Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

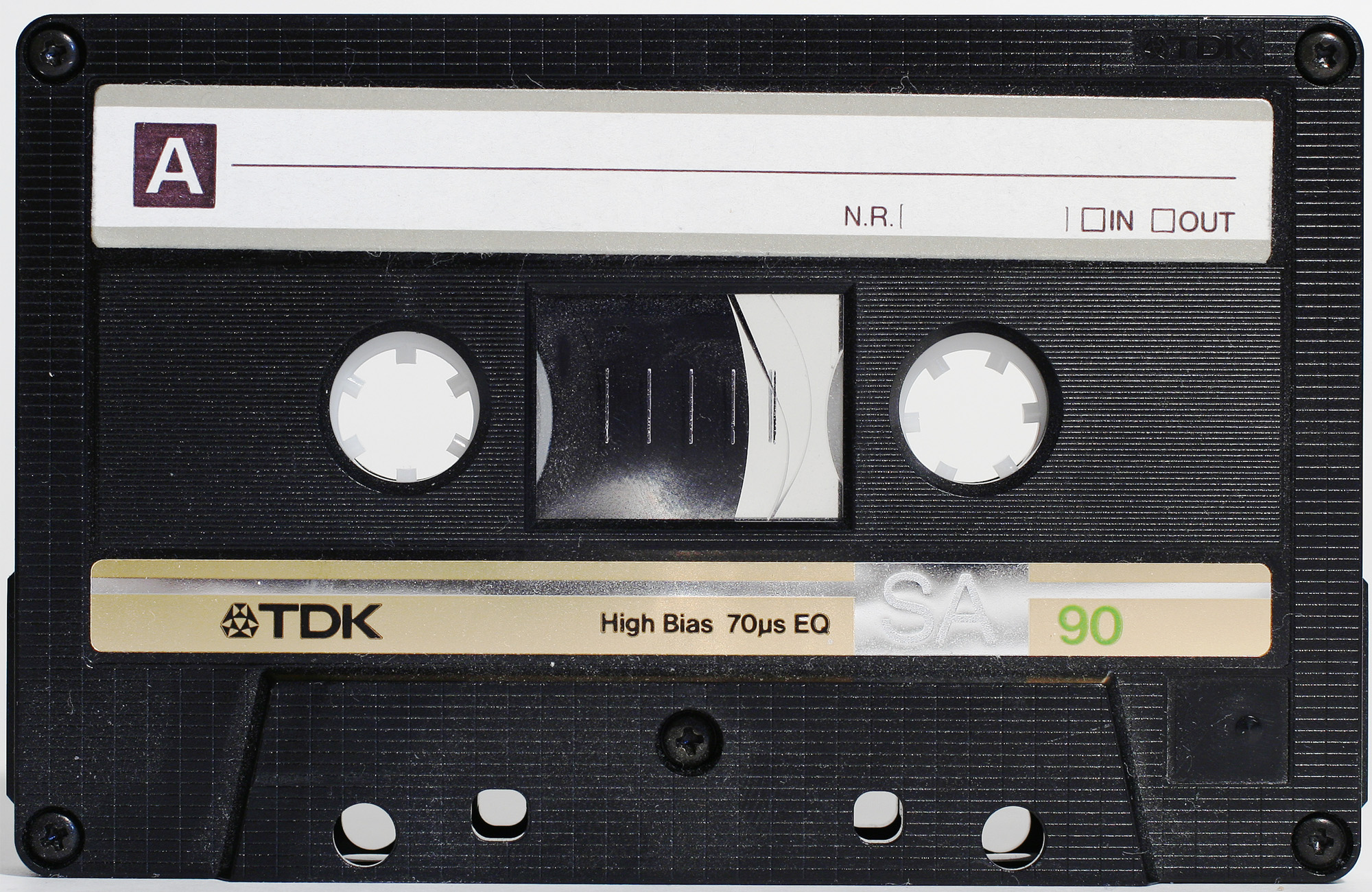

Cassette tape

View on Wikipedia

| |

A TDK SA90 Type II Compact Cassette | |

| Media type | Magnetic tape cassette |

|---|---|

| Encoding | Analog signal, in four tracks |

| Capacity | Most commonly 30, 45, or 60 minutes per side (C60, C90, and C120)[1] |

| Read mechanism | Tape head |

| Write mechanism | Tape head |

| Developed by | Philips |

| Usage | Audio and data storage |

| Extended from | Reel-to-reel audio tape recording |

| Extended to | Digital Compact Cassette |

| Released | August 1963 |

The cassette tape,[2] also called Compact Cassette, audio cassette, or simply tape or cassette, is an analog magnetic tape recording format for audio recording and playback. Invented by Lou Ottens and his team at the Dutch company Philips, the Compact Cassette was introduced in August 1963.[3]

Cassette tapes come in two forms, either containing content as a prerecorded cassette (Musicassette), or as a fully recordable "blank" cassette. Both forms have two sides and are reversible by the user.[4] Although other tape cassette formats have also existed—for example the Microcassette—the generic term cassette tape is normally used to refer to the Compact Cassette because of its ubiquity.[5]

From 1983 to 1991, the cassette tape was the most popular audio format for new music sales in the United States.[6]

Cassette tapes contain two miniature spools, between which the magnetically coated, polyester-type plastic film (magnetic tape) is passed and wound[7]—essentially miniaturizing reel-to-reel audio tape and enclosing it, with its reels, in a small case (cartridge)—hence "cassette".[8] These spools and their attendant parts are held inside a protective plastic shell which is 4 by 2.5 by 0.5 inches (10.2 cm × 6.35 cm × 1.27 cm) at its largest dimensions. The tape itself is commonly referred to as "eighth-inch" tape, supposedly 1⁄8 inch (0.125 in; 3.175 mm) wide, but actually slightly larger, at 0.15 inches (3.81 mm).[9] Two stereo pairs of tracks (four total) or two monaural audio tracks are available on the tape; one stereo pair or one monophonic track is played or recorded when the tape is moving in one direction and the second (pair) when moving in the other direction. This reversal is achieved either by manually flipping the cassette when the tape comes to an end, or by the reversal of tape movement, known as "auto-reverse", when the mechanism detects that the tape has ended.[10]

History

[edit]Precursors

[edit]After the Second World War, magnetic tape recording technology proliferated across the world. In the United States, Ampex, using equipment obtained in Germany as a starting point, began commercial production of reel-to-reel tape recorders. First used by broadcast studios to pre-record radio programs, tape recorders quickly found their way into schools and homes. By 1953, one million U.S. homes had tape machines,[11] and several major record labels were releasing select titles on prerecorded reel-to-reel tapes.

In 1958, following four years of development, RCA introduced the RCA tape cartridge, which enclosed 60 minutes (30 minutes per side) of stereo quarter-inch reel-to-reel tape within a plastic cartridge that could be utilized on a compatible tape recorder/player without having to thread the tape through the machine.[12] This format was not very successful, and RCA discontinued it in 1964.[13]

Development and release

[edit]In the early 1960s, Philips tasked two teams to design a high-quality tape cartridge for home use, using thinner and narrower tape than that used in reel-to-reel tape recorders. A team at its Vienna factory, which had experience with dictation machines, developed the Einloch-Kassette, or single-hole cassette, with Grundig.[14] At the same time, a team in Hasselt led by Lou Ottens developed a two-hole cassette under the name Pocket Recorder.[15][16][17]

Philips selected the two-spool cartridge as a winner and introduced the 2-track 2-direction mono version in Europe on 28 August 1963 at the Berlin Radio Show,[3][18][19][20][21][22][23] and in the United States (under the Norelco brand) in November 1964. The same year, mass production of blank compact cassettes began in Hanover.[18] Philips also offered a machine to play and record the cassettes, the Philips Typ EL 3300. An updated model, Typ EL 3301 was offered in the U.S. in November 1964 as Norelco Carry-Corder 150. The trademark name Compact Cassette came a year later.[citation needed]

Following rejection of the Einloch-Kassette, Grundig developed the DC-International (DC standing for Double Cassette) based on drawings of the Compact Cassette, introducing it in 1965 as companies were competing to establish their format as the worldwide standard.[24] After yielding to pressure from Sony to license the Compact Cassette format to them free of charge, Philips' format achieved market dominance,[25] with the DC-International cassette format being discontinued in 1967, just two years after its introduction.

Philips improved on the Compact Cassette's original design to release a stereo version. By 1966 over 250,000 compact cassette recorders had been sold in the U.S. alone. Japanese manufacturers soon became the leading source of recorders. By 1968, 85 manufacturers had sold over 2.4 million mono and stereo units.[18][26] By the end of the 1960s, the cassette business was worth an estimated $150 million,[18] and by the early 1970s compact cassette machines were outselling other types of tape machines by a large margin.[27]

Popularity of music cassettes

[edit]Prerecorded music cassettes (also known as Music-Cassettes, and later just Musicassettes) were launched in Europe in late 1965. The Mercury Record Company, a US affiliate of Philips, introduced Musicassettes to the US in July 1966. The initial offering consisted of 49 titles.[28]

The compact cassette format was initially designed for dictation and portable use, and the audio quality of early players was not well-suited for music. In 1971, the Advent Corporation introduced their Model 201 tape deck that combined Dolby type B noise reduction and chromium(IV) oxide (CrO2) tape, with a commercial-grade tape transport mechanism supplied by the Wollensak camera division of 3M Corporation. This resulted in the format being taken more seriously for musical use, and started the era of high fidelity cassettes and players.[29]

British record labels began releasing Musicassettes in October 1967, and they exploded as a mass-market medium after the first Walkman, the TPS-L2, went on sale on 1 July 1979, as cassettes provided portability, which vinyl records could not. While portable radios and boom boxes had been around for some time, the Walkman was the first truly personal portable music player, one that not only allowed users to listen to music away from home, but to do so in private. According to the technology news website The Verge, "the world changed" on the day the TPS-L2 was released.[30][31][32] Stereo tape decks and boom boxes became some of the most highly sought-after consumer products of both decades, as the ability of users to take their music with them anywhere with ease[18] led to its popularity around the globe.[18][33]

Like the transistor radio in the 1950s and 1960s, the portable CD player in the 1990s, and the MP3 player in the 2000s, the Walkman defined the portable music market for the decade of the '80s, with cassette sales overtaking those of LPs.[34][35] Total vinyl record sales remained higher well into the 1980s due to greater sales of singles, although cassette singles achieved popularity for a period in the 1990s.[35] Another barrier to cassettes overtaking vinyl in sales was shoplifting; compact cassettes were small enough that a thief could easily place one inside a pocket and walk out of a shop without being noticed. To prevent this, retailers in the US would place cassettes inside oversized "spaghetti box" containers or locked display cases, either of which would significantly inhibit browsing, thus reducing cassette sales.[36]

During the early 1980s some record labels sought to solve this problem by introducing new, larger packages for cassettes which would allow them to be displayed alongside vinyl records and compact discs, or giving them a further market advantage over vinyl by adding bonus tracks.[36] Willem Andriessen wrote that the development in technology allowed "hardware designers to discover and satisfy one of the collective desires of human beings all over the world, independent of region, climate, religion, culture, race, sex, age and education: the desire to enjoy music at any time, at any place, in any desired sound quality and almost at any wanted price".[37] Critic Robert Palmer, writing in The New York Times in 1981, cited the proliferation of personal stereos as well as extra tracks not available on LP as reasons for the surge in popularity of cassettes.[38]

Cassettes' ability to allow users to record content in public also led to a boom in bootleg cassettes made at live shows in the 1980s.[39] The Walkman dominated the decade, selling up to 350 million units. So synonymous did the name "Walkman" become with all portable music players—with a German dictionary at one point defining the term as such without reference to Sony—that the Austrian Supreme Court ruled in 2002 that Sony, which had not sought to have the publisher of that dictionary retract that definition, could not prevent other companies from using that name, as it had now become genericized.[40][41][42] As a result of this, a number of Sony's competitors produced their own version of the Walkman. Others made their own branded tape players, like JVC, Panasonic, Sharp, and Aiwa, the second-largest producer of the devices.[43]

Between 1985, when cassettes overtook vinyl, and 1992, when they were overtaken by CDs[32][failed verification] (introduced in 1983 as a format that offered greater storage capacity and more accurate sound),[44][failed verification] the cassette tape was the most popular format in the United States[32] and the UK. Record labels experimented with innovative packaging designs. A designer during the era explained: "There was so much money in the industry at the time, we could try anything with design."[This quote needs a citation] The introduction of the cassette single, called a cassingle, was also part of this era and featured a music single in Compact Cassette form. Until 2005, cassettes remained the dominant medium for purchasing and listening to music in some developing countries, but compact disc (CD) technology had superseded the Compact Cassette in the vast majority of music markets throughout the world by this time.[45][46]

Cassette culture

[edit]Compact cassettes served as catalysts for social change. Their small size, durability and ease of copying helped bring underground rock and punk music behind the Iron Curtain, creating a foothold for Western culture among the younger generations.[47] Likewise, in Egypt cassettes empowered an unprecedented number of people to create culture, circulate information, and challenge ruling regimes before the internet became publicly accessible.[48]

One of the political uses of cassette tapes was the dissemination of sermons by the exiled Ayatollah Khomeini throughout Iran before the 1979 Iranian Revolution, in which Khomeini urged the overthrow of the regime of the Shah, Mohammad Reza Pahlavi.[50] During the military dictatorship of Chile (1973–1990) a "cassette culture" emerged where blacklisted music or music that was by other reasons not available as records was shared.[51][52][53] Some pirate cassette producers created brands such as Cumbre y Cuatro that have in retrospect received praise for their contributions to popular music.[53] Armed groups such as Manuel Rodríguez Patriotic Front (FPMR) and the Revolutionary Left Movement (MIR) made use of cassettes to spread their messages.[52]

Cassette technology was a booming market for pop music in India, drawing criticism from conservatives while at the same time creating a huge market for legitimate recording companies, as well as pirated tapes.[54] Some sales channels were associated with cassettes: in Spain filling stations often featured a display selling cassettes. While offering also mainstream music these cassettes became associated with genres such as Gipsy rhumba, light music and joke tapes that were common in the 1970s and 1980s.[55]

Decline

[edit]Despite sales of CDs overtaking those of prerecorded cassettes in the early 1990s in the U.S.,[56] the format remained popular for specific applications, such as car audio, personal stereos, boomboxes, telephone answering machines, dictation, field recording, home recording, and mixtapes well into the decade. Cassette players were typically more resistant to shocks than CD players, and their lower fidelity was not considered a serious drawback in mobile use. With the introduction of electronic skip protection it became possible to use portable CD players on the go, and automotive CD players became viable. CD-R drives and media also became affordable for consumers around the same time.[57]

By 1993, annual shipments of CD players had reached 5 million, up 21% from the year before; while cassette player shipments had dropped 7% to approximately 3.4 million.[58] Sales of pre-recorded music cassettes in the US dropped from 442 million in 1990 to 274,000 by 2007.[59] For audiobooks, the final year that cassettes represented more than 50% of total market sales was 2002 when they were replaced by CDs as the dominant media.[60]

The last new car with an available cassette player was a 2014 TagAZ AQUiLA.[61] Four years prior, Sony had stopped the production of personal cassette players.[62] In 2011, the Oxford English Dictionary removed the phrase "cassette player" from its 12th edition Concise version,[63] which prompted some media sources to mistakenly report that the term "cassette tape" was being removed.[64]

In India, music continued to be released on the cassette format due to its low cost until 2009.[65]

21st century

[edit]

Although portable digital recorders are most common today, analog tape remains a desirable option for certain artists and consumers.[30][66] Underground and DIY communities release regularly, and sometimes exclusively, on cassette format, particularly in experimental music circles and to a lesser extent in hardcore punk, death metal, and black metal circles, out of a fondness for the format. Even among major-label stars, the form has at least one devotee: Thurston Moore stated in 2009, "I only listen to cassettes."[67] By 2019, few companies still made cassettes. Among those are National Audio Company, from the US, and Mulann, also known as Recording The Masters, from France.[68][69]

Sony announced the end of cassette Walkman production on 22 October 2010,[70] a result of the emergence of MP3 players such as Apple's iPod.[71] As of 2022, Sony uses the Walkman brand solely for its line of digital media players.[72]

The 2010 Lexus SC430 was the last automobile sold new in North America with a compact cassette player as standard equipment.[73][74]

In 2010, Botswana-based Diamond Studios announced plans[75] for establishing a plant to mass-produce cassettes in a bid to combat piracy. It opened in 2011.[76]

In South Korea, the early English education boom for toddlers encourages a continuous demand for English language cassettes, as of 2011,[update] due to the affordable cost.[77]

National Audio Company in Missouri, the largest of the few remaining manufacturers of audio cassettes in the US, oversaw the mass production of the "Awesome Mix #1" cassette from the film Guardians of the Galaxy in 2014.[78] They reported that they had produced more than 10 million tapes in 2014 and that sales were up 20 percent the following year, their best year since they opened in 1969.[79] In 2016, cassette sales in the United States rose by 74% to 129,000.[80] In 2018, following several years of shortage, National Audio Company began producing their own magnetic tape, becoming the world's first known manufacturer of an all-new tape stock.[81] Mulann, a company which acquired Pyral/RMGI in 2015 and originates from BASF, also started production of its new cassette tape stock in 2018, basing on reel tape formula.[82]

In Japan and South Korea, the pop acts Seiko Matsuda,[83] SHINee,[84] and NCT 127 released their material on limited-run cassettes.[85] In Reiwa era Japan, the revived popularity of cassette tapes is an example of Showa retro.[86][87] As of 2021, Maxell was selling 8 million cassette tapes per year in Japan.[88]

In the mid-to-late 2010s, cassette sales saw a modest resurgence concurrent with the vinyl revival. As early as 2015, the retail chain Urban Outfitters, which had long sold LPs, started selling new pre-recorded cassettes (both new and old albums), blank cassettes, and players.[89] In 2016, cassette sales increased,[90] a trend that continued in 2017[91] and 2018.[92] In the UK, sales of cassette tapes in 2021 reached its highest number since 2003.[93]

Cassettes are favored by some artists and listeners, including those of older genres of music such as dansband,[94] as well as independent[30] and underground artists,[95] some of whom were releasing new music on tape by the 2020s, including Britney Spears and Busta Rhymes.[96] Reasons cited for this include tradition, low cost,[30] the DIY ease of use,[97] and a nostalgic fondness for how the format's imperfections lend greater vibrancy to low-fi, experimental music, despite the lack of the "full-bodied richness" of vinyl.[30][95][97]

Tape types

[edit]

Cassette tapes are made of a polyester-type plastic film with a magnetic coating. The original magnetic material was based on gamma ferric oxide (Fe2O3). c. 1970, 3M Company developed a cobalt volume-doping process combined with a double-coating technique to enhance overall tape output levels. This product was marketed as "High Energy" under its Scotch brand of recording tapes.[98] Inexpensive cassettes commonly are labeled "low-noise", but typically are not optimized for high frequency response. For this reason, some low-grade IEC Type I tapes have been marketed specifically as better suited for data storage than for sound recording.[citation needed]

In 1968,[99] DuPont, the inventor of a chromium dioxide (CrO2) manufacturing process, began commercialization of CrO2 media. The first CrO2 cassette was introduced in 1970 by Advent,[100] and later strongly backed by BASF, the inventor and longtime manufacturer of magnetic recording tape.[101] Next, coatings using magnetite (Fe3O4) such as TDK's Audua were produced in an attempt to approach or exceed the sound quality of vinyl records. Cobalt-adsorbed iron oxide (Avilyn) was introduced by TDK in 1974 and proved very successful. "Type IV" tapes using pure metal particles (as opposed to oxide formulations) were introduced in 1979 by 3M under the trade name Metafine. The tape coating on most cassettes sold as of 2024 are either "normal" or "chrome" consists of ferric oxide and cobalt mixed in varying ratios (and using various processes); there are very few cassettes on the market that use a pure (CrO2) coating.[34]

Simple voice recorders and earlier cassette decks are designed to work with standard ferric formulations. Newer tape decks usually are built with switches and later detectors for the different bias and equalization requirements for higher grade tapes. The most common are iron oxide tapes (as defined by the IEC 60094 standard).[10]

Notches on top of the cassette shell indicate the type of tape. Type I cassettes have only write-protect notches, Type II have an additional pair next to the write protection ones, and Type IV (metal) have a third set near the middle of the top of the cassette shell. These allow later cassette decks to detect the tape type automatically and select the proper bias and equalization.[102]

Features

[edit]

The cassette was the next step following reel-to-reel audio tape recording, although, because of the limitations of the cassette's size and speed, it initially compared poorly in quality. Unlike the 4-track stereo open-reel format, the two stereo tracks of each side lie adjacent to each other, rather than being interleaved with the tracks of the other side. This permitted monaural cassette players to play stereo recordings "summed" as mono tracks and permitted stereo players to play mono recordings through both speakers. The tape is 0.15 in (3.81 mm) wide, with each mono track 1.5 millimetres (0.059 in) wide, plus an unrecorded guard band between each track. In stereo, each track is further divided into a left and a right channel of 0.6 mm (0.024 in) each, with a gap of 0.3 mm (0.012 in).[103] The tape moves past the playback head at 1+7⁄8 inches per second (4.76 cm/s), the speed being a continuation of the increasingly slower speed series in open-reel machines operating at 30 inches per second (76.20 cm/s), 15 inches per second (38.10 cm/s), 7+1⁄2 inches per second (19.05 cm/s) or 3+3⁄4 inches per second (9.53 cm/s).[9] For comparison, the typical open-reel 1⁄4-inch (6.35 mm) 4-track consumer format used tape that is 0.248 inches (6.3 mm) wide, each track .043 in (1.1 mm) wide, and running at either twice or four times the speed of a cassette.[citation needed]

Very simple cassette recorders for dictation purposes did not tightly control tape speed and relied on playback on a similar device to maintain intelligible recordings. For accurate reproduction of music, a tape transport incorporating a capstan and pinch roller system was used, to ensure tape passed over the record/playback heads at a constant speed.

Locating write-protect notches

[edit]If the cassette is held with one of the labels facing the user and the tape opening at the bottom, the write-protect notch for the corresponding side is at the top-left.

Tape length

[edit]

Tape length usually is measured in minutes of total playing time. Many of the varieties of blank tape were C60 (30 minutes per side), C90 (45 minutes per side) and C120 (60 minutes per side).[1] Maxell makes 150-minute cassettes (UR-150) - 75 minutes per side. The C46 and C60 lengths typically are 15 to 16 micrometers (0.59 to 0.63 mils) thick, but C90s are 10 to 11 μm (0.39 to 0.43 mils)[104] and (the less common) C120s are just 6 μm (0.24 mils) thick,[105] rendering them more susceptible to stretching or breakage. Even C180 tapes were available at one point.[106]

Other lengths are (or were) also available from some vendors, including C10, C12 and C15 (useful for saving data from early home computers and in telephone answering machines), C30, C40, C50, C54, C64, C70, C74, C80, C84, C94, C100, C105, C110, and C150. As late as 2010, Thomann still offered C10, C20, C30 and C40 IEC Type II tape cassettes for use with 4- and 8-track portastudios.[107]

Track width

[edit]The full tape width is 3.8 mm. For mono recording the track width is 1.5 mm. In stereo mode each channel has width of 0.6 mm with a 0.3 mm separation to avoid crosstalk.[108]

Head gap

[edit]The head-gap width[clarification needed] is 2 μm[according to whom?] which gives a theoretical maximum frequency[citation needed] of about 12 kHz (at the standard speed of 1 7/8 ips or 4.76 cm/s). A narrower gap would give a higher frequency limit but also weaker magnetization.[108]

Cassette tape adapter

[edit]Cassette tape adapters allow external audio sources to be played back from any tape player, but were typically used for car audio systems. An attached audio cable with a phone connector converts the electrical signals to be read by the tape head, while mechanical gears simulate reel to reel movement without actual tapes when driven by the player mechanism.[109]

Optional mechanical elements

[edit]

In order to wind up the tape more reliably, the former BASF (from 1998 EMTEC) patented the Special Mechanism or Security Mechanism advertised with the abbreviation SM in the early 1970s, which was temporarily used under license by Agfa. This feature each includes a rail to guide the tape to the spool and prevent an uneven roll from forming.[110]

Flaws

[edit]Magnetic tape is not an ideal medium for long-term archival storage, as it begins to degrade after 10 – 20 years.[111]

A common mechanical problem occurs when a defective player or resistance in the tape path causes insufficient tension on the take-up spool. This would cause the magnetic tape to be fed out through the bottom of the cassette and become tangled in the mechanism of the player. In these cases, the player was said to have "eaten" or "chewed" the tape, often destroying the playability of the cassette.

Cassette recorders

[edit]

The first cassette machines (e.g. the Philips EL 3300, introduced in August 1963[22][112])

One innovation was the front-loading arrangement. Pioneer's angled cassette bay and the exposed bays of some Sansui models eventually were standardized as a front-loading door into which a cassette would be loaded. Later models would adopt electronic buttons, and replace conventional meters (which could be driven over full scale when overloaded, a condition called "pegging the needle" or simply "pegging") with electronic LED or vacuum fluorescent displays, with level controls typically being controlled by either rotary controls or side-by-side sliders.

Applications for car stereos varied widely. Auto manufacturers in the US typically would fit a cassette slot into their standard large radio faceplates. Europe and Asia would standardize on DIN and double DIN sized faceplates. In the 1980s, a high-end installation would have a Dolby AM/FM cassette deck, and they rendered the 8-track player obsolete in car installations because of space, performance, and audio quality. In the 1990s and 2000s, as the cost of building CD players declined, many manufacturers offered a CD player. The CD player eventually supplanted the cassette deck as standard equipment, but some cars, especially those targeted at older drivers, were offered with the option of a cassette player, either by itself or sometimes in combination with a CD slot. Most new cars can still accommodate aftermarket cassette players, and the auxiliary jack advertised for MP3 players can be used also with portable cassette players, but 2011 was the first model year for which no American manufacturer offered factory-installed cassette players.[113]

Applications

[edit]Audio

[edit]

The Compact Cassette originally was intended for use in dictation machines.[3] In this capacity, some later-model cassette-based dictation machines could also run the tape at half speed (15⁄16 inch per second or 2.38 centimetres per second) as playback quality was not critical. The cassette soon became a medium for distributing prerecorded music—initially through the Philips Record Company (and subsidiary labels Mercury and Philips in the US). As of 2009, one still found cassettes used for a variety of purposes, such as journalism, oral history, meeting and interview transcripts, audio books, and so on. Police are still big buyers of cassette tapes, as some lawyers "don't trust digital technology for interviews".[114] However, they are starting to give way to Compact Discs and more "compact" digital storage media. Prerecorded cassettes were also employed as a way of providing chemotherapy information to recently diagnosed cancer patients as studies found anxiety and fear often gets in the way of the information processing.[115]

The cassette quickly found use in the commercial music industry. One artifact found on some commercially produced music cassettes was a sequence of test tones, called SDR (Super Dynamic Range, also called XDR, or eXtended Dynamic Range) soundburst tones, at the beginning and end of the tape, heard in order of low frequency to high. These were used during SDR/XDR's duplication process to gauge the quality of the tape medium. Many consumers objected to these tones since they were not part of the recorded music.[116]

Leveraging high-speed duplication machines manufactured by companies such as Telex, Otari, and Sony, cassettes were widely used by the Christian faith community for sermon duplication during the 1970s-1990s. One ministry claims a quantity and distribution of "almost 9 million cassettes in 42 languages"[117]. Duplication was obsoleted during the 1980s-1990s when Compact Disc duplication and compressed digital audio files were popularized.

Multitrack recording

[edit]Multitrack recorders utilizing the compact cassette were introduced beginning in 1979 with the TEAC 144 Portastudio. In the simplest configuration, rather than playing a pair of stereo channels of each side of the cassette, the typical portastudio used a four-track tape head assembly to access four tracks on the cassette at once (with the tape playing in one direction). Each track could be recorded to, erased, or played back individually, allowing musicians to overdub themselves and create simple multitrack recordings easily, which could then be mixed down to a finished stereo version on an external machine. To increase audio quality in these recorders, the tape speed sometimes was doubled to 3+3⁄4 inches per second (9.53 cm/s), in comparison to the standard 1+7⁄8 inches per second (4.76 cm/s); additionally, dbx, Dolby B or Dolby C noise reduction provided compansion (compression of the signal during recording with equal and opposite expansion of the signal during playback), which yields increased dynamic range by lowering the noise level and increasing the maximum signal level before distortion occurs. Multi-track cassette recorders with built-in mixer and signal routing features ranged from easy-to-use beginner units up to professional-level recording systems.[118] Cassette-based multitrack recorders are credited with launching the home recording revolution.[119][120]

Home dubbing

[edit]

Most cassettes were sold blank, and used for recording (dubbing) the owner's records (as backup, to play in the car, or to make mixtape compilations), their friends' records, or music from the radio. This practice was condemned by the music industry with such alarmist slogans as "Home Taping Is Killing Music". However, many claimed that the medium was ideal for spreading new music and would increase sales, and strongly defended their right to copy at least their own records onto tape. For a limited time in the early 1980s Island Records sold chromium dioxide "One Plus One"[121]

Various legal cases arose surrounding the dubbing of cassettes. In the UK, in the case of CBS Songs v. Amstrad (1988), the House of Lords found in favor of Amstrad that producing equipment that facilitated the dubbing of cassettes, in this case a high-speed twin cassette deck that allowed one cassette to be copied directly onto another, did not constitute copyright infringement by the manufacturer.[122] In a similar case, a shop owner who rented cassettes and sold blank tapes was not liable for copyright infringement even though it was clear that his customers likely were dubbing them at home.[123] In both cases, the courts held that manufacturers and retailers could not be held accountable for the actions of consumers.[124]

As an alternative to home dubbing, in the late 1980s, the Personics company installed booths in record stores across America that allowed customers to make personalized mixtapes from a digitally encoded back-catalogue with customised printed covers.[125]

Data recording

[edit]

Floppy disk storage had become the standard data storage medium in the United States by the mid-1980s; for example, by 1983 the majority of software sold by Atari Program Exchange was on floppy. Cassette remained more popular for 8-bit computers such as the Commodore 64, ZX Spectrum, MSX, and Amstrad CPC 464 in many countries such as the United Kingdom[126][127] (where 8-bit software was mostly sold on cassette until that market disappeared altogether in the early 1990s). Reliability of cassettes for data storage is inconsistent, with many users recalling repeated attempts to load video games;[128] the Commodore Datasette used very reliable, but slow, digital encoding.[129] In some countries, including the United Kingdom, Poland, Hungary, and the Netherlands, cassette data storage was so popular that some radio stations would broadcast computer programs that listeners could record onto cassette and then load into their computer.[130][131] See BASICODE.

The cassette was adapted into what is called a streamer cassette (also known as a "D/CAS" cassette), a version dedicated solely for data storage, and used chiefly for hard disk backups and other types of data. Streamer cassettes look almost exactly the same as a standard cassette, with the exception of having a notch about one quarter-inch wide and deep situated slightly off-center at the top edge of the cassette. Streamer cassettes also have a re-usable write-protect tab on only one side of the top edge of the cassette, with the other side of the top edge having either only an open rectangular hole, or no hole at all. This is due to the entire one-eighth inch width of the tape loaded inside being used by a streamer cassette drive for the writing and reading of data, hence only one side of the cassette being used. Streamer cassettes can hold anywhere from 250 kilobytes to 600 megabytes of data.[132]

Rivals and successors

[edit]

Technical development of the cassette effectively ceased when digital recordable media, such as DAT and MiniDisc, were introduced in the late 1980s and early-to-mid 1990s, with Dolby S recorders marking the peak of Compact Cassette technology. Anticipating the switch from analog to digital format, major companies, such as Sony, shifted their focus to new media.[133] In 1992, Philips introduced the Digital Compact Cassette (DCC), a DAT-like tape in almost the same shell as a Compact Cassette. It was aimed primarily at the consumer market. A DCC deck could play back both types of cassettes. Unlike DAT, which was accepted in professional usage because it could record without lossy compression effects, DCC failed in home, mobile and professional environments, and was discontinued in 1996.[134]

The microcassette largely supplanted the full-sized cassette in situations where voice-level fidelity is all that is required, such as in dictation machines and answering machines. Microcassettes have in turn given way to digital recorders of various descriptions.[135] Since the rise of cheap CD-R discs, and flash memory-based digital audio players, the phenomenon of "home taping" has effectively switched to recording to a Compact Disc or downloading from commercial or music-sharing websites.[136]

Because of consumer demand, the cassette has remained influential on design, more than a decade after its decline as a media mainstay. As the Compact Disc grew in popularity, cassette-shaped audio adapters were developed to provide an economical and clear way to obtain CD functionality in vehicles equipped with cassette decks but no CD player. A portable CD player would have its analog line-out connected to the adapter, which in turn fed the signal to the head of the cassette deck. These adapters continue to function with MP3 players and smartphones, and generally are more reliable than the FM transmitters that must be used to adapt CD players and digital audio players to car stereo systems. Digital audio players shaped as cassettes have also become available, which can be inserted into any cassette player and communicate with the head as if they were normal cassettes.[137][138]

See also

[edit]Further reading

[edit]- Marc Masters. 2023. High Bias: The Distorted History of the Cassette Tape. University of North Carolina Press.

References

[edit]- ^ a b "Museum Of Obsolete Media". 19 November 2015. Archived from the original on 3 May 2016. Retrieved 29 April 2016.

- ^ Mark Pernice (23 December 2015). "Opinion: Our Misplaced Nostalgia for Cassette Tapes". New York Times. Retrieved 17 June 2024.

- ^ a b c Dormon, Bob (30 August 2013). "Are You for Reel? How the Compact Cassette Struck a Chord for Millions". The Register. Archived from the original on 2 August 2020. Retrieved 6 August 2022.

- ^ "Learn about Tabs-In or Tabs-Out Shells and Leaders". nationalaudiocompany.com. Archived from the original on 9 August 2017. Retrieved 9 August 2017.

- ^ "How to Identify Your Audio Cassette Tape Formats". digitalcopycat.com. Archived from the original on 13 September 2022. Retrieved 13 September 2022.

- ^ "U.S. Music Revenue Database". RIAA. Retrieved 7 June 2025.

- ^ Brian, Marshall (April 2000). "How Tape Recorders Work". HowStuffWorks. Archived from the original on 8 October 2015. Retrieved 10 October 2015.

- ^ "Car Cartridges Come Home" Archived 11 November 2023 at the Wayback Machine, pp.18-22, HiFi / Stereo Review's Tape Recorder Annual 1968, retrieved 22 May 2023. (Detailed diagram of a Fidelipac cartridge on p.20, with comparison to Lear Jet 8-track cartridge and Phillips cassette diagrams on p.21; extensive expert discussion of cassette, and comparisons to competitors, on pp.21-22.)

- ^ a b "D NORMAL-BIAS AUDIO TAPES" (PDF) (spec sheet). TDK. Archived from the original (PDF) on 20 June 2007. Retrieved 4 April 2019.

- ^ a b "Part 7: Cassette for commercial tape records and domestic use". International standard IEC 60094-7: Magnetic tape sound recording and reproducing systems. International Electrotechnical Commission, Geneva.

- ^ "Brew Disk-To-Tape Revolution". Variety. 16 September 1953. p. 1. Retrieved 6 October 2019.

- ^ "RCA Victor Announces Major Break-Through in Recorded Sound". Museum of Magnetic Sound Recording. Retrieved 19 December 2024.

- ^ Cook, Diana. "RCA Cartridges: 1958 - 1964". blog.dianaschnuth.com. Archived from the original on 2 October 2018. Retrieved 19 December 2024.

- ^ Radio Elektronik Schau (in German). Vol. 41. 1965.

- ^ Rothman, Lily. "Rewound: On its 50th birthday, the cassette tape is still rolling". Time. Archived from the original on 2 August 2013. Retrieved 6 August 2013.

- ^ "Gouden jubileum muziekcassette". NOS. 30 August 2013. Archived from the original on 31 December 2013. Retrieved 30 December 2013.

- ^ "Compact Cassette supremo Lou Ottens talks to El Reg". 2 September 2013. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 9 April 2020.

- ^ a b c d e f Millard, Andre (2013). "Cassette Tape". St. James Encyclopedia of Popular Culture (2.1 ed.). p. 529.

- ^ Morton, David (2004). Sound recording: the life story of a technology. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 161.

- ^ Sheperd, John (2003). Continuum Encyclopedia of Popular Music of the World. Continuum International Publishing Group. p. 506.

- ^ "Cassette Rampage Forecast". Billboard. Vol. 79, no. 44. Nielsen Business Media, Inc. 4 November 1967. pp. 1, 72. ISSN 0006-2510.

- ^ a b "European Mfrs. Bid for Market Share". Billboard. Vol. 79, no. 14. Nielsen Business Media, Inc. 8 April 1967. p. 18. ISSN 0006-2510.

- ^ Drees, Jan; Vorbau, Christian (23 May 2011). Kassettendeck: Soundtrack einer Generation. Klappenbroschur. ISBN 978-3821866147.

- ^ "Grundig C 100 and the early history of the Compact Cassette". 7 March 2016. Archived from the original on 24 October 2021. Retrieved 14 March 2021.

- ^ Nathan, John (1999). Sony: the Private Life. Houghton Mifflin. p. 129. ISBN 978-0618126941. Retrieved 8 November 2015.

- ^ Braun, Hans-Joachim (2002). Music and technology in the twentieth century. JHU Press. p. 161.

- ^ The Dolby stretcher — new boon for tape (PDF). Tape Recording ##11-12, 1970. p. 11. Archived (PDF) from the original on 20 May 2024. Retrieved 10 January 2021.

- ^ "Mercury Issues 49 'Cassettes'". Billboard. Vol. 78, no. 29. Nielsen Business Media, Inc. 16 July 1966. p. 69. ISSN 0006-2510.

- ^ Marvin Camras, ed. (1985). Magnetic Tape Recording. Van Nostrand Reinhold. ISBN 978-0-442-21774-7.

- ^ a b c d e Lynskey, Dorian (29 March 2010). "Return of the audio cassette". The Guardian. Retrieved 14 August 2023.

- ^ "40 years ago, the Sony Walkman changed how we listen to music". The Verge. July 2019. Archived from the original on 13 July 2019. Retrieved 14 August 2023.

- ^ a b c "The first Sony Walkman goes on sale". History.com. 13 November 2009. Archived from the original on 12 August 2023. Retrieved 14 August 2023.

- ^ Hoogendoorn, A (1994). "Digital Compact Cassette". Proceedings of the IEEE. 82 (10): 1479–1489. doi:10.1109/5.326405.

- ^ a b Eric D. Daniel; C. Dennis Mee; Mark H. Clark (1999). Magnetic Recording: The First 100 Years. The Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers. ISBN 978-0-7803-4709-0.

- ^ a b Paul du Gay; Stuart Hall; Linda Janes; Hugh Mackay; Keith Negus (1997). Doing Cultural Studies: The Story of the Sony Walkman. Sage Publications Ltd. ISBN 978-0-7619-5402-6.

- ^ a b Gans, David (June 1983). "Packaging Innovations Raise Cassettes' In-store Profile". Record. 2 (8): 20.

- ^ Andriessen, Willem (1999). ""THE WINNER": Compact Cassette. A Commercial and Technological Look Back at the Greatest Success Story in the History of Audio Up to Now". Journal of Magnetism and Magnetic Materials. 193 (1–3): 12. doi:10.1016/s0304-8853(98)00502-2.

- ^ Palmer, Robert (29 July 1981). "The Pop Life; Cassettes Now Have Material Not Available On Disks". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 30 April 2021. Retrieved 27 April 2021.

- ^ "Total rewind: 10 key moments in the life of the cassette". The Guardian. 30 August 2013. Archived from the original on 14 August 2024. Retrieved 14 August 2023.

- ^ "As Apple kills off the iPod ... here are 5 other pieces of beloved tech we've said goodbye to in the past 20 years". We Forum. 16 August 2017. Archived from the original on 12 August 2023. Retrieved 14 August 2023.

- ^ "'Walkman' has become generic, rules Supreme Court". World Trademark Review. Archived from the original on 12 August 2023. Retrieved 14 August 2023.

- ^ "Sony loses Walkman trade mark as too generic". Pinsent Masons. 5 June 2002. Archived from the original on 12 August 2023. Retrieved 12 August 2023.

- ^ "Rewind! A guide to the best portable cassette players". The Vinyl Factory. 24 March 2017. Archived from the original on 12 August 2023. Retrieved 14 August 2023.

- ^ "In a digital age, vinyl's making a comeback". Los Angeles Times. 26 April 2009. Archived from the original on 12 August 2023. Retrieved 14 August 2023.

- ^ "Not long left for cassette tapes". BBC. 17 June 2005. Archived from the original on 29 January 2021. Retrieved 13 September 2006.

- ^ Jude Rogers (30 August 2013). "Total rewind: 10 key moments in the life of the cassette". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 14 August 2024. Retrieved 17 March 2014.

- ^ Robin James (1992). Cassette Mythos. Brooklyn, NY: Autonomedia. ISBN 978-0-936756-69-1.

- ^ Simon, Andrew (2022). Media of the Masses: Cassette Culture in Modern Egypt. Stanford: Stanford University Press. ISBN 978-1-5036-2943-1. Archived from the original on 16 May 2024. Retrieved 16 August 2022.

- ^ Media of the Masses: Cassette Culture in Modern Egypt. Stanford University Press. 2022. ISBN 9781503629431. Archived from the original on 16 May 2024. Retrieved 16 August 2022.

- ^ S. Alexander Reed (2013). Assimilate: A Critical History of Industrial Music. Oxford University Press. p. 113. ISBN 978-0199832606.

- ^ Jordán González, Laura (2019). "Chile: Modern and Contemporary Performance Practice". In Sturman, Janet (ed.). The SAGE International Encyclopedia of Music and Culture. SAGE Publications. pp. 509–511. ISBN 978-1-4833-1775-5.

- ^ a b Jordán, Laura (2009). "Música y clandestinidad en dictadura: la represión, la circulación de músicas de resistencia y el casete clandestino" [Music and "clandestinidad" During the Time of the Chilean Dictatorship: Repression and the Circulation of Music of Resistance and Clandestine Cassettes]. Revista Musical Chilena (in Spanish). 63 (Julio–Diciembre): 212. doi:10.4067/S0716-27902009000200006. Archived from the original on 18 April 2023. Retrieved 8 June 2020.

- ^ a b Montoya Arias, Luis Omar; Díaz Güemez, Marco Aurelio (12 September 2017). "Etnografía de la música mexicana en Chile: Estudio de caso". Revista Electrónica de Divulgación de la Investigación (in Spanish). 14: 1–20.

- ^ Peter Manuel (1993). Cassette Culture: Popular Music and Technology in North India. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0-226-50401-8.

- ^ Arenas, Guillermo (16 August 2019). "Las cintas de casete pasan de la gasolinera a la Biblioteca Nacional". El País (in Spanish). Archived from the original on 21 May 2020. Retrieved 23 May 2020.

- ^ "U.S. Sales Database". RIAA. Archived from the original on 10 October 2021. Retrieved 19 October 2022.

- ^ "1995: Consumer CD-R Drive Priced Below $1000". Computer History Museum. Archived from the original on 21 March 2022. Retrieved 23 January 2022.

- ^ "Record and prerecorded tape stores". Gale Encyclopedia of American Industries. 2005. Archived from the original on 26 July 2008. Retrieved 20 September 2006.

- ^ "Tape Echo: Specialty labels keep cassettes alive". Billboard. 11 October 2008. Archived from the original on 25 February 2009.

- ^ Audio Publishers Association Fact Sheet Archived 26 October 2010 at the Wayback Machine (also includes some historical perspective in the 1950s by Marianne Roney)

- ^ "Tagaz Aquila". Wroom.ru (in Russian). Archived from the original on 17 January 2021. Retrieved 26 January 2021.

- ^ "Sony kills the cassette Walkman on the iPod's birthday". 23 October 2010. Archived from the original on 9 November 2020. Retrieved 19 October 2020.

- ^ Shea, Ammon (10 November 2011). "Reports of the death of the cassette tape are greatly exaggerated". Oxford English Dictionary. Archived from the original on 12 May 2015. Retrieved 28 January 2015.

- ^ Moye, David (22 August 2011). "Oxford Dictionary Removes 'Cassette Tape,' Gets Sound Lashing From Audiophiles". Huffington Post. Archived from the original on 6 March 2018. Retrieved 26 September 2011.

- ^ Kohli-Khandekar, Vanita (2013). The Indian Media Business (4 ed.). New Delhi: Sage India. pp. 184–90. ISBN 9788132118015. Retrieved 26 July 2022 – via Google Books.

- ^ Segal, Dave (9 March 2016). "Baby, I'm for Reel: Unspooling the Affordable, Accessible Microeconomy of the Cassette Revival". The Stranger. Archived from the original on 10 March 2016. Retrieved 11 March 2016.

- ^ "Articles: This Is Not a Mixtape". Pitchfork. 22 February 2010. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 20 August 2010.

- ^ "French firm opens factory making first cassettes since 1990s after artists like Taylor Swift go retro". 22 March 2019. Archived from the original on 31 December 2021. Retrieved 22 November 2021.

- ^ "National Audio Company now has a cassette-making competitor. They're in France". Archived from the original on 28 November 2023. Retrieved 9 April 2020.

- ^ "End Of An Era: Sony Stops Manufacturing Cassette Walkmans". Tech Crunch. 22 October 2010. Archived from the original on 12 August 2023. Retrieved 14 August 2023.

- ^ "Original Walkman is RiP (replaced by iPod)". 26 October 2010. Archived from the original on 12 August 2023. Retrieved 14 August 2023.

- ^ "Do You Still Love the Walkman?". The New York Times. 10 March 2022. Archived from the original on 12 August 2023. Retrieved 14 August 2023.

- ^ https://www.hagerty.com/media/maintenance-and-tech/how-lexus-and-mercury-became-the-last-brands-to-offer-cassette-decks-in-cars/

- ^ Steuer, Eric (July 2011). "Cassettes Return for an Encore". Wired. Retrieved 7 July 2011.

- ^ Butaumocho, Ruth (19 April 2010). "Zimbabwe: Diamond Studios to Commission Cassette Plant". Archived from the original on 20 October 2012. Retrieved 1 January 2017 – via AllAfrica.

- ^ Curnow, Robyn (7 June 2011). "Pause and Rewind: Zimbabwe's Audio Cassette Boom". CNN. Archived from the original on 12 July 2011. Retrieved 13 July 2011.

- ^ Choi (최), Yeon-jin (연진) (31 May 2011). 멸종 중인 카세트, 한국선 '장수 만세. Hankook Ilbo (in Korean). Archived from the original on 14 August 2011. Retrieved 13 July 2011.

- ^ "Meet The Owner Of America's Last Awesome Cassette Tape Factory". Slant. Archived from the original on 19 April 2016. Retrieved 4 June 2017.

- ^ Jeniece Pettitt (1 September 2015). "This Company Is Still Making Audio Cassettes and Sales Are Better Than Ever". Bloomberg.com. Archived from the original on 7 September 2015. Retrieved 9 September 2015.

- ^ "U.S. Cassette Album Sales Increased by 74% in 2016, Led by 'Guardians' Soundtrack". Billboard. 21 January 2017.

- ^ "The world was running out of cassette tape. Now it's being made in Springfield". Springfield News-Leader. 7 January 2018. Archived from the original on 4 August 2019. Retrieved 24 April 2018.

- ^ "Audio cassettes are produced again!". Mulann S.A. 11 October 2018. Archived from the original on 27 July 2020. Retrieved 6 May 2020.

- ^ "Eien no Motto Hate Made / Wakusei ni Naritai [Cassette Tape] [Limited Edition / Type C]". CDJapan., CD Japan. Retrieved 13 June 2018

- ^ "SHINee Vol. 5 - 1 of 1 (Cassette Tape Limited Edition)"., YesAsia. Retrieved 13 June 2018

- ^ "【カセットテープ】 Chain [スマプラ付]<初回生産限定盤>]". Archived from the original on 5 June 2019. Retrieved 13 June 2018., Tower Records Japan. Retrieved 13 June 2018

- ^ 昭和レトロはどこへ行く――令和の若者にウケるわけ. Chūō Kōron. 10 May 2024.

- ^ カセットテープ再ブーム時代に「カセットテープ型2.5インチドライブケース」を衝動買い. ASCII.14 April 2022.

- ^ Cassette Tapes Are Making a Comeback in Japan. Vice. 10 February 2021.

- ^ "Cassettes". Archived from the original on 27 November 2015. Retrieved 30 July 2016.

- ^ "Cassette sales increased by 74% in 2016". 23 January 2017. The Vinyl Factory. Retrieved 26 October 2018

- ^ "Cassette sales grew 35% in 2017". 5 January 2018. The Vinyl Factory. Retrieved 26 October 2018

- ^ "UK cassette sales grew by 90% in first half of 2018". 26 July 2018. The Vinyl Factory. Retrieved 26 October 2018

- ^ "Let's get physical: new BPI report shows vinyl & cassettes sales surge, decline of the CD slows". MusicWeek.com. Retrieved 14 September 2022.

- ^ "Vad händer med dansbandsutgivningen när Bert säljer?". Archived from the original on 20 August 2010. Retrieved 14 August 2023.

- ^ a b "This Is Not a Mixtape". Pitchfork. 22 February 2010. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 14 August 2023.

- ^ "Popular/Major Releases on Cassette [2021 NEW]". Discogs. Retrieved 14 August 2023.

- ^ a b "Baby, I'm for Reel: Unspooling the Affordable, Accessible Microeconomy of the Cassette Revival". TheStranger. Retrieved 14 August 2023.

- ^ "History of Compact Cassette". Archived from the original on 26 February 2011. Retrieved 4 June 2012.

- ^ Canby, Tatnall (1968). "CrO2 - Tomorrow's Tape". Studio Sound (5): 239.

- ^ Stark, Craig (1992). "Choosing the Right Tape". Stereo Review (March): 45–48.

- ^ Werner Abelshauser; Wolfgang von Hippel; Jeffrey Allan Johnson; Raymond G. Stokes (2003). German Industry and Global Enterprise: BASF: The History of a Company. Cambridge University Press. p. 585. ISBN 978-0-521-82726-3.

- ^ "Which Type of Audio Cassette Tape is Right for You : Type 1, 2 or 4 ? - Cassette Player Culture". cassette-player.com. Archived from the original on 2 July 2024. Retrieved 2 July 2024.

- ^ van der Lely, P.; Missriegler, G. (1970). "Audio tape cassettes" (PDF). Philips Technical Review. 31 (3): 85. Archived from the original (PDF) on 10 November 2018. Retrieved 3 September 2018.

- ^ "Audio tape length and thickness". en.wikiaudio.org. Archived from the original on 17 March 2018. Retrieved 16 March 2018.

- ^ "NAC Audio Cassette Glossary – Cassetro". nactape.com. Archived from the original on 16 March 2018. Retrieved 16 March 2018.

- ^ "VintageCassettes.com". Archived from the original on 6 August 2011. Retrieved 26 September 2011.

- ^ "Compact Cassettes". Thomann U.K. International Cyperstore. Archived from the original on 11 August 2010. Retrieved 22 October 2010.

- ^ a b "Happy 50th birthday, Compact Cassette: How it struck a chord for millions". The Register. 30 August 2013. p. 2. Retrieved 29 April 2016.

In a mono arrangement, each track is 1.5mm per side across the 3.8mm tape width. For stereo, the left and right tracks are only 0.6mm apiece, with 0.3mm separation to avoid crosstalk.

- ^ Cassette adapters are remarkably simple

- ^ Patent EP 0078997 A2 – Bandkassette mit einem Aufzeichnungsträger mit Magnetspur und Echolöscheinrichtungen für solche Bandkassetten, eingetragen am 28. Oktober 1982

- ^ Pogue, David (1 September 2016). "Digitize Those Memory-Filled Cassettes before They Disintegrate". Scientific American. Archived from the original on 12 August 2023. Retrieved 12 August 2023.

- ^ "Philips Compact Cassette". Philips Museum. Archived from the original on 11 July 2010. Retrieved 20 August 2010.

- ^ Williams, Stephen (4 February 2011). "For Car Cassette Decks, Play Time Is Over". New York Times. Archived from the original on 10 November 2012. Retrieved 18 July 2012.

- ^ "Demand actually increasing for cassette tapes". AfterDawn. 18 May 2009. Archived from the original on 17 November 2015. Retrieved 25 February 2014.

- ^ Aston, Val. "Chemotherapy Information for Patients and their Families: Audio Cassettes, a New Way Forward". European Journal of Oncology Nursing. 2.1 (1998): 67-8.

- ^ "Analysis of an SDR Cassette Tape". April 2009. Archived from the original on 26 January 2021. Retrieved 31 August 2009.

- ^ "Cassettes". Branham.org. Retrieved 20 October 2025.

- ^ "VintageCassette.com". Archived from the original on 2 September 2006. Retrieved 13 September 2006.

- ^ Molenda, Michael (2007). The Guitar Player Book: 40 Years of Interviews, Gear, and Lessons from the World's Most Celebrated Guitar Magazine. Hal Leonard Corporation. p. 180. ISBN 9780879307820.

- ^ Verna, Paul (11 September 1999). "Tascam Marks 25 Years Of Audio Innovation". Billboard. p. 64. Retrieved 18 December 2024.

- ^ "Island Records launched 'One Plus One' cassettes". Rock History. 13 February 2013. Archived from the original on 29 June 2013. Retrieved 4 April 2013.

- ^ "CBS Songs Ltd v Amstrad Consumer Electronics Plc [1988] UKHL 15 (12 May 1988)". British and Irish Legal Information Institute. Retrieved 6 May 2025.

- ^ CBS v. Ames (1982)

- ^ Dubey, N. B. (December 2009). Office Management: Developing Skills for Smooth Functioning. Global India Publications. ISBN 978-93-80228-16-7.

- ^ Chiu, David (26 October 2016). "The Forgotten Precursor to iTunes". Pitchfork. Retrieved 21 June 2020.

- ^ Pountain, Dick (January 1985). "The Amstrad CPC 464". Byte. p. 401. Retrieved 27 October 2013.

- ^ DeWitt, Robert (June 1983). "APX / On top of the heap". Antic. Archived from the original on 19 May 1998. Retrieved 30 October 2013.

- ^ Crookes, David (26 January 2011). "Gadgets: Rage against the machine". The Independent. London. Archived from the original on 29 January 2011. Retrieved 31 January 2012.

Many will recall fiddling around with volume controls on their computer cassette decks in the hope that Manic Miner would actually load and not crash after 30 minutes of listening to beeps and crackles. ... 'I remember listening to Elite load on the BBC Micro for half an hour, only for it to continually fail at 98 per cent complete,' recalls Luke Peters, editor of T3 magazine.

- ^ De Ceukelaire, Harrie (February 1985). "How TurboTape Works". Compute!. p. 112. Retrieved 30 October 2013.

- ^ Lennart Benschop. "BASICODE". Archived from the original on 22 November 2010. Retrieved 20 January 2008.

- ^ "Mixtape: Cassetternet". WNYC Studios. 12 November 2021. Archived from the original on 12 November 2021. Retrieved 24 December 2021.

- ^ "Streamer Cassette (D/CAS) (late 1980s – late 1990s)". Museum of Obsolete Media. 2019. Archived from the original on 19 July 2019. Retrieved 19 July 2019.

- ^ Al Fasoldt (1991). "Sony Unveils the Minidisc". The Syracuse Newspapers. Archived from the original on 23 August 2009.

- ^ Gijs Moes (31 October 1996). "Successor of cassette failed: Philips stops production of DCC". Eindhovens Dagblad.

- ^ "Cassette vs. Digital". J&R Product Guide. Archived from the original on 28 September 2007.

- ^ "Phonograph records and prerecorded audio tapes and disks". Gale Encyclopedia of American Industries. 2005. Archived from the original on 2 May 2019. Retrieved 20 September 2006.

- ^ Jer Davis (2000). "The Rome MP3: Portable MP3 player—with a twist". The Tech Report. Archived from the original on 13 August 2006. Retrieved 18 September 2006. (Internet Archive link)

- ^ "C@MP CP-UF32/64 a New Portable Mp3-Player Review". Fastsite. 2000. Archived from the original on 14 September 2010. Retrieved 18 September 2006.

External links

[edit]- Project C-90, a website dedicated to cassette tapes

- tapedeck.org, an online collection of blank audio tape cassettes

Cassette tape

View on GrokipediaThe Compact Cassette is an analog magnetic tape sound recording format developed by Philips engineers in the Netherlands, featuring a small, reversible plastic cartridge housing two spools of 3.81-millimeter-wide polyester tape that advances at 4.76 centimeters per second past recording and playback heads.[1][2] Initially designed for portable dictation machines to replace cumbersome reel-to-reel recorders, the format debuted publicly at the 1963 Berlin Radio Exhibition with the Philips EL 3300 player, enabling simple one-handed operation and easy tape insertion without threading.[1] Pre-recorded music cassettes emerged in 1965, but mass adoption accelerated in the 1970s through affordable stereo players, blank tapes for home dubbing, and innovations like the 1979 Sony Walkman, which popularized personal portable audio and mixtape culture, fundamentally altering music consumption by allowing users to curate and share custom playlists.[3][4] The format's versatility extended to data storage for early microcomputers, such as the Commodore PET, and voice recording in answering machines, though it faced limitations in audio fidelity compared to vinyl or later digital media due to tape hiss, wow and flutter, and variable bias requirements for different tape types (normal, chrome, metal).[2] By the 1980s, cassettes dominated prerecorded music sales in the United States, outselling vinyl until the mid-1990s CD surge, yet they sparked industry concerns over home taping's impact on royalties—famously encapsulated in the "Home Taping Is Killing Music" campaign—while empirically democratizing access to music in developing regions through low-cost duplication.[5][6] Despite declining with digital formats, the cassette's mechanical simplicity, durability, and analog warmth have fueled niche revivals among audiophiles and indie artists since the 2010s.[7]

History

Precursors and Invention

Magnetic tape recording originated with Fritz Pfleumer's 1928 invention of a paper strip coated with iron oxide particles for capturing audio signals via magnetization.[8] This technology evolved into practical reel-to-reel systems in the 1930s, with AEG's Magnetophon machines achieving high-fidelity recordings at speeds like 30 cm/s, but requiring open reels that demanded manual threading and were prone to tangling.[9] Post-World War II, consumer reel-to-reel recorders proliferated, offering speeds of 3.75 to 7.5 inches per second (ips) for audio playback, yet their bulk and operational complexity limited portability for everyday use such as dictation or mobile listening.[10] Efforts to simplify tape handling led to enclosed cartridge formats in the 1950s. In 1952, inventor Bernard Cousino developed endless-loop cartridges for continuous playback in advertising and broadcast applications, influencing later designs by eliminating reel changes.[11] RCA introduced its Sound Tape Cartridge in 1958, a quarter-inch tape system in a plastic enclosure providing stereo audio at 3.75 ips with about 30 minutes per side, aimed at home and educational use like language labs, though it failed commercially due to high costs and limited prerecorded content availability before discontinuation in 1964.[12] Similarly, Norelco's Carry-Corder around 1964 featured small internal reels for portable dictation at lower speeds, offering better convenience than open reels but still larger and less standardized than later formats.[10] The compact cassette addressed these shortcomings through Philips' development in the early 1960s. Dutch engineer Lou Ottens, working at Philips' Hasselt laboratory in Belgium, sought a pocket-sized alternative to bulky reel-to-reel portables for dictation, prototyping in 1962 by crafting a wooden block to define the cassette's dimensions—roughly matching a pack of cigarettes—and adapting thin BASF magnetic tape into a self-contained, self-threading shell with dual hubs.[13] This design used 1/8-inch tape at 1.875 ips for mono recording initially, prioritizing compactness over audio fidelity to enable easy insertion and ejection without exposed reels.[14] Philips unveiled the first compact cassette recorder, the EL 1903, at the Berlin Radio Exhibition on August 30, 1963, marking the format's public debut before broader commercialization.[1]Commercial Development and Release

The compact cassette, developed by a team at Philips led by engineer Lou Ottens, emerged as a response to the limitations of bulky reel-to-reel tape recorders for portable dictation purposes.[5] In early 1962, Ottens created a prototype by manually winding tape onto a small plastic holder, aiming for a format compact enough to fit in a shirt pocket while enabling easy insertion and removal without threading.[15] By mid-1963, Philips had refined the design into the EL 3300, a battery-powered mono recorder featuring the new cassette format with 3.81 mm tape width and four tracks for one direction playback.[16] Philips unveiled the EL 3300 and compact cassette on August 28, 1963, at the Berlin Radio Exhibition, marking the format's public debut as the world's first mass-produced cassette recorder. Priced at approximately 150 Dutch guilders (equivalent to about $40 USD at the time), the device targeted business users for voice recording, with initial sound quality deemed insufficient for music reproduction due to narrow track width and basic ferrochrome tape formulation.[17] To promote rapid adoption, Philips adopted an open licensing policy, freely granting manufacturing rights to other companies without royalties, which facilitated global standardization and production.[18] In North America, Philips licensed the technology to its subsidiary Norelco, releasing the Carry-Corder 150 in 1964 as the first U.S. commercial cassette recorder, rebranded with minor adaptations for the market.[19] Early cassettes used BASF PES-18 tape stock, offering 30 or 60 minutes of recording time per side at 4.76 cm/s speed, though prerecorded music cassettes did not appear until 1965, starting with limited titles due to fidelity concerns.[15] This initial commercial phase emphasized portability and convenience over audio performance, setting the stage for subsequent improvements by licensees like Sony, who introduced stereo capabilities in 1966.[18]Rise to Widespread Popularity

Following its initial commercialization in 1965 primarily for dictation purposes, the compact cassette saw gradual adoption in consumer audio applications during the late 1960s. Higher-fidelity tape formulations, such as TDK's SD cassette introduced in 1968 specifically for Hi-Fi playback, marked an early shift toward music recording and reproduction, appealing to audiophiles seeking alternatives to reel-to-reel systems.[15] By 1969, over 85 manufacturers worldwide were producing cassette players, with annual unit sales reaching 2.5 million, reflecting growing market penetration beyond professional use.[4] The 1970s accelerated the cassette's rise as pre-recorded music became widely available, supplanting 8-track cartridges in automotive and home stereos due to the format's superior portability, durability, and ease of use. In the United States, prerecorded cassettes debuted commercially in July 1966 through Philips' affiliate Mercury Records, but mass consumer acceptance surged mid-decade as player affordability improved and tape quality advanced with innovations like chromium dioxide formulations around 1970, which extended dynamic range and reduced distortion.[20] Automakers increasingly integrated cassette decks as standard features by the late 1970s, capitalizing on the medium's compact size compared to vinyl records and 8-tracks, which facilitated widespread in-car listening.[21] A pivotal catalyst occurred in 1979 with Sony's introduction of the Walkman TPS-L2, the first mass-market portable cassette player, which sold over 50,000 units within the first two months despite lacking recording capability.[22] This device popularized personal, on-the-go audio consumption, enabling users to carry customized mixtapes and fostering a cultural shift toward individualized music experiences; by the early 1980s, Walkman variants and competitors had propelled cassette playback into everyday mobility, from jogging to commuting. The format's blank tape versatility also empowered home recording and duplication, amplifying its appeal amid rising music piracy concerns, though legitimate sales benefited from the ecosystem's expansion.[5] By 1983, cassettes had overtaken vinyl as the leading prerecorded music medium in key markets, setting the stage for peak dominance through the decade.[23]Cassette Culture and Peak Adoption

The Compact Cassette reached its zenith of commercial popularity during the 1980s, supplanting vinyl long-playing records as the primary format for music distribution. In the United States, cassette shipments first exceeded those of LPs in 1984, capturing over 50% of the recorded music market share thereafter until the ascent of compact discs in the early 1990s.[24] Globally, sales peaked in the mid-1980s at approximately 900 million units annually, representing 54% of total music sales.[25] In the US, cassette revenues crested at $3.7 billion in 1989, reflecting widespread integration into automobiles, home stereos, and emerging portable devices.[23] This era's proliferation owed much to innovations enhancing portability and accessibility, notably Sony's Walkman, introduced on July 1, 1979, which sold millions of units and propelled cassettes past vinyl in consumer preference by enabling on-the-go playback with headphones.[22] The device's success democratized personal audio consumption, fostering habits of individualized listening that extended to boomboxes and car cassette decks, embedding the format in youth and urban culture worldwide.[5] Parallel to mass-market dominance, "cassette culture" arose as a grassroots phenomenon, defined by the exchange of homemade audio tapes among enthusiasts, particularly in rock, alternative, and experimental genres, as an extension of mail art and DIY ethos.[26] Independent musicians and labels leveraged low-cost duplication—often via home recorders—to bypass traditional industry gatekeepers, distributing limited-run tapes through networks of fanzines, clubs, and international mail trades from the late 1970s into the 1990s.[27] This subculture thrived on the format's affordability and ease of production, enabling genres like industrial, noise, and indie to proliferate outside mainstream channels, with compilations and bootlegs serving as key mediums for discovery and community building. Mixtapes epitomized cassette culture's creative core, allowing users to curate personalized compilations from radio broadcasts, vinyl rips, or live recordings, often shared as gifts or traded socially, which cultivated intimate, analog expressions of taste amid rising home taping practices.[4] By the late 1980s, such practices had normalized cassette ownership, with peak adoption correlating to over 442 million pre-recorded units shipped in the US alone in 1990, before digital alternatives eroded the format's ubiquity.[28]Decline and Technological Obsolescence

The compact cassette format reached its commercial zenith in the late 1980s and early 1990s, accounting for over 50% of U.S. prerecorded music sales through 1991, but began a precipitous decline thereafter as compact discs (CDs) gained market dominance.[7] CDs, introduced commercially in 1982, offered digital audio reproduction with superior fidelity, eliminating the inherent analog limitations of cassettes such as tape hiss, wow and flutter, and frequency response constraints typically limited to 15-18 kHz on high-end equipment.[29] By 1992, CD unit sales had surpassed cassettes in the U.S., driven by random track access, greater durability without mechanical wear or magnetic degradation over time, and resistance to environmental factors like humidity that plagued magnetic tape.[24] Efforts to extend cassette viability, such as the Digital Compact Cassette (DCC) introduced by Philips in 1992, failed to reverse the trend due to consumer reluctance to adopt yet another format amid the CD's momentum and the impending rise of digital file formats like MP3.[30] DCC production ceased in 1996 after meager sales, underscoring cassettes' inability to compete with optical media's precision and convenience.[31] Prerecorded cassette shipments plummeted from hundreds of millions annually in the early 1990s to under 5% market share by 2001, exacerbated by the advent of writable CDs and peer-to-peer file sharing in the late 1990s.[3] Major manufacturers discontinued pre-recorded cassette production by 2002-2003, rendering the format technologically obsolete for mainstream consumer audio as blank tape demand also waned with the shift to solid-state digital storage.[32] While cassettes persisted in niche applications like dictation until the mid-2000s, their analog nature—prone to signal loss from print-through, demagnetization, and mechanical inconsistencies—yielded to digital alternatives providing lossless reproduction and infinite scalability without physical degradation.[33] By the early 2010s, cassette decks were absent from new consumer electronics, confined to archival or hobbyist use.[34]21st-Century Revival

In the early 2000s, cassette tape production had dwindled to negligible levels following the dominance of compact discs and digital formats, with U.S. shipments falling below 10 million units annually by 2001.[35] A resurgence began in the mid-2010s, driven by niche markets in independent music scenes, where cassettes appealed to DIY labels and punk communities for their low-cost duplication and aesthetic appeal.[36] By 2015, U.S. cassette album sales had climbed to approximately 74,000 units, marking the start of consistent year-over-year growth.[37] Sales accelerated through the late 2010s and into the 2020s, fueled by nostalgia among millennials and Generation Z, who sought tangible alternatives to streaming amid a broader analog revival paralleling vinyl's popularity.[38] U.S. cassette album shipments reached 440,000 units in 2022, up from prior years, with major artists such as Taylor Swift, Billie Eilish, and Olivia Rodrigo issuing limited-edition releases to capitalize on collector demand.[39][40] This growth exceeded 440% over the decade ending in 2023, according to industry tracking, though volumes remained a fraction of vinyl's 43 million units that year.[39] In 2023, sales held steady at around 436,400 units, reflecting sustained interest despite supply constraints.[41] Manufacturing capacity expanded to meet demand, with National Audio Company in Springfield, Missouri—the world's largest cassette producer—ramping up to 30 million units annually by 2024, including custom runs for labels and artists.[42][39] The format's revival emphasized short-run editions and aesthetic packaging over high-fidelity playback, positioning cassettes as affordable collectibles rather than primary listening media.[38] Sales surged further in 2025, doubling in the U.S. first quarter to over 63,000 units and projecting annual totals above 600,000, attributed to viral marketing and releases from acts like ABBA and Eminem.[43][44] This trend underscores cassettes' niche endurance, supported by physical media's appeal for ownership and curation in an era of ephemeral digital consumption.[45]Physical Design and Components

Tape Formulations and Types

The magnetic tape employed in compact cassettes features a polyester base film, typically 12 micrometers thick, coated with a ferromagnetic layer composed of acicular particles suspended in a resin binder, incorporating dispersants, lubricants, and sometimes conductive materials to reduce static.[46] The particles align longitudinally to store audio signals as varying magnetic orientations, with the original 1963 Philips formulation relying on gamma ferric oxide (γ-Fe₂O₃) for its balance of coercivity and remanence suitable for consumer recorders.[46] Subsequent refinements included particle size reduction to 0.2–0.75 μm and doping with cobalt to enhance magnetic properties without altering type classifications fundamentally.[47] Cassette tapes are differentiated into types (I–IV) by their magnetic formulations, which dictate required bias oscillator levels—high-frequency signals (around 100 kHz) added during recording to linearize the magnetization curve and minimize distortion—and playback equalization curves.[46] Type distinctions are indicated by notches on the cassette shell: absent for Type I, a single pair for Type II, and double pairs for Types III and IV.[48]| Type | Primary Magnetic Particles | Bias Level | Equalization | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| I (Normal/Ferric) | Gamma ferric oxide (γ-Fe₂O₃) | Normal (100%) | 120 μs | Coercivity around 350–400 oersted; provides warm midrange but higher self-noise and limited high-frequency headroom; evolved with finer grains and cobalt doping for improved output.[47] [49] |

| II (Chrome/High Bias) | Originally chromium dioxide (CrO₂); later predominantly cobalt-doped ferric oxide (ferricobalt pseudochrome) | High (150% of normal) | 70 μs | Higher coercivity for better treble response and signal-to-noise ratio than Type I, though actual CrO₂ usage declined due to toxicity and cost; requires compatible decks to avoid overbias distortion.[47] [49] |

| III (FerriChrome) | Dual-layer: ferric oxide base with chromium dioxide topcoat | High | 70 μs | Aimed to merge Type I low-frequency strength with Type II highs but suffered from inconsistent performance and manufacturing complexity, leading to commercial obsolescence by the early 1980s.[49] |

| IV (Metal) | Pure metallic particles (e.g., iron alloyed with nickel-cobalt) | Metal (200–250% of normal) | 70 μs | Elevated remanence (3000–3500 gauss) and coercivity (>1000 oersted) enable superior dynamic range, low noise, and extended frequency response up to 20 kHz on high-end decks; demands precise equipment matching to prevent saturation.[48] [46] |

Cassette Shell Construction

The compact cassette shell comprises two precision-molded plastic halves, typically constructed from polystyrene or ABS materials, measuring approximately 100 mm × 63 mm × 12 mm.[50][51] These halves enclose the internal components and are joined using four or five stainless steel screws for structural rigidity or, in later designs, ultrasonic welding to create a seamless seal, though the latter risks thermal distortion during production.[52] The exterior includes three rectangular apertures aligned for the erase head, record/playback head, and pinch roller contact; two circular capstan holes; two square reference holes for precise deck alignment; and plastic tabs for write-protection switching.[52] Transparent sections or windows, often integrated into the shell walls at uniform thickness, permit visual inspection of the tape hubs.[52] Internally, the shell houses two low-friction plastic hubs (often Delrin-type material) with interlocking leader attachments for winding the magnetic tape; a pressure pad assembly featuring a tightly napped felt pad mounted on a foam or metal spring to ensure consistent tape-to-head contact; lubricated slip sheets coated with Teflon, silicone, or graphite to minimize friction and guide tape movement; and edge felt pads to prevent abrasion.[52] A non-magnetic metal shield plate behind the pressure pad reduces electromagnetic interference with the heads.[53] Some variants incorporate stainless steel axle pins for optional roller guides to enhance tape alignment, while BASF's patented security mechanism features flanged edges to mitigate tape edge damage during transport.[52] Shell halves are produced via injection molding of molten plastic, such as polystyrene variants stable up to 85°C or polypropylene resins filled with inorganic particles like calcium carbonate for durability, requiring exact tolerances to eliminate seams, burrs, or concentricity errors that could impair tape tracking.[52][54] Precision in molding the long window designs, as used by BASF, also reinforces the structure against skew and resonance issues.[52]Track Layout and Length Variants