Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

The White Stripes

View on Wikipedia

The White Stripes were an American rock duo formed in Detroit, Michigan, in 1997. The group consisted of Jack White (guitar, keyboards, piano, vocals) and Meg White (drums, percussion, vocals). They were a leading group of 2000s indie rock and the decade's garage rock revival.

Key Information

Beginning in the late 1990s, the White Stripes sought success within the Detroit music scene, releasing six singles and two albums. They first found commercial success with their acclaimed third album, White Blood Cells (2001), which propelled the band to the forefront of the garage rock movement. Their fourth album, Elephant (2003), drew further success, winning the band their first Grammy Awards. It produced the single "Seven Nation Army", which became a sports anthem and the band's signature song. They experimented extensively on their fifth album, Get Behind Me Satan (2005). They returned to their blues roots with their sixth and final album, Icky Thump (2007), which was praised like the band's earlier albums. By the end of the 2000s, the White Stripes accumulated three entries on the US Billboard Hot 100, eleven entries on the US Alternative Airplay chart, and thirteen entries on the UK singles chart. After a lengthy hiatus from performing and recording, the band dissolved in 2011.

The White Stripes used a low-fidelity approach to writing and recording. Their music featured a melding of garage rock and blues influences and a raw simplicity of composition, arrangement, and performance. The duo were noted for their mysterious public image, their fashion and design aesthetic which featured a simple color scheme of red, white, and black—which was used on every album and single cover they released—and their fascination with the number three. They made selective media appearances, including Jim Jarmusch's anthology film Coffee and Cigarettes (2003) and the documentary Under Great White Northern Lights (2009).

The White Stripes released six studio albums, two live albums, one compilation album, and one extended play. They received numerous accolades, including six Grammy Awards from eleven nominations. The Rock and Roll Hall of Fame included White Blood Cells on their "200 Definitive Albums" list. Rolling Stone ranked White Blood Cells and Elephant on their list of the "500 Greatest Albums of All Time", and named the band the sixth greatest duo of all time in 2015. The White Stripes were inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame in 2025, after being nominated in 2023 (the band's first year of eligibility).

History

[edit]1997–1999: Early years, formation and The White Stripes

[edit]In high school, Jack Gillis (as he was then known)[1] met Meg White at the Memphis Smoke—the restaurant where she worked and where he would read his poetry at open mic nights.[2] The two started dating and began frequenting the coffee shops, local music venues, and record stores of the area.[3] Gillis was an established drummer during this period, performing with his upholstery apprenticeship mentor, Brian Muldoon,[4][5] the Detroit cowpunk band Goober & the Peas,[6][7][8] the garage punk band the Go, the Hentchmen, and Two-Star Tabernacle.

Gillis and White were married in 1996.[9][10] Contrary to convention, he took his wife's surname.[4][11] On Bastille Day 1997,[12] Meg started learning to play the drums. In Jack's words, "When she started to play drums with me, just on a lark, it felt liberating and refreshing. There was something in it that opened me up."[4] The couple then became a band and, while they considered calling themselves Bazooka and Soda Powder,[13] they settled on the White Stripes.[14]

The White Stripes had their first live performance on August 14, 1997, at the Gold Dollar bar in Detroit.[15] They began their career as part of the Michigan underground garage rock scene, playing with local bands such as the Hentchmen, the Dirtbombs, the Gories, and Rocket 455.[16] In 1998, Dave Buick—owner of an independent, Detroit-based, garage-punk label called Italy Records—approached the band at a bar and asked if they would like to record a single.[17] Jack initially declined, believing it would be too expensive, but he eventually reconsidered when he realized that Buick was offering to pay for it.[18] Their debut single, "Let's Shake Hands", was released on vinyl in February 1998 with an initial pressing of 1,000 copies.[19] This was followed in October 1998 by the single "Lafayette Blues" which, again, was only released on vinyl with 1,000 copies.[20][21][22]

In 1999, the White Stripes signed with the California-based label Sympathy for the Record Industry.[23][24] In March 1999, they released the single "The Big Three Killed My Baby", followed by their debut album, The White Stripes, on June 15, 1999.[23] The self-titled debut was produced by Jack and engineered by American music producer Jim Diamond at his Ghetto Recorders studio in Detroit.[25] The album was dedicated to the seminal Mississippi Delta blues musician Son House, an artist who influenced Jack.[26][27] The track "Cannon" from The White Stripes contains part of an a cappella version, as performed by House, of the traditional American gospel blues song "John the Revelator". The White Stripes also covered House's song "Death Letter" on their follow-up album, De Stijl. Looking back on their debut during a 2003 interview with Guitar Player, Jack said, "I still feel we've never topped our first album. It's the most raw, the most powerful, and the most Detroit-sounding record we've made."[28] AllMusic said of the album: "Jack White's voice is a singular, evocative combination of punk, metal, blues, and backwoods while his guitar work is grand and banging with just enough lyrical touches of slide and subtle solo work... Meg White balances out the fretwork and the fretting with methodical, spare, and booming cymbal, bass drum, and snare... All D.I.Y. punk-country-blues-metal singer-songwriting duos should sound this good."[23]

2000–2002: De Stijl and White Blood Cells

[edit]

The White Stripes released "Hand Springs" as a 7" split single with fellow Detroit band the Dirtbombs on the B-side in 2000; it was recorded in late 1999. Several copies came free with the pinball fanzine Multiball.[29] Jack and Meg divorced in March of that same year.[30] The White Stripes were scheduled to perform at a local music lounge soon after they separated. Jack assumed the band was over and asked Buick and nephew Ben Blackwell to perform with him in the slot that had been booked for the White Stripes. However, the day they were supposed to perform, Meg convinced Jack that the White Stripes should continue and the band reunited.[31]

The White Stripes' second album, De Stijl (Dutch for "The Style"), was released on the Sympathy for the Record Industry label on June 20, 2000.[32] The songs were recorded on an 8-track analog tape in Jack's living room,[33][34] De Stijl displays the simplicity of the band's blues and "scuzzy garage rock" fusion prior to their breakthrough success.[35][36] The album title derives from the Dutch art movement of the same name;[35] common elements of the De Stijl aesthetic are demonstrated on the album cover, which sets the band members against an abstract background of rectangles and lines in red, black and white.[26] The album was dedicated to furniture designer and architect Gerrit Rietveld of the De Stijl movement, as well as to the influential Georgia bluesman Blind Willie McTell.[37] De Stijl eventually reached number 38 on Billboard Magazine's Independent Albums chart in 2002, around the time the White Stripes' popularity began establishing itself. One New York Times critic at the time said that the Stripes typified "what many hip rock fans consider real music."[38]

Party of Special Things to Do was released as a 7" on Sub Pop in December 2000.[39] It comprised three songs originally performed by Captain Beefheart, an experimental blues rock musician.[40]

The White Stripes' third album, White Blood Cells, was released on July 3, 2001, on Sympathy for the Record Industry.[41] The band enjoyed its first significant success the following year with the major label re-release of the album on V2 Records.[42][43] Its stripped-down garage rock sound drew critical acclaim in the UK,[44] and in the US soon afterward, making the White Stripes one of the most acclaimed bands of 2002.[15][42] Several outlets praised their "back to basics" approach.[45][46] After their first appearance on network TV (a live set on The Late Late Show With Craig Kilborn), Joe Hagan of The New York Times declared, "They have made rock rock again by returning to its origins as a simple, primitive sound full of unfettered zeal."[47]

White Blood Cells peaked at number 61 on the Billboard 200, reaching Gold record status by selling over 500,000 albums. It reached number 55 in the United Kingdom,[48] being bolstered in both countries by the single "Fell in Love with a Girl" and its accompanying Lego-animation music video directed by Michel Gondry.[49] The video won three awards at the 2002 MTV Video Music Awards: Breakthrough Video, Best Special Effects, and Best Editing, and the band played the song live at the event.[12] It was also nominated for Video of the Year, but fell short of winning.[50] It also spawned the acclaimed singles "Hotel Yorba", "Dead Leaves and the Dirty Ground", and "We're Going to Be Friends".[51] Stylus Magazine rated White Blood Cells as the fourteenth greatest album of 2000–2005,[52] while Pitchfork ranked it eighth on their list of the top 100 albums from 2000 to 2004.[53]

In 2002, George Roca produced and directed a concert film about the band titled Nobody Knows How to Talk to Children.[54] It chronicles the White Stripes' four-night stand at New York City's Bowery Ballroom in 2002, and contains live performances and behind-the-scenes footage. Its 2004 release was suppressed by the band's management, however, after they discovered that Roca had been showing it at the Seattle Film Festival without permission.[55] According to the band, the film was "not up to the standards our fans have come to expect";[55] even so, it remains a highly prized bootleg.[56] Also in 2002, they appeared as musical guests on Saturday Night Live.[57]

2003–2006: Elephant and Get Behind Me Satan

[edit]The White Stripes' fourth album, Elephant, was recorded in 2002 over the span of two weeks with British recording engineer Liam Watson at his Toe Rag Studios in London.[58] Jack self-produced the album with antiquated equipment, including a duct-taped 8-track tape machine and pre-1960s recording gear.[58] In a 2017 interview with The New Yorker, Jack said "We had no business being in the mainstream. We assumed the music we were making was private, in a way. We were from the scenario where there are fifty people in every town. Something about us was beyond our control, though. Now it's five hundred people, now it's a second night, what is going on? Is everybody out of their minds?"[24] Promotional work for the album was postponed after Meg broke her wrist in New York.[59] Elephant was released in 2003 on V2 in the US, and on XL Recordings in England.[24][60] It marked the band's major label debut and was their first UK chart-topping album, as well as their first US Top 10 album (at number six).[24] The album eventually reached double platinum certification in Britain,[61] and platinum certification in the United States.[62] To promote the album, they made several appearances on Late Night with Conan O'Brien in 2003, and they collaborated with Conan O'Brien frequently afterwards.[63]

Elephant garnered critical acclaim upon its release.[15] It received a perfect five-out-of-five-star rating from Rolling Stone magazine, and enjoys a 92-percent positive rating on Metacritic.[64][65] AllMusic said the album "sounds even more pissed-off, paranoid, and stunning than its predecessor... Darker and more difficult than White Blood Cells."[66] Elephant was notable for Jack's first guitar solos and Meg's first leading vocal performance on "In the Cold, Cold Night";[67] critics also praised Meg's drumming.[68][69] Rolling Stone placed Jack at number 17 on its list of "100 Greatest Guitarists of All Time" and included Meg on its list of the "100 Greatest Drummers of All Time".[70][71] Elephant was ranked number 390 on the magazine's list of the 500 Greatest Albums of All Time.[72] In 2009, the album came in at number 18 in NME's "Top 100 Greatest Albums of the decade". NME referred to the album as the pinnacle of the White Stripes' time as a band and one of Jack White's best works of his career.[73][74]

The album's first single, "Seven Nation Army", was the band's most successful and topped the Billboard rock charts.[75] Its success was followed with a cover of Burt Bacharach's "I Just Don't Know What to Do with Myself". The album's third single was the successful "The Hardest Button to Button".[76] "There's No Home for You Here" was the fourth single. In 2004, the album won a Grammy for Best Alternative Music Album, while "Seven Nation Army" won a Grammy for Best Rock Song.[77] Also in 2004, the band released its first music film Under Blackpool Lights, which was shot entirely on super 8 film and was directed by Dick Carruthers.[78][79]

In 2005, Jack began working on songs for the band's next album at his home.[80] He played with different techniques than in past albums, trading in his electric guitar for an acoustic on all but a few of the tracks, as his trademark riff-based lead guitar style is overtaken by a predominantly rhythmic approach.[81] The White Stripes' fifth album, Get Behind Me Satan, was released in 2005 on the V2 label.[82] The title is an allusion to a Biblical quotation Jesus made to the Apostle Simon Peter from the Gospel of Matthew 16:23 of the New Testament (in the King James Version, the quotation is slightly different: "Get thee behind me, Satan"[83]). Another theory about this title is that Jack and Meg White read James Joyce's story collection "Dubliners" (published 1914) and used a line from the story "Grace" to title this album. The title is also a direct quotation from Who bassist John Entwistle's solo song "You're Mine".

With its reliance on piano-driven melodies and experimentation with marimba on "The Nurse" and "Forever For Her (Is Over For Me)", Get Behind Me Satan did not feature the explicit blues and punk styles that dominated earlier White Stripes albums.[84] However, despite this, the band was critically lauded for their "fresh, arty reinterpretations of their classic inspirations."[82] It has garnered positive reactions from fans, as well as critical acclaim, receiving more Grammy nominations as well as making them one of the must-see acts of the decade.[85][86] Rolling Stone ranked it the third best album of the year[87] and it received the Grammy for Best Alternative Music Album in 2006.

Three singles were released from the album, the first being "Blue Orchid", a popular song on satellite radio and some FM stations.[88][89] The second and third singles were "My Doorbell" and "The Denial Twist", respectively, and music videos were made for the three singles. "My Doorbell" was nominated for Best Pop Performance by a Duo or Group with Vocal.[90] The White Stripes postponed the Japanese leg of their world tour after Jack strained his vocal cords, with doctors recommending that Jack not sing or talk for two weeks.[91] After a full recovery, he returned to the stage in Auckland, New Zealand to headline the Big Day Out tour.[82][92] While on the British leg of the tour, Jack changed his name from Jack White to "Three quid".[93]

On October 12, 2004, Jim Diamond—the owner and operator of Ghetto Recorders recording studio—filed a lawsuit against the band and Third Man Records for "breach of contract".[94] In the suit, he claimed that as the co-producer, mixer, and editor on the band's debut album, and mixer and engineer on De Stijl, he was due royalties for "mechanical rights".[94][95] The band filed a counterclaim on May 16, 2005, requesting damages against Diamond and an official court declaration denying him rights to the material.[94] Diamond lost the suit on June 15, 2006, with the jury determining that he was not instrumental in crafting the band's sound.[95][96] The White Stripes released a cover version of Tegan and Sara's song "Walking with a Ghost" on iTunes in November 2005. The song was later released in December as the Walking with a Ghost EP featuring four other live tracks.[97]

In October 2006, it was announced on the official White Stripes website that there would be an album of avant-garde orchestral recordings consisting of past music written by Jack called Aluminium. The album was made available for pre-order on November 6, 2006, to great demand from the band's fans; the LP version of the project sold out in a little under a day. The project was conceived by Richard Russell, founder of XL Recordings, who co-produced the album with Joby Talbot.[98] It was recorded between August 2005 and February 2006 at Intimate Studios in Wapping, London using an orchestra. Before the album went out of print, it was available exclusively through the Aluminium website in a numbered limited edition of 3,333 CDs with 999 LPs.[99]

2007–2008: Icky Thump and hiatus

[edit]

On January 12, 2007, V2 Records announced that, due to being under the process of reconstruction, it would no longer release new White Stripes material, leaving the band without a label.[100] However, as the band's contract with V2 had already expired, on February 12, 2007, it was confirmed that the band had signed a single album deal with Warner Bros. Records.[101][102] Their sixth album, Icky Thump, was released on June 19, 2007.[49][103] Following the well-received Get Behind Me Satan, Icky Thump marked a return to the punk, garage rock and blues influences for which the band is known.[49] It was recorded at Blackbird Studio in Nashville and took almost three weeks to record—the longest of any White Stripes album. It would also be their first album with a title track. The album's release came on the heels of a series of concerts in Europe and one in North America at Bonnaroo.[104][105] Prior to the album's release, three tracks were previewed to NME: "Icky Thump", "You Don't Know What Love Is (You Just Do as You're Told)" and "Conquest". NME described the tracks as "an experimental, heavy sounding 70s riff", "a strong, melodic love song" and "an unexpected mix of big guitars and a bold horn section", respectively.[106]

On the US Billboard Charts dated May 12, 2007, "Icky Thump"—the first single—became the band's first Top 40 single, charting at number 26, and later charted at number 2 in the UK. Icky Thump entered the UK Albums Chart at number one,[107] and debuted at number two on the Billboard 200 with 223,000 copies sold.[107][108] By late July, Icky Thump was certified gold in the United States. As of March 8, 2008, the album has sold 725,125 copies in the US. On February 10, 2008, the album won a Grammy Award for Best Alternative Music Album.

On April 25, 2007, the duo announced that they would embark on a tour of Canada, performing in all 10 provinces, plus Yukon, Nunavut and Northwest Territories. In the words of Jack: "Having never done a tour of Canada, Meg and I thought it was high time to go whole hog. We want to take this tour to the far reaches of the Canadian landscape. From the ocean to the permafrost. The best way for us to do that is ensure that we perform in every province and territory in the country, from the Yukon to Prince Edward Island. Another special moment of this tour is the show which will occur in Glace Bay, Nova Scotia on July 14, the White Stripes' Tenth Anniversary." Canadian fiddler Ashley MacIsaac opened for the band at the Savoy Theatre, Glace Bay show; earlier in 2007, MacIsaac and Jack had discovered that they were distantly related.[109] It was also at this time that White learned he was related to Canadian fiddle player Natalie MacMaster.[110]

On June 24, 2007, just a few hours before their concert at Deer Lake Park, the White Stripes began their cross-Canada tour by playing a 40-minute set for a group of 30 kids at the Creekside Youth Centre in Burnaby. The Canadian tour was also marked by concerts in small markets,[13] such as Glace Bay, Whitehorse and Iqaluit, as well as by frequent "secret shows" publicized mainly by posts on The Little Room, a White Stripes fan messageboard. Gigs included performances at a bowling alley in Saskatoon, a youth center in Edmonton, a Winnipeg Transit bus and The Forks park in Winnipeg, a park in Whitehorse, the YMCA in downtown Toronto, the Arva Flour Mill in Arva, Ontario,[13] and Locas on Salter (a pool hall) in Halifax, Nova Scotia. They also played a historic one-note show on George Street in St. John's, Newfoundland, in an attempt to break a Guinness World Record for the shortest concert.[111] It was inducted briefly in 2009, but was discontinued the following year.[112] Media publications have continued to call it the shortest concert.[113][114] They played a full show later that night at the Mile One Centre in downtown St. John's.[113] Video clips from several of the secret shows have been posted to YouTube.[115] As well, the band filmed its video for "You Don't Know What Love Is (You Just Do as You're Told)" in Iqaluit.

After the conclusion of the Canadian dates, they embarked on a brief US leg of their tour, which was to be followed by a break before more shows in the fall.[13] But before their last show—in Southaven, Mississippi—Ben Blackwell (Jack's nephew and the group's archivist) says that Meg approached him and said, "This is the last White Stripes show". He asked if she meant of the tour, but she responded, "No. I think this is the last show, period."[13] On September 11, 2007, the band announced the cancellation of 18 tour dates due to Meg's struggle with acute anxiety.[91] A few days later, the duo canceled the remainder of their 2007 UK tour dates as well.[116] In his review of Under Great White Northern Lights for Vanity Fair, Bill Bradley commented on the tour cancellations, saying that it was "impossible" not to see Meg as "road-weary and worn-out" at the end of the film.[117]

The band was on hiatus from late 2007 to early 2011. While on hiatus, Jack formed a group called the Dead Weather, although he insisted that the White Stripes remained his top priority.[118] Dominique Payette, a Quebecois radio host, sued the band for $70,000 in 2008 for sampling 10 seconds of her radio show in the song "Jumble Jumble" without permission.[119] The matter was ultimately settled out of court.[120] In early 2008, the band released limited-edition Holga cameras stylized around Jack and Meg.[121]

2009–2011: Final years and breakup

[edit]The White Stripes performed live for the first time since September 2007 on the final episode of Late Night with Conan O'Brien on February 20, 2009, where they performed an alternate version of "We're Going to Be Friends".[122][123][124] In an article dated May 6, 2009, with MusicRadar.com, Jack mentioned recording songs with Meg before the Conan gig had taken place, saying, "We had recorded a couple of songs at the new studio." About a new White Stripes album, Jack said, "It won't be too far off. Maybe next year." Jack also explained Meg's acute anxiety during the Stripes' last tour, saying, "I just came from a Raconteurs tour and went right into that, so I was already full-speed. Meg had come from a dead-halt for a year and went right back into that madness. Meg is a very shy girl, a very quiet and shy person. To go full-speed from a dead-halt is overwhelming, and we had to take a break."[125] The Conan gig proved to be their final live performance as a band.

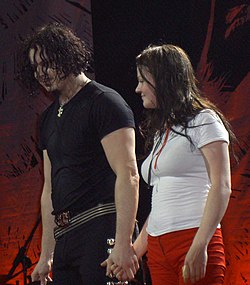

In 2009 Jack reported that the White Stripes were working on their seventh album.[126][127] A concert film, Under Great White Northern Lights, premiered at the Toronto International Film Festival on September 18, 2009.[128][129][130] The film documents the band's summer 2007 tour across Canada and contains live concert and off-stage footage.[131] Jack and Meg White appeared at the premiere and made a short speech before the movie started about their love of Canada and why they chose to debut their movie in Toronto.[132] The tour was in support of the album Icky Thump, and they performed in every province.[133] Jack conceived the idea of touring Canada after learning that Scottish relatives on his father's side had lived for a few generations in Nova Scotia before relocating to Detroit to work in the car factories.[134] Additionally, their 10th anniversary occurred during the tour on the day of their show at the Savoy Theatre in Glace Bay, Nova Scotia,[133] and in this shot, Jack and Meg are dancing at the conclusion of the concert. The film was directed by a friend of the duo, Emmett Malloy.[135]

In an interview with Self Titled, Jack alluded to the creation of a White Stripes film, Under Nova Scotian Lights, to be released later in 2009.[136] In an interview with contactmusic.com, Jack claimed that working with the White Stripes would be "strange". "It would definitely be strange to go into the White Stripes again and have to rethink my game," adding: "But that would be the best thing about it, because it would be a whole new White Stripes."[137]

In February 2010, a Super Bowl ad by the US Air Force Reserve caused the White Stripes to "take strong insult and objection to the Air Force Reserve presenting this advertisement with the implication that we licensed one of our songs to encourage recruitment during a war that we do not support."[138] In November 2010, the White Stripes contributed a previously released cover version of the song "Rated X" to the compilation album Coal Miner's Daughter: A Tribute To Loretta Lynn.[139] In late 2010, the White Stripes reissued their first three albums on Third Man Records on a 180-gram vinyl along with 500 limited-edition, "split-colored" records to accompany it.[140][141] Jack hinted at a possible White Stripes reunion in a 2010 interview with Vanity Fair. He said, "We thought we'd do a lot of things that we'd never done: a full tour of Canada, a documentary, coffee-table book, live album, a boxed set ... Now that we've gotten a lot of that out of our system, Meg and I can get back in the studio and start fresh."[142]

On February 2, 2011, the duo announced that they had officially ceased recording and performing music as the White Stripes. The announcement specifically denied any artistic differences or health issues, but cited "a myriad of reasons ... mostly to preserve what is beautiful and special about the band".[143][144]

Post-breakup

[edit]

Following the band's breakup, Jack continued his music career while Meg retired and returned to Detroit.[145] In a 2014 interview, Jack told Rolling Stone that Meg's emotionally reserved nature had been a source of tension when the duo was together, as she had little to say about the band's success. He spoke positively, however, of her musical acumen, saying "She was the antithesis of a modern drummer. So childlike and incredible and inspiring. All the not-talking didn't matter, because onstage? Nothing I do will top that." He also said that he believes a reunion is unlikely.[146]

Several unreleased recordings and memorabilia of the band have been released through Third Man, typically through the Third Man Records Vault, a "rarity-excavating" quarterly subscription service.[147] This began with a 2009 package that included a mono mix of Icky Thump. The latest package is 2023's Elephant XX, a mono mix of the aforementioned album which celebrates its 20th anniversary.[148][149] In 2016, the previously unheard "City Lights" was released as a promotional single after Michel Gondry surprised Jack with a music video.[150] It was additionally featured on Jack's compilation album Acoustic Recordings 1998–2016 and received a nomination for Best American Roots Song at the 59th Annual Grammy Awards.[151][152]

During the campaigning for the 2016 United States presidential election, then Republican candidate Donald Trump used "Seven Nation Army" in a campaign video against the Stripes' wishes. Jack and Meg made a joint post on the White Stripes Facebook page, stating that they were "disgusted by this association, and by the illegal use of their song" and that they had "nothing whatsoever to do with this video".[153] They also released a limited edition T-shirt that read "Icky Trump" on the front.[154][155]

On October 6, 2020, a greatest hits album titled The White Stripes Greatest Hits was announced through Third Man not as a vault exclusive.[156] It consists of twenty-six songs including "Ball and Biscuit" which was released as a promotional single.[157][158] The band relaunched their Instagram account to promote the album.[159] It was released in the United States by Third Man and Columbia Records on December 4, 2020,[160][156] and was internationally released on February 26, 2021.[161][162] Wartella-directed music videos for "Let's Shake Hands" and "Apple Blossom" were released simultaneously.[163][164] AllMusic's Heather Phares wrote: "The White Stripes Greatest Hits is filled with the same detail, wit, and willingness to subvert expectations that made the band so dynamic when they were active ... the collection's hand-curated feel is much more personal than the average best-of or streaming play list."[165] The New Yorker's Amanda Petrusich called the album "a good reminder of how odd and inventive the band was ... It feels old-fashioned, even deliberately so, but it sounds awfully good."[166]

In May 2023, Third Man Books announced The White Stripes Complete Lyrics 1997-2007, a book featuring lyrics written during the band's activity in addition to rough drafts and unseen content.[167][168] When compiling the lyrics, Jack said that "I couldn't get through any of those songs; I would cry halfway through each of those songs... some of them are the first songs I really had ever written, or among the earliest... humbly, I don't really know why anyone would get anything out of them... but people reflect back at you and keep mentioning that and you go 'OK, I guess people are getting something out of that.'"[169] It was released in October of that same year.[170][171] Also in 2023, in their first year of eligibility, the White Stripes were nominated for the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame but were not inducted.[172]

The Trump campaign again used "Seven Nation Army" during the 2024 United States presidential election,[173][174] which resulted in Jack and Meg filing a copyright infringement lawsuit in September 2024.[175][176][177][178] Their complaint accuses Trump of "flagrant misappropriation" and clarifies that they "vehemently oppose the policies adopted and actions taken by Defendant Trump when he was President and those he has proposed for the second term he seeks".[179][180] The lawsuit was dropped in November 2024.[181]

In January 2025, the White Stripes were nominated a second time for the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame.[182] Andy Greene of Rolling Stone remarked that the chances of a reunion were slim due to Meg retreating from the music industry and media, and wrote, "Let's hope that Meg at least watches the Disney+ livestream and smiles when the White Stripes are inducted. Great moments don't always need to play out in public. And Meg White doesn't owe us anything."[183] In November of that same year, they were inducted by Iggy Pop into the hall of fame.[184][185] Meg did not attend the ceremony; Jack accepted the award for the band and gave a speech written by him and Meg. He said, "she said she's very sorry she couldn't make it tonight, but she's very grateful for the folks who have supported her throughout all the years, it really means a lot to her tonight."[186] He also read a poem dedicated to her.[187]

Artistry

[edit]Influences

[edit]The White Stripes were influenced by blues musicians including Son House, Blind Willie McTell and Robert Johnson, garage rock bands such as the Gories and the Sonics,[188] the Detroit protopunk sound of bands like the MC5 and the Stooges, in addition to groups like the Cramps, the Velvet Underground, and the early Los Angeles punk blues band the Gun Club. Jack has stated on numerous occasions that the blues is the dominant influence on his songwriting and the roots of the band's music, stating that he feels it is so sacred that playing it does not do it justice. Of the Gun Club's music in particular, Jack said, "'Sex Beat', 'She's Like Heroin to Me', and 'For the Love of Ivy'...why are these songs not taught in schools?"[189] Heavy blues rock bands such as AC/DC and Led Zeppelin have also influenced the band, as Jack has claimed that he "can't trust anybody who doesn't like Led Zeppelin."[190]

Traditional country music such as Hank Williams and Loretta Lynn,[4] rockabilly acts like the Flat Duo Jets,[4] Wanda Jackson and Gene Vincent, the surf rock of Dick Dale, and folk music like Lead Belly and Bob Dylan have also influenced the band's sound.[191] Meg has said one of her all-time favorite musicians is Bob Dylan;[192] Jack has performed live with him, and has claimed "I've got three fathers—my biological dad, God and Bob Dylan".[193] In his acceptance speech for the band's induction into the Rock 'n' Roll Hall of Fame in 2025, Jack also paid tribute to Pavement, Jethro Tull, The Damned and Emerson, Lake & Palmer among many others.[194]

Equipment

[edit]With few exceptions, Jack displayed a continued partiality towards amps and pedals from the 1960s.[42] Jack used a number of effects to create his sound, such as a DigiTech Whammy IV to reach pitches that would be otherwise impossible with a regular guitar.[195] When performing live, Jack used a Randy Parsons custom guitar, a 1964 JB Hutto Montgomery Airline, a Harmony Rocket, a 1970s Crestwood Astral II, and a 1950s Kay Hollowbody. Also, while playing live, he used an MXR Micro Amp, Electro-Harmonix Big Muff Pi distortion/sustainer, and an Electro-Harmonix POG (a polyphonic octave generator). He also used a Boss TU-2 tuner pedal. He plugged this setup into a 1970s Fender Twin Reverb, and two 100-Watt Sears Silvertone 1485 amplifiers paired with two 6x10 Silvertone cabinets.[196] In addition to standard guitar tuning, Jack also used several open tunings. He also played other instruments such as a black F-Style Gibson mandolin, Rhodes bass keys, and a Steinway piano. He played a Musser M500 grand concert marimba on "The Nurse", "Forever for Her (Is Over for Me)". He played a custom-made red and white Musser M250 grand concert marimba for the Get Behind Me Satan tour.[197][198]

Meg extensively used the Ludwig Classic Maple kit with Paiste cymbals,[199][200] and also used Remo and Ludwig drumheads, various percussion instruments and Vater drumsticks. From the band's inception to Get Behind Me Satan, the resonant heads of the toms and bass drum featured peppermint swirls.[201][202][203] While recording From the Basement: The White Stripes, the design on the bass drum was switched to an image of her hand holding the apple from the Get Behind Me Satan cover. Beginning in 2006, White used a pair of Paiste 14" Signature Medium Hi-Hats, a 19" Signature Power Crash, and a 22" 2002 Ride.[201][204] On the Icky Thump tour, the bass drum head design was switched to a button inspired by the Pearlies clothing Jack and Meg wore for the album cover.

Style and technique

[edit]The White Stripes have been described as garage rock,[205][206] blues rock,[205] alternative rock,[206] punk blues,[207] and indie rock.[208] They emerged from Detroit's active garage rock revival scene of the late 1990s and early 2000s.[12] Their contemporaries included bands such as the Von Bondies, the Dirtbombs, the Detroit Cobras, and other bands that Jack included on a compilation album called Sympathetic Sounds of Detroit, which was recorded in his living room.[12]

The White Stripes were notable for having only two musicians, limiting the instruments they could play live, and lack of a bass player.[26][209] Jack, the principal writer, said that this was not a problem, and that he "always centered the band around the number three. Everything was vocals, guitar and drums or vocals, piano and drums."[4] Meg herself said that it was "difficult just being two people" but she was comfortable nonetheless.[210] Fans and critics drew comparisons between Jack's prowess on the guitar and Meg's simplistic, reserved drumming.[38] The band additionally drew attention for their preference for antiquated recording equipment. In a 2001 New York Times concert review, Ann Powers noted that Jack's "ingenious" playing was "constrained by [Meg's] deliberately undeveloped approach", and that "he created more challenges by playing an acoustic guitar with paper taped over the hole and a less-than-high-quality solid body electric."[38]

Meg's minimalistic drumming style was a prominent part of the band's sound. Meg never had formal drum lessons. She played Ludwig Drums with Paiste cymbals, and says her pre-show warm-up consisted of "whiskey and Red Bull".[211] Jack downplayed criticisms of her style, insisting: "I never thought 'God, I wish Neil Peart was in this band.' It's kind of funny: When people critique hip hop, they're scared to open up, for fear of being called racist. But they're not scared to open up on female musicians, out of pure sexism. Meg is the best part of this band. It never would have worked with anybody else, because it would have been too complicated... It was my doorway to playing the blues."[4] Of her playing style, Meg herself said: "I appreciate other kinds of drummers who play differently, but it's not my style or what works for this band. I get [criticism] sometimes, and I go through periods where it really bothers me. But then I think about it, and I realize that this is what is really needed for this band. And I just try to have as much fun with it as possible ... I just know the way [Jack] plays so well at this point that I always know kind of what he's going to do. I can always sense where he's going with things just by the mood he's in or the attitude or how the song is going. Once in a while, he throws me for a loop, but I can usually keep him where I want him."[211]

Although Jack was the lead vocalist, Meg did sing lead vocals for "In the Cold, Cold Night" (from Elephant)[195] and "Passive Manipulation" (from Get Behind Me Satan) among other tracks. She also accompanied Jack on the songs "Your Southern Can Is Mine" from De Stijl, "Hotel Yorba" and "This Protector" from White Blood Cells, "Rated X",[212] "You Don't Know What Love Is (You Just Do as You're Told)" and "Rag & Bone" from Icky Thump,[213] and accompanied Jack and Holly Golightly on the song "It's True That We Love One Another" from Elephant.[214]

Several White Stripes recordings were completed rapidly. White Blood Cells was recorded in less than four days, and Elephant and Get Behind Me Satan were both recorded in about two weeks.[215][216][210] For live shows, the White Stripes were known for Jack's employment of heavy distortion, as well as audio feedback and overdrive. The duo performed considerably more recklessly and unstructured live, never preparing set lists for their shows, believing that planning too closely would ruin the spontaneity of their performances.[217] Other affectations included Jack using two microphones onstage.[38]

Public image

[edit]Aesthetic and presentation

[edit]Jack explained the origin of the band's name: "Meg loves peppermints, and we were going to call ourselves the Peppermints. But since our last name was White, we decided to call it the White Stripes. It revolved around this childish idea, the ideas kids have—because they are so much better than adult ideas, right?"[218][219]

Early in their career, the band provided various descriptions of their relationship. Jack claimed that he and Meg were siblings, the youngest two of ten.[12][220][221] As the story went, they became a band when, on Bastille Day 1997, Meg went to the attic of their parents' home and began to play on Jack's drum kit.[12] This claim was widely believed and repeated despite rumors that they were, or had been, husband and wife.[222][223] In 2001, proof of their 1996 marriage emerged,[224][225] as well as evidence that the couple had divorced in March 2000, just before the band gained widespread attention.[226][227] Even so, they continued to insist publicly that they were brother and sister.[228] In a 2005 interview with Rolling Stone magazine, Jack claimed that this open secret was intended to keep the focus on the music rather than the couple's relationship: "When you see a band that is two pieces, husband and wife, boyfriend and girlfriend, you think, 'Oh, I see...' When they're brother and sister, you go, 'Oh, that's interesting.' You care more about the music, not the relationship—whether they're trying to save their relationship by being in a band."[229]

They made exclusive use of a red, white and black color scheme when conducting virtually all professional duties, from album art to the clothes worn during live performances.[4][24] Jack has explained that they used these colors to distract from the fact that they were young, white musicians playing "black music".[230] Early in their history, they turned down a potential deal with Chicago label Bobsled, because the label wanted to put its green logo on the CD.[13] He told Rolling Stone in 2005 that "The White Stripes' colors were always red, white, and black. It came from peppermint candy. I also think they are the most powerful color combination of all time, from a Coca-Cola can to a Nazi banner. Those colors strike chords with people. In Japan, they are honorable colors. When you see a bride in a white gown, you immediately see innocence in that. Red is anger and passion. It is also sexual. And black is the absence of all that."[4] He also explained that they aspired to invoke an innocent childishness without any intention of irony or humor.[12] Meg said that "like a uniform at school, you can just focus on what you're doing because everybody's wearing the same thing."[26] They also cited the minimalist and deconstructionist aspects of De Stijl design as a source of inspiration.[231] They also heavily used the number "three".[26]

The media and fans alike varied between intrigue and skepticism at the band's appearance and presentation. Andy Gershon, president of the V2 label at the time of their signing, was reluctant to sign them, saying, "They need a bass player, they've got this red-and-white gimmick, and the songs are fantastic, but they've recorded very raw...how is this going to be on radio?"[12] In a 2002 Spin magazine article, Chuck Klosterman wondered, "how can two media-savvy kids posing as brother and sister, wearing Dr. Seuss clothes, represent blood-and-bones Detroit, a city whose greatest resource is asphalt?"[12] However, in 2001, Benjamin Nugent with Time magazine commented that "it's hard to begrudge [Jack] his right to nudge the spotlight toward his band, and away from his private life, by any means available. Even at the expense of the truth."[232] Klosterman also commented that "his songs—about getting married in cathedrals, walking to kindergarten, and guileless companionship—are performed with an almost naive certitude."[233]

Film and television

[edit]The White Stripes selectively made media appearances, and were noted for their general refusal to be interviewed separately.[26][49] Jack and Meg appeared in Jim Jarmusch's film Coffee and Cigarettes in 2003,[234][235] in a segment entitled "Jack Shows Meg His Tesla Coil". This particular segment contains extensions of White Stripes motifs such as childhood innocence and Nikola Tesla.[236] They appeared in the 2005 documentary The Fearless Freaks, which covers the band the Flaming Lips.[237] The band appeared as themselves in The Simpsons episode "Jazzy and the Pussycats" in 2006.[238] Meg had previously expressed interest in a Simpsons role in 2003, saying that "A guest appearance would be amazing. I wouldn't want to be in a Lisa episode. They're kind of boring. Maybe a Homer one would be better."[239][240] Jack is one of three guitarists featured in the 2009 documentary It Might Get Loud, and Meg appears in segments that include the White Stripes.[241]

Legacy

[edit]

The critical and commercial success of the White Stripes has established Jack and Meg White as key figures of both the garage rock and indie rock revival of the 2000s.[6][242] Following the release of White Blood Cells, Daily Mirror dubbed them "the greatest band since The Sex Pistols"[243][244] and Rolling Stone magazine declared "Rock is Back!" on its September 2002 cover.[245] Subsequently christened by the media as the "The" bands, the White Stripes, along with the Strokes and the Hives, are credited by NME for bringing about both a "new garage rock revolution" and a "new rock revolution".[246][247] They were deemed "the saviours of rock 'n' roll" by Chris Smith.[248] Q magazine listed the White Stripes as one of "50 Bands to See Before You Die".[249] Alternative Press hailed the White Stripes and the Hives for expanding the legacy of garage rock.[250] Profiling the band in 2025, the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame wrote: "The White Stripes reimagined minimalist garage and punk rock for a new generation and brought blues into the twenty-first century. [...] They proved that a band could create massive, genre-defining sound with only two people, inspiring a wave of rock & roll revivalists and making a lasting mark on popular music."[251]

Established figures in the music industry have cited the White Stripes as an influence. Olivia Rodrigo is a fan of the band,[252] calling Elephant the record she listened to most,[253] Jack her "hero of all heroes",[254] and Meg "one of the best drummers of our time."[255] Beyoncé cited the White Stripes and Jack as influences on her 2024 album Cowboy Carter.[256] Nandi Bushell said the band "moved me at 5 years old to want to play the drums and still move me today!"[257] Dave Grohl of Foo Fighters and Nirvana called Meg "one of my favorite fucking drummers of all time. Like, nobody fucking plays the drums like that."[258] Tom Morello of Rage Against the Machine said that Meg "has style and swag and personality and oomph and taste and awesomeness that's off the charts and a vibe that's untouchable".[259] The White Stripes' songs have also been covered and sampled by several artists. Those who have sampled their works include Jermaine Dupri, Pitbull, Rizzle Kicks, Jurassic 5, and "Weird Al" Yankovic.[260] Those who have covered their works include Grohl, Arctic Monkeys,[261] Ryan Adams, Kelly Clarkson (accompanied by a marching band),[262] Bob Dylan, Wanda Jackson,[263] of Montreal, Tracey Thorn, the Flaming Lips, the Golden Filter, Bright Eyes, First Aid Kit, Bigga Haitian, and Wanda Jackson.[264]

Music by the White Stripes was used by British choreographer Wayne McGregor for his production Chroma, a piece he created for the Royal Ballet in London, England.[265][266] The orchestral arrangements for Chroma were commissioned by Richard Russell, head of XL Recordings, as a gift to the White Stripes and were produced by the British classical composer Joby Talbot. Three of these songs, "The Hardest Button to Button", "Aluminium" and "Blue Orchid", were first played to the band as a surprise in Cincinnati Music Hall, Ohio.[267][268] McGregor heard the orchestral versions and decided to create a ballet using the music. Talbot re-orchestrated the music for the Royal Opera House orchestra, also writing three additional pieces of his own composition. The world premiere of the ballet took place on November 16, 2006, at the Royal Opera House in Covent Garden, London. The ballet subsequently won the 2007 Laurence Olivier Award for Best New Dance Production.[269]

Several of the White Stripes' works have appeared in film, television, and advertising. The song "We're Going to Be Friends" appeared in the films Napoleon Dynamite in 2004, Wonder in 2017, and Mr. Harrigan's Phone in 2022.[270][271][272] The song "Instinct Blues" was used in the 2006 film The Science of Sleep.[273] The song "Why Can't You Be Nicer to Me?" was used in The Simpsons episode "Judge Me Tender" in 2010. The Academy Award-winning 2010 movie, The Social Network featured "Ball and Biscuit" in the opening scene.[274] The song "Icky Thump" was featured in the 2010 film The Other Guys, the 2021 film Zack Snyder's Justice League, and in a 2025 Dancing with the Stars performance by Robert Irwin and Witney Carson.[275][276][277][278] The song "Catch Hell Blues" is featured in the 2011 film Footloose, a remake of the 1984 film.[279][280] The song "Little Ghost" appears in the post credits scene for the 2012 Laika studios film, ParaNorman.[281] The songs "Hello Operator" and "Fell in Love with a Girl" were featured in the Academy Award-winning 2012 film Silver Linings Playbook.[282] In 2013, several songs by the White Stripes were featured in the first season of the television series Peaky Blinders.[283][284] The song "Apple Blossom" was featured in the 2015 Quentin Tarantino film The Hateful Eight.[285] The song "I Just Don't Know What to Do with Myself" was featured in a 2023 advertising campaign for Calvin Klein.[286]

Achievements

[edit]The White Stripes have sold over 8 million units in the US,[287][288] where they have one Multi-platinum album, one Platinum album, and three Gold albums, as well as one Multi-platinum single and one Platinum single.[288] In the UK, the White Stripes have one Multi-platinum album, two Platinum albums, four Gold albums, and two Silver albums, as well as one Multi-platinum single, one Gold single, and three Silver singles.[289] In Canada, the White Stripes have three Platinum albums and one Gold album, as well as one Multi-platinum single and one Gold single.[290]

The White Stripes were the recipients of a Brit Award,[291] six Grammy Awards,[77][292][293][294] one Meteor Music Award,[295] five MTV Video Music Awards,[296][297][298] one MTV Europe Music Award,[299] one MuchMusic Video Award,[300] and one NME Award.[301] They also broke a brief Guinness World Record in 2009 for the shortest concert.[112] They were nominated for the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame in 2023, their first year of eligibility, and inducted in 2025.[172][302]

The White Stripes have three albums on NME's "500 Greatest Albums of All Time" list: De Stijl at 395,[303] Elephant at 116,[304] and White Blood Cells at 77.[305][a] The Rock and Roll Hall of Fame placed White Blood Cells at 178 on their "Definitive 200 Albums of All Time" list.[306] White Blood Cells and Elephant appear on various editions of Rolling Stone's "500 Greatest Albums of All Time" list: on its 2012 edition, White Blood Cells ranked 497 and Elephant ranked 391;[307] on its 2020 edition, Elephant ranked 449.[308] Rolling Stone also included "Seven Nation Army" on their "250 Greatest Songs of the 21st Century So Far" list and multiple editions of their "500 Greatest Songs of All Time" list.[309][310][311] In 2025, The Guardian included "Seven Nation Army" on their list of defining events in popular culture of the 21st century.[312]

In 2015, Rolling Stone dubbed the White Stripes the sixth greatest duo of all time.[313] The same publication included Jack on its list of "The 100 Greatest Guitarists of All Time" in 2010, and Meg on its list of the "100 Greatest Drummers of All Time" in 2016.[314][71] In 2024, American Songwriter included the White Stripes on their list of the "Greatest (And Most Influential) Rock Music Duos Ever".[315] In 2025, Ultimate Classic Rock placed the band first on their list of "Top 20 American Rock Bands of the 2000s."[316]

Band members

[edit]- Jack White – vocals, guitar, keyboards, piano

- Meg White – drums, percussion, vocals

Discography

[edit]Studio albums

- The White Stripes (1999)

- De Stijl (2000)

- White Blood Cells (2001)

- Elephant (2003)

- Get Behind Me Satan (2005)

- Icky Thump (2007)

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ White Blood Cells is placed at 77, but is under the name De Stijl because of a misprint/typo.

References

[edit]- ^ Dunn 2009, p. 166.

- ^ Handyside 2004, p. 22.

- ^ Handyside 2004, p. 25.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Fricke, David (August 25, 2005). "White on White". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on February 24, 2015. Retrieved June 20, 2008.

- ^ White, Jack. Interview in It Might Get Loud, Sony Pictures Classics, 2008.

- ^ a b Leahey, Andrew. Jack White Biography at AllMusic. Retrieved October 10, 2014.

- ^ McCollum, Brian (September 2003), "Red, White, and Cool", Spin. 19(9):68–74

- ^ Handyside 2004, p. 31.

- ^ Brown, Jake (May 23, 2002). "White Stripes Marriage License". Glorious Noise. Archived from the original on May 10, 2016. Retrieved March 11, 2025.

- ^ Handyside 2004, p. 32.

- ^ Ivory, Jane (August 9, 2007). "Second Baby for Jack White and Karen Elson". Efluxmedia.com. Archived from the original on October 25, 2008. Retrieved September 10, 2008.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Klosterman, Chuck (Oct 2002). "The Garage", Spin. 18 (10):64–68

- ^ a b c d e f Eells, Josh (April 5, 2012). "Jack Outside the Box". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on November 1, 2016. Retrieved March 11, 2025.

- ^ Handyside, Chris. "The White Stripes: Biography". AllMusic. Archived from the original on January 15, 2012. Retrieved July 30, 2014.

- ^ a b c Leahey, Andrew. "The White Stripes". AllMusic. Archived from the original on January 15, 2012. Retrieved December 31, 2011.

- ^ Maron, Marc (June 18, 2012). "Episode 289 - Jack White". WTF with Marc Maron Podcast. Archived from the original on May 5, 2016. Retrieved March 11, 2025.

- ^ Coombe, Doug (April 30, 2008). "Motor City Cribs (Metro Times Detroit)". Metro Times. Archived from the original on May 2, 2008. Retrieved April 12, 2024.

- ^ Buick, Dave (January 3, 2008). "From Italy With Love". BlogSpot.com. Retrieved August 26, 2008.[dead link]

- ^ Coombe, Doug. "Motor City Cribs". Detroit Metro Times. Archived from the original on May 2, 2008. Retrieved August 26, 2008.

- ^ "Lafayette Blues". Archived from the original on June 7, 2011. Retrieved August 26, 2008.

- ^ Martin, Dan (October 21, 2010). "White Stripes single sells for more than £10,000". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved March 11, 2025.

- ^ Perry, Andrew (November 14, 2004). "The White Stripes uncut". www.theguardian.com. Observer Music Monthly. Retrieved March 11, 2025.

- ^ a b c Handyside, Chris. "The White Stripes". AllMusic.com. Retrieved August 26, 2008.

- ^ a b c d e Wilkinson, Alec (March 5, 2017). "Jack White's Infinite Imagination". The New Yorker. ISSN 0028-792X. Archived from the original on February 23, 2020. Retrieved March 11, 2025.

- ^ Sult, Ryan. "Jim Diamond". MotorCityRocks.com. Archived from the original on January 13, 2008. Retrieved August 26, 2008.

- ^ a b c d e f Cameron, Keith (September 8, 2005). "The Sweetheart Deal". The Guardian. London. Archived from the original on December 4, 2013. Retrieved October 23, 2008.

- ^ Strauss, Neil (August 1, 2002). "Too Much Too Soon". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on January 16, 2009. Retrieved October 23, 2008.

- ^ Fox, Darrin, "White Heat", Guitar Player, June 2003, p. 66

- ^ Sokol, Cara Giaimo and Zach (February 15, 2013). "The White Stuff: A Timeline of Almost Every Jack White Gimmick". Vice. Retrieved May 23, 2024.

- ^ Brown, Jake (June 9, 2002). "White Stripes Divorce Certificate". Glorious Noise. Archived from the original on August 26, 2019. Retrieved June 19, 2020.

- ^ Handyside, Chris (August 13, 2013). Fell in Love with a Band: The Story of The White Stripes. St. Martin's Publishing Group. ISBN 978-1-4668-5184-9.

- ^ Phares, Heather. "De Stijl Review". AllMusic.com. Archived from the original on January 16, 2012. Retrieved August 26, 2008.

- ^ Murfett, Andrew (June 15, 2007). "Stripes take on a modern slant". The Age. Archived from the original on November 5, 2012. Retrieved October 23, 2008.

- ^ Chute, Hillary (July 31, 2001). "Primary Colors". The Village Voice. Retrieved October 23, 2008.[dead link]

- ^ a b Eliscu, Jenny (February 15, 2001) "THE WHITE STRIPES". Rolling Stone. 862:65

- ^ Eliscu, Jenny (November 23, 2000). "De Stijl". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on February 20, 2025. Retrieved March 11, 2025.

- ^ "De Stijl". Barnes & Noble. Archived from the original on February 20, 2009. Retrieved August 26, 2008.

- ^ a b c d POWERS, ANN (February 27, 2001). "POP REVIEW; Intellectualizing the Music Or Simply Experiencing It Archived March 6, 2016, at the Wayback Machine". Retrieved August 29, 2014.

- ^ "White Stripes, The – Party Of Special Things To Do". discogs.com. December 5, 2000. Archived from the original on June 28, 2009. Retrieved August 30, 2008.

- ^ Barnes, Mike; Paytress, Mark; White III, Jack (March 2011). "The Black Rider". Mojo. Vol. 208. London: Bauermedia. pp. 65–73. Archived from the original on January 18, 2023. Retrieved May 23, 2024.

- ^ Heather Phares. "White Blood Cells – Review". AllMusic. Retrieved August 30, 2008.

- ^ a b c Hoard, Christian (2004). "White Stripes Biography". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on October 28, 2008. Retrieved October 23, 2008.

- ^ Hochman, Steve (November 18, 2001). "The White Stripes Take a Unique Major-Label Road". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on January 28, 2024. Retrieved January 28, 2024.

- ^ Branigan, Tania (August 7, 2001). "Britain's rock fans make stars of US White Stripes". The Guardian. Retrieved September 24, 2024.

- ^ "The White Stripes". whitestripes.net. Archived from the original on January 7, 2017. Retrieved August 30, 2008.

- ^ "White Stripes biography". tiscali.co.uk. Archived from the original on June 25, 2008. Retrieved August 30, 2008.

- ^ Hagan, Joe (August 12, 2001). "Hurling Your Basic Rock at the Arty Crowd". The New York Times. Archived from the original on March 6, 2016. Retrieved August 30, 2014.

- ^ "WHITE STRIPES | full Official Chart History | Official Charts Company". www.officialcharts.com. Retrieved April 7, 2023.

- ^ a b c d Pastorek, Whitney (May 25, 2007). "Changing Their Stripes". Entertainment Weekly. Vol. 935. pp. 40–44.

- ^ "2002 MTV Video Music Awards". MTV.com. Archived from the original on August 28, 2008. Retrieved October 23, 2008.

- ^ Petridis, Alexis (December 5, 2024). "Tall tales, campfire singalongs and Oldham slang: the White Stripes' 20 best songs – ranked!". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved January 31, 2025.

- ^ "The Top 50 Albums of 2000–2005". Stylus Magazine. Archived from the original on August 9, 2020. Retrieved October 23, 2008.

- ^ "The Top 100 Albums of 2000–04". Pitchfork. February 7, 2005. Retrieved September 10, 2011.

- ^ Gavin, Baker. "Nobody Knows How To Talk To Children – Full Documentary". glbracer. Archived from the original on February 1, 2014. Retrieved January 9, 2014 – via YouTube.

- ^ a b "White Stripes' News". whitestripes.com. December 20, 2004. Archived from the original on May 1, 2008. Retrieved August 30, 2008.

- ^ "Nobody Knows How to Talk to Children (2004)". IMDb.com. Retrieved August 30, 2008.

- ^ Shaffer, Claire (December 14, 2020). "The White Stripes Release Two Classic 'SNL' Performances Online". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on November 18, 2024. Retrieved June 28, 2024.

- ^ a b Fricke, David (April 17, 2003), "Living Color" Archived May 13, 2016, at the Wayback Machine. Rolling Stone. (920): 102

- ^ NME (March 10, 2003). "White Stripes get a break!". NME. Archived from the original on July 23, 2025. Retrieved July 23, 2025.

- ^ Heather Phares. "Elephant – Review". Allmusic. Archived from the original on April 29, 2023. Retrieved August 30, 2008.

- ^ "BPI". British Phonographic Industry. Archived from the original on December 30, 2007. Retrieved January 17, 2008.

- ^ RIAA Archived April 5, 2007, at the Wayback Machine Recording Industry Association of America.

- ^ "White Stripes will play four nights on Conan". EW.com. Retrieved June 28, 2024.

- ^ Fricke, David (March 25, 2003). "Elephant: White Stripes – Review". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on October 23, 2007. Retrieved August 30, 2008.

- ^ "The White Stripes: Elephant (2003): Reviews". metacritic.com. Archived from the original on August 4, 2008. Retrieved August 30, 2008.

- ^ Phares, Heather. "Elephant – Review". Allmusic. Archived from the original on April 29, 2023. Retrieved August 30, 2008.

- ^ Ratliff, Ben (April 21, 2003). "ROCK REVIEW; Contradictory and Proud of It". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on September 11, 2017. Retrieved January 21, 2024.

- ^ The White Stripes - Elephant Album Reviews, Songs & More | AllMusic, retrieved April 7, 2023

- ^ Billboard. Nielsen Business Media, Inc. March 29, 2003.

- ^ Townshend, Peter (August 27, 2003). "The 100 Greatest Guitarists of All Time". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on June 23, 2008. Retrieved August 30, 2008.

- ^ a b Weingarten, Christopher R.; Dolan, Jon; Diehl, Matt; Micallef, Ken; Ma, David; Smith, Gareth Dylan; Wang, Oliver; Heller, Jason; Runtagh, Jordan; Shteamer, Hank; Smith, Steve; Spanos, Brittany; Grow, Kory; Kemp, Rob; Harris, Keith; Gehr, Richard; Wiederhorn, Jon; Johnston, Maura; Greene, Andy (March 31, 2016). "100 Greatest Drummers of All Time". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on April 4, 2023. Retrieved April 7, 2023.

- ^ "The RS 500 Greatest Albums of All Time". Rolling Stone. November 18, 2003. Archived from the original on June 23, 2008. Retrieved August 30, 2008.

- ^ Reneshaw, David. "500 Greatest Songs (Seven Nation Army)". NME. No. July 2014.

- ^ "The Top 100 Greatest Albums of the Decade". NME.com. Archived from the original on March 6, 2010. Retrieved February 19, 2010.

- ^ "Billboard Top Rock Charts". Billboard. 2004.

- ^ "Ranked: The White Stripes' Greatest Hits". Rough Trade Blog. February 26, 2021. Retrieved April 7, 2023.

- ^ a b "Rock On The Net: 46th Annual Grammy Awards - 2004". www.rockonthenet.com. Archived from the original on February 18, 2013. Retrieved March 3, 2023.

- ^ Bradshaw, Peter (November 4, 2004). "The White Stripes Under Blackpool Lights". The Guardian. Retrieved June 24, 2019.

- ^ Murray, Noel (December 27, 2004). "The White Stripes: Under Blackpool Lights". The AV Club. Archived from the original on August 1, 2019. Retrieved June 24, 2019.

- ^ Fricke, David (2005). "White on White". Rolling Stone.

- ^ "The White Stripes: Get Behind Me Satan". Pitchfork. Archived from the original on January 24, 2024. Retrieved April 7, 2023.

- ^ a b c Phares, Heather. "Get Behind Me Satan – Review". AllMusic. Retrieved August 30, 2008.

- ^ Matthew: XVI:XXIII, King James Bible. Archived March 3, 2016, at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved June 20, 2008.

- ^ "The White Stripes: Get Behind Me Satan". Pitchfork. Archived from the original on January 24, 2024. Retrieved April 1, 2023.

- ^ Nicholson, Barry (2011). "White Out". NME New Musical Express.

- ^ Murphy, Matthew (June 6, 2005). "Get Behind Me Satan". Pitchfork. Archived from the original on January 15, 2008. Retrieved August 30, 2008.

- ^ Rolling Stone Magazine's Top 50 Records of 2005 Archived February 2, 2007, at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved on August 30, 2008.

- ^ Benson, Ian (June 30, 2015). "Jack White's Oddball Masterpiece: The White Stripes' last real hurrah". Alternative Press Magazine. Retrieved April 1, 2023.

- ^ Speed, Paul (October 8, 2021). "A Wild And Windy Night When The White Stripes Rocked The Heavens". The Riff. Archived from the original on April 1, 2023. Retrieved April 1, 2023.

- ^ "The Complete List of Grammy Nominations". The New York Times. December 8, 2005. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on May 3, 2015. Retrieved April 1, 2023.

- ^ a b (September 12, 2007), "White Stripes shelve US concerts" . BBC. Retrieved November 24, 2014.

- ^ sanchez, Lucas (November 6, 2005). "Jack White changes his name". NME. Archived from the original on April 27, 2019. Retrieved April 27, 2019.

- ^ NME (November 6, 2005). "Jack White changes his name". NME. Archived from the original on April 27, 2019. Retrieved May 23, 2024.

- ^ a b c Dietderich, Andrew (June 20, 2005), "Studio owner sues White Stripes over album royalties". Crain's Detroit Business. 21 (25):37

- ^ a b Harris, Chris (June 16, 2006), "White Stripes Win Royalties Lawsuit". MTV. Retrieved March 16, 2015.

- ^ Billboard Staff (June 15, 2005). "White Stripes Win Lawsuit Over Royalties". billboard.com. Billboard. Archived from the original on April 30, 2025. Retrieved April 1, 2025.

- ^ "The White Stripes: Walking With a Ghost EP". Pitchfork. Archived from the original on January 24, 2024. Retrieved April 9, 2024.

- ^ "White Stripes Meets Classical On 'Aluminium'". billboard.com. October 4, 2006. Retrieved August 30, 2008.

- ^ "White Stripes Go Orchestral On Aluminum". Glide Magazine. October 5, 2006. Archived from the original on November 25, 2011. Retrieved August 30, 2008.

- ^ Christman, Ed (January 12, 2007), "V2 Restructured, White Stripes, Moby Become Free Agents" Archived January 18, 2016, at the Wayback Machine. Billboard. Retrieved January 22, 2007.

- ^ Amy Phillips (February 12, 2007). "White Stripes Sign to Warner Bros". Pitchfork. Archived from the original on February 14, 2007. Retrieved February 12, 2007.

- ^ "NYLON – June/July 2007". nxtbook.com. Archived from the original on December 7, 2008. Retrieved August 30, 2008.

- ^ Heather Phares. "Icky Thump – Review". Allmusic. Retrieved August 30, 2008.

- ^ News page, The White Stripes website news Archived April 22, 2015, at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved April 10, 2007.

- ^ News page, The White Stripes website show list Archived April 22, 2015, at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved April 13, 2007.

- ^ "Exclusive – NME.COM hears new White Stripes songs". NME.COM. March 2, 2007. Archived from the original on November 21, 2008. Retrieved August 30, 2008.

- ^ a b "The White Stripes – Icky Thump global chart positions and trajectories" Archived October 12, 2014, at the Wayback Machine. aCharts.us. Retrieved June 30, 2007.

- ^ Hasty, Katie (June 27, 2007). "Bon Jovi Scores First No. 1 Album Since 1988". Billboard.com. Archived from the original on January 19, 2016.

- ^ "Halifax fans chase White Stripes around town". cbc.ca. CBC. July 14, 2007. Archived from the original on July 2, 2009.

- ^ Schneider, Jason. "The White Stripes: Manifest Destiny". Exclaim.ca. Archived from the original on October 15, 2007. Retrieved April 5, 2010.

- ^ Hopper, Alex (July 16, 2024). "On This Day: The White Stripes Play the Shortest Concert Ever". American Songwriter. Archived from the original on August 16, 2024. Retrieved August 16, 2024.

- ^ a b Glenday, Craig (2009). Guinness: World Records 2009. Guinness World Records. p. 168. ISBN 978-1904994374.

- ^ a b "And on that note, The White Stripes tour is over". CBC News. July 17, 2007. Archived from the original on June 3, 2016. Retrieved December 13, 2007.

- ^ "Guinness won't add Jack White's one-note concert as world's shortest". NBC News. May 17, 2012. Archived from the original on August 16, 2024. Retrieved August 16, 2024.

- ^ "Jack and Meg go back to school"[permanent dead link], The Globe and Mail, July 5, 2007.

- ^ (September 13, 2007), "The White Stripes cancel UK tour" . BBC. Retrieved November 24, 2014.

- ^ "Buy It, Steal It, Skip It: The White Stripes' Under Great White Northern Lights". Vanity Fair. March 15, 2010. Archived from the original on April 13, 2015. Retrieved February 20, 2024.

- ^ "Jack White Works With Bob Dylan". Ultimate-Guitar.Com. February 26, 2008. Archived from the original on August 28, 2008. Retrieved August 30, 2008.

- ^ NME New York staff (February 5, 2008), "White Stripes sued for sampling radio show" Archived March 5, 2016, at the Wayback Machine. NME. Retrieved March 16, 2015.

- ^ Schneider, Jason (April 30, 2012), "Jack White—The Third Man" Archived January 4, 2016, at the Wayback Machine. Exclaim!. Retrieved March 16, 2015.

- ^ Axline, Keith (February 19, 2008). "White Stripes Offer Custom Lomo Cameras". Wired. ISSN 1059-1028. Archived from the original on December 23, 2016. Retrieved June 15, 2025.

- ^ "Whitestripes.net". Archived from the original on September 28, 2011. Retrieved April 5, 2010.

- ^ "Late Night With Conan O'Brien's Last Music Guest: The White Stripes". Stereogum. February 11, 2009. Retrieved June 28, 2024.

- ^ "Conan O'Brien Tells Story of How the White Stripes Closed "Late Night": Listen". Pitchfork. October 12, 2017. Archived from the original on January 22, 2024. Retrieved March 28, 2024.

- ^ "Jack White on The White Stripes' future". MusicRadar.com. May 6, 2009. Archived from the original on March 10, 2012. Retrieved May 4, 2010.

- ^ "Meg White Surprises With Raconteurs In Detroit" Archived February 23, 2016, at the Wayback MachineBillboard.com. Retrieved on June 9, 2008.

- ^ "Delawareonline.com". February 11, 2009. Archived from the original on January 4, 2016. Retrieved April 5, 2010.

- ^ "Whitestripes.com". Archived from the original on April 21, 2010. Retrieved May 4, 2010.

- ^ Dehaas, Josh (July 22, 2009). "TIFF's documentary films observe an askew planet (ours)". Toronto Life. Archived from the original on January 28, 2024. Retrieved January 28, 2024.

- ^ "White Stripes Canadian tour doc to premiere at TIFF". Canadian Broadcasting Corporation (CBC). July 21, 2009. Archived from the original on January 28, 2024. Retrieved January 28, 2024.

- ^ "News Extra". Whitestripes.com. Archived from the original on April 3, 2010. Retrieved May 4, 2010.

- ^ "Q&A: Jack White, the sleepless songwriter". thestar.com. February 26, 2010. Retrieved April 1, 2023.

- ^ a b Schoepp, Trapper (March 15, 2010). "Jackpot Art Gallery to preview new White Stripes roc doc". UWM Post. p. 10.

- ^ Rayner, Ben (February 21, 2010). "Red, white and new—Seeing sights, wooing strangers". Toronto Star.

- ^ Hoard, Christian (April 1, 2010). "Under Great White Northern Lights". Rolling Stone. No. 1101. p. 75.

- ^ "Self Titledmag.com". Self-Titledmag.com. Archived from the original on February 6, 2010. Retrieved May 4, 2010.

- ^ "Jack White — Jack White's 'Strange' Stripes". Contactmusic.com. March 12, 2010. Archived from the original on March 15, 2010. Retrieved April 4, 2010.

- ^ "White Stripes battle US Air Force". BBC News. February 9, 2010. Archived from the original on February 12, 2010. Retrieved March 27, 2010.

- ^ Gold, Adam (September 9, 2010). "Forthcoming Loretta Lynn Tribute to Feature The White Stripes, Steve Earle, Lucinda Williams, Paramore & More | Nashville Cream". Nashvillescene.com. Archived from the original on November 25, 2011. Retrieved February 19, 2011.

- ^ Cooper, Peter. "Loretta Lynn, country music's iconic 'Coal Miner's Daughter,' dead at 90". The Tennessean. Retrieved April 1, 2023.

- ^ Evans, Greg (October 4, 2022). "Loretta Lynn Dies: Country Icon And Coal Miner's Daughter Was 90". Deadline. Archived from the original on April 1, 2023. Retrieved April 1, 2023.

- ^ "Jack White Vanity Fair Interview". Antiquiet.com. Archived from the original on November 15, 2010. Retrieved February 19, 2011.

- ^ Moody, Nekesa Mumbi (February 2, 2011). "The White Stripes Announce They're Breaking Up". ABC news. Retrieved February 2, 2011.

- ^ Cochrane, Greg (February 2, 2011). "White Stripes announce 'split' after 13 years together". BBC News. Archived from the original on February 26, 2014. Retrieved February 2, 2011.

- ^ Lacy, Eric (May 23, 2014). "Jack White says he 'almost never' talks to Meg White, says she's 'always been a hermit'". mlive. Retrieved July 16, 2024.

- ^ Rolling Stone (May 23, 2014). "Where's Meg White? Jack Speaks Out on Elusive White Stripes Partner". rollingstone.com. Archived from the original on December 14, 2018. Retrieved January 15, 2015.

- ^ McGovern, Kyle (January 3, 2013). "Jack White Spares 1999 Bowling Alley Gig for Third Man Vinyl Vault Series". Spin. Archived from the original on February 29, 2024. Retrieved July 16, 2024.

- ^ "The White Stripes' Elephant Gets New Mono Mix for 20th Anniversary". January 9, 2023. Archived from the original on January 11, 2025. Retrieved July 16, 2024.

- ^ "THIRD MAN RECORDS ANNOUNCES VAULT PACKAGE #55: THE WHITE STRIPES - ELE – Third Man Records – Official Store". thirdmanrecords.com. January 9, 2023. Archived from the original on August 14, 2024. Retrieved July 16, 2024.

- ^ Kreps, Daniel (September 12, 2016). "See Michel Gondry's Captivating Video for White Stripes' 'City Lights'". Rolling Stone. Retrieved July 16, 2024.

- ^ "Nominees And Winners | GRAMMY.com". February 1, 2012. Archived from the original on February 1, 2012. Retrieved July 16, 2024.

- ^ Levy, Joe (September 8, 2016). "Review: Jack White's 'Acoustic Recordings' Is a Genreless Foot Stomper". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on July 16, 2024. Retrieved July 16, 2024.

- ^ Krieg, Gregory (October 6, 2016). "The White Stripes give Trump an Icky Thump | CNN Politics". CNN. Archived from the original on September 12, 2024. Retrieved April 1, 2022.

- ^ "The White Stripes are now selling 'Icky Trump' t-shirts". Consequence. October 6, 2016. Archived from the original on June 21, 2021. Retrieved April 1, 2022.

- ^ "Anti Trump Unisex T Shirt". Third Man Store. October 6, 2016. Retrieved April 1, 2022.[permanent dead link]

- ^ a b "The White Stripes "Greatest Hits"". Third Man Records. Archived from the original on December 13, 2020. Retrieved December 13, 2020.

- ^ Minsker, Evan; Monroe, Jazz (October 6, 2020). "The White Stripes Announce Greatest Hits, Share Live Video". Pitchfork. Archived from the original on July 9, 2024. Retrieved July 10, 2024.

- ^ "The White Stripes Share Archival "Ball and Biscuit," Prep 'Greatest Hits' Compilation". Jambands. October 8, 2020. Retrieved July 10, 2024.

- ^ "The White Stripes Announce First-Ever Greatest Hits Album". October 6, 2020. Archived from the original on July 10, 2024. Retrieved July 10, 2024.

- ^ Minsker, Evan; Monroe, Jazz (October 6, 2020). "The White Stripes Announce Greatest Hits, Share Live Video". Pitchfork. Archived from the original on July 9, 2024. Retrieved July 8, 2024.

- ^ "The White Stripes Celebrate Global Greatest Hits Release With Premiere Of From The Basement Live Session – Sony Music Canada". www.sonymusic.ca. Retrieved July 8, 2024.

- ^ Sinclair, Paul (February 2, 2021). "Out This Week / on 26 February 2021". Superdeluxeedition.com. Archived from the original on June 13, 2024. Retrieved March 5, 2022.

- ^ Lavin, Will (December 5, 2020). "Watch The White Stripes' animated new video for 'Let's Shake Hands'". NME. Retrieved July 16, 2024.

- ^ Blistein, Jon (November 13, 2020). "White Stripes Soundtrack an Animated Love Story in Video for 'De Stijl' Classic 'Apple Blossom'". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on November 18, 2020. Retrieved July 16, 2024.

- ^ The White Stripes Greatest Hits - The White St... | AllMusic, archived from the original on October 10, 2024, retrieved July 11, 2024

- ^ Petrusich, Amanda (December 4, 2020). "Long Live the Greatest-Hits Album". The New Yorker. Archived from the original on December 8, 2020. Retrieved December 13, 2020.

- ^ Duran, Anagricel (May 4, 2023). "The White Stripes' lyrics collected for new book". NME. Archived from the original on July 16, 2024. Retrieved July 16, 2024.

- ^ "The White Stripes Entire Lyrics Are Compiled in a New Book". May 2, 2023. Archived from the original on July 16, 2024. Retrieved July 16, 2024.

- ^ "Jack White says new White Stripes lyrics book brought him to happy tears". The Oakland Press. October 19, 2023. Archived from the original on July 16, 2024. Retrieved July 16, 2024.

- ^ Hussey, Allison (May 2, 2023). "The White Stripes' Lyrics Collected in New Book". Pitchfork. Archived from the original on July 16, 2024. Retrieved July 16, 2024.

- ^ Baetens, Melody. "White Stripes release hardcover lyric book with rare rough drafts, essays and more". The Detroit News. Archived from the original on July 16, 2024. Retrieved July 16, 2024.

- ^ a b Unterberger, Andrew (May 3, 2023). "Snubs & Surprises in the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame's 2023 Inductions". Billboard. Retrieved January 28, 2024.

- ^ White, Jack (September 9, 2024). "This machine sues fascists". Instagram. Retrieved September 9, 2024.

- ^ Tinoco, Armando; Patten, Dominic (September 9, 2024). "Donald Trump Hit With White Stripes Lawsuit, As Promised — Update". Deadline. Archived from the original on September 9, 2024. Retrieved September 9, 2024.

- ^ Torres, Eric (September 9, 2024). "The White Stripes Sue Donald Trump". Pitchfork. Archived from the original on September 11, 2024. Retrieved September 11, 2024.

- ^ Levin, Bess (August 30, 2024). "You Can Add ABBA and the White Stripes to the Long List of Musical Acts Who Want Nothing to Do With Donald Trump". Vanity Fair. Archived from the original on September 9, 2024. Retrieved September 9, 2024.

- ^ Wile, Rob (September 10, 2024). "The White Stripes sue Trump for using 'Seven Nation Army' in a campaign video". www.nbcnews.com. Archived from the original on October 7, 2024. Retrieved September 10, 2024.

- ^ Specter, Emma (September 10, 2024). "Trump Has Made a Powerful New Legal Enemy, and It's...the White Stripes?". Vogue. Archived from the original on September 10, 2024. Retrieved September 11, 2024.

- ^ Wagmeister, Elizabeth (September 9, 2024). "The White Stripes sue Trump campaign over use of 'Seven Nation Army'". CNN. Archived from the original on December 1, 2024. Retrieved September 10, 2024.

- ^ Bohannon, Molly. "White Stripes Sue Trump For Using 'Seven Nation Army' In Campaign Video—Joining Complaints From These Artists". Forbes. Retrieved September 11, 2024.

- ^ Snapes, Laura (November 12, 2024). "The White Stripes drop lawsuit against Trump campaign for unauthorised Seven Nation Army use". The Guardian. Retrieved December 3, 2024.

- ^ "The White Stripes, Spinners nominated for Rock & Roll Hall of Fame". Detroit Free Press. Archived from the original on June 7, 2023. Retrieved January 28, 2024.