Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

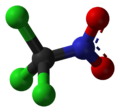

Chloropicrin

View on Wikipedia

| |||

| Names | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| IUPAC name

Trichloro(nitro)methane

| |||

Other names

| |||

| Identifiers | |||

3D model (JSmol)

|

|||

| 1756135 | |||

| ChEBI | |||

| ChEMBL | |||

| ChemSpider | |||

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.000.847 | ||

| EC Number |

| ||

| 240197 | |||

| KEGG | |||

PubChem CID

|

|||

| RTECS number |

| ||

| UNII | |||

| UN number | 1580 | ||

CompTox Dashboard (EPA)

|

|||

| |||

| |||

| Properties | |||

| CCl3NO2 | |||

| Molar mass | 164.375 g/mol | ||

| Appearance | colorless liquid | ||

| Odor | irritating[1] | ||

| Density | 1.692 g/ml | ||

| Melting point | −69 °C (−92 °F; 204 K) | ||

| Boiling point | 112 °C (234 °F; 385 K) (decomposes) | ||

| 0.2%[1] | |||

| Vapor pressure | 18 mmHg (20°C)[1] | ||

| −75.3·10−6 cm3/mol | |||

| Hazards | |||

| Occupational safety and health (OHS/OSH): | |||

Main hazards

|

Extremely toxic and irritating to skin, eyes, and lungs. | ||

| GHS labelling: | |||

| |||

| Danger | |||

| H301, H314, H330, H370, H372, H410 | |||

| P260, P264, P270, P271, P273, P280, P284, P301+P310, P301+P330+P331, P303+P361+P353, P304+P340, P305+P351+P338, P307+P311, P310, P314, P320, P321, P330, P363, P391, P403+P233, P405, P501 | |||

| NFPA 704 (fire diamond) | |||

| Lethal dose or concentration (LD, LC): | |||

LC50 (median concentration)

|

9.7 ppm (mouse, 4 hr) 117 ppm (rat, 20 min) 14.4 ppm (rat, 4 hr)[2] | ||

LCLo (lowest published)

|

293 ppm (human, 10 min) 340 ppm (mouse, 1 min) 117 ppm (cat, 20 min)[2] | ||

| NIOSH (US health exposure limits): | |||

PEL (Permissible)

|

TWA 0.1 ppm (0.7 mg/m3)[1] | ||

REL (Recommended)

|

TWA 0.1 ppm (0.7 mg/m3)[1] | ||

IDLH (Immediate danger)

|

2 ppm[1] | ||

Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa).

| |||

Chloropicrin, also known as PS (from Port Sunlight[3]) and nitrochloroform, is a chemical compound currently used as a broad-spectrum antimicrobial, fungicide, herbicide, insecticide, and nematicide.[4] It was used as a poison gas in World War I and the Russian military has been accused of using it in the Russo-Ukrainian War.[5][6][7] Its chemical structural formula is Cl3C−NO2.

Synthesis

[edit]Chloropicrin was discovered in 1848 by Scottish chemist John Stenhouse. He prepared it by the reaction of sodium hypochlorite with picric acid:

Because of the precursor used, Stenhouse named the compound chloropicrin, although the two compounds are structurally dissimilar.

Today, chloropicrin is manufactured by the reaction of nitromethane with sodium hypochlorite:[8]

Reaction of chloroform and nitric acid also yields chloropicrin:[9]

Properties

[edit]Chloropicrin's chemical formula is CCl3NO2 and its molecular weight is 164.38 grams/mole.[10] Pure chloropicrin is a colorless liquid, with a boiling point of 112 °C.[10] Chloropicrin is sparingly soluble in water with solubility of 2 g/L at 25 °C.[10] It is volatile, with a vapor pressure of 23.2 millimeters of mercury (mmHg) at 25 °C; the corresponding Henry's law constant is 0.00251 atmosphere-cubic meter per mole.[10] The octanol-water partition coefficient (Kow) of chloropicrin is estimated to be 269.[10] Its soil adsorption coefficient (Koc; normalized to soil organic matter content) is 25 cm3/g.[10]

Uses

[edit]Poison

[edit]Chloropicrin was manufactured for use as poison gas in World War I.[11] In World War I, German forces used concentrated chloropicrin against Allied forces as a tear gas. While not as lethal as other chemical weapons, it induced vomiting and forced Allied soldiers to remove their masks to vomit, exposing them to more toxic gases used as weapons during the war.[12] It was also used by the Imperial Russian Army in hand grenades as 50% solution in sulfuryl chloride.[13]

In February 2024, Ukrainian General Oleksandr Tarnavskyi accused the Russian Armed Forces of using chloropicrin munitions.[14] In May 2024, the United States Department of State also alleged use of chloropicrin by Russian forces in Ukraine, and imposed sanctions against Russian individuals and entities as a response.[15] Dutch and German intelligence agencies found chloropicrin use to be "commonplace" by July 2025.[16]

Agriculture

[edit]In agriculture, chloropicrin is injected into soil prior to planting a crop to fumigate soil. Chloropicrin affects a broad spectrum of fungi, microbes and insects.[17] It is commonly used as a stand-alone treatment or in combination / co-formulation with methyl bromide and 1,3-dichloropropene.[17][18] Chloropicrin is used as an indicator and repellent when fumigating residences for insects with sulfuryl fluoride which is an odorless gas.[citation needed] Chloropicrin's mode of action is unknown[19] (IRAC MoA 8B).[20] Chloropicrin may stimulate weed germination, which can be useful when quickly followed by a more effective herbicide.[21]

Chloropicrin was first registered in 1975 in the US. After a 2008 re-approval, the EPA[22] stated that chloropicrin "means more fresh fruits and vegetables can be cheaply produced domestically year-round because several severe pest problems can be efficiently controlled."[23][24] To ensure chloropicrin is used safely, the EPA requires a strict set of protections for handlers, workers, and persons living and working in and around farmland during treatments.[25][24] EPA protections were increased in both 2011 and 2012, reducing fumigant exposures and significantly improving safety.[26] Protections include the training of certified applicators supervising pesticide application, the use of buffer zones, posting before and during pesticide application, fumigant management plans, and compliance assistance and assurance measures.[citation needed]

Used as a preplant soil treatment measure, chloropicrin suppresses soilborne pathogenic fungi and some nematodes and insects. According to chloropicrin manufacturers, with a half-life of hours to days, it is completely digested by soil organisms before the crop is planted, making it safe and efficient.[citation needed] Contrary to popular belief, chloropicrin does not sterilize soil and does not deplete the ozone layer, as the compound is destroyed by sunlight. Additionally, chloropicrin has never been found in groundwater, due to its low solubility.[27]

California

[edit]In California, experience with acute effects of chloropicrin when used as a soil fumigant for strawberries and other crops led to the release of regulations in January 2015 creating buffer zones and other precautions to minimize exposure to farm workers, neighbors, and passersby.[28][29]

Safety

[edit]At a national level, chloropicrin is regulated in the United States by the United States Environmental Protection Agency as a restricted use pesticide.[30] Because of its toxicity, distribution and use of chloropicrin is available only to licensed professionals and specially certified growers who are trained in its proper and safe use.[30] In the US, occupational exposure limits have been set at 0.1 ppm over an eight-hour time-weighted average.[31]

High concentrations

[edit]

Chloropicrin is harmful to humans. It can be absorbed systemically through inhalation, ingestion, and the skin. At high concentrations, it is severely irritating to the lungs, eyes, and skin.[32]

Damage to protective gear

[edit]Chloropicrin and its derivative phosgene oxime have been known to damage or compromise earlier generations of personal protective equipment. Some of the soldiers attacked mentioned a white smoke emerging from their gas masks.[citation needed]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f NIOSH Pocket Guide to Chemical Hazards. "#0132". National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH).

- ^ a b "Chloropicrin". Immediately Dangerous to Life or Health Concentrations. National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health.

- ^ Foulkes, C. H. (31 January 2012). "GAS!" – The Story of the Special Brigade. Andrews UK Limited. p. 193.

- ^ "RED Fact Sheet: Chloropicrin" (PDF). US Environmental Protection Agency. 10 July 2008. p. 2. Archived from the original (PDF) on October 31, 2008. Retrieved 20 September 2013.

- ^ Office of the Spokesperson (1 May 2024). "Imposing New Measures on Russia for its Full-Scale War and Use of Chemical Weapons Against Ukraine". U.S. Department of State. Archived from the original on 23 May 2024. Retrieved 23 May 2024.

- ^ "A top Russian general is killed in a Moscow bombing claimed by Ukraine". Associated Press News. 2024-12-17. Retrieved 2024-12-18.

- ^ Quell, Molly (2025-07-04). "Dutch intelligence services say Russia has stepped up use of banned chemical weapons in Ukraine". Reuters. Retrieved 2025-07-05.

- ^ Markofsky, Sheldon B. (2005). "Nitro Compounds, Aliphatic". Ullmann's Encyclopedia of Industrial Chemistry. Weinheim: Wiley-VCH.

- ^ Jackson, Kirby E. (1934). "Chloropicrin". Chemical Reviews. 14 (2): 251–286. doi:10.1021/cr60048a003.

- ^ a b c d e f "Executive Summary - Evaluation of Chloropicrin As A Toxic Air Contaminant" (PDF). Department of Pesticide Regulation - California Environmental Protection Agency. February 2010. p. iv. Archived from the original (PDF) on 6 October 2013. Retrieved 20 September 2013.

- ^ Ayres, Leonard P. (1919). The War with Germany (2nd ed.). Washington, DC: United States Government Printing Office. p. 80.

- ^ Heller, Charles E. (September 1984). "Chemical Warfare in World War I: The American Experience, 1917–1918" (PDF). Leavenworth Papers (10): 23.

- ^ Sartori, Mario (1939). The War Gases. D. Van Nostrand. p. 165.

- ^ "Ukraine accuses Russia of intensifying chemical attacks on the battlefield". Reuters. 9 February 2024. Retrieved 2024-02-10.

- ^ "Imposing New Measures on Russia for its Full-Scale War and Use of Chemical Weapons Against Ukraine". United States Department of State. Retrieved 2 May 2024.

- ^ Quell, Molly (2025-07-04). "Dutch intelligence services say Russia has stepped up use of banned chemical weapons in Ukraine". Reuters. Retrieved 2025-07-05.

- ^ a b "Factsheet: Chloropicrin" (PDF). New South Wales: WorkCover. Archived from the original (PDF) on May 20, 2009.

- ^ Fries, Amos Alfred; West, Clarence Jay (1921). Chemical warfare. McGraw-Hill. p. 144.

- ^ Chloropicrin in the Pesticide Properties DataBase (PPDB), University of Hertfordshire, accessed 2021-03-10.

- ^ "IRAC Mode of Action Classification Scheme Version 9.4". IRAC (Insecticide Resistance Action Committee) (pdf). March 2020.

- ^ Martin, Frank N. (2003). "Development of Alternative Strategies for Management of Soilborne Pathogens Currently Controlled with Methyl Bromide". Annual Review of Phytopathology. 41 (1). Annual Reviews: 325–350. Bibcode:2003AnRvP..41..325M. doi:10.1146/annurev.phyto.41.052002.095514. ISSN 0066-4286. PMID 14527332.

- ^ "RED Fact Sheet: Chloropicrin". US Environmental Protection Agency. 10 July 2008. p. 2. Retrieved 20 September 2013.

- ^ "Amended Reregistration Eligibility Decision (RED) for Chloropicrin" (PDF). United States Environmental Protection Agency. May 2009. Archived from the original (PDF) on October 6, 2013. Retrieved 20 September 2013.

- ^ a b "Chloropicrin Mitigation Proposal" (PDF). Department of Pesticide Regulation – California Environmental Protection Agency. 15 May 2013. p. 2. Archived from the original (PDF) on 6 October 2013. Retrieved 20 September 2013.

- ^ "Chloropicrin – Background". Retrieved 20 September 2013.

- ^ "Chloropicrin Mitigation Proposal" (PDF). Department of Pesticide Regulation – California Environmental Protection Agency. 15 May 2013. p. 2. Archived from the original (PDF) on 6 October 2013. Retrieved 20 September 2013.

The Amended RED incorporated final new safety measures to increase protections for agricultural workers and bystanders. These measures establish a baseline for safe use of the soil fumigants throughout the United States, reducing fumigant exposures and significantly improving safety.

- ^ "Chloropicrin Soil Fumigation in Potato Production Systems". Plant Management Network. American Phytopathological Society. Retrieved 1 Apr 2019.

- ^ "Control Measures for Chloropicrin" (PDF). California Department of Pesticide Regulation. January 6, 2015. Archived from the original (PDF) on January 28, 2015. Retrieved January 15, 2015.

added controls for chloropicrin when it is used as a soil fumigant. The controls are intended to reduce risk from acute (short-term) exposures that might occur near fields fumigated with products containing chloropicrin.

- ^ "Chloropicrin Mitigation Proposal" (PDF). Department of Pesticide Regulation – California Environmental Protection Agency. 15 May 2013. p. 2. Archived from the original (PDF) on 6 October 2013. Retrieved 20 September 2013.

The new measures appearing on soil fumigant Phase 2 labels include buffer zones and posting, emergency preparedness and response measures, training for certified applicators supervising applications, Fumigant Management Plans, and notice to State Lead Agencies who wish to be informed of applications in their states.

- ^ a b "Chloropicrin Mitigation Proposal" (PDF). Department of Pesticide Regulation – California Environmental Protection Agency. 15 May 2013. p. 1. Archived from the original (PDF) on 6 October 2013. Retrieved 20 September 2013.

- ^ "NIOSH Pocket Guide to Chemical Hazards". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Retrieved 7 November 2013.

- ^ "Chloropicrin (PS): Lung Damaging Agent". Emergency Response Safety and Health Database. National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health. August 22, 2008. Retrieved December 23, 2008.

Chloropicrin

View on GrokipediaChloropicrin (CCl₃NO₂), also known as trichloronitromethane or by its military designation PS, is a synthetic organochlorine compound that serves primarily as a broad-spectrum soil fumigant in agriculture to suppress nematodes, fungi, insects, and weeds, while historically functioning as a chemical warfare agent valued for its severe irritant and lacrimatory properties.[1][2] The compound appears as a colorless to pale yellow oily liquid with a pungent, irritating odor reminiscent of tear gas, exhibiting low solubility in water but high volatility that enables deep soil penetration for pest control.[3][1] Noncombustible and denser than water, chloropicrin's vapors are highly toxic by inhalation, causing intense eye, nose, and throat irritation, pulmonary edema, and potential systemic effects through interference with oxygen transport in hemoglobin.[2][3] Introduced over a century ago, it gained notoriety during World War I when deployed by German forces as a choking and vomiting agent, though less lethal than other gases, its deployment highlighted the compound's capacity to incapacitate through respiratory and ocular distress.[1] In modern agriculture, chloropicrin remains a critical tool for pre-plant soil treatment in high-value crops like strawberries and peppers, enhancing yields by mitigating soil-borne pathogens despite ongoing debates over its environmental persistence and handler safety requirements.[4][5] Its dual legacy underscores a balance between efficacious pest management and inherent hazards, necessitating strict regulatory controls under frameworks like the UN Chemical Weapons Convention for non-prohibited applications.[1][6]

History

Early Discovery and Synthesis

Chloropicrin, chemically known as trichloronitromethane (CCl₃NO₂), was first synthesized in 1848 by Scottish chemist John Stenhouse through the reaction of picric acid (2,4,6-trinitrophenol) with bleaching powder or sodium hypochlorite, yielding the compound as a byproduct where nitro groups from picric acid were selectively incorporated.[4][7] This initial preparation highlighted its lachrymatory properties but did not immediately lead to practical applications.[4] Early synthesis methods remained small-scale and lab-oriented, relying on the Stenhouse process or variations involving the chlorination and nitration of simpler precursors like chloroform with concentrated nitric acid under controlled conditions to form the trichloronitromethane structure. These techniques produced limited quantities suitable for basic chemical characterization rather than bulk production. The compound's potential beyond mere curiosity emerged with its patenting in 1908 for insecticidal applications, marking the first formal recognition of its biocidal efficacy against pests. By 1916, testing revealed its potent fumigant qualities, capable of penetrating enclosed spaces and incapacitating through irritation, though initial focus remained on non-agricultural contexts.[8]Military Applications in World War I

Chloropicrin, designated as "PS" by Allied forces, served primarily as a harassing and incapacitating agent in chemical warfare during World War I, valued for its potent irritant properties that induced vomiting, severe lacrimation, and temporary blindness, often compelling soldiers to remove protective masks and exposing them to more lethal gases like phosgene.[2][1] German forces employed it in artillery shells mixed with phosgene to enhance penetration of early gas masks, which were ineffective against its lacrimatory effects; this combination first gained prominence during operations near Ypres on July 12, 1917, where it contributed to respiratory distress and secondary casualties from pulmonary edema rather than immediate lethality.[9] The agent's tactical deployment aimed at disrupting troop cohesion by causing mass incapacitation, with exposed individuals experiencing intense eye inflammation, coughing, nausea, and lung fluid accumulation, though direct fatalities from chloropicrin alone remained low, aligning with broader chemical warfare statistics where such agents accounted for under 1% of total deaths but inflicted disproportionate non-fatal injuries.[10] Allied powers, including Britain and later the United States, adopted chloropicrin for similar purposes, firing it in shells during key engagements such as the Battle of Messines in June 1917, where over 75,000 rounds were used to irritate and demoralize German positions.[11] Its efficacy stemmed from rapid onset of symptoms—lacrimation within seconds at concentrations as low as 0.3 ppm, escalating to vomiting and blindness at higher exposures—allowing it to bypass rudimentary filters made of cotton or charcoal, though improved masks later mitigated its impact.[2] Limitations included its volatility, which reduced persistence in open terrain, and reliance on delivery via shells or cylinders, making it vulnerable to wind shifts and counter-battery fire; nonetheless, it was produced in large quantities by all major combatants, with stockpiles supporting extensive use until the Armistice.[1] Historical records indicate chloropicrin's role amplified the psychological terror of gas attacks, as its odor—reminiscent of flypaper or pineapple—signaled impending exposure, but its primary value lay in non-lethal disruption, with casualties often requiring evacuation for treatment of edema and irritation rather than succumbing outright.[10] By 1918, integration into mixed-gas munitions had become standard, yet evolving protective equipment and the sheer scale of conventional artillery diminished its standalone decisiveness on the battlefield.[9]Transition to Agricultural Use

Following the end of World War I in 1918, chloropicrin transitioned from military use as a tear gas and toxicant to agricultural applications, driven by its demonstrated toxicity toward pests and surplus wartime production. In 1919, it was first employed for nematode control in soil, capitalizing on observations of its insecticidal and broad-spectrum biocidal effects from battlefield exposures.[12][13] By the early 1920s, U.S. and European agricultural trials tested chloropicrin as a pre-plant soil fumigant, confirming its efficacy against nematodes, soil-borne fungi, and insects such as wireworms, with applications injected into soil to achieve partial sterilization. These experiments, including those by Matthews in England, revealed beneficial impacts on crop health through pest suppression, outweighing handling challenges from its lacrimatory irritancy and supporting initial adoption despite the need for protective measures.[14][15] Expansion accelerated in the 1930s and 1940s amid increasing soil-borne disease pressures from intensive farming, with chloropicrin established as a versatile fumigant via refined injection techniques and early combination patents that broadened its spectrum against pathogens. Field data from this era underscored its role in enabling higher yields by mitigating yield-limiting pests, cementing pre-plant fumigation protocols in regions facing nematode and fungal outbreaks.[13][5]Chemical Properties

Physical Characteristics

Chloropicrin is a colorless to pale yellow oily liquid at room temperature, with a melting point of approximately -64 °C.[3][16] Its density is 1.692 g/cm³, making it denser than water.[17] The compound has a boiling point of 112 °C at standard pressure.[2] Chloropicrin exhibits high volatility, with a vapor pressure of 24 mm Hg at 25 °C.[18] It is sparingly soluble in water, at about 1.6 g/L at 25 °C, but miscible with many organic solvents, which affects its penetration in various media.[19] The substance emits a strong, pungent, irritating odor detectable at concentrations as low as 1 ppm, serving as an inherent warning property.[20][1]