Recent from talks

Contribute something

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Visual arts

View on Wikipedia

The visual arts are art forms such as painting, drawing, printmaking, sculpture, ceramics, photography, video, image, filmmaking, design, crafts, and architecture. Many artistic disciplines such as performing arts, conceptual art, and textile arts, also involve aspects of the visual arts, as well as arts of other types. Within the visual arts,[1] the applied arts,[2] such as industrial design, graphic design, fashion design, interior design, and decorative art[3] are also included.

Current usage of the term "visual arts" includes fine art as well as applied or decorative arts and crafts, but this was not always the case. Before the Arts and Crafts Movement in Britain and elsewhere at the turn of the 20th century, the term 'artist' had for some centuries often been restricted to a person working in the fine arts (such as painting, sculpture, or printmaking) and not the decorative arts, crafts, or applied visual arts media. The distinction was emphasized by artists of the Arts and Crafts Movement, who valued vernacular art forms as much as high forms.[4] Art schools made a distinction between the fine arts and the crafts, maintaining that a craftsperson could not be considered a practitioner of the arts.

The increasing tendency to privilege painting, and to a lesser degree sculpture, above other arts has been a feature of Western art as well as East Asian art. In both regions, painting has been seen as relying to the highest degree on the imagination of the artist and being the furthest removed from manual labour – in Chinese painting, the most highly valued styles were those of "scholar-painting", at least in theory practiced by gentleman amateurs. The Western hierarchy of genres reflected similar attitudes.

Education and training

[edit]Training in the visual arts has generally been through variations of the apprentice and workshop systems. In Europe, the Renaissance movement to increase the prestige of the artist led to the academy system for training artists, and today most of the people who are pursuing a career in the arts train in art schools at tertiary levels. Visual arts have now become an elective subject in most education systems.[5][6]

In East Asia, arts education for nonprofessional artists typically focused on brushwork; calligraphy was numbered among the Six Arts of gentlemen in the Chinese Zhou dynasty, and calligraphy and Chinese painting were numbered among the four arts of scholar-officials in imperial China.[7][8][9]

Leading country in the development of the arts in Latin America, in 1875 created the National Society of the Stimulus of the Arts, founded by painters Eduardo Schiaffino, Eduardo Sívori, and other artists. Their guild was rechartered as the National Academy of Fine Arts in 1905 and, in 1923, on the initiative of painter and academic Ernesto de la Cárcova, as a department in the University of Buenos Aires, the Superior Art School of the Nation. Currently, the leading educational organization for the arts in the country is the UNA Universidad Nacional de las Artes.[10]

Drawing

[edit]

Drawing is a means of making an image, illustration or graphic using any of a wide variety of tools and techniques available online and offline. It generally involves making marks on a surface by applying pressure from a tool, or moving a tool across a surface using dry media such as graphite pencils, pen and ink, inked brushes, wax color pencils, crayons, charcoals, pastels, and markers. Digital tools, including pens, stylus, that simulate the effects of these are also used. The main techniques used in drawing are: line drawing, hatching, crosshatching, random hatching, shading, scribbling, stippling, and blending. An artist who excels at drawing is referred to as a draftsman or draughtsman.[11]

Drawing and painting go back tens of thousands of years.[12] Art of the Upper Paleolithic includes figurative art beginning at least 40,000 years ago.[13] Non-figurative cave paintings consisting of hand stencils and simple geometric shapes are even older.[12] Paleolithic cave representations of animals are found in areas such as Lascaux, France, Altamira, Spain,[14] Maros, Sulawesi in Asia,[15] and Gabarnmung, Australia.[16]

In ancient Egypt, ink drawings on papyrus, often depicting people, were used as models for painting or sculpture.[17] Drawings on Greek vases, initially geometric, later developed into the human form with black-figure pottery during the 6th century BC.[18]

With paper becoming more common in Europe by the 14th century,[19] drawing was adopted by masters such as Sandro Botticelli, Raphael, Michelangelo, and Leonardo da Vinci, who sometimes treated drawing as an art in its own right, rather than a preparatory stage for painting or sculpture.[20]

Painting

[edit]Painting taken literally is the practice of applying pigment suspended in a carrier (or medium) and a binding agent (a glue) to a surface (support) such as paper, canvas or a wall. However, when used in an artistic sense it means the use of this activity in combination with drawing, composition, or other aesthetic considerations in order to manifest the expressive and conceptual intention of the practitioner. Painting is also used to express spiritual motifs and ideas; sites of this kind of painting range from artwork depicting mythological figures on pottery to The Sistine Chapel, to the human body itself.[21]

History

[edit]Origins and early history

[edit]

Like drawing, painting has its documented origins in caves and on rock faces.[22] The earliest known cave paintings, dating to between 32,000-30,000 years ago, are found in the Chauvet cave in southern France;[23] the celebrated polychrome murals of Lascaux date to around 17,000–15,500 years ago.[24] In shades of red, brown, yellow and black, the paintings on the walls and ceilings depict bison, cattle (aurochs), horses and deer.[25]

Paintings of human figures can be found in the tombs of ancient Egypt. In the great temple of Ramesses II, Nefertari, his queen, is depicted being led by Isis.[26] The Greeks contributed to painting but much of their work has been lost. One of the best remaining representations are the Hellenistic Fayum mummy portraits. Another example is mosaic of the Battle of Issus at Pompeii, which was probably based on a Greek painting. Greek and Roman art contributed to Byzantine art in the 4th century BC, which initiated a tradition in icon painting.[27]

The Renaissance

[edit]Apart from the illuminated manuscripts produced by monks during the Middle Ages, the next significant contribution to European art was from Italy's renaissance painters. From Giotto in the 13th century to Leonardo da Vinci and Raphael at the beginning of the 16th century, this was the richest period in Italian art as the chiaroscuro techniques were used to create the illusion of 3-D space.[28]

Painters in northern Europe too were influenced by the Italian school. Jan van Eyck from Belgium, Pieter Bruegel the Elder from the Netherlands and Hans Holbein the Younger from Germany are among the most successful painters of the times. They used the glazing technique with oils to achieve depth and luminosity.

Dutch masters

[edit]

The 17th century witnessed the emergence of the great Dutch masters such as the versatile Rembrandt who was especially remembered for his portraits and Bible scenes, and Vermeer who specialized in interior scenes of Dutch life.

Baroque

[edit]The Baroque started after the Renaissance, from the late 16th century to the late 17th century. Main artists of the Baroque included Caravaggio, who made heavy use of tenebrism. Peter Paul Rubens, a Flemish painter who studied in Italy, worked for local churches in Antwerp and also painted a series for Marie de' Medici. Annibale Carracci took influences from the Sistine Chapel and created the genre of illusionistic ceiling painting. Much of the development that happened in the Baroque was because of the Protestant Reformation and the resulting Counter Reformation. Much of what defines the Baroque is dramatic lighting and overall visuals.[29]

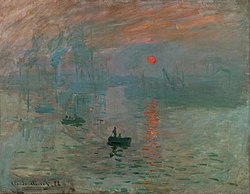

Impressionism

[edit]

Impressionism began in France in the 19th century with a loose association of artists including Claude Monet, Pierre-Auguste Renoir and Paul Cézanne who brought a new freely brushed style to painting, often choosing to paint realistic scenes of modern life outside rather than in the studio. This was achieved through a new expression of aesthetic features demonstrated by brush strokes and the impression of reality. They achieved intense color vibration by using pure, unmixed colors and short brush strokes. The movement influenced art as a dynamic, moving through time and adjusting to newfound techniques and perception of art. Attention to detail became less of a priority in achieving, whilst exploring a biased view of landscapes and nature to the artist's eye.[30][31]

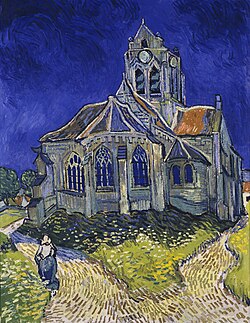

Post-impressionism

[edit]Towards the end of the 19th century, several young painters took impressionism a stage further, using geometric forms and unnatural color to depict emotions while striving for deeper symbolism. Of particular note are Paul Gauguin, who was strongly influenced by Asian, African and Japanese art, Vincent van Gogh, a Dutchman who moved to France where he drew on the strong sunlight of the south, and Toulouse-Lautrec, remembered for his vivid paintings of night life in the Paris district of Montmartre.[32]

Symbolism, expressionism and cubism

[edit]Edvard Munch, a Norwegian artist, developed his symbolistic approach at the end of the 19th century, inspired by the French impressionist Manet. The Scream (1893), his most famous work, is widely interpreted as representing the universal anxiety of modern man. Partly as a result of Munch's influence, the German expressionist movement originated in Germany at the beginning of the 20th century as artists such as Ernst Kirschner and Erich Heckel began to distort reality for an emotional effect.

In parallel, the style known as cubism developed in France as artists focused on the volume and space of sharp structures within a composition. Pablo Picasso and Georges Braque were the leading proponents of the movement. Objects are broken up, analyzed, and re-assembled in an abstracted form. By the 1920s, the style had developed into surrealism with Dali and Magritte.[33]

Printmaking

[edit]

Printmaking is creating, for artistic purposes, an image on a matrix that is then transferred to a two-dimensional (flat) surface by means of ink or other form of pigmentation.[34] Except in the case of a monotype, the same matrix can be used to produce many examples of the print.[35]

Historically, the major techniques (also called media) involved are woodcut,[36] line engraving,[37] etching,[38] lithography,[39] and screen printing,[40] (serigraphy, silk screening) and there are many others, including digital techniques.[41] Normally, the print is printed on paper,[19] but other mediums range from cloth and vellum,[42] to more modern materials.[43]

European history

[edit]Prints in the Western tradition produced before about 1830 are known as old master prints. In Europe, from around 1400 AD woodcut, was used for master prints on paper by using printing techniques developed in the Byzantine and Islamic worlds. Michael Wolgemut improved German woodcut from about 1475, and Erhard Reuwich, a Dutchman, was the first to use cross-hatching. At the end of the century Albrecht Dürer brought the Western woodcut to a stage that has never been surpassed, increasing the status of the single-leaf woodcut.[44]

Chinese origin and practice

[edit]

In China, the art of printmaking developed some 1,100 years ago as illustrations alongside text cut in woodblocks for printing on paper. Initially images were mainly religious but in the Song dynasty, artists began to cut landscapes. During the Ming (1368–1644) and Qing (1616–1911) dynasties, the technique was perfected for both religious and artistic engravings.[45][46]

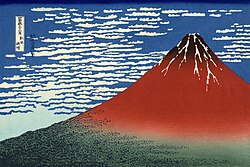

Development in Japan, 1603–1867

[edit]

Woodblock printing in Japan (Japanese: 木版画, moku hanga) is a technique best known for its use in the ukiyo-e artistic genre; however, it was also used very widely for printing illustrated books in the same period. Woodblock printing had been used in China for centuries to print books, long before the advent of movable type, but was only widely adopted in Japan during the Edo period (1603–1867).[47][48] Although similar to woodcut in western printmaking in some regards, moku hanga differs greatly in that water-based inks are used (as opposed to western woodcut, which uses oil-based inks), allowing for a wide range of vivid color, glazes and color transparency.

After the decline of ukiyo-e and introduction of modern printing technologies, woodblock printing continued as a method for printing texts as well as for producing art, both within traditional modes such as ukiyo-e and in a variety of more radical or Western forms that might be construed as modern art. In the early 20th century, shin-hanga that fused the tradition of ukiyo-e with the techniques of Western paintings became popular, and the works of Hasui Kawase and Hiroshi Yoshida gained international popularity.[49][50] Institutes such as the "Adachi Institute of Woodblock Prints" and "Takezasado" continue to produce ukiyo-e prints with the same materials and methods as used in the past.[51][52]

Photography

[edit]Photography is the process of making pictures by means of the action of light. The light patterns reflected or emitted from objects are recorded onto a sensitive medium, or storage chip, through a timed exposure.[53] The process is done through mechanical shutters[54] or electronically timed exposure of photons into chemical processing or digitizing devices known as cameras.[55]

The word comes from the Greek φῶς ‘’phos’’ ("light") and γραφή ‘’graphê’’ ("drawing" or "writing"), literally meaning "drawing with light".[56] Traditionally, the product of photography has been called a photograph; the term ‘’photo’’ is an abbreviation and though many call them "pictures," the term "image" has increasingly replaced "photograph," reflecting electronic capture and the broader concept of graphical representation in optics and computing.[57]

Architecture

[edit]

Architecture is the process and the product of planning, designing, and constructing buildings or any other structures.[58] Architectural works, in the material form of buildings, are often perceived as cultural symbols and works of art.[59] Historical civilizations are often identified with their surviving architectural achievements.[60]

The earliest surviving written work on architecture is De architectura, by the Roman architect Vitruvius in the early 1st century AD.[61] According to Vitruvius, a good building should satisfy three principles: firmitas, utilitas, venustas, translated as firmness, commodity, and delight.[62] An equivalent in modern English would be:

- Durability – a building should stand up robustly and remain in good condition.

- Utility – it should be suitable for the purposes for which it is used.

- Beauty – it should be aesthetically pleasing.[63]

Building first evolved out of the dynamics between needs (shelter, security, worship, etc.) and means (available building materials and attendant skills).[64] As cultures developed and knowledge began to be formalized through oral traditions and practices, building became a craft, and "architecture" is the name given to the most highly formalized versions of that craft.[65]

Filmmaking

[edit]Filmmaking is the process of making a motion picture, from an initial conception and research, through scriptwriting, shooting and recording, animation or other special effects, editing, sound and music work and finally distribution to an audience; it refers broadly to the creation of all types of films, embracing documentary, strains of theatre and literature in film, and poetic or experimental practices, and is often used to refer to video-based processes as well.

Computer art

[edit]

Visual artists are no longer limited to traditional visual arts media. Computers have been used in the visual arts since the 1960s.[66] Uses include the capturing or creating of images and forms,[67] the editing of those images (including exploring multiple compositions)[68] and the final rendering or printing (including 3D printing).[69]

Computer art is any in which computers play a role in production or display.[70] Such art can be an image, sound, animation, video, CD-ROM, DVD, video game, website, algorithm, performance or gallery installation.[71]

Many traditional disciplines now integrate digital technologies, so the lines between traditional works of art and new media works created using computers have been blurred.[72] For instance, an artist may combine traditional painting with algorithmic art and other digital techniques.[73] As a result, defining computer art by its end product can be difficult. Nevertheless, this type of art appears in art museum exhibits, but can be seen more as a tool, rather than a form as with painting.[74] On the other hand, there are computer-based artworks which belong to a new conceptual and postdigital strand, assuming the same technologies, and their social impact, as an object of inquiry.[75]

Computer usage has blurred the distinctions between illustrators, photographers, photo editors, 3-D modelers, and handicraft artists.[76] Sophisticated rendering and editing software has led to multi-skilled image developers. Photographers may become digital artists.[77] Illustrators may become animators. Handicraft may be computer-aided or use computer-generated imagery as a template.[78] Computer clip art usage has made the distinction between visual arts and page layout less obvious due to the easy access and editing of clip art in the process of paginating a document.[79]

Plastic arts

[edit]Plastic arts is a term for art forms that involve physical manipulation of a plastic medium by moulding or modeling such as sculpture or ceramics. The term has also been applied to all the visual (non-literary, non-musical) arts.[80][81]

Materials that can be carved or shaped, such as stone, wood, concrete, or steel, have also been included in the narrower definition, since, with appropriate tools, such materials are also capable of modulation.[82] This use of the term "plastic" in the arts is different from Piet Mondrian’s use, and with the movement he termed, "Neoplasticism."[83][84]

Sculpture

[edit]Sculpture is three-dimensional artwork created by shaping or combining hard or plastic material, sound, or text and or light, commonly stone (either rock or marble), clay, metal, glass, or wood. Some sculptures are created directly by finding or carving; others are assembled, built together and fired, welded, molded, or cast. Sculptures are often painted.[85] A person who creates sculptures is called a sculptor.

The earliest undisputed examples of sculpture belong to the Aurignacian culture, which was located in Europe and southwest Asia and active at the beginning of the Upper Paleolithic. As well as producing some of the earliest known cave art, the people of this culture developed finely crafted stone tools, manufacturing pendants, bracelets, ivory beads, and bone-flutes, as well as three-dimensional figurines.[86][87][88]

Because sculpture involves the use of materials that can be moulded or modulated, it is considered one of the plastic arts. The majority of public art is sculpture. Many sculptures together in a garden setting may be referred to as a sculpture garden. Sculptors do not always make sculptures by hand. With increasing technology in the 20th century and the popularity of conceptual art over technical mastery, more sculptors turned to art fabricators to produce their artworks. With fabrication, the artist creates a design and pays a fabricator to produce it. This allows sculptors to create larger and more complex sculptures out of materials like cement, metal and plastic, that they would not be able to create by hand. Sculptures can also be made with 3-d printing technology.

US copyright definition of visual art

[edit]In the United States, the law protecting the copyright over a piece of visual art gives a more restrictive definition of "visual art".[89]

A "work of visual art" is —

(1) a painting, drawing, print or sculpture, existing in a single copy, in a limited edition of 200 copies or fewer that are signed and consecutively numbered by the author, or, in the case of a sculpture, in multiple cast, carved, or fabricated sculptures of 200 or fewer that are consecutively numbered by the author and bear the signature or other identifying mark of the author; or

(2) a still photographic image produced for exhibition purposes only, existing in a single copy that is signed by the author, or in a limited edition of 200 copies or fewer that are signed and consecutively numbered by the author.

A work of visual art does not include —

(A)(i) any poster, map, globe, chart, technical drawing, diagram, model, applied art, motion picture or other audiovisual work, book, magazine, newspaper, periodical, data base, electronic information service, electronic publication, or similar publication;

(ii) any merchandising item or advertising, promotional, descriptive, covering, or packaging material or container;

(iii) any portion or part of any item described in clause (i) or (ii);

(B) any work made for hire; or

(C) any work not subject to copyright protection under this title.[89]

See also

[edit]- Art materials

- Asemic writing

- Collage

- Conservation and restoration of cultural property

- Crowdsourcing

- Décollage

- Environmental art

- Found object

- Graffiti

- History of art

- Installation art

- Interactive art

- Landscape painting

- Mathematics and art

- Mixed media

- Portrait painting

- Process art

- Recording medium

- Sketch (drawing)

- Sound art

- Theosophy and visual arts

- Vexillography

- Video art

- Visual impairment in art

- Visual poetry

References

[edit]- ^ An About.com article by art expert, Shelley Esaak: What Is Visual Art? Archived 2 July 2015 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Different Forms of Art – Applied Art. Buzzle.com. Retrieved 11 December 2010.

- ^ "Centre for Arts and Design in Toronto, Canada". Georgebrown.ca. 15 February 2011. Archived from the original on 28 October 2011. Retrieved 30 October 2011.

- ^ Art History: Arts and Crafts Movement: (1861–1900). From World Wide Arts Resources Archived 13 October 2009 at the Portuguese Web Archive. Retrieved 24 October 2009.

- ^ Ulger, Kani (1 March 2016). "The creative training in the visual arts education". Thinking Skills and Creativity. 19: 73–87. doi:10.1016/j.tsc.2015.10.007. ISSN 1871-1871.

- ^ Adrone, Gumisiriza. "School of industrial art and design". Archived from the original on 20 February 2022. Retrieved 11 August 2020.

- ^ Welch, Patricia Bjaaland (2008). Chinese Art: A Guide to Motifs and Visual Imagery. Tuttle. p. 226. ISBN 978-0804838641.

- ^ Eisner, Elliot W.; Day, Michael D. (2004). Handbook of Research and Policy in Art Education. Routledge. p. 769. ISBN 1135612315.

- ^ Atkinson, Dennis (2003). "Forming Teacher Identities in ITE". In Addison, Nicholas; Burgess, Lesley (eds.). Issues in Art and Design Teaching. Psychology Press. p. 195. ISBN 0415266696.

- ^ Institutional Transformation IUNA – Law 24.521, Ministry of Justice & Education, Argentina (text in Spanish) / http://servicios.infoleg.gob.ar/infolegInternet/anexos/40000-44999/40779/norma.htm

- ^ "drawing | Principles, Techniques, & History". Encyclopedia Britannica. Archived from the original on 13 August 2020. Retrieved 12 August 2020.

- ^ a b "Cave art". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 2 May 2025.

- ^ "World's Oldest Known Figurative Paintings Discovered in Borneo Cave". Smithsonian Magazine. Retrieved 2 May 2025.

- ^ "Lascaux". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 2 May 2025.

- ^ "World's oldest cave painting in Indonesia shows a pig and people". Reuters. Reuters. 3 July 2024. Retrieved 2 May 2025.

- ^ "Nawarla Gabarnmang". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 2 May 2025.

- ^ "Egyptian art". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 2 May 2025.

- ^ "History of Drawing". Dibujos para Pintar. Archived from the original on 20 November 2010. Retrieved 2 May 2025.

- ^ a b "Paper". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 2 May 2025.

- ^ "Renaissance art". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 2 May 2025.

- ^ "painting | History, Elements, Techniques, Types, & Facts". Encyclopedia Britannica. Archived from the original on 22 July 2019. Retrieved 12 August 2020.

- ^ Valladas, Hélène (1 September 2003). "Direct radiocarbon dating of prehistoric cave paintings by accelerator mass spectrometry". Measurement Science and Technology. 14 (9): 1487–1492. doi:10.1088/0957-0233/14/9/301.

- ^ Quiles, Anita; Valladas, Hélène; Van der Plicht, Johannes; Delannoy, Jean-Jacques (11 April 2016). "A high-precision chronological model for the decorated Upper Paleolithic cave of Chauvet-Pont d'Arc, Ardèche, France". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 113 (17): 4670–4675. Bibcode:2016PNAS..113.4670Q. doi:10.1073/pnas.1523158113. PMC 4855545. PMID 27071106.

- ^ "Dating the figures at Lascaux". Ministère de la Culture et de la Communication. Retrieved 2 May 2025.

- ^ "Hall of Bulls, Lascaux". Smarthistory. Retrieved 2 May 2025.

- ^ History of Painting. From History World Archived 12 June 2010 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved 23 October 2009.

- ^ "Art history | visual arts". Encyclopedia Britannica. Archived from the original on 2 August 2020. Retrieved 12 August 2020.

- ^ History of Renaissance Painting. From ART 340 Painting Archived 25 January 2010 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved 24 October 2009.

- ^ Mutsaers, Inge. "Ashgate Joins Routledge – Routledge" (PDF). Ashgate.com. Archived (PDF) from the original on 5 November 2014. Retrieved 15 October 2018.

- ^ "Impressionist art & paintings, What is Impressionist art? Introduction to Impressionism". Archived from the original on 29 March 2019. Retrieved 24 September 2018.

- ^ Impressionism. Webmuseum, Paris. Archived 16 October 2009 at the Wayback Machine Retrieved 24 October 2009

- ^ Post-Impressionism. Metropolitan Museum of Art Archived 7 July 2019 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved 25 October 2009.

- ^ Modern Art Movements. Irish Art Encyclopedia Archived 26 January 2010 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved 25 October 2009.

- ^ "Printmaking". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 2 May 2025.

- ^ "Monotype". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 2 May 2025.

- ^ "Woodcut". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 2 May 2025.

- ^ "Engraving". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 2 May 2025.

- ^ "Etching". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 2 May 2025.

- ^ "Lithography". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 2 May 2025.

- ^ "Screen printing". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 2 May 2025.

- ^ "Digital printing". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 2 May 2025.

- ^ "Vellum". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 2 May 2025.

- ^ "Art materials". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 2 May 2025.

- ^ The Printed Image in the West: History and Techniques. The Metropolitan Museum of Art Archived 8 September 2009 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved 25 October 2009.

- ^ Engraving in Chinese Art. From Engraving Review Archived 29 July 2012 at archive.today. Retrieved 23 October 2009.

- ^ The History of Engraving in China. From ChinaVista Archived 17 October 2018 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved 25 October 2009.

- ^ "Japanese Woodblock Prints". Archived from the original on 23 July 2023. Retrieved 23 July 2023.

- ^ The Past, Present and Future of Printing in Japan. Izumi Munemura. (2010). The Surface Finishing Society of Japan.

- ^ Shin hanga bringing ukiyo-e back to life. Archived 2021-05-02 at the Wayback Machine The Japan Times.

- ^ Junko Nishiyama. (2018) 新版画作品集 ―なつかしい風景への旅. p. 18. Tokyo Bijutsu. ISBN 978-4808711016

- ^ "浮世絵・木版画のアダチ版画研究所". Archived from the original on 19 October 2023. Retrieved 21 February 2014.

- ^ 木版印刷・伝統木版画工房 竹笹堂. Archived from the original on 26 February 2014. Retrieved 7 November 2014.

- ^ "Exposure technique". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 2 May 2025.

- ^ "Shutter (photography)". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 2 May 2025.

- ^ "Camera". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 2 May 2025.

- ^ "Photography". Merriam-Webster. Retrieved 2 May 2025.

- ^ "History of photography". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 2 May 2025.

- ^ "Architecture". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 2 May 2025.

- ^ "Architecture – Symbols of function". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 2 May 2025.

- ^ "History of architecture". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 2 May 2025.

- ^ "On Architecture". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 2 May 2025.

- ^ Rowland, Ingrid (1999). Howe, Thomas Noble (ed.). Ten Books on Architecture. Cambridge University Press.

- ^ "Vitruvius's Principles". LacusCurtius. Retrieved 2 May 2025.

- ^ "Building". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 2 May 2025.

- ^ "Craft". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 2 May 2025.

- ^ "Computer art". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 2 May 2025.

- ^ "Digital imaging". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 2 May 2025.

- ^ "Image editing software". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 2 May 2025.

- ^ "3D printing". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 2 May 2025.

- ^ "Definition of computer art". Merriam-Webster. Retrieved 2 May 2025.

- ^ "New media art". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 2 May 2025.

- ^ "Digital art". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 2 May 2025.

- ^ "Algorithmic art". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 2 May 2025.

- ^ Paul, Christiane (2019). "Digital Art as Tool". Art Journal. 78 (3): 20–35.

- ^ "Post-digital art". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 2 May 2025.

- ^ "Multimedia artist". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 2 May 2025.

- ^ "Digital photographer". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 2 May 2025.

- ^ "Computer-generated imagery". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 2 May 2025.

- ^ "Clip art". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 2 May 2025.

- ^ Art Terminology at KSU[dead link]

- ^ "Merriam-Webster Online (entry for "plastic arts")". Merriam-webster.com. Archived from the original on 1 April 2019. Retrieved 30 October 2011.

- ^ "Plastic arts". Merriam-Webster. Retrieved 2 May 2025.

- ^ "Piet Mondrian". Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum. Retrieved 2 May 2025.

- ^ "Neoplasticism". Tate. Retrieved 2 May 2025.

- ^ Gods in Color: Painted Sculpture of Classical Antiquity 22 September 2007 Through 20 January 2008, The Arthur M. Sackler Museum Archived 4 January 2009 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ P. Mellars, Archeology and the Dispersal of Modern Humans in Europe: Deconstructing the Aurignacian, Evolutionary Anthropology, vol. 15 (2006), pp. 167–82.

- ^ de Laet, Sigfried J. (1994). History of Humanity: Prehistory and the beginnings of civilization. UNESCO. p. 211. ISBN 978-92-3-102810-6.

- ^ Cook, J. (2013) Ice Age art: arrival of the modern mind, The British Museum, ISBN 978-0-7141-2333-2.

- ^ a b "Copyright Law of the United States of America – Chapter 1 (101. Definitions)". .gov. Archived from the original on 25 December 2017. Retrieved 30 October 2011.

External links

[edit]- ArtLex – online dictionary of visual art terms (archived 24 April 2005)

- Calendar for Artists – calendar listing of visual art festivals.

- Art History Timeline by the Metropolitan Museum of Art.