Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Pro-Europeanism

View on Wikipedia

| This article is part of a series on |

|

|---|

|

|

Pro-Europeanism, sometimes called European Unionism,[1][2] is a political position that favours European integration and membership of the European Union (EU).[3] The opposite of Pro-Europeanism is Euroscepticism.

Political position

[edit]

91–100% 81–90% 71–80% | 61–70% 51–60% |

Pro-Europeans are mostly classified as centrist (Renew Europe) in the context of European politics, including centre-right liberal conservatives (EPP Group) and centre-left social democrats (S&D and Greens/EFA). Pro-Europeanism is ideologically closely related to the European and Global liberal movement.[5][6][7][8]

Pro-Europeans often argue that EU membership has specific benefits for member nations such as that the EU encourages economic prosperity among members, that it promotes peace and stability in member states, that it encourages social progress among member states, that the EU gives countries greater leverage on the world stage compared to countries not in the EU, and that Europeans have shared values and identity. They also argue that these benefits outweigh common criticisms and issues of the EU for member states.[9][10][11]

Pro-EU political parties

[edit]Pan-European level

[edit] EU: Alliance of Liberals and Democrats for Europe Party,[12] European Free Alliance,[13] European Green Party,[14] European People's Party,[12] Party of European Socialists,[12] Volt Europa[15]

EU: Alliance of Liberals and Democrats for Europe Party,[12] European Free Alliance,[13] European Green Party,[14] European People's Party,[12] Party of European Socialists,[12] Volt Europa[15]

Within the EU

[edit] Austria: Austrian People's Party,[16] Social Democratic Party of Austria,[17] NEOS – The New Austria,[18] The Greens – The Green Alternative, Volt Austria

Austria: Austrian People's Party,[16] Social Democratic Party of Austria,[17] NEOS – The New Austria,[18] The Greens – The Green Alternative, Volt Austria Belgium: Reformist Mouvement, Open Flemish Liberals and Democrats,[19] Socialist Party, Vooruit, Christian Democratic and Flemish, Les Engagés, Ecolo, Green, Democratic Federalist Independent, New Flemish Alliance, Volt Belgium

Belgium: Reformist Mouvement, Open Flemish Liberals and Democrats,[19] Socialist Party, Vooruit, Christian Democratic and Flemish, Les Engagés, Ecolo, Green, Democratic Federalist Independent, New Flemish Alliance, Volt Belgium Bulgaria: We Continue the Change, Citizens for European Development of Bulgaria,[20] Yes, Bulgaria!, Democrats for a Strong Bulgaria,[20] Union of Democratic Forces,[21][22][20] Bulgarian Socialist Party (factions),[23][24] Volt Bulgaria, Republicans for Bulgaria,[25] Stand Up.BG, United People's Party, Bulgaria for Citizens Movement, Movement 21

Bulgaria: We Continue the Change, Citizens for European Development of Bulgaria,[20] Yes, Bulgaria!, Democrats for a Strong Bulgaria,[20] Union of Democratic Forces,[21][22][20] Bulgarian Socialist Party (factions),[23][24] Volt Bulgaria, Republicans for Bulgaria,[25] Stand Up.BG, United People's Party, Bulgaria for Citizens Movement, Movement 21 Croatia: Croatian Democratic Union,[26] Social Democratic Party of Croatia, Croatian Peasant Party, Istrian Democratic Assembly, Croatian People's Party – Liberal Democrats, Civic Liberal Alliance, People's Party – Reformists, Croatian Social Liberal Party, Centre

Croatia: Croatian Democratic Union,[26] Social Democratic Party of Croatia, Croatian Peasant Party, Istrian Democratic Assembly, Croatian People's Party – Liberal Democrats, Civic Liberal Alliance, People's Party – Reformists, Croatian Social Liberal Party, Centre Cyprus: Democratic Rally, Democratic Party, EDEK Socialist Party, Democratic Alignment, New Wave – The Other Cyprus, Volt Cyprus

Cyprus: Democratic Rally, Democratic Party, EDEK Socialist Party, Democratic Alignment, New Wave – The Other Cyprus, Volt Cyprus Czech Republic: Mayors and Independents, Czech Pirate Party,[27] KDU-ČSL,[28] TOP 09,[29] Green Party,[30] Social Democracy,[31] Volt Czech Republic

Czech Republic: Mayors and Independents, Czech Pirate Party,[27] KDU-ČSL,[28] TOP 09,[29] Green Party,[30] Social Democracy,[31] Volt Czech Republic Denmark: Social Democrats,[32] Venstre,[33] Conservative People's Party,[34] Danish Social Liberal Party,[35] Moderates, Volt Denmark

Denmark: Social Democrats,[32] Venstre,[33] Conservative People's Party,[34] Danish Social Liberal Party,[35] Moderates, Volt Denmark Estonia: Estonian Reform Party, Estonian Social Democratic Party,[36] Estonia 200, Isamaa, Estonian Greens

Estonia: Estonian Reform Party, Estonian Social Democratic Party,[36] Estonia 200, Isamaa, Estonian Greens Finland: National Coalition Party, Social Democratic Party of Finland, Centre Party, Green League, Swedish People's Party of Finland

Finland: National Coalition Party, Social Democratic Party of Finland, Centre Party, Green League, Swedish People's Party of Finland France: Renaissance, Democratic Movement, The Republicans, Socialist Party, Public Place, Radical Party of the Left, Europe Ecology – The Greens, The New Democrats, Génération.s, Radical Party, Union of Democrats and Independents, New Deal, Agir, En Commun, Horizons, Territories of Progress, Progressive Federation, Centrist Alliance, The Centrists, Ecologist Party, Democratic European Force, Volt France

France: Renaissance, Democratic Movement, The Republicans, Socialist Party, Public Place, Radical Party of the Left, Europe Ecology – The Greens, The New Democrats, Génération.s, Radical Party, Union of Democrats and Independents, New Deal, Agir, En Commun, Horizons, Territories of Progress, Progressive Federation, Centrist Alliance, The Centrists, Ecologist Party, Democratic European Force, Volt France Germany: Christian Democratic Union, Social Democratic Party of Germany, Alliance 90/The Greens, Free Democratic Party, Christian Social Union in Bavaria, Die PARTEI,[37] Volt Germany

Germany: Christian Democratic Union, Social Democratic Party of Germany, Alliance 90/The Greens, Free Democratic Party, Christian Social Union in Bavaria, Die PARTEI,[37] Volt Germany Greece: New Democracy, PASOK – Movement for Change, Syriza, Union of Centrists, Movement of Democratic Socialists, Volt Greece

Greece: New Democracy, PASOK – Movement for Change, Syriza, Union of Centrists, Movement of Democratic Socialists, Volt Greece Hungary: Respect and Freedom Party, Democratic Coalition, Jobbik, Hungarian Socialist Party, Momentum Movement, Dialogue – The Greens' Party, LMP – Hungary's Green Party, Hungarian Liberal Party, New Start

Hungary: Respect and Freedom Party, Democratic Coalition, Jobbik, Hungarian Socialist Party, Momentum Movement, Dialogue – The Greens' Party, LMP – Hungary's Green Party, Hungarian Liberal Party, New Start Ireland: Fianna Fáil, Fine Gael, Labour Party, Social Democrats, Green Party, Volt Ireland

Ireland: Fianna Fáil, Fine Gael, Labour Party, Social Democrats, Green Party, Volt Ireland Italy: Democratic Party, Forza Italia, Italia Viva, Italian Left, More Europe, Volt Italy, Civic Commitment, Action, Italian Socialist Party, Social Democracy, Italian Republican Party, Solidary Democracy, Green Europe, Italian Radicals, Possible, Us of the Centre, Europeanists, Centrists for Europe, Moderates, Article One, European Republicans Movement, Forza Europa, Liberal Democratic Alliance for Italy, Alliance of the Centre, èViva, Sicilian Socialist Party, Team K, Us Moderates

Italy: Democratic Party, Forza Italia, Italia Viva, Italian Left, More Europe, Volt Italy, Civic Commitment, Action, Italian Socialist Party, Social Democracy, Italian Republican Party, Solidary Democracy, Green Europe, Italian Radicals, Possible, Us of the Centre, Europeanists, Centrists for Europe, Moderates, Article One, European Republicans Movement, Forza Europa, Liberal Democratic Alliance for Italy, Alliance of the Centre, èViva, Sicilian Socialist Party, Team K, Us Moderates Latvia: Unity, The Progressives, For Latvia's Development, Movement For!, The Conservatives

Latvia: Unity, The Progressives, For Latvia's Development, Movement For!, The Conservatives Lithuania: Homeland Union, Social Democratic Party of Lithuania, Liberals' Movement, Union of Democrats "For Lithuania", Freedom Party, Lithuanian Green Party

Lithuania: Homeland Union, Social Democratic Party of Lithuania, Liberals' Movement, Union of Democrats "For Lithuania", Freedom Party, Lithuanian Green Party Luxembourg: Christian Social People's Party, Luxembourg Socialist Workers' Party, Democratic Party, The Greens, Volt Luxembourg

Luxembourg: Christian Social People's Party, Luxembourg Socialist Workers' Party, Democratic Party, The Greens, Volt Luxembourg Malta: Nationalist Party, Labour Party (factions), AD+PD, Volt Malta

Malta: Nationalist Party, Labour Party (factions), AD+PD, Volt Malta Netherlands: People's Party for Freedom and Democracy, Labour Party, New Social Contract, Democrats 66, Christian Democratic Appeal, GroenLinks, Volt Netherlands

Netherlands: People's Party for Freedom and Democracy, Labour Party, New Social Contract, Democrats 66, Christian Democratic Appeal, GroenLinks, Volt Netherlands Poland: Civic Platform, Poland 2050, Polish People's Party, New Left, .Modern, Together Party, Your Movement, The Greens, Polish Initiative, Union of European Democrats, Polish Socialist Party[38]

Poland: Civic Platform, Poland 2050, Polish People's Party, New Left, .Modern, Together Party, Your Movement, The Greens, Polish Initiative, Union of European Democrats, Polish Socialist Party[38] Portugal: Social Democratic Party, Socialist Party, Liberal Initiative, LIVRE, People–Animals–Nature Party, Volt Portugal

Portugal: Social Democratic Party, Socialist Party, Liberal Initiative, LIVRE, People–Animals–Nature Party, Volt Portugal Romania: Save Romania Union, National Liberal Party, Social Democratic Party, Democratic Alliance of Hungarians in Romania, People's Movement Party, Health Education Nature Sustainability Party, Renewing Romania's European Project, PRO Romania,[39] Green Party, NOW Party, Volt Romania

Romania: Save Romania Union, National Liberal Party, Social Democratic Party, Democratic Alliance of Hungarians in Romania, People's Movement Party, Health Education Nature Sustainability Party, Renewing Romania's European Project, PRO Romania,[39] Green Party, NOW Party, Volt Romania Slovakia: Progressive Slovakia, Christian Democratic Movement, Slovakia, Democrats, For the People, Voice – Social Democracy, Hungarian Alliance, Volt Slovakia

Slovakia: Progressive Slovakia, Christian Democratic Movement, Slovakia, Democrats, For the People, Voice – Social Democracy, Hungarian Alliance, Volt Slovakia Slovenia: Freedom Movement, Social Democrats,[40] New Slovenia,[41] Democratic Party of Pensioners of Slovenia, Slovenian People's Party[42]

Slovenia: Freedom Movement, Social Democrats,[40] New Slovenia,[41] Democratic Party of Pensioners of Slovenia, Slovenian People's Party[42] Spain: People's Party, Spanish Socialist Workers' Party, Citizens, Volt Spain

Spain: People's Party, Spanish Socialist Workers' Party, Citizens, Volt Spain Sweden: Swedish Social Democratic Party, Moderate Party, Centre Party, Liberals, Christian Democrats, Volt Sweden

Sweden: Swedish Social Democratic Party, Moderate Party, Centre Party, Liberals, Christian Democrats, Volt Sweden

Outside the EU

[edit] Albania: Democratic Party of Albania, Socialist Party of Albania, Freedom Party of Albania, Libra Party, Social Democratic Party of Albania, Republican Party of Albania, Unity for Human Rights Party, Party of the Vlachs of Albania, Volt Albania

Albania: Democratic Party of Albania, Socialist Party of Albania, Freedom Party of Albania, Libra Party, Social Democratic Party of Albania, Republican Party of Albania, Unity for Human Rights Party, Party of the Vlachs of Albania, Volt Albania Armenia: Armenian Democratic Liberal Party, Armenian National Movement Party, Bright Armenia, Christian-Democratic Rebirth Party, Civil Contract, Conservative Party, European Party of Armenia, For The Republic Party, Free Democrats, Heritage, Liberal Democratic Union of Armenia, Meritocratic Party of Armenia, National Progress Party of Armenia, People's Party of Armenia, Republic Party, Rule of Law, Sasna Tsrer Pan-Armenian Party, Social Democrat Hunchakian Party, Sovereign Armenia Party, Union for National Self-Determination

Armenia: Armenian Democratic Liberal Party, Armenian National Movement Party, Bright Armenia, Christian-Democratic Rebirth Party, Civil Contract, Conservative Party, European Party of Armenia, For The Republic Party, Free Democrats, Heritage, Liberal Democratic Union of Armenia, Meritocratic Party of Armenia, National Progress Party of Armenia, People's Party of Armenia, Republic Party, Rule of Law, Sasna Tsrer Pan-Armenian Party, Social Democrat Hunchakian Party, Sovereign Armenia Party, Union for National Self-Determination Belarus: Belarusian Christian Democracy, BPF Party, United Democratic Forces of Belarus, Party of Freedom and Progress, United Civic Party of Belarus, Belarusian Social Democratic Party (Assembly), Belarusian Social Democratic Assembly

Belarus: Belarusian Christian Democracy, BPF Party, United Democratic Forces of Belarus, Party of Freedom and Progress, United Civic Party of Belarus, Belarusian Social Democratic Party (Assembly), Belarusian Social Democratic Assembly Bosnia and Herzegovina: Party of Democratic Action, Croatian Democratic Union of Bosnia and Herzegovina, Social Democratic Party of Bosnia and Herzegovina, Democratic Front, People and Justice, Party of Democratic Progress, Our Party, People's European Union, For New Generations, Union for a Better Future, Independent Bloc

Bosnia and Herzegovina: Party of Democratic Action, Croatian Democratic Union of Bosnia and Herzegovina, Social Democratic Party of Bosnia and Herzegovina, Democratic Front, People and Justice, Party of Democratic Progress, Our Party, People's European Union, For New Generations, Union for a Better Future, Independent Bloc Georgia: United National Movement, Ahali, For Georgia, Lelo, European Georgia, Girchi - More Freedom, Strategy Aghmashenebeli, Republican Party of Georgia, Georgian Labour Party, For the People, Citizens, Droa, Free Democrats, For Justice, Tavisupleba, State for the People, National Democratic Party, Solidarity Alliance of Georgia

Georgia: United National Movement, Ahali, For Georgia, Lelo, European Georgia, Girchi - More Freedom, Strategy Aghmashenebeli, Republican Party of Georgia, Georgian Labour Party, For the People, Citizens, Droa, Free Democrats, For Justice, Tavisupleba, State for the People, National Democratic Party, Solidarity Alliance of Georgia Iceland: Social Democratic Alliance, Liberal Reform Party

Iceland: Social Democratic Alliance, Liberal Reform Party Kazakhstan: Democratic Party of Kazakhstan[43]

Kazakhstan: Democratic Party of Kazakhstan[43] Kosovo: Vetëvendosje, Alliance for the Future of Kosovo,[44] Democratic League of Kosovo, Partia e Fortë

Kosovo: Vetëvendosje, Alliance for the Future of Kosovo,[44] Democratic League of Kosovo, Partia e Fortë Moldova: Party of Action and Solidarity, National Alternative Movement, Liberal Party, European Social Democratic Party, Liberal Democratic Party, European People's Party, Pro Moldova, People's Party of the Republic of Moldova

Moldova: Party of Action and Solidarity, National Alternative Movement, Liberal Party, European Social Democratic Party, Liberal Democratic Party, European People's Party, Pro Moldova, People's Party of the Republic of Moldova Montenegro: Europe Now!, Democratic Party of Socialists of Montenegro, Social Democratic Party of Montenegro, DEMOS, United Reform Action, Democratic Montenegro, Socialist People's Party, Liberal Party, Social Democrats, Bosniak Party, Civis, We won't give up Montenegro

Montenegro: Europe Now!, Democratic Party of Socialists of Montenegro, Social Democratic Party of Montenegro, DEMOS, United Reform Action, Democratic Montenegro, Socialist People's Party, Liberal Party, Social Democrats, Bosniak Party, Civis, We won't give up Montenegro North Macedonia: VMRO-DPMNE, Social Democratic Union, Democratic Union for Integration, New Social Democratic Party, BESA, Alliance for Albanians, Liberal Democratic Party, VMRO-NP

North Macedonia: VMRO-DPMNE, Social Democratic Union, Democratic Union for Integration, New Social Democratic Party, BESA, Alliance for Albanians, Liberal Democratic Party, VMRO-NP Norway: Conservative Party, Labour Party (factions), Liberal Party[45]

Norway: Conservative Party, Labour Party (factions), Liberal Party[45] Russia: Yabloko, People's Freedom Party, Green Alternative, Russia of the Future, Democratic Party of Russia

Russia: Yabloko, People's Freedom Party, Green Alternative, Russia of the Future, Democratic Party of Russia San Marino: Civic 10, Euro-Populars for San Marino, Future Republic, Party of Democrats, Party of Socialists and Democrats,[46] Sammarineses for Freedom, Socialist Party,[47] Union for the Republic[48]

San Marino: Civic 10, Euro-Populars for San Marino, Future Republic, Party of Democrats, Party of Socialists and Democrats,[46] Sammarineses for Freedom, Socialist Party,[47] Union for the Republic[48] Serbia: Democratic Party, Social Democratic Party, Liberal Democratic Party, Movement of Free Citizens, People's Party, New Party, Serbian Progressive Party, Social Democratic Party of Serbia, Party of Freedom and Justice, Together for Serbia, Serbia 21, Civic Democratic Forum, Party of Modern Serbia, Movement for Reversal

Serbia: Democratic Party, Social Democratic Party, Liberal Democratic Party, Movement of Free Citizens, People's Party, New Party, Serbian Progressive Party, Social Democratic Party of Serbia, Party of Freedom and Justice, Together for Serbia, Serbia 21, Civic Democratic Forum, Party of Modern Serbia, Movement for Reversal Switzerland: Social Democratic Party of Switzerland (factions), Green Party of Switzerland (factions), Green Liberal Party of Switzerland, Volt Switzerland

Switzerland: Social Democratic Party of Switzerland (factions), Green Party of Switzerland (factions), Green Liberal Party of Switzerland, Volt Switzerland Turkey: Democracy and Progress Party, Democratic Left Party, Democrat Party, Future Party, Good Party, Homeland Party, Liberal Democratic Party, Peoples' Democratic Party, Peoples' Equality and Democracy Party, Republican People's Party

Turkey: Democracy and Progress Party, Democratic Left Party, Democrat Party, Future Party, Good Party, Homeland Party, Liberal Democratic Party, Peoples' Democratic Party, Peoples' Equality and Democracy Party, Republican People's Party Ukraine: Servant of the People, Fatherland, European Solidarity, Voice, Self Reliance, Ukrainian People's Party, Our Ukraine, European Party of Ukraine, People's Front, Ukrainian Democratic Alliance for Reform, Volt Ukraine

Ukraine: Servant of the People, Fatherland, European Solidarity, Voice, Self Reliance, Ukrainian People's Party, Our Ukraine, European Party of Ukraine, People's Front, Ukrainian Democratic Alliance for Reform, Volt Ukraine United Kingdom: Liberal Democrats,[49][50] Green Party of England and Wales,[51] Scottish National Party (SNP),[52] Social Democratic and Labour Party (SDLP),[53] Scottish Greens,[54] Women's Equality Party,[55] Alliance Party of Northern Ireland,[56] Green Party Northern Ireland,[57] Plaid Cymru, Mebyon Kernow,[58] Alliance EPP: European People's Party UK,[59] Volt UK, Animal Welfare Party[60]

United Kingdom: Liberal Democrats,[49][50] Green Party of England and Wales,[51] Scottish National Party (SNP),[52] Social Democratic and Labour Party (SDLP),[53] Scottish Greens,[54] Women's Equality Party,[55] Alliance Party of Northern Ireland,[56] Green Party Northern Ireland,[57] Plaid Cymru, Mebyon Kernow,[58] Alliance EPP: European People's Party UK,[59] Volt UK, Animal Welfare Party[60]

Pro-EU newspapers and magazines

[edit]Note: Media outside of Europe may also be included.

Denmark: Dagbladet Børsen, Politiken

Denmark: Dagbladet Børsen, Politiken France: Le Figaro,[61][62] Le Monde,[63] Le Parisien

France: Le Figaro,[61][62] Le Monde,[63] Le Parisien Germany: Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung,[64] Der Spiegel, Süddeutsche Zeitung,[64] Der Tagesspiegel

Germany: Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung,[64] Der Spiegel, Süddeutsche Zeitung,[64] Der Tagesspiegel Hungary: Blikk

Hungary: Blikk Ireland: The Irish Times[65]

Ireland: The Irish Times[65] Italy: Corriere della Sera, la Repubblica, La Stampa, Dolomiten

Italy: Corriere della Sera, la Repubblica, La Stampa, Dolomiten Japan: Chunichi Shimbun, Mainichi Shimbun

Japan: Chunichi Shimbun, Mainichi Shimbun Poland: Gazeta Wyborcza, Polityka

Poland: Gazeta Wyborcza, Polityka South Korea: The Hankyoreh[66]

South Korea: The Hankyoreh[66] Spain: El Confidencial, El País, El Mundo

Spain: El Confidencial, El País, El Mundo United Kingdom: Financial Times,[67] The Independent, The Guardian, The New European, The Economist

United Kingdom: Financial Times,[67] The Independent, The Guardian, The New European, The Economist

Multinational European partnerships

[edit]- Council of Europe: an international organization whose stated aim is to uphold human rights, democracy, rule of law in Europe and to promote European culture. It has 46 member states.

- European Political Community: an intergovernmental forum for political and strategic discussions about the future of Europe.

- Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe: the world's largest security-oriented intergovernmental organization, with 57 participating states mostly in Europe and the Northern Hemisphere.

- Paneuropean Union: the oldest European unification movement.

See also

[edit]- Eastern Partnership

- Euromyth

- European Federalist Party

- European Federation

- European Union as an emerging superpower

- Europeanism

- Eurosphere

- Eurovoc

- Euronest Parliamentary Assembly

- Federal Europe

- Federalisation of the European Union

- Liberalism in Europe

- List of European federalist political parties

- Pan-European identity

- Pan-Europeanism

- Politics of Europe

- Potential enlargement of the European Union

- Pulse of Europe Initiative

- Volt Europa

- WhyEurope

References

[edit]- ^ Gowland, David. Britain and the European Union. Taylor & Francis, 2016. p.109

- ^ Sadurski, Wojciech. Spreading Democracy and the Rule of Law?. Springer Science & Business Media, 2006. pp.51, 55

- ^ Krisztina Arató, Petr Kaniok (editors). Euroscepticism and European Integration. Political Science Research Centre Zagreb, 2009. p.40

- ^ "Socio-demographic trends in national public opinion". europarl.europa.eu. October 2023. Retrieved 29 July 2023.

- ^ Almeida, Dimitri (27 April 2012). The Impact of European Integration on Political Parties. Routledge. doi:10.4324/9780203123621. ISBN 978-0-203-12362-1.

- ^ "Emmanuel Macron a Berlin pour se donner une stature européenne". Le Monde. 10 January 2017. Retrieved 2 June 2017.

- ^ Edwards, Maxim (13 December 2018). "Armenia's Revolution Will Not be Monopolized". Foreign Policy.

Bright Armenia is an avowedly pro-EU and classical liberal political party...

- ^ Edward-Isaac Dovere, ed. (20 April 2017). "Obama wades into French election fight". Politico. Retrieved 15 January 2022.

"President Obama appreciated the opportunity to hear from Mr. Macron about his campaign and the important upcoming presidential election in France, a country that President Obama remains deeply committed to as a close ally of the United States, and as a leader on behalf of liberal values in Europe and around the world," Lewis said.

- ^ "Arguments for the European Union". Civitas: Institute for the Study of Civil Society. 18 December 2015. Retrieved 27 May 2025.

- ^ "We need a new pro-Europeanism". Centre for European Reform. Retrieved 27 May 2025.

- ^ "Aims and values | European Union". european-union.europa.eu. Retrieved 27 May 2025.

- ^ a b c Demetriou, Kyriakos (2014). The European Union in Crisis : Explorations in Representation and Democratic Legitimacy. Springer. p. 46. ISBN 9783319087740.

- ^ "Who we are". European Free Alliance. Retrieved 11 February 2023.

The European Free Alliance is a pro-European party that endorses the European Union's values, namely the principles of liberty, democracy, respect for human rights and fundamental freedoms and the rule of law.

- ^ "European Green Party Joins Pro-Europe Network's Ranks". European Greens. Retrieved 11 February 2023.

- ^ "Volt Europa – About us". Volt Europa. Retrieved 2 December 2021.

- ^ "Austrian People's Party (ÖVP)". The Democratic Society. Archived from the original on 6 July 2017. Retrieved 16 December 2015.

- ^ Ton Notermans (January 2001). Social Democracy and Monetary Union. Berghahn Books. p. 203. ISBN 978-1-57181-806-5.

- ^ "Austria's Freedom Party sees vote rise". BBC News. 25 May 2014. Retrieved 25 May 2014.

- ^ Almeida, Dimitri (107). The Impact of European Integration on Political Parties: Beyond the Permissive Consensus. Routledge. p. 107.

- ^ a b c Donatella M. Viola (2015). Routledge Handbook of European Elections. Routledge. p. 639. ISBN 9781317503637. Retrieved 16 December 2015.

- ^ Nathaniel Copsey; Tim Haughton (2009). The JCMS Annual Review of the European Union in 2008. John Wiley & Sons. p. 56. ISBN 9781405189149. Retrieved 16 December 2015.

- ^ Richard Davis Anderson (2001). Postcommunism and the Theory of Democracy. Princeton University Press. p. 147. ISBN 0691089175. Retrieved 16 December 2015.

- ^ "Bulgaria's government will include far-right nationalist parties for the first time – The Washington Post". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on 18 December 2018.

- ^ Tsolova, Tsvetelia (17 March 2017). "Socialists say Bulgaria pays high price for EU's Russia sanctions". Reuters.

- ^ "Цветан Цветанов оглави "Републиканци за България", заместник е Павел Вълнев". bnr.bg.

- ^ "Statut" (PDF). HDZ. Archived from the original (PDF) on 15 December 2017. Retrieved 7 October 2017.

- ^ Předseda Pirátů Bartoš: Nejsme vítači migrantů a jít do vlády se nebojíme. Novinky.cz. Published on 10 September 2017

- ^ "Evropa je prostorem společných hodnot". KDU-ČSL. 10 December 2015. Retrieved 1 October 2017.

- ^ "VOLEBNÍ PROGRAM 2017". TOP09. Retrieved 1 October 2017.

- ^ "Zelení: Evropa musí zahájit jednání o své federalizaci – Strana zelených". Zeliní. 24 June 2016. Archived from the original on 2 October 2017. Retrieved 1 October 2017.

- ^ "Česko by bez pomoci EU mohlo být popelnicí Evropy, míní Chmelař". ČSSD. 28 July 2017. Retrieved 29 September 2017.

- ^ "EU". Social Demokratiet. Retrieved 1 October 2017.

- ^ "Europæisk Samarbejde". Venstre. Retrieved 1 October 2017.

- ^ "EU-Politik – Det Konservative Folkeparti". Det Konservative Folkeparti. Retrieved 1 October 2017.

- ^ Claudia Hefftler; et al. (2015). The Palgrave Handbook of National Parliaments and the European Union. Palgrave Macmillan. p. 286]. ISBN 9781137289131. Retrieved 16 December 2015.

- ^ "Riigikogu 2015 programm". Sotsiaal Demokraadid. 31 July 2017. Retrieved 1 October 2017.

- ^ "EU-Aufklärung im Satire-Kostüm". Deutschlandfunk Kultur. Retrieved 25 April 2019.

- ^ "PPS – Deklaracja ideowa PPS". naszpps.ppspl.eu.

- ^ "Romania – Europe Elects".

- ^ "Program Socialne demokracije" (PDF). Social Democrats (Slovenia). Retrieved 8 October 2017.

- ^ "About". Nova Slovenija. Archived from the original on 9 October 2017. Retrieved 8 October 2017.

- ^ "Temeljna načela SLS". Slovenian People's Party. Retrieved 8 October 2017.

- ^ "We will consider Kazakhstan's accession to the European Union - Peruashev". kaz.orda. Retrieved 29 June 2025.

- ^ "Kosovo: early elections to be held June 8 - Politics". ANSAMed. 8 May 2014.

- ^ Krekling, David Vojislav (27 September 2020). "Venstre går inn for at Norge skal bli medlem i EU". NRK.

- ^ Rtv, San Marino (19 September 2013). "Congresso Psd: si cerca la mediazione su un nome che rappresenti le diverse anime". San Marino Rtv.

- ^ Salvatori, Luca (10 September 2013). "Referendum Europa: il Ps è per il sì". San Marino Rtv.

- ^ Rtv, San Marino (6 September 2013). "Referendum Ue: sì convinto dall'Upr". San Marino Rtv.

- ^ "Protect Britain's place in Europe". Retrieved 29 September 2017.

- ^ Stone, Jon (25 June 2016). "Liberal Democrats pledge to keep Britain in the EU after next election". The Independent. Retrieved 29 September 2017.

- ^ Mason, Rowena (14 March 2016). "Green party 'loud and proud' about backing Britain in Europe". The Guardian. Retrieved 29 September 2017.

- ^ Carrell, Severin (3 March 2016). "Scotland to campaign officially to remain in the EU". The Guardian. Retrieved 29 September 2017.

- ^ McDonnell, Alasdair (10 June 2016). "McDonnell Brexit Address". Social Democratic and Labour Party (SDLP). Retrieved 29 September 2017.

- ^ Greer, Ross (22 February 2016). "Now is the time to fight to stay in Europe ... and to reform it from the left, not the right as Cameron plans". Green Party of Scotland. Retrieved 29 September 2017.

- ^ Walker, Sophie (26 July 2018). "Overconfident men brought us Brexit. It's not too late for women to fix it". The Guardian. Opinion. Retrieved 24 August 2018.

- ^ Hughes, Brendan (22 February 2016). "EU referendum: Where Northern Ireland parties stand". The Irish News. Retrieved 7 October 2017.

- ^ "Green Party Manifesto (2017, Westminster)" (PDF). Green Party Northern Ireland. Archived from the original (PDF) on 27 August 2018. Retrieved 7 October 2017.

- ^ "A reformed Europe – Policies and Manifesto". Mebyon Kernow. Retrieved 7 October 2017.

- ^ "What we believe". UK European People's Party. Retrieved 7 October 2017.

- ^ "Vision". Animal Welfare Party. 16 April 2010. Retrieved 25 November 2020.

- ^ Manuela Caiani, Simona Guerra, ed. (2014). Euroscepticism, Democracy and the Media: Communicating Europe, Contesting Europe. Springer. p. 113.

- ^ John Lloyd, Cristina Marconi, ed. (2014). Reporting the EU: News, Media and the European Institutions. Bloomsbury Publishing. p. 68. ISBN 9780857724595.

In France, the big newspapers remain pro-European, notwithstanding the large success in the polls of the anti-EU movement led by Marine Le Pen – though the main paper of the centre right, Le Figaro, is now more critical.

- ^ Élisabeth Le, ed. (2021). Degrees of European Belonging: The fuzzy areas between us and them. John Benjamins Publishing Company. p. 37. ISBN 9789027260192.

In these circumstances, it is particularly interesting to investigate how the pro-European Le Monde constructs the concept of "Europe" (i.e. who belongs and who does not) ...

- ^ a b Manuela Caiani, Simona Guerra, ed. (2014). Euroscepticism, Democracy and the Media: Communicating Europe, Contesting Europe. Springer. p. 206.

- ^ Oireachtas, Houses of the (22 June 2016). "EU-UK Relations: Statements – Seanad Éireann (25th Seanad) – Wednesday, 22 Jun 2016 – Houses of the Oireachtas". www.oireachtas.ie.

- ^ "[사설] 유럽을 위기로 몰아넣는 영국의 선택" [[editorial] Britain's choice drove Europe into crisis.] (in Korean). The Hankyoreh. 24 June 2016. Retrieved 26 December 2021.

결국 영국은 편협한 안목으로 탈퇴를 선택함으로써 자국을 고립의 길로 이끌고 전 세계에 걱정거리를 안기고 말았다.

[Eventually, Britain chose to go out with a narrow perspective, leading its country to isolation and causing only inconvenience to the world.] - ^ Peter J. Anderson, Tony Weymouth, ed. (2014). Insulting the Public?: The British Press and the European Union. Routledge. p. 103. ISBN 9781317882831.

The Financial Times Having looked at two of the leading pro-European broadsheets, it is time to examine the discourse of the third, and in many ways the most pro-European, that of the Financial Times.

Pro-Europeanism

View on GrokipediaDefinition and Core Concepts

Ideological Foundations

Pro-Europeanism is fundamentally anchored in European federalism, an ideology advocating a supranational federation that pools sovereignty from nation-states to foster lasting peace, economic interdependence, and democratic governance across the continent. This vision posits that national divisions, exacerbated by nationalism and totalitarianism, precipitated conflicts like the World Wars, necessitating a structured unity that balances centralized authority with regional autonomy. Core principles include subsidiarity, whereby decisions are made at the most local effective level, and solidarity, entailing mutual support among diverse communities to address disparities.[9] Federalism distinguishes itself from mere confederation by emphasizing enforceable supranational institutions, such as a bicameral legislature representing both citizens and states, inspired by models like the 1787 U.S. Constitution.[9] Philosophically, these foundations trace to Enlightenment cosmopolitanism, particularly Immanuel Kant's 1795 essay Perpetual Peace, which proposed a "federation of free states" bound by republican constitutions and international law to prevent war through mutual respect for sovereignty and cosmopolitan rights.[10] This evolved into modern applications emphasizing "unity in diversity," where federalism serves as a decentralized mechanism to limit power while enabling collective action, and constitutionalism ensures shared legal frameworks upholding human rights and rule of law.[10] The ideology critiques nationalism as inherently divisive and prone to authoritarianism, extending liberal, democratic, and socialist values beyond national borders to a pan-European scale.[9] A pivotal articulation came in the Ventotene Manifesto of 1941, drafted by Altiero Spinelli and Ernesto Rossi while confined by Fascist authorities on the island of Ventotene. The document diagnosed Europe's crises as stemming from sovereign states' rivalries and urged a "free and united Europe" via federal institutions to dismantle barriers, promote social justice, and avert future dictatorships, laying groundwork for post-war integration efforts.[11] This federalist blueprint intertwined with functionalist approaches, starting with economic cooperation to build political union organically, as later embodied in initiatives like the European Coal and Steel Community.[12] Pro-Europeanism thus synthesizes these strands into a progressive narrative of inevitable integration, often framing the European Union as the institutional realization of Europe's shared destiny, though critics note its elite origins and selective emphasis on supranationalism over national democracies.[13]Distinctions from Related Ideologies

Pro-Europeanism contrasts sharply with Euroscepticism, the latter entailing criticism or outright opposition to supranational integration, often prioritizing national sovereignty over collective decision-making in areas like monetary policy and border controls.[14][15] Pro-Europeans, by contrast, endorse mechanisms such as qualified majority voting in the Council of the EU—introduced via the 1986 Single European Act—to facilitate efficient policymaking, viewing such transfers of competence as essential for addressing transnational challenges like economic interdependence, whereas Eurosceptics decry them as erosions of democratic accountability at the state level.[16] Within the spectrum of integrationist views, pro-Europeanism differs from eurofederalism in its pragmatic flexibility rather than insistence on a sovereign federal superstate akin to the United States. Eurofederalists advocate structural reforms like direct election of a powerful European executive and harmonized fiscal policy to create binding unity, as articulated in initiatives like the 2017 Rome Declaration by federalist groups pushing for treaty changes toward confederation-to-federation evolution.[17] Pro-Europeanism, however, encompasses intergovernmental models where member states retain veto rights in sensitive domains such as foreign policy, reflecting the EU's actual hybrid structure since the 1992 Maastricht Treaty, which balanced supranational elements with national opt-outs.[18] Pro-Europeanism also diverges from Atlanticism by emphasizing endogenous European capabilities over dependence on transatlantic security guarantees. Atlanticism, rooted in post-1945 NATO frameworks, prioritizes U.S.-led alliances for defense—as evidenced by the 1979 dual-track decision on intermediate-range missiles—potentially subordinating EU foreign policy to Washington consensus.[19] In pro-European perspectives, this manifests in advocacy for "strategic autonomy," such as the EU's 2022 Strategic Compass document outlining independent defense procurement and rapid deployment forces by 2025, to mitigate risks from fluctuating U.S. commitments without rejecting NATO complementarity.[20] Distinct from historical pan-Europeanism, which envisioned continent-wide cultural and political solidarity potentially spanning from Lisbon to Vladivostok—as in Richard Coudenhove-Kalergi's 1923 Paneuropa movement—modern pro-Europeanism is institutionally anchored to the EU's 27-member framework, excluding non-integrated states and focusing on legal-economic convergence rather than vague civilizational unity.[1] This delimitation underscores pro-Europeanism's operational emphasis on treaties like the 2009 Lisbon Treaty, which codified differentiated integration speeds via enhanced cooperation clauses, over pan-Europeanism's broader, often non-binding aspirational ideals.[21]Historical Evolution

Pre-20th Century Precursors

Early medieval thinkers laid foundational concepts for supranational European cooperation amid frequent wars and crusading efforts. In 1305–1307, French lawyer Pierre Dubois outlined in De recuperatione Terrae Sanctae a proposal for a permanent council comprising European princes, clergy, and lay representatives to arbitrate disputes, enforce collective decisions, and coordinate military actions, such as crusades against non-Christians; this structure anticipated mechanisms for resolving conflicts without unilateral warfare.[22][23] Similarly, around 1313, Dante Alighieri argued in De Monarchia for a universal secular monarchy under the Holy Roman Emperor to unify Christendom, ensuring peace by subordinating temporal authority to a single ruler independent of papal interference, thereby preventing divisions that fueled strife.[24] In the 15th century, Bohemian King George of Poděbrady advanced practical alliance-building in 1464 through a draft treaty circulated to European sovereigns, envisioning a confederation of Christian states with a permanent assembly for arbitration, mutual defense pacts against external threats like the Ottoman Empire, and penalties for treaty violators enforced by collective embargo or war; though unrealized due to religious tensions, it represented an early multilateral security framework.[25] Enlightenment proposals shifted toward rational, voluntary associations emphasizing balance and republicanism. Charles-Irénée Castel, Abbé de Saint-Pierre, published Projet pour rendre la paix perpétuelle en Europe in 1713, advocating a perpetual confederation of sovereign European states with a continuous diet in a neutral city to maintain power equilibrium, adjudicate quarrels via majority vote, and impose sanctions on aggressors, drawing on post-Utrecht Treaty diplomacy.[26][27] Immanuel Kant refined this in Zum ewigen Frieden (1795), positing that a federation of independent republics—bound by international right rather than coercive empire—would secure perpetual peace through mutual respect for sovereignty, republican constitutions fostering public accountability, and cosmopolitan hospitality reducing interstate hostilities.[28][29] The 19th century saw rhetorical momentum toward federal models inspired by American precedents. Italian nationalist Giuseppe Mazzini promoted a "United States of Europe" in works like Europe: Its Political and Social Problems (1840s onward), envisioning a democratic federation replacing dynastic conflicts with representative assemblies to harmonize nationalities. French writer Victor Hugo popularized the phrase in his August 21, 1849, speech to the Paris International Peace Congress, urging Europe to form a "United States of Europe" as a continental federation embodying liberty and fraternity, transcending borders for collective progress and ending fratricidal wars.[30][31] These visions, though often utopian and unrealized amid nationalism's rise, prefigured 20th-century integration by prioritizing institutional cooperation over conquest.Post-World War II Origins

The end of World War II in Europe on May 8, 1945, left the continent in ruins, with an estimated 40 million dead and economies shattered, prompting leaders to seek mechanisms for lasting peace amid emerging Cold War tensions and the division of Germany.[32] Initial efforts focused on economic reconstruction, such as the U.S.-led Marshall Plan announced in June 1947, which allocated $13 billion in aid primarily to Western European nations to counter Soviet influence and revive industry, fostering early multilateral cooperation through the Organisation for European Economic Co-operation (OEEC) established in April 1948.[32] These steps emphasized interdependence but remained intergovernmental, lacking supranational authority; pro-European advocates, however, pushed for deeper political integration to prevent nationalist revivals, drawing on ideas like Winston Churchill's September 1946 Zurich speech advocating a "United States of Europe" to reconcile France and Germany.[33] A pivotal advancement occurred on May 9, 1950, when French Foreign Minister Robert Schuman, guided by planner Jean Monnet, issued the Schuman Declaration proposing the pooling of French and West German coal and steel production—the sinews of modern warfare—under a supranational High Authority open to other European states, declaring that such integration would make war "not merely unthinkable, but materially impossible."[34][35] This initiative addressed French security concerns over German industrial revival while promoting economic efficiency, reflecting pragmatic realism over idealistic federalism; Monnet, a cognac merchant turned diplomat, had advocated since 1943 for functional integration starting with key sectors to build irreversible unity.[36][37] The proposal culminated in the Treaty of Paris, signed on April 18, 1951, by Belgium, France, West Germany, Italy, Luxembourg, and the Netherlands, establishing the European Coal and Steel Community (ECSC) effective July 23, 1952, with institutions including the High Authority, a Common Assembly, and a Court of Justice to oversee joint management of these resources.[32][38] The ECSC marked the first transfer of sovereignty to a European-level body, driven by elite consensus among leaders like Konrad Adenauer of West Germany, who viewed it as atonement for Nazi aggression and a bulwark against communism, though public support varied amid postwar hardships.[39] This supranational experiment, managing production quotas and trade without veto powers for members, laid the institutional groundwork for pro-Europeanism as a doctrine favoring pooled sovereignty to secure peace and prosperity, influencing subsequent treaties despite initial resistance from figures wary of diluted national control.[40][41]Key Milestones in EU Formation

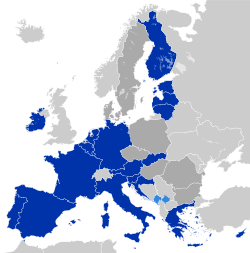

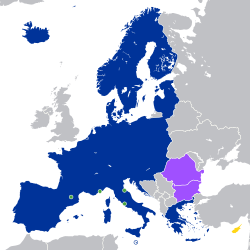

The origins of the European Union lie in post-World War II initiatives to integrate economies and avert future conflicts among former adversaries. On 9 May 1950, French Foreign Minister Robert Schuman issued the Schuman Declaration, proposing a supranational authority to manage French and German production of coal and steel, the essential resources for war-making industries.[42] This initiative culminated in the signing of the Treaty establishing the European Coal and Steel Community (ECSC) on 18 April 1951 by six founding members—Belgium, France, West Germany, Italy, Luxembourg, and the Netherlands—which entered into force on 23 July 1952 and marked the first concrete step toward pooled sovereignty in strategic sectors.[42][43] Building on the ECSC's framework, the Treaties of Rome were signed on 25 March 1957, creating the European Economic Community (EEC) for a common market and customs union, alongside the European Atomic Energy Community (Euratom) to develop peaceful nuclear energy; both took effect on 1 January 1958, expanding integration to trade, agriculture, and transport policies among the six founders.[42][43] The 1965 Merger Treaty, effective from 1 July 1967, consolidated the separate executives of the ECSC, EEC, and Euratom into single institutions—the European Commission and Council of the European Communities—streamlining decision-making.[44] The first enlargement occurred on 1 January 1973, when Denmark, Ireland, and the United Kingdom acceded, increasing membership to nine states and extending the common market northward.[42][44] Further expansions followed: Greece joined on 1 January 1981 as the tenth member, Spain and Portugal on 1 January 1986 as the eleventh and twelfth, respectively.[42] The Single European Act, signed in 1986 and entering force on 1 July 1987, introduced qualified majority voting in the Council and set a deadline for completing the internal market by 1992, accelerating economic unification.[44] A pivotal shift came with the Maastricht Treaty, signed on 7 February 1992 and effective from 1 November 1993, which formally established the European Union (EU), introduced pillars for common foreign and security policy and justice cooperation, and laid groundwork for economic and monetary union including a single currency.[42][43] The third enlargement on 1 January 1995 added Austria, Finland, and Sweden, bringing membership to fifteen.[42] The euro was launched as an electronic currency on 1 January 1999 in eleven states (Greece joined in 2001), with physical notes and coins circulating from 1 January 2002 in twelve countries.[44] Subsequent enlargements dramatically expanded the EU: on 1 May 2004, ten states—Cyprus, Czech Republic, Estonia, Hungary, Latvia, Lithuania, Malta, Poland, Slovakia, and Slovenia—joined, the largest single expansion, incorporating much of Central and Eastern Europe post-Cold War.[42] Bulgaria and Romania acceded on 1 January 2007, followed by Croatia on 1 July 2013, raising membership to 28 (prior to the UK's 2020 departure).[44] The Lisbon Treaty, signed in 2007 and entering force on 1 December 2009, reformed institutions by enhancing the European Parliament's legislative powers, creating a permanent President of the European Council, and strengthening the High Representative for foreign affairs, adapting the EU to enlarged scale and new competencies.[44] These milestones reflect incremental deepening and widening of integration, driven by economic interdependence and geopolitical stability goals.[44]Political and Institutional Expressions

Pro-Integration Political Parties

Pro-integration political parties primarily consist of mainstream center-right, center-left, and liberal formations that advocate transferring additional competences to EU institutions, fostering supranational policies in economic, defense, and foreign affairs domains. These parties, aligned with European Parliament groups such as the European People's Party (EPP), Progressive Alliance of Socialists and Democrats (S&D), Renew Europe, and Greens/European Free Alliance, have historically propelled treaty expansions like the 1992 Maastricht Treaty establishing the euro and the 2009 Lisbon Treaty enhancing qualified majority voting.[45] Their positions stem from convictions that pooled sovereignty yields economic scale advantages and geopolitical leverage, evidenced by intra-EU trade rising from 48% of members' total trade in 1992 to over 60% by 2022. In Germany, the Christian Democratic Union (CDU) and Christian Social Union (CSU) exemplify center-right pro-integrationism, with roots in post-World War II efforts led by Konrad Adenauer to integrate West Germany into supranational structures via the 1951 European Coal and Steel Community. The parties' 2025 coalition agreement with the SPD endorses pathways to common EU defense and political union, including treaty revisions for enhanced capabilities against threats like Russian aggression.[46] Under leader Friedrich Merz, the CDU maintains Atlanticist and pro-EU orientations, prioritizing integration to bolster Germany's export-dependent economy while upholding subsidiarity principles to limit overreach.[47] France's Renaissance (formerly La République En Marche!), established in 2016 by Emmanuel Macron, drives ambitious integration agendas, proposing in Macron's 2017 Sorbonne address a eurozone budget, shared defense fund, and European Monetary Fund to counter global competitors. The party secured 23 seats in the 2019 European Parliament elections and continues advocating fiscal instruments like the 2020 NextGenerationEU recovery fund, which disbursed €750 billion in grants and loans, as mechanisms for convergent growth.[48] Despite critiques of Macron's approach as insufficiently federalist, Renaissance positions emphasize "strategic autonomy" through joint capabilities, such as the 2018 European Intervention Initiative involving nine states.[49] Liberal parties like the Netherlands' Democrats 66 (D66) integrate pro-EU stances into domestic platforms, campaigning for deepened single market rules, climate solidarity via the European Green Deal, and rule-of-law enforcement against backsliding members. D66's 2021 national election manifesto and 2024 European push for stronger EU executive powers reflect empirical arguments for integration to address transboundary challenges like migration and energy security.[50] Similarly, in Spain, S&D-affiliated PSOE under Pedro Sánchez has supported integration tools like the 2022 REPowerEU plan to diversify energy away from Russia, aligning with broader socialist emphases on social convergence.[45] Pan-European outfits such as Volt Europa, launched in 2017, represent explicit federalist advocacy, calling for a EU constitution, directly elected president, and senate to replace the Council, with elected MEPs from Germany (1 seat), Netherlands (1), and others in 2024. Volt's positions prioritize causal mechanisms like uniform taxation to eliminate distortions, drawing on data showing persistent GDP per capita gaps between core and periphery states post-1999 euro adoption.[51] Following the June 2024 European Parliament elections, pro-integration groups sustained dominance with EPP at 188 seats, S&D at 136, Renew at 80, and Greens at 53 out of 720, facilitating majorities for legislation like the 2024 AI Act harmonizing regulations across borders.[52] This configuration underscores their role in countering eurosceptic fringes, though internal variances—such as EPP's emphasis on intergovernmentalism in migration—highlight limits to uniform federal aspirations.[45]Influential Thinkers and Leaders

Jean Monnet, often called the "father of Europe," played a pivotal role in conceptualizing supranational economic cooperation as a means to prevent future wars between France and Germany, drafting the blueprint for the Schuman Plan that proposed pooling coal and steel resources under a common authority.[53] His efforts culminated in the establishment of the European Coal and Steel Community (ECSC) in 1951, the first institutional step toward integration, which he served as the first president of from 1952 to 1955.[54] Monnet later founded the Action Committee for the United States of Europe in 1955 to advocate for deeper political union after setbacks like the failed European Defence Community.[55] Robert Schuman, French Foreign Minister, publicly announced the Schuman Declaration on May 9, 1950, proposing Franco-German production of coal and steel be placed under a supranational High Authority to make war "not merely unthinkable, but materially impossible."[34] This initiative, secretly prepared with Monnet's input, led to the Treaty of Paris in 1951, creating the ECSC with six founding members: France, West Germany, Italy, Belgium, the Netherlands, and Luxembourg.[56] Schuman's functionalist approach emphasized concrete economic achievements over abstract federalism to build trust post-World War II.[57] Konrad Adenauer, West Germany's first Chancellor from 1949 to 1963, championed reconciliation with France through integration, overcoming domestic resistance by framing ECSC membership as essential for regaining sovereignty via Western alliances amid Cold War divisions.[58] He supported the 1957 Treaty of Rome establishing the European Economic Community (EEC), viewing economic interdependence as a bulwark against communism and a path to German rehabilitation in Europe.[59] Adenauer's pragmatic diplomacy, including his 1950 message urging faster integration to counter U.S. criticisms of European disunity, solidified Germany's role in multilateral frameworks.[60] Altiero Spinelli, an Italian federalist intellectual, co-authored the Ventotene Manifesto in 1941 while confined by Fascist authorities, advocating a United States of Europe with a federal constitution to transcend nationalism and imperialism as root causes of totalitarianism and war.[11] The document, smuggled out and circulated post-war, influenced early federalist movements and Spinelli's later parliamentary efforts, including the 1984 Draft Treaty on European Union that proposed direct elections and supranational powers.[12] His vision prioritized political union over mere economic cooperation, critiquing intergovernmentalism as insufficient for lasting peace.[61] Later leaders advanced integration amid evolving challenges. Helmut Kohl, German Chancellor from 1982 to 1998, drove the 1992 Maastricht Treaty, which formalized the European Union, introduced EU citizenship, and laid groundwork for the euro, linking German reunification in 1990 to deeper monetary union with France.[62] Kohl viewed the treaty as essential for stabilizing post-Cold War Europe, stating in 1992 that it signposted "the way ahead" for political and economic unity.[63] Jacques Delors, President of the European Commission from 1985 to 1994, orchestrated the completion of the single market by 1992 via the 1986 Single European Act, removing barriers to goods, services, capital, and people across member states.[64] His tenure advanced the Schengen Area for border-free travel and prepared the euro's framework, emphasizing "ever closer union" through institutional reforms despite opposition from national governments wary of sovereignty loss.[65] Delors' method integrated economic liberalization with social dialogue, fostering growth rates averaging 2.5% annually in the Community during the late 1980s.[66]Multinational Initiatives and Partnerships

The European Movement International, founded on October 25, 1948, following the Hague Congress organized by figures including Winston Churchill, serves as a primary multinational platform coordinating pro-integration efforts across national councils in over 40 countries.[67] It unites civil society groups, employers, trade unions, non-governmental organizations, and political parties to advocate for deeper political, economic, and social European unity grounded in peace, democracy, and solidarity.[67] The organization's activities include lobbying European institutions for policy reforms, such as enhanced democratic accountability in the EU, and hosting events to mobilize public support for integration initiatives like the single market and common foreign policy.[67] The Union of European Federalists (UEF), established in 1946, represents another key multinational entity focused on transforming the EU into a federal union through institutional reforms.[68] Operating via national sections across Europe, the UEF prioritizes comprehensive treaty revisions to centralize fiscal, defense, and foreign policy powers, arguing that such changes would enhance Europe's global sovereignty and crisis response capabilities.[69] Its initiatives encompass campaigns for a directly elected EU executive, youth training programs on federalist principles, and coalitions with parliamentary groups to influence outcomes like the 2022 Conference on the Future of Europe, though critics note limited empirical success in achieving federal structures amid persistent national vetoes.[69][68] Beyond advocacy networks, pro-European partnerships often manifest in targeted intergovernmental frameworks, such as the 1963 Élysée Treaty between France and West Germany, which institutionalized annual summits and military cooperation to underpin broader Community integration.[70] Renewed in 2019 with provisions for joint defense projects, this bilateral pact exemplifies causal linkages between bilateral trust-building and multinational progress, contributing to milestones like the 1992 Maastricht Treaty by fostering habits of consultation that reduced historical animosities. Similar dynamics appear in the Benelux Union's economic coordination since 1944, which prefigured supranational models by harmonizing tariffs and labor mobility among Belgium, the Netherlands, and Luxembourg, influencing the 1957 Treaty of Rome. These initiatives, while advancing specific integrations, face scrutiny for overemphasizing supranationalism at the expense of national parliaments' roles, as evidenced by stalled reforms in UEF-backed proposals where empirical data from EU Council voting records show persistent blocking minorities.[69] Nonetheless, their multinational scope has facilitated cross-border dialogues that empirically correlate with reduced intra-European trade barriers, per World Bank metrics on post-1950s commerce growth.Empirical Support and Public Perception

Economic and Trade Benefits

The European Union's single market and customs union have facilitated tariff-free trade and the free movement of goods, services, capital, and people among member states, thereby reducing transaction costs and enhancing economic efficiency.[71] This framework, established progressively since the 1957 Treaty of Rome and completed with the single market in 1993, eliminates internal customs duties and quantitative restrictions, allowing seamless cross-border commerce that accounts for a significant portion of members' economic activity.[72] Intra-EU trade in goods has expanded substantially, with the value of exports to other member states increasing by more than 9% annually on average between 2002 and 2024, reflecting deepened supply chain integration and market access for exporters.[73] In 2024, intra-EU trade in goods represented a larger share of the bloc's GDP compared to previous years, with goods trade volumes triple those of services, underscoring the customs union's role in amplifying internal commerce over external dependencies.[74] Empirical analyses indicate that such integration has boosted trade intensity gradually across European countries since the mid-20th century, driven by reduced barriers and harmonized regulations.[75] Economic integration has contributed to GDP growth through resource reallocation and productivity gains, as evidenced by panel data regressions showing positive long-term effects on growth rates in integrated economies.[76][77] For instance, the 2004 EU enlargement promoted income convergence and overall expansion by reallocating resources toward higher-productivity sectors, with Central and Eastern European members experiencing faster GDP growth than the pre-enlargement EU average post-accession.[78][79] Studies further quantify that fuller single market implementation could yield up to 9% additional GDP for the EU through barrier removal, though realization depends on addressing persistent regulatory divergences.[80][4]Polling Data and Public Opinion Trends

Public opinion polls indicate sustained support for European integration across EU member states, with recent surveys showing historically high levels of trust in the European Union. The Standard Eurobarometer 102, conducted in autumn 2024, reported that 74% of respondents identified as citizens of the EU, marking the highest figure in over two decades, while trust in the EU reached 47%, up from previous years amid geopolitical challenges.[81] Similarly, a March 2025 Eurobarometer highlighted approval ratings for the EU at record highs, correlating with reduced influence of Eurosceptic parties in national elections.[82] Support for deeper integration manifests in preferences for collective action on security and enlargement. An Institut Delors analysis of a July 2025 Eurobarometer found 81% of EU citizens favoring a common security and defense policy, with opposition at just 15%, reflecting heightened concerns over global instability.[83] On enlargement, 56% expressed favor toward further EU expansion in the latest available surveys, with approval nearing two-thirds among those aged 15-39, indicating generational optimism for integration.[84] Nearly 90% of respondents in a September 2025 Eurobarometer agreed that EU countries must unite more to address global challenges, underscoring instrumental support tied to crisis response.[85] These figures, drawn from EU-commissioned polling, provide standardized empirical measures but warrant caution due to the sponsoring body's stake in positive outcomes, though cross-verification with independent surveys like Pew Research yields comparable trends.[86] Country-level variations reveal pockets of skepticism amid overall positivity. Pew Research Center's 2025 global attitudes survey across 25 countries, including EU members, found a median of 62% holding favorable views of the EU, with increases since 2024 in nations like Germany (+8 percentage points) and stable highs in others such as Poland and Sweden.[86] In contrast, YouGov polling from October 2025 showed lower perceptions of net benefits in France (21% believing EU membership improved their country) and Italy (30%), compared to higher figures elsewhere like the UK (35% post-Brexit reflection).[87] Gallup's March 2025 data across member states indicated stronger approval for EU institutions than national governments in several cases, attributing this to perceived competence in economic and trade domains.[88]| Country/Region | Favorable View of EU (%) | Source and Date |

|---|---|---|

| EU Median (9 members) | 63 | Pew, June 2024[89] |

| EU-Wide Trust | 47 | Eurobarometer 102, Autumn 2024[81] |

| France (net benefit perception) | 21 | YouGov, October 2025[87] |

| Germany (change since 2024) | +8 | Pew, September 2025[86] |

.jpg/250px-Pulse_of_Europe_in_Cologne_2017-04-23_(cropped).jpg)

.jpg/2000px-Pulse_of_Europe_in_Cologne_2017-04-23_(cropped).jpg)