Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Tinian Naval Base

View on Wikipedia

Tinian Naval Advanced Base was a major United States Navy sea and air base on Tinian Island, part of the Northern Mariana Islands on the east side of the Philippine Sea in the Pacific Ocean. The base was built during World War II to support bombers and patrol aircraft in the Pacific War. The main port was built at the city and port of San Jose, also called Tinian Harbor. All construction was carried out by the Navy's Seabees 6th Naval Construction Brigade, including the main two airfields: West Field and North Field, serving the United States Army Air Forces's long-range Boeing B-29 Superfortress bombers. The Navy disestablished the Tinian Naval Advanced Base on 1 December 1946.

Key Information

Background

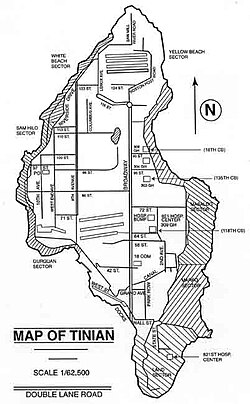

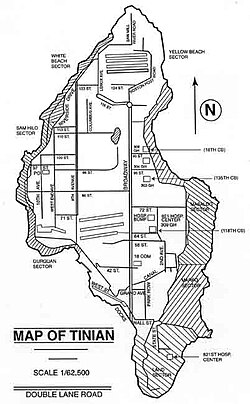

[edit]Tinian, the third of the three largest islands of the Mariana Islands, is located south of Saipan across the 3-mile-wide Saipan Channel. Tinian, north to south, is 12 miles long and east to west 6 miles wide. It has mostly flat terrain, perfect for runways. Along with the other Mariana Islands, Tinian was claimed for Spain by Ferdinand Magellan in 1521. Guam was seized by the United States in the Spanish-American War, and Spain sold the remaining islands to Germany. They were occupied by Japan during World War I and became part of Japan's South Seas Mandate. Japan developed Tinian into a large sugar plantation with a sugar refining plant, and built three small runways on the island. The civilian population was about 18,000 in 1941.[1]

Operation Forager involved the conquest of the Mariana Islands. It was intended that they would be developed into a major naval base for the surface ships and submarines of the Pacific Fleet, as a staging and training area for ground troops, and as a base from which long-range Boeing B-29 Superfortress bombers could attack Japan.[2] American forces landed on Tinian on 24 July 1944,[3] and the island was declared secured on 1 August, although there were still many Japanese soldiers holding out in the caves on the southern end of the island.[4] At the time of the landing, there were three Japanese airfields on the island: two in the north, one with a runway 4,700 feet (1,400 m) long and the other 3,900 feet (1,200 m) long, and one in the west with a 4,000-foot (1,200 m) runway. There was also a small, incomplete airstrip in the center of the island.[5]

Construction

[edit]Early works

[edit]Responsibility for construction on Tinian was assigned to the 6th Naval Construction Brigade, under the command of Captain Paul J. Halloran.[6] His staff, along with that of the US Army's 64th Engineer Topographic Battalion, drew up plans for the development of Tinian at Pearl Harbor in the months leading up to Operation Forager. These called first for the rehabilitation of the Japanese airstrips in the north and west, then for them to be lengthened to 6,000 feet (1,800 m) in length so bombers could operate from them, and ultimately for their extension to 8,500 feet (2,600 m) for the B-29s.[7]

For this work, Halloran had the 29th and 30th Naval Construction Regiments.[6] The former, under Commander Marvin Y. Neely, initially consisted of the 18th, 92nd and 107th Naval Construction Battalions, and the 1036th Naval Construction battalion Detachment;[8] the latter, under Commander Jonathan P. Falconer, the 67th, 110th and 121st Naval Construction Battalions.[9] A third regiment, the 49th Naval Construction Regiment, was formed on 2 March 1945 from the 9th, 38th, 110th and 112th Naval Construction Battalions, under Commander Thomas H. Jones.[6]

Elements of the 18th and 121st Naval Construction Battalions landed on Tinian with the assault troops on 24 July, with the remainder arriving on 27 July. That day, the 121st commenced the rehabilitation of the 4,700-foot (1,400 m) airstrip in the north, filling in the bomb and shell craters. By that evening, an airstrip 2,500 feet (760 m) long and 150 feet (46 m) wide was ready for use, and it was fully restored to its full length the next day.[10] On 29 July, a P-47 landed and took off again.[11] The 9th Troop Carrier Squadron was brought forward from Eniwetok, and its Douglas C-47 Skytrains, together with the Curtiss C-46 Commandos of VMR-252, delivered 33,000 rations from Saipan on 31 July. On the return trip they carried wounded to hospitals on Saipan.[12][13]

A third battalion, the 67th Naval Construction Battalion, arrived on 2 August.[14] With the island declared secure, the seabees were released from the control of the V Amphibious Corps to the 6th Naval Construction Brigade, which became operational on 3 August.[10] Additional naval construction battalions arrived over the following weeks and months: the 92nd from Saipan in August and September;[15] the 107th from Kwajalein on 12 September;[16] the 110th from Eniwetok in September and October;[17] the 13th and 135th on 24 October;[18][19] the 50th on 19 November,[20] the 9th on 1 December,[21] and the 38th and 112th on 28 December.[22][23]

The Seabees completed and extended the second Japanese airstrip in the north, which became North Field Strip No. 3 in September. They then rehabilitated the severely damaged airstrip in the west as a 4,000-foot (1,200 m) airstrip for fighter planes. Navy patrol planes commenced operations from the two North Field airstrips, but work to upgrade them to handle the B-29s could not be carried out while they were in use. A new 6,000-foot (1,800 m) runway was built in the west, which became known as West Field Strip No. 3. The airstrip was completed on 15 November. In addition to the runway, there were 16,000 feet (4,900 m) of taxiways, 70 hardstands, 345 Quonset huts, 33 repair and maintenance buildings, 7 magazines and a 75-foot (23 m) tall control tower.[24]

Airfields

[edit]Responsibility for the development of North Field was assigned to the 30th Naval Construction Regiment. Falconer divided the work into phases, and designated a battalion as the "lead" on each phase, with overall responsibility for the work in the phase, and the other battalions acting as subcontractors. The first phase, the extension of North Field Strip No. 1 to 8,500 feet (2,600 m), along with the construction of the necessary taxiways, hardstands and aprons, was assigned to the 121st Naval Construction Battalion. The work was completed nine days ahead of schedule, and the first B-29 landed on the completed airstrip on 22 December. The next phase was the extension of North Field Strip No. 3 to 8,500 feet (2,600 m). This work was undertaken by the 67th Naval Construction Battalion as the lead battalion, and was completed on a day ahead of schedule on 14 January 1945. The 13th Naval Construction Battalion became the lead on the third phase, the construction of North Field Strip No. 2, between and parallel to the other two runways. The final runway, parallel to the other three, was assigned to the 135th Naval Construction Battalion and was completed on 5 May 1945, five days ahead of schedule. All four strips were widened to 500 feet (150 m).[6][25]

The task would have been easier if the plateau had been wider. As it was, the 7,000-foot (2,100 m) wide plateau required large amounts of fill. Another complicating factor was the decision to have the B-29 taxi under their own power instead of being towed reduced the maximum taxiway grade from 2+1⁄2 to 1+1⁄2 percent, and required another 500,000 cubic yards (380,000 m3) of earth to be removed. When work was completed on 5 May 1945, North Field had four parallel 8,500-foot (2,600 m) runways, 1,600 feet (490 m) apart, with 11 miles (18 km) of taxiways, 265 hardstands, 173 Quonset huts and 92 other buildings.[26] All runways and taxiways were paved with 2 inches (51 mm) of asphalt concrete over a base course of at least 6 inches (150 mm) of rolled coral on a subbase of pure coral.[27] Its construction involved 2,109,800 cubic yards (1,613,100 m3) of excavations and 4,789,400 cubic yards (3,661,800 m3) of fill.[26]

The 49th Naval Construction Regiment was assigned responsibility for the construction of the West Field airstrips. This new regiment began activities under a temporary title on 1 January 1945 before it was formally activated on 2 March. Work on West Field commenced on 1 February. Two parallel airstrips were developed, 1,600 feet (490 m) apart, each 8,500 feet (2,600 m) long and 500 feet (150 m) wide. The two runways, 53,000 feet (16,000 m) of taxiways, 220 hardstands and 251 administration, maintenance and repair buildings. Work on West Field Strip No. 2 was completed on 2 April and West Field Strip No. 1 followed on 20 April.[6][26] The 9th Naval Construction Battalion detached from the 49th Naval Construction Regiment on 25 May under orders to move to Okinawa, and departed on 19 June, followed by the 112th, which was detached on 5 July and embarked three days later. The 49th Naval Construction Regiment was then absorbed by the 29th Naval Construction Regiment.[6][21][23]

Fuel

[edit]

Initially, fuel had to be supplied in drums. Later, aviation gasoline was drawn from a barge known as YOGL anchored in Tinian Harbor. Tank farm construction commenced in September 1944 and on 3 November it became the responsibility of the 29th Naval Construction Regiment, with the 18th Naval Construction battalion as the lead battalion. The fuel storage and distribution system was completed by 8 March 1945. This included storage tanks for 14,000 US barrels (1,700,000 L) of diesel oil, 20,000 US barrels (2,400,000 L) of motor gasoline and 165,000 US barrels (19,700,000 L) of aviation gasoline. Fuel was pumped over a submarine pipeline from an oil tanker moored north of Tinian Harbor and distributed over 86,000 feet (26,000 m) of pipeline. Two dispensing points were provide at West Field and four at North Field.[27]

Harbor

[edit]Until work on the harbor was completed in March 1945, nearly all cargo was brought ashore by landing craft mechanized (LCM) and landing craft tank (LCT). Cargo handling was supervised by the Army port superintendent, Major Gordon E. Soruton. Tinian Harbor became operational on 2 August 1944, with the 1036th Naval Construction Battalion Detachment, a two-company unit, unloading vessels into LCTs in the stream, which were unloaded on the beaches by Army and Marine work parties.[28][29]

The half-strength 27th Naval Construction Battalion (Special) arrived on Tinian on 19 November 1944, and the 1036th Naval Construction Battalion Detachment took over on the beach while unloading in the stream was handled by the two companies of the 27th Naval Construction Battalion (Special) and the Army's 510th Port Battalion. The first three companies of its five companies arrived in November 1944. The beach work parties were relieved, and henceforth the three stevedore units handled all cargo. The 1036th Naval Construction Battalion Detachment was absorbed by the 27th Naval Construction Battalion (Special) on 20 January 1945.[28][29]

Early works on the harbor were carried out by the 50th and 92nd Naval Construction Battalions, which drove 200 feet (61 m) of piling that eventually formed part of the south bulkhead, and by the 107th Naval Construction battalion, which built a 1,150-foot (350 m) ramp from the shore to the reef. In November 1944, the 50th Naval Construction Battalion commenced a major project to build permanent harbor facilities that could berth up to eight Liberty ships at a time.[29]

The new harbor consisted of a 600-foot (180 m) south bulkhead, a 2,000-foot (610 m) quay wall, and two 80-by-500-foot (24 by 152 m) piers parallel to the cargo ship bulkhead and connected to it by an 88-foot (27 m) causeway. A breakwater was built upon the existing reef consisting of 120 circular sheet piling cells that were 30 feet (9.1 m) in diameter and filled with coral. The task of dredging a 32-foot (9.8 m) deep channel and 28-foot (8.5 m) deep berths was undertaken by the 31st Naval Construction Battalion, which was part of Service Squadron 12. Dredging was completed on 20 January 1945, and the harbor works were completed on 6 March.[29]

Other facilities

[edit]

The Japanese roads on the island were too narrow for heavy construction vehicles, had inadequate drainage, and lacked shoulders. They were resurfaced with 8 inches (200 mm) of pit coral, and drainage and shoulders were added. Due to the shape of the island and the grid layout of its roads bearing a resemblance to those of Manhattan, the streets were named after those of New York City. The Japanese town of Sunharon became known as the Village because its location corresponded to that of Greenwich Village, and the open area between North and West Fields became known as Central Park. Another 34 miles (55 km) of new roads were built, with 22-foot (6.7 m) roadways and 3-foot (0.91 m) shoulders.[30][31]

Accommodation was constructed for 12,000 Seabees, 13,000 other navy personnel, and 21,500 Army personnel. A 100-bed tent hospital was erected in September 1944. The 600-bed Navy Base Hospital 19 opened in December. It was subsequently upgraded to a 1,000-bed hospital. The Army's 600-bed 374th Station Hospital opened in March 1945, and the 1,000-bed 48th Station Hospital hospital in June on the camp site of the 135th Naval Construction Battalion after it moved to Okinawa. In August, the 4,000-bed 821st Hospital Center on the South Plateau was under nearing completion.[32][33]

The 18th Naval Construction Battalion handled construction of the Marine Corps's 7th Field Depot, which was subsequently converted to a quartermaster depot for the Army garrison. When complete, it consisted of three camp sites with 386,000 square feet (35,900 m2) of warehouse storage, 2,000,000 square feet (190,000 m2) of open air storage and 63,000 cubic feet (1,800 m3) of refrigerated storage. The naval supply depot had 16,000 square feet (1,500 m2) of warehouse storage. Construction of an ammunition storage dump commenced in September 1944. On completion in February 1945, it had 254 25-by-75-foot (7.6 by 22.9 m) revetments with coral surfaces and 14 miles (23 km) of roads. Work on a bomb dump with 468 revetments commenced in January 1945, and was completed by the middle of the year. To support Operation Starvation, the aerial mining campaign against Japan, an aerial mining depot was built with Quonset hut magazines surrounded by revetments.[32]

Tinian's porous coral soil provides good drainage, so there are no rivers or creeks on the island, and only one small fresh-water lake, Hagoi (whose name means "lake" in the Chamorro language).[34][35] However, the annual rainfall is more than 100 inches (2,500 mm), so the Japanese developed a system of wells and reservoirs.This was rehabilitated by the Seabees, who sunk 17 new wells. Initially water was rationed to 20 US gallons (76 L) per man per day, but eventually a water supply system was developed with a capacity of 1,800,000 US gallons (6,800,000 L) per day, and water rationing was no longer required.[35]

Operations

[edit]US Navy Patrol Wings used PB4Y-1, PB4Y-2, P4M-1 and PV-1 aircraft to patrol from Tinian airfields. Fleet Air Wing Eighteen, a Navy Patrol Wing moved its headquarters to Tinian on 25 May 1945.[36] Bombing Squadron 102 (VB-2) began patrols from Tinian on 2 August 1944,[37] Patrol Bombing Squadron 111 (VPB-111) on 1 December,[38] Patrol Bombing Squadron 108 (VPB-108) on 4 April 1945,[39] Patrol Bombing Squadron 123 (VPB-123) on 25 May,[39] and Patrol Squadron 1 (VP-1) on 21 June.[40]

North Field became operational in February 1945 and West Field the following month.[41] The 313th Bombardment Wing arrived from the United States in December 1944 and was based at North Field. The 58th Bombardment Wing arrived from the China-Burma-India Theater in March 1945 and was based at West Field.[42][43] Thus, two of the five bombardment wings of the Twentieth Air Force were based on Tinian.[42][43] A third formation, the 509th Composite Group, arrived in May 1945 and moved to the Columbia University district, south of 125th Street and adjacent to Riverside Drive, near the strips and hardstands of North Field, and took over the area that had been specially constructed for it.[44]

These formations participated in the campaign of air raids on Japan, including the bombing of Tokyo on 10 March 1945,[45] and the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki on 6 and 9 August 1945.[46] Altogether, 29,000 missions were flown by Tinian-based aircraft, and 157,000 short tons (142,000 t) of bombs were dropped.[47]

A series of Japanese air attacks on the Mariana Islands were mounted between November 1944 and February 1945 destroyed 11 B-29s, caused major damage to 8 and minor damage to another 35. American casualties were 45 dead and over 200 wounded. USAAF fighters and anti-aircraft guns downed about 37 Japanese aircraft during these raids.[48]

Camp Churo

[edit]Camp Churo was an internment camp for Tinian civilians founded by the 4th Marine Division on the site of the ruined village of Churo. It was chosen as a permanent camp site, and all the civilians on Tinian were subsequently concentrated there.[49] On 16 August 1945, there were 11,465 internees in Camp Churo.[50] Major General James L. Underhill was appointed Island Commander on 1 August 1944. Nine days later, all forces on Tinian were transferred to his command.[51][52] He was succeeded by Brigadier General Frederick V. H. Kimble on 28 November 1944.[53]

| Nationality | Men | Women | Children under 16 |

Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Japanese | 2,764 | 2,126 | 4,200 | 9,090 |

| Korean | 905 | 451 | 985 | 2,371 |

| Chinese | 1 | 2 | 1 | 4 |

| Total | 3,670 | 2,579 | 5,186 | 11,465 |

The military government was unprepared to cater for the large number of civilians, and there were critical shortages of relief supplies of all kinds.[54] Seabees supervised the erection of tarpaulin shelters. These were gradually replaced by huts made from corrugated iron and timber salvaged from around the island. The internees also salvaged food supplies, and cultivated gardens. When firewood started to become scarce, Seabees made them improvised diesel stoves.[55]

Some of the first camp administrators were Japanese language experts, including one who was born in Japan, so they were familiar with the internees' language and customs. The administrators responsible for public safety, education and labor had their offices inside the camp, and so were approachable. The administrators met with each other at weekly staff meetings, ate their meals together in the common mess hall, and socialized at the officers' club, where African-American sailors waited on them.[56]

There were separate Japanese and Korean camps within the camp. The Japanese camp was further divided into nine ku, each with about 1,000 residents, and the Korean one into three ku, each of about 800 residents. Initially they were run by officials appointed by the administration but on 26 July 1945, elections were held. Voter turnout was high: 87 percent of the Japanese and 91 percent of the Koreans voted. Ten officials were elected to the council by the camp Japanese camp at large, and then one was elected sodai (mayor) and the others became kucho. This mirrored the organization of a typical Japanese village. Within each ku there were 15 or 20-by-150-foot (6.1 by 45.7 m) huts called bakusha that were subdivided into ten 10-by-15-foot (3.0 by 4.6 m) dwellings. Each hut housed about 80 people, and there was a leader called a bakushacho. The bakusha were gradually supplemented by other dwellings but the organization remained. Japanese bakushacho were paid $5 a month by the residents; the Koreans paid theirs $3 to $5 depending on the size of the hut.[56] Houses were constructed from whatever materials the residents could salvage, mostly corrugated iron and timber from dunnage.[57][58]

Camp residents were given two meals a day, with the offer to work for pay and extra food.[59] Pay for skilled male workers was 50 cents per eight-hour day; unskilled workers got 35 cents, and women and children 25 cents.[60] Rice and beans were staples, supplemented with canned meat, and fresh fish and vegetables. The ration included two staples of the Japanese diet, miso and shoyu. The miso was made from U.S. Navy beans in the camp miso factory and distributed to the ku kitchens (suiji). Yeast (kōji) was obtained from Japanese stocks found in caves. Boilers to make the shoyu were salvaged from the Tinian sugar mill. Meals were cooked in the suiji; no cooking was permitted in the huts for fear of a fire. The camp had crops and gardens growing fresh produce.[59] Fish was caught during the April through September fishing season, but had to be eaten straight away, because the camp had no facilities for storing it.[61] The water supply came from Lake Hagoi. Cisterns that had been used as pillboxes were refurbished and had a capacity of 273,000 US gallons (1,030,000 L).[62]

A school for the children was opened on 1 November 1944 by two graduates of the Navy language school at the University of Colorado in Boulder. Eighteen experienced Japanese teachers were found to revise and write texts, but were not permitted to teach. Buildings were provided by the military government administration.[63][64] Attendance was voluntary. Schooling was provided in eight grades, six days per week and nine months per year.[65] The curriculum included English, but not Japanese.[66] The school had a library, but all the books were in English. Boy and Girl Scout organizations were established. The education section of the military government operated a movie theater in the school auditorium some evenings that showed United States Office of War Information (OWI) films, and occasionally feature films. It was attended by 5,000 to 8,000 people. As they were in English, a translator had to explain to the audience what was going on.[67][68]

A market place was established, with barber shops, a Korean shoe repair shop and Japanese handicraft shops. Prices were fixed by the military government. They could not sell goods to military personnel directly, but could sell to a post exchange (PX).[69] The Navy also operated the 100-bed Naval Military Government Hospital No. 204 in the camp; 8 officers and 96 enlisted personnel were assigned to it.[70]

In late 1945, Admiral Raymond A. Spruance, the Commander-in-Chief, Pacific Ocean Areas (CINCPOA), ordered the repatriation of all Japanese and Korean civilians. This was completed by late 1946, and Camp Churo was closed.[71]

Post World War II

[edit]

On 18 July 1947, Tinian was transferred from the U.S. Navy to the Trust Territory of the Pacific Islands, a territory controlled by the United States.[72] In 1962, Tinian was transferred to the administration of Saipan as a sub-district. In 1978, it became a municipality in the Commonwealth of the Northern Mariana Islands. West Field became part of Tinian International Airport. North Field was abandoned and fell into disrepair. Part became the National Historic Landmark District. The two bomb pits used to load the Little Boy and Fat Man bombs are enclosed with glazed panels.[73]

The Navy disestablished the naval advanced base on Tinian on 1 December 1946,[74] but the United States military remained on the island. A fifty-year, 17,799-acre (7,203 ha) lease agreement was signed in 1983, under which the land became the Military Lease Area (MLA). The agreement gave the U.S. Department of Defense the option of extending the lease by another fifty years.[75] In 2020 the U.S. Navy commenced vertical construction at Camp Tinian, a small, semi-permanent camp to support Navy and Marine Corps exercises.[76][77]

In 2023, concerns that U.S. air bases in Japan and Guam would be vulnerable to cruise and ballistic missiles if the U.S. was drawn into a conflict with China led to Tinian being reactivated as an alternative base.[78] The National Defense Authorization Act included $26 million for airfield development, $20 million for fuel tanks, $32 million for parking aprons, $46 million for cargo pad and taxiway extension and $4.7 million for a maintenance and support facility on Tinian in 2024.[79] The U.S. Air Force's Rapid Engineer Deployable Heavy Operational Repair Squadron Engineers (RED HORSE) began clearing the overgrown old runways and access roads,[80] and on 11 April 2024, it was announced that Fluor Corporation had been awarded a $409 million contract to rebuild the airbase at North Field.[81]

Historical markers

[edit]

- American Memorial Park, Tinian, contains memorials to US Servicemen and Chamorro and Carolinian civilians who were killed in the Battle of Saipan, Battle of Tinian, and the Battle of the Philippine Sea in 1944.[82]

- The 107th Seabees Monument, a SeaBee Memorial, is on Tinian at 8th Avenue and 86th street, the site of the Seabees camp.[83]

- At Grand Island, Nebraska, there is a Tinian Island Historical marker. Grand Island is where the 6th Bombardment Group trained before being deployed to Tinian in December 1944. Historical marker is titled: B-29 Superfortress / 6th Bomb Group / Tinian Island at 40°58′09″N 98°19′09″W / 40.969196°N 98.319081°W at the Central Nebraska Regional Airport.[84]

- At North Field there is the "Marker "No. 1 Bomb Loading Pit" where the Little Boy was loaded into the B-29 Superfortress Enola Gay at 15°05′01″N 145°38′03″E / 15.083696°N 145.634057°E.[85]

- At North Field there is the Marker "No. 2 Bomb Loading Pit" where the Fat Man was loaded into B-29 Superfortress Bockscar at 15°04′59″N 145°38′02″E / 15.083°N 145.634°E[85]

- The 313th Bombardment Wing has a marker at the United States Air Force Academy in Colorado.[86]

- The Ushi Point Cross and Memorial is at 15°06′00″N 145°38′39″E / 15.100°N 145.6443°E.[87]

- Suicide Cliff in Tinian is the spot where hundreds of Japanese citizens and troops jumped to their death, rather than surrender in 1944, due to Japanese propaganda and brainwashing. Many Japanese residents on Tinian, men, women and children jumped to the coastal rocks and waves below at 14°56′17″N 145°39′07″E / 14.938°N 145.652°E.[88]

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ Morison 1953, pp. 149–154.

- ^ Morison 1953, p. 341.

- ^ Morison 1953, pp. 360–364.

- ^ Morison 1953, p. 369.

- ^ Shaw, Nalty & Turnbladh 1994, p. 398.

- ^ Hoffman 1951, p. 93.

- ^ Shaw, Nalty & Turnbladh 1994, p. 403.

- ^ Carlson, Jen (29 July 2015). "These NYC Streets Are Located In The Middle Of The Pacific Ocean". Gothamist. Retrieved 12 April 2024.

- ^ "WW2 Military Hospitals". WW2 US Medical Research Centre. Retrieved 13 April 2024.

- ^ "CNMI seeks protection of Hagoi". Saipan Tribune. 21 June 1999. Retrieved 12 April 2024.

- ^ Roberts 2000, p. 807.

- ^ Roberts 2000, p. 135.

- ^ Roberts 2000, p. 124.

- ^ a b Roberts 2000, p. 186.

- ^ Roberts 2000, p. 18.

- ^ Rottman & Gerrard 2004, p. 89.

- ^ a b Cate 1953, p. 166.

- ^ a b Taylor et al. 1953, pp. 519–525.

- ^ Taylor et al. 1953, p. 707.

- ^ Taylor et al. 1953, pp. 614–617.

- ^ Taylor et al. 1953, pp. 713–725.

- ^ Richard 1957, p. 148.

- ^ Taylor et al. 1953, pp. 581–582.

- ^ Richard 1957, p. 537.

- ^ a b Embree & Huston 1946, p. 22.

- ^ Hoffman 1951, p. 140.

- ^ Richard 1957, p. 535.

- ^ Richard 1957, p. 539.

- ^ Astroth 2019, pp. 153–155.

- ^ a b Embree & Huston 1946, pp. 22–24.

- ^ Embree & Huston 1946, pp. 25–26.

- ^ Richard 1957, pp. 556–557.

- ^ a b Embree & Huston 1946, p. 25.

- ^ Embree & Huston 1946, p. 15.

- ^ Embree & Huston 1946, p. 7.

- ^ Richard 1957, p. 564.

- ^ Embree & Huston 1946, p. 29.

- ^ Richard 1957, p. 575.

- ^ Richard 1957, p. 494.

- ^ Richard 1957, p. 495.

- ^ Embree & Huston 1946, p. 30.

- ^ Richard 1957, pp. 575–576.

- ^ Embree & Huston 1946, p. 27.

- ^ Richard 1957, p. 540.

- ^ Astroth 2019, p. 172.

- ^ Wright, Carleton H. (November 1948). "Trust Territory of the Pacific Islands". Proceedings. 74 (549): 1333–13342. Retrieved 12 December 2025.

- ^ "Tinian Island During the Manhattan Project". U.S. National Park Service. Retrieved 13 April 2024.

- ^ Roberts 2000, p. 767.

- ^ Special Representatives of the United States and the Commonwealth of the Northern Mariana Islands. Report to the President on 902 Consultations (PDF) (Report). January 2017. pp. 27–30. Retrieved 12 December 2025.

- ^ "DVIDS - News - US Navy Seabees with NMCB 5 start construction on Tinian Island Expeditionary Camp". Department of Defense. Retrieved 11 December 2025.

- ^ Underwood, Brian (19 July 2022). "US Navy, U.S. Navy Seabees and U.S. Marines accomplish a wide scope of engineering projects while at Expeditionary Camp Tinian". Retrieved 31 March 2024.

- ^ Gordon, Chris (3 March 2023). "Photos: F-22s Deploy to Tinian for First Time as Part of ACE Exercise". Air & Space Forces Magazine. Retrieved 13 April 2024.

- ^ Robson, Seth (27 December 2023). "Air Force plans return to WWII-era Pacific airfield on Tinian". Stars and Stripes. Retrieved 13 April 2024.

- ^ De La Torre, Ferdie (4 March 2024). "RED HORSE on Tinian for big North Airfield project". Saipan Tribune. Retrieved 13 April 2024.

- ^ Robertson, Noah (11 April 2024). "US Air Force issues $409 million award for long-sought Pacific airfield". Defense News. Retrieved 13 April 2024.

- ^ "American Memorial Park". U.S. National Park Service. Retrieved 11 April 2024.

- ^ "Memorial 107th Seabees - Tinian". TracesOfWar.com. Retrieved 12 April 2024.

- ^ "B-29 Superfortress / 6th Bomb Group / Tinian Island Historical Marker". Historical Marker Database. Retrieved 12 April 2024.

- ^ a b Wellerstein, Alex. "Going Back to Tinian". Restricted Data. Retrieved 11 April 2024.

- ^ "313th Bomb Wing (VH), a War Memorial". Historical Marker Database. Retrieved 12 April 2024.

- ^ "Tinian Landing Beaches, Ushi Point, and North Fields, Tinian Island". U.S. National Park Service. Retrieved 11 April 2024.

- ^ "Suicide Cliff Tinian - Tinian". TracesOfWar.com. Retrieved 11 April 2024.

References

[edit]- Astroth, Alexander (2019). Mass Suicides on Saipan and Tinian 1944: An Examination of the Civilian Deaths in Historical Context. Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company. ISBN 978-1-4766-7456-8. OCLC 1049791315.

- Cate, James (1953). "The Twentieth Air Force and Matterhorn". In Craven, Wesley Frank; Cate, James (eds.). The Pacific: Matterhorn to Nagasaki, June 1944 to August 1945 (PDF). The Army Air Forces in World War II. Vol. V. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. pp. 3–178. OCLC 69189113. Retrieved 26 June 2023.

- Embree, John F.; Huston, Arthur C. Jr. (Winter 1946). "Military Government in Saipan and Tinian: A report on the Organization of Susupe and Churo, Together with Notes on the Attitudes of the People Involved". Applied Anthropology. 5 (1): 1–39. JSTOR 44135120.

- Hoffman, Carl W. (1951). The Seizure of Tinian (PDF). USMC Historical Monographs. Washington, DC: Historical Division, Headquarters, US Marine Corps. Retrieved 13 March 2024.

- Morison, Samuel Eliot (1953). New Guinea and the Marianas, March 1944 – August 1944. History of United States Naval Operations in World War II. Vol. VIII. Little Brown. OCLC 10926173.

- Richard, Dorothy E. (1957). United States Naval Administration of the Trust Territory of the Pacific Islands. Vol. I: The Wartime Military Government Period, 1942–1945. Washington, D.C.: Office of the Chief of Naval Operations. OCLC 2007144. Retrieved 27 March 2024.

- Roberts, Michael D. (2000). Dictionary of American Naval Aviation Squadrons (PDF). Vol. 2. Washington, D.C.: Naval Historical Center, Department of the Navy. OCLC 1404465672. Retrieved 6 April 2024.

- Rottman, Gordon L.; Gerrard, Howard (2004). Saipan & Tinian 1944: Piercing the Japanese Empire. Oxford: Osprey Publishing. ISBN 978-1-84176-804-5. OCLC 231986835.

- Shaw, Henry I. Jr.; Nalty, Bernard C.; Turnbladh, Edwin T. (1994) [1966]. Central Pacific Drive. History of U.S. Marine Corps Operations in World War II. Vol. 3. Historical Branch, G–3 Division, Headquarters, US Marine Corps. ISBN 978-0-89839-194-7. OCLC 927428034.

- Taylor, James; Cate, James; Olsen, James C.; Futrell, Frank; Craven, Wesley Frank (1953). "Strategic Bombardment from Pacific Bases". In Craven, Wesley Frank; Cate, James (eds.). The Pacific: Matterhorn to Nagasaki, June 1944 to August 1945 (PDF). The Army Air Forces in World War II. Vol. V. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. pp. 507–758. OCLC 69189113. Retrieved 26 June 2023.

- U.S. Navy Department (1947). Building the Navy's Bases in World War II. History of the Bureau of Yards and Docks and the Civil Engineer Corps 1940–1946. Vol. II. Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office. OCLC 1023942.