Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Litter (vehicle)

View on Wikipedia

The litter is a class of wheelless vehicles, a type of human-powered transport, for the transport of people. Smaller litters may take the form of open chairs or beds carried by two or more carriers, some being enclosed for protection from the elements. Larger litters, for example those of the Chinese emperors, may resemble small rooms upon a platform borne upon the shoulders of a dozen or more people. To most efficiently carry a litter, porters either place the carrying poles directly upon their shoulders or use a yoke to transfer the load from the carrying poles to the shoulders.

Definitions

[edit]

A simple litter consists of a sling attached along its length to poles or stretched inside a frame. The poles or frame are carried by porters in front and behind. Such simple litters are common on battlefields and emergency situations, where terrain prohibits wheeled vehicles from carrying away the dead and wounded.

Litters can also be created quickly by the lashing of poles to a chair. Such litters, consisting of a simple cane chair, sometimes an umbrella to ward off the elements, and two stout bamboo poles, may still be found in Chinese mountain resorts such as the Huangshan Mountains to carry tourists along scenic paths and to viewing positions inaccessible by other means of transport.

A more luxurious version consists of a bed or couch, sometimes enclosed by curtains, for the passenger or passengers to lie on. These are carried by at least two porters in equal numbers in front and behind, using wooden rails that pass through brackets on the sides of the couch. The largest and heaviest types would be carried by draught animals.

Another form, commonly called a sedan chair, consists of a chair or windowed cabin suitable for a single occupant, also carried by at least two porters, one in front and one behind, using wooden rails that pass through brackets on the sides of the chair. These porters were known in London as "chairmen". These have been very rare since the 19th century, but such enclosed portable litters have been used as an elite form of transport for centuries, especially in cultures where women are kept secluded.

Sedan chairs, in use until the 19th century, were accompanied at night by link-boys who carried torches.[1] Where possible, the link boys escorted the fares to the chairmen, the passengers then being delivered to the door of their lodgings.[1] Several houses in Bath, Somerset, England still have the link extinguishers on the exteriors, shaped like outsized candle snuffers.[1] In the 1970s, entrepreneur and Bathwick resident, John Cuningham, revived the sedan chair service business for a brief amount of time.[1]

In traditional Catholic processions, holy statues and relics are still carried through the streets using litters.

-

Catholic procession with a statue of the Virgin Mary being carried on a litter, London, 2010

Antiquity

[edit]

In pharaonic Egypt and many other places such as India, Rome, and China, the ruler and divinities (in the form of an idol like lord Krishna) were often transported in a litter in public, frequently in procession, as during state ceremonial or religious festivals.

The Ark of the Covenant in the Book of Exodus resembles a litter.

In Ancient Rome, a litter called lectica or sella often carried members of the imperial family, as well as other dignitaries and other members of the rich elite, when not mounted on horseback.

The Third Council of Braga in 675 AD ordered that bishops, when carrying the relics of martyrs in procession, must walk to the church, and not be carried in a chair, or litter, by deacons clothed in white.

In the Catholic Church, popes were carried the same way in sedia gestatoria, which was replaced later by the popemobile.

-

Simple wooden litter of the Nineteenth – Twentieth Dynasty of Egypt (Egyptian New Kingdom), 1292–1077 BCE. Museo Egizio, Turin, Italy

In Asia

[edit]Indian subcontinent

[edit]

A palanquin is a covered litter, usually for one passenger. It is carried by an even number of bearers (between two and eight, but most commonly four) on their shoulders, by means of a pole projecting fore and aft.[2][3][4]

The word is derived from the Sanskrit palyanka, meaning bed or couch. The Malay and Javanese form is palangki, in Bengali and Hindi, palki, in Telugu pallaki. The Portuguese apparently added a nasal termination to these to make palanquim. English adopted it from Portuguese as "palanquin".[2][3]

Palanquins vary in size and grandeur. The smallest and simplest, a cot or frame suspended by the four corners from a bamboo pole and borne by two bearers, is called a doli.[3][5] Larger palanquins are rectangular wooden boxes eight feet long, four feet wide, and four feet high, with openings on either side screened by curtains or shutters.[2] Interiors are furnished with bedding and pillows. Ornamentation reflects the social status of the traveller. The most ornate palanquins have lacquer paintwork and cast bronze finials at the ends of the poles. Designs include foliage, animals, and geometric patterns.[4]

Ibn Batutta describes them as being "carried by eight men in two lots of four, who rest and carry in turn. In the town there are always a number of these men standing in the bazaars and at the sultan's gate and at the gates of other persons for hire." Those for "women are covered with silk curtains."[6]

Palanquins are mentioned in literature as early as the Ramayana (c. 250 BC).[3] Indian women of rank always travelled by palanquin.[2] The conveyance proved popular with European residents in India, and was used extensively by them. Pietro Della Valle, a 17th-century Italian traveller, wrote:

Going in Palanchino in the Territories of the Portugals in India is prohibited to men, because indeed 'tis a thing too effeminate, nevertheless, as the Portugals are very little observers of their own Laws, they began at first to be tolerated upon occasion of the Rain, and for favours, or presents, and afterwards became so common that they are us'd almost by everybody throughout the whole year.[7]

Being transported by palanquin was pleasant.[4] Owning one and keeping the staff to power it was a luxury affordable even to low-paid clerks of the East India Company. Concerned that this indulgence led to neglect of business in favor of "rambling", in 1758 the Court of Directors of the company prohibited its junior clerks from purchasing and maintaining palanquins.[3][8] Also in the time of the British in India, dolis served as military ambulances, used to carry the wounded from the battlefield.[5]

In the early 19th century, the most prevalent mode of long-distance transport for the affluent was by palanquin.[8][9] The post office could arrange, with a few days notice, relays of bearers to convey a traveller's palanquin between stages or stations.[3][9] The distance between these in the government's dak (Hindi: "mail")[10] system averaged about 10 miles (16 km), and could be covered in three hours. A relay's usual complement consisted of two torch-bearers, two luggage-porters, and eight palanquin-bearers who worked in gangs of four, although all eight might pitch in at steep sections. A passenger could travel straight through or break their journey at dak bungalows located at certain stations.[9]

Until the mid-19th century, palanquins remained popular for those who could afford them,[8] but they fell out of favor for long journeys as steamers, railways, and roads suitable for wheeled transport were developed.[3] By the beginning of the 20th century they were nearly "obsolete among the better class of Europeans".[8] Rickshaws, introduced in the 1930s, supplanted them for trips around town.[3]

Modern use of the palanquin is limited to ceremonial occasions. A doli carries the bride in a traditional wedding,[11] and they may be used to carry religious images in Hindu processions.[12] Many parts in Uttar Pradesh, India like Gorakhpur and around places Vishwakarma communities has been involved in making the dolis for wedding processions. The last known doli making dates back around 2000 by Sharmas(Vishwakarmas) in Gorakhpur, Uttar Pradesh.

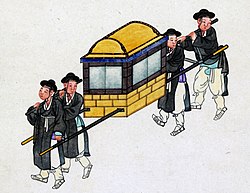

China

[edit]

In Han China the elite travelled in light bamboo seats supported on a carrier's back like a backpack. In the Northern Wei dynasty and the Northern and Southern Song dynasty, wooden carriages on poles appear in painted landscape scrolls.

A commoner used a wooden or bamboo civil litter (Chinese: 民轎; pinyin: min2 jiao4), while the mandarin class used an official litter (Chinese: 官轎; pinyin: guan1 jiao4) enclosed in silk curtains.

The chair with perhaps the greatest importance was the bridal chair (Chinese: 喜轎; pinyin: xi3 jiao4). A traditional bride is carried to her wedding ceremony by a "shoulder carriage" (Chinese: 肩輿; pinyin: jiān yú), usually hired. These were lacquered in an auspicious shade of red, richly ornamented and gilded, and were equipped with red silk curtains to screen the bride from onlookers.[13]

Sedan chairs were once the only public conveyance in Hong Kong, filling the role of cabs. Chair stands were found at all hotels, wharves, and major crossroads. Public chairs were licensed, and charged according to tariffs which would be displayed inside.[13] Private chairs were an important marker of a person's status. Civil officers' status was denoted by the number of bearers attached to his chair.[13] Before Hong Kong's Peak Tram went into service in 1888, wealthy residents of The Peak were carried on sedan chairs by porters up the steep paths to their residence including Sir Richard MacDonnell's (former Governor of Hong Kong) summer home, where they could take advantage of the cooler climate. Since 1975 an annual sedan chair race has been held to benefit the Matilda International Hospital and commemorate the practice of earlier days.

Korea

[edit]

In Korea, royalty and aristocrats were carried in wooden litters called gama (Korean: 가마). Gamas were primarily used by royalty and government officials. There were six types of gama, each assigned to different government official rankings.[14] Because of the difficulties posed by the mountainous terrain of the Korean peninsula and the lack of paved roads, gamas were preferred over wheeled vehicles.[14] In traditional weddings, the bride and groom are carried to the ceremony in separate gamas,[15] this custom goes back to the times of Joseon Dynasty, when the gamas were also used for celebrations of passing government exams and funerals.

Japan

[edit]

As the population of Japan increased and less and less land remained available for the grazing of animals, restrictions were placed upon the use of horses for non-military purposes, with the result that human-powered transport grew increasingly important and eventually came to prevail.[citation needed]

Kago (Kanji: 駕籠, Hiragana: かご) were often used in Japan to transport the non-samurai citizen. Norimono were used by the warrior class and nobility, most famously during the Tokugawa period when regional samurai were required to spend a part of the year in Edo (Tokyo) with their families, resulting in yearly migrations of the rich and powerful (Sankin-kōtai) to and from the capital along the central backbone road of Japan.

Somewhat similar in appearance to kago are the portable shrines that are used to carry the "god-body" (goshintai), the central totemic core normally found in the most sacred area of Shinto Shrines, on a tour to and from a shrine during some religious festivals.

Vietnam

[edit]

Traditional Vietnam employed two distinct types of litters, the cáng and the kiệu. The cáng is a basic bamboo pole with the rider reclining in a hammock. More elaborate cáng had an adjustable woven bamboo shade to shelter the occupant. Dignitaries would have an entourage to carry parasols.

The kiệu resemble more of the sedan chair, enclosed with a fixed elaborately carved roof and doors. While the cáng has become obsolete, the kiệu is retained in certain traditional rituals a part of a temple devotional procession.

Thailand

[edit]

In Thailand, the royalty were also carried in wooden litters called wo ("พระวอ" Phra Wo, literally, "Royal Sedan") for large ceremonies. Wos were elaborately decorated litters that were delicately carved and colored by gold leaf. Stained glass is also used to decorate the litters. Presently, Royal Wos and carriages are only used for royal ceremonies in Thailand. They are exhibited in the Bangkok National Museum.

Indonesia

[edit]

In traditional Javanese society, the generic palanquin or joli was a wicker chair with a canopy, attached to two poles, and borne on men's shoulders, and was available for hire to any paying customer.[16] As a status marker, gilded throne-like palanquins, or jempana, were originally reserved solely for royalty, and later co-opted by the Dutch, as a status marker: the more elaborate the palanquin, the higher the status of the owner. The joli was transported either by hired help, by nobles' peasants, or by slaves.

Historically, the palanquin of a Javanese king (raja), prince (pangeran), lord (raden mas) or other noble (bangsawan) was known as a jempana; a more throne-like version was called a pangkem. It was always part of a large military procession, with a yellow (the Javanese colour for royalty) square canopy. The ceremonial parasol (payung) was held above the palanquin, which was carried by a bearer behind and flanked by the most loyal bodyguards, usually about 12 men, with pikes, sabres, lances, muskets, keris and a variety of disguised blades. In contrast, the canopy of the Sumatran palanquin was oval-shaped and draped in white cloth; this was reflective of greater cultural permeation by Islam.[17][original research?] Occasionally, a weapon or heirloom, such as an important keris or tombak, was given its own palanquin. In Hindu culture in Bali today, the tradition of using palanquins for auspicious statues, weapons or heirlooms continues, for funerals especially; in more elaborate rituals, a palanquin is used to bear the body, and is subsequently cremated along with the departed.

Philippines

[edit]In pre-colonial Philippines, litters were a way of transportation for the elite (maginoo, ginu, tumao); Rajahs, Lakans, Datus, sovereign princes (Rajamuda) and their wives use a Sankayan or Sakayan, a wooden or bamboo throne with elaborate and intricate carvings carried by their servants. Also among their retinue were payong (umbrella)-bearers, to shade the royalty and nobility from the intense heat.

Princesses (binibini, dayang dayang) who were sequestered from the world were called Binukot or Binocot (“set apart”). A special type of royal, these individuals were forbidden to walk on the ground or be exposed to the general populace. When they needed to go anywhere, they were veiled and carried in a hammock or a basket-like litter similar to bird's nests carried by their slaves. Longer journeys required that they be borne inside larger, covered palanquins with silk covers, with some taking the form of a miniature hut.

In Spanish-colonial Philippines, litters remained one of the options of transportation for the Spanish inhabitants and members of the native principalia class.

In Africa

[edit]

In Southern Ghana the Akan and the Ga-Dangme carry their chiefs and kings in palanquins when they appear in their state durbars. When used in such occasions these palanquins may be seen as a substitutes of a state coach in Europe or a horse used in Northern Ghana. The chiefs of the Ga (mantsemei) in the Greater Accra Region (Ghana) use also figurative palanquins which are built after a chief's family symbol or totem. But these day the figurative palanquins are very seldom used. They are related with the figurative coffins which have become very popular among the Ga in the last 50 years. Since these figurative coffins were shown 1989 in the exhibition "Les magicians de la terre" in the Centre Pompidou in Paris they were shown in many art museums around the world.[18]

From at least the 15th century until the 19th century, litters of varying types known as tipoye were used in the Kingdom of Kongo as a mode of transportation for the elites. Seat-style litters with a single pole along the back of the chair carried by two men (usually slaves) were topped with an umbrella. Lounge-style litters in the shape of a bed were used to move one to two people with a porter at each corner. Due to the tropical climate, horses were not native to the area nor could they survive very long once introduced by the Portuguese. Human portage was the only mode of transportation in the region and became highly adept with missionary accounts claiming the litter transporters could move at speeds 'as fast as post horses at the gallop'.[19]

In the West

[edit]In Europe

[edit]

Portuguese and Spanish navigators and colonisers encountered litters of various sorts in India, Mexico, and Peru. Such novelties, imported into Spain, spread into France and then to Britain. Most of the European names for these devices ultimately derive from the root sed-, as in Latin sedere, "to sit", which gave rise to seda ("seat") and its diminutive sedula ("little seat"), the latter of which was contracted to sella, the traditional Classical Latin name for a chair, including a carried chair.[20] The German term Sänfte ("smoothness"), however, refers to the comfort of the ride.[21]

In Europe this mode of transportation met with instant success. Henry VIII of England (reigned 1509–1547) was carried around in a sedan chair—it took four strong chairmen to carry him towards the end of his life—but the expression "sedan chair" did not appear in print until 1615. Trevor Fawcett notes (see link) that British travellers Fynes Moryson (in 1594) and John Evelyn (in 1644–45) remarked on the seggioli of Naples and Genoa, which were chairs for public hire slung from poles and carried on the shoulders of two porters.

From the mid-17th century, visitors taking the waters at Bath would be conveyed in a chair enclosed in baize curtains, especially if they had taken a heated bath and were going straight to bed to sweat. The curtains kept off a possibly fatal draught. These were not the proper sedan chairs "to carry the better sort of people in visits, or if sick or infirmed" (Celia Fiennes).[citation needed] In the 17th and 18th centuries, the chairs stood in the main hall of a well-appointed city residence, where a lady could enter and be carried to her destination without setting foot in a filthy street. The neoclassical sedan chair made for Queen Charlotte (Queen Consort from 1761 to 1818) remains at Buckingham Palace.

By the mid-17th century, sedans for hire had become a common mode of transportation. London had "chairs" available for hire in 1634, each assigned a number and the chairmen licensed because the operation was a monopoly of a courtier of King Charles I. Sedan chairs could pass in streets too narrow for a carriage, helping to alleviate the crush of coaches in London streets, an early instance of traffic congestion. A similar system later operated in Scotland. In 1738 a fare system was established for Scottish sedans, and the regulations covering chairmen in Bath are reminiscent of the modern Taxi Commission's rules. A trip within a city cost six pence and a day's rental was four shillings. A sedan was even used as an ambulance in Scotland's Royal Infirmary.[citation needed]

Chairmen moved at a good clip. In Bath they had the right-of-way: pedestrians hearing "By your leave" behind them knew to flatten themselves against walls or railings as the chairmen hustled through. There were often[quantify] disastrous accidents, upset chairs, and broken glass-paned windows.

In Great Britain, in the early 19th century, the public sedan chair began to fall out of use, perhaps because streets were better paved or perhaps because of the rise of the more comfortable, companionable and affordable hackney carriage. In Glasgow, the decline of the sedan chair is illustrated by licensing records which show twenty-seven sedan chairs in 1800, eighteen in 1817, and ten in 1828. During that same period the number of registered hackney carriages in Glasgow rose to one hundred and fifty.

In the Americas

[edit]The wealthy are recorded to have used sedan chairs in the cities of colonial America and the early period of the United States. In 1787, Benjamin Franklin, at the time 81 years old, gouty, and in generally declining health, is noted to have travelled to meetings of the United States Constitutional Convention in a sedan chair carried by four prisoners.[22]

Colonial practice

[edit]In various colonies, litters of various types were maintained under native traditions, but often adopted by the colonials as a new ruling and/or socio-economic elite, either for practical reasons (often comfortable modern transport was unavailable, e.g. for lack of decent roads) and/or as a status symbol. During the 17–18th centuries, palanquins (see above) were very popular among European traders in Bengal, so much so that in 1758 an order was issued prohibiting their purchase by certain lower-ranking employees.[23][better source needed]

"Silla" of Latin America

[edit]

A similar but simpler palanquin was used by the elite in parts of 18th- and 19th-century Latin America. Often simply called a silla (Spanish for seat or chair), it consisted of a simple wooden chair with an attached tumpline. The occupant sat in the chair, which was then affixed to the back of a single porter, with the tumpline supported by his head. The occupant thus faced backwards during travel. This style of palanquin was probably due to the steep terrain and rough or narrow roads unsuitable to European-style sedan chairs. Travellers by silla usually employed a number of porters, who would alternate carrying the occupant.[citation needed] The porters were known as silleros, cargueros or silleteros (sometimes translated as "saddle-men").

A chair borne on the back of a porter, almost identical to the silla, is used in the mountains of China for ferrying older tourists and visitors up and down the mountain paths. One of these mountains where the silla is still used is the Huangshan Mountains of Anhui province in Eastern China.[citation needed]

See also

[edit]- Bath chair

- Litter (rescue basket)

- Sling (furniture)

- Mikoshi

- Sedia gestatoria, the portable throne of the popes

- Ark of the Covenant, described in the Hebrew Bible as a portable sacred container and throne of God, sharing similarities with portable shrines and covered sedan chairs

- Howdah (carriage positioned on the back of an elephant or camel)

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d Bath Chronicle (December 2, 2002) Sedan Chairs Ride Again. Page 21.

- ^ a b c d Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Islam, Sirajul (2012). "Palanquin". In Islam, Sirajul; Jamal, Ahmed A. (eds.). Banglapedia: National Encyclopedia of Bangladesh (Second ed.). Asiatic Society of Bangladesh.

- ^ a b c "1850s Palki (Palanquin)". Heritage Transport Museum.

- ^ a b Yule, Henry; Burnell, Arthur Coke (1903). Crooke, William (ed.). Hobson-Jobson: A Glossary of Colloquial Anglo-Indian Words and Phrases, and of Kindred Terms, Etymological, Historical, Geographical and Discursive. London: John Murray. p. 313.

- ^ Battutah, Ibn (2002). The Travels of Ibn Battutah. London: Picador. pp. 186, 318. ISBN 9780330418799.

- ^ Della Valle, Pietro (1892) [First translated 1664]. Grey, Edward (ed.). The Travels of Pietro Della Valle in India from the old English translation of 1664 by G. Havers. Vol. I. Translated by Havers, George. London: Hakluyt Society. p. 185.

- ^ a b c d Yule, Henry; Burnell, Arthur Coke (1903). Crooke, William (ed.). Hobson-Jobson: A Glossary of Colloquial Anglo-Indian Words and Phrases, and of Kindred Terms, Etymological, Historical, Geographical and Discursive. London: John Murray. pp. 659–661.

- ^ a b c Dodd, George (1859). The History of the Indian Revolt, and of the Expeditions to Persia, China, and Japan, 1856-7-8. pp. 20–22.

- ^ Yule, Henry; Burnell, Arthur Coke (1903). Crooke, William (ed.). Hobson-Jobson: A Glossary of Colloquial Anglo-Indian Words and Phrases, and of Kindred Terms, Etymological, Historical, Geographical and Discursive. London: John Murray. p. 299.

- ^ Anand, Jatin (21 November 2016). "Big, fat weddings getting trim". The Hindu. Retrieved 2017-01-08.

- ^ Pattanaik, Devdutt (27 November 2016). "Pilgrim nation: The Goddess Meenakshi of Madurai". Mumbai Mirror. Retrieved 2017-01-08.

- ^ a b c A Hong Kong Sedan Chair, Illustrations of China and Its People, John Thomson 1837–1921, (London, 1873–1874)

- ^ a b "'Gama': a comprehensive art". The Korea Times. November 24, 2015.

- ^ "Riding sedan chair to wedding". The Korea Times. April 21, 2014.

- ^ Tomlin, Jacob Missionary Journals and Letters: Written During Eleven Years' Residence and Travels Amongst the Chinese, Siamese, Javanese, Khassias, and Other Eastern Nations Nisbet: 1844: 384 pages, pp 251:

- ^ Locher-Scholten, Elsbeth; Jackson, Beverley (2004). Sumatran sultanate and colonial state: Jambi and the rise of Dutch imperialism, 1830–1907. SEAP Publications. ISBN 0-87727-736-2.

- ^ Regula Tschumi: The Figurative Palanquins of the Ga. History and Significance. In: African Arts, 46 (4), 2013, S. 60–73.

- ^ George Balandier "Daily Life in the Kingdom of the Kongo" (1968), p. 117

- ^ T. Atkinson Jenkins. "Origin of the Word Sedan", Hispanic Review, Vol. 1, No. 3 (July 1933), pp. 240–242.

- ^ "Sänfte – Schreibung, Definition, Bedeutung, Etymologie, Synonyme, Beispiele". January 2025.

- ^

Colbert, David (2 June 2009). "A Rising Sun". Benjamin Franklin. New York: Simon and Schuster (published 2009). ISBN 9781416998891. Retrieved 2 December 2018.

Of the fifty-five delegates, Franklin is by far the oldest at eighty-one. His health is not good. On the day the convention opened he was too sick to come. Later he was carried from his home to the meetings in a sedan chair – like a carriage without wheels, held aloft by four men. The bumpy ride of a carriage would have been too uncomfortable.

- ^ koron

- Tirso López Bardón (1913). . In Herbermann, Charles (ed.). Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

Further reading

[edit]- Regula Tschumi: Concealed Art. The Figurative Palanquins and Coffins in Ghana. Berne, Edition Till Schaap 2014.

- Regula Tschumi: The Figurative Palanquins of the Ga. History and Significance. In: African Arts, Vol. 46, Nr. 4, 2013, S. 60–73.

- Trevor Fawcett, "Chair transport in Bath": from Bath History, II (1988): richly detailed social history

- Luxury Transport of Palanquins: Historical exhibit at Kamat.com