Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

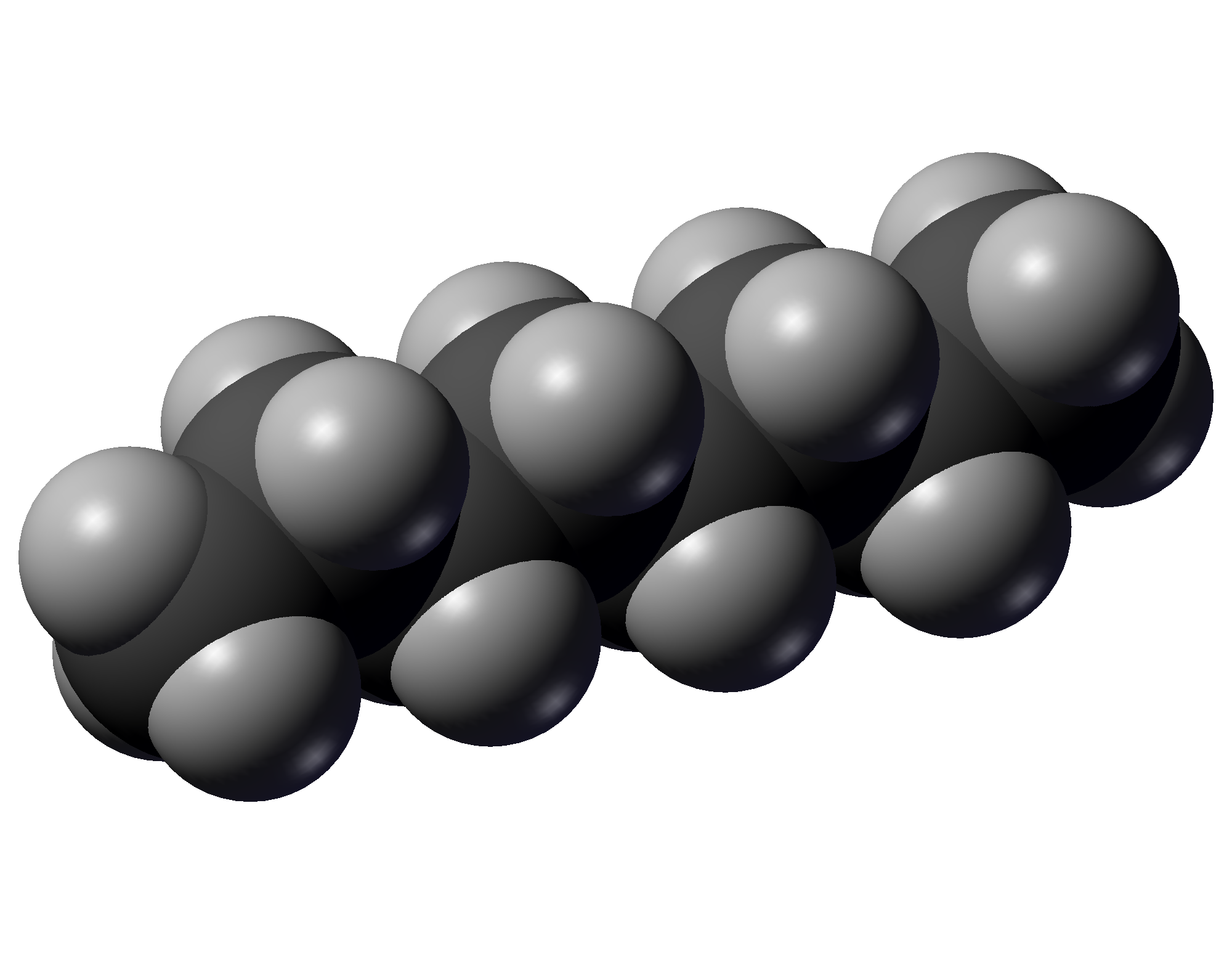

Octane

View on Wikipedia | |

| |

| |

| Names | |

|---|---|

| Systematic IUPAC name

Octane[1] | |

| Other names

n-Octane

| |

| Identifiers | |

3D model (JSmol)

|

|

| 1696875 | |

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| ChemSpider | |

| DrugBank | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.003.539 |

| EC Number |

|

| 82412 | |

| KEGG | |

| MeSH | octane |

PubChem CID

|

|

| RTECS number |

|

| UNII | |

| UN number | 1262 |

CompTox Dashboard (EPA)

|

|

| |

| |

| Properties | |

| CH3(CH2)6CH3 | |

| Molar mass | 114.232 g·mol−1 |

| Appearance | Colourless liquid |

| Odor | Gasoline-like[2] |

| Density | 0.703 g/cm3 |

| Melting point | −57.1 to −56.6 °C; −70.9 to −69.8 °F; 216.0 to 216.6 K |

| Boiling point | 125.1 to 126.1 °C; 257.1 to 258.9 °F; 398.2 to 399.2 K |

| 0.007 mg/dm3 (at 20 °C) | |

| log P | 4.783 |

| Vapor pressure | 1.47 kPa (at 20.0 °C) |

Henry's law

constant (kH) |

29 nmol/(Pa·kg) |

| Conjugate acid | Octonium |

| −96.63·10−6 cm3/mol | |

Refractive index (nD)

|

1.398 |

| Viscosity |

|

| Thermochemistry | |

Heat capacity (C)

|

255.68 J/(K·mol) |

Std molar

entropy (S⦵298) |

361.20 J/(K·mol) |

Std enthalpy of

formation (ΔfH⦵298) |

−252.1 to −248.5 kJ/mol |

Std enthalpy of

combustion (ΔcH⦵298) |

−5.53 to −5.33 MJ/mol |

| Hazards | |

| GHS labelling: | |

| |

| Danger | |

| H225, H304, H315, H336, H410 | |

| P210, P261, P273, P301+P310, P331 | |

| NFPA 704 (fire diamond) | |

| Flash point | 13.0 °C (55.4 °F; 286.1 K) |

| 220.0 °C (428.0 °F; 493.1 K) | |

| Explosive limits | 0.96 – 6.5% |

| Lethal dose or concentration (LD, LC): | |

LDLo (lowest published)

|

428 mg/kg (mouse, intravenous)[4] |

| NIOSH (US health exposure limits): | |

PEL (Permissible)

|

TWA 500 ppm (2350 mg/m3)[2] |

REL (Recommended)

|

TWA 75 ppm (350 mg/m3) C 385 ppm (1800 mg/m3) [15-minute][2] |

IDLH (Immediate danger)

|

1000 ppm[2] |

| Related compounds | |

Related alkanes

|

|

Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa).

| |

Octane is a hydrocarbon and also an alkane with the chemical formula C8H18, and the condensed structural formula CH3(CH2)6CH3. Octane has many structural isomers that differ by the location of branching in the carbon chain. One of these isomers, 2,2,4-trimethylpentane (commonly called iso-octane), is used as one of the standard values in the octane rating scale.

Octane is a component of gasoline and petroleum. Under standard temperature and pressure, octane is an odorless, colorless liquid. Like other short-chained alkanes with a low molecular weight, it is volatile, flammable, and toxic. Octane is 1.2 to 2 times more toxic than heptane.[5]

Isomers

[edit]N-octane has 23 constitutional isomers. 8 of these isomers have one stereocenter; 3 of them have two stereocenters.

Achiral isomers:

- 2-Methylheptane

- 4-Methylheptane

- 3-Ethylhexane

- 2,2-Dimethylhexane

- 2,5-Dimethylhexane

- (meso)-3,4-Dimethylhexane

- 3,3-Dimethylhexane

- 3-Ethyl-2-methylpentane

- 3-Ethyl-3-methylpentane

- 2,2,4-Trimethylpentane (i.e. iso-octane)

- 2,3,3-Trimethylpentane

- 2,3,4-Trimethylpentane

- 2,2,3,3-Tetramethylbutane

Chiral isomers:

Production and use

[edit]In petrochemistry, octanes are not typically differentiated or purified as specific compounds. Octanes are components of particular boiling fractions.[6]

A common route to such fractions is the alkylation reaction between iso-butane and 1-butene, which forms iso-octane.[7]

Octane is commonly used as a solvent in paints and adhesives.

References

[edit]- ^ "octane - Compound Summary". PubChem Compound. USA: National Center for Biotechnology Information. 16 September 2004. Identification and Related Records. Retrieved 6 January 2012.

- ^ a b c d NIOSH Pocket Guide to Chemical Hazards. "#0470". National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH).

- ^ Dymond, J. H.; Oye, H. A. (1994). "Viscosity of Selected Liquid n-Alkanes". Journal of Physical and Chemical Reference Data. 23 (1): 41–53. Bibcode:1994JPCRD..23...41D. doi:10.1063/1.555943. ISSN 0047-2689.

- ^ "Octane". Immediately Dangerous to Life or Health Concentrations (IDLH). National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH).

- ^ "1988 OSHA PEL Project - Octane | NIOSH | CDC". www.cdc.gov. 2020-02-27. Retrieved 2024-04-19.

- ^ "Fractionation". www.appliedcontrol.com. Retrieved 2024-04-19.

- ^ Ross, Julian (January 1986). "Ullmann's Encyclopedia of industrial chemistry". Applied Catalysis. 27 (2): 403–404. doi:10.1016/s0166-9834(00)82943-7. ISSN 0166-9834.

External links

[edit]- International Chemical Safety Card 0933

- NIOSH Pocket Guide to Chemical Hazards. "#0470". National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH).

- Dr. Duke's Phytochemical and Ethnobotanical Databases, Octane, [1]

Octane

View on GrokipediaChemical Identity and Properties

Molecular Structure and Formula

Octane is a saturated hydrocarbon belonging to the alkane series, characterized by the molecular formula .[1] This formula indicates a composition of eight carbon atoms and eighteen hydrogen atoms, with all carbon-carbon bonds being single covalent bonds, making it a paraffin hydrocarbon.[1] Alkanes like octane are also termed paraffins due to their low reactivity, derived from the Latin parum affinis, meaning "little affinity."/03%3A_Organic_Compounds-_Alkanes_and_Their_Stereochemistry/3.05%3A_Properties_of_Alkanes) The molecular weight of octane is 114.23 g/mol, calculated from its atomic composition.[1] Structurally, octane features an eight-carbon chain where the carbons are connected exclusively by single bonds, allowing for either straight-chain or branched configurations.[1] The straight-chain form, known as n-octane, has the condensed structural formula .[8] Under the International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry (IUPAC) nomenclature, the name "octane" specifically denotes the unbranched isomer, while common usage often employs "n-octane" to distinguish it from branched variants.[9] The term originates from the Latin octo, meaning "eight," highlighting the molecule's eight carbon atoms.[10] While multiple isomeric forms of exist, the foundational structure emphasizes its role as a prototypical alkane.[1]Physical Characteristics

n-Octane appears as a colorless, volatile liquid with a characteristic gasoline-like odor.[1][11] At standard room temperature (20°C), it exists in the liquid state, with a melting point of -56.8°C and a boiling point of 125.6°C.[12] Its density is 0.703 g/cm³ at 20°C, making it less dense than water and prone to floating on aqueous surfaces.[11] n-Octane exhibits low solubility in water, approximately 0.00066 g/L at 20°C, reflecting its nonpolar hydrocarbon nature.[1] In contrast, it is miscible with many organic solvents, including ethanol, acetone, benzene, and chloroform, facilitating its use in non-aqueous environments.[1] Additional optical and vapor properties include a refractive index of 1.397 at 20°C and a vapor pressure of 1.33 kPa at the same temperature, indicating moderate volatility under ambient conditions.[1] Thermodynamic characteristics encompass a heat of vaporization of 41.5 kJ/mol and a liquid heat capacity of 254 J/mol·K.[1][13]| Property | Value | Conditions | Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| Density | 0.703 g/cm³ | 20°C | CAMEO Chemicals |

| Vapor Pressure | 1.33 kPa | 20°C | PubChem |

| Refractive Index | 1.397 | 20°C | PubChem |

| Heat of Vaporization | 41.5 kJ/mol | 25°C | PubChem |

| Heat Capacity (liquid) | 254 J/mol·K | 25°C | NIST WebBook |

Chemical Reactivity

As a straight-chain alkane, n-octane exhibits general chemical inertness under standard conditions, showing no reactivity toward aqueous acids, bases, or common oxidizing agents due to the strength of its carbon-hydrogen and carbon-carbon bonds.[1][12] It is also resistant to hydrolysis, as it does not react with water and remains stable in aqueous environments.[1][12] One of the primary reactions of n-octane is combustion in the presence of oxygen, which proceeds exothermically to form carbon dioxide and water. The balanced equation for the complete combustion of liquid n-octane is: This reaction releases a standard enthalpy of combustion of -5470.3 kJ/mol, reflecting the high energy content of the molecule.[14][1] Under ultraviolet light, n-octane undergoes free radical halogenation, a substitution reaction where hydrogen atoms are replaced by halogens such as chlorine, yielding a mixture of chloro-octane isomers. This process involves initiation by homolytic cleavage of the halogen molecule, propagation through radical abstraction and addition steps, and termination by radical recombination, and is characteristic of alkanes due to the relative weakness of C-H bonds compared to other functional groups./Alkanes/Reactivity_of_Alkanes/Halogenation_of_Alkanes)[15] In industrial contexts, n-octane can be transformed through cracking and reforming processes to produce smaller hydrocarbons or higher-octane components. Thermal cracking involves high-temperature pyrolysis (typically 500–800°C) to break C-C bonds, generating alkenes, alkanes, and coke as byproducts, while catalytic reforming uses metal catalysts like platinum on alumina at 450–550°C to rearrange the structure into branched or aromatic compounds, enhancing fuel quality.[16][17][18] Despite its chemical stability, n-octane is highly flammable, with a flash point of 13°C and an autoignition temperature of 220°C, indicating ignition risk at relatively low temperatures in the presence of an ignition source.[1][19]Isomers

Constitutional Isomers

Constitutional isomers of octane, with the molecular formula C₈H₁₈, are compounds that share the same molecular formula but differ in the connectivity of their carbon atoms, resulting in variations in chain length, branching, and substituent positioning. These structural differences arise from different ways to arrange eight carbon atoms into acyclic alkane skeletons while maintaining the total of 18 hydrogen atoms.[20] There are exactly 18 constitutional isomers of octane, each representing a unique carbon skeleton.[21] The naming of these isomers follows the International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry (IUPAC) systematic conventions, where the parent chain is the longest continuous carbon chain, and branches are denoted as alkyl groups (e.g., methyl or ethyl) listed alphabetically with their locant numbers indicating attachment positions. Common names persist for some, such as n-octane for the linear chain and isooctane for the branched 2,2,4-trimethylpentane.[1] The complete list of constitutional isomers, with their IUPAC names and Chemical Abstracts Service (CAS) registry numbers, is presented below:| IUPAC Name | CAS Number |

|---|---|

| Octane | 111-65-9 |

| 2-Methylheptane | 592-27-8 |

| 3-Methylheptane | 589-81-1 |

| 4-Methylheptane | 589-53-7 |

| 2,2-Dimethylhexane | 590-73-8 |

| 2,3-Dimethylhexane | 584-94-1 |

| 2,4-Dimethylhexane | 589-43-5 |

| 2,5-Dimethylhexane | 592-13-2 |

| 3,3-Dimethylhexane | 563-16-6 |

| 3,4-Dimethylhexane | 583-48-2 |

| 3-Ethylhexane | 619-99-8 |

| 2,2,3-Trimethylpentane | 564-02-3 |

| 2,2,4-Trimethylpentane | 540-84-1 |

| 2,3,3-Trimethylpentane | 560-21-4 |

| 2,3,4-Trimethylpentane | 565-75-3 |

| 3-Ethyl-2-methylpentane | 609-26-7 |

| 3-Ethyl-3-methylpentane | 1067-08-9 |

| 2,2,3,3-Tetramethylbutane | 594-82-1 |