Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Sea lane

View on WikipediaThis article needs additional citations for verification. (December 2009) |

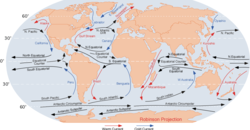

A sea lane, sea road or shipping lane is a regularly used navigable route for large water vessels (ships) on wide waterways such as oceans and large lakes, and is preferably safe, direct and economic. During the Age of Sail, they were determined by the distribution of land masses but also by the prevailing winds, whose discovery was crucial for the success of long maritime voyages. Sea lanes are very important for seaborne trade.

History

[edit]

The establishment of the North Atlantic sea lanes was inspired by the sinking of the US mail steamer SS Arctic by collision with the French steamer SS Vesta in October 1854 which resulted in the loss of over 300 lives, including the family of the Arctic's owner[1]. Lieutenant M. F. Maury of the US Navy first published a section titled "Steam Lanes Across the Atlantic" in his 1855 Sailing Directions proposing sea lanes along the 42 degree latitude. A number of international conferences and committees were held in 1866, 1872, 1887, 1889, and 1891[2] all of which left the designation of sea lanes to the principal trans-Atlantic steamship companies at the time; Cunard, White Star, Inman, National Line, and Guion Lines. In 1913–1914 the International Convention for Safety of Life at Sea held in London again reaffirmed that the selection of routes across the Atlantic in both directions is left to the responsibility of the steamship companies.[3]

Shipping lanes came to be by analysing the prevailing winds. The trade winds allowed ships to sail towards the west quickly, and the westerlies allowed ships to travel to the east quickly. As such, the sea lanes are mostly chosen to take full advantage of these winds. Currents are also similarly followed as well, which also gives an advantage to the vessel.[citation needed] Some routes, such as that from Cape Town to Rio de Janeiro (passing Tristan da Cunha), were not able to take advantage of these natural factors.

Main sea lanes may also attract pirates.[citation needed] Pax Britannica was the period from 1815–1914 during which the British Royal Navy controlled most of the key maritime trade routes, and also suppressed piracy and the slave trade. During World War I, as German U-boats began hitting American and British shipping, the Allied trade vessels began to move out of the usual sea lanes to be escorted by naval ships.

Advantages

[edit]

Although most ships no longer use sails (having switched them for engines), the wind still creates waves, and this can cause heeling. As such following the overall direction of the trade winds and westerlies is still very useful. However, it is best for any vessel that is not engaged in trading, or is smaller than a certain length, to avoid the lanes. This is not only because the slight chance of a collision with a large ship that can easily cause a smaller ship to sink, but also because large vessels are much less maneuverable than smaller ships, and need much more depth. Smaller ships can thus easily take courses that are nearer to the shore. Unlike with road traffic, there is no exact "road" a ship must follow, so this can easily be done.

Shipping lanes are the busiest parts of the sea, thus being a useful place for stranded boaters whose boats are sinking or people on a liferaft to boat to, and be rescued by a passing ship.

Threats from shipping lanes

[edit]Shipping lanes may pose threats to some ocean-going craft. Small boats risk conflicts with bigger ships if they follow the shipping lanes. Sections of lanes exist which can be shallow or have some kind of obstruction (such as sand banks). This threat is greatest when passing some narrows, such as between islands in the Indian Ocean (e.g. in Indonesia) as well as between islands in the Pacific (e.g. near the Marquesas islands, Tahiti). Some shipping lanes, such as the Straits of Malacca off Indonesia and Malaysia, and the waters off Somalia, are frequented by pirates operating independently or as privateers (for companies and countries). Passing ships run the risk of being attacked and held for ransom.

Busiest shipping lanes

[edit]The world's busiest shipping lane is the Dover Strait, with 500–600 vessels passing through daily. In 1999, 1.4 billion tonnes gross, carried by 62,500 vessels, passed through the strait.[4] The strait serves as a critical chokepoint for international trade, connecting the North Sea to the English Channel and facilitating maritime traffic between the Atlantic Ocean and key European ports. Its strategic importance has led to the implementation of advanced traffic separation schemes (TSS) and strict maritime regulations to prevent collisions and ensure safe navigation. Other major shipping lanes, such as the Strait of Malacca, the Panama Canal, and the Suez Canal, also play essential roles in global trade by enabling faster and more direct maritime routes. These lanes collectively handle a significant portion of the world's shipping traffic, underscoring their role as vital arteries of international commerce.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Bowen, Frank C. (1930). A Century of Atlantic Travel. Boston: Little, brown, and Company. p. 88.

- ^ Bowen, Frank C. (1930). A Century of Atlantic Travel. Boston: little, Brown, and Company. p. 216.

- ^ Encyclopædia Britannica, Fourteenth Edition, Volume 20 pp. 539, 1938

- ^ "Busiest shipping lane". Guinness World Records. Archived from the original on 2015-05-03. Retrieved 2018-12-11.

Sea lane

View on GrokipediaDefinition and Characteristics

Core Definition

A sea lane is a specific route across oceans or seas regularly traversed by commercial and naval vessels for navigation between ports, designed to optimize safety, efficiency, and predictability in maritime traffic. These lanes often follow natural oceanographic features such as prevailing winds, currents, and bathymetry to minimize fuel consumption and risks from hazards like shoals or adverse weather, while incorporating modern traffic separation schemes (TSS) to segregate opposing flows of traffic.[10][2][11] Under the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS), coastal states may designate sea lanes and prescribe TSS in straits used for international navigation, ensuring transit passage while maintaining navigational freedom; such designations must conform to generally accepted international regulations, as established by the International Maritime Organization (IMO).[12] Unlike rigid airspace corridors enforced by air traffic control, sea lanes function as de facto paths shaped by vessel traffic density, economic incentives, and voluntary adherence to aids like buoys and radar separation zones, with densities varying from sparse transoceanic tracks to congested approaches near major ports.[13][14]Physical and Operational Features

Sea lanes are principally determined by physical oceanographic and geographical constraints, including coastal configurations, prevailing winds, marine currents, water depths, reefs, and ice coverage, which collectively dictate navigable paths and route efficiency.[3] These factors ensure vessels avoid hazards while exploiting favorable conditions; for instance, shallow bathymetry limits drafts of large container ships to depths exceeding 15 meters in many commercial routes, steering traffic away from shoals and submarine features.[15] Ocean currents, driven by wind patterns, density gradients, tides, and Earth's rotation, further influence lane alignment, as ships adjust courses to harness or counter flows like the North Atlantic Drift for transoceanic voyages, reducing fuel consumption by up to 10-20% on optimized paths.[15][16] Operational features emphasize structured traffic management to mitigate collision risks in high-density areas, primarily through Traffic Separation Schemes (TSS) established by the International Maritime Organization (IMO). TSS divide waterways into designated one-way lanes separated by buffer zones, akin to highway systems, mandatory in straits and approaches where vessel convergence exceeds safe thresholds, such as the Dover Strait handling 500-600 ships daily.[9][10] These schemes, often integrated with Vessel Traffic Services (VTS), employ radar, Automatic Identification System (AIS) signals, and aids like cardinal buoys to enforce separation and alert to hazards, enhancing navigational safety without rigid global enforcement outside designated zones.[9][17] Routeing measures may also incorporate precautionary areas for speed reductions or maneuvers, adapting to local bathymetry and traffic volumes to prevent groundings and maintain throughput.[18]Historical Development

Ancient and Medieval Trade Routes

The earliest documented sea lanes emerged in the Mediterranean during the Bronze Age, with Minoan Crete facilitating trade in metals, pottery, and textiles across the Aegean and eastern Mediterranean by approximately 2000 BCE, leveraging coastal hopping routes to connect Cyprus, Egypt, and Anatolia.[19] Egyptian voyages along the Red Sea to Punt (modern Somalia and Yemen) for incense, ebony, and gold date to around 2500 BCE, establishing seasonal outbound routes in winter and return in summer to exploit predictable winds. These routes relied on rudimentary navigation via stars and landmarks, prioritizing sheltered coastal paths over open-sea crossings to mitigate risks from unpredictable weather and piracy. Phoenician city-states, centered in modern Lebanon from circa 1200 BCE, revolutionized Mediterranean sea lanes by developing keel-equipped ships capable of extended voyages, linking Tyre and Sidon to Iberia for tin, North Africa for ivory, and the Levant for dyes like Tyrian purple. Their network, spanning over 2,000 miles, facilitated the exchange of cedar wood, glass, and metals, with colonies like Carthage serving as trade hubs by 814 BCE.[20] Greek expansion from the 8th century BCE extended these lanes westward to Sicily and the Black Sea for grain and eastward via emporia like Naucratis in Egypt, with triremes enabling bulk transport of olive oil, wine, and ceramics.[21] Under Roman control from the 1st century BCE, the Mediterranean became Mare Nostrum, a unified sea lane system patrolled by the Classis navies, reducing piracy and enabling year-round trade in grain from Egypt to Rome—up to 400,000 tons annually via Ostia—alongside spices and silks from the East.[22] Roman extension into the Indian Ocean, documented in the Periplus of the Erythraean Sea (circa 40–70 CE), utilized monsoon winds for direct sailings from Red Sea ports like Berenice to Muziris in India, covering 1,500 nautical miles in 40 days and importing pepper, cotton, and gems valued at millions of sesterces yearly.[23] In the medieval period, Arab mariners dominated Indian Ocean sea lanes following the 7th-century Islamic expansions, employing dhows with lateen sails to navigate monsoon circuits from Basra and Siraf in the Persian Gulf to Gujarat, Malabar, and Zanzibar for spices, ivory, and slaves, with peak volumes reaching hundreds of ships annually by the 9th century.[24] These routes supplanted overland paths, connecting to Chinese ports via the Strait of Malacca and integrating with the Red Sea feeder to Alexandria, where goods like cloves and porcelain were transshipped to Europe.[25] Italian city-states like Venice and Genoa controlled Mediterranean lanes from the 11th century, with Venetian galleys forming convoys (mude) to Constantinople and Acre for silk, alum, and slaves, amassing fleets of up to 200 vessels by 1300 and generating revenues exceeding 1 million ducats yearly through state-protected routes.[26] In northern waters, Norse Vikings established North Atlantic sea lanes from the 8th century, using longships to trade walrus ivory, furs, and amber from Norway to Dublin and York, extending to Iceland by 870 CE and Greenland by 985 CE via Faeroe Islands waypoints, with archaeological evidence of sustained exchanges up to 1,000 tons of goods.[27] These routes emphasized seasonal sailing and overland portages to counter open-ocean hazards, underscoring the causal role of technological adaptations in sustaining long-distance maritime commerce.Age of Sail and Industrial Revolution

The Age of Sail, extending from the mid-16th century to the mid-19th century, relied on wooden sailing vessels powered by wind, with sea lanes optimized for prevailing trade winds and ocean currents to facilitate long-distance trade and exploration.[28] European colonial powers established dominant routes, including the Spanish convoys transporting silver from the Americas across the Atlantic and the Portuguese pathway around the Cape of Good Hope to India and the East Indies, which became foundational for global commerce.[29] These lanes supported the triangular trade system in the Atlantic, involving Europe, Africa, and the Americas, where ships carried manufactured goods to Africa, enslaved people to the Americas, and commodities like sugar and tobacco back to Europe, peaking in the 18th century with British and Dutch fleets controlling key segments.[29] Wind patterns, such as the northeast trade winds in the Atlantic and Indian Oceans, dictated eastward voyages, while westerly winds enabled returns, minimizing time against contrary winds and enabling empires to project naval power along these predictable paths.[30] By the late 18th century, clipper ships like the British Cutty Sark, launched in 1869, exemplified peak sailing efficiency on routes to China for tea and opium, achieving speeds up to 17 knots but remaining vulnerable to seasonal calms and storms.[28] Naval engagements, such as the British victory at Trafalgar in 1805, secured control over these lanes, underscoring their strategic value in sustaining colonial economies. The Industrial Revolution, beginning in Britain around 1760 and accelerating maritime transformation by the 1830s, introduced steam-powered iron ships that reduced dependence on winds, allowing more flexible sea lanes and increased cargo capacity.[31] The first reliable transatlantic steam crossing occurred in 1838 with the SS Great Western, halving travel times compared to sailing packets and enabling scheduled services that boosted trade volumes in raw materials like cotton for textile mills.[31] Steam propulsion required coaling stations along routes, initially limiting range but spurring infrastructure in ports from Gibraltar to Singapore. The opening of the Suez Canal on November 17, 1869, marked a pivotal shift, providing a direct 120-mile waterway linking the Mediterranean to the Red Sea and shortening the Europe-to-India voyage from approximately 10,400 nautical miles around Africa to 6,200 miles.[32] This canal favored steamships, which could navigate without wind, leading to a 178 percent surge in steam vessel traffic on Asian routes between 1869 and 1874, while hastening the obsolescence of sailing ships on long-haul trades.[33] By altering Eastern and Australasian shipping patterns, the canal integrated industrial economies more tightly, with annual tonnage through Suez rising from 500,000 tons in 1870 to over 19 million by 1913, reflecting the era's exponential growth in global commodity flows.[34]20th Century and Post-WWII Expansion

The 20th century marked a period of intensified use and formalization of sea lanes, driven by the expansion of global trade amid industrialization and the shift to powered vessels. By the early 1900s, steamships had largely replaced sail, enabling more predictable and efficient routing along established oceanic paths, with Britain's merchant fleet comprising 40% of world tonnage around 1900.[35] World Wars I and II disrupted these lanes through submarine warfare and blockades, yet spurred technological adaptations like convoy systems for protection, which influenced post-war routing strategies.[10] Post-World War II reconstruction, facilitated by initiatives like the Marshall Plan, catalyzed a surge in international seaborne trade, with shipping carrying the majority of global commerce by volume. From 1968 onward, seaborne trade volumes expanded dramatically, reflecting broader economic globalization and the U.S.-led maritime order that secured open sea lanes via naval presence.[36] [37] Containerization, pioneered by Malcolm McLean in 1956 with the first container ship voyage from Newark to Houston, revolutionized sea lane operations by standardizing cargo handling, slashing loading times from days to hours, and reducing costs by up to 90%, thereby expanding viable trade routes and port networks.[38] [39] Parallel advancements included the rise of very large crude carriers (VLCCs) in the 1960s and 1970s, accommodating the booming oil trade from the Middle East, which intensified traffic along routes like the Strait of Hormuz to Europe and the U.S. Global shipping tonnage grew steadily post-war; average vessel size increased markedly after 1945, with container shipping alone rising about 10% annually from 1985 to reach 1.3 billion tonnes by 2008, underscoring the era's scale-up in lane capacity.[40] [41] These developments entrenched sea lanes as arteries of economic interdependence, though vulnerabilities to chokepoints like the [Suez Canal](/page/Suez Canal)—nationalized in 1956—highlighted ongoing strategic dependencies.[42]Strategic and Economic Importance

Role in Global Trade and Logistics

Sea lanes serve as the primary arteries of global trade, carrying over 80% of the volume of internationally traded goods. In 2023, seaborne trade totaled 12.3 billion tons, reflecting a 2.4% increase from the previous year, with projections for 2% growth in 2024 driven by demand for commodities and containerized cargo.[5] This reliance on maritime routes arises from their capacity to transport vast quantities of bulk dry cargo, such as iron ore and coal, which account for roughly 50% of total seaborne volumes, alongside tankers moving over 3 billion tons of crude oil and petroleum products annually.[5] The efficiency of sea lanes, optimized for prevailing winds and ocean currents, minimizes fuel consumption and operational costs compared to air or land alternatives, making them indispensable for cost-sensitive logistics of raw materials and intermediate goods.[43] In logistics, sea lanes integrate with global supply chains by enabling just-in-time delivery models, where synchronized container shipping reduces inventory holding costs for manufacturers and retailers worldwide. Over 70% of global trade value transits these routes, supporting intercontinental flows that link production hubs in Asia with consumer markets in Europe and North America.[44] Standardized shipping lanes facilitate predictive routing and scheduling, with vessels adhering to established paths to avoid hazards and leverage navigational aids, thereby enhancing reliability amid complex multimodal networks involving ports, rail, and trucking. Disruptions, such as those from geopolitical events, can cascade through supply chains, amplifying costs and delays, as evidenced by the 2021 Suez Canal blockage which halted approximately $9 billion in daily trade.[45] The strategic designation of sea lanes also promotes safety and regulatory compliance, with international agreements like those under the International Maritime Organization ensuring standardized traffic separation schemes in high-density areas. This framework supports the annual movement of more than 11 billion tons of cargo, underpinning economic interdependence by providing scalable capacity for e-commerce-driven container growth and energy imports critical to industrial economies.[46] By concentrating trade flows, sea lanes amplify economies of scale in vessel design and port infrastructure, fostering innovations like larger ultra-large container ships capable of carrying over 24,000 TEU, which further entrenches maritime dominance in global logistics.[5]Geopolitical and Military Significance

Sea lanes constitute critical arteries for global trade, carrying approximately 90% of internationally traded goods by volume, rendering their security indispensable for economic stability and national power projection.[47] [45] Control of these routes allows states to exert influence over adversaries by threatening disruptions, as evidenced by historical naval strategies emphasizing sea lines of communication (SLOCs).[48] Maritime chokepoints, such as the Strait of Hormuz and Bab el-Mandeb, amplify this significance by funneling disproportionate trade volumes— for instance, the Strait of Hormuz handles about 20% of global oil trade—making them focal points for geopolitical leverage.[49] [50] From a military perspective, dominant naval powers maintain capabilities to secure SLOCs against blockades, interdictions, or asymmetric threats, a principle rooted in Alfred Thayer Mahan's 19th-century advocacy for concentrating forces at key chokepoints to command the seas.[48] The United States Navy, for example, routinely conducts freedom of navigation operations and escorts to protect commerce, underscoring sea control as essential for power projection and deterrence.[47] In alliance frameworks like NATO, strategies prioritize maritime domain awareness, anti-submarine warfare, and rapid response to ensure open sea lanes amid rising great-power competition.[51] Contemporary conflicts illustrate these vulnerabilities: Houthi missile and drone attacks on shipping in the Red Sea since October 2023 have forced rerouting around Africa, increasing transit times by up to 10 days and costs by 40%, while highlighting the role of state-backed proxies in contesting chokepoints.[44] Similarly, territorial disputes in the South China Sea, where China has militarized artificial islands, challenge international norms of free passage, prompting counterbalancing naval patrols by the U.S. and allies to uphold unimpeded navigation.[52] Such incidents underscore that disruptions at just a few chokepoints can threaten over 50% of global maritime trade, incentivizing investments in resilient supply chains and multilateral security arrangements.[52]Major Routes and Chokepoints

Busiest Global Shipping Lanes

The busiest global shipping lanes are primarily assessed by vessel traffic volume, with the English Channel leading as the most traversed waterway, handling over 500 vessels daily and approximately 67,600 ships annually as of 2023.[53] This narrow passage between the United Kingdom and France facilitates about 20% of global oil tanker traffic and significant container shipments between European ports and the wider world.[45] Its high density stems from proximity to major ports like Rotterdam, Antwerp, and Hamburg, though it poses navigational challenges due to congestion and cross-channel ferries.[54] The Strait of Malacca ranks among the top by both vessel numbers and cargo tonnage, with around 120,000 ships transiting yearly, carrying roughly 25% of global trade goods, including critical energy supplies from the Middle East to East Asia.[54] Connecting the Indian Ocean to the South China Sea, this chokepoint between Indonesia, Malaysia, and Singapore handles over 80,000 barrels of oil per day and supports intra-Asian trade flows.[55] Despite alternatives like the Lombok Strait, its efficiency for large vessels maintains dominance, though piracy risks and shallow drafts limit larger ship sizes.[56] Other prominent lanes include the Suez Canal, which saw about 18,000 to 19,000 vessel transits in recent pre-disruption years, channeling 12-15% of global trade and nearly one-third of container traffic between Asia and Europe.[57] The Panama Canal processes around 14,000 ships annually, vital for North-South American and transpacific routes, though drought-induced restrictions have reduced capacity since 2023.[54] The Strait of Hormuz, handling 20% of global oil shipments or about 21 million barrels daily, underscores energy-focused busyness, linking Persian Gulf producers to international markets.[55]| Shipping Lane | Approximate Annual Vessel Transits | Key Cargo/Trade Share |

|---|---|---|

| English Channel | 67,600 (2023) | 20% oil tankers; European container hub[53][45] |

| Strait of Malacca | 120,000 | 25% global trade; oil to Asia[54] |

| Suez Canal | 18,000-19,000 | 12-15% world trade; Asia-Europe containers[57] |

| Panama Canal | 14,000 | Transpacific and Americas routes[54] |

| Strait of Hormuz | ~15,000 (tankers dominant) | 20% global oil[55] |

Critical Maritime Chokepoints

Maritime chokepoints are narrow waterways that constrain shipping routes and handle disproportionate shares of global trade, particularly in oil, liquefied natural gas (LNG), and containerized goods, making them vulnerable to disruptions from geopolitical tensions, accidents, or environmental factors.[58] These passages facilitate the movement of approximately 90% of international trade by volume, with energy commodities comprising a significant portion.[49] In 2023, disruptions at key chokepoints like the Suez Canal and Panama Canal reduced transits by over 50% compared to prior peaks, extending shipping distances and elevating freight rates.[5] The Strait of Hormuz, connecting the Persian Gulf to the Gulf of Oman, is among the most critical, with 14 million barrels per day (bpd) of oil and 16.3 billion cubic feet per day (Bcfd) of LNG transiting in recent years, representing about 20% of global oil trade.[59] Primarily controlled by Iran and Oman, it serves as the primary export route for Middle Eastern energy to Asia and Europe, with limited alternatives such as pipelines.[58] The Strait of Malacca, linking the Indian Ocean to the South China Sea, handles around 24 million bpd of oil in 2024, supporting energy flows from the Middle East to major Asian consumers like China and India.[59] This congested passage, bordered by Indonesia, Malaysia, and Singapore, also carries 30% of global LNG trade and faces risks from piracy and vessel collisions due to high traffic volumes.[58] Suez Canal connects the Mediterranean Sea to the Red Sea, enabling ~10% of global maritime trade and 22% of containerized cargo, though oil volumes stand at about 4.5 million bpd.[5][58] Since late 2023 Houthi attacks in the adjacent Red Sea, transits have fallen over 50%, forcing rerouting around the Cape of Good Hope and increasing transit times by up to 10-14 days.[5] The Bab el-Mandeb Strait, between the Horn of Africa and Yemen, provides access from the Red Sea to the Gulf of Aden, with 6.2 million bpd of oil in 2022, integral to Suez-linked shipments.[58] Recent attacks have halved flows through the combined Suez-Bab el-Mandeb system, underscoring its role in 12% of global oil trade pre-disruption.[59] Panama Canal links the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans, handling ~3% of global trade and 1 million bpd of oil, but drought since 2022 has restricted daily transits to 24-34 vessels from a prior average of 38.[5][58] Alternatives involve longer routes around South America, adding costs and time. Other notable chokepoints include the Turkish Straits (2.5 million bpd oil, key for Russian and Caspian exports) and Danish Straits (3 million bpd, for Baltic oil).[58] These passages amplify global energy security risks, as closures could spike prices and strain supply chains, with no single chokepoint exceeding 30% of trade but collectively forming indispensable arteries.[59]| Chokepoint | Primary Commodities and Volumes (Recent Data) | Strategic Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Strait of Hormuz | 14M bpd oil, 16.3 Bcfd LNG (2024) | 20% global oil; geopolitical flashpoint |

| Strait of Malacca | 24M bpd oil (2024); 30% global LNG | Asia energy hub; congestion risks |

| Suez Canal | 4.5M bpd oil; 10% global trade (pre-2023) | Europe-Asia shortcut; attack-disrupted |

| Bab el-Mandeb | 6.2M bpd oil (2022) | Red Sea gateway; Houthi threats |

| Panama Canal | 1M bpd oil; 3% global trade | Drought-limited; inter-ocean link |