Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Germ layer

View on WikipediaThis article needs additional citations for verification. (September 2022) |

A germ layer is a primary layer of cells that forms during embryonic development.[1] The three germ layers in vertebrates are particularly pronounced; however, all eumetazoans (animals that are sister taxa to the sponges) produce two or three primary germ layers. Some animals, like cnidarians, produce two germ layers (the ectoderm and endoderm) making them diploblastic. Other animals such as bilaterians produce a third layer (the mesoderm) between these two layers, making them triploblastic. Germ layers eventually give rise to all of an animal's tissues and organs through the process of organogenesis.

History

[edit]

Caspar Friedrich Wolff observed organization of the early embryo in leaf-like layers. In 1817, Heinz Christian Pander discovered three primordial germ layers while studying chick embryos. Between 1850 and 1855, Robert Remak had further refined the germ cell layer (Keimblatt) concept, stating that the external, internal and middle layers form respectively the epidermis, the gut, and the intervening musculature and vasculature.[2][3][4] The term "mesoderm" was introduced into English by Huxley in 1871, and "ectoderm" and "endoderm" by Lankester in 1873.

Evolution

[edit]

Among animals, sponges show the least amount of compartmentalization, having a single germ layer. Although they have differentiated cells (e.g. collar cells), they lack true tissue coordination. Diploblastic animals, Cnidaria and Ctenophora, show an increase in compartmentalization, having two germ layers, the endoderm and ectoderm. Diploblastic animals are organized into recognisable tissues. All bilaterian animals (from flatworms to humans) are triploblastic, possessing a mesoderm in addition to the germ layers found in Diploblasts. Triploblastic animals develop recognizable organs.

Development

[edit]Fertilization leads to the formation of a zygote. During the next stage, cleavage, mitotic cell divisions transform the zygote into a hollow ball of cells, a blastula. This early embryonic form undergoes gastrulation, forming a gastrula with either two or three layers (the germ layers). In all vertebrates, these progenitor cells differentiate into all adult tissues and organs.[5]

In the human embryo, after about three days, the zygote forms a solid mass of cells by mitotic division, called a morula. This then changes to a blastocyst, consisting of an outer layer called a trophoblast, and an inner cell mass called the embryoblast. Filled with uterine fluid, the blastocyst breaks out of the zona pellucida and undergoes implantation. The inner cell mass initially has two layers: the hypoblast and epiblast. At the end of the second week, a primitive streak appears. The epiblast in this region moves towards the primitive streak, dives down into it, and forms a new layer, called the endoderm, pushing the hypoblast out of the way (this goes on to form the amnion.) The epiblast keeps moving and forms a second layer, the mesoderm. The top layer is now called the ectoderm.[6]

Gastrulation occurs in reference to the primary body axis. Germ layer formation is linked to the primary body axis as well, however it is less reliant on it than gastrulation is. Hydractinia shows that germ layer formation that transpires as a mixed delamination.[7]

In mice, germ layer differentiation is controlled by two transcription factors: Sox2 and Oct4 proteins. These transcription factors cause the pluripotent mouse embryonic stem cells to select a germ layer fate. Sox2 promotes ectodermal differentiation, while Oct4 promotes mesendodermal differentiation. Each gene inhibits what the other promotes. Amounts of each protein are different throughout the genome, causing the embryonic stem cells to select their fate.[8]

The three germ layers

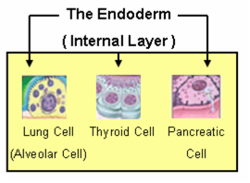

[edit]Endoderm

[edit]

The endoderm is one of the germ layers formed during animal embryonic development. Cells migrating inward along the archenteron form the inner layer of the gastrula, which develops into the endoderm.

The endoderm consists at first of flattened cells, which subsequently become columnar. It forms the epithelial lining of the whole of the digestive tract except part of the mouth and pharynx and the terminal part of the rectum (which are lined by involutions of the ectoderm). It also forms the lining cells of all the glands which open into the digestive tract, including those of the liver and pancreas; the epithelium of the auditory tube and tympanic cavity; the trachea, bronchi, and alveoli of the lungs; the bladder and part of the urethra; and the follicle lining of the thyroid gland and thymus.

The endoderm forms: the pharynx, the esophagus, the stomach, the small intestine, the colon, the liver, the pancreas, the bladder, the epithelial parts of the trachea and bronchi, the lungs, the thyroid, and the parathyroid.

Mesoderm

[edit]

The mesoderm germ layer forms in the embryos of triploblastic animals. During gastrulation, some of the cells migrating inward contribute to the mesoderm, an additional layer between the endoderm and the ectoderm.[9] The formation of a mesoderm leads to the development of a coelom. Organs formed inside a coelom can freely move, grow, and develop independently of the body wall while fluid cushions protects them from shocks.[10]

The mesoderm has several components which develop into tissues: intermediate mesoderm, paraxial mesoderm, lateral plate mesoderm, and chorda-mesoderm. The chorda-mesoderm develops into the notochord. The intermediate mesoderm develops into kidneys and gonads. The paraxial mesoderm develops into cartilage, skeletal muscle, and dermis. The lateral plate mesoderm develops into the circulatory system (including the heart and spleen), the wall of the gut, and wall of the human body.[11]

Through cell signaling cascades and interactions with the ectodermal and endodermal cells, the mesodermal cells begin the process of differentiation.[12]

The mesoderm forms: muscle (smooth and striated), bone, cartilage, connective tissue, adipose tissue, circulatory system, lymphatic system, dermis, dentine of teeth, genitourinary system, serous membranes, spleen and notochord.

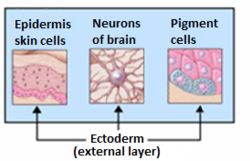

Ectoderm

[edit]

The ectoderm generates the outer layer of the embryo, and it forms from the embryo's epiblast.[13] The ectoderm develops into the surface ectoderm, neural crest, and the neural tube.[14]

The surface ectoderm develops into: epidermis, hair, nails, lens of the eye, sebaceous glands, cornea, tooth enamel, the epithelium of the mouth and nose.

The neural crest of the ectoderm develops into: peripheral nervous system, adrenal medulla, melanocytes, facial cartilage.

The neural tube of the ectoderm develops into: brain, spinal cord, posterior pituitary, motor neurons, retina.

Note: The anterior pituitary develops from the ectodermal tissue of Rathke's pouch.

Neural crest

[edit]Because of its great importance, the neural crest is sometimes considered a fourth germ layer.[15] It is, however, derived from the ectoderm.

See also

[edit]

References

[edit]- ^ Gilbert, Scott F (2003). "The Epidermis and the Origin of Cutaneous Structures". Developmental Biology. Sinauer Associates.

- ^ Remak, R. (1855). Untersuchungen über die Entwickelung der Wirbelthiere. Berlin: G. Reimer. link.

- ^ Collins, P.; Billett, F. S. (1995). "The terminology of early development: History, concepts, and current usage". Clinical Anatomy. 8 (6): 418–425. doi:10.1002/ca.980080610. PMID 8713164. S2CID 23450709.

- ^ Weyers, Wolfgang (2002). 150 Years of cell division. Dermatopathology: Practical & Conceptual, Vol. 8, No. 2. link Archived 2019-04-02 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ Gilbert, Scott F (2000). "Comparative Embryology". Developmental Biology. Sinauer Associates.

- ^ Gilbert, Scott F (2000). "Early Mammalian Development". Developmental Biology. Sinauer Associates.

- ^ Technau, Ulrich (September 2020). "Gastrulation and germ layer formation in the sea anemone Nematostella vectensis and other cnidarians". Mechanisms of Development. 163 103628. doi:10.1016/j.mod.2020.103628. ISSN 0925-4773. PMID 32603823. S2CID 220121520.

- ^ Thomson, Matt; Liu, Siyuan John; Zou, Ling-Nan; Smith, Zack; Meissner, Alexander; Ramanathan, Sharad (June 2011). "Pluripotency Factors in Embryonic Stem Cells Regulate Differentiation into Germ Layers". Cell. 145 (6): 875–889. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2011.05.017. ISSN 0092-8674. PMC 5603300. PMID 21663792.

- ^ Muhr, Jeremy; Ackerman, Kristin M. (2022), "Embryology, Gastrulation", StatPearls, Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing, PMID 32119281, retrieved 2022-02-27

- ^ "Coelom". Biology Dictionary. 2017-06-07. Archived from the original on 2022-02-21. Retrieved 2022-02-23.

- ^ Gilbert, Scott F (2003). "Paraxial and Intermediate Mesoderm". Developmental Biology. Sinauer Associates.

- ^ Brand, Thomas (1 June 2003). "Heart development: molecular insights into cardiac specification and early morphogenesis". Developmental Biology. 258 (1): 1–19. doi:10.1016/S0012-1606(03)00112-X. PMID 12781678.

- ^ Gilbert, Scott F (2003). "Early Mammalian Development". Developmental Biology. Sinauer Associates.

- ^ Gilbert, Scott F (2003). "The Central Nervous System and The Epidermis". Developmental Biology. Sinauer Associates.

- ^ Hall BK (2000). "The neural crest as a fourth germ layer and vertebrates as quadroblastic not triploblastic". Evolution & Development. 2 (1): 3–5. doi:10.1046/j.1525-142x.2000.00032.x. PMID 11256415. S2CID 27150120.