Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Nerve

View on Wikipedia| Nerve | |

|---|---|

Cross-section of a nerve | |

| Details | |

| System | Nervous system |

| Identifiers | |

| Latin | nervus |

| TA98 | A14.2.00.013 |

| TA2 | 6154 |

| FMA | 65132 |

| Anatomical terms of neuroanatomy | |

A nerve is an enclosed, cable-like bundle of nerve fibers (called axons). Nerves have historically been considered the basic units of the peripheral nervous system. A nerve provides a common pathway for the electrochemical nerve impulses called action potentials that are transmitted along each of the axons to peripheral organs or, in the case of sensory nerves, from the periphery back to the central nervous system. Each axon is an extension of an individual neuron, along with other supportive cells such as some Schwann cells that coat the axons in myelin.

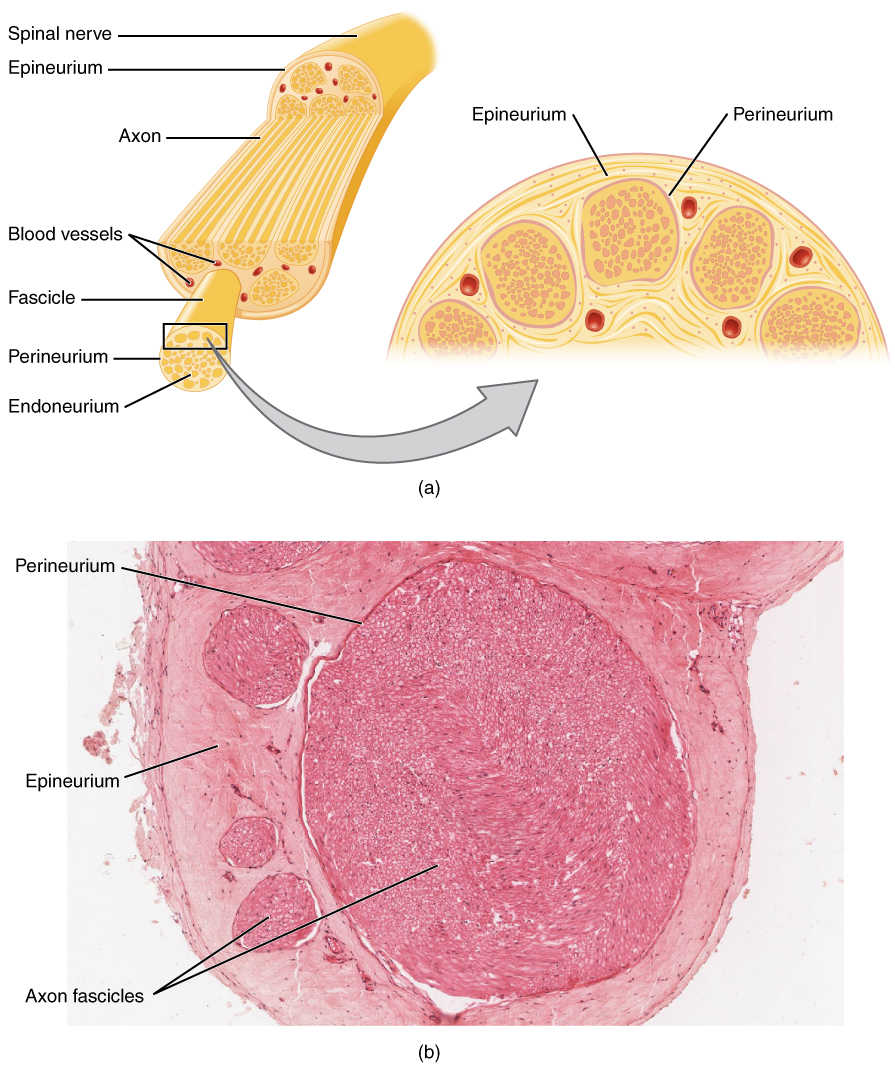

Each axon is surrounded by a layer of connective tissue called the endoneurium. The axons are bundled together into groups called fascicles, and each fascicle is wrapped in a layer of connective tissue called the perineurium. The entire nerve is wrapped in a layer of connective tissue called the epineurium. Nerve cells (often called neurons) are further classified as either sensory or motor.

In the central nervous system, the analogous structures are known as nerve tracts.[1][2]

Structure

[edit]Each nerve is covered on the outside by a dense sheath of connective tissue, the epineurium. Beneath this is a layer of fat cells, the perineurium, which forms a complete sleeve around a bundle of axons. Perineurial septa extend into the nerve and subdivide it into several bundles of fibres. Surrounding each such fibre is the endoneurium. This forms an unbroken tube from the surface of the spinal cord to the level where the axon synapses with its muscle fibres, or ends in sensory receptors. The endoneurium consists of an inner sleeve of material called the glycocalyx and an outer delicate meshwork of collagen fibres.[2] Nerves are bundled and often travel along with blood vessels, since the neurons of a nerve have fairly high energy requirements.

Within the endoneurium, the individual nerve fibres are surrounded by a low-protein liquid called endoneurial fluid. This acts in a similar way to the cerebrospinal fluid in the central nervous system and constitutes a blood-nerve barrier similar to the blood–brain barrier.[3] Molecules are thereby prevented from crossing the blood into the endoneurial fluid. During the development of nerve edema from nerve irritation (or injury), the amount of endoneurial fluid may increase at the site of irritation. This increase in fluid can be visualized using magnetic resonance (MR) neurography, and thus MR neurography can identify nerve irritation and/or injury.

Categories

[edit]Nerves are categorized into three groups based on the direction that signals are conducted:

- Afferent nerves conduct sensory information from sensory neurons to the central nervous system, for example from the mechanoreceptors in skin. Bundles of afferent fibers are known as sensory nerves.[1][2]

- Efferent nerves conduct signals from the central nervous system along motor neurons to their target muscles and glands. Bundles of these fibres are known as efferent nerves.

- Mixed nerves contain both afferent and efferent axons, and thus conduct both incoming sensory information and outgoing muscle commands in the same bundle. All spinal nerves are mixed nerves, and some of the cranial nerves are also mixed nerves.

Nerves can be categorized into two groups based on where they connect to the central nervous system:

- Spinal nerves innervate (distribute to/stimulate) much of the body, and connect through the vertebral column to the spinal cord and thus to the central nervous system. They are given letter-number designations according to the vertebra through which they connect to the spinal column.

- Cranial nerves innervate parts of the head, and connect directly to the brain (especially to the brainstem). They are typically assigned Roman numerals from 1 to 12, although cranial nerve zero is sometimes included. In addition, cranial nerves have descriptive names.

Terminology

[edit]Specific terms are used to describe nerves and their actions. A nerve that supplies information to the brain from an area of the body, or controls an action of the body is said to innervate that section of the body or organ. Other terms relate to whether the nerve affects the same side ("ipsilateral") or opposite side ("contralateral") of the body, to the part of the brain that supplies it.

Development

[edit]Nerve growth normally ends in adolescence but can be re-stimulated with a molecular mechanism known as "notch signaling".[4] If the axons of a neuron are damaged, as long as the cell body of the neuron is not damaged, the axons can regenerate and remake the synaptic connections with neurons with the help of guidepost cells. This is also referred to as neuroregeneration.[5] The nerve begins the process by destroying the nerve distal to the site of injury allowing Schwann cells, basal lamina, and the neurilemma near the injury to begin producing a regeneration tube. Nerve growth factors are produced causing many nerve sprouts to bud. When one of the growth processes finds the regeneration tube, it begins to grow rapidly towards its original destination guided the entire time by the regeneration tube. Nerve regeneration is very slow and can take up to several months to complete. While this process does repair some nerves, there will still be some functional deficit as the repairs are not perfect.[6]

Function

[edit]A nerve conveys information in the form of electrochemical impulses (as nerve impulses known as action potentials) carried by the individual neurons that make up the nerve. These impulses are extremely fast, with some myelinated neurons conducting at speeds up to 120 m/s. The impulses travel from one neuron to another by crossing a synapse, where the message is converted from electrical to chemical and then back to electrical.[2][1]

Nervous system

[edit]The nervous system is the part of an animal that coordinates its actions by transmitting signals to and from different parts of its body.[7] In vertebrates it consists of two main parts, the central nervous system (CNS) and the peripheral nervous system (PNS). The CNS consists of the brain and spinal cord. The PNS consists mainly of nerves, which are enclosed bundles of the long fibers or axons, that connect the CNS to all remaining body parts. Nerves that exit from the cranium are called cranial nerves while those exiting from the spinal cord are called spinal nerves.

Clinical significance

[edit]

Neurologists usually diagnose disorders of nerves by a physical examination, including the testing of reflexes, walking and other directed movements, muscle weakness, proprioception, and the sense of touch. This initial exam can be followed with tests such as nerve conduction study, electromyography (EMG), and computed tomography (CT).[8]

Nerves can be damaged by physical injury as well as conditions like carpal tunnel syndrome (CTS) and repetitive strain injury. Autoimmune diseases such as Guillain–Barré syndrome, neurodegenerative diseases, polyneuropathy, infection, neuritis, diabetes, or failure of the blood vessels surrounding the nerve all cause nerve damage, which can vary in severity. A pinched nerve occurs when pressure is placed on a nerve, usually from swelling due to an injury, or pregnancy and can result in pain, weakness, numbness or paralysis, an example being CTS. Symptoms can be felt in areas far from the actual site of damage, a phenomenon called referred pain. Referred pain can happen when the damage causes altered signalling to other areas.

Cancer can spread by invading the spaces around nerves. This is particularly common in head and neck cancer, prostate cancer and colorectal cancer. Multiple sclerosis is a disease associated with extensive nerve damage. It occurs when the macrophages of an individual's own immune system damage the myelin sheaths that insulate the axon of the nerve.

Other animals

[edit]This section may need to be rewritten to comply with Wikipedia's quality standards, as "neuron" does not coincide with "nerve". (April 2025) |

A neuron is called identified if it has properties that distinguish it from every other neuron in the same animal—properties such as location, neurotransmitter, gene expression pattern, and connectivity—and if every individual organism belonging to the same species has exactly one neuron with the same set of properties.[9] In vertebrate nervous systems, very few neurons are "identified" in this sense. Researchers believe humans have none—but in simpler nervous systems, some or all neurons may be thus unique.[10]

In vertebrates, the best known identified neurons are the gigantic Mauthner cells of fish.[11]: 38–44 Every fish has two Mauthner cells, located in the bottom part of the brainstem, one on the left side and one on the right. Each Mauthner cell has an axon that crosses over, innervating (stimulating) neurons at the same brain level and then travelling down through the spinal cord, making numerous connections as it goes. The synapses generated by a Mauthner cell are so powerful that a single action potential gives rise to a major behavioral response: within milliseconds the fish curves its body into a C-shape, then straightens, thereby propelling itself rapidly forward. Functionally of this is a fast escape response, triggered most easily by a strong sound wave or pressure wave impinging on the lateral line organ of the fish. Mauthner cells are not the only identified neurons in fish—there are about 20 more types, including pairs of "Mauthner cell analogs" in each spinal segmental nucleus. Although a Mauthner cell is capable of bringing about an escape response all by itself, in the context of ordinary behavior other types of cells usually contribute to shaping the amplitude and direction of the response.

Mauthner cells have been described as command neurons. A command neuron is a special type of identified neuron, defined as a neuron that is capable of driving a specific behavior all by itself.[11]: 112 Such neurons appear most commonly in the fast escape systems of various species—the squid giant axon and squid giant synapse, used for pioneering experiments in neurophysiology because of their enormous size, both participate in the fast escape circuit of the squid. The concept of a command neuron has, however, become controversial, because of studies showing that some neurons that initially appeared to fit the description were really only capable of evoking a response in a limited set of circumstances.[12]

In organisms of radial symmetry, nerve nets serve for the nervous system. There is no brain or centralised head region, and instead there are interconnected neurons spread out in nerve nets. These are found in Cnidaria, Ctenophora and Echinodermata.

History

[edit]Herophilos (335–280 BC) described the functions of the optic nerve in sight and the oculomotor nerve in eye movement. Analysis of the nerves in the cranium enabled him to differentiate between blood vessels and nerves (Ancient Greek: νεῦρον (neûron) "string, plant fiber, nerve").

Modern research has not confirmed William Cullen's 1785 hypothesis associating mental states with physical nerves,[13] although popular or lay medicine may still invoke "nerves" in diagnosing or blaming any sort of psychological worry or hesitancy, as in the common traditional phrases "my poor nerves",[14] "high-strung", and "nervous breakdown".[15]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b c Purves, Dale; Augustine, George J.; Fitzpatrick, David; Hall, William C.; LaMantia, Anthony-Samuel; McNamara, James O.; White, Leonard E. (2008). Neuroscience (4 ed.). Sinauer Associates. pp. 11–20. ISBN 978-0-87893-697-7.

- ^ a b c d Marieb EN, Hoehn K (2007). Human Anatomy & Physiology (7th ed.). Pearson. pp. 388–602. ISBN 978-0-8053-5909-1.

- ^ Kanda, T (Feb 2013). "Biology of the blood-nerve barrier and its alteration in immune mediated neuropathies". Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery & Psychiatry. 84 (2): 208–212. doi:10.1136/jnnp-2012-302312. PMID 23243216. S2CID 207005110.

- ^ Yale Study Shows Way To Re-Stimulate Brain Cell Growth ScienceDaily Archived 2017-07-07 at the Wayback Machine (Oct. 22, 1999) — Results Could Boost Understanding Of Alzheimer's, Other Brain Disorders

- ^ Kunik, D (2011). "Laser-based single-axon transection for high-content axon injury and regeneration studies". PLOS ONE. 6 (11) e26832. Bibcode:2011PLoSO...626832K. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0026832. PMC 3206876. PMID 22073205.

- ^ Burnett, Mark; Zager, Eric. "Pathophysiology of Peripheral Nerve Injury: A Brief Review: Nerve Regeneration". Medscape Article. Medscape. Archived from the original on 2011-10-31. Retrieved 2011-10-26.

- ^ Tortora, G.J., Derrickson, B. (2016). Principles of Anatomy and Physiology (15th edition). J. Wiley. ISBN 978-1-119-34373-8.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Weinberg. Normal computed tomography of the brain. p. 109.[full citation needed]

- ^ Hoyle G, Wiersma CA (1977). Identified neurons and behavior of arthropods. Plenum Press. ISBN 978-0-306-31001-0.

- ^ "Wormbook: Specification of the nervous system". Archived from the original on 2011-07-17.

- ^ a b Stein, PSG (1999). Neurons, Networks, and Motor Behavior. MIT Press. ISBN 978-0-262-69227-4.

- ^ Simmons PJ, Young D (1999). Nerve Cells and Animal Behaviour. Cambridge University Press. p. 43. ISBN 978-0-521-62726-9.

- ^

Pickering, Neil (2006). The Metaphor of Mental Illness. International perspectives in philosophy and psychiatry. Oxford University Press. p. 99. ISBN 978-0-19-853087-9. Retrieved 27 May 2023.

[...] William Cullen [...] as early as 1785 [...] postulated that certain mental disorders were the result of some unknown physical change in the nerves, for which he coined the term neurosis. This term has since quite altered its meaning, as it now refers not to a state of the nerves but to a nervous state.

- ^

For example:

Austen, Jane (2010) [1813]. Spacks, Patricia Meyer (ed.). Pride and Prejudice: An Annotated Edition. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press. p. 32. ISBN 978-0-674-04916-1. Retrieved 27 May 2023.

'Mr. Bennet, how can you abuse your own children in such a way? You take delight in vexing me. You have no compassion on my poor nerves.' [...] 'You mistake me, my dear. I have a high respect for your nerves. They are my old friends. I have heard you mention them with consideration these twenty years at least.'

- ^

Pickering, Neil (2006). The Metaphor of Mental Illness. International perspectives in philosophy and psychiatry. Oxford University Press. p. 1. ISBN 978-0-19-853087-9. Retrieved 27 May 2023.

[...] in everyday English we find [...] lay terms such as 'nervous breakdown' that relate to mental illness as a whole [...]

Further reading

[edit]- Nervous system William E. Skaggs, Scholarpedia

- Bear, M. F.; B. W. Connors; M. A. Paradiso (2006). Neuroscience: Exploring the Brain (3rd ed.). Philadelphia: Lippincott. ISBN 0-7817-6003-8.

- Binder, Marc D.; Hirokawa, Nobutaka; Windhorst, Uwe, eds. (2009). Encyclopedia of Neuroscience. Springer. ISBN 978-3-540-23735-8.

- Kandel, ER; Schwartz JH; Jessell TM (2012). Principles of Neural Science (5th ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill. ISBN 978-0-8385-7701-1.

- Squire, L. et al. (2012). Fundamental Neuroscience, 4th edition. Academic Press; ISBN 0-12-660303-0

- Andreasen, Nancy C. (March 4, 2004). Brave New Brain: Conquering Mental Illness in the Era of the Genome. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-514509-0.

- Damasio, A. R. (1994). Descartes' Error: Emotion, Reason, and the Human Brain. New York, Avon Books. ISBN 0-399-13894-3 (Hardcover) ISBN 0-380-72647-5 (Paperback)

- Gardner, H. (1976). The Shattered Mind: The Person After Brain Damage. New York, Vintage Books, 1976 ISBN 0-394-71946-8

- Goldstein, K. (2000). The Organism. New York, Zone Books. ISBN 0-942299-96-5 (Hardcover) ISBN 0-942299-97-3 (Paperback)

- Lauwereyns, Jan (February 2010). The Anatomy of Bias: How Neural Circuits Weigh the Options. Cambridge, Massachusetts: The MIT Press. ISBN 978-0-262-12310-5.

External links

[edit]- List of nerves

The Nervous System at Wikibooks (human)

The Nervous System at Wikibooks (human) Nervous System at Wikibooks (non-human)

Nervous System at Wikibooks (non-human)- Parsons, Frederick Gymer (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 19 (11th ed.). pp. 394–400.