Recent from talks

Contribute something

Nothing was collected or created yet.

OSI model

View on Wikipedia

| OSI model by layer |

|---|

The Open Systems Interconnection (OSI) model is a reference model developed by the International Organization for Standardization (ISO) that "provides a common basis for the coordination of standards development for the purpose of systems interconnection."[2]

In the OSI reference model, the components of a communication system are distinguished in seven abstraction layers: Physical, Data Link, Network, Transport, Session, Presentation, and Application.[3]

The model describes communications from the physical implementation of transmitting bits across a transmission medium to the highest-level representation of data of a distributed application. Each layer has well-defined functions and semantics and serves a class of functionality to the layer above it and is served by the layer below it. Established, well-known communication protocols are decomposed in software development into the model's hierarchy of function calls.

The Internet protocol suite as defined in RFC 1122 and RFC 1123 is a model of networking developed contemporarily to the OSI model, and was funded primarily by the U.S. Department of Defense. It was the foundation for the development of the Internet. It assumed the presence of generic physical links and focused primarily on the software layers of communication, with a similar but much less rigorous structure than the OSI model.

In comparison, several networking models have sought to create an intellectual framework for clarifying networking concepts and activities,[citation needed] but none have been as successful as the OSI reference model in becoming the standard model for discussing and teaching networking in the field of information technology. The model allows transparent communication through equivalent exchange of protocol data units (PDUs) between two parties, through what is known as peer-to-peer networking (also known as peer-to-peer communication). As a result, the OSI reference model has not only become an important piece among professionals and non-professionals alike, but also in all networking between one or many parties, due in large part to its commonly accepted user-friendly framework.[4]

History

[edit]The development of the OSI model started in the late 1970s to support the emergence of the diverse computer networking methods that were competing for application in the large national networking efforts in the world (see OSI protocols and Protocol Wars). In the 1980s, the model became a working product of the Open Systems Interconnection group at the International Organization for Standardization (ISO). While attempting to provide a comprehensive description of networking, the model failed to garner reliance during the design of the Internet, which is reflected in the less prescriptive Internet Protocol Suite, principally sponsored under the auspices of the Internet Engineering Task Force (IETF).

In the early- and mid-1970s, networking was largely either government-sponsored (NPL network in the UK, ARPANET in the US, CYCLADES in France) or vendor-developed with proprietary standards, such as IBM's Systems Network Architecture and Digital Equipment Corporation's DECnet. Public data networks were only just beginning to emerge, and these began to use the X.25 standard in the late 1970s.[5][6]

The Experimental Packet Switched System in the UK c. 1973–1975 identified the need for defining higher-level protocols.[5] The UK National Computing Centre publication, Why Distributed Computing, which came from considerable research into future configurations for computer systems,[7] resulted in the UK presenting the case for an international standards committee to cover this area at the ISO meeting in Sydney in March 1977.[8][9]

Beginning in 1977, the ISO initiated a program to develop general standards and methods of networking. A similar process evolved at the International Telegraph and Telephone Consultative Committee (CCITT, from French: Comité Consultatif International Téléphonique et Télégraphique). Both bodies developed documents that defined similar networking models. The British Department of Trade and Industry acted as the secretariat, and universities in the United Kingdom developed prototypes of the standards.[10]

The OSI model was first defined in raw form in Washington, D.C., in February 1978 by French software engineer Hubert Zimmermann, and the refined but still draft standard was published by the ISO in 1980.[9]

The drafters of the reference model had to contend with many competing priorities and interests. The rate of technological change made it necessary to define standards that new systems could converge to rather than standardizing procedures after the fact; the reverse of the traditional approach to developing standards.[11] Although not a standard itself, it was a framework in which future standards could be defined.[12]

In May 1983,[13] the CCITT and ISO documents were merged to form The Basic Reference Model for Open Systems Interconnection, usually referred to as the Open Systems Interconnection Reference Model, OSI Reference Model, or simply OSI model. It was published in 1984 by both the ISO, as standard ISO 7498, and the renamed CCITT (now called the Telecommunications Standardization Sector of the International Telecommunication Union or ITU-T) as standard X.200.

OSI had two major components: an abstract model of networking, called the Basic Reference Model or seven-layer model, and a set of specific protocols. The OSI reference model was a major advance in the standardisation of network concepts. It promoted the idea of a consistent model of protocol layers, defining interoperability between network devices and software.

The concept of a seven-layer model was provided by the work of Charles Bachman at Honeywell Information Systems.[14] Various aspects of OSI design evolved from experiences with the NPL network, ARPANET, CYCLADES, EIN, and the International Network Working Group (IFIP WG6.1). In this model, a networking system was divided into layers. Within each layer, one or more entities implement its functionality. Each entity interacted directly only with the layer immediately beneath it and provided facilities for use by the layer above it.

The OSI standards documents are available from the ITU-T as the X.200 series of recommendations.[15] Some of the protocol specifications were also available as part of the ITU-T X series. The equivalent ISO/IEC standards for the OSI model were available from ISO. Not all are free of charge.[16]

OSI was an industry effort, attempting to get industry participants to agree on common network standards to provide multi-vendor interoperability.[17] It was common for large networks to support multiple network protocol suites, with many devices unable to interoperate with other devices because of a lack of common protocols. For a period in the late 1980s and early 1990s, engineers, organizations and nations became polarized over the issue of which standard, the OSI model or the Internet protocol suite, would result in the best and most robust computer networks.[9][18][19] However, while OSI developed its networking standards in the late 1980s,[20][page needed][21][page needed] TCP/IP came into widespread use on multi-vendor networks for internetworking.

The OSI model is still used as a reference for teaching and documentation;[22] however, the OSI protocols originally conceived for the model did not gain popularity. Some engineers argue the OSI reference model is still relevant to cloud computing.[23] Others say the original OSI model does not fit today's networking protocols and have suggested instead a simplified approach.[24][25]

Definitions

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (November 2019) |

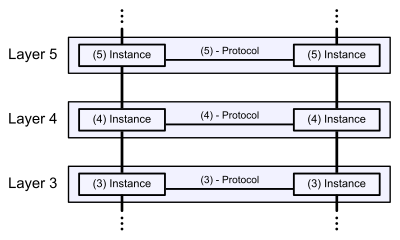

Communication protocols enable an entity in one host to interact with a corresponding entity at the same layer in another host. Service definitions, like the OSI model, abstractly describe the functionality provided to a layer N by a layer N−1, where N is one of the seven layers of protocols operating in the local host (with N=1 being the most basic layer, often represented at the bottom of a list).

At each level N, two entities at the communicating devices (layer N peers) exchange protocol data units (PDUs) by means of a layer N protocol. Each PDU contains a payload, called the service data unit (SDU), along with protocol-related headers or footers.

Data processing by two communicating OSI-compatible devices proceeds as follows:

- The data to be transmitted is composed at the topmost layer of the transmitting device (layer N) into a protocol data unit (PDU).

- The PDU is passed to layer N−1, where it is known as the service data unit (SDU).

- At layer N−1 the SDU is concatenated with a header, a footer, or both, producing a layer N−1 PDU. It is then passed to layer N−2.

- The process continues until reaching the lowermost level, from which the data is transmitted to the receiving device.

- At the receiving device the data is passed from the lowest to the highest layer as a series of SDUs while being successively stripped from each layer's header or footer until reaching the topmost layer, where the last of the data is consumed.

Standards documents

[edit]The OSI model was defined in ISO/IEC 7498 which consists of the following parts:

- ISO/IEC 7498-1 The Basic Model

- ISO/IEC 7498-2 Security Architecture

- ISO/IEC 7498-3 Naming and addressing

- ISO/IEC 7498-4 Management framework

ISO/IEC 7498-1 is also published as ITU-T Recommendation X.200.

Layer architecture

[edit]The recommendation X.200 describes seven layers, labelled 1 to 7. Layer 1 is the lowest layer in this model.

| Layer | Protocol data unit (PDU) | Function[26] | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Host layers |

7 | Application | Data | High-level protocols such as for resource sharing or remote file access, e.g. HTTP. |

| 6 | Presentation | Translation of data between a networking service and an application; including character encoding, data compression and encryption/decryption | ||

| 5 | Session | Managing communication sessions, i.e., continuous exchange of information in the form of multiple back-and-forth transmissions between two nodes | ||

| 4 | Transport | Segment | Reliable transmission of data segments between points on a network, including segmentation, acknowledgement and multiplexing | |

| Media layers |

3 | Network | Packet, Datagram[27] | Structuring and managing a multi-node network, including addressing, routing and traffic control |

| 2 | Data link | Frame | Transmission of data frames between two nodes connected by a physical layer | |

| 1 | Physical | Bit, Symbol | Transmission and reception of raw bit streams over a physical medium | |

Layer 1: Physical layer

[edit]The physical layer is responsible for the transmission and reception of unstructured raw data between a device, such as a network interface controller, Ethernet hub, or network switch, and a physical transmission medium. It converts the digital bits into electrical, radio, or optical signals (analogue signals). Layer specifications define characteristics such as voltage levels, the timing of voltage changes, physical data rates, maximum transmission distances, modulation scheme, channel access method and physical connectors. This includes the layout of pins, voltages, line impedance, cable specifications, signal timing and frequency for wireless devices. Bit rate control is done at the physical layer and may define transmission mode as simplex, half duplex, and full duplex. The components of a physical layer can be described in terms of the network topology. Physical layer specifications are included in the specifications for the ubiquitous Bluetooth, Ethernet, and USB standards. An example of a less well-known physical layer specification would be for the CAN standard.

The physical layer also specifies how encoding occurs over a physical signal, such as electrical voltage or a light pulse. For example, a 1 bit might be represented on a copper wire by the transition from a 0-volt to a 5-volt signal, whereas a 0 bit might be represented by the transition from a 5-volt to a 0-volt signal. As a result, common problems occurring at the physical layer are often related to the incorrect media termination, EMI or noise scrambling, and NICs and hubs that are misconfigured or do not work correctly.

Layer 2: Data link layer

[edit]The data link layer provides node-to-node data transfer—a link between two directly connected nodes. It detects and possibly corrects errors that may occur in the physical layer. It defines the protocol to establish and terminate a connection between two physically connected devices. It also defines the protocol for flow control between them.

IEEE 802 divides the data link layer into two sublayers:[28]

- Medium access control (MAC) layer – responsible for controlling how devices in a network gain access to a medium and permission to transmit data.

- Logical link control (LLC) layer – responsible for identifying and encapsulating network layer protocols, and controls error checking and frame synchronization.

The MAC and LLC layers of IEEE 802 networks such as 802.3 Ethernet, 802.11 Wi-Fi, and 802.15.4 Zigbee operate at the data link layer.

The Point-to-Point Protocol (PPP) is a data link layer protocol that can operate over several different physical layers, such as synchronous and asynchronous serial lines.

The ITU-T G.hn standard, which provides high-speed local area networking over existing wires (power lines, phone lines and coaxial cables), includes a complete data link layer that provides both error correction and flow control by means of a selective-repeat sliding-window protocol.

Security, specifically (authenticated) encryption, at this layer can be applied with MACsec.

Layer 3: Network layer

[edit]The network layer provides the functional and procedural means of transferring packets from one node to another connected in "different networks". A network is a medium to which many nodes can be connected, on which every node has an address and which permits nodes connected to it to transfer messages to other nodes connected to it by merely providing the content of a message and the address of the destination node and letting the network find the way to deliver the message to the destination node, possibly routing it through intermediate nodes. If the message is too large to be transmitted from one node to another on the data link layer between those nodes, the network may implement message delivery by splitting the message into several fragments at one node, sending the fragments independently, and reassembling the fragments at another node. It may, but does not need to, report delivery errors.

Message delivery at the network layer is not necessarily guaranteed to be reliable; a network layer protocol may provide reliable message delivery, but it does not need to do so.

A number of layer-management protocols, a function defined in the management annex, ISO 7498/4, belong to the network layer. These include routing protocols, multicast group management, network-layer information and error, and network-layer address assignment. It is the function of the payload that makes these belong to the network layer, not the protocol that carries them.[29]

Security, specifically (authenticated) encryption, at this layer can be applied with IPsec.

Layer 4: Transport layer

[edit]The transport layer provides the functional and procedural means of transferring variable-length data sequences from a source host to a destination host from one application to another across a network while maintaining the quality-of-service functions. Transport protocols may be connection-oriented or connectionless.

This may require breaking large protocol data units or long data streams into smaller chunks called "segments", since the network layer imposes a maximum packet size called the maximum transmission unit (MTU), which depends on the maximum packet size imposed by all data link layers on the network path between the two hosts. The amount of data in a data segment must be small enough to allow for a network-layer header and a transport-layer header. For example, for data being transferred across Ethernet, the MTU is 1500 bytes, the minimum size of a TCP header is 20 bytes, and the minimum size of an IPv4 header is 20 bytes, so the maximum segment size is 1500−(20+20) bytes, or 1460 bytes. The process of dividing data into segments is called segmentation; it is an optional function of the transport layer. Some connection-oriented transport protocols, such as TCP and the OSI connection-oriented transport protocol (COTP), perform segmentation and reassembly of segments on the receiving side; connectionless transport protocols, such as UDP and the OSI connectionless transport protocol (CLTP), usually do not.

The transport layer also controls the reliability of a given link between a source and destination host through flow control, error control, and acknowledgments of sequence and existence. Some protocols are state- and connection-oriented. This means that the transport layer can keep track of the segments and retransmit those that fail delivery through the acknowledgment hand-shake system. The transport layer will also provide the acknowledgement of the successful data transmission and sends the next data if no errors occurred.

Reliability, however, is not a strict requirement within the transport layer. Protocols like UDP, for example, are used in applications that are willing to accept some packet loss, reordering, errors or duplication. Streaming media, real-time multiplayer games and voice over IP (VoIP) are examples of applications in which loss of packets is not usually a fatal problem.

The OSI connection-oriented transport protocol defines five classes of connection-mode transport protocols, ranging from class 0 (which is also known as TP0 and provides the fewest features) to class 4 (TP4, designed for less reliable networks, similar to the Internet). Class 0 contains no error recovery and was designed for use on network layers that provide error-free connections. Class 4 is closest to TCP, although TCP contains functions, such as the graceful close, which OSI assigns to the session layer. Also, all OSI TP connection-mode protocol classes provide expedited data and preservation of record boundaries. Detailed characteristics of TP0–4 classes are shown in the following table:[30]

| Feature name | TP0 | TP1 | TP2 | TP3 | TP4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Connection-oriented network | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Connectionless network | No | No | No | No | Yes |

| Concatenation and separation | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Segmentation and reassembly | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Error recovery | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Reinitiate connectiona | No | Yes | No | Yes | No |

| Multiplexing / demultiplexing over single virtual circuit | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Explicit flow control | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Retransmission on timeout | No | No | No | No | Yes |

| Reliable transport service | No | Yes | No | Yes | Yes |

| a If an excessive number of PDUs are unacknowledged. | |||||

An easy way to visualize the transport layer is to compare it with a post office, which deals with the dispatch and classification of mail and parcels sent. A post office inspects only the outer envelope of mail to determine its delivery. Higher layers may have the equivalent of double envelopes, such as cryptographic presentation services that can be read by the addressee only. Roughly speaking, tunnelling protocols operate at the transport layer, such as carrying non-IP protocols such as IBM's SNA or Novell's IPX over an IP network, or end-to-end encryption with IPsec. While Generic Routing Encapsulation (GRE) might seem to be a network-layer protocol, if the encapsulation of the payload takes place only at the endpoint, GRE becomes closer to a transport protocol that uses IP headers but contains complete Layer 2 frames or Layer 3 packets to deliver to the endpoint. L2TP carries PPP frames inside transport segments.

Although not developed under the OSI Reference Model and not strictly conforming to the OSI definition of the transport layer, the Transmission Control Protocol (TCP) and the User Datagram Protocol (UDP) of the Internet Protocol Suite are commonly categorized as layer 4 protocols within OSI.

Transport Layer Security (TLS) does not strictly fit inside the model either. It contains characteristics of the transport and presentation layers.[31][32]

Layer 5: Session layer

[edit]The session layer creates the setup, controls the connections, and ends the teardown, between two or more computers, which is called a "session". Common functions of the session layer include user logon (establishment) and user logoff (termination) functions. Including this matter, authentication methods are also built into most client software, such as FTP Client and NFS Client for Microsoft Networks. Therefore, the session layer establishes, manages and terminates the connections between the local and remote applications. The session layer also provides for full-duplex, half-duplex, or simplex operation,[citation needed] and establishes procedures for checkpointing, suspending, restarting, and terminating a session between two related streams of data, such as an audio and a video stream in a web-conferencing application. Therefore, the session layer is commonly implemented explicitly in application environments that use remote procedure calls.

Layer 6: Presentation layer

[edit]The presentation layer establishes data formatting and data translation into a format specified by the application layer during the encapsulation of outgoing messages while being passed down the protocol stack, and possibly reversed during the deencapsulation of incoming messages when being passed up the protocol stack. For this very reason, outgoing messages during encapsulation are converted into a format specified by the application layer, while the conversion for incoming messages during deencapsulation are reversed.

The presentation layer handles protocol conversion, data encryption, data decryption, data compression, data decompression, incompatibility of data representation between operating systems, and graphic commands. The presentation layer transforms data into the form that the application layer accepts, to be sent across a network. Since the presentation layer converts data and graphics into a display format for the application layer, the presentation layer is sometimes called the syntax layer.[33] For this reason, the presentation layer negotiates the transfer of syntax structure through the Basic Encoding Rules of Abstract Syntax Notation One (ASN.1), with capabilities such as converting an EBCDIC-coded text file to an ASCII-coded file, or serialization of objects and other data structures from and to XML.[4]

Layer 7: Application layer

[edit]The application layer is the layer of the OSI model that is closest to the end user, which means both the OSI application layer and the user interact directly with a software application that implements a component of communication between the client and server, such as File Explorer and Microsoft Word. Such application programs fall outside the scope of the OSI model unless they are directly integrated into the application layer through the functions of communication, as is the case with applications such as web browsers and email programs. Other examples of software are Microsoft Network Software for File and Printer Sharing and Unix/Linux Network File System Client for access to shared file resources.

Application-layer functions typically include file sharing, message handling, and database access, through the most common protocols at the application layer, known as HTTP, FTP, SMB/CIFS, TFTP, and SMTP. When identifying communication partners, the application layer determines the identity and availability of communication partners for an application with data to transmit. The most important distinction in the application layer is the distinction between the application entity and the application. For example, a reservation website might have two application entities: one using HTTP to communicate with its users, and one for a remote database protocol to record reservations. Neither of these protocols have anything to do with reservations. That logic is in the application itself. The application layer has no means to determine the availability of resources in the network.[4]

Cross-layer functions

[edit]Cross-layer functions are services that are not tied to a given layer, but may affect more than one layer.[34] Some orthogonal aspects, such as management and security, involve all of the layers (See ITU-T X.800 Recommendation[35]). These services are aimed at improving the CIA triad—confidentiality, integrity, and availability—of the transmitted data. Cross-layer functions are the norm, in practice, because the availability of a communication service is determined by the interaction between network design and network management protocols.

Specific examples of cross-layer functions include the following:

- Security service (telecommunication)[35] as defined by ITU-T X.800 recommendation.

- Management functions, i.e. functions that permit to configure, instantiate, monitor, terminate the communications of two or more entities: there is a specific application-layer protocol, Common Management Information Protocol (CMIP) and its corresponding service, Common Management Information Service (CMIS), they need to interact with every layer in order to deal with their instances.

- Multiprotocol Label Switching (MPLS), ATM, and X.25 are 3a protocols. OSI subdivides the Network Layer into three sublayers: 3a) Subnetwork Access, 3b) Subnetwork Dependent Convergence and 3c) Subnetwork Independent Convergence.[36] It was designed to provide a unified data-carrying service for both circuit-based clients and packet-switching clients which provide a datagram-based service model. It can be used to carry many different kinds of traffic, including IP packets, as well as native ATM, SONET, and Ethernet frames. Sometimes one sees reference to a Layer 2.5.

- Cross MAC and PHY Scheduling is essential in wireless networks because of the time-varying nature of wireless channels. By scheduling packet transmission only in favourable channel conditions, which requires the MAC layer to obtain channel state information from the PHY layer, network throughput can be significantly improved and energy waste can be avoided.[37][page needed]

Programming interfaces

[edit]Neither the OSI Reference Model, nor any OSI protocol specifications, outline any programming interfaces, other than deliberately abstract service descriptions. Protocol specifications define a methodology for communication between peers, but the software interfaces are implementation-specific.

For example, the Network Driver Interface Specification (NDIS) and Open Data-Link Interface (ODI) are interfaces between the media (layer 2) and the network protocol (layer 3).

Comparison to other networking suites

[edit]The table below presents a list of OSI layers, the original OSI protocols, and some approximate modern matches. This correspondence is rough: the OSI model contains idiosyncrasies not found in later systems such as the IP stack in modern Internet.[25]

| Layer | OSI protocols | TCP/IP protocols | Signaling System 7[38] |

AppleTalk | IPX | SNA | UMTS | HTTP-based protocols | Miscellaneous examples | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. | Name | |||||||||

| 7 | Application |

|

||||||||

| 6 | Presentation |

|

Presentation Services | |||||||

| 5 | Session |

|

Sockets (session establishment in TCP / RTP / PPTP) |

|

|

|||||

| 4 | Transport |

|

|

Port number can be specified. | ||||||

| 3 | Network | ATP (TokenTalk / EtherTalk) |

|

Out of scope. IP addresses can be used instead of domain names in URLs. | ||||||

| 2 | Data link | IEEE 802.3 framing Ethernet II framing |

|

Out of scope. | ||||||

| 1 | Physical | TCP/IP stack does not care about the physical medium, as long as it provides a way to communicate octets |

|

UMTS air interfaces | Out of scope. | |||||

Comparison with TCP/IP model

[edit]The design of protocols in the TCP/IP model of the Internet does not concern itself with strict hierarchical encapsulation and layering. RFC 3439 contains a section entitled "Layering considered harmful".[47] TCP/IP does recognize four broad layers of functionality which are derived from the operating scope of their contained protocols: the scope of the software application; the host-to-host transport path; the internetworking range; and the scope of the direct links to other nodes on the local network.[48]

Despite using a different concept for layering than the OSI model, these layers are often compared with the OSI layering scheme in the following manner:

- The Internet application layer maps to the OSI application layer, presentation layer, and most of the session layer.

- The TCP/IP transport layer maps to the graceful close function of the OSI session layer as well as the OSI transport layer.

- The internet layer performs functions as those in a subset of the OSI network layer.

- The link layer corresponds to the OSI data link layer and may include similar functions as the physical layer, as well as some protocols of the OSI's network layer.

These comparisons are based on the original seven-layer protocol model as defined in ISO 7498, rather than refinements in the internal organization of the network layer.

The OSI protocol suite that was specified as part of the OSI project was considered by many as too complicated and inefficient, and to a large extent unimplementable.[49][page needed] Taking the "forklift upgrade" approach to networking, it specified eliminating all existing networking protocols and replacing them at all layers of the stack. This made implementation difficult and was resisted by many vendors and users with significant investments in other network technologies. In addition, the protocols included so many optional features that many vendors' implementations were not interoperable.[49][page needed]

Although the OSI model is often still referenced, the Internet protocol suite has become the standard for networking. TCP/IP's pragmatic approach to computer networking and to independent implementations of simplified protocols made it a practical methodology.[49][page needed] Some protocols and specifications in the OSI stack remain in use, one example being IS-IS, which was specified for OSI as ISO/IEC 10589:2002 and adapted for Internet use with TCP/IP as RFC 1142.[50]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "X.225 : Information technology – Open Systems Interconnection – Connection-oriented Session protocol: Protocol specification". Archived from the original on 1 February 2021. Retrieved 10 March 2023.

- ^ ISO/IEC 7498-1:1994 Information technology — Open Systems Interconnection — Basic Reference Model: The Basic Model. June 1999. Introduction. Retrieved 26 August 2022.

- ^ "What is the OSI Model?". Forcepoint. 10 August 2018. Archived from the original on 24 March 2022. Retrieved 20 May 2022.

- ^ a b c Tomsho, Greg (2016). Guide to Networking Essentials (7th ed.). Cengage. Retrieved 3 April 2022.

- ^ a b Davies, Howard; Bressan, Beatrice (26 April 2010). A History of International Research Networking: The People who Made it Happen. John Wiley & Sons. pp. 2–3. ISBN 978-3-527-32710-2.

- ^ Roberts, Dr. Lawrence G. (November 1978). "The Evolution of Packet Switching" (PDF). IEEE Invited Paper. Retrieved 26 February 2022.

- ^ Down, Peter John; Taylor, Frank Edward (1976). Why distributed computing?: An NCC review of potential and experience in the UK. NCC Publications. ISBN 9780850121704.

- ^ Radu, Roxana (2019). "Revisiting the Origins: The Internet and its Early Governance". Negotiating Internet Governance. Oxford University Press. pp. 43–74. doi:10.1093/oso/9780198833079.003.0003. ISBN 9780191871405.

- ^ a b c Andrew L. Russell (30 July 2013). "OSI: The Internet That Wasn't". IEEE Spectrum. Vol. 50, no. 8.

- ^ Campbell-Kelly, Martin; Garcia-Swartz, Daniel D (2013). "The History of the Internet: The Missing Narratives". Journal of Information Technology. 28 (1): 18–33. doi:10.1057/jit.2013.4. ISSN 0268-3962. S2CID 41013. SSRN 867087.

- ^ Sunshine, Carl A. (1989). Computer Network Architectures and Protocols. Springer Science & Business Media. p. 35. ISBN 978-1-4613-0809-6.

- ^ Hasman, A. (1995). Education and Training in Health Informatics in Europe: State of the Art, Guidelines, Applications. IOS Press. p. 251. ISBN 978-90-5199-234-2.

- ^ "ISO/OSI (Open Systems Interconnection): 1982 - 1983 | History of Computer Communications". historyofcomputercommunications.info. Retrieved 12 July 2024.

- ^ J. A. N. Lee. "Computer Pioneers by J. A. N. Lee". IEEE Computer Society.

- ^ "ITU-T X-Series Recommendations".

- ^ "Publicly Available Standards". Standards.iso.org. 30 July 2010. Retrieved 11 September 2010.

- ^ Russell, Andrew L. (28 April 2014). Open Standards and the Digital Age: History, Ideology, and Networks. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-139-91661-5.

- ^ Russell, Andrew L. (July–September 2006). "Rough Consensus and Running Code' and the Internet-OSI Standards War" (PDF). IEEE Annals of the History of Computing. 28 (3): 48–61. Bibcode:2006IAHC...28c..48R. doi:10.1109/MAHC.2006.42.

- ^ "Standards Wars" (PDF). 2006.

- ^ Network World. IDG Network World Inc. 15 February 1988.

- ^ Network World. IDG Network World Inc. 10 October 1988.

- ^ Shaw, Keith (22 October 2018). "The OSI model explained: How to understand (and remember) the 7 layer network model". Network World. Archived from the original on 4 October 2020. Retrieved 16 May 2020.

- ^ "An OSI Model for Cloud". Cisco Blogs. 24 February 2017. Retrieved 16 May 2020.

- ^ Taylor, Steve; Metzler, Jim (23 September 2008). "Why it's time to let the OSI model die". Network World. Retrieved 16 May 2020.

- ^ a b Crawford, JB (27 March 2021). "The actual OSI model".

- ^ "Windows Network Architecture and the OSI Model". Microsoft Documentation. Retrieved 24 June 2020.

- ^ "What is a packet? | Network packet definition". Cloudflare.

- ^ "5.2 RM description for end stations". IEEE Std 802-2014, IEEE Standard for Local and Metropolitan Area Networks: Overview and Architecture. ieee. doi:10.1109/IEEESTD.2014.6847097. ISBN 978-0-7381-9219-2.

- ^ International Organization for Standardization (15 November 1989). "ISO/IEC 7498-4:1989 – Information technology – Open Systems Interconnection – Basic Reference Model: Management framework". ISO Standards Maintenance Portal. ISO Central Secretariat. Retrieved 16 November 2024.

- ^ "ITU-T Recommendation X.224 (11/1995) ISO/IEC 8073, Open Systems Interconnection – Protocol for providing the connection-mode transport service". ITU.

- ^ Hooper, Howard (2012). CCNP Security VPN 642-648 Official Cert Guide (2 ed.). Cisco Press. p. 22. ISBN 9780132966382.

- ^ Spott, Andrew; Leek, Tom; et al. "What layer is TLS?". Information Security Stack Exchange.

- ^ Grigonis, Richard (2000). "Open Systems Interconnection (OSI) Model". Computer Telephony Encyclopedia. New York: CMP Books. p. 331. ISBN 978-1-929629-51-0. OCLC 48138823.

- ^ Mao, Stephen (2009). "Chapter 8: Fundamentals of communication networks". In Wyglinski, Alexander; Nekovee, Maziar; Hou, Thomas (eds.). Cognitive Radio Communications and Networks: Principles and Practice. Elsevier. p. 201. ISBN 978-0-08-087932-1. OCLC 635292718, 528550718. Partial preview at Google Books.

- ^ a b "ITU-T Recommendation X.800 (03/91), Security architecture for Open Systems Interconnection for CCITT applications". ITU. Retrieved 14 August 2015.

- ^ Hegering, Heinz-Gerd; Abeck, Sebastian; Neumair, Bernhard (1999). "Fundamental Structures of Networked Systems". Integrated management of networked systems: concepts, architectures, and their operational application. San Francisco, Calif.: Morgan Kaufmann. p. 54. ISBN 978-1-55860-571-8. OCLC 1341886747 – via Internet Archive.

- ^ Miao, Guowang; Song, Guocong (2014). Energy and spectrum efficient wireless network design. New York: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-139-62677-4. OCLC 898138775 – via Internet Archive.

- ^ "ITU-T Recommendation Q.1400 (03/1993)], Architecture framework for the development of signaling and OA&M protocols using OSI concepts". ITU. pp. 4, 7.

- ^ "ITU-T X.227 (04/1995)". ITU-T Recommendations. 10 April 1995. Retrieved 12 July 2024.

- ^ "ITU-T X.217". Open Systems Interconnection. 10 April 1995. Retrieved 12 July 2024.

- ^ "X.700: Management framework for Open Systems Interconnection (OSI) for CCITT applications". ITU. 10 September 1992. Retrieved 12 July 2024.

- ^ "X.711". Open Systems Interconnection. 15 May 2014. Retrieved 12 July 2024.

- ^ "ISO/IEC 9596-1:1998(en)". ISO. Retrieved 12 July 2024.

- ^ "ISO/IEC 9596-2:1993(en)". ISO. Retrieved 12 July 2024.

- ^ a b "Internetworking Technology Handbook – Internetworking Basics [Internetworking]". Cisco. 15 January 2014. Retrieved 14 August 2015.

- ^ "3GPP specification: 36.300". 3gpp.org. Retrieved 14 August 2015.

- ^ "Layering Considered Harmful". Some Internet Architectural Guidelines and Philosophy. December 2002. sec. 3. doi:10.17487/RFC3439. RFC 3439. Retrieved 25 April 2022.

- ^ Walter Goralski (2009). The Illustrated Network: How TCP/IP Works in a Modern Network (PDF). Morgan Kaufmann. p. 26. ISBN 978-0123745415.

- ^ a b c Tanenbaum, Andrew S. (2003). Computer networks. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall PTR. ISBN 978-0-13-066102-9. OCLC 50166590.

- ^ "OSI IS-IS Intra-domain Routing Protocol". IETF Datatracker. doi:10.17487/RFC1142. RFC 1142. Retrieved 12 July 2024.

Further reading

[edit]- Day, John D. (2008). Patterns in Network Architecture: A Return to Fundamentals. Upper Saddle River, N.J.: Pearson Education. ISBN 978-0-13-225242-3. OCLC 213482801.

- Dickson, Gary; Lloyd, Alan (1992). Open Systems Interconnection. New York: Prentice Hall. ISBN 978-0-13-640111-7. OCLC 1245634475 – via Internet Archive.

- Piscitello, David M.; Chapin, A. Lyman (1993). Open systems networking : TCP/IP and OSI. Reading, Mass.: Addison-Wesley Pub. Co. ISBN 978-0-201-56334-4. OCLC 624431223 – via Internet Archive.

- Rose, Marshall T. (1990). The Open Book: A Practical Perspective on OSI. Englewood Cliffs, N.J.: Prentice Hall. ISBN 978-0-13-643016-2. OCLC 1415988401 – via Internet Archive.

- Russell, Andrew L. (2014). Open Standards and the Digital Age: History, Ideology, and Networks. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-139-91661-5. OCLC 881237495. Partial preview at Google Books.

- Zimmermann, Hubert (April 1980). "OSI Reference Model — The ISO Model of Architecture for Open Systems Interconnection". IEEE Transactions on Communications. 28 (4): 425–432. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.136.9497. doi:10.1109/TCOM.1980.1094702. ISSN 0090-6778. OCLC 5858668034. S2CID 16013989.

External links

[edit]- "Windows network architecture and the OSI model". Microsoft Learn. 2 February 2024. Retrieved 12 July 2024.

- "ISO/IEC standard 7498-1:1994 - Service definition for the association control service element". ISO Standards Maintenance Portal. Retrieved 12 July 2024. (PDF document inside ZIP archive) (requires HTTP cookies in order to accept licence agreement)

- "ITU Recommendation X.200". International Telecommunication Union. 2 June 1998. Retrieved 12 July 2024.

- "INFormation CHanGe Architectures and Flow Charts powered by Google App Engine". infchg.appspot.com. Archived from the original on 26 May 2012.

- "Internetworking Technology Handbook". docwiki.cisco.com. 10 July 2015. Archived from the original on 6 September 2015.

- EdXD; Saikot, Mahmud Hasan (25 November 2021). "7 Layers of OSI Model Explained". ByteXD. Retrieved 12 July 2024.

OSI model

View on Grokipedia- Layer 1: Physical – Responsible for the transmission and reception of raw bit streams over a physical medium, such as cables or wireless signals, defining electrical, mechanical, and procedural specifications.[1]

- Layer 2: Data Link – Provides node-to-node data transfer, error detection and correction, and framing, using MAC addresses to manage access to the physical medium (e.g., Ethernet protocols).[2]

- Layer 3: Network – Manages logical addressing, routing, and forwarding of packets across multiple networks, enabling devices to find optimal paths (e.g., IP protocols like IPv4 and IPv6).[3]

- Layer 4: Transport – Ensures end-to-end delivery of data, including segmentation, flow control, and error recovery, with protocols like TCP for reliable transmission or UDP for faster, connectionless service.[1]

- Layer 5: Session – Establishes, maintains, and terminates communication sessions between applications, handling synchronization and dialog control for coordinated exchanges.[2]

- Layer 6: Presentation – Translates data between the application layer and the network, managing syntax, encryption, compression, and format conversion (e.g., converting data to ASCII or JPEG).[3]

- Layer 7: Application – Interfaces directly with end-user applications, providing network services such as file transfer, email, and web browsing (e.g., protocols like HTTP, SMTP, and FTP).[1]