Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Nuclear reactor core

View on WikipediaThis article needs additional citations for verification. (April 2025) |

A nuclear reactor core is the portion of a nuclear reactor containing the nuclear fuel components where the nuclear reactions take place and the heat is generated.[1] Typically, the fuel will be low-enriched uranium contained in thousands of individual fuel pins. The core also contains structural components, the means to both moderate the neutrons and control the reaction, and the means to transfer the heat from the fuel to where it is required, outside the core.

Water-moderated reactors

[edit]Inside the core of a typical pressurized water reactor or boiling water reactor are fuel rods with a diameter of a large gel-type ink pen, each about 4 m long, which are grouped by the hundreds in bundles called "fuel assemblies". Inside each fuel rod, pellets of uranium, or more commonly uranium oxide, are stacked end to end. Also inside the core are control rods, filled with pellets of substances like boron or hafnium or cadmium that readily capture neutrons. When the control rods are lowered into the core, they absorb neutrons, which thus cannot take part in the chain reaction. Conversely, when the control rods are lifted out of the way, more neutrons strike the fissile uranium-235 (U-235) or plutonium-239 (Pu-239) nuclei in nearby fuel rods, and the chain reaction intensifies. The core shroud, also located inside of the reactor, directs the water flow to cool the nuclear reactions inside of the core. The heat of the fission reaction is removed by the water, which also acts to moderate the neutron reactions.

Graphite-moderated reactors

[edit]

There are also graphite moderated reactors in use.

One type uses solid nuclear graphite for the neutron moderator and ordinary water for the coolant. See the Soviet-made RBMK nuclear-power reactor. This was the type of reactor involved in the Chernobyl disaster.

In the Advanced Gas-cooled Reactor, a British design, the core is made of a graphite neutron moderator where the fuel assemblies are located. Carbon dioxide gas acts as a coolant and it circulates through the core, removing heat.

There have also been several experimental reactors that use graphite for moderation, such as the pebble bed reactor concepts and the molten-salt reactor experiment.

Experimental and developmental reactors

[edit]Several merely experimental or hypothetical nuclear reactor cores are mentioned below.

There have been developmental graphite-moderated nuclear power reactors that were cooled by helium gas. These are no longer in service.

The core of a molten salt reactor is a block of graphite through which holes are bored in which molten salt circulates. The graphite serves as a neutron moderator, it is the solid structure of the reactor. The molten salt that circulates in the channels is both the fuel and the coolant, it contains the fissionable material needed to sustain the chain reaction.

A set of compact nuclear reactors were developed by the United States under the Systems Nuclear Auxiliary Power Program (SNAP). One SNAP reactor, the SNAP-10A was launched into space and was successfully operated for 43 days in 1965.

Aqueous homogeneous reactors cores employ water in which soluble nuclear salts (usually uranyl sulfate or uranyl nitrate) have been dissolved. As the water serves as the solvent for the uranium salts, it serves as the fuel. As it is water, it serves to cool the reactor as well- hence the name 'homogeneous' (as coolant and fuel are one homogeneous substance). The water can be either heavy water or ordinary light water.

In a gaseous fission reactor the reaction takes place in a core which is bounded and created by magnetic field. The fuel is supplied and fission occurs in the gas phase.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "Nuclear reactor - Thermal, Intermediate, Fast | Britannica". www.britannica.com. Retrieved 2023-07-19.

- Nuclear Reactor Analysis, John Wiley & Sons Canada, Ltd.

Nuclear reactor core

View on GrokipediaFundamental Principles

Nuclear Fission and Chain Reactions

Nuclear fission in reactor cores is induced primarily by the absorption of a neutron by a fissile nucleus, such as uranium-235 (^235U) or plutonium-239 (^239Pu), forming a compound nucleus that becomes unstable and splits into two lighter fission fragments of unequal mass, along with the release of typically 2 to 3 additional neutrons and energy.[6] [7] This splitting occurs when the nucleus deforms into a dumbbell shape and overcomes the fission barrier, with the probability governed by the fission cross-section; for thermal neutrons (around 0.025 eV), the fission cross-section for ^235U is approximately 584 barns, while for ^239Pu it is about 747 barns.[8] Each fission event releases roughly 200 MeV of energy, of which approximately 168 MeV appears as kinetic energy of the fission fragments, 5 MeV as prompt neutron kinetic energy, and the remainder as prompt gamma rays and beta decays; this kinetic energy is thermalized through collisions in the core, ultimately convertible to heat for power generation.[6] [9] The released neutrons enable a chain reaction, where subsequent absorptions in fissile material produce further neutrons, sustaining the process if the effective neutron multiplication factor (k_eff) satisfies certain conditions.[10] k_eff is defined as the ratio of the number of neutrons produced by fission in one generation to the number of neutrons absorbed or lost by leakage in the previous generation; a value of k_eff = 1 corresponds to a steady-state critical chain reaction, k_eff > 1 to a supercritical state with exponential neutron growth, and k_eff < 1 to a subcritical state with declining neutron population.[10] For thermal fission of ^235U, the average total number of neutrons emitted per fission is 2.435, with about 99.3% being prompt neutrons emitted directly from the fragments within approximately 10^{-14} seconds and energies averaging 2 MeV, and the remaining 0.7% as delayed neutrons emitted from the radioactive decay of fission products over seconds to minutes.[11] [9] These delayed neutrons, though few, are essential for reactor control, as they allow time for adjustments before prompt neutron-driven excursions overwhelm systems. Empirical measurements of neutron yields and cross-sections, such as those conducted at facilities like Oak Ridge National Laboratory using time-of-flight spectrometry, confirm these values with uncertainties below 0.1% for thermal spectra, underpinning reactor design calculations.[12] [13] For ^239Pu, the average neutrons per thermal fission rise to about 2.88, increasing the potential for faster chain reactions but requiring careful management of k_eff.[7]Neutron Moderation and Thermalization

Neutrons emitted from fission events possess high kinetic energies, averaging approximately 2 MeV, which result in low probabilities of inducing subsequent fissions in fissile isotopes like uranium-235 due to the energy dependence of fission cross-sections.[7] To achieve an efficient neutron economy in thermal reactors, these fast neutrons must be moderated to thermal energies around 0.025 eV, where the thermal fission cross-section for U-235 exceeds 500 barns compared to under 5 barns for fast neutrons above 1 MeV.[14] This thermalization process increases the likelihood of fission over competing absorption reactions, thereby sustaining the chain reaction with minimal fissile material requirements.[15] Moderation occurs through elastic scattering collisions between neutrons and moderator nuclei, wherein kinetic energy is transferred incrementally, with the maximum fractional energy loss per collision given by , where is the atomic mass of the moderator nucleus. Materials with low , such as hydrogen () or carbon (), enable effective slowing, requiring roughly 18 collisions for hydrogen and 114 for carbon to reduce neutron energy from 2 MeV to thermal levels. Essential moderator properties include a high macroscopic scattering cross-section relative to absorption , ensuring most neutrons scatter rather than being captured; for instance, hydrogen exhibits strong elastic scattering but also measurable absorption, while carbon provides a favorable ratio exceeding 2000 for thermal neutrons.[16] Beryllium and deuterium offer intermediate performance, balancing mass and low absorption.[17] The spatial and energetic evolution of slowing neutrons is described by the diffusion equation in the epithermal range, , where is the lethargy, the diffusion coefficient, and the continuous slowing-down approximation assumes steady energy loss governed by the average logarithmic energy decrement per collision. The Fermi age , defined as , quantifies the mean-squared radial distance traveled during moderation from fission energy to thermal , with typical values of 27 cm² in light water and 350 cm² in graphite, reflecting the longer migration and potential for leakage in heavier moderators. Light water serves as both moderator and coolant, leveraging hydrogen's superior energy transfer but incurring parasitic absorption losses from protium, which degrade neutron economy and necessitate enriched fuel for criticality. In contrast, graphite's negligible thermal absorption supports natural uranium fueling but demands larger core volumes to contain the extended slowing-down kernel, elevating leakage fractions unless reflectors are employed. These trade-offs, rooted in cross-section data from evaluated nuclear libraries, underscore moderation's causal role in optimizing reproduction factor by maximizing thermal neutron utilization while minimizing losses.[18][19]Criticality and Reactor Dynamics

Criticality in a nuclear reactor core occurs when the effective multiplication factor , defined as the ratio of neutrons produced in one fission generation to those absorbed or leaking from the previous generation, equals 1, resulting in a steady-state neutron population and constant power output.[20][21] This balance requires precise control of neutron production via fission, losses through absorption and leakage, and the mass of fissile material; subcritical states () exhibit declining neutron populations as losses exceed production, while supercritical states () lead to exponential growth until feedback or control intervenes.[22] The condition was first achieved experimentally in the Chicago Pile-1 assembly on December 2, 1942, using approximately 40 tons of graphite moderator and 6 tons of uranium metal and oxide, demonstrating that a critical chain reaction could be sustained in a moderated natural uranium system without exceeding prompt criticality.[23][24] Reactor dynamics describe the time-dependent evolution of neutron density and power following perturbations in reactivity , modeled transparently via point kinetics equations that approximate the core as spatially uniform and couple neutron balance to six (or more) groups of delayed neutron precursors.[25] These equations are: where is neutron density, are precursor concentrations, is the delayed neutron fraction for uranium-235 fission, is the prompt neutron generation time ( s in light water reactors), are decay constants, and are group yields.[22] For small , the solution yields an exponential power rise with reactor period (in the delayed neutron-dominated regime), ensuring manageable transients; for instance, a reactivity insertion of (10 pcm) produces s, allowing controlled power adjustments without prompt jumps.[26] Inherent stability arises from reactivity feedback coefficients, which couple core conditions to . The Doppler coefficient, arising from thermal broadening of fission product and fuel resonances that increases parasitic absorption with fuel temperature rise, is intrinsically negative ( to -3 pcm/K in UO fuels) and provides rapid, self-limiting response to power excursions.[27] Light water reactor designs incorporate negative moderator temperature coefficients ( to -50 pcm/K), where coolant heating reduces moderation efficiency and shifts the spectrum to higher energies, enhancing leakage and absorption; void coefficients are similarly negative ( to -1 /void fraction), as steam voids degrade moderation more than they reduce absorption in enriched fuels.[22] These negative feedbacks ensure causal self-regulation: an initial power increase triggers cooling deficits that insert negative , stabilizing output without relying solely on external controls, as validated in operational transients where combined effects yield negative power coefficients ( to -5 /% power) across light water cores. Empirical data from pressurized water reactors confirm periods of tens to hundreds of seconds for step changes equivalent to 100 MW in gigawatt-scale cores, aligning with point kinetics predictions under feedback.[26]Core Components

Fuel and Fuel Assembly

The primary fuel form in most commercial light water reactors consists of uranium dioxide (UO2) pellets enriched to 3-5 weight percent uranium-235 (U-235), the fissile isotope essential for sustaining fission chain reactions.[28][29] These cylindrical pellets, typically 8-10 mm in diameter and 10-15 mm in height with a density of about 10.5 g/cm³, are stacked within long, thin tubes to form fuel rods.[30] The cladding material is predominantly Zircaloy-4 or optimized variants like ZIRLO, zirconium alloys containing tin, niobium, and iron, selected for their low neutron absorption cross-section, mechanical strength under irradiation, and resistance to waterside corrosion via formation of a stable zirconia (ZrO2) layer.[31][32] This cladding isolates fission products while allowing heat transfer, with wall thicknesses around 0.5-0.6 mm to minimize parasitic neutron capture.[33] Mixed-oxide (MOX) fuel incorporates plutonium-239 (Pu-239), recovered via reprocessing of spent fuel, blended with depleted uranium to achieve fissile contents of 4-7% Pu (primarily Pu-239 and Pu-241) in a UO2-PuO2 matrix.[34] This enables recycling of weapons-grade or reactor-grade plutonium, reducing high-level waste volume and utilizing transuranic elements for energy production, though MOX exhibits higher fission gas release and requires adjusted isotopic tailoring for compatibility with standard UO2 designs.[35] Pellets are fabricated similarly but with enhanced sintering to accommodate plutonium's alpha decay heat and radiolytic effects, maintaining densities above 95% theoretical.[30] Fuel assemblies bundle hundreds of these rods—typically 264 in a 17x17 square lattice for pressurized water reactor (PWR) designs, including 24 guide tubes for control rods and instrumentation—held by top and bottom nozzles and spacer grids to maintain alignment and flow channels.[36] A 1000 MWe PWR core accommodates about 193 such assemblies, totaling over 50,000 rods and roughly 100 metric tons of heavy metal.[37] Material composition targets burnups of 40-60 gigawatt-days per metric ton (GWd/t), achieved through optimized U-235/Pu-239 loading gradients and gadolinium burnable absorbers in initial cycles to flatten power distribution and extend cycle length.[38] Post-irradiation examinations at research facilities like the Halden reactor verify microstructural integrity, including high-burnup structure formation (rim zone with sub-micron grains enhancing plutonium retention) up to 75 GWd/t in test rods, informing limits to prevent cladding breach from pellet-cladding interaction.[39][40]Moderator and Reflector

In thermal nuclear reactors, the moderator slows fast neutrons from fission energies (around 2 MeV) to thermal energies (below 0.025 eV) via repeated elastic collisions, thereby increasing the fission probability in isotopes like uranium-235, which has a thermal fission cross-section of approximately 584 barns compared to 1-2 barns at fast energies.[18] Effective moderators exhibit high slowing-down power (ξΣ_s, where ξ is the average logarithmic energy decrement per collision) relative to absorption (Σ_a), quantified by the moderation ratio ξΣ_s/Σ_a; graphite achieves a higher ratio than light water, enabling more efficient neutron economy despite similar scattering capabilities.[41] Light water (H₂O) is widely used for its abundance and compatibility with pressurized systems but suffers from hydrogen's relatively high absorption (Σ_a ≈ 0.022 cm⁻¹) and lower moderation efficiency, necessitating enriched fuel to compensate for losses.[18] Heavy water (D₂O) offers superior performance with deuterium's lower absorption and larger mass reducing energy loss per collision, supporting natural uranium fueling, though deuterium's scarcity raises costs.[18] Graphite provides excellent moderation (high ξ due to carbon's mass) and tolerance for temperatures up to 700°C or more, but its porosity and reactivity with oxygen pose oxidation risks under air ingress or steam exposure, potentially leading to rapid mass loss and structural degradation at rates exceeding 1 mm/h above 600°C in accidents.[42][43] Beryllium serves occasionally as a moderator in specialized designs for its low absorption and (n,2n) threshold reaction above 1.9 MeV, which generates additional neutrons, but its primary application and primary trade-offs mirror those of reflectors, including brittleness under irradiation-induced swelling.[44] The reflector encases the core to redirect leaking neutrons inward via scattering, reducing escape probability (P_leak) and thereby lowering the critical mass by minimizing the geometric buckling term in the diffusion equation; this effect can decrease fuel requirements by factors depending on thickness and material albedo, with optimal layers (e.g., 20-50 cm) balancing return flux against self-absorption.[45][46] Materials like beryllium, graphite, or light water are chosen for high scattering-to-absorption ratios; beryllium's advantages include exceptional albedo (up to 0.9 for thermal neutrons) from dense atomic packing and elastic scattering dominance, plus modest neutron multiplication, though high cost (over $500/kg) and dust toxicity limit adoption.[45][44][47] Irradiation stability remains a key constraint: moderators and reflectors endure fast neutron fluences exceeding 10²¹ n/cm² over lifetimes, inducing anisotropic shrinkage in graphite (up to 2-5% dimensional change) or transmutation helium in beryllium (causing embrittlement), requiring pre-irradiation testing and design margins for creep and fracture.[17] These materials thus trade neutronics performance against manufacturability, safety in off-normal chemistry, and waste generation from activated isotopes like C-14 in graphite or Be-10.[48]Control Rods and Poison Systems

Control rods consist of neutron-absorbing materials, such as boron carbide (B₄C), silver-indium-cadmium alloy, or hafnium, encased in cladding to prevent interaction with the coolant or moderator.[49][50] These materials capture thermal neutrons via high cross-section reactions, reducing the neutron multiplication factor (k_eff) and thereby controlling the fission chain reaction rate.[49] Rods are positioned in guide tubes within the core, driven by mechanisms that allow precise axial movement for reactivity adjustment during operation.[51] In emergency conditions, the scram system rapidly inserts all control rods into the core, typically within 2-4 seconds in pressurized water reactors (PWRs), dropping k_eff below 1.0 to achieve subcriticality. This gravity-assisted or spring-driven insertion terminates the chain reaction promptly, with the total reactivity worth from full rod insertion providing a shutdown margin of approximately 5-10% Δk/k in typical light water reactor (LWR) designs, though individual rod or group worths vary from 1-4% Δk depending on core position and burnup.[52][53] Soluble boron, introduced as boric acid in PWR coolant, serves as a chemical shim for fine reactivity control and long-term fuel cycle compensation, with concentrations adjusted via dilution or boration to maintain criticality without excessive rod motion.[54] Boron-10 isotope dominates neutron capture, enabling uniform absorption across the core volume, though its effectiveness diminishes at higher burnups due to transmutation.[54] Burnable poisons, such as gadolinium oxide (Gd₂O₃) or erbium oxide (Er₂O₃) integrated into fuel pellets or discrete rods, counteract initial excess reactivity from fresh fuel, gradually depleting via neutron capture and fission product decay to shape the neutron flux profile and extend cycle length.[55][56] These additives, with high initial absorption cross-sections (e.g., Gd-155 and Gd-157 isotopes exceeding 20,000 barns), burn out over the fuel cycle, minimizing power peaking.[55] Transient fission product poisons, notably xenon-135 (Xe-135) with a thermal neutron cross-section of about 2.6 million barns, accumulate post-shutdown from iodine-135 decay, peaking around 10 hours after reactor trip and inserting negative reactivity equivalent to 1-2% Δk/k at equilibrium under full power conditions, potentially delaying restarts.[57] Xe-135 concentration builds during operation but surges after scram due to continued precursor decay without fission removal, requiring careful monitoring for flux oscillations.Coolant and Structural Elements

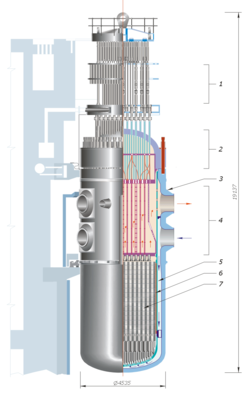

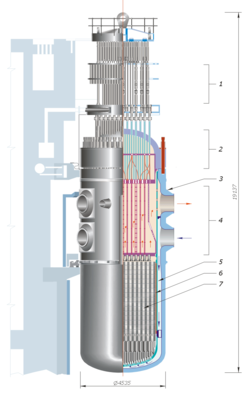

In pressurized water reactors (PWRs), the coolant consists of light water maintained at a pressure of approximately 15.5 MPa and temperatures around 300°C to prevent boiling while extracting fission heat from the core.[58] [59] This high pressure ensures the water remains in liquid phase, facilitating efficient heat transfer to a secondary steam cycle without direct steam generation in the core.[18] In boiling water reactors (BWRs), the coolant water boils directly within the core at lower pressures of about 7 MPa, producing a steam-water mixture that drives turbines after separation.[60] [61] For sodium-cooled fast reactors, liquid sodium serves as the coolant, operating at atmospheric pressure with inlet temperatures around 350°C and outlet temperatures of 500–550°C, enabling higher thermal efficiencies due to elevated operating conditions.[62] [63] Sodium's low neutron absorption and excellent thermal conductivity support fast neutron spectra without moderation, though its reactivity with air and water necessitates inert atmospheres and double-loop designs.[64] Core structural elements, such as support grids, core barrels, and flow distributors, are typically constructed from austenitic stainless steels like types 304 and 316 to withstand high temperatures, corrosive coolants, and neutron-induced embrittlement.[65] [66] These materials provide mechanical integrity under radiation doses exceeding 10^{21} n/cm² while minimizing activation products.[67] In advanced gas-cooled reactors (AGRs), graphite-moderated cores incorporate stainless steel flow channels to direct CO2 coolant axially through fuel elements, enhancing heat removal uniformity.[18] Coolant systems are designed to manage heat fluxes typically limited to 0.5–1 MW/m² in operating conditions to maintain margins against critical heat flux (CHF), where boiling transitions to film boiling, potentially leading to cladding overheating; CHF values exceed 3 MW/m² in tested configurations but are conservatively derated based on empirical thermal-hydraulic data from facilities like those referenced in NRC analyses.[68] [69] Structural components resist void formation and flow-induced vibrations, ensuring stable heat transfer under nominal and transient loads.[70]Historical Development

Pioneering Experiments (1930s-1940s)

The discovery of nuclear fission occurred in December 1938 when chemists Otto Hahn and Fritz Strassmann at the Kaiser Wilhelm Institute in Berlin bombarded uranium with neutrons and chemically identified lighter elements, including barium, indicating the nucleus had split into fragments.[71][72] This empirical observation, later theoretically explained by Lise Meitner and Otto Robert Frisch as fission releasing energy and neutrons, provided the basis for potential self-sustaining chain reactions.[71] Leo Szilard, recognizing the implications for neutron multiplication, had conceived the concept of a controlled chain reaction earlier in the 1930s and collaborated with Enrico Fermi to develop practical methods using natural uranium.[73] In 1939, Szilard and Fermi filed a patent application for a device employing uranium and a moderator like graphite to achieve neutron-induced fission chains, though the patent was not granted until 1955 after secrecy restrictions were lifted. Their work emphasized empirical verification of the effective neutron multiplication factor (k) exceeding unity, requiring separation of fission neutrons from those absorbed or lost. To test chain reaction feasibility subcritically, Fermi's team constructed exponential piles—stacked assemblies of uranium and graphite layers—to measure neutron multiplication without achieving criticality. These experiments, involving over 30 iterations, quantified k values approaching but below 1, identifying graphite's role in slowing fast neutrons to energies more likely to induce fission in uranium-235 while overcoming natural uranium's parasitic absorption. Culminating in Chicago Pile-1 (CP-1), assembled under the west stands of the University of Chicago's Stagg Field, the stack comprised approximately 40 tons of natural uranium (in metal and oxide forms) embedded in 385 tons of graphite bricks, with cadmium-covered wooden rods for neutron absorption and control.[74][23] On December 2, 1942, Fermi's team withdrew control rods incrementally, achieving the world's first self-sustaining chain reaction at a power level of 0.5 watts, demonstrating k ≈ 1.0006 and confirming controlled fission feasibility with natural fuel.[74][23] Cadmium absorbers enabled precise regulation, averting exponential power growth, while manual and emergency insertion mechanisms provided shutdown capability.[74]Early Power Reactors (1950s-1960s)

The Experimental Breeder Reactor-I (EBR-I), a sodium-cooled fast reactor located in Idaho, achieved the first production of usable electricity from nuclear fission on December 20, 1951, initially powering four 200-watt light bulbs through a connected generator.[75] This 1.4 MWt prototype marked the engineering proof-of-concept for converting fission heat to electrical power, though its output remained experimental and far below grid-scale requirements.[76] In 1954, the Soviet Union's Obninsk Nuclear Power Plant, featuring a graphite-moderated, water-cooled reactor design, became the first to connect nuclear-generated electricity to a public grid, delivering 5 MWe starting in June.[77] This facility scaled reactor operations to sustained network integration, operating until 2002 and validating channel-type graphite moderation for power generation.[78] The United States followed with the Shippingport Atomic Power Station, a pressurized water reactor that attained criticality on December 2, 1957, and produced 60 MWe for civilian use, establishing the first full-scale, peacetime nuclear power plant.[79][80] Designed by Westinghouse, it utilized highly enriched uranium oxide fuel and demonstrated reliable steam cycle integration, operating until 1982 and informing subsequent PWR developments.[81] The Dresden Unit 1 boiling water reactor, commissioned in 1960 near Morris, Illinois, represented an early direct-cycle alternative, generating approximately 200 MWe by circulating boiling water through the core to drive turbines without intermediate heat exchangers.[82] This General Electric design highlighted simpler system architecture but required advances in steam separation and dryers to achieve efficient power output.[83] By 1964, the Experimental Breeder Reactor-II (EBR-II), another sodium-cooled fast reactor at Argonne National Laboratory, entered operation at 62.5 MWt and 20 MWe, successfully demonstrating breeding ratios exceeding 1.0 through on-site metallic fuel reprocessing and integral testing of fast-spectrum physics.[84][85] It operated for three decades, providing data on sodium coolant handling and fuel cycle closure absent in thermal reactors.[86] Prototypes in this era encountered frequent fuel element failures, including cladding breaches from corrosion, hydriding, and pellet-cladding interaction in water-moderated designs, often linked to initial use of stainless steel or uranium-zirconium hydride fuels susceptible to oxidation and fission gas buildup.[87] These issues, evident in early Shippingport and Dresden cores, prompted material refinements; zircaloy alloys, developed from 1950s naval applications for their low neutron capture and aqueous corrosion resistance, became standard cladding by the mid-1960s, reducing failure rates and enabling higher burnups.[88][89]Commercial Expansion and Standardization (1970s-present)

The 1973 oil crisis, triggered by OPEC's embargo and resulting in quadrupled petroleum prices, catalyzed a global surge in nuclear reactor construction as governments sought to mitigate dependence on imported fossil fuels for electricity generation. Nations including France launched ambitious programs, with France's "Messmer Plan" committing to 13 gigawatt-scale reactors by 1980, expanding to over 50 by the decade's end to supply baseload power. This expansion propelled the number of operational reactors worldwide from around 100 in 1973 to more than 400 by the late 1980s, predominantly light water reactors (LWRs) in the 600-1200 MWe range, emphasizing pressurized water reactor (PWR) designs for their proven thermal efficiency and safety margins. The 1979 Three Mile Island Unit 2 partial meltdown, caused by a stuck valve and operator errors leading to core damage affecting about half the fuel, prompted stringent safety enhancements without halting overall deployment. U.S. Nuclear Regulatory Commission mandates post-accident included upgraded instrumentation for better accident diagnostics, enhanced operator training via full-scope simulators, and additions like recirculation pumps in PWRs to restore coolant flow during loss-of-coolant events, reducing vulnerability to beyond-design-basis scenarios. These reforms, informed by probabilistic risk assessments, contributed to LWR standardization, with Westinghouse's PWR variants—such as the 1000 MWe-class systems featuring standardized fuel assemblies and steam generators—achieving widespread adoption for their modular scalability and regulatory familiarity, influencing over 60% of global PWR capacity.[90][91] By 2025, roughly 440 reactors provide approximately 10% of global electricity, with optimized plants routinely exceeding 90% capacity factors through refined fuel management and maintenance protocols that minimize outages. Standardization has sustained LWR dominance, though diversification includes China's CFR-600 sodium-cooled fast reactor, which reached initial low-power operation in 2023 to demonstrate closed-fuel-cycle viability amid uranium resource constraints.[92][93][94]Major Types of Reactor Cores

Light Water Moderated Cores

Light water moderated cores utilize ordinary (light) water as both moderator and coolant, enabling thermal neutron spectra that efficiently fission uranium-235 while integrating with conventional steam turbine cycles for electricity generation. These designs dominate commercial nuclear power, comprising approximately 85% of operating reactors worldwide due to their established neutron economy, safety record, and compatibility with existing power infrastructure.[18] Pressurized water reactors (PWRs) and boiling water reactors (BWRs) represent the primary variants, with PWRs accounting for the majority of light water deployments. In PWR cores, water is maintained at high pressure (typically 15-16 MPa) to prevent boiling, ensuring stable moderation and heat transfer. Fuel assemblies consist of uranium dioxide (UO₂) pellets clad in zircaloy tubes, arranged in square lattices such as the standard 17×17 configuration with 264 fuel rods, 24 control rod guide tubes, and one instrument tube per assembly.[95] Reactivity control incorporates soluble boron (as boric acid) dissolved in the coolant for long-term compensation of fuel burnup and xenon buildup, supplemented by solid burnable absorbers like gadolinia in select rods. Typical fuel cycles last 18-24 months, achieving discharge burnups of 40-60 GWd/tU, with overall plant thermal efficiencies around 33%.[96] Advanced PWRs, such as the AP1000, incorporate passive core cooling systems relying on natural circulation, gravity-driven flow, and heat exchangers for decay heat removal without active pumps or external power for up to 72 hours post-shutdown.[97] BWR cores permit boiling within the vessel at lower pressures (around 7 MPa), generating steam directly for the turbine while moderating neutrons with the two-phase water-void mixture. Operating void fractions reach 12-15% in the upper core, introducing a negative void reactivity coefficient that enhances stability by reducing reactivity as voids increase, though it requires careful axial power shaping to manage.[18] Steam-water separation occurs via internal cyclones and dryers in the vessel, minimizing carryover to turbines. Fuel assemblies typically feature 8×8 or 9×9 UO₂ rod arrays with water channels for enhanced cooling, and reactivity is controlled primarily via rod insertion and flow rate adjustments rather than chemical shims. Cycle lengths mirror PWRs at 18-24 months, with similar efficiencies of about 33%, though void dynamics demand precise subchannel analysis for thermal margins.[98]Heavy Water and Graphite Moderated Cores

Heavy water (D₂O) and graphite serve as neutron moderators in thermal reactor cores, enabling the use of natural uranium fuel due to their low thermal neutron absorption cross-sections compared to light water, which necessitates uranium enrichment for criticality.[18][99] Heavy water provides superior moderation efficiency, allowing smaller core sizes and higher neutron economy, but its production is energy-intensive and costly, approximately 20-30 times more expensive than light water.[99] Graphite, while cheaper and abundant, requires a larger moderator volume for equivalent slowing-down power and introduces risks such as radiolytic gas buildup and potential ignition under fault conditions.[100] Heavy water moderated cores, as in the CANDU (CANada Deuterium Uranium) design, employ a pressure tube architecture where individual Zr-Nb alloy tubes contain fuel and pressurized heavy water coolant, separated from the surrounding low-pressure heavy water moderator in a calandria vessel.[101] This configuration permits on-power refueling via remote robotic insertion and removal of fuel bundles, minimizing downtime and enabling continuous operation with natural uranium dioxide pellets achieving average burnups of 7-10 MWd/kgU per bundle over 7-12 equivalent full-power months before discharge. However, the deuterium in heavy water captures neutrons to produce tritium via the reaction ²H(n,γ)³H, resulting in annual inventories of several kilograms per reactor, necessitating extraction systems and raising proliferation concerns due to tritium's utility in fusion or boosted fission weapons.[102] Graphite moderated cores utilize stacked blocks of high-purity graphite to form channels for fuel and coolant, as seen in designs like the British Magnox reactors, which operated on natural uranium metal clad in magnesium alloy, graphite moderation, and CO₂ gas cooling at pressures up to 7 bar.[103] Successor Advanced Gas-cooled Reactors (AGR) improved efficiency with stainless-steel-clad enriched uranium dioxide fuel (2-3.5% ²³⁵U), higher CO₂ pressures (40 bar), and steam generators, but retained graphite's bulkiness and required offline refueling every 3-4 years.[104] The Soviet RBMK type, with ~1,700 tons of graphite blocks per 1,000 MW unit, used light water coolant in pressure channels amid the moderator, but exhibited a positive void coefficient—where coolant boiling reduced moderation and increased reactivity—contributing to instability, as evidenced by the 1986 Chernobyl explosion.[105] Graphite's combustibility under oxidizing conditions poses inherent risks, exemplified by the 1957 Windscale Pile 1 fire, where an air-cooled graphite-moderated plutonium production reactor in the UK experienced a three-day blaze after fuel cartridge ignition during Wigner energy release, releasing ~740 TBq of iodine-131 and prompting milk bans over 200 square miles.[106] Overall, heavy water offers greater fuel flexibility and safety margins against voiding but at higher capital costs, while graphite enables simpler natural uranium cycles in gas-cooled variants yet demands stringent fire prevention and has been largely phased out in water-cooled forms due to reactivity flaws.[18]Fast Neutron and Breeder Cores

Fast neutron reactor cores operate without moderators, sustaining fission chains with high-energy neutrons averaging above 1 MeV, which results in a harder neutron spectrum compared to thermal reactors and enables higher fissile utilization from materials like uranium-238.[107] These cores typically feature compact designs with high power density, fueled by plutonium-uranium mixed oxide (MOX) or metallic alloys enriched to 15-20% plutonium in the driver zone to initiate and maintain the reaction.[107] The absence of moderation preserves neutron economy, allowing for potential breeding where more fissile material is produced than consumed.[107] Breeder cores, a subset of fast neutron designs, achieve a breeding ratio greater than 1 by surrounding the central driver fuel region—containing high-plutonium content for criticality—with radial and axial blankets of fertile uranium-238, which captures neutrons to produce plutonium-239.[107] This layout supports a closed fuel cycle, theoretically extending uranium resources by utilizing the abundant 99.3% U-238 fraction beyond the 0.7% U-235 in natural uranium.[107] Sodium-cooled fast reactors (SFRs) dominate historical designs due to sodium's excellent thermal conductivity and low neutron absorption, though alternatives like lead or lead-bismuth eutectic offer reduced chemical reactivity with air and water, while helium gas cooling provides high-temperature operation without liquid metal corrosion risks.[107] [108] The French Phénix SFR exemplified breeder operation, achieving a breeding ratio of approximately 1.16—producing 16% more fissile material than consumed—during its 35-year run from 1973 to 2009, validating closed-cycle feasibility in a 250 MWe pool-type configuration.[107] Similarly, the U.S. Experimental Breeder Reactor-II (EBR-II), operational from 1964 to 1994, demonstrated inherent safety through negative reactivity feedback from thermal expansion and Doppler broadening, successfully shutting down passively during 1986 loss-of-flow and loss-of-heat-sink tests without active intervention or scram.[109] [110] These tests underscored how fast spectrum cores can self-regulate power via inherent physics, reducing reliance on engineered safeguards.[109]Advanced and Experimental Designs

The AVR reactor, a 46 MWth prototype pebble-bed high-temperature gas-cooled reactor in Jülich, Germany, operated from 1967 to 1988 and tested spherical graphite fuel pebbles containing thousands of TRISO-coated fuel particles for enhanced fission product retention and higher burnup.[111][112] These TRISO particles, consisting of a uranium oxide kernel surrounded by porous carbon, pyrolytic carbon, and silicon carbide layers, demonstrated robustness under high temperatures exceeding 1600°C without melting, enabling safer containment of radioactive byproducts compared to traditional fuel rods.[113] The pebble geometry facilitated online refueling by recirculating spheres through the core, achieving pebble burnups up to 15% and outlet coolant temperatures of 950°C, which supported testing of helium cooling efficiency for process heat applications.[111] Building on AVR experience, the THTR-300, a 300 MWe thorium-high-temperature reactor in Hamm-Uentrop, West Germany, incorporated similar pebble-bed design with TRISO particles but scaled for commercial viability, entering commercial operation in 1985 after initial grid connection in 1983.[114] It utilized thorium-uranium mixed oxide fuel in pebbles to leverage thorium's abundance and potential for breeding, though operational challenges including a 1986 fuel handling incident led to shutdown in 1989 after accumulating over 16,000 hours.[115][116] These prototypes validated pebble circulation for reducing refueling downtime and improving fuel utilization efficiency over fixed-fuel geometries.[112] The Molten Salt Reactor Experiment (MSRE) at Oak Ridge National Laboratory operated from 1965 to 1969 as a 7.4 MWth prototype demonstrating liquid fluoride salt as both fuel carrier and coolant, using a FLiBe (lithium-beryllium fluoride) mixture enriched with uranium-233 or uranium-235 tetrafluoride dissolved at 650°C.[117][118] This design eliminated solid fuel elements, enabling continuous online reprocessing to remove fission products like xenon and samarium via chemical separation, potentially extending fuel cycles and minimizing waste compared to solid-fuel reactors.[119] The core's graphite-moderated geometry operated at low pressure (about 10 psi) with inherent safety from salt's high boiling point and negative reactivity coefficients, though corrosion challenges with Hastelloy-N alloy required ongoing materials research.[120] MSRE achieved 13,000 hours of operation, validating molten salt stability under irradiation for higher thermal efficiency up to 44%.[117]Operational Characteristics

Heat Generation and Power Output

Heat generation in a nuclear reactor core primarily arises from the fission of heavy nuclei, such as uranium-235 or plutonium-239, where each fission event releases approximately 200 MeV of recoverable thermal energy, predominantly in the form of kinetic energy of fission fragments that is promptly thermalized within the fuel matrix.[121] This energy deposition occurs volumetrically, proportional to the local neutron flux, fission cross-section, and fissile atom density, with the total core heat output determined by the integrated fission rate across the core volume. In practice, the fissioning of 1 gram of fissile material corresponds to roughly 1 megawatt-day of thermal energy production.[121] For light water reactors (LWRs), which dominate commercial deployment, average core power densities typically range from 90-100 kW per liter of core volume, enabling compact designs with total thermal outputs of 2,500-3,500 MWth in large pressurized water reactors (PWRs). Individual fuel pins in PWRs operate at linear heat generation rates of up to 25-30 kW per meter of active fuel length, with peak values limited to avoid cladding damage, though assembly-level powers reach several megawatts thermal due to the bundling of 200-300 pins per assembly. Power distributions exhibit non-uniformity due to neutron flux gradients; radial peaking factors, defined as the ratio of maximum to average radial power density, are typically around 1.4-1.6 in equilibrium cycles, arising from edge-to-center flux increases and mitigated through fuel assembly shuffling, burnable absorbers, and control rod positioning.[122] The core's thermal power is transferred via coolant to a secondary steam cycle, achieving thermal-to-electric conversion efficiencies of 33-37% in PWRs and boiling water reactors (BWRs), constrained by coolant outlet temperatures of 300-330°C and Rankine cycle thermodynamics.[123] This yields net electrical outputs peaking at approximately 1,600 MWe per unit in advanced designs like the EPR, with thermal powers exceeding 4,500 MWth, though most operational PWRs deliver 900-1,200 MWe from cores with volumes of 30-40 cubic meters.[18] Axial flux distributions often follow a cosine-like profile with peaking factors of 1.3-1.5, further shaped by reflector effects and end-of-cycle xenon buildup, ensuring overall core heat extraction remains balanced against design limits.[122]Fuel Cycle and Burnup

The nuclear fuel cycle in reactor cores encompasses the staged irradiation of enriched uranium assemblies, where fresh fuel is loaded and progressively depleted to extract maximum energy before discharge, balancing reactivity through periodic partial replacement. In typical pressurized water reactors, an initial core achieves equilibrium after several cycles by replacing about one-third of assemblies with fresh fuel every 12 to 24 months, stabilizing the average isotopic composition and power distribution across the core.[18] This batch approach compensates for the reactivity loss from fissile depletion, enabling continuous operation without full-core unloading. During irradiation, isotopic evolution drives the cycle's dynamics: uranium-235 fissions or captures neutrons, depleting to below 1% of initial content, while uranium-238 captures neutrons to form plutonium-239, which sustains fission contributions up to 30-40% of total energy in high-burnup fuel. Successive captures yield higher plutonium isotopes and minor actinides, including neptunium-237 (from U-237 beta decay) and americium-241 (from Pu-241 decay), accumulating to 0.5-1% of heavy metal mass and influencing delayed neutron fractions and long-term decay heat.[124][125] These buildups necessitate burnable poisons like gadolinium in initial loads to suppress excess reactivity from plutonium generation. Burnup quantifies this energy extraction, expressed in gigawatt-days per tonne of heavy metal (GWd/tHM), reflecting fission of both initial and bred fissiles. Early light water reactor designs in the 1960s-1970s targeted 20-25 GWd/tHM due to cladding and pellet stability limits, but optimizations in enrichment (to 4-5% U-235), fuel geometry, and materials have elevated average discharge burnups to 50 GWd/tHM in U.S. reactors by the 2020s, with advanced assemblies reaching 60-70 GWd/tHM.[18][126] Higher values enhance fuel efficiency by 50-100% over historical norms, reducing refueling frequency and uranium demands. Fuel burnup remains capped by cladding constraints, as solid fission products (e.g., xenon, ruthenium) and gaseous ones (e.g., krypton, xenon) induce pellet volumetric swelling at 2-3% per 10% burnup, closing the initial 100-200 μm pellet-cladding gap after 20-30 GWd/tHM and exerting hoop stresses up to 200 MPa.[126] Subsequent pellet-cladding mechanical interaction risks hydrogen embrittlement or breach, particularly beyond 60 GWd/tHM without zircaloy alloys enhanced for creep resistance or alternative claddings like silicon carbide.[127] Closed fuel cycles via reprocessing recover usable actinides from discharged fuel, with facilities like France's La Hague plant extracting 95% uranium and 1% plutonium—totaling 96% recyclable material—through PUREX solvent extraction, enabling MOX fabrication and resource extension by factors of 20-30 over once-through use.[35][128] This contrasts open cycles, where actinide buildup in spent fuel limits effective burnup realization without recycling.Refueling and Maintenance

Refueling of nuclear reactor cores entails the controlled replacement of depleted fuel assemblies with fresh ones to replenish fissile material, maintain criticality, and optimize energy extraction, typically performed during scheduled outages to minimize operational disruptions. In light water reactors (LWRs), such as pressurized water reactors (PWRs) and boiling water reactors (BWRs), this process occurs at intervals of 18 to 24 months, with outage durations averaging 35 to 38 days in recent U.S. operations, allowing for partial fuel shuffling where one-third to one-quarter of the core is replaced per cycle.[129][130] Specialized robotic fuel handling systems, including mast-mounted manipulators and underwater transfer mechanisms, enable precise loading and unloading within the reactor vessel under flooded conditions to shield radiation.[131] Heavy water moderated designs like CANDU reactors incorporate pressure tube architecture that permits on-power refueling, where individual fuel channels are accessed sequentially using automated fueling machines without requiring full core shutdown, sustaining continuous operation and achieving near-100% availability during refueling activities.[132][133] This approach contrasts with LWR batch refueling and supports extended fuel burnup through frequent, localized adjustments to reactivity. Maintenance activities coincide with refueling outages and encompass in-service inspections (ISI) mandated by ASME Boiler and Pressure Vessel Code Section XI, which prescribe volumetric, surface, and ultrasonic examinations of core components for degradation such as cracking or corrosion.[134][135] Eddy current testing is applied particularly to detect flaws in fuel cladding or steam generator tubing, providing non-destructive quantification of defects to inform repair or replacement decisions.[136][137] These protocols ensure structural integrity and preempt failures, contributing to nuclear plants' average capacity factors of approximately 92% in the U.S. during the 2020s—far exceeding the 25-35% typical for wind and solar due to intermittency—thus underscoring the reliability enabled by infrequent, efficient core interventions.[138][139][140]Safety Features and Risk Assessment

Inherent and Passive Safety Mechanisms

Inherent safety mechanisms in nuclear reactor cores rely on intrinsic physical properties that self-regulate reactivity excursions without requiring operator action or external systems. A primary example is the negative Doppler coefficient of reactivity, arising from the Doppler broadening of neutron absorption resonances in uranium-238 as fuel temperature rises; this effect increases the effective cross-section for neutron capture, inserting negative reactivity and suppressing power increases during transients.[141] In light-water reactors, the negative coolant void coefficient further contributes, as steam void formation reduces moderation density more than it decreases absorption, hardening the neutron spectrum and lowering overall reactivity.[105] Passive safety mechanisms, by contrast, employ gravity, natural convection, and thermal gradients to achieve cooling and shutdown without active power or pumps. These include natural circulation loops that drive coolant flow via density differences induced by heating, enabling decay heat removal even after loss of forced circulation. In the AP1000 pressurized water reactor design, the passive core cooling system uses elevated water storage tanks to gravity-feed borated water into the core, followed by natural circulation in the residual heat removal heat exchanger to condense steam and reject heat to the containment atmosphere.[142][143] Following shutdown, fission product decay generates residual heat initially equivalent to approximately 6-7% of the core's rated thermal power, decaying to about 1% within hours; this heat can be managed passively through conduction to structural components, radiation to surrounding coolant, and buoyancy-driven convection in pool-type or integral designs.[144] Demonstration of these combined inherent and passive features occurred in the Experimental Breeder Reactor-II (EBR-II), a sodium-cooled fast reactor, where 1986 tests successfully withstood unprotected loss-of-flow and loss-of-heat-sink transients from full power; negative reactivity feedbacks from fuel axial expansion, Doppler effects, and sodium voiding stabilized the core without scram or damage, peaking temperatures below safety limits.[145][146]Accident Scenarios and Mitigation

A loss-of-coolant accident (LOCA) occurs when a breach in the reactor's pressure boundary allows coolant to escape at a rate exceeding the system's makeup capability, potentially leading to core uncovery and fuel overheating if not addressed.[147] In light-water reactors, this can initiate zirconium-water reactions producing hydrogen gas and, without intervention, progress to clad breach and partial fuel melting.[148] Mitigation relies on the emergency core cooling system (ECCS), which injects borated water via high- and low-pressure pumps to reflood the core and remove decay heat, preventing widespread damage as demonstrated in design-basis analyses.[149] Anticipated transients without scram (ATWS) represent scenarios where a transient event, such as a loss of feedwater or turbine trip, occurs without successful control rod insertion to shut down the reactor, potentially causing power excursions and pressure buildup.[150] In pressurized water reactors, inherent negative feedback from Doppler broadening and moderator temperature coefficients limits reactivity insertion, while backup shutdown mechanisms like boric acid injection or diverse scram systems provide redundancy.[151] Prompt criticality, a rapid power surge driven solely by prompt neutrons, remains rare in commercial reactors due to low fuel enrichment levels (typically under 5% U-235), which require an reactivity excess exceeding the delayed neutron fraction (about 0.0065) that designs actively avoid through subcritical margins and geometric constraints.[152] The 1979 Three Mile Island Unit 2 accident exemplified a small-break LOCA compounded by valve mispositioning and operator errors, resulting in approximately 50% core melting over several hours but containment of fission products within the vessel due to delayed ECCS activation and natural circulation.[153] No significant off-site radiation release occurred, as the partial melt solidified without breaching the reactor pressure vessel.[90] In contrast, the 1986 Chernobyl disaster involved an RBMK reactor's unique positive void coefficient and graphite-tipped control rods, which displaced coolant and accelerated reactivity during a low-power test, leading to a steam explosion, graphite moderator fire, and massive radionuclide release—conditions not replicable in water-moderated Western designs lacking graphite ignition risks.[154] Post-2011 Fukushima Daiichi events, where station blackout disabled ECCS pumps and led to hydrogen accumulation from zircaloy oxidation, prompted enhancements including passive autocatalytic recombiners (PARs) to catalytically recombine hydrogen and oxygen, reducing explosion risks in containment without active power.[155] Operator actions, such as manual valve alignments and seawater injection, further mitigated core degradation in affected units, underscoring the role of trained response in beyond-design-basis scenarios alongside engineered barriers like core catchers in modern vessels.[156] Western reactors have experienced no Chernobyl-scale core releases, attributable to robust negative reactivity coefficients and multiple independent safety trains.[157]Statistical Safety Record Compared to Alternatives

Nuclear power exhibits one of the lowest mortality rates per unit of electricity generated, at approximately 0.03 deaths per terawatt-hour (TWh), a figure that incorporates fatalities from operational incidents, occupational hazards, and the Chernobyl disaster's acute and projected long-term effects.[158] This rate reflects data spanning decades of global deployment, where air pollution contributes negligibly to nuclear's tally unlike fossil fuels, emphasizing accident risks that remain rare even in major events.[159] In contrast, fossil fuel sources dominate higher-risk profiles: coal at 24.6 deaths per TWh, driven predominantly by particulate matter and respiratory diseases from combustion emissions; oil at 18.4 deaths per TWh; and natural gas at 2.8 deaths per TWh.[158] Among low-carbon alternatives, hydroelectricity records 1.3 deaths per TWh, attributable to rare but severe dam failures causing drownings and structural collapses.[158] Wind energy aligns closely with nuclear at 0.04 deaths per TWh, while solar photovoltaic systems, particularly rooftop installations, register 0.02 deaths per TWh, elevated by falls and electrical accidents during deployment rather than generation.[158] The following table summarizes these normalized death rates, drawn from meta-analyses of empirical studies on accidents, pollution, and occupational exposures:| Energy Source | Deaths per TWh |

|---|---|

| Coal | 24.6 |

| Oil | 18.4 |

| Natural Gas | 2.8 |

| Hydro | 1.3 |

| Wind | 0.04 |

| Solar (rooftop) | 0.02 |

| Nuclear | 0.03 |