Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Rajouri

View on WikipediaThis article has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these messages)

|

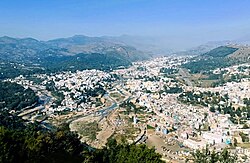

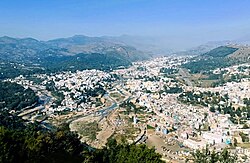

Rajouri or Rajauri (/rəˈdʒɔːri/; Hindustani pronunciation: [ɾɑːd͡ʒɔːɾiː]; IAST: rājaurī) is a city in the Rajouri district in the Jammu division of the Indian union territory of Jammu and Kashmir. It is located about 155 kilometres (96 mi) from Srinagar and 150 km (93 mi) from Jammu city on the Poonch Highway.

Key Information

History

[edit]The first ruler of this Kingdom was Raja Prithvi Pal from the Jarral Rajput clan ruled Rajouri from 1033 to 1192, Prithvi Pal defended Pir Panchal Pass at the time of incursion of Mahmud of Ghazni in 1021 CE.[3] The old name of Rajouri was "Rajapuri" as mentioned in Rajtarangni of Kalhana Pandita written in 1148 CE.

Rajouri came under the suzerainty of the Kashmir Sultanate during the 15th century through the military campaigns of General Malik Tazi Bhat. In 1475, he led conquests that brought Rajouri, along with Poonch, Jammu, Bhimber, Jhelum, Sialkot, and Gujrat, under the administrative control of the Kashmiri Sultan. Local rulers retained limited autonomy but were required to acknowledge the Sultan’s authority and provide tribute and military support. This vassal arrangement continued until the late 16th century, when Mughal Emperor Akbar annexed Kashmir in 1586, ending Kashmir’s control over Rajouri.[4]

During the Mughal rule, the Jarral Rajput rulers or Raja agreed to a treaty with the Mughal Empire and thus were given the title 'Mirza'. In 1810 and 1812, Maharaja Ranjit Singh attempted to conquer Bhimber, Kotli, and Rajouri. However, Rajouri successfully resisted these invasions.[5] In 1813, Gulab Singh of Jammu captured Rajouri for the Sikh Empire of Maharaja Ranjit Singh, by defeating Raja Aghar Khan.[6] After this, Rajouri became part of the Sikh Empire. But parts of it were given as jagirs to Raja Rahimullah Khan (the brother of Raja Agarullah Khan) and other parts to Gulab Singh.[7]

Following the First Anglo-Sikh War and the Treaty of Amritsar (1846), all the territories between the Ravi River and the Indus were transferred to Gulab Singh, and he was recognised as an independent Maharaja of Jammu and Kashmir. Thus Rajouri became a part of the princely state of Jammu and Kashmir.[8] Gulab Singh changed the name of Rajouri to Rampur. He appointed Mian Hathu as Governor of Rajouri, who remained in Rajouri up to 1856.[9] Mian Hathu constructed a stunning temple in between Thanna Nallah in close proximity to Rajouri city. He also built Rajouri Fort at Dhannidhar village.[citation needed]

After Mian Hathu, Rajouri was transformed into a tehsil and affiliated with Bhimber district. In 1904, this tehsil was separated from Bhimber and affiliated with the Reasi district.[8]

The area of Rajouri principality included proper Rajouri, Thanna, Bagla Azim Garh, Behrote, Chingus, Darhal, Nagrota and Phalyana etc.

Partition

[edit]After the Partition of India and the accession of Jammu and Kashmir to India in October 1947, there followed the First Kashmir War between India and Pakistan. The Pakistani raiders, along with the rebels and deserters from the western districts of the state, captured Rajouri on 7 November 1947. The 30,000 Hindus and Sikhs living in Rajouri were reportedly killed, wounded or abducted.[10][11][12] Rajouri was recaptured on 12 April 1948 by the 19 Infantry Brigade of the Indian Army under the command of Second Lieutenant Rama Raghoba Rane. Rane, despite being wounded, launched a bold tank assault by conveying the tanks over the Tawi river bed in order to avoid the road blocks along the main road.[13] When the Indian Army entered the town, the captors had fled, having destroyed most of the town and killing all its inhabitants. After the arrival of the Army, some 1,500 refugees that had fled to the hills, including women and children, returned to the town.[14] The ceasefire line at the end of the War ran to the west of the Rajouri-Reasi district.

Inside India

[edit]Soon after the war, the Rajouri and Reasi tehsils were separated. The Rajouri tehsil was merged with the Indian-administered Poonch district to form the Poonch-Rajouri district.[8] The Reasi tehsil was merged with the Udhampur district.

On 1 January 1968, the two tehsils were reunited and the resulting district was named the Rajouri district.[8]

The Reasi tehsil was also separated out in 2006 into a separate Reasi district. The present Rajouri district comprises the 1947 Rajouri tehsil.

Rajouri witnessed some of the toughest fighting during the Second Kashmir War in 1965. Pakistani infiltration in Kashmir during Operation Gibraltar caused Rajouri to be initially captured from the Indian Army by undercover Pakistani commandos. But the wider operation failed and, with all-out war with India looming, Pakistan withdrew its troops. Major Malik Munawar Khan Awan, a Pakistani commando officer who led the attack on Rajouri on the night of 15 September 1965, was later awarded the title "King of Rajouri" by the Government of Pakistan.[15]

Geography and education

[edit]Rajouri is located at 33°23′N 74°18′E / 33.38°N 74.3°E.[16] It has an average elevation of 915 metres (3001 feet).

Rajouri has its own deemed University Baba Ghulam Shah Badshah University popularly known as BGSBU which offers various Diploma, UG and PG courses. It also has one Government Medical College GMC Rajouri along with other degree colleges.

Climate

[edit]The climate of Rajouri is somewhat cooler than the other surrounding plains. Summers are short and pleasant. The summer temperature generally does not exceed 30 degrees. Winters are cool and chilly characterized with rainfall due to western disturbances. Snowfall is scanty but may occur in cool months like that of December 2012. Average rainfall is 769 millimetres (26.3 in) in the wettest months The average temperature of summer is 23 °C and average temperature of winter is 8 °C.[17]

Demographics

[edit]At the 2011 census,[19] Rajouri itself had a population of 37,552 while the population within the municipal limits was 41,552. Males constituted 57% of the population and females 43%. Rajouri had an average literacy rate of 77%, higher than the national average of 75.5%: male literacy was 83% and female literacy was 68%. 12% of the population was under 6 years of age. The people are mostly Paharis and Gujjars.

Religion

[edit]Islam is the largest religion in Rajouri City followed by over 62.71% of the people. Hinduism is the second-largest religion with 34.54% adherents.and Sikhism form 2.41% of the population.[18]

Members of Legislative Assembly

[edit]| Election | Member | Party | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1962 | Abdul Aziz Shawal | Jammu and Kashmir National Conference | |

| 1967 | Abdul Rashid | ||

| 1972 | Chowdhary Talib Hussain | ||

| 1977 | |||

| 1983 | |||

| 1987 | Mirsa Abdul Rashid | ||

| 1996 | Mohammad Sharief Tariq | ||

| 2002 | Mohammad Aslam | ||

| 2008 | Shabbir Ahmed Khan | Indian National Congress | |

| 2014 | Qamar Hussain | Jammu and Kashmir Peoples Democratic Party | |

| 2024 | Iftkar Ahmed | Indian National Congress | |

Transport

[edit]Air

[edit]Rajouri Airport is located 1 km from the town but currently is non-operational. The nearest airport to Rajouri is Jammu Airport which located 154 kilometres from Rajouri and is a 4 hr drive. Helicopter services linking Rajouri district to Jammu started on 13 September 2017, but it was aborted later.[20]

Rail

[edit]Rajouri does not have its own railway station. The nearest railway station to Rajouri is Jammu Tawi railway station which is located at a distance of 151 kilometres from the town and is a 4 hr drive. There are plans to connect Rajouri by rail through the Jammu–Poonch Railway Line in the near future.[21]

Road

[edit]Rajouri is well-connected by road to other towns, villages and cities of Jammu and Kashmir. The NH 144A passes through Rajouri.

See also

[edit]- Banda Singh Bahadur, Sikh general

- Baba Ghulam Shah Badshah University, Rajouri

References

[edit]- ^ "The Jammu and Kashmir Official Languages Act, 2020" (PDF). The Gazette of India. 27 September 2020. Retrieved 27 September 2020.

- ^ "Parliament passes JK Official Languages Bill, 2020". Rising Kashmir. 23 September 2020. Archived from the original on 24 September 2020. Retrieved 23 September 2020.

- ^ "History | Rajouri, Government of Jammu and Kashmir | India". Rajouri.nic.

- ^ Parmu, R. K. (1969). A History of Muslim Rule in Kashmir, 1320-1819. People's Publishing House.

- ^ Charak, Sukhdev Singh. English Translation Of Gulabnama Of Diwan Kirpa Ram. p. 40.

- ^ Panikkar, Gulab Singh 1930, p. 31.

- ^ Panikkar, Gulab Singh 1930, p. 40.

- ^ a b c d Sudhir S. Bloeria, Militancy in Rajouri and Poonch, South Asia Terrorism Portal, 2001.

- ^ Bloeria, Sudhir S. (2000), Pakistan's Insurgency Vs India's Security: Tackling Militancy in Kashmir, Manas Publications, p. 37, ISBN 978-81-7049-116-3

- ^ Prasad, Sri Nandan; Pal, Dharm (1 January 1987). Operations in Jammu & Kashmir, 1947-48. History Division, Ministry of Defence, Government of India. pp. 49–50.

- ^ V. K. Singh, Leadership in the Indian Army 2005, p. 160.

- ^ Ramachandran, Empire's First Soldiers 2008, p. 171.

- ^ Rama Raghoba Rane received a Param Vir Chakra for his gallantry.

- ^ Sarkar, Outstanding Victories of the Indian Army 2016, pp. 37–40.

- ^ Niaz, Anjum (21 April 2013). "The 20-watt fountain of energy". Dawn.

- ^ Falling Rain Genomics, Inc - Rajouri[permanent dead link]

- ^ IMD Archived 2012-03-15 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b "Rajouri Town Population". Census India. Retrieved 27 September 2020.

- ^ "Census of India 2001: Data from the 2001 Census, including cities, villages and towns (Provisional)". Census Commission of India. Archived from the original on 16 June 2004. Retrieved 1 November 2008.

- ^ Service, Tribune News. "Poonch, Rajouri get chopper services". Tribuneindia News Service. Retrieved 7 July 2022.

- ^ "Centre nod to Jammu-Poonch rail line after several years". Daily Excelsior. 23 December 2018. Retrieved 24 December 2018.

Bibliography

[edit]- Panikkar, K. M. (1930), Gulab Singh, London: Martin Hopkinson Ltd

- Ramachandran, D. P. (2008), Empire's First Soldiers, Lancer Publishers, pp. 171–, ISBN 978-0-9796174-7-8

- Sarkar, Col. Bhaskar (2016), Outstanding Victories of the Indian Army, 1947-1971, Lancer Publishers, pp. 40–, ISBN 978-1-897829-73-8

- Singh, V. K. (2005), Leadership in the Indian Army: Biographies of Twelve Soldiers, SAGE Publications, pp. 160–, ISBN 978-0-7619-3322-9

Rajouri

View on GrokipediaHistory

Ancient and Medieval Foundations

The region encompassing modern Rajouri, historically referred to as Rajapuri or Rampur, traces its ancient foundations to early hill state formations amid Indo-Aryan migrations and Buddhist influences, with textual mentions predating organized principalities. In the 4th century BCE, it constituted part of the Abhisara confederacy, a semi-independent hill polity allied with Punjab kingdoms, functioning as a conduit for trade routes during the subsequent Mauryan expansion under Ashoka's patronage around 250 BCE.[6] By the 7th century CE, the Chinese pilgrim Xuanzang documented Rajapuri as a fortified town under Kashmiri overlordship, noting its strategic position en route to pilgrimage sites and its governance by local chieftains amid Buddhist decline.[6] Epics like the Mahabharata associate the area with the legendary Panchala Desa kingdom under King Panchala Naresh, whose daughter Draupadi wed the Pandavas, though such narratives reflect oral traditions rather than corroborated archaeology, with sparse material evidence like pottery shards indicating continuity from Gandhara cultural spheres.[6] Al-Biruni's 11th-century observations in Kitab al-Hind further describe the Pir Panjal region's tribal polities, including Rajouri's precursors, as semi-autonomous amid Ghaznavid raids.[6] Medieval consolidation began around 1003 CE with the establishment of Rajouri as a distinct principality under Raja Prithvi Paul of the Paul dynasty, marking a shift from tributary status to assertive local rule fortified against Kashmiri incursions.[6] The Pauls governed from 1033 to 1194 CE, exemplified by Raja Sangram Paul's reign starting 1063 CE and his successful defense of the Pir Panjal Pass against Kashmir's Raja Harsha in 1089 CE, as chronicled in Kalhana's Rajatarangini, which details repeated expeditions and tribute demands on Rajapuri's lords.[6] [9] This era saw Rajouri's rulers, often Khasha-origin chieftains, leverage terrain for autonomy, with Kalhana portraying Rajapuri as a refractory hill state resisting Utpala and Lohara dynasties' expansions from Kashmir.[10] The dynasty's end came in 1194 CE when Noor-ud-Din, a Jarral Rajput convert to Islam, overthrew Raja Amna Paul, inaugurating Muslim Jarral rule that persisted until 1846 CE, blending local Rajput traditions with emerging Sultanate influences while retaining raja titles.[6] Subsequent Jarral leaders, such as Anwar Khan from 1252 CE, fortified the town with mosques and sarais, often under Mughal-era patronage post-16th century, solidifying Rajouri's medieval identity as a frontier buffer.[6]Period of Princely Rule and Regional Dynasties

Rajouri established itself as an independent principality around 1003 AD, initially under the Paul dynasty of rulers who defended the region against invasions from Kashmir and beyond.[6] The Pauls governed from 1033 to 1194 AD, with key figures including Raja Prithvi Paul (r. circa 1033–?), who repelled attackers at Pir Panchal Pass in 1021 AD; Janki Paul (r. 1035 AD); Sangram Paul (r. 1063 AD), who resisted Raja Harash of Kashmir in 1089 AD; Som Paul (r. 1101 AD); Bahu Paul (r. 1113 AD); and Amna Paul (r. until 1194 AD).[6] The Jarral Rajput dynasty succeeded the Pauls in 1194 AD following a revolt led by Raja Noor-Ud-Din, who overthrew Amna Paul and established Muslim rule over the principality, which endured for over 650 years until 1846 AD.[6] Notable Jarral rulers included Anwar Khan (r. 1252 AD), Shah-Ud-Din (r. 1412 AD), Mast Wali Khan (r. 1565 AD), Taj-Ud-Din (r. 1604 AD), and the final raja, Raheem Ullah Khan (r. 1819–1846 AD), during whose tenure the annual revenue reached Rs. 3 lakhs.[6] The Jarrals, claiming descent from ancient Rajput lineages, maintained semi-autonomy amid external pressures; they embraced Islam while retaining the title "Raja," rebuilt the city with forts and mosques, and facilitated Mughal travel routes, as Al-Biruni noted a visit in 1036 AD under Sultan Masud.[6] Sikh incursions intensified in the early 19th century, with Raja Aggar Ullah Khan clashing against Maharaja Ranjit Singh in 1815 AD, leading to temporary subjugation under Sikh suzerainty.[6] Full integration into the princely state of Jammu and Kashmir occurred on 21 October 1846 via the Treaty of Amritsar, through which the British transferred the region to Maharaja Gulab Singh of the Dogra dynasty, ending Jarral sovereignty.[6] Although Gulab Singh had earlier subdued local resistance, including capturing Raja Aghar Khan around 1821 AD while serving Sikh interests, Rajouri's formal annexation aligned with the Dogra consolidation of Jammu, Kashmir, and Ladakh into a unified princely state.[6] Under Dogra administration, the area was briefly renamed Rampur and placed under governor Mian Hathu in 1846 AD, who constructed a temple and fort; it later functioned as a tehsil under Bhimber until 1904 AD, then Reasi, retaining administrative significance until the princely state's accession to India in 1947 AD.[6] The Dogra period emphasized revenue collection and infrastructure, such as road maintenance from Mughal eras, amid a landscape of communal harmony under Hindu rulers governing a Muslim-majority populace.[6]Partition-Era Conflicts and Massacres

In the lead-up to the partition of India, tensions in the Poonch-Rajouri region escalated due to a rebellion by Muslim ex-servicemen and locals against the Dogra ruler Maharaja Hari Singh, sparked by grievances over high taxation and disarmament policies imposed in mid-1947.[11] This uprising, which began as a "No Tax" campaign in June 1947, aligned with pro-Pakistan sentiments and evolved into armed resistance, drawing support from irregular forces across the border.[11] The situation intensified with the tribal invasion of Jammu and Kashmir launched on October 22, 1947, by Pashtun lashkars from Pakistan's North-West Frontier Province, backed by Pakistani military elements disguised as tribal warriors.[12] These forces advanced rapidly, capturing Rajouri on November 7, 1947, amid the collapse of state defenses in the area.[13] Upon occupation, the invaders targeted the Hindu and Sikh populations, initiating widespread massacres characterized by indiscriminate killings, looting, and atrocities against civilians, including women and children.[14] The peak of violence occurred on November 11-12, 1947, when thousands of Hindus and Sikhs were slaughtered in Rajouri, with estimates indicating heavy casualties among the non-Muslim minorities who comprised a significant portion of the town's residents prior to the invasion.[15] [14] The massacres continued sporadically until April 1948, as the region remained under raider control, contributing to the ethnic cleansing of non-Muslims and forcing survivors into flight or hiding.[16] Indian forces, following the Maharaja's accession to India on October 26, 1947, launched operations to reclaim lost territories; Rajouri was liberated on April 12, 1948, after prolonged siege and combat, marking the end of the immediate occupation but leaving a legacy of demographic upheaval in the district.[16] These events formed part of the broader Indo-Pakistani War of 1947-1948, where communal violence intertwined with strategic invasions, resulting in mutual atrocities across Jammu province but distinctly targeting minorities in captured zones like Rajouri.[12]Integration into Independent India

Following the accession of the princely state of Jammu and Kashmir to the Dominion of India on October 26, 1947, Rajouri fell under the control of Pakistani-backed tribal militias and local rebels by mid-November 1947, amid the broader Indo-Pakistani War of 1947–1948.[17] [8] These forces, including elements from the Azad Kashmir movement originating in Poonch, overran the town after overcoming Dogra state troops, severing it from Indian administration for several months.[18] The loss disrupted supply lines to western Jammu and contributed to ongoing insurgent threats in the region. Indian military efforts to reclaim Rajouri intensified in early 1948 as part of a broader counteroffensive following victories at Naushera and Jhangar. On April 8, 1948, the Indian Army's 50th Parachute Brigade, supported by armored units, advanced toward Rajouri, with Second Lieutenant Raghunath H. Rane's engineering efforts—breaching multiple enemy roadblocks under fire—enabling tank access despite intense resistance.[8] [19] Troops from the 1st Kumaon Regiment, backed by tanks, assaulted fortified positions, culminating in the town's recapture on April 12, 1948, after fierce fighting that inflicted heavy casualties on the defenders, estimated at over 150 killed and 200 wounded in preceding engagements.[20] [18] The successful liberation integrated Rajouri firmly into India's administered territory within Jammu and Kashmir, with the town serving as a strategic base for further operations against remaining pockets of resistance west of the Pir Panjal range. Rane's actions earned him the Param Vir Chakra, India's highest military honor, highlighting the critical role of individual initiative in restoring control.[8] Following the ceasefire agreement on January 1, 1949, Rajouri remained south of the Line of Control, solidifying its status as part of the Indian Union without subsequent territorial disputes altering its alignment.[17]Geography

Topography and Natural Features

Rajouri district features a predominantly mountainous terrain forming part of the Pir Panjal Himalayan range, with elevations ranging from alluvial plains in the southwest to peaks exceeding 4,000 meters in the north. The northern boundary is defined by the southwestern flank of the Pir Panjal Range, reaching a maximum altitude of 4,535 meters at Dhakiar-Rupri, while the southern limits are marked by the Siwalik and Murree hills. This varied physiography includes deeply incised river valleys, such as those along the Tawi River, and fault-induced alluvial basins that support limited habitable lowlands amid the rugged highlands.[21][22][23] The district spans approximately 2,630 square kilometers, with the southwestern portion characterized by the alluvial plains of the Tawi basin and the northern areas dominated by steep, forested slopes and volcanic Panjal traps—massive basalt formations prevalent in the northwest, historically quarried for construction. Perennial rivers, including the Munawar Tawi (also known as Rajouri or Naushera Tawi), Ans River, and their tributaries like Sailani and Sukhtao Nallah, drain the region, carving habitable valleys through the otherwise inhospitable terrain and ultimately feeding into the Chenab River system. These hydrological features contribute to soil fertility in lower elevations, contrasting with the rocky, less arable uplands.[24][21][25] Extensive forests cloak much of the hilly and mountainous zones, comprising oak-dominated woodlands and diverse woody flora exceeding 340 species across 78 families, reflecting the district's integration into Jammu and Kashmir's broader ecological zones with over 40% forest cover statewide. These natural woodlands, interspersed with medicinal and fodder plants, enhance biodiversity but face pressures from elevation-driven vegetation gradients and land-use changes. Volcanic and sedimentary rock exposures, alongside terraced slopes, underscore the geological dynamism shaped by tectonic activity in the Himalayan foothills.[21][26][27]Hydrology and Soil Composition

The hydrology of Rajouri district is characterized by a network of rivers and streams primarily draining into the Chenab River basin, with major tributaries including the Ans River, which joins the Chenab at Chamb; the Nowshera Tawi; and the Munawar Tawi, which flows through the district's floodplains and supports local agriculture.[21][23] Other significant streams such as Sukh Tawi, Jamola, Darhal, and Khandli originate from the Pir Panjal range, contributing to a dendritic drainage pattern influenced by the hilly topography and seasonal precipitation.[28] These water bodies provide essential irrigation for crops like maize, wheat, and rice, though challenges like river encroachment and poor cross-drainage infrastructure in urban areas exacerbate flooding risks.[29] Groundwater resources remain underexploited, with a development stage of 7.77% as of 2025, classifying the district in the safe category and indicating potential for sustainable extraction through shallow aquifers in valley alluvium.[30] Soil composition in Rajouri varies by elevation and land use, predominantly featuring brown earth or brown forest soils across much of the district, which are influenced by the region's temperate climate and vegetative cover.[31] In floodplain areas like those along the Munawar Tawi, soils are typically clay loam in texture, black in color, non-calcareous, and acidic with pH ranging from 4.8 to 5.7, supporting paddy and wheat cultivation through seasonal nutrient replenishment from fluvial deposits.[32] Overall soil reaction spans slightly acidic to moderately alkaline, with fertility generally higher at elevated altitudes due to thicker organic layers; macronutrient levels include organic carbon at 4.1–5.2%, available nitrogen at 212–451 kg/ha, phosphorus at 30–99 kg/ha, and potassium at 85–250 kg/ha, though micronutrients like zinc and iron show seasonal and locational variability.[33] These characteristics render the soils moderately productive for horticulture and cereals, but erosion susceptibility in steeper terrains necessitates conservation practices.[34]Climate and Environment

Seasonal Weather Patterns

Rajouri district exhibits a humid subtropical monsoon climate, classified as Cwa under the Köppen system, with pronounced seasonal variations influenced by its location in the foothills of the Pir Panjal range. Winters are mild and dry, summers hot and increasingly humid leading into the monsoon, which delivers the majority of annual precipitation, followed by a temperate post-monsoon period. Annual average temperatures range from lows around 8–10 °C in winter to highs exceeding 40 °C in early summer, with total rainfall concentrated between June and September, often amounting to over 70% of the yearly total in the Jammu region, including Rajouri. During winter (December–February), daytime highs average 18–22 °C and nighttime lows 8–10 °C, with clear skies and minimal precipitation—typically 1–5 rainy days per month and less than 50 mm total. Frost is possible in elevated areas above 1,000 meters, though snowfall is infrequent at lower altitudes like Rajouri town (elevation ~900 m).[35] The pre-monsoon summer (March–May) sees rapid warming, with highs climbing to 27 °C in March, 33 °C in April, and 39 °C in May, alongside lows of 14–25 °C. Rainfall increases modestly due to local thunderstorms, averaging 6–9 rainy days monthly, marking the transition to humid conditions.[35] The southwest monsoon dominates from June to September, bringing heavy, often intense rainfall that peaks in July with up to 13 rainy days and contributes the bulk of annual precipitation (typically 800–1,200 mm region-wide, with higher amounts in Rajouri's hilly terrain). Daytime temperatures remain elevated at 35–41 °C, but high humidity exacerbates discomfort; flooding and landslides are common risks during prolonged downpours.[35] Post-monsoon autumn (October–November) features mild cooling, with highs of 25–32 °C and lows of 14–20 °C, retreating humidity, and sparse rainfall (2–3 days monthly), providing the most comfortable period for outdoor activities.[35]| Month | Avg. High (°C) | Avg. Low (°C) | Rainy Days |

|---|---|---|---|

| January | 18 | 8 | 4 |

| February | 22 | 10 | 5 |

| March | 27 | 14 | 6 |

| April | 33 | 19 | 6 |

| May | 39 | 25 | 9 |

| June | 41 | 29 | 7 |

| July | 37 | 29 | 13 |

| August | 35 | 27 | 11 |

| September | 35 | 25 | 5 |

| October | 32 | 20 | 3 |

| November | 25 | 14 | 2 |

| December | 20 | 9 | 1 |

Environmental Challenges and Resource Management

Rajouri district, situated in the rugged Pir Panjal range of the western Himalayas, faces significant environmental challenges exacerbated by its steep topography, seismic activity, and vulnerability to climate variability. Frequent landslides, triggered by heavy monsoon rains and earthquakes, pose recurrent threats to infrastructure and settlements; for instance, multiple landslides in September 2025 blocked key roads like the Kotranka-Khawas stretch and Jammu-Rajouri National Highway, disrupting connectivity and necessitating evacuations of 19 families in affected areas due to land sinking. Soil erosion accompanies these events, particularly in deforested slopes, where loss of vegetative cover accelerates topsoil runoff and reduces land productivity, as observed in anthropogenic-disturbed forests across pine, oak, fir, and mixed types along elevational gradients.[36][37][38][39][40] Deforestation and forest fires further compound these issues, with Rajouri recording the highest annual tree cover loss from fires in Jammu and Kashmir between 2001 and 2022, averaging 9 hectares per year, driven by drier conditions linked to climate change. Local perceptions in the district highlight observed shifts such as erratic rainfall, prolonged dry spells, and glacier retreat, aligning with broader Himalayan trends that heighten vulnerability in this impoverished, agriculture-dependent region. Water resources are strained by contamination risks, including heavy metals and non-metals in groundwater, which pose health threats, as evidenced by a 2025 ban on spring water use in Badhal village following mystery deaths potentially tied to polluted sources. Solid waste mismanagement, including indiscriminate dumping into stormwater drains since at least 2017, exacerbates urban pollution and drainage blockages in Rajouri town.[41][42][43][44][45] Resource management initiatives focus on mitigating these pressures through targeted conservation. The Jammu and Kashmir Soil and Water Conservation Department emphasizes sustainable practices to protect forests and agriculture, including soil stabilization and watershed management to curb erosion in hilly terrains like Rajouri. Forest regeneration studies reveal varying success across types—oak forests show higher natural regeneration potential than pine—amid pressures from fuelwood extraction and grazing, prompting calls for community-based sustainable utilization to balance livelihoods and biodiversity. Groundwater assessments by the Central Ground Water Board underscore the need for quantitative monitoring, as springs remain primary sources in hilly areas, vulnerable to overexploitation and climate-induced variability. Broader efforts under the State Action Plan on Climate Change address extreme weather amplification, though implementation in remote districts like Rajouri lags due to infrastructural constraints.[40][30][46]Demographics

Population Trends and Density

The population of Rajouri district stood at 642,415 according to the 2011 Census of India, marking an increase from 483,284 recorded in the 2001 census.[47][48] This represented a decadal growth rate of 32.93 percent, exceeding the Jammu and Kashmir state average of 23.64 percent for the same period.[48] With a district area of 2,630 square kilometers, Rajouri's population density was 244 persons per square kilometer as of 2011.[3][48] Approximately 91.8 percent of the population resided in rural areas (590,101 individuals), while 8.2 percent (52,314) lived in urban settings, reflecting the district's predominantly agrarian and dispersed settlement patterns.[48][49] No official census data has been released since 2011 due to delays in India's national enumeration process, though provisional estimates and administrative records continue to reference the 2011 figures for planning purposes.[3] The sex ratio was 860 females per 1,000 males, indicating a moderate gender imbalance consistent with regional trends in Jammu division.[48]Religious Demographics

According to the 2011 Census of India, Muslims form the largest religious group in Rajouri district, comprising 62.71% of the total population, or 402,879 individuals.[48] Hindus constitute the second-largest group at 34.54%, totaling 221,880 persons.[48] Sikhs account for 2.41% (15,513 people), while Christians represent a small minority of 0.15% (983 individuals).[48] Other religions, including Buddhists, Jains, and those not stating a religion, make up the remaining less than 1%.[48]| Religion | Percentage | Population (2011) |

|---|---|---|

| Muslim | 62.71% | 402,879 |

| Hindu | 34.54% | 221,880 |

| Sikh | 2.41% | 15,513 |

| Christian | 0.15% | 983 |

Linguistic and Ethnic Composition

Rajouri district's ethnic composition is dominated by two primary groups: the Pahari people and the Gujjar-Bakerwal tribes. The Gujjars and Bakerwals, classified as a Scheduled Tribe since 1991, represent a substantial segment of the population, with Scheduled Tribe individuals comprising approximately 36.5% in key tehsils like Rajauri, indicative of broader district patterns dominated by these nomadic and semi-nomadic Muslim pastoralists.[50] [53] The Pahari community, historically non-tribal until granted Scheduled Tribe status in 2024, predominates in rural villages and includes Muslims, Hindus, and Sikhs, forming the core settled population across much of the district.[54] These groups collectively account for over 90% of residents, reflecting the Pir Panjal region's hill-dwelling and tribal dynamics, with Gujjar-Bakerwals concentrated in upland meadows and Paharis in valleys and lower hills.[55] Smaller ethnic elements include Dogra communities speaking Dogri, primarily in transitional areas near Jammu, and Kashmiri-speakers limited to about 7% of the populace, often in urban pockets or migrant settlements.[55] The district's 2011 population of 642,415 features a Muslim majority (62.71%), encompassing most Gujjars, Bakerwals, and Pahari Muslims, alongside Hindu and Sikh minorities within the Pahari fold.[48] Linguistically, Indo-Aryan vernaculars prevail, with Pahari-Pothwari (a Western Pahari dialect akin to Pothohari) spoken by the Pahari majority and Gojri (also known as Gujari) by Gujjars and Bakerwals.[56] Other tongues include Dogri (declining to around 1-7% from prior censuses due to assimilation) and Kashmiri, alongside Hindi and Urdu as lingua francas in administration and education.[57] Official 2011 census mother-tongue data reports Hindi at 93.04%, but this aggregates diverse local dialects and Urdu variants under broader categories, underrepresenting specific vernaculars like Pahari and Gojri due to limited sub-classification in Jammu and Kashmir surveys.[58] Kashmiri accounts for 2.23%, reflecting its minority status.[58] English serves urban elites, while Poonchi (a Pahari variant) persists in border sub-regions.Economy

Agricultural Base and Crop Production

Agriculture in Rajouri district constitutes the primary economic activity for the majority of the population, characterized by subsistence farming on small landholdings averaging 0.95 hectares. The net sown area spans 53,727 hectares, with a gross cropped area of 105,880 hectares, reflecting a cropping intensity of approximately 197%. Predominantly rainfed, only 4,889 hectares—or about 9% of the net sown area—benefit from assured irrigation, primarily through canals and other minor sources, rendering crop yields vulnerable to erratic monsoons and soil erosion in the hilly terrain.[59][60] The district's soils, including brown-red podzolic types, sub-mountainous loams, and sandy clay variants (classified as Entisols, Alfisols, and Ultisols), support a mix of cereal-dominated cultivation suited to the temperate to subtropical climate. Common practices emphasize contour farming, mulching, and intercropping (e.g., maize with rajmash beans) to mitigate slope-induced runoff and enhance soil fertility in acidic, non-calcareous profiles with pH ranging from 4.8 to 5.7. Maize dominates kharif cropping, followed by limited paddy in valley pockets, while wheat prevails in rabi; pulses and fodder crops supplement these staples.[60][32] Key production metrics for principal crops, based on district-level assessments, are summarized below:| Crop | Season | Area ('000 ha) | Production ('000 tonnes) | Productivity (quintals/ha) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Maize | Kharif | 46.643 | 845.37 | 18.12 |

| Wheat | Rabi | 45.306 | 705.82 | 15.57 |

| Paddy | Kharif | 5.291 | 63.36 | 11.97 |