Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Tape recorder

View on Wikipedia

An audio tape recorder, also known as a tape deck, tape player or tape machine or simply a tape recorder, is a sound recording and reproduction device that records and plays back sounds usually using magnetic tape for storage. In its present-day form, it records a fluctuating signal by moving the tape across a tape head that polarizes the magnetic domains in the tape in proportion to the audio signal. Tape-recording devices include the reel-to-reel tape deck and the cassette deck, which uses a cassette for storage.

The use of magnetic tape for sound recording originated around 1930 in Germany as paper tape with oxide lacquered to it. Prior to the development of magnetic tape, magnetic wire recorders had successfully demonstrated the concept of magnetic recording, but they never offered audio quality comparable to the other recording and broadcast standards of the time. This German invention was the start of a long string of innovations that have led to present-day magnetic tape recordings.

Magnetic tape revolutionized both the radio broadcast and music recording industries. It gave artists and producers the power to record and re-record audio with minimal loss in quality as well as edit and rearrange recordings with ease. The alternative recording technologies of the era, transcription discs and wire recorders, could not provide anywhere near this level of quality and functionality.

Since some early refinements improved the fidelity of the reproduced sound, magnetic tape has been the highest quality analog recording medium available. As of the first decade of the 21st century, analog magnetic tape has been largely replaced by digital recording technologies.

History

[edit]-

An early experimental non-magnetic tape recorder patented in 1886 by Alexander Graham Bell's Volta Laboratory.

-

1909 analog tape recorder of Franklin C. Goodale. This machine had 15 Tracks

-

Franklin C. Goodale built the first working tape recorder in 1909 and got the patent for this invention

-

Prototype of the Goodale tape recorder. The patent is based on this machine.

Wax strip recorder

[edit]The earliest known audio tape recorder was a non-magnetic, non-electric version invented by Alexander Graham Bell's Volta Laboratory and patented in 1886 (U.S. patent 341,214). It employed a 3⁄16-inch-wide (4.8 mm) strip of wax-covered paper that was coated by dipping it in a solution of beeswax and paraffin and then had one side scraped clean, with the other side allowed to harden. The machine was of sturdy wood and metal construction and hand-powered by means of a knob fastened to a flywheel. The wax strip passed from one eight-inch reel around the periphery of a pulley (with guide flanges) mounted above the V-pulleys on the main vertical shaft, where it came in contact with either its recording or playback stylus. The tape was then taken up on the other reel. The sharp recording stylus, actuated by a vibrating mica diaphragm, cut the wax from the strip. In playback mode, a dull, loosely mounted stylus, attached to a rubber diaphragm, carried the reproduced sounds through an ear tube to its listener. Both recording and playback styluses, mounted alternately on the same two posts, could be adjusted vertically so that several recordings could be cut on the same 3⁄16-inch-wide (4.8 mm) strip.[1]

While the machine was never developed commercially, it somewhat resembled the modern magnetic tape recorder in its design. The tapes and machine created by Bell's associates, examined at one of the Smithsonian Institution's museums, became brittle, and the heavy paper reels warped. The machine's playback head was also missing. Otherwise, with some reconditioning, they could be placed into working condition.[1]

The waxed tape recording medium was later refined by Edison's wax cylinder, and became the first widespread sound recording technology, used for both entertainment and office dictation. However, recordings on wax cylinders were unable to be easily duplicated, making them both costly and time consuming for large-scale production. Wax cylinders were also unable to record more than 2 minutes of audio, a problem solved by gramophone discs.[2][3]

Celluloid strip recorder

[edit]

Franklin C. Goodale adapted movie film for analog audio recording. He received a patent for his invention in 1909. The celluloid film was inscribed and played back with a stylus, in a manner similar to the wax cylinders of Edison's gramophone. The patent description states that the machine could store six records on the same strip of film, side by side, and it was possible to switch between them.[4] In 1912, a similar process was used for the Hiller talking clock.[citation needed]

Photoelectric paper tape recorder

[edit]In 1932, after six years of developmental work, including a patent application in 1931,[5][6] Merle Duston, a Detroit radio engineer, created a tape recorder capable of recording both sounds and voice that used a low-cost chemically treated paper tape. During the recording process, the tape moved through a pair of electrodes which immediately imprinted the modulated sound signals as visible black stripes into the paper tape's surface. The audio signal could be immediately replayed from the same recorder unit, which also contained photoelectric sensors, somewhat similar to the various sound-on-film technologies of the era.[7][8]

Magnetic recording

[edit]Magnetic recording was conceived as early as 1878 by the American engineer Oberlin Smith[9][10] and demonstrated in practice in 1898 by Danish engineer Valdemar Poulsen.[11][12] Analog magnetic wire recording, and its successor, magnetic tape recording, involve the use of a magnetizable medium which moves with a constant speed past a recording head. An electrical signal, which is analogous to the sound that is to be recorded, is fed to the recording head, inducing a pattern of magnetization similar to the signal. A playback head can then pick up the changes in magnetic field from the tape and convert it into an electrical signal to be amplified and played back through a loudspeaker.

Wire recorders

[edit]

The first wire recorder was the Telegraphone invented by Valdemar Poulsen in the late 1890s. Wire recorders for law and office dictation and telephone recording were made almost continuously by various companies (mainly the American Telegraphone Company) through the 1920s and 1930s. These devices were mostly sold as consumer technologies after World War II.[citation needed]

Widespread use of wire recording occurred within the decades spanning from 1940 until 1960, following the development of inexpensive designs licensed internationally by the Brush Development Company of Cleveland, Ohio and the Armour Research Foundation of the Armour Institute of Technology (later Illinois Institute of Technology). These two organizations licensed dozens of manufacturers in the U.S., Japan, and Europe.[13] Wire was also used as a recording medium in black box voice recorders for aviation in the 1950s.[14]

Consumer wire recorders were marketed for home entertainment or as an inexpensive substitute for commercial office dictation recorders, but the development of consumer magnetic tape recorders starting in 1946, with the BK 401 Soundmirror, using paper-based tape,[15] gradually drove wire recorders from the market, being "pretty much out of the picture" by 1952.[16]

Early steel tape recorders

[edit]

In 1924 a German engineer, Kurt Stille, developed the Poulsen wire recorder as a dictating machine.[17] The following year a fellow German, Louis Blattner, working in Britain, licensed Stille's device and started work on a machine which would instead record on a magnetic steel tape, which he called the Blattnerphone.[18] The tape was 6 mm wide and 0.08 mm thick, traveling at 5 feet per second; the recording time was 20 minutes.

The BBC installed a Blattnerphone at Avenue House in September 1930 for tests, and used it to record King George V's speech at the opening of the India Round Table Conference on 12 November 1930. Though not considered suitable for music the machine continued in use and was moved to Broadcasting House in March 1932, a second machine also being installed. In September 1932, a new model was installed, using 3 mm tape with a recording time of 32 minutes.[19][20]

In 1933, the Marconi Company purchased the rights to the Blattnerphone, and newly developed Marconi-Stille recorders were installed in the BBC's Maida Vale Studios in March 1935.[21] The quality and reliability were slightly improved, though it still tended to be obvious that one was listening to a recording. A reservoir system containing a loop of tape helped to stabilize the speed. The tape was 3 mm wide and traveled at 1.5 meters/second.[12]

They were not easy to handle. The reels were heavy and expensive and the steel tape has been described as being like a traveling razor blade. The tape was liable to snap, particularly at joints, which at 1.5 meters/second could rapidly cover the floor with loops of the sharp-edged tape. Rewinding was done at twice the speed of the recording.[22]

Despite these drawbacks, the ability to make replayable recordings proved useful, and even with subsequent methods coming into use (direct-cut discs[23] and Philips-Miller optical film[24] the Marconi-Stilles remained in use until the late 1940s.[25]

Modern tape recorders

[edit]

Magnetic tape recording as we know it today was developed in Germany during the 1930s at BASF (then part of the chemical giant IG Farben) and AEG in cooperation with the state radio RRG. This was based on Fritz Pfleumer's 1928 invention of paper tape with oxide powder lacquered onto it. The first practical tape recorder from AEG was the Magnetophon K1, demonstrated in Berlin, Germany in 1935. Eduard Schüller of AEG built the recorders and developed a ring-shaped recording and playback head. It replaced the needle-shaped head which tended to shred the tape. Friedrich Matthias of IG Farben/BASF developed the recording tape, including the oxide, the binder, and the backing material. Walter Weber, working for Hans Joachim von Braunmühl at the RRG, discovered the AC biasing technique, which radically improved sound quality.[26]

During World War II, the Allies noticed that certain German officials were making radio broadcasts from multiple time zones almost simultaneously.[26] Analysts such as Richard H. Ranger believed that the broadcasts had to be transcriptions, but their audio quality was indistinguishable from that of a live broadcast[26] and their duration was far longer than was possible even with 16 rpm transcription discs.[a] In the final stages of the war in Europe, the Allies' capture of a number of German Magnetophon recorders from Radio Luxembourg aroused great interest. These recorders incorporated all the key technological features of modern analog magnetic recording and were the basis for future developments in the field.[citation needed]

Commercialization

[edit]American developments

[edit]Development of magnetic tape recorders in the late 1940s and early 1950s is associated with the Brush Development Company and its licensee, Ampex. The equally important development of the magnetic tape medium itself was led by Minnesota Mining and Manufacturing (3M) corporation.[citation needed] In 1938, S.J. Begun left Germany and joined the Brush Development Company in the United States, where work continued but attracted little attention until the late 1940s when the company released the very first consumer tape recorder in 1946: the Soundmirror BK 401.[15]<!—less reliable, but interesting refs: http://esrv.net/brush_bk401.html, http://www.radiomuseum.org/r/brush_bk401.html—> Several other models were quickly released in the following years. Tapes were initially made of paper coated with magnetite powder. In 1947/48 Minnesota Mining & Manufacturing Company (3M) replaced the paper backing with cellulose acetate or polyester, and coated it first with black oxide, and later, to improve signal-to-noise ratio and improve overall superior quality, with red oxide (gamma ferric oxide).[28][citation needed]

American audio engineer John T. Mullin and entertainer Bing Crosby were key players in the commercial development of magnetic tape. Mullin served in the U.S. Army Signal Corps and was posted to Paris in the final months of WWII. His unit was assigned to find out everything they could about German radio and electronics, including the investigation of claims that the Germans had been experimenting with high-energy directed radio beams as a means of disabling the electrical systems of aircraft. Mullin's unit soon amassed a collection of hundreds of low-quality magnetic dictating machines, but it was a chance visit to a studio at Bad Nauheim near Frankfurt while investigating radio beam rumors, that yielded the real prize.[citation needed]

Mullin was given two suitcase-sized AEG 'Magnetophon' high-fidelity recorders and fifty reels of recording tape. He had them shipped home[26] and over the next two years he worked on the machines constantly, modifying them and improving their performance. His major aim was to interest Hollywood studios in using magnetic tape for movie soundtrack recording.[citation needed]

Mullin gave two public demonstrations of his machines, and they caused a sensation among American audio professionals; many listeners literally could not believe that what they heard was not a live performance. By luck, Mullin's second demonstration was held at MGM Studios in Hollywood and in the audience that day was Bing Crosby's technical director, Murdo Mackenzie. He arranged for Mullin to meet Crosby and in June 1947 he gave Crosby a private demonstration of his magnetic tape recorders.[26]

Crosby, a top movie and singing star, was stunned by the amazing sound quality and instantly saw the huge commercial potential of the new machines. Live music was the standard for American radio at the time and the major radio networks didn't permit the use of disc recording in many programs because of their comparatively poor sound quality. Crosby disliked the regimentation of live broadcasts 39 weeks a year,[26] preferring the recording studio's relaxed atmosphere and ability to retain the best parts of a performance. He asked NBC to let him pre-record his 1944–45 series on transcription discs, but the network refused, so Crosby withdrew from live radio for a year. ABC agreed to let him use transcription discs for the 1946–47 season, but listeners complained about the sound quality.[26]

Crosby realised that Mullin's tape recorder technology would enable him to pre-record his radio show with high sound quality and that these tapes could be replayed many times with no appreciable loss of quality. Mullin was asked to tape one show as a test and was subsequently hired as Crosby's chief engineer to pre-record the rest of the series.[citation needed]

Crosby's season premiere on 1 October 1947 was the first magnetic tape broadcast in America.[26] He became the first major American music star to use tape to pre-record radio broadcasts, and the first to master commercial recordings on tape. The taped Crosby radio shows were painstakingly edited through tape-splicing to give them a pace and flow that was wholly unprecedented in radio.[b] Soon other radio performers were demanding the ability to pre-record their broadcasts with the high quality of tape, and the recording ban was lifted.[26]

Crosby invested $50,000 of his own money into the Californian electronics company Ampex, and the six-man concern (headed by Alexander M. Poniatoff, whose initials became part of the company name) soon became the world leader in the development of tape recording, with its Model 200 tape deck, released in 1948 and developed from Mullin's modified Magnetophons.[citation needed]

Tape recording at the BBC

[edit]

The BBC acquired some Magnetophon machines in 1946 on an experimental basis, and they were used in the early stages of the new Third Programme to record and play back performances of operas from Germany. Delivery of tape was preferred as live relays over landlines were unreliable in the immediate post-war period. These machines were used until 1952, though most of the work continued to be done using the established media.[29]

In 1948, a new British model became available from EMI: the BTR1. Though in many ways clumsy, its quality was good, and as it wasn't possible to obtain any more Magnetophons it was an obvious choice.[30]

In the early 1950s, the EMI BTR 2 became available; a much-improved machine and generally liked. The machines were responsive, could run up to speed quite quickly, had light-touch operating buttons, forward-facing heads (The BTR 1s had rear-facing heads which made editing difficult), and were quick and easy to do fine editing. It became the standard in recording rooms for many years and was in use until the end of the 1960s.[31]

In 1963, the Beatles were allowed to enhance their recordings at the BBC by overdubbing. The BBC didn't have any multi-track equipment; Overdubbing was accomplished by copying onto another tape.[32][33]

The tape speed was eventually standardized at 15 ips for almost all work at Broadcasting House, and at 15 ips for music and 7½ ips for speech at Bush House.[29]

Broadcasting House also used the EMI TR90 and a Philips machine which was lightweight but very easy and quick to use.[34] Bush House used several Leevers-Rich models.[29]

The Studer range of machines had become the studio recording industry standard by the 1970s, gradually replacing the aging BTR2s in recording rooms and studios. By the mid-2000s tape was pretty well out of use and had been replaced by digital playout[35] systems.[36]

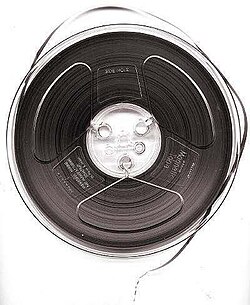

Standardized products

[edit]The typical professional audio tape recorder of the early 1950s used 1⁄4 in (6 mm) wide tape on 10+1⁄2 in (27 cm) reels, with a capacity of 2,400 ft (730 m). Typical speeds were initially 15 in/s (38.1 cm/s) yielding 30 minutes' recording time on a 2,400 ft (730 m) reel. Early professional machines used single-sided reels but double-sided reels soon became popular, particularly for domestic use. Tape reels were made from metal or transparent plastic.[citation needed]

Standard tape speeds varied by factors of two: 15 and 30 in/s were used for professional audio recording; 7+1⁄2 in/s (19.1 cm/s) for home audiophile prerecorded tapes; 7+1⁄2 and 3+3⁄4 in/s (19.1 and 9.5 cm/s) for audiophile and consumer recordings (typically on 7 in (18 cm) reels). 1+7⁄8 in/s (4.8 cm/s) and occasionally even 15⁄16 in/s (2.4 cm/s) and 15⁄32 in/s (1.2 cm/s) were used for voice, dictation, and applications where very long recording times were needed, such as logging police and fire department calls.[citation needed]

The 8-track tape standard, developed by Bill Lear in the mid-1960s, popularized consumer audio playback in automobiles in the USA. Eventually, this standard was replaced by the smaller and more reliable Compact Cassette, which was launched earlier in 1963.

Philips's development of the Compact Cassette in 1963 and Sony's development of the Walkman in 1979[37] led to widespread consumer use of magnetic audio tape. In 1990, the Compact Cassette was the dominant format in mass-market recorded music.[38][failed verification] The development of Dolby noise reduction technology in the 1960s brought audiophile-quality recording to the Compact Cassette also contributing to its popularity.[citation needed]

Later developments

[edit]Since their first introduction, analog tape recorders have experienced a long series of progressive developments resulting in increased sound quality, convenience, and versatility.[citation needed]

- Two-track and, later, multi-track heads permitted discrete recording and playback of individual sound sources, such as two channels for stereophonic sound, or different microphones during live recording. The more versatile machines could be switched to record on some tracks while playing back others, permitting additional tracks to be recorded in synchronization with previously recorded material such as a rhythm track.

- Use of separate heads for recording and playback (three heads total, counting the erase head) enabled monitoring of the recorded signal a fraction of a second after recording. Mixing the playback signal back into the record input also created a primitive echo generator. The use of separate record and play heads allowed each head to be optimized for its purpose rather than the compromise design required for a combined record/play head. The result was an improved signal-to-noise plus an extended frequency response.

- Dynamic range compression during recording and expansion during playback expanded the available dynamic range and improved the signal-to-noise ratio. dbx and Dolby Laboratories introduced add-on products in this area, originally for studio use, and later in versions for the consumer market. In particular, Dolby B noise reduction became very common in all but the least expensive cassette tape recorders.

- Computer-controlled analog tape recorders were introduced by Oscar Bonello in Argentina.[39] The mechanical transport used three DC motors and introduced two new advances: automated microprocessor transport control and automatic adjustment of bias and frequency response. In 30 seconds the recorder adjusted its bias for minimum THD and best frequency response to match the brand and batch of magnetic tape used. The microprocessor control of transport allowed fast location to any point on the tape.[40]

Operation

[edit]Electrical

[edit]Due to electromagnetism, electric current flowing in the coils of the tape head creates a fluctuating magnetic field. This causes the magnetic material on the tape, which is moving past and in contact with the head, to align in a manner proportional to the original signal. The signal can be reproduced by running the tape back across the tape head, where the reverse process occurs – the magnetic imprint on the tape induces a small current in the read head which approximates the original signal and is then amplified for playback. Many tape recorders are capable of recording and playing back simultaneously by means of separate record and playback heads.[41]

Mechanical

[edit]Modern professional recorders usually use a three-motor scheme. One motor with a constant rotational speed drives the capstan. Usually combined with a rubber pinch roller, it ensures that the tape speed does not fluctuate. The other two motors, which are called torque motors, apply equal and opposite torques to the supply and take-up reels during recording and playback functions and maintain the tape's tension. During fast winding operations, the pinch roller is disengaged and the take-up reel motor produces more torque than the supply motor. The cheapest models use a single motor for all required functions; the motor drives the capstan directly and the supply and take-up reels are loosely coupled to the capstan motor with slipping belts, gears, or clutches. There are also variants with two motors, one motor being used for the capstan and one for driving the reels for playback, rewind, and fast forward.[citation needed]

Limitations

[edit]The storage of an analog signal on tape works well but is not perfect. In particular, the granular nature of the magnetic material adds high-frequency noise to the signal, generally referred to as tape hiss. Also, the magnetic characteristics of tape are not linear. They exhibit a characteristic hysteresis curve, which causes unwanted distortion of the signal. Some of this distortion is overcome by using inaudible high-frequency AC bias when recording. The amount of bias needs careful adjustment for best results as different tape material requires differing amounts of bias. Most recorders have a switch to select this.[c] Additionally, systems such as Dolby noise reduction systems have been devised to ameliorate some noise and distortion problems.[citation needed]

Variations in tape speed cause wow and flutter. Flutter can be reduced by using dual capstans.[citation needed] The higher the flutter the more noise that can be heard causing the quality of the recording to be worse.[42] Higher tape speeds used in professional recorders are prone to cause head bumps, which are fluctuations in low-frequency response.[43]

Tape recorder variety

[edit]

There is a wide variety of tape recorders in existence, from small hand-held devices to large multitrack machines. A machine with built-in speakers and audio power amplification to drive them is usually called a tape recorder or – if it has no record functionality – a tape player, while one that requires external amplification for playback is usually called a tape deck (regardless of whether it can record).[citation needed]

Multitrack technology enabled the development of modern art music and one such artist, Brian Eno, described the tape recorder as "an automatic musical collage device."[44]

Uses

[edit]

Magnetic tape brought about sweeping changes in both radio and the recording industry. Sound could be recorded, erased and re-recorded on the same tape many times, sounds could be duplicated from tape to tape with only minor loss of quality, and recordings could now be very precisely edited by physically cutting the tape and rejoining it. In August 1948, Los Angeles-based Capitol Records became the first recording company to use the new process.[45]

Within a few years of the introduction of the first commercial tape recorder, the Ampex 200 model, launched in 1948, the invention of the first multitrack tape recorder, brought about another technical revolution in the recording industry. Tape made possible the first sound recordings totally created by electronic means, opening the way for the bold sonic experiments of the Musique Concrète school and avant-garde composers like Karlheinz Stockhausen, which in turn led to the innovative pop music studio-as-an-instrument recordings of artists such as Frank Zappa, the Beatles, and the Beach Boys. Philips advertised their reel-to-reel recorders as an audial family album and pushed families to purchase these recorders to capture and relive memories forever. But the use for recording music slowly but steadily rose as the main function for the tape recorder.[46]

Tape enabled the radio industry for the first time to pre-record many sections of program content such as advertising, which formerly had to be presented live, and it also enabled the creation and duplication of complex, high-fidelity, long-duration recordings of entire programs. It also, for the first time, allowed broadcasters, regulators and other interested parties to undertake comprehensive logging of radio broadcasts for legislative and commercial purposes, leading to the growth of the modern media monitoring industry.[citation needed]

Innovations, like multitrack recording and tape echo, enabled radio programs and advertisements to be pre-produced to a level of complexity and sophistication that was previously unattainable and tape also led to significant changes to the pacing of program content, thanks to the introduction of the endless tape cartridge.[citation needed]

While they are primarily used for sound recording, tape machines were also important for data storage before the advent of floppy disks and CDs, and are still used today, although primarily to provide backup.[citation needed]

Tape speeds

[edit]Professional decks will use higher tape speeds, with 15 and 30 inches per second being most common, while lower tape speeds are usually used for smaller recorders and cassette players, in order to save space where fidelity is not as critical as in professional recorders.[42] By providing a range of tape speeds, users can trade-off recording time against recording quality with higher tape speeds providing greater frequency response.[47]

There are many tape speeds in use in all sorts of tape recorders. Speed may be expressed in centimeters per second (cm/s) or in inches per second (in/s).[citation needed]

| cm/s | in/s | Usage |

|---|---|---|

| 1.2 | 15⁄32[48] | Found on some Microcassette pocket dictaphones |

| 2.4 | 15⁄16 | Microcassette standard speed; Cassettes issued by the National Library Service For The Blind And Physically Handicapped |

| 4.75 | 1+7⁄8 | Standard for Cassette tape. Common on portable reel-to-reel machines |

| 9.5 | 3+3⁄4 | Lower speed, common on full-size reel-to-reel and some portable machines |

| 19 | 7+1⁄2 | Common on full-size reel-to-reel machines |

| 38 | 15 | Higher end of prosumer machines, lower end of professional machines |

| 76 | 30 | Highest end of professional reel-to-reel machines |

Inventory

[edit]See also

[edit]- Audio tape specifications – Details of different audio tape formats

- Bootleg recording

- Dictation machine

- Electronic music

- History of sound recording § Magnetic recording – Magnetic tape in the context of the history of sound recording

- Multitrack recording – Advanced usage of sophisticated tape recorders

- Preservation of magnetic audiotape

- Reel-to-reel audio tape recording – Details of using old-style recorders

- Sound follower – For film

- Video tape recorder

- Volta Laboratory and Bureau § Sound recording and phonograph development

Explanatory notes

[edit]- ^ The Allies were aware of the existence of the pre-war Magnetophon recorders, but not of the introduction of high-frequency bias and PVC-backed tape.[27]

- ^ Mullin claims to have been the first to use canned laughter; at the insistence of Crosby's head writer, Bill Morrow, he inserted a segment of raucous laughter from an earlier show into a joke in a later show that hadn't worked well.

- ^ In a cassette recorder, bias settings are selected automatically based on cutouts in the cassette shell.

References

[edit]- ^ a b Newville, Leslie J. Development of the Phonograph at Alexander Graham Bell's Volta Laboratory, United States National Museum Bulletin, United States National Museum and the Museum of History and Technology, Washington, D.C., 1959, No. 218, Paper 5, pp.69–79. Retrieved from ProjectGutenberg.org.

- ^ History of the Cylinder Phonograph, Library of Congress, retrieved 24 February 2024

- ^ The Gramophone, Library of Congress, retrieved 24 February 2024

- ^ US 944608, Goodale, Franklin C., "Sound-reproducing machine", published 28 December 1909

- ^ USPTO. Official Gazette Of The United States Patent Office, United States Patent Office, 1936, Volume 463, pp.537.

- ^ USPTO. United States Patent Office, Patent US2030973 A, "Method of and apparatus for electrically recording and reproducing sound or other vibrations"

- ^ Popular Science. Record Of Voice Now Made On Moving Paper Tape, Popular Science, Bonnier Corporation, February 1934, pp.40, Vol. 124, No. 2, ISSN 0161-7370.

- ^ Onosko, Tim. Wasn't The Future Wonderful?: A View Of Trends And Technology From The 1930s: (article) Book Reads Itself Aloud: After 500 Years, Books Are Given Voice, Dutton, 1979, pp.73, ISBN 0-525-47551-6, ISBN 978-0-525-47551-4. Article attributed to: Popular Mechanics, date of publication unstated, likely c. February 1934.

- ^ Engel, Friedrich Karl, ed. (2006) "Oberlin Smith and the invention of magnetic sound recording: An appreciation on the 150th anniversary of the inventor's birth". Smith's caveat of 4 October 1878 regarding the recording of sound on magnetic media appears on pp. 14–16. Available at: RichardHess.com Archived 21 October 2006 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Smith, Oberlin (1888 September 8) "Some possible forms of phonograph," The Electrical World, 12 (10) : 116–117.

- ^ Poulsen, Valdemar (13 November 1900) [July 8, 1899]. "Method of recording and reproducing sounds or signals". United States Patent and Trademark Office Patent Images. No. 661,619. Archived from the original on 15 January 2019.

- ^ a b Nagra Company. "Magnetic Recording Timeline". ACMI. Archived from the original on 2 March 2004.

- ^ Morton, David (April 1998). "Armour Research Foundation and the Wire Recorder: How Academic Entrepreneurs Fail". Technology and Culture. 39 (2). Society for the History of Technology: 213–244. doi:10.2307/3107045. JSTOR 3107045.

- ^ Porter, Kenneth (January 1944). "Radio News, 'Radio - On a Flying Fortress'" (PDF). www.americanradiohistory.com. p. 21. Archived (PDF) from the original on 25 January 2022. Retrieved 13 February 2019.

- ^ a b "BRUSH DEVELOPMENT CORP". The Encyclopedia of Cleveland History. 29 May 2002.

- ^ Mooney, Mark Jr. "The History of Magnetic Recording." Hi-Fi Tape Recording 5:3 (February 1958), 37. This detailed, illustrated 17-page article is a fundamental source for early history of magnetic (wire/tape) recording: https://worldradiohistory.com/Archive-All-Audio/Archive-Tape-Recording/50s/Tape-Recording-1958-02.pdf Archived 9 March 2021 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Magnetic tape recorder - Kurt Stille, Marconi's Wireless Telegraph Company". Google Arts & Culture. Retrieved 20 June 2020.

- ^ Blattnerphone, retrieved 11 December 2013

- ^ Video Recording Technology: Its Impact on Media and Home Entertainment, Aaron Foisi Nmungwun – Google Books pub. Routledge, Nov. 2012. ISBN 9781136466045

- ^ The BBC Year-Book 1932 p.101, British Broadcasting Corporation, London W.1, retrieved 30 September 2015

- ^ Marconi-Stille recorders, retrieved 11 December 2013

- ^ Stewart Adam (18 October 2012). "The Marconi-Stille magnetic recorder-reproducer". Retrieved 25 December 2022.

- ^ Directly-cut discs, retrieved 11 December 2013

- ^ Optical film, retrieved 11 December 2013),

- ^ Information in this section from 'BBC Engineering 1922-1972' by Edward Pawley, pp178-182; plus some from colleagues who worked in BH in the 1930s.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Fenster, J.M. (Fall 1994). "How Bing Crosby Brought You Audiotape". Invention & Technology. Archived from the original on 4 April 2011.

- ^ Information from BBC Engineering 1922–1972 by Edward Pawley, page 387.

- ^ Bruce-Jones, Henry (11 October 2019). "Worldwide gamma ferric oxide shortage delays cassette tape production". www.factmag.com. Fact. Retrieved 8 April 2020.

- ^ a b c Wilmut, Roger. "Recording of the BBC". Fragments of an informal History of Broadcasting. p. 5. Retrieved 4 June 2025.

- ^ The EMI magnetic tape recorder BTR/1 (PDF) (Report). British Broadcasting Corporation. September 1948. Retrieved 4 June 2025.

- ^ Hughes, David. "Large Green Tape Machines". Old BBC Radio Broadcasting Equipment and Memories. Retrieved 4 June 2025.

- ^ Fleming, Colin (2 July 2018). "Remembering the Beatles' Greatest BBC Session". Rolling Stone. Retrieved 4 June 2025.

- ^ Mastropolo, Frank (6 December 2014). "How a Deep Dive Produced the Beatles' Revealing 'Live at the BBC'". Ultimate Classic Rock. Retrieved 4 June 2025.

- ^ "Stories BBC & EMI". Museum of Magnetic Sound Recording. Retrieved 4 June 2025.

- ^ Web page about digital playout

- ^ Information in this section from 'BBC Engineering 1922-1972' by Edward Pawley, p387ff and 488ff plus personal experience.

- ^ First Sony Walkman introduced

- ^ Recording Enters a New Era, And You Can't Find It on LP

- ^ "A new tape transport system with digital control", Oscar Bonello, Journal of Audio Engineering Society, Vol 31 # 12, December 1983

- ^ "Grabador Magnético profesional controlado por microprocesador", Rev Telegráfica Electrónica, Julio-Agosto de 1982

- ^ Hurtig, B. Multi-Track Recording for Musicians. Alfred Music Publishing. p. 7. ISBN 978-1-4574-2484-7. Retrieved 9 August 2024.

- ^ a b Kuhn, Wolfgang (1953). "Magnetic Tape Recorders". Music Educators Journal. 39 (3): 40. doi:10.2307/3387651. ISSN 0027-4321. JSTOR 3387651. S2CID 144400351.

- ^ Dugan, Dan (October 1982). "Equalizing Tape Recorder Head Bumps".

- ^ Tamm, Eric (1989). Brian Eno : his music and the vertical color of sound. Boston: Faber and Faber. ISBN 0-571-12958-7. OCLC 18870418.

- ^ "The Capitol Story – A Decade of Growth and Success." Billboard, 2 August 1952

- ^ Bijsterveld, Karin; Jacobs, Annelies (2009), Bijsterveld, Karin; van Dijck, José (eds.), "Storing Sound Souvenirs: The Multi-Sited Domestication of the Tape Recorder", Sound Souvenirs, Audio Technologies, Memory and Cultural Practices, Amsterdam University Press, pp. 25–42, ISBN 978-90-8964-132-8, JSTOR j.ctt45kf7f.6, retrieved 16 April 2022

- ^ Reels, R. X. "Ultimate Guide for Reel to Reel Tape Players". RX Reels. Retrieved 11 June 2024.

- ^ "Martel Electronics. Terms commonly used for Tape Recorder. Tape Recorder Speed.". Archived from the original on 1 March 2012. Retrieved 26 April 2008.

This article incorporates text from the United States National Museum Bulletin, a government publication in the public domain.

External links

[edit]- Museum of Magnetic Sound Recording

- A History of Magnetic RecordingBBC/H2G2 [1]

- A Selected History of Magnetic Recording

- Walter Weber's Technical Innovation at the Reichs-Rundfunk-Gesellschaft

- Timeline from U of San Diego's Archive at the Wayback Machine (archived 2010-03-12)

- History of Recording Technology at the Wayback Machine (archived 2004-06-03)

- History of Magnetic Tape at the Wayback Machine (archived 2004-06-03)

- Description of the recording process with diagrams. pg. 2, pg. 3, pg. 4, pg. 5.

- Recording at the BBC – a brief history of various sound recording methods used by the BBC.