Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Nucleon

View on Wikipedia

In physics and chemistry, a nucleon is either a proton or a neutron, considered in its role as a component of an atomic nucleus. The number of nucleons in a nucleus defines the atom's mass number.

Until the 1960s, nucleons were thought to be elementary particles, not made up of smaller parts. Now they are understood as composite particles, made of three quarks bound together by the strong interaction. The interaction between two or more nucleons is called internucleon interaction or nuclear force, which is also ultimately caused by the strong interaction. (Before the discovery of quarks, the term "strong interaction" referred to just internucleon interactions.)

Nucleons sit at the boundary where particle physics and nuclear physics overlap. Particle physics, particularly quantum chromodynamics, provides the fundamental equations that describe the properties of quarks and of the strong interaction. These equations describe quantitatively how quarks can bind together into protons and neutrons (and all the other hadrons). However, when multiple nucleons are assembled into an atomic nucleus (nuclide), these fundamental equations become too difficult to solve directly (see lattice QCD). Instead, nuclides are studied within nuclear physics, which studies nucleons and their interactions by approximations and models, such as the nuclear shell model. These models can successfully describe nuclide properties, as for example, whether or not a particular nuclide undergoes radioactive decay.

The proton and neutron are in a scheme of categories being at once fermions, hadrons and baryons. The proton carries a positive net charge, and the neutron carries a zero net charge; the proton's mass is only about 0.13% less than the neutron's. Thus, they can be viewed as two states of the same nucleon, and together form an isospin doublet (I = 1/2). In isospin space, neutrons can be transformed into protons and conversely by SU(2) symmetries. These nucleons are acted upon equally by the strong interaction, which is invariant under rotation in isospin space. According to Noether's theorem, isospin is conserved with respect to the strong interaction.[1]: 129–130

Overview

[edit]Properties

[edit]Protons and neutrons are best known in their role as nucleons, i.e., as the components of atomic nuclei, but they also exist as free particles. Free neutrons are unstable, with a half-life of around 13 minutes, but they have important applications (see neutron radiation and neutron scattering). Protons not bound to other nucleons are the nuclei of hydrogen atoms when bound with an electron or – if not bound to anything – are ions or cosmic rays.

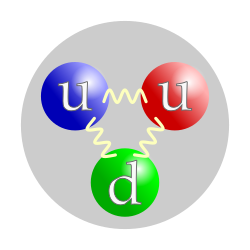

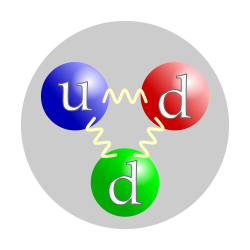

Both the proton and the neutron are composite particles, meaning that each is composed of smaller parts, namely three quarks each; although once thought to be so, neither is an elementary particle. A proton is composed of two up quarks and one down quark, while the neutron has one up quark and two down quarks. Quarks are held together by the strong force, or equivalently, by gluons, which mediate the strong force at the quark level.

An up quark has electric charge ++2/3 e, and a down quark has charge −+1/3 e, so the summed electric charges of proton and neutron are +e and 0, respectively.[a] Thus, the neutron has a charge of 0 (zero), and therefore is electrically neutral; indeed, the term "neutron" comes from the fact that a neutron is electrically neutral.

The masses of the proton and neutron are similar: for the proton it is 1.6726×10−27 kg (938.27 MeV/c2), while for the neutron it is 1.6749×10−27 kg (939.57 MeV/c2); the neutron is roughly 0.13% heavier. The similarity in mass can be explained roughly by the slight difference in masses of up quarks and down quarks composing the nucleons. However, a detailed description remains an unsolved problem in particle physics.[1]: 135–136

The spin of the nucleon is 1/2, which means that they are fermions and, like electrons, are subject to the Pauli exclusion principle: no more than one nucleon, e.g. in an atomic nucleus, may occupy the same quantum state.

The isospin and spin quantum numbers of the nucleon have two states each, resulting in four combinations in total. An alpha particle is composed of four nucleons occupying all four combinations, namely, it has two protons (having opposite spin) and two neutrons (also having opposite spin), and its net nuclear spin is zero. In larger nuclei constituent nucleons, by Pauli exclusion, are compelled to have relative motion, which may also contribute to nuclear spin via the orbital quantum number. They spread out into nuclear shells analogous to electron shells known from chemistry.

Both the proton and neutron have magnetic moments, though the nucleon magnetic moments are anomalous and were unexpected when they were discovered in the 1930s. The proton's magnetic moment, symbol μp, is 2.79 μN, whereas, if the proton were an elementary Dirac particle, it should have a magnetic moment of 1.0 μN. Here the unit for the magnetic moments is the nuclear magneton, symbol μN, an atomic-scale unit of measure. The neutron's magnetic moment is μn = −1.91 μN, whereas, since the neutron lacks an electric charge, it should have no magnetic moment. The value of the neutron's magnetic moment is negative because the direction of the moment is opposite to the neutron's spin. The nucleon magnetic moments arise from the quark substructure of the nucleons.[2][3] The proton magnetic moment is exploited for NMR / MRI scanning.

Stability

[edit]A neutron in free state is an unstable particle, with a half-life around ten minutes.[PDG 1] It undergoes β−

decay (a type of radioactive decay) by turning into a proton while emitting an electron and an electron antineutrino. This reaction can occur because the mass of the neutron is slightly greater than that of the proton (see neutron decay). In the Standard Model of particle physics, an isolated proton is predicted to be stable[4]: 4 More speculative models like a grand unified theory predict protons should be unstable.[5]: 2 This has led to experiments like Super-Kamiokande in Japan which attempt to measure proton decay. The failure to detect such decay has placed the lifetime of the proton above 1034 years.[6]

Inside a nucleus, on the other hand, combined protons and neutrons (nucleons) can be stable or unstable depending on the nuclide, or nuclear species.[7] Inside some nuclides, a neutron can turn into a proton (producing other particles) as described above; the reverse can happen inside other nuclides, where a proton turns into a neutron (producing other particles) through β+

decay or electron capture. And inside still other nuclides, both protons and neutrons are stable and do not change form.

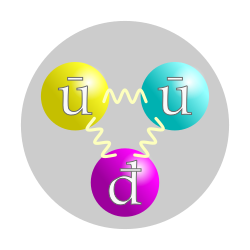

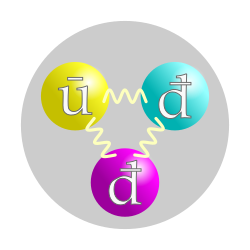

Antinucleons

[edit]Both nucleons have corresponding antiparticles: the antiproton and the antineutron, which have the same mass and opposite charge as the proton and neutron respectively, and they interact in the same way. (This is generally believed to be exactly true, due to CPT symmetry. If there is a difference, it is too small to measure in all experiments to date.) In particular, antinucleons can bind into an "antinucleus". So far, scientists have created antideuterium[8][9] and antihelium-3[10] nuclei.

Tables of detailed properties

[edit]Nucleons

[edit]| Particle name |

Symbol | Quark content |

Mass[a] | I3 | JP | Q | Magnetic moment [μN] | Mean lifetime | Commonly decays to |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| proton[PDG 2] | p / p+ / N+ |

uud | 938.272013(23) MeV/c2 1.00727646677(10) Da |

+1/2 | 1/2+ | +1 e | 2.792847356(23) | stable[b] | unobserved |

| neutron[PDG 1] | n / n0 / N0 |

udd | 939.565346(23) MeV/c2 1.00866491597(43) Da |

−+1/2 | 1/2+ | 0 e | −1.91304273(45) | 885.7(8) s[c] | p + e− + ν e |

| antiproton | p / p− / N− |

uud | 938.272013(23) MeV/c2 1.00727646677(10) Da |

−+1/2 | 1/2+ | −1 e | −2.793(6) | stable[b] | unobserved |

| antineutron | n / n0 / N0 |

udd | 939.485(51) MeV/c2 1.00866491597(43) Da |

++1/2 | 1/2+ | 0 e | ? | 885.7(8) s[c] | p + e+ + ν e |

^a The masses of the proton and neutron are known with far greater precision in daltons (Da) than in MeV/c2 due to the way in which these are defined. The conversion factor used is 1 Da = 931.494028(23) MeV/c2.

^b At least 1035 years. See proton decay.

^c For free neutrons; in most common nuclei, neutrons are stable.

The masses of their antiparticles are assumed to be identical, and no experiments have refuted this to date. Current experiments show any relative difference between the masses of the proton and antiproton must be less than 2×10−9[PDG 2] and the difference between the neutron and antineutron masses is on the order of (9±6)×10−5 MeV/c2.[PDG 1]

| Test | Formula | PDG result[PDG 2] |

|---|---|---|

| Mass | < 2×10−9 | |

| Charge-to-mass ratio | 0.99999999991(9) | |

| Charge-to-mass-to-mass ratio | (−9±9)×10−11 | |

| Charge | < 2×10−9 | |

| Electron charge | < 1×10−21 | |

| Magnetic moment | (−0.1±2.1)×10−3 |

Nucleon resonances

[edit]Nucleon resonances are excited states of nucleon particles, often corresponding to one of the quarks having a flipped spin state, or with different orbital angular momentum when the particle decays. Only resonances with a 3- or 4-star rating at the Particle Data Group (PDG) are included in this table. Due to their extraordinarily short lifetimes, many properties of these particles are still under investigation.

The symbol format is given as N(m) LIJ, where m is the particle's approximate mass, L is the orbital angular momentum (in the spectroscopic notation) of the nucleon–meson pair, produced when it decays, and I and J are the particle's isospin and total angular momentum respectively. Since nucleons are defined as having 1/2 isospin, the first number will always be 1, and the second number will always be odd. When discussing nucleon resonances, sometimes the N is omitted and the order is reversed, in the form LIJ (m); for example, a proton can be denoted as "N(939) S11" or "S11 (939)".

The table below lists only the base resonance; each individual entry represents 4 baryons: 2 nucleon resonances particles and their 2 antiparticles. Each resonance exists in a form with a positive electric charge (Q), with a quark composition of uud like the proton, and a neutral form, with a quark composition of udd like the neutron, as well as the corresponding antiparticles with antiquark compositions of uud and udd respectively. Since they contain no strange, charm, bottom, or top quarks, these particles do not possess strangeness, etc.

The table only lists the resonances with an isospin = 1/2. For resonances with isospin = 3/2, see the article on Delta baryons.

| Symbol | JP | PDG mass average (MeV/c2) |

Full width (MeV/c2) |

Pole position (real part) |

Pole position (−2 × imaginary part) |

Common decays (Γi/Γ > 50%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N(939) P11 [PDG 3]† |

1/2+ | 939 | † | † | † | † |

| N(1440) P11 [PDG 4] (the Roper resonance) |

1/2+ | 1440 (1420–1470) |

300 (200–450) |

1365 (1350–1380) |

190 (160–220) |

N + π |

| N(1520) D13 [PDG 5] |

3/2− | 1520 (1515–1525) |

115 (100–125) |

1510 (1505–1515) |

110 (105–120) |

N + π |

| N(1535) S11 [PDG 6] |

1/2− | 1535 (1525–1545) |

150 (125–175) |

1510 (1490–1530) |

170 (90–250) |

N + π or N + η |

| N(1650) S11 [PDG 7] |

1/2− | 1650 (1645–1670) |

165 (145–185) |

1665 (1640–1670) |

165 (150–180) |

N + π |

| N(1675) D15 [PDG 8] |

5/2− | 1675 (1670–1680) |

150 (135–165) |

1660 (1655–1665) |

135 (125–150) |

N + π + π or Δ + π |

| N(1680) F15 [PDG 9] |

5/2+ | 1685 (1680–1690) |

130 (120–140) |

1675 (1665–1680) |

120 (110–135) |

N + π |

| N(1700) D13 [PDG 10] |

3/2− | 1700 (1650–1750) |

100 (50–150) |

1680 (1630–1730) |

100 (50–150) |

N + π + π |

| N(1710) P11 [PDG 11] |

1/2+ | 1710 (1680–1740) |

100 (50–250) |

1720 (1670–1770) |

230 (80–380) |

N + π + π |

| N(1720) P13 [PDG 12] |

3/2+ | 1720 (1700–1750) |

200 (150–300) |

1675 (1660–1690) |

115–275 | N + π + π or N + ρ |

| N(2190) G17 [PDG 13] |

7/2− | 2190 (2100–2200) |

500 (300–700) |

2075 (2050–2100) |

450 (400–520) |

N + π (10—20%) |

| N(2220) H19 [PDG 14] |

9/2+ | 2250 (2200–2300) |

400 (350–500) |

2170 (2130–2200) |

480 (400–560) |

N + π (10—20%) |

| N(2250) G19 [PDG 15] |

9/2− | 2250 (2200–2350) |

500 (230–800) |

2200 (2150–2250) |

450 (350–550) |

N + π (5—15%) |

† The P11(939) nucleon represents the excited state of a normal proton or neutron. Such a particle may be stable when in an atomic nucleus, e.g. in lithium-6.[11]

Quark model classification

[edit]In the quark model with SU(2) flavour, the two nucleons are part of the ground-state doublet. The proton has quark content of uud, and the neutron, udd. In SU(3) flavour, they are part of the ground-state octet (8) of spin-1/2 baryons, known as the Eightfold way. The other members of this octet are the hyperons strange isotriplet Σ+

, Σ0

, Σ−

, the Λ and the strange isodoublet Ξ0

, Ξ−

. One can extend this multiplet in SU(4) flavour (with the inclusion of the charm quark) to the ground-state 20-plet, or to SU(6) flavour (with the inclusion of the top and bottom quarks) to the ground-state 56-plet.

The article on isospin provides an explicit expression for the nucleon wave functions in terms of the quark flavour eigenstates.

Models

[edit]This section may be confusing or unclear to readers. (August 2007) |

Although it is known that the nucleon is made from three quarks, as of 2006[update], it is not known how to solve the equations of motion for quantum chromodynamics. Thus, the study of the low-energy properties of the nucleon are performed by means of models. The only first-principles approach available is to attempt to solve the equations of QCD numerically, using lattice QCD. This requires complicated algorithms and very powerful supercomputers. However, several analytic models also exist:

Skyrmion models

[edit]The skyrmion models the nucleon as a topological soliton in a nonlinear SU(2) pion field. The topological stability of the skyrmion is interpreted as the conservation of baryon number, that is, the non-decay of the nucleon. The local topological winding number density is identified with the local baryon number density of the nucleon. With the pion isospin vector field oriented in the shape of a hedgehog space, the model is readily solvable, and is thus sometimes called the hedgehog model. The hedgehog model is able to predict low-energy parameters, such as the nucleon mass, radius and axial coupling constant, to approximately 30% of experimental values.

MIT bag model

[edit]The MIT bag model[12][13][14] confines quarks and gluons interacting through quantum chromodynamics to a region of space determined by balancing the pressure exerted by the quarks and gluons against a hypothetical pressure exerted by the vacuum on all colored quantum fields. The simplest approximation to the model confines three non-interacting quarks to a spherical cavity, with the boundary condition that the quark vector current vanish on the boundary. The non-interacting treatment of the quarks is justified by appealing to the idea of asymptotic freedom, whereas the hard-boundary condition is justified by quark confinement.

Mathematically, the model vaguely resembles that of a radar cavity, with solutions to the Dirac equation standing in for solutions to the Maxwell equations, and the vanishing vector current boundary condition standing for the conducting metal walls of the radar cavity. If the radius of the bag is set to the radius of the nucleon, the bag model predicts a nucleon mass that is within 30% of the actual mass.

Although the basic bag model does not provide a pion-mediated interaction, it describes excellently the nucleon–nucleon forces through the 6 quark bag s-channel mechanism using the P-matrix.[15][16]

Chiral bag model

[edit]The chiral bag model[17][18] merges the MIT bag model and the skyrmion model. In this model, a hole is punched out of the middle of the skyrmion and replaced with a bag model. The boundary condition is provided by the requirement of continuity of the axial vector current across the bag boundary.

Very curiously, the missing part of the topological winding number (the baryon number) of the hole punched into the skyrmion is exactly made up by the non-zero vacuum expectation value (or spectral asymmetry) of the quark fields inside the bag. As of 2017[update], this remarkable trade-off between topology and the spectrum of an operator does not have any grounding or explanation in the mathematical theory of Hilbert spaces and their relationship to geometry.

Several other properties of the chiral bag are notable: It provides a better fit to the low-energy nucleon properties, to within 5–10%, and these are almost completely independent of the chiral-bag radius, as long as the radius is less than the nucleon radius. This independence of radius is referred to as the Cheshire Cat principle,[19] after the fading of Lewis Carroll's Cheshire Cat to just its smile. It is expected that a first-principles solution of the equations of QCD will demonstrate a similar duality of quark–meson descriptions.

See also

[edit]Footnotes

[edit]- ^ The resultant coefficients are obtained by summation of the component charges: ΣQ = 2/3 + 2/3 + (−+1/3) = 3/3 = +1 for proton, and ΣQ = 2/3 + (−+1/3) + (−+1/3) = 0/3 = 0 for neutron.

References

[edit]- ^ a b Griffiths, David J. (2008). Introduction to Elementary Particles (2nd revised ed.). WILEY-VCH. ISBN 978-3-527-40601-2.

- ^ Perkins, Donald H. (1982). Introduction to High Energy Physics. Reading, Massachusetts: Addison Wesley. pp. 201–202. ISBN 978-0-201-05757-7.

- ^ Kincade, Kathy (2 February 2015). "Pinpointing the magnetic moments of nuclear matter". Phys.org. Archived from the original on 2 May 2015. Retrieved May 8, 2015.

- ^ Cottingham, William N.; Greenwood, Derek A. (2007). An introduction to the standard model of particle physics (2 ed.). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-009-40172-2.

- ^ Thomas, Anthony William; Weise, Wolfram (2005). The structure of the nucleon. Berlin: Wiley-VCH. ISBN 978-3-527-60314-5.

- ^ Mine, Shunichi (January 11, 2024). Nucleon decay: theory and experimental overview. 22nd International Workshop on Next Generation Nucleon Decay and Neutrino Detectors. doi:10.5281/ZENODO.10493165.

- ^ "Livechart - Table of Nuclides - Nuclear structure and decay data". International Atomic Energy Agency.

- ^ Massam, T; Muller, Th.; Righini, B.; Schneegans, M.; Zichichi, A. (1965). "Experimental observation of antideuteron production". Il Nuovo Cimento. 39 (1): 10–14. Bibcode:1965NCimS..39...10M. doi:10.1007/BF02814251. S2CID 122952224.

- ^ Dorfan, D. E; Eades, J.; Lederman, L. M.; Lee, W.; Ting, C. C. (June 1965). "Observation of Antideuterons". Physical Review Letters. 14 (24): 1003–1006. Bibcode:1965PhRvL..14.1003D. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.14.1003.

- ^ R. Arsenescu; et al. (2003). "Antihelium-3 production in lead-lead collisions at 158 A GeV/c". New Journal of Physics. 5 (1): 1. Bibcode:2003NJPh....5....1A. doi:10.1088/1367-2630/5/1/301.

- ^ "Lithium-6. Compound summary". PubChem. National Library of Medicine. Archived from the original on 2021-11-19. Retrieved 2021-04-08.

- ^ Chodos, A.; Jaffe, R. L.; Johnson, K.; Thorn, C. B.; Weisskopf, V. F. (1974). "New extended model of hadrons". Physical Review D. 9 (12): 3471–3495. Bibcode:1974PhRvD...9.3471C. doi:10.1103/PhysRevD.9.3471.

- ^ Chodos, A.; Jaffe, R. L.; Johnson, K.; Thorn, C. B. (1974). "Baryon structure in the bag theory". Physical Review D. 10 (8): 2599–2604. Bibcode:1974PhRvD..10.2599C. doi:10.1103/PhysRevD.10.2599.

- ^ Degrand, T.; Jaffe, R. L.; Johnson, K.; Kiskis, J. (1975). "Masses and other parameters of the light hadrons". Physical Review D. 12 (7): 2060–2076. Bibcode:1975PhRvD..12.2060D. doi:10.1103/PhysRevD.12.2060.

- ^ Jaffe, R. L.; Low, F. E. (1979). "Connection between quark-model eigenstates and low-energy scattering". Physical Review D. 19 (7): 2105. Bibcode:1979PhRvD..19.2105J. doi:10.1103/PhysRevD.19.2105.

- ^ Yu; Simonov, A. (1981). "The quark compound bag model and the Jaffe-Low P-matrix". Physics Letters B. 107 (1–2): 1. Bibcode:1981PhLB..107....1S. doi:10.1016/0370-2693(81)91133-3.

- ^ Brown, Gerald E.; Rho, Mannque (March 1979). "The little bag". Physics Letters B. 82 (2): 177–180. Bibcode:1979PhLB...82..177B. doi:10.1016/0370-2693(79)90729-9.

- ^ Vepstas, L.; Jackson, A. D.; Goldhaber, A. S. (1984). "Two-phase models of baryons and the chiral Casimir effect". Physics Letters B. 140 (5–6): 280–284. Bibcode:1984PhLB..140..280V. doi:10.1016/0370-2693(84)90753-6.

- ^ Vepstas, L.; Jackson, A. D. (1990). "Justifying the chiral bag". Physics Reports. 187 (3): 109–143. Bibcode:1990PhR...187..109V. doi:10.1016/0370-1573(90)90056-8.

Particle listings

[edit]- ^ a b c Particle listings – n Archived 2018-10-03 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ a b c Particle listings – p Archived 2017-01-27 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ Particle listings — Note on N and Delta Resonances Archived 2021-03-27 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ Particle listings — N(1440) Archived 2021-03-30 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ Particle listings — N(1520) Archived 2021-03-29 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ Particle listings — N(1535) Archived 2021-03-29 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ Particle listings — N(1650) Archived 2021-03-30 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ Particle listings — N(1675) Archived 2021-03-28 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ Particle listings — N(1680) Archived 2021-03-29 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ Particle listings — N(1700) Archived 2021-03-28 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ Particle listings — N(1710) Archived 2021-03-28 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ Particle listings — N(1720) Archived 2021-03-30 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ Particle listings — N(2190) Archived 2021-03-29 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ Particle listings — N(2220) Archived 2021-03-29 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ Particle listings — N(2250) Archived 2021-03-29 at the Wayback Machine.

Further reading

[edit]- Thomas, A. W.; Weise, W. (2001). The Structure of the Nucleon. Berlin, DE: Wiley-WCH. ISBN 3-527-40297-7.

- Brown, G .E.; Jackson, A. D. (1976). The Nucleon–Nucleon Interaction. North-Holland Publishing. ISBN 978-0-7204-0335-0.

- Nakamura, N.; Particle Data Group; et al. (2011). "Review of Particle Physics". Journal of Physics G. 37 (7) 075021. Bibcode:2010JPhG...37g5021N. doi:10.1088/0954-3899/37/7A/075021. hdl:10481/34593.

Nucleon

View on GrokipediaDefinition and Historical Context

Definition as Baryons

Nucleons are the collective term for protons and neutrons, which are classified as spin-1/2 baryons possessing the lowest masses among all known baryons.[6] These particles serve as the fundamental constituents of atomic nuclei, binding together through the strong nuclear force to form the dense cores of atoms.[7] As fermions with half-integer spin, nucleons obey the Pauli exclusion principle, enabling the structured arrangement within nuclei that underpins the stability of ordinary matter.[6] In the broader context of particle physics, hadrons encompass two main categories: mesons, composed of a quark-antiquark pair, and baryons, made up of three quarks. Nucleons fall into the baryon category and represent the stable ground-state configurations due to their minimal energy and lack of lighter decay products under strong and electromagnetic interactions.[8] Protons are indefinitely stable, while free neutrons decay via the weak interaction with a mean lifetime of approximately 880 seconds, though they remain stable within bound nuclear systems.[7] This stability positions nucleons as the primary carriers of baryon number in the universe, with all heavier baryons eventually decaying into them.[7] Nucleons account for over 99.95% of the mass of ordinary matter, primarily through their role in atomic nuclei, where the negligible mass of electrons contributes less than 0.05%.[9] Within the quark model, they consist of combinations of up and down quarks, distinguishing them from other baryons that incorporate heavier strange quarks or beyond.[8] Under the SU(3) flavor symmetry, which extends the isospin SU(2) group to include strangeness, nucleons occupy the baryon octet representation for spin-1/2 particles, defined by the quantum numbers isospin , hypercharge , and strangeness .[7] This classification highlights their position as the lightest, non-strange members of the octet, separate from the spin-3/2 baryon decuplet.[7]Discovery and Naming

The evolution of atomic theory in the late 19th and early 20th centuries laid the groundwork for the concept of nucleons as the building blocks of the atomic nucleus. J.J. Thomson's plum pudding model, proposed in 1904, depicted the atom as a uniform sphere of positive charge with embedded electrons to maintain neutrality, but this view was challenged by experimental evidence. In 1911, Ernest Rutherford's gold foil experiment, conducted by Hans Geiger and Ernest Marsden, demonstrated that alpha particles scattered at large angles from thin gold foil, indicating a tiny, dense, positively charged nucleus at the atom's center—thus establishing the nuclear model of the atom.[10] In 1886, Eugen Goldstein observed "canal rays" in gas discharge tubes, which consisted of positively charged particles (positive ions, including protons from hydrogen gas) moving in the opposite direction to cathode rays. However, the proton as the positively charged component of the nucleus was identified later. In 1919, Francis Aston used his newly developed mass spectrograph to measure the mass of the hydrogen ion (H⁺), finding it to be approximately 1 atomic mass unit, distinct from electrons or other known particles. Rutherford confirmed the proton's fundamental nature between 1917 and 1920 by bombarding nitrogen gas with alpha particles, observing the ejection of hydrogen nuclei (protons) from the collisions, and formally named the particle "proton" in 1920, deriving the term from the Greek word for "first" to signify its primacy in the nucleus.[11][12] Rutherford anticipated the need for a neutral counterpart to the proton in 1920, predicting in his Bakerian Lecture a neutral particle of similar mass to explain atomic masses and isotopes without violating charge balance in the nucleus. This prediction was realized in 1932 by James Chadwick at the Cavendish Laboratory, who irradiated beryllium with alpha particles from a polonium source, producing an uncharged radiation capable of ejecting protons from paraffin wax with energies up to 5.7 MeV—consistent with a massive neutral particle rather than gamma rays, as initially misinterpreted by Irène and Frédéric Joliot-Curie. Chadwick's experiments, detailed in his February 1932 paper, confirmed the neutron's existence and mass as roughly equal to the proton's, revolutionizing understanding of nuclear structure.[13][14] The collective term "nucleon" for protons and neutrons was introduced by Christian Møller in 1941 in a short communication on nuclear particle nomenclature, emphasizing their shared role as the massive constituents bound within the atomic nucleus to account for its stability and mass.[15] This naming convention facilitated theoretical discussions in nuclear physics, particularly as models of nuclear forces and binding emerged in the 1930s and 1940s.Fundamental Properties

Mass, Charge, and Spin

The proton and neutron, collectively known as nucleons, are the fundamental constituents of atomic nuclei and share several key properties while differing in specifics. Both have a rest mass on the order of 938 MeV/c², an electric charge that is either +1 or 0 in units of the elementary charge e, and an intrinsic spin of 1/2 in units of ħ. These attributes make nucleons baryons with fermionic statistics, essential for understanding nuclear stability and interactions.[16][17] The proton carries a positive electric charge of +1 e (where e ≈ 1.602 × 10⁻¹⁹ C) and has a precisely measured mass of 938.272 088 16(29) MeV/c². In contrast, the neutron is electrically neutral, with a charge of 0, and a slightly larger mass of 939.565 420 52(54) MeV/c². This mass difference, δm = mₙ - mₚ = 1.293 332 36(63) MeV, primarily stems from the mass difference between the down and up quarks (m_d > m_u) and electromagnetic self-energy effects, with the electromagnetic contribution (increasing the proton mass) calculated to be around -0.76 MeV to δm in QCD frameworks.[16][17][18] Both nucleons possess an intrinsic angular momentum, or spin, of S = 1/2 ħ, which arises from the vector sum of their constituent quarks' spins and orbital contributions. This half-integer spin classifies them as fermions, subject to the Pauli exclusion principle, preventing multiple nucleons from occupying the same quantum state in nuclei and thus enabling the shell structure of atomic nuclei. The spin also gives rise to associated magnetic moments, though these are anomalous compared to Dirac predictions.[16][17] In the context of the strong nuclear force, protons and neutrons exhibit approximate isospin symmetry, forming an isospin doublet with total isospin quantum number I = 1/2. The proton corresponds to the I₃ = +1/2 state, while the neutron is the I₃ = -1/2 state, treating them as two charge states of a single "nucleon" entity under SU(2) isospin transformations; this symmetry explains their similar masses and strong interaction behaviors despite differing charges.[16][17]Isospin and Parity

The isospin formalism treats the proton and neutron as the two charge states of a single particle, the nucleon, forming an isospin doublet with total isospin quantum number , where the proton has third component and the neutron has . This concept was introduced by Werner Heisenberg in 1932 to explain the observed similarities in nuclear interactions despite the electromagnetic differences between protons and neutrons. The strong nuclear force is approximately invariant under continuous SU(2) isospin transformations, which rotate between these states, implying charge independence of the force. Nucleons possess positive intrinsic parity , a quantum number reflecting the behavior of their wave functions under spatial inversion. This parity is conserved in strong and electromagnetic interactions but maximally violated in weak interactions, as established by experiments such as the Wu parity violation in cobalt-60 beta decay. Both the proton and neutron share this value, consistent with their role as ground-state baryons. The complete set of relevant quantum numbers for nucleons includes baryon number , strangeness , and total angular momentum with parity . These distinguish nucleons from other baryons, such as the hyperon with and , highlighting the absence of strange quark content in the nucleon's valence structure. In the quark model, the isospin doublet arises from combinations of up and down quarks, each with .[19][19] Experimental support for isospin symmetry comes from the charge independence of nuclear forces, demonstrated by the near-equality of neutron-neutron, proton-proton (after Coulomb correction), and neutron-proton scattering cross-sections at low energies, such as below 10 MeV, where differences are less than 1%. This equality holds to within a few percent in total cross-sections, confirming the SU(2) invariance of the strong interaction at these energies.Electromagnetic Characteristics

Magnetic Dipole Moment

The magnetic dipole moment of a spin-1/2 particle arises from its intrinsic spin and is given by the Dirac equation prediction , where is the particle's charge, is the reduced Planck's constant, and is its mass. For nucleons, this is expressed in units of the nuclear magneton , where is the proton mass, yielding a Dirac moment of for the proton (with spin ) and for the neutral neutron.[19] The measured proton magnetic moment deviates significantly from this prediction, with (as of 2024), corresponding to a Landé g-factor and an anomalous moment . This value is determined precisely through nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectroscopy in atomic hydrogen and water, where the gyromagnetic ratio (with nuclear spin ) is extracted from Larmor precession frequencies in known magnetic fields, corrected for diamagnetic shielding. In contrast, the neutron's magnetic moment is (as of 2024), a non-zero result despite its vanishing charge, highlighting the role of internal structure. Neutron measurements employ separated-oscillatory-field magnetic resonance on slow neutron beams, comparing precession frequencies with protons in the same field to isolate .[16][17] These anomalous moments originate theoretically from quantum chromodynamics (QCD), where the nucleon's magnetic dipole moment emerges as the sum of constituent quark magnetic moments and orbital angular momentum contributions within the proton (uud) and neutron (udd) valence quark configurations.[19] In the non-relativistic quark model, the proton moment is approximated as , with quark moments ( and being the quark charge and mass), plus relativistic and configuration-mixing corrections that improve agreement with experiment. The neutron's negative moment similarly arises from the opposing contributions of its d and u quarks, underscoring the vector nature of quark currents in generating the overall dipole. Recent lattice QCD calculations confirm these values within uncertainties.[19][20]Electric and Magnetic Form Factors

The electric and magnetic form factors of the nucleon characterize its electromagnetic structure as a function of the four-momentum transfer squared , providing insight into the spatial distribution of charge and magnetization. These are typically parameterized using the Sachs form factors for the electric component and for the magnetic component, which are linear combinations of the underlying Dirac () and Pauli () form factors: and , where and is the nucleon mass. At , and for the proton (with nuclear magnetons as of 2024), while and for the neutron ().[16][17] In elastic electron-proton scattering, the differential cross section is described by the Rosenbluth formula: where is the Mott cross section, is the electron scattering angle, and the form factors are separated by varying at fixed . For the proton, at low , is well approximated by the dipole form , which yields a mean-square charge radius (corresponding to a root-mean-square radius of approximately 0.81 fm); the measured value is (rms radius 0.841 fm as of 2024).[16] The magnetic form factor follows a similar dipole behavior at low , scaled by . For the neutron, the electric form factor is small, with at low , reflecting its zero net charge, though measurements reveal a negative mean-square electric radius (as of 2024), indicating a charge distribution with negative core and positive periphery.[17] The neutron magnetic form factor is related to its anomalous magnetic moment , decreasing roughly as a dipole form at low to moderate . These form factors are extracted experimentally through elastic electron-nucleon scattering, pioneered at SLAC in the 1960s for high- coverage up to several GeV², and refined at Jefferson Lab (JLab) with higher precision using large-acceptance spectrometers. More recent polarization transfer methods, involving longitudinally polarized electrons and recoil proton polarimetry, have revealed that the ratio decreases with increasing (from near unity at low to about 0.4 at ), challenging earlier Rosenbluth separations and indicating contributions from two-photon exchange or non-pointlike structure. For the neutron, form factors are inferred from quasi-elastic scattering off deuterium targets or polarization asymmetries in polarized electron-deuteron scattering.[21] In perturbative quantum chromodynamics (pQCD), the asymptotic behavior of the Sachs form factors at large is predicted to follow , arising from the hard scattering of quarks with minimal gluon exchanges in the nucleon's wave function, with the proton-to-neutron ratio approaching unity due to flavor symmetry. This falloff has been observed to emerge around in JLab data, though deviations at intermediate scales highlight the role of non-perturbative effects. Recent lattice QCD simulations as of 2024 confirm the low- form factors and radii within experimental uncertainties.[22][20]Internal Structure

Valence Quark Composition

In the naive quark model, the proton consists of two up quarks and one down quark (uud), while the neutron comprises one up quark and two down quarks (udd).[19] These valence quarks carry the nucleon's baryon number of +1 and determine its fundamental charge: the proton has a charge of +1 (from two up quarks with +2/3 each and one down quark with -1/3), and the neutron is electrically neutral (one up with +2/3 and two downs with -1/3 each).[19] This three-quark structure forms a color singlet, ensuring the overall wave function is antisymmetric under quark exchanges as required by the Pauli exclusion principle for fermions.[19] The nucleon's ground-state wave function separates into color, spin, flavor, and spatial components. The color part is fully antisymmetric, forming a singlet state where the three quarks have orthogonal colors (red, green, blue) that combine to colorless.[19] For the ground state with total spin , the spin-flavor part is symmetric under the SU(6) spin-flavor symmetry group, which unifies SU(3) flavor and SU(2) spin symmetries.[19] This SU(6) structure places the nucleon in the 56-dimensional representation, alongside the spin-3/2 Δ resonances, and the spatial wave function is symmetric (S-wave) for the lowest-energy configuration.[19] In this model, quarks acquire an effective constituent mass MeV due to dynamical chiral symmetry breaking and confinement effects, far exceeding the current quark masses of a few MeV.[19] This constituent mass accounts for the bulk of the nucleon's mass, estimated as approximately MeV, matching the observed proton and neutron masses after small binding corrections.[19] The valence quark model qualitatively reproduces key static properties, providing evidence for this structure. For instance, the proton charge radius and neutron's zero charge are consistent with the valence distribution, while magnetic moments arise from the quarks' intrinsic moments assuming Dirac-like , where is the quark charge.[19] The predicted proton magnetic moment is , yielding about 2.79 nuclear magnetons () if from naive assumptions, closely matching the measured 2.793 .[19] Similarly, the neutron moment is predicted as , near the experimental -1.913 .[19] Despite these successes, the naive quark model has limitations, particularly for excited states and relativistic dynamics. It overpredicts the number of nucleon resonances (predicting ~45 up to 2.4 GeV but observing only ~20), failing to account for the "missing resonance" problem due to neglect of sea quarks and gluon dynamics.[19] Additionally, it underestimates masses in higher orbital excitations and ignores relativistic effects, which distort wave functions and properties in high-energy regimes.[19]Sea Quarks, Gluons, and Parton Distributions

In the parton model, nucleons are conceptualized as composites of point-like constituents known as partons—primarily quarks, antiquarks, and gluons—each carrying a longitudinal momentum fraction (where ) relative to the nucleon's total momentum in its infinite-momentum frame. This framework, originally proposed to explain deep inelastic scattering (DIS) data, treats partons as quasi-free particles at high resolution scales, allowing the nucleon's structure to be probed via high-energy lepton-nucleon interactions. The distributions of these partons are quantified by unpolarized parton distribution functions (PDFs), denoted for a quark of flavor (e.g., ) and for gluons, where is the momentum transfer scale. These functions represent the number density of partons with momentum fraction at energy scale . A fundamental constraint on the PDFs is the momentum sum rule for the proton: which ensures that partons collectively carry all of the proton's momentum. Valence quarks (, ) dominate at large , while the sea of antiquarks and additional quark-antiquark pairs becomes prominent at smaller . The strange sea exhibits an asymmetry, with , arising from non-perturbative effects that favor strangeness production in certain nucleon fluctuations. PDFs are extracted by global fits to DIS, Drell-Yan, and jet production data from experiments at facilities like HERA, Fermilab, and the LHC. The sea quark component reveals flavor asymmetries, most notably at low , violating the naive expectation of symmetric . This asymmetry, first evidenced by the violation of the Gottfried sum rule in DIS experiments, originates from non-perturbative mechanisms such as the nucleon's meson cloud (e.g., virtual emission preferentially producing pairs) or coherent gluon splittings in quantum chromodynamics (QCD). At very small , the gluon PDF dominates, carrying up to 50% or more of the proton's momentum due to rapid growth from QCD radiation, driving much of the sea quark production via processes. Polarized PDFs, denoted for quarks and for gluons, quantify the spin contributions by measuring the difference between parton distributions parallel and antiparallel to the nucleon's helicity. The first moments represent the net quark helicity contribution to the proton spin. Measurements from polarized DIS, such as those by the European Muon Collaboration (EMC) and subsequent experiments (e.g., SMC, HERMES, Jefferson Lab), revealed , far below the naive quark model prediction of 1, sparking the "proton spin crisis." This implies significant roles for gluon helicity , quark orbital angular momentum , and possibly other contributions to satisfy the angular momentum sum . The scale dependence of PDFs is governed by the Dokshitzer-Gribov-Lipatov-Altarelli-Parisi (DGLAP) evolution equations, which describe perturbative QCD branching: where are the splitting functions encoding probabilities for parton emission, and is the strong coupling. These equations, solved numerically at next-to-leading or next-to-next-to-leading order, allow PDFs to be evolved from low-scale fits (e.g., from DIS data at GeV²) to higher scales relevant for hadron colliders, with uncertainties quantified via Hessian or Monte Carlo methods in global analyses.Antinucleons

Properties of Antiprotons and Antineutrons

Antiprotons and antineutrons are the antiparticles of protons and neutrons, respectively, and exhibit properties that are mirrored to those of their matter counterparts under the CPT theorem. The antiproton consists of two anti-up antiquarks and one anti-down antiquark in its valence structure (\bar{u}\bar{u}\bar{d}), with charges of -2/3 e for each \bar{u} and +1/3 e for \bar{d}, resulting in an electric charge of -1 e.[23] The antineutron, by contrast, has a valence composition of one anti-up antiquark and two anti-down antiquarks (\bar{u}\bar{d}\bar{d}), with charges -2/3 e for \bar{u} and +1/3 e for each \bar{d}, yielding a neutral charge of 0. Their masses are identical to those of the proton (938.272 MeV/c²) and neutron (939.565 MeV/c²), respectively, as required by CPT invariance.[24] Both antinucleons possess the same spin and parity as nucleons, with total angular momentum J = 1/2 and positive parity (J^P = 1/2^+), reflecting their ground-state baryon nature in the quark model.[24] The magnetic dipole moment of the antiproton (μ_{\bar{p}} = -2.7928473441(42) μ_N) has been measured as the negative of the proton's, in accordance with CPT symmetry, by the BASE collaboration at CERN to parts-per-billion accuracy.[24] The antineutron magnetic moment is predicted to be the negative of the neutron's measured value μ_n = -1.9130427(5) μ_N, so μ_{\bar{n}} = +1.9130427(5) μ_N, though it has not yet been directly measured experimentally. As of 2025, the BASE experiment continues to improve precision on the antiproton magnetic moment.[25] Unlike nucleons, which form stable atoms, antiprotons and antineutrons do not occur in stable anti-atoms in nature due to their rapid annihilation upon interaction with ordinary matter. Antinucleons carry baryon number B = -1, opposite to that of nucleons. While CP symmetry is conserved in strong and electromagnetic interactions involving antinucleons, it is violated in weak decays, consistent with observations in the matter sector.Production, Annihilation, and CP Violation

Antinucleons are produced via pair production processes in high-energy collisions, where the center-of-mass energy must exceed the rest masses of the particle-antiparticle pair. In proton-proton interactions, the threshold for producing an antiproton, as in , requires , with MeV being the nucleon mass. Antineutrons can be produced similarly in associated production or via charge-exchange reactions such as .[26] Modern facilities, such as CERN's Antiproton Decelerator (AD), generate low-energy antiprotons by directing a 26 GeV/c proton beam from the Proton Synchrotron onto an iridium target, yielding antiprotons that are subsequently collected in the Antiproton Collector ring, cooled via stochastic and electron cooling, and decelerated to momenta as low as 100 keV/c in the ELENA extension for precision experiments.[27] Antiproton-proton annihilation typically proceeds through the strong interaction, producing an average of 5 to 6 pions, with multiplicities ranging from 5 to 10 particles including neutral pions that subsequently decay into photons.[28] At low relative velocities, near rest, the annihilation cross section is approximately 50--60 mb, dominating over elastic scattering, and decreases with increasing antiproton momentum as the interaction becomes more peripheral.[29] Detailed studies of annihilation dynamics, including pion multiplicities and angular distributions, were conducted at CERN's Low Energy Antiproton Ring (LEAR), which operated from 1982 to 1996 and provided high-intensity, low-energy antiproton beams for such measurements.[26] Searches for CP violation in antinucleon systems focus on annihilation channels and symmetry tests, as although ground-state antinucleons can undergo weak decays with lifetimes similar to nucleons (e.g., ~880 s for free antineutron), they annihilate rapidly via the strong force when interacting with ordinary matter. The CPLEAR experiment at CERN demonstrated direct CP violation through measurements of the asymmetry in versus decays, providing evidence for T-violation equivalent to CP violation under the CPT theorem.[26] No direct CP-violating effects have been observed in primary antinucleon annihilation processes, but stringent limits arise from electric dipole moment (EDM) searches, which probe permanent EDMs sensitive to CP-odd interactions; the BASE experiment at CERN is conducting precision spin precession measurements to search for the antiproton EDM, with ongoing efforts aiming for sensitivities below as of 2025.[30] Complementary tests use antihydrogen, formed by combining antiprotons with positrons, where the ALPHA experiment at CERN performs laser spectroscopy to compare energy levels with hydrogen, setting limits on CP violation through differential shifts and improving sensitivities to possible antihydrogen EDM effects toward .[31]Stability and Conservation

Baryon Number Conservation

The baryon number is a quantum number assigned to particles, with for baryons such as nucleons, which consist of three valence quarks (), and for mesons composed of a quark-antiquark pair (). Antinucleons carry . This assignment ensures that the total baryon number remains unchanged in all observed strong, electromagnetic, and weak interactions within the Standard Model (SM) of particle physics, making it a conserved quantity empirically verified across numerous processes.[32] The conservation of baryon number arises from an accidental global symmetry in the SM Lagrangian, which emerges due to the structure of the gauge interactions and the absence of terms that explicitly violate at the renormalizable level.[33] Although this symmetry is anomalous and can be violated by non-perturbative effects like sphalerons (which conserve ), such processes are negligible at low energies and do not lead to observable decays for nucleons. In extensions beyond the SM, such as grand unified theories (GUTs), baryon number is not fundamental; quarks and leptons are unified in larger representations, allowing proton decay mediated by heavy gauge bosons at energy scales around GeV, far above electroweak energies.[34] This conservation law implies that nucleons are stable against spontaneous decay into non-baryonic final states, such as leptons or lighter hadrons, as such processes would require . However, the neutron, being slightly heavier than the proton, undergoes beta decay via the weak interaction while preserving baryon number: where the initial and final baryon numbers are both .[32] The proton, with no lighter baryon to decay into while conserving energy and other quantum numbers, remains stable on cosmological timescales. Experimental searches for baryon number violation, particularly proton decay, have yielded no evidence, setting stringent lower limits on the proton lifetime. The Super-Kamiokande experiment, using over 0.3 Mton·years of exposure in ultrapure water, reports a lower limit of years at 90% confidence level, excluding many minimal GUT models and constraining physics at scales up to GeV. No processes have been observed, reinforcing the robustness of baryon number conservation in the SM.Lifetimes of Free Nucleons

Free protons exhibit remarkable stability, with no decay events observed in extensive experimental searches. The most stringent lower limits on the proton lifetime come from detectors like Super-Kamiokande, which have probed dominant decay modes such as , establishing a partial lifetime limit exceeding years at 90% confidence level. Similar searches for other modes, including and , yield limits above years and years (updated as of 2024), respectively, reinforcing the proton's stability to lifetimes far beyond the age of the universe.[16] In contrast, free neutrons are unstable and decay almost exclusively through the weak interaction via the channel , with a measured mean lifetime of s (as of the 2025 UCNτ experiment at LANL). This process is mediated by the vector-axial vector (V-A) structure of the weak current, and the corresponding value, which incorporates phase-space and radiative corrections, is approximately 1099 s, serving as a fundamental calibration for beta decay studies across nuclear and particle physics. Precise measurements of have been achieved using ultracold neutron (UCN) techniques at facilities such as the Institut Laue-Langevin (ILL) and the Los Alamos National Laboratory (LANL), where neutrons are trapped in gravitational or magnetic bottles to monitor decay rates directly; notable results include s from ILL's gravitational trap experiment, s from LANL's UCNτ (2025), and earlier beam method results around 887 s from NIST, highlighting an ongoing discrepancy between bottle and beam techniques. These determinations, combined with the neutron's beta asymmetry parameter , enable extraction of the Cabibbo-Kobayashi-Maskawa (CKM) matrix element (world average as of 2024), providing a key test of weak interaction unitarity with minimal hadronic uncertainties.[35][36][37][38] When nucleons are bound within atomic nuclei, their effective lifetimes differ significantly from the free case due to interactions with the nuclear medium. Bound protons remain stable, akin to their free counterparts, but with even stricter experimental limits on decay modes exceeding years for processes like bound , as probed in water Cherenkov detectors. For bound neutrons, the free beta decay channel is suppressed because the Pauli exclusion principle blocks the final proton state if it lies below the Fermi level, preventing occupation of already filled orbitals; this Pauli blocking, along with insufficient Q-value in stable nuclei, enhances neutron stability, though beta processes can still occur if energetically allowed, leading to nuclear instability rather than free particle emission. Overall, no free nucleon decays are observed in nuclei, underscoring the role of quantum many-body effects in maintaining nuclear integrity.[16][38]Theoretical Models

Skyrmion and Chiral Models

The Skyrme model is an effective field theory that describes nucleons as topological solitons, known as skyrmions, embedded in a nonlinear sigma model of pion fields. This approach arises from the low-energy effective theory of quantum chromodynamics (QCD), where the spontaneous breaking of chiral symmetry generates Goldstone bosons in the form of pions. In the model, the nucleon emerges as a stable, localized configuration of the pion field that carries baryon number through its topology. Specifically, the baryon number is quantized as the winding number of the field configuration in the target space SU(2), corresponding to the third homotopy group π₃(S³) = ℤ, with the nucleon assigned a winding number of 1.[39] The dynamics of the Skyrme model are governed by a Lagrangian density that includes the leading-order chiral invariant term from the nonlinear sigma model and a stabilizing fourth-order Skyrme term to prevent classical collapse of the soliton. The Lagrangian is given by where U is a unitary matrix in the SU(2) flavor space parameterizing the pion fields, f_π ≈ 93 MeV is the pion decay constant, and e is a dimensionless parameter of order 4-5 that sets the scale of the higher-order term. The classical soliton solution, hedgehog configuration, has a size determined by the balance between these terms, yielding a root-mean-square radius of approximately 0.8 fm for the nucleon. The classical soliton mass is around 800 MeV, which is adjusted closer to the observed nucleon mass of 938 MeV through quantum corrections, including zero-point vibrations and rotational inertia.[39][40] To incorporate spin and isospin, the model employs collective coordinates, treating the soliton as a rigid rotor in both spin and isospin spaces. This quantization leads to predictions for static nucleon properties, such as the axial vector coupling constant g_A ≈ 0.6 (compared to the experimental value of 1.27, improved by higher-order terms) and the isovector magnetic moment, which align reasonably with observations after parameter fitting. The model also naturally explains the equivalence of spin and isospin degrees of freedom in the nucleon ground state.[40] The chiral bag model extends the Skyrme framework by hybridizing it with quark degrees of freedom, confining three valence quarks within a spherical bag of radius R ≈ 0.6-0.8 fm, while the exterior region is described by the Skyrme soliton field matching chiral boundary conditions at the surface. This construction resolves issues in pure bag models by allowing pions to couple directly to quarks via the chiral covariant derivative, generating a pion cloud that contributes to the nucleon's size and magnetic properties. The model self-consistently determines the bag radius through minimization of the total energy, incorporating Casimir effects from quark zero modes and the soliton energy outside, and provides a mechanism for the pion cloud to enhance the nucleon's axial properties without violating confinement.Confinement Models (Bag and Lattice QCD)

The MIT bag model conceptualizes the nucleon as a system of three valence quarks confined within a spherical "bag" of radius , where the quarks are treated as non-interacting fermions obeying the Dirac equation inside the cavity, and confinement is enforced by a boundary condition on the quark wave function at the surface: , with the outward normal vector. This condition ensures the vanishing of the normal component of the axial current, preventing quark leakage while maintaining spherical symmetry for the ground state. The total energy of the system comprises the kinetic energy of the quarks and a phenomenological bag constant representing the vacuum energy difference between the perturbative quark-gluon interior and the non-perturbative QCD exterior: where the first term is the sum of the zero-point kinetic energies for the lowest-mode s-wave configuration of three massless quarks (with the precise eigenvalue factor per quark, adjusted for color and spin-isospin symmetry). Minimizing with respect to yields an equilibrium radius fm and a nucleon mass MeV when , providing a qualitative description of confinement though underestimating the observed mass by about 4% due to neglected interactions.[41] The chiral bag model extends the MIT framework by incorporating chiral symmetry through pion fields that penetrate the bag boundary, addressing limitations in reproducing low-energy nucleon-pion couplings. In this hybrid approach, the interior remains a quark bag, but the exterior includes a hedgehog pion configuration matching onto the quark axial current at the surface via a nonlinear boundary condition that couples the scalar density to the pion gradient. This setup restores partial chiral invariance and naturally derives the Goldberger-Treiman relation, , linking the pion-nucleon coupling , axial charge , nucleon mass , and pion decay constant , without ad hoc adjustments. The model reduces the required bag constant and yields a smaller equilibrium radius ( fm), improving predictions for static properties like the nucleon magnetic moment while bridging quark-level dynamics with meson cloud effects.[42] Lattice quantum chromodynamics (QCD) provides a non-perturbative, ab initio framework for nucleon structure by discretizing spacetime on a hypercubic lattice and evolving the quark and gluon fields via the path integral, capturing confinement through the strong-coupling dynamics of the Yang-Mills action. The nucleon mass emerges from exponential decay of two-point correlation functions of interpolated quark operators, with simulations using 2+1 dynamical quark flavors (up, down, and strange) at physical pion masses achieving MeV to within 1% precision after continuum and finite-volume extrapolations. Recent advances employ hybrid lattice setups, combining Wilson-clover or domain-wall fermions with improved gauge actions on ensembles like those from the Coordinated Lattice Simulations (CLS) collaboration, to compute electromagnetic form factors such as the isovector Dirac and Pauli radii. These yield predictions for the isovector magnetic moment , aligning closely with experimental values of and validating the approach for non-perturbative quantities.[43][44][45]Nucleon Resonances

Excited States and Classification

Nucleon resonances, often denoted as N*, are excited states of the nucleon that share the same quantum numbers as the ground-state nucleon—such as baryon number B=1 and isospin I=1/2 for nucleons (N) or I=3/2 for deltas (Δ)—but possess higher masses due to internal excitations of their quark constituents.[46] These states are unstable and decay rapidly, distinguishing them from the stable ground-state proton and neutron. Prominent examples include the Δ(1232) with spin-parity J^P = 3/2^+ and mass around 1232 MeV, and the Roper resonance N(1440) with J^P = 1/2^+ and mass near 1440 MeV.[46] The classification of nucleon resonances is primarily guided by the Particle Data Group (PDG), which assigns ratings from one to four stars based on the consistency and quality of experimental evidence for their existence and properties.[46] In the quark model, these resonances are organized into levels corresponding to orbital angular momentum excitations of the quarks, such as L=0 (S-wave) for the ground state and L=1 (P-wave) for the first excited states, leading to specific spin-parity assignments.[19] Furthermore, under flavor SU(3) symmetry, the resonances group into multiplets; for instance, the ground-state octet (including the nucleon) and decuplet (including the Δ) reside in the 56-plet of SU(6), while the first negative-parity excitations, like the N(1535) with J^P = 1/2^-, belong to the 70-plet, which decomposes into SU(3) representations such as 10 ⊕ 8 ⊕ 8 ⊕ 1.[19] The spectrum of nucleon resonances begins with the lowest-lying state, the Δ(1232) at 1232 MeV with J^P = 3/2^+.[46] Subsequent states include the N(1535) at around 1535 MeV with J^P = 1/2^-, marking the onset of negative-parity excitations in the P-wave level.[46] Higher resonances extend up to several GeV, with the PDG listing approximately 20 well-established (three- or four-star) states for N and Δ.[46][19] These resonances predominantly decay via the strong interaction into a ground-state nucleon and a pion (Nπ), reflecting their hadronic nature, or electromagnetically into a nucleon and photon (Nγ) for neutral or charged modes.[46] Their total decay widths Γ typically range from 50 to 500 MeV, indicating lifetimes on the order of 10^{-24} to 10^{-23} seconds, with broader widths for lower-lying states like the Δ(1232) at about 120 MeV due to efficient strong decays.[46]| Resonance | J^P | Mass (MeV) | Width (MeV) | PDG Status | SU(3) Multiplet Example |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Δ(1232) | 3/2^+ | 1232 | ~120 | **** | 56 (decuplet) |

| N(1440) | 1/2^+ | 1440 | ~300 | **** | 70 (mixed) |

| N(1535) | 1/2^- | 1535 | ~150 | **** | 70 (octet) |