Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

River Shannon

View on Wikipedia

| River Shannon | |

|---|---|

River Shannon from Drumsna bridge, County Leitrim | |

River Shannon watershed (Interactive map) | |

| |

| Native name | Abhainn na Sionainne (Irish) |

| Location | |

| Country | Ireland |

| Counties | Cavan, Leitrim, Longford, Roscommon, Westmeath, Offaly, Tipperary, Galway, Clare, Limerick, Kerry |

| Physical characteristics | |

| Source | Shannon Pot |

| • location | Glangevlin, Cuilcagh Mountain, County Cavan |

| • coordinates | 54°14′06″N 7°55′12″W / 54.235°N 7.92°W |

| • elevation | 100 |

| Mouth | Shannon Estuary |

• location | Limerick |

• coordinates | 52°39′25″N 8°39′36″W / 52.657°N 8.66°W |

| Length | 360 kilometres (220 mi) |

| Discharge | |

| • maximum | 300 cubic metres per second (11,000 cu ft/s) |

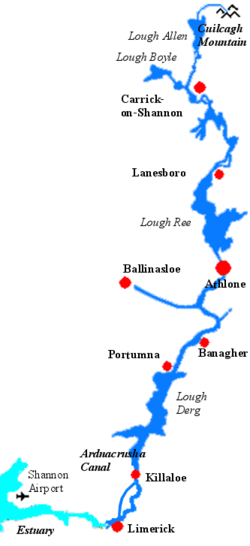

The River Shannon (Irish: an tSionainn, Abhainn na Sionainne or archaic an tSionna[1]) is the major river on the island of Ireland, and at 360 km (224 miles) in length,[2] is the longest river in the British Isles.[3][4] It drains the Shannon River Basin, which has an area of 16,900 km2 (6,525 sq mi),[5] – approximately one fifth of the area of Ireland.

Known as an important waterway since antiquity, the Shannon first appeared in maps by the Graeco-Egyptian geographer Ptolemy (c. 100 – c. 170 AD). The river flows generally southwards from the Shannon Pot in County Cavan before turning west and emptying into the Atlantic Ocean through the 102.1 km (63.4 mi) long Shannon Estuary.[6] Limerick city stands at the point where the river water meets the sea water of the estuary. The Shannon is tidal east of Limerick as far as the base of the Ardnacrusha dam.[7] The Shannon divides the west of Ireland (principally the province of Connacht) from the east and south (Leinster and most of Munster; County Clare, being west of the Shannon but part of the province of Munster, is the major exception.) The river represents a major physical barrier between east and west, with fewer than thirty-five crossing points between the village of Dowra in the north and Limerick city in the south.

Course

[edit]By tradition the Shannon is said to rise in the Shannon Pot, a small pool in the townland of Derrylahan on the slopes of Cuilcagh Mountain in County Cavan, Republic of Ireland, from where the young river appears as a small trout stream. Surveys have defined a 12.8 km2 (4.9 sq mi) immediate pot catchment area covering the slopes of Cuilcagh. This area includes Garvah Lough, Cavan, 2.2 km (1.4 mi) to the northeast, drained by Pollnaowen.[n 1] Further sinks that source the pot include Pollboy and, through Shannon Cave, Pollahune in Cavan and Polltullyard and Tullynakeeragh in County Fermanagh, Northern Ireland. The highest point in the catchment is a spring at Tiltinbane on the western end of the Cuilcagh mountain ridge.[8]

From the Shannon Pot, the river subsumes a number of tributaries before replenishing Lough Allen at its head.[9] The river runs through or between 11 of Ireland's counties, subsuming the tributary rivers Boyle, Inny, Suck, Mulkear and Brosna, among others, before reaching the Shannon Estuary at Limerick.

Many different values have been given for the length of the Shannon. A traditional value is 390 km (240 mi).[10] An official Irish source gives a total length of 360.5 km (224.0 mi) (being 258.1 km [160.4 mi] fresh and 102.1 km [63.4 mi] tidal).[6] Some Irish guides now give 344 km (214 mi).[11][12][13] Some academic sources give 280 km (170 mi),[14] although most will refuse to give a number. The reason is that there is no particular end to a river that empties into an estuary. The 344 km length relates to the distance between Shannon Pot and a line between Kerry Head and Loop Head, the furthest reaches of the land. (It also assumes the current shipping route via Ardnacrusha, which takes 7 km (4.3 mi) off the distance.) The 280 km distance finishes where the Shannon estuary joins the estuary of the River Fergus, close to Shannon Airport. Longer claimed lengths emerged before the use of modern surveying instruments.

At a total length of 360.5 km (224 miles), it is the longest river in Ireland.[13] That the Shannon is the longest river in the British Isles was evidently known in the 12th century, although a map of the time showed this river as flowing out of the south of Ireland.[3]

There are some tributaries within the Shannon River Basin which have headwaters that are further in length (from source to mouth) than the Shannon Pot source's length of 360.5 km (224 miles), such as the Owenmore River, total length 372 km (231 mi) in County Cavan[15] and the Boyle River, total length 392.1 km (243.6 mi) with its source in County Mayo.[16]

The River Shannon is a traditional freshwater river for about 45% of its total length. Excluding the 102 km (63+1⁄2 mi) tidal estuary from its total length of 360 km (224 mi), if one also excludes the lakes (L. Derg 39 km (24 mi), L. Ree 29 km (18 mi), L. Allen 11 km (7 mi)[17] plus L. Boderg, L. Bofin, L. Forbes, L. Corry) from the Shannon's freshwater flow of 258 km (160+1⁄2 mi), the Shannon, as a freshwater river, is only about 161 km (100 mi) long.

Apart from being Ireland's longest river, the Shannon is also, by far, Ireland's largest river by flow. It has a long-term average flow rate of 208.1 m3/s (7,350 cu ft/s) (at Limerick). This is double the flow rate of Ireland's second highest-volume river, the short River Corrib (104.8 m3/s [3,700 cu ft/s].[18] If the discharges from all of the rivers and streams into the Shannon Estuary (including the rivers Feale 34.6 m3/s [1,220 cu ft/s], Maigue 15.6 m3/s [550 cu ft/s], Fergus 25.7 m3/s [910 cu ft/s], and Deel 7.4 m3/s [260 cu ft/s])[19][20] are added to the discharge at Limerick, the total discharge of the River Shannon at its mouth at Loop Head reaches 300 m3/s (11,000 cu ft/s). Indeed, the Shannon is a major river by the time it leaves Lough Ree with an average flow rate (at Athlone weir) of 98 m3/s (3,500 cu ft/s),[21] larger than any of the other Irish rivers' total flow (apart from the River Corrib at Galway).

Distributaries

[edit]The main flow of the river is affected by some distributaries along its course, many of which rejoin it downstream. The Abbey River flows around the northeastern, eastern, and southern shores of King's Island, Limerick before rejoining the Shannon at Hellsgate Island.[22][23]

Protected areas

[edit]The Shannon Callows, areas of lowland along the river, are classified as a Special Area of Conservation.

Settlements

[edit]Settlements along the river (going upriver) include Kilrush, Tarbert, Glin, Foynes, Askeaton, Shannon Town, Limerick, Castletroy, Castleconnell, O'Briensbridge, Montpelier, Killaloe, Ballina, Portumna, Banagher, Athlone, Lanesborough, Carrick-on-Shannon, Leitrim village and Dowra.

Historical aspects

[edit]

The river began flowing along its present course after the end of the last glacial period.

Ptolemy's Geography (2nd century AD) described a river called Σηνος (Sēnos) from PIE *sai-/sei- 'to bind', the root of English sinew and Irish sin ‘collar’, referring to the long and sinuous estuary leading up to Limerick.[24][25]

Vikings settled in the region in the 10th century and used the river to raid the rich monasteries deep inland. In 937 the Limerick Vikings clashed with those of Dublin on Lough Ree and were defeated.

In the 17th century, the Shannon was of major strategic importance in military campaigns in Ireland, as it formed a physical boundary between the east and west of the country. In the Irish Confederate Wars of 1641–53, the Irish retreated behind the Shannon in 1650 and held out for two further years against English Parliamentarian forces. In preparing a land settlement, or plantation after his conquest of Ireland Oliver Cromwell reputedly said the remaining Irish landowners would go to "Hell or Connacht", referring to their choice of forced migration west across the river Shannon, or death, thus freeing up the eastern landholdings for the incoming English settlers.

In the Williamite War in Ireland (1689–91), the Jacobites also retreated behind the Shannon after their defeat at the Battle of the Boyne in 1690. Athlone and Limerick, cities commanding bridges over the river, saw bloody sieges (see Sieges of Limerick and Siege of Athlone).

As late as 1916, the leaders of the Easter Rising planned to have their forces in the west "hold the line of the Shannon". However, in the event, the rebels were neither well enough armed nor equipped to attempt such an ambitious policy.

Navigation

[edit]

1755 to 1820

[edit]Though the Shannon has always been important for navigation in Ireland, there is a fall of only 18 m (59 ft) in its first 250 km (160 mi). Consequently, it has always been shallow, with 0.5 m (1 ft 8 in) depths in various places. The first serious attempt to improve navigability came in 1755 when the Commissioners of Inland Navigation ordered Thomas Omer, a new immigrant from England, possibly of Dutch origin, to commence work.[26] He worked at four places between Lough Derg and Lough Ree where natural navigation was obstructed, by installing lateral canals and either pound locks or flash locks. He then continued north of Lough Ree and made several similar improvements, most notably by creating the first Jamestown Canal which cut out a loop of the river between Jamestown and Drumsna, as well as lateral canals at Roosky and Lanesborough.[26]

The lower Shannon between Killaloe and Limerick had a topography quite different from the long upper reaches. Here the river falls by 30 m (98 ft) in only 20 km (12 mi). William Ockenden, also from England, was placed in charge of works on this stretch in 1757 and spent £12,000 over the next four years, without fully completing the task. In 1771 parliament handed over responsibility to the Limerick Navigation Company, with a grant of £6,000 to add to their subscriptions of £10,000. A lateral canal, 8 km (5 mi) long with six locks, was started but the company needed more funds to complete it. In 1791, William Chapman was brought in to advise and discovered a sorry state of affairs – all the locks had been built to different dimensions and he spent the next three years supervising the rebuilding of most of them. The navigation was finally opened in 1799, when over 1,000 long tons (1,000 tonnes) of corn came down to Limerick, as well as slates and turf. But even then, there were no tow paths in the river sections and there were still shoals in the summer months, as well as a lack of harbour facilities at Limerick, and boats were limited to 15–20 long tons (15–20 tonnes) load, often less.[citation needed]

With the approaching opening of the Grand Canal, the Grand Canal Company obtained permission from the Directors General of Inland Navigation, and asked John Brownrigg to do a survey which found that much of Omer's work had deteriorated badly, so they started repairs. After protracted negotiations on costs and conditions, the work was completed by 1810, so that boats drawing 1.75 m (5 ft 9 in) could pass from Athlone to Killaloe. Improvements on the lower levels were also undertaken, being completed by 1814.[citation needed]

When the Royal Canal was completed in 1817 there was pressure to improve the navigation above Lough Ree. The Jamestown Canal was repaired, harbours built and John Killaly designed a canal alongside the river from Battlebridge to Lough Allen, which was opened in 1820.[citation needed]

1820s to Independence

[edit]| Shannon Navigation Act 1830 | |

|---|---|

| Act of Parliament | |

| |

| Long title | An Act for the improvement of the Shannon Navigation from the City of Limerick to Killaloe, by rebuilding the Bridge called Baal's Bridge, in the said City. |

| Citation | 11 Geo. 4 & 1 Will. 4. c. cxxvi |

| Dates | |

| Royal assent | 17 June 1830 |

| Text of statute as originally enacted | |

| Shannon Navigation Improvement Act 1835 | |

|---|---|

| Act of Parliament | |

| |

| Long title | An Act for the Improvement of the Navigation of the River Shannon. |

| Citation | 5 & 6 Will. 4. c. 67 |

| Dates | |

| Royal assent | 9 September 1835 |

| Other legislation | |

| Repealed by | |

Status: Repealed | |

| Shannon Navigation Act 1839 | |

|---|---|

| Act of Parliament | |

| |

| Long title | An Act for the Improvement of the Navigation of the River Shannon. |

| Citation | 2 & 3 Vict. c. 61 |

| Dates | |

| Royal assent | 17 August 1839 |

| Shannon Navigation Act 1847 | |

|---|---|

| Act of Parliament | |

| |

| Long title | An Act to provide for the Repayment of Sums due by the County of the City of Limerick for Advances of public Money for the Improvement of the Navigation of the River Shannon. |

| Citation | 10 & 11 Vict. c. 74 |

| Dates | |

| Royal assent | 22 July 1847 |

| Other legislation | |

| Repealed by | |

Status: Repealed | |

In the latter part of the 1820s, trade increased dramatically with the arrival of paddle-wheeled steamers on the river which carried passengers and goods. By 1831 14,600 passengers and 36,000 long tons (37,000 tonnes) of freight were being carried. This put new pressure on the navigation and a commission was set up resulting in the Shannon Navigation Improvement Act 1835 (5 & 6 Will. 4. c. 67) appointing five commissioners for the improvement of navigation and drainage who took possession of the whole navigation. Over the next 15 years, many improvements were made but in 1849 a railway was opened from Dublin to Limerick and the number of passengers fell dramatically. Freight, which had risen to over 100,000 long tons (100,000 tonnes) per year, was also halved.

But the work the commissioners carried out failed to solve the problems of flooding and there were disastrous floods in the early 1860s. Given the flat nature of most of the riverbank, this was not easily addressed and nothing much was done until the 20th century.

Ardnacrusha and passenger use

[edit]

One of the first projects of the Irish Free State in the 1920s was the Shannon hydroelectric scheme which established the Ardnacrusha power station on the lower Shannon above Limerick. The old Killaloe to Limerick canal with its five locks was abandoned and the head race constructed from Lough Derg also served for navigation. A double lock was provided at the dam.

In the 1950s traffic began to fall and low fixed bridges would have replaced opening bridges but for the actions of the Inland Waterways Association of Ireland which persuaded the Tánaiste to encourage passenger launches, which kept the bridges high enough for navigation. Since then the leisure trade has steadily increased, becoming a great success story.

Canals

[edit]There are also many canals connecting with the River Shannon. The Royal Canal and the Grand Canal connect the Shannon to Dublin and the Irish Sea. It is linked to the River Erne and Lough Erne by the Shannon–Erne Waterway.

Ballinasloe is linked to the Shannon via the River Suck and canal, while Boyle is connected via the Boyle canal, the river Boyle and Lough Key. There is also the Ardnacrusha canal connected with the Ardnacrusha dam south of Lough Derg. Near Limerick, a short canal connects Plassey with the Abbey River, allowing boats to bypass the Curraghower Falls, a major obstacle to navigation. Lecarrow village in County Roscommon is connected to Lough Ree via the Lecarrow canal. Jamestown Canal and the Albert Lock form a link between the River Shannon, from south of Jamestown, to Lough Nanoge to the south of Drumsna.

Etymology and folklore

[edit]Sionnann

[edit]

According to Irish mythology, the river was named after a woman (in many sources a member of the Tuatha de Danaan) named Sionann (older spelling forms: Sínann or Sínand), the granddaughter of Manannán mac Lir.[27] She went to Connla's Well to find wisdom, despite having been warned not to approach it. In some sources she, like Fionn mac Cumhaill, caught and ate the Salmon of Wisdom who swam there, becoming the wisest being on Earth, in others, she merely drank from the well. At any rate, the waters of the well are said to have burst forth, drowning Sionann, and carrying her out to sea.[28] Notably, a similar tale is told of Boann and the River Boyne. It is said that Sionann thus became the goddess of the river. Patricia Monaghan notes that "The drowning of a goddess in a river is common in Irish mythology and typically represents the dissolving of her divine power into the water, which then gives life to the land".[29]

A small myth about Sionann tells that the legendary hunter-warrior Fionn mac Cumhaill was attacked by a number of other warriors at Ballyleague, near north Lough Ree. It is said that when Fionn was near to defeat, Sionnan rescued him, and he arrived with the Stone of Sionann, threw the stone, and the warriors were immediately killed. It further says that Fionn was afraid of the power of the stone and threw it into the river, where it remains at a low ford, and that if a woman named Be Thuinne finds it, then the world's end is near.[28]

Creatures

[edit]The Shannon reputedly hosts a river monster named Cata, the first known mention being in the medieval Book of Lismore. In this manuscript, we are told that Senán, patron saint of County Clare, defeated the monster at Inis Cathaigh.[30] Cata is described as a large creature with a horse's mane, gleaming eyes, thick feet, nails of iron, and a whale's tail.[31] Another story has an oilliphéist flee its home in the Shannon, upon hearing that Saint Patrick has arrived to remove its kind from Ireland.[32]

Economics

[edit]

Despite being 360.5 km (224.0 mi) long, it rises only 76 m (249 ft) above sea level, so the river is easily navigable, with only a few locks along its length. There is a hydroelectric generation plant at Ardnacrusha belonging to the ESB.

Shipping in the Shannon estuary was developed extensively during the 1980s, with over IR£2 billion (€2.5 billion) investment. A tanker terminal at Foynes and an oil jetty at Shannon Airport were built. In 1982 a large-scale alumina extraction plant was built at Aughinish. 60,000-tonne cargo vessels now carry raw bauxite from West African mines to the plant, where it is refined to alumina. This is then exported to Canada where it is further refined to aluminium. 1985 saw the opening of a 915 MW coal-fired electricity plant at Moneypoint, fed by regular visits by 150,000-tonne bulk carriers.

Flora and fauna

[edit]Shannon eel management programme

[edit]A trap and transport scheme is in force on the Shannon as part of an eel management programme following the discovery of a reduced eel population. This scheme ensures safe passage for young eels between Lough Derg and the Shannon estuary.[33][34]

Fishing

[edit]Though the Shannon estuary fishing industry is now depleted, at one time it employed hundreds of men along its length. At Limerick, fishermen based on Clancy's Strand used the Gandelow to catch Salmon.[35] The Abbey Fishermen used a net and a boat type known as a Breacaun to fish between Limerick City and Plassey until 1929.[36] In 1929, the construction of a dam at Ardnacrusha severely impacted salmon breeding and that, and the introduction of quotas, had by the 1950s caused salmon fishing to cease.[37] However, recreational fishing still goes on. Further down the Shannon Estuary at Kilrush the Currach was used to catch herring as well as drift netting for salmon.

Water extraction

[edit]

Dublin City Council published a plan in 2011 to supply up to 350 million litres of water a day from Lough Derg to Dublin city and region. In 2016 the Parteen Basin to the south of lough was chosen as the proposed site of extraction. Water would be pumped to a break pressure tank Knockanacree near Cloughjordan in County Tipperary and gravity fed from there by pipeline to Dublin.[38][39][40][41]

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ Note Poll nm1: hole, pit, sink, leak, aperture (The Pocket Oxford Irish Dictionary – Irish-English)

References

[edit]- ^ "An tSionainn/River Shannon".

- ^ "Primary Seniors – Mountains, Rivers & Lakes". Ordnance Survey Ireland. Archived from the original on 29 May 2014. Retrieved 28 May 2014.

- ^ a b Feeley, Hugh B.; Bruen, Michael; Bullock, Craig; Christie, Mike; Kelly, Fiona; Kelly-Quinn, Mary (2017). ESManage Project: Irish Freshwater Resources and Assessment of Ecosystem Services Provision. Vol. Report No. 207. EPA. pp. Section 3.1.2. ISBN 978-1-84095-699-3.

- ^ Dobrzynski, Jan (2016). "Introduction". River Severn: From Source to Sea. Amberley Publishing. ISBN 9781445649054. Retrieved 4 January 2023.

- ^ "Chapter 2: Study Area" (PDF). Biology and Management of European Eel (Anguilla anguilla, L) in the Shannon Estuary, Ireland. Archived (PDF) from the original on 7 September 2014. Retrieved 7 September 2014.

- ^ a b "Facts". Ordnance Survey Ireland. Archived from the original on 11 September 2014. Retrieved 9 September 2014.

- ^ "Going through Ardnacrusha" (PDF). Inland Waterways News (Summer 2001 – Volume 28 Number 2). Inland Waterways Association of Ireland. Archived from the original (PDF) on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 9 September 2014.

- ^ Philip Elmer et al. Springs and Bottled Waters of the World Springer ISBN 3-540-61841-4

- ^ "The Shannon Guide". Archived from the original on 19 March 2015.

- ^ Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 24 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 819–820, see page 819, line two.

...with a length of about 240 m....

- ^ Delaney, Ruth (1996). Shell Guide to the River Shannon. Archived from the original on 3 March 2016. Retrieved 8 September 2014.

- ^ "Cruising on the Shannon". Fodor. Archived from the original on 8 September 2014.

- ^ a b "Nature & Scenery". Discover Ireland. Archived from the original on 20 May 2013.

- ^ Gunn, J. (31 January 2005). "Source of the River Shannon, Ireland". Environmental Geology. 27 (2): 110–112. doi:10.1007/BF01061681. S2CID 129442165.[dead link]

- ^ P. W. Joyce (1900). "Cavan". Atlas and Cyclopedia of Ireland. Murphy & McCarthy. Archived from the original on 11 April 2012. Retrieved 8 October 2011.

- ^ "Notes on river basins". 3 January 1872. Archived from the original on 25 March 2016. Retrieved 3 January 2020 – via Internet Archive.

- ^ "Home". askaboutireland.ie. Archived from the original on 10 January 2020. Retrieved 3 January 2020.

- ^ "South Eastern River Basin Management: Page 38" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 3 March 2016.

- ^ "Long-term effects of hydropower installations and associated river regulation on River Shannon eel populations: mitigation and management" (PDF). nuigalway.ie. Archived (PDF) from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 3 January 2020.

- ^ "SFPC Maintenance Dredging Application: Table 3-7" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 8 December 2014. Retrieved 14 April 2015.

- ^ "Shannon Catchment-based Flood Risk Assessment and Management (CFRAM) Study" (PDF). p. 6. Archived from the original (PDF) on 5 August 2018.

- ^ Simms, J.G. (1986). War and Politics in Ireland, 1649-1730. London: Hambledon Press. p. 22. ISBN 978-0907628729. Retrieved 23 October 2013.

The Shannon divides at Limerick; a branch, called the Abbey river, makes an island which was called the King's Island.

- ^ "Abbey River, Ireland". Geographical Names. National Geospatial-Intelligence Agency, Bethesda, Maryland, US. 5 May 1998. Archived from the original on 29 October 2013. Retrieved 23 October 2013.

- ^ "Ireland" (PDF). romaneranames.uk. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2 April 2019. Retrieved 3 January 2020.

- ^ Abshire, Corey; Durham, Anthony; Gusev, Dmitri A.; Stafeyev, Sergey K. (2018). "Ptolemy's Britain and Ireland: A New Digital Reconstruction" (PDF). Proceedings of the ICA. 1. International Cartographic Association: 1. Bibcode:2018PrICA...1....1A. doi:10.5194/ica-proc-1-1-2018. Archived (PDF) from the original on 21 July 2018. Retrieved 7 October 2020.

- ^ a b Ruth Delaney (2004). Ireland's Inland Waterways. Appletree Press.

- ^ Mícheál O Súilleabháin. "Listening to difference: Ireland in a world of music". In Harry Bohan and Gerard Kennedy (ed.). Global aspirations and the reality of change. Archived from the original on 4 April 2012.

- ^ a b Monaghan, Patricia. The Encyclopedia of Celtic Mythology and Folklore. Infobase Publishing, 2004. p.420

- ^ Monaghan, p.27

- ^ A Folklore Survey of County Clare: Supernatural Animals Archived 7 September 2011 at the Wayback Machine. Clarelibrary.ie. Retrieved on 23 July 2013.

- ^ Cata The Monster of Shannon Waves : A true Story by Shane Mac Olon

- ^ "The Schools' Collection, Volume 0210, Page 152". Duchas.ie. Archived from the original on 25 October 2019. Retrieved 19 March 2020.

- ^ "Shannon International River Basin District Eel Management Plan" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 14 December 2013. Retrieved 8 February 2014.

- ^ "Eel traps & transport". esb.ie. Archived from the original on 4 August 2014.

- ^ McInerney, Jim (2005) "The Gandelow: a Shannon Estuary Fishing Boat" A.K. Ilen Company Ltd, ISBN 0-9547915-1-7

- ^ "The Abbey Fisherman of the Abbey area in Limerick city, Ireland". Limerick's Life. 1 July 2012. Archived from the original on 12 April 2017. Retrieved 11 April 2017.

- ^ Darina Tully. "Clare Traditional Boat and Currach Project 2008" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 23 September 2015. Retrieved 3 January 2020.

- ^ "Water Supply Project Eastern and Midlands Region: Appendix G Break Pressure Tank" (PDF). November 2016. Archived (PDF) from the original on 8 November 2016. Retrieved 3 January 2020.

- ^ "Warning over Shannon water extraction". 31 July 2008. Archived from the original on 3 January 2020. Retrieved 3 January 2020 – via rte.ie.

- ^ "Shannon water extraction a concern for Limerick councillors". limerickleader.ie. 7 August 2015. Archived from the original on 28 December 2019. Retrieved 3 January 2020.

- ^ "River Shannon Protection Alliance: Why we say the Dublin Region Water Supply Project is a bad scheme" (PDF). oireachtas.ie. 26 October 2011. Archived from the original (PDF) on 8 November 2016.

External links

[edit]River Shannon

View on GrokipediaPhysical Geography

Course and Length

The River Shannon, Ireland's longest river, measures 360.5 kilometres from its source to the head of the Shannon Estuary.[10] It originates at Shannon Pot, a pool on the slopes of Cuilcagh Mountain in the Cuilcagh-Carie Mountains Straddles Special Area of Conservation in northwestern County Cavan, at an elevation of approximately 244 metres above sea level.[11] From its source, the Shannon flows southwest for about 11 kilometres through peatlands and blanket bog before entering Lough Allen on the Leitrim-Roscommon border. Emerging from Lough Allen near the village of Drumshanbo in County Leitrim, the river continues southward, passing through Carrick-on-Shannon and forming part of the border between Counties Leitrim and Roscommon. It then traverses Counties Longford and Westmeath, widening into Lough Ree near Lanesborough, before flowing past Athlone.[12] South of Lough Ree, the Shannon proceeds through Counties Offaly and Galway, passing Shannonbridge and entering Lough Derg near Portumna. From Lough Derg, it flows past Killaloe—where it briefly forms the border between Counties Clare and Tipperary—before reaching Limerick in County Limerick. At Limerick, the river broadens into the Shannon Estuary, a 102-kilometre-long inlet that discharges into the Atlantic Ocean between Counties Limerick and Kerry. The Shannon's course traverses or borders 11 counties: Cavan, Leitrim, Longford, Roscommon, Westmeath, Offaly, Galway, Tipperary, Clare, Limerick, and Kerry.[13]Tributaries and Drainage Basin

The drainage basin of the River Shannon encompasses approximately 18,000 km², constituting about one-fifth of Ireland's total land area of 84,421 km².[4] [14] This catchment, designated as the Shannon International River Basin District, extends from the Cuilcagh Mountains in County Cavan southward to the Atlantic Ocean via the Shannon Estuary, traversing 18 counties and featuring a mix of peatlands, agricultural lowlands, and upland areas.[4] The basin's hydrology is influenced by its position in Ireland's central lowland, with permeable soils and high rainfall contributing to steady runoff, though regulated by large lakes including Lough Allen, Lough Ree, and Lough Derg.[2] The Shannon receives inflows from numerous sub-catchments, with major tributaries augmenting its discharge significantly. The River Suck, the largest tributary at 133 km long, joins the Shannon at Shannonbridge after draining 1,900 km² in counties Offaly, Roscommon, and Galway.[15] Other key northern and central tributaries include the River Inny (entering Lough Ree after a 40 km course through Westmeath and Longford) and the River Brosna (joining near Banagher).[16] In the lower basin, the Rivers Deel, Maigue, and Feale contribute from Limerick and Kerry, with the Maigue draining 1,135 km² of fertile farmland.[16] These tributaries collectively account for a substantial portion of the Shannon's mean discharge of over 200 m³/s at Limerick.[10]| Major Tributary | Approximate Length (km) | Junction Point |

|---|---|---|

| River Suck | 133 | Shannonbridge |

| River Inny | 40 | Lough Ree |

| River Brosna | 85 | Near Banagher |

| River Maigue | 47 | Near Limerick |

| River Feale | 64 | Near Foynes |