Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

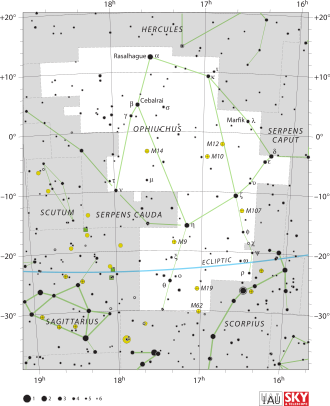

Ophiuchus

View on Wikipedia

| Constellation | |

| |

| Abbreviation | Oph |

|---|---|

| Genitive | Ophiuchi |

| Pronunciation | /ˌɒfiˈjuːkəs/ genitive: /ˌɒfiˈjuːkaɪ/ |

| Symbolism | the serpent-bearer |

| Right ascension | 17h |

| Declination | −8° |

| Quadrant | SQ3 |

| Area | 948 sq. deg. (11th) |

| Main stars | 10 |

| Bayer/Flamsteed stars | 65 |

| Stars brighter than 3.00m | 5 |

| Stars within 10.00 pc (32.62 ly) | 11 |

| Brightest star | α Oph (Rasalhague) (2.08m) |

| Nearest star | Barnard's Star |

| Messier objects | 7 |

| Meteor showers |

|

| Bordering constellations | |

| Visible at latitudes between +80° and −80°. Best visible at 21:00 (9 p.m.) during the month of July. | |

Ophiuchus (/ˌɒfiˈjuːkəs/) is a large constellation straddling the celestial equator. Its name comes from the Ancient Greek ὀφιοῦχος (ophioûkhos), meaning "serpent-bearer", and it is commonly represented as a man grasping a snake. The serpent is represented by the constellation Serpens. Ophiuchus was one of the 48 constellations listed by the 2nd-century astronomer Ptolemy, and it remains one of the 88 modern constellations. An old alternative name for the constellation was Serpentarius.[1]

Location

[edit]

Ophiuchus lies between Aquila, Serpens, Scorpius, Sagittarius, and Hercules, northwest of the center of the Milky Way. The southern part lies between Scorpius to the west and Sagittarius to the east.[2] In the Northern Hemisphere, it is best visible in summer.[3] It is opposite of Orion. Ophiuchus is depicted as a man grasping a serpent; the interposition of his body divides the snake constellation Serpens into two parts, Serpens Caput and Serpens Cauda. Ophiuchus straddles the equator with the majority of its area lying in the Southern Hemisphere. Rasalhague, its brightest star, lies near the northern edge of Ophiuchus at about +12° 30′ declination.[4] The constellation extends southward to −30° declination. Segments of the ecliptic within Ophiuchus are south of −20° declination (see chart at right).

In contrast to Orion, from November to January (summer in the Southern Hemisphere, winter in the Northern Hemisphere), Ophiuchus is in the daytime sky and thus not visible at most latitudes. However, for much of the polar region north of the Arctic Circle in the Northern Hemisphere's winter months, the Sun is below the horizon even at midday. Stars (and thus parts of Ophiuchus, especially Rasalhague) are then visible at twilight for a few hours around local noon, low in the south. In the Northern Hemisphere's spring and summer months, when Ophiuchus is normally visible in the night sky, the constellation is actually not visible, because the midnight sun obscures the stars at those times and places in the Arctic. In countries close to the equator, Ophiuchus appears overhead in June around midnight and in the October evening sky.[citation needed]

Features

[edit]Stars

[edit]The brightest stars in Ophiuchus include α Ophiuchi, called Rasalhague ("head of the serpent charmer"), at magnitude 2.07, and η Ophiuchi, known as Sabik ("the preceding one"), at magnitude 2.43.[5][6] Alpha Ophiuchi is composed of an A-type (bluish-white) giant star[7] and a K-type main sequence star.[8] The primary is a rapid rotator[9] with an inclined axis of rotation.[10] Eta Ophiuchi is a binary system.[11] Other bright stars in the constellation include β Ophiuchi, Cebalrai ("dog of the shepherd")[12] and λ Ophiuchi, or Marfik ("the elbow").[13] Beta Ophiuchi is an evolved red giant star that is slightly more massive than the Sun.[14][15] Lambda Ophiuchi is a binary star system with the primary being more massive and luminous than the Sun.[16][17]

RS Ophiuchi is part of a class called recurrent novae, whose brightness increase at irregular intervals by hundreds of times in a period of just a few days. It is thought to be at the brink of becoming a Type Ia supernova.[18] It erupts around every 15 years and usually has a magnitude of around 5.0 during eruptions, most recently in 2021.[19][20]

Barnard's Star, one of the nearest stars to the Solar System (the only stars closer are the Alpha Centauri binary star system and Proxima Centauri), lies in Ophiuchus. It is located to the left of β and just north of the V-shaped group of stars in an area that was once occupied by the now-obsolete constellation of Taurus Poniatovii (Poniatowski's Bull). It is thought that an exoplanet orbits around the star,[21] but later studies have refuted this claim.[22] In 1998, an intense flare was observed.[23][24] The star has also been a target of plans for interstellar travel such as Project Daedalus.[25][26] In 2005, astronomers using data from the Green Bank Telescope discovered a superbubble so large that it extends beyond the plane of the galaxy.[27] It is called the Ophiuchus Superbubble.

In April 2007, astronomers announced that the Swedish-built Odin satellite had made the first detection of clouds of molecular oxygen in space, following observations in the constellation Ophiuchus.[28] The supernova of 1604 was first observed on 9 October 1604, near θ Ophiuchi. Johannes Kepler saw it first on 16 October and studied it so extensively that the supernova was subsequently called Kepler's Supernova. He published his findings in a book titled De stella nova in pede Serpentarii (On the New Star in Ophiuchus's Foot). Galileo used its brief appearance to counter the Aristotelian dogma that the heavens are changeless. It was a Type Ia supernova[29] and the most recent Milky Way supernova visible to the unaided eye.[30] In 2009 it was announced that GJ 1214, a star in Ophiuchus, undergoes repeated, cyclical dimming with a period of about 1.5 days consistent with the transit of a small orbiting planet.[31] The planet's low density (about 40% that of Earth) suggests that the planet might have a substantial component of low-density gas—possibly hydrogen or steam.[32] The proximity of this star to Earth (42 light years) makes it a feasible target for further observations. The host star emits X-rays which could have removed mass from the exoplanet.[33] In April 2010, the naked-eye star ζ Ophiuchi was occulted by the asteroid 824 Anastasia.[34][35][36]

-

The constellation Ophiuchus as it can be seen by naked eye.[37]

-

Hercules and Ophiuchus, 1602, by Willem Blaeu.

-

Johannes Kepler's 1606 book De Stella Nova in Pede Serpentarii (On the New Star in Ophiuchus's Foot) opened at the page for Ophiuchus.

-

Detail showing the stella nova marked "N" in the right foot of Ophiuchus.

Deep-sky objects

[edit]

Ophiuchus contains several star clusters, such as IC 4665, NGC 6633, M9, M10, M12, M14, M19, M62, and M107, as well as the nebula IC 4603-4604.

M9 is a globular cluster which may have an extra-galactic origin.[38] M10 is a fairly close globular cluster, only 20,000 light-years from Earth. It has a magnitude of 6.6 and is a Shapley class VII cluster. This means that it has "intermediate" concentration; it is only somewhat concentrated towards its center.[39] M12 is a globular cluster which is around 5 kiloparsecs from the Solar System.[40] M14 is another globular cluster which is somewhat farther away.[41] Globular cluster M19 is oblate-shaped[42] with multiple different types of variable stars.[43] M62 is a globular cluster rich in variable stars such as RR Lyrae variables[44] and has two generations of stars with different element abundances.[45] M107 is also rich in variable stars.[46]

The unusual galaxy merger remnant and starburst galaxy NGC 6240 is also in Ophiuchus. At a distance of 400 million light-years, this "butterfly-shaped" galaxy has two supermassive black holes 3,000 light-years apart. Confirmation of the fact that both nuclei contain black holes was obtained by spectra from the Chandra X-ray Observatory. Astronomers estimate that the black holes will merge in another billion years. NGC 6240 also has an unusually high rate of star formation, classifying it as a starburst galaxy. This is likely due to the heat generated by the orbiting black holes and the aftermath of the collision.[47] Both have active galactic nuclei.[48]

In 2006, a new nearby star cluster was discovered associated with the 4th magnitude star Mu Ophiuchi.[49] The Mamajek 2 cluster appears to be a poor cluster remnant analogous to the Ursa Major Moving Group, but 7 times more distant (approximately 170 parsecs away). Mamajek 2 appears to have formed in the same star-forming complex as the NGC 2516 cluster roughly 135 million years ago.[50]

Barnard 68 is a large dark nebula, located 410 light-years from Earth. Despite its diameter of 0.4 light-years, Barnard 68 only has twice the mass of the Sun, making it both very diffuse and very cold, with a temperature of about 16 kelvins. Though it is currently stable, Barnard 68 will eventually collapse, inciting the process of star formation. One unusual feature of Barnard 68 is its vibrations, which have a period of 250,000 years. Astronomers speculate that this phenomenon is caused by the shock wave from a supernova.[47] Barnard 68 has blocked thousands of stars visible at other wavelengths[51] and the distribution of dust in Barnard 68 has been mapped.[52][53]

The space probe Voyager 1, the furthest man-made object from earth, is traveling in the direction of Ophiuchus. It is located between α Herculis, α Ophiuchi and κ Ophiuchi at right ascension 17h 13m and declination +12° 25’ (July 2020).[54]

In November 2022, the USA's NSF NOIRLab (National Optical-Infrared Astronomy Research Laboratory) announced the unambiguous identification of the nearest stellar black hole orbited by a G-type main-sequence star, the system identified as Gaia BH1 at around 1,560 light years from the Sun.[55]

History and mythology

[edit]There is no evidence of the constellation preceding the classical era, and in Babylonian astronomy, a "Sitting Gods" constellation seems to have been located in the general area of Ophiuchus. However, Gavin White proposes that Ophiuchus may in fact be remotely descended from this Babylonian constellation, representing Nirah, a serpent-god who was sometimes depicted with his upper half human but with serpents for legs.[56]

The earliest mention of the constellation is in Aratus, informed by the lost catalogue of Eudoxus of Cnidus (4th century BC):[57]

To the Phantom's back the Crown is near, but by his head mark near at hand the head of Ophiuchus, and then from it you can trace the starlit Ophiuchus himself: so brightly set beneath his head appear his gleaming shoulders. They would be clear to mark even at the midmonth moon, but his hands are not at all so bright; for faint runs the gleam of stars along on this side and on that. Yet they too can be seen, for they are not feeble. Both firmly clutch the Serpent, which encircles the waist of Ophiuchus, but he, steadfast with both his feet well set, tramples a huge monster, even the Scorpion, standing upright on his eye and breast. Now the Serpent is wreathed about his two hands – a little above his right hand, but in many folds high above his left.[58]

To the ancient Greeks, the constellation represented the god Apollo struggling with a huge snake that guarded the Oracle of Delphi.[59]

Later myths identified Ophiuchus with Laocoön, the Trojan priest of Poseidon, who warned his fellow Trojans about the Trojan Horse and was later slain by a pair of sea serpents sent by the gods to punish him.[59] According to Roman era mythography,[60] the figure represents the healer Asclepius, who learned the secrets of keeping death at bay after observing one serpent bringing another healing herbs. To prevent the entire human race from becoming immortal under Asclepius' care, Jupiter killed him with a bolt of lightning, but later placed his image in the heavens to honor his good works. In medieval Islamic astronomy (Azophi's Uranometry, 10th century), the constellation was known as Al-Ḥawwa', "the snake-charmer".[61]

Aratus describes Ophiuchus as trampling on Scorpius with his feet. This is depicted in Renaissance to Early Modern star charts, beginning with Albrecht Dürer in 1515; in some depictions (such as that of Johannes Kepler in De Stella Nova, 1606), Scorpius also seems to threaten to sting Serpentarius in the foot. This is consistent with Azophi, who already included ψ Oph and ω Oph as the snake-charmer's "left foot", and θ Oph and ο Oph as his "right foot", making Ophiuchus a zodiacal constellation at least as regards his feet.[62] This arrangement has been taken as symbolic in later literature and placed in relation to the words spoken by God to the serpent in the Garden of Eden (Genesis 3:15).[63]

-

Ophiuchus in a manuscript copy of Azophi's Uranometry, 18th century copy of a manuscript prepared for Ulugh Beg in 1417 (note that as in all pre-modern star charts, the constellation is mirrored, with Serpens Caput on the left and Serpens Cauda on the right).

-

Ophiuchus holding the serpent, Serpens, as depicted in Urania's Mirror, a set of constellation cards published in London c. 1825. Above the tail of the serpent is the now-obsolete constellation Taurus Poniatovii while below it is Scutum.

Zodiac

[edit]Ophiuchus is one of the 13 constellations that cross the ecliptic.[64] It has sometimes been suggested as the "13th sign of the zodiac". However, this confuses zodiac or astrological signs with constellations.[65] The signs of the zodiac are a 12-fold division of the ecliptic, so that each sign spans 30° of celestial longitude, approximately the distance the Sun travels in a month, and (in the Western tradition) are aligned with the seasons so that the March equinox always falls on the boundary between Pisces and Aries.[66][67] Constellations, on the other hand, are unequal in size and are based on the positions of the stars. The constellations of the zodiac have only a loose association with the signs of the zodiac, and do not in general coincide with them.[68] In Western astrology the constellation of Aquarius, for example, largely corresponds to the sign of Pisces. Similarly, the constellation of Ophiuchus occupies most (29 November – 18 December[69]) of the sign of Sagittarius (23 November – 21 December). The differences are due to the fact that the time of year that the Sun passes through a particular zodiac constellation's position has slowly changed (because of the precession of the Earth's rotational axis) over the millennia from when the Babylonians originally developed the zodiac.[70][71]

Citations

[edit]- ^ "Star Tales – Ophiuchus". Retrieved 25 June 2021.

- ^ Dickinson, Terence (2006). Nightwatch A practical Guide to Viewing the Universe Revised Fourth Edition: Updated for use Through 2025. US: Firefly Books. p. 185. ISBN 1-55407-147-X.

- ^ Dickinson, Terence (2006). Nightwatch A Practical Guide to Viewing the Universe Revised Fourth Edition: Updated for Use Through 2025. US: Firefly Books. pp. 44–59. ISBN 1-55407-147-X.

- ^ Ford, Dominic. "Rasalhague (Star)". in-the-sky.org. Retrieved 23 June 2018.

- ^ Chartrand III, Mark R.; (1983) Skyguide: A Field Guide for Amateur Astronomers, p. 170 (ISBN 0-307-13667-1).

- ^ Hoffleit, D.; Warren, W. H. Jr. (1991). "Entry for HR 2491". Bright Star Catalogue, 5th Revised Ed. (Preliminary Version). CDS. ID V/50.

- ^ Cowley, A.; et al. (April 1969), "A study of the bright A stars. I. A catalogue of spectral classifications", Astronomical Journal, 74: 375–406, Bibcode:1969AJ.....74..375C, doi:10.1086/110819

- ^ Hinkley, Sasha; et al. (January 2011), "Establishing α Oph as a Prototype Rotator: Improved Astrometric Orbit" (PDF), The Astrophysical Journal, 726 (2): 104, arXiv:1010.4028, Bibcode:2011ApJ...726..104H, doi:10.1088/0004-637X/726/2/104, S2CID 50830196

- ^ Monnier, J. D; Townsend, R. H. D; Che, X; Zhao, M; Kallinger, T; Matthews, J; Moffat, A. F. J (2010). "Rotationally Modulated g-modes in the Rapidly Rotating δ Scuti Star Rasalhague (α Ophiuchi)". The Astrophysical Journal. 725 (1): 1192–1201. arXiv:1012.0787. Bibcode:2010ApJ...725.1192M. doi:10.1088/0004-637X/725/1/1192. S2CID 51105576.

- ^ Zhao, M.; et al. (February 2010), Rivinius, Th.; Curé, M. (eds.), "Imaging and Modeling Rapid Rotators: α Cep and α Oph", The Interferometric View on Hot Stars, Revista Mexicana de Astronomía y Astrofísica, Serie de Conferencias, 38: 117–118, Bibcode:2010RMxAC..38..117Z

- ^ Docobo, J. A.; Ling, J. F. (April 2007), "Orbits and System Masses of 14 Visual Double Stars with Early-Type Components", The Astronomical Journal, 133 (4): 1209–1216, Bibcode:2007AJ....133.1209D, doi:10.1086/511070, S2CID 120821801

- ^ Paul Kunitzsch; Tim Smart (2006). A Dictionary of Modern Star Names: A Short Guide to 254 Star Names and Their Derivations. Sky Publishing Corporation. p. 44. ISBN 978-1-931559-44-7.

- ^ Chartrand, at p. 170.

- ^ Allende Prieto, C.; Lambert, D. L. (1999), "Fundamental parameters of nearby stars from the comparison with evolutionary calculations: masses, radii and effective temperatures", Astronomy and Astrophysics, 352: 555–562, arXiv:0809.0359, Bibcode:1999A&A...352..555A, doi:10.1051/0004-6361/200811242, S2CID 14531031

- ^ Soubiran, C.; et al. (2008), "Vertical distribution of Galactic disk stars. IV. AMR and AVR from clump giants", Astronomy and Astrophysics, 480 (1): 91–101, arXiv:0712.1370, Bibcode:2008A&A...480...91S, doi:10.1051/0004-6361:20078788, S2CID 16602121

- ^ Zorec, J.; et al. (2012). "Rotational velocities of A-type stars. IV. Evolution of rotational velocities". Astronomy and Astrophysics. 537: A120. arXiv:1201.2052. Bibcode:2012A&A...537A.120Z. doi:10.1051/0004-6361/201117691. S2CID 55586789.

- ^ Lastennet, E.; Fernandes, J.; Lejeune, Th. (June 2002). "A revised HRD for individual components of binary systems from BaSeL BVRI synthetic photometry. Influence of interstellar extinction and stellar rotation". Astronomy and Astrophysics. 388: 309–319. arXiv:astro-ph/0203341. Bibcode:2002A&A...388..309L. doi:10.1051/0004-6361:20020439. S2CID 14376211.

- ^ "Star 'soon to become supernova'". BBC News. 23 July 2006.

- ^ "[vsnet-alert 26131] Outburst of RS Ophiuchi". ooruri.kusastro.kyoto-u.ac.jp. Retrieved 9 August 2021.

- ^ "ATel #14834: Fermi-LAT Gamma-ray Detection of the Recurrent Nova RS Oph". ATel. Retrieved 9 August 2021.

- ^ Ribas, I.; Tuomi, M.; Reiners, Ansgar; Butler, R. P.; et al. (14 November 2018). "A candidate super-Earth planet orbiting near the snow line of Barnard's star" (PDF). Nature. 563 (7731). Holtzbrinck Publishing Group: 365–368. arXiv:1811.05955. Bibcode:2018Natur.563..365R. doi:10.1038/s41586-018-0677-y. hdl:2299/21132. ISSN 0028-0836. OCLC 716177853. PMID 30429552. S2CID 256769911. Archived (PDF) from the original on 26 March 2019.

- ^ Lubin, Jack; Robertson, Paul; Stefansson, Gudmundur; et al. (15 July 2021). "Stellar Activity Manifesting at a One-year Alias Explains Barnard b as a False Positive". The Astronomical Journal. 162 (2). American Astronomical Society: 61. arXiv:2105.07005. Bibcode:2021AJ....162...61L. doi:10.3847/1538-3881/ac0057. ISSN 0004-6256. S2CID 234741985.

- ^ Paulson, Diane B.; Allred, Joel C.; Anderson, Ryan B.; Hawley, Suzanne L.; Cochran, William D.; Yelda, Sylvana (2006). "Optical Spectroscopy of a Flare on Barnard's Star". Publications of the Astronomical Society of the Pacific. 118 (1): 227. arXiv:astro-ph/0511281. Bibcode:2006PASP..118..227P. doi:10.1086/499497. S2CID 17926580.

- ^ Benedict, G. Fritz; McArthur, Barbara; Nelan, E.; Story, D.; Whipple, A. L.; Shelus, P. J.; Jefferys, W. H.; Hemenway, P. D.; Franz, Otto G.; Wasserman, L. H.; Duncombe, R. L.; Van Altena, W.; Fredrick, L. W. (1998). "Photometry of Proxima Centauri and Barnard's star using Hubble Space Telescope fine guidance senso 3". The Astronomical Journal. 116 (1): 429. arXiv:astro-ph/9806276. Bibcode:1998AJ....116..429B. doi:10.1086/300420. S2CID 15880053.

- ^ Bond, A. & Martin, A. R. (1976). "Project Daedalus – The mission profile". Journal of the British Interplanetary Society. 9 (2): 101. Bibcode:1976JBIS...29..101B. Archived from the original on 20 October 2007. Retrieved 15 August 2006.

- ^ Darling, David (July 2005). "Daedalus, Project". The Encyclopedia of Astrobiology, Astronomy, and Spaceflight. Archived from the original on 31 August 2006. Retrieved 10 August 2006.

- ^ "Huge 'Superbubble' of Gas Blowing Out of Milky Way". PhysOrg.com. 13 January 2006. Retrieved 4 July 2008.

- ^ "Molecular Oxygen Detected for the First Time in the Interstellar Medium". Retrieved 28 September 2016.

- ^ Reynolds, S. P.; Borkowski, K. J.; Hwang, U.; Hughes, J. P.; Badenes, C.; Laming, J. M.; Blondin, J. M. (2 October 2007). "A Deep Chandra Observation of Kepler's Supernova Remnant: A Type Ia Event with Circumstellar Interaction". The Astrophysical Journal. 668 (2): L135 – L138. arXiv:0708.3858. Bibcode:2007ApJ...668L.135R. doi:10.1086/522830.

- ^ "Kepler's Supernova: Recently Observed Supernova". Universe for Facts. Archived from the original on 4 January 2019. Retrieved 21 December 2014.

- ^ Charbonneau, David; et al. (December 2009). "A super-Earth transiting a nearby low-mass star". Nature. 462 (7275): 891–894. arXiv:0912.3229. Bibcode:2009Natur.462..891C. doi:10.1038/nature08679. PMID 20016595. S2CID 4360404.

- ^ Rogers, Leslie A.; Seager, Sara (2010). "Three Possible Origins for the Gas Layer on GJ 1214b". The Astrophysical Journal. 716 (2): 1208–1216. arXiv:0912.3243. Bibcode:2010ApJ...716.1208R. doi:10.1088/0004-637x/716/2/1208. S2CID 15288792.

- ^ Lalitha, S.; et al. (July 2014). "X-Ray Emission from the Super-Earth Host GJ 1214". The Astrophysical Journal Letters. 790 (1): 5. arXiv:1407.2741. Bibcode:2014ApJ...790L..11L. doi:10.1088/2041-8205/790/1/L11. S2CID 118774018. L11.

- ^ "Asteroid To Hide Naked-Eye Star". 31 March 2010. Retrieved 17 July 2019.

- ^ "Asteroid To Hide Bright Star". 31 March 2010. Retrieved 17 July 2019.

- ^ "(824) Anastasia / HIP 81377 event on 2010 Apr 06, 10:21 UT". Archived from the original on 17 July 2019. Retrieved 17 July 2019.

- ^ "Ophiuchus, the Serpent Bearer – Constellations – Digital Images of the Sky". allthesky.com.

- ^ Arellano Ferro, A.; et al. (September 2013), "A detailed census of variable stars in the globular cluster NGC 6333 (M9) from CCD differential photometry", Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society, 434 (2): 1220–1238, arXiv:1306.3206, Bibcode:2013MNRAS.434.1220A, doi:10.1093/mnras/stt1080.

- ^ Levy 2005, pp. 153–54.

- ^ Gontcharov, George A.; Khovritchev, Maxim Yu; Mosenkov, Aleksandr V.; Il'In, Vladimir B.; Marchuk, Alexander A.; Savchenko, Sergey S.; Smirnov, Anton A.; Usachev, Pavel A.; Poliakov, Denis M. (2021). "Isochrone fitting of Galactic globular clusters – III. NGC 288, NGC 362, and NGC 6218 (M12)". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. 508 (2): 2688–2705. arXiv:2109.13115. doi:10.1093/mnras/stab2756.

- ^ Boyles, J.; et al. (November 2011), "Young Radio Pulsars in Galactic Globular Clusters", The Astrophysical Journal, 742 (1): 51, arXiv:1108.4402, Bibcode:2011ApJ...742...51B, doi:10.1088/0004-637X/742/1/51, S2CID 118649860.

- ^ Burnham, Robert (1978), Burnham's Celestial Handbook: An Observer's Guide to the Universe Beyond the Solar System, Dover Books on Astronomy, vol. 2 (2nd ed.), Courier Dover Publications, p. 1263, ISBN 978-0486235684.

- ^ Clement, Christine M.; et al. (November 2001), "Variable Stars in Galactic Globular Clusters", The Astronomical Journal, 122 (5): 2587–2599, arXiv:astro-ph/0108024, Bibcode:2001AJ....122.2587C, doi:10.1086/323719, S2CID 38359010.

- ^ Contreras, R.; et al. (December 2010), "Time-series Photometry of Globular Clusters: M62 (NGC 6266), the Most RR Lyrae-rich Globular Cluster in the Galaxy?", The Astronomical Journal, 140 (6): 1766–1786, arXiv:1009.4206, Bibcode:2010AJ....140.1766C, doi:10.1088/0004-6256/140/6/1766, S2CID 118515997

- ^ Milone, A. P. (January 2015), "Helium and multiple populations in the massive globular cluster NGC 6266 (M 62)", Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society, 446 (2): 1672–1684, arXiv:1409.7230, Bibcode:2015MNRAS.446.1672M, doi:10.1093/mnras/stu2198.

- ^ McCombs, Thayne; et al. (January 2013), "Variable Stars in the Globular Cluster M107: The Discovery of a Probable SX Phoenicis", AAS Meeting #221, vol. 221, American Astronomical Society, p. 250.22, Bibcode:2013AAS...22125022M, 250.22.

- ^ a b Wilkins, Jamie; Dunn, Robert (2006). 300 Astronomical Objects: A Visual Reference to the Universe. Buffalo, New York: Firefly Books. ISBN 978-1-55407-175-3.

- ^ Komossa, Stefanie; Burwitz, Vadim; Hasinger, Guenther; Predehl, Peter; et al. (2003). "Discovery of a Binary Active Galactic Nucleus in the Ultraluminous Infrared Galaxy NGC 6240 Using Chandra". Astrophysical Journal. 582 (1): L15 – L19. arXiv:astro-ph/0212099. Bibcode:2003ApJ...582L..15K. doi:10.1086/346145. S2CID 16697327.

- ^ Mamajek, Eric E. (2006). "A New Nearby Candidate Star Cluster in Ophiuchus at d = 170 pc". Astronomical Journal. 132 (5): 2198–2205. arXiv:astro-ph/0609064. Bibcode:2006AJ....132.2198M. doi:10.1086/508205. S2CID 14070978.

- ^ Jilinski, Evgueni; Ortega, Vladimir G.; de la Reza, Jorge Ramiro; Drake, Natalia A. & Bazzanella, Bruno (2009). "Dynamical Evolution and Spectral Characteristics of the Stellar Group Mamajek 2". The Astrophysical Journal. 691 (1): 212–218. arXiv:0810.1198. Bibcode:2009ApJ...691..212J. doi:10.1088/0004-637X/691/1/212. S2CID 15570695.

- ^ "The Dark Cloud B68 at Different Wavelengths". European Southern Observatory. Retrieved 30 January 2012.

- ^ Alves, João; Lada, Charles; Lada, Elizabeth (March 2001). "Seeing the light through the dark" (PDF). The Messenger. 103: 15–20. Bibcode:2001Msngr.103....1A.

- ^ Alves, João F.; Lada, Charles J.; Lada, Elizabeth A. (January 2001). "Internal structure of a cold dark molecular cloud inferred from the extinction of background starlight". Nature. 409 (6817): 159–161. Bibcode:2001Natur.409..159A. doi:10.1038/35051509. PMID 11196632. S2CID 4318459.

- ^ Coordinates available at The Sky Live.

- ^ Astronomers Discover Closest Black Hole to Earth Gemini North telescope on Hawai‘i reveals first dormant, stellar-mass black hole in our cosmic backyard, Dr Kareem El-Badry et al, USA National Science Foundation NOIRLab (National Optical-Infrared Astronomy Research Laboratory), 2022-11-04

- ^ White, Gavin; Babylonian Star-lore, Solaria Pubs, 2008, p. 187f

- ^ Liddell, Henry George; Scott, Robert. "ὀφιοῦχος". A Greek-English Lexicon. perseus.tufts.edu.

- ^ translation by Mair, Alexander W.; & Mair, Gilbert R.; Loeb Classical Library, volume 129, William Heinemann, London, 1921 theoi.com

- ^ a b Thompson, Robert (2007). Illustrated Guide to Astronomical Wonders: From Novice to Master Observer. O'Reilly Media, Inc. p. 326. ISBN 9780596526856.

- ^ Hyginus, Astronomica 2, 14, Latin Mythography, 2nd century AD

- ^ "Snake-Charmer". Brickthology. Retrieved 1 February 2022.

- ^ "Manuscript reproduction". Archived from the original on 6 May 2019. Retrieved 17 July 2019.

- ^ Maunder, Edward Walter; Astronomy of the Bible, 1908, p. 164f

- ^ Shapiro, Lee T. "Constellations in the zodiac", in The Space Place (NASA, last updated 22 July 2011)

- ^ "Ophiuchus, 13th constellation of zodiac". Earth Sky. Retrieved 19 July 2019.

- ^ Gleason, Edward. "Why is the vernal equinox called the "First Point of Aries" when the Sun is actually in Pisces on this date? | Planetarium". University of Southern Maine. Retrieved 25 March 2022.

- ^ Campbell, Tina (15 July 2020). "Has your star sign changed following the discovery of a 'new' Zodiac sign?". Metro. Retrieved 29 April 2021.

- ^ "Ophiuchus – a 13th Zodiac Sign? No!". Astrology Club. 2 March 2016. Retrieved 18 October 2016.

- ^ "Born under the sign of Ophiuchus?". EarthSky.org. 16 August 2021.

- ^ Aitken, Robert G. (October 1942). "Edmund Halley and Stellar Proper Motions". Astronomical Society of the Pacific Leaflets. 4 (164): 103. Bibcode:1942ASPL....4..103A.

- ^ Redd, Nola Taylor. "Constellations: The Zodiac Constellation Names". space.com. Retrieved 3 August 2012.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- Levy, David H. (2005). Deep Sky Objects. Prometheus Books. ISBN 1-59102-361-0.

- Ridpath, Ian; and Tirion, Wil; (2007) Stars and Planets Guide, Collins, London; ISBN 978-0-00-725120-9, Princeton University Press, Princeton; ISBN 978-0-691-13556-4

![The constellation Ophiuchus as it can be seen by naked eye.[37]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/66/OphiuchusCC.jpg/250px-OphiuchusCC.jpg)