Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

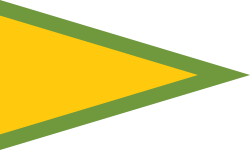

Post-Angkor period

View on Wikipedia

Key Information

| History of Cambodia |

|---|

| Early history |

| Post-Angkor period |

| Colonial period |

| Independence and conflict |

| Peace process |

| Modern Cambodia |

| By topic |

|

|

The post-Angkor period of Cambodia (Khmer: ប្រទេសកម្ពុជាក្រោយសម័យអង្គរ), also called the Middle period,[1] refers to the historical era from the early 15th century to 1863, the beginning of the French protectorate of Cambodia. As reliable sources (for the 15th and 16th centuries, in particular) are very rare, a defensible and conclusive explanation that relates to concrete events that manifest the decline of the Khmer Empire, recognised unanimously by the scientific community, has so far not been produced.[2][3] However, most modern historians have approached a consensus in which several distinct and gradual changes of religious, dynastic, administrative and military nature, environmental problems and ecological imbalance[4] coincided with shifts of power in Indochina and must all be taken into account to make an interpretation.[5][6][7] In recent years scholars' focus has shifted increasingly towards human–environment interactions and the ecological consequences, including natural disasters, such as flooding and droughts.[8][9][10][11]

Stone epigraphy in temples, which had been the primary source for Khmer history, is already a rarity throughout the 13th century, ends in the third decade of the fourteenth, and does not resume until the mid-16th century. Recording of the Royal Chronology discontinues with King Jayavarman IX Parameshwara (or Jayavarma-Paramesvara), who reigned from 1327 to 1336. There exists not a single contemporary record of even a king’s name for over 200 years. Construction and maintenance of monumental temple architecture had come to a standstill after Jayavarman VII's reign. According to author Michael Vickery there only exist external sources for Cambodia’s 15th century, the Chinese Ming Shilu ("Veritable Records") and the earliest Royal Chronicle of Ayutthaya,[12] which must be interpreted with greatest caution.[13]

The single incident which undoubtedly reflects reality, the central reference point for the entire 15th century, is a Siamese intervention of some undisclosed nature at the capital Yasodharapura (Angkor Thom) around the year 1431. Historians relate the event to the shift of Cambodia's political centre southward to the river port region of Phnom Penh and later Longvek.[14][15]

Sources for the 16th century are more numerous, although still coming from outside of Cambodia. The kingdom's new capital was Longvek, on the Mekong, which prospered as an integral part of the 16th century Asian maritime trade network,[16][17] via which the first contact with European explorers and adventurers occurred.[18] The rivalry with the Ayutthaya Kingdom in the west resulted in several conflicts, including the Siamese conquest of Longvek in 1594. The Vietnamese southward expansion reached Prei Nokor/Saigon at the Mekong Delta in the 17th century. This event initiates the slow process of Cambodia losing access to the seas and independent marine trade.[19]

Siamese and Vietnamese dominance intensified during the 17th and 18th century, provoking frequent displacements of the seat of power as the Khmer monarch's authority decreased to the state of a vassal. Both powers alternately demanded subservience and tribute from the Cambodian court.[20] In the mid 19th century, with dynasties in Siam and Vietnam firmly established, Cambodia was placed under joint suzerainty between the two regional empires, thereby the Cambodian kingdom lost its national sovereignty. British agent John Crawfurd states: "...the King of that ancient Kingdom is ready to throw himself under the protection of any European nation..."[citation needed] To save Cambodia from being incorporated into Vietnam and Siam, King Ang Duong agreed to colonial France's offers of protection, which took effect with King Norodom Prohmbarirak signing and officially recognising the French protectorate on 11 August 1863.[21]

Historical background and causes

[edit]The Khmer Empire had steadily gained hegemonic power over most of mainland Southeast Asia since its early days in the 8th and 9th centuries. Rivalries and wars with its western neighbour, the Pagan Kingdom of the Mon people of modern-day Burma were less numerous and decisive than those with Champa to the east. The Khmer and Cham Hindu kingdoms remained for centuries preoccupied with each other's containment and it has been argued that one of the Khmer's military objectives was "...in the reigns of the Angkor kings Suryavarman II and Jayavarman VII." the conquest of the Cham ports, "...important in the international trade of the time".[22] Even though the Khmer suffered a number of serious defeats, such as the Cham invasion of Angkor in 1177, the empire quickly recovered, capable to strike back, as it was the case in 1181 with the invasion of the Cham city-state of Vijaya.[23][24]

Mongol incursions into southern China and political and cultural pressure caused the southward migration of the Tai people and Thai people and their settling on the upper Chao Phraya River in the 12th century.[25] The Sukhothai Kingdom and later the Ayutthaya Kingdom were established and "...conquered the Khmers of the upper and central Menam [Chao Phraya River] valley and greatly extended their territory..."[26]

Military setbacks

[edit]Although a number of sources, such as the Cambodian Royal Chronicles and the Royal chronicles of Ayutthaya[27] contain recordings of military expeditions and raids with associated dates and the names of sovereigns and warlords, several influential scholars, such as David Chandler and Michael Vickery doubt the accuracy and reliability of these texts.[28][29][30] Other authors, however, criticise this rigid "overall assessment".[31]

David Chandler states in A Global Encyclopedia of Historical Writing, Volume 2: "Michael Vickery has argued that Cambodian chronicles, including this one, that treat events earlier than 1550 cannot be verified, and were often copied from Thai chronicles about Thailand..."[28][32] Linguist Jean-Michel Filippi concludes: "The chronology of Cambodian history itself is more a chrono-ideology with a pivotal role offered to Angkor."[33] Similarities apply to Thai chronological records, with the notable example of the Ramkhamhaeng controversy.[34][35]

According to the Siamese Royal chronicles of Paramanuchitchinorot, clashes occurred in 1350, around 1380, 1418 and 1431.[36][37]

"In 1350/51; probably April 1350 King Ramadhipati had his son Ramesvara attack the capital of the King of the Kambujas (Angkor) and had Paramaraja (Pha-ngua) of Suphanburi advance to support him. The Kambuja capital was taken and many families were removed to the capital Ayudhya.

At that time, [around 1380] the ruler of Kambuja came to attack Chonburi, to carry away families from the provinces eastwards to Chanthaburi, amounting to about six or seven thousand persons who returned [with the Cambodian armies] to Kambuja. So the King attacked Kambuja and, having captured it, returned to the capitol.[sic]

Then [1418] he went to attack Angkor, the capital of Kambuja, and captured it."

Land or people debate

[edit]Siamese sources record the habit of capturing sizeable numbers of inhabitants from the capital cities and centres of civilisation of the defeated parties in Chiang Mai and Angkor which can be assumed to have accelerated the cultural decline.[37][38]

Author Michael Vickery debates the degree of importance of this subject in his publication "Two Historical Records of the Kingdom of Vientiane - Land or People?": "It is not at all certain that Angkor desired manpower in central Thailand, rather than simply control over the rich agricultural resources." and "...whether the political economy of early Southeast Asia resulted in rulers being more concerned with control of land or control of people..." and "...both sides of this discussion have offered ad hoc, case-by-case pronunciamentos, which are then repeated like mantra... Critical discussion of the question is long overdue..."[citation needed]

- Contrary views

Author Akin Rabibhadana, who quotes Ram Khamhaeng: "One particular characteristic of the historical Southeast Asian mainland states was the lack of manpower. The need for manpower is well illustrated by events following each war between Thailand and her neighbours. The victorious side always carried off a large number of people from the conquered territory. Whole villages were often moved into the territory of the conqueror, where they were assimilated and became the population of the conqueror."[citation needed]

David K. Wyatt: "As much as anything else, the Tai müang was an instrument for the efficient use of manpower in a region where land was plentiful in relation to labor and agricultural technology."[citation needed]

Baker and Phongpaichit argues that, "War in the region [Southeast Asia] was... an enterprise to acquire wealth, people, and scarce urban resources."[39]

Bronson states, "No farmers in any region outside southern and eastern Asia could produce as much food with as little labor from the same amount of land."[40]

And Aung-Thwin wrote: "Much of the warfare of early Southeast Asia witnessed the victor carrying off half the population of the vanquished foe and later resettling them on his own soil. Pagan was located in the dry belt of Burma, and depended mainly upon irrigated agriculture for its economic base. Land was plentiful but labor was extremely difficult to obtain."[41]

Dynastic and religious factors

[edit]The complete transition from the early Khmer kingdom to the firm establishment of the Mahidharapura dynasty (first king Jayavarman VI, 1080 to 1107), which originated west of the Dângrêk Mountains at Phimai in the Mun river valley[42] lasted several decades. Some historians argue, that these kings failed to acquire absolute central administrative control and had limited access to local resources. The dynasty discontinued "ritual policy" and genealogical traditions. Further momentum ensued as Mahayana Buddhism was eventually tolerated and several Buddhist kings emerged, including Suryavarman I, Rajendravarman II and Jayavarman VII.[43]

These rulers were not considered, and did not consider themselves, as divine, which lead to a shift in perception of royal authority, central power and a loss of dynastic prestige with respect to foreign rulers. Effectively the royal subjects were given permission to re-direct attention and support from the Hindu state of military dominance with its consecrated leader, the "Varman"—protector king, towards the inner-worldly alternative with the contradictory teachings of the Buddhist temple. Indravarman III (c. 1295-1308) adopted Theravada Buddhism as the state religion,[44] which implied an even more passive, introverted focus towards individual and personal responsibility to accumulate merit to achieve nirvana.[45]

Miriam T. Stark argues that competition and rivalries in royal succession, usurpers and "second grade" rulers characterised the kingdom since the 9th century. Periods of "...consolidation alternated with political fragmentation [as] only few rulers were able to wrest control from the provincial level".[46]

Debate remains on the progress of the imperial society as the kingdom grew and occupied foreign lands. Authors present numerous theories about the relationship between Southeast Asian kings and the populace's loyalties, nature and degree of identity, the Mandala concept and the effects of changing state-religion. Scholar Ben Kiernan highlights a tendency to identify with a universal religion rather than to adhere to the concept of a people or nation, as he refers to author Victor Lieberman in: Blood and Soil: Modern Genocide 1500-2000 "[local courts make]...no formal demand, that rulers be of the same ethnicity as their subjects"[47][48]

Environmental problems and infrastructural breakdown

[edit]Historians increasingly maintain the idea that decline was caused by progressing ecological imbalance of the delicate irrigation network and canal system of "...a profoundly ritualized, elaborate system of hydraulic engineering..."[49] at Angkor's Yasodharapura. Recent studies indicate that the irrigation system was overworked and gradually started to silt up, amplified by large scale deforestation.[50] Permanent monument construction projects and maintenance of temples instead of canals and dykes put an enormous strain on the royal resources and drained thousands of slaves and common people from the public workforce and caused tax deficits.[51]

Author Heng L. Thung addressed common sense in "Geohydrology and the decline of Angkor" as he sums things up: "...the preoccupation of the Khmers with the need to store water for the long dry season. Each household needed a pond to provide drinking and household water for both man and beast. The barays [reservoirs] of Angkor were simply the manifestation of the need of an urban population. Water was the fountain of life for Angkor; a disruption in its supply would be fatal."[52]

Recent Lidar (Light detection and ranging) Geo-Scans of Angkor have produced new data, that have caused several "Eureka moments" and "have profoundly transformed our understanding of urbanism in the region of Angkor".[53] Results of dendrochronological studies imply prolonged periods of drought between the 14th and 15th centuries.[54] As a result, recent re-interpretations of the epoch put greater emphasis on human–environment interactions and the ecological consequences.[8]

Growth of international maritime trade

[edit]Some historians have argued that an important reason for the Angkor court's move to the lower Mekong Delta was due to the growth of international maritime trade with the rest of the world. Angkor, being primarily inland and largely agricultural, became increasingly irrelevant to the global markets in comparison to the later maritime Cambodian capitals at Longvek, Oudong, and later Phnom Penh.[55][56][57]

Chaktomuk era

[edit]Following the abandonment of the capital Yasodharapura[58] and the Angkorian sites, the Angkor elites established a new capital around two-hundred kilometres to the south-east on the site which is modern day Phnom Penh, at the confluence of the Mekong and the Tonle Sap river. Thus, it controlled the river commerce of the Khmer heartland, upper Siam and the Laotian kingdoms with access, by way of the Mekong Delta, to the international trade routes that linked the Chinese coast, the South China Sea, and the Indian Ocean. Unlike its inland predecessor, this society was more open to the outside world and relied mainly on commerce as the source of wealth. The adoption of maritime trade with China during the Ming dynasty (1368–1644) provided lucrative opportunities for members of the Cambodian elite who controlled royal trading monopolies.[59]

Historians consent that as the capital ceased to exist, the temples at Angkor remained as central for the nation as they always had been. David P. Chandler: "The 1747 inscription is the last extensive one at Angkor Wat and reveals the importance of the temple in Cambodian religious life barely a century before it was "discovered" by the French."[60]

Longvek era

[edit]

King Ang Chan I (1516–1566) moved the capital from Phnom Penh north to Longvek at the banks of the Tonle Sap river. Trade was an essential feature and "...even though they appeared to have a secondary role in the Asian commercial sphere in the 16th century, the Cambodian ports did indeed thrive." Products traded there included precious stones, metals, silk, cotton, incense, ivory, lacquer, livestock (including elephants), and rhinoceros horn.

First contact with the West

[edit]Messengers of Portuguese admiral Alfonso de Albuquerque, conqueror of Malacca arrived in Indochina in 1511, the earliest documented official contact with European sailors. By the late sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries, Longvek maintained flourishing communities of Chinese, Indonesians, Malays, Japanese, Arabs, Spaniards, English, Dutch and Portuguese traders.[61][62]

Christian missionary activities began in 1555 with Portuguese clergyman friar Gaspar da Cruz,[63] the first to set foot in the Kingdom of Cambodia, who "...wasn’t able to spread the word of God and he was seriously ill[sic]." Subsequent attempts did not yield any results that could substantiate a congregation.[64][65][66]

Military resurgence and fall

[edit]

Cambodia was a potent rival of the Ayutthaya Kingdom in the 16th century.[67] Following the Burmese subjugation of Ayutthaya in 1569, Cambodia launched numerous military expeditions into a weakened Siam between the 1560s and the 1580s.[68] In 1570, Cambodian forces besieged Ayutthaya, but were repulsed by fierce resistance and the rainy season floods.[69] In 1581, Cambodia sacked the Siamese city of Phetchaburi and emptied the city of its inhabitants.[70]

Meanwhile, in 1572 and 1573-75, the king of Lan Xang sent two invasions to subjugate Longvek. Both invasions ended in complete failure and the Lan Xang king was assumed to have died in the conflict.[71]

In retribution for multiple Longvek raids on Ayutthaya, in 1587, Cambodia was attacked by the Siamese Crown Prince Naresuan, who failed to besiege the city of Longvek.[72] In 1594, Longvek was successfully captured and sacked by Siamese forces and Cambodian royals were taken hostage and relocated to the court of Ayutthaya.[73]

The initially fortunate circumstances of some members of the Longvek royal family, managing to seek refuge at the Lao court of Vientiane, ended tragically. The refugees never returned to demand their claims. Their sons, born and raised in Lan Xang, were alienated and while "moderately" manipulated, engaged in local court politics with the exiled Cambodians in Ayutthaya and had the ruling vassal King Ram I, who was of lower birth, killed with the help of Spanish and Portuguese sailors.[74]

Shortly after they were killed and defeated in the Cambodian–Spanish War, with foreign hands—Malays and Chams—involved. This pattern of royal indignity is noticeable in its continuity during the 17th, 18th and 19th centuries, the Vietnamese court in Hue joining in as yet another stage of royal drama.[75] Royal contender's quarrels often prevented any chance of restoring an effective King of competitive authority for decades.[76][77]

Srey Santhor era

[edit]Kings Preah Ram I and Preah Ram II moved the capital several times and established their royal capitals at Tuol Basan (Srey Santhor) around 40 kilometres north-east of Phnom Penh, later Pursat, Lavear Em and finally Oudong.[78] In 1596 Spanish and Portuguese conquistadores from Manila raided and razed Srei Santhor.[79]

Lvea Aem era

[edit]In 1618, King Chey Chettha II stopped sending tribute to Ayutthaya and reasserted Cambodian independence.[80] A Siamese expedition in 1621-22 to reconquer Cambodia failed in dramatic fashion.[81]

Oudong era

[edit]

By the 17th and 18th centuries, Siam and Vietnam increasingly fought over control of the fertile Mekong basin, enhancing pressure on an unstable Cambodia.[82][83][84] The 17th century was also the beginning of direct relations between post-Angkor Cambodia and Vietnam, that is the war between Nguyễn lords who ruled central and southern Vietnam and Trịnh lords in the north.[85]

Henri Mouhot: "Travels in the Central Parts of Indo-China" 1864

"Udong, the present capital of Cambodia, is situated north-east of Komput, and is four miles and a half from that arm of the Mekon which forms the great lake...Every moment I met mandarins, either borne in litters or on foot, followed by a crowd of slaves carrying various articles; some, yellow or scarlet parasols, more or less large according to the rank of the person; others, boxes with betel. I also encountered horsemen, mounted on pretty, spirited little animals, richly caparisoned and covered with bells, ambling along, while a troop of attendants, covered with dust and sweltering with heat, ran after them. Light carts, drawn by a couple of small oxen, trotting along rapidly and noisily, were here and there to be seen. Occasionally a large elephant passed majestically by. On this side were numerous processions to the pagoda, marching to the sound of music; there, again, was a band of ecclesiastics in single file, seeking alms, draped in their yellow cloaks, and with the holy vessels on their backs....The entire population numbers about 12,000 souls."[86]

However, Cambodia remained economically significant in the early part of the Oudong period. In the 17th century, the Japanese considered Cambodia to be a more important maritime power than Siam.[87]

Loss of the Mekong Delta

[edit]

By the late 15th century, the Vietnamese—descendants of the Sinic civilisation sphere—had conquered some of the territories of the principalities of Champa.[88] Some of the surviving Chams began their diaspora in 1471, many re-settling in Khmer territory.[89][90] However, the Cambodian Chronicle does not mention the Cham arrival in Cambodia until the 17th century.[91] The last remaining principality of Champa, Panduranga, survived until 1832. [92]

Traditional view

[edit]

In 1620 the Vietnamese on their southwards expansion (Nam tiến) had reached the Mekong Delta, a hitherto Khmer domain. Also in 1620 the Khmer king Chey Chettha II (1618–28) married a daughter of lord Nguyễn Phúc Nguyên, one of the Nguyễn lords, who held sway over southern Vietnam for most of the Lê dynasty era from 1428 to 1788. Three years later, king Chey Chettha allowed Vietnam to establish a custom-post at Prey Nokor, modern day Ho Chi Minh City. Vietnam after gaining independence from the Chinese now instituted its own version of the frontier policies of the Chinese empire and by the end of the 17th century, the region was under full Vietnamese administrative control. Cambodia's access to international sea trade was now hampered by Vietnamese taxes and permissions.[93]

Contrary views

[edit]The story of a Cambodian king falling in love with a Vietnamese princess, who requested and obtained Kampuchea Krom, the Mekong Delta for Vietnam is folklore, dismissed by scholars and not even mentioned in the Royal Chronicles.[94][95]

In the process of re-interpretation of the royal records and their rather doubtful contents, Michael Vickery again postulates that future publications take these contradicting facts into account: "First, the very concept of a steady Vietnamese "Push to the South" (nam tiến) requires rethinking. It was not steady, and its stages show that there was no continuing policy of southward expansion. Each move was ad hoc, in response to particular challenges..."[96]

Vickery additionally argues that Cambodia was never "cut off from maritime access to the outside world" in the 17th century, as argued by David Chandler.[97]

Mid 17th century–19th century

[edit]In 1642 Cambodian prince Ponhea Chan became king after overthrowing and assassinating king Outey. Malay Muslim merchants in Cambodia helped him in his takeover, and he subsequently converted to Islam from Buddhism, changed his name to Ibrahim, married a Malay woman and reigned as Ramathipadi I. His reign marked the historical apogee of Muslim rule in mainland Southeast Asia.

Ramathipadi defeated the Dutch East India Company in naval engagements of the Cambodian–Dutch War during 1643 and 1644.[98] Pierre de Rogemortes, the ambassador of the Company was killed alongside a third of his 432 men and it was not until two centuries later that Europeans played any important and influential role in Cambodian affairs.[99] In the 1670s the Dutch left all the trading posts they had maintained in Cambodia after the massacre in 1643.[100] The first Vietnamese military intervention took place in 1658-59, in which rebel Cambodian princes, Ibrahim Ramathipadi's own brothers, had requested military support to depose the Muslim ruler and restore Buddhism.

Siam, which might otherwise have been courted as an ally against Vietnamese incursions in the 18th century, was itself involved in prolonged conflicts with Burma and in 1767 the Siamese capital of Ayutthaya was completely destroyed. However, Siam recovered and soon reasserted its dominion over Cambodia. The youthful Khmer king Ang Eng (1779–96) was installed as monarch at Oudong while Siam annexed Cambodia's Battambang and Siem Reap provinces. The local rulers became vassals under direct Siamese rule.[101][102]

A renewed struggle between Siam and Vietnam for control of Cambodia and the Mekong basin in the early 19th century resulted in Vietnamese dominance over a Cambodian vassal king. Justin Corfield writes in "French Indochina": "[1807] the Vietnamese expanded their lands by establishing a protectorate over Cambodia. However king […] Ang Duong was keen on Cambodia becoming independent of [...] Thailand [...] and Vietnam [...] and sought help from the British in Singapore. When that failed, he enlisted the help of the French."[103]

Attempts to force Cambodians to adopt Vietnamese customs caused several rebellions against Vietnamese rule. The most notable took place from 1840 to 1841, spreading through much of the country.

Siam and Vietnam had fundamentally different attitudes concerning their relationship with Cambodia. The Siamese shared a common religion, mythology, literature, and culture with the Khmer, having adopted many religious and cultural practices.[104] The Thai Chakri kings followed the Chakravatin system of an ideal universal ruler, ethically and benevolently ruling over all his subjects. The Vietnamese enacted a civilising mission, as they viewed the Khmer people as culturally inferior and regarded the Khmer lands as legitimate site for colonisation by settlers from Vietnam.[105]

The territory of the Mekong Delta became a territorial dispute between Cambodians and Vietnamese. Cambodia gradually lost control of the Mekong Delta. By the 1860s French colonist had taken over the Mekong Delta and establish the colony of French Cochinchina.

Nguyen rule

[edit]As the Vietnamese empire consolidated itself over the eastern mainland under Gia Long and Minh Mang, Cambodia fell to the Vietnamese invasion in 1811. The invasion was initiated by the ruling king, King Ang Chan II's (r. 1806–35) request to Gia Long to suppress his own brothers, Ang Snguon and Ang Em, who were in rebellion against him. The two brothers fled to Thailand, while Ang Chan became a Vietnamese vassal.[106][107]

In 1820 Gia Long died and his fourth son Minh Mang inherited the throne. Both Minh Mang and his father were strong adherents of Confucianism, but Minh Mang was a sadistic isolationist and strong ruler. He removed the Viceroy of Cambodia and Saigon in 1832, triggered the pro-Catholic Lê Văn Khôi revolt against him in 1833. The Thai army, intended to support the rebellion, launched an offensive campaign against the Vietnamese on occupying Cambodia. This led Ang Chan to flee to Saigon, as Rama III promised to restore the Kingdom of Cambodia and punish the insolence of the Kingdom of Vietnam. In 1834, the rebellion in Southern Vietnam was suppressed, and Minh Mang ordered troops to launch the second invasion of Cambodia. This drove most of the Thai forces to the west and reinstalled Ang Chan as the puppet king in Phnom Penh, later succeeded by his daughter, Queen Ang Mey (r. 1835–41).[108] Later that year, the Tây Thành Province was established, the Vietnamese occupied Cambodia result in direct Vietnamese control. For the next six years, the Vietnamese emperor had tried to force the Cambodians to adopt Vietnamese culture by cultural assimilation, a progress that historian David P. Chandler called The Vietnamization of Cambodia.[109]

The death of Minh Mang in early 1841 halted the Vietnamization of Cambodia.[110] With 35,000 Thai troops, they took advantage of the dire situation in Vietnam, rushed into the Tây Thành Province, and were able to fend off Vietnamese counteroffensives in late 1845. The new Vietnamese emperor, Thieu Tri, readied to make peace with Siam, and in June 1847 a peace treaty was signed. The Kingdom of Cambodia under Ang Duong regained its independence after 36 years of brutal Vietnamese occupations and Siamese interventions.[111]

Consequences and conclusions

[edit]

European colonialism and Anglo-French rivalries

[edit]Admiral Léonard Charner proclaimed the formal annexation of three provinces of Cochinchina into the French Empire on 31 July 1861,[112] the beginning of the colonial era of France in South-East Asia. France's interference in Indochina was thus a fact and the colonial community pressing to establish a commercial network in the region based on the Mekong river, ideally linking up with the gigantic market of southern China.[113][114]

Dutch author H.Th. Bussemaker has argued that these French colonial undertakings and acquisitions in the region were mere reactions to or counter-measures against British geo-strategy and economic hegemony. "For the British, it was obvious that the French were trying to undercut British expansionism in India and China by interposing themselves in Indochina. The reason for this frantic expansionism was the hope that the Mekong river would prove to be navigable to the Chinese frontier, which then would open the immense Chinese market for French industrial goods."[115] To save the kingdom's national identity and integrity, King Ang Duong initiated secret negotiations in a letter to Napoleon III seeking to obtain some agreement of protection with France.

In June 1884, the French governor of Cochinchina, Charles Thomson went to Phnom Penh, Norodom's capital, and demanded approval of a treaty with Paris that promised far-reaching changes such as the abolition of slavery, the institution of private land ownership, and the establishment of French résidents in provincial cities. The king reluctantly signed the agreement. The Philaster Treaty of 1874 confirmed French sovereignty over the whole of Cochin China and on 16 November 1887 the Indo-Chinese Union was established.[116]

Continued debate over Post-Angkor historiography

[edit]

Archaeology of Cambodia is considered to be still in its infancy. The introduction of new methods of geochronology such as LIDAR-Scanning and Luminescence dating has revealed new sets and kinds of data and studies on climate—and environmental imbalances have become more numerous in recent years. Reflection of results obviously requires time, as in an article of the US National Academy of Sciences of the year 2010, the author complains: "Historians and archaeologists have, with a few notable exceptions only rarely considered the role played by environment and climate in the history of Angkor".[117]

Widely debated remain historiography, culturalism and other aspects of the historical sources as wide contradictions suggest.[118] Probably the greatest challenge is to synchronise all research with the conclusions of the neighbouring countries. Delicate issues exist that are rooted in this historical period (border disputes, cultural heritage), which are politically relevant and far from solved. Definitive conclusions with all contributing factors in a reasonable context are clearly future events.[119]

Miriam T. Stark in: "From Funan to Angkor Collapse and Regeneration in Ancient Cambodia"[120]

"...explaining why particular continuities and discontinuities characterize ancient Cambodia remains impossible without a more finely textured understanding of the archaeological record... Future work, that combines systematic archaeological research and critical documentary analysis can and should illuminate aspects of resilience and change..."

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "Murder and Mayhem in Seventeenth Century Cambodia - The so-called middle period of Cambodian history, stretching from... - Reviews in History". School of Advanced Study at the University of London. 28 February 2009. Archived from the original on 15 June 2015. Retrieved 14 June 2015.

- ^ "What the collapse of ancient capitals can teach us about the cities of today by Srinath Perur". The Guardian. 14 January 2015. Retrieved 27 June 2015.

- ^ "Cambodia and Its Neighbors in the 15th Century, Michael Vickery". Michael Vickery’s Publications. 1 June 2004. Retrieved 8 June 2015.

- ^ "Scientists dig and fly over Angkor in search of answers to golden city's fall by Miranda Leitsinger". The San Diego Union-Tribune. 13 June 2004. Archived from the original on 24 December 2013. Retrieved 19 June 2015.

- ^ "What Caused the End of the Khmer Empire By K. Kris Hirst". about.com. Retrieved 11 June 2015.

- ^ "THE DECLINE OF ANGKOR". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 11 June 2015.

- ^ "The emergence and ultimate decline of the Khmer Empire was paralleled with development and subsequent change in religious ideology, together with infrastructure that supported agriculture" (PDF). Studies Of Asia. Retrieved 11 June 2015.

- ^ a b "Laser scans flesh out the saga of Cambodias 1200 year old lost city". Khmer Geo. Archived from the original on 14 June 2015. Retrieved 11 June 2015.

- ^ "Possible new explanation found for sudden demise of Khmer Empire". Phys org. 3 January 2012. Retrieved 11 June 2015.

- ^ "The emergence and ultimate decline of the Khmer Empire - ...the Empire experienced two lengthy droughts, during c.1340-1370 and also c.1400-1425..." (PDF). Studies of Asia. Retrieved 19 June 2015.

- ^ Buckley, Brendan M.; Anchukaitis, Kevin J.; Penny, Daniel; Fletcher, Roland; Cook, Edward R.; Sano, Masaki; Nam, Le Canh; Wichienkeeo, Aroonrut; Minh, Ton That; Hong, Truong Mai (13 April 2010). "Climate as a contributing factor in the demise of Angkor, Cambodia". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 107 (15). National Academy of Sciences: 6748–6752. Bibcode:2010PNAS..107.6748B. doi:10.1073/pnas.0910827107. PMC 2872380. PMID 20351244.

- ^ "Mak Phœun: Histoire du Cambodge de la fin du XVIe au début du XVIIIe siècle" (PDF). Michael Vickery. Retrieved 11 June 2015.

- ^ "The Ming Shi-lu as a Source for the Study of Southeast Asian History". Southeast Asia in the Ming Shi-lu. Archived from the original on 22 June 2015. Retrieved 12 June 2015.

- ^ "Kingdom of Cambodia - 1431-1863". GlobalSecurity. Retrieved 12 June 2015.

- ^ Marlay, Ross; Neher, Clark D. (1999). Patriots and Tyrants: Ten Asian Leaders By Ross Marlay, Clark D. Nehe. Rowman & Littlefield. ISBN 9780847684427. Retrieved 12 June 2015.

- ^ "Giovanni Filippo de Marini, Delle Missioni... Chapter VII - Mission of the Kingdom of Cambodia by Cesare Polenghi - It is considered one of the most renowned for trading opportunities: there is abundance..." (PDF). The Siam Society. Retrieved 1 July 2015.

- ^ Reid, Anthony (August 2000). Charting the Shape of Early Modern Southeast Asia By Anthony Reid. Silkworm Books. ISBN 9781630414818. Retrieved 14 June 2015.

- ^ "Maritime Trade in Southeast Asia during the Early Colonial Period" (PDF). University of Oxford. Retrieved 12 June 2015.

- ^ Church, Peter (3 February 2012). MA Short History of South-East Asia edited by Peter Church. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 9781118350447. Retrieved 12 June 2015.

- ^ Ooi, Keat Gin (2004). Southeast Asia: A Historical Encyclopedia, from Angkor Wat to East... Volume 1. Bloomsbury Academic. ISBN 9781576077702. Retrieved 7 June 2015.

- ^ "London Company's Envoys Plot Siam" (PDF). Siamese Heritage. Retrieved 7 May 2015.

- ^ "Two Historical Records of the Kingdom of Vientiane - That was probably also the reason for the Cambodian conquests in Champa in the reigns of the Angkor kings Suryavarman II and Jayavarman VII" (PDF). Michael Vickery’s Publications. Retrieved 30 June 2015.

- ^ "Angkor Wat: equated with the quintessence of Cambodian culture for more than a century - The Cham fleet sailed up the Mekong River...The reaction was very quick..." The Phnom Penh Post. 14 June 2013. Retrieved 21 June 2015.

- ^ "Bayon: New Perspectives Reconsidered Michael Vickery" (PDF). Michael Vickery’s Publications. Retrieved 26 June 2015.

- ^ "A Short History of South East Asia Chapter 3. The Repercussions of the Mongol Conquest of China ...The result was a mass movement of Thai peoples southwards..." (PDF). Stanford University. Retrieved 26 June 2015.

- ^ Briggs, Lawrence Palmer (1948). "Siamese Attacks On Angkor Before 1430". The Far Eastern Quarterly. 8 (1). Association for Asian Studies: 3–33. doi:10.2307/2049480. JSTOR 2049480. S2CID 165680758.

- ^ "Siam Society Books - The Royal Chronicles of Ayutthaya - A Synoptic Translation by Richard D. Cushman". Siam Society. Retrieved 20 June 2015.

- ^ a b Woolf, D. R. (3 June 2014). A Global Encyclopedia of Historical Writing, Volume 2 - Tiounn Chronicle. Routledge. ISBN 9781134819980. Retrieved 19 May 2015.

- ^ "Cambodia's cultural heritage considerations in Area Studies by Aratoi Hisao". googleusercontent.com. Retrieved 12 March 2015.

- ^ "Essay on Cambodian History from the middle of the 14 th to the beginning of the 16 th Centuries According to the Cambodian Royal Chronicles by NHIM Sotheavin - So far, the reconstruction of history from the middle of the 14 th to the beginning of the 16 th centuries is locked in a sort of unsolved state, since local sources prove inadequate and references from foreign sources are of little use" (PDF). Sophia Asia Center. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2 April 2015. Retrieved 1 July 2015.

- ^ Bourdonneau, Eric (September 2004). "Culturalism and historiography of ancient Cambodia: about prioritizing sources of Khmer history - Ranking Historical Sources and the Culturalist Approach in the Historiography of Ancient Cambodia by Eric Bourdonneau - 29 Also this material is sparse..." Moussons. Recherche en Sciences Humaines Sur l'Asie du Sud-Est (7). Presses Universitaires de Provence: 39–70. doi:10.4000/moussons.2469. Retrieved 3 July 2015.

- ^ "The historical Records of Ayudhya...Blamed on the invasion of Pagan in 1767, all Ayudhya's past records were assumed perished during its fall to the Burmese attack". Khmer heritage. 31 May 2015. Retrieved 20 June 2015.

- ^ "Angkor Wat: equated with the quintessence of Cambodian culture for more than a century - Behind the mythical towers: Cambodian history". Phnom Penh Post. 14 June 2013. Retrieved 20 June 2015.

- ^ "A king and a stone - Nineteenth century or twelfth? When the Thai script was first inscribed has much to do with how history is used politically by Rahul Goswami". Khaleej Times. 29 November 2014. Retrieved 20 June 2015.

- ^ "Recreations epigraphic (2 2). Epigraphic western: the case of Ramkhamhaeng by Jean-Michel Filippi". Kampotmuseum. 28 June 2012. Retrieved 20 June 2015.

- ^ "The Abridged Royal Chronicle of Ayudhya - In 712 of the Era, Year of the Tiger..." (PDF). The Siam Society. Retrieved 12 June 2015.

- ^ a b "History of Ayutthaya - Dynasties - King Ramesuan". History of Ayutthaya. Retrieved 20 June 2015.

- ^ "The Abridged Royal Chronicle of Ayudhya - Then he went to attack Chiangmai. A great many Lao families were brought away to the capitol." (PDF). The Siam Society. Retrieved 12 June 2015.

- ^ Baker, Chris; Phongpaichit, Pasuk (11 May 2017). A History of Ayutthaya. Cambridge University Press. p. 259. ISBN 978-1-107-19076-4.

- ^ Baker, Chris; Phongpaichit, Pasuk (11 May 2017). A History of Ayutthaya. Cambridge University Press. p. 4. ISBN 978-1-107-19076-4.

- ^ "Two Historical Records of the Kingdom of Vientiane (pp.2-5)" (PDF). Michael Vickery’s Publications. Retrieved 29 June 2015.

- ^ Higham, Charles (14 May 2014). Encyclopedia of Ancient Asian Civilizations By Charles Higham Mahidharapura dynasty. Infobase. ISBN 9781438109961. Retrieved 18 June 2015.

- ^ Marr, David G.; Milner, Anthony Crothers (1986). Southeast Asia in the 9th to 14th Centuries edited by David G. Marr, Anthony Crothers Milner. Institute of Southeast Asian Studies. ISBN 9789971988395. Retrieved 18 June 2015.

- ^ "Comparative timeline of Khmer Empire and Europe Theravada Buddhism became the state religion" (PDF). Australian Government Department of Education. Retrieved 20 June 2015.

- ^ "The emergence and ultimate decline of the Khmer Empire - Many scholars attribute the halt of the development of Angkor to the rise of Theravada..." (PDF). Studies Of Asia. Retrieved 11 June 2015.

- ^ "From Funan to Angkor Collapse and Regeneration in Ancient Cambodia by Miriam T. Stark p. 162" (PDF). University of Hawaii. Archived from the original (PDF) on 23 September 2015. Retrieved 29 June 2015.

- ^ Kiernan, Ben (2008). Blood and Soil: Modern Genocide 1500-2000. Melbourne Univ. ISBN 9780522854770. Retrieved 11 June 2015.

- ^ "Strange Parallels: Volume 1, Integration on the Mainland: Southeast Asia in Global Context, c.800-1830 by Victor Lieberman" (PDF). University of Michigan. Retrieved 11 June 2015.

- ^ "The water management network of Angkor, Cambodia Roland Fletcher Dan Penny, Damián Evans, Christophe Pottier, Mike Barbetti, Matti Kummu, Terry Lustig & Authority for the Protection and Management of Angkor and the Region of Siem Reap (APSARA) Department of Monuments and Archaeology Team" (PDF). University of Washington. Retrieved 26 June 2015.

- ^ "The architects of Cambodia's famed Angkor – the world's most extensive medieval "hydraulic city" – unwittingly engineered its environmental collapse". ScienceDaily. 12 September 2007. Retrieved 19 June 2015.

- ^ Damme, Thomas Van (January 2011). "The Collapse of the Khmer Empire by Thomas Van Damme". academia.edu. Retrieved 20 June 2015.

- ^ Thung, Heng L. "Geohydrology and the Decline of Angkor" (PDF). Khamkoo. Archived from the original (PDF) on 29 June 2016. Retrieved 29 June 2015.

- ^ Evans, DH; Fletcher, RJ; Pottier, C; Chevance, JB; Soutif, D; Tan, BS; Im, S; Ea, D; Tin, T; Kim, S; Cromarty, C; De Greef, S; Hanus, K; Bâty, P; Kuszinger, R; Shimoda, I; Boornazian, G (11 July 2013). "Uncovering archaeological landscapes at Angkor using lidar". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 110 (31): 12595–600. Bibcode:2013PNAS..11012595E. doi:10.1073/pnas.1306539110. PMC 3732978. PMID 23847206.

- ^ "The Collapse of Angkor – Evidence for a Long Term Drought – an extended drought between the 14th and 15th centuries at Angkor". About Education. Retrieved 3 July 2015.

- ^ Vickery, Michael (2005). "A Misstep Toward a New History of Cambodia: A Review Article". Zeitschrift der Deutschen Morgenländischen Gesellschaft. 155 (1): 247. ISSN 0341-0137. JSTOR 43381446.

The capital moved from Angkor to the Phnom Penh region, probably...in connection with the growth of international maritime trade.

- ^ Lieberman, Victor (26 May 2003). Strange Parallels: Volume 1, Integration on the Mainland: Southeast Asia in Global Context, c.800–1830. Cambridge University Press. p. 240. ISBN 978-1-139-43762-2.

...the subsequent effective transfer of the capital to the more commercially viable site of Phnom Penh marked the eclipse of pro-Angkor elements within the Khmer elite.

- ^ Ebihara, May (1984). "Societal Organization in Sixteenth and Seventeenth Century Cambodia". Journal of Southeast Asian Studies. 15 (2): 282. doi:10.1017/S0022463400012522. ISSN 0022-4634. JSTOR 20070596.

The shift of the capital from Angkor...may reflect...Cambodia's transition to a "trading kingdom" with increasing involvement with the outside world.

- ^ "Yasodharapura, revived in literature ...Yasodharapura, the first capital of the Khmer empire, was razed by the Siamese..." The Japan Times. 23 September 2007. Retrieved 27 June 2015.

- ^ "A Brief History of Phnom Penh - Chaktomuk..." anby Publications. Retrieved 26 June 2015.

- ^ "An Eighteenth Century Inscription From Angkor Wat by David P. Chandler" (PDF). The Siam Society. Retrieved 29 June 2015.

- ^ "Murder and Mayhem in Seventeenth Century Cambodia". nstitute of Historical Research (IHR). Retrieved 26 June 2015.

- ^ "Maritime Trade in Southeast Asia during the Early Colonial Period ...transferring the lucrative China trade to Cambodia..." (PDF). Oxford Centre for Maritime Archaeology University of Oxford. Retrieved 26 June 2015.

- ^ Justin Corfield (13 October 2009). The History of Cambodia. ABC-CLIO. pp. 12–. ISBN 978-0-313-35723-7.

- ^ "The Jesuits in Cambodia: A Look Upon Cambodian Religiousness (2nd half of the 16th century to the 1st quarter of the 18th century)—he wasn't able to spread the word of God and he was seriously ill, he quickly left the region without doing much and not baptizing more than a heathen" (PDF). Universidad Autónoma del Estado de México. Retrieved 1 July 2015.

- ^ Boxer, Charles Ralph; Pereira, Galeote; Cruz, Gaspar da; Rada, Martín de (1953), South China in the sixteenth century: being the narratives of Galeote Pereira, Fr. Gaspar da Cruz, O.P. [and] Fr. Martín de Rada, O.E.S.A. (1550-1575), Issue 106 of Works issued by the Hakluyt Society, Printed for the Hakluyt Society, pp. lix, 59–63

- ^ "The Philippine islands, 1493-1803...the expedition of 1596 to Cambodia..." Archive Org. Retrieved 26 June 2015.

- ^ Briggs, Lawrence Palmer (1946). "The Treaty of March 23, 1907 Between France and Siam and the Return of Battambang and Angkor to Cambodia". The Far Eastern Quarterly. 5 (4): 441. doi:10.2307/2049791. ISSN 0363-6917. JSTOR 2049791.

After the Khmer armies had been driven out of the Menam valley, they seem to have abandoned the upper and middle Mekong to the Laotians and to have withdrawn to the territory which was predominantly Khmer-with the Se Mun valley and Korat-Jolburi-Chantabun as a frontier. For two cen- turies, they fought Siam successfully for these frontiers. Once-in 1430-31 -the Siamese captured Angkor and seated a Siamese puppet on the throne. But the Cambodians reconquered their capital the next year; and, although they moved the capital to Phnom Penh, they did not abandon their old frontiers, but continued to fight for them during the sixteenth century, some- times in alliance with the Burmese, who twice sacked the Siamese capital.

- ^ Baker, Chris; Phongpaichit, Pasuk (11 May 2017). A History of Ayutthaya. Cambridge University Press. p. 114. ISBN 978-1-107-19076-4.

- ^ Smith, John (2019). "State, Community, and Ethnicity in Early Modern Thailand, 1351-1767" (PDF). University of Michigan Dissertation: 100.

- ^ Baker, Chris; Phongpaichit, Pasuk (11 May 2017). A History of Ayutthaya. Cambridge University Press. p. 114. ISBN 978-1-107-19076-4.

- ^ Sotheavin, Nhim. "Factors that Led to the Change of the Khmer Capitals from the 15th to 17th century" (PDF): 84-85.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Baker, Chris; Phongpaichit, Pasuk (11 May 2017). A History of Ayutthaya. Cambridge University Press. p. 115. ISBN 978-1-107-19076-4.

- ^ "Mak Phœun: Histoire du Cambodge de la fin du XVIe au début du XVIIIe siècle - At the time of the invasion one group of the royal family, the reigning king and two or more princes, escaped and eventually found refuge in Laos, while another group, the king's brother and his sons, were taken as hostages to Ayutthaya" (PDF). Michael Vickery’s Publications. Retrieved 1 July 2015.

- ^ "Mak Phœun: Histoire du Cambodge de la fin du XVIe au début du XVIIIe siècle – It was in fact at the end of the reign of Suriyobarm that the first step was taken in the form of a marriage between the crown prince Jayajetthâ and a Vietnamese princess at a date between 1616 and 1618" (PDF). Michael Vickery’s Publications. Retrieved 1 July 2015.

- ^ "Mak Phœun: Histoire du Cambodge de la fin du XVIe au début du XVIIIe siècle – It was in fact at the end of the reign of Suriyobarm that the first step was taken in the form of a marriage between the crown prince Jayajetthâ and a Vietnamese princess at a date between 1616 and 1618" (PDF). Michael Vickery’s Publications. Retrieved 1 July 2015.

- ^ "1620 A Cautionary Tale - Cambodia had quickly recovered from an Ayutthayan invasion of Lovek in 1593-94" (PDF). Michael Vickery’s Publications. Retrieved 26 June 2015.

- ^ "Preah Khan Reach - The Genealogy of Khmer Kings – The Rise of King Ang Chan – The Defeat of Sdach Kân" (PDF). Cambosastra. Retrieved 26 June 2015.

- ^ "History Period 1372-1432 60 Years Abandonment of Chaktomuk City". locomo.org. Retrieved 26 June 2015.

- ^ "Ben Kiernan Recovering History and Justice in Cambodia Within two years, Spanish and Portuguese conquistadores..." Yale University. Retrieved 26 June 2015.

- ^ Baker, Chris; Phongpaichit, Pasuk (11 May 2017). A History of Ayutthaya. Cambridge University Press. p. 116. ISBN 978-1-107-19076-4.

- ^ Baker, Chris; Phongpaichit, Pasuk (11 May 2017). A History of Ayutthaya. Cambridge University Press. p. 116. ISBN 978-1-107-19076-4.

- ^ Rungswasdisab, Puangthong (1995). War and Trade: Siamese Interventions in Cambodia, 1767-1851. University of Wollongong. pp. 42, 50.

- ^ "The Buddha of Chinese deception Oudong Mountain by Bou Saroeun". Phnom Penh Post. 22 June 2001. Retrieved 26 June 2015.

- ^ "The History of the Phnom Bakheng Monument" (PDF). Khmer Studies. Archived from the original (PDF) on 26 June 2015. Retrieved 26 June 2015.

- ^ Norman G. Owen (2005). The Emergence Of Modern Southeast Asia: A New History. University of Hawaii Press. pp. 117–. ISBN 978-0-8248-2890-5.

- ^ "The Project Gutenberg EBook of Travels in the Central Parts of Indo-China (Siam), Cambodia, and Laos (Vol. 1 of 2), by Henri Mouhot". The Project Gutenberg. Retrieved 3 July 2015.

- ^ Vickery, Michael. "'1620', A Cautionary Tale" (PDF). p. 5.

- ^ Kiernan, Ben (2008). Blood and Soil: Modern Genocide 1500–2000 By Ben Kiernan p. 102 The Vietnamese destruction of Champa 1390–1509. Melbourne Univ. ISBN 9780522854770. Retrieved 27 June 2015.

- ^ "The Cham: Descendants of Ancient Rulers of South China Sea Watch Maritime Dispute From Sidelines Written by Adam Bray". IOC-Champa. Archived from the original on 26 June 2015. Retrieved 26 June 2015.

- ^ Mote, Frederick W. (1998). The Cambridge History of China: Volume 8, The Ming Part 2 Parts 1368-1644 By Denis C. Twitchett, Frederick W. Mote. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521243339. Retrieved 26 June 2015.

- ^ Vachon, M., & Naren, K. (2006, April 29). A history of Champa. The Cambodia Daily. Retrieved September 10, 2020, from https://english.cambodiadaily.com/news/a-history-of-champa-87292/

- ^ Weber, N. (2012). The destruction and assimilation of Campā (1832-35) as seen from Cam sources. Journal of Southeast Asian Studies, 43(1), 158-180. Retrieved June 3, 2020, from www.jstor.org/stable/41490300

- ^ "Reconceptualizing Southern Vietnamese History from the 15th to 18th Centuries Competition along the Coasts from Guangdong to Cambodia by Brian A. Zottoli". University of Michigan. Retrieved 26 June 2015.

- ^ "Mak Phœun: Histoire du Cambodge de la fin du XVIe au début du XVIIIe siècle - According to Cambodian oral tradition, the marriage was because a weak Cambodian king fell in love..." (PDF). Michael Vickery’s Publications. Retrieved 30 June 2015.

- ^ Michael Arthur Aung-Thwin; Kenneth R. Hall (13 May 2011). New Perspectives on the History and Historiography of Southeast Asia: Continuing Explorations. Routledge. pp. 158–. ISBN 978-1-136-81964-3.

- ^ "Mak Phœun: Histoire du Cambodge de la fin du XVIe au début du XVIIIe siècle In: Bulletin de l'Ecole française d'Extrême-Orient. Tome 83, 1996. pp. 405-415" (PDF). Michael Vickery’s Publications. Retrieved 30 June 2015.

- ^ Vickery, Michael. "'1620', A Cautionary Tale" (PDF). p. 5.

- ^

- p. 157.

- Kiernan 2002, p. 253.

- Cormack 2001, p. 447.

- Reid 1999, p. 36.

- Chakrabartty 1988, p. 497.

- ^

- Fielding 2008, p. 27.

- Kiernan 2008,

- p. 158.

- Kiernan 2002, p. 254.

- ^ Osborne 2008, p. 45.

- ^ "War and trade: Siamese interventions in Cambodia 1767-1851 by Puangthong Rungswasdisab". University of Wollongong. Retrieved 27 June 2015.

- ^ Nolan, Cathal J. (2002). The Greenwood Encyclopedia of International Relations: S-Z by Cathal J. Nolan. Greenwood Pub. ISBN 9780313323836. Retrieved 21 November 2015.

- ^ "Volume IV - Age of Revolution and Empire 1750 to 1900 - French Indochina by Justin Corfield" (PDF). Grodno State Medical University. Retrieved 30 June 2015.

- ^ "Full text of "Siamese State Ceremonies" Chapter XV – The Oath of Allegiance 197...as compared with the early Khmer Oath..." Internet Archive. Retrieved 27 June 2015.

- ^ "March to the South (Nam Tiến)". Khmers Kampuchea-Krom Federation. Archived from the original on 26 June 2015. Retrieved 26 June 2015.

- ^ Chandler, David (2018) [1986]. A History of Cambodia. Taylor & Francis. pp. 140–144. ISBN 978-0-429-97514-1.

- ^ Corfield, Justin J. (2009). The History of Cambodia. ABC-CLIO. p. 18. ISBN 978-0-31335-723-7.

- ^ Chandler, David (2018) [1986]. A History of Cambodia. Taylor & Francis. pp. 146–149. ISBN 978-0-429-97514-1.

- ^ Chandler, David (2018) [1986]. A History of Cambodia. Taylor & Francis. pp. 150–156. ISBN 978-0-429-97514-1.

- ^ Chandler, David (2018) [1986]. A History of Cambodia. Taylor & Francis. pp. 157–160. ISBN 978-0-429-97514-1.

- ^ Corfield, Justin J. (2009). The History of Cambodia. ABC-CLIO. p. 19. ISBN 978-0-31335-723-7.

- ^ Chapuis, Oscar (1 January 2000). The Last Emperors of Vietnam: From Tu Duc to Bao Dai. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 48. ISBN 9780313311703. Retrieved 3 April 2015.

- ^ Dunmore, John (April 1993). "The French Voyages and the Philosophical Background". Tuatara. 32. Victoria University of Wellington Library. Retrieved 3 April 2015.

- ^ Keay, John (November 2005). "The Mekong Exploration Commission, 1866 – 68: Anglo-French Rivalry in South East Asia" (PDF). Asian Affairs. XXXVI (III). Routledge. Retrieved 3 April 2015.

- ^ Bussemaker, H.Th. (2001). "Paradise in Peril. Western colonial power and Japanese expansion in South-East Asia, 1905-1941". University of Amsterdam. Retrieved 3 April 2015.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Sovannarith Keo (14 December 2014). "The Raison d'être of French Protectorate of Cambodia". Retrieved 2 July 2020.

- ^ Buckley, Brendan M.; Anchukaitis, Kevin J.; Penny, Daniel; Fletcher, Roland; Cook, Edward R.; Sano, Masaki; Nam, Le Canh; Wichienkeeo, Aroonrut; Minh, Ton That; Hong, Truong Mai (13 April 2010). "Climate as a contributing factor in the demise of Angkor, Cambodia – Historians and archaeologists have, with a few notable exceptions (1, 2), only..." Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 107 (15). National Academy of Sciences: 6748–6752. doi:10.1073/pnas.0910827107. PMC 2872380. PMID 20351244.

- ^ Bourdonneau, Eric (September 2004). "Culturalism and historiography of ancient Cambodia: about prioritizing sources of Khmer history - Ranking Historical Sources and the Culturalist Approach in the Historiography of Ancient Cambodia by Eric Bourdonneau". Moussons. Recherche en Sciences Humaines Sur l'Asie du Sud-Est (7). Presses Universitaires de Provence: 39–70. doi:10.4000/moussons.2469. Retrieved 3 July 2015.

- ^ "Archaeology in Cambodia: An appraisal for future research by William A. Southworth, Archaeological consultant for the Center for Khmer Studies - Rather than being finalized and complete, the study of the archaeology of Cambodia..." Center for Khmer Studies. Retrieved 1 July 2015.

- ^ "From Funan to Angkor Collapse and Regeneration in Ancient Cambodia by Miriam T. Stark p. 166" (PDF). University of Hawaii. Archived from the original (PDF) on 23 September 2015. Retrieved 29 June 2015.

Further reading

[edit]- Chakrabartty, H. R. (1988). Vietnam, Kampuchea, Laos, Bound in Comradeship: A Panoramic Study of Indochina from Ancient to Modern Times, Volume 2. Patriot Publishers. ISBN 8170500486. Retrieved 16 February 2014.

- Cormack, Don (2001). Killing Fields, Living Fields: An Unfinished Portrait of the Cambodian Church - The Church That Would Not Die. Contributor Peter Lewis (reprint ed.). Kregel Publications. ISBN 0825460026. Retrieved 16 February 2014.

- Fielding, Leslie (2008). Before the Killing Fields: Witness to Cambodia and the Vietnam War (illustrated ed.). I.B.Tauris. ISBN 978-1845114930. Retrieved 16 February 2014.

- Kiernan, Ben (2008). Blood and Soil: A World History of Genocide and Extermination from Sparta to Darfur. Melbourne Univ. Publishing. ISBN 978-0522854770. Retrieved 16 February 2014.

- Kiernan, Ben (2002). The Pol Pot Regime: Race, Power, and Genocide in Cambodia Under the Khmer Rouge, 1975-79 (illustrated ed.). Yale University Press. ISBN 0300096496. Retrieved 16 February 2014.

- Osborne, Milton (2008). Phnom Penh: A Cultural History: A Cultural History. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0199711734. Retrieved 16 February 2014.

- Reid, Anthony (1999). Charting the shape of early modern Southeast Asia. Silkworm Books. ISBN 9747551063. Retrieved 16 February 2014.

External links

[edit]- The Ram Khamhaeng Inscription - The fake that did not come true

- What the collapse of ancient capitals can teach us about the cities of today

- Center for Southeast Asian Studies Japan

- Center for Khmer Studies

- The Philippine islands, 1493-1803 at the Internet Archive

- Strange Parallels - Southeast Asia in a Global Context by Victor Lieberman

- Maritime boundary delimitation in the gulf of Thailand - information on multiple unsolved regional border disputes,dating back to the dark ages

.svg/250px-Flag_of_Cambodia_(pre-1863).svg.png)

.svg/2000px-Flag_of_Cambodia_(pre-1863).svg.png)