Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Erbil

View on Wikipedia

Key Information

| This article is part of a series on |

| Life in Kurdistan |

|---|

|

| Culture |

| Society |

| Politics |

|

|

Erbil (Arabic: أربيل, ʾarbīl;[3] Syriac: ܐܲܪܒܹܝܠ, Arbel[4][5]), also called Hawler (Kurdish: هەولێر, Hewlêr),[6] is the capital and most populated city in the Kurdistan Region of Iraq. The city is the capital of the Erbil Governorate.[7]

Erbil is one of the oldest continuously inhabited cities in the world.Human settlement at Erbil may be dated back to the 5th millennium BC.[8] At the heart of the city is the ancient Citadel of Erbil and Mudhafaria Minaret. The earliest historical reference to the region dates to the Third Dynasty of Ur of Sumer, when King Shulgi mentioned the city of Urbilum. The city was later conquered by the Assyrians.[9][10]

In the 3rd millennium BC, Erbil was an independent power in its area. It was conquered for a time by the Gutians. Beginning in the late 2nd millennium BC, it came under Assyrian control. Subsequent to this, it was part of the geopolitical province of Assyria under several empires in turn, including the Median Empire, the Achaemenid Empire (Achaemenid Assyria), Macedonian Empire, Seleucid Empire, Armenian Empire, Parthian Empire, Roman Assyria and Sasanian Empire, as well as being the capital of the tributary state of Adiabene between the mid-second century BC and early 2nd century AD. In ancient times the patron deity of the city was Ishtar of Arbela.[11]

Following the Muslim conquest of Persia, the region no longer remained united, and during the Middle Ages, the city came to be ruled by the Seljuk and Ottoman empires.[12]

Erbil's archaeological museum houses a large collection of pre-Islamic artifacts, particularly the art of Mesopotamia, and is a centre for archaeological projects in the area.[13] The city was designated as the Arab Tourism Capital 2014 by the Arab Council of Tourism.[14][15] In July 2014, the Citadel of Erbil was inscribed as a World Heritage Site.[16]

Names

[edit]Erbil is the romanization of the city's Ottoman Turkish name اربيل,[17] still used as the city's name in official English translation.[18] The Modern Standard Arabic form of the name is Arbīl (أربيل).[19] In classical antiquity, it was known as Arbela in Latin and Arbēla (Ἄρβηλα) in Greek, derived from Old Persian Arbairā (𐎠𐎼𐎲𐎡𐎼𐎠𐏓), from Assyrian Arbaʾilu,[20][21] from Sumerian Urbilum (𒌨𒉈𒈝𒆠, ur-bi₂-lumki).[22]

Archaeology

[edit]In 2006 a small excavation was conducted by Karel Novacek of the University of West Bohemia. While the citadel remains were of the Ottoman Period a field survey of the western slope of the tell found a few pottery shards from the Neolithic to Middle Bronze Age with more numerous finds from the Late Bronze to Iron Ages and from the Hellenistic, Arsacid, Sassanid Periods.[23] Being so heavily occupied, the site has never been properly excavated. In 2013 a team from the Sapienza University of Rome conducted some ground penetrating radar work on the center of the citadel. Starting in 2014 an Iraqi-led excavation began on a citadel location where the collapse of a modern building provided an opportunity for excavation. Historical aerial photographs and ground survey have also begun on the lower city.[24][25][26]

The wider plain around Erbil has a number of promising archaeological sites, most notably Tell Baqrta. The Erbil Plain Archaeological Survey began in 2012. The survey combines satellite imagery and field work to determine the development and archaeology of the plain around Erbil.[27] Tell Baqrta is a very large, 80 hectare, site which dates back to the Early Bronze Age.[28][29]

History

[edit]Bronze Age

[edit]Early Bronze

[edit]The region in which Erbil lies was largely under Sumerian domination from c. 3000 BC.

With the rise of the Akkadian Empire (2335–2154 BC) all of the Akkadian Semites and Sumerians of Mesopotamia were united under one rule.[30] Erridupizir, king of the kingdom of Gutium, captured the city in 2150 BC.[31]

The first mention of Erbil in literary sources comes from the archives of the kingdom of Ebla. They record two journeys to Erbil (Irbilum) by a messenger from Ebla around 2300 BFC.

The Neo-Sumerian ruler of Ur, Amar-Sin, sacked Urbilum in his second year, c. 1975 BC.[10]

Middle Bronze

[edit]In the centuries after the fall of the Ur III empire Erbil became a power in its area. It was conquered by Shamsi-Adad I during his short lived Upper Mesopotamian Kingdom, becoming independent after its fall.

Late Bronze

[edit]By the time of the Middle Assyrian Empire (1365–1050 BC) Erbil was within the Assyrian zone of control.

Iron Age

[edit]The region fell under the Neo-Assyrian Empire (935–605 BC). The city then changed hands a number of times including the Persian, Greek, Parthian, Roman and Sassanid rule.

Under the Medes, Cyaxares might have settled a number of people from the ancient Iranian tribe of Sagartians in the Assyrian cities of Arbela and Arrapha (modern Kirkuk), probably as a reward for their help in the capture of Nineveh. According to Classical authors, the Persian emperor Cyrus the Great occupied Assyria in 547 BC and established it as an Achaemenid military protectorate state (or satrapy) called in Old Persian Aθurā (Athura), with Babylon as the capital.[32]

The Medes, and with them the Sagarthians, were to revolt against Darius I of Persia in 522 BC, but this revolt was firmly put down by the army which Darius sent out under the leadership of General Takhmaspada the following year. The events are depicted in the Behistun Inscription which stands today in the mountains of Iran's Kermanshah province.[citation needed]

The Battle of Gaugamela, in which Alexander the Great defeated Darius III of Persia, took place in 331 BC approximately 100 kilometres (62 mi) west of Erbil according to Urbano Monti's world map.[33] After the battle, Darius managed to flee to the city. (Somewhat inaccurately, the confrontation is sometimes known as the "Battle of Arbela".) Subsequently, Arbela was part of Alexander's Empire. After the death of Alexander the Great in 323 BC, Arbela became part of the Hellenistic Seleucid Empire.

Erbil became part of the region disputed between Rome and Persia under the Sasanids. During the Parthian era to early Sassanian era, Erbil became the capital of the state of Adiabene (Assyrian Ḥadyab). The town and kingdom are known in Jewish history for the conversion of the royal family, notably Queen Helena of Adiabene, to Judaism.[34]

Its populace then gradually converted from the ancient Mesopotamian religion between the first and fourth centuries to Christianity, with Pkidha traditionally becoming its first bishop around 104 AD. The ancient Mesopotamian religion did not die out entirely in the region until the tenth century AD.[35][36] There also existed a Christian community thought to be converts from Judaism.[37] The Adiabene (East Syriac ecclesiastical province) in Arbela (Syriac: ܐܪܒܝܠ Arbel) became a centre of eastern Syriac Christianity until late in the Middle Ages.[37]

Medieval history

[edit]As many of the Assyrians who had converted to Christianity adopted Biblical (including Jewish) names, most of the early bishops had Eastern Aramaic or Jewish/Biblical names, which does not suggest that many of the early Christians in this city were converts from Judaism.[38] It served as the seat of a Metropolitan of the Assyrian Church of the East. From the city's Christian period come many church fathers and well-known authors in Aramaic.

Following the Muslim conquest of Persia, the Sassanian province of Naxwardašīragān and later Garamig ud Nodardashiragan,[39] of which Erbil made part of, was dissolved, and from the mid-seventh century AD the region saw a gradual influx of Muslim peoples, predominantly Arabs and Turkic peoples.

The most notable Kurdish tribe in the region was the Hadhabani, of which several individuals also acted as governors for the city from the late tenth century until the 12th century when it was conquered by the Zengids and its governorship given to the Turkic Begtegenids, of whom the most notable was Gökböri, who retained the city during the Ayyubid era.[40][41] Yaqut al-Hamawi further describes Erbil as being mostly Kurdish-populated in the 13th century.[42]

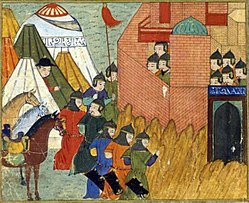

When the Mongols invaded the Near East in the 13th century, they attacked Arbil for the first time in 1237. They plundered the lower town but had to retreat before an approaching Caliphate army and had to put off the capture of the citadel.[43][broken footnote] After the fall of Baghdad to Hülegü and the Mongols in 1258, the last Begtegenid ruler surrendered to the Mongols, claiming the Kurdish garrison of the city would follow suit; they refused this however, therefore the Mongols returned to Arbil and were able to capture the citadel after a siege lasting six months.[44][45] Hülegü then appointed a Christian Assyrian governor to the town, and the Syriac Orthodox Church was allowed to build a church.

As time passed, sustained persecutions of Christians, Jews and Buddhists throughout the Ilkhanate began in earnest in 1295 under the rule of Oïrat amir Nauruz, which affected the indigenous Christian Assyrians greatly.[46] This manifested early on in the reign of the Ilkhan Ghazan. In 1297, after Ghazan had felt strong enough to overcome Nauruz's influence, he put a stop to the persecutions.

During the reign of the Ilkhan Öljeitü, the Assyrian inhabitants retreated to the citadel to escape persecution. In the Spring of 1310, the Malek (governor) of the region attempted to seize it from them with the help of the Kurds. Despite the Turkic bishop Mar Yahballaha's best efforts to avert the impending doom, the citadel was at last taken after a siege by Ilkhanate troops and Kurdish tribesmen on 1 July 1310, and all the defenders were massacred, including many of the Assyrian inhabitants of the lower town.[47][48]

However, the city's Assyrian population remained numerically significant until the destruction of the city by the forces of Timur in 1397.[49]

In the Middle Ages, Erbil was ruled successively by the Umayyads, the Abbasids, the Buwayhids, the Seljuks and then the Turkmen Begtegīnid Emirs of Erbil (1131–1232), most notably Gökböri, one of Saladin's leading generals; they were in turn followed by the Ilkhanids, the Jalayirids, the Kara Koyunlu, the Timurids and the Ak Koyunlu. Erbil was the birthplace of the famous 12th and 13th century Kurdish historians and writers Ibn Khallikan and Ibn al-Mustawfi. After the Battle of Chaldiran in 1514, Erbil came under the Soran emirate. In the 18th century Baban Emirate took the city but it was retaken by Soran ruler Mir Muhammed Kor in 1822. The Soran emirate continued ruling over Erbil until it was taken by the Ottomans in 1851. Erbil became a part of the Mosul vilayet in Ottoman Empire until World War I, when the Ottomans and their Kurdish and Turkmen allies were defeated by the British Empire.

Modern history

[edit]Erbil lies on the plain beneath the mountains, but for the most part, the inhabitants of Iraqi Kurdistan dwell up above in the rugged and rocky terrain that is the traditional habitat of the Kurds since time immemorial.[50]

The modern town of Erbil stands on a tell topped by an Ottoman fort. During the Middle Ages, Erbil became a major trading centre on the route between Baghdad and Mosul, a role which it still plays today with important road links to the outside world.

Erbil is also home to a large population of refugees due to ongoing conflicts in Syria. In 2020, it was estimated that 450,000 refugees had settled in the Erbil metropolitan area since 2003, with many of them expected to remain.[51]

The parliament of the Iraqi Kurdistan was established in Erbil in 1970 after negotiations between the Iraqi government and the Kurdistan Democratic Party (KDP) led by Mustafa Barzani, but was effectively controlled by Saddam Hussein until the Kurdish uprising at the end of the 1991 Gulf War. The legislature ceased to function effectively in the mid-1990s when fighting broke out between the two main Kurdish factions, the Kurdistan Democratic Party and the Patriotic Union of Kurdistan (PUK). The city was captured by the KDP in 1996 with the assistance of the Iraqi government of Saddam Hussein. The PUK then established an alternative Kurdish government in Sulaimaniyah. KDP claimed that in March 1996, PUK asked for Iran's help to fight KDP. Considering this as a foreign attack on Iraq's soil, the KDP asked Saddam Hussein for help.

The Kurdish Parliament in Erbil reconvened after a peace agreement was signed between the Kurdish parties in 1997, but had no real power. The Kurdish government in Erbil had control only in the western and northern parts of the autonomous region. During the 2003 invasion of Iraq, a United States special forces task force was headquartered just outside Erbil. The city was the scene of celebrations on 10 April 2003 after the fall of the Ba'ath regime.

During the U.S. occupation of Iraq, sporadic attacks hit Erbil. Parallel bomb attacks against Eid celebrations killed 117 people in February 2004.[52] Responsibility was claimed by Ansar al-Sunnah.[52] A suicide bombing in May 2005 killed 60 civilians and injured 150 more outside a police recruiting centre.[53]

The Erbil International Airport opened in the city in 2005.[54]

In September 2013, a quintuple car bombing killed six people.

In 2015, the Assyrian Church of the East moved its seat from Chicago to Erbil.

In February 2021, a series of missiles hit the city killing two and injuring eight people. Further missile attacks took place in March 2022.

Transportation

[edit]Erbil International Airport is one of Iraq's busiest airports. Services include direct flights to many domestic destinations such as Baghdad international airport. There are international flights from Erbil to many countries; such as the Netherlands, Germany, Saudi Arabia, Austria, Turkey, Jordan and elsewhere around the world. There are occasionally seasonal flights from Erbil international airport. Erbil International Airport was briefly closed to international commercial flights in September 2017 by the Iraqi government in retaliation for the Kurdish independence vote but reopened in March 2018.[55][56]

Another important form of transportation between Erbil and the surrounding areas is by bus. Among others, bus services offer connections to Turkey and Iran. A new bus terminal was opened in 2014.[57] Erbil has a system of six ring roads encircling the city.[58]

Climate

[edit]Erbil has a hot-summer Mediterranean climate (Köppen climate classification Csa), closely bordering a hot semi-arid climate (Köppen: BSh) with long, extremely hot summers and mild winters. Summers are arid, with little to no precipitation occurring between June and September. Winters are usually wet with occasional flooding, with January being the wettest month.[59]

A downpour on 17 December 2021 caused flash floods in the area, killing 14 people.[60]

| Climate data for Erbil (2012–2023 normals) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | 13.2 (55.8) |

15.4 (59.7) |

18.9 (66.0) |

25.5 (77.9) |

32.6 (90.7) |

38.9 (102.0) |

42.4 (108.3) |

42.5 (108.5) |

37.6 (99.7) |

30.1 (86.2) |

21.4 (70.5) |

15.4 (59.7) |

27.8 (82.1) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 8.1 (46.6) |

9.9 (49.8) |

13.3 (55.9) |

18.4 (65.1) |

24.9 (76.8) |

30.9 (87.6) |

34.5 (94.1) |

34.2 (93.6) |

29.5 (85.1) |

23.1 (73.6) |

15.5 (59.9) |

10.2 (50.4) |

21.0 (69.9) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | 2.9 (37.2) |

4.4 (39.9) |

7.7 (45.9) |

11.4 (52.5) |

17.3 (63.1) |

22.9 (73.2) |

26.5 (79.7) |

25.9 (78.6) |

21.3 (70.3) |

16.0 (60.8) |

9.5 (49.1) |

5.1 (41.2) |

14.2 (57.6) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 73.0 (2.87) |

50.5 (1.99) |

80.4 (3.17) |

43.1 (1.70) |

18.3 (0.72) |

0.6 (0.02) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.1 (0.00) |

0.5 (0.02) |

19.5 (0.77) |

48.5 (1.91) |

85.4 (3.36) |

419.9 (16.53) |

| Average precipitation days | 12.1 | 9.1 | 11.8 | 9.1 | 7.9 | 1.1 | 0.1 | 0.8 | 1.1 | 7.6 | 8.9 | 11.3 | 80.9 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 72.0 | 65.6 | 63.2 | 53.1 | 33.9 | 18.0 | 14.7 | 15.5 | 18.9 | 32.8 | 56.8 | 73.7 | 43.2 |

| Source 1: IEM[61] KRSO (precipitation 2012–2021)[62] | |||||||||||||

| Source 2: What's the Weather Like.org,[63] Erbilia[64] | |||||||||||||

Culture

[edit]Demographics

[edit]The city is predominantly Kurdish and has minorities of local Turkmen and Assyrians, as well as Arabs.[65][66][67]

Turkmens

[edit]The Turkmen population in Erbil is estimated to be around 300,000. They mainly reside in the neighbourhoods of Taci, Mareke and Three Tak in Erbil's city centre, around the citadel. Until 2006, they were living in the Tophane, Tekke and Saray neighborhoods of the Citadel, which contained almost 700 houses. In 2006, the citadel was emptied, and the Turkmen in the citadel were relocated to other neighbourhoods. Turkmens participate in the political institutions of the KRG, including the Parliament.[68]

Iraq's first two Turkmen schools were opened on 17 November 1993, one in Erbil and the other in Kifri.[69]

Erbil's citadel also contains the Turkmen Culture House.

Assyrians

[edit]Erbil's Ankawa district is mainly populated by Christian Assyrians. The district houses approximately 40 churches.[70][71]

Citadel of Erbil

[edit]

The Citadel of Erbil is a tell or occupied mound in the historical heart of Erbil, rising between 25 and 32 metres (82 and 105 ft) from the surrounding plain. The buildings on top of the tell stretch over a roughly oval area of 430 by 340 metres (1,410 ft × 1,120 ft) occupying 102,000 square metres (1,100,000 sq ft). It has been claimed that the site is the oldest continuously inhabited town in the world.[72] The earliest evidence for occupation of the citadel mound dates to the fifth millennium BC and possibly earlier. It appears for the first time in historical sources during the Ur III period and gained particular importance during the Neo-Assyrian Empire (tenth to seventh centuries BC) period. West of the citadel at Ary Kon quarter, a chamber tomb dating to the Neo-Assyrian Empire period has been excavated.[13] During the Sassanian period and the Abbasid Caliphate, Erbil was an important centre for Syriac Christianity and the Assyrians in general. After the Mongols captured the citadel in 1258, Erbil's importance began to decline. The main gate is guarded by an immense statue of a Kurd reading: "the house of the citadel behind him are built into stony ground of the mound and look down on the streets and tarmacked roads that circle them".

During the 20th century, the urban structure was significantly modified, as a result of which a number of houses and public buildings were destroyed. In 2007, the High Commission for Erbil Citadel Revitalization (HCECR) was established to oversee the restoration of the citadel. In the same year, all inhabitants, except one family, were evicted from the citadel as part of a large restoration project. Since then, archaeological research and restoration works have been carried out at and around the tell by various international teams and in co-operation with local specialists, and many areas remain off-limits to visitors due to the danger of unstable walls and infrastructure. The government plans to have 50 families live in the citadel once it is renovated.

The only religious structure that currently survives in the citadel is the Mulla Effendi mosque. When it was fully occupied, the citadel was divided in three districts or mahallas: from east to west the Serai, the Takya and the Topkhana. The Serai was occupied by notable families; the Takya district was named after the homes of dervishes, which are called takyas; and the Topkhana district housed craftsmen and farmers. Other sights to visit in the citadel include the bathing rooms (hammam) built in 1775 located near the mosque and the Textile Museum.[73] Erbil citadel has been inscribed on the World Heritage List on 21 June 2014.

Other sights

[edit]- The 36-metre-high (118-foot) Mudhafaria Minaret, situated in Minaret Park several blocks from the citadel, dates back to the late 12th century AD and the Governor of Erbil, in the reign of Saladin, Muzaffar Al-Din Abu Sa’eed Al-Kawkaboori (Gökböri), who had entered in the obedience of Saladin without war and married his sister. It has an octagonal base decorated with two tiers of niches, which is separated from the main shaft by a small balcony, also decorated. Another historical minaret with turquoise glazed tiles is nearby.

- Khalidiya Khanqah Mosque and Tekke, a historic mosque and Sufi lodge founded in 1805 by Mawlana Khalid al-Naqshbandi.

- Sami Abdul Rahman Park

- The Mound of Qalich Agha lies within the grounds of the Museum of Civilization, 1 kilometre (0.62 mi) from the citadel. An excavation in 1996 found tools from the Halaf, Ubaid and Uruk periods.[13]

- Classical School of the Medes

Sports

[edit]The local major football team is Erbil Soccer Club which plays its football matches at Franso Hariri Stadium (named after the assassinated Assyrian politician, former governor of Erbil city Franso Hariri) which is based in the south part of central Erbil. They won 3 Iraqi nation league titles and reached the AFC Final twice, but lost both times.

Sister cities

[edit]See also

[edit]- List of cities in Kurdistan Region

- List of largest cities in Iraq

- List of cities of the ancient Near East

- Kurdistan

- Nanakaly Hospital for Hematology & Oncology (Azady)

- Erbil International Airport – capital's airport in Kurdistan

- English Village, a luxury compound in Erbil.

References

[edit]- ^ "ھەولێر". chawykurd.com. چاوی کورد. Archived from the original on 30 July 2021. Retrieved 2 December 2020.

- ^ "Iraq: Governorates & Cities".

- ^ "أربيل" (in Arabic). Al Jazeera. Retrieved 28 December 2019.

- ^ "Search Entry". assyrianlanguages.org. Retrieved 26 May 2021.

- ^ Khan, Geoffrey (1999). A Grammar of Neo-Aramaic: The Dialect of the Jews of Arbel. BRILL. p. 2. ISBN 978-90-04-30504-5.

There are a number of variant forms of the name Arbel. The form Arbel, which is used throughout this book, is the Neo-Aramaic form of the name. The Arabic-speaking Jews of the town refer to it as Arbīl or Arwīl. In Classical Arabic sources it is known as Irbīl. The Kurds call it Hawler, which appears to have developed from the form Arbel by a series of metatheses of consonants. The name appears to be of non-Semitic origin. It is first found in cuneiform texts dating to the third millennium B.C., where it usually has the form Urbilum.

- ^ "Hewlêr dixwaze Bexda paşekeftiya mûçeyan bide" (in Kurdish). Retrieved 28 December 2019.

- ^ Danilovich, Alex (12 October 2018). Federalism, Secession, and International Recognition Regime: Iraqi Kurdistan. Routledge. ISBN 9780429827655.

- ^ Novice, Karel (2008). "Research of the Arbil Citadel, Iraq, First Season". Památky Archaeological (XCIX): 259–302.

- ^ Villard 2001

- ^ a b Hamblin, William J. (2006). Warfare in the Ancient Near East to 1600 BC. Routledge. p. 111. ISBN 0-415-25589-9.

- ^ Porter, Barbara Nevling, "Ishtar of Niniveh and her collaborator, Ishtar of Arbela, in the Reign of Assurbanipal", Iraq, vol. 66, pp. 41–44, 2004

- ^ Georges Roux – Ancient Iraq

- ^ a b c 'Directorate Antiquities of Erbil's Guide' Brochure produced by General Directorate of Antiquities, KRG, Ministry of Tourism

- ^ Erbil named 2014 Arab Tourism Capital Archived 8 July 2015 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved 30 January 2014

- ^ "Erbil: Kurdish City, Arab Capital", Rudaw. Retrieved 30 January 2014

- ^ Centre, UNESCO World Heritage. "Erbil Citadel". UNESCO World Heritage Centre. Retrieved 28 October 2022.

- ^ Nasrullah, Mehmet (1908), مكمل آوروپا خريطه سى [Complete Map of Europe] (in Ottoman Turkish), Istanbul: Tefeyyüz Kitaphanesi.

- ^ "Erbil–Baghdad Relations...", Official site, Erbil: Kurdistan Regional Government, 2024.

- ^ "العلاقات بين أربيل وبغداد" [Erbil–Baghdad Relations...], Official site (in Arabic), Erbil: Kurdistan Regional Government, 2024.

- ^ Sourdel, D. (1978). "Irbil". In van Donzel, E.; Lewis, B.; Pellat, Ch. & Bosworth, C. E. (eds.). The Encyclopaedia of Islam, Second Edition. Volume IV: Iran–Kha. Leiden: E. J. Brill. OCLC 758278456.

- ^ Kessler, Karlheinz (2006). "Arbela". In Salazar, Christine F.; Landfester, Manfred; Gentry, Francis G. (eds.). Brill's New Pauly. Brill Online.

- ^ "Urbilum [1] (SN)", Open Richly Annotated Cuneiform Corpus, Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania, 2022.

- ^ Nováček 2008.

- ^ Lawler, Andrew, "Erbil Revealed", Archaeology, vol. 67, no. 5, pp. 38–43, 2014

- ^ Al Yaqoobi, Dara, et al., "Archaeological investigations on the citadel of Erbil: background, framework and results", The archaeology of the Kurdistan region of Iraq and adjacent regions, pp. 23-27, 2016

- ^ Macginnis, J. D. A., "Archaeology of the Town under the Citadel Erbil/Hawlér", Subartu 4-5, pp. 10-13, 2011

- ^ Ur, Jason, et al., "Ancient Cities and Landscapes in the Kurdistan Region of Iraq: The Erbil Plain Archaeological Survey 2012 Season", Iraq, vol. 75, pp. 89–117, 2013

- ^ Kopanias, Konstantinos, et al., "The Tell Nader and Tell Baqrta Project in the Kurdistan region of Iraq: Preliminary report of the 2011 season", Subartu 6, pp. 23–57, 2013

- ^ Peyronel, Luca et al., "The Italian Archaeological Expedition in the Erbil Plain, Kurdistan Region of Iraq. Preliminary Report on the 2016 – 2018 Excavations at Helawa", Mesopotamia, vol. 54, pp. 1-104, 2019

- ^ Statistics (9 May 2024). "UNPO: Assyria". unpo.org.

- ^ Timeline Archived 14 August 2014 at the Wayback Machine ErbilCitadel.orq

- ^ Yarshater, Ehsan (1993). The Cambridge History of Iran, Volume 3. Cambridge University Press. p. 482. ISBN 978-0-521-20092-9.

Of the four residences of the Achaemenids named by Herodotus—Ecbatana, Pasargadae or Persepolis, Susa and Babylon—the last [situated in Iraq] was maintained as their most important capital, the fixed winter quarters, the central office of bureaucracy, exchanged only in the heat of summer for some cool spot in the highlands. Under the Seleucids and the Parthians the site of the Mesopotamian capital moved slightly to the north on the Tigris—to Seleucia and Ctesiphon. It is indeed symbolic that these new foundations were built from the bricks of ancient Babylon, just as later Baghdad, a little further upstream, was built out of the ruins of the Sassanian double city of Seleucia-Ctesiphon.

- ^ "Composite: Tavola 1–60. (Map of the World) (Re-projected in Plate Carree or Geographic, Marinus of Tyre, Ptolemy) – David Rumsey Historical Map Collection". davidrumsey.com. Retrieved 19 February 2022.

- ^ Brook, Kevin Alan (2018). The Jews of Khazaria (3rd ed.). Lanham: Rowman and Littlefield Publishers. pp. 241–243. ISBN 9781538103425.

- ^ MŠIHA-ZKHA. "HISTORY OF THE CHURCH OF ADIABENE UNDER THE PARTHIANS AND THE SASSANIDS". Tertullian.org.

- ^ Neusner, Jacob (1969). A history of the Jews in Babylonia, Volume 2. Brill Archive. p. 354.

- ^ a b British Institute of Persian Studies (1981). Iran, Volumes 19–21. the University of Michigan. pp. 15, 17.

- ^ Gillman, Ian and Hans-Joachim Klimkeit. Christians in Asia before 1500. (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan, 1999) p. 33

- ^ D. Sellwood, "ADIABENE," Encyclopædia Iranica, I/5, pp. 456–459

- ^ V. Minorsky. Studies in Caucasian History III, Prehistory of Saladin. Cambridge University Press. 208 pp. 1953.

- ^ Nováček, K., Amin, N., & Melčák, M. (2013). A Medieval City Within Assyrian Walls: The Continuity of the Town of Arbīl in Northern Mesopotamia. Iraq, 75, 1–42. doi:10.1017/S0021088900000401

- ^ B. James. Le « territoire tribal des Kurdes » et l’aire iraqienne (xe-xiiie siècles): Esquisse des recompositions spatiales. Revue des Mondes Musulmans et de la Méditerranée, 2007. P. 101-126.

- ^ Woods 1977, pp. 49–50

- ^ Nováček 2008, p. 261

- ^ J. von Hammer-Purgstall. 1842. Geschichte der Ilchane, das ist der Mongolen in Persien, Volume 1. P. 159-161.

- ^ Grousset, p. 379

- ^ Sourdel 2010

- ^ Grousset, p. 383

- ^ Edwin Munsell Bliss, Turkey and the Armenian Atrocities, (Chicago 1896) p. 153

- ^ "9781906768188: Kurdistan – a Nation Emerges – AbeBooks – Jonathan Fryer: 1906768188". abebooks.co.uk. Retrieved 22 January 2021.

- ^ "Interview with Nihad Salim Qoja: "Iranian hegemony in Iraq is very strong" – Qantara.de". Qantara.de – Dialogue with the Islamic World. 6 January 2020. Retrieved 18 July 2020.

- ^ a b Al-Nahr, Naseer (2 February 2004). "Twin Bombings Kill 56 in Irbil". Arabnews.com. Retrieved 11 May 2015.

- ^ Jaff, Warzer; Oppel, Richard A. Jr. (5 May 2005). "60 Kurds Killed by Suicide Bomb in Northern Iraq". The New York Times. Retrieved 11 May 2015.

- ^ "The Airport".

- ^ Blockade by Iraq (29 September 2017). "Iraqi govt enforces international flight ban in Kurdistan region". France 24.

- ^ International Flight Return. "Erbil International Airport". erbilairport.com.

- ^ "Erbil's New Bus Terminal a Boon for Travelers". Rudaw. 4 April 2019. Retrieved 19 March 2019.

- ^ "Erbil's 5th ring road completed – the 120 Meter highway". Rudaw. 2 May 2017. Retrieved 19 March 2019.

- ^ "Climate: Arbil – Climate graph, Temperature graph, Climate table". Climate-Data.org. Archived from the original on 10 November 2013. Retrieved 13 August 2013.

- ^ "Iraq: Flash Floods - Final Report DREF Operation n° MDRIQ014 - Iraq | ReliefWeb". reliefweb.int. 12 May 2023. Retrieved 14 February 2024.

- ^ "[ORER] Erbil [2010-] Monthly Summaries". The Iowa Environmental Mesonet. Retrieved 21 December 2024.

- ^ "Weather Statistics in Kurdistan Region Governorates for the years 2012-2021, Station : Erbil" (PDF). Kurdistan Region Government Ministry of Planning Kurdistan Region Statistics Office. Retrieved 21 December 2024.

- ^ "Erbil climate info". What's the Weather Like.org. Archived from the original on 4 October 2013. Retrieved 14 July 2013.

- ^ "Erbil Weather Forecast and Climate Information". Erbilia. Archived from the original on 9 July 2013. Retrieved 14 July 2013.

- ^ The Kurdish Population by the Kurdish Institute of Paris, 2017 estimate.

- ^ "Iraqi Turkmen". Minority Rights Group International. 19 June 2015. Retrieved 17 October 2020.

- ^ Central Statistics Agency – Home Page. Archived from the original on 16 July 2017. on the Wayback Machine website.

- ^ Bilgay Duman (August 2016). The Situation of Turkmens and The Turkmen Areas After ISIS (Report). Ortadoğu Araştırmaları Merkezi (ORSAM). Also available via Academia.edu

- ^ "Iraqi Turkmen are happy as their national days recognized". Kirkuknow. Retrieved 3 June 2022.

- ^ "What will autonomy mean for Iraq's largest Christian town?". 4 November 2021.

- ^ "Finding Their Voice". 29 October 2021.

- ^ "Erbil Citadel". UNESCO. Retrieved 30 August 2010.

- ^ 'Erbil Citadel' Brochure, High Commission for Erbil Citadel Revitalization (HCECR). www.erbilcitadel.org

- ^ "Kurdish presence in Nashville grows as city hopes to link with Erbil as sister city". The Tennessean. Retrieved 8 July 2023.

Sources

[edit]- Grousset, René, The Empire of the Steppes, (Translated from the French by Naomi Walford), New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press (1970)

- Nováček, Karel (2008). "Research of the Arbil Citadel, Iraqi Kurdistan, First Season" (PDF). Památky archeologické. 99: 259–302.

- Sourdel, D. (2010), "Irbil", in Bearman, P.; Bianquis, Th.; Bosworth, C.E.; van Donzel, E.; Heinrichs, W.P. (eds.), Encyclopaedia of Islam, Second Edition, Brill Online, OCLC 624382576

- Villard, Pierre (2001), "Arbèles", in Joannès, Francis (ed.), Dictionnaire de la civilisation mésopotamienne, Bouquins (in French), Paris: Robert Laffont, pp. 68–69, ISBN 978-2-221-09207-1

- Woods, John E. (1977), "A note on the Mongol capture of Isfahān", Journal of Near Eastern Studies, 36 (1): 49–51, doi:10.1086/372531, ISSN 0022-2968, JSTOR 544126, S2CID 161867404

External links

[edit]- Hawler Governorate

- Erbil Archived 28 October 2012 at the Wayback Machine – Portal for international visitors

- Livius.org: Arbela Archived 2 May 2013 at the Wayback Machine

- Erbil Information Guide

- Hawler/Erbil visitor's guide

- Erbil seen through camera lens