Recent from talks

Contribute something

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Polyvinyl chloride

View on Wikipedia

| |

| |

Pure PVC powder, containing no plasticizer

| |

| Names | |

|---|---|

| IUPAC name

poly(1-chloroethylene)[1]

| |

| Other names

Polychloroethene

| |

| Identifiers | |

| Abbreviations | PVC |

| ChEBI | |

| ChemSpider |

|

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.120.191 |

| KEGG | |

| MeSH | Polyvinyl+Chloride |

CompTox Dashboard (EPA)

|

|

| Properties | |

| (C2H3Cl)n[2] | |

| Appearance | white, brittle solid |

| Odor | odorless |

| Density | 1.4 g/cm3 |

| Melting point | 100 °C (212 °F) to 260 °C (500 °F)[3] |

| insoluble | |

| Solubility in ethanol | insoluble |

| Solubility in tetrahydrofuran | slightly soluble |

| −10.71×10−6 (SI, 22 °C)[4] | |

| Hazards | |

| NFPA 704 (fire diamond) | |

Threshold limit value (TLV)

|

10 mg/m3 (inhalable), 3 mg/m3 (respirable) (TWA) |

| NIOSH (US health exposure limits):[5] | |

PEL (Permissible)

|

15 mg/m3 (inhalable), 5 mg/m3 (respirable) (TWA) |

Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa).

| |

Polyvinyl chloride (alternatively: poly(vinyl chloride),[6][7] colloquial: vinyl[8] or polyvinyl; abbreviated: PVC[8]) is the world's third-most widely produced synthetic polymer of plastic (after polyethylene and polypropylene). About 40 million tons of PVC are produced each year.[9]

PVC comes in rigid (sometimes abbreviated as RPVC) and flexible forms. Rigid PVC is used in construction for pipes, doors and windows. It is also used in making plastic bottles, packaging, and bank or membership cards. Adding plasticizers makes PVC softer and more flexible. It is used in plumbing, electrical cable insulation, flooring, signage, phonograph records, inflatable products, and in rubber substitutes.[10] With cotton or linen, it is used in the production of canvas.

Polyvinyl chloride is a white, brittle solid. It is soluble in ketones, chlorinated solvents, dimethylformamide, THF and DMAc.[11]

Discovery

[edit]PVC was synthesized in 1872 by German chemist Eugen Baumann after extended investigation and experimentation.[12] The polymer appeared as a white solid inside a flask of vinyl chloride that had been left on a shelf sheltered from sunlight for four weeks. In the early 20th century, the Russian chemist Ivan Ostromislensky and Fritz Klatte of the German chemical company Griesheim-Elektron both attempted to use PVC in commercial products, but difficulties in processing the rigid, sometimes brittle polymer thwarted their efforts. Waldo Semon and the B.F. Goodrich Company developed a method in 1926 to plasticize PVC by blending it with various additives,[13] including the use of dibutyl phthalate by 1933.[14]

Production

[edit]Polyvinyl chloride is produced by polymerization of the vinyl chloride monomer (VCM), as shown.[15]

|

About 80% of production involves suspension polymerization. Emulsion polymerization accounts for about 12%, and bulk polymerization accounts for 8%. Suspension polymerization produces particles with average diameters of 100–180 μm, whereas emulsion polymerization gives much smaller particles of average size around 0.2 μm. VCM and water are introduced into the reactor along with a polymerization initiator and other additives. The contents of the reaction vessel are pressurized and continually mixed to maintain the suspension and ensure a uniform particle size of the PVC resin. The reaction is exothermic and thus requires cooling. As the volume is reduced during the reaction (PVC is denser than VCM), water is continually added to the mixture to maintain the suspension.[9]

PVC may be manufactured from ethylene, which can be produced from either naphtha or ethane feedstock.[16]

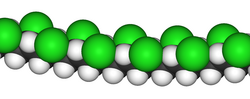

Microstructure

[edit]The polymers are linear and are strong. The monomers are mainly arranged head-to-tail, meaning that chloride is located on alternating carbon centres. PVC has mainly an atactic stereochemistry, which means that the relative stereochemistry of the chloride centres are random. Some degree of syndiotacticity of the chain gives a few percent crystallinity that is influential on the properties of the material. About 57% of the mass of PVC is chlorine. The presence of chloride groups gives the polymer very different properties from the structurally related material polyethylene.[17] At 1.4 g/cm3, PVC's density is also higher than structurally related plastics such as polyethylene (0.88–0.96 g/cm3) and polymethylmethacrylate (1.18 g/cm3).

Producers

[edit]About half of the world's PVC production capacity is in China, despite the closure of many Chinese PVC plants due to issues complying with environmental regulations and poor capacities of scale. The largest single producer of PVC as of 2018 is Shin-Etsu Chemical of Japan, with a global share of around 30%.[16]

Additives

[edit]The product of the polymerization process is unmodified PVC. Before PVC can be made into finished products, it always requires conversion into a compound by the incorporation of additives (but not necessarily all of the following) such as heat stabilizers, UV stabilizers, plasticizers, processing aids, impact modifiers, thermal modifiers, fillers, flame retardants, biocides, blowing agents and smoke suppressors, and, optionally, pigments.[18] The choice of additives used for the PVC finished product is controlled by the cost performance requirements of the end use specification (underground pipe, window frames, intravenous tubing and flooring all have very different ingredients to suit their performance requirements). Previously, polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs) were added to certain PVC products as flame retardants and stabilizers.[19]

Plasticizers

[edit]Among the common plastics, PVC is unique in its acceptance of large amounts of plasticizer with gradual changes in physical properties from a rigid solid to a soft gel,[20] and almost 90% of all plasticizer production is used in making flexible PVC.[21][22] The majority is used in films and cable sheathing.[23] Flexible PVC can consist of over 85% plasticizer by mass, however unplasticized PVC (UPVC) should not contain any.[24]

| Plasticizer content (% DINP by weight) | Specific gravity (20 °C) | Shore hardness (type A, 15 s) |

Flexural stiffness (Mpa) | Tensile strength (Mpa) | Elongation at break (%) | Example applications | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rigid | 0 | 1.4 | 900 | 41 | <15 | Unplasticized PVC (UPVC): window frames and sills, doors, rigid pipe | |

| Semi-rigid | 25 | 1.26 | 94 | 69 | 31 | 225 | Vinyl flooring, flexible pipe, thin films (stretch wrap), advertising banners |

| Flexible | 33 | 1.22 | 84 | 12 | 21 | 295 | Wire and cable insulation, flexible pipe |

| Very Flexible | 44 | 1.17 | 66 | 3.4 | 14 | 400 | Boots and clothing, inflatables, |

| Extremely Flexible | 86 | 1.02 | < 10 | Fishing lures (soft plastic bait), polymer clay, plastisol inks |

Phthalates

[edit]

The most common class of plasticizers used in PVC is phthalates, which are diesters of phthalic acid. Phthalates can be categorized as high and low, depending on their molecular weight. Low phthalates such as Bis(2-ethylhexyl) phthalate (DEHP) and Dibutyl phthalate (DBP) have increased health risks and are generally being phased out. High-molecular-weight phthalates such as diisononyl phthalate (DINP) and diisodecyl phthalate (DIDP) are generally considered safer.[22]

While DEHP has been medically approved for many years for use in medical devices, it was permanently banned for use in children's products in the US in 2008 by US Congress;[25] the PVC-DEHP combination had proved to be very suitable for making blood bags because DEHP stabilizes red blood cells, minimizing hemolysis (red blood cell rupture). However, DEHP is coming under increasing pressure in Europe. The assessment of potential risks related to phthalates, and in particular the use of DEHP in PVC medical devices, was subject to scientific and policy review by the European Union authorities, and on 21 March 2010, a specific labeling requirement was introduced across the EU for all devices containing phthalates that are classified as CMR (carcinogenic, mutagenic or toxic to reproduction).[26] The label aims to enable healthcare professionals to use this equipment safely, and, where needed, take appropriate precautionary measures for patients at risk of over-exposure.[27]

Metal stabilizers

[edit]BaZn stabilisers have successfully replaced cadmium-based stabilisers in Europe in many PVC semi-rigid and flexible applications.[28]

In Europe, particularly Belgium, there has been a commitment to eliminate the use of cadmium (previously used as a part component of heat stabilizers in window profiles) and phase out lead-based heat stabilizers (as used in pipe and profile areas) such as liquid autodiachromate and calcium polyhydrocummate by 2015. According to the final report of Vinyl 2010,[29] cadmium was eliminated across Europe by 2007. The progressive substitution of lead-based stabilizers is also confirmed in the same document showing a reduction of 75% since 2000 and ongoing. This is confirmed by the corresponding growth in calcium-based stabilizers, used as an alternative to lead-based stabilizers, more and more, also outside Europe.[9]

Heat stabilizers

[edit]Some of the most crucial additives are heat stabilizers. These agents minimize loss of HCl, a degradation process that starts above 70 °C (158 °F) and is autocatalytic. Many diverse agents have been used including, traditionally, derivatives of heavy metals (lead, cadmium). Metallic soaps (metal "salts" of fatty acids such as calcium stearate) are common in flexible PVC applications.[9]

Properties

[edit]PVC is a thermoplastic polymer. Its properties are usually categorized based on rigid and flexible PVCs.[30]

| Property | Unit of measurement | Rigid PVC | Flexible PVC |

|---|---|---|---|

| Density[31] | g/cm3 | 1.3–1.45 | 1.1–1.35 |

| Thermal conductivity[32] | W/(m·K) | 0.14–0.28 | 0.14–0.17 |

| Yield strength[31] | psi | 4,500–8,700 | 1,450–3,600 |

| MPa | 31–60 | 10.0–24.8 | |

| Young's modulus[33] | psi | 490,000 | — |

| GPa | 3.4 | — | |

| Flexural strength (yield)[33] | psi | 10,500 | — |

| MPa | 72 | — | |

| Compression strength[33] | psi | 9,500 | — |

| MPa | 66 | — | |

| Coefficient of thermal expansion (linear)[33] | mm/(mm °C) | 5×10−5 | — |

| Vicat B[32] | °C | 65–100 | Not recommended |

| Resistivity[a][34] | Ω m | 1016 | 1012–1015 |

| Surface resistivity[a][34] | Ω | 1013–1014 | 1011–1012 |

- Notes

Thermal and fire

[edit]The heat stability of raw PVC is very poor, so the addition of a heat stabilizer during the process is necessary in order to ensure the product's properties. Traditional product PVC has a maximum operating temperature around 60 °C (140 °F) when heat distortion begins to occur.[35]

As a thermoplastic, PVC has an inherent insulation that aids in reducing condensation formation and resisting internal temperature changes for hot and cold liquids.[35]

Applications

[edit]

Pipes

[edit]Roughly half of the world's PVC resin manufactured annually is used for producing pipes for municipal and industrial applications.[36] In the private homeowner market, it accounts for 66% of the household market in the US, and in household sanitary sewer pipe applications, it accounts for 75%.[37][38] Buried PVC pipes in both water and sanitary sewer applications that are 100 mm (4 in) in diameter and larger are typically joined by means of a gasket-sealed joint. The most common type of gasket utilized in North America is a metal-reinforced elastomer, commonly referred to as a Rieber sealing system.[39]

Electric cables

[edit]PVC is often used as the insulating sheath on electrical cables. PVC is chosen because of its good electrical insulation, ease of extrusion, and resistance to burn.[40]

In a fire, PVC can form hydrogen chloride fumes; the chlorine serves to scavenge free radicals, making PVC-coated wires fire retardant. While hydrogen chloride fumes can also pose a health hazard in their own right, it dissolves in moisture and breaks down onto surfaces, particularly in areas where the air is cool enough to breathe, so would not be inhaled.[41]

Construction

[edit]

PVC is widely and heavily used in construction and building industry,[9] For example, vinyl siding is used extensively as a popular low-maintenance material, particularly in Ireland, the United Kingdom, the United States, and Canada. The material comes in a range of colors and finishes, including a photo-effect wood finish, and is used as a substitute for painted wood, mostly for window frames and sills when installing insulated glazing in new buildings; or to replace older single-glazed windows, as it does not decompose and is weather-resistant. Other uses include fascia, and siding or weatherboarding. This material has almost entirely replaced the use of cast iron for plumbing and drainage, being used for waste pipes, drainpipes, gutters and downspouts. PVC is known as having strong resistance against chemicals, sunlight, and oxidation from water.[42]

Signage and graphics

[edit]Polyvinyl chloride is formed in flat sheets in a variety of thicknesses and colors. As flat sheets, PVC is often expanded to create voids in the interior of the material, providing additional thickness without additional weight and minimal extra cost (see closed-cell PVC foamboard). Sheets are cut using saws and rotary cutting equipment.

Plasticized PVC is also used to produce thin, colored, or clear, adhesive-backed films referred to simply as "vinyl". These films are typically cut on a computer-controlled plotter (see vinyl cutter) or printed in a wide-format printer. These sheets and films are used to produce a wide variety of commercial signage products, vinyl wraps or racing stripes on vehicles for aesthetics or as wrap advertising, and general purpose stickers.[43]

Clothing

[edit]

PVC fabric is water-resistant, used for its weather-resistant qualities in coats, skiing equipment, shoes, jackets, and aprons.[44] The shoulders of donkey jackets are traditionally made out of PVC. Early high visibility clothing was also made of PVC

Healthcare

[edit]The two main application areas for single-use medically approved PVC compounds are flexible containers and tubing: containers used for blood and blood components, for urine collection or for ostomy products and tubing used for blood taking and blood giving sets, catheters, heart-lung bypass sets, hemodialysis sets etc. In Europe the consumption of PVC from medical devices is approximately 85,000 tons each year. Almost one third of plastic-based medical devices are made from PVC.[45]

Food packaging

[edit]PVC has been applied to various items such as: bottles,[46] packaging films,[46] blister packs,[46] cling wraps,[46] and seals on metal lids.

Wire rope

[edit]PVC may be extruded under pressure to encase wire rope and aircraft cable used for general purpose applications. PVC coated wire rope is easier to handle, resists corrosion and abrasion, and may be color-coded for increased visibility. It is found in a variety of industries and environments both indoor and out.[47]

Other uses

[edit]

Molded PVC is used to produce phonograph, or "vinyl", records. PVC piping is a cheaper alternative to metal tubing used in musical instrument making; it is therefore a common alternative when making wind instruments, often for leisure or for rarer instruments such as the contrabass flute. An instrument that is almost exclusively built from PVC tube is the thongophone, a percussion instrument that is played by slapping the open tubes with a flip-flop or similar.[48] PVC is also used as a raw material in automotive underbody coating.[49]

Chlorinated PVC

[edit]PVC can be usefully modified by chlorination, which increases its chlorine content to or above 67%. Chlorinated polyvinyl chloride, (CPVC), as it is called, is produced by chlorination of aqueous solution of suspension PVC particles followed by exposure to UV light which initiates the free-radical chlorination.[9]

Adhesives

[edit]Flexible plasticized PVC can be glued with special adhesives often referred to as solvent cement as solvents are the main ingredients.[50] PVC or polyurethane resin may be added to increase viscosity, allow the adhesive to fill gaps, to accelerate setting and to reduce shrinkage and internal stresses.[51] Viscosity can be further increased by adding fumed silica as a filler. As molecules are mobilized by the solvents and migrating PVC polymers are interlinking at the joint the process is also referred to as welding or cold welding. PVC can be made with a variety of plasticizers. Plasticizer migration from the vinyl part into the adhesive can degrade the strength of the joint. If this is of concern the adhesives should be tested for their resistance to the plasticizer. Nitrile rubber adhesives are often used with flexible PVC film as they are known to be resistant to plasticizers. Some epoxy adhesive formulations have provide good adhesion to flexible PVC substrate.[52] Typical formulations of common solvent cement may contain 10–50% ethyl acetate, 8–16% acetone, 12–50% butanone (methyl ethyl ketone, MEK), 0–18% methyl acetate, 12–30% polyurethane and 0-10% toluene.[53][54] Alternatively methyl isobutyl ketone or tetrahydrofuran may be added as solvents, tin organic compounds as stabilizer and dioctylphthalate as a plasticizer.[55]

Health and safety

[edit]Plasticizers

[edit]Phthalates, which are incorporated into plastics as plasticizers, comprise approximately 70% of the US plasticizer market; phthalates are by design not covalently bound to the polymer matrix, which makes them highly susceptible to leaching. Phthalates are contained in plastics at high percentages. For example, they can contribute up to 40% by weight to intravenous medical bags and up to 80% by weight in medical tubing.[56] Vinyl products are pervasive—including toys,[57] car interiors, shower curtains, and flooring—and initially release chemical gases into the air. Some studies indicate that this outgassing of additives may contribute to health complications, and have resulted in a call for banning the use of DEHP on shower curtains, among other uses.[58]

In 2004 a joint Swedish-Danish research team found a statistical association between allergies in children and indoor air levels of DEHP and BBzP (butyl benzyl phthalate), which is used in vinyl flooring.[59] In December 2006, the European Chemicals Bureau of the European Commission released a final draft risk assessment of BBzP which found "no concern" for consumer exposure including exposure to children.[60]

Lead

[edit]Lead compounds had previously been widely added to PVC to improve workability and stability but have been shown to leach into drinking water from PVC pipes.[61]

In Europe the use of lead-based stabilizers has been discontinued. The VinylPlus voluntary commitment which began in 2000, saw European Stabiliser Producers Association (ESPA) members complete the replacement of Pb-based stabilisers in 2015.[62][63]

Vinyl chloride monomer

[edit]In the early 1970s, the carcinogenicity of vinyl chloride (usually called vinyl chloride monomer or VCM) was linked to cancers in workers in the polyvinyl chloride industry. Specifically workers in polymerization section of a B.F. Goodrich plant near Louisville, Kentucky, were diagnosed with liver angiosarcoma also known as hemangiosarcoma, a rare disease.[64] Since that time, studies of PVC workers in Australia, Italy, Germany, and the UK have all associated certain types of occupational cancers with exposure to vinyl chloride, and it has become accepted that VCM is a carcinogen.[9]

Combustion

[edit]PVC produces HCl, water and carbon dioxide upon combustion.

Dioxins

[edit]Studies of household waste burning indicate consistent increases in dioxin generation with increasing PVC concentrations.[65] According to the U.S. EPA dioxin inventory, landfill fires are likely to represent an even larger source of dioxin to the environment. A survey of international studies consistently identifies high dioxin concentrations in areas affected by open waste burning and a study that looked at the homologue pattern found the sample with the highest dioxin concentration was "typical for the pyrolysis of PVC". Other EU studies indicate that PVC likely "accounts for the overwhelming majority of chlorine that is available for dioxin formation during landfill fires."[65]

The next largest sources of dioxin in the U.S. EPA inventory are medical and municipal waste incinerators.[66] Various studies have been conducted that reach contradictory results. For instance a study of commercial-scale incinerators showed no relationship between the PVC content of the waste and dioxin emissions.[67][68] Other studies have shown a clear correlation between dioxin formation and chloride content and indicate that PVC is a significant contributor to the formation of both dioxin and PCB in incinerators.[69][70][71]

In February 2007, the Technical and Scientific Advisory Committee of the US Green Building Council (USGBC) released its report on a PVC avoidance related materials credit for the LEED Green Building Rating system. The report concludes that "no single material shows up as the best across all the human health and environmental impact categories, nor as the worst" but that the "risk of dioxin emissions puts PVC consistently among the worst materials for human health impacts."[72]

In Europe the overwhelming importance of combustion conditions on dioxin formation has been established by numerous researchers. The single most important factor in forming dioxin-like compounds is the temperature of the combustion gases. Oxygen concentration also plays a major role on dioxin formation, but not the chlorine content.[73]

Several studies have also shown that removing PVC from waste would not significantly reduce the quantity of dioxins emitted. The EU Commission published in July 2000 a Green Paper on the Environmental Issues of PVC"[74]

A study commissioned by the European Commission on "Life Cycle Assessment of PVC and of principal competing materials" states that "Recent studies show that the presence of PVC has no significant effect on the amount of dioxins released through incineration of plastic waste."[75]

Industry initiatives

[edit]In Europe, developments in PVC waste management have been monitored by Vinyl 2010,[76] established in 2000. Vinyl 2010's objective was to recycle 200,000 tonnes of post-consumer PVC waste per year in Europe by the end of 2010, excluding waste streams already subject to other or more specific legislation (such as the European Directives on End-of-Life Vehicles, Packaging and Waste Electric and Electronic Equipment).[77]

Since June 2011, it is followed by VinylPlus, a new set of targets for sustainable development.[78] Its main target is to recycle 800,000 tonnes per year of PVC by 2020 including 100,000 tonnes of "difficult to recycle" waste. One facilitator for collection and recycling of PVC waste is Recovinyl. The reported and audited mechanically recycled PVC tonnage in 2016 was 568,695 tonnes which in 2018 had increased to 739,525 tonnes.[79]

One approach to address the problem of waste PVC is also through the process called Vinyloop. It is a mechanical recycling process using a solvent to separate PVC from other materials. This solvent turns in a closed loop process in which the solvent is recycled. Recycled PVC is used in place of virgin PVC in various applications: coatings for swimming pools, shoe soles, hoses, diaphragms tunnel, coated fabrics, PVC sheets.[80] This recycled PVC's primary energy demand is 46 percent lower than conventional produced PVC. So the use of recycled material leads to a significant better ecological footprint. The global warming potential is 39 percent lower.[81]

Restrictions

[edit]In November 2005, one of the largest hospital networks in the US, Catholic Healthcare West, signed a contract with B. Braun Melsungen for vinyl-free intravenous bags and tubing.[82]

In January 2012, a major US West Coast healthcare provider, Kaiser Permanente, announced that it will no longer buy intravenous (IV) medical equipment made with PVC and DEHP-type plasticizers.[83]

In 1998, the U.S. Consumer Product Safety Commission (CPSC) arrived at a voluntary agreement with manufacturers to remove phthalates from PVC rattles, teethers, baby bottle nipples and pacifiers.[84]

Vinyl gloves in medicine

[edit]

Plasticized PVC is a common material for medical gloves. Due to vinyl gloves having less flexibility and elasticity, several guidelines recommend either latex or nitrile gloves for clinical care and procedures that require manual dexterity or that involve patient contact for more than a brief period. Vinyl gloves show poor resistance to many chemicals, including glutaraldehyde-based products and alcohols used in formulation of disinfectants for swabbing down work surfaces or in hand rubs. The additives in PVC are also known to cause skin reactions such as allergic contact dermatitis. These are for example the antioxidant bisphenol A, the biocide benzisothiazolinone, propylene glycol/adipate polyester and ethylhexylmaleate.[85]

Sustainability

[edit]According to Vinyl 2010, the life cycle, sustainability, and appropriateness of PVC have been extensively discussed and addressed within the PVC industry.[86][87] In Europe, a 2021 VinylPlus Progress Report indicated that 731,461 tonnes PVC were recycled in 2020, a 5% reduction compared to 2019 due to the COVID-19 pandemic.[88]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]General references

[edit]- Titow, W. (1984). PVC Technology. London: Elsevier Applied Science Publishers. ISBN 978-0-85334-249-6.

- Richard F. Grossman: Handbook of Vinyl Formulating (pdf-document), Second Edition, Wiley 2008

Inline citations

[edit]- ^ "poly(vinyl chloride) (CHEBI:53243)". CHEBI. Archived from the original on 13 December 2013. Retrieved 12 July 2012.

- ^ "Substance Details CAS Registry Number: 9002-86-2". Commonchemistry. CAS. Archived from the original on 21 May 2018. Retrieved 12 July 2012.

- ^ Wilkes, Charles E.; Summers, James W.; Daniels, Charles Anthony; Berard, Mark T. (2005). PVC Handbook. Hanser Verlag. p. 414. ISBN 978-1-56990-379-7. Archived from the original on 17 November 2016. Retrieved 24 September 2016.

- ^ Wapler, M. C.; Leupold, J.; Dragonu, I.; von Elverfeldt, D.; Zaitsev, M.; Wallrabe, U. (2014). "Magnetic properties of materials for MR engineering, micro-MR and beyond". JMR. 242: 233–242. arXiv:1403.4760. Bibcode:2014JMagR.242..233W. doi:10.1016/j.jmr.2014.02.005. PMID 24705364. S2CID 11545416.

- ^ "Material Safety Data Sheet: PVC Compounds Pellet and Powder" (PDF). Georgia Gulf Chemical and Vinyls LLC. Archived (PDF) from the original on 17 August 2021. Retrieved 23 July 2021.

- ^ "Poly(vinyl chloride)". www.sigmaaldrich.com. Archived from the original on 11 October 2022. Retrieved 21 September 2025.

- ^ "Poly(Vinyl Chloride)". www.pslc.ws. Retrieved 21 September 2025.

- ^ a b "About PVC - ECVM". ECVM. Archived from the original on 5 December 2023. Retrieved 21 September 2025.

- ^ a b c d e f g Allsopp, M. W.; Vianello, G. (2012). "Poly(Vinyl Chloride)". Ullmann's Encyclopedia of Industrial Chemistry. Weinheim: Wiley-VCH. doi:10.1002/14356007.a21_717. ISBN 978-3-527-30673-2.

- ^ W. V. Titow (31 December 1984). PVC technology. Springer. pp. 6–. ISBN 978-0-85334-249-6. Archived from the original on 26 May 2013. Retrieved 6 October 2011.

- ^ Grause, Guido; Hirahashi, Suguru; Toyoda, Hiroshi; Kameda, Tomohito; Yoshioka, Toshiaki (2017). "Solubility parameters for determining optimal solvents for separating PVC from PVC-coated PET fibers". Journal of Material Cycles and Waste Management. 19 (2): 612–622. Bibcode:2017JMCWM..19..612G. doi:10.1007/s10163-015-0457-9.

- ^ Baumann, E. (1872) "Ueber einige Vinylverbindungen" Archived 17 November 2016 at the Wayback Machine (On some vinyl compounds), Annalen der Chemie und Pharmacie, 163 : 308–322.

- ^ Semon, Waldo L.; Stahl, G. Allan (April 1981). "History of Vinyl Chloride Polymers". Journal of Macromolecular Science: Part A - Chemistry. 15 (6): 1263–1278. doi:10.1080/00222338108066464.

- ^ US 1929453, Waldo Semon, "Synthetic rubber-like composition and method of making same", published 10 October 1933, assigned to B.F. Goodrich Archived 26 April 2022 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Chanda, Manas; Roy, Salil K. (2006). Plastics technology handbook. CRC Press. pp. 1–6. ISBN 978-0-8493-7039-7.

- ^ a b "Shin-Etsu Chemical to build $1.4bn polyvinyl chloride plant in US". Nikkei Asian Review. Archived from the original on 24 July 2018. Retrieved 21 September 2025.

- ^ Handbook of Plastics, Elastomers, and Composites, Fourth Edition, 2002 by The McGraw-Hill, Charles A. Harper Editor-in-Chief. ISBN 0-07-138476-6

- ^ David F. Cadogan and Christopher J. Howick "Plasticizers" in Ullmann's Encyclopedia of Industrial Chemistry 2000, Wiley-VCH, Weinheim. doi:10.1002/14356007.a20_439

- ^ Karlen, Kaley. "Health Concerns and Environmental Issues with PVC-Containing Building Materials in Green Buildings" (PDF). Integrated Waste Management Board. California Environmental Protection Agency, US. Archived (PDF) from the original on 5 February 2016. Retrieved 26 August 2015.

- ^ Krauskopf, Leonard G. (2009). "3.13 Plasticizers". Plastics additives handbook (6. ed.). Munich: Carl Hanser Verlag. pp. 485–511. ISBN 978-3-446-40801-2.

- ^ David F. Cadogan and Christopher J. Howick "Plasticizers" in Ullmann's Encyclopedia of Industrial Chemistry 2000, Wiley-VCH, Weinheim. doi:10.1002/14356007.a20_439

- ^ a b "Plasticisers factsheets - Plasticisers - Information Center". Plasticisers - Information Center. Archived from the original on 9 February 2022. Retrieved 21 September 2025.

- ^ "Market Report Plasticizers until 2032 - Global". Ceresana Market Research. Retrieved 21 September 2025.

- ^ a b Krauskopf, L. G. (2009). Plastics additives handbook (6. ed.). Munich: Carl Hanser Verlag. p. 495. ISBN 978-3-446-40801-2.

- ^ "Phthalates and DEHP". Health Care Without Harm. 29 April 2013. Archived from the original on 30 June 2014. Retrieved 23 July 2021.

- ^ "Opinion on The safety of medical devices containing DEHP plasticized PVC or other plasticizers on neonates and other groups possibly at risk (2015 update)" (PDF). ec.europa.eu. Archived from the original (PDF) on 3 February 2016. Retrieved 21 September 2025.

- ^ "You searched for DEHP - Plasticisers - Information Center". Plasticisers - Information Center. Archived from the original on 9 February 2022. Retrieved 21 September 2025.

- ^ "Stabilisers.eu - Liquid stabilisers". www.stabilisers.eu. Archived from the original on 26 July 2015. Retrieved 21 September 2025.

- ^ "Vinyl 2010" (PDF). www.vinylplus.eu. Archived from the original (PDF) on 19 May 2014. Retrieved 21 September 2025.

- ^ Titow 1984, p. 62

- ^ a b Titow 1984, p. 1186.

- ^ a b Titow 1984, p. 1191.

- ^ a b c d Titow 1984, p. 857.

- ^ a b Titow 1984, p. 1194.

- ^ a b Michael A. Joyce, Michael D. Joyce (2004). Residential Construction Academy: Plumbing. Cengage Learning. pp. 63–64.

- ^ Rahman, Shah (19–20 June 2007). PVC Pipe & Fittings: Underground Solutions for Water and Sewer Systems in North America (PDF). 2nd Brazilian PVC Congress, Sao Paulo, Brazil. Archived from the original (PDF) on 9 July 2015. Retrieved 28 February 2009.

- ^ "Vinyl in Design". vinylbydesign.com. Archived from the original on 22 August 2007. Retrieved 21 September 2025.

- ^ Rahman, Shah (October 2004). "Thermoplastics at Work: A Comprehensive Review of Municipal PVC Piping Products" (PDF). Underground Construction: 56–61. Archived from the original on 7 August 2020. Retrieved 5 February 2019.

- ^ Shah Rahman (April 2007). "Sealing Our Buried Lifelines" (PDF). Opflow. 33 (4): 12–17. Bibcode:2007Opflo..33d..12R. doi:10.1002/j.1551-8701.2007.tb02753.x. Archived (PDF) from the original on 8 October 2011. Retrieved 30 March 2010.

- ^ Titow 1984, p. 717 PVC coating of wire and cable

- ^ Galloway FM, Hirschler MM, Smith GF (1992). "Surface parameters from small-scale experiments used for measuring HCl transport and decay in fire atmospheres". Fire Mater. 15 (4): 181–189. doi:10.1002/fam.810150405.

- ^ Strong, A. Brent (2005) Plastics: Materials and Processing. Prentice Hall. pp. 36–37, 68–72. ISBN 0131145584.

- ^ "Vinyl: An Honest Conversation And 7 Sustainable Alternatives". Green Dot Sign®. Archived from the original on 28 January 2021. Retrieved 21 September 2025.

- ^ "PVC POLY VINYL CHLORIDE PLASTICS". www.blue-growth.org. Retrieved 14 May 2025.

- ^ "PVC Healthcare Applications | PVC Med Alliance". www.pvcmed.org. Archived from the original on 7 June 2015. Retrieved 21 September 2025.

- ^ a b c d Marsh, Kenneth; Bigusu, Betty (31 March 2007). "Food Packaging – Roles, Materials, and Environmental Issues". Journal of Food Science. 72 (3): R43. doi:10.1111/j.1750-3841.2007.00301.x. ISSN 1750-3841. PMID 17995809.

- ^ "Coated Aircraft Cable & Wire Rope | Lexco Cable". www.lexcocable.com. Archived from the original on 26 August 2017. Retrieved 21 September 2025.

- ^ "Building a PVC Instrument - NateTrue.com". devices.natetrue.com. Archived from the original on 4 July 2015. Retrieved 21 September 2025.

- ^ Takata, Ayumi; Ohashi, Yutaka (2002). "Post PVC Sound Insulating Underbody coating". SAE Technical Paper Series. Vol. 1. doi:10.4271/2002-01-0293.

- ^ "Intro To Solvent Welding Plastic - Homemades". NerfHaven. Retrieved 21 September 2025.

- ^ Sina Ebnesajjad: Adhesives Technology Handbook (Second Edition), Chapter 9 - Solvent Cementing of Plastics, William Andrew Publishing, 2009, Pages 209-229, ISBN 9780815515333, https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-8155-1533-3.50012-8.

- ^ Edward M. Petrie: Epoxy Adhesive Formulations (pdf-document), p. 387, McGraw-Hill, 2006. 0-07-158908-2, DOI: 10.1036/0071455442

- ^ Manfred Dr. Beck, Horst Dr. Müller-Albrecht, Heinrich Dr. Königshofen: Adhesive mixture, C08G18/10, "Prepolymer processes involving reaction of isocyanates or isothiocyanates with compounds having active hydrogen in a first reaction step". Patent EP0277359A1, European Patent Office. Application EP19870119219 filed by Bayer AG 1987. Publication date 1988-08-10.

Patent claim:The adhesive mixture comprises A) 20 - 99 parts by weight of a soluble polyurethane, B) 0 - 50 parts by weight of a vinylaromatic-diene block polymer, C) 0.5 - 50 parts by weight of a modified vinylaromatic-diene polymer and D) 0 - 10 parts by weight of a polyisocyanate, if desired dissolved in an organic solvent

- ^ "Chemical Forums: Vinyl Glue?". www.chemicalforums.com. Retrieved 21 September 2025.

- ^ Waleed Khalid: Solvent Cement For Bonding Flexible PVC. In: scribd.com

- ^ Halden, Rolf U. (2010). "Plastics and Health Risks". Annual Review of Public Health. 31 (1): 179–194. doi:10.1146/annurev.publhealth.012809.103714. PMID 20070188.

- ^ "Directive 2005/84/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council 14 December 2005" (PDF). eur-lex.europa.eu. Archived from the original (PDF) on 4 May 2013. Retrieved 21 September 2025.

- ^ Service, Canwest News. "Vinyl shower curtains a 'volatile' hazard, study says". www.canada.com. Archived from the original on 4 September 2010. Retrieved 21 September 2025.

- ^ Bornehag, Carl-Gustaf; Sundell, Jan; Weschler, Charles J.; Sigsgaard, Torben; Lundgren, Björn; Hasselgren, Mikael; Hägerhed-Engman, Linda; et al. (2004). "The Association between Asthma and Allergic Symptoms in Children and Phthalates in House Dust: A Nested Case–Control Study". Environmental Health Perspectives. 112 (14): 1393–1397. Bibcode:2004EnvHP.112.1393B. doi:10.1289/ehp.7187. PMC 1247566. PMID 15471731.

- ^ "Phthalate Information Center Blog: More good news from Europe". blog.phthalates.org. Archived from the original on 2 June 2008. Retrieved 21 September 2025.

- ^ "China's PVC pipe makers under pressure to give up lead stabilizers". 6 September 2013.

- ^ "Lead replacement". European Stabiliser Producers Association. Archived from the original on 5 December 2018. Retrieved 5 December 2018.

- ^ "VinylPlus Progress Report 2016" (PDF). VinylPlus. 30 April 2016. Archived (PDF) from the original on 20 December 2016.

- ^ Creech, J. L. Jr.; Johnson, M. N. (March 1974). "Angiosarcoma of liver in the manufacture of polyvinyl chloride". Journal of Occupational Medicine. 16 (3): 150–1. PMID 4856325.

- ^ a b Costner, Pat (2005). "Estimating Releases and Prioritizing Sources in the Context of the Stockholm Convention"" (PDF). www.pops.int. Archived from the original (PDF) on 27 September 2007. Retrieved 21 September 2025.

- ^ Beychok, M.R. (1987). "A data base of dioxin and furan emissions from municipal refuse incinerators". Atmospheric Environment. 21 (1): 29–36. Bibcode:1987AtmEn..21...29B. doi:10.1016/0004-6981(87)90267-8.

- ^ National Renewable Energy Laboratory, Polyvinyl Chloride Plastics in Municipal Solid Waste Combustion Archived 15 February 2013 at the Wayback Machine NREL/TP-430- 5518, Golden CO, April 1993

- ^ Rigo, H. G.; Chandler, A. J.; Lanier, W.S. (1995). The Relationship between Chlorine in Waste Streams and Dioxin Emissions from Waste Combustor Stacks (PDF). Vol. 36. New York, NY: American Society of Mechanical Engineers. ISBN 978-0-7918-1222-8. Archived from the original (PDF) on 7 April 2016. Retrieved 31 October 2009.

{{cite book}}:|journal=ignored (help) - ^ Katami, Takeo; Yasuhara, Akio; Okuda, Toshikazu; Shibamoto, Takayuki; et al. (2002). "Formation of PCDDs, PCDFs, and Coplanar PCBs from Polyvinyl Chloride during Combustion in an Incinerator". Environ. Sci. Technol. 36 (6): 1320–1324. Bibcode:2002EnST...36.1320K. doi:10.1021/es0109904. PMID 11944687.

- ^ Wagner, J.; Green, A. (1993). "Correlation of chlorinated organic compound emissions from incineration with chlorinated organic input". Chemosphere. 26 (11): 2039–2054. Bibcode:1993Chmsp..26.2039W. doi:10.1016/0045-6535(93)90030-9.

- ^ Thornton, Joe (2002). Environmental Impacts of polyvinyl Chloride Building Materials (PDF). Washington, DC: Healthy Building Network. ISBN 978-0-9724632-0-1. Archived from the original (PDF) on 20 September 2013. Retrieved 6 October 2011.

- ^ "USGBC TSAC PVC - PharosWiki". www.pharosproject.net. Archived from the original on 2 June 2008. Retrieved 21 September 2025.

- ^ Wikstrom, Evalena; G. Lofvenius; C. Rappe; S. Marklund (1996). "Influence of Level and Form of Chlorine on the Formation of Chlorinated Dioxins, Dibenzofurans, and Benzenes during Combustion of an Artificial Fuel in a Laboratory Reactor". Environmental Science & Technology. 30 (5): 1637–1644. Bibcode:1996EnST...30.1637W. doi:10.1021/es9506364.

- ^ Environmental issues of PVC Archived 12 May 2012 at the Wayback Machine. European Commission. Brussels, 26 July 2000

- ^ Life Cycle Assessment of PVC and of principal competing materials Commissioned by the European Commission. European Commission (July 2004), p. 96

- ^ "Vinyl 2010". www.vinyl2010.org. Archived from the original on 25 July 2013. Retrieved 21 September 2025.

- ^ Griffiths, Martyn (22 July 2007). "Vinyl 2010: an effective partnership in the area of industrial development" (PDF). United Nations. Retrieved 1 June 2025.

The aim of Vinyl 2010 is to recycle 200,000 tonnes of post-consumer PVC per year by 2010, excluding waste covered by other legislation such as end-of-life vehicles, packaging, and WEEE.

- ^ "VinylPlus - Our Voluntary Commitment". www.vinylplus.eu. Archived from the original on 20 November 2014. Retrieved 21 September 2025.

- ^ "VinylPlus Progress Report 2019" (PDF). vinylplus.eu. Archived from the original (PDF) on 14 February 2020. Retrieved 21 September 2025.

- ^ S.A., SOLVAY. "VinyLoop Home". www.solvayplastics.com. Archived from the original on 1 January 2012. Retrieved 21 September 2025.

- ^ Solvay, asking more from chemistry Archived 16 May 2016 at the Portuguese Web Archive. Solvayplastics.com (15 July 2013). Retrieved on 28 January 2016.

- ^ "CHW Switches to PVC/DEHP-Free Products to Improve Patient Safety and Protect the Environment; Healthcare Provider Awards $70 Million Contract to B. Braun for PVC/DEHP-Free Supplies | Business Wire". www.businesswire.com. Archived from the original on 9 April 2016. Retrieved 21 September 2025.

- ^ "Kaiser Permanente bans PVC tubing and bags | PlasticsToday.com". www.plasticstoday.com. Archived from the original on 10 November 2015. Retrieved 21 September 2025.

- ^ "PVC Policies Across the World". chej.org. Archived from the original on 10 August 2017. Retrieved 25 August 2017.

- ^ "Vinyl Gloves: Causes For Concern" (PDF). Ansell (glove manufacturer). Archived from the original (PDF) on 22 September 2015. Retrieved 17 November 2015.

- ^ "London 2012 Use of PVC Policy" (PDF). learninglegacy.independent.gov.uk. Archived from the original (PDF) on 1 February 2016. Retrieved 21 September 2025.

- ^ Vinyl 2010 (22 May 2008). "Vinyl 2010 Progress Report 2008" (PDF). Stabilisers.eu. Retrieved 1 June 2025.

Vinyl 2010 is also becoming more and more of a reference point on material and product sustainability for the whole of the PVC industry, providing guidelines and sharing knowledge and best practices.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ "VinylPlus at a Glance 2021 - VinylPlus". VinylPlus. Archived from the original on 7 February 2022. Retrieved 21 September 2025.

External links

[edit]Polyvinyl chloride

View on GrokipediaHistory

Discovery and Early Research

In 1835, French chemist Henri Victor Regnault synthesized vinyl chloride by reacting ethylene with chlorine gas and observed its polymerization into a solid white substance when exposed to sunlight, marking the first recorded instance of polyvinyl chloride (PVC) formation.[12] This accidental discovery occurred during experiments aimed at characterizing the monomer, with sunlight acting as an initiator for the free radical polymerization mechanism, where vinyl chloride molecules link via carbon-carbon bonds to form long polymer chains.[13] Regnault noted the product's insolubility in common solvents but did not pursue further applications or mechanistic details, as the brittle, powdery material proved challenging to handle.[14] Nearly four decades later, in 1872, German chemist Eugen Baumann independently observed PVC formation under similar conditions, finding a white solid residue inside a glass flask containing vinyl chloride gas exposed to sunlight.[15] Baumann's experiments confirmed Regnault's earlier finding, attributing the polymerization to photochemical initiation that generates radicals capable of propagating chain growth, though the process yielded inconsistent, brittle polymers unsuitable for practical use due to poor thermal stability and processability.[16] These observations highlighted the radical nature of the reaction—initiated by light-induced homolytic cleavage of the monomer—but lacked control over molecular weight or microstructure, resulting in materials that degraded or discolored easily.[13] Early 20th-century research advanced these findings when German chemist Fritz Klatte developed a more deliberate polymerization method, patenting in 1913 a process using sunlight or chemical initiators like peroxides to polymerize vinyl chloride under controlled conditions.[13] Klatte's approach emphasized peroxide-induced free radical initiation, which decomposes to form radicals that add to vinyl chloride monomers, propagating chains until termination, though the resulting PVC remained a hard, brittle resin difficult to shape without additives.[17] This work laid groundwork for understanding PVC's atactic microstructure, where irregular chloride placements along the chain contributed to its rigidity and limited solubility, underscoring the need for empirical refinement of reaction parameters like temperature and initiator concentration.[18]Commercialization and Expansion

In 1926, Waldo L. Semon, a chemist at B.F. Goodrich Company, began experimenting with polyvinyl chloride (PVC) while attempting to develop an adhesive for bonding rubber to metal, leading to the accidental discovery of plasticized PVC through the addition of solvents like tricresyl phosphate, which rendered the brittle polymer flexible and commercially viable.[19] By 1933, Semon and B.F. Goodrich had patented formulations blending PVC with additives such as phthalates, enabling its use in early applications like flexible tubing and coated fabrics, marking the shift from laboratory material to initial industrial product.[20] Concurrently, Union Carbide pioneered commercial production of vinyl chloride monomer in 1929 and PVC resin (branded Vinylite) in 1931, establishing the first large-scale manufacturing processes and supplying the material for emerging markets in coatings and adhesives. Prior to World War II, PVC remained a niche material due to processing challenges and competition from natural rubber, but wartime shortages of rubber catalyzed rapid adoption as a substitute in applications such as wire insulation, cable coverings, and waterproof gear for military equipment, including U.S. Navy ships.[21] This demand surge prompted U.S. production increases in the early 1940s, with PVC's chemical resistance, flame retardancy, and lower cost relative to scarce natural alternatives driving its entrenchment in defense sectors and laying groundwork for postwar scalability.[22][23] Following the war, PVC underwent explosive commercialization, with production volumes expanding dramatically in the 1950s as new facilities proliferated globally and formulations improved versatility for consumer and construction uses, outpacing alternatives through economic advantages like abundance of raw materials (chlorine and ethylene) and adaptability via additives.[24] By the 1970s, annual global output had reached millions of metric tons, fueled by infrastructure booms and replacement of costlier materials in piping, flooring, and packaging, solidifying PVC's role as an industrial staple despite early scalability hurdles.[25]Chemical Structure and Synthesis

Vinyl Chloride Monomer

Vinyl chloride monomer (VCM), chemically denoted as H₂C=CHCl or C₂H₃Cl, is a colorless gas at standard temperature and pressure, with a molecular weight of 62.5 g/mol and a boiling point of -13.4 °C.[26][27] It possesses a mild, sweet odor detectable at concentrations above 3000 ppm and is highly flammable, with a lower explosive limit of 3.6% and an upper limit of 33% in air.[28][29] The compound's vinyl functionality renders it reactive, particularly susceptible to addition reactions and polymerization under appropriate conditions, though it remains stable under controlled storage below 0 °C.[30][31] Industrial synthesis of VCM predominantly employs the ethylene route, which integrates direct chlorination of ethylene with oxygen-based oxychlorination to produce 1,2-dichloroethane (EDC) intermediate, followed by thermal pyrolysis of EDC at 500–550 °C to yield VCM and regenerate HCl for recycling.[32] This balanced process, commercialized on a large scale starting in 1958, achieved dominance by the 1970s due to its efficiency in utilizing chlorine byproducts and lower raw material costs compared to alternatives.[33] An older method, acetylene hydrochlorination (C₂H₂ + HCl → H₂C=CHCl), catalyzed by mercuric chloride, was widely used prior to the ethylene shift but represented less than 5% of global capacity by 2000 owing to acetylene's expense and catalyst toxicity.[34] Production historically relied on mercury-containing catalysts in the acetylene process, prompting regulatory phase-outs; for instance, the European Union mandated cessation by January 1, 2022, under Regulation (EU) 2017/852, while global efforts under the Minamata Convention on Mercury target elimination in VCM manufacturing.[35][36] Cleaner alternatives, such as gold- or platinum-based catalysts for residual acetylene routes, have been developed to comply with these restrictions, particularly in regions like China where legacy processes persisted into the 2010s.[37] VCM is classified as a Group 1 carcinogen by the International Agency for Research on Cancer, with sufficient evidence linking occupational exposure to angiosarcoma of the liver, first documented in clusters among polymerization workers in the 1970s at exposure levels exceeding 1000 ppm.[38][39] The mechanism involves metabolic bioactivation to reactive epoxides that damage hepatic DNA, also associating with hepatocellular carcinoma at cumulative doses above 1000 ppm-years.[8] Current occupational exposure limits, enforced by the U.S. Occupational Safety and Health Administration, restrict averages to 1 ppm over 8 hours and peaks to 5 ppm over 15 minutes, reducing incidence through engineering controls and monitoring.[40][41]Polymerization Mechanisms

Polyvinyl chloride (PVC) is produced via free-radical chain-growth polymerization of vinyl chloride monomer (VCM), involving initiation, propagation, and termination steps.[42] In the initiation phase, organic peroxides such as lauroyl peroxide or azo compounds like azobisisobutyronitrile decompose thermally at temperatures between 40°C and 70°C to generate primary radicals, which abstract a chlorine atom or add directly to the VCM double bond, forming a monomer radical.[43] Propagation proceeds through successive addition of VCM molecules to the growing radical chain, primarily in a head-to-tail fashion, resulting in the characteristic -CH2-CHCl- repeating unit.[44] The free-radical mechanism yields predominantly atactic PVC, lacking stereoregular configuration due to the non-selective addition at the chiral carbon, leading to an amorphous microstructure.[44] Termination occurs via radical combination or disproportionation, limiting chain length.[42] Molecular weight is controlled primarily by polymerization temperature and initiator concentration; higher temperatures accelerate radical decomposition and termination rates relative to propagation, reducing average molecular weight (Mw), while lower temperatures favor longer chains.[43] This mechanism is implemented in suspension, emulsion, bulk, or solution processes, with free-radical initiation common across variants to minimize branching through initiator selection that avoids allylic radicals.[45] Suspension polymerization, dispersing VCM droplets in water, produces porous beads suitable for further processing, though the core kinetics remain governed by radical addition.[44]Microstructural Variations

Polyvinyl chloride (PVC) synthesized via free radical polymerization predominantly features an atactic microstructure, characterized by irregular stereochemical configurations along the polymer chain, with commercial grades typically exhibiting approximately 55% syndiotactic dyads and shorter syndiotactic sequences amid heterotactic and minor isotactic segments.[46] This atactic nature renders PVC largely amorphous, though rigid formulations can develop limited crystallinity—generally 5-10%—arising from local ordering of syndiotactic sequences under specific processing conditions like annealing, which enhances chain packing without achieving full isotactic or syndiotactic regularity.[47] Isotactic defects, being rarer due to the polymerization mechanism favoring syndiotactic addition, contribute minimally to overall structure but can influence local chain mobility when present.[48] Chain irregularities such as branching and head-to-head linkages arise primarily from chain transfer reactions during polymerization, including transfer to monomer or intramolecular backbiting, resulting in short branches (e.g., chloromethyl side groups) and occasional long branches, with high-quality resins maintaining fewer than 5 defects per 1,000 vinyl chloride units to ensure optimal processability.[48] [49] Head-to-head defects, formed via allylic chlorination or rearrangement, disrupt regular head-to-tail propagation and correlate with reduced thermal stability and increased melt viscosity, as these structural anomalies hinder uniform chain entanglement and promote uneven stress distribution.[50] Such defects elevate the glass transition temperature (Tg) slightly above the baseline of ~80°C for defect-free atactic chains, exacerbating inherent brittleness in unplasticized PVC by limiting segmental motion.[51] Nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectroscopy, particularly ¹H and ¹³C NMR, serves as the primary analytical tool for quantifying tacticity and defect concentrations, resolving methylene and methine resonances to distinguish syndiotactic (rr), heterotactic (mr), and isotactic (mm) triads, as well as defect-specific signals like those from branched carbons.[48] [52] In suspension-polymerized PVC, which dominates industrial production, particle microstructure features hierarchical porosity (0.3-0.6 mL/g) stemming from phase separation of monomer-polymer phases during polymerization, empirically correlating with enhanced absorption of additives like plasticizers due to increased internal surface area and diffusion pathways.[53] [54] This porosity, influenced by polymerization variables such as temperature and initiator type, directly affects resin swellability and fusion behavior without altering intrinsic chain tacticity.[55]Industrial Production

Manufacturing Processes

Suspension polymerization dominates industrial PVC production, accounting for approximately 80% of global output due to its scalability and efficiency in producing high-purity resin.[56] This batch process occurs in large reactors with volumes of 60 to 200 cubic meters, capable of handling charges equivalent to over 100 tons of vinyl chloride monomer (VCM) suspension, enabling annual productivities of 300 tons per cubic meter per year in optimized facilities.[57] Following polymerization, the resulting slurry is centrifuged or filtered to separate solids, with unreacted VCM recovered via steam stripping or distillation for recycling, after which the wet resin undergoes thermal drying in fluidized bed or rotary dryers and milling to achieve uniform particle size distribution typically below 150 micrometers.[58] Chlorine, a key precursor for VCM synthesis via oxychlorination of ethylene, is produced industrially through the chlor-alkali process, which electrolyzes aqueous sodium chloride brine in membrane or diaphragm cells to yield chlorine gas alongside caustic soda and hydrogen.[59] Approximately 40% of global chlorine output supports PVC-related VCM production.[60] Process energy intensity for suspension PVC stands at about 3.21 gigajoules per metric ton, encompassing heating, cooling, and separation steps, though total cradle-to-gate energy including feedstocks exceeds 60 gigajoules per ton.[61] [62] Quality control emphasizes standardization of the K-value, determined from dilute solution viscosity as a proxy for average degree of polymerization, with rigid pipe grades requiring K-values of 65 to 68 to balance processability and mechanical strength.[63] Variations are minimized through precise control of initiator dosage, temperature profiles (typically 50-60°C), and suspension agents during batches lasting 4-8 hours.[64] From 2023 onward, select producers have initiated trials incorporating bio-based ethylene derived from sugarcane ethanol into VCM production, enabling partially renewable PVC resins with up to 100% bio-attributed carbon in the ethylene dichloride step, though full commercialization remains limited by cost and scale.[65] These efforts align with market projections for bio-based PVC growth at over 19% CAGR through 2030, driven by regulatory pressures on fossil feedstocks.[65]Global Production Statistics and Major Producers

Global polyvinyl chloride (PVC) capacity reached approximately 60.9 million tonnes per annum (mtpa) in 2023, with projections for growth to around 70 mtpa by 2028 driven by expansions primarily in Asia.[66] Actual production volumes were near 57 million tonnes in 2024, reflecting operating rates below full capacity due to supply overhang and uneven demand recovery post-pandemic.[67] Asia dominates output, accounting for over 60% of global capacity, with China alone producing 23.44 million tonnes in 2024—roughly 41% of worldwide totals—bolstered by low-cost coal-based ethylene derivatives.[68] [69]| Region | Approximate 2024 Production Share |

|---|---|

| Asia (incl. China) | ~65% |

| Europe | ~15% |

| North America | ~10% |

| Others | ~10% |

Additives and Formulations

Essential Additives and Their Roles

Plasticizers are incorporated into flexible polyvinyl chloride (PVC) formulations at levels typically ranging from 30 to 50 parts per hundred resin (phr) to lower the glass transition temperature (Tg), thereby enhancing chain mobility and enabling pliability at ambient temperatures through increased intermolecular spacing and reduced intermolecular forces.[76][77] Lubricants, added at 0.5 to 3 phr, facilitate melt flow during extrusion and molding by reducing friction between polymer chains and processing equipment, preventing adhesion and ensuring uniform processing without altering the final bulk properties.[78] Heat stabilizers, essential at 1 to 5 phr, function by scavenging hydrochloric acid (HCl) released during thermal dehydrochlorination above 100°C, thereby interrupting the autocatalytic degradation chain reaction that leads to discoloration and loss of mechanical integrity.[79][80] Fillers such as calcium carbonate (CaCO3), often used up to 50 phr in rigid formulations, reduce material costs by partial substitution of resin while providing reinforcement through particle-polymer interactions that maintain rigidity and improve stiffness without significantly compromising processability.[81][82] Impact modifiers, typically at 5 to 20 phr, enhance toughness by forming dispersed rubbery domains within the PVC matrix that absorb energy during stress, mitigating brittle failure through crazing and shear yielding mechanisms.[78][83] Pigments, added at 0.1 to 5 phr depending on opacity needs, impart color via light absorption and scattering without influencing primary structural properties, selected empirically for dispersion stability.[77] Additive dosages are optimized through rheological testing, such as capillary rheometry or torque rheometer measurements, to balance flow behavior, dispersion, and phase compatibility during compounding.[84] Total additive content varies from 10 to 20% by weight in rigid PVC, where minimal plasticization preserves inherent stiffness, to up to 60% in flexible variants dominated by high plasticizer loads that dictate overall formulation economics and performance.[85][86]Specific Additives: Phthalates and Stabilizers

Di(2-ethylhexyl) phthalate (DEHP), a common ortho-phthalate plasticizer, is incorporated into flexible polyvinyl chloride (PVC) at levels up to 40% by weight, particularly in flooring and other vinyl products, to achieve the desired pliability.[87] This loading, often 20-50 parts per hundred resin (phr), lowers the glass transition temperature and enables flexibility at low temperatures, such as down to -40°C in plasticized formulations.[88] Regulatory actions in the 2010s, including restrictions on DEHP in certain regions, prompted a shift toward alternatives like dioctyl terephthalate (DOTP), which offers comparable performance without the ortho-phthalate structure and has seen increased adoption in flexible PVC applications.[89][90] Heat stabilizers mitigate PVC's susceptibility to dehydrochlorination during processing and use. Lead-based stabilizers were voluntarily phased out across the EU by the end of 2015 under REACH-related commitments, with organotin compounds restricted earlier due to toxicity concerns.[91] Calcium-zinc (Ca-Zn) stabilizers have since become prevalent, accounting for approximately 83% of heat stabilizers in the EU market and serving as the standard for food-contact PVC.[92] These stabilizers enhance thermal endurance, supporting a deflection temperature under load (DTUL) of around 60-80°C in stabilized rigid PVC, while plasticizers like phthalates maintain flexibility across a wide temperature range.[93] Global phthalate plasticizer consumption surpasses 3 million tons annually, with the majority directed toward PVC softening, though bio-based options—such as those derived from vegetable oils—have gained traction since 2023 as sustainable substitutes.[94][95]Material Properties

Physical and Mechanical Characteristics

Rigid polyvinyl chloride (PVC) has a density of 1.38 to 1.45 g/cm³, while flexible formulations incorporating plasticizers exhibit slightly lower values in the range of 1.2 to 1.4 g/cm³.[96] These densities contribute to PVC's favorable strength-to-weight ratio, enabling lightweight yet durable components in structural testing.[97] In mechanical testing per ASTM D638 standards, rigid unplasticized PVC demonstrates a tensile strength of 45 to 55 MPa at 23°C, with elongation at break typically under 50% indicating limited ductility.[97] [98] Flexible PVC, modified with plasticizers, shows reduced tensile strength of 10 to 25 MPa but significantly higher elongation of 200 to 450%, enhancing its suitability for deformation under load.[99] Young's modulus for rigid PVC falls between 2.5 and 4 GPa, reflecting its stiffness in uniaxial tension tests.[100]| Property | Rigid PVC | Flexible PVC | Test Standard |

|---|---|---|---|

| Tensile Strength (MPa) | 45-55 | 10-25 | ASTM D638[97] |

| Elongation at Break (%) | <50 | 200-450 | ASTM D638[101] |

| Young's Modulus (GPa) | 2.5-4 | 0.01-0.1 | ASTM D638[100] |

Thermal, Chemical, and Fire Behavior

Rigid polyvinyl chloride (PVC) has a glass transition temperature of 80–85 °C, marking the transition from a rigid, glassy state to a more compliant, rubbery phase, which influences its dimensional stability and processability limits; consequently, exposure to boiling water at 100 °C can cause immediate deformation in PVC sewage pipes, exceeding this softening threshold.[104][105][106] Thermal degradation commences via dehydrochlorination, evolving hydrogen chloride (HCl) gas, with onset typically above 200 °C in formulations containing heat stabilizers that delay autocatalytic zipper-like unzipping of the polymer chain.[107] This process yields conjugated polyene sequences, promoting discoloration and reduced mechanical integrity without intervention.[108] PVC exhibits strong chemical inertness to most mineral acids, alkalis, and salts at ambient conditions, resisting corrosion from environments like dilute sulfuric acid or sodium hydroxide solutions due to the stability of its C-Cl bonds.[109] However, it dissolves or swells in polar organic solvents such as ketones (e.g., acetone) and tetrahydrofuran, where solvating interactions disrupt intermolecular forces.[110] Ultraviolet exposure induces photodegradation primarily through chain scission and secondary crosslinking, generating radicals that propagate embrittlement and surface cracking via Norrish-type mechanisms.[111] This degradation accelerates in transparent or light-colored PVC lacking inherent UV blockers, leading to cracking and clouding within 1-2 years in exposed applications such as cable sheaths, whereas black PVC with carbon black pigments absorbs and dissipates UV rays, conferring superior long-term protection.[112][113] In fire scenarios, rigid PVC displays self-extinguishing behavior with a limiting oxygen index (LOI) of 45–50 vol%, exceeding that of wood (21–22 vol%) or many thermoplastics (17–18 vol%), as chlorine content promotes char formation and dilution of flammable volatiles.[114] Cone calorimeter tests under standard irradiances (e.g., 50 kW/m²) yield peak heat release rates (pHRR) typically ranging 50–200 kW/m² for rigid variants, lower than polystyrene's ~1,500 kW/m², though dense smoke evolves from incomplete combustion of aromatic residues.[115] Plasticized forms increase smoke production via enhanced volatility, but inherent charring limits sustained flaming.[116]Applications

Construction and Infrastructure

Rigid polyvinyl chloride (PVC) constitutes the predominant form utilized in construction and infrastructure applications, prized for its durability, corrosion resistance, and cost-effectiveness compared to metal alternatives. In piping systems for water distribution, sewerage, and drainage, rigid PVC pipes exhibit exceptional longevity, often exceeding 100 years under normal conditions with minimal degradation or maintenance needs.[117][118] These pipes demonstrate lower main break rates than cast iron or ductile iron equivalents, attributed to their inherent resistance to corrosion from soil, water, and chemicals, thereby reducing leakage risks and extending service life beyond 50 years even in aggressive environments.[117][119] Globally, PVC pipe production reached approximately 25.9 to 30.2 million metric tons in 2024, with construction and infrastructure sectors driving demand through applications in municipal water supply and underground utilities.[120][121] Rigid PVC fittings in these systems offer seismic resilience, accommodating ground movements via flexibility that absorbs shockwaves and prevents brittle failure, as evidenced in post-earthquake assessments where PVC networks sustained integrity better than rigid metals in moderate seismic zones.[122][123] This performance stems from the material's ability to flex without cracking, with joint designs engineered to handle axial and shear forces during dynamic events.[124] In building envelopes, rigid PVC profiles for windows and exterior siding enhance thermal insulation, minimizing heat loss and potentially reducing residential heating costs by 7-15% when replacing older single-pane or uninsulated systems.[125] Vinyl siding formulations further contribute by sealing air gaps and providing reflective surfaces that limit solar heat gain, supporting overall energy efficiency without the rust or weight issues of metal cladding.[126][127]Electrical, Packaging, and Consumer Products

PVC serves as a primary material for electrical wire and cable insulation owing to its flexibility, cost-effectiveness, and dielectric strength, which typically ranges from 14 to 30 kV/mm depending on formulation and processing.[128][129] This property enables PVC to prevent electrical breakdown under high voltages while maintaining pliability for installation in conduits and buildings. Additionally, PVC coatings provide mechanical protection against abrasion, moisture ingress, and chemical exposure, contributing to cable reliability in diverse environments.[130] The adoption of PVC over traditional lead sheathing in cables has achieved weight reductions of up to 50%, facilitating easier handling, reduced transportation costs, and elimination of lead's environmental hazards without compromising protective functions.[131] Flexible PVC compounds, often plasticized, dominate low- and medium-voltage applications, with global demand reflecting its role in infrastructure wiring and automotive harnesses. In packaging, PVC is utilized for blister packs, thermoformed trays, and stretch films, leveraging its optical clarity, impact resistance, and ability to form tight barriers when laminated or coated.[132] These attributes ensure product visibility and protection from physical damage during handling and display. Food-contact PVC variants, formulated without prohibited additives, comply with U.S. FDA regulations under 21 CFR for indirect food additives, permitting short-term exposure in applications like cling wraps.[133] Consumer products incorporate PVC in items such as vinyl flooring, garden hoses, and phonograph records, where its water resistance, ease of processing, and durability support everyday utility. Stabilized PVC formulations exhibit enhanced UV and ozone resistance compared to unstabilized natural rubber, extending outdoor lifespan in hoses to 2-3 years under typical exposure versus rapid degradation in untreated rubber.[134] In flooring, PVC's low maintenance and resilience to foot traffic provide longevity exceeding that of some organic alternatives, with production emphasizing rigid or semi-rigid grades for stability.[135]Healthcare and Specialized Uses

Polyvinyl chloride (PVC) has been employed in medical applications since the mid-20th century, particularly for disposable items that require flexibility, clarity, and compatibility with sterilization processes. The first PVC blood bag was developed in 1947, replacing fragile glass containers and enabling safer blood storage and transfusion.[136] This adoption expanded in subsequent decades, with flexible PVC becoming standard for intravenous (IV) bags and tubing due to its durability and low cost, facilitating the shift toward single-use devices that reduced infection transmission risks in healthcare settings.[137] Flexible PVC formulations for IV bags and tubing often incorporate plasticizers like di(2-ethylhexyl) phthalate (DEHP) to achieve necessary pliability, though non-phthalate alternatives are available to minimize potential extractables. Studies indicate DEHP leaching from PVC IV bags into solutions can reach concentrations up to 148 µg/L under specific conditions, such as agitation or transport, but routine clinical use typically results in lower exposure levels.[138][139] Non-DEHP PVC tubing maintains biocompatibility, passing USP Class VI tests and supporting gamma or ethylene oxide sterilization without significant degradation. Powder-free vinyl (PVC) gloves serve as a hypoallergenic alternative to natural rubber latex, avoiding type I allergic reactions that historically affected 10-17% of healthcare workers exposed to latex proteins. Vinyl gloves exhibit minimal sensitization potential, with allergy rates approaching negligible levels compared to latex, making them suitable for examination and low-risk procedures.[140][141] In blood-contacting devices, PVC demonstrates favorable hemocompatibility, with hemolysis rates in standardized tests typically below 5% and often under 1%, indicating low erythrocyte damage.[142] Chlorinated PVC (CPVC), a modified variant, finds specialized use in healthcare infrastructure for hot water piping systems, enduring temperatures up to 93°C while meeting potable water standards for hospital distribution networks.[143][144]