Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Aperture

View on Wikipedia

In optics, the aperture of an optical system (including a system consisting of a single lens) is the hole or opening that primarily limits light propagated through the system. The aperture defines a bundle of rays from each point on an object that will come to a focus in the image plane.

An optical system typically has many structures that limit ray bundles (ray bundles are also known as pencils of light). These structures may be the edge of a lens or mirror, or a ring or other fixture that holds an optical element in place or may be a special element such as a diaphragm placed in the optical path to limit the light admitted by the system. These structures are called stops,[2] and the aperture stop is the stop that primarily determines the cone of rays that an optical system accepts (see entrance pupil). As a result, it also determines the ray cone angle and brightness at the image point (see exit pupil). Optical systems are typically designed for a particular stop to be the aperture stop, but it is possible for different stops to serve as the aperture stop for objects at different distances. Some rays from object points away from the optical axis may clip on surfaces other than the aperture stop. This is called vignetting.[3] The aperture stop is not necessarily the smallest stop in the system. Magnification and demagnification by lenses and other elements can cause a relatively large stop to be the aperture stop for the system.

In some contexts, especially in photography and astronomy, aperture refers to the opening diameter of the aperture stop through which light can pass. For example, in a telescope, the aperture stop is typically the edges of the objective lens or mirror (or of the mount that holds it). One then speaks of a telescope as having, for example, a 100-centimetre (39 in) aperture. In astrophotography, the aperture may be given as a linear measure (for example, in inches or millimetres) or as the dimensionless ratio between that measure and the focal length. In other photography, it is usually given as a ratio.

A usual expectation is that the term aperture refers to the opening of the aperture stop, but in reality, the term aperture and the aperture stop are mixed in use. Sometimes even stops that are not the aperture stop of an optical system are also called apertures. Contexts need to clarify these terms.

The word aperture is also used in other contexts to indicate a system which blocks off light outside a certain region. In astronomy, for example, a photometric aperture around a star usually corresponds to a circular window around the image of a star within which the light intensity is assumed.[4]

Application

[edit]

The aperture stop is an important element in most optical designs. Its most obvious feature is that it limits the amount of light that can reach the image/film plane. This can be either unavoidable due to the practical limit of the aperture stop size, or deliberate to prevent saturation of a detector or overexposure of film. In both cases, the size of the aperture stop determines the amount of light admitted by an optical system. The aperture stop also affects other optical system properties:

- The opening size of the stop is one factor that affects DOF (depth of field). A smaller stop (larger f number) produces a longer DOF because it only allows a smaller angle of the cone of light reaching the image plane so the spread of the image of an object point is reduced. A longer DOF allows objects at a wide range of distances from the viewer to all be in focus at the same time.

- The stop limits the effect of optical aberrations by limiting light such that the light does not reach edges of optics where aberrations are usually stronger than the optics centers. If the opening of the stop (called the aperture) is too large, then the image will be distorted by stronger aberrations. More sophisticated optical system designs can mitigate the effect of aberrations, allowing a larger aperture and therefore greater light collecting ability.

- The stop determines whether the image will be vignetted. Larger stops can cause the light intensity reaching the film or detector to fall off toward the edges of the picture, especially when, for off-axis points, a different stop becomes the aperture stop by virtue of cutting off more light than did the stop that was the aperture stop on the optic axis.

- The stop location determines the telecentricity. If the aperture stop of a lens is located at the front focal plane of the lens, then it becomes image-space telecentricity, i.e., the lateral size of the image is insensitive to the image plane location. If the stop is at the back focal plane of the lens, then it becomes object-space telecentricity where the image size is insensitive to the object plane location. The telecentricity helps precise two-dimensional measurements because measurement systems with the telecentricity are insensitive to axial position errors of samples or the sensor.

In addition to an aperture stop, a photographic lens may have one or more field stops, which limit the system's field of view. When the field of view is limited by a field stop in the lens (rather than at the film or sensor) vignetting results; this is only a problem if the resulting field of view is less than was desired.

In astronomy, the opening diameter of the aperture stop (called the aperture) is a critical parameter in the design of a telescope. Generally, one would want the aperture to be as large as possible, to collect the maximum amount of light from the distant objects being imaged. The size of the aperture is limited, however, in practice by considerations of its manufacturing cost and time and its weight, as well as prevention of aberrations (as mentioned above).

Apertures are also used in laser energy control, close aperture z-scan technique, diffractions/patterns, and beam cleaning.[5] Laser applications include spatial filters, Q-switching, high intensity x-ray control.

In light microscopy, the word aperture may be used with reference to either the condenser (that changes the angle of light onto the specimen field), field iris (that changes the area of illumination on specimens) or possibly objective lens (forms primary images). See Optical microscope.

In photography

[edit]The aperture stop of a photographic lens can be adjusted to control the amount of light reaching the film or image sensor. In combination with variation of shutter speed, the aperture size will regulate the film's or image sensor's degree of exposure to light. Typically, a fast shutter will require a larger aperture to ensure sufficient light exposure, and a slow shutter will require a smaller aperture to avoid excessive exposure.

A device called a diaphragm usually serves as the aperture stop and controls the aperture (the opening of the aperture stop). The diaphragm functions much like the iris of the eye – it controls the effective diameter of the lens opening (called pupil in the eyes). Reducing the aperture size (increasing the f-number) provides less light to sensor and also increases the depth of field (by limiting the angle of cone of image light reaching the sensor), which describes the extent to which subject matter lying closer than or farther from the actual plane of focus appears to be in focus. In general, the smaller the aperture (the larger the f-number), the greater the distance from the plane of focus the subject matter may be while still appearing in focus.

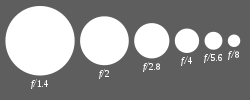

The lens aperture is usually specified as an f-number, the ratio of focal length to effective aperture diameter (the diameter of the entrance pupil). A lens typically has a set of marked "f-stops" that the f-number can be set to. A lower f-number denotes a greater aperture which allows more light to reach the film or image sensor. The photography term "one f-stop" refers to a factor of √2 (approx. 1.41) change in f-number which corresponds to a √2 change in aperture diameter, which in turn corresponds to a factor of 2 change in light intensity (by a factor 2 change in the aperture area).

Aperture priority is a semi-automatic shooting mode used in cameras. It permits the photographer to select an aperture setting and let the camera decide the shutter speed and sometimes also ISO sensitivity for the correct exposure. This is also referred to as Aperture Priority Auto Exposure, A mode, AV mode (aperture-value mode), or semi-auto mode.[6]

Typical ranges of apertures used in photography are about f/2.8 – f/22 or f/2 – f/16,[7] covering six stops, which may be divided into wide, middle, and narrow of two stops each, roughly (using round numbers) f/2 – f/4, f/4 – f/8, and f/8 – f/16 or (for a slower lens) f/2.8 – f/5.6, f/5.6 – f/11, and f/11 – f/22. These are not sharp divisions, and ranges for specific lenses vary.

Maximum and minimum apertures

[edit]The specifications for a given lens typically include the maximum and minimum aperture (opening) sizes, for example, f/0.95 – f/22. In this case, f/0.95 is currently the maximum aperture (the widest opening on a full-frame format for practical use[8]), and f/22 is the minimum aperture (the smallest opening). The maximum aperture tends to be of most interest and is always included when describing a lens. This value is also known as the lens "speed", as it affects the exposure time. As the aperture area is proportional to the light admitted by a lens or an optical system, the aperture diameter is proportional to the square root of the light admitted, and thus inversely proportional to the square root of required exposure time, such that an aperture of f/2 allows for exposure times one quarter that of f/4. (f/2 is 4 times larger than f/4 in the aperture area.)

Lenses with apertures opening f/2.8 or wider are referred to as "fast" lenses, although the specific point has changed over time (for example, in the early 20th century aperture openings wider than f/6 were considered fast.[9] The fastest lenses for the common 35 mm film format in general production have apertures of f/1.2 or f/1.4, with more at f/1.8 and f/2.0, and many at f/2.8 or slower; f/1.0 is unusual, though sees some use. When comparing "fast" lenses, the image format used must be considered. Lenses designed for a small format such as half frame or APS-C need to project a much smaller image circle than a lens used for large format photography. Thus the optical elements built into the lens can be far smaller and cheaper.

In exceptional circumstances lenses can have even wider apertures with f-numbers smaller than 1.0; see lens speed: fast lenses for a detailed list. For instance, both the current Leica Noctilux-M 50mm ASPH and a 1960s-era Canon 50mm rangefinder lens have a maximum aperture of f/0.95.[10] Cheaper alternatives began appearing in the early 2010s, such as the Cosina Voigtländer f/0.95 Nokton (several in the 10.5–60 mm range) and f/0.8 (29 mm) Super Nokton manual focus lenses in the Micro Four-Thirds System,[11] and the Venus Optics (Laowa) Argus 35 mm f/0.95.[8]

Professional lenses for some movie cameras have f-numbers as small as f/0.75. Stanley Kubrick's film Barry Lyndon has scenes shot by candlelight with a NASA/Zeiss 50mm f/0.7,[12] the fastest lens in film history. Beyond the expense, these lenses have limited application due to the correspondingly shallower depth of field (DOF) – the scene must either be shallow, shot from a distance, or will be significantly defocused, though this may be the desired effect.

Zoom lenses typically have a maximum relative aperture (minimum f-number) of f/2.8 to f/6.3 through their range. High-end lenses will have a constant aperture, such as f/2.8 or f/4, which means that the relative aperture will stay the same throughout the zoom range. A more typical consumer zoom will have a variable maximum relative aperture since it is harder and more expensive to keep the maximum relative aperture proportional to the focal length at long focal lengths; f/3.5 to f/5.6 is an example of a common variable aperture range in a consumer zoom lens.

By contrast, the minimum aperture does not depend on the focal length – it is limited by how narrowly the aperture closes, not the lens design – and is instead generally chosen based on practicality: very small apertures have lower sharpness due to diffraction at aperture edges, while the added depth of field is not generally useful, and thus there is generally little benefit in using such apertures. Accordingly, DSLR lens typically have minimum aperture of f/16, f/22, or f/32, while large format may go down to f/64, as reflected in the name of Group f/64. Depth of field is a significant concern in macro photography, however, and there one sees smaller apertures. For example, the Canon MP-E 65mm can have effective aperture (due to magnification) as small as f/96. The pinhole optic for Lensbaby creative lenses has an aperture of just f/177.[13]

-

f/32 – small aperture and slow shutter

-

f/5.6 – large aperture and fast shutter

-

f/22 – small aperture and slower shutter (Exposure time: 1/80)

-

f/3.5 – large aperture and faster shutter (Exposure time: 1/2500)

-

Changing a camera's aperture value in half-stops, beginning with f/256 and ending with f/1

-

Changing a camera's aperture diameter from zero to infinity

Aperture area

[edit]The amount of light captured by an optical system is proportional to the area of the entrance pupil that is the object space-side image of the aperture of the system, equal to:

Where the two equivalent forms are related via the f-number N = f / D, with focal length f and entrance pupil diameter D.

The focal length value is not required when comparing two lenses of the same focal length; a value of 1 can be used instead, and the other factors can be dropped as well, leaving area proportion to the reciprocal square of the f-number N.

If two cameras of different format sizes and focal lengths have the same angle of view, and the same aperture area, they gather the same amount of light from the scene. In that case, the relative focal-plane illuminance, however, would depend only on the f-number N, so it is less in the camera with the larger format, longer focal length, and higher f-number. This assumes both lenses have identical transmissivity.

Aperture control

[edit]

Though as early as 1933 Torkel Korling had invented and patented for the Graflex large format reflex camera an automatic aperture control,[14] not all early 35mm single lens reflex cameras had the feature. With a small aperture, this darkened the viewfinder, making viewing, focusing, and composition difficult.[15] Korling's design enabled full-aperture viewing for accurate focus, closing to the pre-selected aperture opening when the shutter was fired and simultaneously synchronising the firing of a flash unit. From 1956 SLR camera manufacturers separately developed automatic aperture control (the Miranda T 'Pressure Automatic Diaphragm', and other solutions on the Exakta Varex IIa and Praktica FX2) allowing viewing at the lens's maximum aperture, stopping the lens down to the working aperture at the moment of exposure, and returning the lens to maximum aperture afterward.[16] The first SLR cameras with internal ("through-the-lens" or "TTL") meters (e.g., the Pentax Spotmatic) required that the lens be stopped down to the working aperture when taking a meter reading. Subsequent models soon incorporated mechanical coupling between the lens and the camera body, indicating the working aperture to the camera for exposure while allowing the lens to be at its maximum aperture for composition and focusing;[16] this feature became known as open-aperture metering.

For some lenses, including a few long telephotos, lenses mounted on bellows, and perspective-control and tilt/shift lenses, the mechanical linkage was impractical,[16] and automatic aperture control was not provided. Many such lenses incorporated a feature known as a "preset" aperture,[16][17] which allows the lens to be set to working aperture and then quickly switched between working aperture and full aperture without looking at the aperture control. A typical operation might be to establish rough composition, set the working aperture for metering, return to full aperture for a final check of focus and composition, and focusing, and finally, return to working aperture just before exposure. Although slightly easier than stopped-down metering, operation is less convenient than automatic operation. Preset aperture controls have taken several forms; the most common has been the use of essentially two lens aperture rings, with one ring setting the aperture and the other serving as a limit stop when switching to working aperture. Examples of lenses with this type of preset aperture control are the Nikon PC Nikkor 28 mm f/3.5 and the SMC Pentax Shift 6×7 75 mm f/4.5. The Nikon PC Micro-Nikkor 85 mm f/2.8D lens incorporates a mechanical pushbutton that sets working aperture when pressed and restores full aperture when pressed a second time.

Canon EF lenses, introduced in 1987,[18] have electromagnetic diaphragms,[19] eliminating the need for a mechanical linkage between the camera and the lens, and allowing automatic aperture control with the Canon TS-E tilt/shift lenses. Nikon PC-E perspective-control lenses,[20] introduced in 2008, also have electromagnetic diaphragms,[21] a feature extended to their E-type range in 2013.

Optimal aperture

[edit]Optimal aperture depends both on optics (the depth of the scene versus diffraction), and on the performance of the lens.

Optically, as a lens is stopped down, the defocus blur at the Depth of Field (DOF) limits decreases but diffraction blur increases. The presence of these two opposing factors implies a point at which the combined blur spot is minimized (Gibson 1975, 64); at that point, the f-number is optimal for image sharpness, for this given depth of field[22] – a wider aperture (lower f-number) causes more defocus, while a narrower aperture (higher f-number) causes more diffraction.

As a matter of performance, lenses often do not perform optimally when fully opened, and thus generally have better sharpness when stopped down some – this is sharpness in the plane of critical focus, setting aside issues of depth of field. Beyond a certain point, there is no further sharpness benefit to stopping down, and the diffraction occurred at the edges of the aperture begins to become significant for imaging quality. There is accordingly a sweet spot, generally in the f/4 – f/8 range, depending on lens, where sharpness is optimal, though some lenses are designed to perform optimally when wide open. How significant this varies between lenses, and opinions differ on how much practical impact this has.

While optimal aperture can be determined mechanically, how much sharpness is required depends on how the image will be used – if the final image is viewed under normal conditions (e.g., an 8″×10″ image viewed at 10″), it may suffice to determine the f-number using criteria for minimum required sharpness, and there may be no practical benefit from further reducing the size of the blur spot. But this may not be true if the final image is viewed under more demanding conditions, e.g., a very large final image viewed at normal distance, or a portion of an image enlarged to normal size (Hansma 1996). Hansma also suggests that the final-image size may not be known when a photograph is taken, and obtaining the maximum practicable sharpness allows the decision to make a large final image to be made at a later time; see also critical sharpness.

In biology

[edit]

In many living optical systems, the eye consists of an iris which adjusts the size of the pupil, through which light enters. The iris is analogous to the diaphragm, and the pupil (which is the adjustable opening in the iris) the aperture. Refraction in the cornea causes the effective aperture (the entrance pupil in optics parlance) to differ slightly from the physical pupil diameter. The entrance pupil is typically about 4 mm in diameter, although it can range from as narrow as 2 mm (f/8.3) in diameter in a brightly lit place to 8 mm (f/2.1) in the dark as part of adaptation. In rare cases, some individuals are able to dilate their pupils even beyond 8 mm (in scotopic lighting, close to the physical limit of the iris. In humans, the average iris diameter is about 11.5 mm,[23] which naturally influences the maximal size of the pupil as well, where larger iris diameters would typically have pupils which are able to dilate to a wider extreme than those with smaller irises. Maximum dilated pupil size also decreases with age.

The iris controls the size of the pupil via two complementary sets muscles, the sphincter and dilator muscles, which are innervated by the parasympathetic and sympathetic nervous systems respectively, and act to induce pupillary constriction and dilation respectively. The state of the pupil is closely influenced by various factors, primarily light (or absence of light), but also by emotional state, interest in the subject of attention, arousal, sexual stimulation,[24] physical activity,[25] accommodation state,[26] and cognitive load.[27] The field of view is not affected by the size of the pupil.

Some individuals are also able to directly exert manual and conscious control over their iris muscles and hence are able to voluntarily constrict and dilate their pupils on command.[28] However, this ability is rare and potential use or advantages are unclear.

Equivalent aperture range

[edit]In digital photography, the 35mm-equivalent aperture range is sometimes considered to be more important than the actual f-number. Equivalent aperture is the f-number adjusted to correspond to the f-number of the same size absolute aperture diameter on a lens with a 35mm equivalent focal length. Smaller equivalent f-numbers are expected to lead to higher image quality based on more total light from the subject, as well as lead to reduced depth of field. For example, a Sony Cyber-shot DSC-RX10 uses a 1" sensor, 24 – 200 mm with maximum aperture constant along the zoom range; f/2.8 has equivalent aperture range f/7.6, which is a lower equivalent f-number than some other f/2.8 cameras with smaller sensors.[29]

However, modern optical research concludes that sensor size does not actually play a part in the depth of field in an image.[30] An aperture's f-number is not modified by the camera's sensor size because it is a ratio that only pertains to the attributes of the lens. Instead, the higher crop factor that comes as a result of a smaller sensor size means that, in order to get an equal framing of the subject, the photo must be taken from further away, which results in a less blurry background, changing the perceived depth of field. Similarly, a smaller sensor size with an equivalent aperture will result in a darker image because of the pixel density of smaller sensors with equivalent megapixels. Every photosite on a camera's sensor requires a certain amount of surface area that is not sensitive to light, a factor that results in differences in pixel pitch and changes in the signal-noise ratio. However, neither the changed depth of field,[31] nor the perceived change in light sensitivity [32] are a result of the aperture. Instead, equivalent aperture can be seen as a rule of thumb to judge how changes in sensor size might affect an image, even if qualities like pixel density and distance from the subject are the actual causes of changes in the image.

In scanning or sampling

[edit]The terms scanning aperture and sampling aperture are often used to refer to the opening through which an image is sampled, or scanned, for example in a Drum scanner, an image sensor, or a television pickup apparatus. The sampling aperture can be a literal optical aperture, that is, a small opening in space, or it can be a time-domain aperture for sampling a signal waveform.

For example, film grain is quantified as graininess via a measurement of film density fluctuations as seen through a 0.048 mm sampling aperture.

In popular culture

[edit]

Aperture Science, a fictional company in the Portal fictional universe, is named after the optical system. The company's logo heavily features an aperture in its logo, and has come to symbolize the series, fictional company, and the Aperture Science Laboratories Computer-Aided Enrichment Center that the game series takes place in.[33]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Thomas Blount, Glossographia Anglicana Nova: Or, A Dictionary, Interpreting Such Hard Words of whatever Language, as are at present used in the English Tongue, with their Etymologies, Definitions, &c. Also, The Terms of Divinity, Law, Physick, Mathematics, History, Agriculture, Logick, Metaphysicks, Grammar, Poetry, Musick, Heraldry, Architecture, Painting, War, and all other Arts and Sciences are herein explain'd, from the best Modern Authors, as, Sir Isaac Newton, Dr. Harris, Dr. Gregory, Mr. Lock, Mr. Evelyn, Mr. Dryden, Mr. Blunt, &c., London, 1707.

- ^ "Exposure Stops in Photography - A Beginner's Guide". Photography Life. 16 January 2015. Retrieved 10 May 2019.

- ^ Hecht, Eugene (2017). "5.3.2 Entrance and Exit Pupils". Optics (5th ed.). Pearson. ISBN 978-1-292-09693-3.

- ^ Nicholas Eaton, Peter W. Draper & Alasdair Allan, Techniques of aperture photometry Archived 11 March 2007 at the Wayback Machine in PHOTOM – A Photometry Package, 20 August 2002

- ^ Rashidian Vaziri, M R (2015). "Role of the aperture in Z-scan experiments: A parametric study". Chinese Physics B. 24 (11) 114206. Bibcode:2015ChPhB..24k4206R. doi:10.1088/1674-1056/24/11/114206. S2CID 250753283.

- ^ "Aperture and shutter speed in digital cameras". elite-cameras.com. Archived from the original on 20 June 2006. Retrieved 20 June 2006. (original link no longer works, but page was saved by archive.org)

- ^ "What is... Aperture?". Archived from the original on 10 October 2014. Retrieved 13 June 2010.

- ^ a b wayne (3 May 2021). "Argus -Laowa f/0.95 Large Aperture Lenses - Ultra-fast lens". Retrieved 6 September 2021.

- ^ "Basics of Photography: A Beginner's Guide". 31 August 2021.

- ^ Mahoney, John (10 September 2008). "Leica's $11,000 Noctilux 50mm f/0.95 Lens Is a Nightvision Owl Eye For Your Camera". gizmodo.com. Retrieved 15 April 2018.

- ^ "Micro Four Thirds Mount Lenses". Cosina Voigtlander. 19 September 2021. Archived from the original on 21 May 2022. Retrieved 15 September 2023.

- ^ Lightman, Herb A.; DiGiulio, Ed (16 March 2018) [March 1976]. "Photographing Kubrick's 'Barry Lyndon'". American Cinematographer. Archived from the original on 7 February 2023. Retrieved 15 September 2023.

- ^ "Pinhole and Zone Plate Photography for SLR Cameras". Lensbaby Pinhole optic. Archived from the original on 1 May 2011.

- ^ "US patent 2,029,238 Camera Mechanism, Application June 4, 1933" (PDF).

- ^ Shipman, Carl (1977). SLR Photographers Handbook. Tucson, AZ: HP Books. pp. 53. ISBN 0-912656-59-X.

- ^ a b c d Sidney F. Ray. The geometry of image formation. In The Manual of Photography: Photographic and Digital Imaging, 9th ed, pp. 136–137. Ed. Ralph E. Jacobson, Sidney F. Ray, Geoffrey G. Atteridge, and Norman R. Axford. Oxford: Focal Press, 2000. ISBN 0-240-51574-9

- ^ B. "Moose" Peterson. Nikon System Handbook. New York: Images Press, 1997, pp. 42–43. ISBN 0-929667-03-4

- ^ Canon Camera Museum. Accessed 12 December 2008.

- ^ EF Lens Work III: The Eyes of EOS. Tokyo: Canon Inc., 2003, pp. 190–191.

- ^ Nikon USA web site Archived 12 December 2008 at the Wayback Machine. Accessed 12 December 2008.

- ^ Nikon PC-E product comparison brochure Archived 17 December 2008 at the Wayback Machine. Accessed 12 December 2008.

- ^ "Diffraction and Optimum Aperture – Format size and diffraction limitations on sharpness". www.bobatkins.com. Retrieved 15 April 2018.

- ^ Rüfer, Florian; Schröder, Anke; Erb, Carl (April 2005). "White-to-white corneal diameter: normal values in healthy humans obtained with the Orbscan II topography system". Cornea. 24 (3): 259–261. doi:10.1097/01.ico.0000148312.01805.53. ISSN 0277-3740. PMID 15778595.

- ^ Hess EH, Polt JM (August 1960). "Pupil size as related to interest value of visual stimuli". Science. 132 (3423): 349–50. Bibcode:1960Sci...132..349H. doi:10.1126/science.132.3423.349. PMID 14401489. S2CID 12857616.

- ^ Kuwamizu, Ryuta; Yamazaki, Yudai; Aoike, Naoki; Ochi, Genta; Suwabe, Kazuya; Soya, Hideaki (24 September 2022). "Pupil-linked arousal with very light exercise: pattern of pupil dilation during graded exercise". The Journal of Physiological Sciences. 72 (1): 23. doi:10.1186/s12576-022-00849-x. ISSN 1880-6562. PMC 10717467. PMID 36153491.

- ^ Dragoi, Valentin. "Chapter 7: Ocular Motor System". Neuroscience Online: An Electronic Textbook for the Neurosciences. Department of Neurobiology and Anatomy, The University of Texas Medical School at Houston. Archived from the original on 2 November 2012. Retrieved 24 October 2012.

- ^ Kahneman D, Beatty J (December 1966). "Pupil diameter and load on memory". Science. 154 (3756): 1583–5. Bibcode:1966Sci...154.1583K. doi:10.1126/science.154.3756.1583. PMID 5924930. S2CID 22762466.

- ^ Eberhardt, Lisa V.; Grön, Georg; Ulrich, Martin; Huckauf, Anke; Strauch, Christoph (1 October 2021). "Direct voluntary control of pupil constriction and dilation: Exploratory evidence from pupillometry, optometry, skin conductance, perception, and functional MRI". International Journal of Psychophysiology. 168: 33–42. doi:10.1016/j.ijpsycho.2021.08.001. ISSN 0167-8760. PMID 34391820.

- ^ R Butler. "Sony Cyber-shot DSC RX10 First Impressions Review". Retrieved 19 January 2014.

- ^ Nando Harmsen (8 December 2018). "Understanding How Sensor Size Affects Depth of Field". Retrieved 1 August 2023.

- ^ Todd Vorenkamp. "Depth of Field: The Myths". Retrieved 1 August 2023.

- ^ "Camera Sensor Size in Photography". 20 November 2020. Retrieved 1 August 2023.

- ^ VanBurkleo, Meagan (March 24, 2010). "Aperture Science: A History". Game Informer. Archived from the original on March 27, 2010. Retrieved March 24, 2010.

- Gibson, H. Lou. 1975. Close-Up Photography and Photomacrography. 2nd combined ed. Kodak Publication No. N-16. Rochester, NY: Eastman Kodak Company, Vol II: Photomacrography. ISBN 0-87985-160-0

- Hansma, Paul K. 1996. View Camera Focusing in Practice. Photo Techniques, March/April 1996, 54–57. Available as GIF images on the Large Format page.