Recent from talks

Contribute something

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Protectionism

View on Wikipedia

| Part of a series on |

| World trade |

|---|

|

| Part of a series on |

| Economic systems |

|---|

|

Major types

|

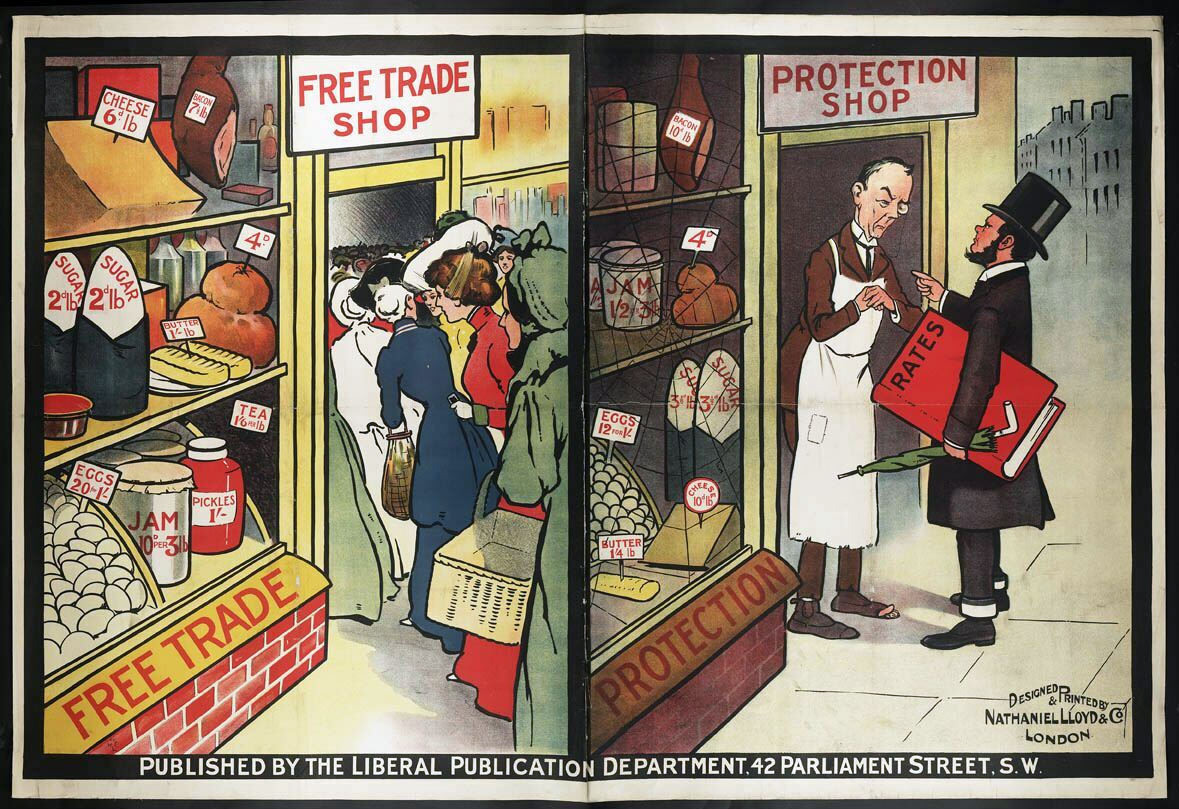

Protectionism, sometimes referred to as trade protectionism, is the economic policy of restricting imports from other countries through methods such as tariffs on imported goods, import quotas, and a variety of other government regulations. Proponents argue that protectionist policies shield the producers, businesses, and workers of the import-competing sector in the country from foreign competitors and raise government revenue. Opponents argue that protectionist policies reduce trade, and adversely affect consumers in general (by raising the cost of imported goods) as well as the producers and workers in export sectors, both in the country implementing protectionist policies and in the countries against which the protections are implemented.[1]

Protectionism has been advocated mainly by parties that hold economic nationalist[a] positions, while economically liberal[b] political parties generally support free trade.[2][3][4][5][6]

There is a consensus among economists that protectionism has a negative effect on economic growth and economic welfare,[7][8][9][10] while free trade and the reduction of trade barriers have a significantly positive effect on economic growth.[8][11][12][13][14][15] Many mainstream economists, such as Douglas Irwin, have implicated protectionism as an important contributing factor in some economic crises, most notably the Great Depression.[16] A more reserved perspective is offered by New Keynesian economist Paul Krugman, who argues that tariffs were not the main cause of the Great Depression but rather a response to it, and that protectionism is a minor source of allocative inefficiency.[17][18] Although trade liberalization can sometimes result in unequally distributed losses and gains, and can, in the short run, cause economic dislocation of workers in import-competing sectors,[19][20] free trade lowers the costs of goods and services for both producers and consumers.[21]

Protectionist policies

[edit]

A variety of policies have been used to achieve protectionist goals. These include:

- Tariffs and import quotas are the most common types of protectionist policies.[22] A tariff is an excise tax levied on imported goods. Originally imposed to raise government revenue, modern tariffs are now used primarily to protect domestic producers and wage rates from lower-priced importers. An import quota is a limit on the volume of a good that may be legally imported, usually established through an import licensing regime.[22]

- Protection of technologies, patents, technical and scientific knowledge[23][24][25]

- Restrictions on foreign direct investment,[26] such as restrictions on the acquisition of domestic firms by foreign investors.[27]

- Administrative barriers: Countries are sometimes accused of using their various administrative rules (e.g., regarding food safety, environmental standards, electrical safety, etc.) as a way to introduce barriers to imports.

- Anti-dumping legislation: "Dumping" is the practice of firms selling to export markets at lower prices than are charged in domestic markets. Supporters of anti-dumping laws argue that they prevent the import of cheaper foreign goods that would cause local firms to close down. However, in practice, anti-dumping laws are usually used to impose trade tariffs on foreign exporters.

- Direct subsidies: Government subsidies (in the form of lump-sum payments or cheap loans) are sometimes given to local firms that cannot compete well against imports. These subsidies are purported to "protect" local jobs and to help local firms adjust to the world markets.

- Export subsidies: Export subsidies are often used by governments to increase exports. Export subsidies have the opposite effect of export tariffs because exporters get payment, which is a percentage or proportion of the value of exported. Export subsidies increase the amount of trade, and in a country with floating exchange rates, have effects similar to import subsidies.

- Exchange rate control: A government may intervene in the foreign exchange market to lower the value of its currency by selling its currency in the foreign exchange market. Doing so will raise the cost of imports and lower the cost of exports, leading to an improvement in its trade balance. However, such a policy is only effective in the short run, as it will lead to higher inflation in the country in the long run, which will, in turn, raise the real cost of exports, and reduce the relative price of imports.

- International patent systems: There is an argument for viewing national patent systems as a cloak for protectionist trade policies at a national level. Two strands of this argument exist: one when patents held by one country form part of a system of exploitable relative advantage in trade negotiations against another, and a second where adhering to a worldwide system of patents confers "good citizenship" status despite 'de facto protectionism'. Peter Drahos explains that "States realized that patent systems could be used to cloak protectionist strategies. There were also reputational advantages for states to be seen to be sticking to intellectual property systems. One could attend the various revisions of the Paris and Berne conventions, participate in the cosmopolitan moral dialogue about the need to protect the fruits of authorial labor and inventive genius...knowing all the while that one's domestic intellectual property system was a handy protectionist weapon."[28]

- Political campaigns advocating domestic consumption (e.g. the "Buy American" campaign in the United States, which could be seen as an extra-legal promotion of protectionism.)

- Preferential governmental spending, such as the Buy American Act, federal legislation which called upon the United States government to prefer US-made products in its purchases.

- Regulations obstructing the importation or sale of articles not made to local standards or barring certain types of promotion.

In the modern trade arena, many other initiatives besides tariffs have been called protectionist. For example, some commentators, such as Jagdish Bhagwati, see developed countries' efforts in imposing their own labor or environmental standards as protectionism. Also, the imposition of restrictive certification procedures on imports is seen in this light.

Further, others point out that free trade agreements often have protectionist provisions such as intellectual property, copyright, and patent restrictions that benefit large corporations. These provisions restrict trade in music, movies, pharmaceuticals, software, and other manufactured items to high-cost producers with quotas from low-cost producers set to zero.[29]

Impact

[edit]There is a broad consensus among economists that protectionism has a negative effect on economic growth and economic welfare, while free trade and the reduction of trade barriers has a positive effect on economic growth.[11][12][13][8][30][31][32] However, protectionism can be used to raise government revenue and enable access to intellectual property, including essential medicines.[33]

Protectionism is frequently criticized by economists as harming the people it is intended to help. Mainstream economists instead support free trade.[34][35] The principle of comparative advantage shows that the gains from free trade outweigh any losses as free trade creates more jobs than it destroys because it allows countries to specialize in the production of goods and services in which they have a comparative advantage.[36] Protectionism results in deadweight loss; this loss to overall welfare gives no-one any benefit, unlike in a free market (without trade barriers), where there is no such total loss. Economist Stephen P. Magee claims the benefits of free trade outweigh the losses by as much as 100 to 1.[37]

Economic impact

[edit]Living standards

[edit]A 2016 study found that "trade typically favors the poor", as they spend a greater share of their earnings on goods, as free trade reduces the costs of goods.[38] Other research found that China's entry to the WTO benefited US consumers, as the price of Chinese goods were substantially reduced.[39] Harvard economist Dani Rodrik argues that while globalization and free trade does contribute to social problems, "a serious retreat into protectionism would hurt the many groups that benefit from trade and would result in the same kind of social conflicts that globalization itself generates. We have to recognize that erecting trade barriers will help in only a limited set of circumstances and that trade policy will rarely be the best response to the problems [of globalization]".[40]

Growth

[edit]An empirical study by Furceri et al. (2019) concluded that protectionist measures like tariff increases have a significant adverse impact on domestic output and productivity.[41] A prominent 1999 study by Jeffrey A. Frankel and David H. Romer found while controlling for relevant factors, that free trade does have a positive impact on growth and incomes. The effect is quantitatively large and statistically significant.[42]

Economist Arvind Panagariya criticizes the view that protectionism is good for growth. Such arguments, according to him, arise from "revisionist interpretation" of East Asian "tigers"' economic history. The Asian tigers achieved a rapid increase in per capita income without any "redistributive social programs", through free trade, which advanced Western economies took a century to achieve.[32][43]

According to economic historians Findlay and O'Rourke, there is a consensus in the economics literature that protectionist policies in the interwar period "hurt the world economy overall, although there is a debate about whether the effect was large or small."[44]

According to Dartmouth economist Douglas Irwin, "that there is a correlation between high tariffs and growth in the late nineteenth century cannot be denied. But correlation is not causation... there is no reason for necessarily thinking that import protection was a good policy just because the economic outcome was good: the outcome could have been driven by factors completely unrelated to the tariff, or perhaps could have been even better in the absence of protection."[45] Irwin furthermore writes that "few observers have argued outright that the high tariffs caused such growth."[45]

One study by the economic historian Brian Varian found no correlation between tariffs and growth among the Australian colonies in the late nineteenth century, a time when each of the colonies had the independence to set their own tariffs.[46]

According to Oxford economic historian Kevin O'Rourke, "It seems clear that protection was important for the growth of US manufacturing in the first half of the 19th century; but this does not necessarily imply that the tariff was beneficial for GDP growth. Protectionists have often pointed to German and American industrialization during this period as evidence in favor of their position, but economic growth is influenced by many factors other than trade policy, and it is important to control for these when assessing the links between tariffs and growth."[47]

Developing world

[edit]There is broad consensus among economists that free trade helps workers in developing countries, even though they are not subject to the stringent health and labor standards of developed countries. This is because "the growth of manufacturing—and of the myriad other jobs that the new export sector creates—has a ripple effect throughout the economy" that creates competition among producers, lifting wages and living conditions.[48] The Nobel laureates Milton Friedman and Paul Krugman have argued for free trade as a model for economic development.[11] Alan Greenspan, former chair of the American Federal Reserve, has criticized protectionist proposals as leading "to an atrophy of our competitive ability. ... If the protectionist route is followed, newer, more efficient industries will have less scope to expand, and overall output and economic welfare will suffer."[49]

Protectionists postulate that new industries may require protection from entrenched foreign competition in order to develop. Mainstream economists do concede that tariffs can in the short-term help domestic industries to develop but are contingent on the short-term nature of the protective tariffs and the ability of the government to pick the winners.[50][51] The problems are that protective tariffs will not be reduced after the infant industry reaches a foothold, and that governments will not pick industries that are likely to succeed.[51] Economists have identified a number of cases across different countries and industries where attempts to shelter infant industries failed.[52][53][54][55][56]

Intellectual property

[edit]The Agreement on Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights (TRIPS) is an international legal agreement between all the member nations of the World Trade Organization (WTO). It establishes minimum standards for the regulation by national governments of different forms of intellectual property (IP) as applied to nationals of other WTO member nations.[57] TRIPS was negotiated at the end of the Uruguay Round of the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT)[c] between 1989 and 1990[58] and is administered by the WTO. Statements by the World Bank indicate that TRIPS has not led to a demonstrable acceleration of investment to low-income countries, though it may have done so for middle-income countries.[20]

Critics argue that TRIPS limits the ability of governments to introduce competition for generic producers.[59] The TRIPS agreement allows the grant of compulsory licenses at a nation's discretion. TRIPS-plus conditions in the United States' FTAs with Australia, Jordan, Singapore and Vietnam have restricted the application of compulsory licenses to emergency situations, antitrust remedies, and cases of public non-commercial use.[59]

Access to essential medicines

[edit]One of the most visible conflicts over TRIPS has been AIDS drugs in Africa. Despite the role that patents have played in maintaining higher drug costs for public health programs across Africa, this controversy has not led to a revision of TRIPS. Instead, an interpretive statement, the Doha Declaration, was issued in November 2001, which indicated that TRIPS should not prevent states from dealing with public health crises and allowed for compulsory licenses. After Doha, PhRMA, the United States and to a lesser extent other developed nations began working to minimize the effect of the declaration.[60]

In 2020, conflicts re-emerged over patents, copyrights and trade secrets related to COVID-19 vaccines, diagnostics and treatments. South Africa and India proposed that WTO grant a temporary waiver to enable more widespread production of the vaccines, since suppressing the virus as quickly as possible benefits the entire world.[61][62] The waivers would be in addition to the existing, but cumbersome, flexibilities in TRIPS allowing countries to impose compulsory licenses.[63][64] Over 100 developing nations supported the waiver but it was blocked by the G7 members.[65] This blocking was condemned by 400 organizations including Doctors Without Borders and 115 members of the European Parliament.[66] In June 2022, after extensive involvement of the European Union, the WTO instead adopted a watered-down agreement that focuses only on vaccine patents, excludes high-income countries and China, and contains few provisions that are not covered by existing flexibilities.[67][68]

Armed conflicts

[edit]

Protectionism has been attributed as a major cause of war. Proponents of this theory point to the constant warfare in the 17th and 18th centuries among European countries whose governments were predominantly mercantilist and protectionist, the American Revolution, which came about ostensibly due to British tariffs and taxes. According to a slogan of Frédéric Bastiat (1801–1850), "When goods cannot cross borders, armies will."[69]

On the other hand, archaeologist Lawrence H. Keeley argues in his book War Before Civilization that disputes between trading partners escalate to war more frequently than disputes between nations that don't trade much with each other.[70] The Opium Wars were fought between the UK[d] and China over the right of British merchants to engage in the free trade of opium. For many opium users, what started as recreation soon became a punishing addiction: many people who stopped ingesting opium suffered chills, nausea, and cramps, and sometimes died from withdrawal. Once addicted, people would often do almost anything to continue to get access to the drug.[71]

Barbara Tuchman says both European intellectuals and leaders overestimated the power of free trade on the eve of World War I. They believed that the interconnectedness of European nations through trade would stop a continent-wide war from breaking out, as the economic consequences would be too great. However, the assumption proved incorrect. For example, Tuchman noted that Helmuth von Moltke the Younger, when warned of such consequences, refused to even consider them in his plans, arguing he was a "soldier", not an "economist".[72]

History

[edit]

In the 18th century, Adam Smith famously warned against the "interested sophistry" of industry, seeking to gain an advantage at the cost of the consumers.[34] Friedrich List saw Adam Smith's views on free trade as disingenuous, believing that Smith advocated for free trade so that British industry could lock out underdeveloped foreign competition.[73]

According to economic historians Douglas Irwin and Kevin O'Rourke, "shocks that emanate from brief financial crises tend to be transitory and have a little long-run effect on trade policy, whereas those that play out over longer periods (the early 1890s, early 1930s) may give rise to protectionism that is difficult to reverse. Regional wars also produce transitory shocks that have little impact on long-run trade policy, while global wars give rise to extensive government trade restrictions that can be difficult to reverse."[74]

One study shows that sudden shifts in comparative advantage for specific countries have led some countries to become protectionist: "The shift in comparative advantage associated with the opening up of New World frontiers, and the subsequent "grain invasion" of Europe, led to higher agricultural tariffs from the late 1870s onwards, which as we have seen reversed the move toward freer trade that had characterized mid-nineteenth-century Europe. In the decades after World War II, Japan's rapid rise led to trade friction with other countries. Japan's recovery was accompanied by a sharp increase in its exports of certain product categories: cotton textiles in the 1950s, steel in the 1960s, automobiles in the 1970s, and electronics in the 1980s. In each case, the rapid expansion in Japan's exports created difficulties for its trading partners and the use of protectionism as a shock absorber."[74]

China

[edit]In 2010, Paul Krugman wrote that China pursues a mercantilist and predatory policy, i.e., it keeps its currency undervalued to accumulate trade surpluses by using capital flow controls. The Chinese government sells renminbi and buys foreign currency to keep the renminbi low, giving the Chinese manufacturing sector a cost advantage over its competitors. China's surpluses drain US demand and slow economic recovery in other countries with which China trades. Krugman writes: "This is the most distorted exchange rate policy any great nation has ever followed". He notes that an undervalued renminbi is tantamount to imposing high tariffs or providing export subsidies. A cheaper currency improves employment and competitiveness because it makes imports more expensive while making domestic products more attractive. He expects Chinese surpluses to destroy 1.4 million American jobs by 2011.[75][76][77][78][79][80] [81][82][83]

In June 2015, the international community, through the IMF, rejected this notion and assessed the renminbi as suggested to be no longer undervalued.[84]

Later that year, American economist Charles Calomiris wrote that US presidential candidate at the time Donald Trump had falsely characterized the trajectory of the renminbi's exchange rate in nominal terms and especially so when using the real exchange rate, and that a recent devaluation by the PBC was a passive one where inaction would've led to an even steeper devaluation by market forces, understandably so after the disappearance of "a lot of [Chinese economic growth] low-hanging fruit that was easily picked in the 1980s, 1990s, and 2000s."[85]

Europe

[edit]Continental Europe

[edit]Europe became increasingly protectionist during the eighteenth century.[44] Economic historians Findlay and O'Rourke write that in "the immediate aftermath of the Napoleonic Wars, European trade policies were almost universally protectionist", with the exceptions being smaller countries such as the Netherlands and Denmark.[44]

Europe increasingly liberalized its trade during the 19th century.[86] Countries such as the Netherlands, Denmark, Portugal and Switzerland, and arguably Sweden and Belgium, had fully moved towards free trade prior to 1860.[86] Economic historians see the repeal of the Corn Laws in 1846 as the decisive shift toward free trade in Britain.[86][87] A 1990 study by the Harvard economic historian Jeffrey Williamson showed that the Corn Laws (which imposed restrictions and tariffs on imported grain) substantially increased the cost of living for British workers, and hampered the British manufacturing sector by reducing the disposable incomes that British workers could have spent on manufactured goods.[88] The shift towards liberalization in Britain occurred in part due to "the influence of economists like David Ricardo", but also due to "the growing power of urban interests".[86]

Findlay and O'Rourke characterize 1860 Cobden Chevalier treaty between France and the United Kingdom as "a decisive shift toward European free trade."[86] This treaty was followed by numerous free trade agreements: "France and Belgium signed a treaty in 1861; a Franco-Prussian treaty was signed in 1862; Italy entered the "network of Cobden-Chevalier treaties" in 1863 (Bairoch 1989, 40); Switzerland in 1864; Sweden, Norway, Spain, the Netherlands, and the Hanseatic towns in 1865; and Austria in 1866. By 1877, less than two decades after the Cobden Chevalier treaty and three decades after British Repeal, Germany "had virtually become a free trade country" (Bairoch, 41). Average duties on manufactured products had declined to 9–12% on the Continent, a far cry from the 50% British tariffs, and numerous prohibitions elsewhere, of the immediate post-Waterloo era (Bairoch, table 3, p. 6, and table 5, p. 42)."[86]

Some European powers did not liberalize during the 19th century, such as the Russian Empire and Austro-Hungarian Empire which remained highly protectionist. The Ottoman Empire also became increasingly protectionist.[89] In the Ottoman Empire's case, however, it previously had liberal free trade policies during the 18th to early 19th centuries.[90]

The countries of Western Europe began to steadily liberalize their economies after World War II and the protectionism of the interwar period,[44] but John Tsang, then Hong Kong's Secretary for Commerce, Industry and Technology and chair of the Sixth Ministerial Conference of the World Trade Organization, MC6, commented in 2005 that the EU spent around €70 billion per year on "trade-distorting support".[91]

United Kingdom

[edit]| This article is part of a series on |

| Conservatism in the United Kingdom |

|---|

|

Britain became one of the most prosperous economic regions in the world between the late 17th century and the early 19th century as a result of being the birthplace of the Industrial Revolution that began in the mid-eighteenth century.[92] Successive British government protected Britain's merchants using trade regulations, barriers and subsidies to domestic industries in order to maximise exports from and minimise imports to Britain. The Navigation Acts of the late 17th century required all trade in England and its colonies to be conducted with English-flagged ships with at least 75% of their crews being English subjects.[93]

The Navigation Acts also prohibited British colonies from exporting certain products to countries other than Britain along with mandating that imports be sourced only through Britain. The colonies were forbidden to trade directly with other nations or rival empires with the intention of maintaining them as dependent agricultural economies geared towards producing raw materials for export to Britain. The growth of native industries in the colonies were discouraged in order to keep them dependent on the metropole for finished goods.[94][95] From 1815 to 1870, the United Kingdom reaped the benefits of being the world's first modern, industrialised nation. It became known as "the workshop of the world", with British finished goods being produced so efficiently and cheaply that they could often undersell comparable, locally manufactured goods in almost any other market.[96]

By the 1840s, the United Kingdom had adopted a free-trade policy, meaning open markets and no tariffs throughout the empire.[97] The Corn Laws were tariffs and other trade restrictions on imported food and corn enforced in the United Kingdom between 1815 and 1846, and enhanced the profits and political power associated with land ownership. The laws raised food prices and the costs of living for the British public, and hampered the growth of other British economic sectors, such as manufacturing, by reducing the disposable income of the British public.[98] The Prime Minister, Sir Robert Peel, a Conservative, achieved repeal in 1846 with the support of the Whigs in Parliament, overcoming the opposition of most of his own party.

While the United Kingdom espoused a policy of free trade in the late nineteenth century, it was hardly the case that Britain was unaffected by the tariffs imposed by its trade partners—tariffs that generally increased during the late nineteenth century.[99] According to one study, Britain's exports in 1902 would have been 57% higher, if all of Britain's trade partners also embraced free trade.[100] The decline in overseas demand for British exports, resulting from foreign tariffs, contributed to the so-called late-Victorian climacteric in the British economy: a decline in the growth rate, i.e. a deceleration.[101][102]

During the interwar era, Britain abandoned free trade. There was a limited erosion of free trade during the 1920s under a patchwork of legislation including the Safeguarding of Industries Act of 1921, the Safeguarding of Industries Act of 1925, and the Finance Act of 1925. The McKenna Duties, which were imposed during the First World War on motorcars; clocks and watches; musical instruments; and cinematographic film were retained.[103] Under commodities that were early to receive protection included matches, chemicals, scientific equipment, silk, rayon, embroidery, lace, cutlery, gloves, incandescent mantles, paper, pottery, enamelled holloware, and buttons.[104] The duties on motorcars and rayon have been determined to have expanded output considerably.[105][106] Amid the Depression, Britain passed the Import Duties Act of 1932, which imposed a general tariff of 10% on most imports and created the Import Duties Advisory Committee (IDAC), which could recommend even higher duties.[107] Britain's protectionism in the early 1930s was shown by Lloyd and Solomou to have been productivity-enhancing.[108]

The possessions of the East India Company in India, known as British India, was the centrepiece of the British Empire, and because of an efficient taxation system it paid its own administrative expenses as well as the cost of the large British Indian Army. In terms of trade, India turned only a small profit for British business.[109] However, transfers to the British government was massive: in 1801 unrequited (unpaid, or paid from Indian-collected revenue) was about 30% of British domestic savings available for capital formation in the United Kingdom.[110][111]

Latin America

[edit]Most Latin American countries gained independence in the early 19th century, with notable exceptions including Spanish Cuba and Spanish Puerto Rico. Following the achievement of their independence, many of the Latin American countries adopted protectionism. They both feared that any foreign competition would stomp out their newly created state and believed that lack of outside resources would drive domestic production.[112] The protectionist behavior continued up until and during the World Wars. During World War 2, Latin America had, on average, the highest tariffs in the world.[113][114]

Argentina

[edit]Argentina, which had been insignificant during the first half of the 19th century, showed an impressive and sustained economic performance from the 1860s up until 1930. A 2018 study describes Argentina as a "super-exporter" during the period 1880–1929, and credits the boom to low trade costs and trade liberalization on one hand and on the other hand to the fact that Argentina "offered a diverse basket of products to the different European and American countries that consumed them". The study concludes "that Argentina took advantage of a multilateral and open economic system."[115]

Beginning in the 1940s, Juan Perón erected a system of almost complete protectionism against imports, largely cutting off Argentina from the international market. Protectionism created a domestically oriented industry with high production costs, incapable of competing in international markets. At the same time, output of beef and grain, the country's main export goods, stagnated.[116] The IAPI began shortchanging growers and, when world grain prices dropped in the late 1940s, it stifled agricultural production, exports and business sentiment, in general.[117] During this period Argentina's economy continued to grow, on average, but more slowly than the world as a whole or than its neighbors, Brazil and Chile. By 1954, while still leading the region, Argentina's GDP per capita had fallen to less than half of that of the United States, from being 80% equivalent before the 1930s.[118][119]

United States

[edit]

According to Douglas Irwin, tariffs have historically served three main purposes: generating revenue for the federal government, restricting imports to protect domestic producers, and securing reciprocity through trade agreements that reduce barriers. The history of U.S. trade policy can be divided into three distinct eras, each characterized by the predominance of one goal. From 1790 to 1860, revenue considerations dominated, as import duties accounted for approximately 90% of federal government receipts. From 1861 to 1933, the growing reliance on domestic taxation shifted the focus of tariffs toward protecting domestic industries. From 1934 to 2016, the primary objective of trade policy became the negotiation of trade agreements with other countries. The three eras of U.S. tariff history were separated by two major shocks—the Civil War and the Great Depression—that realigned political power and shifted trade policy objectives.[120]

Political support by members of Congress often reflects the economic interests of producers rather than consumers, as producers tend to be better organized politically and employ many voting workers. Trade-related interests differ across industries, depending on whether they focus on exports or face import competition. In general, workers in export-oriented sectors favor lower tariffs, while those in import-competing industries support higher tariffs.[120]

Because congressional representation is geographically based, regional economic interests tend to shape consistent voting patterns over time. For much of U.S. history, the primary division over trade policy has been along the North–South axis. In the early 19th century, a manufacturing corridor developed in the Northeast, including textile production in New England and iron industries in Pennsylvania and Ohio, which often faced import competition. By contrast, the South specialized in agricultural exports such as cotton and tobacco.[120]

In more recent times, representatives from the Rust Belt—spanning from Upstate New York through the industrial Midwest—have often opposed trade agreements, while those from the South and the West have generally supported them. The regional variation in trade-related interests implies that political parties may adopt opposing positions on trade policy when their electoral bases differ geographically. Each of the three trade policy eras—focused respectively on revenue, restriction, and reciprocity—occurred during periods of political dominance by a single party able to implement its preferred policies.[120]

Colonial period

[edit]Trade policy was a subject of controversy even prior to the independence of the United States. The thirteen North American colonies were subject to the restrictive framework of the Navigation Acts, which directed most colonial trade through Britain. Approximately three-quarters of colonial exports were enumerated goods that had to pass through a British port before being reexported elsewhere, a policy that reduced the prices received by American planters.[120]

Historians have debated whether British mercantilist policies harmed American colonial interests and fueled the American Revolution. Harper estimated that trade restrictions cost the colonies about 2.3% of their income in 1773, though this excluded benefits of empire, such as defense and lower shipping insurance.[121] The economic burden of the Navigation Acts fell mostly on the southern colonies, especially tobacco planters in Maryland and Virginia, potentially reducing regional income by up to 2.5% and strengthening support for independence. American foreign trade declined sharply during the Revolutionary War and remained subdued into the 1780s. Trade revived during the 1790s but remained volatile due to ongoing military conflicts in Europe.[120]

Revenue period (1790–1860)

[edit]Beginning in 1790, the newly established federal government adopted tariffs as its primary source of revenue. There was a consensus among the Founding Fathers that tariffs were the most efficient way of raising public funds as well as the most politically acceptable. Early sales taxes in the post-colonial period were highly controversial, difficult to enforce, and costly to administer. This was evident during events like the Whiskey Rebellion, where the enforcement of sales taxes led to significant resistance. Similarly, an income tax did not make sense for numerous reasons, particularly due to the complexities of tracking and collecting it. In contrast, tariffs were a simpler solution. Imports entered the United States primarily through a limited number of ports, such as Boston, New York City, Philadelphia, Baltimore, and Charleston, South Carolina. This concentration of imports made it easier to impose taxes directly at these points, streamlining the process of collection. Furthermore, tariffs were less visible to the general public because they were built into the price of goods, reducing political resistance. The system allowed for efficient revenue generation without the immediate visibility or perceived burden of other tax forms, contributing to its political acceptability among the Founders.[122]

President Thomas Jefferson initiated a notable policy experiment by enacting a complete embargo on maritime commerce, with Congressional support, beginning in December 1807. The stated objective of the embargo was to protect American vessels and sailors from becoming entangled in the Anglo-French naval conflict (the Napoleonic Wars). By mid-1808, the United States had reached near-autarkic conditions, representing one of the most extreme peacetime interruptions of international trade in its history. The embargo, which remained in effect from December 1807 to March 1809, imposed significant economic costs.[120] Irwin (2005) estimates that the static welfare loss associated with the embargo was approximately 5% of GDP.[123]

From 1837 to 1860, spanning the Second Party System and ending with the Civil War, the Democratic Party held political dominance in the United States. The Democrats drew support primarily from the export-oriented South and promoted the slogan "a tariff for revenue only" to express their opposition to protective tariffs. As a result, the average tariff declined from early 1830s levels to under 20% by 1860. During this period, there were 12 sessions of Congress: 7 under unified government (6 led by Democrats, 1 by Whigs) and 5 under divided control. This meant that over the 34-year span, the pro-tariff Whig Party, based in the North, held power for only two years. They succeeded in raising tariffs in 1842, but this was reversed in 1846 after Democrats returned to power. Throughout the 10 years of divided government, tariff policy remained unchanged.[120]

Civil War (1861–1865)

[edit]Some non-academic commentators have argued that trade restrictions were a major factor in the South's decision to secede during the Civil War, although this view is not widely supported among academic historians. After the 1828 Tariff of Abominations, South Carolina threatened secession, but the crisis was resolved through the Compromise of 1833, which led to a steady decline in tariffs. Further reductions followed in 1846 and 1857, bringing the average tariff below 20% on the eve of the war—one of the lowest levels in the antebellum period. Irwin notes that Southern Democrats had substantial influence over trade policy until the Civil War. He rejects the revisionist claim—often associated with the Lost Cause narrative—that the Morrill Tariff triggered the conflict. Instead, Irwin argues that the Morrill Tariff only passed because Southern states had already seceded and their representatives were no longer in Congress to oppose it. It was signed by President James Buchanan, a Democrat, before Lincoln took office. In short, Irwin finds no evidence that tariffs were a major cause of the Civil War.[122]

Restriction period (1866–1928)

[edit]The Civil War shifted political power from the South to the North, benefiting the Republican Party, which favored protective tariffs. As a result, trade policy focused more on restriction than revenue, and average tariffs increased. From 1861 to 1932, the Republicans dominated American politics and drew their political support from the North, where manufacturing interests were concentrated. Republicans supported high tariffs to limit imports, leading to rates rising to 40–50% during the Civil War and remaining at that level for several decades. During this time, there were 35 sessions of Congress, including 21 under unified government (17 Republican, 4 Democratic) and 14 under divided control. Over the span of 72 years, Democrats succeeded in reducing tariffs only twice, in 1894 and 1913, but both efforts were swiftly reversed when Republicans regained power. Although trade policy was often contested, it remained relatively stable due to prolonged one-party dominance and institutional barriers to change.[120]

According to Irwin, a common myth about U.S. trade policy is that high tariffs made the United States into a great industrial power in the late 19th century. As its share of global manufacturing powered from 23% in 1870 to 36% in 1913, the admittedly high tariffs of the time came with a cost, estimated at around 0.5% of GDP in the mid-1870s. In some industries, they might have sped up development by a few years. U.S. economic growth during its protectionist era was driven more by its abundant natural resources and openness to people and ideas, including large-scale immigration, foreign capital, and imported technologies. While tariffs on manufactured goods were high, the country remained open in other respects, and much of the economic growth occurred in services such as railroads and telecommunications rather than in manufacturing, which had already expanded significantly before the Civil War when tariffs were lower.[124][125]

Great Depression and Smoot–Hawley Tariff (1929–1933)

[edit]The Tariff Act of 1930, commonly known as the Smoot–Hawley Tariff, is considered one of the most controversial tariff laws ever enacted by the United States Congress. The act raised the average tariff on dutiable imports from approximately 40% to 47%, though price deflation during the Great Depression caused the effective rate to rise to nearly 60% by 1932. The Smoot–Hawley Tariff was implemented as the global economy was entering a severe downturn. The Great Depression of 1929–1933 represented an economic collapse for both the United States—where real GDP declined by about 25% and unemployment exceeded 20%—and much of the world. As international trade contracted, trade barriers multiplied, unemployment increased, and industrial output declined worldwide, leading many to attribute part of the global economic crisis to the Smoot–Hawley Tariff. The extent to which this legislation contributed to the depth of the Great Depression has remained a subject of ongoing debate.[120]

Irwin argues that while the Smoot-Hawley Tariff Act was not the primary cause of the Great Depression, it contributed to its severity by provoking international retaliation and reducing global trade. What mitigated the impact of Smoot-Hawley was the small size of the trade sector at the time. Only a third of total imports to the United States in 1930 were subject to duties, and those dutiable imports represented only 1.4 percent of GDP. According to Irwin, there is no evidence that the legislation achieved its goals of net job creation or economic recovery. Even from a Keynesian perspective, the policy was counterproductive, as the decline in exports exceeded the reduction in imports. While falling foreign incomes were a key factor in the collapse of U.S. exports, the tariff also limited foreign access to U.S. dollars, appreciating the currency and making American goods less competitive abroad. Irwin emphasizes that one of the most damaging consequences of the Act was the deterioration of the United States' trade relations with key partners. Enacted at a time when the League of Nations was seeking to implement a global "tariff truce", the Smoot-Hawley Tariff was widely perceived as a unilateral and hostile move, undermining international cooperation. In his assessment, the most significant long-term impact was that the resentment it generated encouraged other countries to form discriminatory trading blocs. These preferential arrangements, diverted trade away from the United States and hindered the global economic recovery.[126][127]

A more cautious view is represented by the New Keynesian economist Paul Krugman, who argues that tariffs were not the primary cause of the Great Depression but rather a response to it, and that protectionism constitutes only a limited source of allocative inefficiency.[128][129] Other economists have contended that the record tariffs of the 1920s and early 1930s exacerbated the Great Depression in the U.S., in part because of retaliatory tariffs imposed by other countries on the United States.[130][131][132]

Reciprocity period (1934–2016)

[edit]The Great Depression led to a political realignment following the Democratic victory in the 1932 election. This election ended decades of Republican dominance and initiated a period of Democratic control over the federal government that lasted from 1933 to 1993. The realignment shifted influence toward the party that prioritized export-oriented interests in the South. Consequently, the focus of trade policy moved from protectionism to reciprocity, and average tariff levels declined significantly. During this period, there were 30 sessions of Congress, with 16 under unified government (15 Democratic, 1 Republican) and 14 under divided government. Over these 60 years, the overarching goal of promoting reciprocal trade agreements remained largely unchanged, including during the two-year span (1953–1955) when Republicans held unified control.[120]

Following World War II, and in contrast to earlier periods, the Republican Party began supporting trade liberalization. From the early 1950s through the early 1990s, an unusual era of bipartisan consensus emerged, during which both parties generally aligned on trade policy. This occurred during the Cold War, when foreign policy concerns were prominent and partisan divisions were subdued (Bailey 2003).[133]

After the 1993 vote on the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA), Democratic support for trade liberalization declined significantly. By that time, the two major parties had effectively reversed their positions on trade policy. This shift in party alignment primarily reflects changes in regional representation: the South transitioned from being a Democratic stronghold to a Republican one,[134] while the Northeast became increasingly Democratic. As a result, regional views on trade policy remained largely consistent, but the parties came to represent different geographic constituencies.

Current world trends

[edit]

Certain policies of First World governments have been criticized as protectionist, such as the Common Agricultural Policy[136] in the European Union, longstanding agricultural subsidies and proposed "Buy American" provisions[137] in economic recovery packages in the United States.

Heads of the G20 meeting in London on 2 April 2009 pledged "We will not repeat the historic mistakes of protectionism of previous eras". Adherence to this pledge is monitored by the Global Trade Alert,[138] providing up-to-date information and informed commentary to help ensure that the G20 pledge is met by maintaining confidence in the world trading system, deterring beggar-thy-neighbor acts and preserving the contribution that exports could play in the future recovery of the world economy.

Although they were reiterating what they had already committed to in the 2008 Washington G20 summit, 17 of these 20 countries were reported by the World Bank as having imposed trade restrictive measures since then. In its report, the World Bank says most of the world's major economies are resorting to protectionist measures as the global economic slowdown begins to bite. Economists who have examined the impact of new trade-restrictive measures using detailed bilaterally monthly trade statistics estimated that new measures taken through late 2009 were distorting global merchandise trade by 0.25% to 0.5% (about $50 billion a year).[139]

Since then, however, President Donald Trump announced in January 2017 the U.S. was abandoning the TPP (Trans-Pacific Partnership) deal, saying, "We're going to stop the ridiculous trade deals that have taken everybody out of our country and taken companies out of our country, and it's going to be reversed."[140] President Joe Biden largely continued Trump's protectionist policies, and did not negotiate any new free trade agreements during his presidency.[141]

The 2010s and early 2020s have seen an increased use of protectionist economic policies across both developed countries and developing countries worldwide.[142][143]

See also

[edit]- American System (economic plan)

- Autarky

- Brexit

- Currency war

- Developmentalism

- Digital Millennium Copyright Act

- Economic nationalism

- Free trade debate

- Globalization

- Henry C. Carey

- Historiography of the fall of the Western Roman Empire

- Imperial Preference

- International trade

- Market-preserving federalism

- National Policy

- Not invented here

- Project Labor Agreement

- Protected Geographical Status

- Protection or Free Trade

- Protectionism in the United States

- Protective tariff

- Rent seeking

- Resistive economy

- Smoot-Hawley Act

- Tariff Reform League

- 1923 United Kingdom general election

- Voluntary export restraint

- Washington Consensus

Further reading

[edit]- Feenstra, Robert C. 1992. "How Costly Is Protectionism?" Journal of Economic Perspectives, 6 (3): 159–178.

- Milner, Helen V. (1988). Resisting protectionism: global industries and the politics of international trade. Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-01074-8.

- Hudson, Michael (2010). America's Protectionist Takeoff, 1815–1914: The Neglected American School of Political Economy. ISLET. ISBN 978-3-9808466-8-4.

References

[edit]- ^ Piketty, Thomas (19 April 2022). A Brief History of Equality. Belknap Press. Retrieved 5 January 2024.

- ^ Murschetz, Paul (2013). State Aid for Newspapers: Theories, Cases, Actions. Springer Science+Business Media. p. 64. ISBN 978-3-642-35690-2.

Parties of the left in government adopt protectionist policies for ideological reasons and because they wish to save worker jobs. Conversely, right-wing parties are predisposed toward free trade policies.

- ^ Peláez, Carlos (2008). Globalization and the State: Volume II: Trade Agreements, Inequality, the Environment, Financial Globalization, International Law and Vulnerabilities. United States: Palgrave MacMillan. p. 68. ISBN 978-0-230-20531-4.

Left-wing parties tend to support more protectionist policies than right-wing parties.

- ^ Mansfield, Edward (2012). Votes, Vetoes, and the Political Economy of International Trade Agreements. Princeton University Press. p. 128. ISBN 978-0-691-13530-4.

Left-wing governments are considered more likely than others to intervene in the economy and to enact protectionist trade policies.

- ^ Warren, Kenneth (2008). Encyclopedia of U.S. Campaigns, Elections, and Electoral Behavior: A–M, Volume 1. Sage. p. 680. ISBN 978-1-4129-5489-1.

Yet, certain national interests, regional trading blocks, and left-wing anti-globalization forces still favor protectionist practices, making protectionism a continuing issue for both American political parties.

- ^ "The End of Reaganism". POLITICO Magazine. Retrieved 24 March 2017.

- ^ Fairbrother, Malcolm (1 March 2014). "Economists, Capitalists, and the Making of Globalization: North American Free Trade in Comparative-Historical Perspective". American Journal of Sociology. 119 (5): 1324–1379. doi:10.1086/675410. ISSN 0002-9602. PMID 25097930. S2CID 38027389.

- ^ a b c Mankiw, N. Gregory (24 April 2015). "Economists Actually Agree on This: The Wisdom of Free Trade" Archived 14 May 2019 at the Wayback Machine. The New York Times. Retrieved 10 August 2021. "Economists are famous for disagreeing with one another.... But economists reach near unanimity on some topics, including international trade."

- ^ "Economic Consensus On Free Trade". PIIE. 25 May 2017. Retrieved 27 February 2018.

- ^ Poole, William (2004). "Free Trade: Why Are Economists and Noneconomists So Far Apart?". Review. 86 (5). doi:10.20955/r.86.1-6.

- ^ a b c See P. Krugman, "The Narrow and Broad Arguments for Free Trade", American Economic Review, Papers and Proceedings, 83(3), 1993 ; and P. Krugman, Peddling Prosperity: Economic Sense and Nonsense in the Age of Diminished Expectations, New York, W.W. Norton & Company, 1994.

- ^ a b "Free Trade". IGM Forum. 13 March 2012. Retrieved 24 June 2017.

- ^ a b "Import Duties". IGM Forum. 4 October 2016. Retrieved 24 June 2017.

- ^ "Trade Within Europe". IGM Forum. Retrieved 24 June 2017.

- ^ Poole, William (September/October 2004). "Free Trade: Why Are Economists and Noneconomists So Far Apart" Archived 7 November 2017 at the Wayback Machine. Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis Review. 86 (5): pp. 1–6. "... most observers agree that '[t]he consensus among mainstream economists on the desirability of free trade remains almost universal.'" Quote at p. 1.

- ^ Irwin, Douglas (2017). Peddling Protectionism: Smoot-Hawley and the Great Depression. Princeton University Press. pp. vii–xviii. ISBN 978-1-4008-8842-9.

- ^ "The Mitt-Hawley Fallacy". 4 March 2016.

- ^ "Hayek, Trade Restrictions, and the Great Depression". 10 July 2010.

- ^ Poole, William (2004). "Free Trade: Why Are Economists and Noneconomists So Far Apart?". Review. 86 (5). doi:10.20955/r.86.1-6.

One set of reservations concerns distributional effects of trade. Workers are not seen as benefiting from trade. Strong evidence exists indicating a perception that the benefits of trade flow to businesses and the wealthy, rather than to workers, and to those abroad rather than to those in the United States.

- ^ a b Xiong, Ping (2012b). "Patents in TRIPS-Plus Provisions and the Approaches to Interpretation of Free Trade Agreements and TRIPS: Do They Affect Public Health?". Journal of World Trade. 46 (1): 155. doi:10.54648/TRAD2012006.

- ^ Rosenfeld, Everett (11 March 2016). "Here's why everyone is arguing about free trade". CNBC. Retrieved 10 August 2021.

- ^ a b Paul Krugman, Robin Wells & Martha L. Olney, Essentials of Economics (Worth Publishers, 2007), pp. 342–345.

- ^ Wong, Edward; Tatlow, Didi Kirsten (5 June 2013). "China Seen in Push to Gain Technology Insights". The New York Times. Retrieved 16 October 2017.

- ^ Markoff, John; Rosenberg, Matthew (3 February 2017). "China's Intelligent Weaponry Gets Smarter". The New York Times. Retrieved 16 October 2017.

- ^ "The Unpleasant Truth About Chinese Espionage". Observer.com. 22 April 2016. Retrieved 16 October 2017.

- ^ Ippei Yamazawa, "Restructuring the Japanese Economy: Policies and Performance" in Global Protectionism (eds. Robert C. Hine, Anthony P. O'Brien, David Greenaway & Robert J. Thornton: St. Martin's Press, 1991), pp. 55–56.

- ^ Crispin Weymouth, "Is 'Protectionism' a Useful Concept for Company Law and Foreign Investment Policy? An EU Perspective" in Company Law and Economic Protectionism: New Challenges to European Integration (eds. Ulf Bernitz & Wolf-Georg Ringe: Oxford University Press, 2010), pp. 44–76.

- ^ Peter Drahos; John Braithwaite (2002). Information Feudalism: Who Owns the Knowledge Economy?. London: Earthscan. p. 36. ISBN 978-1-85383-917-7.

- ^ [1] Archived 17 October 2006 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ William Poole, Free Trade: Why Are Economists and Noneconomists So Far Apart Archived 7 December 2017 at the Wayback Machine, Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis Review, September/October 2004, 86(5), pp. 1: "most observers agree that '[t]he consensus among mainstream economists on the desirability of free trade remains almost universal.'"

- ^ "Trade Within Europe | IGM Forum". Igmchicago.org. Retrieved 24 June 2017.

- ^ a b Panagariya, Arvind (18 July 2019). "Debunking Protectionist Myths: Free Trade, the Developing World, and Prosperity". Cato Institute Economic Development Bulletin (31). SSRN 3501729.

- ^ Hickel, Jason (2018). The Divide: A Brief Guide to Global Inequality and its Solutions. Windmill Books. ISBN 978-1786090034.

- ^ a b Friedman, Milton; Rose D. Friedman; James Adams (1980). Free to Choose: A Personal Statement. Vol. 249. New York: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich.

- ^ Krugman, Paul R. (1987). "Is Free Trade Passe?". The Journal of Economic Perspectives. 1 (2): 131–44. doi:10.1257/jep.1.2.131. JSTOR 1942985.

- ^ Krugman, Paul (24 January 1997). The Accidental Theorist Archived 20 September 2011 at the Wayback Machine. Slate.

- ^ Magee, Stephen P. (1976). International Trade and Distortions In Factor Markets. New York: Marcel-Dekker.

- ^ Fajgelbaum, Pablo D.; Khandelwal, Amit K. (1 August 2016). "Measuring the Unequal Gains from Trade" (PDF). The Quarterly Journal of Economics. 131 (3): 1113–80. doi:10.1093/qje/qjw013. ISSN 0033-5533. S2CID 9094432.

- ^ Amiti, Mary; Dai, Mi; Feenstra, Robert; Romalis, John (28 June 2017). "China's WTO entry benefits US consumers". VoxEU.org. Retrieved 28 June 2017.

- ^ Rodrik, Dani. "Has Globalization Gone Too Far?" (PDF). Institute for International Economics.

- ^ Furceri, Davide; Hannan, Swarnali A.; Ostry, Jonathon D.; Rose, Andrew K. (2019). Macroeconomic Consequences of Tariffs. International Monetary Fund. p. 4. ISBN 9781484390061.

- ^ Frankel, Jeffrey A; Romer, David (June 1999). "Does Trade Cause Growth?". American Economic Review. 89 (3): 379–99. doi:10.1257/aer.89.3.379. ISSN 0002-8282.

- ^ Panagariya, Arvind (2019). Free Trade and Prosperity: How Openness Helps the Developing Countries Grow Richer and Combat Poverty. Oxford, New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-091449-3.

- ^ a b c d Findlay, Ronald; O'Rourke, Kevin H. (2009). Power and Plenty. Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-14327-9. Retrieved 16 October 2017.

- ^ a b Irwin, Douglas A. (1 January 2001). "Tariffs and Growth in Late Nineteenth-Century America". World Economy. 24 (1): 15–30. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.200.5492. doi:10.1111/1467-9701.00341. ISSN 1467-9701. S2CID 153647738.

- ^ Varian, Brian D. (2022). "Revisiting the tariff-growth correlation: The Australasian colonies, 1866–1900". Australian Economic History Review. 62 (1): 47–65. doi:10.1111/aehr.12233. ISSN 0004-8992.

- ^ H. O'Rourke, Kevin (1 November 2000). "British trade policy in the 19th century: a review article". European Journal of Political Economy. 16 (4): 829–42. doi:10.1016/S0176-2680(99)00043-9.

- ^ Krugman, Paul (21 March 1997). In Praise of Cheap Labor Archived 7 September 2011 at the Wayback Machine. Slate.

- ^ Sicilia, David B. & Cruikshank, Jeffrey L. (2000). The Greenspan Effect, p. 131. New York: McGraw-Hill. ISBN 978-0-07-134919-2.

- ^ "The Case for Protecting Infant Industries". Bloomberg.com. 22 December 2016. Retrieved 24 June 2017.

- ^ a b Baldwin, Robert E. (1969). "The Case against Infant-Industry Tariff Protection". Journal of Political Economy. 77 (3): 295–305. doi:10.1086/259517. JSTOR 1828905. S2CID 154784307.

- ^ O, Krueger, Anne; Baran, Tuncer (1982). "An Empirical Test of the Infant Industry Argument". American Economic Review. 72 (5).

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Choudhri, Ehsan U.; Hakura, Dalia S. (2000). "International Trade and Productivity Growth: Exploring the Sectoral Effects for Developing Countries". IMF Staff Papers. 47 (1): 30–53. doi:10.2307/3867624. JSTOR 3867624.

- ^ Baldwin, Richard E.; Krugman, Paul (June 1986). "Market Access and International Competition: A Simulation Study of 16K Random Access Memories". NBER Working Paper No. 1936. doi:10.3386/w1936.

- ^ Luzio, Eduardo; Greenstein, Shane (1995). "Measuring the Performance of a Protected Infant Industry: The Case of Brazilian Microcomputers" (PDF). The Review of Economics and Statistics. 77 (4): 622–633. doi:10.2307/2109811. hdl:2142/29917. JSTOR 2109811.

- ^ "US Tire Tariffs: Saving Few Jobs at High Cost". PIIE. 2 March 2016. Retrieved 24 June 2017.

- ^ See TRIPS Art. 1(3).

- ^ Gervais, Daniel (2012). The TRIPS Agreement: Negotiating History. London: Sweet & Maxwell. pp. Part I.

- ^ a b Newfarmer, Richard (2006). Trade, Doha, and Development (1st ed.). The World Bank. p. 292.

- ^ Timmermann, Cristian; Henk van den Belt (2013). "Intellectual property and global health: from corporate social responsibility to the access to knowledge movement". Liverpool Law Review. 34 (1): 47–73. doi:10.1007/s10991-013-9129-9. S2CID 145492036. Archived from the original on 23 June 2020. Retrieved 31 October 2020.

- ^ Nebehay, Emma Farge, Stephanie (10 December 2020). "WTO delays decision on waiver on COVID-19 drug, vaccine rights". Reuters. Archived from the original on 28 February 2021. Retrieved 25 February 2021.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "Members to continue discussion on proposal for temporary IP waiver in response to COVID-19". World Trade Organisation. Archived from the original on 27 February 2021. Retrieved 25 February 2021.

- ^ Baker, Brook K.; Labonte, Ronald (9 January 2021). "Dummy's guide to how trade rules affect access to COVID-19 vaccines". The Conversation. Archived from the original on 23 February 2021. Retrieved 25 February 2021.

- ^ "An Unnecessary Proposal: A WTO Waiver of Intellectual Property Rights for COVID-19 Vaccines". Cato Institute. 16 December 2020. Archived from the original on 25 February 2021. Retrieved 25 February 2021.

- ^ "G7 leaders are shooting themselves in the foot by failing to tackle global vaccine access". Amnesty International. 19 February 2021. Retrieved 25 April 2021.

- ^ Pietromarchi, Virginia (1 March 2021). "Patently unfair: Can waivers help solve COVID vaccine inequality?". Al Jazeera. Retrieved 26 April 2021.

- ^ "TRIPS Waiver | Covid-19 Response". covid19response.org.

- ^ "WTO finally agrees on a TRIPS deal. But not everyone is happy". Devex. 17 June 2022.

- ^ DiLorenzo, T. J., Frederic Bastiat (1801–1850): Between the French and Marginalist Revolutions. accessed at [Ludwig Von Mises Institute] 2012-04-13 Archived 13 September 2014 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Keeley, Lawrence (6 February 1996). War Before Civilization: The Myth of the Peaceful Savage Reprint Edition. Oxford University Press, USA. ISBN 0195119126.

- ^ Canada, Asia Pacific Foundation of. "The Opium Wars in China". Asia Pacific Curriculum.

- ^ Yardley, Jonathan (16 March 2009). "Jonathan Yardley Reviews 'The Proud Tower,' by Barbara Tuchman". The Washington Post.

- ^ The National System of Political Economy, by Friedrich List, 1841, translated by Sampson S. Lloyd M.P., 1885 edition, Fourth Book, "The Politics", Chapter 33.

- ^ a b C, Feenstra, Robert; M, Taylor, Alan (23 December 2013). "Globalization in an Age of Crisis: Multilateral Economic Cooperation in the Twenty-First Century". NBER. doi:10.7208/chicago/9780226030890.001.0001. ISBN 978-0-226-03075-3.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ https://www.nytimes.com/2010/03/15/opinion/15krugman.html?src=me Taking On China

- ^ "Economist's View: Paul Krugman: Taking on China".

- ^ "Macroeconomic effects of Chinese mercantilism". 31 December 2009.

- ^ "Opinion | Chinese New Year (Published 2010)". The New York Times. January 2010.

- ^ "Economist's View: Paul Krugman: Chinese New Year".

- ^ "Opinion | the Renminbi Runaround (Published 2010)". The New York Times. 25 June 2010.

- ^ "Economist's View: Paul Krugman: The Renminbi Runaround".

- ^ "Opinion | China, Japan, America (Published 2010)". The New York Times. 13 September 2010.

- ^ "Economist's View: Paul Krugman: China, Japan, America".

- ^ "2015 External Sector Report—Individual Economy Assessments" (PDF). International Monetary Fund: 13. 26 June 2015. Retrieved 11 April 2025.

- ^ Calomiris W., Charles. "Trump Gets His Facts Wrong On China". Forbes. Retrieved 12 April 2025.

- ^ a b c d e f Findlay, Ronald; O'Rourke, Kevin H. (1 January 2003). "Commodity Market Integration, 1500–2000". NBER: 13–64.

- ^ Harley, C. Knick (2004). "7 – Trade: discovery, mercantilism and technology". The Cambridge Economic History of Modern Britain. Cambridge University. pp. 175–203. doi:10.1017/CHOL9780521820363.008. ISBN 978-1-139-05385-3. Retrieved 27 June 2017.

- ^ Williamson, Jeffrey G (1 April 1990). "The impact of the Corn Laws just prior to repeal". Explorations in Economic History. 27 (2): 123–156. doi:10.1016/0014-4983(90)90007-L.

- ^ Daudin, Guillaume; O’Rourke, Kevin H.; Escosura, Leandro Prados de la (2008). "Trade and Empire, 1700–1870". Documents de Travail de l'Ofce.

- ^ Paul Bairoch (1995). Economics and World History: Myths and Paradoxes. University of Chicago Press. pp. 31–32. Archived from the original on 12 October 2017. Retrieved 16 August 2017.

- ^ Tsang, J., "Towards a Brighter Future in Trade and World Development", Hong Kong Industrialist, 2005/12, p. 28

- ^ Baten, Jörg (2016). A History of the Global Economy. From 1500 to the Present. Cambridge University Press. p. 13. ISBN 978-1-107-50718-0.

- ^ Darwin, 2012 pp. 21–22

- ^ Darwin, 2012 p. 166

- ^ Max Savelle (1948). Seeds of Liberty: The Genesis of the American Mind. Kessinger. p. 204ff. ISBN 978-1-4191-0707-8.

{{cite book}}: ISBN / Date incompatibility (help) - ^ Harold Cox, ed., British industries under free trade (1903) pp, 17–18.

- ^ Lynn, Martin (1999). Porter, Andrew (ed.). "British Policy, Trade, and Informal Empire in the Mid-19th Century". The Oxford History of the British Empire: Volume III: The Nineteenth Century. 3: 101–121. doi:10.1093/acprof:oso/9780198205654.003.0006.

- ^ Williamson, Jeffrey G (1 April 1990). "The impact of the Corn Laws just prior to repeal". Explorations in Economic History. 27 (2): 123–156. doi:10.1016/0014-4983(90)90007-L.

- ^ Bairoch, Paul; Burke, Susan (15 June 1989), Mathias, Peter; Pollard, Sidney (eds.), "European trade policy, 1815–1914", The Cambridge Economic History of Europe from the Decline of the Roman Empire (1 ed.), Cambridge University Press, pp. 1–160, doi:10.1017/chol9780521225045.002, ISBN 978-1-139-05450-8, retrieved 6 November 2024

- ^ Varian, Brian D. (2023). "British exports and foreign tariffs: Insights from the Board of Trade's foreign tariff compilation for 1902". The Economic History Review. 76 (3): 827–843. doi:10.1111/ehr.13214. ISSN 0013-0117.

- ^ Coppock, D. J. (1956). "The Climacteric of the 1890's: A Critical Note". The Manchester School. 24 (1): 1–31. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9957.1956.tb00972.x. ISSN 1463-6786.

- ^ Crafts, Nicholas; Mills, Terence C (1 November 2020). "Sooner than you think: the Pre-1914 UK Productivity Slowdown was Victorian not Edwardian". European Review of Economic History. 24 (4): 736–748. doi:10.1093/ereh/hez022. hdl:10.1093/ereh/hez022. ISSN 1361-4916.

- ^ Abel, Deryck (1945). A History of British Tariffs, 1923-1942. London: Heath, Cranton Limited.

- ^ Varian, Brian D. (2019). "The growth of manufacturing protection in 1920s Britain". Scottish Journal of Political Economy. 66 (5): 703–711. doi:10.1111/sjpe.12223. ISSN 0036-9292.

- ^ Foreman-Peck, J. S. (1979). "Tariff Protection and Economies of Scale: The British Motor Industry Before 1939". Oxford Economic Papers. 31 (2): 237–257. doi:10.1093/oxfordjournals.oep.a041444. ISSN 1464-3812.

- ^ Varian, Brian D. (18 August 2022). "Protection and the British rayon industry during the 1920s". Business History. 64 (6): 1131–1148. doi:10.1080/00076791.2020.1753699. ISSN 0007-6791.

- ^ Abel, Deryck (1945). A History of British Tariffs, 1923-1942. London: Heath, Cranton Limited.

- ^ Lloyd, Simon P.; Solomou, Solomos (2020). "The impact of the 1932 General Tariff: a difference-in-difference approach". Cliometrica. 14 (1): 41–60. doi:10.1007/s11698-019-00184-z. ISSN 1863-2505.

- ^ P. J. Cain and A. G. Hopkins, British Imperialism: 1688–2000 (2nd ed. 2002) ch. 10

- ^ Mukherjee, Aditya (2010). "Empire: How Colonial India Made Modern Britain". Economic and Political Weekly. 45 (50): 73–82. JSTOR 25764217.

- ^ Habib, Irfan (1995). "Colonisation of the Indian Economy". Essays in Indian History. New Delhi: Tulika Press. pp. 304–46.

- ^ Gallas, Daniel (August 2018). "The Country Built on Trade Barriers". BBC News. Retrieved 10 November 2021.

- ^ Coatsworth, John; Williamson, Jeffrey (June 2002). "THE ROOTS OF LATIN AMERICAN PROTECTIONISM: LOOKING BEFORE THE GREAT DEPRESSION". NBER Working Paper Series.

- ^ "Mercosur in Brief". mercosur.

- ^ Pinilla, Vicente; Rayes, Agustina (27 September 2018). "How Argentina became a super-exporter of agricultural and food products during the First Globalisation (1880–1929)". Cliometrica. 13 (3): 443–469. doi:10.1007/s11698-018-0178-0. hdl:11336/177360. ISSN 1863-2505. S2CID 158598822.

- ^ "Argentina Trade Policy". Commanding Heights: The Battle For The World Economy. PBS. Archived from the original on 26 April 2011.

- ^ Antonio Cafiero (7 May 2008). "Intimidaciones, boicots y calidad institucional". Página/12. Archived from the original on 11 February 2012.

- ^ Arnaut, Javier. "Understanding the Latin American Gap during the era of Import Substitution: Institutions, Productivity, and Distance to the Technology Frontier in Brazil, Argentina and Mexico's Manufacturing Industries, 1935–1975" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 26 April 2012.

- ^ Jorge Avila (25 May 2006). "Ingreso per cápita relativo 1875–2006". Jorge Avila Opina. Archived from the original on 3 March 2016.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Irwin, Douglas A. (2020). "Trade policy in American economic history" (PDF). Annual Review of Economics. 12 (1): 23–44. doi:10.1146/annurev-economics-070119-024409.

- ^ Harper, Lawrence A. (1939). The English Navigation Laws. New York: Columbia University Press.

- ^ a b Aaron Steelman (August 2017). "Interview: Douglas Irwin". Econ Focus. Federal Reserve Bank of Richmond. Retrieved 4 July 2025.

- ^ Irwin, Douglas A. (2005). "The welfare costs of autarky: evidence from the Jeffersonian embargo, 1807–1809". Review of International Economics. 13: 631–645. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9396.2005.00527.x.

- ^ "A historian on the myths of American trade". The Economist. Retrieved 26 November 2017.

- ^ Irwin, Douglas A. (August 2018). "Did Tariffs Make America Great? A Long-Read Q&A with Trade Historian Douglas A. Irwin". American Enterprise Institute. Retrieved 4 July 2025.

- ^ Daniel Griswold (2011). "Peddling Protectionism: Smoot-Hawley and the Great Depression". Cato Journal. 31 (3): 661–665. ProQuest 905851675. Retrieved 3 April 2025.

- ^ Irwin, Douglas A. (2011). Peddling Protectionism: Smoot-Hawley and the Great Depression. Princeton University Press. p. 116. ISBN 9781400888429.

- ^ "The Mitt-Hawley Fallacy". 4 March 2016.

- ^ "Hayek, Trade Restrictions, and the Great Depression". 10 July 2010.

- ^ Guzik, Erik (31 October 2024). "Tariffs are back in the spotlight, but skepticism of free trade has deep roots in American history". The Conversation. Retrieved 1 November 2024.

- ^ Schulman, Bruce J. (24 October 2024). "Tariffs Don't Have to Make Economic Sense to Appeal to Trump Voters". TIME. Retrieved 1 November 2024.

- ^ Helm, Sally (5 April 2018). "Smoot-Hawley Tariff Act: A Classic Economics Horror Story". NPR.

- ^ Bailey, Michael A. (2003). "The politics of the difficult: Congress, public opinion, and early Cold War aid and trade policies". Legislative Studies Quarterly. 28 (2): 147–177. doi:10.3162/036298003X200845.

- ^ Kuziemko, Ilyana; Washington, Ebonya (2018). "Why did the Democrats lose the South? Bringing new data to an old debate" (PDF). American Economic Review. 108 (10): 2830–2867. doi:10.1257/aer.20161413.

- ^ "Independent monitoring of policies that affect world trade". Global Trade Alert. Retrieved 16 December 2016.

- ^ "A French Roadblock to Free Trade". The New York Times. 31 August 2003. Retrieved 22 May 2010.

- ^ "Brussels Warns US on Protectionism". Dw-world.de. 30 January 2009. Retrieved 16 October 2017.

- ^ "Global Trade Alert". Globaltradealert.org. Retrieved 16 October 2017.

- ^ "Trade and the Crisis: Protect or Recover" (PDF). Imf.org. Retrieved 16 October 2017.

- ^ Baker, Peter (23 January 2017). "Trump Abandons Trans-Pacific Partnership, Obama's Signature Trade Deal". The New York Times. Retrieved 1 July 2018.

- ^ Hayashi, Yuka (28 December 2023). "Biden Struggles to Push Trade Deals with Allies as Election Approaches". The Wall Street Journal.

- ^ Intelligence, fDi (21 June 2023). "Protectionism: trade restrictions reach an all-time high". www.fdiintelligence.com. Retrieved 11 January 2024.

- ^ "The economic implications of rising protectionism: a euro area and global perspective". European Central Bank. 24 April 2019. Retrieved 11 January 2024.

- ^ Economic nationalism is an ideology that prioritizes state intervention in the economy, including policies like domestic control and the use of tariffs and restrictions on labor, goods, and capital movement.

- ^ Economic liberalism is a political and economic ideology that supports a market economy based on individualism and private property in the means of production.

- ^ The General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT) is a legal agreement between many countries, whose overall purpose was to promote international trade by reducing or eliminating trade barriers such as tariffs or quotas. According to its preamble, its purpose was the "substantial reduction of tariffs and other trade barriers and the elimination of preferences, on a reciprocal and mutually advantageous basis."

- ^ France also fought on the side of the UK in the Second Opium War.

External links

[edit] Media related to Protectionism at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Protectionism at Wikimedia Commons- James, Edmund Janes (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 22 (11th ed.). pp. 464–468.

Protectionism

View on GrokipediaCore Concepts

Definition and Principles

Protectionism refers to economic policies implemented by governments to restrict imports and shield domestic industries from foreign competition, thereby favoring local producers over international free trade. These policies typically involve tariffs, which impose taxes on imported goods to raise their prices; import quotas, which limit the quantity of foreign products allowed into the market; subsidies to domestic firms to lower their production costs; and non-tariff barriers such as stringent regulatory standards or administrative delays that disproportionately affect imports.[10][3] The intent is to maintain or expand domestic production capacity, preserve employment in targeted sectors, and achieve a favorable balance of trade by reducing imports relative to exports.[11] At its core, protectionism rests on the principle of national economic sovereignty, positing that unrestricted foreign competition can undermine local industries, particularly those in developing economies or facing subsidized rivals abroad. Proponents argue it enables "infant industries"—new or nascent sectors—to mature without being outcompeted by established foreign entities, fostering long-term self-sufficiency and technological advancement.[12] This approach contrasts with free trade doctrines by emphasizing causal linkages between import barriers and domestic output preservation, often justified by the need to counter practices like dumping, where foreign producers sell below cost to capture market share.[13] Empirical rationales include protecting strategic sectors vital for national security, such as defense manufacturing or food production, where reliance on imports could pose vulnerabilities during geopolitical tensions.[14] Protectionist principles also incorporate revenue generation for governments through tariffs, which historically funded state operations before income taxes became prevalent, as seen in the United States prior to the 1913 income tax amendment.[11] However, these measures inherently transfer resources from consumers, who face higher prices, to protected producers, creating an indirect subsidy that distorts market signals and incentives for efficiency.[10] While rooted in mercantilist ideas of accumulating wealth via trade surpluses, modern applications often invoke equity concerns, such as mitigating job losses from offshoring or addressing environmental externalities not internalized by foreign competitors.[12] Critics from economic orthodoxy, drawing on comparative advantage theory, contend that such principles overlook mutual gains from specialization, but protectionism persists as a tool for policymakers balancing short-term political imperatives against long-term efficiency.[3]Types of Protectionist Measures