chinese southern commanderies.[23] This addition linked Yue cultural elements with Qin-Han administrative frameworks, projecting northern Chinese influence into Southeast Asian lowlands. Han historical records, such as those detailing Zhao Tuo's campaigns, and archaeological sites like the Nanyue King's tomb with its inscribed stelae, verify this extent, highlighting integration rather than isolation.[20] Eastern boundaries fluctuated with the Minyue kingdom, involving intermittent alliances and conflicts, while western limits abutted non-Han tribal regions like Yelang, constrained by rugged terrain.[24] Maritime access via ports such as Panyu enabled oversight of coastal and island peripheries, including potential extensions toward Hainan, underscoring Nanyue's strategic position as a bridge between continental interiors and sea routes, as evidenced by Han-era silk maps and military artifacts.[25]Administrative Organization

The Kingdom of Nanyue organized its territory using a hierarchical system of commanderies (jùn) subdivided into counties (xiàn), directly emulating the Qin dynasty's bureaucratic model to impose centralized control over expansive and varied landscapes from the Pearl River Delta to northern Vietnam. The capital, Panyu (modern Guangzhou), located in the core Nanhai Commandery, functioned as the political and administrative center, housing the royal palace and coordinating governance across the realm.[1][12] At its foundation in 204 BC, Nanyue inherited the three primary Qin commanderies of Nanhai, Guilin, and Xiang, which provided the initial framework for revenue collection, legal enforcement, and military deployment. Subsequent expansions under Zhao Tuo and his successors, including alliances with Minyue after 179 BC, incorporated additional commanderies and counties, enabling systematic oversight of tribute and labor obligations in peripheral areas.[26][13] Local administration blended Qin-Han standardization with pragmatic accommodation of indigenous structures; Zhao Tuo appointed Yue chieftains as subordinate officials, preserving their customary authority in rural counties while subordinating them to commandery-level Han-style prefects, which minimized resistance and facilitated tax extraction from tribal lands.[13][8] Administrative efficacy relied on Qin-era infrastructure, such as engineered mountain roads and the Lingqu Canal linking the Yangtze and Pearl River basins, which supported troop movements, grain transport, and annual tribute relays to the capital, as chronicled in Han dynastic annals detailing Nanyue's submissions.[12][27]Ethnic Composition and Population Dynamics

The ethnic composition of Nanyue reflected a stratified society where indigenous Baiyue (Yue) tribes constituted the overwhelming majority of the population, inhabiting rural areas and coastal regions from the Yangtze Delta southward into modern Guangdong, Guangxi, and northern Vietnam. These Yue groups, encompassing subgroups such as the Luoyue and Minyue, were non-Han peoples characterized by distinct linguistic, tattooing, and short-haired customs as described in Han-era records, with no unified ethnic identity beyond loose tribal affiliations.[28] In contrast, the ruling elite comprised Han Chinese migrants from the Central Plains, initially numbering in the thousands under Zhao Tuo's Qin-era garrisons, who established administrative control in urban centers like Panyu (modern Guangzhou).[15] This Han minority, estimated at less than 5% of the populace based on garrison sizes and tomb inscriptions, dominated governance and military leadership, fostering a dual structure where Yue commoners provided labor and tribute.[22] Population dynamics during Nanyue's existence (204–111 BC) were marked by gradual Han demographic penetration through military-agricultural colonies (tuntian), which Zhao Tuo expanded from Qin precedents to secure frontiers and cultivate rice paddies, drawing an estimated 10,000–20,000 additional northern settlers over decades.[15] Total population likely ranged from 1 to 2 million, inferred from Han commandery户籍 (household registrations) in annexed regions and archaeological site densities, though sparse records preclude precision; for instance, Nanhai Commandery alone supported dense Yue villages alongside Han outposts.[29] This influx, driven by incentives like land grants to veterans, accelerated intermarriage and elite Yue adoption of Han practices, contributing causally to localized Sinicization without displacing the Yue majority numerically.[30] Modern genetic analyses of southern Chinese ancient remains, while not exclusively Nanyue-focused, indicate admixture patterns where northern Han Y-chromosome lineages appear in post-conquest tombs, supporting historical accounts of settler integration over romanticized views of unadulterated Yue persistence.[31] Nationalist interpretations exaggerating a "pure Yue" demographic, often in Vietnamese historiography, overlook this evidenced Han catalytic role, as primary sources like Sima Qian's Shiji prioritize elite migration's assimilative effects.[32]Government and Administration

Central Governance Structure

The central governance of Nanyue was a monarchy under the absolute authority of the king, headquartered in Panyu, with administrative practices adapted from Qin dynasty models to accommodate the kingdom's multi-ethnic composition. Upon proclaiming himself king in 204 BC, Zhao Tuo organized a core bureaucracy featuring Chinese-derived titles, including left and right marshals for oversight, grand generals for coordination, inner historians for records, and other functionaries such as court judges, imperial secretaries, and palace commanders, thereby centralizing decision-making while retaining Qin-era hierarchies. This system emphasized the king's personal edicts and direct appointments, fostering loyalty among imported northern officials and co-opted southern elites. To integrate local power structures, the monarchy enfeoffed hereditary positions to compliant Yue tribal leaders, creating a layered aristocracy that supported central directives without fully displacing indigenous hierarchies, as evidenced by the incorporation of Yue chieftains into noble ranks under Zhao Tuo's consolidation. Legal administration blended Qin statutes—focusing on standardized penalties and taxation—with pragmatic exemptions for Yue customs, such as permitting traditional marriage practices and body modifications that Qin laws had suppressed; Zhao Tuo's edicts, preserved in Sima Qian's Shiji, explicitly relaxed enforcement to avert unrest, prioritizing governability over uniform Sinicization. Successive rulers maintained this framework, with the chancellorship emerging as a pivotal role for civil administration; Lü Jia, appointed prime minister under Zhao Yingqi around 122 BC, exemplified this by managing internal policies and advising on Han relations, though his influence highlighted tensions between central mandates and regional autonomy.[33] Such adaptations ensured short-term stability but exposed vulnerabilities to factionalism, as central authority relied heavily on personal allegiance rather than institutionalized checks.Military Apparatus

The military of Nanyue relied heavily on conscripted infantry from Yue tribal groups, supplemented by units trained in Qin military traditions under Zhao Tuo's initial command. These forces emphasized mobility in rugged terrain, drawing on local knowledge for guerrilla tactics, but lacked the standardized organization and logistics of northern Chinese armies. Archaeological evidence from royal tombs reveals iron armor and weapons, indicating adoption of metallurgical advances, yet production scales remained limited compared to Han capabilities.[34] Nanyue incorporated specialized units, including war elephants acquired through the conquest of Âu Lạc around 180 BC, which provided shock value in close combat but proved vulnerable to disciplined ranged assaults. Border fortifications, such as reinforced positions along northern riverine approaches, were established by Zhao Tuo to deter Han incursions, with defenses focused on chokepoints rather than extensive walls.[35][36] In the decisive Han campaign of 111 BC, Nanyue fielded an army exceeding 100,000 troops, yet suffered overwhelming defeats due to inferior coordination, supply vulnerabilities, and technological disparities in weaponry like massed crossbows. Sima Qian's Shiji records Han forces, numbering around 100,000 to 200,000, exploiting these weaknesses through superior firepower and sustained logistics, leading to the kingdom's rapid collapse.[37][38]Policies on Ethnic Integration and Sinicization

Zhao Tuo initially pursued ethnic integration by adopting Yue customs to secure loyalty from local tribes, including changing his attire and caps to Yue styles and appointing indigenous lords as officials.[11] He encouraged Han settlers to intermarry with Yue women, fostering hybrid families that bridged the two groups and promoted administrative harmony across diverse populations.[11] This approach prioritized pragmatic stability over immediate cultural imposition, as evidenced by the kingdom's policy of "Harmonizing and Gathering the Hundred Yue," which integrated Han immigrants with native Yue structures without enforcing uniform Han norms on the populace.[22] Following diplomatic submissions to the Han dynasty in 196 BC, Zhao Tuo reversed course, restoring Qin-era laws and Han-style rites to align with northern expectations and legitimize his rule among Han elites. Successors like Zhao Mo accelerated Sinicization among the nobility, adopting Han administrative titles, legal codes, and burial practices, as demonstrated by the second king's tomb, which contained over 1,000 artifacts including Han-patterned jade suits, silk garments, and ritual bronzes mirroring imperial Han conventions.[1] These elite-focused policies aimed to cultivate loyalty through shared cultural symbols with the Han court, while maintaining Yue elements in lower administration to avoid alienating tribal majorities. Archaeological evidence from Nanyue tombs underscores this selective Sinicization as statecraft for cohesion: rulers' adoption of Han funerary rites contrasted with persistent Yue motifs in artifacts, indicating a strategic blend that reinforced central authority without broad coercion.[39] Intermarriage persisted as a tool for integration, with royal unions and official appointments drawing Yue nobility into Han-influenced circles, though mass conversion to Han customs remained limited due to the kingdom's peripheral geography and tribal autonomies.[40] This causal dynamic—elite assimilation for diplomatic and internal stability—prevented fragmentation but sowed tensions exploited during the Han conquest in 111 BC.Economy

Agricultural Base and Natural Resources

The economy of Nanyue relied heavily on wet-rice cultivation in the fertile alluvial plains and deltas of the Pearl River basin, where the subtropical monsoon climate provided ample rainfall and riverine flooding for paddy fields. Archaeological and textual evidence from the Lingnan region, encompassing Nanyue's core territories, confirms rice as the staple crop, with fields yielding sufficient surpluses to support urban centers like Panyu (modern Guangzhou).[41] Supplemented by drought-resistant millets, tropical fruits, and vegetables such as gourds, this mixed farming system sustained a population estimated in the hundreds of thousands, though yields were initially limited by rudimentary tools and uneven water control before northern influences.[41] Irrigation infrastructure, pioneered by Qin expeditions into Lingnan around 214 BC, transformed marginal wetlands into productive rice paddies through canals and dikes that captured monsoon floods and enabled double-cropping in lowland areas. These hydraulic works, maintained and expanded under Nanyue rulers, mitigated seasonal droughts and supported population growth, with historical records noting increased agricultural output that underpinned the kingdom's military and administrative capabilities.[42] Beyond agriculture, Nanyue's natural resources derived from its diverse ecosystems, including coastal fisheries yielding pearls from pearl oysters in the Gulf of Tonkin and South China Sea shallows, which were prized for ornamental and medicinal uses. Inland forests and savannas provided ivory from Asian elephants and rhinoceros horns, harvested through hunting by local tribes and forming key extractive assets that complemented subsistence farming. Tribute missions to the Han court in the 2nd century BC regularly included these items—such as thousands of catties of pearls and tusks—highlighting their economic significance and the kingdom's integration into broader regional exchange patterns without full dependence on northern grain imports.[43]Trade Networks and Economic Exchanges

Nanyue's trade networks linked its southern territories to Han China via overland paths northward through the Lingnan region and maritime routes extending into the South China Sea, positioning the kingdom as a conduit for exchanges between northern empires and southeastern maritime domains.[44][45] These routes, leveraging pre-existing Yue maritime capabilities, facilitated the flow of goods from Guangzhou (Panyu), which emerged as a key nodal point.[46] The kingdom exported tropical raw materials prized in Han markets, including pearls, ivory, rhinoceros horns, kingfisher feathers, cinnamon, and aromatic woods, often in exchange for northern manufactured products like silk textiles, iron tools, lacquerware, and bronze items.[43][47] Archaeological evidence from elite contexts, such as the tomb of King Zhao Mo (r. 137–122 BC), yields numerous Han-imported silks and bronze artifacts, highlighting a trade imbalance where finished northern luxuries predominated over southern exports of unprocessed exotics.[48] Monetization advanced through the adoption of Han-style bronze coinage, with coins appearing in Nanyue tombs and settlements, enabling standardized internal market transactions in urban centers like Panyu and integrating local economies into broader Chinese monetary practices.[49] This economic alignment supported commercial hubs that processed and redistributed goods, though the reliance on northern currency underscored dependencies in the exchange system.[1]Culture and Society

Cultural Sinicization Processes

The rulers of Nanyue, originating from northern Han Chinese stock under founder Zhao Tuo (r. 204–137 BC), initiated top-down cultural assimilation by imposing Qin-Han administrative norms and imperial pretensions on Yue populations, including the use of Chinese-style titles and court protocols as early as Zhao Tuo's self-proclamation as emperor in 183 BC. This process intensified under his grandson Zhao Yingqi (r. 137–122 BC), who married a Han Chinese consort from Changsha commandery around 130 BC, whose influence promoted Han rituals and governance practices at the royal court to secure diplomatic favor from the Han dynasty.[50] Such intermarriages among elites exemplified pragmatic adaptation for political survival amid Han expansionism, blending Han lineage with local alliances while prioritizing northern cultural frameworks over indigenous Yue traditions.[51] Subsequent monarch Zhao Xing (r. 122–112 BC), son of the Han consort, further entrenched these shifts by aligning court observances with Han calendrical systems and ceremonial rites, including formalized ancestor veneration modeled on Zhou-Han precedents to reinforce dynastic legitimacy. Dynastic histories like the Shiji and Hanshu, compiled from Han bureaucratic records and Nanyue submissions, document these adoptions as deliberate elite strategies to mitigate conquest risks, though such sources reflect Han-centric perspectives that may understate residual Yue elements to justify later annexation. This elite-driven Sinicization contrasted with persistent Yue practices among commoners, underscoring a hierarchical divide where ruling assimilation served as a buffer against imperial overreach rather than wholesale cultural erasure.[52] Claims of unadulterated "Yue purity" in Nanyue overlook the causal reality of empire-building: Zhao lineage's Han origins and strategic embrace of rituals—such as seasonal sacrifices and filial piety codes—functioned as tools for internal cohesion and external signaling, evidenced by tribute missions incorporating Han liturgical forms by the 120s BC. Empirical patterns from contemporaneous states like Minyue show similar elite concessions yielding temporary autonomy, affirming cultural adaptation as a rational response to power asymmetries rather than ideological affinity.[51]Language and Script Usage

Administrative and official documents of Nanyue employed Classical Chinese written in seal script (zhuanshu) and later clerical script (lishu), reflecting the adoption of Qin-Han bureaucratic standards by its Zhao rulers. Inscriptions on jade seals, such as the "Zhao Mo" seal featuring the characters "赵眜" in incised seal script, exemplify this usage for royal authentication.[53] Excavated wooden slips from the Nanyue palace site bear ink-written characters primarily in lishu, with traces of zhuanshu style, indicating continuity in official record-keeping. No indigenous writing system emerged for the Yue languages spoken by the local population, as archaeological evidence yields no inscriptions in non-Sinitic scripts from the kingdom's core territories. Yue dialects—likely proto-Vietic or Tai-Kadai varieties among the Baiyue peoples—remained confined to oral vernacular use among the masses, without recorded literary output.[54] Among the elite, bilingualism prevailed, with rulers and officials proficient in Classical Chinese for governance while presumably retaining familiarity with local Yue speech for administration over diverse subjects. This linguistic hierarchy underscored Sinicization efforts, prioritizing Chinese as the prestige language of power and leaving Yue expressions undocumented in writing, a pattern consistent with the kingdom's hybrid yet Chinese-dominated court culture.[55]Material Culture from Archaeological Evidence