Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Epithelium

View on Wikipedia

| Epithelium | |

|---|---|

Types of epithelium | |

| Identifiers | |

| MeSH | D004848 |

| TH | H2.00.02.0.00002 |

| FMA | 9639 |

| Anatomical terms of microanatomy | |

| This article is part of a series on |

| Epithelia |

|---|

| Squamous epithelial cell |

| Columnar epithelial cell |

| Cuboidal epithelial cell |

| Specialised epithelia |

|

| Other |

Epithelium or epithelial tissue is a thin, continuous, protective layer of cells with little extracellular matrix. An example is the epidermis, the outermost layer of the skin. Epithelial (mesothelial) tissues line the outer surfaces of many internal organs, the corresponding inner surfaces of body cavities, and the inner surfaces of blood vessels. Epithelial tissue is one of the four basic types of animal tissue, along with connective tissue, muscle tissue and nervous tissue. These tissues also lack blood or lymph supply. The tissue is supplied by nerves.

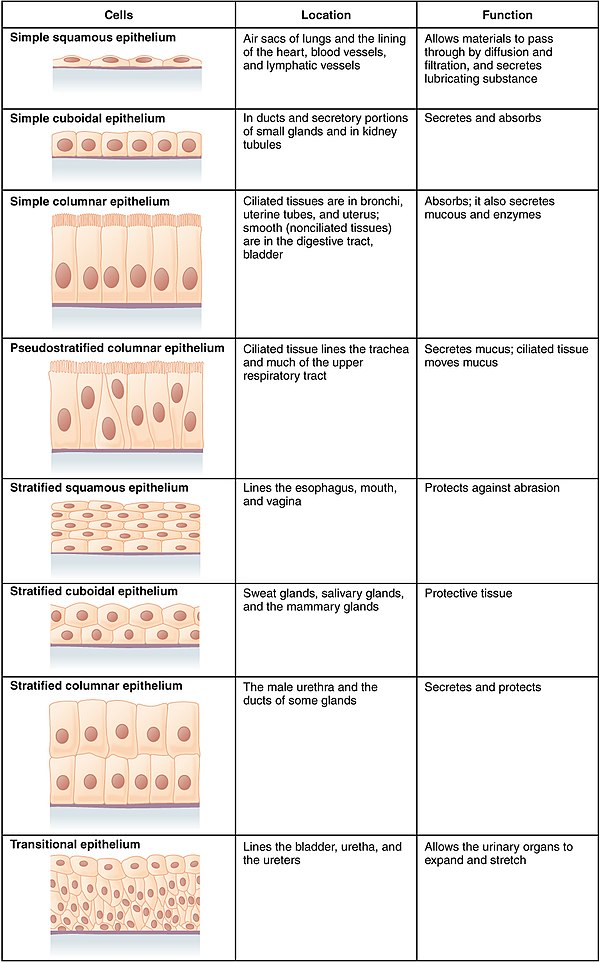

There are three principal shapes of epithelial cell: squamous (scaly), columnar, and cuboidal.[1] These can be arranged in a singular layer of cells as simple epithelium, either simple squamous, simple columnar, or simple cuboidal, or in layers of two or more cells deep as stratified (layered), or compound, either squamous, columnar or cuboidal. In some tissues, a layer of columnar cells may appear to be stratified due to the placement of the nuclei. This sort of tissue is called pseudostratified. All glands are made up of epithelial cells. Functions of epithelial cells include diffusion, filtration, secretion, selective absorption, germination, and transcellular transport. Compound epithelium has protective functions.

Epithelial layers contain no blood vessels (avascular), so they must receive nourishment via diffusion of substances from the underlying connective tissue, through the basement membrane.[2][3]: 3 Cell junctions are especially abundant in epithelial tissues.

Classification

[edit]Simple epithelium

[edit]Simple epithelium is a single layer of cells with every cell in direct contact with the basement membrane that separates it from the underlying connective tissue. In general, it is found where absorption and filtration occur. The thinness of the epithelial barrier facilitates these processes.[4]

In general, epithelial tissues are classified by the number of their layers and by the shape and function of the cells.[2][4][5] The basic cell types are squamous, cuboidal, and columnar, classed by their shape.

| Type | Description |

|---|---|

| Squamous | Squamous cells have the appearance of thin, flat plates that can look polygonal when viewed from above.[6] Their name comes from squāma, Latin for "scale" – as on fish or snake skin. The cells fit closely together in tissues, providing a smooth, low-friction surface over which fluids can move easily. The shape of the nucleus usually corresponds to the cell form and helps to identify the type of epithelium. Squamous cells tend to have horizontally flattened, nearly oval-shaped nuclei because of the thin, flattened form of the cell. Squamous epithelium is found lining surfaces such as skin or alveoli in the lung, enabling simple passive diffusion as also found in the alveolar epithelium in the lungs. Specialized squamous epithelium also forms the lining of cavities such as in blood vessels (as endothelium), in the pericardium (as mesothelium), and in other body cavities. |

| Cuboidal | Cuboidal epithelial cells have a cube-like shape and appear square in cross-section. The cell nucleus is large, spherical and is in the center of the cell. Cuboidal epithelium is commonly found in secretive tissue such as the exocrine glands, or in absorptive tissue such as the pancreas, the lining of the kidney tubules as well as in the ducts of the glands. The germinal epithelium that covers the female ovary, and the germinal epithelium that lines the walls of the seminferous tubules in the testes are also of the cuboidal type. Cuboidal cells provide protection and may be active in pumping material in or out of the lumen, or passive depending on their location and specialisation. Simple cuboidal epithelium commonly differentiates to form the secretory and duct portions of glands.[7] Stratified cuboidal epithelium protects areas such as the ducts of sweat glands,[8] mammary glands, and salivary glands. |

| Columnar | Columnar epithelial cells are elongated and column-shaped and have a height of at least four times their width. Their nuclei are elongated and are usually located near the base of the cells. Columnar epithelium forms the lining of the stomach and intestines. The cells here may possess microvilli for maximizing the surface area for absorption, and these microvilli may form a brush border. Other cells may be ciliated to move mucus in the function of mucociliary clearance. Other ciliated cells are found in the fallopian tubes, the uterus and central canal of the spinal cord. Some columnar cells are specialized for sensory reception such as in the nose, ears and the taste buds. Hair cells in the inner ears have stereocilia which are similar to microvilli. Goblet cells are modified columnar cells and are found between the columnar epithelial cells of the duodenum. They secrete mucus, which acts as a lubricant. Single-layered non-ciliated columnar epithelium tends to indicate an absorptive function. Stratified columnar epithelium is rare but is found in lobar ducts in the salivary glands, the eye, the pharynx, and sex organs. This consists of a layer of cells resting on at least one other layer of epithelial cells, which can be squamous, cuboidal, or columnar. |

| Pseudostratified | These are simple columnar epithelial cells whose nuclei appear at different heights, giving the misleading (hence "pseudo") impression that the epithelium is stratified when the cells are viewed in cross section. Ciliated pseudostratified epithelial cells have cilia. Cilia are capable of energy-dependent pulsatile beating in a certain direction through interaction of cytoskeletal microtubules and connecting structural proteins and enzymes. In the respiratory tract, the wafting effect produced causes mucus secreted locally by the goblet cells (to lubricate and to trap pathogens and particles) to flow in that direction (typically out of the body). Ciliated epithelium is found in the airways (nose, bronchi), but is also found in the uterus and fallopian tubes, where the cilia propel the ovum to the uterus. |

By layer, epithelium is classed as either simple epithelium, only one cell thick (unilayered), or stratified epithelium having two or more cells in thickness, or multi-layered – as stratified squamous epithelium, stratified cuboidal epithelium, and stratified columnar epithelium,[9]: 94, 97 and both types of layering can be made up of any of the cell shapes.[4] However, when taller simple columnar epithelial cells are viewed in cross section showing several nuclei appearing at different heights, they can be confused with stratified epithelia. This kind of epithelium is therefore described as pseudostratified columnar epithelium.[10]

Transitional epithelium has cells that can change from squamous to cuboidal, depending on the amount of tension on the epithelium.[11]

Stratified epithelium

[edit]Stratified or compound epithelium differs from simple epithelium in that it is multilayered. It is therefore found where body linings have to withstand mechanical or chemical insult such that layers can be abraded and lost without exposing subepithelial layers. Cells flatten as the layers become more apical, though in their most basal layers, the cells can be squamous, cuboidal, or columnar.[12]

Stratified epithelia (of columnar, cuboidal, or squamous type) can have the following specializations:[12]

| Specialization | Description |

|---|---|

| Keratinized | In this particular case, the most apical layers (exterior) of cells are dead and lose their nucleus and cytoplasm, instead contain a tough, resistant protein called keratin. This specialization makes the epithelium somewhat water-resistant, so is found in the mammalian skin. The lining of the oesophagus is an example of a non-keratinized or "moist" stratified epithelium.[12] |

| Parakeratinized | In this case, the most apical layers of cells are filled with keratin, but they still retain their nuclei. These nuclei are pyknotic, meaning that they are highly condensed. Parakeratinized epithelium is sometimes found in the oral mucosa and in the upper regions of the oesophagus.[13] |

| Transitional | Transitional epithelia are found in tissues that stretch, and it can appear to be stratified cuboidal when the tissue is relaxed, or stratified squamous when the organ is distended and the tissue stretches. It is sometimes called urothelium since it is almost exclusively found in the bladder, ureters and urethra.[12] |

Structure

[edit]Epithelial tissue cells can adopt shapes of varying complexity from polyhedral to scutoidal to punakoidal.[14] They are tightly packed and form a continuous sheet with almost no intercellular spaces. All epithelia is usually separated from underlying tissues by an extracellular fibrous basement membrane.

The lining of the mouth, lung alveoli and kidney tubules are all made of epithelial tissue. The lining of the blood and lymphatic vessels are of a specialised form of epithelium called endothelium.

Location

[edit]

Epithelium lines both the outside (skin) and the inside cavities and lumina of bodies. The outermost layer of human skin is composed of dead stratified squamous, keratinized epithelial cells.[15]

Tissues that line the inside of the mouth, the esophagus, the vagina, and part of the rectum are composed of nonkeratinized stratified squamous epithelium. Other surfaces that separate body cavities from the outside environment are lined by simple squamous, columnar, or pseudostratified epithelial cells. Other epithelial cells line the insides of the lungs, the gastrointestinal tract, the reproductive and urinary tracts, and make up the exocrine and endocrine glands. The outer surface of the cornea is covered with fast-growing, easily regenerated epithelial cells. A specialised form of epithelium, endothelium, forms the inner lining of blood vessels and the heart, and is known as vascular endothelium, and lining lymphatic vessels as lymphatic endothelium. Another type, mesothelium, forms the walls of the pericardium, pleurae, and peritoneum.[citation needed]

In arthropods, the integument, or external "skin", consists of a single layer of epithelial ectoderm from which arises the cuticle,[16] an outer covering of chitin, the rigidity of which varies as per its chemical composition.

Basement membrane

[edit]The basal surface of epithelial tissue rests on a basement membrane and the free/apical surface faces body fluid or outside. The basement membrane acts as a scaffolding on which epithelium can grow and regenerate after injuries.[17] Epithelial tissue has a nerve supply, but no blood supply and must be nourished by substances diffusing from the blood vessels in the underlying tissue. The basement membrane acts as a selectively permeable membrane that determines which substances will be able to enter the epithelium.[3]: 3

The basal lamina is made up of laminin (glycoproteins) secreted by epithelial cells. The reticular lamina beneath the basal lamina is made up of collagen proteins secreted by connective tissue.[citation needed]

Cell junctions

[edit]Cell junctions are especially abundant in epithelial tissues. They consist of protein complexes and provide contact between neighbouring cells, between a cell and the extracellular matrix, or they build up the paracellular barrier of epithelia and control the paracellular transport.[18]

Cell junctions are the contact points between plasma membrane and tissue cells. There are mainly 5 different types of cell junctions: tight junctions, adherens junctions, desmosomes, hemidesmosomes, and gap junctions.

- Tight junctions are a pair of trans-membrane protein fused on outer plasma membrane.

- Adherens junctions are a plaque (protein layer on the inside plasma membrane) which attaches both cells' microfilaments.

- Desmosomes attach to the microfilaments of cytoskeleton made up of keratin protein.

- Hemidesmosomes resemble desmosomes on a section. They are made up of the integrin (a transmembrane protein) instead of cadherin. They attach the epithelial cell to the basement membrane.

- Gap junctions connect the cytoplasm of two cells and are made up of proteins called connexins (six of which come together to make a connexion).[citation needed]

Development

[edit]Epithelial tissues are derived from all of the embryological germ layers:[citation needed]

- from ectoderm (e.g., the epidermis);

- from endoderm (e.g., the lining of the gastrointestinal tract);

- from mesoderm (e.g., the inner linings of body cavities).

However, pathologists do not consider endothelium and mesothelium (both derived from mesoderm) to be true epithelium. This is because such tissues present very different pathology. For that reason, pathologists label cancers in endothelium and mesothelium sarcomas, whereas true epithelial cancers are called carcinomas. Additionally, the filaments that support these mesoderm-derived tissues are very distinct. Outside of the field of pathology, it is generally accepted that the epithelium arises from all three germ layers.[citation needed]

Cell turnover

[edit]Epithelia turn over at some of the fastest rates in the body. For epithelial layers to maintain constant cell numbers essential to their functions, the number of cells that divide must match those that die. They do this mechanically. If there are too few of the cells, the stretch that they experience rapidly activates cell division.[19] Alternatively, when too many cells accumulate, crowding triggers their death by activation epithelial cell extrusion.[20][21] Here, cells fated for elimination are seamlessly squeezed out by contracting a band of actin and myosin around and below the cell, preventing any gaps from forming that could disrupt their barriers. Failure to do so can result in aggressive tumors and their invasion by aberrant basal cell extrusion.[22][23]

Functions

[edit]

Epithelial tissues have as their primary functions:

- to protect the tissues that lie beneath from radiation, desiccation, toxins, invasion by pathogens, and physical trauma

- the regulation and exchange of chemicals between the underlying tissues and a body cavity

- the secretion of hormones into the circulatory system, as well as the secretion of sweat, mucus, enzymes, and other products that are delivered by ducts[9]: 91

- to provide sensation[24]

- Absorb water and digested food in the lining of digestive canal.

Glandular tissue

[edit]Glandular tissue is the type of epithelium that forms the glands from the infolding of epithelium and subsequent growth in the underlying connective tissue. They may be specialized columnar or cuboidal tissues consisting of goblet cells, which secrete mucus. There are two major classifications of glands: endocrine glands and exocrine glands:

- Endocrine glands secrete their product into the extracellular space where it is rapidly taken up by the circulatory system.

- Exocrine glands secrete their products into a duct that then delivers the product to the lumen of an organ or onto the free surface of the epithelium. Their secretions include tears, saliva, oil (sebum), enzyme, digestive juices, sweat, etc.

Sensing the extracellular environment

[edit]"Some epithelial cells are ciliated, especially in respiratory epithelium, and they commonly exist as a sheet of polarised cells forming a tube or tubule with cilia projecting into the lumen." Primary cilia on epithelial cells provide chemosensation, thermoception, and mechanosensation of the extracellular environment by playing "a sensory role mediating specific signalling cues, including soluble factors in the external cell environment, a secretory role in which a soluble protein is released to have an effect downstream of the fluid flow, and mediation of fluid flow if the cilia are motile."[25]

Host immune response

[edit]Epithelial cells express many genes that encode immune mediators and proteins involved in cell-cell communication with hematopoietic immune cells.[26] The resulting immune functions of these non-hematopoietic, structural cells contribute to the mammalian immune system ("structural immunity").[27][28] Relevant aspects of the epithelial cell response to infections are encoded in the epigenome of these cells, which enables a rapid response to immunological challenges.[citation needed]

Clinical significance

[edit]

The slide shows at (1) an epithelial cell infected by Chlamydia pneumoniae; their inclusion bodies shown at (3); an uninfected cell shown at (2) and (4) showing the difference between an infected cell nucleus and an uninfected cell nucleus.

Epithelium grown in culture can be identified by examining its morphological characteristics. Epithelial cells tend to cluster together, and have a "characteristic tight pavement-like appearance". But this is not always the case, such as when the cells are derived from a tumor. In these cases, it is often necessary to use certain biochemical markers to make a positive identification. The intermediate filament proteins in the cytokeratin group are almost exclusively found in epithelial cells, so they are often used for this purpose.[3]: 9

Cancers originating from the epithelium are classified as carcinomas. In contrast, sarcomas develop in connective tissue.[29]

When epithelial cells or tissues are damaged from cystic fibrosis, sweat glands are also damaged, causing a frosty coating of the skin. [citation needed]

Etymology and pronunciation

[edit]The word epithelium uses the Greek roots ἐπί (epi), "on" or "upon", and θηλή (thēlē), "nipple". Epithelium is so called because the name was originally used to describe the translucent covering of small "nipples" of tissue on the lip.[30][31] The word has both mass and count senses; the plural form is epithelia.[citation needed]

Additional images

[edit]-

Squamous epithelium 100×

-

Human cheek cells (nonkeratinized stratified squamous epithelium) 500×

-

Histology of female urethra showing transitional epithelium

-

Histology of sweat gland showing stratified cuboidal epithelium

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Kurn, Heidi; Daly, Daniel T. (2025), "Histology, Epithelial Cell", StatPearls, Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing, PMID 32644489, retrieved 17 March 2025

- ^ a b Eurell JA, Frappier BL, eds. (2006). Dellmann's Textbook of Veterinary Histology. Wiley-Blackwell. p. 18. ISBN 978-0-7817-4148-4.

- ^ a b c Freshney RI (2002). "Introduction". In Freshney RI, Freshney M (eds.). Culture of epithelial cells. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-0-471-40121-6.

- ^ a b c Marieb EM (1995). Human Anatomy and Physiology (3rd ed.). Benjamin/Cummings. pp. 103–104. ISBN 0-8053-4281-8.

- ^ Platzer W (2008). Color atlas of human anatomy: Locomotor system. Thieme. p. 8. ISBN 978-3-13-533306-9.

- ^ Kühnel W (2003). Color atlas of cytology, histology, and microscopic anatomy. Thieme. p. 102. ISBN 978-3-13-562404-4.

- ^ Pratt R. "Simple Cuboidal Epithelium". AnatomyOne. Amirsys, Inc. Retrieved 28 September 2012.

- ^ Eroschenko VP (2008). "Integumentary System". DiFiore's Atlas of Histology with Functional Correlations. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. pp. 212–234. ISBN 978-0-7817-7057-6.

- ^ a b van Lommel AT (2002). From cells to organs: a histology textbook and atlas. Springer. ISBN 978-1-4020-7257-4.

- ^ Melfi RC, Alley KE, eds. (2000). Permar's oral embryology and microscopic anatomy: a textbook for students in dental hygiene. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. p. 9. ISBN 978-0-683-30644-6.

- ^ Pratt R. "Epithelial Cells". AnatomyOne. Amirsys, Inc. Archived from the original on 19 December 2012. Retrieved 28 September 2012.

- ^ a b c d Jenkins GW, Tortora GJ (2013). Anatomy and Physiology from Science to Life (3rd ed.). John Wiley & Sons. pp. 110–115. ISBN 978-1-118-12920-3.

- ^ Ross MH, Pawlina W (2015). Histology: A Text and Atlas: With Correlated Cell and Molecular Biology (7th ed.). Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. pp. 528, 604. ISBN 978-1-4511-8742-7.

- ^ Iber, Dagmar; Vetter, Roman (12 May 2022). "3D Organisation of Cells in Pseudostratified Epithelia". Frontiers in Physics. 10. Bibcode:2022FrP....10.8160I. doi:10.3389/fphy.2022.898160. hdl:20.500.11850/547113.

- ^ Marieb E (2011). Anatomy & Physiology. Boston: Benjamin Cummings. p. 133. ISBN 978-0-321-61640-1.

- ^ Kristensen NP, Georges C (1 December 2003). "Integument". Lepidoptera, Moths and Butterflies: Morphology, Physiology, and Development: Teilband. Walter de Gruyter. p. 484. ISBN 978-3-11-016210-3. Retrieved 10 January 2013.

- ^ McConnell TH (2006). The nature of disease: pathology for the health professions. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. p. 55. ISBN 978-0-7817-5317-3.

- ^ Alberts B (2002). Molecular biology of the cell (4th ed.). New York [u.a.]: Garland. p. 1067. ISBN 0-8153-4072-9.

- ^ Gudipaty SA, Lindblom J, Loftus PD, Redd MJ, Edes K, Davey CF, et al. (March 2017). "Mechanical stretch triggers rapid epithelial cell division through Piezo1". Nature. 543 (7643): 118–121. Bibcode:2017Natur.543..118G. doi:10.1038/nature21407. PMC 5334365. PMID 28199303.

- ^ Rosenblatt J, Raff MC, Cramer LP (November 2001). "An epithelial cell destined for apoptosis signals its neighbors to extrude it by an actin- and myosin-dependent mechanism". Current Biology. 11 (23): 1847–1857. Bibcode:2001CBio...11.1847R. doi:10.1016/S0960-9822(01)00587-5. PMID 11728307. S2CID 5858676.

- ^ Eisenhoffer GT, Loftus PD, Yoshigi M, Otsuna H, Chien CB, Morcos PA, Rosenblatt J (April 2012). "Crowding induces live cell extrusion to maintain homeostatic cell numbers in epithelia". Nature. 484 (7395): 546–549. Bibcode:2012Natur.484..546E. doi:10.1038/nature10999. PMC 4593481. PMID 22504183.

- ^ Fadul J, Zulueta-Coarasa T, Slattum GM, Redd NM, Jin MF, Redd MJ, et al. (December 2021). "KRas-transformed epithelia cells invade and partially dedifferentiate by basal cell extrusion". Nature Communications. 12 (1): 7180. Bibcode:2021NatCo..12.7180F. doi:10.1038/s41467-021-27513-z. PMC 8664939. PMID 34893591.

- ^ Gu Y, Shea J, Slattum G, Firpo MA, Alexander M, Mulvihill SJ, et al. (January 2015). "Defective apical extrusion signaling contributes to aggressive tumor hallmarks". eLife. 4 e04069. doi:10.7554/eLife.04069. PMC 4337653. PMID 25621765.

- ^ Alberts B (2002). Molecular Biology of the Cell (4th ed.). New York [u.a.]: Garland. p. 1267. ISBN 0-8153-4072-9.

- ^ Adams M, Smith UM, Logan CV, Johnson CA (May 2008). "Recent advances in the molecular pathology, cell biology and genetics of ciliopathies". Journal of Medical Genetics. 45 (5): 257–267. doi:10.1136/jmg.2007.054999. PMID 18178628.

- ^ Armingol E, Officer A, Harismendy O, Lewis NE (February 2021). "Deciphering cell-cell interactions and communication from gene expression". Nature Reviews. Genetics. 22 (2): 71–88. doi:10.1038/s41576-020-00292-x. PMC 7649713. PMID 33168968.

- ^ Krausgruber T, Fortelny N, Fife-Gernedl V, Senekowitsch M, Schuster LC, Lercher A, et al. (July 2020). "Structural cells are key regulators of organ-specific immune responses". Nature. 583 (7815): 296–302. Bibcode:2020Natur.583..296K. doi:10.1038/s41586-020-2424-4. PMC 7610345. PMID 32612232. S2CID 220295181.

- ^ Minton K (September 2020). "A gene atlas of 'structural immunity'". Nature Reviews. Immunology. 20 (9): 518–519. doi:10.1038/s41577-020-0398-y. PMID 32661408. S2CID 220491226.

- ^ "Types of cancer". Cancer Research UK. 28 October 2014. Retrieved 13 October 2016.

- ^ Foster, Michael (1874). "On the Term Endothelium". Quarterly Journal of Microscopical Science. s2-14 (55): 219–223. doi:10.1242/jcs.s2-14.55.219.

- ^ Van Blerkom J, Gregory L (2004). Essential IVF: basic research and clinical applications. Boston: Kluwer Academic Publishers. p. 3. ISBN 978-1-4020-7551-3.

Further reading

[edit]- Green H (September 2008). "The birth of therapy with cultured cells". BioEssays. 30 (9): 897–903. doi:10.1002/bies.20797. PMID 18693268.

- Kefalides NA, Borel JP, eds. (2005). Basement membranes: cell and molecular biology. Gulf Professional Publishing. ISBN 978-0-12-153356-4.

- Nagpal R, Patel A, Gibson MC (March 2008). "Epithelial topology". BioEssays. 30 (3): 260–266. doi:10.1002/bies.20722. PMID 18293365.

- Yamaguchi Y, Brenner M, Hearing VJ (September 2007). "The regulation of skin pigmentation". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 282 (38): 27557–27561. doi:10.1074/jbc.R700026200. PMID 17635904.

External links

[edit]- Epithelium Photomicrographs

- Histology at KUMC epithel-epith02 Simple squamous epithelium of the glomerulus (kidney)

- Diagrams of simple squamous epithelium

- Histology at KUMC epithel-epith12 Stratified squamous epithelium of the vagina

- Histology at KUMC epithel-epith14 Stratified squamous epithelium of the skin (thin skin)

- Histology at KUMC epithel-epith15 Stratified squamous epithelium of the skin (thick skin)

- Stratified squamous epithelium of the esophagus

- Microanatomy Web Atlas

Epithelium

View on GrokipediaFundamentals

Definition

Epithelium is one of the four primary types of animal tissues, alongside connective tissue, muscle tissue, and nervous tissue, and is characterized by sheets of closely packed cells that cover external body surfaces, line internal cavities and organs, and constitute the secretory portions of glands.[3][4] Epithelial tissue is avascular, meaning it lacks blood vessels, and relies on diffusion of nutrients and oxygen from adjacent vascularized connective tissue for nourishment and waste removal.[5][6] The foundational recognition of epithelium as a distinct tissue type traces back to French anatomist Marie François Xavier Bichat, who in 1801 described it as "cellular tissue" forming coverings over organs in his work on anatomical tissues. Epithelium differs from related linings such as endothelium, a simple squamous epithelial layer derived from mesoderm that forms the inner lining of blood and lymphatic vessels, and mesothelium, another mesoderm-derived simple squamous layer that lines serosal body cavities; in contrast, general epithelium arises from all three embryonic germ layers—ectoderm, mesoderm, and endoderm.[7][8][9]General Characteristics

Epithelial tissues exhibit a distinct polarity, characterized by an apical surface that faces the lumen of a cavity or the external environment, a basal surface that adheres to the underlying basement membrane, and lateral surfaces that facilitate connections between adjacent cells. This polarized organization enables directional transport and functional specialization, with organelles distributed asymmetrically to support processes such as secretion and absorption.[10] The cells are arranged in continuous sheets with minimal extracellular matrix between them, promoting tight packing that forms a cohesive barrier. This close apposition is maintained by intercellular junctions, resulting in little to no interstitial fluid and an uninterrupted cellular layer.[10] Epithelial cells display morphological diversity in their shapes, which contributes to their varied roles across the body. Common shapes include squamous cells, which are flattened and scale-like; cuboidal cells, resembling cubes with roughly equal height and width; and columnar cells, which are taller than they are wide, often adapted for absorption or secretion. These shapes allow epithelial tissues to optimize surface area or thickness as needed for specific physiological demands, while maintaining overall sheet-like organization.[10] Epithelial tissues possess a high regenerative capacity due to rapid cell division, enabling quick replacement of damaged or lost cells to preserve tissue integrity. For instance, the epidermis of the skin renews approximately every 28-40 days through mitotic activity in the basal layer. This turnover varies by location but underscores the tissue's ability to repair wounds and maintain barriers. Additionally, epithelial tissues are avascular, lacking blood vessels within the tissue itself, and similarly devoid of intrinsic innervation; nutrients, oxygen, and sensory inputs diffuse from the underlying connective tissue stroma.[10][11]Classification

Simple Epithelium

Simple epithelium consists of a single layer of cells that all rest directly on the basement membrane, with the cells classified according to their shape as squamous, cuboidal, or columnar.[10][12] This arrangement ensures that every cell has direct access to the underlying connective tissue, promoting efficient nutrient and waste exchange.[13] Simple squamous epithelium features a single layer of thin, flattened cells resembling scales, which minimizes the barrier thickness to facilitate rapid diffusion and filtration of substances.[14] These cells are commonly found lining the alveoli of the lungs for gas exchange and forming the endothelium of blood vessels, which is of mesodermal origin.[10] Additionally, simple squamous epithelium constitutes the mesothelium that lines serous membranes in body cavities such as the pleura and peritoneum.[12] Simple cuboidal epithelium is composed of a single layer of cube-shaped cells with roughly equal height and width, suited for roles in secretion and absorption.[13] This type lines the ducts of glands and the tubules of the kidneys, where it supports active and passive transport processes.[14] Simple columnar epithelium comprises a single layer of tall, rectangular cells that are at least twice as high as they are wide, often featuring apical specializations like microvilli or cilia for enhanced function.[10] It lines the digestive tract, including the small intestine, where goblet cells secrete mucus to aid absorption and protection.[12] This epithelium also appears in parts of the female reproductive tract for secretion and absorption.[10] Pseudostratified columnar epithelium is a single-layered variant that appears multilayered due to nuclei positioned at varying heights within the cells, though all cells contact the basement membrane.[13] It is typically ciliated and goblet cell-rich, lining the respiratory tract to propel mucus and trapped particles via coordinated ciliary movement.[12] This type also occurs in certain male reproductive ducts for secretory purposes.[10] Overall, the single-layer structure of simple epithelium enables minimal diffusion distances, optimizing it for transport, exchange, and secretory functions across various organs.[13] Unlike thicker stratified forms, it provides a delicate barrier supported by the basement membrane for anchorage and selective permeability.[10]Stratified Epithelium

Stratified epithelium is characterized by multiple layers of cells, with only the basal layer in direct contact with the basement membrane, while superficial layers are nourished via diffusion from underlying connective tissue. This multi-layered arrangement provides enhanced durability compared to single-layered epithelia, particularly in areas subject to mechanical stress or abrasion. Classification of stratified epithelium is based primarily on the morphology of the cells in the apical (surface) layer, such as squamous, cuboidal, or columnar shapes.[10] The most prevalent subtype is stratified squamous epithelium, which features flattened cells in the superficial layer and serves as a robust protective covering. In keratinized forms, as seen in the epidermis of the skin, the surface cells undergo terminal differentiation to produce a tough, waterproof barrier; non-keratinized variants line moist mucosal surfaces, such as the esophagus and vagina, where flexibility and moisture retention are essential. Stratified cuboidal and columnar epithelia are rarer, typically appearing in the ducts of exocrine glands like those of the salivary or sweat glands, where they facilitate secretion while offering moderate protection. Transitional epithelium, unique to the urinary tract including the bladder, consists of 5–7 layers when relaxed, appearing cuboidal to columnar, but stretches to a thinner, squamous-like configuration upon distension, allowing organ expansion without rupture.[8][15] A key adaptation in certain stratified epithelia, particularly keratinized stratified squamous types, is the process of keratinization, during which proliferating basal cells migrate upward, synthesize intermediate filament keratins, and fill their cytoplasm with these proteins, culminating in nuclear degeneration and formation of a compact, anucleate stratum corneum for impermeability to water and pathogens. In parakeratinized variants, such as the lining of the gingiva or parts of the oral mucosa, cells retain their nuclei in the surface layer, providing a slightly less rigid but still protective barrier suitable for semi-exposed environments. Overall, the thickness and layered structure of stratified epithelium confer superior mechanical and chemical resistance, shielding underlying tissues from wear, desiccation, and microbial invasion in high-risk locations.[16][17][18]Structure

Locations in the Body

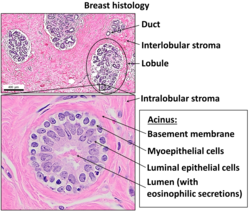

Epithelial tissues form a continuous covering over the external surface of the body and line the internal cavities and lumens of organs, providing a protective interface with the environment, but they do not line synovial joint cavities or directly contact free body fluids such as blood plasma beyond vascular endothelia.[19] This distribution ensures that epithelia separate the internal milieu from external or luminal contents across diverse anatomical sites. On external surfaces, stratified squamous keratinized epithelium predominates, forming the epidermis of the skin to withstand abrasion and environmental exposure.[20] In contrast, non-keratinized stratified squamous epithelium lines moist external or transitional areas, such as the cornea of the eye and the oral cavity, where flexibility and moisture retention are essential.[10] Internally, simple squamous epithelium lines sites requiring minimal barrier thickness for diffusion, including the alveoli of the lungs, the endothelium of blood and lymphatic vessels, and the mesothelium of serous cavities like the pleura, peritoneum, and pericardium.[10] Pseudostratified ciliated columnar epithelium covers the respiratory tract from the nasal cavity to the bronchioles, facilitating mucociliary clearance.[21] Simple columnar epithelium lines the gastrointestinal tract, including the stomach, intestines, and gallbladder, as well as the endometrium of the uterus, supporting absorption and secretion.[21] Transitional epithelium, capable of stretching, is found in the urinary system, lining the ureters, bladder, and proximal urethra.[20] In glandular structures, simple cuboidal or columnar epithelium forms the linings of small ducts in exocrine glands such as salivary, sweat, and mammary glands, while stratified cuboidal or columnar variants appear in larger ducts of salivary and sweat glands.[21] Endocrine glands, though lacking ducts, feature cuboidal or columnar epithelia in their secretory acini.[10] These arrangements allow epithelia to integrate into both covering and glandular roles throughout the body.Basement Membrane

The basement membrane is a thin, acellular sheet-like layer of extracellular matrix that serves as the foundational interface between epithelial cells and the underlying connective tissue. It typically measures 50–100 nm in thickness, though this can vary by tissue, and consists of two principal sublayers: the basal lamina and the reticular lamina. The basal lamina, closest to the epithelium, is an electron-dense structure known as the lamina densa, primarily composed of type IV collagen, laminin, perlecan (a heparan sulfate proteoglycan), and nidogen, which together form a self-assembled network providing tensile strength and molecular sieving with pores around 10 nm in size. The reticular lamina, adjacent to the connective tissue, comprises coarser type III collagen fibers and fibronectin, anchoring the basal lamina to the underlying stroma.[22] Formation of the basement membrane involves coordinated secretion by both epithelial cells and adjacent mesenchymal or connective tissue cells, resulting in a dynamic, self-assembling structure. Laminin initiates assembly by binding to cell surface receptors, recruiting type IV collagen to form a scaffold, followed by integration of perlecan and nidogen for stabilization.[22] Epithelial attachment occurs via hemidesmosomes, specialized multiprotein complexes at the basal cell surface that link the cytoskeleton to the laminin-rich basal lamina through α6β4-integrin and collagen XVII, ensuring stable anchorage.[23] The basement membrane fulfills multiple essential functions, including mechanical support to maintain epithelial integrity against shear forces and as a selective barrier for filtration. In the kidney, the glomerular basement membrane acts as a critical component of the filtration barrier, restricting passage of proteins larger than albumin while allowing water and small solutes, due to its specialized composition and charge-selective properties from heparan sulfate in perlecan.[24] It also guides cell migration during tissue repair and morphogenesis by providing directional cues through its protein gradients and stiffness, facilitating processes like wound healing without allowing uncontrolled invasion. Variations in basement membrane structure adapt to tissue-specific demands; for instance, it is thicker in the skin (up to several hundred nanometers) to withstand mechanical stress, incorporating additional anchoring fibrils of type VII collagen. In certain endothelia, such as glomerular capillaries, the membrane exhibits fenestrations or regional discontinuities that enhance permeability for exchange while preserving barrier function.[24] These adaptations highlight its role as a versatile scaffold tailored to local physiological needs.Cell Junctions and Polarity

Epithelial cells exhibit a distinct apical-basal polarity, characterized by specialized domains of the plasma membrane that enable directed functions such as absorption, secretion, and barrier formation. The apical domain, facing the lumen or external environment, features structural specializations like microvilli, which are actin-supported projections that increase surface area for absorption in epithelia such as the intestinal lining; cilia, motile or primary structures that facilitate fluid movement or sensing in respiratory and renal epithelia; and stereocilia, longer actin-based projections in sensory epithelia like the inner ear for mechanotransduction.[25] In contrast, the basolateral domain, encompassing the lateral surfaces between cells and the basal surface adjacent to the underlying tissue, is enriched with ion transport proteins, including the Na⁺/K⁺-ATPase pump, which maintains electrochemical gradients essential for secondary active transport across the epithelium.[26] This polarity is reinforced by intercellular junctions that segregate membrane components and prevent mixing between domains.[27] Intercellular junctions in epithelia are categorized into occluding, anchoring, and communicating types, each contributing to tissue integrity and functional compartmentalization. Tight junctions, also known as zonula occludens, form a continuous belt-like seal around the apical-lateral boundary of cells, composed primarily of claudins and occludin proteins that interact with zonula occludens (ZO) scaffolding proteins to link to the actin cytoskeleton.[25] These junctions prevent paracellular leakage of solutes and maintain polarity by restricting the diffusion of membrane lipids and proteins between apical and basolateral domains.[27] Adherens junctions, or zonula adherens, lie immediately basal to tight junctions in a belt-like configuration, featuring cadherin molecules extracellularly linked to β-catenin, α-catenin, and actin filaments intracellularly, providing mechanical adhesion and enabling coordinated cell shape changes.[25] Desmosomes, spot-like anchoring junctions distributed throughout the lateral membranes, enhance resistance to mechanical stress by connecting cadherin family members (desmogleins and desmocollins) to intermediate keratin filaments via plaque proteins like desmoplakin and plakoglobin.[25] Gap junctions, formed by connexin proteins assembling into hexameric connexons that dock between adjacent cells, permit the passage of ions and small molecules (up to ~1 kDa) for metabolic and electrical coupling, with variable distribution across lateral domains.[27] Hemidesmosomes, located at the basal surface, anchor epithelial cells to the basement membrane through integrin receptors and plectin linking to keratin filaments, stabilizing the tissue against shear forces.[25] Collectively, these junctions establish a selective barrier: tight junctions regulate paracellular permeability to maintain ion and solute gradients, while adherens junctions and desmosomes ensure structural cohesion, allowing epithelia to withstand physiological stresses without compromising polarity or function.[27] For instance, in the kidney proximal tubule, this arrangement supports vectorial transport while preventing back-leakage.[25]Development and Embryology

Epithelial tissues originate from all three primary germ layers formed during gastrulation in the early embryo. The ectoderm gives rise to the epidermis of the skin and the neural epithelium lining the central nervous system.[8] The endoderm contributes to the epithelial linings of the gastrointestinal tract, respiratory system, and portions of the urinary tract.[8] Meanwhile, the mesoderm differentiates into endothelium, which lines blood and lymphatic vessels, and mesothelium, which covers body cavities such as the peritoneum and pleura.[8] Key morphogenetic processes during embryonic development involve dynamic transitions between epithelial and mesenchymal states. Epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) occurs when epithelial cells lose polarity and adhesion, adopting a migratory mesenchymal phenotype to facilitate tissue remodeling, as seen during gastrulation where epiblast cells ingress to form mesoderm and endoderm.[28] This is followed by mesenchymal-epithelial transition (MET), where mesenchymal cells regain epithelial characteristics, such as tight junctions and apical-basal polarity, to form structured epithelia during organogenesis.[29] These reversible transitions are essential for shaping epithelial architectures in developing organs. Specific examples of epithelial morphogenesis include branching in the lung and kidney, where initial epithelial buds protrude and bifurcate iteratively under the influence of signaling molecules like FGF10, generating complex ductal networks.[30] In early embryos, cavitation transforms a solid mass of ectodermal cells into a hollow structure by programmed cell death and fluid accumulation, establishing the blastocyst cavity and later organ lumens.[31] In humans, initial epithelial formation begins around weeks 3-4 post-fertilization during gastrulation and neurulation, with subtype differentiation continuing through organogenesis into week 8.[32] A notable classification debate concerns endothelium and mesothelium, which exhibit epithelial properties like sheet-like organization and barrier function but derive from mesoderm rather than ectoderm or endoderm, leading some sources to describe them as specialized mesenchymal-derived epithelia.[33]Stem Cells and Regeneration

Epithelial tissues maintain their integrity through specialized stem cell populations residing in distinct niches that support self-renewal and differentiation. In stratified epithelia, such as the skin, stem cells are primarily located in the basal layer, where they anchor to the basement membrane and respond to local signals for tissue homeostasis. A prominent example is the bulge region of hair follicles, which harbors multipotent stem cells capable of generating new follicles during the hair cycle and contributing to epidermal repair.[34] These bulge cells exhibit quiescence and high proliferative potential, ensuring long-term tissue maintenance.[35] In contrast, simple epithelia, like the intestinal lining, feature label-retaining cells that slowly cycle and serve as stem cells. In intestinal crypts, Lgr5+ cells at the crypt base act as active stem cells, continuously producing progeny to replenish the epithelium while resisting differentiation.[36] These niches provide a protective microenvironment, including supportive stromal cells and signaling molecules, that regulates stem cell fate.[37] Epithelial renewal relies on precise pathways that balance proliferation and differentiation to sustain tissue function. Stem cells often undergo asymmetric division, generating one self-renewing daughter cell and one committed progenitor, thereby preserving the stem pool while producing cells for expansion.[38] This process is crucial for homeostasis in high-turnover tissues, preventing exhaustion of the stem cell reservoir. Progenitors derived from these divisions become transit-amplifying cells, which rapidly proliferate through symmetric divisions to amplify cell numbers before terminally differentiating into functional epithelial types.[39] In the intestine, for instance, Lgr5+ stem cells give rise to transit-amplifying cells that migrate upward along the villus axis, differentiating within days. Epithelial turnover rates vary by tissue: the intestinal epithelium renews every 3-5 days, skin epidermis every 28 days, and liver hepatocytes exhibit slower renewal with a turnover of approximately 300-500 days under normal conditions.[40][41] Regeneration of epithelial tissues following injury involves coordinated migration, proliferation, and reformation of barriers, often triggered by growth factors. During wound healing, surviving epithelial cells at the injury edge migrate to cover the defect, a process enhanced by epidermal growth factor (EGF), which stimulates proliferation and motility of keratinocytes.[42] Wnt signaling further promotes regeneration by activating β-catenin-dependent pathways that drive stem cell proliferation and inhibit differentiation, facilitating re-epithelialization in skin and intestinal wounds.[43] These mechanisms ensure rapid restoration of tissue architecture without scarring in many cases. Recent advances in regenerative biology have leveraged epithelial stem cells for innovative models and therapies. Organoid cultures derived from Lgr5+ intestinal stem cells or skin bulge cells recapitulate epithelial architecture and function, enabling precise disease modeling for conditions like inflammatory bowel disease and high-throughput drug screening.[44] As of November 2025, organoid-derived therapies from epithelial stem cells are entering clinical trials for conditions like inflammatory bowel disease, highlighting their translational potential.[45] These three-dimensional models highlight stem cell plasticity, where cells adapt to niche perturbations. Additionally, CRISPR-based studies have elucidated stem cell plasticity in cancer resistance; for example, CRISPR/dCas9-mediated epigenetic editing in breast epithelial cancer cells reactivates tumor-suppressive microRNAs, reducing stemness and enhancing sensitivity to therapies by modulating plasticity-driven resistance.[46] Such findings underscore the therapeutic potential of targeting stem cell dynamics to overcome epithelial-derived malignancies.Functions

Protection and Barrier Functions

The epithelium serves as the body's primary physical barrier, forming a continuous sheet of cells that shields underlying tissues from mechanical stress, abrasion, and pathogen invasion. In stratified epithelia, such as the epidermis of the skin, multiple layers of cells provide resilience against physical damage; the outermost stratum corneum consists of dead, keratinized keratinocytes that resist wear and tear while preventing water loss and desiccation.[8] Tight junctions, composed of proteins like occludin and claudins, seal the intercellular spaces in epithelial sheets, blocking paracellular pathways for microbial entry and maintaining compartmentalization between external environments and internal tissues.[47] These junctions are particularly crucial in simple epithelia lining cavities, where they prevent leakage of harmful substances.[48] Chemical defenses further enhance the epithelial barrier by creating an inhospitable environment for invaders. Keratinization in stratified squamous epithelia, such as the skin and oral mucosa, produces a tough, water-repellent layer that withstands acids, bases, and dehydration, with filaggrin aiding in the aggregation of keratin filaments for structural integrity.[49] In mucosal epithelia, mucus secreted by goblet cells forms a viscoelastic gel that traps microbes, allergens, and particulates, facilitating their removal through ciliary action in the respiratory tract or peristalsis in the gastrointestinal tract.[48] This mucociliary clearance mechanism effectively neutralizes threats before they reach deeper tissues.[49] Selective permeability mechanisms allow the epithelium to filter essential molecules while excluding toxins and large pathogens. The basement membrane, a specialized extracellular matrix beneath the epithelium, acts as a selective sieve that restricts the passage of macromolecules and promotes tissue organization, with components like laminin and collagen IV contributing to its filtration properties.[49] The apical glycocalyx, a carbohydrate-rich coating on epithelial cell surfaces, repels bacterial adhesion and modulates interactions with the environment, enhancing barrier selectivity in areas exposed to fluids like urine or saliva. Epithelial cells integrate immune functions by producing antimicrobial peptides, such as defensins, which directly kill bacteria, fungi, and viruses at the barrier surface. These peptides, expressed constitutively or induced by microbial signals, disrupt pathogen membranes and recruit immune cells, bridging physical protection with innate immunity.[50] Pattern recognition receptors on epithelial cells further amplify this response by detecting danger signals and initiating localized inflammation.[51] Representative examples illustrate these protective roles across body systems. The skin's epidermis, a keratinized stratified epithelium, defends against ultraviolet radiation, mechanical abrasion, and microbial colonization through its multi-layered structure and lipid barriers.[8] In the urinary tract, the urothelium employs tight junctions, a specialized plaque layer, and antimicrobial factors to resist urine toxins, osmotic stress, and bacterial ascent, preventing infections like cystitis.[49] Similarly, respiratory and gastrointestinal epithelia rely on mucus and defensins to trap and eliminate airborne or ingested pathogens, underscoring the epithelium's adaptive barrier strategies.[48]Secretion and Absorption

Epithelial tissues play a central role in secretion, releasing substances such as enzymes, hormones, and fluids to support physiological processes. Exocrine glands, composed of epithelial cells, secrete their products through ducts onto epithelial surfaces or into body cavities, as seen in the production of sweat by eccrine glands and saliva by salivary glands.[52] In contrast, endocrine glands lack ducts and release hormones directly into the bloodstream; for example, thyroid follicular epithelial cells secrete thyroid hormones like thyroxine to regulate metabolism.[53] Secretory mechanisms in exocrine glands vary: merocrine secretion involves exocytosis without cell loss, as in pancreatic acinar cells releasing digestive enzymes; apocrine secretion releases portions of the cell apex, exemplified by mammary gland milk production; and holocrine secretion entails whole-cell disintegration, as in sebaceous glands producing sebum.[52] Exocrine glands are classified structurally as unicellular or multicellular. Unicellular glands consist of single epithelial cells, such as goblet cells in the respiratory and gastrointestinal tracts that secrete mucus to lubricate surfaces.[54] Multicellular glands feature organized secretory units and ducts, categorized by shape as tubular (straight or branched, like intestinal glands), acinar (also called alveolar, rounded sacs as in salivary glands), or coiled (twisted tubes, such as eccrine sweat glands).[55] Absorption by epithelial tissues involves the uptake of nutrients, ions, and water, facilitated by structural adaptations and transport proteins. In the small intestine, microvilli on the apical surface of enterocytes dramatically increase the absorptive area, enabling efficient nutrient capture from the lumen.[56] Active transport mechanisms, such as the sodium-glucose cotransporter (SGLT1) on the apical membrane, couple glucose uptake with sodium influx, powered by the sodium gradient maintained by basolateral Na+/K+-ATPase pumps.[56] Epithelial polarity underpins these processes through vectorial transport, where distinct apical and basolateral domains direct material flow. In renal tubules, for instance, polarized proximal tubule cells reabsorb glucose and ions from the filtrate into the bloodstream via apical SGLT transporters and basolateral efflux pathways, preventing loss while maintaining homeostasis.[57] This directional movement, enabled by the asymmetric distribution of transporters, exemplifies how epithelial architecture supports net absorption or secretion.[58] Overall, human epithelia manage the secretion and absorption of approximately 200 liters of fluid daily, with the renal proximal tubules alone reabsorbing about 180 liters of glomerular filtrate and the gastrointestinal tract handling an additional 9 liters across its mucosa.[59]Sensory and Immune Roles

Epithelial tissues play crucial roles in sensory perception by housing specialized structures that detect environmental stimuli. In the olfactory epithelium, a pseudostratified columnar epithelium, ciliated sensory neurons extend cilia into the nasal cavity to facilitate chemosensation, binding odorant molecules and transducing chemical signals into neural impulses.[60] Similarly, in the oral cavity, stratified squamous epithelium contains taste buds composed of specialized epithelial cells that detect tastants such as sweet, sour, salty, bitter, and umami through chemoreceptors on their apical surfaces.[61] The retinal pigment epithelium, a simple cuboidal layer adjacent to photoreceptors, supports visual sensing by phagocytosing shed outer segments of photoreceptors and recycling visual pigments, thereby maintaining the sensory function of the retina.[62] Beyond chemosensation and photosensation, epithelial cilia contribute to mechanosensation in various tissues. For instance, motile cilia in the respiratory epithelium beat coordinately to propel mucus and trapped debris outward, sensing and responding to mechanical forces from airflow and particles to clear the airways.[63] Epithelial cells also form a frontline defense in innate immunity through pattern recognition receptors like Toll-like receptors (TLRs), which detect pathogen-associated molecular patterns on microbes. Upon activation, TLRs in epithelial cells trigger signaling cascades leading to the production and release of cytokines, such as interleukin-8 (IL-8), which recruits neutrophils to sites of infection.[64] In the skin, keratinocytes produce antimicrobial peptides (AMPs), including defensins and cathelicidins, that directly kill pathogens and modulate immune responses, enhancing barrier integrity against microbial invasion.[65] Epithelium serves as a physical and immunological barrier preventing microbiome dysbiosis, where imbalances in microbial communities can lead to inflammation; epithelial tight junctions and secreted mucins maintain selective permeability while TLR-mediated sensing calibrates microbial tolerance.[66] Recent advances highlight epithelial-microbiome crosstalk in maintaining gut barrier integrity. Studies from 2024 and 2025 demonstrate that intestinal epithelial cells sense microbial metabolites via receptors such as G protein-coupled receptors, influencing stem cell proliferation and differentiation to repair the barrier during perturbations.[67] In inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), dysregulated stem cell-immune interactions, driven by microbiome alterations, exacerbate epithelial damage; for example, NFAT5 transcription factor in epithelial cells mediates microbiota-induced immune signaling to promote regeneration and suppress chronic inflammation.[68] These findings underscore the dynamic role of epithelium in integrating microbial cues with immune homeostasis.Clinical Aspects

Epithelial Disorders and Diseases

Epithelial disorders encompass a range of non-neoplastic pathologies that impair the integrity, function, and regenerative capacity of epithelial tissues, often leading to compromised barrier functions and increased vulnerability to secondary complications. These conditions can be inherited, resulting from genetic mutations that disrupt key structural or transport proteins in epithelial cells, or acquired through environmental, hormonal, or inflammatory insults that alter epithelial architecture and physiology. Inflammatory processes further exacerbate these disruptions by targeting epithelial junctions and polarity, while emerging research highlights the role of microbial imbalances in perpetuating erosive damage. Inherited epithelial disorders primarily arise from mutations affecting critical components of epithelial structure and function. Cystic fibrosis, caused by mutations in the CFTR gene, leads to defective chloride ion transport in airway epithelial cells, resulting in abnormally viscous mucus accumulation and impaired mucociliary clearance. This genetic defect, most commonly the F508del mutation, manifests as recurrent respiratory infections and progressive lung damage due to the failure of epithelial ion homeostasis. Similarly, epidermolysis bullosa involves mutations in genes encoding basement membrane proteins, such as type VII collagen in dystrophic forms, causing fragility at the dermal-epidermal junction and recurrent blistering upon minor trauma. These inherited conditions underscore the essential role of genetic integrity in maintaining epithelial adhesion and transport mechanisms. Acquired epithelial disorders often stem from chronic environmental exposures or physiological changes that induce adaptive or degenerative responses in epithelial tissues. Squamous metaplasia, for instance, occurs in the bronchial epithelium of smokers, where chronic irritation replaces the normal pseudostratified ciliated columnar epithelium with stratified squamous cells, potentially contributing to airway obstruction in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Hormonal shifts, such as estrogen decline post-menopause, can lead to vaginal epithelial atrophy, characterized by thinning of the multilayered squamous epithelium, reduced glycogen content, and increased susceptibility to irritation and infection. These acquired alterations highlight how external stressors can reprogram epithelial differentiation and thickness, altering tissue resilience. Inflammatory epithelial disorders involve immune-mediated attacks that disrupt barrier integrity and cellular architecture. In eczema, also known as atopic dermatitis, skin barrier dysfunction arises from filaggrin gene mutations and environmental triggers, leading to impaired stratum corneum formation and transepidermal water loss, which initiates a cycle of inflammation and allergen penetration. Celiac disease exemplifies intestinal epithelial inflammation, where gluten peptides trigger an adaptive immune response, recruiting cytotoxic T cells that damage enterocytes and cause villous atrophy, crypt hyperplasia, and malabsorption. These processes compromise the selective permeability of epithelial layers, facilitating chronic inflammation and nutrient deficits. Recent studies post-2023 have linked microbiome dysbiosis to the progression of epithelial erosive disorders, such as oral lichen planus, where imbalances in bacteriome and mycobiome compositions correlate with erosive lesions and altered mucosal barrier function. In erosive oral lichen planus, reduced diversity in fungal and bacterial communities exacerbates epithelial ulceration and immune dysregulation, suggesting a bidirectional interplay between microbial shifts and tissue damage. The overarching impact of these epithelial disorders is heightened susceptibility to infections, as compromised barriers allow pathogen invasion and amplify inflammatory cascades. For example, disrupted epithelial junctions in inflammatory conditions facilitate microbial translocation, leading to secondary infections that perpetuate tissue damage and systemic complications.Neoplasms and Cancer

Neoplasms of the epithelium, known as carcinomas, represent the most common type of cancer, accounting for 80% to 90% of all human malignancies.[69] These tumors arise from epithelial cells and are responsible for approximately 80% to 90% of global cancer deaths, with major contributors including lung, colorectal, and breast cancers.[70] Unlike sarcomas, which originate from mesenchymal tissues such as connective or muscle cells and comprise only about 1% of cancers, carcinomas develop in the lining of organs and cavities.[71] Carcinomas are classified into subtypes based on the epithelial tissue of origin, with adenocarcinomas and squamous cell carcinomas being the most prevalent. Adenocarcinomas form in glandular epithelial cells that produce mucus or digestive juices, commonly affecting organs like the lung, colon, and pancreas; for instance, lung adenocarcinoma is the leading subtype of non-small cell lung cancer.[72] Squamous cell carcinomas arise from flat, scale-like squamous epithelial cells, frequently occurring in the skin, cervix, and respiratory tract; examples include cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma and cervical squamous cell carcinoma linked to human papillomavirus infection.[73] Benign epithelial neoplasms, such as adenomas, are non-invasive glandular growths that do not metastasize but can progress to malignancy if dysplastic changes occur, contrasting with malignant carcinomas that exhibit uncontrolled proliferation and potential for distant spread.[70] Key mechanisms driving carcinoma development and progression include genetic mutations, epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT), and chronic inflammation. Mutations in the TP53 tumor suppressor gene, the most frequently altered gene in cancers, impair DNA repair and apoptosis, occurring in over 50% of carcinomas.[74] Activating mutations in the KRAS oncogene, found in about 30% of epithelial tumors including colorectal and lung adenocarcinomas, promote uncontrolled cell growth and survival.[75] EMT enables metastatic dissemination by allowing epithelial cells to lose polarity and adhesion, acquiring migratory mesenchymal traits through pathways like TGF-β signaling.[76] Chronic inflammation, often from persistent infections or irritants, fosters a tumor-promoting microenvironment by releasing cytokines and growth factors that support angiogenesis and immune evasion.[77] Recent advances since 2023 have illuminated the role of epithelial stem cells in tumorigenesis, revealing that many carcinomas originate from or are sustained by cancer stem cells (CSCs) within the epithelial hierarchy, which exhibit self-renewal and therapy resistance.[78] Immunotherapies targeting PD-L1, a key immune checkpoint expressed on many epithelial tumor cells, have shown enhanced efficacy in combination regimens for carcinomas like squamous cell lung and cutaneous types, improving response rates in advanced disease.[79] Liquid biopsies detecting circulating tumor cells (CTCs) from epithelial cancers offer non-invasive monitoring of metastasis and treatment response, with 2024-2025 studies demonstrating their utility in profiling tumor heterogeneity and CSC markers.[80]Diagnostic and Therapeutic Approaches

Diagnosis of epithelial conditions primarily relies on histological examination using hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining, which reveals key morphological features such as cell polarity, stratification, and basement membrane integrity in tissue samples. This technique allows pathologists to differentiate normal epithelium from pathological states, including dysplasia or invasion, by highlighting nuclear and cytoplasmic details essential for identifying epithelial architecture. Immunohistochemistry (IHC) further enhances diagnostic precision by employing antibodies against cytokeratins, which serve as specific markers for epithelial cells across various tissues. Cytokeratins, intermediate filament proteins, exhibit tissue-specific expression patterns—such as CK7 in lung and CK20 in gastrointestinal epithelium—enabling the classification of epithelial origin in tumors and confirmation of epithelial involvement in inflammatory or degenerative processes. Biopsy procedures, often guided by endoscopy or fine-needle aspiration, are crucial for assessing basement membrane integrity, where disruptions signal potential malignancy or chronic injury in epithelial layers. Advanced imaging modalities provide non-invasive or minimally invasive alternatives for epithelial evaluation, particularly in accessible sites like the skin. Confocal microscopy offers high-resolution, in vivo visualization of cellular details and junctions in superficial epithelia, aiding in the diagnosis of dermatological disorders without tissue excision. Optical coherence tomography (OCT) complements this by delivering cross-sectional images of epithelial thickness and subsurface structures, proving valuable for monitoring skin barrier function and early lesion detection. For in vitro identification and modeling, primary epithelial cells are cultured using feeder cell layers, such as irradiated fibroblasts, to support attachment and proliferation while mimicking the stromal environment.[81] This method preserves epithelial phenotype and enables functional studies of polarity and differentiation. Organoids, derived from primary epithelial stem cells embedded in extracellular matrix like Matrigel, recapitulate three-dimensional tissue architecture and are widely used for disease modeling and drug screening in organs such as the intestine and lung.[82] These self-organizing structures maintain epithelial-specific functions, including secretion and barrier formation, without relying on feeder cells in advanced protocols.[83] Therapeutic strategies for epithelial disorders target specific functions and pathologies, often leveraging the tissue's regenerative potential. Topical retinoids, such as tretinoin, promote epithelial differentiation and turnover in skin conditions like acne and psoriasis by activating retinoic acid receptors, leading to normalized keratinization and reduced hyperproliferation.[84] In genetic epithelial diseases like cystic fibrosis (CF), gene therapy delivers functional CFTR genes to airway epithelial cells via viral vectors, aiming to restore chloride transport and mucociliary clearance.[85] For epithelial-derived malignancies, targeted therapies such as EGFR tyrosine kinase inhibitors (e.g., erlotinib) inhibit signaling pathways in lung adenocarcinoma, improving survival in patients with EGFR mutations by blocking uncontrolled epithelial proliferation.[86] Recent advances since 2023 have integrated artificial intelligence (AI) into pathology workflows for epithelial carcinoma grading, where machine learning algorithms analyze H&E-stained slides to quantify features like nuclear atypia and mitotic activity with higher consistency than manual methods.[87] This AI assistance accelerates diagnosis and reduces inter-observer variability in assessing epithelial neoplasms. In regenerative medicine, stem cell transplants using epithelial progenitor cells have shown promise for burn wound healing, promoting rapid re-epithelialization and scar minimization through autologous grafting techniques.[88] A major challenge in epithelial therapeutics stems from the tissue's avascular nature, which limits nutrient and oxygen diffusion, thereby hindering systemic drug penetration and efficacy in multilayered or stratified epithelia.[89] This avascularity necessitates localized delivery systems, such as nanoparticles or hydrogels, to overcome diffusion barriers and sustain therapeutic concentrations at the epithelial surface.[90]Terminology

Etymology

The term epithelium derives from the Ancient Greek roots epi- ("upon" or "on") and thēlē ("nipple" or "teat"), alluding to the nipple-like glandular projections or coverings observed by early microscopists in tissues such as those on the lips or in glandular structures.[91][4] The word was coined in 1703 by Dutch anatomist Frederik Ruysch in the third volume of his Thesaurus Anatomicus, where he applied it to describe the translucent layer of tissue overlying small, teat-like elevations on a cadaver's lip.[4][91] Ruysch's usage marked the term's entry into anatomical literature, initially as a plural form (epithelia), which was later adopted and refined in the 18th and 19th centuries.[4] Early applications of "epithelium" were largely confined to glandular tissues and their secretory coverings, reflecting the limited microscopic resolution of the era.[4] By the mid-19th century, advances in histology led to its broader application, encompassing all continuous sheets of cells that line body surfaces, cavities, and organ lumens; this expansion was significantly influenced by Rudolf Virchow's foundational work in Cellular Pathology (1858), which integrated epithelial concepts into the framework of cellular pathology and tumor classification, such as epitheliomas.[92][4] A related term, epithelioid, emerged in the late 19th century to describe cells in non-epithelial tissues (e.g., macrophages in granulomas) that morphologically resemble epithelial cells, often in pathological contexts like inflammation or neoplasia.[93]Pronunciation and Plural Forms

The term epithelium is pronounced in American English as /ˌɛpəˈθiliəm/ (EP-uh-THEE-lee-uhm), with the primary stress on the third syllable and a schwa sound in the second syllable.[94] In British English, the pronunciation is /ˌɛpɪˈθiːlɪəm/ (EP-i-THEE-lee-uhm), featuring a short i in the second syllable and a longer ee sound in the third, with slight regional variations in vowel reduction.[95] These phonetic conventions ensure clarity in scientific communication, where precise articulation distinguishes the term from similar-sounding words. The International Phonetic Alphabet (IPA) transcription /ˌɛpɪˈθiːliəm/ serves as a standardized guide for global consistency, accommodating non-native speakers by representing the core sounds across dialects.[96] The plural form of epithelium is epithelia, reflecting its Latin-derived irregular pluralization; epitheliums is nonstandard and should be avoided in formal usage.[94] The singular form refers to specific instances, such as "the epithelium of the intestine," while epithelia denotes multiple types or general occurrences.[97] The related adjective is epithelial, used to describe structures or processes involving this tissue, as in "epithelial cells."[98] Common mispronunciations, such as "epi-THEE-lee-um" with misplaced stress or altered vowels, can hinder effective discourse and are best avoided by adhering to the established IPA guidelines.[99]References

- https://en.wiktionary.org/wiki/epithelioid