Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Bicycle frame

View on Wikipedia

A bicycle frame is the main component of a bicycle, onto which wheels and other components are fitted. The modern and most common frame design for an upright bicycle is based on the safety bicycle, and consists of two triangles: a main triangle and a paired rear triangle. This is known as the diamond frame.[1] Frames are required to be strong, stiff and light, which they do by combining different materials and shapes.[2]

A frameset consists of the frame and fork of a bicycle and sometimes includes the headset and seat post.[3] Frame builders will often produce the frame and fork together as a paired set.

Variations

[edit]

Besides the ubiquitous diamond frame,[1] many different frame types have been developed for the bicycle, several of which are still in common use today.

Diamond

[edit]In the diamond frame, the main "triangle" is not actually a triangle because it consists of four tubes: the head tube, top tube, down tube and seat tube. The rear triangle consists of the seat tube joined by paired chain stays and seat stays.

The head tube contains the headset, the interface with the fork. The top tube connects the head tube to the seat tube at the top. The top tube may be positioned horizontally (parallel to the ground), or it may slope downwards towards the seat tube for additional stand-over clearance. The down tube connects the head tube to the bottom bracket shell.

The rear triangle connects to the rear fork ends, where the rear wheel is attached. It consists of the seat tube and paired chain stays and seat stays. The chain stays run connecting the bottom bracket to the rear fork ends. The seat stays connect the top of the seat tube (often at or near the same point as the top tube) to the rear fork ends.

Step-through

[edit]Historically, bicycle frames designed for women had a top tube that connected in the middle of the seat tube instead of the top, resulting in a lower standover height. This was to allow the rider to dismount while wearing a skirt or dress. The design has since been used in unisex utility bikes to facilitate easy mounting and dismounting, and is also known as a step-through frame or an open frame.[4] Another style that accomplishes similar results is the mixte.

Cantilever

[edit]In a cantilever bicycle frame the seat stays continue past the seat post and curve downwards to meet with the down tube.[5] Cantilever frames are popular on the cruiser bicycle, the lowrider bicycle, and the wheelie bike. In many cantilever frames the only straight tubes are the seat tube and the head tube.

Recumbent

[edit]The recumbent bicycle moves the cranks to a position forward of the rider instead of underneath, generally improving the slipstream around the rider without the characteristic sharp bend at the waist used by racers of diamond-frame bicycles. Banned from bicycle racing in France in 1934 to avoid rendering diamond-frame bicycles obsolete in racing,[6] manufacturing of recumbent bicycles remained depressed for another half century, but by 2000 many models were available from a range of manufacturers.

Prone

[edit]The uncommon prone bike moves the cranks to the rear of the rider, resulting in a head-forward, chest-down riding position.

Cross or girder

[edit]A cross frame consists mainly of two tubes that form a cross: a seat tube from the bottom bracket to the saddle, and a backbone from the head tube to the rear hub.[7]

Truss

[edit]A truss frame uses additional tubes to form a truss.[8] Examples include Humbers, Pedersens, and the one pictured.

Monocoque

[edit]A monocoque frame consists only of a hollow shell with no internal structure.[9]

Folding

[edit]

Folding bicycle frames are characterized by the ability to fold into a compact shape for transportation or storage.

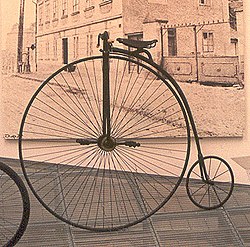

Penny-farthing

[edit]Penny-farthing frames are characterized by a large front wheel and a small rear wheel.[10][11]

Tandem and sociable

[edit]Tandem and sociable frames support multiple riders.

Others

[edit]There are many variations on the basic diamond frame design.

- Frames without seat tubes, such as the Trek Y-Foil, the Zipp 2001, the Kestrel Airfoil, and most frames by Softride.

- Frames without top tubes such as "Old Faithful" by Graeme Obree.

- Frames that use cables for members that are only under tension, such as the Dursley Pedersen bicycle pictured, the Pocket Bicycle, the 2009 Viva Wire,[12] the Wire Bike from designer Ionut Predescu,[13] or the Slingshot Bicycles fold-tech series.[14]

- Frames with hoops replacing the seat tube, chain stays and seat stays: called "roundtail"s.[15][16]

- The elevated chain stay bicycle was popular in the early 90s. It featured a rear triangle with elevated bottom frame stays, negating the need for the chain to be drawn through the rear frame. This allowed for a shorter wheelbase and improved handling during technical ascents, at the cost of compromised integrity and resultant increased bottom bracket flex (unless reinforced) compared to a frame with traditional chain stays.[17]

The cycle types article describes additional variations.

It is also possible to add couplers either during manufacturing or as a retrofit so that the frame can be disassembled into smaller pieces to facilitate packing and travel.

Frame tubes

[edit]The diamond frame consists of two triangles, a main triangle and a paired rear triangle. The main triangle consists of the head tube, top tube, down tube and seat tube. The rear triangle consists of the seat tube, and paired chain stays and seat stays.

Head tube

[edit]The head tube contains the headset, the bearings for the fork via its steerer tube. In an integrated headset, cartridge bearings interface directly with the surface on the inside of the head tube, on non-integrated headsets the bearings (in a cartridge or not) interface with "cups" pressed into the head tube.

Top tube

[edit]

The top tube,[18] or cross-bar,[19] connects the top of the head tube to the top of the seat tube.

In a traditional-geometry diamond frame, the top tube is horizontal (parallel to the ground). In a compact-geometry frame, the top tube is normally sloped downward toward the seat tube for additional standover clearance. In a mountain bike frame, the top tube is almost always sloped downward toward the seat tube. Radically sloped top tubes that compromise the integrity of the traditional diamond frame may require additional gusseting tubes, alternative frame construction, or different materials for equivalent strength.[20][21][22] (See Road and triathlon bicycles for more information on geometries.)

Step-through frames usually have a top tube that slopes down steeply to allow the rider to mount and dismount the bicycle more easily. Alternative step-through designs may include leaving out the top tube out completely, as in monocoque mainframe designs using a separated or hinged seat tube, and twin top tubes that continue to the rear fork ends as with the mixte frame. These alternatives to the diamond frame provide greater versatility, though at the expense of added weight to achieve equivalent strength and rigidity.[20][21]

Control cables are routed along mounts on the top tube, or sometimes inside the top tube. Most commonly, this includes the cable for the rear brake, but some mountain bikes and hybrid bicycles also route the front and rear derailleur cables along the top tube. Inside routing, once only present in the highest price ranges, protects the cables from damage and dirt, which can e.g. make gear shifting unreliable.[23]

The space between the top tube and the rider's groin while straddling the bike and standing on the ground is called clearance. The total height from the ground to this point is called the height lever.

Down tube

[edit]The down tube connects the head tube to the bottom bracket shell. On racing bicycles and some mountain and hybrid bikes, the derailleur cables run along the down tube, or inside the down tube. On older racing bicycles, the shift levers were mounted on the down tube. On newer ones, they are mounted with the brake levers on the handlebars.

Bottle cage mounts are also on the down tube, usually on the top side, sometimes also on the bottom side. In addition to bottle cages, small air pumps may be fitted to these mounts as well.

Seat tube

[edit]The seat tube contains the seatpost of the bike, which connects to the saddle. The saddle height is adjustable by changing how far the seatpost is inserted into the seat tube. On some bikes, this is achieved using a quick release lever. The seatpost must be inserted at least a certain length; this is marked with a minimum insertion mark.

The seat tube also may have braze-on mounts for a bottle cage or front derailleur.

Chain stays

[edit]The chain stays run parallel to the chain, connecting the bottom bracket shell (which holds the axis around which the pedals and cranks rotate) to the rear fork ends or dropouts. A shorter chain stay generally means that the bike will accelerate faster and be easier to ride uphill, at least while the rider can avoid the front wheel losing contact with the ground.[23]

When the rear derailleur cable is routed partially along the down tube, it is also routed along the chain stay. Occasionally (principally on frames made since the late 1990s) mountings for disc brakes will be attached to the chain stays. There may be a small brace that connects the chain stays in front of the rear wheel and behind the bottom bracket shell, called a "chainstay bridge".

Chain stays may be designed using tapered or untapered tubing. They may be relieved, ovalized, crimped, S-shaped, or elevated to allow additional clearance for the rear wheel, chain, crankarms, or the heel of the foot.

Seat stays

[edit]

The seat stays connect the top of the seat tube (often at or near the same point as the top tube) to the rear fork dropouts. A traditional frame uses a simple set of paralleled tubes connected by a bridge above the rear wheel. When the rear derailleur cable is routed partially along the top tube, it is also usually routed along the seat stay.

Many alternatives to the traditional seat stay design have been introduced over the years. A style of seat stay that extends forward of the seat tube, below the rear end of the top tube and connects to the top tube in front of the seat tube, creating a small triangle, is called a Hellenic stay after the British frame builder Fred Hellens, who introduced them in 1923.[24] Hellenic seat stays add aesthetic appeal at the expense of added weight. This style of seat stay was popularized again in the late 20th century by GT Bicycles (under the moniker "triple triangle"), who had incorporated the design element into their BMX frames, as it also made for a much stiffer rear triangle (an advantage in races); this design element has also been used on their mountain bike frames for similar reasons.

In 2012, a variation of the traditional seat stay that bypasses the seat tube and connects further into the top tube was patented by Volagi Cycles.[25] This frame element added length to the traditional design of seat stays, making a softer ride at the sacrifice of frame stiffness.

Another common seat stay variant is the wishbone, single seat stay, or mono stay,[26] which joins the stays together just above the rear wheel into a monotube that is joined to the seat tube. A wishbone design adds vertical rigidity without increasing lateral stiffness, generally an undesirable trait for bicycles with unsuspended rear wheels.[27] The wishbone design is most appropriate when used as part of a rear triangle subframe on a bicycle with independent rear suspension.

A dual seat stay refers to seat stays which meet the front triangle of the bicycle at two separate points, usually side-by-side.

Fastback seat stays meet the seat tube at the back instead of the sides of the tube.[28]

On most seat stays, a bridge or brace is typically used to connect the stays above the rear wheel and below the connection with the seat tube. Besides providing lateral rigidity, this bridge provides a mounting point for rear brakes, fenders, and racks. The seat stays themselves may also be fitted with brake mounts. Brake mounts are often absent from fixed-gear or track bike seat stays.

Bottom bracket shell

[edit]The bottom bracket shell is a short and large diameter tube, relative to the other tubes in the frame, that runs side to side and holds the bottom bracket. It is usually threaded, often left-hand threaded on the right (drive) side of the bike to prevent loosening by fretting induced precession, and right-hand threaded on the left (non-drive) side. There are many variations, such as an eccentric bottom bracket, which allows for adjustment in tension of the bicycle's chain. It is typically larger, unthreaded, and sometimes split. The chain stays, seat tube, and down tube all typically connect to the bottom bracket shell.

There are a few traditional standard shell widths (68, 70 or 73 mm).[29] Road bikes usually use 68 mm; Italian road bikes use 70 mm; Early model mountain bikes use 73 mm; later models (1995 and newer) use 68 mm more commonly. Some modern bicycles have shell widths of 83 or 100 mm and these are for specialised downhill mountain biking or snowbiking applications. The shell width influences the Q factor or tread of the bike. There are a few standard shell diameters (34.798 – 36 mm) with associated thread pitches (24 - 28 tpi).

On some gearbox bicycles, the bottom bracket shell may be replaced by an integrated gearbox or a mounting location for a detachable gearbox.

Frame geometry

[edit]The length of the tubes, and the angles at which they are attached define a frame geometry. In comparing different frame geometries, designers often compare the seat tube angle, head tube angle, (virtual) top tube length, and seat tube length. To complete the specification of a bicycle for use, the rider adjusts the relative positions of the saddle, pedals and handlebars:

- saddle height, the distance from the center of the bottom bracket to the point of reference on top of the middle of the saddle.[30]

- stack, the vertical distance from the center of the bottom bracket to the top of the head tube.[31]

- reach, the horizontal distance from the center of the bottom bracket to the top of the head tube.[32]

- bottom bracket drop, the distance by which the center of the bottom bracket lies below the level of the rear hub.[33]

- handlebar drop, the vertical distance between the reference at the top of the saddle to the handlebar.[34]

- saddle setback, the horizontal distance between the front of the saddle and the center of the bottom bracket.[35]

- standover height, the height of the top tube above the ground.[36]

- front center, the distance from the center of the bottom bracket to the center of the front hub.[37]

- toe overlap, the amount that the feet can interfere with steering the front wheel.[38]

The geometry of the frame depends on the intended use. For instance, a road bicycle will place the handlebars in a lower and further position relative to the saddle giving a more crouched riding position; whereas a utility bicycle emphasizes comfort and has higher handlebars resulting in an upright riding position.

Frame geometry also affects handling characteristics. For more information, see the articles on bicycle and motorcycle geometry and bicycle and motorcycle dynamics.

Frame size

[edit]

Frame size was traditionally measured along the seat tube from the center of the bottom bracket to the center of the top tube. Typical "medium" sizes are 54 or 56 cm (approximately 21.2 or 22 inches) for a European men's racing bicycle or 46 cm (about 18.5 inches) for a men's mountain bike. The wider range of frame geometries that now exist has also led to other methods of measuring frame size.[39] Touring frames tend to be longer, whilst racing frames are more compact.

Road and triathlon bicycles

[edit]A road racing bicycle is designed for efficient power transfer at minimum weight and drag. Broadly speaking, the road bicycle geometry is categorized as either a traditional geometry with a horizontal top tube, or a compact geometry with a sloping top tube.

Traditional geometry road frames are often associated with more comfort and greater stability, and tend to have a longer wheelbase which contributes to these two aspects. Compact geometry allows the top of the head tube to be above the top of the seat tube, decreasing standover height, and thus increasing standover clearance and lowering the center of gravity. Opinion is divided on the riding merits of the compact frame, but several manufacturers claim that a reduced range of sizes can fit most riders, and that it is easier to build a frame without a perfectly level top tube.

Road bicycles for racing tend to have a steeper seat tube angle, measured from the horizontal plane. This positions the rider aerodynamically and arguably in a stronger stroking position. The trade-off is comfort. Touring and comfort bicycles tend to have more slack (less vertical) seat tube angle traditionally. This positions the rider more on the sit bones and takes weight off the wrists, arms and neck, and, for men, improves circulation to the urinary and reproductive areas. With a slacker angle, designers lengthen the chain stay so that the center of gravity (that would otherwise be farther to the back over the wheel) is more ideally repositioned over the middle of the bike frame. The longer wheelbase contributes to effective shock absorption. In modern mass-manufactured touring and comfort bikes, the seat-tube angle is negligibly slacker, perhaps in order to reduce manufacturing costs by avoiding the need to reset welding jigs in automated processes, and thus do not provide the comfort of traditionally made or custom-made frames which do have noticeably slacker seat-tube angles.

Road racing bicycles that are used in UCI-sanctioned races are governed by UCI regulations, which state among other things that the frame must consist of two triangles. Hence designs that lack a seat tube or top tube are not allowed.

Triathlon- or time-trial-specific frames rotate the rider forward around the axis of the bottom bracket of the bicycle as compared to the standard road bicycle frame. This is in order to put the rider in an even lower, more aerodynamic position. While handling and stability is reduced, these bicycles are designed to be ridden in environments with less group riding aspects. These frames tend to have steep seat-tube angles and low head tubes, and shorter wheelbase for the correct reach from the saddle to the handlebar. Additionally, since they are not governed by the UCI, some triathlon bicycles, such as the Zipp 2001, Cheetah and Softride, have non-traditional frame layouts, which can produce better aerodynamics.

Track bicycles

[edit]Track frames have much in common with road and time trial frames, but come with horizontal, rear-facing, rear fork ends,[40] rather than dropouts,[41] to allow one to adjust the position of the rear wheel horizontally to set the proper chain tension. Rear hub spacing is 120 millimetres (4.7 in) rather than 130 millimetres (5.1 in) or more for road frames. Bottom bracket drop is smaller, typically 50–60 millimetres (2.0–2.4 in). Also the seat tube angle is steeper than on road racing bikes.

Mountain bicycles

[edit]For ride comfort and better handling, shock absorbers are often used; there are a number of variants, including full suspension models, which provide shock absorption for the front and rear wheels; and front suspension only models (hardtails) which deal only with shocks arising from the front wheel. The development of sophisticated suspension systems in the 1990s quickly resulted in many modifications to the classic diamond frame.

Recent[when?] mountain bicycles with rear suspension systems have a pivoting rear triangle to actuate the rear shock absorber. There is much manufacturer variation in the frame design of full-suspension mountain bicycles, and different designs for different riding purposes.

Roadster/utility bicycles

[edit]Roadster bicycles traditionally have a fairly slack seat-tube and head-tube angle of about 66 or 67 degrees, which produces a very comfortable and upright "sit-up-and-beg" riding position. Other characteristics include a long wheelbase, upwards of 40 inches (often between 43 and 47 inches, or 57 inches for a longbike), and a long fork rake, often of about 3 inches (76mm compared to 40mm for most road bicycles). This style of frame has had a resurgence in popularity in recent years due to its greater comfort compared to Mountain bicycles or Road bicycles. A variation on this type of bicycle is the "sports roadster" (also known as the "light roadster"), which typically has a lighter frame, and a slightly steeper seat-tube and head-tube angle of about 70 to 72 degrees.

Frame materials

[edit]Historically, the most common material for the tubes of a bicycle frame has been steel. Steel frames can be made of varying grades of steel, from very inexpensive carbon steel to more costly and higher quality chromium molybdenum steel alloys. Frames can also be made from aluminum alloys, titanium, carbon fiber, and even bamboo and cardboard. Occasionally, diamond (shaped) frames have been formed from sections other than tubes. These include I-beams and monocoque. Materials that have been used in these frames include wood (solid or laminate), magnesium (cast I-beams), and thermoplastic. Several properties of a material help decide whether it is appropriate in the construction of a bicycle frame:

- Density (or specific gravity) is a measure of how light or heavy the material per unit volume.

- Stiffness (or elastic modulus) can in theory affect the ride comfort and power transmission efficiency. In practice, because even a very flexible frame is much more stiff than the tires and saddle, ride comfort is ultimately more a factor of saddle choice, frame geometry, tire choice, and bicycle fit. Lateral stiffness is far more difficult to achieve because of the narrow profile of a frame, and too much flexibility can affect power transmission, primarily through tire scrub on the road due to rear triangle distortion, brakes rubbing on the rims and the chain rubbing on gear mechanisms. In extreme cases gears can change themselves when the rider applies high torque out of the saddle.

- Yield strength determines how much force is needed to permanently deform the material (for crashworthiness).

- Elongation determines how much deformity the material allows before cracking (for crash-worthiness).

- Fatigue limit and Endurance limit determines the durability of the frame when subjected to cyclical stress from pedaling or ride bumps.

Tube engineering and frame geometry can overcome much of the perceived shortcomings of these particular materials.

Frame materials are listed by commonality of usage.

Steel

[edit]

Steel frames are often built using various types of steel alloys including chromoly. They are strong, easy to work, and relatively inexpensive. However, they are denser (and thus generally heavier) than many other structural materials. It is common (as of 2018, in hybrid commuter bikes) to use steel for the fork blades even when the rest of the frame is made of a different material, because steel offers better vibration dampening.[23]

A classic type of construction for both road bicycles and mountain bicycles uses standard cylindrical steel tubes which are connected with lugs. Lugs are fittings made of thicker pieces of steel. The tubes are fitted into the lugs, which encircle the end of the tube, and are then brazed to the lug. Historically, the lower temperatures associated with brazing (silver brazing in particular) had less of a negative impact on the tubing strength than high temperature welding, allowing relatively light tube to be used without loss of strength. Recent advances in metallurgy ("Air-hardening steel") have created tubing that is not adversely affected, or whose properties are even improved by high temperature welding temperatures, which has allowed both TIG & MIG welding to sideline lugged construction in all but a few high end bicycles. More expensive lugged frame bicycles have lugs which are filed by hand into fancy shapes - both for weight savings and as a sign of craftsmanship. Unlike MIG or TIG welded frames, a lugged frame can be more easily repaired in the field due to its simple construction. Also, since steel tubing can rust (although in practice paint and anti-corrosion sprays can effectively prevent rust), the lugged frame allows a fast tube replacement with virtually no physical damage to the neighbouring tubes.[42][43]

A more economical method of bicycle frame construction uses cylindrical steel tubing connected by TIG welding, which does not require lugs to hold the tubes together. Instead, frame tubes are precisely aligned into a jig and fixed in place until the welding is complete. Fillet brazing is another method of joining frame tubes without lugs. It is more labor-intensive, and consequently is less likely to be used for production frames. As with TIG welding, Fillet frame tubes are precisely notched or mitered[44][45] and then a fillet of brass is brazed onto the joint, similar to the lugged construction process. A fillet braze frame can achieve more aesthetic unity (smooth curved appearance) than a welded frame.

Among steel frames, using butted tubing reduces weight and increases cost. Butting means that the wall thickness of the tubing changes from thick at the ends (for strength) to thinner in the middle (for lighter weight).

Cheaper steel bicycle frames are made of mild steel, also called high tensile steel, such as might be used to manufacture automobiles or other common items. However, higher-quality bicycle frames are made of high strength steel alloys (generally chromium-molybdenum, or "chromoly" steel alloys) which can be made into lightweight tubing with very thin wall gauges. One of the most successful older steels was Reynolds "531", a manganese-molybdenum alloy steel. More common now is 4130 ChroMoly or similar alloys. Reynolds and Columbus are two of the most famous manufacturers of bicycle tubing. A few medium-quality bicycles used these steel alloys for only some of the frame tubes. An example was the Schwinn Le tour (at least certain models), which used chromoly steel for the top and bottom tubes but used lower-quality steel for the rest of the frame.

A high-quality steel frame is generally lighter than a regular steel frame. All else being equal, this loss of weight can improve the acceleration and climbing performance of the bicycle.

If the tubing label has been lost, a high-quality (chromoly or manganese) steel frame can be recognized by tapping it sharply with a flick of the fingernail. A high-quality frame will produce a bell-like ring where a regular-quality steel frame will produce a dull thunk. They can also be recognized by their weight (around 2.5 kg for frame and forks) and the type of lugs and fork ends used.

Aluminum alloys

[edit]

Aluminum alloys have a lower density and lower strength compared with steel alloys; however, they possess a better strength-to-weight ratio, giving them notable weight advantages over steel. Early aluminum structures have shown to be more vulnerable to fatigue, either due to ineffective alloys, or imperfect welding technique being used. This contrasts with some steel and titanium alloys, which have clear fatigue limits and are easier to weld or braze together. However, some of these disadvantages have since been mitigated with more skilled labor capable of producing better quality welds, automation, and the greater accessibility to modern aluminum alloys. Aluminum's attractive strength to weight ratio as compared to steel, and certain mechanical properties, assure it a place among the favored frame-building materials.

Popular alloys for bicycle frames are 6061 aluminum and 7005 aluminum.

The most popular type of construction today uses aluminum alloy tubes that are connected together by Tungsten Inert Gas (TIG) welding. Welded aluminum bicycle frames started to appear in the marketplace only after this type of welding became economical in the 1970s.

Aluminum has a different optimal wall thickness to tubing diameter from steel. It is at its strongest at around 200:1 (diameter:wall thickness), whereas steel is a small fraction of that. However, at this ratio, the wall thickness would be comparable to that of a beverage can, far too fragile against impacts. Thus, aluminum bicycle tubing is a compromise, offering a wall thickness to diameter ratio that is not of utmost efficiency, but gives us oversized tubing of more reasonable aerodynamically acceptable proportions and good resistance to impact. This results in a frame that is significantly stiffer than steel. While many riders claim that steel frames give a smoother ride than aluminum because aluminum frames are designed to be stiffer, that claim is of questionable validity: the bicycle frame itself is extremely stiff vertically because it is made of triangles. Conversely, this very argument calls the claim of aluminum frames having greater vertical stiffness into question.[46] On the other hand, lateral and twisting (torsional) stiffness improves acceleration and handling in some circumstances.

Aluminum frames are generally recognized as having a lower weight than steel, although this is not always the case. A low quality aluminum frame may be heavier than a high quality steel frame. Butted aluminum tubes—where the wall thickness of the middle sections are made to be thinner than the end sections—are used by some manufacturers for weight savings. Non-round tubes are used for a variety of reasons, including stiffness, aerodynamics, and marketing. Various shapes focus on one or another of these goals, and seldom accomplish all.

Titanium

[edit]

Titanium is a relatively specialised material for bicycle frames. It has many desirable characteristics including a high specific strength, high fatigue limit, and excellent corrosion resistance.[47] While not as light as carbon fiber, titanium bicycles can provide a more pleasant ride quality, making the material popular among cyclists seeking comfort over performance.[48][49] However, titanium has a high material cost and is more difficult to machine than steel or aluminum, which translates to relatively expensive frames compared to steel, aluminum, and carbon fiber.[48][49]

Titanium frames typically use titanium alloys and tubes that were originally developed for the aerospace industry. The most commonly used alloy on titanium bicycle frames are 3AL-2.5V (3.5% aluminum and 2.5% vanadium), followed by 6AL-4V (6% aluminum and 4% vanadium). Some manufacturers are experimenting with other alloys designed specifically for cycling.[47][49] Tubes can be cold-drawn and hydroformed into various shapes and allow for internal cabling.[50] Welding is typically done in inert conditions to protect the welds from oxidation.[48][50]

Carbon fiber

[edit]

Carbon fiber composite is a popular non-metallic material commonly used for bicycle frames.[51][52][53][54] Although expensive, it is light-weight, corrosion-resistant and strong, and can be formed into almost any shape desired. The result is a frame that can be fine-tuned for specific strength where it is needed (to withstand pedaling forces), while allowing flexibility in other frame sections (for comfort). Custom carbon fiber bicycle frames may even be designed with individual tubes that are strong in one direction (such as laterally), while compliant in another direction (such as vertically). The ability to design an individual composite tube with properties that vary by orientation cannot be accomplished with any metal frame construction commonly in production.[55] Some carbon fiber frames use cylindrical tubes that are joined with adhesives and lugs, in a method somewhat analogous to a lugged steel frame. Another type of carbon fiber frames are manufactured in a single piece, called monocoque construction.

In one series of tests conducted by Santa Cruz Bicycles, it was shown that for a frame design with identical shape and nearly similar weight, the carbon frame is considerably stronger than aluminum, when subjected to an overall force load (subjecting the frame to both tension and compression), and impact strength.[56] While carbon frames can be lightweight and strong, they may have lower impact resistance compared to other materials, and can be prone to damage if crashed or mishandled. Cracking and failure can result from a collision, but also from over tightening or improperly installing components.[57] It has been suggested that these materials may be vulnerable to fatigue failure, a process which occurs with use over a long period of time,[58] though this is often limited to interlaminar cracks or cracks in adhesive at joints, where stresses can be well controlled with good design practices. It is possible for broken carbon frames to be repaired, but because of safety concerns it should be done only by professional firms to the highest possible standards.[59]

Many racing bicycles built for individual time trial races and triathlons employ composite construction because the frame can be shaped with an aerodynamic profile not possible with cylindrical tubes, or would be excessively heavy in other materials. While this type of frame may in fact be heavier than others, its aerodynamic efficiency may help the cyclist to attain a higher overall speed.

Other materials besides carbon fiber, such as metallic boron, can be added to the matrix to enhance stiffness further.[citation needed] Some newer high end frames are incorporating Kevlar fibers into the carbon weaves to improve vibration damping and impact strength, particularly in downtubes, seat stays, and chain stays.

Thermoplastic

[edit]

Thermoplastics are a category of polymers that can be reheated and reshaped, and there are several ways that they can be used to create a bicycle frame. One implementation of thermoplastic bicycle frames are essentially carbon fiber frames with the fibers embedded in a thermoplastic material rather than the more common thermosetting epoxy materials. GT Bicycles was one of the first major manufacturers to produce a thermoplastic frame with their STS System frames in the mid 1990s. The carbon fibers were loosely woven into a tube along with fibers of thermoplastic. This tube was placed into a mould with a bladder inside which was then inflated to force the carbon and plastic tube against the inside of the mould. The mould was then heated to melt the thermoplastic. Once the thermoplastic cooled it was removed from the mould in its final form.

Magnesium

[edit]A handful of bicycle frames are made from magnesium, which has around 64% the density of aluminum. In the 1980s, an engineer, Frank Kirk, devised a novel form of frame that was die cast in one piece and composed of I beams rather than tubes. A company, Kirk Precision Ltd, was established in Britain to manufacture both road bike and mountain bike frames with this technology. However, despite some early commercial success, there were problems with reliability and manufacture stopped in 1992.[60] The small number of modern magnesium frames in production are constructed conventionally using tubes.[61]

Scandium aluminum alloy

[edit]Some manufacturers of bikes make frames out of aluminum alloys containing scandium, usually referred to simply as scandium for marketing purposes although the Sc content is less than 0.5%. Scandium improves the welding characteristics of some aluminum alloys with superior fatigue resistance permitting the use of smaller diameter tubing, allowing for more frame design flexibility.

Beryllium

[edit]American Bicycle Manufacturing of St. Cloud, Minnesota, briefly offered a frameset made of beryllium tubes (bonded to aluminum lugs), priced at $26,000. Reports were that the ride was very harsh, but the frame was also very laterally flexible.[62]

Bamboo

[edit]Several bicycle frames have been made of bamboo tubes connected with metal or composite joinery. Aesthetic appeal has often been as much of a motivator as mechanical characteristics.[63][64]

Wood

[edit]Several bicycle frames have been made of wood, either solid or laminate. Although one survived 265 grueling kilometers of the Paris–Roubaix race, aesthetic appeal has often been as much of a motivator as ride characteristics.[65] Wood is used to fashion bicycles in East Africa.[66] Cardboard has also been used for bicycle frames.[67]

Combinations

[edit]

Combining different materials can provide the desired stiffness, compliance, or damping in different areas better than can be accomplished with a single material. The combined materials are usually carbon fiber and a metal, either steel, aluminum, or titanium. One implementation of this approach includes a metal down tube and chain stays with carbon top tube, seat tube, and seat stays.[68] Another is a metal main triangle and chain stays with just carbon seat stays.[69] Carbon forks have become very common on racing bicycles of all frame materials.[70]

Other

[edit]The bicycle types article describes additional variations.

Butted tubing

[edit]Butted tubing has increased thickness near the joints for strength while keeping weight low with thinner material elsewhere. For example, triple butted means the tube, usually of an aluminum alloy, has three different thicknesses, with the thicker sections at the end where they are welded. The same material can be used in handlebars.

Braze-ons

[edit]A variety of small features—bottle cage mounting holes, shifter bosses, cable stops, pump pegs, cable guides, etc.—are described as braze-ons because they were originally, and sometimes still are, brazed on.[71]

Suspension

[edit]Many bicycles, especially mountain bikes, have suspension.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b Brown, Sheldon. "Glossary: Diamond Frame". Retrieved 16 February 2013.

- ^ Lin, Chien-Cheng; Huang, Song-Jeng; Liu, Chi-Chia (2017). "Structural analysis and optimization of bicycle frame designs". Advances in Mechanical Engineering. 9 (12). doi:10.1177/1687814017739513.

- ^ "Sheldon Brown's Bicycle Glossary E - F". sheldonbrown.com. Retrieved 6 February 2017.

- ^ "Nimrod road tests the Jack Taylor touring bicycle". Cycling. March 16, 1960. Retrieved 2013-04-02.

Their range of seventeen models includes a woman's open frame bicycle.

- ^ Brown, Sheldon. "Sheldon Brown's Bicycle Glossary: Cantilever Frame". Archived from the original on 10 June 2011. Retrieved 2011-07-24.

- ^ Arnfried, Schmitz (June 1990). "Why your bicycle hasn't changed for 106 years". Cycling Science.

- ^ Brown, Sheldon. "Glossary: Cross Frame". Archived from the original on 13 May 2011. Retrieved 2011-05-04.

- ^ Kuner, Herbert. "Cross Frames". Archived from the original on 24 July 2011. Retrieved 2011-08-18.

Other names for bicycles with an extra reinforcing tube were girder frame or truss frame.

- ^ Brown, Sheldon. "Glossary: Cross Frame". Archived from the original on 14 May 2011. Retrieved 2011-05-04.

- ^ Schweikher, Erich; Diamond, Paul (2007). Cycling's Greatest Misadventures. Casagrande Press LLC. ISBN 9780976951629.

- ^ Inventions & Discoveries. BPI Publishing. ISBN 9788184972405.

- ^ "The Wire 2009 Viva Bike". Cool Material. 25 June 2009. Retrieved 2010-03-14.

- ^ Evans, Paul (March 9, 2009). "Wire Bike uses carbon fiber and Kevlar cables". GizMag. Retrieved 2010-03-14.

- ^ "Slingshot Bikes | Fold-Tech Cyclo-Cross Series". www.slingshotbikes.com. Retrieved 2017-08-04.

- ^ "Tortola Roundtail – A bicycle frame with a twist". BikeRadar. 11 Apr 2011. Retrieved 2011-04-11.

- ^ Viau, Jason (December 7, 2011). "Windsor-bred bike hits big time". The Windsor Star. Retrieved 2011-12-07.

The RoundTail bicycle is featured on the front of the January issue of Road Bike Action Magazine — one of the largest international bike publications with a global circulation of 90,000.

[permanent dead link] - ^ Van Der Plas, Rob (1995). Bicycle Technology (3rd ed.). Bicycle Books, San Francisco. pp. 62–63. ISBN 978-0-933201-30-9.

- ^ "Top Tube". Sheldon Brown. Archived from the original on 30 December 2009. Retrieved 2010-02-07.

- ^ Oxford English Dictionary (2nd ed.). Oxford University Press. 1989.

cross-bar, n. 1. a. A transverse bar; a bar placed or fixed across another bar or part of a structure. spec. The horizontal bar of a bicycle frame

- ^ a b Van Der Plas, Rob (1995). Bicycle Technology (3rd ed.). Bicycle Books, San Francisco. pp. 60–2. ISBN 978-0-933201-30-9.

- ^ a b Peterson, Leisha A.; Londry, Kelly J. (1986). "Finite-Element Structural Analysis: A New Tool for Bicycle Frame Design: The Strain Energy Design Method". Bicycling Magazine. 5 (2).

- ^ Wingerter, R., and Lebossiere, P., ME 354, Mechanics of Materials Laboratory: Structures, University of Washington (February 2004), p.1

- ^ a b c Ryan, Christine (2018-08-14). "The Best Hybrid Bike". The Wirecutter. Retrieved 2019-01-20.

- ^ "Sheldon Brown's Glossary". Archived from the original on 14 May 2008. Retrieved 2008-05-15.

- ^ "Volagi, LLC BICYCLE FRAMES AND BICYCLES Patent". Retrieved 2014-07-01.

- ^ "Sheldon Brown's Glossary". Archived from the original on 9 May 2008. Retrieved 2008-05-15.

- ^ Van Der Plas, Rob (1995). Bicycle Technology (3rd ed.). Bicycle Books, San Francisco. pp. 62. ISBN 978-0-933201-30-9.

Used on a bicycle with unsuspended rear wheel, the wishbone seat stay actually adds rigidity in the wrong direction - vertical rather than lateral stiffness.

- ^ "Sheldon Brown's Glossary". Archived from the original on 16 December 2008. Retrieved 2009-01-08.

- ^ Sheldon Brown's Bicycle Glossary, www.sheldonbrown.com, Accessed 29 November 2009.

- ^ "Saddle height". BikeCAD.ca. Retrieved 2014-04-02.

- ^ "Stack". BikeCAD.ca. Retrieved 2014-03-24.

- ^ "Reach". BikeCAD.ca. Retrieved 2014-03-24.

- ^ "Bottom bracket drop". BikeCAD.ca. Retrieved 2014-04-02.

- ^ "Handlebar drop". BikeCAD.ca. Retrieved 2014-04-02.

- ^ "Saddle setback". BikeCAD.ca. Retrieved 2014-03-24.

- ^ Brown, Sheldon. "Sheldon Brown's Glossary: Standover". Sheldon Brown. Retrieved 2009-04-10.

- ^ "Front center". BikeCAD.ca. Retrieved 2014-04-02.

- ^ "Bicycle Quarterly Glossary: Toe overlap". Archived from the original on 13 April 2009. Retrieved 2009-04-10.

- ^ Brown, Sheldon (2008). "Revisionist Theory of Bicycle Sizing". Harris Cyclery. www.sheldonbrown.com.

- ^ Brown, Sheldon. "Sheldon Brown's Glossary: Forkend". Sheldon Brown. Archived from the original on 5 January 2008. Retrieved 2008-01-06.

- ^ Brown, Sheldon. "Sheldon Brown's Glossary: Drop out". Sheldon Brown. Archived from the original on 13 January 2008. Retrieved 2008-01-06.

- ^ "A Lug Primer". rivbike.com. Archived from the original on 2020-01-22. Retrieved 2020-01-21.

- ^ "Bicycle Frame Repair at Yellow Jersey". yellowjersey.org. Archived from the original on 2020-01-22. Retrieved 2020-01-21.

- ^ Brown, Sheldon. "Sheldon Brown's Glossary: Miter, Mitre". Sheldon Brown. Archived from the original on 10 April 2008. Retrieved 2008-04-24.

- ^ "BikeCAD miter templates". Retrieved 2008-04-24.

- ^ "Bicycle Frame Materials - Stiffness and ride quality". Archived from the original on 3 July 2007. Retrieved 2007-06-30.

- ^ a b Vandermark, Robert (June 1997). "Opportunities for the Titanium Industry in Bicycles and Wheelchairs". JOM. 49 (6): 24–27. Bibcode:1997JOM....49f..24V. doi:10.1007/BF02914709. S2CID 109479575 – via SpringerLink.

- ^ a b c Marshall, Lee (February 28, 2019). "Why Serious Cyclists Are Paying More for Titanium Bikes". The Wall Street Journal. Retrieved December 31, 2021.

- ^ a b c Spender, James (April 21, 2016). "The life of Ti". Cyclist. Retrieved December 31, 2021.

- ^ a b Smythe, Simon (March 18, 2021). "Best titanium bikes reviewed and rated". Cycling Weekly. Retrieved December 31, 2021.

- ^ Brown, Sheldon. "Sheldon Brown: Frame Materials for the Touring Cyclist". Sheldon Brown. Archived from the original on 10 March 2007. Retrieved 2007-03-13.

- ^ "Bike Jargon Buster... Bike Frame Materials". WhyCycle?. Retrieved 29 May 2020.

- ^ "The Care Exchange: Material Assets. Titanium, Carbon Fibre, Aluminum or Steel - Which frame material is best for you?". Archived from the original on 17 April 2007. Retrieved 13 March 2007.

- ^ "Why Titanium? :What matters?". Archived from the original on 2006-11-19. Retrieved 2007-03-13.

- ^ "Bike Frame Geometry". Eagle One Research and Development. Archived from the original on 29 June 2012. Retrieved 18 June 2012.

- ^ https://www.youtube.com Carbon vs Aluminum Frames - Which is Stronger?

- ^ "Carbon Bicycle and Component Care". Archived from the original on February 5, 2013. Retrieved February 16, 2013. BicycleWarehouse.com

- ^ "Bike Framers". Spadout. Archived from the original on 5 July 2012. Retrieved 18 June 2012.

- ^ "Inside Calfee Design's Carbon Repair Service". Archived from the original on September 17, 2012. Retrieved February 16, 2013. Bicycling Magazine

- ^ "Kirk History". Archived from the original on 2008-08-23. Retrieved 2008-07-20.

- ^ "Paketa Custom Magnesium Bicycles :: Stronger Than Carbon Fiber and Aluminum". Archived from the original on 2012-10-30. Retrieved 2012-12-04.

- ^ "MOMBAT American Bicycles History". Retrieved 19 April 2013.

- ^ "American Bamboo Society Bambucicletas". August 2006. Archived from the original on 17 January 2007. Retrieved 2007-01-16.

- ^ "Calfee Design Bamboo Bike". 2005. Archived from the original on 13 January 2007. Retrieved 2007-01-16.

- ^ "Ottavia's Suitcase Magni Vinicio's Wooden Bicycles". Archived from the original on 6 February 2012. Retrieved 16 February 2013.

- ^ "Wooden Bicycles in East Africa". Retrieved 16 February 2013.

- ^ "The durable, $9 cardboard bike". 17 October 2012. Retrieved 16 February 2013.

- ^ "Lemond Spine Technology". Archived from the original on 2007-03-09. Retrieved 2007-03-14.

- ^ "Specialized Allez Technical Specifications". Archived from the original on 2007-10-19. Retrieved 2007-03-14.

- ^ Smart Cycling: Promoting Safety, Fun, Fitness, and the Environment. Human Kinetics. 2010. pp. 25–26. ISBN 978-0-7360-8717-9.

- ^ Brown, Sheldon. "Glossary: Brazon-on". Archived from the original on 29 January 2009. Retrieved 2009-02-13.

External links

[edit]- Science of Cycling: Frames & Materials from the Exploratorium

- Sheldon Brown's "Revisionist Theory of Bicycle Sizing" - an explanation of the different ways of measuring frame sizes.

- Frame Size Calculator - a simple frame size calculator tool

- Metallurgy for Cyclists - discusses frame material properties in relation to suitability to frame use

- BikeCAD program allows you to design your own frame online.

- Frame Sketcher Archived 2021-04-27 at the Wayback Machine is a simple HTML5 app which allows to sketch and compare frames online.