Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

2016 United Kingdom European Union membership referendum

View on Wikipedia

| ||||||||||||||||||||||

Should the United Kingdom remain a member of the European Union or leave the European Union? | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Outcome | The United Kingdom votes to leave the European Union (Brexit) | |||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Results | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||

Results by local voting area Leave: 50–60% 60–70% 70–80% Remain: 50–60% 60–70% 70–80% 90–100% | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| On the map, the darker shades for a colour indicate a larger margin. The electorate of 46.5 million represents 70.8% of the population. | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| National and regional referendums held within the United Kingdom and its constituent countries | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Part of a series on |

| Brexit |

|---|

|

|

Withdrawal of the United Kingdom from the European Union Glossary of terms |

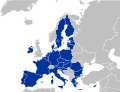

The 2016 United Kingdom European Union membership referendum, commonly referred to as the EU referendum or the Brexit referendum, was a referendum that took place on 23 June 2016 in the United Kingdom (UK) and Gibraltar under the provisions of the European Union Referendum Act 2015 to ask the electorate whether the country should continue to remain a member of, or leave, the European Union (EU). The result was a vote in favour of leaving the EU, triggering calls to begin the process of the country's withdrawal from the EU commonly termed "Brexit".

Since 1973, the UK had been a member state of the EU and its predecessor the European Communities (principally the European Economic Community), along with other international bodies. The constitutional implications of membership for the UK became a topic of debate domestically particularly regarding sovereignty. A referendum on continued membership of the European Communities (EC) to try and settle the issue was held in 1975, with 67% of voters approving continued membership.[1] Between 1975 and 2016 as European integration deepened, subsequent EC/EU treaties and agreements were ratified by the UK Parliament but without any public approval. Following the Conservative Party's victory at the 2015 general election as a main manifesto pledge, the legal basis for the EU referendum was established through the European Union Referendum Act 2015. Prime Minister David Cameron also oversaw a renegotiation of the terms of EU membership, intending to implement these changes in the event of a Remain result. The referendum was legally non-binding due to the ancient principle of parliamentary sovereignty, although the government promised to implement the result.[2]

Official campaigning took place between 15 April and 23 June 2016. The official group for remaining in the EU was Britain Stronger in Europe while Vote Leave was the official group endorsing leaving.[3] Other campaign groups, political parties, businesses, trade unions, newspapers and prominent individuals were also involved, with both sides having supporters from across the political spectrum. Parties in favour of remaining included Labour, the Liberal Democrats, the Scottish National Party, Plaid Cymru and the Green Party;[4][5][6][7] while the UK Independence Party campaigned in favour of leaving;[8] and the Conservative Party remained neutral.[9] In spite of the Conservative and Labour Party's official positions, both parties allowed their Members of Parliament to publicly campaign for either side of the issue.[10][11] Campaign issues included the costs and benefits of membership for the UK's economy, freedom of movement and migration. Several allegations of unlawful campaigning and Russian interference arose during and after the referendum.

The results recorded 51.9% of the votes cast being in favour of leaving. Most areas of England and Wales had a majority for Leave, and the majority of voters in Scotland, Northern Ireland, Greater London and Gibraltar chose Remain. Voter preference correlated with age, level of education and socioeconomic factors. The causes and reasoning of the Leave result have been the subject of analysis and commentary. Immediately after the result, financial markets reacted negatively worldwide, and Cameron announced that he would resign as prime minister and leader of the Conservative Party, which he did in July. The referendum prompted an array of international reactions. Jeremy Corbyn faced a Labour Party leadership challenge as a result of the referendum. In 2017, the UK gave formal notice of intent to withdraw from the EU, with the withdrawal being formalised in 2020.

Background

[edit]2016 United Kingdom EU membership referendum (23 June) |

|---|

| Legislation |

| Referendum question |

| “Should the United Kingdom remain a member of the European Union or leave the European Union?” |

| Referendum choices |

|

“Remain a member of the European Union” “Leave the European Union” |

| Background |

| Campaign |

|

| Outcome |

The European Communities were formed in the 1950s – the European Coal and Steel Community (ECSC) in 1952, and the European Atomic Energy Community (EAEC or Euratom) and European Economic Community (EEC) in 1957.[12] The EEC, the more ambitious of the three, came to be known as the "Common Market". The UK first applied to join them in 1961, but this was vetoed by France.[12] A later application was successful, and the UK joined in 1973; two years later, a national referendum on continuing EC membership resulted in 67.2% voting "Yes" in favour of continued membership, on a 64.6% national turnout.[12] However, no further referendums on the issue of the United Kingdom's relationship with Europe were held and successive British governments integrated further into the European project, which gained focus when the Maastricht Treaty established the European Union (EU) in 1993, which incorporated (and after the Lisbon Treaty, succeeded) the European Communities.[12][13]

Growing pressure for a referendum

[edit]At the May 2012 NATO summit meeting, UK Prime Minister David Cameron, Foreign Secretary William Hague and Ed Llewellyn discussed the idea of using a European Union referendum as a concession to the Eurosceptic wing of the Conservative Party.[14] On 20 June 2012, a three-clause private member's bill was introduced into the House of Commons by the then Eurosceptic MP Douglas Carswell to end the United Kingdom's EU membership and repeal the European Communities Act 1972, but without containing any commitment to the holding of any referendum. It received a second reading in a half-hour long debate in the chamber on 26 October 2012, but did not progress any further.[15]

In January 2013, Cameron delivered the Bloomberg speech and promised that, should the Conservatives win a parliamentary majority at the 2015 general election, the British government would negotiate more favourable arrangements for continuing British membership of the EU, before holding a referendum on whether the UK should remain in or leave the EU.[16] The Conservative Party published a draft EU Referendum Bill in May 2013, and outlined its plans for renegotiation followed by an in-out vote (i.e. a referendum giving options only of leaving and of remaining in under the current terms, or under new terms if these had become available), were the party to be re-elected in 2015.[17] The draft Bill stated that the referendum had to be held no later than 31 December 2017.[18]

The draft legislation was taken forward as a Private member's bill by Conservative MP James Wharton which was known as the European Union (Referendum) Bill 2013.[19] The bill's First Reading in the House of Commons took place on 19 June 2013.[20] Cameron was said by a spokesperson to be "very pleased" and would ensure the Bill was given "the full support of the Conservative Party".[21]

Regarding the ability of the bill to bind the UK Government in the 2015–20 Parliament (which indirectly, as a result of the referendum itself, proved to last only two years) to holding such a referendum, a parliamentary research paper noted that:

The Bill simply provides for a referendum on continued EU membership by the end of December 2017 and does not otherwise specify the timing, other than requiring the Secretary of State to bring forward orders by the end of 2016. [...] If no party obtained a majority at the [next general election due in 2015], there might be some uncertainty about the passage of the orders in the next Parliament.[22]

The bill received its Second Reading on 5 July 2013, passing by 304 votes to none after almost all Labour MPs and all Liberal Democrat MPs abstained, cleared the Commons in November 2013, and was then introduced to the House of Lords in December 2013, where members voted to block the bill.[23]

Conservative MP Bob Neill then introduced an Alternative Referendum Bill to the Commons.[24][25] After a debate on 17 October 2014, it passed to the Public Bills Committee, but because the Commons failed to pass a money resolution, the bill was unable to progress further before the dissolution of parliament on 27 March 2015.[26][27]

At the European Parliament election in 2014, the UK Independence Party (UKIP) secured more votes and more seats than any other party, the first time a party other than the Conservatives or Labour had topped a nationwide poll in 108 years, leaving the Conservatives in third place.[28]

Under Ed Miliband's leadership between 2010 and 2015, the Labour Party ruled out an in-out referendum unless and until a further transfer of powers from the UK to the EU were to be proposed.[29] In their manifesto for the 2015 general election, the Liberal Democrats pledged to hold an in-out referendum only in the event of there being a change in the EU treaties.[30] The UK Independence Party (UKIP), the British National Party (BNP), the Green Party,[31] the Democratic Unionist Party[32] and the Respect Party[33] all supported the principle of a referendum.

When the Conservative Party won a majority of seats in the House of Commons at the 2015 general election, Cameron reiterated his party's manifesto commitment to hold an in-out referendum on UK membership of the EU by the end of 2017, but only after "negotiating a new settlement for Britain in the EU".[34]

Renegotiation before the referendum

[edit]In early 2014, David Cameron outlined the changes he aimed to bring about in the EU and in the UK's relationship with it.[35] These were: additional immigration controls, especially for citizens of new EU member states; tougher immigration rules for present EU citizens; new powers for national parliaments collectively to veto proposed EU laws; new free-trade agreements and a reduction in bureaucracy for businesses; a lessening of the influence of the European Court of Human Rights on British police and courts; more power for individual member states, and less for the central EU; and abandonment of the EU notion of "ever closer union".[35] He intended to bring these about during a series of negotiations with other EU leaders and then, if re-elected, to announce a referendum.[35]

In November that year, Cameron gave an update on the negotiations and further details of his aims.[36] The key demands made of the EU were: on economic governance, to recognise officially that Eurozone laws would not necessarily apply to non-Eurozone EU members and the latter would not have to bail out troubled Eurozone economies; on competitiveness, to expand the single market and to set a target for the reduction of bureaucracy for businesses; on sovereignty, for the UK to be legally exempted from "ever closer union" and for national parliaments to be able collectively to veto proposed EU laws; and, on immigration, for EU citizens going to the UK for work to be unable to claim social housing or in-work benefits until they had worked there for four years, and for them to be unable to send child benefit payments overseas.[36][37]

The outcome of the renegotiations was announced in February 2016.[38] The renegotiated terms were in addition to the United Kingdom's existing opt-outs in the European Union and the UK rebate. The significance of the changes to the EU-UK agreement was contested and speculated upon, with none of the changes considered fundamental, but some considered important to many British people.[38] Some limits to in-work benefits for EU immigrants were agreed, but these would apply on a sliding scale for four years and would be for new immigrants only; before they could be applied, a country would have to get permission from the European Council.[38] Child benefit payments could still be made overseas, but these would be linked to the cost of living in the other country.[39] On sovereignty, the UK was reassured that it would not be required to participate in "ever closer union"; these reassurances were "in line with existing EU law".[38] Cameron's demand to allow national parliaments to veto proposed EU laws was modified to allow national parliaments collectively to object to proposed EU laws, in which case the European Council would reconsider the proposal before itself deciding what to do.[38] On economic governance, anti-discrimination regulations for non-Eurozone members would be reinforced, but they would be unable to veto any legislation.[40] The final two areas covered were proposals to "exclude from the scope of free movement rights, third country nationals who had no prior lawful residence in a Member State before marrying a Union citizen"[41] and to make it easier for member states to deport EU nationals for public policy or public security reasons.[42] The extent to which the various parts of the agreement would be legally binding is complex; no part of the agreement itself changed EU law, but some parts could be enforceable in international law.[43]

The EU had reportedly offered David Cameron a so-called "emergency brake", which would have allowed the UK to withhold social benefits to new immigrants for the first four years after they arrived; this brake could have been applied for a period of seven years.[44] That offer was still on the table at the time of the Brexit referendum, but expired when the vote determined that the UK would leave the EU. Cameron claimed that "he could have avoided Brexit had European leaders let him control migration", according to the Financial Times.[45][46] However, Angela Merkel said that the offer had not been made by the EU. Merkel stated in the German Parliament: "If you wish to have free access to the single market then you have to accept the fundamental European rights as well as obligations that come from it. This is as true for Great Britain as for anybody else."[47]

Legislation

[edit]The planned referendum was included in the Queen's Speech on 27 May 2015.[48] It was suggested at the time that Cameron was planning to hold the referendum in October 2016,[49] but the European Union Referendum Act 2015, which authorised it, went before the House of Commons the following day, just three weeks after the election.[50] On the bill's second reading on 9 June, members of the House of Commons voted by 544 to 53 in favour, endorsing the principle of holding a referendum, with only the Scottish National Party voting against.[51] In contrast to the Labour Party's position prior to the 2015 general election under Miliband, acting Labour leader Harriet Harman committed her party to supporting plans for an EU referendum by 2017, a position maintained by elected leader Jeremy Corbyn.[52]

To enable the referendum to take place, the European Union Referendum Act[53] was passed by the Parliament of the United Kingdom. It extended to include and take legislative effect in Gibraltar,[54][55] and received royal assent on 17 December 2015. The Act was, in turn, confirmed, enacted and implemented in Gibraltar by the European Union (Referendum) Act 2016 (Gibraltar),[56] which was passed by the Gibraltar Parliament and entered into law upon receiving the assent of the Governor of Gibraltar on 28 January 2016.

The European Union Referendum Act required a referendum to be held on the question of the UK's continued membership of the European Union (EU) before the end of 2017. It did not contain any requirement for the UK Government to implement the results of the referendum. Instead, it was designed to gauge the electorate's opinion on EU membership. The referendums held in Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland in 1997 and 1998 are examples of this type, where opinion was tested before legislation was introduced. The UK does not have constitutional provisions which would require the results of a referendum to be implemented, unlike, for example, the Republic of Ireland, where the circumstances in which a binding referendum should be held are set out in its constitution. In contrast, the legislation that provided for the referendum held on AV in May 2011 would have implemented the new system of voting without further legislation, provided that the boundary changes also provided for in the Parliamentary Voting System and Constituencies Act 2011 were also implemented. In the event, there was a substantial majority against any change. The 1975 referendum was held after the re-negotiated terms of the UK's EC membership had been agreed by all EC Member States, and the terms set out in a command paper and agreed by both Houses.[57] Following the 2016 referendum, the High Court confirmed that the result was not legally binding, owing to the constitutional principles of parliamentary sovereignty and representative democracy, and the legislation authorising the referendum did not contain clear words to the contrary.[58]

Referendum question

[edit]

Research by the Electoral Commission confirmed that its recommended question "was clear and straightforward for voters, and was the most neutral wording from the range of options ... considered and tested", citing responses to its consultation by a diverse range of consultees.[59] The proposed question was accepted by the government in September 2015, shortly before the bill's third reading.[60] The question that appeared on ballot papers in the referendum under the Act was:

Should the United Kingdom remain a member of the European Union or leave the European Union?

with the responses to the question (to be marked with a single (X)):

Remain a member of the European Union

Leave the European Union

and in Welsh:

A ddylai'r Deyrnas Unedig aros yn aelod o'r Undeb Ewropeaidd neu adael yr Undeb Ewropeaidd?

with the responses (to be marked with a single (X)):

Aros yn aelod o'r Undeb Ewropeaidd

Gadael yr Undeb Ewropeaidd

Administration

[edit]Date

[edit]Prior to being officially announced, it was widely speculated that a June date for the referendum was a serious possibility. The First Ministers of Northern Ireland, Scotland, and Wales co-signed a letter to Cameron on 3 February 2016 asking him not to hold the referendum in June, as devolved elections were scheduled to take place the previous month on 5 May. These elections had been postponed for a year to avoid a clash with the 2015 general election, after Westminster had implemented the Fixed-term Parliament Act. Cameron refused this request, saying people were able to make up their own minds in multiple elections spaced at least six weeks from each other.[61] [62]

On 20 February 2016, Cameron announced that the UK Government would formally recommend to the British people that the UK should remain a member of a reformed European Union and that the referendum would be held on 23 June, marking the official launch of the campaign. He also announced that Parliament would enact secondary legislation on 22 February relating to the European Union Referendum Act 2015. With the official launch, ministers of the UK Government were then free to campaign on either side of the argument in a rare exception to Cabinet collective responsibility.[63]

Eligibility to vote

[edit]The right to vote in the referendum in the United Kingdom is defined by the legislation as limited to residents of the United Kingdom who were either also Commonwealth citizens under Section 37 of the British Nationality Act 1981 (which include British citizens and other British nationals), or those who were also citizens of the Republic of Ireland, or both. Members of the House of Lords, who could not vote in general elections, were able to vote in the referendum. The electorate of 46,500,001 represented 70.8% of the population of 65,678,000 (UK and Gibraltar).[64] Other than the residents of Gibraltar, British Overseas Territories Citizens residing in the British Overseas Territories were unable to vote in the referendum.[65][66]

Residents of the United Kingdom who were citizens of other EU countries were not allowed to vote unless they were citizens (or were also citizens) of the Republic of Ireland, of Malta, or of the Republic of Cyprus.[67]

The Representation of the People Acts 1983 (1983 c. 2) and 1985 (1985 c. 50), as amended, also permit certain British citizens (but not other British nationals), who had once lived in the United Kingdom, but had since and in the meantime lived outside of the United Kingdom, but for a period of no more than 15 years, to vote.[68]

Voting on the day of the referendum was from 0700 to 2200 BST (WEST) (0700 to 2200 CEST in Gibraltar) in some 41,000 polling stations staffed by over 100,000 poll workers. Each polling station was specified to have no more than 2,500 registered voters.[citation needed] Under the provisions of the Representation of the People Act 2000, postal ballots were also permitted in the referendum and were sent out to eligible voters some three weeks ahead of the vote (2 June 2016).

The minimum age for voters in the referendum was set to 18 years, in line with the Representation of the People Act, as amended. A House of Lords amendment proposing to lower the minimum age to 16 years was rejected.[69]

The deadline to register to vote was initially midnight on 7 June 2016; however, this was extended by 48 hours owing to technical problems with the official registration website on 7 June, caused by unusually high web traffic. Some supporters of the Leave campaign, including the Conservative MP Sir Gerald Howarth, criticised the government's decision to extend the deadline, alleging it gave Remain an advantage because many late registrants were young people who were considered to be more likely to vote for Remain.[70] According to provisional figures from the Electoral Commission, almost 46.5 million people were eligible to vote.[71]

Registration problems

[edit]Nottingham City Council emailed a Vote Leave supporter to say that the council was unable to check whether the nationality that people stated on their voting registration form was true, and hence that they simply had to assume that the information that was submitted was, indeed, correct.[72]

3,462 EU nationals were wrongly sent postal voting cards, due to an IT issue experienced by Xpress, an electoral software supplier to a number of councils. Xpress was initially unable to confirm the exact number of those affected. The matter was resolved by the issuance of a software patch which rendered the wrongly recorded electors ineligible to vote on 23 June.[72]

Crown Dependencies

[edit]Residents of the Crown Dependencies (which are not part of the United Kingdom), namely the Isle of Man and the Bailiwicks of Jersey and Guernsey, even if they were British citizens, were excluded from the referendum unless they were also previous residents of the United Kingdom (that is England and Wales, Scotland and Northern Ireland).[73]

Some residents of the Isle of Man protested that they, as full British citizens under the British Nationality Act 1981 and living within the British Islands, should also have been given the opportunity to vote in the referendum, as the Isle and the Bailiwicks, although not included as if they were part of the United Kingdom for the purpose of European Union (and European Economic Area (EEA)) membership (as is the case with Gibraltar), would also have been significantly affected by the outcome and impact of the referendum.[73]

Campaign

[edit]

In October 2015, Britain Stronger in Europe, a cross-party group campaigning for Britain to remain a member of the EU, was formed.[74] There were two rival groups promoting British withdrawal from the EU that sought to become the official Leave campaign: Leave.EU (which was endorsed by most of UKIP, including Nigel Farage), and Vote Leave (endorsed by Conservative Party Eurosceptics). In January 2016, Nigel Farage and the Leave.EU campaign became part of the Grassroots Out movement, which was borne out of infighting between Vote Leave and Leave.EU campaigners.[75][76] In April, the Electoral Commission announced that Britain Stronger in Europe and Vote Leave were to be designated as the official remain and leave campaigns respectively.[77] This gave them the right to spend up to £7,000,000, a free mailshot, TV broadcasts and £600,000 in public funds. The UK Government's official position was to support the Remain campaign. Nevertheless, Cameron announced that Conservative Ministers and MPs were free to campaign in favour of remaining in the EU or leaving it, according to their conscience. This decision came after mounting pressure for a free vote for ministers.[78] In an exception to the usual rule of cabinet collective responsibility, Cameron allowed cabinet ministers to campaign publicly for EU withdrawal.[79] A Government-backed campaign was launched in April.[80] On 16 June, all official national campaigning was suspended until 19 June following the murder of Jo Cox.[81]

After internal polls suggested that 85% of the UK population wanted more information about the referendum from the government, a leaflet was sent to every household in the UK.[82] It contained details about why the government believed the UK should remain in the EU. This leaflet was criticised by those wanting to leave as giving the remain side an unfair advantage; it was also described as being inaccurate and a waste of taxpayers' money (it cost £9.3m in total).[83] During the campaign, Nigel Farage suggested that there would be public demand for a second referendum should the result be a remain win closer than 52–48%, because the leaflet meant that the remain side had been permitted to spend more money than the leave side.[84]

In the week beginning on 16 May, the Electoral Commission sent a voting guide regarding the referendum to every household within the UK and Gibraltar to raise awareness of the upcoming referendum. The eight-page guide contained details on how to vote, as well as a sample of the actual ballot paper, and a whole page each was given to the campaign groups Britain Stronger in Europe and Vote Leave to present their case.[85][86]

The Vote Leave campaign argued that if the UK left the EU, national sovereignty would be protected, immigration controls could be imposed, and the UK would be able to sign trade deals with the rest of the world. The UK would also be able to stop membership payments to the EU every week.[87][note 1] The Britain Stronger in Europe campaign argued that leaving the European Union would damage the UK economy, and that the status of the UK as a world influence was hinged upon its membership.[90]

Responses to the referendum campaign

[edit]Party policies

[edit]

The tables list political parties with representation in the House of Commons or the House of Lords, the European Parliament, the Scottish Parliament, the Northern Ireland Assembly, the Welsh Parliament, or the Gibraltar Parliament at the time of the referendum.

Great Britain

[edit]| Position | Political parties | Ref. | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Remain | Green Party of England and Wales | [91] | |

| Labour Party | [92][93] | ||

| Liberal Democrats | [94] | ||

| Plaid Cymru – The Party of Wales | [95] | ||

| Scottish Greens | [96] | ||

| Scottish National Party (SNP) | [97][98] | ||

| Leave | UK Independence Party (UKIP) | [99] | |

| Neutral | Conservative Party | [100] | |

Northern Ireland

[edit]| Position | Political parties | Ref. | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Remain | Alliance Party of Northern Ireland | [101][102] | |

| Green Party Northern Ireland | [103] | ||

| Sinn Féin | [104] | ||

| Social Democratic and Labour Party (SDLP) | [105] | ||

| Ulster Unionist Party (UUP) | [106] | ||

| Leave | Democratic Unionist Party (DUP) | [107][108] | |

| People Before Profit (PBP) | [109] | ||

| Traditional Unionist Voice (TUV) | [110] | ||

Gibraltar

[edit]| Position | Political parties | Ref. | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Remain | Gibraltar Social Democrats | [111] | |

| Gibraltar Socialist Labour Party | [112] | ||

| Liberal Party of Gibraltar | [112] | ||

Minor parties

[edit]Among minor parties, the Socialist Labour Party, the Communist Party of Britain, Britain First,[113] the British National Party (BNP),[114] Éirígí [Ireland],[115] the Respect Party,[116] the Trade Unionist and Socialist Coalition (TUSC),[117] the Social Democratic Party,[118] the Liberal Party,[119] Independence from Europe,[120] and the Workers' Party [Ireland][121] supported leaving the EU.

The Scottish Socialist Party (SSP), Left Unity and Mebyon Kernow [Cornwall] supported remaining in the EU.[122][123][124]

The Socialist Party of Great Britain supported neither leave nor remain and the Women's Equality Party had no official position on the issue.[125][126][127][128] The Socialist Equality Party called for an "active boycott" of the referendum.[129]

Cabinet ministers

[edit]The Cabinet of the United Kingdom is a body responsible for making decisions on policy and organising governmental departments; it is chaired by the Prime Minister and contains most of the government's ministerial heads.[130] Following the announcement of the referendum in February, 23 of the 30 Cabinet ministers (including attendees) supported the UK staying in the EU.[131] Iain Duncan Smith, in favour of leaving, resigned on 19 March and was replaced by Stephen Crabb who was in favour of remaining.[131][132] Crabb was already a cabinet member, as the Secretary of State for Wales, and his replacement, Alun Cairns, was in favour of remaining, bringing the total number of pro-remain Cabinet members to 25.

Business

[edit]Various UK multinationals have stated that they would not like the UK to leave the EU because of the uncertainty it would cause, such as Shell,[133] BT[134] and Vodafone,[135] with some assessing the pros and cons of Britain exiting.[136] The banking sector was one of the most vocal advocating to stay in the EU, with the British Bankers' Association saying: "Businesses don't like that kind of uncertainty".[137] RBS warned of potential damage to the economy.[138] Furthermore, HSBC and foreign-based banks JP Morgan and Deutsche Bank claim a Brexit might result in the banks' changing domicile.[139][140] According to Goldman Sachs and the City of London's policy chief, all such factors could impact on the City of London's present status as a European and global market leader in financial services.[141] In February 2016, leaders of 36 of the FTSE 100 companies, including Shell, BAE Systems, BT and Rio Tinto, officially supported staying in the EU.[142] Moreover, 60% of the Institute of Directors and the EEF memberships supported staying.[143]

Many UK-based businesses, including Sainsbury's, remained steadfastly neutral, concerned that taking sides in the divisive issue could lead to a backlash from customers.[144]

Richard Branson stated that he was "very fearful" of the consequences of a UK exit from the EU.[145] Alan Sugar expressed similar concern.[146]

James Dyson, founder of the Dyson company, argued in June 2016 that the introduction of tariffs would be less damaging for British exporters than the appreciation of the pound against the Euro, arguing that, because Britain ran a 100 billion pound trade deficit with the EU, tariffs could represent a significant revenue source for the Treasury.[147] Pointing out that languages, plugs and laws differ between EU member states, Dyson said that the 28-country bloc was not a single market, and argued the fastest growing markets were outside the EU.[147] Engineering company Rolls-Royce wrote to employees to say that it did not want the UK to leave the EU.[148]

Surveys of large UK businesses showed a strong majority favoured the UK remaining in the EU.[149] Small and medium-sized UK businesses were more evenly split.[149] Polls of foreign businesses found that around half would be less likely to do business in the UK, while 1% would increase their investment in the UK.[150][151][152] Two large car manufacturers, Ford and BMW, warned in 2013 against Brexit, suggesting it would be "devastating" for the economy.[153] Conversely, in 2015, some other manufacturing executives told Reuters that they would not shut their plants if the UK left the EU, although future investment might be put at risk.[154] The CEO of Vauxhall stated that a Brexit would not materially affect its business.[155] Foreign-based Toyota CEO Akio Toyoda confirmed that, whether or not Britain left the EU, Toyota would carry on manufacturing cars in Britain as they had done before.[156]

Exchange rates and stock markets

[edit]In the week following conclusion of the UK's renegotiation (and especially after Boris Johnson announced that he would support the UK leaving), the pound fell to a seven-year low against the dollar and economists at HSBC warned that it could drop even more.[157] At the same time, Daragh Maher, head of HSBC, suggested that if Sterling dropped in value so would the Euro. European banking analysts also cited Brexit concerns as the reason for the Euro's decline.[158] Immediately after a poll in June 2016 showed that the Leave campaign was 10 points ahead, the pound dropped by a further one per cent.[159] In the same month, it was announced that the value of goods exported from the UK in April had shown a month-on-month increase of 11.2%, "the biggest rise since records started in 1998".[160][161]

Uncertainty over the referendum result, together with several other factors—US interest rates rising, low commodity prices, low Eurozone growth and concerns over emerging markets such as China—contributed to a high level of stock market volatility in January and February 2016.[citation needed] On 14 June, polls showing that a Brexit was more likely led to the FTSE 100 falling by 2%, losing £98 billion in value.[162][163] After further polls suggested a move back towards Remain, the pound and the FTSE recovered.[164]

On the day of the referendum, sterling hit a 2016 high of $1.5018 for £1 and the FTSE 100 also climbed to a 2016 high, as a new poll suggested a win for the Remain campaign.[165] Initial results suggested a vote for 'Remain' and the value of the pound held its value. However, when the result for Sunderland was announced, it indicated an unexpected swing to 'Leave'. Subsequent results appeared to confirm this swing and sterling fell in value to $1.3777, its lowest level since 1985. On the following Monday when the markets opened, £1 sterling fell to a new low of $1.32.[166]

Muhammad Ali Nasir and Jamie Morgan two British economists differentiated and reflected on the weakness of the Sterling due to the weak external position of the UK's economy and the further role played by the uncertainty surrounding Brexit[167] They reported that during the week of the referendum, up to the declaration of the result, exchange rate depreciation deviated from the long-run trend by approximately 3.5 per cent, but the actual immediate effect on the exchange rate was an 8 per cent depreciation. Furthermore, that over the period from the announcement of the referendum, the exchange rate fluctuated markedly around its trend and one can also identify a larger effect based on the "wrong-footing" of markets at the point when the outcome was announced.[167]

When the London Stock Exchange opened on the morning of 24 June, the FTSE 100 fell from 6338.10 to 5806.13 in the first ten minutes of trading. It recovered to 6091.27 after a further 90 minutes, before further recovering to 6162.97 by the end of the day's trading. When the markets reopened the following Monday, the FTSE 100 showed a steady decline losing over 2% by mid-afternoon.[168] Upon opening later on the Friday after the referendum, the US Dow Jones Industrial Average dropped nearly 450 points or about 2½% in less than half an hour. The Associated Press called the sudden worldwide stock market decline a stock market crash.[169] Investors in worldwide stock markets lost more than the equivalent of US$2 trillion on 24 June 2016, making it the worst single-day loss in history, in absolute terms.[170] The market losses amounted to US$3 trillion by 27 June.[171] Sterling fell to a 31-year low against the US dollar.[172] The UK's and the EU's sovereign debt credit ratings were also lowered to AA by Standard & Poor's.[173][174]

By mid-afternoon on 27 June 2016, sterling was at a 31-year low, having fallen 11% in two trading days, and the FTSE 100 had surrendered £85 billion;[175] however, by 29 June it had recovered all its losses since the markets closed on polling day and the value of the pound had begun to rise.[176][177]

European responses

[edit]The referendum was generally well-accepted by the European far right.[178] Marine Le Pen, the leader of the French Front national, described the possibility of a Brexit as "like the fall of the Berlin Wall" and commented that "Brexit would be marvellous – extraordinary – for all European peoples who long for freedom".[179] A poll in France in April 2016 showed that 59% of the French people were in favour of Britain remaining in the EU.[180] Dutch politician Geert Wilders, leader of the Party for Freedom, said that the Netherlands should follow Britain's example: "Like in the 1940s, once again Britain could help liberate Europe from another totalitarian monster, this time called 'Brussels'. Again, we could be saved by the British."[181]

Polish President Andrzej Duda lent his support for the UK remaining within the EU.[182] Moldovan Prime Minister Pavel Filip asked all citizens of Moldova living in the UK to speak to their British friends and convince them to vote for the UK to remain in the EU.[183] Spanish foreign minister José García-Margallo said Spain would demand control of Gibraltar the "very next day" after a British withdrawal from the EU.[184] Margallo also threatened to close the border with Gibraltar if Britain left the EU.[185]

Swedish foreign minister Margot Wallström said on 11 June 2016 that if Britain left the EU, other countries would have referendums on whether to leave the EU, and that if Britain stayed in the EU, other countries would negotiate, ask and demand to have special treatment.[186] Czech prime minister Bohuslav Sobotka suggested in February 2016 that the Czech Republic would start discussions on leaving the EU if the UK voted for an EU exit.[187]

Non-European responses

[edit]International Monetary Fund

[edit]Christine Lagarde, the managing director of the International Monetary Fund, warned in February 2016 that the uncertainty over the outcome of the referendum would be bad "in and of itself" for the British economy.[188] In response, Leave campaigner Priti Patel said a previous warning from the IMF regarding the coalition government's deficit plan for the UK was proven incorrect and that the IMF "were wrong then and are wrong now".[189]

United States

[edit]In October 2015, United States Trade Representative Michael Froman declared that the United States was not keen on pursuing a separate free-trade agreement (FTA) with Britain if it were to leave the EU, thus, according to The Guardian newspaper, undermining a key economic argument of proponents of those who say Britain would prosper on its own and be able to secure bilateral FTAs with trading partners.[190] Also in October 2015, the United States Ambassador to the United Kingdom Matthew Barzun said that UK participation in NATO and the EU made each group "better and stronger" and that, while the decision to remain or leave is a choice for the British people, it was in the US interest that it remain.[191] In April 2016, eight former US Secretaries of the Treasury, who had served both Democratic and Republican presidents, urged Britain to remain in the EU.[192]

In July 2015, President Barack Obama confirmed the long-standing US preference for the UK to remain in the EU. Obama said: "Having the UK in the EU gives us much greater confidence about the strength of the transatlantic union, and is part of the cornerstone of the institutions built following World War II that has made the world safer and more prosperous. We want to make sure that the United Kingdom continues to have that influence."[193] Some Conservative MPs accused U.S. President Barack Obama of interfering in the Brexit vote,[194][195] with Boris Johnson calling the intervention a "piece of outrageous and exorbitant hypocrisy"[196] and UKIP leader Nigel Farage accusing him of "monstrous interference", saying "You wouldn't expect the British Prime Minister to intervene in your presidential election, you wouldn't expect the Prime Minister to endorse one candidate or another."[197] Obama's intervention was criticised by Republican Senator Ted Cruz as "a slap in the face of British self-determination as the president, typically, elevated an international organisation over the rights of a sovereign people", and stated that "Britain will be at the front of the line for a free trade deal with America", were Brexit to occur.[198][199] More than 100 MPs from the Conservatives, Labour, UKIP and the DUP wrote a letter to the U.S. ambassador in London asking President Obama not to intervene in the Brexit vote as it had "long been the established practice not to interfere in the domestic political affairs of our allies and we hope that this will continue to be the case."[200][201] Two years later, one of Obama's former aides recounted that the public intervention was made following a request by Cameron.[202]

Prior to the vote, Republican presidential candidate Donald Trump anticipated that Britain would leave based on its concerns over migration,[203] while Democratic presidential candidate Hillary Clinton hoped that Britain would remain in the EU to strengthen transatlantic co-operation.[204]

Other states

[edit]In October 2015, Chinese President Xi Jinping declared his support for Britain remaining in the EU, saying "China hopes to see a prosperous Europe and a united EU, and hopes Britain, as an important member of the EU, can play an even more positive and constructive role in promoting the deepening development of China-EU ties". Chinese diplomats have stated "off the record" that the People's Republic sees the EU as a counterbalance to American economic power, and that an EU without Britain would mean a stronger United States.[citation needed]

In February 2016, the finance ministers from the G20 major economies warned for the UK to leave the EU would lead to "a shock" in the global economy.[205][206]

In May 2016, the Australian Prime Minister Malcolm Turnbull said that Australia would prefer the UK to remain in the EU, but that it was a matter for the British people, and "whatever judgment they make, the relations between Britain and Australia will be very, very close".[207]

Indonesian president Joko Widodo stated during a European trip that he was not in favour of Brexit.[208]

Sri Lankan Prime Minister Ranil Wickremesinghe issued a statement of reasons why he was "very concerned" at the possibility of Brexit.[209]

Russian President Vladimir Putin said: "I want to say it is none of our business, it is the business of the people of the UK."[210] Maria Zakharova, the official Russian foreign ministry spokesperson, said: "Russia has nothing to do with Brexit. We are not involved in this process in any way. We don't have any interest in it."[211]

Economists

[edit]In November 2015, the Governor of the Bank of England Mark Carney said that the Bank of England would do what was necessary to help the UK economy if the British people voted to leave the EU.[212] In March 2016, Carney told MPs that an EU exit was the "biggest domestic risk" to the UK economy, but that remaining a member also carried risks, related to the European Monetary Union, of which the UK is not a member.[213] In May 2016, Carney said that a "technical recession" was one of the possible risks of the UK leaving the EU.[214] However, Iain Duncan Smith said Carney's comment should be taken with "a pinch of salt", saying "all forecasts in the end are wrong".[215]

In December 2015, the Bank of England published a report about the impact of immigration on wages. The report concluded that immigration put downward pressure on workers' wages, particularly low-skilled workers: a 10 per cent point rise in the proportion of migrants working in low-skilled services drove down the average wages of low-skilled workers by about 2 per cent.[216] The 10 percentage point rise cited in the paper is larger than the entire rise observed since the 2004–06 period in the semi/unskilled services sector, which is about 7 percentage points.[217]

In March 2016, Nobel prize-winning economist Joseph Stiglitz argued that he might reconsider his support for the UK remaining in the EU if the proposed Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership (TTIP) were to be agreed to.[218] Stiglitz warned that under the investor-state dispute settlement provision in current drafts of the TTIP, governments risked being sued for loss of profits resulting from new regulations, including health and safety regulations to limit the use of asbestos or tobacco.[218]

The German economist Clemens Fuest wrote that there was a liberal, free-trade bloc in the EU comprising the UK, the Netherlands, the Czech Republic, Sweden, Denmark, Ireland, Slovakia, Finland, Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania, controlling 32% of the votes in the European Council and standing in opposition to the dirigiste, protectionist policies favoured by France and its allies.[219] Germany with its 'social market' economy stands midway between the French dirigiste economic model and the British free-market economic model. From the German viewpoint, the existence of the liberal bloc allows Germany to play-off free-market Britain against dirigiste France, and that if Britain were to leave, the liberal bloc would be severely weakened, thereby allowing the French to take the EU into a much more dirigiste direction that would be unattractive from the standpoint of Berlin.[219]

A study by Oxford Economics for the Law Society of England and Wales has suggested that Brexit would have a particularly large negative impact on the UK financial services industry and the law firms that support it, which could cost the law sector as much as £1.7bn per annum by 2030.[220] The Law Society's own report into the possible effects of Brexit notes that leaving the EU would be likely to reduce the role played by the UK as a centre for resolving disputes between foreign firms, whereas a potential loss of "passporting" rights would require financial services firms to transfer departments responsible for regulatory oversight overseas.[221]

World Pensions Forum director M. Nicolas J. Firzli has argued that the Brexit debate should be viewed within the broader context of economic analysis of EU law and regulation in relation to English common law, arguing: "Every year, the British Parliament is forced to pass tens of new statutes reflecting the latest EU directives coming from Brussels – a highly undemocratic process known as 'transposition'... Slowly but surely, these new laws dictated by EU commissars are conquering English common law, imposing upon UK businesses and citizens an ever-growing collection of fastidious regulations in every field".[222]

Thiemo Fetzer, professor of economics from University of Warwick, analyzed the welfare reforms in the UK since 2000 and suggests that numerous austerity-induced welfare reforms from 2010 onwards have stopped contributing to mitigate income differences through transfer payments. This could be a key activating factor of anti-EU preferences that lie behind the development of economic grievances and the lack of support in a Remain victory.[223]

Michael Jacobs, the current director of the Commission on Economic Justice at the Institute for Public Policy Research and Mariana Mazzucato, a professor in University College London in Economics of Innovation and Public Value have found that the Brexit campaign had the tendency to blame external forces for domestic economic problems and have argued that the problems within the economy wasn't due to 'unstoppable forces of globalisation' but rather the result of active political and business decisions. Instead, they claim that orthodox economic theory has guided poor economic policy such as investment and that has been the cause of problems within the British economy.[224]

Institute for Fiscal Studies

[edit]In May 2016, the Institute for Fiscal Studies said that an EU exit could mean two more years of austerity cuts as the government would have to make up for an estimated loss of £20 billion to £40 billion of tax revenue. The head of the IFS, Paul Johnson, said that the UK "could perfectly reasonably decide that we are willing to pay a bit of a price for leaving the EU and regaining some sovereignty and control over immigration and so on. That there would be some price though, I think is now almost beyond doubt."[225]

Lawyers

[edit]A poll of lawyers conducted by a legal recruiter in late May 2016 suggested 57% of lawyers wanted to remain in the EU.[226]

During a Treasury Committee shortly following the vote, economic experts generally agreed that the leave vote would be detrimental to the UK economy.[227]

Michael Dougan, Professor of European Law and Jean Monnet Chair in EU Law at the University of Liverpool and a constitutional lawyer, described the Leave campaign as "one of the most dishonest political campaigns this country [the UK] has ever seen", for using arguments based on constitutional law that he said were readily demonstrable as false.[228]

NHS officials

[edit]Simon Stevens, head of NHS England, warned in May 2016 that a recession following a Brexit would be "very dangerous" for the National Health Service, saying that "when the British economy sneezes, the NHS catches a cold."[229] Three-quarters of a sample of NHS leaders agreed that leaving the EU would have a negative effect on the NHS as a whole. In particular, eight out of 10 respondents felt that leaving the EU would have a negative impact on trusts' ability to recruit health and social care staff.[230] In April 2016, a group of nearly 200 health professionals and researchers warned that the NHS would be in jeopardy if Britain left the European Union.[231] The leave campaign reacted by saying more money would be available to be spent on the NHS if the UK left the EU.

British health charities

[edit]Guidelines by the Charity Commission for England and Wales that forbid political activity for registered charities have limited UK health organizations' commentary on EU poll, according to anonymous sources consulted by the Lancet.[232] According to Simon Wessely, head of psychological medicine at the Institute of Psychiatry, King's College London – neither a special revision of the guidelines from 7 March 2016, nor Cameron's encouragement have made health organisations, willing to speak out.[232] The Genetic Alliance UK the Royal College of Midwives the Association of the British Pharmaceutical Industry and the Chief Executive of the National Health Service had all stated pro-remain positions by early June 2016.[232]

Fishing industry

[edit]A June 2016 survey of British fishermen found that 92% intended to vote to leave the EU.[233] The EU's Common Fisheries Policy was mentioned as a central reason for their near-unanimity.[233] More than three-quarters believed that they would be able to land more fish, and 93% stated that leaving the EU would benefit the fishing industry.[234]

Historians

[edit]In May 2016, more than 300 historians wrote in a joint letter to The Guardian that Britain could play a bigger role in the world as part of the EU. They said: "As historians of Britain and of Europe, we believe that Britain has had in the past, and will have in the future, an irreplaceable role to play in Europe."[235] On the other hand, many historians argued in favour of leaving, seeing it as a return to self-sovereignty.[236][237]

Exit plan competition

[edit]Following David Cameron's announcement of an EU referendum, in July 2013 the Institute of Economic Affairs (IEA) announced the "Brexit Prize", a competition to find the best plan for a UK exit from the European Union, and declared that a departure was a "real possibility" following the 2015 general election.[238] Iain Mansfield, a Cambridge graduate and UKTI diplomat, submitted the winning thesis: A Blueprint for Britain: Openness not Isolation.[239] Mansfield's submission focused on addressing both trade and regulatory issues with EU member states as well as other global trading partners.[240][241]

Opinion polling

[edit]

Opinion polls from 2010 onwards suggested the British public were relatively evenly divided on the question, with opposition to EU membership peaking in November 2012 at 56% compared with 30% who prefer to remain in,[242] while in June 2015 those in favour of Britain remaining in the EU reached 43% versus those opposed 36%.[243] The largest ever poll (of 20,000 people, in March 2014) showed the public evenly split on the issue, with 41% in favour of withdrawal, 41% in favour of membership, and 18% undecided.[244] However, when asked how they would vote if Britain renegotiated the terms of its membership of the EU, and the UK Government stated that British interests had been satisfactorily protected, more than 50% indicated that they would vote for Britain to stay in.[245]

Analysis of polling suggested that young voters tended to support remaining in the EU, whereas those older tend to support leaving, but there was no gender split in attitudes.[246][247] In February 2016 YouGov also found that euroscepticism correlated with people of lower income and that "higher social grades are more clearly in favour of remaining in the EU", but noted that euroscepticism also had strongholds in "the more wealthy, Tory shires".[248] Scotland, Wales and many English urban areas with large student populations were more pro-EU.[248] Big business was broadly behind remaining in the EU, though the situation among smaller companies was less clear-cut.[249] In polls of economists, lawyers, and scientists, clear majorities saw the UK's membership of the EU as beneficial.[250][251][252][253][254] On the day of the referendum, the bookmaker Ladbrokes offered odds of 6/1 against the UK leaving the EU.[255] Meanwhile, spread betting firm Spreadex offered a Leave Vote Share spread of 45–46, a Remain Vote Share spread of 53.5-54.5, and a Remain Binary Index spread of 80–84.7, where victory for Remain would makeup to 100 and a defeat 0.[256]

On the day YouGov poll

[edit]| Remain | Leave | Undecided | Lead | Sample | Conducted by |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 52% | 48% | N/A | 4% | 4,772 | YouGov |

Shortly after the polls closed at 10 pm on 23 June, the British polling company YouGov released a poll conducted among almost 5,000 people on the day; it suggested a narrow lead for "Remain", which polled 52% with Leave polling 48%. It was later criticised for overestimating the margin of the "Remain" vote,[257] when it became clear a few hours later that the UK had voted 51.9% to 48.1% in favour of leaving the European Union.

Issues

[edit]The number of jobs lost or gained by a withdrawal was a dominant issue; the BBC's outline of issues warned that a precise figure was difficult to find. The Leave campaign argued that a reduction in red tape associated with EU regulations would create more jobs and that small to medium-sized companies who trade domestically would be the biggest beneficiaries. Those arguing to remain in the EU, claimed that millions of jobs would be lost. The EU's importance as a trading partner and the outcome of its trade status if it left was a disputed issue. Whereas those wanting to stay cited that most of the UK's trade was made with the EU, those arguing to leave say that its trade was not as important as it used to be. Scenarios of the economic outlook for the country if it left the EU were generally negative. The United Kingdom also paid more into the EU budget than it received.[258]

Citizens of EU countries, including the United Kingdom, have the right to travel, live and work within other EU countries, as free movement is one of the four founding principles of the EU.[259] Campaigners for remaining said that EU immigration had positive impacts on the UK's economy, citing that the country's growth forecasts were partly based upon continued high levels of net immigration.[258] The Office for Budget Responsibility also claimed that taxes from immigrants boost public funding.[258] A recent[when?] academic paper suggests that migration from Eastern Europe put pressure on wage growth at the lower end of the wage distribution, while at the same time increasing pressures on public services and housing.[260] The Leave campaign believed reduced immigration would ease pressure in public services such as schools and hospitals, as well as giving British workers more jobs and higher wages.[258] According to official Office for National Statistics data, net migration in 2015 was 333,000, which was the second highest level on record, far above David Cameron's target of tens of thousands.[261][262] Net migration from the EU was 184,000.[262] The figures also showed that 77,000 EU migrants who came to Britain were looking for work.[261][262]

After the announcement had been made as to the outcome of the referendum, Rowena Mason, political correspondent for The Guardian offered the following assessment: "Polling suggests discontent with the scale of migration to the UK has been the biggest factor pushing Britons to vote out, with the contest turning into a referendum on whether people are happy to accept free movement in return for free trade."[263] A columnist for The Times, Philip Collins, went a step further in his analysis: "This was a referendum about immigration disguised as a referendum about the European Union."[264]

The Conservative MEP (Member of the European Parliament) representing South East England, Daniel Hannan, predicted on the BBC programme Newsnight that the level of immigration would remain high after Brexit.[265] "Frankly, if people watching think that they have voted and there is now going to be zero immigration from the EU, they are going to be disappointed. ... you will look in vain for anything that the Leave campaign said at any point that ever suggested there would ever be any kind of border closure or drawing up of the drawbridge."[266]

The EU had offered David Cameron a so-called "emergency brake" which would have allowed the UK to withhold social benefits to new immigrants for the first four years after they arrived; this brake could have been applied for a period of seven years."[267] That offer was still on the table at the time of the Brexit referendum, but expired when the vote determined that the UK would leave the EU.[268]

The possibility that the UK's smaller constituent countries could vote to remain within the EU but find themselves withdrawn from the EU led to discussion about the risk to the unity of the United Kingdom.[269] Scotland's First Minister, Nicola Sturgeon, made it clear that she believed that a second independence referendum would "almost certainly" be demanded by Scots if the UK voted to leave the EU but Scotland did not.[270] The First Minister of Wales, Carwyn Jones, said: "If Wales votes to remain in [the EU] but the UK votes to leave, there will be a... constitutional crisis. The UK cannot possibly continue in its present form if England votes to leave and everyone else votes to stay".[271]

There was concern that the Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership (TTIP), a proposed trade agreement between the United States and the EU, would be a threat to the public services of EU member states.[272][273][274][275] Jeremy Corbyn, on the Remain side, said that he pledged to veto TTIP in Government.[276] John Mills, on the Leave side, said that the UK could not veto TTIP because trade pacts were decided by Qualified Majority Voting in the European Council.[277]

There was debate over the extent to which the European Union membership aided security and defence in comparison to the UK's membership of NATO and the United Nations.[278] Security concerns over the union's free movement policy were raised too, because people with EU passports were unlikely to receive detailed checks at border control.[279]

Debates, question and answer sessions, and interviews

[edit]A debate was held by The Guardian on 15 March 2016, featuring the leader of UKIP Nigel Farage, Conservative MP Andrea Leadsom, the leader of Labour's "yes" campaign Alan Johnson and former leader of the Liberal Democrats Nick Clegg.[280]

Earlier in the campaign, on 11 January, a debate took place between Nigel Farage and Carwyn Jones, who was at the time the First Minister of Wales and leader of the Welsh Labour Party.[281][282] Reluctance to have Conservative Party members argue against one another has seen some debates split, with Leave and Remain candidates interviewed separately.[283]

The Spectator held a debate hosted by Andrew Neil on 26 April, which featured Nick Clegg, Liz Kendall and Chuka Umunna arguing for a remain vote, and Nigel Farage, Daniel Hannan and Labour MP Kate Hoey arguing for a leave vote.[284] The Daily Express held a debate on 3 June, featuring Nigel Farage, Kate Hoey and Conservative MP Jacob Rees-Mogg debating Labour MPs Siobhain McDonagh and Chuka Umunna and businessman Richard Reed, co-founder of Innocent drinks.[285] Andrew Neil presented four interviews ahead of the referendum. The interviewees were Hilary Benn, George Osborne, Nigel Farage and Iain Duncan Smith on 6, 8, 10 and 17 May, respectively on BBC One.[286]

The scheduled debates and question sessions included a number of question and answer sessions with various campaigners.[287][288] and a debate on ITV held on 9 June that included Angela Eagle, Amber Rudd and Nicola Sturgeon for remain, Boris Johnson, Andrea Leadsom, and Gisela Stuart for leave.[289]

EU Referendum: The Great Debate was held at Wembley Arena on 21 June and hosted by David Dimbleby, Mishal Husain and Emily Maitlis in front of an audience of 6,000.[290] The audience was split evenly between both sides. Sadiq Khan, Ruth Davidson and Frances O'Grady appeared for Remain. Leave was represented by the same trio as the ITV debate on 9 June (Johnson, Leadsom and Stuart).[291] Europe: The Final Debate with Jeremy Paxman was held the following day on Channel 4.[292]

| 2016 United Kingdom European Union membership referendum debates in Great Britain | |||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Date | Broadcaster | Host | Format | Venue | Territory | Viewing figures (million) |

P Present NI Not invited A Absent N No debate | ||||||||||

| Leave | Remain | ||||||||||||||||

| 26 April | The Spectator | Andrew Neil | Debate | London Palladium | UK | TBA | Nigel Farage Daniel Hannan Kate Hoey |

Nick Clegg Liz Kendall Chuka Umunna | |||||||||

| 3 June | Daily Express | Greg Heffer | Debate | Thames Street, London | UK | TBA | Nigel Farage Kate Hoey Jacob Rees-Mogg |

Siobhain McDonagh Chuka Umunna Richard Reed | |||||||||

| 15 June | BBC (Question Time) | David Dimbleby | Individual | Nottingham | UK | TBA | Michael Gove | NI | |||||||||

| 19 June | BBC (Question Time) | David Dimbleby | Individual | Milton Keynes | UK | TBA | NI | David Cameron | |||||||||

| 21 June | BBC | David Dimbleby Mishal Husain Emily Maitlis |

Debate | SSE Arena | UK | TBA | Boris Johnson Andrea Leadsom Gisela Stuart |

Sadiq Khan Ruth Davidson Frances O'Grady | |||||||||

Voting, voting areas, and counts

[edit]

Voting took place from 0700 BST (WEST) until 2200 BST (same hours CEST in Gibraltar) in 41,000 polling stations across 382 voting areas, with each polling station limited to a maximum of 2,500 voters.[293] The referendum was held across all four countries of the United Kingdom, as well as in Gibraltar, as a single majority vote. The 382 voting areas were grouped into twelve regional counts and there was separate declarations for each of the regional counts.

In England, as happened in the 2011 AV referendum, the 326 districts were used as the local voting areas and the returns of these then fed into nine English regional counts. In Scotland the local voting areas were the 32 local councils which then fed their results into the Scottish national count, and in Wales the 22 local councils were their local voting areas before the results were then fed into the Welsh national count. Northern Ireland, as was the case in the AV referendum, was a single voting and national count area although local totals by Westminster parliamentary constituency areas were announced.

Gibraltar was a single voting area, but as Gibraltar was to be treated and included as if it were a part of South West England, its results was included together with the South West England regional count.[293]

The following table shows the breakdown of the voting areas and regional counts that were used for the referendum.[293]

| Country | Counts and voting areas |

|---|---|

| United Kingdom (together with Gibraltar, treated as if it were a [full] part of the United Kingdom) |

Referendum declaration; 12 regional counts; 382 voting areas (381 in the UK, 1 in Gibraltar) |

| Constituent countries | Counts and voting areas |

|---|---|

| England (together with Gibraltar, treated as if it were a part of South West England) |

9 regional counts; 327 voting areas (326 in the UK, 1 in Gibraltar) |

| Northern Ireland | National count and single voting area; 18 parliamentary constituency totals |

| Scotland | National count; 32 voting areas |

| Wales | National count; 22 voting areas |

Expat Disenfranchisement Legal Challenges

[edit]British expat Harry Shindler, a World War II veteran living in Italy, took legal action as the UK does not permit citizens residing abroad who have not lived in the UK for over 15 years to vote in elections. Shindler believed this prohibition violated his rights as he wished to vote in the referendum.[294] He had previously raised a case in 2009 (Shindler v. the United Kingdom 19840/09) regarding his rights to vote in UK general elections that the European Court of Human Rights (ECtHR) deemed did not violate his rights.[295]

UK High Court

[edit]Shindler first sued the UK government before the referendum, claiming that his disenfranchisement was a penalty against UK citizens who live abroad, exercising their EU right of free movement, thus violating his right as an EU citizen. This 15-year prohibition on voting, Shindler argued, discourages British citizens from continuing to exercise their free movement rights as they are required to return to the UK to vote in the EU referendum.[296]

The High Court, on 20 April 2016, rejected Shindler's claims, saying that it is "totally unrealistic" that the 15-year prohibition would deter citizens from settling in another Member State. The court also found that "significant practical difficulties" in allowing residents abroad for more than 15 years to vote permits the government to enact this restriction.[296]

Further, the High Court found that this prohibition, even if it did violate EU rights, is a parliamentary prerogative as "Parliament could legitimately take the view that electors who satisfy the test of closeness of connection set by the 15 year rule form an appropriate group to vote on the question whether the United Kingdom should remain a member of the European Union or leave the European Union."[296]

European Court of Justice

[edit]After the referendum, Shindler brought a case against the Council of the EU in the General Court. He argued that the Council's decision (Decision XT 21016/17) to recognize the referendum was illegal as his disenfranchisement invalidated the referendum.[297] Shindler argued that the decision lacked "definite constitutional authorization based on the votes of all UK citizens" as not all citizens were permitted to vote. He claims the Council should have "sought judicial review of the constitutionality of the notification of the intention to withdraw" because depriving UK citizens to vote in the referendum is contrary to EU law. Shindler claimed that "the Council should have refused or stayed the opening of negotiations" between the EU and the UK.[298]

In November 2018, however, the court found Shindler's arguments unconvincing as the decision to recognize the referendum did not "directly affect the legal situation of the applicants." The Council's action merely recognized and began the withdrawal procedures and did not violate Shinder's rights.[298]

Disturbances

[edit]On 16 June 2016, a pro-EU Labour MP, Jo Cox, was shot and killed in Birstall, West Yorkshire the week before the referendum by a man calling out "death to traitors, freedom for Britain", and a man who intervened was injured.[299] The two rival official campaigns agreed to suspend their activities as a mark of respect to Cox.[81] After the referendum, evidence emerged that Leave.EU had continued to put out advertising the day after Jo Cox's murder.[300][301] David Cameron cancelled a planned rally in Gibraltar supporting British EU membership.[302] Campaigning resumed on 19 June.[303][304] Polling officials in the Yorkshire and Humber region also halted counting of the referendum ballots on the evening of 23 June to observe a minute of silence.[305] The Conservative Party, Liberal Democrats, UK Independence Party and the Green Party all announced that they would not contest the ensuing by-election in Cox's constituency as a mark of respect.[306]

On polling day itself two polling stations in Kingston upon Thames were flooded by rain and had to be relocated.[307] In advance of polling day, concern had been expressed that the courtesy pencils provided in polling booths could allow votes to be later altered. Although this was widely dismissed as a conspiracy theory (see: Voting pencil conspiracy theory), some Leave campaigners advocated that voters should instead use pens to mark their ballot papers. On polling day in Winchester an emergency call was made to police about "threatening behaviour" outside the polling station. After questioning a woman who had been offering to lend her pen to voters, the police decided that no offence was being committed.[308]

Result

[edit]

The final result was announced on Friday 24 June 2016 at 07:20 BST by then-Electoral Commission Chairwoman Jenny Watson at Manchester Town Hall after all 382 voting areas and the twelve UK regions had declared their totals. With a national turnout of 72% across the United Kingdom and Gibraltar (representing 33,577,342 people), at least 16,788,672 votes were required to win a majority. The electorate voted to "Leave the European Union", with a majority of 1,269,501 votes (3.8%) over those who voted "Remain a member of the European Union".[309] The national turnout of 72% was the highest ever for a UK-wide referendum, and the highest for any national vote since the 1992 general election.[310][311][312][313] Roughly 38% of the UK population voted to leave the EU and roughly 35% voted to remain.[314]

| Choice | Votes | % |

|---|---|---|

| Leave the European Union | 17,410,742 | 51.89 |

| Remain a member of the European Union | 16,141,241 | 48.11 |

| Valid votes | 33,551,983 | 99.92 |

| Invalid or blank votes | 25,359 | 0.08 |

| Total votes | 33,577,342 | 100.00 |

| Registered voters/turnout | 46,500,001 | 72.21 |

| Source: Electoral Commission[315] | ||

| National referendum results (excluding invalid votes) | |

|---|---|

| Leave 17,410,742 (51.9%) |

Remain 16,141,241 (48.1%) |

| ▲ 50% | |

Results by region and constituent countries

[edit]| Referendum results by United Kingdom regions | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Region | Electorate | Voter turnout, of eligible |

Votes | Proportion of votes | Invalid votes | ||||

| Remain | Leave | Remain | Leave | ||||||

| East Midlands | 3,384,299 | 74.2% | 1,033,036 | 1,475,479 | 41.18% | 58.82% | 1,981 | ||

| East of England | 4,398,796 | 75.7% | 1,448,616 | 1,880,367 | 43.52% | 56.48% | 2,329 | ||

| Greater London | 5,424,768 | 69.7% | 2,263,519 | 1,513,232 | 59.93% | 40.07% | 4,453 | ||

| North East England | 1,934,341 | 69.3% | 562,595 | 778,103 | 41.96% | 58.04% | 689 | ||

| North West England | 5,241,568 | 70.0% | 1,699,020 | 1,966,925 | 46.35% | 53.65% | 2,682 | ||

| Northern Ireland | 1,260,955 | 62.7% | 440,707 | 349,442 | 55.78% | 44.22% | 374 | ||

| Scotland | 3,987,112 | 67.2% | 1,661,191 | 1,018,322 | 62.00% | 38.00% | 1,666 | ||

| South East England | 6,465,404 | 76.8% | 2,391,718 | 2,567,965 | 48.22% | 51.78% | 3,427 | ||

| South West England (inc Gibraltar) | 4,138,134 | 76.7% | 1,503,019 | 1,669,711 | 47.37% | 52.63% | 2,179 | ||

| Wales | 2,270,272 | 71.7% | 772,347 | 854,572 | 47.47% | 52.53% | 1,135 | ||

| West Midlands | 4,116,572 | 72.0% | 1,207,175 | 1,755,687 | 40.74% | 59.26% | 2,507 | ||

| Yorkshire and the Humber | 3,877,780 | 70.7% | 1,158,298 | 1,580,937 | 42.29% | 57.71% | 1,937 | ||

| Overall Total | |||||||||

| United Kingdom | 46,500,001 | 72.2% | 16,141,241 | 17,410,742 | 48.11% | 51.89% | 25,359 | ||

| Referendum results by United Kingdom constituent countries & Gibraltar | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Country | Electorate | Voter turnout, of eligible |

Votes | Proportion of votes | Invalid votes | ||||

| Remain | Leave | Remain | Leave | ||||||

| England | 38,981,662 | 73.0% | 13,247,674 | 15,187,583 | 46.59% | 53.41% | 22,157 | ||

| Gibraltar | 24,119 | 83.7% | 19,322 | 823 | 95.91% | 4.08% | 27 | ||

| Northern Ireland | 1,260,955 | 62.7% | 440,707 | 349,442 | 55.78% | 44.22% | 384 | ||

| Scotland | 3,987,112 | 67.2% | 1,661,191 | 1,018,322 | 62.00% | 38.00% | 1,666 | ||

| Wales | 2,270,272 | 71.7% | 772,347 | 854,572 | 47.47% | 52.53% | 1,135 | ||

| Overall Total | |||||||||

| United Kingdom | 46,500,001 | 72.2% | 16,141,241 | 17,410,742 | 48.11% | 51.89% | 25,359 | ||

Voter demographics and trends

[edit]Voting figures from local referendum counts and ward-level data (using local demographic information collected in the 2011 census) suggests that Leave votes were strongly correlated with lower qualifications and higher age.[316][317][318][319] The data were obtained from about one in nine wards in England and Wales, with very little information from Scotland and none from Northern Ireland.[316] A YouGov survey reported similar findings; these are summarised in the charts below.[320][321]

Researchers based at the University of Warwick found that areas with "deprivation in terms of education, income and employment were more likely to vote Leave". The Leave vote tended to be greater in areas which had lower incomes and high unemployment, a strong tradition of manufacturing employment, and in which the population had fewer qualifications.[322] It also tended to be greater where there was a large flow of Eastern European migrants (mainly low-skilled workers) into areas with a large share of native low-skilled workers.[322] Those in lower social grades (especially the 'working class') were more likely to vote Leave, while those in higher social grades (especially the 'upper middle class') were more likely to vote Remain.[323]

Polls by Ipsos MORI, YouGov and Lord Ashcroft all assert that 70–75% of under 25s voted 'remain'.[324] Additionally according to YouGov, only 54% of 25- to 49-year-olds voted 'remain', whilst 60% of 50- to 64-year-olds and 64% of over-65s voted 'leave', meaning that the support for 'remain' was not as strong outside the youngest demographic.[325] Also, YouGov found that around 87% of under-25s in 2018 would now vote to stay in the EU.[326] Opinion polling by Lord Ashcroft Polls found that Leave voters believed leaving the EU was "more likely to bring about a better immigration system, improved border controls, a fairer welfare system, better quality of life, and the ability to control our own laws", while Remain voters believed EU membership "would be better for the economy, international investment, and the UK's influence in the world".[327] Immigration is thought to be a particular worry for older people that voted Leave, who consider it a potential threat to national identity and culture.[328] The polling found that the main reasons people had voted Leave were "the principle that decisions about the UK should be taken in the UK", and that leaving "offered the best chance for the UK to regain control over immigration and its own borders". The main reason people voted Remain was that "the risks of voting to leave the EU looked too great when it came to things like the economy, jobs and prices".[327]