Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

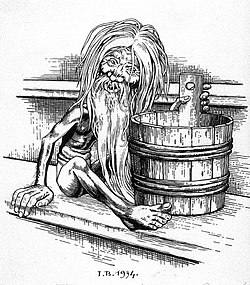

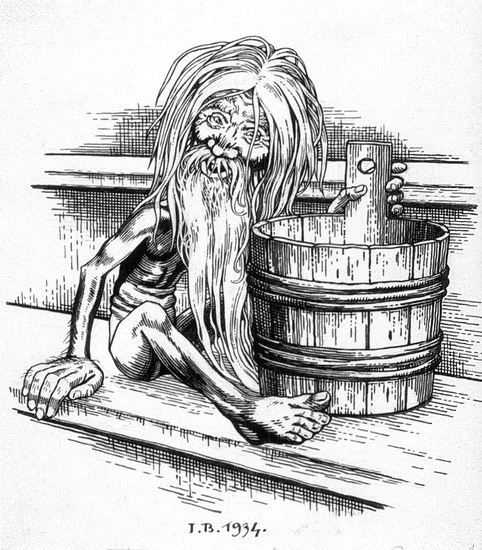

Bannik

View on Wikipedia

The Bannik (Cyrillic: Банник) is a bathhouse (banya) spirit in Slavic mythology.[1] He is usually described as a small, naked old man with a long beard, his body covered in the birch leaves left over from well used bath brooms.[2] Many accounts also claim that he is a shapeshifter and can appear as a local person to someone who stumbles across him,[3] or even as a stone or coal in the oven heating the bathhouse.[4] Slavic bathhouses resemble saunas, with an inner steaming room and an outer changing room. A place where women gave birth and practiced divinations, the bathhouse was strongly endowed with vital forces. The third firing (or fourth, depending on tradition) was reserved for the bannik, and, given his inclination to invite demons and forest spirits to share his bath, no Christian images were allowed lest they offend the occupants. If disturbed by an intruder while washing, the bannik might pour boiling water over him, or even strangle him.[1]

There were several rituals performed in order to keep the bannik happy and peaceful. The most common occurred during the steaming/firing that was reserved for the spirit itself or upon the quitting of the banya for the night; offerings of fir branches, water and soap were left, capped by a formal thank you uttered aloud.[3][4] The bannik was often blamed for anything that went wrong within the bathhouse, so if the structure burned down (which they often did), it was believed the spirit had been affronted in some way. In order to appease the bannik, upon the rebuilding of a banya, a black hen would be suffocated, left unplucked and buried beneath the building's threshold. The people performing this ritual would end it by bowing and backing away from the threshold, while reciting appropriate incantations.[3][4]

The banya was considered a liminal space among Slavic peasants and thus, was considered "unclean", or a place of possible spiritual danger. Despite this, most births occurred inside the banya and it was believed that the bannik was not truly happy or settled until a child was born within his domain.[3]

The bannik had the ability to predict the future. One consulted him by standing with one's back exposed in the half-open door of the bath. The bannik would gently stroke one's back if all boded well; but if trouble lay ahead, he would strike with his claws.[1]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b c Alexinsky, G. Slavonic Mythology in New Larousse Encyclopedia of Mythology. Prometheus Press, 1973, p. 287-88

- ^ Dixon-Kennedy, Mike (1997). European Myth & Legend: An A-Z of People and Places. London: Blandford. ISBN 9780713726763.

- ^ a b c d Ivanits, Linda J. (1989). Russian Folk Belief. Armonk, New York: ME Sharpe, Inc. ISBN 9780873324229.

- ^ a b c Gilchrist, Cherry (2009). Russian Magic: Living Folk Traditions of an Enchanted Landscape. Quest Books. ISBN 978-0835608749.