Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Physis

View on Wikipedia| Part of a series on |

| Philosophy |

|---|

Physis (/ˈfaɪˈsɪs/; Ancient Greek: φύσις [pʰýsis]; pl. physeis, φύσεις) is a Greek philosophical, theological, and scientific term, usually translated into English—according to its Latin translation "natura"—as "nature". The term originated in ancient Greek philosophy, and was later used in Christian theology and Western philosophy. In pre-Socratic usage, physis was contrasted with νόμος, nomos, "law, human convention".[1] Another opposition, particularly well-known from the works of Aristotle, is that of physis and techne – in this case, what is produced and what is artificial are distinguished from beings that arise spontaneously from their own essence, as do agents such as humans.[2] Further, since Aristotle the physical (the subject matter of physics, properly τὰ φυσικά "natural things") has been juxtaposed to the metaphysical.[3]

Linguistics

[edit]The Greek word physis can be considered the equivalent of the Latin natura. The abstract term physis is derived from the verb phyesthai/phynai, which means “to grow”, “to develop”, “to become” (Frisk 2006: 1052; Caspers 2010b: 1068). In ancient philosophy one also finds the noun "physis" referring to the growth expressed in the verb phyesthai/phynai and to the origin of development (Plato, Menexenos 237a; Aristotle, Metaphysics 1014b16–17). In terms of linguistic history, this verb is related to forms such as the English “be”, German sein or Latin esse (Lohmann 1960: 174; Pfeifer 1993: 1273; Beekes 2010: 1598). In Greek itself, the aorist (a verbal aspect) of “to be” can be expressed with forms of phynai. With regard to its kinship with “being” and the basic meaning of the verb stem phy- or bhu- (“growing”), there has long been criticism of the conventional translation of the word "physis" with “nature”. With the Latin natura, which for its part goes back to the verb nasci (“to be born”), one transfers the basic word "physis" into a different sphere of association. In this way, the emerging growth (of plants, for instance) is transferred into the realm of being born.[4]

Greek philosophy

[edit]Pre-Socratic usage

[edit]The word φύσις is a verbal noun based on φύειν "to grow, to appear" (cognate with English "to be").[5] In Homeric Greek it is used quite literally, of the manner of growth of a particular species of plant.[6]

In pre-Socratic philosophy, beginning with Heraclitus, physis in keeping with its etymology of "growing, becoming" is always used in the sense of the "natural" development, although the focus might lie either with the origin, or the process, or the end result of the process. There is some evidence that by the 6th century BC, beginning with the Ionian School, the word could also be used in the comprehensive sense, as referring to "all things", as it were "Nature" in the sense of "Universe".[7]

In the Sophist tradition, the term stood in opposition to nomos (νόμος), "law" or "custom", in the debate on which parts of human existence are natural, and which are due to convention.[1][8] The contrast of physis vs. nomos could be applied to any subject, much like the modern contrast of "nature vs. nurture".

In Plato's Laws

[edit]In book 10 of Laws, Plato criticizes those who write works peri physeōs. The criticism is that such authors tend to focus on a purely "naturalistic" explanation of the world, ignoring the role of "intention" or technē, and thus becoming prone to the error of naive atheism. Plato accuses even Hesiod of this, for the reason that the gods in Hesiod "grow" out of primordial entities after the physical universe had been established.[9]

Because those who use the term mean to say that nature is the first creative power; but if the soul turns out to be the primeval element, and not fire or air, then in the truest sense and beyond other things the soul may be said to exist by nature; and this would be true if you proved that the soul is older than the body, but not otherwise.

- — Plato's Laws, Book 10(892c) – translation by Benjamin Jowett

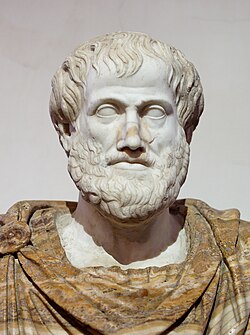

Aristotle

[edit]

Aristotle sought out the definition of "physis" to prove that there was more than one definition of "physis", and more than one way to interpret nature. "Though Aristotle retains the ancient sense of "physis" as growth, he insists that an adequate definition of "physis" requires the different perspectives of the four causes (aitia): material, efficient, formal, and final."[10] Aristotle believed that nature itself contained its own source of matter (material), power/motion (efficiency), form, and end (final). A unique feature about Aristotle's definition of "physis" was his relationship between art and nature. Aristotle said that "physis" (nature) is dependent on techne (art). "The critical distinction between art and nature concerns their different efficient causes: nature is its own source of motion, whereas techne always requires a source of motion outside itself."[10] What Aristotle was trying to bring to light, was that art does not contain within itself its form or source of motion. Consider the process of an acorn becoming an oak tree. This is a natural process that has its own driving force behind it. There is no external force pushing this acorn to its final state, rather it is progressively developing towards one specific end (telos).

Atomists

[edit]Quite different conceptions of "physis" are to be found in other Greek traditions of thought, e.g. the so-called Atomists, whose thinking found a continuation in the writings of Epicurus. For them, the world that appears is the result of an interplay between the void and the eternal movement of the “indivisible”, the atoms. This doctrine, most often associated with the names Democritus and Leucippus, is known mainly from the critical reactions to it in Aristotelian writings. It was supplemented by Epicurus in the light of developments in philosophy, in order to explain phenomena such as freedom of will. This was done by means of the theory of atoms’ “ability to deviate”, the parenklisis.[11]

Christian theology

[edit]Though φύσις was often used in Hellenistic philosophy, it is used only 14 times in the New Testament (10 of those in the writings of Paul).[12] Its meaning varies throughout Paul's writings.[13] One usage refers to the established or natural order of things, as in Romans 2:14 where Paul writes "For when Gentiles, who do not have the law, by nature do what the law requires, they are a law to themselves, even though they do not have the law."[14][15] Another use of φύσις in the sense of "natural order" is Romans 1:26 where he writes "the men likewise gave up natural relations with women and were consumed with passion for one another".[16][17] In 1 Corinthians 11:14, Paul asks "Does not nature itself teach you that if a man wears long hair it is a disgrace for him?"[18][19]

This use of φύσις as referring to a "natural order" in Romans 1:26 and 1 Corinthians 11:14 may have been influenced by Stoicism.[19] The Greek philosophers, including Aristotle and the Stoics are credited with distinguishing between man-made laws and a natural law of universal validity,[20] but Gerhard Kittel states that the Stoic philosophers were not able to combine the concepts of νόμος (law) and φύσις (nature) to produce the concept of "natural law" in the sense that was made possible by Judeo-Christian theology.[21]

As part of the Pauline theology of salvation by grace, Paul writes in Ephesians 2:3 that "we all once lived in the passions of our flesh, carrying out the desires of the body and the mind, and were by nature children of wrath, like the rest of mankind. In the next verse he writes, "by grace you have been saved."[22][23]

In patristic theology

[edit]Theologians of the early Christian period differed in the usage of this term. In Antiochene circles, it connoted the humanity or divinity of Christ conceived as a concrete set of characteristics or attributes. In Alexandrine thinking, it meant a concrete individual or independent existent and approximated to hypostasis without being a synonym.[24] While it refers to much the same thing as ousia it is more empirical and descriptive focussing on function while ousia is metaphysical and focuses more on reality.[25] Although found in the context of the Trinitarian debate, it is chiefly important in the Christology of Cyril of Alexandria.[25]

In modern usage

[edit]The Greek adjective physikos is represented in various forms in modern English: As physics "the study of nature", as physical (via Middle Latin physicalis) referring both to physics (the study of nature, the material universe) and to the human body.[26] The term physiology (physiologia) is of 16th-century coinage (Jean Fernel). The term physique, for "the bodily constitution of a person", is a 19th-century loan from French.

In medicine the suffix -physis occurs in such compounds as symphysis, epiphysis, and a few others, in the sense of "a growth". The physis also refers to the "growth plate", or site of growth at the end of long bones.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b Things in, by or according to nature are φύσει (physei; DAT sg of physis). Things in, by or according to law, custom or convention are νόμῳ (nomōi; DAT sg of nomos).

- ^ Dunshirn, Alfred (2019): Physis [English version]. In: Kirchhoff, Thomas (ed.): Online Encyclopedia Philosophy of Nature / Online Lexikon Naturphilosophie. Heidelberg University Press. https://doi.org/10.11588/oepn.2019.0.66404: p.3

- ^ Discussed in Aristotle's works so titled, Physics and Metaphysics "Physis, translated since the Third Century B.C. usually as "nature" and less frequently as "essence", means one thing for the presocratic philosophers and quite another thing for Plato." Welch, Kathleen Ethel. "Keywords from Classical Rhetoric: The Example of Physis." Rhetoric Society Quarterly 17.2 (1987): 193–204. Print. The Pontifical Academy of Sciences. Evolving Concepts of Nature. Proceedings of the Plenary Session, 24–28 October 2014, Acta 23, Vatican City, 2015. link.

- ^ For the whole passage see Dunshirn, Alfred (2019): Physis [English version]. In: Kirchhoff, Thomas (ed.): Online Encyclopedia Philosophy of Nature / Online Lexikon Naturphilosophie. Heidelberg University Press. https://doi.org/10.11588/oepn.2019.0.66404: p.1

- ^ Ducarme, Frédéric; Couvet, Denis (2020). "What does 'nature' mean?". Palgrave Communications. 6 (14). Springer Nature. doi:10.1057/s41599-020-0390-y.

- ^ Odyssey 10.302-3: ὣς ἄρα φωνήσας πόρε φάρμακον ἀργεϊφόντης ἐκ γαίης ἐρύσας, καί μοι φύσιν αὐτοῦ ἔδειξε. (So saying, Argeiphontes [=Hermes] gave me the herb, drawing it from the ground, and showed me its nature.) Odyssey (ed. A.T. Murray).

- ^ Gerard Naddaf, The Greek Concept of Nature, SUNY Press, 2005, p. 3. Guthrie, W. K. C., Presocratic Tradition from Parmenides to Democritus (volume 2 of his History of Greek Philosophy), Cambridge UP, 1965.[page needed]

- ^ Dunkie, Roger (1986). "Philosophical background of the 5th Century B.C.". The Classical Origins of Western Culture: The Core Studies 1 Study Guide. Brooklyn College Core Curriculum Series. Brooklyn, NY: Brooklyn College. Retrieved 30 January 2012.

- ^ Gerard Naddaf, The Greek Concept of Nature (2005), 1f.

- ^ a b Atwill, Janet. "The Interstices of Nature, Spontaneity, and Chance." Rhetoric Reclaimed: Aristotle and the Liberal Arts Tradition. Ithaca, NY: Cornell UP, 1998. N. Print.

- ^ Dunshirn, Alfred (2019): Physis [English version]. In: Kirchhoff, Thomas (ed.): Online Encyclopedia Philosophy of Nature / Online Lexikon Naturphilosophie. Heidelberg University Press. https://doi.org/10.11588/oepn.2019.0.66404: p.4

- ^ Balz, Horst Robert (2004-01-14). Exegetical dictionary of the New Testament. Michigan1994: William B. Eerdmans Publishing Company. ISBN 9780802828033.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location (link) - ^ Verbrugge, Verlyn D. (2000). New International Dictionary of New Testament Theology. Zondervan.

- ^ Romans 2:14

- ^ Danker, Frederick W. (2014). A Greek-English lexicon of the New Testament and other early Christian literature. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- ^ Romans 1:26–1:27

- ^ Danker, Frederick W. (2014). A Greek-English lexicon of the New Testament and other early Christian literature. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- ^ 1 Corinthians 11:13

- ^ a b Balz, Horst Robert (2004-01-14). Exegetical dictionary of the New Testament. Michigan1994: William B. Eerdmans Publishing Company. ISBN 9780802828033.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location (link) - ^ Roberts, John (2007). "Law of nature". Oxford Dictionary of the Classical World. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-280146-3. Archived from the original on 2017-12-01. Retrieved 2 May 2017.

- ^ Kittel, Gerhard. Theological Dictionary of the New Testament. Michigan: Eerdman's Publishing Company.

- ^ Ephesians 2:3–2:4

- ^ Verbrugge, Verlyn D. (2000). New International Dictionary of New Testament Theology. Zondervan.

- ^ Kelly, J.N.D. Early Christian Doctrines A&C Black(1965) p.318

- ^ a b Prestige, G.L. God in Patristic Thought, SPCK (1964), p.234

- ^ Harper, Douglas. "Physical". Online Etymology Dictionary. Retrieved 20 September 2006.

Further reading

[edit]- Brock, Sebastian P. (2016). "Miaphysite, not Monophysite!". Cristianesimo Nella Storia. 37 (1): 45–52. ISBN 9788815261687.

- Loon, Hans van (2009). The Dyophysite Christology of Cyril of Alexandria. Leiden-Boston: Brill. ISBN 978-9004173224.

- Meyendorff, John (1983) [1974]. Byzantine Theology: Historical Trends and Doctrinal Themes (2nd revised ed.). New York: Fordham University Press. ISBN 9780823209675.

- Meyendorff, John (1989). Imperial Unity and Christian Divisions: The Church 450–680 A.D. Crestwood, NY: St. Vladimir's Seminary Press. ISBN 9780881410563.

- Weedman, Mark (2007). The Trinitarian Theology of Hilary of Poitiers. Leiden-Boston: Brill. ISBN 978-9004162242.

- Winkler, Dietmar W. (1997). "Miaphysitism: A New Term for Use in the History of Dogma and in Ecumenical Theology". The Harp. 10 (3): 33–40.

External links

[edit]- Dunshirn, Alfred 2019: Physis [English version]. In: Kirchhoff, Thomas (ed.): Online Encyclopedia Philosophy of Nature / Online Lexikon Naturphilosophie. Heidelberg University Press. https://doi.org/10.11588/oepn.2019.0.66404