Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Sandžak

View on WikipediaSandžak (Serbian: Санџак; Bosnian: Sandžak) is a historical[1][2][3] and geo-political region in the Balkans, located in the southwestern part of Serbia and the eastern part of Montenegro.[4] The Bosnian/Serbian term Sandžak derives from the Sanjak of Novi Pazar, a former Ottoman administrative district founded in 1865. Sandžak is inhabited by a plurality of ethnic Bosniaks.[5]

Key Information

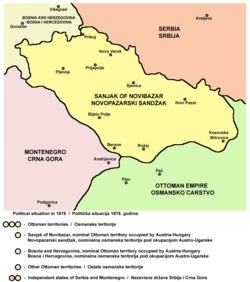

Various empires and kingdoms have ruled over the region. In the 12th century, Sandžak was part of the region of Raška under the medieval Serbian Kingdom. During the Ottoman territorial expansion into the western Balkans in a series of wars, the region became an important administrative district, with Novi Pazar as its administrative center.[6] Sandžak was under Austro-Hungarian occupation between 1878 and 1909 as a garrison, until an agreement between Austria-Hungary and the Ottoman Empire resulted in the withdrawal of Austro-Hungarian troops from Sandžak in exchange for full control over Bosnia.[7][8] In 1912, it was divided between the Kingdom of Montenegro and the Kingdom of Serbia.

Novi Pazar serves as Sandžak's economic and cultural center and is the region's most populous city. Sandžak has a diverse and complex ethnic and religious composition, with significant Eastern Orthodox, Roman Catholic, and Sunni Muslim populations. Bosniaks comprise ethnic majority in this region.[citation needed]

Etymology

[edit]The Serbo-Croatian term Sandžak (Serbian Cyrillic: Санџак) is the transcription of Ottoman Turkish sancak (sanjak, "province");[9] the Sanjak of Novi Pazar, known in Serbo-Croatian as Novopazarski sandžak. Historically, it is known as Raška by the Serbs. The region is known as Sanxhak in Albanian.[10]

Geography

[edit]Sandžak stretches from the southeastern border of Bosnia and Herzegovina[11] to the borders with Kosovo[12][13][14] and Albania[14] at an area of around 8,500 square kilometers. Six municipalities of Sandžak are in Serbia (Novi Pazar, Sjenica, Tutin, Prijepolje, Nova Varoš, and Priboj[15]), and seven in Montenegro (Pljevlja, Bijelo Polje, Berane, Petnjica, Rožaje, Gusinje, and Plav).[16] Sometimes the Montenegrin municipality of Andrijevica is also regarded as part of Sandžak.

The most populated municipality in the region is Novi Pazar (100,410),[17] while other large municipalities are: Pljevlja (31,060),[18] and Priboj (27,133).[17] In Serbia, the municipalities of Novi Pazar and Tutin are part of the Raška District,[19] while the municipalities of Sjenica, Prijepolje, Nova Varoš, and Priboj, are part of the Zlatibor District.[19]

History

[edit]Ottoman rule

[edit]The Serbian Despotate was invaded by the Ottoman Empire in 1455. Apart from the effect of a lengthy period under Ottoman domination, many of the subject populations were periodically and forcefully converted to Islam[20][21] as a result of a deliberate move by the Ottoman Turks as part of a policy of ensuring the loyalty of the population against a potential Venetian invasion. However, Islam was spread by force in the areas under the control of the Ottoman sultan through the devşirme system of child levy enslavement,[20][22] by which indigenous European Christian boys from the Balkans (predominantly Albanians, Bulgarians, Croats, Greeks, Romanians, Serbs, and Ukrainians) were taken, levied, subjected to forced circumcision and forced conversion to Islam, and incorporated into the Ottoman army,[20][22] and jizya taxes.[20][21][23]

The Islamization of Sandžak was otherwise caused by a number of factors, mainly economic, as Muslims didn't pay the devşirme tributes and jizya taxes.[24] The Muslims were also privileged compared to Christians, who were unable to work in the administration or testify in court against Muslims, as they were treated as dhimmi.[25] The second factor that contributed to the Islamization were migrations; a large demographic shift occurred after the Great Turkish War (1683–1699). Part of the Slavic-speaking Orthodox Christian population was expelled northwards, while other Christians and Muslims were driven to the Ottoman territory.[26] The land abandoned by the Eastern Orthodox Serbs was settled by populations from neighbouring areas who either were or became Muslim in Sandžak. Large migrations occurred throughout the 18th and 19th centuries.[26] The third factor of Islamization was the geographical location of Sandžak, which allowed it to become a trade centre, facilitating conversions amongst merchants.[26] The tribal migrations to Sandžak had contributed a large role to its history and identity along with culture.[27][28]

The second half of the 19th century was very important in terms of shaping the current ethnic and political situation in Sandžak.[29] Austria-Hungary supported Sandžak's separation from the Ottoman Empire, or at least its autonomy within it.[29] The reason was to prevent the kingdoms of Montenegro and Serbia from unifying, and allow Austria-Hungary's further expansion into the Balkans. Per these plans, Sandžak was seen as part of the Condominium of Bosnia and Herzegovina, while its Muslim population played a significant role, giving Austrian-Hungarians a pretext of protecting the Muslim minority from the Eastern Orthodox Serbs.[29]

Sandžak was an administrative part of the Sanjak of Bosnia until 1790, when it become a separated Sanjak of Novi Pazar.[30] However, in 1867, it become a part of the Bosnia Vilayet that consisted of seven sanjaks, including the Sanjak of Novi Pazar.[31] This led to Sandžak Muslims identifying themselves with other Slavic Muslims in Bosnia.[32]

Albanian speakers gradually migrated or were relocated to the Ottoman provinces of Kosovo and North Macedonia, leaving a primarily Slavic-speaking population in the rest of the region (except in a southeastern corner of Sandžak that ended up as a part of Kosovo).[33]

Some members of the Albanian Shkreli and Kelmendi tribes began migrating into the lower Pešter and Sandžak regions at around 1700. The Kelmendi chief had converted to Islam, and promised to convert his people to.[34] A total of 251 Kelmendi households (1,987 people) were resettled in the Pešter area on that occasion, however five years later part the exiled Kelmendi managed to fight their way back to their homeland, and in 1711 they sent out a large raiding force to bring back some other from Pešter too.[34] The remaining Kelmendi and Shkreli converted to Islam and became Slavophones by the 20th century, and as of today they now self-identify as part of the Bosniak ethnicity, although in the Pešter plateau they partly utilized the Albanian language until the middle of the 20th century, particuarily in the villages of Ugao, Boroštica, Doliće, and Gradac.[35] Since the 18th century, many people originating from the Hoti tribe have migrated to and live in Sandžak, mainly in the Tutin area, but also in Sjenica.[36]

Balkan Wars and the World War I

[edit]In October 1912, during the First Balkan War, Serbian and Montenegrin troops seized Sandžak, which was then divided between the two countries.[citation needed] This led to the displacement of many Slavic Muslims and Albanians, who migrated to Ottoman Turkey as muhajir.[citation needed]

After the war, Sandžak became a part of the newly formed State of Slovenes, Croats and Serbs.[29] The region acted as a bridge between the Muslims in the West in Bosnia and Herzegovina and those in the East in Kosovo and North Macedonia. However, the Slavic Muslims of Sandžak suffered economic decline due to the defeat and collapse of the Ottoman Empire, which had been their primary source of economic stability.[37] Additionally, the agrarian reform implemented in the Kingdom of Yugoslavia worsened their economic situation, leading to the emigration of Muslims from Sandžak to the Ottoman Empire.[37]

During World War I, Sandžak was occupied by Austria-Hungary. In 1919, an Albanian revolt, which later came to be known as the Plav rebellion rose up in the Rožaje, Gusinje, and Plav districts, fighting against the inclusion of Sandžak in the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes.[38][39][40] As a result, during the Serbian army's second occupation of Rožaje, which took place in 1918-1919, seven hundred Albanian citizens were slaughtered in Rožaje.[citation needed] In 1919, Serb forces attacked Albanian populations in Plav and Gusinje, which had appealed to the British government for protection.[citation needed] About 450 local civilians were killed after the uprising was quelled.[41] These events resulted in a large influx of Albanians migrating to the Principality of Albania.[42][43]

World War II

[edit]

In World War II, Sandžak was the battleground of several factions. In 1941, the region was partitioned between the Italian governorate of Montenegro, the Italian protectorate over the Kingdom of Albania, and the Territory of the Military Commander in Serbia.[44] The Muslim population was in general anti-partisan.[45] They were organized in small formations known in historiography as the Sandžak Muslim militia. These formations depending on their location and regional politics were affiliated to Albanian nationalist groups linked to Balli Kombëtar in central and south Sandžak or to Muslim Ustaše groups in the north. Many Orthodox Serbs organized in the Serbian nationalist Chetniks. The stance of these factions towards the Nazi forces ranged from armed resistance to open collaboration. Smaller groups of both Orthodox Serbs and Muslims organized after 1943 in the Yugoslav Partisan Anti-Fascist Council of the People's Liberation of Sandžak. Each faction sought the inclusion of Sandžak in the post-war period into separate states. Albanian militia fought for inclusion in Greater Albania, while Ustaše formations wanted at least part of Sandžak to join the Independent State of Croatia. Amonge these factions, the Yugoslavs, Slavic Muslims, Serbs, and Montenegrins adopted different strategies. Muslims wanted either unification with Bosnia under a federal Yugoslavia or the establishment of an autonomous Sandžak region. Serbs and Montenegrins wanted the area to either pass entirely to Serbia or Montenegro.[46]

The formal partition of Sandžak between Italian and German spheres of influence was largely ignored as local politics shaped control over the area. Prijepolje which formally was within the Italian area of rule in Montenegro was in fact under the NDH-affiliated Sulejman Pačariz, while Novi Pazar in the German sphere was led by the Albanian nationalist Aqif Bluta. Clashes between Albanians and Serbs in south Sandžak began in April 1941. In other cities of Sandžak similar battles between different factions played out. Otto von Erdmannsdorf, the special envoy of Germany to Sandžak mentioned in his correspondence that up to 100,000 Albanians from Sandžak wanted to be moved from Serbia under the jurisdiction of Albania.[47] The Italian and German forces considered to enact population exchange from Sandžak to Kosovo to stop interethnic violence between Serbs and Albanians. Peter Pfeiffer, diplomat of the Foreign Office of Germany warned that relocation plans would cause a great rift between the German army and Albanians and they were abandoned. In November 1941 as clashes continued Albanians defeated the Chetniks in the battle of Novi Pazar. The battle was followed by reprisals against the Serbs of Novi Pazar. In 1943, Chetnik forces based in Montenegro conducted a series of ethnic cleansing operations against Muslims in the Bihor region of modern-day Serbia. In May 1943, an estimated 5400 Albanian men, women and children in Bihor were massacred by Chetnik forces under Pavle Đurišić.[48] In a reaction, the notables of the region then published a memorandum and declared themselves to be Albanians. The memorandum was sent to Prime Minister Ekrem Libohova whom they asked to intervene so the region could be united to the Albanian kingdom.[49] It has been estimated that 9,000 Muslims were killed in total by the Chetniks and affiliated groups during the war in Sandžak.[50] The Jewish community of Novi Pazar was initially not harassed because the city didn't have any considerable concentration of German forces, but on March 2, 1942 the city's Jews were rounded up by the German army and killed in extermination camps (the men in Bubanj and the women and children in Sajmište).[51][52]

1943 year saw the creation of the SS-Police "Self-Defence" Regiment Sandžak, being formed by joining three battalions of Albanian collaborationist troops with one battalion of the Sandžak Muslim militia.[53][54] At one point around 2,000 members of the SS regiment operated in Sjenica.[55] Its leader was Sulejman Pačariz,[56] an Islamic cleric of Albanian origin.[57]

The Anti-Fascist Council of People's Liberation of Sandžak (AVNOS) had been founded on 20 November 1943 in Pljevlja.[58] In January 1944, the Land Assembly of Montenegro and the Bay of Kotor claimed Sandžak as part of a future Montenegrin federal unit. However, in March, the Communist Party opposed this, insisting that Sandžak's representatives at AVNOJ should decide on the matter.[59] In February 1945, the Presidency of the AVNOJ made a decision to oppose the Sandžak's autonomy. The AVNOJ explained that the Sandžak did not have a national basis for an autonomy and opposed crumbling of the Serbian and Montenegrin totality.[60] On 29 March 1945 in Novi Pazar, the AVNOS accepted the decision of the AVNOJ and divided itself between Serbia and Montenegro.[61] Sandžak was divided based on the 1912 demarcation line.[60]

Yugoslavia

[edit]Economically, Sandžak remained undeveloped. It had a small amount of crude and low-revenue industry. Freight was transported by trucks over poor roads. Schools for business students, which remained poor in general education, were opened for working-class youth. The Sandžak had no faculty, not even a department or any school of higher education.[37]

Sandžak saw a process of industrialisation, during which factories were opened in several cities, including Novi Pazar, Prijepolje, Priboj, Ivangrad, while the coal mines were opened in the Prijepolje area. The urbanisation caused a major social and economic shift. Many people left villages for towns. The national composition of the urban centres was changed to the disadvantage of the Muslims, as most of those who inhabited the cities were Serbs. The Muslims continued to lose their economic status, continuing the trend inherited from the time of the collapse of the Ottoman Empire and the agrarian reform in the Kingdom of Yugoslavia.[37] The emigration of the Muslims to Turkey also continued, caused by the general underdevelopment of the region, disagreement with the communist authorities and the mistrust with the Serbs and Montenegrins, but also due to the nationalisation and expropriation of property. Serbs from Sandžak also moved to the wealthier regions of the central Serbia or to Belgrade or Vojvodina, while the Muslims moved to Bosnia and Herzegovina as well.[62]

1991 Referendum on autonomy

[edit]Between 25 and 27 October 1991, a referendum on Sandžak's autonomy was held, organized by the Muslim National Council of Sandžak (MNVS) which consisted of the Muslim Party of Democratic Action (SDA) and other Bosnian Muslim organizations and parties.[63] It was declared illegal by Serbia. According to the SDA, 70.2% of the population participated in the referendum with 98.92% voting in favor of autonomy.[64]

Contemporary period

[edit]With the democratic changes in Serbia in 2000, the ethnic Bosniaks were enabled to start participating in the political life in Serbia and Montenegro, including Rasim Ljajić, an ethnic Bosniak, who was a minister in the verious governments of Serbia, and Rifat Rastoder, who was the Deputy President of the Parliament of Montenegro. Census data shows a general emigration of all ethnicities from this underdeveloped region.[citation needed]

Demographics

[edit]

The population of the sanjak of Novi Pazar was ethnically and religiously diverse. In 1878-81, Muslim Slav muhacirs (refugees) from areas which became part of Montenegro, settled in the sanjak. As Ottoman institutions only registered religious affiliation, official Ottoman statistics about ethnicity do not exist. Austrian, Bulgarian and Serbian consulates in the area produced their own ethnographic estimations about the sanjak. In general, three main groups lived in the region: Orthodox Serbs, Muslim and Catholic Albanians and Muslim Slavs (noted in contemporary sources as Bosniaks). Small communities of Romani, Turks and Jews lived mainly in towns. The Bulgarian foreign ministry compiled a report in 1901-02. The five kazas (districts) of the sanjak of the Novi Pazar at that time were: Akova, Sjenica, Kolašin, Novi Pazar, and Nova Varoš. According to the Bulgarian report, in the kaza of Akova there were 47 Albanian villages which had 1,266 households. Serbs lived in 11 villages which had 216 households.[65] The town of Akova (Bijelo Polje) had 100 Albanian and Serb households. There were also mixed villages - inhabited by both Serbs and Albanians - which had 115 households with 575 inhabitants. The kaza of Sjenica was inhabited mainly by Orthodox Serbs (69 villages with 624 households) and Bosnian Muslims (46 villages with 655 households). Seventeen villages had a population of both Orthodox Serbs and Bosnian Muslims. Albanians (505 households) lived exclusively in the town of Sjenica. The kaza of Novi Pazar had 1,749 households in 244 Serb villages and 896 households in 81 Albanian villages. Nine villages inhabited by both Serbs and Albanians had 173 households. The town of Novi Pazar had a total of 1,749 Serb and Albanian households with 8,745 inhabitants.[66] The kaza of Kolašin had 27 Albanian villages with 732 households and 5 Serb villages with 75 households. The administrative centre of the kaza, Šahovići, had 25 Albanian households. The kaza of Novi Varoš, according the Bulgarian report, had 19 Serbian villages with 298 households and "one Bosnian village with 200 houses".[67] Novi Varoš had 725 Serb and some Albanian households.[68]

The last official registration of the population of the sanjak of Novi Pazar before the Balkan Wars was conducted in 1910. The 1910 Ottoman census recorded 52,833 Muslims and 27,814 Orthodox Serbs. About 65% of the population were Muslims and 35% Serbian Orthodox. The majority of the Muslim population were Albanians.[69]

The last Yugoslav pre-war census of 1931 counted in Bijelo Polje, Prijepolje, Nova Varoš, Pljevlja, Priboj, Sjenica and Štavica a total population of 204,068. They were mostly counted as Orthodox Serbs or Montenegrins (56.5%) and Bosnian Muslims (43.1%).[46]

Most Bosniaks declared themselves ethnic Muslims in 1991 census. By the 2002-2003 census, however, most of them declared themselves Bosniaks. There is still a significant minority that identify as Muslims (by ethnicity). There are still some Albanian villages (Boroštica, Doliće and Ugao) in the Pešter region.[70] There were a larger presence of Albanians in Sandžak in the past, however due to various factors such as migration, assimilation, along with mixing, many identify as Bosniaks instead.[27][71][72] Catholic Albanian groups which settled in Tutin and Pešter in the early 18th century were converted to Islam in that period. Their descendants make up the large majority of the population of Tutin and the Pešter plateau.[73]

The Slavic dialect of Gusinje and Plav (sometimes considered part of Sandžak) shows very high structural influence from Albanian. Its uniqueness in terms of language contact between Albanian and Slavic is explained by the fact that most Slavic-speakers in today's Plav and Gusinje are of Albanian origin.[74]

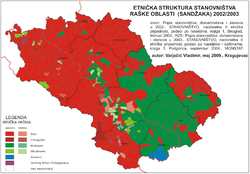

Ethnic structure

[edit]The total population of the municipalities of Sandžak in Serbia and Montenegro is around 361,656. A majority of people in Sandžak identify as Bosniaks. They form 54.8% (198,100) of the region's population. Serbs form 30% (112,217), Montenegrins 5% (18,346), ethnic Muslims 3.4% (12,234), and Albanians 1% (3,722). About 17,037 (4.7%) people belong to smaller communities or have chosen to not declare an ethnic identity.

| Municipality | Ethnicity (2022 Serbian census and 2023 Montenegrin census) | Total | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bosniaks | % | Serbs | % | Montenegrins | % | Muslims | % | Albanians | % | others | % | ||

| Novi Pazar (Serbia) | 85,204 | 79.8 | 14,142 | 13.2 | 34 | 0.03 | 1,851 | 1.7 | 200 | 0.2 | 5,289 | 4.9 | 106,720 |

| Bijelo Polje (Montenegro) | 12,315 | 31.8 | 16,675 | 43.1 | 5,751 | 14.9 | 2,916 | 7.5 | 55 | 0.1 | 950 | 2.4 | 38,662 |

| Tutin (Serbia) | 30,413 | 92 | 704 | 2.1 | 1 | 0 | 340 | 1 | 16 | 0.05 | 1,579 | 4.8 | 33,053 |

| Prijepolje (Serbia) | 12,842 | 39.8 | 14,961 | 46.4 | 37 | 0.1 | 1,945 | 6 | 10 | 0.03 | 2,419 | 7.5 | 32,214 |

| Berane (Montenegro) | 1,103 | 4.5 | 14,742 | 59.8 | 6,548 | 26.5 | 532 | 2.1 | 28 | 0.1 | 1,692 | 6.8 | 24,645 |

| Pljevlja (Montenegro) | 1,765 | 7.3 | 16,027 | 66.4 | 4,378 | 18.1 | 797 | 3.3 | 0 | 0 | 1,167 | 4.8 | 24,134 |

| Sjenica (Serbia) | 17,665 | 73.3 | 3,861 | 16 | 3 | 0.01 | 1,069 | 4.4 | 26 | 0.1 | 1,459 | 6 | 24,083 |

| Priboj (Serbia) | 4,144 | 17.6 | 16,909 | 71.9 | 47 | 0.2 | 914 | 3.9 | 2 | 0.01 | 1,498 | 6.3 | 23,514 |

| Rožaje (Montenegro) | 19,627 | 84.6 | 593 | 2.5 | 868 | 3.7 | 738 | 3.2 | 1,176 | 5 | 182 | 0.8 | 23,184 |

| Nova Varoš (Serbia) | 673 | 5 | 11,901 | 88.1 | 9 | 0.07 | 308 | 2.3 | 4 | 0.03 | 612 | 4.5 | 13,507 |

| Plav (Montenegro) | 5,940 | 65.6 | 1,546 | 17.1 | 372 | 4.1 | 236 | 2.6 | 853 | 9.4 | 103 | 1.1 | 9,050 |

| Petnjica (Montenegro) | 4,162 | 83.9 | 47 | 0.9 | 237 | 4.8 | 461 | 9.3 | 0 | 0.00 | 50 | 1 | 4,957 |

| Gusinje (Montenegro) | 2,247 | 57.1 | 109 | 2.7 | 61 | 1.5 | 127 | 3.2 | 1,352 | 34.4 | 37 | 0.9 | 3,933 |

| Sandžak | 198,100 | 54.8 | 112,217 | 30 | 18,346 | 5 | 12,234 | 3.4 | 3,722 | 1 | 17,037 | 4.7 | 361,656 |

Religious structure

[edit]Religion in Sandžak is also as diverse as the ethnic composition, most of the Bosniaks being Muslim while a majority of the Serbs being Orthodox Christian. However, because of the prolonged Ottoman rule, Sandžak is more Muslim orientated.

| Municipality | Religion (2022 Serbian census[75] and 2023 Montenegrin census[76]) | Total | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Muslims | % | Orthodox | % | others | % | ||

| Novi Pazar (Serbia) | 88,493 | 82.9 | 13,690 | 12.8 | 4,537 | 4.2 | 106,720 |

| Bijelo Polje (Montenegro) | 17,202 | 44.4 | 20,956 | 54.2 | 504 | 1.3 | 38,662 |

| Tutin (Serbia) | 30,909 | 93.5 | 646 | 1.9 | 1,498 | 4.5 | 33,053 |

| Prijepolje (Serbia) | 15,066 | 46.7 | 14,941 | 46.4 | 2,207 | 6.8 | 32,214 |

| Berane (Montenegro) | 3,698 | 15 | 20,384 | 82.7 | 563 | 2.3 | 24,645 |

| Pljevlja (Montenegro) | 4,092 | 16.9 | 19,330 | 80.1 | 712 | 2.9 | 24,134 |

| Sjenica (Serbia) | 18,860 | 78.3 | 3,808 | 15.8 | 1,415 | 5.9 | 24,083 |

| Priboj (Serbia) | 5,119 | 21.7 | 16,687 | 70.9 | 1,708 | 7.2 | 23,514 |

| Rožaje (Montenegro) | 22,378 | 96.5 | 715 | 3.1 | 91 | 0.4 | 23,184 |

| Nova Varoš (Serbia) | 1,069 | 7.91 | 11,742 | 86.9 | 696 | 5.1 | 13,507 |

| Plav (Montenegro) | 7,164 | 79.1 | 1,800 | 19.9 | 86 | 0.9 | 9,050 |

| Petnjica (Montenegro) | 4,881 | 98.4 | 65 | 1.3 | 11 | 0.2 | 4,957 |

| Gusinje (Montenegro) | 3,640 | 92.5 | 122 | 3.1 | 171 | 4.3 | 3,933 |

| Sandžak | 222,571 | 61.5 | 124,886 | 34.5 | 14,199 | 3.9 | 361,656 |

Gallery

[edit]-

Church of the Holy Apostles Peter and Paul, Ras near Novi Pazar, 8-9th century

-

Stari Ras fortress near Novi Pazar, 8th century

-

Đurđevi Stupovi monastery, near Novi Pazar, 12th century

-

Sopoćani monastery near Novi Pazar, 13th century

-

Husein-pasha Mosque in Pljevlja

-

A wall built during the Ottoman period in Novi Pazar

-

Kučanska Mosque in Rožaje, 1830

See also

[edit]References

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ Stjepanović, Dejan (2012). "Regions and Territorial Autonomy in Southeastern Europe". In Gagnon, Alain-G.; Keating, Michael (eds.). Political autonomy and divided societies: Imagining democratic alternatives in complex settings. Palgrave Macmillan. p. 194. ISBN 9780230364257.

- ^ Roth, Clémentine (2018). Why Narratives of History Matter: Serbian and Croatian Political Discourses on European Integration. Nomos publishing house. p. 268. ISBN 9783845291000.

- ^ Duda, Jacek (2011). "Islamic community in Serbia - the Sandžak case". In Górak-Sosnowska, Katarzyna (ed.). Muslims in Poland and Eastern Europe: Widening the European Discourse on Islam. University of Warsaw: Faculty of Oriental Studies. p. 327. ISBN 9788390322957.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: publisher location (link) - ^ Karen Dawisha; Bruce Parrott (13 June 1997). Politics, Power and the Struggle for Democracy in South-East Europe. Cambridge University Press. pp. 175–. ISBN 978-0-521-59733-3.

- ^ "World Directory of Minorities and Indigenous Peoples - Serbia : Bosniaks". Refworld. Retrieved 2025-02-02.

- ^ Hozic, Aida (2006). "The Balkan Merchants: Changing Borders and Informal Transnationalization". Ethnopolitics. 5 (3): 243–248. doi:10.1080/17449050600911059.

- ^ Cviic, Christopher (1995). Remaking the Balkans. Pinter. p. 75. ISBN 9781855672949.

- ^ Malcolm, Noel (1996). Bosnia: A Short History. NYU Press. p. 151. ISBN 9780814755617.

- ^ "Dictionary.com - Sanjak entry".

- ^ "Kuptimi i fjalës Sanxhak ‹ FJALË". fjale.al (in Albanian). Retrieved 2024-09-20.

- ^ "Position of the Municipality of Priboj". priboj.rs. Municipality of Priboj.

- ^ "Geographic position of Municipality of Tutin". tutin.rs. Municipality of Tutin. 19 March 2016.

- ^ "Geographic position of Municipality of Rožaje". rozaje.me. Municipality of Rozaje.

- ^ a b "Profile of Municipality of Plav" (PDF). plav.me. Municipality of Plav. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2017-03-11. Retrieved 2017-04-30.

- ^ "Territorial organisation of Republic of Serbia". paragraf.rs.

- ^ "Territorial organization of Montenegro" (PDF). mup.gov.me. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2017-08-03. Retrieved 2017-04-30.

- ^ a b "2011 Census of Population, Households and Dwellings in the Republic of Serbia" (PDF). stat.gov.rs.

- ^ "2011 Census of Population, Households and Dwellings in Montenegro" (PDF). monstat.org.

- ^ a b "Government of Republic of Serbia - Administrative Okrugs Regions". uzzpro.gov.rs).

- ^ a b c d Ágoston, Gábor (2009). "Devşirme (Devshirme)". In Ágoston, Gábor; Masters, Bruce (eds.). Encyclopedia of the Ottoman Empire. New York: Facts On File. pp. 183–185. ISBN 978-0-8160-6259-1. LCCN 2008020716. Retrieved 16 September 2024.

- ^ a b Wittek, Paul (1955). "Devs̱ẖirme and s̱ẖarī'a". Bulletin of the School of Oriental & African Studies. 17 (2). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press on behalf of the School of Oriental and African Studies, University of London: 271–278. doi:10.1017/S0041977X00111735. JSTOR 610423. OCLC 427969669. S2CID 153615285.

- ^ a b Glassé, Cyril, ed. (2008). The New Encyclopedia of Islam (3rd ed.). Lanham, Maryland: Rowman & Littlefield. p. 129. ISBN 978-1-4422-2348-6.

- ^ Basgoz, I. & Wilson, H. E. (1989), The educational tradition of the Ottoman Empire and the development of the Turkish educational system of the republican era. Turkish Review 3(16), 15

- ^ Górak-Sosnowska 2011, p. 328.

- ^ Todorović 2012, p. 13.

- ^ a b c Górak-Sosnowska 2011, pp. 328–329.

- ^ a b Memoirs of the American Folklore Society. University of Texas Press. 1954.

- ^ Elsie, Robert (2015-04-24). The Tribes of Albania: History, Society and Culture. Bloomsbury Publishing. ISBN 978-0-85772-586-8.

- ^ a b c d Górak-Sosnowska 2011, p. 329.

- ^ Djukanovic, Bojka (2023). Historical Dictionary of Montenegro. Rowman & Littlefield. p. 337. ISBN 9781538139158.

- ^ Klemenčić, Mladen (1994). Territorial Proposals for the Settlement of the War in Bosnia-Hercegovina. IBRU. p. 15. ISBN 9781897643150.

- ^ Todorović 2012, p. 11.

- ^ Dragostinova, Theodora; Hashamova, Yana (2016-08-20). Beyond Mosque, Church, and State: Alternative Narratives of the Nation in the Balkans. Central European University Press. ISBN 978-963-386-135-6.

- ^ a b Elsie 2015, p. 32.

- ^ Robert Elsie (30 May 2015). The Tribes of Albania: History, Society and Culture. I.B.Tauris. p. 81. ISBN 978-1-78453-401-1.

- ^ Biber, Ahmet. "HISTORIJAT RODOVA NA PODRUČJU BJELIMIĆA". Fondacija "Lijepa riječ". Archived from the original on February 21, 2020.

- ^ a b c d Hadžišehović, Butler & Risaluddin 2003, p. 132.

- ^ Morrison 2018, p. 56.

- ^ Giuseppe Motta, Less than Nations: Central-Eastern European Minorities after WWI, Volume 1 Archived 2016-03-04 at the Wayback Machine, Cambridge Scholars Publishing, 2013, p. 11

- ^ Klaus Roth, Ulf Brunnbauer, Region, Regional Identity and Regionalism in Southeastern Europe, Part 1, LIT Verlag Münster, 2008, p. 221

- ^ Morrison 2018, p. 21.

- ^ Mulaj, Klejda (2008-02-22). Politics of Ethnic Cleansing: Nation-State Building and Provision of In/Security in Twentieth-Century Balkans. Lexington Books. p. 33. ISBN 978-0-7391-4667-5.

- ^ Banac, Ivo (2015-06-09). The National Question in Yugoslavia: Origins, History, Politics. Cornell University Press. pp. 298 snippet view. ISBN 978-1-5017-0194-8.

- ^ Zaugg 2021, p. 45.

- ^ Banac 1988, p. 100.

- ^ a b Banac 1988, p. 101

- ^ Zaugg 2021, p. 58.

- ^ Kaba, Hamit (2013). "RAPORTI I STAVRO SKËNDIT DREJTUAR OSS' NË WASHINGTON D.C "SHQIPËRIA NËN PUSHTIMIN GJERMAN". STAMBOLL, 1944". Studime Historike (3–04): 275.

- ^ Džogović, Fehim (2020). "NEKOLIKO DOKUMENATA IZ DRŽAVNOG ARHIVA ALBANIJE U TIRANI O ČETNIČKOM GENOCIDU NAD MUSLIMANIMA BIHORA JANUARA 1943". ALMANAH - Časopis za proučavanje, prezentaciju I zaštitu kulturno-istorijske baštine Bošnjaka/Muslimana (in Bosnian) (85–86): 329–341. ISSN 0354-5342.

- ^ Jancar-Webster 2010, p. 70.

- ^ Greble 2011, p. 115.

- ^ Mojzes 2011, p. 94.

- ^ Glišić, Venceslav (1970). Teror i zločini nacističke Nemačke u Srbiji 1941-1944. Rad. p. 215.

Легију „Кремплер", састављени од три батаљона албанских квислиншких трупа и муслиманске фашистичке милиције у Санџаку.

- ^ Muñoz 2001, p. 293.

- ^ Simpozijum seoski dani Sretena Vukosavljevića. Opštinska zajednica obrazovanja. 1978. p. 160.

Немци су тада на подручју Сјенице имали ... и око 2000 СС добровољачка легија Кремплер

- ^ "The Moslem Militia and Legion of the Sandjak" in Axis Europa Magazine, Vol. II/III (No. 9), July–August–September 1996, pp.3-14.

- ^ Prcela, John; Guldescu, Stanko (1995). Operation Slaughterhouse. Dorrance Publishing Company.

- ^ Jelić & Strugar 1985, p. 82, 134.

- ^ Banac 1988, p. 101.

- ^ a b Banac 1988, p. 102.

- ^ Jelić & Strugar 1985, p. 144.

- ^ Hadžišehović, Butler & Risaluddin 2003, p. 133.

- ^ "The Post-Soviet States". Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty Research Report. 1994.

Between 25 and 27 October 1991 a referendum was held on the territorial, cultural, and political autonomy of the Sandzak. Its sponsor was the Muslim National Council, which consisted of the SDA, the Muslim Bosnian Organization..

- ^ Bugajski, Janusz (2002). Political Parties of Eastern Europe: A Guide to Politics in the Post-communist Era. M.E. Sharpe. p. 388. ISBN 1-56324-676-7.

- ^ Bartl 1968, p. 63:Die Kaza Bjelopolje ( Akova ) zählte 11 serbische Dörfer mit 216 Häusern, 2 gemischt serbisch - albanische Dörfer mit 25 Häusern und 47 albanische Dörfer mit 1 266 Häusern . Bjelopolje selbst hatte etwa 100 albanische und serbische.

- ^ Bartl 1968, p. 63:Die Stadt Novi Bazar hatte 1 749 serbische und albanische Häuser.

- ^ Bartl 1968, p. 63:Die Kaza Novi Varoš zählte 19 serbische Dörfer mit 298 Häusern und 1 „ bosnisches Dorf mit 200 Häusern .

- ^ Bartl 1968, p. 63

- ^ Bartl 1968, p. 64:Die Bevölkerung des Sancak Novi Bazar war zu etwa 65% islamisiert. Der muslimische Bevölkerung santeil bestand zum grössten Teil aus Albanern.

- ^ Andrea Pieroni, Maria Elena Giusti, & Cassandra L. Quave (2011). "Cross-cultural ethnobiology in the Western Balkans: medical ethnobotany and ethnozoology among Albanians and Serbs in the Pešter Plateau, Sandžak, South-Western Serbia." Human Ecology. 39. (3): 335. "The current population of the Albanian villages is partly "bosniakicised", since in the last two generations a number of Albanian males began to intermarry with (Muslim) Bosniak women of Pešter. This is one of the reasons why locals in Ugao were declared to be "Bosniaks" in the last census of 2002, or, in Boroštica, to be simply "Muslims", and in both cases abandoning the previous ethnic label of "Albanians", which these villages used in the census conducted during "Yugoslavian" times. A number of our informants confirmed that the self-attribution "Albanian" was purposely abandoned in order to avoid problems following the Yugoslav Wars and associated violent incursions of Serbian para-military forces in the area. The oldest generation of the villagers however are still fluent in a dialect of Ghegh Albanian, which appears to have been neglected by European linguists thus far. Additionally, the presence of an Albanian minority in this area has never been brought to the attention of international stakeholders by either the former Yugoslav or the current Serbian authorities."

- ^ Banac, Ivo (2015-06-09). The National Question in Yugoslavia: Origins, History, Politics. Cornell University Press. ISBN 978-1-5017-0194-8.

- ^ Malcolm, Noel (1998). Kosovo : a short history. Internet Archive. London : Macmillan. ISBN 978-0-333-66612-8.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: publisher location (link) - ^ Velović Popović, Bojana M. (2021). "Морфолошке одлике глаголских облика говора Тутина, Новог Пазара и Сјенице" [Morphological features of verb forms in speech from Tutin, Novi Pazar and Sjenica] (PDF). Српски дијалектолошки зборник (68): 197–199.

- ^ Matthew C., Curtis (2012). Slavic-Albanian Language Contact, Convergence, and Coexistence. The Ohio State University. p. 140.

- ^ "Dissemination database search". data.stat.gov.rs. Retrieved 2023-08-09.

- ^ "Statistical Office of Montenegro - MONSTAT". www.monstat.org. Retrieved 2023-08-09.

Sources

[edit]- Bartl, Peter (1968). Die albanischen Muslime zur Zeit der nationalen Unabhängigkeitsbewegung (1878-1912). Otto Harrassowitz Verlag.

- Banac, Ivo (1988). With Stalin Against Tito: Cominformist Splits in Yugoslav Communism. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press. ISBN 0801421861.

- Górak-Sosnowska, Katarzyna (2011). Muslims in Poland and Eastern Europe: Widening the European Discourse on Islam. Warszaw: Faculty of Oriental Studies, University of Warszaw. ISBN 978-8390322957.

- Greble, Emily (2011). Sarajevo, 1941–1945: Muslims, Christians, and Jews in Hitler's Europe. Cornell University Press. ISBN 978-0801461217.

- Greble, Emily (2021). Muslims and the Making of Modern Europe. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0197538807.

- Hadžišehović, Munevera; Butler, Thomas J.; Risaluddin, Saba (2003). A Muslim Woman in Tito's Yugoslavia. College Station, TX: Texas A&M University Press. ISBN 1585443042.

- Jelić, Ivan; Strugar, Novak (1985). War and revolution in Yugoslavia, 1941-1945. Belgrade: Socialist Thought and Practice.

- Mojzes, Paul (2011). Balkan Genocides: Holocaust and Ethnic Cleansing in the Twentieth Century. Rowman & Littlefield. ISBN 978-1442206632.

- Morrison, Kenneth (2018). Nationalism, Identity and Statehood in Post-Yugoslav Montenegro. Bloomsbury Publishing. ISBN 9781474235204.

- Muñoz, Antonio J. (2001). The East Came West: Muslim, Hindu and Buddhist Volunteers in the German Armed Forces, 1941–1945. New York, New York: Axis Europa Books. ISBN 978-1-891227-39-4.

- Jancar-Webster, Barbara (2010). "Women in the Yugoslav National Liberation Movement". In Ramet, Sabrina (ed.). Gender Politics in the Western Balkans: Women and Society in Yugoslavia and the Yugoslav Successor States. Penn State Press. ISBN 978-0271043067.

- John D. Treadway (1983). The Falcon and the Eagle: Montenegro and Austria-Hungary, 1908-1914. Purdue University Press. ISBN 978-1-55753-146-9.

- Zaugg, Franziska Anna (2021). Rekrutierungen für die Waffen-SS in Südosteuropa: Ideen, Ideale und Realitäten einer Vielvölkerarmee. De Gruyter. ISBN 978-3110730777.

Bibliography

[edit]- Poljak, Željko (February 1959). "Sandžak". Kazalo za "Hrvatski planinar" i "Naše planine" 1898—1958 (PDF). Naše planine (in Croatian). Vol. XI. pp. 25–26. ISSN 0354-0650.

External links

[edit]Sandžak

View on GrokipediaEtymology

Name Origins and Historical Usage

The term Sandžak derives from the Ottoman Turkish word sancak, literally meaning "flag" or "banner," which designated a mid-level administrative and military district in the Ottoman Empire, governed by a sancakbeyi (sanjak-bey) who bore the sultan's standard as a symbol of authority.[2][1] This usage reflected the empire's provincial structure, where sanjaks formed subdivisions under larger eyalets or vilayets, often centered on key fortresses or towns for strategic control.[6] The modern region of Sandžak adopted the name from the Ottoman Sanjak of Novi Pazar, an administrative unit established in 1865 during the Tanzimat reforms to consolidate control over the highlands between the Principality of Serbia and the Principality of Montenegro.[3] Named after its administrative center, Novi Pazar (Turkish: Yeni Pazar, "New Bazaar"), the sanjak encompassed territories previously part of the Sanjak of Herzegovina and the Bosnia Eyalet, serving as a deliberate buffer zone to inhibit territorial unification between the two emerging Balkan states.[7] It was reorganized in 1880, when it was detached from the Bosnia Vilayet and attached to the Kosovo Vilayet, and again in 1902, reflecting ongoing Ottoman efforts to manage ethnic and administrative complexities in the area.[3] Following the Ottoman defeat in the First Balkan War of 1912, the Sanjak of Novi Pazar was partitioned: its northern parts, including Novi Pazar, were annexed by the Kingdom of Serbia on December 6, 1912, while southern areas fell to the Kingdom of Montenegro by May 1913, effectively dissolving the Ottoman administrative entity.[3] Despite this division, the name Sandžak endured in ethnic Bosniak (Muslim) and local discourse to describe the transborder cultural and geographic continuity, distinct from official Serbian (Raška) or Montenegrin designations, which emphasize medieval Serbian heritage over Ottoman nomenclature.[1] This historical layering underscores the name's evolution from an imperial administrative label to a marker of regional identity amid post-Ottoman state fragmentation.Geography

Location and Administrative Divisions

Sandžak is a historical and geographical region in southeastern Europe, straddling the border between southwestern Serbia and eastern Montenegro. It lies within the Dinaric Alps, bordered by Bosnia and Herzegovina to the west, Kosovo to the south, and Albania further southwest, with approximate central coordinates around 43°N latitude and 20°E longitude. The region covers an estimated area of about 8,500 square kilometers, though exact boundaries vary by definition as Sandžak lacks formal administrative status in either country.[8][9][10] In Serbia, Sandžak corresponds primarily to the Raška District (Raški okrug) and parts of the Zlatibor District, encompassing six municipalities: Novi Pazar, Sjenica, Tutin, Prijepolje, Priboj, and Nova Varoš. These municipalities, with a combined area of approximately 8,687 square kilometers in the broader Serbian Sandžak zone, are administered under Serbia's provincial structure within the autonomous province of Vojvodina's oversight framework, though geographically distant. Novi Pazar serves as the unofficial regional center due to its population and cultural significance.[9][8][4] In Montenegro, Sandžak includes six to seven municipalities, typically Pljevlja, Bijelo Polje, Rožaje, Plav, Gusinje, and Berane, with occasional inclusion of partial areas from Mojkovac or Andrijevica depending on ethnic and historical delineations. These fall under Montenegro's northern administrative regions without a unified Sandžak district, reflecting the post-Yugoslav decentralization. The division stems from the 1913 Balkan Wars and subsequent state formations, resulting in no cross-border administrative entity today.[9][8][11]Topography and Climate

The Sandžak region consists primarily of mountainous terrain and high plateaus within the Dinaric Alps, featuring karst landscapes, rolling hills, streams, and meadows. It includes the Pešter Plateau, a significant highland area with elevations ranging from 1,150 to 1,492 meters, and forms a geographic cul-de-sac against the Pešter massif in its Serbian portion. The Serbian part spans approximately 8,687 km² with an average elevation of 755 meters, incorporating valleys such as the Ibar and Lim that traverse the highlands and facilitate connectivity.[9][12] The climate is classified as mountainous continental, dominated by long, dense winters with heavy snowfall and shorter, cooler summers, particularly at higher elevations. Exceptions occur in valleys like the Ibar and Vidrenjak, where summers are milder. In Novi Pazar, the region's central city, winters are very cold with average January temperatures around -2°C to 3°C and significant snow, while summers are warm, peaking at about 22°C in July; annual precipitation averages 700-900 mm, distributed throughout the year with peaks in spring and autumn.[13][14][15]History

Medieval and Pre-Ottoman Foundations

The region of Raška, encompassing the area now known as Sandžak, formed the nucleus of the early medieval Serbian state following Slavic migrations into the Balkans during the 6th and 7th centuries CE, where Serb tribes established settlements amid Roman and Byzantine ruins.[16] By the 9th century, Ras—located near modern Novi Pazar—emerged as a central fortified settlement and administrative hub, referenced in Byzantine chronicles like De Administrando Imperio as the borderland core of Serbian principalities under rulers such as Vlastimir (r. c. 830–851), marking the transition from tribal entities to organized polities under nominal Byzantine suzerainty.[17] Stability and consolidation arrived with the Vukanović dynasty, particularly under Stefan Nemanja (r. 1166–1196), who unified fragmented Serbian lands around Raška, defeated Byzantine forces at Pantino in 1163, and laid the foundations for state expansion through military campaigns and alliances, establishing the Nemanjić dynasty that endured until 1371.[18] Nemanja's rule centered power in Ras, which served as the political capital, evidenced by early fortifications and the Church of the Holy Apostles Peter and Paul (dated to the 8th–9th centuries, with later reconstructions), symbolizing the adoption of Orthodox Christianity as a unifying force.[19] Under Nemanja's successors, Raška evolved into a kingdom with Stefan Nemanja's son, Stefan the First-Crowned, receiving royal coronation in 1217 from Archbishop Sava, formalizing ecclesiastical independence via the autocephalous Serbian Orthodox Church.[20] This period saw cultural efflorescence, including the construction of monasteries like Đurđevi Stupovi (founded 1170–1171 by Nemanja) and Sopoćani (built 1260 by Uroš I), which blended Romanesque and Byzantine architectural styles and housed significant frescoes, such as the White Angel at Mileševa (c. 1235), underscoring Raška's role as a crossroads of Western and Eastern Christian influences.[19] The Serbian state peaked as an empire under Stefan Dušan (r. 1331–1355), who proclaimed himself tsar in 1346 and expanded into Byzantine territories, but Raška retained its foundational status until Ottoman incursions in the mid-14th century eroded central authority, culminating in the Battle of Kosovo in 1389 and the fall of regional strongholds by 1459.[21] These pre-Ottoman developments entrenched Orthodox Christian institutions and Serbian ethnogenesis in the region, shaping its demographic and cultural baseline prior to later transformations.[22]Ottoman Administration (15th–19th Centuries)

The Ottoman conquest of the Sandžak region, historically known as Raška, occurred progressively during the mid-15th century, with Isa-beg Ishaković, a prominent Ottoman commander and governor, establishing key settlements including Novi Pazar around 1459 as a strategic administrative and commercial center.[23] [24] Initially integrated into the broader Bosnian administrative framework, the area formed part of the Sanjak of Bosnia, where Ottoman defters recorded local populations and timar distributions to consolidate control through land grants to sipahis.[25] [26] This structure facilitated tax collection via the timar system, emphasizing military obligations and agrarian output, while fostering early Islamic institutions such as mosques and waqfs endowed by figures like Isa-beg.[23] Demographic shifts marked Ottoman rule from the 15th to 17th centuries, characterized by gradual Islamization through voluntary conversions, incentives for Muslim settlers from Anatolia, and emigration or flight of segments of the Christian population amid devshirme levies and economic pressures.[27] [24] By the 16th century, Ottoman registers indicated a mixed but increasingly Muslim-majority composition in urban centers like Novi Pazar, supported by the construction of religious and defensive infrastructure that reinforced Ottoman cultural dominance.[26] Rural areas retained more Christian communities under haraç taxation, though periodic rebellions, such as local uprisings against heavy impositions, underscored tensions in governance.[24] In the 19th century, Tanzimat reforms prompted administrative reorganization, culminating in the formal creation of the Sanjak of Novi Pazar in 1865 as a distinct unit under the Rumelia Eyalet to buffer emerging Serbian and Montenegrin ambitions.[3] These changes introduced centralized bureaucracy, conscription, and legal equality edicts, yet faced resistance from local Muslim elites and Albanian tribes, exacerbating unrest during events like the 1809 insurgent incursions that briefly disrupted control before Ottoman reconquest.[24] By the late 1870s, amid the Great Eastern Crisis, the region's strategic role intensified, with uprisings and reforms highlighting the fraying imperial cohesion while preserving Ottoman sovereignty until the early 20th century.[28]Balkan Wars and Division (1912–1913)

The First Balkan War commenced on October 8, 1912, when Montenegro declared war on the Ottoman Empire and its forces promptly invaded the Sanjak of Novi Pazar from the northwest, targeting areas such as Pljevlja and Bijelo Polje.[29] [30] Concurrently, Serbia, allied within the Balkan League, deployed its Third Army eastward from Niš, advancing through Kosovo and into the Sanjak, where it captured Novi Pazar and surrounding eastern districts by late November 1912 amid the collapse of Ottoman defenses.[31] [3] Ottoman troops, outnumbered and demoralized following defeats elsewhere, offered sporadic resistance but largely withdrew by December 1912, leaving the Sanjak under de facto Serbian and Montenegrin occupation.[1] This rapid conquest displaced residual Ottoman administration and exposed tensions between the allied occupiers, as both sought to consolidate control over the resource-rich, ethnically diverse territory predominantly inhabited by Muslim Slavs and Albanians.[8] To avert clashes between their armies during the armistice period, Serbia and Montenegro negotiated a bilateral partition formalized on August 10, 1913, coinciding with the Treaty of Bucharest that resolved broader Balkan territorial disputes after the Second Balkan War.[30] [32] Under this arrangement, Serbia incorporated the eastern Sanjak—encompassing Novi Pazar, Sjenica, and Prijepolje—while Montenegro gained the western portion, including Pljevlja, Prijepolje's outskirts, and Bijelo Polje, establishing a border that largely persists today.[33] This division disregarded prior great power efforts, such as those post-Congress of Berlin in 1878, to maintain the Sanjak as a demilitarized buffer separating the two Slavic kingdoms, thereby facilitating direct Serbian access to Montenegrin territories and exacerbating Austro-Hungarian concerns over regional stability.[33]Interwar Period and World War I Aftermath

Following the Armistice of 11 November 1918 and the unification of Serbia and Montenegro into the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats, and Slovenes on 1 December 1918, the Sandžak region—previously divided between Serbia and Montenegro after the Balkan Wars of 1912–1913—was formally incorporated into the new state without altering its administrative split: the northern portion (including Novi Pazar) fell under Serbian control within the Užice District, while the southern part (including Pljevlja and Bijelo Polje) remained under Montenegrin administration as part of the Zeta region. This division reflected ongoing tensions from pre-war occupations, exacerbated by post-war violence in southern territories, where Serbian and Montenegrin forces suppressed perceived disloyalty among Muslim populations amid the broader turmoil of demobilization and land disputes.[34] The interwar era (1918–1941) saw centralized governance from Belgrade impose policies that systematically disadvantaged the Muslim majority in Sandžak, including land expropriations under agrarian reforms favoring Orthodox Serbs, restrictions on religious education, and administrative neglect that stifled economic development.[1] Discrimination intensified Serbian nationalism's resurgence, leading to incidents such as the 1924 Sahovići massacre, where several hundred Montenegrin Muslims were killed by local forces amid reprisals for alleged resistance.[35] In response, Muslims formed political bodies like the Yugoslav Muslim Organization (JMO) on 17 January 1919, led by figures such as Mehmed Spaho, to advocate for minority rights and cultural autonomy within the kingdom's multi-ethnic framework, though these efforts yielded limited concessions amid the 1921 Vidovdan Constitution's unitary structure.[8] Repression prompted mass emigration, with approximately 70,000 Muslims fleeing Sandžak for Turkey, Albania, and Western Europe between 1918 and 1941 due to economic hardship, violence, and policies encouraging "colonization" by Serb settlers.[8] The 1921 census recorded around 125,000 Muslims in the region (comprising about 40% of the population in Serbian-held areas), but subsequent undercounting and assimilation pressures eroded communal cohesion.[1] By the late 1930s, under Prime Minister Milan Stojadinović's regime, sporadic border clashes and small-scale expulsions further highlighted the kingdom's failure to integrate Sandžak's Muslims, setting the stage for wartime fractures.[36]World War II Occupations and Partisan Resistance

Following the Axis invasion of Yugoslavia on April 6, 1941, Sandžak was partitioned between German occupation in the northern areas, administered as part of the Territory of the Military Commander in Serbia, and Italian occupation in the southern portions, incorporated into the Governorate of Montenegro and the expanded Albanian puppet state.[37] [38] The demarcation line between these zones fluctuated during 1941 before stabilizing, placing key towns like Novi Pazar near the border and fostering cross-border movements by resistance groups.[37] Italy's capitulation in September 1943 prompted Germany to occupy the former Italian territories, incorporating them into operational zones while relying on local collaborators.[38] [37] In response to occupation, royalist Chetnik forces under Dragoljub Mihailović organized in the Lim-Sandžak area from May 1941, initially cooperating with communist-led Partisans in a joint uprising against Italian forces starting July 13, 1941, which liberated towns such as Bijelo Polje.[38] [37] This alliance fractured by late 1941 amid ideological clashes, with Chetniks increasingly collaborating with Italians and later Germans to combat Partisans, whom they viewed as greater threats to Serbian interests than the Axis powers.[37] Partisans, directed by the Communist Party of Yugoslavia, established operational committees in Sandžak towns including Novi Pazar and Pljevlja under leaders like Rifat Burdžović, focusing on guerrilla warfare and recruitment across ethnic lines despite initial setbacks like the collapse of the Užice Republic in November 1941.[38] To counter the uprising and shield Muslim communities from Chetnik reprisals, Italian authorities armed local Muslim militias in Sandžak starting in mid-1941, forming units that numbered around 2,000 regulars by 1943 and targeted both Partisans and Serb civilians in ethnic violence.[12] These forces, later partially integrated into German command after 1943, participated in battles such as the defense of Sjenica against Partisan assault on December 22, 1941, where communist detachments sought to secure supply routes following their withdrawal from western Serbia.[39] German efforts to bolster collaboration included recruiting Sandžak Muslims into Waffen-SS divisions like Handschar in 1943 and Skanderbeg in 1944, though desertions plagued these units, with over 1,000 from Skanderbeg fleeing in September 1944.[38] [37] Intergroup conflicts intensified ethnic tensions, with Chetniks conducting massacres against Muslims, militias retaliating against Serbs, and Partisans executing reprisals against collaborators, resulting in widespread village burnings and population displacements across the region.[38] By 1944, Partisans dominated through superior organization and Allied support, defeating Axis and collaborator forces in operations like the failed German Operation Draufgänger in July 1944 near Berane, where over 400 German troops deserted to join them.[37] [38] Full liberation occurred by April 1945 as Partisan advances cleared remaining pockets of resistance, paving the way for communist consolidation in Sandžak.[37]Socialist Yugoslavia (1945–1991)

Following the establishment of the Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia in 1945, the Sandžak region was incorporated into the federal structure without any distinct administrative autonomy, remaining divided between the Socialist Republic of Serbia and the Socialist Republic of Montenegro.[40][41] The pre-war Novi Pazar district in the Serbian portion was abolished in 1947, with its territories reorganized into two oblasti administered from Užice and Kragujevac, effectively dissolving any regional cohesion.[40] This division reflected the central communist policy of suppressing ethnic particularism in favor of "brotherhood and unity," prioritizing federal integration over historical or geographic unity.[40] The Muslim population of Sandžak, which had included collaborators with Axis forces during World War II, initially encountered suspicion and purges but was gradually integrated into the socialist system through land reforms, collectivization, and participation in the League of Communists of Yugoslavia.[40] A pivotal development occurred in 1968 when Yugoslav authorities constitutionally recognized Muslims as a distinct nationality, equivalent to other South Slavic groups like Serbs and Croats, allowing for cultural and educational expression in the Serbian and Ijekavian dialects.[1] This recognition followed earlier allowances in the 1961 census for self-identification as "Muslim" in terms of nationality, marking a shift from prior classifications that subsumed them under Serb or Croat identities or left them undeclared.[40] Demographic trends in Sandžak during this period showed a rising share of self-identified Muslims, particularly evident in the 1971 census where the category gained widespread adoption in the region, reflecting both natural growth and the appeal of the newly affirmed national identity.[40] Subsequent censuses in 1981 reinforced this, with Muslims forming majorities in several municipalities across the divided territory, though exact regional aggregates were not officially tabulated due to the lack of a unified Sandžak administrative unit.[40] Emigration persisted, including Serbs and Montenegrins seeking industrial jobs in central Serbia or urban centers, while Muslims experienced relative improvements in education and political representation within republican assemblies.[40] Economically, Sandžak benefited from broader Yugoslav investments in infrastructure and light industry, such as textile and mining operations, which elevated living standards toward national averages, though the region remained underdeveloped compared to more industrialized areas.[10] The 1974 constitution granted no special status to Sandžak, embedding it fully within the republics' frameworks and prohibiting organized autonomy movements under the federal emphasis on non-alignment and internal stability.[41] By the late 1980s, following Josip Broz Tito's death in 1980, economic stagnation and rising republican tensions began to strain this integration, foreshadowing ethnic mobilization, but overt demands for regional autonomy remained marginal until the federal dissolution.[42]Wars of Yugoslav Dissolution and 1991 Autonomy Referendum

As Yugoslavia began to disintegrate in 1991 amid rising nationalist tensions, the Bosniak population in Sandžak, fearing marginalization within the newly assertive Serbian-dominated rump Yugoslavia, pursued greater regional autonomy to preserve their ethnic and cultural identity.[8] The Party of Democratic Action (SDA) and the Muslim National Council of Sandžak (MNVS) organized a referendum on autonomy, held from 25 to 27 October 1991, in which voters were asked if they supported Sandžak's status as an autonomous region within Yugoslavia with rights to self-governance, cultural preservation, and economic development.[43] Approximately 185,000 residents participated, representing about 70 percent of the eligible population primarily consisting of Bosniaks, with 98 percent approving the autonomy proposal. [44] The referendum excluded one of Sandžak's six municipalities due to logistical issues, and Serbian authorities dismissed it as unconstitutional and unrecognized, viewing it as a separatist move amid the federal crisis.[44] [45] Despite the referendum's symbolic push for autonomy, Sandžak largely escaped the large-scale armed combat that engulfed neighboring Bosnia and Herzegovina from 1992 to 1995, owing to its mixed ethnic composition, strategic position, and lack of unified separatist militias capable of sustaining insurgency.[4] However, the outbreak of the Bosnian War intensified ethnic pressures, with Yugoslav People's Army (JNA) forces encircling key towns like Novi Pazar to exert psychological control and deter cross-border support for Bosniak fighters in Bosnia, while local Serb paramilitaries and police engaged in sporadic intimidation tactics against Bosniaks. Belgrade escalated state-sponsored violence, including arson attacks on Bosniak homes, beatings, and arrests, as part of a broader policy to suppress perceived loyalties to Bosnian Muslims and encourage emigration, resulting in hundreds of incidents documented between 1992 and 1993.[43] [44] These actions, while not rising to systematic ethnic cleansing on the scale seen in Bosnia, created an atmosphere of sustained fear, displacing an estimated several thousand Bosniaks and straining interethnic relations without provoking full-scale retaliation.[4] Firebombings and military harassment persisted into the late 1990s, only abating after the 1999 NATO intervention in Kosovo shifted regional dynamics.[4]Post-2000 Reforms and State Dissolution Impacts

Following the overthrow of Slobodan Milošević on October 5, 2000, Serbia pursued democratic reforms that included normative advancements in minority rights, such as the establishment of national councils for ethnic groups and exemptions for minority parties from the 5% electoral threshold introduced via proportional representation changes in late 2000.[46][47] These measures enabled Bosniak political parties in Sandžak, including the Party of Democratic Action (SDA) and List for Sandžak, to secure parliamentary seats and local influence, with Bosniaks holding majorities in three Serbian municipalities (Novi Pazar, Sjenica, and Tutin) by the mid-2000s.[48] However, implementation lagged due to political patronage and insufficient funding for cultural and educational initiatives, perpetuating grievances over underdevelopment and discrimination.[49][4] Demands for territorial autonomy, which had intensified during the 1990s wars, diminished after democratization in both Serbia and Montenegro, as Bosniak leaders prioritized integration into state structures over secessionist rhetoric to avoid alienating central governments amid EU accession pressures.[1] The 2001 formation of the Bosniak National Council in Serbia formalized advocacy for cultural autonomy, focusing on language rights, religious education, and media rather than political separation, though sporadic calls for regional self-governance persisted, as evidenced by Mufti Muamer Zukorlić's 2016 accusations of state "genocide" against Bosniaks and autonomy proposals.[50] Decentralization laws enacted in 2002 and expanded in 2007 devolved powers to municipalities, benefiting Sandžak's local governance in areas like budgeting and services, but stopped short of regional consolidation, leaving the area divided into the Raška District without unified Sandžak-level administration.[51][52] The 2003 Constitutional Charter creating the State Union of Serbia and Montenegro briefly preserved cross-border cohesion for Sandžak, but Montenegro's independence referendum on May 21, 2006—passing with 55.5% approval and formalizing separation on June 3—permanently split the region, with Serbia retaining six municipalities (Novi Pazar, Sjenica, Tutin, Prijepolje, Nova Varoš, and Priboj) and Montenegro three (Rožaje, Pljevlja, and Bijelo Polje).[41] Bosniaks, comprising about 15% of Montenegro's population, overwhelmingly supported independence (over 90% in Sandžak municipalities), expecting reciprocal autonomy arrangements, but post-independence Montenegrin governments under Milo Đukanović failed to deliver on pre-referendum pledges, leading to disillusionment and heightened identity politics.[10][53] This division exacerbated economic fragmentation, as trade and familial ties across the new border faced customs barriers, though EU-facilitated regional cooperation mitigated some disruptions; synthetic control analyses indicate no long-term GDP impact on Serbia's Sandžak but transitory gains for Montenegro overall.[54] In Serbia, the 2006 Constitution reinforced minority quotas (e.g., 19 reserved parliamentary seats, including for Bosniaks), yet Sandžak's Bosniak population—estimated at 150,000–200,000—continued facing socioeconomic marginalization, with unemployment rates exceeding 40% in key municipalities as of 2011 and uneven access to higher education in Bosnian language.[55] Autonomy advocacy revived intermittently, as in 2019 proposals for a Sandžak assembly, but Belgrade consistently rejected them to preserve territorial integrity, viewing them as incompatible with post-Yugoslav stability.[56] In Montenegro, Bosniaks gained vice-presidential representation and cultural councils, but cross-border unity eroded, fostering parallel Islamic structures and mild radicalization risks amid unfulfilled integration promises.[1][57] Overall, while reforms curbed overt violence, the dissolution entrenched administrative silos, sustaining low-level tensions without resolving core demands for equitable development.[58]Demographics

Ethnic Composition and Distribution

The Sandžak region features a bifurcated ethnic landscape, with Bosniaks—South Slavic Muslims—forming dense majorities in central and eastern municipalities, while Serbs predominate in western and northern areas. This distribution stems from historical settlement patterns, including Ottoman-era Islamization among local Slavs and subsequent migrations. Official censuses provide the primary empirical measure, revealing Bosniaks as the plurality or majority in core areas like Novi Pazar and Rožaje, alongside significant Serb populations in peripheral zones. Smaller groups include Albanians in southern enclaves, Roma scattered across settlements, and negligible numbers of Croats, Gorani, and others.[59] In Serbia's portion of Sandžak, the 2022 census records Bosniaks totaling 153,801 nationwide, with over 90% concentrated in the region's municipalities: Novi Pazar (85,204 Bosniaks, comprising 81% of the local population), Tutin (over 95%, with a municipal population of 33,053), and Sjenica (approximately 75%). Serbs, numbering around 120,000-140,000 in these areas, hold majorities exceeding 80% in Nova Varoš and Priboj, with mixed demographics in Prijepolje (roughly 55% Serb, 40% Bosniak). These figures reflect self-declared identities, with minor Roma (1-2%) and Albanian presences. Montenegro's Sandžak municipalities host the bulk of the country's 58,956 Bosniaks per the 2023 census, concentrated in Rožaje (over 90%, population around 15,000), Petnjica, and Gusinje, where they exceed 70-80%. Plav features a tripartite split with Bosniaks at about 50%, Albanians at 40%, and Montenegrins/Serbs at 10%. Serbs and Montenegrins dominate Pljevlja (over 60% combined) and Bijelo Polje (around 50% Serbs/Montenegrins, 30% Bosniaks). Albanians total 30,978 nationally but cluster in Plav-Gusinje, comprising under 5% regionally.[60]| Municipality | Country | Bosniaks (%) | Serbs/Montenegrins (%) | Albanians (%) | Others (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Novi Pazar | Serbia | 81 | 13 | <1 | 6 |

| Tutin | Serbia | 95 | 3 | 0 | 2 |

| Sjenica | Serbia | 75 | 20 | 0 | 5 |

| Prijepolje | Serbia | 40 | 55 | 0 | 5 |

| Rožaje | Montenegro | >90 | <5 | 0 | <5 |

| Plav | Montenegro | 50 | 10 | 40 | 0 |

| Pljevlja | Montenegro | 20 | 60 | 0 | 20 |