Recent from talks

Contribute something

Nothing was collected or created yet.

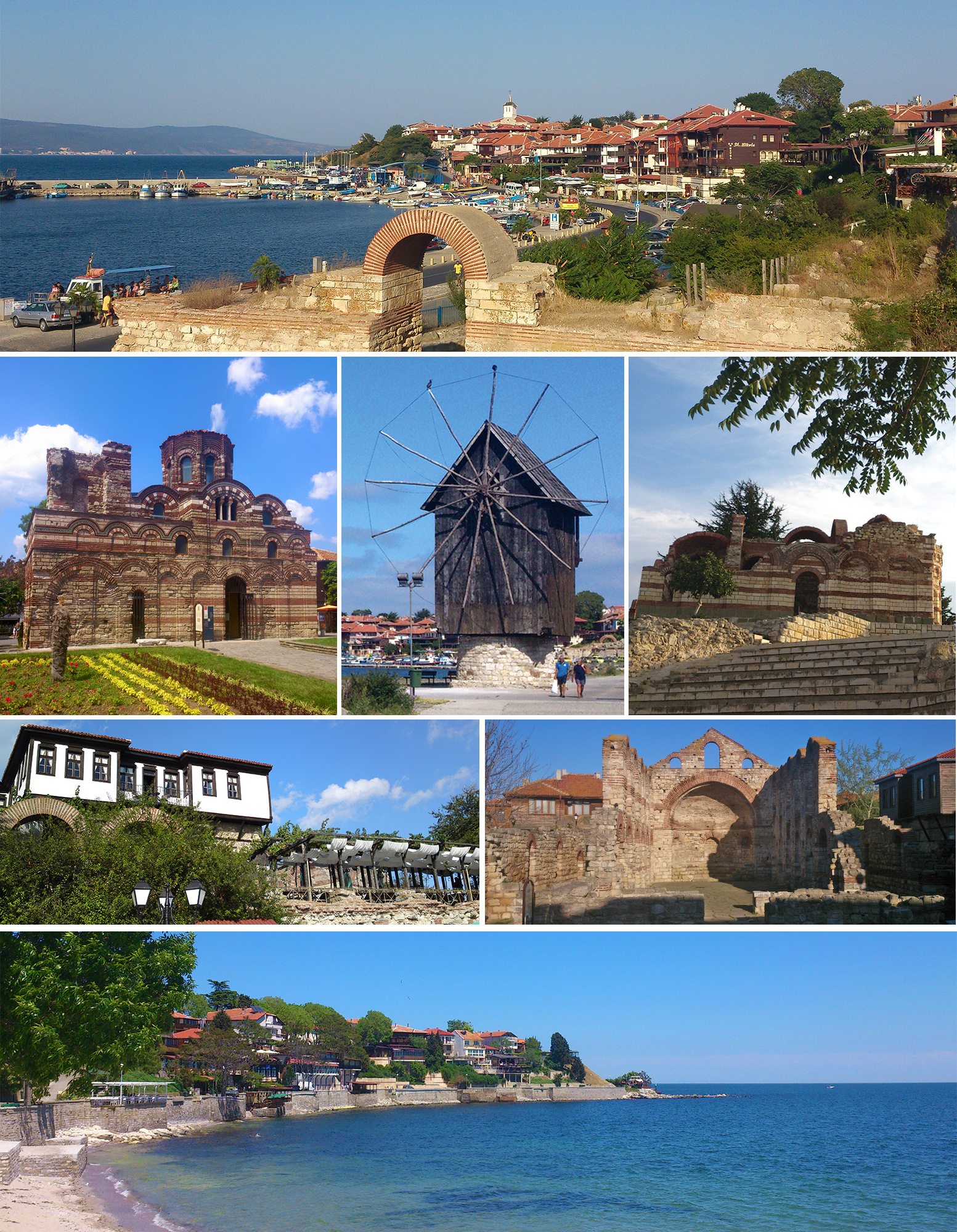

Nesebar

View on WikipediaNesebar (often transcribed as Nessebar and sometimes as Nesebur, Bulgarian: Несебър, pronounced [nɛˈsɛbɐr]) is an ancient city and one of the major seaside resorts on the Bulgarian Black Sea Coast, located in Burgas Province. It is the administrative centre of the homonymous Nesebar Municipality. Often referred to as the "Pearl of the Black Sea", Nesebar is a rich city-museum defined by more than three millennia of ever-changing history. The small city exists in two parts separated by a narrow human-made isthmus with the ancient part of the settlement on the peninsula (previously an island), and the more modern section (i.e., hotels and later development) on the mainland side. The older part bears evidence of occupation by a variety of different civilisations over the course of its existence.

Key Information

It is one of the most prominent tourist destinations and seaports on the Black Sea, in what has become a popular area with several large resorts—the largest, Sunny Beach, is situated immediately to the north of Nesebar.

Nesebar has on several occasions found itself on the frontier of a threatened empire, and as such it is a town with a rich history. Due to the city's abundance of historic buildings, UNESCO came to include Nesebar in its list of World Heritage Sites in 1983.[1]

As of December 2019, the town has a population of 13,600 inhabitants.[2]

Name

[edit]The settlement was known in Greek as Mesembria (Greek: Μεσημβρία), sometimes mentioned as Mesambria or Melsembria, the latter meaning the city of Melsas.[3] According to a reconstruction the name might derive from Thracian Melsambria.[4] Nevertheless, the Thracian origin of that name seems to be doubtful. Moreover, the tradition pertaining to Melsas, as founder of the city is tenuous and belongs to a cycle of etymological legends abundant among Greek cities. It also appears that the story of Melsas was a latter reconstruction of the Hellenistic era, when Mesembria was an important coastal city.[5]

Before 1934, the common Bulgarian name for the town was Месемврия, Mesemvriya. It was replaced with the current name, which was previously used in the Erkech dialect spoken close to Nesebar.[6] Both forms are derived from the Greek Mesembria.

History

[edit]

Bulgarian archaeologist Lyuba Ognenova-Marinova led six underwater archaeological expeditions for the Bulgarian Academy of Sciences (BAS) between 1961 and 1972[7][8] in the waters along the Bulgarian Black Sea Coast. Her work led to the identification of five chronological periods of urbanization on the peninsula surrounding Nesebar through the end of the second millennium B.C., which included the Thracian protopolis, the Greek colony Mesambria, a Roman-ruled village to the Early Christian Era, the Medieval settlement and a Renaissance era town, known as Mesembria or Nessebar.[7]

Engineering around the peninsula coastline was undertaken in 1980s both to preserve the coastline (and its historic significance) and to consolidate the area as a port.[9]

Antiquity

[edit]Originally a Thracian settlement, known as Mesembria, the town became a Greek colony when settled by Dorians from Megara at the beginning of the 6th century BC, then known as Mesembria. It was an important trading centre from then on and a rival of Apollonia (Sozopol). It remained the only Dorian colony along the Black Sea coast, as the rest were typical Ionian colonies. At 425-424 BC the town joined the Delian League, under the leadership of Athens.[10]

Remains date mostly from the Hellenistic period and include the acropolis, a temple of Apollo and an agora. A wall which formed part of the Thracian fortifications can still be seen on the north side of the peninsula.

Bronze and silver coins were minted in Mesembria since the 5th century BC and gold coins since the 3rd century BC. The town fell under Roman rule in 71 BC, yet continued to enjoy privileges such as the right to mint its own coinage.[11]???

Medieval era

[edit]

It was one of the most important strongholds of the Eastern Roman Empire from the 5th century AD onwards, and was fought over by Byzantines and Bulgars, being captured and incorporated in the lands of the First Bulgarian Empire in 812 by Khan Krum after a two-week siege only to be ceded back to Byzantium by Knyaz Boris I in 864 and reconquered by his son Tsar Simeon the Great. During the time of the Second Bulgarian Empire it was also contested by Bulgarian and Byzantine forces and enjoyed particular prosperity under Bulgarian tsar Ivan Alexander (1331–1371) until it was conquered by Crusaders led by Amadeus VI, Count of Savoy in 1366. The Bulgarian version of the name, Nesebar or Mesebar, has been attested since the 11th century.

Monuments from the Middle Ages include the 5–6th century Stara Mitropoliya ("old bishopric"; also St Sophia), a basilica without a transept; the 6th century church of the Virgin; and the 11th century Nova Mitropoliya ("new bishopric"; also St Stephen) which continued to be embellished until the 18th century. In the 13th and 14th century a remarkable series of churches were built: St Theodore, St Paraskeva, St Michael St Gabriel, and St John Aliturgetos.

The city was conquered by the Ottomans during the Bulgarian-Ottoman wars, but was then returned to the Byzantine Empire by the terms of the 1403 Treaty of Gallipoli.

Ottoman rule

[edit]The capture of the town by the Ottoman Empire in 1453 marked the start of its decline, but its architectural heritage remained and was enriched in the 19th century by the construction of wooden houses in style typical for the Bulgarian Black Sea Coast during this period. At the early 19th century many locals joined the Greek patriotic organization, Filiki Eteria, while at the outbreak of the Greek War of Independence (1821) part of the town's youth participated in the struggle under Alexandros Ypsilantis.[12][dead link]

Nesebar (Misivri) was a kaza centre in İslimye sanjak of Edirne Province before 1878.[13]

Third Bulgarian state

[edit]After the Liberation of Bulgaria from Ottoman rule in 1879, Nesebar became part of the autonomous Ottoman province of Eastern Rumelia in Burgaz department until it united with the Principality of Bulgaria in 1885. Around the end of the 19th century Nesebar was a small town of Greek fishermen and vinegrowers. In 1900 it had a population of approximately 1.900,[12] of which 89% were Greeks,[14] but it remained a relatively empty town.[15] It developed as a key Bulgarian seaside resort since the beginning of the 20th century. After 1925 a new town part was built and the historic Old Town was restored.

Churches

[edit]Nesebar is sometimes said to be the town with the highest number of churches per capita.[1], [2] Today, a total of forty churches survive, wholly or partly, in the vicinity of the town.[12] Some of the most famous include:

- the Church of St Sophia or the Old Bishopric (Stara Mitropoliya) (5th–6th century)

- the Basilica of the Holy Mother of God Eleusa (6th century)

- the Church of John the Baptist (11th century)

- the Church of St Stephen or the New Bishopric (Nova Mitropoliya) (11th century; reconstructed in the 16th–18th century)

- the Church of St Theodore (13th century)

- the Church of St Paraskevi (13th–14th century)

- the Church of the Holy Archangels Michael and Gabriel (13th–14th century)

- the Church of Christ Pantocrator (13th–14th century)

- the Church of St John Aliturgetos (14th century)

- the Church of St Spas (17th century)

- the Church of St Clement (17th century)

- the Church Assumption of the Holy Virgin (19th century)

Whether built during the Byzantine, Bulgarian or Ottoman rule of the city, the churches of Nesebar represent the rich architectural heritage of the Eastern Orthodox world and illustrate the gradual development from Early Christian basilicas to medieval cross-domed churches.

Sports

[edit]- Football

The local team of PFC Nesebar participates in the Second Professional Football League. The stadium capacity is 6000 spectators, field dimensions are 100/50 m and some complementary fields are available for rent or practicing.

- Tennis

There are many possibiltes to play tennis in the area during the summer season. The two main clubs with outdoor and indoor courts are TC Egalite[16] and Tennis academy Nesebar.

Namesakes

[edit]Nesebar Gap on Livingston Island in the South Shetland Islands, Antarctica is named after Nesebar.

Gallery

[edit]-

Church of Christ Pantokrator

-

Church of St. Stephen

-

Church of St. John the Baptist

-

The wooden windmill before the town entrance

-

Typical revival houses in the old town

-

Church of St. Sophia

-

Nessebar center

-

Panorama of Nesebar

-

New town Nesebar

-

Statue of the fisherman/St. Nicholas/the new Noah

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "Ancient City of Nessebar". UNESCO World Heritage Centre. Archived from the original on May 23, 2024.

- ^ "6.1.4. Population by towns and sex – Table data". Bulgarian National Statistical Institute. Archived from the original on 2010-11-13. Retrieved 2011-01-08.

- ^ Shuckburgh, E.S., ed. (1976). Herodotos, VI, Erato ([Reprinted]. ed.). Cambridge: University Press. p. 236. ISBN 9780521052481.

- ^ Ivanov, Rumen Teofilov (2007). Roman cities in Bulgaria, Vol. 2. National Museum of Bulgarian Books and Polygraphy. p. 41. ISBN 9789544630171.

- ^ Nawotka, Krzysztof (1997). The Western Pontic cities: history and political organization. Hakkert. ISBN 9789025611125.

- ^ Deliradev, Pavel (1953). Contribution to the historical geography of Thrace (in Bulgarian). Publisher of the Bulgarian Academy of Sciences. p. 189.

- ^ a b Илиева (Ilieva), Павлина (Pavlina); Прешленов (Preshlenov), Христо (Christo) (2005). "Люба Огненова-Маринова—Ученият, Учителят И Човекът". In Стоянов (Stoyanov), Тотко (Totko); Тонкова (Tonkova), Милена (Milena); Прешленов (Preshlenov), Христо (Christo); Попов (Popov), Христо (Christo) (eds.). Heros Hephaistos: Studia In Honorem: Liubae Ognenova-Marinova [Luba Ognenova-Marinova—scientist, teacher and man] (PDF) (in Bulgarian). Sofia, Bulgaria: Археологически институт с Музей на БАН & Cobrxiur Университет “Св. Кл. Охридски”. pp. 7–11. ISBN 954-775-531-5. Archived from the original (PDF) on 22 July 2012.

- ^ Огненова-Маринова, Люба (30 October 2009). "Как Започнаха Подводните Археологически Проучвания В Несебър" [What started underwater archaeological research in Nessebar]. Morski Vestnik (in Bulgarian). Varna, Bulgaria: Morski Svyat Publishing House. Archived from the original on 14 April 2016. Retrieved 22 October 2016.

- ^ Preshlenov, H. (2022). "Postglacial Black Sea Level Rising, Urban Development and Adaptation of Historic Places. The case study of the city-peninsula of Nesebar (Bulgaria)". Internet Archaeology (60). doi:10.11141/ia.60.5.

- ^ Petropoulos, Ilias. "Mesembria (Antiquity)". Εγκυκλοπαίδεια Μείζονος Ελληνισμού, Εύξεινος Πόντος. Retrieved 8 June 2011.

- ^ "Blog". conservation environment. Retrieved 5 April 2018.

- ^ a b c Doncheva, Svetlana. "Mesimvria (Nesebar)". Εγκυκλοπαίδεια Μείζονος Ελληνισμού, Εύξεινος Πόντος. Retrieved 8 June 2011.

- ^ http://acikarsiv.ankara.edu.tr/fulltext/3066.pdf[permanent dead link]

- ^ Dragostinova, Theodora K. (2011). Between Two Motherlands: Nationality and Emigration among the Greeks of Bulgaria, 1900–1949. Cornell University Press. p. 26. ISBN 978-0801461163.

- ^ Fermor, Patrick Leigh, "The Broken Road," (2016: John Murray)(ISBN 9781590177549), at 259. "A strange, rather sad, rather beguiling spell haunted the cobbled lanes of this twinkling, twilight little town of Mesembria. Only secured by its slender tether to the mainland, the Black Sea seemed entirely to surround it. At first glance, churches appeared to outnumber the dwelling houses...But still some [people] remained, languishing and reluctant to leave their habitat of two and a half thousand years."

- ^ Tzvetanov, Tzvetan. "Tennis club Egalite".

- ^ "Norilsk", Wikipedia, 2023-11-18, retrieved 2023-11-26

- Evaluation of the International Council on Monuments and Sites, June 1983 (PDF file)

External links

[edit]Nesebar

View on GrokipediaGeography

Location and Physical Features

Nesebar is situated 36 kilometers northeast of Burgas in Burgas Province, Bulgaria, along the Bulgarian Black Sea Coast.[3] The town occupies a narrow rocky peninsula that extends approximately 850 meters into the Black Sea, with a width of about 350 meters, and is connected to the mainland by a slender isthmus.[3][4] This physical configuration, characterized by high cliffs and a rugged coastline, defines the town's distinctive geography and contributes to its scenic appeal.[5] The Old Town is confined to the peninsula, forming a compact historic core, while the New Town spreads across the adjacent mainland. Elevations in the area range from 10 to 30 meters above sea level, providing a low-lying coastal profile.[6][7] The peninsula is bordered by sandy beaches, including the expansive South Beach to the south with its fine golden sands and the more natural North Beach to the north, both offering access to the clear waters of the Black Sea.[8] Approximately 3 kilometers north lies the popular Sunny Beach resort, enhancing the region's coastal continuum.[9] Administratively, Nesebar serves as the center of Nesebar Municipality, which encompasses 420.4 square kilometers and includes 14 settlements, such as the towns of Obzor and Saint Vlas, as well as villages like Ravda and Tankovo.[10] This municipal territory integrates the peninsula town with surrounding rural and coastal areas, reflecting a blend of natural and developed landscapes along the Black Sea.[10]Climate

Nesebar experiences a humid subtropical climate (Köppen Cfa) influenced by the Black Sea, characterized by mild winters and hot summers.[11][12] The annual average temperature is approximately 13°C, with summer highs reaching 27–28°C in July and August, while winter lows drop to 0–2°C in January.[11][13] Sea breezes moderate summer humidity, keeping it relatively low despite the warmth, and contribute to comfortable conditions that support the region's tourism.[11] Precipitation totals around 500–600 mm annually, with the majority falling during the cooler months, particularly in autumn and winter; November is typically the wettest month at about 65 mm, while August sees the least at 34 mm.[11][13] Black Sea water temperatures range from 20–24°C in summer, peaking in August, which enhances the appeal for coastal activities.[11] The peninsula faces environmental challenges from occasional winter storms, which bring strong northerly and northeasterly winds and contribute to coastal erosion risks, with Bulgaria's Black Sea shoreline showing erosion along 70.8% of its length.[14][15] Recent climate trends indicate warming patterns, with summer temperatures in the Black Sea region rising slightly—up to 1°C above 20th-century averages—based on data from 2020 to 2025, aligning with Bulgaria's overall temperature increase of about 0.9°C from 1988–2020 compared to the 1961–1990 baseline.[16][17]Etymology

Historical Names

The earliest known name for the settlement at Nesebar derives from its Thracian origins, possibly as "Menebria" or a variant form, linked to the Thracian term "bria" meaning "city" and associated with a local figure named Melsa, interpreted as a hero, king, or deity, suggesting "city of Melsa."[18] Ancient sources like Strabo record "Menebria" as tied to a founder named Mena, while Stephanus of Byzantium explicitly attributes "Mesembria" to Thracian roots under Melsa's protection, supported by epigraphic evidence from the region.[18] In the late 6th century BCE, Dorian Greek colonists from Megara established a colony on the site, adopting and adapting the name to "Mesembria," which retained Thracian elements while reflecting Greek linguistic integration.[19] This name emphasized the city's strategic coastal position and appears in classical Greek texts, such as those by Herodotus and Scymnos of Chios, highlighting its role in Black Sea trade networks.[18] During the Roman and Byzantine periods, the name "Mesembria" was largely retained, with occasional Latinized forms like "Mesembria" in administrative records, underscoring its continued importance as a key port in the Greek Pentapolis on the Euxine Sea and a Byzantine kommerkion for trade with inland regions.[20] The city featured prominently in ancient trade documents and Byzantine chronicles, maintaining its Hellenic nomenclature amid imperial transitions.[2] By the 9th to 10th centuries, under Bulgarian rule following Khan Krum's conquest in 812 CE, Slavic settlers influenced a phonetic shift, evolving "Mesembria" into "Nesebar" or "Nesebăr," as recorded in early Bulgarian chronicles and reflecting local dialect adaptations like those in the Erkech variant.[21] This medieval form marked the integration of the settlement into Slavic-Bulgarian linguistic and political spheres, persisting in historical accounts through the period.[22]Modern Usage

The official name of the town in Bulgarian is Nesebar, rendered in Cyrillic as Несебър, a form adopted by decree in 1934 to replace the earlier common usage of Mesemvriya.[23] Common transliterations of the Cyrillic include Nessebar and Nesebăr, reflecting variations in romanization practices.[24] In international English-language contexts, the name appears as Nesebar or Nessebar, with the latter preferred in official designations such as the UNESCO World Heritage Site "Ancient City of Nessebar," inscribed in 1983 for its cultural and architectural significance.[2] Locally, the name holds strong symbolic value in Bulgarian identity, prominently featured in national tourism campaigns and materials from the official Nessebar Tourist Information Center, which promotes it as a key cultural treasure without any notable disputes over nomenclature.[25] Bulgaria's accession to the European Union in 2007 prompted further standardization of place names through the adoption of the national romanization system (BDS 1596:2009), which officially transliterates Несебър as Nesebăr in EU documents and international agreements.[26]History

Antiquity

The origins of Nesebar trace back to a Thracian settlement known as Menebria, established around the 2nd millennium BCE and fortified by the 8th century BCE, with evidence from pottery fragments and nearby burial mounds indicating early human activity on the rocky peninsula.[2] Archaeological excavations in the necropolis have uncovered Thracian tombs containing burial goods such as ceramics and tools, underscoring the site's role as a pre-Greek coastal outpost.[27] These findings highlight the Thracians' strategic use of the location for defense and resource exploitation along the Black Sea. In the early 6th century BCE, around 585 BCE, Dorian Greeks from Megara colonized the site, renaming it Mesembria and transforming it into a prominent polis and key emporium in the Black Sea trade network.[19] The city facilitated the exchange of local products like grain, salted fish, and metals for imports such as olive oil and Attic pottery, fostering economic prosperity and cultural ties with other Hellenic centers.[27] By the 5th century BCE, Mesembria had developed stone fortifications, an acropolis, and public structures including a temple to Apollo and an agora, reflecting its status as a thriving commercial hub.[2] During the Hellenistic period, following Philip II of Macedon's conquest of Thrace in 339 BCE, Mesembria came under Macedonian influence, maintaining autonomy while minting its own silver and bronze coins from the 5th century BCE onward, with gold issues beginning in the 3rd century BCE.[28] The city expanded with Hellenistic villas, enhanced defenses, and athletic facilities like a theatre, supporting a vibrant cultural life amid continued trade dominance.[27] At its peak in the Roman era, after incorporation into the province of Thracia around 71 BCE, Mesembria featured Roman-built aqueducts, reinforced fortifications, and infrastructure that sustained its role as a vital port until the early 4th century CE.[29] Key archaeological sites, including the necropolis with Thracian tombs and Hellenistic remains like the acropolis and religious buildings, exemplify ancient urban planning and multilayered heritage, contributing to the site's inscription on the UNESCO World Heritage List under criteria (iii) for its testimony to successive civilizations and (iv) for its outstanding architectural ensemble from antiquity.[2] These excavations provide irrefutable evidence of Mesembria's evolution from Thracian roots to a Roman provincial center, with the name's origins linked to the Thracian founder Mena (detailed in etymology sections). The site's antiquity laid the foundation for its later Byzantine prominence.Medieval Era

During the 5th to 10th centuries, Nesebar, then known as Mesembria, served as a vital Byzantine stronghold on the western Black Sea coast, functioning as a strategic port to counter invasions from northern tribes. The city was rebuilt as a prominent Christian center, with early basilicas exemplifying its spiritual significance; notable among these is the three-aisled Basilica of Hagia Sophia (Stara Mitropolia), constructed in the late 5th or early 6th century and reconstructed in the 9th century to incorporate Byzantine architectural forms.[2][30] Additional basilicas, such as the Old Bishopric, underscored Mesembria's role as a "remarkable spiritual hearth of Christian culture" for over a millennium, amid ongoing fortifications that included medieval walls and a central fortress.[2][31] Nesebar was incorporated into the First Bulgarian Empire in 812 CE under Khan Krum (r. 803–814), marking a shift from Byzantine dominance. The empire underwent significant expansion during this period, incorporating key coastal regions like Mesembria and enhancing its administrative and ecclesiastical status; the city emerged as an important bishopric, with St. Sophia serving as its central church.[32][33] This period solidified Nesebar's position within the Bulgarian realm, blending Slavic influences with existing Byzantine structures while maintaining its port functions.[2] The Second Bulgarian Empire (1185–1396) represented the zenith of Nesebar's medieval prosperity during the 12th to 14th centuries, characterized by cultural and economic flourishing. Over 40 churches were constructed, primarily in the 13th and 14th centuries, reflecting the Bulgarian Renaissance style with Byzantine-inspired cross-in-square plans, ceramic decorations, and opus mixtum masonry; prominent examples include the Church of St. Sophia (13th century) and the Church of Christ Pantocrator.[2][34] Trade networks expanded vigorously, fostering ties with Italian city-states such as Venice and Genoa, which facilitated maritime commerce in goods like grain, wine, and textiles through Nesebar's harbor.[35][32] Amid 13th-century threats, including Mongol raids that impacted Bulgarian territories, Nesebar's fortifications were reinforced with additional walls, towers, and gates to bolster defenses against invasions.[2] This era's architectural legacy exemplifies a fusion of Byzantine and Bulgarian artistic traditions, evident in the churches' ornate facades and iconography, contributing to the site's recognition under UNESCO criterion (iii) as an outstanding testimony to medieval cultural and historical heritage.[2][34]Ottoman Rule

Nesebar fell to the Ottoman Empire in 1453 under Sultan Mehmed II, coinciding with the conquest of Constantinople and marking the end of Byzantine dominance in the region. The town, referred to as Misivri in Ottoman administrative records, experienced a significant decline in its strategic importance as a port, with trade routes shifting southward to the developing harbor at Burgas. This transition reduced Nesebar's role in regional commerce, transforming it from a bustling medieval center into a peripheral settlement.[36][23] From the 16th to 18th centuries, Nesebar's population dwindled to approximately 2,000 inhabitants, reflecting broader economic stagnation and the town's relegation to a modest fishing village. Its economy centered on small-scale activities such as fishing and limited trade in salt and fish products, with exports of salt from nearby pans noted even in the immediate pre-conquest period. Heavy Ottoman taxation burdened the local population, prompting migrations to more prosperous areas and contributing to the decay of medieval structures, including some churches that were converted to mosques, such as the Old Metropolitan Church (St. Sophia). Periodic fires in the 17th century further damaged wooden buildings and fortifications, exacerbating the town's physical decline.[37][21] In the 19th century, Nesebar saw stirrings of Bulgarian national awakening amid growing resistance to Ottoman rule. The town participated in the April Uprising of 1876, a widespread revolt against imperial authority that, though suppressed, highlighted local discontent. Ottoman liberation came in 1878 through Russian intervention during the Russo-Turkish War (1877–1878), integrating Nesebar into the newly autonomous Principality of Bulgaria. By this time, the population had reached around 3,000, but medieval sites continued to suffer from neglect and environmental degradation, setting the stage for later preservation efforts.[38])Modern Period

Following the liberation from Ottoman rule in 1878, Nesebar was incorporated into the autonomous province of Eastern Rumelia within the Ottoman Empire, becoming fully part of the Principality of Bulgaria after unification in 1885. The town emerged as a local administrative center, supporting regional governance and economic activities along the Black Sea coast. During the interwar period (1918–1939), Nesebar's population expanded steadily due to migration and economic opportunities, reaching approximately 5,000 inhabitants by the 1920s. This era also marked the initial stirrings of tourism, as the town's exceptional historical and architectural heritage gained wider recognition in the 1920s and 1930s, drawing early visitors to its preserved medieval structures and scenic peninsula location. Under communist rule from 1944 to 1989, Nesebar was nationalized and transformed into a prominent seaside resort to promote state tourism and economic development. The adjacent Sunny Beach complex began construction in 1958 as a planned international holiday destination, boosting the area's appeal and integrating Nesebar into Bulgaria's Black Sea tourism network. Archaeological excavations intensified in the 1950s, uncovering artifacts from Thracian, Greek, Roman, and Byzantine periods that enriched the site's cultural narrative. In 1956, the Old Town was officially declared an architectural-historical reserve of national importance through Ordinance No. 243 of the Council of Ministers, ensuring systematic preservation efforts. The post-communist transition after 1989 brought renewed focus on heritage and sustainable growth, culminating in the inscription of the Ancient City of Nessebar on the UNESCO World Heritage List in 1983 for its outstanding universal value as a testament to multilayered cultural influences. Bulgaria's European Union accession in 2007 spurred infrastructure enhancements, including improved roads, utilities, and heritage restoration funded by EU programs, further elevating Nesebar's status as a cultural and tourist hub. Key milestones include the 2011 census, which recorded 28,957 residents in the municipality, and a 2024 estimate of 33,749, with the population as of December 31, 2024, estimated at 33,749, reflecting ongoing demographic shifts driven by seasonal residency and economic migration.[39] In recent years, Nesebar has experienced a 13% population increase in 2023, attributed to tourism-related employment and residential development. The local tourism sector rebounded robustly from the COVID-19 downturn between 2020 and 2025, with visitor numbers surpassing pre-pandemic levels by 2023 through diversified offerings like cultural tours and eco-experiences. Environmental initiatives, including coastal monitoring and erosion mitigation studies, have addressed threats from sea-level rise and urban expansion on the vulnerable peninsula, supported by UNESCO recommendations and national research programs.Demographics

Population

The town of Nesebar recorded a population of 13,600 inhabitants according to the 2019 estimate from the National Statistical Institute of Bulgaria. By 2024, the town population is estimated at 16,800.[40] The Nesebar municipality has an estimated population of 33,749 in 2024, encompassing approximately 15,000 permanent residents alongside a substantial seasonal influx driven by tourism.[39] Historically, the town's population has shown steady growth, rising from around 2,000 residents in the late 19th century to 10,000 by 2000, reflecting post-Ottoman development and modernization.[41] Recent trends indicate accelerated expansion, with a significant increase in 2023 attributed to migration linked to tourism opportunities. The municipality's population density stands at 80.27 inhabitants per square kilometer, with the majority concentrated in the New Town area due to its modern infrastructure and proximity to coastal resorts.[39] Population trends suggest continued annual growth through 2030, fueled by inflows of retirees and foreign nationals seeking the region's mild climate and lifestyle, contrasting with Bulgaria's national demographic decline.[42] This growth underscores Nesebar's appeal as a retiree and expatriate destination, briefly intersecting with broader ethnic dynamics detailed elsewhere. As of November 2025, no major changes to these estimates have been reported by the NSI.Ethnic and Religious Composition

Nesebar's ethnic composition is overwhelmingly Bulgarian, reflecting broader trends in coastal Bulgaria. According to the 2021 census conducted by the National Statistical Institute (NSI), 85.9% of residents in Nesebar Municipality who declared their ethnicity identified as Bulgarian, with Turks comprising 4.0%, Roma 2.6%, and other groups or indefinable responses accounting for 7.5%. This distribution is similar to the 2011 census, where Bulgarians made up 85.8%, Turks 4.8%, Roma 2.8%, and others 6.6%, indicating stability in the dominant ethnic structure over the decade. Religiously, the population aligns closely with ethnic lines, with Eastern Orthodoxy predominant. The 2021 NSI census data for the municipality shows that 73.0% of those who responded identified as Christian (predominantly Eastern Orthodox, tied to the Bulgarian majority), 3.1% as Muslim (largely associated with the Turkish community), 8.3% as having no religion, and 0.1% as other religions, with the remainder not declaring. Nationally, Bulgaria's religious landscape features higher Muslim affiliation at around 10%, but Nesebar's figures reflect its lower Turkish demographic share.[43] Historically, Nesebar's demographics underwent significant transformations. After Bulgaria's liberation from Ottoman rule in 1878, an influx of Bulgarian settlers from inland regions bolstered the Christian population amid the departure of some Muslim residents. By 1900, the town was approximately 89% Greek Orthodox, a legacy of its Byzantine and Ottoman-era role as Messembria, but the Balkan Wars (1912–1913) and subsequent Greco-Bulgarian population exchanges in the 1920s displaced most Greeks, replacing them with Bulgarian migrants and reducing non-Bulgarian shares. Throughout the 20th century, Turkish percentages declined further due to economic migrations and assimilation pressures, dropping from higher levels in the early post-Ottoman period to the current minority status. In contemporary dynamics, the core ethnic and religious makeup is augmented by transient diversity from seasonal tourism and labor. Post-2022 Russian invasion of Ukraine, Nesebar has hosted notable numbers of Ukrainian refugees; as of 2025, Bulgaria hosts approximately 75,000 under temporary protection, with significant presence in the Burgas region supported by local initiatives like child welfare hubs.[44][45] Inter-ethnic and inter-religious tensions remain low, fostering a cohesive community environment despite these influxes.Government and Administration

Municipal Structure

Nesebar Municipality operates as a second-level administrative unit within Burgas Province, Bulgaria, encompassing a total area of approximately 423 square kilometers along the Black Sea coast. It is led by a mayor, elected by popular vote every four years, who heads the executive branch, and a 41-member municipal council responsible for legislative oversight and policy approval. The council convenes regularly to address local issues, with decisions implemented through specialized administrative departments handling finance, public procurement, and urban planning.[46][47] As of the 2023 local elections, the mayor is Nikolai Dimitrov, an independent candidate who secured a fifth consecutive term with a narrow victory in the runoff. The municipal administration's main offices are situated in the modern "New Town" section of Nesebar, facilitating efficient governance while preserving the historic Old Town as a UNESCO site. The municipality serves a population of 33,749 (2024 estimate), with its 2024 budget totaling 105.45 million BGN, allocated primarily to state-delegated activities, infrastructure, and local development initiatives.[48][49] Administratively, Nesebar Municipality comprises 14 settlements, including three towns—Nesebar, Obzor, and Saint Vlas—and 11 villages such as Emona, Gradina, and Tankovo. These divisions enable localized management of services across diverse coastal and rural areas. Key functions include issuing tourism permits, such as regulated vehicle access to the pedestrian-only Old Town to protect heritage sites, overseeing cultural preservation programs like the "Together for Old Town Nesebar" fund, and maintaining infrastructure through projects like road repairs and waste management. Since Bulgaria's EU accession in 2007, the municipality has accessed European funding for initiatives including energy efficiency upgrades in public buildings and landfill reclamation in Obzor, enhancing local sustainability.[50][51][52] Decentralization reforms in Bulgaria during the 2010s, including amendments to the Local Self-Government and Local Administration Act, bolstered municipal autonomy in areas like spatial planning and budgeting, allowing Nesebar to prioritize tourism-driven development and heritage conservation independently of central directives. These changes have enabled greater local control over revenue allocation and project implementation, though municipalities remain reliant on state transfers for about 80% of funds.[53][54]International Relations

Nesebar engages in international relations primarily through twin town partnerships, European Union programs, and collaborations focused on cultural heritage preservation and regional development. These efforts emphasize cultural exchanges, sustainable tourism, and environmental protection along the Black Sea coast. The municipality maintains twin town agreements with Kotor in Montenegro and the Pestszentlőrinc-Pestszentimre district (Budapest XVIII) in Hungary, established to promote mutual cultural exchanges, heritage conservation, and tourism cooperation.[55][56] These partnerships facilitate joint events, educational programs, and shared expertise in managing UNESCO-listed sites, given Kotor's similar status as a World Heritage property. As a UNESCO World Heritage site since 1983, Nesebar submits annual state of conservation reports to the World Heritage Committee and collaborates closely with the International Council on Monuments and Sites (ICOMOS) on site management and protection strategies.[57] These ties include joint advisory missions, such as the 2025 assessment of underwater heritage in collaboration with the Centre for Underwater Archaeology, aimed at enhancing research, evaluation, and conservation practices.[58] Nesebar benefits from EU involvement through cohesion and structural funds allocated for heritage restoration and regional development, as part of Bulgaria's broader 2014-2020 programming period, which supported projects enhancing cultural sites across the country.[59] Additionally, the municipality participates in Interreg programs, including the Black Sea Basin Programme and Balkan-Mediterranean initiatives, such as the joint project with Edirne, Turkey, to promote historic and touristic assets through preservation and cross-border tourism strategies.[60][61] Nesebar has been a member of the Union of Bulgarian Black Sea Local Authorities (UBBSLA) since the early 2000s, an organization uniting coastal municipalities to advance local governance, environmental sustainability, and tourism promotion via regional networks.[62] Through UBBSLA and Balkan frameworks, Nesebar contributes to initiatives like marine litter reduction and e-mobility corridors, fostering broader cooperation in the Black Sea region.[63] In recent years, particularly from 2022 to 2025, Nesebar has established support partnerships for Ukrainian refugees fleeing the war, including local initiatives like the Dobro Foundation, formed by Ukrainian residents in the municipality to provide safe learning and healing spaces for children.[45] These efforts align with Bulgaria's national temporary protection scheme, hosting integration programs and community aid in coordination with international organizations.[64]Economy

Tourism

Nesebar's tourism industry is a cornerstone of the local economy, drawing significant visitors to its UNESCO-listed Old Town and Black Sea beaches. During peak summer months, a majority of visitors are foreign, primarily from the United Kingdom, Germany, and Russia.[65] Key attractions include guided walks through ancient architecture, relaxation on sandy beaches, and visits to the modern yacht marina for boating activities. Many tourists arrive as day trips from the nearby Sunny Beach resort, which attracts between 500,000 and 1 million visitors annually during the summer season.[66] The mild Mediterranean climate enhances these experiences, particularly during warmer months.[2][67] Tourism infrastructure supports this influx with numerous hotels and accommodations in the town. The local port primarily handles small vessels and yachting, with limited cruise activity. To ensure long-term viability, a sustainable tourism plan for 2020-2030 focuses on environmental protection and balanced development.[68] Visitor patterns are highly seasonal, with the majority of arrivals concentrated between June and September due to favorable weather. The industry has benefited from Bulgaria's strong post-COVID recovery and record tourism in 2024, with over 13 million foreign visitors nationwide.[65] Despite growth, challenges include managing overtourism to prevent strain on resources and infrastructure. UNESCO actively monitors the site's integrity, emphasizing the need for controlled development to preserve cultural heritage amid rising visitor numbers.[57][69]Other Sectors

Fishing represents a traditional pillar of Nesebar's non-tourism economy, centered on the Black Sea fishery with operations from the local port. The port supports small-scale capture activities that target pelagic species such as sardines and mackerel.[70][71] The Nesebar Fish company, a key player, operates the largest fishing vessel in Bulgaria and has expanded into fish processing and a nationwide distribution network with cold storage facilities.[72] Fishing cooperatives have been integral to the sector since the 1950s, aiding organization and sustainability in Bulgarian coastal communities.[73] Services and trade contribute modestly, primarily through retail markets and craft production in the New Town district, employing a portion of the local workforce alongside small-scale EU-supported agriculture within the municipality.[74] Industry remains limited to minor construction and food processing activities, including fish-related operations, with no heavy industry permitted to safeguard the town's UNESCO-protected heritage. Recent developments in the 2020s emphasize green initiatives for sustainable fishing practices, aligning with EU standards and facilitating exports of seafood products to European markets.[75]Culture and Heritage

Architecture

Nesebar's Old Town exemplifies vernacular architecture through its 18th- and 19th-century wooden houses built on sturdy stone bases, a style emblematic of Black Sea regional traditions that evolved during the Bulgarian National Revival period. These two-story structures feature overhanging upper floors crafted from timber to offer shade against the intense coastal sun and to optimize living space on the constrained peninsula terrain. Narrow, winding cobblestone streets link the houses, creating an intimate urban fabric that emphasizes pedestrian scale and communal interaction, with many facades adorned in symmetrical designs and carved wooden details reflective of Balkan influences.[2][31] The urban layout of the Old Town divides the rocky peninsula into an upper section, centered on the ancient acropolis with its elevated Hellenistic remains, and a lower town that encompasses much of the 19th-century Revival-style development along the flatter coastal edges. This division fosters a layered spatial organization, where the higher elevations historically served defensive and public functions, while the lower areas accommodated residential and commercial growth during the Ottoman era's later phases. Fortifications further define this layout, with medieval walls—rebuilt extensively under Byzantine rule—encircling the peninsula's perimeter (approximately 2.4 kilometers, based on its 850 m by 350 m dimensions), including prominent gates like the East Gate at the isthmus connection to the mainland; these defenses, constructed from hewn stone, underscore Nesebar's strategic importance until their decline following the 1453 Ottoman conquest. The ensemble meets UNESCO criterion (iv) as a unique testimony to evolving architectural and town-planning traditions in the region.[2][76][77][78] Preservation efforts have been pivotal since 1956, when Nesebar was established as a national architectural and archaeological reserve to protect its homogeneous built heritage amid post-war urbanization pressures. Ongoing restorations in the 2020s, including updates to the municipality's Integrated Development Plan (originally 2021–2027, revised 2024), supported by international funding including EU cohesion policies, focus on rehabilitating traditional houses and infrastructure to mitigate tourism impacts and illegal modifications. UNESCO's 2024 monitoring notes progress on the updated plan but urges stronger controls against unauthorized development to protect the site's integrity. Unique elements like the 19th-century windmills—simple wooden structures originally used for grain milling, with one now adapted as a small museum exhibiting artifacts from the site's ancient necropolis—enhance the architectural narrative, alongside ethnographic museums housed in preserved Revival-era dwellings that display period furnishings and local crafts.[2][79][80][81][82]Religious Sites

Nesebar's religious landscape is dominated by its medieval churches, with historical records indicating over 40 such structures built between the 10th and 14th centuries, reflecting the town's role as a key Byzantine and Bulgarian spiritual center.[83][84] These churches, constructed primarily during periods of prosperity under Bulgarian rule and Byzantine influence, served as hubs for worship, education, and artistic expression, commissioned often by wealthy merchants and nobles.[85] Today, while many survive as ruins or have been repurposed, they underscore Nesebar's enduring Christian heritage, with no Ottoman-era mosques remaining intact following the reversion of sites to Orthodox use after Bulgaria's liberation in the late 19th century.[2] The architectural styles of Nesebar's churches evolved from early Byzantine basilicas to more complex Bulgarian variants, including cross-domed and cross-insignia (cross-in-square) plans that adapted Eastern Orthodox liturgical needs.[86] A distinctive feature unique to the Black Sea region is the elaborate ceramic decoration on facades, incorporating colorful glazed disks, rosettes, blind arcades, floral motifs, and geometric patterns like zigzags and fishbones, which blend Byzantine influences with local craftsmanship.[2][32] These elements not only enhanced aesthetic appeal but also symbolized spiritual themes, such as the sun disc representing divine light, contributing to the churches' high artistic value as exemplars of medieval Bulgarian religious art.[34] Prominent examples include the Church of Christ Pantocrator, a 13th-14th century cross-in-square structure renowned for its well-preserved frescoes depicting Christ as the "Ruler of All," saints, and biblical scenes, which highlight the artistic pinnacle of Nesebar's medieval painting tradition.[87][88] Another key site is the Church of St. John the Baptist, dating to the 10th–11th century and featuring a transitional design from basilica to cross-domed form with rough stone construction and a donor portrait from the 14th century, illustrating early architectural experimentation in the region.[89][31] These churches, along with others like St. Paraskevi and St. Theodore, exemplify the diversity of forms, from single-nave basilicas to more elaborate domed layouts.[90] Preservation efforts have focused on stabilizing and restoring select churches, with at least 14 undergoing conservation since the mid-20th century to combat decay from seismic activity, tourism, and weathering; for instance, the Church of St. Paraskevi, a 13th-14th century single-nave basilica, was comprehensively restored in the 2010s and now functions as a museum exhibiting murals salvaged from demolished sites.[91] In contrast, the Church of St. Theodore remains largely in ruins, its 13th-century brickwork and decorative elements visible but unprotected from further erosion.[30] Current religious roles vary: a few, such as the New Bishopric Church, host active Bulgarian Orthodox parishes for contemporary worship, while many others, including the Old Bishopric Basilica integrated into the Archaeological Museum, have been converted into exhibition spaces to safeguard artifacts and educate visitors on Nesebar's ecclesiastical history.[92][93] Nesebar's religious sites contribute significantly to its UNESCO World Heritage status, inscribed in 1983 under criteria (iii) for bearing exceptional testimony to a vanished Christian cultural tradition and (iv) as outstanding examples of medieval religious architecture illustrating Byzantine stylistic impositions on local forms.[2] This recognition emphasizes the churches' role in demonstrating the synthesis of Byzantine influences with Bulgarian innovations, preserving a layered heritage that spans over a millennium of spiritual and artistic development.[94]Festivals and Events

Nessebar hosts a vibrant array of annual festivals and events that celebrate its rich cultural heritage, drawing participants and visitors from Bulgaria and abroad. The International Festival "Nessebar - Island of Arts," held annually in early July at the Zhanna Chimbuleva Amphitheater in the old town, features performances by international ensembles, creative groups, choirs, and dance formations, focusing on vocal and choreographic arts for children and youth. Established in the early 2010s, the event promotes cultural exchange through free public concerts and has grown to include diverse artistic expressions.[95] Orthodox Easter celebrations in Nessebar emphasize traditional religious processions, particularly in the historic churches of the old town. On Holy Saturday evening, believers gather with lighted candles to follow priests in a solemn procession around the churches, reenacting the resurrection narrative and marking the culmination of Lent with midnight services. These events, deeply rooted in the town's Byzantine and Orthodox legacy, foster community unity and attract locals to sites like the Church of Christ Pantocrator.[96] Folklore events form a cornerstone of Nessebar's summer calendar, highlighting Bulgarian customs through dance, music, and rituals. The International Festival "Ancient City," occurring in late August, showcases folk dances and songs from global ensembles, performed against the backdrop of the town's ancient ruins and drawing on Nessebar's UNESCO-recognized intangible cultural ties to Thracian and medieval traditions. Similarly, the International Festival "Folklore Nuances" in late June brings together vocal, dance, and instrumental groups for open-air performances in the old town, emphasizing preserved Bulgarian folk arts.[97][98] Music and arts festivals further enrich the cultural scene, with the Mesembria Orpheus International Chamber Music Festival in September presenting classical performances in medieval venues like the Church of St. John the Baptist. Organized under the patronage of the Nessebar Municipality, it features renowned ensembles playing works by composers such as Bach and Beethoven, linking modern interpretations to the site's ancient Messembrian heritage, which UNESCO associates with broader Bulgarian cultural practices. The Day of Nessebar on August 15, a municipal holiday, combines concerts, sports activities, and a midnight fireworks display, honoring the town's spiritual patron, the Holy Mother of God, and reinforcing local identity through community-organized festivities.[99][100] These events, coordinated by the Nessebar Municipality and local cultural centers, play a vital role in preserving traditions while boosting communal bonds and tying into the town's UNESCO World Heritage status for its historical and cultural continuity. Recent additions, such as the National Fish Festival "Autumn Passages" in late summer, incorporate sustainable themes with artisan markets and seafood tastings, reflecting evolving community priorities.[101][2][70]Sports

Football

Football in Nesebar is primarily represented by OFC Nesebar, a municipal association football club founded in 1946.[102] The club, nicknamed "The Dolphins," competed in the Bulgarian Second Professional Football League, the country's second tier, during the 2024-25 season following promotion from the Third League Southeast Group at the end of the 2023–24 season, but was relegated after finishing 20th. As of November 2025, it competes in the Third League Southeast, currently in 2nd position.[103] OFC Nesebar plays its home matches at Gradski Stadion, a multi-purpose venue with a capacity of 7,000 spectators, built in 1965 and featuring a natural grass pitch measuring 100m x 50m.[104] The club's history includes significant fluctuations between divisions. OFC Nesebar achieved promotion to the Second League ahead of the 2014–15 campaign after a strong performance in the third tier, where it established itself as a competitive side with a focus on local talent development. It maintained its position in the second tier for five seasons, highlighted by a fifth-place finish in 2017–18, before relegation in 2019 due to financial and performance challenges. The team returned to the Second League in 2024 after topping the Third League table, though it had declined promotion after the 2022–23 season for similar financial reasons.[103] OFC Nesebar operates a youth academy that nurtures regional talents, contributing to the development of players who progress to higher levels within Bulgarian football.[103] Notable players emerging from the club's system include Daniel Cabanelas, a 21-year-old left winger born in 2004, who joined OFC Nesebar and has become a key squad member, showcasing versatility in attacking roles.[105] Community support remains strong, with average home attendances around 300 to 500 fans, reflecting the club's role in local recreation and passion for the sport.[106] Facilities at Gradski Stadion received upgrades in the early 2020s to meet league standards, including improvements to seating and infrastructure, enabling the venue to host competitive matches and youth events. The stadium regularly accommodates the annual Vakancia Cup, an international junior football tournament established around 2000, which draws teams from Bulgaria, Romania, Ukraine, and Russia across multiple age groups for sessions in June and August.[107] OFC Nesebar's achievements include multiple regional titles in the Third League era and a 2016 victory in the Cup of the Bulgarian Amateur Football League, underscoring its impact on southeast regional football.[103] In the 2025–26 Third League season, the club has shown strong form, currently holding 2nd position as of November 2025.[108]Other Activities

In addition to organized football, Nessebar offers a variety of recreational and amateur sports, particularly those leveraging its Black Sea coastline and mild climate. Beach volleyball is a prominent activity, with regular tournaments held on the sandy shores adjacent to the town, including in nearby Sunny Beach and Sveti Vlas within the Nessebar municipality. These events, such as the weekly volleyball tournament at Palm Beach Bar and Grill, attract local players and tourists for casual and competitive play, fostering community engagement along the central beach areas.[109][110] Water polo features in recreational settings, often organized through hotel pools and coastal facilities, where participants engage in friendly matches and team games. The National Sports Academy's water sports base near Nessebar supports training in water polo alongside other aquatic disciplines, emphasizing skill development for amateurs.[111][112] Diving centers in Nessebar provide access to Black Sea wrecks, with operators like Nemo Diving Center offering guided excursions to sites off the southern coast, including ancient shipwrecks dating back centuries. These dives, typically at depths of 15-50 meters, cater to certified divers exploring historical underwater artifacts. Sailing regattas add to the aquatic scene, exemplified by the annual Nessebar Cup, which has been held since at least 2018 in the bay, drawing competitors in classes like Optimist and Laser. More recently, the 53rd Balkan Sailing Championship in October 2025 hosted 110 yachts from six countries, highlighting the town's growing role in regional maritime events.[113][114][115][116][117] On land, athletics enthusiasts utilize running and cycling paths in the New Town area and along the coast. Seafront promenades, such as the 3 km waterfront route encircling Old Nessebar, serve as popular tracks for jogging, while the Black Sea Epic Route includes dedicated cycling paths connecting Nessebar to neighboring resorts like Sveti Vlas, spanning over 13 km one way with scenic coastal views. Fishing competitions occur during seasonal festivals, notably the Autumn Passages event, where local crews compete in preparing traditional fish soups and specialties using fresh Black Sea catches from the town's port.[118][119][120][121] Community programs support broader participation through municipal facilities and youth initiatives. Outdoor gyms and calisthenics parks in Nessebar provide free access for strength training and bodyweight exercises, complementing indoor fitness options in the New Town. Youth sports camps, established in the 2010s and expanded into the 2020s, offer summer programs focused on water sports, volleyball, and team activities; for instance, adapted camps at the Nessebar water sports base since 2020 include sailing, kayaking, and swimming for young participants with diverse abilities. Nationally, about 56% of Bulgarian youth engage in organized sports outside school, though local participation remains modest due to the town's tourism emphasis.[122][123][124][125][126] In the 2020s, eco-tourism has integrated with recreational activities, particularly birdwatching tours departing from Nessebar to nearby wetlands and oak forests. These excursions highlight species like pelicans and birds of prey along the southern Black Sea coast, combining observation with light hiking and nature education to promote sustainable engagement.[127][128]Namesakes

Geographical Namesakes

Several geographical locations worldwide share names or etymological similarities with Nesebar, primarily stemming from ancient Thracian and Greek origins associated with the name "Mesembria," derived from the Thracian "Menebria" or "Melsambria," meaning the "city of Melsas," a legendary Thracian leader. These namesakes are typically minor features or historical sites.[2] In Bulgaria, the Nesebar Peninsula serves as the immediate geographical namesake, forming the rocky headland on which the ancient town of Nesebar is situated, approximately 850 meters long by 350 meters wide and originally an island connected by a narrow isthmus. This feature has been integral to the site's UNESCO World Heritage status since 1983, highlighting its role in the town's defensive and cultural history from Thracian times onward.[2][129] Further afield in Antarctica, Nesebar Gap is a 1.3 km wide glacial pass at 550 m elevation in eastern Livingston Island, South Shetland Islands, separating Pliska Ridge from the northern slopes of Mount Friesland. Named after the Bulgarian town of Nesebar by the Bulgarian Antarctic Place-names Commission in 1998, it reflects Bulgaria's contributions to Antarctic toponymy amid its scientific research presence since the 1960s.[130] In Greece, the ancient city of Mesambria (also spelled Mesembria) on the Aegean Sea coast in western Thrace represents an independent but etymologically related settlement. Founded by colonists from Samothrace around the 6th century BCE, it was a Dorian Greek outpost mentioned by Herodotus for its role in Xerxes' 480 BCE campaign, with archaeological remains indicating a distinct Thracian-influenced site separate from the Black Sea Mesembria. Its exact location remains tentatively identified in the Thracian Chersonese region, though uncertain.[131]Cultural References

Nesebar's picturesque setting and rich historical tapestry have inspired various artistic representations, particularly in painting. Local and contemporary Bulgarian artists have frequently captured its seascapes and ancient architecture, as seen in impressionist oil works by Lena Kurovska depicting the old town's coastal views painted en plein air. Similarly, artist D. Stoykova's original oil paintings portray morning scenes in Nesebar's historic quarter, emphasizing its enduring charm.[132][133] In cinema, Nesebar has served as a subject for Bulgarian productions. A 1957 short documentary titled Nesebar chronicles the town's 2,500-year history from its Thracian origins to the mid-20th century. More recently, the 2024 Bulgarian National Television documentary The Spiritual Mirror of Christian Nessebar explores its Byzantine religious heritage and earned four international awards.[134][135] Nesebar's cultural legacy extends to digital media in the 2020s, where virtual reality tools have democratized access to its heritage. The 2021 mobile application VR Nessebar, developed by ICTC Burgas, provides immersive 3D augmented reality tours of 50 key sites, including ancient churches and fortifications, allowing users to experience the town's layered history remotely.[136] While Nesebar has produced no globally renowned natives, local figures like archaeologist Prof. Kazimir Popkonstantinov have contributed significantly to its scholarly recognition through public lectures on its Christian archaeology.[137]References

- https://en.wikivoyage.org/wiki/Nesebar