Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Prince Marko

View on Wikipedia

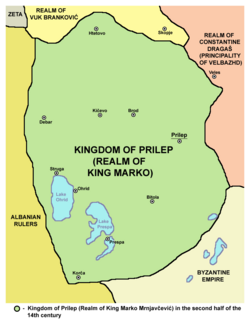

Marko Mrnjavčević (Serbian Cyrillic: Марко Мрњавчевић, pronounced [mâːrko mr̩̂ɲaːʋt͡ʃeʋit͡ɕ] ⓘ; c. 1335 – 17 May 1395) was the de jure Serbian king from 1371 to 1395, while he was the de facto ruler of territory in western Macedonia centered on the town of Prilep. He is known as Prince Marko (Macedonian: Kрaле Марко; Serbian Cyrillic: Краљевић Марко, Kraljević Marko, IPA: [krǎːʎeʋit͡ɕ mâːrko]) and King Marko (Macedonian: Kрaл Марко; Serbian Cyrillic: Краљ Марко; Bulgarian: Крали Марко) in South Slavic oral tradition, in which he has become a major character during the period of Ottoman rule over the Balkans. Marko's father, King Vukašin, was co-ruler with Serbian Tsar Stefan Uroš V, whose reign was characterised by weakening central authority and the gradual disintegration of the Serbian Empire. Vukašin's holdings included lands in north-western Macedonia and Kosovo. In 1370 or 1371, he crowned Marko "young king"; this title included the possibility that Marko would succeed the childless Uroš on the Serbian throne.

Key Information

On 26 September 1371, Vukašin was killed and his forces defeated in the Battle of Maritsa. About two months later, Tsar Uroš died. This formally made Marko the king of the Serbian land; however, Serbian noblemen, who had become effectively independent from the central authority, did not even consider to recognise him as their supreme ruler. Sometime after 1371, he became an Ottoman vassal; by 1377, significant portions of the territory he inherited from Vukašin were seized by other noblemen. King Marko, in reality, came to be a regional lord who ruled over a relatively small territory in western Macedonia. He funded the construction of the Monastery of Saint Demetrius near Skopje (better known as Marko's Monastery), which was completed in 1376. Later, Marko became an Ottoman vassal and died on 17 May 1395, fighting against the Wallachians in the Battle of Rovine.

Although a ruler of modest historical significance, Marko became a major character in South Slavic oral tradition. He is venerated as a national hero by the Serbs, Macedonians and Bulgarians, remembered in Balkan folklore as a fearless and powerful protector of the weak, who fought against injustice and confronted the Turks during the Ottoman occupation.

Life

[edit]Until 1371

[edit]Marko was born about 1335 as the first son of Vukašin Mrnjavčević and his wife Alena.[1] The patronymic "Mrnjavčević" derives from Mrnjava, described by 17th-century Ragusan historian Mavro Orbin as a minor nobleman from Zachlumia (in present-day Herzegovina and southern Dalmatia).[2] According to Orbin, Mrnjava's sons were born in Livno in western Bosnia,[2] where he may have moved after Zachlumia was annexed from Serbia by Bosnia in 1326.[3] The Mrnjavčević familyn.b.1 may have later supported Serbian Emperor (tsar) Stefan Dušan in his preparations to invade Bosnia as did other Zachlumian nobles, and, fearing punishment, emigrated to the Serbian Empire before the war started.[3][4] These preparations possibly began two years ahead of the invasion,[4] which took place in 1350. From that year comes the earliest written reference to Marko's father Vukašin, describing him as Dušan's appointed župan (district governor) of Prilep,[3][5] which was acquired by Serbia from Byzantium in 1334 with other parts of Macedonia.[6] In 1355, at about age 47, Stefan Dušan died suddenly of a stroke.[7]

Dušan was succeeded by his 19-year-old son Uroš, who apparently regarded Marko Mrnjavčević as a man of trust. The new Emperor appointed him the head of the embassy he sent to Ragusa (now Dubrovnik, Croatia) at the end of July 1361 to negotiate peace between the empire and the Ragusan Republic after hostilities earlier that year. Although peace was not reached, Marko successfully negotiated the release of Serbian merchants from Prizren who were detained by the Ragusans and was permitted to withdraw silver deposited in the city by his family. The account of that embassy in a Ragusan document contains the earliest-known, undisputed reference to Marko Mrnjavčević.[8] An inscription written in 1356 on a wall of a church in the Macedonian region of Tikveš, mentions a Nikola and a Marko as governors in that region, but the identity of this Marko is disputed.[9]

Dušan's death was followed by the stirring of separatist activity in the Serbian Empire. The south-western territories, including Epirus, Thessaly, and lands in southern Albania, seceded by 1357.[10] However, the core of the state (the western lands, including Zeta and Travunia with the upper Drina Valley; the central Serbian lands; and Macedonia), remained loyal to Emperor Uroš.[11] Nevertheless, local noblemen asserted more and more independence from Uroš' authority even in the part of the state that remained Serbian. Uroš was weak and unable to counteract these separatist tendencies, becoming an inferior power in his own domain.[12] Serbian lords also fought each other for territory and influence.[13]

Vukašin Mrnjavčević was a skilful politician, and gradually assumed the main role in the empire.[14] In August or September 1365 Uroš crowned him king, making him his co-ruler. By 1370, Marko's potential patrimony increased as Vukašin expanded his personal holdings from Prilep further into Macedonia, Kosovo and Metohija, acquiring Prizren, Pristina, Novo Brdo, Skopje and Ohrid.[3] In a charter he issued on 5 April 1370, Vukašin mentioned his wife (Queen Alena) and sons (Marko and Andrijaš), signing himself as "Lord of the Serb and Greek Lands, and of the Western Provinces" (господинь зємли срьбьскои и грькѡмь и западнимь странамь).[15] In late 1370 or early 1371, Vukašin crowned Marko "Young King",[16][17] a title given to heirs presumptive of Serbian kings to secure their position as successors to the throne. Since Uroš was childless, Marko could thus become his successor, beginning a new—Vukašin—dynasty of Serbian sovereigns,[3] and ending the two-century Nemanjić dynasty. Most Serbian lords were unhappy with the situation, which strengthened their desire for independence from the central authority.[17]

Vukašin sought a well-connected spouse for Marko. A princess from the Croatian House of Šubić of Dalmatia was sent by her father, Grgur, to the court of their relative Tvrtko I, the ban of Bosnia. She was supposed to be raised and married by Tvrtko's mother Jelena. Jelena was the daughter of George II Šubić, whose maternal grandfather was Serbian King Dragutin Nemanjić.[18] The ban and his mother approved of Vukašin's idea to join the Šubić princess and Marko, and the wedding was imminent.[19][20] However, in April 1370 Pope Urban V sent Tvrtko a letter forbidding him to give the Catholic lady in marriage to the "son of His Magnificence, the King of Serbia, a schismatic" (filio magnifici viri Regis Rascie scismatico).[20] The pope also notified King Louis I of Hungary, nominal overlord of the ban,[21] of the impending "offence to the Christian faith", and the marriage did not occur.[19] Marko subsequently married Jelena (daughter of Radoslav Hlapen, the lord of Veria and Edessa and the major Serbian nobleman in southern Macedonia).[22]

During the spring of 1371, Marko participated in the preparations for a campaign against Nikola Altomanović, the major lord in the west of the Empire.[23] The campaign was planned jointly by King Vukašin and Đurađ I Balšić, lord of Zeta (who was married to Olivera, the king's daughter). In July of that year Vukašin and Marko camped with their army outside Scutari, on Balšić's territory, ready to make an incursion towards Onogošt in Altomanović's land. The attack never took place, since the Ottomans threatened the land of Despot Jovan Uglješa (lord of Serres and Vukašin's younger brother, who ruled in eastern Macedonia) and the Mrnjavčević forces were quickly directed eastward.[23] Having sought allies in vain, the two brothers and their troops entered Ottoman-controlled territory. At the Battle of Maritsa on 26 September 1371, the Turks annihilated the Serbian army;[24] the bodies of Vukašin and Jovan Uglješa were never found. The battle site, near the village of Ormenio in present-day eastern Greece, has ever since been called as Sırp Sındığı ("Serbian rout") in Turkish. The Battle of Maritsa had far-reaching consequences for the region, since it opened the Balkans to the Turks.[25]

After 1371

[edit]

When his father died, "young king" Marko became king and co-ruler with Emperor Uroš. The Nemanjić dynasty ended soon afterwards, when Uroš died on 2 (or 4) December 1371 and Marko became the formal sovereign of Serbia.[26] Serbian lords, however, did not recognise him,[26] and divisions within the state increased.[25] After the two brothers' deaths and the destruction of their armies, the Mrnjavčević family was left powerless.[26] Lords around Marko exploited the opportunity to seize significant parts of his patrimony. By 1372, Đurađ I Balšić took Prizren and Peć, and Prince Lazar Hrebeljanović took Pristina.[27] By 1377, Vuk Branković acquired Skopje, and Albanian magnate Andrea Gropa became virtually independent in Ohrid; however, he may have remained a vassal to Marko as he had been to Vukašin.[25] Gropa's son-in-law was Marko's relative, Ostoja Rajaković of the clan of Ugarčić from Travunia. He was one of Serbian noblemen from Zachlumia and Travunia (adjacent principalities in present-day Herzegovina) who received lands in the newly conquered parts of Macedonia during Emperor Dušan's reign.[28] The only sizable town kept by Marko was Prilep, from which his father rose. King Marko became a petty prince ruling a relatively small territory in western Macedonia, bordered in the north by the Šar mountains and Skopje; in the east by the Vardar and the Crna Reka rivers, and in the west by Ohrid. The southern limits of his territory are uncertain.[22] Marko shared his rule with his younger brother, Andrijaš, who had his own land.[25] Their mother, Queen Alena, became a nun after Vukašin's death, taking the monastic name Jelisaveta, but was co-ruler with Andrijaš for some time after 1371. The youngest brother, Dmitar, lived on land controlled by Andrijaš. There was another brother, Ivaniš, about whom little is known.[29] When Marko became an Ottoman vassal is uncertain, but it was probably not immediately after the Battle of Maritsa.[30]

At some point, Marko separated from Jelena and lived with Todora, the wife of a man named Grgur, and Jelena returned to her father in Veria. Marko later sought to reconcile with Jelena but he had to send Todora to his father-in-law. Since Marko's land was bordered on the south by Hlapen's, the reconciliation may have been political.[22] Scribe Dobre, a subject of Marko's, transcribed a liturgical book for the church in the village of Kaluđerec,n.b.2 and when he finished, he composed an inscription which begins as follows:[31]

|

Слава сьвршитєлю богѹ вь вѣкы, аминь, а҃мнь, а҃м. Пыса сє сиꙗ книга ѹ Порѣчи, ѹ сєлѣ зовомь Калѹгєрєць, вь дьны благовѣрнаго кралꙗ Марка, ѥгда ѿдадє Ѳодору Грьгѹровѹ жєнѹ Хлапєнѹ, а ѹзє жєнѹ свою прьвовѣнчанѹ Ѥлєнѹ, Хлапєновѹ дьщєрє. |

|

Marko's fortress was on a hill north of present-day Prilep; its partially preserved remains are known as Markovi Kuli ("Marko's towers"). Beneath the fortress is the village of Varoš, site of the medieval Prilep. The village contains the Monastery of Archangel Michael, renovated by Marko and Vukašin, whose portraits are on the walls of the monastery's church.[22] Marko was ktetor of the Church of Saint Sunday in Prizren, which was finished in 1371, shortly before the Battle of Maritsa. In the inscription above the church's entrance, he is called "young king".[32]

The Monastery of St. Demetrius, popularly known as Marko's Monastery, is in the village of Markova Sušica (near Skopje) and was built from c. 1345 to 1376 (or 1377). Kings Marko and Vukašin, its ktetors, are depicted over the south entrance of the monastery church.[1] Marko is an austere-looking man in purple clothes, wearing a crown decorated with pearls. With his left hand he holds a scroll, whose text begins: "I, in the Christ God the pious King Marko, built and inscribed this divine temple ..." In his right hand, he holds a horn symbolizing the horn of oil with which the Old Testament kings were anointed at their coronation (as described in 1 Samuel 16:13). Marko is said to be shown here as the king chosen by God to lead his people through the crisis following the Battle of Maritsa.[26]

Marko minted his own money, in common with his father and other Serbian nobles of the time.[33] His silver coins weighed 1.11 grams,[34] and were produced in three types. In two of them, the obverse contained a five-line text: ВЬХА/БАБЛГОВ/ѢРНИКР/АЛЬМА/РКО ("In the Christ God, the pious King Marko").[35] In the first type, the reverse depicted Christ seated on a throne; in the second, Christ was seated on a mandorla. In the third type, the reverse depicted Christ on a mandorla; the obverse contained the four-line text БЛГО/ВѢРНИ/КРАЛЬ/МАРКО ("Pious King Marko"),[35] which Marko also used in the church inscription. He omitted a territorial designation from his title, probably in tacit acknowledgement of his limited power.[22] Although his brother Andrijaš also minted his own coins, the money supply in the territory ruled by the Mrnjavčević brothers primarily consisted of coins struck by King Vukašin and Tsar Uroš.[36] About 150 of Marko's coins survive in numismatic collections.[35]

By 1379, Prince Lazar Hrebeljanović, the ruler of Moravian Serbia, emerged as the most-powerful Serbian nobleman.[30][37] Although he called himself Autokrator of all the Serbs (самодрьжць вьсѣмь Србьлѥмь), he was not strong enough to unite all Serbian lands under his authority. The Balšić and Mrnjavčević families, Konstantin Dragaš (maternally a Nemanjić), Vuk Branković and Radoslav Hlapen continued ruling their respective regions.[30] In addition to Marko, Tvrtko I was crowned King of the Serbs and of Bosnia in 1377. Maternally related to the Nemanjić dynasty, Tvrtko had seized western portions of the former Serbian Empire in 1373.[38]

On 15 June 1389, Serbian forces led by Prince Lazar, Vuk Branković, and Tvrtko's nobleman Vlatko Vuković of Zachlumia, confronted the Ottoman army led by Sultan Murad I at the Battle of Kosovo, the best-known battle in medieval Serbian history.[39] With the bulk of both armies wiped out and Lazar and Murad killed, the outcome of the battle was inconclusive. In its aftermath the Serbs had insufficient manpower to defend their lands, while the Ottomans had many more troops in the east. Serbian principalities which were not already Ottoman vassals became such over the next few years.[39]

In 1394, a group of Ottoman vassals in the Balkans renounced their vassalage.[40] Although Marko was not among them, his younger brothers Andrijaš and Dmitar refused to remain under Ottoman dominance. They emigrated to the Kingdom of Hungary, entering the service of King Sigismund. They travelled via Ragusa, where they withdrew two-thirds of their late father's store of 96.73 kilograms (213.3 lb) of silver, leaving the remaining third for Marko. Although Andrijaš and Dmitar were the first Serbian nobles to emigrate to Hungary, the Serbian northward migration would continue throughout the Ottoman occupation.[40]

In 1395, the Ottomans attacked Wallachia to punish its ruler, Mircea I, for his incursions into their territory.[41] Three Serbian vassals fought on the Ottoman side: King Marko, Lord Konstantin Dragaš, and Despot Stefan Lazarević (son and heir of Prince Lazar). The Battle of Rovine, on 17 May 1395, was won by the Wallachians; Marko and Dragaš were killed.[42] After their deaths the Ottomans annexed their lands, combining them into an Ottoman province centred in Kyustendil.[41] Thirty-six years after the Battle of Rovine, Konstantin the Philosopher wrote the Biography of Despot Stefan Lazarević and recorded what Marko said to Dragaš on the eve of the battle: "I say and pray to the lord to help the Christians and for me to be among the first to die in this war."[43] The chronicle goes on to state that Marko and Dragaš were killed in the battle.[44] Another medieval source that mentions Marko's death at the Battle of Rovine is the Dečani Chronicle.[44]

In folk poetry

[edit]Serbian epic poetry

[edit]Marko Mrnjavčević is the most popular hero of Serbian epic poetry,[45] in which he is called "Kraljević Marko" (with the word kraljević meaning "prince"[45] or "king's son"). This informal title was attached to King Vukašin's sons in contemporary sources as a surname (Marko Kraljević),n.b.3 and it was adopted by the Serbian oral tradition as part of Marko's name.[46]

Poems about Kraljević Marko do not follow a storyline; what binds them into a poetic cycle is the hero himself,[47] with his adventures illuminating his character and personality.[48] The epic Marko had a 300-year lifespan; 14th- to 16th-century heroes appearing as his companions[47] include Miloš Obilić, Relja Krilatica, Vuk the Fiery Dragon and Sibinjanin Janko and his nephew, Banović Sekula.[49] Very few historical facts about Marko can be found in the poems, but they reflect his connection with the disintegration of the Serbian Empire and his vassalage to the Ottomans.[47] They were composed by anonymous Serbian poets during the Ottoman occupation of their land. According to American Slavicist George Rapall Noyes, they "combine tragic pathos with almost ribald comedy in a fashion worthy of an Elizabethan playwright."[45]

Serbian epic poetry agrees that King Vukašin was Marko's father. His mother in the poems was Jevrosima, sister of voivode Momčilo, the lord of the Pirlitor Fortress (on Mount Durmitor in Old Herzegovina). Momčilo is described as a man of immense size and strength with magical attributes: a winged horse and a sabre with eyes. Vukašin murdered him with the help of the voivode's young wife, Vidosava, despite Jevrosima's self-sacrificing attempt to save her brother. Instead of marrying Vidosava (the original plan), Vukašin killed the treacherous woman. He took Jevrosima from Pirlitor to his capital city, Skadar, and married her according to the advice of the dying Momčilo. They had two sons, Marko and Andrijaš, and the poem recounting these events says that Marko took after his uncle Momčilo.[50] This epic character corresponds historically with Bulgarian brigand and mercenary Momchil, who was in the service of Serbian Tsar Dušan; he later became a despot and died in the 1345 Battle of Peritheorion.[51] According to another account, Marko and Andrijaš were mothered by a vila (Slavic mountain nymph) married by Vukašin after he caught her near a lake and removed her wings so she could not escape.[52]

As Marko matured, he became headstrong; Vukašin once said that he had no control over his son, who went wherever he wanted, drank and brawled. Marko grew up into a large, strong man, with a terrifying appearance, which was also somewhat comical. He wore a wolf-skin cap pulled low over his dark eyes, his black moustache was the size of a six-month-old lamb and his cloak was a shaggy wolf-pelt. A Damascus sabre swung at his waist, and a spear was slung across his back. Marko's pernach weighed 66 okas (85 kilograms (187 lb)) and hung on the left side of his saddle, balanced by a well-filled wineskin on the saddle's right side. His grip was strong enough to squeeze drops of water from a piece of dry cornel wood. Marko defeated a succession of champions against overwhelming odds.[47][48]

The hero's inseparable companion was his powerful, talking piebald horse Šarac; Marko always gave him an equal share of his wine.[48] The horse could leap three spear-lengths high and four spear-lengths forward, enabling Marko to capture the dangerous, elusive vila Ravijojla. She became his blood sister, promising to help him in dire straits. When Ravijojla helped him kill the monstrous, three-hearted Musa Kesedžija (who almost defeated him), Marko grieved because he had slain a better man than himself.[53][54]

Marko is portrayed as a protector of the weak and helpless, a fighter against Turkish bullies and injustice in general. He was an idealised keeper of patriarchal and natural norms: in a Turkish military camp, he beheaded the Turk who dishonourably killed his father. He abolished the marriage tax by killing the tyrant who imposed it on the people of Kosovo. He saved the sultan's daughter from an unwanted marriage after she entreated him, as her blood brother, to help her. He rescued three Serbian voivodes (his blood brothers) from a dungeon and helped animals in distress. Marko was a rescuer and benefactor of people, and a promoter of life; "Prince Marko is remembered like a fair day in the year".[47]

Characteristic of Marko was his reverence and love for his mother, Jevrosima; he often sought her advice, following it even when it contradicted his own desires. She lived with Marko at his mansion in Prilep, his lodestar guiding him away from evil and toward good on the path of moral improvement and Christian virtues.[55] Marko's honesty and moral courage are noteworthy in a poem in which he was the only person who knew the will of the late Tsar Dušan regarding his heir. Marko refused to lie in favour of the pretenders—his father and uncles. He said truthfully that Dušan appointed his son, Uroš, heir to the Serbian throne. This almost cost him his life, since Vukašin tried to kill him.[48]

Marko is represented as a loyal vassal of the Ottoman sultan, fighting to protect the potentate and his empire from outlaws. When summoned by the sultan, he participated in Turkish military campaigns.[47] Even in this relationship, however, Marko's personality and sense of dignity were apparent. He occasionally made the sultan uneasy,[48] and meetings between them usually ended like this:

|

Цар с' одмиче, а Марко примиче, |

Marko's fealty was combined with the notion that the servant was greater than his lord, as Serbian poets turned the tables on their conquerors. This dual aspect of Marko may explain his heroic status; for the Serbs he was "the proud symbol expressive of the unbroken spirit that lived on in spite of disaster and defeat,"[48] according to translator of Serbian epic poems David Halyburton Low.

In battle, Marko used not only his strength and prowess but cunning and trickery. Despite his extraordinary qualities he was not depicted as a superhero or a god, but as a mortal man. There were opponents who surpassed him in courage and strength. He was occasionally capricious, short-tempered or cruel, but his predominant traits were honesty, loyalty and fundamental goodness.[48]

With his comic appearance and behaviour, and his remarks at his opponents' expense, Marko is the most humorous character in Serbian epic poetry.[47] When a Moor struck him with a mace, Marko said laughingly, "O valiant black Moor! Are you jesting or smiting in earnest?"[58] Jevrosima once advised her son to cease his bloody adventures and plough the fields instead. He obeyed in a grimly humorous way,[48] ploughing the sultan's highway instead of the fields. A group of Turkish Janissaries with three packs of gold shouted at him to stop ploughing the highway. He warned them to keep off the furrows, but quickly wearied of arguing:

|

Диже Марко рало и волове, |

|

Marko, age 300, rode the 160-year-old Šarac by the seashore towards Mount Urvina when a vila told him that he was going to die. Marko then leaned over a well and saw no reflection of his face on the water; hydromancy confirmed the vila's words. He killed Šarac so the Turks would not use him for menial labor, and gave his beloved companion an elaborate burial. Marko broke his sword and spear, throwing his mace far out to sea before lying down to die. His body was found seven days later by Abbot Vaso and his deacon, Isaija. Vaso took Marko to Mount Athos and buried him at the Hilandar Monastery in an unmarked grave.[61]

Epic poetry of Bulgaria and North Macedonia

[edit]"Krali Marko" has been one of the most popular characters in Bulgarian (more generally Eastern South Slavic) folklore for centuries.[62] These epic tales of Marko seem to originate from the present-day North Macedonia,[63] therefore also being an important part of the ethnic heritage of Macedonians.

According to local legend Marko's mother was Evrosiya (Евросия), sister of the Bulgarian voivoda Momchil (who ruled territory in the Rhodope Mountains). At Marko's birth three narecnitsi (fairy sorceresses) appeared, predicting that he would be a hero and replace his father (King Vukašin). When the king heard this, he threw his son into the river in a basket to get rid of him. A samodiva named Vila found Marko and brought him up, becoming his foster mother. Because Marko drank the samodiva's milk, he acquired supernatural powers and became a Bulgarian freedom fighter against the Turks. He has a winged horse named Sharkolia ("dappled") and a stepsister, the samodiva Gyura. Bulgarian legends incorporate fragments of pagan mythology and beliefs, although the Marko epic was created as late as the 14–18th centuries. Among Bulgarian epic songs, songs about Krali Marko are common and pivotal.[64][65] Bulgarian folklorists who collected stories about Marko included educator Trayko Kitanchev (in the Resen region of western Macedonia) and Marko Cepenkov of Prilep (throughout the region).[66]

In legend

[edit]South Slavic legends about Kraljević Marko or Krali Marko are primarily based on myths much older than the historical Marko Mrnjavčević. He differs in legend from the folk poems; in some areas he was imagined as a giant who walked stepping on hilltops, his head touching the clouds. He was said to have helped God shape the earth, and created the river gorge in Demir Kapija ("Iron Gate") with a stroke of his sabre. This drained the sea covering the regions of Bitola, Mariovo and Tikveš in Macedonia, making them habitable. After the earth was shaped, Marko arrogantly showed off his strength. God took it away by leaving a bag as heavy as the earth on a road; when Marko tried to lift it, he lost his strength and became an ordinary man.[67]

Legend also has it that Marko acquired his strength after he was suckled by a vila. King Vukašin threw him into a river because he did not resemble him, but the boy was saved by a cowherd (who adopted him, and a vila suckled him). In other accounts, Marko was a shepherd (or cowherd) who found a vila's children lost in a mountain and shaded them against the sun (or gave them water). As a reward the vila suckled him three times, and he could lift and throw a large boulder. An Istrian version has Marko making a shade for two snakes, instead of the children. In a Bulgarian version, each of the three draughts of milk he suckled from the vila's breast became a snake.[67]

Marko was associated with large, solitary boulders and indentations in rocks; the boulders were said to be thrown by him from a hill, and the indentations were his footprints (or the hoofprints of his horse).[67] He was also connected with geographic features such as hills, glens, cliffs, caves, rivers, brooks and groves, which he created or at which he did something memorable. They were often named after him, and there are many toponyms—from Istria in the west to Bulgaria in the east—derived from his name.[68] In Bulgarian and Macedonian stories, Marko had an equally strong sister who competed with him in throwing boulders.[67]

In some legends, Marko's wonder horse was a gift from a vila. A Serbian story says that he was looking for a horse who could bear him. To test a steed, he would grab him by the tail and sling him over his shoulder. Seeing a diseased piebald foal owned by some carters, Marko grabbed him by the tail but could not move him. He bought (and cured) the foal, naming him Šarac. He became an enormously powerful horse and Marko's inseparable companion.[69] Macedonian legend has it that Marko, following a vila's advice, captured a sick horse on a mountain and cured him. Crusted patches on the horse's skin grew white hairs, and he became a piebald.[67]

According to folk tradition Marko never died; he lives on in a cave, in a moss-covered den or in an unknown land.[67] A Serbian legend recounts that Marko once fought a battle in which so many men were killed that the soldiers (and their horses) swam in blood. He lifted his hands towards heaven and said, "Oh God, what am I going to do now?" God took pity on Marko, transporting him and Šarac to a cave (where Marko stuck his sabre into a rock and fell asleep). There is moss in the cave; Šarac eats it bit by bit, while the sabre slowly emerges from the rock. When it falls on the ground and Šarac finishes the moss, Marko will awaken and reenter the world.[69] Some allegedly saw him after descending into a deep pit, where he lived in a large house in front of which Šarac was seen. Others saw him in a faraway land, living in a cave. According to Macedonian tradition Marko drank "eagle's water", which made him immortal; he is with Elijah in heaven.[67]

In modern culture

[edit]

During the 19th century, Marko was the subject of several dramatizations. In 1831 the Hungarian drama Prince Marko, possibly written by István Balog,[70] was performed in Buda and in 1838, the Hungarian drama Prince Marko – Great Serbian Hero by Celesztin Pergő was staged in Arad.[70] In 1848 Jovan Sterija Popović wrote the tragedy The Dream of Prince Marko, in which the legend of sleeping Marko is its central motif. Petar Preradović wrote the drama Kraljević Marko, which glorifies southern Slav strength. In 1863 Francesco Dall'Ongaro presented his Italian drama, The Resurrection of Prince Marko.[70] In her collection of short stories from 1978, Nouvelles Orientales, Marguerite Yourcenar imagined an alternative, inexplicable end to Marko's life (La Fin de Marko kraliévitch).

Of all Serbian epic or historical figures, Marko is considered to have given the most inspiration to visual artists;[71] a monograph on the subject lists 87 authors.[72] His oldest known depictions are 14th-century frescoes from Marko's Monastery and Prilep.[73][74] An 18th-century drawing of Marko is found in the Čajniče Gospels, a medieval parchment manuscript belonging to a Serbian Orthodox church in Čajniče in eastern Bosnia. The drawing is simple, unique in depicting Marko as a saint[75] and reminiscent of stećci reliefs.[76] Vuk Karadžić wrote that during his late-18th-century childhood he saw a painting of Marko carrying an ox on his back.[69]

Nineteenth-century lithographs of Marko were made by Anastas Jovanović,[77] Ferdo Kikerec[76] and others. Artists who painted Marko during that century include Mina Karadžić,[77] Novak Radonić[78] and Đura Jakšić.[78] Twentieth-century artists include Nadežda Petrović,[79] Mirko Rački,[80] Uroš Predić[81] and Paja Jovanović.[81] A sculpture of Marko on Šarac by Ivan Meštrović was reproduced on a Yugoslavian banknote and stamp.[82] Modern illustrators with Marko as their subject include Alexander Key, Aleksandar Klas, Zuko Džumhur, Vasa Pomorišac and Bane Kerac.[72]

Princ Marko, and his Sabre was also inspiration for Current Serbian National Anthem "Boze Pravde". The song was taken from a theatre piece Markova Sablja, very popular among Serbs in 1872.

Motifs in multiple works are Marko and Ravijojla, Marko and his mother, Marko and Šarac, Marko shooting an arrow, Marko plowing the roads, the fight between Marko and Musa and Marko's death.[83] Also, several artists have tried to produce a realistic portrait of Marko based on his frescoes.[73] In 1924 Prilep Brewery introduced a light beer, Krali Marko.[84]

See also

[edit]Footnotes

[edit]^n.b.1 The family name "Mrnjavčević" was not mentioned in contemporary sources, nor was any other surname associated with this family. The oldest known source mentioning the name "Mrnjavčević" is Ruvarčev rodoslov "The Genealogy of Ruvarac", written between 1563 and 1584. It is unknown whether it was introduced into the Genealogy from some older source, or from the folk poetry and tradition.[85]

^n.b.2 This liturgical book, acquired in the 19th century by Russian collector Aleksey Khludov, is kept today in the State Historical Museum of Russia.

^n.b.3 The name Despotović ("despot's son") was applied in a similar way to Uglješa, the son of Despot Jovan Uglješa, King Vukašin's younger brother.[46]

Notes

[edit]- ^ a b Fostikov 2002, pp.49–50.

- ^ a b Орбин 1968, p. 116.

- ^ a b c d e Fine 1994, pp.362–3.

- ^ a b Fine 1994, p.323.

- ^ Stojanović 1902, p.37.

- ^ Fine 1994, p.288.

- ^ Fine 1994, p.335.

- ^ Mihaljčić 1975, p.51. Ćorović 2001, "Распад Српске Царевине".

- ^ Mihaljčić 1975, p.77.

- ^ Šuica 2000, p.15.

- ^ Fine 1994, p. 358

- ^ Fine 1994, p. 345.

- ^ Šuica 2000, p. 19

- ^ Mihaljčić 1975, p.83.

- ^ Miklošič 1858, p.180, № CLXVII.

- ^ Sedlar 1994, pp. 31.

- ^ a b Šuica 2000, p. 20

- ^ Fajfrić (2000), "Први Котроманићи".

- ^ a b Jireček 1911, p.430.

- ^ a b Theiner 1860, p.97, № CXC.

- ^ Theiner 1860, p.97, № CLXXXIX.

- ^ a b c d e Mihaljčić 1975, pp. 170–1

- ^ a b Mihaljčić 1975, p. 137; Fine 1994, p. 377

- ^ Ćorović 2001, "Маричка погибија".

- ^ a b c d Fine 1994, pp. 379–82

- ^ a b c d Mihaljčić 1975, p.168.

- ^ Šuica 2000, pp.35–6.

- ^ Šuica 2000, p.42.

- ^ Fostikov 2002, p.51.

- ^ a b c Mihaljčić 1975, pp.164–5.

- ^ Stojanović 1902, pp.58–9

- ^ Mihaljčić 1975, p.166.

- ^ Mihaljčić 1975, p.181.

- ^ Šuica 2000, pp.133–6.

- ^ a b c Mandić 2003, pp.24–5.

- ^ Mihaljčić 1975, p.183.

- ^ Mihaljčić 1975, p.220.

- ^ Fine 1994, p.393.

- ^ a b Fine 1994, pp.408–11.

- ^ a b Fostikov 2002, pp.52–3.

- ^ a b Fine 1994, p.424.

- ^ Ostrogorsky 1956, pp. 489.

- ^ Konstantin 2000, "О погибији краља Марка и Константина Драгаша".

- ^ a b Ђурић, Иван (1984). Сумрак Византије: време Јована VIII Палеолога (1392–1448). Народна књига. p. 78.

У Дечанском летопису је, уз вест о боју на Ровинама, забележено како су тамо погинули Марко Краљевић и Константин Драгаш.

- ^ a b c Noyes 1913, "Introduction".

- ^ a b Rudić 2001, p.89.

- ^ a b c d e f g Deretić 2000, "Епска повесница српског народа".

- ^ a b c d e f g h Low 1922, "The Marko of the Ballads".

- ^ Popović 1988, pp.24–8.

- ^ Low 1922, "The Marriage of King Vukašin".

- ^ Ćorović 2001, "Стварање српског царства".

- ^ Bogišić 1878, pp. 231–2.

- ^ Low 1922, "Marko Kraljević and the Vila"

- ^ Low 1922, "Marko Kraljević and Musa Kesedžija"

- ^ Popović 1988, pp.70–7.

- ^ Karadžić 2000, "Марко Краљевић познаје очину сабљу".

- ^ Low 1922, p.73.

- ^ Karadžić 2000, "Марко Краљевић укида свадбарину".

- ^ Karadžić 2000, "Орање Марка Краљевића".

- ^ Low 1922, "Marko's Ploughing".

- ^ Low 1922, "The Death of Marko Kraljević".

- ^ For further information, read Veliko Iordanov (1901). Krali-Marko v bulgarskata narodna epika. Sofia: Sbornik na Bulgarskoto Knizhovno Druzhestvo.

- ^ Mihail Arnaudov (1961). "Българско народно творчество в 12 тома. Том 1. Юнашки песни" (in Bulgarian). Archived from the original on October 15, 2007.

- ^ The River Danube in Balkan Slavic Folksongs, Ethnologia Balkanica (01/1997), Burkhart, Dagmar; Issue: 01/1997, pp. 53–60

- ^ A History of Macedonian Literature 865–1944, Volume 112 of Slavistic Printings and Reprintings, Charles A. Moser, Publisher Mouton, 1972.

- ^ Прилеп; зап. Марко Цепенков (СбНУ 2, с. 116–120, № 2 – "Марко грабит Ангелина").

- ^ a b c d e f g Radenković 2001, pp.293–7.

- ^ Popović 1988, pp.41–2.

- ^ a b c Karadžić 1852, pp.345–6, s.v. "Марко Краљевић".

- ^ a b c Šarenac 1996, p. 26

- ^ Šarenac 1996, p. 06

- ^ a b Šarenac 1996, p. 02

- ^ a b Šarenac 1996, p. 05

- ^ "Serbian Medieval Royal Attire". 2006-11-21. Archived from the original on 2011-09-29. Retrieved 2011-06-27.

- ^ Momirović 1956, p. 176

- ^ a b Šarenac 1996, p. 27

- ^ a b Šarenac 1996, p. 44

- ^ a b Šarenac 1996, p. 45

- ^ Šarenac 1996, p. 28

- ^ Šarenac 1996, p. 24

- ^ a b Šarenac 1996, p. 46

- ^ Šarenac 1996, p. 33

- ^ Šarenac 1996, p. 6–14

- ^ "Krali Marko". Prilep Brewery. Archived from the original on 2011-06-15. Retrieved 2011-06-28.

- ^ Rudić 2001, p.96.

References

[edit]- Bogišić, Valtazar (1878). Народне пјесме: из старијих, највише приморских записа [Folk poems: from older records, mostly from the Littoral] (in Serbian). 1. The Internet Archive.

- Ćirković, Sima (2004). The Serbs. Malden: Blackwell Publishing. ISBN 978-1-4051-4291-5.

- Ćorović, Vladimir (November 2001). Историја српског народа [History of the Serbian People] (in Serbian). Project Rastko.

- Deretić, Jovan (2000). Кратка историја српске књижевности [Short history of Serbian literature] (in Serbian). Project Rastko.

- Dvornik, Francis (1962). The Slavs in European History and Civilization. New Brunswick, New Jersey: Rutgers University Press.

- Fajfrić, Željko (7 December 2000). Котроманићи (in Serbian). Project Rastko.

- Fine, John Van Antwerp Jr. (1994) [1987]. The Late Medieval Balkans: A Critical Survey from the Late Twelfth Century to the Ottoman Conquest. Ann Arbor, Michigan: University of Michigan Press. ISBN 0-472-08260-4.

- Fostikov, Aleksandra (2002). "О Дмитру Краљевићу [About Dmitar Kraljević]" (in Serbian). Историјски часопис [Historical Review] (Belgrade: Istorijski institut) 49. ISSN 0350-0802.

- Gavrilović, Zaga (2001). Studies in Byzantine and Serbian Medieval Art. London: The Pindar Press. ISBN 978-1-899828-34-0.

- Jireček, Konstantin Josef (1911). Geschichte der Serben [History of the Serbs] (in German). 1. The Internet Archive.

- Karadžić, Vuk Stefanović (1852). Српски рјечник [Serbian dictionary]. Vienna: Vuk Stefanović Karadžić.

- Karadžić, Vuk Stefanović (11 October 2000). Српске народне пјесме [Serbian folk poems] (in Serbian). 2. Project Rastko.

- Konstantin the Philosopher (2000). Gordana Jovanović ed. Житије деспота Стефана Лазаревића [Biography of Despot Stefan Lazarević] (in Serbian). Project Rastko.

- Low, David Halyburton (1922). The Ballads of Marko Kraljević. The Internet Archive.

- Mandić, Ranko (2003). "Kraljevići Marko i Andreaš" (in Serbian). Dinar: Numizmatički časopis (Belgrade: Serbian Numismatic Society) No. 21. ISSN 1450-5185.

- Mihaljčić, Rade (1975). Крај Српског царства [The end of the Serbian Empire] (in Serbian). Belgrade: Srpska književna zadruga.

- Miklosich, Franz (1858). Monumenta serbica spectantia historiam Serbiae Bosnae Ragusii (in Serbian and Latin). The Internet Archive.

- Momirović, Petar (1956). "Stari rukopisi i štampane knjige u Čajniču" [Old manuscripts and printed books in Čajniče] (PDF). Naše starine (in Serbian). 3. Sarajevo: Zavod za zaštitu spomenika kulture Press.

- Nicol, Donald M. (1993) [1972]. The Last Centuries of Byzantium, 1261-1453. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-43991-6.

- Nicol, Donald M. (1996). The Reluctant Emperor: A Biography of John Cantacuzene, Byzantine Emperor and Monk, c. 1295-1383. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-52201-4.

- Noyes, George Rapall; Bacon, Leonard (1913). Heroic Ballads of Servia. The Internet Sacred Text Archive.

- Orbini, Mauro (1601). Il Regno de gli Slavi hoggi corrottamente detti Schiavoni. Pesaro: Apresso Girolamo Concordia.

- Орбин, Мавро (1968). Краљевство Словена. Београд: Српска књижевна задруга.

- Ostrogorsky, George (1956). History of the Byzantine State. Oxford: Basil Blackwell.

- Popović, Tatyana (1988). Prince Marko: The Hero of South Slavic Epics. New York: Syracuse University Press. ISBN 978-0-8156-2444-8.

- Radenković, Ljubinko (2001). "Краљевић Марко" (in Serbian). Svetlana Mikhaylovna Tolstaya, Ljubinko Radenković eds. Словенска митологија: Енциклопедијски речник [Slavic mythology: Encyclopedic dictionary]. Belgrade: Zepter Book World. ISBN 86-7494-025-0.

- Rudić, Srđan (2001). "O првом помену презимена Mрњавчевић [On the first mention of the Mrnjavčević surname]" (in Serbian). Историјски часопис [Historical Review] (Belgrade: Istorijski institut) 48. ISSN 0350-0802.

- Sedlar, Jean W. (1994). East Central Europe in the Middle Ages, 1000-1500. Seattle: University of Washington Press. ISBN 978-0-295-80064-6.

- Stojanović, Ljubomir (1902). Стари српски записи и натписи [Old Serbian inscriptions and superscriptions] (in Serbian). 1. Belgrade: Serbian Royal Academy.

- Soulis, George Christos (1984). The Serbs and Byzantium during the reign of Tsar Stephen Dušan (1331-1355) and his successors. Washington: Dumbarton Oaks Library and Collection. ISBN 978-0-88402-137-7.

- Šarenac, Darko (1996). Марко Краљевић у машти ликовних уметника (in Serbian). Belgrade: BIPIF. ISBN 978-86-82175-03-2.

- Šuica, Marko (2000). Немирно доба српског средњег века: властела српских обласних господара [The turbulent era of the Serbian Middle Ages: the noblemen of the Serbian regional lords] (in Serbian). Belgrade: Službeni list SRJ. ISBN 86-355-0452-6.

- Theiner, Augustin (1860). Vetera monumenta historica Hungariam sacram illustrantia (in Latin). 2. The Internet Archive.

External links

[edit]- The Ballads of Marko Kraljević, translated by David Halyburton Low (1922)

- Heroic Ballads of Servia, translated by George Rapall Noyes and Leonard Bacon (1913)

- Macedonian songs, fairy tales and legends about Marko (Macedonian)

- Bulgarian ballads (also here, with more information) and legends about Marko (Bulgarian)

- Marko, The King's Son: Hero of The Serbs by Clarence A. Manning (1932)

- Poem, "Marko Kraljević and the Vila"

- Conclusion of "Prince Marko and Musa Kesedžija" (verses 220–281)

- Web comic strip Archived 2009-01-09 at the Wayback Machine

Videos of Serbian epic poems sung to the accompaniment of the gusle:

Prince Marko

View on GrokipediaEarly Life

Birth and Family Background

Prince Marko Mrnjavčević, known posthumously as Kraljević Marko, was born circa 1335 as the eldest son of Vukašin Mrnjavčević.[1][3] Vukašin, a Serbian noble of the Mrnjavčević clan of probable Herzegovinian origin, ascended to prominence in the mid-14th century, eventually being crowned king in 1365 alongside the childless Tsar Stefan Uroš V, effectively co-ruling much of the fragmented Serbian lands.[1][3] The family's progenitor, Mrnjava, was a 14th-century figure whose descendants expanded influence through military service under earlier Serbian rulers.[3] Marko's mother was Alena, though identified as Jevrosima in folk tradition, reflecting the scarcity of contemporary primary sources on familial details.[1] Vukašin had several siblings, including Jovan Uglješa, Despot of Serres, who governed eastern territories, contributing to the family's regional power base centered in areas like Prilep and Kostur.[1] This noble lineage positioned Marko within the waning Serbian feudal structure, amid pressures from Ottoman expansion and internal dynastic weaknesses following the death of Stefan Dušan in 1355.[3] The Mrnjavčevićs exemplified the rise of regional lords in post-Dušan Serbia, leveraging administrative roles—Vukašin served as veliki čelnik (great chamberlain)—to consolidate holdings in Macedonia and Albania's fringes.[1] Marko's birth into this environment foreshadowed his inheritance of paternal domains, though exact birthplace records are absent, with Prilep later serving as his primary seat.[3]Upbringing and Early Influences

Marko Mrnjavčević was born around 1335 as the eldest son of Vukašin Mrnjavčević, a noble who initially served as a courtier in the Serbian royal entourage before securing the governorship of the Prilep region, establishing the family's primary power base in southern Serbian territories.[1] His mother was Alena, identified as Jevrosima in some accounts and folk tradition, possibly the sister of the local Serbian hero Momčilo.[1] Marko's formative years coincided with Vukašin's consolidation of influence amid the Serbian Empire's political fragmentation under Tsar Stefan Uroš V, who lacked a direct heir. By the mid-1360s, Vukašin had risen to the rank of co-king, granting Marko the titular role of "Young King" as prospective successor and involving him in the administration of Prilep and surrounding Macedonian lands.[1] This environment of dynastic ambition and regional lordship, centered on fortified strongholds like Prilep, exposed Marko to the exigencies of noble governance and military readiness during a time of intensifying Ottoman incursions into the Balkans. Contemporary charters and chronicles provide minimal insight into Marko's personal education or daily upbringing, focusing instead on familial titles and territorial holdings; no detailed accounts of his childhood training or specific mentors survive.[1] The Mrnjavčević household's Orthodox Christian milieu and the martial ethos of 14th-century Serbian nobility likely predominated, though such inferences derive from broader contextual evidence rather than direct references to Marko.Ascension and Rule

Inheritance After Maritsa (1371)

The Battle of Maritsa, also known as the Battle of Chernomen, occurred on September 26, 1371, resulting in the defeat of Serbian forces led by King Vukašin Mrnjavčević and his brother Despot Jovan Uglješa by Ottoman troops under Lala Şahin Pasha.[4] Vukašin and Uglješa both perished in the battle, leaving a power vacuum in the Mrnjavčević domains.[4] Prior to the battle, in 1370 or 1371, Vukašin had appointed his son Marko as co-ruler with the title of "young king" (rex iunior), while Uglješa's charters from the summer of 1371 explicitly designated Marko as successor due to the absence of Uglješa's own male heirs.[4] Marko thus inherited the extensive territories held by his father and uncle, encompassing regions from Prizren in the north to the Mesta River in the southeast, and extending south to Kostur and the Cherna River.[4] This included the Vardar Valley under Vukašin's control and Serres under Uglješa's administration, forming a large principality south of the Danube that incorporated much of Macedonia, parts of Albania, and sections of Serbia, with additional political influence in Montenegro and the Ohrid region.[4] Following the death of Tsar Stefan Uroš V in December 1371 without heirs, Marko assumed the de jure royal title as King of Serbia.[5][3] Initially, Marko exercised legitimate authority over these inherited lands, minting coins in Ohrid and receiving acknowledgment from local rulers, as evidenced by inscriptions and portraits in churches such as the one in Sushitsa village and his own monastery in Prilep.[4] However, the Serbian Empire's fragmentation accelerated, with regional lords detaching territories; by the late 1370s, Marko's effective control had contracted significantly to a smaller principality centered on Prilep in western Macedonia, where he ruled de facto as a regional lord.[4] To maintain his position, Marko accepted Ottoman suzerainty at an uncertain date post-1371, becoming a vassal rather than an independent sovereign.[5]Governance Under Ottoman Vassalage

Following the Battle of Maritsa in 1371, Marko Mrnjavčević acknowledged Ottoman suzerainty under Sultan Murad I, becoming a vassal ruler obligated to provide annual tribute and military support to the empire.[6] This arrangement preserved his local authority over the diminished Lordship of Prilep, centered on the fortified town of Prilep and surrounding regions in western Macedonia, after rival nobles seized larger portions of his inherited territories by 1377.[1] Marko's governance maintained elements of Serbian feudal administration, including the collection of local taxes and the mobilization of levies for both internal defense and Ottoman requisitions. He exercised autonomy in domestic affairs, as demonstrated by his minting of silver coins weighing approximately 1.11 grams, inscribed with Serbian Cyrillic legends proclaiming him as king, which circulated within his domain.[7] These numismatic issues, produced in limited varieties, reflect retained sovereign prerogatives despite vassal status, facilitating trade and economic control in a period of Ottoman expansion.[8] As a tributary, Marko fulfilled imperial demands by dispatching contingents for Ottoman campaigns, including conflicts against Christian neighbors, though direct records of his participation prior to 1395 remain sparse; notably, he did not participate in the Battle of Kosovo in 1389, which contributed to the relative stability of his principality. This dual role—loyal service to the sultan juxtaposed with stewardship of Christian Orthodox institutions—characterized his rule, balancing subjugation with pragmatic preservation of regional stability until his death.[9]Military Engagements

Battles and Campaigns

As an Ottoman vassal after inheriting his father's titles following the Serbian defeat at Maritsa on 27 September 1371, Prince Marko Mrnjavčević provided military support through levies from his Prilep domain but led no major independent campaigns recorded in contemporary accounts.[1] His engagements aligned with Sultan Bayezid I's expansionist efforts in the Balkans, where vassal princes like Marko supplied contingents for offensive operations against neighboring principalities, though specific battles prior to 1395 lack detailed attribution to his personal command in surviving chronicles.[1] Marko's most documented military action occurred at the Battle of Rovine on 17 May 1395, an Ottoman campaign to subdue Wallachia. Commanding a Serbian detachment within Bayezid's army of approximately 40,000 troops, including fellow vassal Stefan Lazarević, Marko faced Voivode Mircea I's forces of about 10,000, who exploited the swampy, forested terrain near the Argeș River for defensive advantage with archers and ambushes.[10] Marko and his brother Andreja led charges into the morass but were cut down amid the melee, as noted in the Dečani Chronicle.[10] The encounter proved inconclusive, with heavy Ottoman losses prompting withdrawal and Mircea retaining control, highlighting the limits of vassal contingents in quelling determined regional resistance.[10]Strategic Alliances and Conflicts

Following the catastrophic Serbian defeat at the Battle of Maritsa on September 26, 1371, which claimed the life of his father King Vukašin, Marko Mrnjavčević pragmatically accepted Ottoman suzerainty to safeguard his remaining domains in western Macedonia, particularly around Prilep and its fortress.[1] This vassal arrangement involved annual tribute payments, including jizya and poll taxes, in exchange for nominal autonomy, allowing Marko to retain de facto control over a diminished realm amid the empire's fragmentation.[11] Marko's strategic posture emphasized survival through submission rather than open resistance; he coordinated loosely with fellow Ottoman vassals such as Konstantin Dejanović and, later, Stefan Lazarević, sharing the burden of imperial levies without forming independent anti-Ottoman coalitions.[11] However, this fidelity contrasted with familial divisions, as his brothers Andrijaš and Dmitar renounced vassalage in 1394 amid a broader Balkan revolt against Sultan Bayezid I, fleeing to the Hungarian court for refuge and alliance against the Turks.[11] Marko's adherence likely stemmed from the vulnerability of his exposed position, deterring him from joining the uprising that briefly united Hungarian, Wallachian, and other forces. Territorial encroachments by opportunistic neighbors exacerbated Marko's precarious rule, with rival Serbian lords seizing substantial inherited lands by 1377, reducing his effective control to core holdings like Prilep and adjacent valleys.[1] These low-intensity conflicts arose from the post-Maritsa power vacuum, where nobles like those of the Dejanović family exploited weakened central authority without escalating to pitched battles under Marko's tenure. His one documented major engagement occurred on May 17, 1395, at the Battle of Rovine, where, compelled by Ottoman orders, he campaigned alongside Dejanović against Wallachian Prince Mircea I, resulting in his death and further Ottoman consolidation in the Balkans.[12] This final conflict underscored the vassal system's ultimate demands, as Marko fought fellow Christians to fulfill tributary obligations.[11]Death and Succession

Final Campaign at Rovine (1395)

In spring 1395, Sultan Bayezid I initiated a punitive expedition against Wallachia to counter Voivode Mircea I's raids into Ottoman domains and his support for anti-Ottoman coalitions.[1] As a longstanding Ottoman vassal since the late 1370s, Prince Marko Mrnjavčević was compelled to muster his forces and accompany the imperial army, alongside fellow Serbian lords Constantine Dragaš and Stefan Lazarević.[5] This obligation stemmed from the post-Kosovo Polje (1389) realignment, where surviving Serbian nobility affirmed loyalty to the sultan to retain semi-autonomous rule over their principalities.[1] The clash culminated in the Battle of Rovine on 17 May 1395, near the Argeș River in Oltenia, where Wallachian forces exploited marshy terrain for ambushes and hit-and-run tactics against the larger Ottoman host.[10] Marko commanded a contingent of his Prilep-based troops, contributing to the Ottoman vanguard or auxiliary wings, though specific tactical dispositions remain undocumented in surviving accounts.[5] According to the chronicler Konstantin the Philosopher in his biography of Despot Stefan Lazarević, before the battle Marko told Dragaš that he prayed for God to help the Christians, even if it meant his own death first.[13] Contemporary Serbian records, including the Dečani Chronicle, note the battle's ferocity, highlighting the deaths of Marko and Dragaš amid the fighting, while Lazarević demonstrated notable valor but survived.[14] Marko perished during the engagement, aged around 60, marking the end of his rule and direct line; no heirs are recorded as succeeding him immediately, leading to Ottoman oversight of his lands.[5] The battle itself ended inconclusively, with Bayezid withdrawing after heavy losses to regroup, allowing Mircea temporary respite before further Ottoman incursions in 1397.[10] Marko's participation underscores the precarious vassalage of Balkan Christian lords, compelled to war against fellow Christians to avert conquest, a dynamic rooted in Ottoman suzerainty's coercive tribute and military service demands.[1]Territorial Fragmentation

Marko Mrnjavčević died childless on 17 May 1395 during the Battle of Rovine, leaving no direct heir to his lordship centered on Prilep and encompassing territories in western Macedonia.[5] His brothers, Andrijaš and Dmitar, who had held subordinate roles in the region, proved unable to assert control; Andrijaš fled to Ragusa (modern Dubrovnik) and later Hungary around 1394–1403, while Dmitar similarly sought refuge abroad, abandoning any claim to the Mrnjavčević domains.[5] The resulting power vacuum facilitated rapid Ottoman intervention, as Marko had ruled as a vassal; by late 1395, Ottoman forces conquered Prilep and integrated Marko's holdings with the adjacent lands of the similarly deceased Konstantin Dragaš, forming an administrative province centered at Kyustendil.[5] [15] This absorption precluded inheritance by Serbian nobility and dissolved the lordship into Ottoman structure, with no recorded interim fragmentation among local lords or rival claimants.[15] The episode underscored the precariousness of post-1371 Serbian principalities, where the absence of dynastic continuity hastened territorial dissolution amid Ottoman expansion, reducing western Macedonian holdings from a semi-autonomous Serbian entity to direct imperial appendages without transitional division.[5]Patronage and Domestic Legacy

Architectural Contributions

Prince Marko contributed to religious architecture through the completion and decoration of the family endowment known as the Church of Saint Demetrius, commonly referred to as Marko's Monastery, located in the village of Markova Sušica near Skopje. Construction of the church began under his father, King Vukašin Mrnjavčević, around 1346, but Marko oversaw its finalization between 1376 and 1377, including the execution of its fresco program, which incorporated ideological and liturgical elements reflective of Mrnjavčević patronage.[2] The structure exemplifies late medieval Serbian ecclesiastical design, with preserved frescoes depicting donors and saints, underscoring Marko's role in sustaining Orthodox cultural continuity amid Ottoman overlordship. In secular architecture, Marko fortified his capital at Prilep with the Markovi Kuli complex, a medieval citadel constructed during the reigns of his father and himself in the 14th century. Positioned on a hill 120–180 meters above the Pelagonia Valley, the fortress featured defensive towers and walls adapted to the steep granite terrain, serving as a strategic stronghold until his death in 1395.[16][17] These works highlight Marko's pragmatic investments in defense and piety, prioritizing regional stability over expansive conquests.[16]Administrative and Cultural Policies

Marko Mrnjavčević governed the Lordship of Prilep as a semi-autonomous Ottoman vassal from 1371 until his death in 1395, administering a territory encompassing western Macedonia with Prilep as its capital. His rule entailed fulfilling tribute obligations to the Ottoman sultan, estimated at a fixed annual payment alongside military service when summoned, while preserving local feudal hierarchies inherited from his father Vukašin. This arrangement allowed Marko to maintain control over internal affairs, including land tenure, judicial authority over Orthodox subjects, and mobilization of regional levies, though no records detail innovative administrative reforms or centralized bureaucracies beyond standard medieval Balkan practices.[3][18] Administrative functions emphasized defensive preparedness and revenue extraction to sustain vassal commitments, with Prilep's fortress serving as a key hub for oversight. Marko fortified structures such as Markovi Kuli, a hilltop complex overlooking the region, to secure trade routes and deter internal unrest amid fragmented post-Maritsa power dynamics. Sources portray his governance as pragmatic rather than expansive, prioritizing stability in a vassal context over aggressive expansion, with limited evidence of codified laws or fiscal policies distinct from broader Serbian noble traditions.[19] In cultural policies, Marko actively patronized Orthodox religious institutions, reflecting a commitment to preserving Serbian ecclesiastical traditions under duress. He sponsored the completion and fresco decoration of the Monastery of St. Demetrius (known as Marko's Monastery) near Skopje, finalized in 1376–1377, featuring donor portraits and Byzantine-influenced iconography that underscored continuity with Nemanjić-era artistry. This endowment, initiated by Vukašin but fulfilled under Marko, supported monastic communities as centers of literacy, liturgy, and cultural resistance to Ottoman Islamization pressures. No evidence suggests suppression of local Slavic customs or promotion of non-Orthodox elements, aligning his patronage with confessional identity maintenance.[20][9]Historical Assessment

Achievements in Resistance and Rule

Prince Marko Mrnjavčević governed the Lordship of Prilep from 1371 until his death in 1395, maintaining a semi-autonomous status as an Ottoman vassal following the defeat and death of his father, King Vukašin, at the Battle of Maritsa on September 26, 1371. Centered on the town of Prilep in present-day North Macedonia, his domain included surrounding regions and allowed him to retain the royal title "Serbian king" while paying annual tribute to the Sultan, estimated at a fixed sum that preserved his local fiscal control. This arrangement enabled Marko to administer justice, collect internal taxes, and uphold Serbian noble traditions without direct Ottoman interference in daily rule.[3][1] In terms of resistance, Marko's achievements were pragmatic rather than defiant; he fortified key positions, including the construction of Markovi Kuli, a hilltop fortress overlooking Prilep completed during his reign to secure borders against local rivals and banditry prevalent in the post-Maritsa fragmentation. By 1377, he had lost peripheral territories to competing nobles like those under Constantine Dragaš but consolidated control over core lands, demonstrating effective military organization that deterred incursions and sustained stability for over two decades amid broader Balkan Ottoman expansion. His governance delayed full incorporation into the Ottoman timar system, preserving a Christian Serbian administrative cadre until territorial annexation shortly after 1395.[3] Marko's rule exemplified resilient adaptation, as he balanced vassal obligations—providing auxiliary troops for select Ottoman campaigns—with internal autonomy, fostering relative peace and economic continuity in Prilep through agriculture and trade routes under his protection. Historical records indicate no major revolts against his authority, underscoring competent leadership that maintained Orthodox Christian institutions and cultural continuity against assimilative pressures. This period of sustained semi-independence under duress constitutes his primary achievement in rule, contrasting with the rapid collapse of other Mrnjavčević holdings.[3][1]Criticisms of Vassalage and Collaboration

Prince Marko's acceptance of Ottoman vassalage shortly after his father Vukašin's defeat and death at the Battle of Maritsa on September 26, 1371, has drawn criticism from historians and nationalist interpreters for prioritizing personal rule over unified resistance against Ottoman expansion. Unlike contemporaries such as Prince Lazar Hrebeljanović, who delayed submission until after the Battle of Kosovo in 1389, Marko rapidly acknowledged Ottoman suzerainty, paying annual tribute estimated at 40,000 ducats and supplying auxiliary troops, which some argue facilitated the sultans' consolidation of power in the Balkans by diverting Serbian military resources from defensive coalitions.[3][1] Critics, including those in 19th-century Serbian historiography influenced by romantic nationalism, contend that Marko's collaboration extended to active participation in Ottoman offensives against fellow Christian rulers, most notably commanding a contingent at the Battle of Rovine on May 17, 1395, where he died fighting for Sultan Bayezid I against Wallachian voivode Mircea I. This engagement, part of Bayezid's campaign to enforce vassalage on Wallachia, is viewed by detractors as a direct contribution to Ottoman subjugation of neighboring states, weakening the fragmented Christian front and enabling further incursions into Serbian territories already eroded by rival nobles like Konstantin Dejanović.[3][10] In contrast to his brothers Andronikos and Ivan Mrnjavčević, who aligned with anti-Ottoman factions and lost domains for their defiance, Marko's pragmatic submission is lambasted in some scholarly assessments as emblematic of feudal self-preservation that eroded morale and loyalty among subjects, fostering perceptions of disunity amid existential threats. Such views, echoed in analyses of Balkan feudal dynamics, highlight how vassal obligations strained local economies through tribute and conscription, indirectly aiding Ottoman demographic and administrative infiltration without commensurate protection, as evidenced by the rapid loss of Marko's inherited lands post-1377 to opportunistic warlords.[11][4]Folklore and Epic Traditions

Serbian Epic Poetry

In Serbian epic poetry, Prince Marko, stylized as Marko Kraljević ("Marko's the King's Son"), anchors the Marko cycle, a corpus of decasyllabic oral poems recited to the accompaniment of the gusle, a single-stringed bowed instrument. These poems, transmitted through generations of South Slavic bards, elevate Marko from a historical regional ruler and pragmatic Ottoman vassal to a semi-mythical archetype of martial prowess and tragic fatalism, often depicting him as the last bulwark against Ottoman incursions and a protector of the weak despite his historical submission. Collected systematically in the early 19th century by Vuk Stefanović Karadžić, the cycle comprises dozens of songs emphasizing Marko's superhuman strength, loyalty to Christian emperors, and encounters with supernatural foes, reflecting collective memory of 14th-century Balkan upheavals rather than verbatim history.[21] Marko's legendary attributes include his faithful steed Šarac, a grey horse with prophetic insight, his massive mace or topuz weighing 66 oka forged from the "baba Dag" or attributed to foes like Musa, and alliances with supernatural figures such as the vila Ravijojla, symbolizing unyielding power amid inevitable decline. Poems portray him as melancholic and prescient of doom, frequently invoking rakija to steel his resolve before battles, as in narratives where he aids imperial figures like Tsar Dušan or Prince Lazar while grappling with personal betrayals and monstrous adversaries. This characterization diverges sharply from historical records, where Marko Mrnjavčević governed Prilep as an Ottoman tributary after 1371, participating in campaigns like the 1395 Battle of Rovine under Sultan Bayezid I; epics recast such submission as reluctant service masking heroic resistance, transforming the pragmatic vassal into a symbol of justice and defiance.[4] Prominent poems in the cycle include "Marko Kraljević and Musa Kesedžija," wherein Marko slays the three-hearted Albanian brigand Musa through cunning after direct combat fails, underscoring themes of trickery over brute force against overwhelming odds. Other key works feature "The Ploughing of Marko Kraljević," depicting him tilling vast fields in a single day as a metaphor for burdensome imperial duties, and "Marko Kraljević and the Vila," involving fairy-like beings who aid or test him on perilous quests. These narratives, often spanning 200-300 lines, employ formulaic epithets and motifs shared across the broader Serbian epic tradition, such as the "death foretold" trope, to evoke communal resilience during Ottoman domination. Scholarly analysis posits the cycle's formation post-1389 Battle of Kosovo, blending historical-mythical roots with influences from Byzantine akritic songs, though debates persist on Western chivalric impacts.[21][4] The Marko cycle's endurance in guslars' repertoires underscores its role in fostering ethnic identity, with bards like those recorded by Karadžić adapting songs to local dialects and contexts, yet preserving core motifs of heroism tempered by sorrow. Unlike pre-Kosovo or rebellion cycles, Marko's tales emphasize individual valor over collective battles, portraying a flawed yet indomitable figure whose exploits—slaying dragons, liberating captives, or dueling djinni—symbolize defiance against existential threats. This mythic inflation of Marko's agency critiques vassalage indirectly, attributing defeats to fate rather than collaboration, a narrative device aligning with oral traditions' causal realism in processing imperial collapse and contributing to his enduring symbolic role in Balkan identity.[21]Bulgarian and Macedonian Adaptations

In Bulgarian oral-traditional epics, Prince Marko, rendered as Krali Marko, is adapted with pronounced supernatural and pagan motifs, diverging from his historical portrayal as an Ottoman vassal by emphasizing shamanistic elements and otherworldly alliances, while portraying him as a fighter against Turks and symbol of resistance. His extraordinary strength is often attributed to nourishment from a vila (mountain fairy), as in narratives where she rewards him for sheltering her offspring by feeding him her milk, granting superhuman power.[22] These tales incorporate pre-Christian influences, such as his mythical upbringing by a nymph akin to the Thracian Great Goddess after being abandoned in a forest, linking him to ancient rock shrines like Markova Stapka near Pernik.[23] Heroic deeds blend historical resistance with legend, including prolonged battles against Ottoman figures like Musa Kesedzhiya at the Chernelka River, where he splits a rock with his sword, symbolizing defiance amid enslavement and invasion.[23] Such adaptations reflect 18th–19th-century nationalist reinterpretations, elevating Marko as a Christian protector while merging him with proto-Bulgar or Turkic mythic archetypes, distinct from Serbian epics' focus on dynastic loyalty, and reinforcing his place in broader Balkan identity.[22][4] Macedonian folklore integrates Marko deeply due to his rule over Prilep and surrounding territories from 1371 to 1395, positioning him as a regional symbol of resistance with epics tracing origins to this area, adapting the epic hero archetype to highlight contrasts with his historical pragmatism.[4] Local traditions, distinct from pan-South Slavic heroic cycles, portray him less uniformly idealized, incorporating human frailties alongside feats like aiding villagers or confronting tyrants, reflecting his historical vassalage and modest realm.[24] Unlike broader epics' supernatural emphasis, Macedonian variants often ground Marko in everyday locales, such as songs depicting interactions with ethnic Bulgarian-Macedonian communities under his governance, where he embodies cultural continuity amid Ottoman domination.[24] These adaptations underscore his role in fostering local identity, with motifs of freeing chained laborers or reacting to emerging firearms highlighting exaggerated expectations of a liberator figure, akin to but localized from Bulgarian portrayals, and contributing to his multifaceted symbolic presence across Balkan national identities.[4] Both traditions share epic cycles predating his lifetime, yet Macedonian ones prioritize territorial heritage over pagan mythology, adapting Marko as a flawed yet enduring Balkan archetype.[24][4]Legends and Mythic Archetype

Heroic Deeds and Supernatural Elements

In Serbian epic poetry, Prince Marko (Kraljević Marko) is depicted as possessing superhuman strength, often amplified by supernatural aid from vilas—winged mountain fairies—who intervene in his battles and provide prophetic guidance.[25][26] One recurring motif portrays his mother as a vila, endowing him with otherworldly prowess from birth, as in variants where King Vukašin marries a supernatural female spirit dwelling near mountain lakes.[25][26] His loyal steed, Šarac, a dappled horse of miraculous origin—sometimes described as a gift from a vila—exhibits equine intelligence, including the ability to speak and consume vast quantities of wine, enabling feats like outpacing divine entities or carrying Marko through impossible terrains.[25][27] A central heroic deed is Marko's duel with the giant Musa Kesedžija, a monstrous Albanian or Turkish warrior with three hearts symbolizing immense vitality; Marko, initially overpowered, prevails through cunning and vila intervention, where the fairy Ravijojla distracts Musa or reminds Marko of concealed daggers, allowing him to decapitate the foe and liberate oppressed subjects.[28][29] This victory underscores Marko's role as a protector against tyrannical invaders, blending martial skill with ethereal assistance to restore justice. Dragon-slaying narratives further elevate his archetype, as in epics where Marko combats serpentine beasts terrorizing villages, severing their heads with his massive mace or sword in acts echoing Indo-European heroic patterns of vanquishing chaos incarnate.[30][31] Supernatural elements often frame Marko's exploits as predestined trials, with vilas foretelling his death—such as poisoning by fairy-induced drought or betrayal—and Šarac mourning him posthumously, kicking mountains to form landmarks like Sleeping Beauty Peak, from which Marko is prophesied to awaken in Serbia's hour of need.[25][27] These motifs, preserved in oral decasyllabic verses collected from guslars (bardic performers), transform the historical prince into a mythic bulwark against Ottoman domination, though epics acknowledge his vassal status under the Sultan, rationalizing it as strategic endurance rather than submission.[28][30]Symbolic Role in Balkan Identity

In South Slavic epic traditions, Prince Marko, or Marko Kraljević, embodies the archetype of the defiant Christian warrior resisting Ottoman domination, serving as a potent symbol of collective resilience across Serbian, Bulgarian, and Macedonian folklore. Despite his historical status as an Ottoman vassal following the Battle of Maritsa in 1371, folk narratives elevate him as a protector of the oppressed and defender of Orthodox values, with epics portraying battles against Turkish adversaries and supernatural threats that underscore themes of unyielding bravery and moral integrity.[32][33] This mythic transformation reflects causal dynamics in oral transmission, where communal memory idealized fragmented medieval polities into unified heroic resistance, fostering a shared Balkan cultural ethos amid centuries of foreign rule.[34] Marko's legends function as a bridge in Balkan identity formation, transcending ethnic boundaries by invoking pan-South Slavic motifs of loyalty, cunning, and sacrificial heroism, as evidenced in hundreds of decasyllabic poems collected from the 19th century onward. In Serbian epics, he exemplifies the tragic king whose superhuman feats, such as wielding the mace Šećer or riding the enchanted horse Šarac, symbolize the indomitable spirit of the people against imperial subjugation. Bulgarian and Macedonian variants adapt these tales to localize heroism, yet retain core elements of anti-Ottoman struggle, thereby reinforcing a supranational narrative of endurance that predates modern nation-states.[35][36] This symbolic role persists in cultural memory, where Marko represents the mythic return of a savior-hero, akin to broader Indo-European patterns, linking historical defeat at Kosovo in 1389 to aspirational revival. Empirical analysis of epic corpora reveals his centrality in over 200 poems, underscoring how folklore constructs identity through exaggerated agency against verifiable historical constraints like vassal tribute payments documented in Ottoman defters from the 1390s. Such portrayals prioritize causal realism in myth-making—transforming vassal collaboration into emblematic defiance—to sustain ethnic morale under prolonged domination.[37]Modern Cultural Impact

Nationalism and Appropriation

In the 19th century, during the Serbian national revival amid Ottoman domination, epic poems featuring Prince Marko were instrumental in cultivating ethnic identity and resistance narratives. Philologist Vuk Stefanović Karadžić's collections of folk songs, published between 1814 and 1864, prominently included cycles portraying Marko as a formidable warrior against Turkish oppressors, elevating him as an archetypal defender of Christian Slavs despite his historical role as an Ottoman vassal. [38] [39] These texts, disseminated through print, reinforced a mythic Serbian continuity from medieval principalities to modern aspirations for autonomy, with Marko's exploits symbolizing unyielding spirit over vassalage realities. Serbian irredentist movements later invoked his legend to justify territorial ambitions in Macedonia, where he ruled, framing it as reclaiming ancestral lands. [38] Parallel appropriations occurred in Bulgarian folklore, where Marko—known as Krali Marko—was recast as a native son through localized tales blending pagan motifs with medieval history, such as origins tied to Thracian or proto-Bulgarian lineages. [23] Bulgarian nationalist historiography, emerging in the late 19th century alongside independence struggles, integrated these narratives to assert cultural primacy in the Balkans, portraying Marko as a protector of Orthodox populations under Ottoman yoke and downplaying his Serbian dynastic ties from the Mrnjavčević family. [36] This selective emphasis mirrored broader Balkan patterns of ethnicizing shared oral traditions, where empirical historical records—confirming Marko's Serbian noble origins and Prilep-based rule from 1371 to 1395—were subordinated to ideological needs for heroic forebears. [40] Macedonian adaptations similarly nationalized Marko during 20th-century identity formation, especially post-World War II under Yugoslav federalism and later independence, venerating him as a regional emblem of defiance tied to Prilep's geography and local toponyms like Markovi Kuli fortress. [24] In these contexts, folklore emphasized his deeds in Macedonian terrains, fostering a distinct Slavic identity amid disputes with Serbia and Bulgaria over historical precedence. [36] Yugoslav-era pan-South Slavic efforts, such as Ivan Meštrović's 1910 sculpture of Marko as a unified folk symbol, temporarily bridged claims, but dissolution revived exclusivist interpretations, with each nation's scholarship critiquing rivals' versions as distortions. [41] This competition highlights how pre-modern oral epics, fluid across ethnic lines under Ottoman millet systems, were retroactively partitioned by modern nationalism, prioritizing mythic utility over verifiable 14th-century genealogy. [42] Such appropriations extended to military nomenclature and symbolism; in interwar Yugoslavia and later Serbian forces, units bore Marko's name to evoke epic valor, while Bulgarian defenses during World War II invoked the "Krali Marko Line" for fortifications. [43] Nationalist biases in regional academia—often state-influenced—tend to amplify exclusive claims, sidelining evidence of Marko's Serbian self-identification via charters and alliances, thus illustrating causal dynamics where folklore's ambiguity enabled ideological capture rather than fidelity to primary sources like Dubrovnik archives from 1370s delegations. [44]Depictions in Art, Literature, and Media