Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Spinal cord injury

View on Wikipedia

| Spinal cord injury | |

|---|---|

| |

| MRI of a fractured and dislocated cervical vertebra (C4) in the neck that is compressing the spinal cord | |

| Specialty | Neurosurgery |

| Types | Complete, incomplete[1] |

| Diagnostic method | Based on symptoms, medical imaging[1] |

| Treatment | Spinal motion restriction, intravenous fluids, vasopressors[1] |

| Frequency | c. 12,000 annually in the United States[2] |

A spinal cord injury (SCI) is damage to the spinal cord that causes temporary or permanent changes in its function. It is a destructive neurological and pathological state that causes major motor, sensory and autonomic dysfunctions.[3]

Symptoms of spinal cord injury may include loss of muscle function, sensation, or autonomic function in the parts of the body served by the spinal cord below the level of the injury. Injury can occur at any level of the spinal cord and can be complete, with a total loss of sensation and muscle function at lower sacral segments, or incomplete, meaning some nervous signals are able to travel past the injured area of the cord up to the Sacral S4-5 spinal cord segments. Depending on the location and severity of damage, the symptoms vary, from numbness to paralysis, including bowel or bladder incontinence. Long term outcomes also range widely, from full recovery to permanent tetraplegia (also called quadriplegia) or paraplegia. Complications can include muscle atrophy, loss of voluntary motor control, spasticity, pressure sores, infections, and breathing problems.

In the majority of cases the damage results from physical trauma such as car accidents, gunshot wounds, falls, or sports injuries, but it can also result from nontraumatic causes such as infection, insufficient blood flow, and tumors. Just over half of injuries affect the cervical spine, while 15% occur in each of the thoracic spine, border between the thoracic and lumbar spine, and lumbar spine alone.[1] Diagnosis is typically based on symptoms and medical imaging.[1]

Efforts to prevent SCI include individual measures such as using safety equipment, societal measures such as safety regulations in sports and traffic, and improvements to equipment. Treatment starts with restricting further motion of the spine and maintaining adequate blood pressure.[1] Corticosteroids have not been found to be useful.[1] Other interventions vary depending on the location and extent of the injury, from bed rest to surgery. In many cases, spinal cord injuries require long-term physical and occupational therapy, especially if it interferes with activities of daily living.

In the United States, about 12,000 people annually survive a spinal cord injury.[2] The most commonly affected group are young adult males.[2] SCI has seen great improvements in its care since the middle of the 20th century. Research into potential treatments includes stem cell implantation, hypothermia, engineered materials for tissue support, epidural spinal stimulation, and wearable robotic exoskeletons.[4]

Classification

[edit]

|

|

| The effects of injury depend on the level along the spinal column (left). A dermatome is an area of the skin that sends sensory messages to a specific spinal nerve (right). | |

| |

| Spinal nerves exit the spinal cord between each pair of vertebrae. | |

Spinal cord injury can be traumatic or nontraumatic,[5] and can be classified into three types based on cause: mechanical forces, toxic, and ischemic from lack of blood flow.[6] The damage can also be divided into primary and secondary injury: the cell death that occurs immediately in the original injury, and biochemical cascades that are initiated by the original insult and cause further tissue damage.[7] These secondary injury pathways include the ischemic cascade, inflammation, swelling, cell suicide, and neurotransmitter imbalances.[7] They can take place for minutes or weeks following the injury.[8]

At each level of the spinal column, spinal nerves branch off from either side of the spinal cord and exit between a pair of vertebrae, to innervate a specific part of the body. The area of skin innervated by a specific spinal nerve is called a dermatome, and the group of muscles innervated by a single spinal nerve is called a myotome. The part of the spinal cord that was damaged corresponds to the spinal nerves at that level and below. Injuries can be cervical 1–8 (C1–C8), thoracic 1–12 (T1–T12), lumbar 1–5 (L1–L5),[9] or sacral (S1–S5).[10] A person's level of injury is defined as the lowest level of full sensation and function.[11] Paraplegia occurs when the legs are affected by the spinal cord damage (in thoracic, lumbar, or sacral injuries), and tetraplegia occurs when all four limbs are affected (cervical damage).[12]

SCI is also classified by the degree of impairment. The International Standards for Neurological Classification of Spinal Cord Injury (ISNCSCI), published by the American Spinal Injury Association (ASIA), is widely used to document sensory and motor impairments following SCI.[13] It is based on neurological responses, touch and pinprick sensations tested in each dermatome, and strength of the muscles that control key motions on both sides of the body.[14] Muscle strength is scored on a scale of 0–5 according to the table on the right, and sensation is graded on a scale of 0–2: 0 is no sensation, 1 is altered or decreased sensation, and 2 is full sensation.[15] Each side of the body is graded independently.[15]

| Muscle strength[16] | ASIA Impairment Scale for classifying spinal cord injury[14][17] | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Grade | Muscle function | Grade | Description |

| 0 | No muscle contraction | A | Complete injury. No motor or sensory function is preserved in the sacral segments S4 or S5. |

| 1 | Muscle flickers | B | Sensory incomplete. Sensory but not motor function is preserved below the level of injury, including the sacral segments. |

| 2 | Full range of motion, gravity eliminated | C | Motor incomplete. Motor function is preserved below the level of injury, and more than half of muscles tested below the level of injury have a muscle grade less than 3 (see muscle strength scores, left). |

| 3 | Full range of motion, against gravity | D | Motor incomplete. Motor function is preserved below the level of injury and at least half of the key muscles below the neurological level have a muscle grade of 3 or more. |

| 4 | Full range of motion against resistance | E | Normal. No motor or sensory deficits, but deficits existed in the past. |

| 5 | Normal strength | ||

Complete and incomplete injuries

[edit]| Complete | Incomplete | |

|---|---|---|

| Tetraplegia | 18.3% | 34.1% |

| Paraplegia | 23.0% | 18.5% |

In a "complete" spinal injury, all functions below the injured area are lost, whether or not the spinal cord is severed.[10] An "incomplete" spinal cord injury involves preservation of motor or sensory function below the level of injury in the spinal cord.[19] To be classed as incomplete, there must be some preservation of sensation or motion in the areas innervated by S4 to S5,[20] including voluntary external anal sphincter contraction.[19] The nerves in this area are connected to the very lowest region of the spinal cord, and retaining sensation and function in these parts of the body indicates that the spinal cord is only partially damaged. Incomplete injury by definition includes a phenomenon known as sacral sparing: some degree of sensation is preserved in the sacral dermatomes, even though sensation may be more impaired in other, higher dermatomes below the level of the lesion.[21] Sacral sparing has been attributed to the fact that the sacral spinal pathways are not as likely as the other spinal pathways to become compressed after injury due to the lamination of fibers within the spinal cord.[21]

Spinal cord injury without radiographic abnormality

[edit]Spinal cord injury without radiographic abnormality exists when spinal cord injury is present but there is no evidence of spinal column injury on radiographs.[22] Spinal column injury is trauma that causes fracture of the bone or instability of the ligaments in the spine; this can coexist with or cause injury to the spinal cord, but each injury can occur without the other.[23] Abnormalities might show up on magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), but the term was coined before MRI was in common use.[24]

Central cord syndrome

[edit]

Central cord syndrome, almost always resulting from damage to the cervical spinal cord, is characterized by weakness in the arms with relative sparing of the legs, and spared sensation in regions served by the sacral segments.[25] There is loss of sensation of pain, temperature, light touch, and pressure below the level of injury.[26] The spinal tracts that serve the arms are more affected due to their central location in the spinal cord, while the corticospinal fibers destined for the legs are spared due to their more external location.[26]

The most common of the incomplete SCI syndromes, central cord syndrome usually results from neck hyperextension in older people with spinal stenosis. In younger people, it most commonly results from neck flexion.[27] The most common causes are falls and vehicle accidents; however other possible causes include spinal stenosis and impingement on the spinal cord by a tumor or intervertebral disc.[28]

Anterior spinal artery syndrome

[edit]Anterior spinal artery syndrome also known as anterior spinal cord syndrome, due to damage to the front portion of the spinal cord or reduction in the blood supply from the anterior spinal artery, can be caused by fractures or dislocations of vertebrae or herniated disks.[26] Below the level of injury, motor function, pain sensation, and temperature sensation are lost, while sense of touch and proprioception (sense of position in space) remain intact.[29][27] These differences are due to the relative locations of the spinal tracts responsible for each type of function.

Brown-Séquard syndrome

[edit]Brown-Séquard syndrome occurs when the spinal cord is injured on one side much more than the other.[30] It is rare for the spinal cord to be truly hemisected (severed on one side), but partial lesions due to penetrating wounds (such as gunshot or knife wounds) or fractured vertebrae or tumors are common.[31] On the ipsilateral side of the injury (same side), the body loses motor function, proprioception, and senses of vibration and touch.[30] On the contralateral (opposite side) of the injury, there is a loss of pain and temperature sensations. If the injury is above pyramidal decussation there is contralateral hemiplegia, at the level of decussation there is completed motor loss on both sides and below pyramidal decussation there is ipsilateral hemiplegia.

[28][30]Spinothalamic tracts are in charge for pain and temperature sensation and because these tracts cross to the opposite side and above the spinal cord there is loss on the contralateral side.[32]

Posterior spinal artery syndrome

[edit]Posterior spinal artery syndrome (PSAS), in which just the dorsal columns of the spinal cord are affected, is usually seen in cases of chronic myelopathy but can also occur with infarction of the posterior spinal artery.[33] This rare syndrome causes the loss of proprioception and sense of vibration below the level of injury[27] while motor function and sensation of pain, temperature, and touch remain intact.[34] Usually posterior cord injuries result from insults like disease or vitamin deficiency rather than trauma.[35] Tabes dorsalis, due to injury to the posterior part of the spinal cord caused by syphilis, results in loss of touch and proprioceptive sensation.[36]

Conus medullaris and cauda equina syndromes

[edit]Conus medullaris syndrome is an injury to the end of the spinal cord the conus medullaris, located at about the T12–L2 vertebrae in adults.[30] This region contains the S4–S5 spinal segments, responsible for bowel, bladder, and some sexual functions, so these can be disrupted in this type of injury.[30] In addition, sensation and the Achilles reflex can be disrupted.[30] Causes include tumors, physical trauma, and ischemia.[37] Cauda equina syndrome may also be caused by central disc prolapse or slipped disc, infections such as epidural abscess, spinal haemorrhages, secondary to medical procedures and birth abnormalities.[38]

Cauda equina syndrome (CES) results from a lesion below the level at which the spinal cord ends. Descending nerve roots continue as the cauda equina[35] at levels L2–S5 below the conus medullaris before exiting through intervertebral foraminae.[39] Thus it is not a true spinal cord syndrome since it is nerve roots that are damaged and not the cord itself; however, it is common for several of these nerves to be damaged at the same time due to their proximity.[37] CES can occur by itself or alongside conus medullaris syndrome.[39] It can cause low back pain, weakness or paralysis in the lower limbs, loss of sensation, bowel and bladder dysfunction, and loss of reflexes.[39] There may be bilateral sciatica with central disc prolapse and altered gait.[38] Unlike conus medullaris syndrome, symptoms often occur only on one side of the body.[37] The cause is often compression, e.g. by a ruptured intervertebral disk or tumor.[37] Since the nerves damaged in CES are actually peripheral nerves because they have already branched off from the spinal cord, the injury has better prognosis for recovery of function: the peripheral nervous system has a greater capacity for healing than the central nervous system.[39]

Signs and symptoms

[edit]| Level | Motor Function |

|---|---|

| C1–C6 | Neck flexors |

| C1–T1 | Neck extensors |

| C3, C4, C5 | Supply diaphragm (mostly C4) |

| C5, C6 | Move shoulder, raise arm (deltoid); flex elbow (biceps) |

| C6 | externally rotate (supinate) the arm |

| C6, C7 | Extend elbow and wrist (triceps and wrist extensors); pronate wrist |

| C7, T1 | Flex wrist; supply small muscles of the hand |

| T1–T6 | Intercostals and trunk above the waist |

| T7–L1 | Abdominal muscles |

| L1–L4 | Flex thigh |

| L2, L3, L4 | Adduct thigh; Extend leg at the knee (quadriceps femoris) |

| L4, L5, S1 | abduct thigh; Flex leg at the knee (hamstrings); Dorsiflex foot (tibialis anterior); Extend toes |

| L5, S1, S2 | Extend leg at the hip (gluteus maximus); Plantar flex foot and flex toes |

Signs (observed by a clinician) and symptoms (experienced by a patient) vary depending on where the spine is injured and the extent of the injury.

Dermatome

[edit]A section of skin innervated through a specific part of the spine is called a dermatome, and injury to that part of the spine can cause pain, numbness, or a loss of sensation in the related areas. Paraesthesia, a tingling or burning sensation in affected areas of the skin, is another symptom.[40] A person with a lowered level of consciousness may show a response to a painful stimulus above a certain point but not below it.[41]

Muscle function

[edit]A group of muscles innervated through a specific part of the spine is called a myotome, and injury to that part of the spinal cord can cause problems with movements that involve those muscles. The muscles may contract uncontrollably (spasticity), become weak, or be completely paralysed. Spinal shock, loss of neural activity including reflexes below the level of injury, occurs shortly after the injury and usually goes away within a day.[42] Priapism, an erection of the penis may be a sign of acute spinal cord injury.[43]

The specific parts of the body affected by loss of function are determined by the level of injury. Some signs, such as bowel and bladder dysfunction can occur at any level. Neurogenic bladder involves a compromised ability to empty the bladder and is a common symptom of spinal cord injury. This can lead to high pressures in the bladder that can damage the kidneys.[44]

Spinal cord injury locations

[edit]Cervical spine

[edit]

| Level | Motor Function | Respiratory function |

|---|---|---|

| C1–C4 | Full paralysis of the limbs | Cannot breathe without mechanical ventilation |

| C5 | Paralysis of the wrists, hands, and triceps | Difficulty coughing; may need help clearing secretions |

| C6 | Paralysis of the wrist flexors, triceps, and hands | |

| C7–C8 | Some hand muscle weakness, difficulty grasping and releasing |

Spinal cord injuries at the cervical vertebrae (neck) level result in full or partial tetraplegia, also called quadriplegia.[25] Depending on the specific location and severity of trauma, limited function may be retained. Additional symptoms of cervical injuries include low heart rate, low blood pressure, problems regulating body temperature, and breathing dysfunction.[46] If the injury is high enough in the neck to impair the muscles involved in breathing, the person may not be able to breathe without the help of an endotracheal tube and mechanical ventilator.[10]

Lumbosacral

[edit]The effects of injuries at or above the lumbar or sacral regions of the spinal cord (lower back and pelvis) include decreased control of the legs and hips, genitourinary system, and anus. People injured below level L2 may still have use of their hip flexor and knee extensor muscles.[47] Bowel and bladder function are regulated by the sacral region. It is common to experience sexual dysfunction after injury, as well as dysfunction of the bowel and bladder, including fecal and urinary incontinence.[10]

Thoracic

[edit]In addition to the problems found in lower-level injuries, thorax (chest height) spinal lesions can affect the muscles in the trunk. Injuries at the level of T1 to T8 result in inability to control the abdominal muscles. Trunk stability may be affected; even more so in higher level injuries.[48] The lower the level of injury, the less extensive its effects. Injuries from T9 to T12 result in partial loss of trunk and abdominal muscle control. Thoracic spinal injuries result in paraplegia, but function of the hands, arms, and neck are not affected.[49]

Autonomic dysreflexia

[edit]One condition that occurs typically in lesions above the T6 level is autonomic dysreflexia (AD), in which the blood pressure increases to dangerous levels, high enough to cause potentially deadly stroke.[9][50] It results from an overreaction of the system to a stimulus such as pain below the level of injury, because inhibitory signals from the brain cannot pass the lesion to dampen the excitatory sympathetic nervous system response.[6] Signs and symptoms of AD include anxiety, headache, nausea, ringing in the ears, blurred vision, flushed skin, and nasal congestion.[6] It can occur shortly after the injury or not until years later.[6]

Other autonomic functions may also be disrupted. For example, problems with body temperature regulation mostly occur in injuries at T8 and above.[47]

Neurogenic shock

[edit]Another serious complication that can result from lesions above T6 is neurogenic shock, which results from an interruption in output from the sympathetic nervous system responsible for maintaining muscle tone in the blood vessels.[6][50] Without the sympathetic input, the vessels relax and dilate.[6][50] Neurogenic shock presents with dangerously low blood pressure, low heart rate, and blood pooling in the limbs—which results in insufficient blood flow to the spinal cord and potentially further damage to it.[51]

Complications

[edit]Complications of spinal cord injuries include pulmonary edema, respiratory failure, neurogenic shock, and paralysis below the injury site.

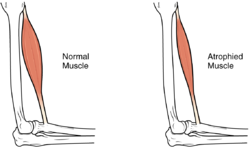

Muscle atrophy

[edit]In the long term, the loss of muscle function can have additional effects from disuse, including muscle atrophy. Immobility also can lead to pressure sores, particularly in bony areas, requiring precautions such as extra cushioning and turning in bed every two hours (in the acute setting) to relieve pressure.[52]

In the long term, people in wheelchairs must shift periodically to relieve pressure.[53] Another complication is pain, including nociceptive pain (indication of potential or actual tissue damage) and neuropathic pain, when nerves affected by damage convey erroneous pain signals in the absence of noxious stimuli.[54] Spasticity, the uncontrollable tensing of muscles below the level of injury, occurs in 65–78% of chronic SCI.[55] It results from lack of input from the brain that quells muscle responses to stretch reflexes.[56] It can be treated with drugs and physical therapy.[56] Spasticity increases the risk of contractures (shortening of muscles, tendons, or ligaments that result from lack of use of a limb); this problem can be prevented by moving the limb through its full range of motion multiple times a day.[57] Another problem lack of mobility can cause is loss of bone density and changes in bone structure.[58][59] Loss of bone density (bone demineralization), thought to be due to lack of input from weakened or paralysed muscles, can increase the risk of fractures.[60] Conversely, a poorly understood phenomenon is the overgrowth of bone tissue in soft tissue areas, called heterotopic ossification.[61] It occurs below the level of injury, possibly as a result of inflammation, and happens to a clinically significant extent in 27% of people.[61]

Cardiovascular and respiratory complications

[edit]People with spinal cord injury are at especially high risk for respiratory and cardiovascular problems, so hospital staff must be watchful to avoid them.[62] Respiratory problems (especially pneumonia) are the leading cause of death in people with SCI, followed by infections, usually of pressure sores, urinary tract infections, and respiratory infections.[63] Pneumonia can be accompanied by shortness of breath, fever, and anxiety.[25]

Deep venous thrombosis

[edit]Another potentially deadly threat to respiration is deep venous thrombosis (DVT), in which blood forms a clot in immobile limbs; the clot can break off and form a pulmonary embolism, lodging in the lung and cutting off blood supply to it.[64] DVT is an especially high risk in SCI, particularly within 10 days of injury, occurring in over 13% in the acute care setting.[65] Preventative measures include anticoagulants, pressure hose, and moving the patient's limbs.[65] The usual signs and symptoms of DVT and pulmonary embolism may be masked in SCI cases due to effects such as alterations in pain perception and nervous system functioning.[65]

Urinary tract infection

[edit]Urinary tract infection (UTI) is another risk that may not display the usual symptoms (pain, urgency, and frequency); it may instead be associated with worsened spasticity.[25] The risk of UTI, likely the most common complication in the long term, is heightened by use of indwelling urinary catheters.[52] Catheterization may be necessary because SCI interferes with the bladder's ability to empty when it gets too full, which could trigger autonomic dysreflexia or damage the bladder permanently.[52] The use of intermittent catheterization to empty the bladder at regular intervals throughout the day has decreased the mortality due to kidney failure from UTI in the first world, but it is still a serious problem in developing countries.[60]

Clinical depression

[edit]An estimated 24–45% of people with spinal cord injuries have major depressive disorder, and the suicide rate is as much as six times that of the rest of the population.[66] The risk of suicide is worst in the first five years after injury.[67] In young people with SCI, suicide is the leading cause of death.[68] Depression is associated with an increased risk of other complications such as UTI and pressure ulcers that occur more when self-care is neglected.[68]

Causes

[edit]

Spinal cord injuries are most often caused by physical trauma.[22][69] Forces involved can be hyperflexion (forward movement of the head); hyperextension (backward movement); lateral stress (sideways movement); rotation (twisting of the head); compression (force along the axis of the spine downward from the head or upward from the pelvis); or distraction (pulling apart of the vertebrae).[70] Traumatic SCI can result in contusion, compression, or stretch injury.[5] It is a major risk of many types of vertebral fracture.[71] Pre-existing asymptomatic congenital anomalies can cause major neurological deficits, such as hemiparesis, to result from otherwise minor trauma.[72]

In the U.S., motor vehicle accidents are the most common cause of SCIs; second are falls, then violence such as gunshot wounds, then sports injuries.[73] Another study from Asia, found that the most common cause of the SCI is fall (31.70%) from various sites such as fall from roof-tops (9.75%), electric pole (7.31%), fall from tree (7.31%) etc. Whereas road traffic accidents count for 19.51%, firearm injuries (12.19%), slipped foot (7.31%) and sports injuries (4.87%). As a result of injury, 26.82%[74]In some countries falls are more common, even surpassing vehicle crashes as the leading cause of SCI.[75] The rates of violence-related SCI depend heavily on place and time.[75] Of all sports-related SCIs, shallow water dives are the most common cause; winter sports and water sports have been increasing as causes while association football and trampoline injuries have been declining.[76] Hanging can cause injury to the cervical spine, as may occur in attempted suicide.[77] Military conflicts are another cause, and when they occur they are associated with increased rates of SCI.[78] Another potential cause of SCI is iatrogenic injury, caused by an improperly done medical procedure such as an injection into the spinal column.[79]

SCI can also be of a nontraumatic origin. The percentage varies by locale, influenced by efforts to prevent trauma.[80] Developed countries have higher percentages of SCI due to degenerative conditions and tumors than developing countries.[81] In developed countries, the most common cause of nontraumatic SCI is degenerative diseases, followed by tumors; in many developing countries the leading cause is infection such as HIV and tuberculosis.[82] SCI may occur in intervertebral disc disease, and spinal cord vascular disease.[83] Spontaneous bleeding can occur within or outside of the protective membranes that line the cord, and intervertebral disks can herniate.[12] Damage can result from dysfunction of the blood vessels, as in arteriovenous malformation, or when a blood clot becomes lodged in a blood vessel and cuts off blood supply to the cord.[84] When systemic blood pressure drops, blood flow to the spinal cord may be reduced, potentially causing a loss of sensation and voluntary movement in the areas supplied by the affected level of the spinal cord.[85] Congenital conditions and tumors that compress the cord can also cause SCI, as can vertebral spondylosis and ischemia.[5] Multiple sclerosis is a disease that can damage the spinal cord, as can infectious or inflammatory conditions such as tuberculosis, herpes zoster or herpes simplex, meningitis, myelitis, and syphilis.[12]

Prevention

[edit]Vehicle-related spinal cord injury is prevented with measures including societal and individual efforts to reduce driving under the influence of drugs or alcohol, distracted driving, and drowsy driving.[86] Other efforts include increasing road safety (such as marking hazards and adding lighting) and vehicle safety, both to prevent accidents, such as routine maintenance and antilock brakes.[86] There are also approaches mitigate the damage of crashes, such as head restraints, air bags, seat belts, and child safety seats.[86] Falls can be prevented by making changes to the environment, such as nonslip materials and grab bars in bathtubs and showers, railings for stairs, child and safety gates for windows.[87] Gun-related injuries can be prevented with conflict resolution training, gun safety education campaigns, and changes to the technology of guns, including trigger locks to improve their safety.[87] Sports injuries can be prevented with changes to sports rules and equipment to increase safety, and education campaigns to reduce risky practices such as diving into water of unknown depth or head-first tackling in association football.[88]

Diagnosis

[edit]A person's presentation in context of trauma or non-traumatic background determines suspicion for a spinal cord injury. The features are namely paralysis, sensory loss, or both at any level. Other symptoms may include incontinence.[90]

A radiographic evaluation using an X-ray, CT scan, or MRI can determine if there is damage to the spinal column and where it is located.[10] X-rays are commonly available[89] and can detect instability or misalignment of the spinal column, but do not give very detailed images and can miss injuries to the spinal cord or displacement of ligaments or disks that do not have accompanying spinal column damage.[10] Thus when X-ray findings are normal but SCI is still suspected due to pain or SCI symptoms, CT or MRI scans are used.[89] CT gives greater detail than X-rays, but exposes the patient to more radiation,[91] and it still does not give images of the spinal cord or ligaments; MRI shows body structures in the greatest detail.[10] Thus it is the standard for anyone who has neurological deficits found in SCI or is thought to have an unstable spinal column injury.[92]

Neurological evaluations to help determine the degree of impairment are performed initially and repeatedly in the early stages of treatment; this determines the rate of improvement or deterioration and informs treatment and prognosis.[93][94] The ASIA Impairment Scale outlined above is used to determine the level and severity of injury.[10]

Management

[edit]Pre-hospital treatment

[edit]

The first stage in the management of a suspected spinal cord injury is geared toward basic life support and preventing further injury: maintaining airway, breathing, circulation, and restricting further motion of the spine.[24]

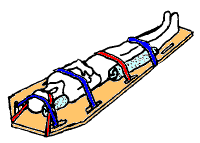

Spinal motion restriction

[edit]In the emergency setting, most people who has been subjected to forces strong enough to cause SCI are treated as though they have instability in the spinal column and have spinal motion restricted to prevent damage to the spinal cord.[95] Injuries or fractures in the head, neck, or pelvis as well as penetrating trauma near the spine and falls from heights are assumed to be associated with an unstable spinal column until it is ruled out in the hospital.[10] High-speed vehicle crashes, sports injuries involving the head or neck, and diving injuries are other mechanisms that indicate a high SCI risk.[96] Since head and spinal trauma frequently coexist, anyone who is unconscious or has a lowered level of consciousness as a result of a head injury is spinal motion restricted.[97]

Devices

[edit]A rigid cervical collar is applied to the neck, and the head is held with blocks on either side and the person is strapped to a backboard.[95] Extrication devices are used to move people without excessively moving the spine[98] if they are still inside a vehicle or other confined space. The use of a cervical collar has been shown to increase mortality in people with penetrating trauma and is thus not routinely recommended in this group.[99]

Modern trauma care includes a step called clearing the cervical spine, ruling out spinal cord injury if the patient is fully conscious and not under the influence of drugs or alcohol, displays no neurological deficits, has no pain in the middle of the neck and no other painful injuries that could distract from neck pain.[35] If these are all absent, no spinal motion restriction is necessary.[98]

If an unstable spinal column injury is moved, damage may occur to the spinal cord.[100] Between 3 and 25% of SCIs occur not at the time of the initial trauma but later during treatment or transport.[24] While some of this is due to the nature of the injury itself, particularly in the case of multiple or massive trauma, some of it reflects the failure to adequately restrict motion of the spine. SCI can impair the body's ability to keep warm, so warming blankets may be needed.[97]

Early hospital treatment

[edit]Initial care in the hospital, as in the prehospital setting, aims to ensure adequate airway, breathing, cardiovascular function, and spinal motion restriction.[101] Imaging of the spine to determine the presence of a SCI may need to wait if emergency surgery is needed to stabilize other life-threatening injuries.[102] Acute SCI merits treatment in an intensive care unit, especially injuries to the cervical spinal cord.[101] People with SCI need repeated neurological assessments and treatment by neurosurgeons.[103] People should be removed from the spine board as rapidly as possible to prevent complications from its use.[104]

Blood pressure

[edit]If the systolic blood pressure falls below 90 mmHg within days of the injury, blood supply to the spinal cord may be reduced, resulting in further damage.[51] Thus it is important to maintain the blood pressure which may be done using intravenous fluids and vasopressors.[105] Vasopressors used include phenylephrine, dopamine, or norepinephrine.[1] Mean arterial blood pressure is measured and kept at 85 to 90 mmHg for seven days after injury.[106]

The CAMPER Trial led by Dr Kwon and subsequent studies by the UCSF TRACK-SCI group (Dhall) have shown that spinal cord perfusion pressure (SCPP) goals are more closely associated with better neurologic recovery than MAP goals. Some institutions have adopted these SCPP goals and lumbar CSF drain placement as a standard of care.[107] The treatment for shock from blood loss is different from that for neurogenic shock, and could harm people with the latter type, so it is necessary to determine why someone is in shock.[105] However it is also possible for both causes to exist at the same time.[1] Another important aspect of care is prevention of insufficient oxygen in the bloodstream, which could deprive the spinal cord of oxygen.[108] People with cervical or high thoracic injuries may experience a dangerously slowed heart rate; treatment to speed it may include atropine.[1]

Steroid treatment

[edit]The corticosteroid medication methylprednisolone has been studied for use in spinal cord injury patients with the hope of limiting swelling and secondary injury.[109] As there does not appear to be long term benefits and the medication is associated with risks such as gastrointestinal bleeding and infection its use is not recommended as of 2018.[1][109] Its use in traumatic brain injury is also not recommended.[104]

Surgery

[edit]Surgery may be necessary, e.g. to relieve excess pressure on the cord, to stabilize the spine, or to put vertebrae back in their proper place.[106] In cases involving instability or compression, failing to operate can lead to worsening of the condition.[106] Surgery is also necessary when something is pressing on the cord, such as bone fragments, blood, material from ligaments or intervertebral discs,[110] or a lodged object from a penetrating injury.[89] Although the ideal timing of surgery is still debated, studies have found that earlier surgical intervention (within 12 hours of injury) is associated with better outcomes.[111] This type of surgery is often referred to as "Ultra-Early", coined by Burke et al. at UCSF. Sometimes a patient has too many other injuries to be a surgical candidate this early.[106] Surgery is controversial because it has potential complications (such as infection), so in cases where it is not clearly needed (e.g. the cord is being compressed), doctors must decide whether to perform surgery based on aspects of the patient's condition and their own beliefs about its risks and benefits.[112] Recent large-scale studies have shown that patients who do undergo earlier surgery (within 12–24 hours) experience significantly lower rates of life-threatening complications and spend less time in hospital and critical care.[113][114]

However, in cases where a more conservative approach is chosen, bed rest, cervical collars, motion restriction devices, and optionally traction are used.[115] Surgeons may opt to put traction on the spine to remove pressure from the spinal cord by putting dislocated vertebrae back into alignment, but herniation of intervertebral disks may prevent this technique from relieving pressure.[116] Gardner-Wells tongs are one tool used to exert spinal traction to reduce a fracture or dislocation and to reduce motion to the affected areas.[117]

Rehabilitation

[edit]

Spinal cord injury patients often require extended treatment in specialized spinal unit or an intensive care unit.[118] The rehabilitation process typically begins in the acute care setting. Usually, the inpatient phase lasts 8–12 weeks and then the outpatient rehabilitation phase lasts 3–12 months after that, followed by yearly medical and functional evaluation.[9] Physical therapists, occupational therapists, recreational therapists, nurses, social workers, psychologists, and other health care professionals work as a team under the coordination of a physiatrist[10] to decide on goals with the patient and develop a plan of discharge that is appropriate for the person's condition.

In the acute phase physical therapists focus on the patient's respiratory status, prevention of indirect complications (such as pressure ulcers), maintaining range of motion, and keeping available musculature active.[119]

For people whose injuries are high enough to interfere with breathing, there is great emphasis on airway clearance during this stage of recovery.[120] Weakness of respiratory muscles impairs the ability to cough effectively, allowing secretions to accumulate within the lungs.[121] As SCI patients have reduced total lung capacity and tidal volume,[122] physical therapists teach them accessory breathing techniques (e.g. apical breathing, glossopharyngeal breathing) that typically are not taught to healthy individuals. Physical therapy treatment for airway clearance may include manual percussions and vibrations, postural drainage,[120] respiratory muscle training, and assisted cough techniques.[121] Patients are taught to increase their intra-abdominal pressure by leaning forward to induce cough and clear mild secretions.[121] The quad cough technique is done lying on the back with the therapist applying pressure on the abdomen in the rhythm of the cough to maximize expiratory flow and mobilize secretions.[121] Manual abdominal compression is another technique used to increase expiratory flow which later improves coughing.[120] Other techniques used to manage respiratory dysfunction include respiratory muscle pacing, use of a constricting abdominal binder, ventilator-assisted speech, and mechanical ventilation.[121]

The amount of functional recovery and independence achieved in terms of activities of daily living, recreational activities, and employment is affected by the level and severity of injury.[123] The Functional Independence Measure (FIM) is an assessment tool that aims to evaluate the function of patients throughout the rehabilitation process following a spinal cord injury or other serious illness or injury.[124] It can track a patient's progress and degree of independence during rehabilitation.[124] People with SCI may need to use specialized devices and to make modifications to their environment in order to handle activities of daily living and to function independently. Weak joints can be stabilized with devices such as ankle-foot orthoses (AFOs) or knee-ankle-foot orthoses (KAFOs), but walking may still require a lot of effort.[125] Increasing activity will increase chances of recovery.[126]

For treatment of paralysis levels in the lower thoracic spine or lower, starting therapy with an orthosis is promising from the intermediate phase (2–26 weeks after the incident).[127][128][129] In patients with complete paraplegia (ASIA A), this applies to lesion heights between T12 and S5. In patients with incomplete paraplegia (ASIA B-D), orthoses are even suitable for lesion heights above T12. In both cases, however, a detailed muscle function test must be carried out to precisely plan the construction with an orthosis.[130]

Prognosis

[edit]

Spinal cord injuries generally result in at least some incurable impairment even with the best possible treatment. The best predictor of prognosis is the level and completeness of injury, as measured by the ASIA impairment scale.[131] The neurological score at the initial evaluation done 72 hours after injury is the best predictor of how much function will return.[132] Most people with ASIA scores of A (complete injuries) do not have functional motor recovery, but improvement can occur.[131][133] Most patients with incomplete injuries recover at least some function.[133] Chances of recovering the ability to walk improve with each AIS grade found at the initial examination; e.g. an ASIA D score confers a better chance of walking than a score of C.[132] The symptoms of incomplete injuries can vary and it is difficult to make an accurate prediction of the outcome. A person with a mild, incomplete injury at the T5 vertebra will have a much better chance of using his or her legs than a person with a severe, complete injury at exactly the same place. Of the incomplete SCI syndromes, Brown-Séquard and central cord syndromes have the best prognosis for recovery and anterior cord syndrome has the worst.[29]

People with nontraumatic causes of SCI have been found to be less likely to develop complete injuries and some complications such as pressure sores and deep vein thrombosis, and to have shorter hospital stays.[12] Their scores on functional tests were better than those of people with traumatic SCI upon hospital admission, but when they were tested upon discharge, those with traumatic SCI had improved such that both groups' results were the same.[12] In addition to the completeness and level of the injury, age and concurrent health problems affect the extent to which a person with SCI will be able to live independently and to walk.[9] However, in general people with injuries to L3 or below will likely be able to walk functionally, T10 and below to walk around the house with bracing, and C7 and below to live independently.[9] New therapies are beginning to provide hope for better outcomes in patients with SCI, but most are in the experimental/translational stage.[4]

One important predictor of motor recovery in an area is presence of sensation there, particularly pain perception.[39] Most motor recovery occurs in the first year post-injury, but modest improvements can continue for years; sensory recovery is more limited.[134] Recovery is typically quickest during the first six months.[135] Spinal shock, in which reflexes are suppressed, occurs immediately after the injury and resolves largely within three months but continues resolving gradually for another 15.[136]

Sexual dysfunction after spinal injury is common. Problems that can occur include erectile dysfunction, loss of ability to ejaculate, insufficient lubrication of the vagina, and reduced sensation and impaired ability to orgasm.[55] Despite this, many people learn ways to adapt their sexual practices so they can lead satisfying sex lives.[137]

Although life expectancy has improved with better care options, it is still not as good as the uninjured population. The higher the level of injury, and the more complete the injury, the greater the reduction in life expectancy.[84] Mortality is very elevated within a year of injury.[84]

Epidemiology

[edit]- 0–15 (3.00%)

- 16–30 (42.1%)

- 31–45 (28.1%)

- 46–60 (15.1%)

- 61–75 (8.50%)

- 76+ (3.20%)

Worldwide, the number of new cases since 1995 of SCI ranges from 10.4 to 83 people per million per year.[106] This wide range of numbers is probably partly due to differences among regions in whether and how injuries are reported.[106] In North America, about 39 people per every million incur SCI traumatically each year, and in Western Europe, the incidence is 16 per million.[139][140] In the United States, the incidence of spinal cord injury has been estimated to be about 40 cases per 1 million people per year or around 12,000 cases per year.[141] In China, the incidence is approximately 60,000 per year.[142]

The estimated number of people living with SCI in the world ranges from 236 to 4187 per million.[106] Estimates vary widely due to differences in how data are collected and what techniques are used to extrapolate the figures.[143] Little information is available from Asia, and even less from Africa and South America.[106] In Western Europe the estimated prevalence is 300 per million people and in North America it is 853 per million.[140] It is estimated at 440 per million in Iran, 526 per million in Iceland, and 681 per million in Australia.[143] In the United States there are between 225,000 and 296,000 individuals living with spinal cord injuries,[144] and different studies have estimated prevalences from 525 to 906 per million.[143]

SCI is present in about 2% of all cases of blunt force trauma.[100] Anyone who has undergone force sufficient to cause a thoracic spinal injury is at high risk for other injuries also.[102] In 44% of SCI cases, other serious injuries are sustained at the same time; 14% of SCI patients also have head trauma or facial trauma.[22] Other commonly associated injuries include chest trauma, abdominal trauma, pelvic fractures, and long bone fractures.[94]

Males account for four out of five traumatic spinal cord injuries.[25] Most of these injuries occur in men under 30 years of age.[10] The average age at the time of injury has slowly increased from about 29 years in the 1970s to 41.[25] In Pakistan, spinal cord injury is more common in males (92.68%) as compared to females in the 20–30 years of age group with a median age of 40 years, although people from 12–70 years of age suffered from spinal cord injury[74] Rates of injury are at their lowest in children, at their highest in the late teens to early twenties, then get progressively lower in older age groups; however rates may rise in the elderly.[145] In Sweden between 50 and 70% of all cases of SCI occur in people under 30, and 25% occur in those over 50.[75] While SCI rates are highest among people age 15–20,[146] fewer than 3% of SCIs occur in people under 15.[147] Neonatal SCI occurs in one in 60,000 births, e.g. from breech births or injuries by forceps.[148] The difference in rates between the sexes diminishes in injuries at age 3 and younger; the same number of girls are injured as boys, or possibly more.[149] Another cause of pediatric injury is child abuse such as shaken baby syndrome.[148] For children, the most common cause of SCI (56%) is vehicle crashes.[150] High numbers of adolescent injuries are attributable in a large part to traffic accidents and sports injuries.[151] For people over 65, falls are the most common cause of traumatic SCI.[5] The elderly and people with severe arthritis are at high risk for SCI because of defects in the spinal column.[152] In nontraumatic SCI, the gender difference is smaller, the average age of occurrence is greater, and incomplete lesions are more common.[132]

History

[edit]

Spinal cord injury has been known to be devastating for millennia; the ancient Egyptian Edwin Smith Papyrus from 2500 BC, the first known description of the injury, says it is "not to be treated".[153] Hindu texts dating back to 1800 BC also mention SCI and describe traction techniques to straighten the spine.[153] The Greek physician Hippocrates, born in the fifth century BC, described SCI in his Hippocratic Corpus and invented traction devices to straighten dislocated vertebrae.[154] But it was not until Aulus Cornelius Celsus, born 30 BC, noted that a cervical injury resulted in rapid death that the spinal cord itself was implicated in the condition.[153] In the second century AD the Greek physician Galen experimented on monkeys and reported that a horizontal cut through the spinal cord caused them to lose all sensation and motion below the level of the cut.[155] The seventh-century Greek physician Paul of Aegina described surgical techniques for treatment of broken vertebrae by removing bone fragments, as well as surgery to relieve pressure on the spine.[153] Little medical progress was made during the Middle Ages in Europe; it was not until the Renaissance that the spine and nerves were accurately depicted in human anatomy drawings by Leonardo da Vinci and Andreas Vesalius.[155]

In 1762, Andre Louis, a surgeon, removed a bullet from the lumbar spine of a patient, who regained motion in the legs.[155] In 1829, Gilpin Smith, a surgeon, performed a successful laminectomy that improved the patient's sensation.[156] However, the idea that SCI was untreatable remained predominant until the early 20th century.[157] In 1934, the mortality rate in the first two years after injury was over 80%, mostly due to infections of the urinary tract and pressure sores,[158] the latter of which were believed to be intrinsic to SCI rather than a result of continuous bedrest.[159] It was not until the second half of the century that breakthroughs in imaging, surgery, medical care, and rehabilitation medicine contributed to a substantial improvement in SCI care.[157] The relative incidence of incomplete compared to complete injuries has improved since the mid-20th century, due mainly to the emphasis on faster and better initial care and stabilization of spinal cord injury patients.[160] The creation of emergency medical services to professionally transport people to the hospital is given partial credit for an improvement in outcomes since the 1970s.[161] Improvements in care have been accompanied by increased life expectancy of people with SCI; survival times have improved by about 2000% since 1940.[162] In 2015/2016 23% of people in nine spinal injury centres in England had their discharge delayed because of disputes about who should pay for the equipment they needed.[163]

Research directions

[edit]

Scientists are investigating various avenues for treatment of spinal cord injury. Therapeutic research is focused on two main areas: neuroprotection and neuroregeneration.[78] The former seeks to prevent the harm that occurs from secondary injury in the minutes to weeks following the insult, and the latter aims to reconnect the broken circuits in the spinal cord to allow function to return.[78] Neuroprotective drugs target secondary injury effects including inflammation, damage by free radicals, excitotoxicity (neuronal damage by excessive glutamate signaling), and apoptosis (cell suicide).[78] Several potentially neuroprotective agents that target pathways like these are under investigation in human clinical trials.[78]

Stem cell transplantation is an important avenue for SCI research: the goal is to replace lost spinal cord cells, allow reconnection in broken neural circuits by regrowing axons, and to create an environment in the tissues that is favorable to growth.[78] A key avenue of SCI research is research on stem cells, which can differentiate into other types of cells—including those lost after SCI.[78] Types of cells being researched for use in SCI include embryonic stem cells, neural stem cells, mesenchymal stem cells, olfactory ensheathing cells, Schwann cells, activated macrophages, and induced pluripotent stem cells.[164] Hundreds of stem cell studies have been done in humans, with promising but inconclusive results.[151] An ongoing Phase 2 trial in 2016 presented data[165] showing that after 90 days, 2 out of 4 subjects had already improved two motor levels and had thus already achieved its endpoint of 2/5 patients improving two levels within 6–12 months. Six-month data was expected in January 2017.[166]

Another type of approach is tissue engineering, using biomaterials to help scaffold and rebuild damaged tissues.[78] Biomaterials being investigated include natural substances such as collagen or agarose and synthetic ones like polymers and nitrocellulose.[78] They fall into two categories: hydrogels and nanofibers.[78] These materials can also be used as a vehicle for delivering gene therapy to tissues.[78]

One avenue being explored to allow paralyzed people to walk and to aid in rehabilitation of those with some walking ability is the use of wearable powered robotic exoskeletons.[167] The devices, which have motorized joints, are put on over the legs and supply a source of power to move and walk.[167] Several such devices are already available for sale, but investigation is still underway as to how they can be made more useful.[167]

Preliminary studies of epidural spinal cord stimulators for motor complete injuries have demonstrated some improvement,[168] and in some cases to enable walking to some degree bypassing the injury.[169][170]

In 2014, Darek Fidyka underwent pioneering spinal surgery that used nerve grafts, from his ankle, to bridge the gap in his severed spinal cord and olfactory ensheathing cells (OECs) to stimulate the spinal cord cells. The surgery was performed in Poland in collaboration with Prof. Geoff Raisman, chair of neural regeneration at University College London's Institute of Neurology, and his research team. The OECs were taken from the patient's olfactory bulbs in his brain and then grown in the lab, these cells were then injected above and below the impaired spinal tissue.[171][38]

There have been a number of advances in technological spinal cord injury treatment, including the use of implants that provided a "digital bridge" between the brain and the spinal cord. In a study published in May 2023 in the journal Nature, researchers in Switzerland described such implants which allowed a 40-year old man, paralyzed from the hips down for 12 years, to stand, walk and ascend a steep ramp with only the assistance of a walker. More than a year after the implant was inserted, he has retained these abilities and was walking with crutches even when the implant was switched off.[172]

In March 2025, researchers reported that a paralyzed man stood for the first time after being injected of neural stem cells to treat his spinal cord injury. The first-of-its-kind study, which is not yet peer reviewed, is encouraging scientists to consider if reprogrammed stem cells can be used in the future to treat people who are fully paralyzed. Reprogrammed cells are adult cells that are reverted to an embryonic-like state, from which they can be coaxed to develop into other cell types.[173]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k ATLS – Advanced Trauma Life Support – Student Course Manual (10th ed.). American College of Surgeons. 2018. pp. 129–144. ISBN 9780996826235.

- ^ a b c "Spinal Cord Injury Facts and Figures at a Glance" (PDF). 2012. Archived from the original (PDF) on 28 June 2018. Retrieved 16 May 2018.

- ^ Anjum, Anam; Yazid, Muhammad Da'in; Fauzi Daud, Muhammad; Idris, Jalilah; Ng, Angela Min Hwei; Selvi Naicker, Amaramalar; Ismail, Ohnmar Htwe Rashidah; Athi Kumar, Ramesh Kumar; Lokanathan, Yogeswaran (2020-10-13). "Spinal Cord Injury: Pathophysiology, Multimolecular Interactions, and Underlying Recovery Mechanisms". International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 21 (20): 7533. doi:10.3390/ijms21207533. ISSN 1422-0067. PMC 7589539. PMID 33066029.

- ^ a b Krucoff MO, Miller JP, Saxena T, Bellamkonda R, Rahimpour S, Harward SC, Lad SP, Turner DA (January 2019). "Toward Functional Restoration of the Central Nervous System: A Review of Translational Neuroscience Principles". Neurosurgery. 84 (1): 30–40. doi:10.1093/neuros/nyy128. PMC 6292792. PMID 29800461.

- ^ a b c d Sabapathy V, Tharion G, Kumar S (2015). "Cell Therapy Augments Functional Recovery Subsequent to Spinal Cord Injury under Experimental Conditions". Stem Cells International. 2015: 1–12. doi:10.1155/2015/132172. PMC 4512598. PMID 26240569.

- ^ a b c d e f Newman, Fleisher & Fink 2008, p. 348.

- ^ a b Newman, Fleisher & Fink 2008, p. 335.

- ^ Yu WY, He DW (September 2015). "Current trends in spinal cord injury repair" (PDF). European Review for Medical and Pharmacological Sciences. 19 (18): 3340–4. PMID 26439026. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2015-12-08.

- ^ a b c d e Cifu & Lew 2013, p. 197.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Office of Communications and Public Liaison, National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke, ed. (2013). Spinal Cord Injury: Hope Through Research. National Institutes of Health. Archived from the original on 2015-11-19.

- ^ Miller & Marini 2012, p. 138.

- ^ a b c d e Field-Fote 2009, p. 5.

- ^ Marino RJ, Barros T, Biering-Sorensen F, Burns SP, Donovan WH, Graves DE, Haak M, Hudson LM, Priebe MM (2003). "International standards for neurological classification of spinal cord injury". The Journal of Spinal Cord Medicine. 26 (Suppl 1): S50–6. doi:10.1080/10790268.2003.11754575. PMID 16296564. S2CID 12799339.

- ^ a b "Standard Neurological Classification of Spinal Cord Injury" (PDF). American Spinal Injury Association & ISCOS. Archived from the original on June 18, 2011. Retrieved 5 November 2015.

- ^ a b Weiss 2010, p. 307.

- ^ Harvey 2008, p. 7.

- ^ Teufack, Harrop & Ashwini 2012, p. 67.

- ^ Field-Fote 2009, pp. 7–8.

- ^ a b Ho CH, Wuermser LA, Priebe MM, Chiodo AE, Scelza WM, Kirshblum SC (March 2007). "Spinal cord injury medicine. 1. Epidemiology and classification". Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation. 88 (3 Suppl 1): S49–54. doi:10.1016/j.apmr.2006.12.001. PMID 17321849.

- ^ Sabharwal 2014, p. 840.

- ^ a b Lafuente DJ, Andrew J, Joy A (June 1985). "Sacral sparing with cauda equina compression from central lumbar intervertebral disc prolapse". Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery, and Psychiatry. 48 (6): 579–81. doi:10.1136/jnnp.48.6.579. PMC 1028376. PMID 4009195.

- ^ a b c Peitzman et al. 2012, p. 288.

- ^ Peitzman et al. 2012, pp. 288–89.

- ^ a b c Peitzman et al. 2012, p. 289.

- ^ a b c d e f Sabharwal 2014, p. 839.

- ^ a b c Snell 2010, p. 170.

- ^ a b c Namdari, Pill & Mehta 2014, p. 297.

- ^ a b Marx, Walls & Hockberger 2013, p. 1420.

- ^ a b Field-Fote 2009, p. 9.

- ^ a b c d e f Field-Fote 2009, p. 10.

- ^ Snell 2010, p. 171.

- ^ Shams; Arain, Saadia; Abdul (2022). "Brown-Séquard Syndrome". Brown Sequard Syndrome. StatPearls. PMID 30844162.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Roos 2012, pp. 249–50.

- ^ Ilyas & Rehman 2013, p. 389.

- ^ a b c Peitzman et al. 2012, p. 294.

- ^ Snell 2010, p. 167.

- ^ a b c d Marx, Walls & Hockberger 2013, p. 1422.

- ^ a b c Bashir, F. "What Is Cauda Equina Syndrome: Causes, Sign, Symptoms, Diagnosis, Treatment And Prognosis". FCP Medical. Retrieved 22 July 2022.

- ^ a b c d e Field-Fote 2009, p. 11.

- ^ Augustine 2011, p. 199.

- ^ Sabharwal 2013, p. 39.

- ^ Snell 2010, p. 169.

- ^ Augustine 2011, p. 200.

- ^ Schurch, Brigitte; Tawadros, Cécile; Carda, Stefano (2015), "Dysfunction of lower urinary tract in patients with spinal cord injury", Neurology of Sexual and Bladder Disorders, Handbook of Clinical Neurology, vol. 130, Elsevier, pp. 247–267, doi:10.1016/b978-0-444-63247-0.00014-6, ISBN 9780444632470, PMID 26003248

- ^ Sabharwal 2014, p. 843.

- ^ Sabharwal 2013, pp. 53–54.

- ^ a b Weiss 2010, p. 313.

- ^ Weiss 2010, pp. 311, 313.

- ^ Weiss 2010, p. 311.

- ^ a b c Dimitriadis F, Karakitsios K, Tsounapi P, Tsambalas S, Loutradis D, Kanakas N, Watanabe NT, Saito M, Miyagawa I, Sofikitis N (June 2010). "Erectile function and male reproduction in men with spinal cord injury: a review". Andrologia. 42 (3): 139–65. doi:10.1111/j.1439-0272.2009.00969.x. PMID 20500744. S2CID 10504.

- ^ a b Holtz & Levi 2010, p. 63.

- ^ a b c Holtz & Levi 2010, p. 70.

- ^ Weiss 2010, p. 314–15.

- ^ Field-Fote 2009, p. 17.

- ^ a b Hess MJ, Hough S (July 2012). "Impact of spinal cord injury on sexuality: broad-based clinical practice intervention and practical application". The Journal of Spinal Cord Medicine. 35 (4): 211–8. doi:10.1179/2045772312Y.0000000025. PMC 3425877. PMID 22925747.

- ^ a b Selzer, M.E. (January 2010). Spinal Cord Injury. ReadHowYouWant.com. pp. 23–24. ISBN 978-1-4587-6331-0. Archived from the original on 2014-07-07.

- ^ Weiss 2010, p. 315.

- ^ Frontera, Silver & Rizzo 2014, p. 407.

- ^ Qin W, Bauman WA, Cardozo C (November 2010). "Bone and muscle loss after spinal cord injury: organ interactions". Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 1211 (1): 66–84. Bibcode:2010NYASA1211...66Q. doi:10.1111/j.1749-6632.2010.05806.x. PMID 21062296. S2CID 1143205.

- ^ a b Field-Fote 2009, p. 16.

- ^ a b Field-Fote 2009, p. 15.

- ^ Fehlings MG, Cadotte DW, Fehlings LN (August 2011). "A series of systematic reviews on the treatment of acute spinal cord injury: a foundation for best medical practice". Journal of Neurotrauma. 28 (8): 1329–33. doi:10.1089/neu.2011.1955. PMC 3143392. PMID 21651382.

- ^ Sabharwal 2013, p. 26.

- ^ Field-Fote 2009, p. 13.

- ^ a b c Holtz & Levi 2010, p. 69.

- ^ Burns SM, Mahalik JR, Hough S, Greenwell AN (2008). "Adjustment to changes in sexual functioning following spinal cord injury: The contribution of men's adherence to scripts for sexual potency". Sexuality and Disability. 26 (4): 197–205. doi:10.1007/s11195-008-9091-y. ISSN 0146-1044. S2CID 145246983.

- ^ Sabharwal 2013, p. 27.

- ^ a b Pollard C, Kennedy P (September 2007). "A longitudinal analysis of emotional impact, coping strategies and post-traumatic psychological growth following spinal cord injury: a 10-year review". British Journal of Health Psychology. 12 (Pt 3): 347–62. doi:10.1348/135910707X197046. PMID 17640451.

- ^ Lu, Yubao; Shang, Zhizhong; Zhang, Wei; Pang, Mao; Hu, Xuchang; Dai, Yu; Shen, Ruoqi; Wu, Yingjie; Liu, Chenrui; Luo, Ting; Wang, Xin; Liu, Bin; Zhang, Liangming; Rong, Limin (2024). "Global incidence and characteristics of spinal cord injury since 2000–2021: a systematic review and meta-analysis". BMC Medicine. 22 (1). BioMed Central: 285. doi:10.1186/s12916-024-03514-9. PMC 11229207. PMID 38972971.

- ^ Augustine 2011, p. 198.

- ^ Clark West, Stefan Roosendaal, Joost Bot and Frank Smithuis. "Spine injury – TLICS Classification". Radiology Assistant. Archived from the original on 2017-10-27. Retrieved 2017-10-26.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Kuchner EF, Anand AK, Kaufman BM (April 1985). "Cervical diastematomyelia: a case report with operative management". Neurosurgery. 16 (4): 538–42. doi:10.1097/00006123-198504000-00016. PMID 3990933.

- ^ Sabharwal 2013, pp. 24–25.

- ^ a b Bashir 2017, p. 48.

- ^ a b c Holtz & Levi 2010, p. 10.

- ^ Sabharwal 2013, p. 34.

- ^ Brown et al. 2008, p. 1132.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Kabu S, Gao Y, Kwon BK, Labhasetwar V (December 2015). "Drug delivery, cell-based therapies, and tissue engineering approaches for spinal cord injury". Journal of Controlled Release. 219: 141–154. doi:10.1016/j.jconrel.2015.08.060. PMC 4656085. PMID 26343846.

- ^ Frontera, Silver & Rizzo 2014, p. 39.

- ^ Celani MG, Spizzichino L, Ricci S, Zampolini M, Franceschini M (May 2001). "Spinal cord injury in Italy: A multicenter retrospective study". Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation. 82 (5): 589–96. doi:10.1053/apmr.2001.21948. PMID 11346833.

- ^ New PW, Cripps RA, Bonne Lee B (February 2014). "Global maps of non-traumatic spinal cord injury epidemiology: towards a living data repository". Spinal Cord. 52 (2): 97–109. doi:10.1038/sc.2012.165. PMID 23318556.

- ^ Sabharwal 2013, p. 24.

- ^ van den Berg ME, Castellote JM, de Pedro-Cuesta J, Mahillo-Fernandez I (August 2010). "Survival after spinal cord injury: a systematic review". Journal of Neurotrauma. 27 (8): 1517–28. doi:10.1089/neu.2009.1138. PMID 20486810.

- ^ a b c Fulk, Behrman & Schmitz 2013, p. 890.

- ^ Moore 2006, pp. 530–31.

- ^ a b c Sabharwal 2013, p. 31.

- ^ a b Sabharwal 2013, p. 32.

- ^ Sabharwal 2013, p. 33.

- ^ a b c d Wyatt et al. 2012, p. 384.

- ^ "How is SCI diagnosed?". National Institute of Child Health and Human Development. 2016. Retrieved 2019-01-01.

- ^ Holtz & Levi 2010, p. 78.

- ^ DeKoning 2014, p. 389.

- ^ Holtz & Levi 2010, pp. 64–65.

- ^ a b Sabharwal 2013, p. 55.

- ^ a b Sabharwal 2013, p. 38.

- ^ Augustine 2011, p. 207.

- ^ a b Cameron et al. 2014.

- ^ a b Sabharwal 2013, p. 37.

- ^ "EMS spinal precautions and the use of the long backboard". Prehospital Emergency Care. 17 (3): 392–3. 2013. doi:10.3109/10903127.2013.773115. PMID 23458580.

- ^ a b Ahn H, Singh J, Nathens A, MacDonald RD, Travers A, Tallon J, Fehlings MG, Yee A (August 2011). "Pre-hospital care management of a potential spinal cord injured patient: a systematic review of the literature and evidence-based guidelines". Journal of Neurotrauma. 28 (8): 1341–61. doi:10.1089/neu.2009.1168. PMC 3143405. PMID 20175667.

- ^ a b Sabharwal 2013, p. 53.

- ^ a b Bigelow & Medzon 2011, p. 173.

- ^ DeKoning 2014, p. 373.

- ^ a b Campbell J (2018). International Trauma Life Support for Emergency Care Providers (8th Global ed.). Pearson. pp. 221–248. ISBN 9781292170848.

- ^ a b Holtz & Levi 2010, pp. 63–64.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Witiw CD, Fehlings MG (July 2015). "Acute Spinal Cord Injury". Journal of Spinal Disorders & Techniques. 28 (6): 202–10. doi:10.1097/BSD.0000000000000287. PMID 26098670. S2CID 8087959.

- ^ Yue, J. K.; Hemmerle, D. D.; Winkler, E. A.; Thomas, L. H.; Fernandez, X. D.; Kyritsis, N.; Pan, J. Z.; Pascual, L. U.; Singh, V.; Weinstein, P. R.; Talbott, J. F.; Huie, J. R.; Ferguson, A. R.; Whetstone, W. D.; Manley, G. T.; Beattie, M. S.; Bresnahan, J. C.; Mummaneni, P. V.; Dhall, S. S. (2020). "Clinical Implementation of Novel Spinal Cord Perfusion Pressure Protocol in Acute Traumatic Spinal Cord Injury at U.S. Level I Trauma Center: TRACK-SCI Study". World Neurosurgery. 133: e391 – e396. doi:10.1016/j.wneu.2019.09.044. PMID 31526882. S2CID 202671826.

- ^ Bigelow & Medzon 2011, pp. 167, 176.

- ^ a b Rouanet C, Reges D, Rocha E, Gagliardi V, Silva GS (June 2017). "Traumatic spinal cord injury: current concepts and treatment update". Arquivos de Neuro-Psiquiatria. 75 (6): 387–393. doi:10.1590/0004-282X20170048. PMID 28658409.

- ^ Holtz & Levi 2010, p. 65.

- ^ Burke, J. F.; Yue, J. K.; Ngwenya, L. B.; Winkler, E. A.; Talbott, J. F.; Pan, J. Z.; Ferguson, A. R.; Beattie, M. S.; Bresnahan, J. C.; Haefeli, J.; Whetstone, W. D.; Suen, C. G.; Huang, M. C.; Manley, G. T.; Tarapore, P. E.; Dhall, S. S. (2019). "Ultra-Early (<12 Hours) Surgery Correlates with Higher Rate of American Spinal Injury Association Impairment Scale Conversion After Cervical Spinal Cord Injury". Neurosurgery. 85 (2): 199–203. doi:10.1093/neuros/nyy537. PMID 30496474.

- ^ Holtz & Levi 2010, pp. 65–69.

- ^ Balas, Michael; Guttman, Matthew P.; Badhiwala, Jetan H.; Lebovic, Gerald; Nathens, Avery B.; da Costa, Leodante; Zador, Zsolt; Spears, Julian; Fehlings, Michael G.; Wilson, Jefferson R.; Witiw, Christopher D. (2021-03-16). "Earlier Surgery Reduces Complications in Acute Traumatic Thoracolumbar Spinal Cord Injury: Analysis of a Multi-Center Cohort of 4108 Patients". Journal of Neurotrauma. 39 (3–4): 277–284. doi:10.1089/neu.2020.7525. ISSN 0897-7151. PMID 33724051. S2CID 232244800.

- ^ Balas, Michael; Prömmel, Peter; Nguyen, Laura; Jack, Andrew S.; Lebovic, Gerald; Badhiwala, Jetan H.; da Costa, Leodante; Nathens, Avery B.; Fehlings, Michael G.; Wilson, Jefferson R.; Witiw, Christopher D. (2021-11-01). "Reality of Accomplishing Surgery within 24 Hours for Complete Cervical Spinal Cord Injury: Clinical Practices and Safety". Journal of Neurotrauma. 38 (21): 3011–3019. doi:10.1089/neu.2021.0177. ISSN 0897-7151. PMID 34382411. S2CID 236990438.

- ^ Holtz & Levi 2010, p. 67.

- ^ Bigelow & Medzon 2011, p. 177.

- ^ Krag MH, Byrt W, Pope M (March 1989). "Pull-off strength of gardner-Wells tongs from cadaveric crania". Spine. 14 (3): 247–50. doi:10.1097/00007632-198903000-00001. PMID 2711238. S2CID 3183490.

- ^ "Management of acute spinal cord injuries in an intensive care unit or other monitored setting". Neurosurgery. 50 (3 Suppl): S51–7. March 2002. doi:10.1097/00006123-200203001-00011. PMID 12431287.

- ^ Fulk G; Schmitz T; Behrman A (2007). "Traumatic Spinal Cord Injury". In O'Sullivan S; Schmitz T (eds.). Physical Rehabilitation (5th ed.). Philadelphia: F.A. Davis. pp. 937–96.

- ^ a b c Reid WD, Brown JA, Konnyu KJ, Rurak JM, Sakakibara BM (2010). "Physiotherapy secretion removal techniques in people with spinal cord injury: a systematic review". The Journal of Spinal Cord Medicine. 33 (4): 353–70. doi:10.1080/10790268.2010.11689714. PMC 2964024. PMID 21061895.

- ^ a b c d e Brown R, DiMarco AF, Hoit JD, Garshick E (August 2006). "Respiratory dysfunction and management in spinal cord injury". Respiratory Care. 51 (8): 853–68, discussion 869–70. PMC 2495152. PMID 16867197. Archived from the original on 2022-02-12. Retrieved 2014-07-14.

- ^ Winslow C, Rozovsky J (October 2003). "Effect of spinal cord injury on the respiratory system". American Journal of Physical Medicine & Rehabilitation. 82 (10): 803–14. doi:10.1097/01.PHM.0000078184.08835.01. PMID 14508412.

- ^ Weiss 2010, p. 306.

- ^ a b Chumney D, Nollinger K, Shesko K, Skop K, Spencer M, Newton RA (2010). "Ability of Functional Independence Measure to accurately predict functional outcome of stroke-specific population: systematic review". Journal of Rehabilitation Research and Development. 47 (1): 17–29. doi:10.1682/JRRD.2009.08.0140. PMID 20437324.

- ^ del-Ama AJ, Koutsou AD, Moreno JC, de-los-Reyes A, Gil-Agudo A, Pons JL (2012). "Review of hybrid exoskeletons to restore gait following spinal cord injury". Journal of Rehabilitation Research and Development. 49 (4): 497–514. doi:10.1682/JRRD.2011.03.0043. PMID 22773254.

- ^ Frood RT (2011). "The use of treadmill training to recover locomotor ability in patients with spinal cord injury". Bioscience Horizons. 4: 108–117. doi:10.1093/biohorizons/hzr003.

- ^ James W. Rowland, Gregory W. J. Hawryluk. "Current status of acute spinal cord injury pathophysiology and emerging therapies: promise on the horizon". JNS Journal of Neurosurgery. 25: 2, 6.[permanent dead link]

- ^ Burns, Anthony S.; Ditunno, John F. (2001-12-15). "Establishing Prognosis and Maximizing Functional Outcomes After Spinal Cord Injury: A Review of Current and Future Directions in Rehabilitation Management". Spine. 26 (24S): 137–145. doi:10.1097/00007632-200112151-00023. ISSN 0362-2436. PMID 11805621. S2CID 30220082.

- ^ Steven C. Kirshblum, Michael M. Priebe. "Spinal Cord Injury Medicine. 3. Rehabilitation Phase After Acute Spinal Cord Injury". Spinal Cord Injury Medicine. 88.

- ^ Janda, Vladimir (2016). Manuelle Muskelfunktionsdiagnostik. U.C. Smolenski, J. Buchmann, L. Beyer. pp. 195–242. ISBN 978-3-437-46431-7.

- ^ a b Peitzman et al. 2012, p. 293.

- ^ a b c Scivoletto G, Tamburella F, Laurenza L, Torre M, Molinari M (2014). "Who is going to walk? A review of the factors influencing walking recovery after spinal cord injury". Frontiers in Human Neuroscience. 8: 141. doi:10.3389/fnhum.2014.00141. PMC 3952432. PMID 24659962.

- ^ a b Waters RL, Adkins RH, Yakura JS (November 1991). "Definition of complete spinal cord injury". Paraplegia. 29 (9): 573–81. doi:10.1038/sc.1991.85. PMID 1787981.

- ^ Field-Fote 2009, p. 8.

- ^ Yakura, J.S. (Dec 22, 1996). "Recovery following spinal cord injury". American Rehabilitation. Retrieved 5 November 2015.

- ^ Cortois & Charvier 2015, p. 236.

- ^ Elliott 2010.

- ^ Data from the National Spinal Cord Injury Statistical Center. Committee on Spinal Cord Injury; Board on Neuroscience and Behavioral Health; Institute of Medicine (27 July 2005). Spinal Cord Injury: Progress, Promise, and Priorities. National Academies Press. p. 15. ISBN 978-0-309-16520-4. Archived from the original on 6 November 2017.

- ^ Liu JM, Long XH, Zhou Y, Peng HW, Liu ZL, Huang SH (March 2016). "Is Urgent Decompression Superior to Delayed Surgery for Traumatic Spinal Cord Injury? A Meta-Analysis". World Neurosurgery. 87: 124–31. doi:10.1016/j.wneu.2015.11.098. PMID 26724625.

- ^ a b Chéhensse C, Bahrami S, Denys P, Clément P, Bernabé J, Giuliano F (2013). "The spinal control of ejaculation revisited: a systematic review and meta-analysis of anejaculation in spinal cord injured patients". Human Reproduction Update. 19 (5): 507–26. doi:10.1093/humupd/dmt029. PMID 23820516.

- ^ "Spinal Cord Injury Facts". Foundation for Spinal Cord Injury Prevention, Care & Cure. June 2009. Archived from the original on 2 November 2015. Retrieved 5 November 2015.

- ^ Qiu J (July 2009). "China Spinal Cord Injury Network: changes from within". The Lancet. Neurology. 8 (7): 606–7. doi:10.1016/S1474-4422(09)70162-0. PMID 19539234. S2CID 206158809.

- ^ a b c Singh A, Tetreault L, Kalsi-Ryan S, Nouri A, Fehlings MG (2014). "Global prevalence and incidence of traumatic spinal cord injury". Clinical Epidemiology. 6: 309–31. doi:10.2147/CLEP.S68889. PMC 4179833. PMID 25278785.

- ^ Field-Fote 2009, p. 3.

- ^ Devivo MJ (May 2012). "Epidemiology of traumatic spinal cord injury: trends and future implications". Spinal Cord. 50 (5): 365–72. doi:10.1038/sc.2011.178. PMID 22270188.

- ^ Pellock & Myer 2013, p. 124.

- ^ Hammell 2013, p. 274.

- ^ a b Sabharwal 2013, p. 388.

- ^ Schottler J, Vogel LC, Sturm P (December 2012). "Spinal cord injuries in young children: a review of children injured at 5 years of age and younger". Developmental Medicine and Child Neurology. 54 (12): 1138–43. doi:10.1111/j.1469-8749.2012.04411.x. PMID 22998495. S2CID 8040837.

- ^ Augustine 2011, p. 197.

- ^ a b Aghayan HR, Arjmand B, Yaghoubi M, Moradi-Lakeh M, Kashani H, Shokraneh F (2014). "Clinical outcome of autologous mononuclear cells transplantation for spinal cord injury: a systematic review and meta-analysis". Medical Journal of the Islamic Republic of Iran. 28: 112. PMC 4313447. PMID 25678991.

- ^ Augustine 2011, pp. 197–98.

- ^ a b c d e Lifshutz J, Colohan A (January 2004). "A brief history of therapy for traumatic spinal cord injury". Neurosurgical Focus. 16 (1): E5. doi:10.3171/foc.2004.16.1.6. PMID 15264783.

- ^ Holtz & Levi 2010, pp. 3–4.

- ^ a b c Holtz & Levi 2010, p. 5.

- ^ Holtz & Levi 2010, p. 6.

- ^ a b Morganti-Kossmann, Raghupathi & Maas 2012, p. 229.

- ^ Fallah, Dance & Burns 2012, p. 235.

- ^ Tremblay, Mary (1995). "The Canadian Revolution in the Management of Spinal Cord Injury". Canadian Bulletin of Medical History. 12 (1): 125–155. doi:10.3138/cbmh.12.1.125. PMID 11609092.

- ^ Sekhon LH, Fehlings MG (December 2001). "Epidemiology, demographics, and pathophysiology of acute spinal cord injury". Spine. 26 (24 Suppl): S2–12. doi:10.1097/00007632-200112151-00002. PMID 11805601.

- ^ Sabharwal 2013, p. 35.

- ^ Holtz & Levi 2010, p. 7.

- ^ "Revealed: Patients stranded in hospital for months as officials 'squabble' over equipment". Health Service Journal. 12 January 2018. Retrieved 15 February 2018.

- ^ Silva NA, Sousa N, Reis RL, Salgado AJ (March 2014). "From basics to clinical: a comprehensive review on spinal cord injury". Progress in Neurobiology. 114: 25–57. doi:10.1016/j.pneurobio.2013.11.002. PMID 24269804. S2CID 23121381.

- ^ Wirth, Edward (September 14, 2016). "Initial Clinical Trials of hESC-Derived Oligodendrocyte Progenitor Cells in Subacute Spinal Cord Injury" (PDF). ISCoS Meeting presentation. Asterias Biotherapeutics. Archived (PDF) from the original on September 21, 2016. Retrieved September 14, 2016.

- ^ "Asterias Biotherapeutics Announces Positive Efficacy Data in Patients with Complete Cervical Spinal Cord Injuries Treated with AST-OPC1". asteriasbiotherapeutics.com. Archived from the original on 2016-09-20. Retrieved 2016-09-15.

- ^ a b c Louie DR, Eng JJ, Lam T (October 2015). "Gait speed using powered robotic exoskeletons after spinal cord injury: a systematic review and correlational study". Journal of Neuroengineering and Rehabilitation. 12: 82. doi:10.1186/s12984-015-0074-9. PMC 4604762. PMID 26463355.

- ^ Young W (2015). "Electrical stimulation and motor recovery". Cell Transplantation. 24 (3): 429–46. doi:10.3727/096368915X686904. PMID 25646771.

- ^ "Paralysed man with severed spine walks thanks to implant". BBC News. 2022-02-07. Retrieved 2022-02-11.

- ^ Rowald, Andreas; Komi, Salif; Demesmaeker, Robin; Baaklini, Edeny; Hernandez-Charpak, Sergio Daniel; Paoles, Edoardo; Montanaro, Hazael; Cassara, Antonino; Becce, Fabio; Lloyd, Bryn; Newton, Taylor (2022-02-07). "Activity-dependent spinal cord neuromodulation rapidly restores trunk and leg motor functions after complete paralysis". Nature Medicine. 28 (2): 260–271. doi:10.1038/s41591-021-01663-5. ISSN 1546-170X. PMID 35132264. S2CID 246651655.SharedIt

- ^ "Paralysed man Darek Fidyka walks again after pioneering surgery". TheGuardian.com. 20 October 2014.

- ^ Whang, Oliver (24 May 2023). "Brain Implants Allow Paralyzed Man to Walk Using His Thoughts". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 2023-07-26.

- ^ Mallapaty, Smriti (2025-03-24). "Paralysed man stands again after receiving 'reprogrammed' stem cells". Nature. 640 (8057): 18–19. Bibcode:2025Natur.640...18M. doi:10.1038/d41586-025-00863-0. ISSN 1476-4687. PMID 40128427.

Bibliography

[edit]- Adams JG (5 September 2012). Emergency Medicine: Clinical Essentials. Elsevier Health Sciences. ISBN 978-1-4557-3394-1.

- Augustine JJ (21 November 2011). "Spinal trauma". In Campbell JR (ed.). International Trauma Life Support for Emergency Care Providers. Pearson Education. ISBN 978-0-13-300408-3.

- Bashir F, Malik AU, Abaidullah S (21 November 2017). "Epidemiology of Spinal Injuries, Geographical – Variations – Preventable Measures". Annals KEMU. 6 (1).

- Bigelow S, Medzon R (16 June 2011). "Injuries of the spine: Nerve". In Legome E, Shockley LW (eds.). Trauma: A Comprehensive Emergency Medicine Approach. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-139-50072-2.