Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Cyclic compound

View on WikipediaA cyclic compound (or ring compound) is a term for a compound in the field of chemistry in which one or more series of atoms in the compound is connected to form a ring. Rings may vary in size from three to many atoms, and include examples where all the atoms are carbon (i.e., are carbocycles), none of the atoms are carbon (inorganic cyclic compounds), or where both carbon and non-carbon atoms are present (heterocyclic compounds with rings containing both carbon and non-carbon). Depending on the ring size, the bond order of the individual links between ring atoms, and their arrangements within the rings, carbocyclic and heterocyclic compounds may be aromatic or non-aromatic; in the latter case, they may vary from being fully saturated to having varying numbers of multiple bonds between the ring atoms. Because of the tremendous diversity allowed, in combination, by the valences of common atoms and their ability to form rings, the number of possible cyclic structures, even of small size (e.g., < 17 total atoms) numbers in the many billions.

- Cyclic compound examples: All-carbon (carbocyclic) and more complex natural cyclic compounds

-

Cycloalkanes, the simplest carbocycles, including cyclopropane, cyclobutane, cyclopentane, and cyclohexane. Note, elsewhere an organic chemistry shorthand is used where hydrogen atoms are inferred as present to fill the carbon's valence of 4 (rather than their being shown explicitly).

-

Ingenol, a complex, terpenoid natural product, related to but simpler than the paclitaxel that follows, which displays a complex ring structure including 3-, 5-, and 7-membered non-aromatic, carbocyclic rings.

-

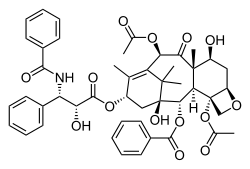

Paclitaxel, another complex, plant-derived terpenoid, also a natural product, displaying a complex multi-ring structure including 4-, 6-, and 8-membered rings (carbocyclic and heterocyclic, aromatic and non-aromatic).

Adding to their complexity and number, closing of atoms into rings may lock particular atoms with distinct substitution (by functional groups) such that stereochemistry and chirality of the compound results, including some manifestations that are unique to rings (e.g., configurational isomers). As well, depending on ring size, the three-dimensional shapes of particular cyclic structures – typically rings of five atoms and larger – can vary and interconvert such that conformational isomerism is displayed. Indeed, the development of this important chemical concept arose historically in reference to cyclic compounds. Finally, cyclic compounds, because of the unique shapes, reactivities, properties, and bioactivities that they engender, are the majority of all molecules involved in the biochemistry, structure, and function of living organisms, and in man-made molecules such as drugs, pesticides, etc.

Structure and classification

[edit]A cyclic compound or ring compound is a compound in which at least some its atoms are connected to form a ring.[1] Rings vary in size from three to many tens or even hundreds of atoms. Examples of ring compounds readily include cases where:

- all the atoms are carbon (i.e., are carbocycles),

- none of the atoms are carbon (inorganic cyclic compounds),[2] or where

- both carbon and non-carbon atoms are present (heterocyclic compounds with rings containing both carbon and non-carbon).

Common atoms can (as a result of their valences) form varying numbers of bonds, and many common atoms readily form rings. In addition, depending on the ring size, the bond order of the individual links between ring atoms, and their arrangements within the rings, cyclic compounds may be aromatic or non-aromatic; in the case of non-aromatic cyclic compounds, they may vary from being fully saturated to having varying numbers of multiple bonds. As a consequence of the constitutional variability that is thermodynamically possible in cyclic structures, the number of possible cyclic structures, even of small size (e.g., <17 atoms) numbers in the many billions.[3]

Moreover, the closing of atoms into rings may lock particular functional group–substituted atoms into place, resulting in stereochemistry and chirality being associated with the compound, including some manifestations that are unique to rings (e.g., configurational isomers);[4] As well, depending on ring size, the three-dimensional shapes of particular cyclic structures — typically rings of five atoms and larger — can vary and interconvert such that conformational isomerism is displayed.[4]

Carbocycles

[edit]The vast majority of cyclic compounds are organic, and of these, a significant and conceptually important portion are composed of rings made only of carbon atoms (i.e., they are carbocycles).[citation needed]

Inorganic cyclic compounds

[edit]Inorganic atoms form cyclic compounds as well. Examples include sulfur (e.g., cyclooctasulfur S8), sulfur and nitrogen (e.g., trithiazyl trichloride (NSCl)3), silicon (e.g., cyclopentasilane (SiH2)5), silicon and oxygen (e.g., hexamethylcyclotrisiloxane [(CH3)2SiO]3), phosphorus and nitrogen (e.g., hexachlorophosphazene (NPCl2)3), phosphorus and oxygen (e.g., sodium metaphosphate Na3(PO2)3), boron and oxygen (e.g., sodium metaborate Na3(BO2)3), boron and nitrogen (e.g., borazine (BN)3H6), nitrogen (e.g., pentazole N5H).[citation needed] When carbon in benzene is "replaced" by other elements, e.g., as in borabenzene, silabenzene, germanabenzene, stannabenzene, and phosphorine, aromaticity is retained, and so aromatic inorganic cyclic compounds are also known and well-characterized.[citation needed]

Heterocyclic compounds

[edit]A heterocyclic compound is a cyclic compound that has atoms of at least two different elements as members of its ring(s).[5] Cyclic compounds that have both carbon and non-carbon atoms present are heterocyclic carbon compounds, and the name refers to inorganic cyclic compounds as well (e.g., siloxanes, which contain only silicon and oxygen in the rings, and borazines, which contain only boron and nitrogen in the rings).[5] Hantzsch–Widman nomenclature is recommended by the IUPAC for naming heterocycles, but many common names remain in regular use.[citation needed]

Macrocycles

[edit] The term macrocycle is used for compounds having a rings of 8 or more atoms.[6][7] Macrocycles may be fully carbocyclic (rings containing only carbon atoms, e.g. cyclooctane), heterocyclic containing both carbon and non-carbon atoms (e.g. lactones and lactams containing rings of 8 or more atoms), or non-carbon (containing only non-carbon atoms in the rings, e.g. borazine). Heterocycles with carbon in the rings may have limited non-carbon atoms in their rings (e.g., in lactones and lactams whose rings are rich in carbon but have limited number of non-carbon atoms), or be rich in non-carbon atoms and displaying significant symmetry (e.g., in the case of chelating macrocycles). Macrocycles can access a number of stable conformations, with preference to reside in conformations that minimize transannular nonbonded interactions within the ring (e.g., with the chair and chair-boat being more stable than the boat-boat conformation for cyclooctane, because of the interactions depicted by the arcs shown).[citation needed] Medium rings (8-11 atoms) are the most strained, with between 9-13 (kcal/mol) strain energy, and analysis of factors important in the conformations of larger macrocycles can be modeled using medium ring conformations.[8] Conformational analysis of odd-membered rings suggests they tend to reside in less symmetrical forms with smaller energy differences between stable conformations.[9]

The term macrocycle is used for compounds having a rings of 8 or more atoms.[6][7] Macrocycles may be fully carbocyclic (rings containing only carbon atoms, e.g. cyclooctane), heterocyclic containing both carbon and non-carbon atoms (e.g. lactones and lactams containing rings of 8 or more atoms), or non-carbon (containing only non-carbon atoms in the rings, e.g. borazine). Heterocycles with carbon in the rings may have limited non-carbon atoms in their rings (e.g., in lactones and lactams whose rings are rich in carbon but have limited number of non-carbon atoms), or be rich in non-carbon atoms and displaying significant symmetry (e.g., in the case of chelating macrocycles). Macrocycles can access a number of stable conformations, with preference to reside in conformations that minimize transannular nonbonded interactions within the ring (e.g., with the chair and chair-boat being more stable than the boat-boat conformation for cyclooctane, because of the interactions depicted by the arcs shown).[citation needed] Medium rings (8-11 atoms) are the most strained, with between 9-13 (kcal/mol) strain energy, and analysis of factors important in the conformations of larger macrocycles can be modeled using medium ring conformations.[8] Conformational analysis of odd-membered rings suggests they tend to reside in less symmetrical forms with smaller energy differences between stable conformations.[9]

Nomenclature

[edit]IUPAC nomenclature has extensive rules to cover the naming of cyclic structures, both as core structures, and as substituents appended to alicyclic structures.[citation needed] The term macrocycle is used when a ring-containing compound has a ring of 12 or more atoms.[6][7] The term polycyclic is used when more than one ring appears in a single molecule. Naphthalene is formally a polycyclic compound, but is more specifically named as a bicyclic compound. Several examples of macrocyclic and polycyclic structures are given in the final gallery below.

The atoms that are part of the ring structure are called annular atoms.[10]

Isomerism

[edit]Stereochemistry

[edit]The closing of atoms into rings may lock particular atoms with distinct substitution by functional groups such that the result is stereochemistry and chirality of the compound, including some manifestations that are unique to rings (e.g., configurational isomers).[4]

Conformational isomerism

[edit]Depending on ring size, the three-dimensional shapes of particular cyclic structures—typically rings of 5-atoms and larger—can vary and interconvert such that conformational isomerism is displayed.[4] Indeed, the development of this important chemical concept arose, historically, in reference to cyclic compounds. For instance, cyclohexanes—six membered carbocycles with no double bonds, to which various substituents might be attached, see image—display an equilibrium between two conformations, the chair and the boat, as shown in the image.

The chair conformation is the favored configuration, because in this conformation, the steric strain, eclipsing strain, and angle strain that are otherwise possible are minimized.[4] Which of the possible chair conformations predominate in cyclohexanes bearing one or more substituents depends on the substituents, and where they are located on the ring; generally, "bulky" substituents—those groups with large volumes, or groups that are otherwise repulsive in their interactions[citation needed]—prefer to occupy an equatorial location.[4] An example of interactions within a molecule that would lead to steric strain, leading to a shift in equilibrium from boat to chair, is the interaction between the two methyl groups in cis-1,4-dimethylcyclohexane. In this molecule, the two methyl groups are in opposing positions of the ring (1,4-), and their cis stereochemistry projects both of these groups toward the same side of the ring. Hence, if forced into the higher energy boat form, these methyl groups are in steric contact, repel one another, and drive the equilibrium toward the chair conformation.[4]

Principal uses

[edit]Because of the unique shapes, reactivities, properties, and bioactivities that they engender, cyclic compounds are the largest majority of all molecules involved in the biochemistry, structure, and function of living organisms, and in the man-made molecules (e.g., drugs, herbicides, etc.) through which man attempts to exert control over nature and biological systems.

Synthetic reactions

[edit]Important general reactions for forming rings

[edit]

There are a variety of specialized reactions whose use is solely the formation of rings, and these will be discussed below. In addition to those, there are a wide variety of general organic reactions that historically have been crucial in the development, first, of understanding the concepts of ring chemistry, and second, of reliable procedures for preparing ring structures in high yield, and with defined orientation of ring substituents (i.e., defined stereochemistry). These general reactions include:

- Acyloin condensation;

- Anodic oxidations; and

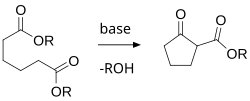

- the Dieckmann condensation as applied to ring formation.

Ring-closing reactions

[edit]In organic chemistry, a variety of synthetic procedures are particularly useful in closing carbocyclic and other rings; these are termed ring-closing reactions. Examples include:

- alkyne trimerisation;

- the Bergman cyclization of an enediyne;

- the Diels–Alder, between a conjugated diene and a substituted alkene, and other cycloaddition reactions;

- the Nazarov cyclization reaction, originally being the cyclization of a divinyl ketone;

- various radical cyclizations;

- ring-closing metathesis reactions, which also can be used to accomplish a specific type of polymerization;

- the Ruzicka large ring synthesis, in which two carboxyl groups combine to form a carbonyl group with loss of CO2 and H2O;

- the Wenker synthesis converting a beta amino alcohol to an aziridine

Ring-opening reactions

[edit]A variety of further synthetic procedures are particularly useful in opening carbocyclic and other rings, generally which contain a double bond or other functional group "handle" to facilitate chemistry; these are termed ring-opening reactions. Examples include:

- ring opening metathesis, which can also be used to accomplish a specific type of polymerization.

Ring expansion and ring contraction reactions

[edit]Ring expansion and contraction reactions are common in organic synthesis, and are frequently encountered in pericyclic reactions. Ring expansions and contractions can involve the insertion of a functional group such as the case with Baeyer–Villiger oxidation of cyclic ketones, rearrangements of cyclic carbocycles as seen in intramolecular Diels-Alder reactions, or collapse or rearrangement of bicyclic compounds as several examples.

Examples

[edit]Simple, mono-cyclic examples

[edit]The following are examples of simple and aromatic carbocycles, inorganic cyclic compounds, and heterocycles:

- Simple mono-cyclic compounds: Carbocyclic, inorganic, and heterocyclic (aromatic and non-aromatic) examples.

-

Benzene, a 6-membered carbocyclic organic compound, methine hydrogens shown, and 6 electrons shown as delocalized through drawing of circle (aromatic).

-

Cyclooctane, an 8-membered carbocyclic organic compound, methylene hydrogens implied, not shown (non-aromatic).

-

Cyclooctasulfur, an 8-membered inorganic cyclic compound (non-aromatic).

-

Trithiazyl trichloride, a 6-membered inorganic heterocyclic compound (non-aromatic).

-

Cyclopentasilane, a 5-membered inorganic cyclic compound (non-aromatic).

-

Hexamethylcyclotrisiloxane, a 6-membered organic heterocyclic compound (non-aromatic).

-

Hexachlorophosphazene, a 6-membered inorganic heterocyclic compound (aromatic).

-

Borazine, a 6-membered inorganic heterocyclic compound (may be aromatic).

-

Pentazole, a 5-membered inorganic cyclic compound (aromatic).

-

Pyridine, a 6 membered heterocyclic organic compound, methine hydrogen atoms implied, not shown, and delocalized π-electrons shown as discrete bonds (aromatic).

-

Azepine, a 7-membered heterocyclic organic compound (non-aromatic).

Complex and polycyclic examples

[edit]The following are examples of cyclic compounds exhibiting more complex ring systems and stereochemical features:

- Complex cyclic compounds: Macrocyclic and polycyclic examples

-

Naphthalene, technically a polycyclic, more specifically a bicyclic compound, with circles showing delocalization of π-electrons (aromatic).

-

Decalin (decahydronaphthalene), the fully saturated derivative of naphthalene, showing the two stereochemistries possible for "fusing" the two rings together, and how this impacts the shapes available to this bicyclic compound (non-aromatic).

-

Longifolene, a polycyclic terpene natural product, and an example of a tricyclic molecule (non-aromatic).

-

Ingenol, a polycyclic terpene natural product with a tetracyclic core: with a 3- and a 5-membered carbocyclic rings, fused to two further 7-membered carbocyclic rings (non-aromatic).

-

Paclitaxel, a polycyclic natural product with a tetracyclic core: with a heterocyclic, 4-membered D ring, fused to further 6- and 8-membered carbocyclic (A/C and B) rings (non-aromatic), and with three further pendant phenyl-rings on its "tail", and attached to C-2 (abbrev. Ph, C6H5; aromatics).

-

A representative three-dimensional shape adopted by paclitaxel, as a result of its unique cyclic structure.[11]

-

Cholesterol, another polycyclic terpene natural product, in particular, a steroid, a class of tetracyclic molecules (non-aromatic).

-

Benzo[a]pyrene, a pentacyclic compound both natural and man-made, and delocalized π-electrons shown as discrete bonds (aromatic).

-

Pagodane, a complex, highly symmetric, man-made polycyclic compound (non-aromatic).

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ March, Jerry (1985). Advanced Organic Chemistry: Reactions, Mechanisms, and Structure (3rd ed.). New York: Wiley. ISBN 9780471854722. OCLC 642506595.[page needed]

- ^ Halduc, I. (1961). "Classification of inorganic cyclic compounds". Journal of Structural Chemistry. 2 (3): 350–8. Bibcode:1961JStCh...2..350H. doi:10.1007/BF01141802. S2CID 93804259.

- ^ Reymond, Jean-Louis (2015). "The Chemical Space Project". Accounts of Chemical Research. 48 (3): 722–30. doi:10.1021/ar500432k. PMID 25687211.

- ^ a b c d e f g William Reusch (2010). "Stereoisomers Part I" in Virtual Textbook of Organic Chemistry. Michigan State University. Archived from the original on 10 March 2015. Retrieved 7 April 2015.

- ^ a b IUPAC Gold Book heterocyclic compounds

- ^ a b Still, W.Clark; Galynker, Igor (1981). "Chemical consequences of conformation in macrocyclic compounds". Tetrahedron. 37 (23): 3981–96. doi:10.1016/S0040-4020(01)93273-9.

- ^ a b J. D. Dunitz (1968). J. D. Dunitz and J. A. Ibers (ed.). Perspectives in Structural Chemistry. Vol. 2. New York: Wiley. pp. 1–70.

- ^ Eliel, E.L., Wilen, S.H. and Mander, L.S. (1994) Stereochemistry of Organic Compounds, John Wiley and Sons, Inc., New York.[page needed]

- ^ Anet, F.A.L.; St. Jacques, M.; Henrichs, P.M.; Cheng, A.K.; Krane, J.; Wong, L. (1974). "Conformational analysis of medium-ring ketones". Tetrahedron. 30 (12): 1629–37. doi:10.1016/S0040-4020(01)90685-4.

- ^ Morris, Christopher G.; Press, Academic (1992). Academic Press Dictionary of Science and Technology. Gulf Professional Publishing. p. 120. ISBN 9780122004001. Archived from the original on 2021-04-13. Retrieved 2020-09-14.

- ^ Löwe, J; Li, H; Downing, K.H; Nogales, E (2001). "Refined structure of αβ-tubulin at 3.5 Å resolution". Journal of Molecular Biology. 313 (5): 1045–57. doi:10.1006/jmbi.2001.5077. PMID 11700061. Archived from the original on 2021-01-22. Retrieved 2020-09-14.

Further reading

[edit]- Jürgen-Hinrich Fuhrhop & Gustav Penzlin, 1986, "Organic synthesis: concepts, methods, starting materials," Weinheim, BW, DEU:VCH, ISBN 0895732467, see [1], accessed 19 June 2015.

- Michael B. Smith & Jerry March, 2007, "March's Advanced Organic Chemistry: Reactions, Mechanisms, and Structure," 6th Ed., New York, NY, USA:Wiley & Sons, ISBN 0470084944, see [2], accessed 19 June 2015.

- Francis A. Carey & Richard J. Sundberg, 2006, "Title Advanced Organic Chemistry: Part A: Structure and Mechanisms," 4th Edn., New York, NY, USA:Springer Science & Business Media, ISBN 0306468565, see [3], accessed 19 June 2015.

- Michael B. Smith, 2011, "Organic Chemistry: An Acid—Base Approach," Boca Raton, FL, USA:CRC Press, ISBN 1420079212, see [4], accessed 19 June 2015. [May not be most necessary material for this article, but significant content here is available online.]

- Jonathan Clayden, Nick Greeves & Stuart Warren, 2012, "Organic Chemistry," Oxford, Oxon, GBR:Oxford University Press, ISBN 0199270295, see [5], accessed 19 June 2015.

- László Kürti & Barbara Czakó, 2005, "Strategic Applications of Named Reactions in Organic Synthesis: Background and Detailed Mechanisms, Amsterdam, NH, NLD:Elsevier Academic Press, 2005ISBN 0124297854, see [6], accessed 19 June 2015.

External links

[edit]- Polycyclic+Compounds at the U.S. National Library of Medicine Medical Subject Headings (MeSH)

- Macrocyclic+Compounds at the U.S. National Library of Medicine Medical Subject Headings (MeSH)

Cyclic compound

View on GrokipediaStructure and Classification

Carbocycles

Carbocycles, also known as carbocyclic compounds, are a class of cyclic hydrocarbons composed exclusively of carbon atoms forming the ring structure, with hydrogen atoms attached to satisfy the valency of each carbon.[6] These compounds represent the simplest form of cyclic structures in organic chemistry, distinguishing them from heterocycles that incorporate heteroatoms such as nitrogen or oxygen.[6] Carbocycles are classified by ring size into several categories based on the number of carbon atoms in the ring. Small rings, containing 3 or 4 members, include examples like cyclopropane and cyclobutane, which exhibit significant strain due to deviations from ideal geometries. Common rings with 5 or 6 members, such as cyclopentane and cyclohexane, are more stable and prevalent in natural products and synthetic applications. Medium rings (7 to 11 members) and large rings (more than 12 members) are less common due to increased synthetic challenges but appear in complex molecules like macrolides.[7] Regarding saturation, carbocycles are further divided into saturated, unsaturated, and aromatic types. Saturated carbocycles, or cycloalkanes, feature only single bonds, exemplified by cyclohexane, which adopts a chair conformation to minimize angle and torsional strain, achieving bond angles near the ideal 109.5° for sp³-hybridized carbons and staggered adjacent bonds. Unsaturated carbocycles include cycloalkenes with one or more double bonds (e.g., cyclohexene) and cycloalkynes with triple bonds, though the latter are rare in small rings owing to high strain. Aromatic carbocycles, such as benzene as the prototype, possess a planar, conjugated system with delocalized π electrons; benzene's stability arises from satisfying Hückel's rule with 6 π electrons (4n + 2 where n = 1).[8] In small carbocycles like cyclopropane, ring strain is pronounced, comprising angle strain from the compressed 60° C-C-C bond angles (versus the tetrahedral ideal of 109.5°) and torsional strain from fully eclipsed C-H bonds on adjacent carbons.[9] This strain weakens the ring bonds, making small carbocycles more reactive than their acyclic counterparts.[9]Heterocycles

Heterocyclic compounds are cyclic organic structures that incorporate at least one heteroatom, such as nitrogen, oxygen, or sulfur, within the ring, replacing one or more carbon atoms typically found in carbocyclic analogs.[4] These heteroatoms introduce distinct electronic properties due to their differing electronegativities and valence electron configurations compared to carbon.[4] Heterocycles are classified by the type of heteroatom present, the ring size, and the degree of saturation. Nitrogen-containing examples include pyridine and pyrrole, oxygen heterocycles feature furan, and sulfur analogs include thiophene.[4] Ring sizes range from three-membered rings, such as aziridine for nitrogen or oxirane for oxygen, to larger systems like five-membered pyrrole or six-membered pyridine.[4] Saturation varies from fully saturated structures, exemplified by tetrahydrofuran (a five-membered oxygen ring), to unsaturated or aromatic variants like pyrrole.[4] Prominent motifs among heterocycles include five-membered aromatic rings such as pyrrole, furan, and thiophene, each possessing 6 π electrons for aromatic stability, with the heteroatom contributing to the π system via its lone pair (in pyrrole and furan) or p orbital (in thiophene).[10] In contrast, the six-membered pyridine maintains 6 π electrons akin to benzene, but the nitrogen's lone pair occupies an sp² orbital in the ring plane, excluding it from the π system and rendering it available for interactions.[11] These configurations highlight how heteroatoms modulate aromaticity compared to all-carbon cycles. The structural features of heterocycles are profoundly influenced by heteroatom electronegativity, which alters bond lengths and polarity. For instance, in pyridine, the higher electronegativity of nitrogen results in shorter C–N bonds relative to C–C bonds in benzene and imparts a dipole moment due to uneven electron distribution.[4] In pyrrole, delocalization of the nitrogen lone pair into the π system reverses the dipole orientation and enhances aromatic stabilization. Regarding acid-base properties, pyridine acts as a weak base with a pKₐ of 5.2 for its conjugate acid, owing to the accessible lone pair, while pyrrole exhibits very weak basicity (pKₐ ≈ 0 for conjugate acid) and notable acidity (pKₐ = 17.5 for N–H proton), as the lone pair participates in the aromatic sextet, stabilizing the deprotonated anion.[4] Heterocyclic motifs are ubiquitous in natural products and biomolecules, underscoring their fundamental role in biological systems, with over 85% of biologically active chemical entities incorporating such structures.[12][4]Inorganic Cycles

Inorganic cyclic compounds consist of ring structures formed by elements other than carbon, often involving p-block elements or transition metals, without relying on carbon skeletons for their cyclic framework. These compounds exhibit diverse bonding modes, including sigma bonds, delocalized pi systems, and coordination interactions, and they play key roles in materials science and synthetic chemistry due to their unique electronic properties. Unlike organic cycles, inorganic variants frequently display higher reactivity stemming from the inherent properties of the constituent elements, such as electronegativity differences or bond strain. Homocyclic inorganic cycles feature rings composed of a single type of atom. A classic example is octasulfur (S₈), forming a puckered eight-membered crown-shaped ring with S-S sigma bonds of approximately 2.04 Å, which provides thermal stability up to its melting point of 115 °C but allows ring-opening polymerization at higher temperatures. Heterocyclic inorganic cycles incorporate multiple non-carbon elements in the ring. Borazine (B₃N₃H₆), often termed the inorganic analog of benzene, features a planar six-membered ring with alternating boron and nitrogen atoms, supported by six pi electrons in a delocalized system that imparts weak aromatic character, though the B-N bond polarity (B δ⁺–N δ⁻) reduces overall stability compared to benzene and leads to hydrolysis in moist air. Cyclosiloxanes, such as octamethylcyclotetrasiloxane ([(CH₃)₂SiO]₄), form eight-membered Si-O rings with strong Si-O sigma bonds (bond energy ~452 kJ/mol), offering high thermal stability (boiling point 175 °C) and serving as precursors for silicone polymers, though the exocyclic methyl groups enhance solubility rather than participating in the cycle. Metallacycles involve metal atoms integrated into the ring or coordinating cyclic ligands. Ferrocene (Fe(C₅H₅)₂) exemplifies this type, with an iron(II) center sandwiched between two cyclopentadienyl rings through η⁵ coordination bonds, forming a stable 18-electron complex that exhibits reversible redox behavior and high thermal stability up to 400 °C. Bonding in such systems relies on dative interactions between metal d-orbitals and ligand pi systems, with stability influenced by the metal's oxidation state and ligand field strength; smaller rings may experience steric strain, increasing reactivity toward nucleophilic attack.Macrocycles and Polycycles

Macrocycles are cyclic molecules containing a ring of twelve or more atoms, typically featuring a central cavity that enables host-guest chemistry through selective binding of ions or molecules within the ring structure.[13] This cavity arises from the large ring size, which allows for conformational flexibility while maintaining a defined interior space for encapsulation, distinguishing macrocycles from smaller rings that lack such capacity.[14] In organic chemistry, macrocycles often incorporate heteroatoms to enhance binding specificity, facilitating applications in molecular recognition and transport.[15] Representative types of macrocycles include oxygen-based crown ethers, which are cyclic polyethers composed of repeating ethyleneoxy units that form complexes with metal cations via coordination to the oxygen atoms.[16] Nitrogen-based porphyrins consist of four pyrrole rings linked by methine bridges, creating a planar tetrapyrrole macrocycle with a conjugated π-system that supports metal chelation and light-harvesting properties.[17] Cyclodextrins, derived from enzymatic degradation of starch, are toroidal macrocycles formed by six to eight glucose units linked by α-1,4-glycosidic bonds, featuring a hydrophobic interior lined by secondary hydroxyl groups on the exterior for solubility in aqueous media.[18] Polycycles, in contrast, comprise multiple fused, bridged, or spiro-connected rings, introducing greater structural complexity beyond single macrocycles. Fused polycycles, such as naphthalene formed by two benzene rings sharing a common bond, exhibit extended conjugation and planarity that influence electronic properties.[19] Bridged polycycles like norbornane connect rings via a bridge of one or more atoms between non-adjacent positions, often resulting in rigid three-dimensional architectures. Spiro polycycles link rings at a single shared atom, creating independent cyclic systems with minimal overlap. Structural features in macrocycles include transannular interactions, such as hydrogen bonding or steric repulsions across the ring, which stabilize specific conformations and influence binding selectivity.[15] In polycycles, strain arises from angle distortions and torsional constraints, particularly in small or highly fused systems, while the degree of fusion—linear (end-to-end sharing), angular (side-by-side offset), or annular (fully encircling an inner ring)—determines overall planarity and reactivity.[20][19] The larger size of macrocycles imparts flexibility, allowing adaptive conformations for guest inclusion, whereas polycycles tend toward rigidity due to interconnected frameworks that restrict motion and enhance structural integrity. This flexibility in macrocycles contrasts with the inherent stiffness in polycycles, where fusion or bridging limits degrees of freedom. In supramolecular contexts, macrocycles and certain polycycles benefit from preorganization, wherein the host structure is predisposed to complementary guest binding, minimizing entropic penalties and enhancing association constants.[21][15] Such preorganization is pivotal for efficient host-guest interactions, as seen in crown ethers and cyclodextrins.[22]Nomenclature

The nomenclature of cyclic compounds follows systematic rules established by the International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry (IUPAC) to ensure unique and descriptive names based on structure. For monocarbocyclic compounds, saturated rings are named using the prefix "cyclo-" followed by the corresponding alkane name, such as cyclohexane for a six-carbon ring.[23] Numbering begins at a substituent and proceeds to give the lowest possible locants to other substituents or functional groups. Unsaturated monocarbocycles incorporate suffixes like "-ene" for double bonds or "-yne" for triple bonds, with locants indicating positions, as in cyclohexa-1,3-diene.[23] Heterocyclic compounds employ the Hantzsch-Widman system for rings of three to ten members, combining heteroatom prefixes (e.g., "aza-" for nitrogen, "oxa-" for oxygen) in order of seniority (O > S > N > P > As > Se > Te > Si > Ge > Sn > Pb > B > Al > Ga > In > Tl) with a stem indicating ring size and saturation (e.g., "-irene" for five-membered unsaturated, "-ole" for five-membered saturated with one double bond). Examples include pyrrole (five-membered nitrogen heterocycle) and furan (five-membered oxygen heterocycle).[23] For larger or more complex heterocycles, replacement nomenclature substitutes heteroatoms into the carbocyclic parent name, such as aziridine for a three-membered nitrogen ring. Numbering prioritizes the heteroatom of highest seniority at position 1, followed by the lowest locants for substituents.[23] Polycyclic compounds use distinct systems depending on ring connectivity. Fused polycycles, where rings share two adjacent atoms, are named by combining component names with fusion locants in brackets, indicating shared bond positions; ortho-fusion (sharing adjacent bonds) is standard for systems like naphthalene (two fused benzenes) and anthracene (three linearly fused benzenes).[24] Bridged polycycles apply the von Baeyer system, naming the structure as "bicyclo-" or "polycyclo-" followed by bracketed bridge lengths in descending order (total carbons minus bridges), as in bicyclo[2.2.1]heptane for norbornane.[23] Numbering starts at a bridgehead, traversing the longest bridge first. Macrocycles, typically rings with 12 or more members, often retain trivial names for common structures, such as cyclam for 1,4,8,11-tetraazacyclotetradecane, a 14-membered tetraaza ring.[25] For less common or larger systems, IUPAC recommends structure-based names using "cyclo-" with polyfunctional prefixes or replacement nomenclature, such as 1,4,7,10,13-pentaoxacyclopentadecane for a 15-membered crown ether analog. Special cases include indicators for unsaturation across all types, using "-ene" or "-yne" suffixes with locants, and basic stereodescriptors like "cis-" or "trans-" for disubstituted rings to denote relative configuration.[23] These conventions ensure consistency while accommodating structural diversity in cyclic compounds.Properties

Physical Properties

Cyclic compounds often exhibit higher boiling and melting points compared to their acyclic analogs of similar molecular weight, primarily due to the restricted rotation imposed by the ring structure, which enhances intermolecular forces such as van der Waals interactions. For instance, cyclohexane has a boiling point of 80.7°C, whereas n-hexane boils at 69°C. This trend is observed across cycloalkanes, where boiling points are typically 10–20°C higher than those of corresponding straight-chain alkanes. Melting points can also be influenced by ring size and conformation; cyclohexane, for example, melts at 6.5°C and forms a plastic crystal phase just below its melting point, attributed to the high conformational mobility of its chair conformation, allowing orientational disorder in the solid state. Solubility profiles of cyclic compounds vary with their composition. Hydrocarbon cyclics, such as cyclohexane, are generally nonpolar and exhibit low solubility in water (less than 0.01 g/100 mL at 25°C), preferring nonpolar solvents. The introduction of heteroatoms increases polarity and hydrophilicity; tetrahydrofuran (THF), a five-membered oxygen-containing cyclic ether, is fully miscible with water due to its polar C-O bond and ability to form hydrogen bonds. Density and viscosity in cyclic compounds are affected by ring strain, particularly in smaller rings. Cyclopropane, with significant angle strain from its 60° bond angles, has a liquid density of approximately 0.69 g/cm³ at its boiling point (-33°C), lower than expected for its compact structure compared to larger cycloalkanes like cyclohexane (0.78 g/cm³ at 20°C), reflecting the strain's impact on molecular packing. Viscosity tends to increase with ring size due to reduced flexibility, but strained small rings like cyclopropane show lower values in the liquid state owing to weaker intermolecular forces. Basic spectroscopic properties provide insights into ring structures. In infrared (IR) spectroscopy, cyclic compounds display characteristic C-H bending vibrations; for example, cyclopropane exhibits a weak C-H stretch around 3050 cm⁻¹ and ring deformation modes near 1000–1100 cm⁻¹ due to its strained geometry. Nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectroscopy reveals ring current effects in aromatic cycles, causing deshielding of protons on the ring, typically shifting ¹H signals to 6.5–8.0 ppm in benzene and related compounds, as the circulating π-electrons generate a local magnetic field.Chemical Stability and Reactivity

The stability of cyclic compounds is profoundly influenced by ring strain, a destabilizing factor arising from deviations in bond angles and torsional interactions within the ring structure. According to Baeyer strain theory, proposed by Adolf von Baeyer in 1885, small cyclic compounds experience significant angle strain because their internal bond angles deviate markedly from the ideal tetrahedral angle of 109.5°, leading to increased internal energy and reduced stability.[26] This strain diminishes in larger rings, where bond angles approach the tetrahedral ideal, resulting in greater stability for rings with five or six members. Reactivity trends in cyclic compounds are closely tied to ring size and strain levels. Highly strained small rings, such as cyclopropane with approximately 27 kcal/mol of ring strain, exhibit enhanced reactivity, particularly toward ring-opening reactions that relieve this tension, including additions of nucleophiles or electrophiles across the C-C bonds.[27] In contrast, five- and six-membered rings, like cyclopentane and cyclohexane, possess minimal strain—near zero for cyclohexane—and thus display stability comparable to acyclic alkanes, undergoing reactions at rates similar to open-chain counterparts.[26] General reactivity patterns for cyclic compounds include electrophilic additions to unsaturated variants, such as cycloalkenes, where the π-bond acts as a nucleophile toward electrophiles like H⁺ or halogens, proceeding via carbocation intermediates analogous to acyclic alkenes.[28] Saturated cyclic compounds, however, participate less frequently in substitution reactions compared to acyclic alkanes, primarily undergoing free radical halogenation at similar rates but with reduced versatility due to geometric constraints limiting access to reactive sites.[29] In heterocycles, the presence of heteroatoms like nitrogen introduces distinct reactivity profiles, often enhancing susceptibility at heteroatom positions. For instance, the electron-deficient nitrogen in pyridine facilitates nucleophilic attack, as the lone pair on nitrogen withdraws electron density from the ring, promoting addition-elimination mechanisms at positions ortho or para to the nitrogen.[4] Thermal and photochemical stability varies with ring size, with smaller rings prone to decomposition pathways that alleviate strain. Cyclobutane, for example, undergoes thermal ring opening at elevated temperatures (around 400–500°C) via a diradical mechanism to yield ethylene, a unimolecular process with an activation energy of approximately 61 kcal/mol.[30] Larger rings generally resist such decompositions, maintaining integrity under conditions that would isomerize acyclic analogs.Aromaticity

Aromaticity refers to the exceptional stability arising from the delocalization of π electrons in certain cyclic, planar, and fully conjugated molecular systems that contain π electrons, where is a non-negative integer, as formulated in Hückel's rule.[31] This rule, derived from quantum mechanical calculations on benzene and related compounds, predicts enhanced thermodynamic stability due to the complete filling of molecular orbitals in a cyclic conjugated system.[32] Many carbocyclic and heterocyclic compounds exhibit this property, distinguishing them from non-aromatic cyclic structures. Key criteria for aromaticity include energetic stabilization from π electron delocalization, which lowers the overall energy compared to hypothetical localized models; structural uniformity, evidenced by equal or nearly equal bond lengths in the ring (e.g., all C-C bonds in benzene are approximately 1.39 Å); and magnetic effects, such as a diamagnetic ring current that induces characteristic shielding in NMR spectroscopy for protons inside the ring and deshielding for those outside.[33] These features collectively confirm the cyclic conjugation and electron delocalization. Benzene exemplifies aromaticity with its six π electrons from three double bonds, resulting in high stability and resistance to addition reactions.[32] Larger annulenes like [34]annulene, with 18 π electrons (), also display aromatic character when planar, showing alternating inner and outer proton signals in NMR consistent with a diatropic ring current.[35] Heteroaromatic compounds such as furan and pyrrole achieve the required six π electrons by incorporating lone pairs from the heteroatom: in furan, the oxygen's p-orbital lone pair contributes two electrons to the π system, while the other lone pair remains in an sp² hybrid orbital; in pyrrole, the nitrogen's lone pair fully participates in the π delocalization.[36] In contrast, anti-aromaticity destabilizes cyclic, planar, conjugated systems with π electrons, leading to reactive and distorted structures.[32] Cyclobutadiene, with four π electrons, exemplifies this instability, exhibiting a rectangular geometry with unequal bond lengths and high reactivity, quantified by a destabilization energy of about 20-30 kcal/mol relative to localized models.[37] Modern extensions of aromaticity include Möbius aromaticity in twisted cyclic systems, where π electrons can stabilize the molecule due to topological overlap, as observed in certain metallaborocycles.[38] All-metal clusters, such as the square-planar Al₄²⁻ anion, demonstrate aromaticity through delocalized electrons in metal-based orbitals, with multiple σ and π contributions enhancing stability.[39]Isomerism

Structural Isomerism

Structural isomerism in cyclic compounds refers to constitutional isomers that share the same molecular formula but differ in the connectivity of their atoms, particularly in ring size, ring arrangement, or substituent placement. This type of isomerism arises because cyclic structures allow for various ways to arrange carbon atoms into rings or combine rings with chains while maintaining the overall formula. For instance, compounds with the formula C₆H₁₂ can exist as cyclohexane (a single six-membered ring), methylcyclopentane (a five-membered ring with a methyl substituent), or 1-hexene (an acyclic chain with a double bond), illustrating how ring formation versus chain structures leads to distinct connectivities.[40] Key types of structural isomerism in cyclic compounds include ring-chain isomerism, positional isomerism, and variations in functional group placement. Ring-chain isomerism occurs when a cyclic structure interconverts with an open-chain analog, often involving a double bond in the chain to match the hydrogen deficiency of the ring, as seen in the C₆H₁₂ examples above. Positional isomerism involves differences in the location of substituents or functional groups on the ring, such as ortho-, meta-, and para-chlorotoluene for benzene derivatives with formula C₇H₇Cl, where the chlorine atom attaches at different positions relative to the methyl group. Functional group placement isomerism can manifest in cyclic systems through relocation of heteroatoms or multiple bonds within the ring, like the difference between 2-methyltetrahydrofuran (a five-membered ring with one oxygen and a methyl substituent) and tetrahydropyran (a six-membered ring with one oxygen), both C₅H₁₀O.[40] In more complex polycyclic systems, structural isomerism appears in fused versus bridged ring arrangements. For compounds with formula C₁₀H₁₆, such as monoterpenes, examples include bridged bicyclic structures like α-pinene (with a four-membered bridge connecting two rings) and fused bicyclic variants like those in certain sesquiterpene precursors, where the rings share adjacent atoms versus being connected by a bridge, leading to different overall topologies. These connectivity differences influence molecular properties without altering the atom count.[41] Energy differences among structural isomers often favor certain ring sizes due to variations in ring strain. Six-membered rings, like cyclohexane, exhibit minimal strain energy (approximately 0 kJ/mol) because their bond angles approximate the ideal tetrahedral 109.5° and adopt low-energy conformations, whereas three-membered rings like cyclopropane suffer high angle strain (bond angles of 60°) and torsional strain, resulting in about 115 kJ/mol total strain energy, making smaller rings less stable. This stability preference explains why six-membered cyclic structures predominate in natural products and synthetic compounds over three- or four-membered alternatives with the same formula.[42] Detection of structural isomers begins with confirming the molecular formula, which is identical for all isomers, using techniques like combustion analysis to determine elemental composition and mass spectrometry to identify the molecular ion peak and exact mass. These methods verify the formula (e.g., C₆H₁₂) but require additional spectroscopy, such as NMR, to distinguish connectivity; however, initial formula confirmation is essential to establish the presence of isomerism.[43]Stereoisomerism

Stereoisomerism in cyclic compounds refers to the existence of isomers that have identical molecular formulas and connectivity but differ in the spatial arrangement of their atoms.[44] This phenomenon arises due to the constrained geometry of ring structures, which can impose restrictions on rotation and lead to distinct stereochemical configurations.[45] Geometric isomerism, also known as cis-trans isomerism, is common in cyclic compounds where rotation around bonds is limited by the ring framework. In cycloalkanes and cycloalkenes, substituents on adjacent ring carbons can adopt cis (same side) or trans (opposite sides) orientations; for instance, cis-1,2-dimethylcyclopropane features both methyl groups on the same face of the ring, while the trans isomer has them on opposite faces, resulting in distinct physical properties.[46] This isomerism is particularly pronounced in small rings like cyclopropane and cyclobutane, where the rigidity prevents interconversion without bond breaking.[47] Optical isomerism in cyclic compounds often manifests through chirality without traditional tetrahedral stereocenters, due to the ring's influence on molecular asymmetry. For example, trans-cyclooctene exhibits chirality arising from its twisted, non-superimposable conformation, making it optically active despite lacking a chiral carbon.[48] Atropisomerism, a subtype of axial chirality, occurs in biaryl cyclic systems where steric hindrance around the aryl-aryl bond restricts rotation, as seen in compounds like 2,2'-binaphthol (BINOL), leading to stable enantiomers. In polycyclic compounds, more complex forms of stereoisomerism emerge, such as axial chirality in helicenes, where ortho-fused aromatic rings form a helical structure that is inherently chiral and non-superimposable on its mirror image.[49] Planar chirality is exemplified by paracyclophanes, like [2.2]paracyclophane derivatives, where the bridged benzene rings create an asymmetric plane due to the non-planar arrangement, resulting in enantiomers that cannot interconvert without disrupting the cycle.[50] Resolution of these stereoisomers typically involves converting enantiomers into diastereomers using a chiral auxiliary, which can then be separated based on their differing physical properties, such as solubility or chromatographic behavior.[51] Conformational restrictions in rings can influence the stability of these stereoisomers but do not alter their fixed spatial arrangements.[45]Conformational Analysis

Conformational analysis examines the various three-dimensional arrangements of atoms in cyclic compounds that arise from rotations about single bonds, termed conformations. These spatial forms are interconvertible at room temperature without bond breakage and thus do not qualify as distinct isomers, unlike configurational stereoisomers requiring higher energy barriers for interconversion. Pioneered by Derek Barton and Odd Hassel, this field elucidates how conformational preferences influence molecular stability, reactivity, and properties in cyclic systems.[52] In carbocyclic systems, cyclohexane exemplifies conformational behavior. Its lowest-energy chair conformation features staggered carbon-carbon bonds and near-tetrahedral angles (approximately 111°), minimizing both angle and torsional strain. Higher-energy forms include the boat, which suffers from four eclipsed C-C bonds and flagpole interactions adding about 6.9 kcal/mol relative to the chair, and the twist-boat, a partially relieved boat variant at roughly 5.5 kcal/mol above the chair. Ring inversion, or chair flip, occurs via a half-chair transition state passing through the twist-boat, with an activation barrier of about 10-12 kcal/mol, allowing rapid equilibration (on the order of 10^5 s^-1 at room temperature). Substituents prefer equatorial positions in the chair to avoid 1,3-diaxial interactions; for example, an axial methyl group in methylcyclohexane incurs steric repulsion with two syn-axial hydrogens, raising its energy by approximately 1.7 kcal/mol compared to the equatorial conformer, favoring the latter by over 95% at equilibrium.[53][54] Heterocyclic rings exhibit analogous yet modified conformational landscapes due to heteroatom effects on bond lengths and electronics. In five-membered furanose rings, common in carbohydrates, the envelope conformation predominates, where one atom lies out of the plane defined by the other four, balancing pseudorotation to minimize strain; this allows flexibility, with specific envelopes (e.g., C2'-endo or C3'-endo) stabilized by substituents like hydroxyl groups. Six-membered heterocycles such as tetrahydropyran adopt a chair-like form akin to cyclohexane, but the shorter C-O bonds (1.43 Å vs. 1.54 Å for C-C) distort it slightly; transitional half-chair conformations appear during ring inversion, with barriers similar to cyclohexane (around 11 kcal/mol).[55][56] Conformational interconversion barriers vary with ring size. Small rings (3-5 members) exhibit low barriers due to flexible puckering, enabling pseudorotation without high activation energies. In medium rings (8-12 members), barriers rise owing to transannular steric clashes and restricted flexibility; for instance, cyclodecane's preferred boat-chair-boat () conformation has an inversion barrier exceeding 15 kcal/mol, slowing interconversion and allowing isolation of conformers at low temperatures via NMR. Larger rings (>12 members) approach acyclic flexibility with even lower barriers, often below 10 kcal/mol.[53][57] Computational tools, particularly molecular mechanics (MM) methods, predict these energy landscapes efficiently. Allinger's MM2 force field, incorporating torsional (V1, V2 terms) and van der Waals potentials, accurately models hydrocarbon ring conformations and barriers, with extensions to heterocycles via adjusted parameters for heteroatoms. These empirical approaches complement experimental techniques like NMR and X-ray diffraction for mapping minima and transition states.[54]Synthesis

Ring-Forming Reactions

Ring-forming reactions are essential synthetic strategies for constructing cyclic compounds from acyclic precursors, primarily through intramolecular cyclization where reactive functional groups within a single molecule approach each other to form a new ring bond.[58] This process often involves nucleophilic or electrophilic attack, leading to the formation of rings of various sizes, with five- and six-membered rings being particularly favored due to their thermodynamic stability.[58] A prominent class of ring-forming reactions is cycloaddition, exemplified by the Diels-Alder reaction, a [4+2] pericyclic cycloaddition between a 1,3-diene and a dienophile. In the classic example, 1,3-butadiene reacts with ethylene to produce cyclohexene, proceeding through a concerted mechanism with suprafacial geometry.[59] This reaction is stereospecific, preserving the stereochemistry of the dienophile, and is widely used for constructing six-membered carbocycles.[60] Pericyclic reactions also enable ring formation via electrocyclic processes, where a conjugated π-system undergoes ring closure. For instance, a thermal 4π-electron electrocyclic reaction converts 1,3-butadiene to cyclobutene through conrotatory motion, as predicted by the Woodward-Hoffmann rules.[61] Sigmatropic shifts contribute to the synthesis of cyclic compounds through rearrangements like the [3,3]-sigmatropic Cope rearrangement of 1,5-dienes under thermal conditions. Carbonyl-based condensations provide another key route, particularly for heterocyclic and carbocyclic rings. Intramolecular aldol condensation of dialdehydes or keto-aldehydes forms five- or six-membered rings via enolate addition to a carbonyl, followed by dehydration, as seen in the synthesis of cyclopentenones from 1,4-dicarbonyl compounds.[62] The Dieckmann condensation, an intramolecular Claisen variant, cyclizes diesters to β-keto esters, preferentially forming five-membered rings from 1,5-diesters through base-catalyzed enolate attack on the ester carbonyl.[63] Metal-catalyzed methods, such as olefin metathesis, facilitate ring formation by redistributing alkene substituents via metal carbene intermediates. In ring-closing metathesis, dienes undergo intramolecular coupling to form cyclic alkenes and ethylene, enabled by ruthenium catalysts like Grubbs' complexes, applicable to rings from five to thirty members.[64] Stereoselectivity in these reactions often follows specific rules; in the Diels-Alder cycloaddition, the endo rule dictates that the dienophile's substituents orient toward the diene in the transition state, leading to higher yields of endo products due to secondary orbital interactions.[65] This preference enhances the efficiency of asymmetric syntheses when chiral auxiliaries are employed.[66]Ring-Closing Methods

Ring-closing methods encompass intramolecular reactions that convert linear bifunctional molecules into cyclic structures by forming a new bond between reactive termini, often driven by the release of small molecules like ethylene or by thermodynamic favorability in smaller rings. These approaches are particularly valuable in organic synthesis for constructing carbocycles and heterocycles with precise control over ring size and substitution. Unlike broader ring-forming strategies, ring-closing methods emphasize chain cyclization without intermolecular interference, enabling efficient access to strained or medium-sized rings.[67] One prominent ring-closing technique is ring-closing metathesis (RCM), which involves the intramolecular olefin metathesis of dienes catalyzed by ruthenium-based Grubbs catalysts to form cycloalkenes and release ethylene. Developed and popularized in the early 1990s, RCM is highly efficient for forming 5- to 7-membered rings, with second-generation Grubbs catalysts (e.g., those bearing N-heterocyclic carbene ligands) enabling even strained 4-membered rings or larger macrocycles under mild conditions. For instance, the RCM of diallyl ether using a Grubbs catalyst yields 2,5-dihydrofuran, a 5-membered oxygen-containing cycle, demonstrating its utility in heterocyclic synthesis. This method's versatility stems from its tolerance of polar functional groups and ability to proceed in various solvents, making it a staple for complex molecule assembly.[68][69] Cycloaddition reactions provide another key route for ring closure, particularly [2+2] cycloadditions that forge four-membered rings through the concerted addition of unsaturated partners. In the case of ketenes and alkenes, these thermal [2+2] cycloadditions generate cyclobutanones, offering a direct method for small strained carbocycles; intramolecular variants allow precise control over substitution patterns. Lewis acid promotion, such as with TiCl4, enhances regioselectivity and yield by coordinating to the ketene carbonyl, facilitating closure in electron-deficient systems. Photochemical [2+2] cycloadditions of alkenes can also close chains into cyclobutanes, though they are less common for ketene-alkene pairs due to the thermal pathway's efficiency. These reactions are stereospecific, preserving alkene geometry in the product, and are widely used for synthesizing natural product fragments containing cyclobutane motifs.[70] Anionic and cationic cyclizations represent nucleophilic or electrophilic intramolecular displacements that close chains via charged intermediates. Cationic variants, such as halonium ion-initiated closures, are effective for oxygen heterocycles; for example, iodocyclization of homoallylic alcohols with N-iodosuccinimide generates a halonium ion that is attacked by the alcohol oxygen, affording 2,5-disubstituted tetrahydrofurans with high diastereoselectivity. Anionic cyclizations, like those involving enolates or carbanions, similarly promote closure but are less emphasized here due to the prevalence of cationic methods for ether formation. These processes often require Lewis acids or electrophilic activators to generate the reactive species, proceeding through five- or six-exo modes for optimal efficiency.[71] The feasibility of ring closure is governed by Baldwin rules, which predict stereoelectronic preferences based on the geometry of the approaching nucleophile and electrophile in forming 3- to 7-membered rings. Formulated in 1976, these rules classify cyclizations as exo or endo (relative to the forming ring) and tet (tetrahedral) or trig (trigonal) based on the electrophile's hybridization; for instance, 5-exo-tet closures (e.g., carbanion attack on a tetrahedral carbon) are favored due to optimal orbital overlap, while 5-endo-tet are disfavored. Exo-trig modes, common in cationic cyclizations like halonium closures, are generally preferred for five- and six-membered rings, guiding synthetic design to avoid low-yield pathways. These guidelines, supported by computational and experimental data, highlight how transition state rigidity influences success rates.[72][73] Yields in ring-closing reactions are influenced by thermodynamic factors, including strain in small rings and entropy penalties in large ones. Small rings (3- to 4-membered) suffer angle strain from compressed bond angles (e.g., 60° in cyclopropane vs. ideal 109.5° for sp³ carbons) and torsional strain from eclipsed bonds, raising activation energies and reducing closure efficiency unless compensated by reaction exothermicity. Conversely, large rings (8+ members) face unfavorable entropy loss upon cyclization, as the flexible linear precursor loses rotational and conformational freedom, with ΔS‡ becoming more negative as chain length increases; this is quantified by effective molarity decreasing from ~10⁵ M for 5-membered rings to ~10⁻² M for 12-membered. Optimal yields thus occur for medium rings (5- to 7-membered), where strain is minimal and entropy loss is manageable.[67][26]Ring Modifications

Ring modifications encompass a range of chemical transformations that alter the size or integrity of pre-existing cyclic structures, enabling the synthesis of diverse ring systems by expansion, contraction, or cleavage. These reactions are pivotal in organic chemistry for adjusting ring strain, introducing functional groups, or facilitating downstream synthetic steps. Common strategies include nucleophilic or catalytic openings, migratory rearrangements, and oxidative cleavages, often proceeding under mild conditions with high selectivity influenced by substrate symmetry and reaction parameters.[74] Ring-opening reactions disrupt the cyclic framework to generate acyclic derivatives, frequently incorporating heteroatoms or unsaturations. A prominent example is the hydrolysis of epoxides, three-membered cyclic ethers, which can be catalyzed by acids or bases. In acid-catalyzed hydrolysis, protonation of the oxygen facilitates nucleophilic attack by water at the more substituted carbon, yielding trans-diols via an SN1-like mechanism with inversion at the attacked site.[75] Base-catalyzed variants involve direct nucleophilic attack by hydroxide at the less hindered carbon, also producing anti-diols but under milder conditions suitable for sensitive substrates.[76] Another metathesis-based approach is ring-opening metathesis depolymerization, where strained cyclic polymers like poly(norbornene) are cleaved using ruthenium or molybdenum catalysts to afford monomers or functionalized chains, reversing polymerization processes for recycling or modification. Ozonolysis of cycloalkenes exemplifies oxidative ring-opening, where ozone adds across the double bond to form a primary ozonide that decomposes to a carbonyl oxide intermediate, ultimately yielding dicarbonyl compounds such as dialdehydes or keto-aldehydes upon reductive workup.[77] Ring expansion increases the ring size by inserting atoms, often via migratory processes that preserve stereochemistry. The Beckmann rearrangement converts cyclic oximes to lactams, effectively expanding the ring by one atom through migration of the anti-alkyl group to the nitrogen under acidic conditions, as demonstrated in the synthesis of expanded macrolides from erythromycin oximes.[78] Diazomethane-mediated insertion provides another route, where the diazo compound adds to ketones to form homologous ketones via a carbene intermediate that rearranges with migration of one adjacent group, commonly used for enlarging cyclobutanones to cyclopentanones.[79] These methods are particularly valuable for accessing medium-sized rings from smaller, more stable precursors. Ring contraction reduces ring size through skeletal reorganization, typically involving carbocation or carbene migrations. The Wolff rearrangement of α-diazo ketones generates ketenes via loss of nitrogen and alkyl migration, leading to smaller rings when trapped intramolecularly, as seen in the photoinduced contraction of cyclohexanones to cyclopentanecarboxylic acids.[80] The pinacol rearrangement achieves similar outcomes from vicinal diols under acidic conditions, where dehydration forms a carbocation that undergoes 1,2-migration of a ring bond, contracting the cycle while forming a carbonyl, exemplified by the conversion of cyclohexane-1,2-diols to cyclopentanones.[81] In unsymmetrical rings, regioselectivity governs product distribution, dictated by electronic and steric factors. For epoxide hydrolysis, acid catalysis favors attack at the more substituted carbon due to partial carbocation character, while base catalysis prefers the less hindered site. In the Beckmann rearrangement, the anti-migrating group relative to the oxime hydroxyl determines the insertion site, with electron-donating substituents enhancing migration aptitude.[82] Diazomethane expansions of β-substituted cyclobutanones show preferential migration of the less substituted α-carbon, influenced by β-group electronics.[83] Such control allows targeted synthesis of regioisomers for building molecular complexity.Applications

In Organic Synthesis

Cyclic compounds serve as essential scaffolds in total synthesis, providing rigid frameworks that facilitate the construction of complex molecular architectures. In the synthesis of steroids, for instance, cyclohexanone derivatives are employed in the Robinson annulation to form fused ring systems, enabling the efficient assembly of the characteristic tetracyclic core.[84] This approach, pioneered in the early 20th century, has been instrumental in achieving total syntheses of natural and modified steroids by leveraging the annulation to install key carbon-carbon bonds with high regioselectivity.[84] Cyclic acetals play a crucial role as protecting groups for carbonyl functionalities during multi-step syntheses, shielding aldehydes and ketones from unwanted reactivity under basic or nucleophilic conditions. These derivatives, typically formed from 1,2- or 1,3-diols such as ethylene glycol, exhibit remarkable stability in neutral to basic media while allowing selective deprotection under acidic aqueous conditions.[85] Their use is widespread in carbohydrate and polyketide syntheses, where temporary masking of carbonyls prevents side reactions and enables orthogonal manipulation of other functional groups.[85] In asymmetric synthesis, cyclic oxazolidinones function as chiral auxiliaries to impose stereocontrol in aldol reactions, as exemplified by the Evans aldol protocol. Here, N-acyl oxazolidinones derived from chiral amino alcohols generate boron enolates that add to aldehydes with high diastereoselectivity, yielding syn-aldol products in enantiomerically enriched form. This methodology has been pivotal in constructing stereogenic centers within polyketide and alkaloid frameworks, with the auxiliary recoverable for reuse after cleavage. Decalin motifs, as bicyclic trans-fused cyclohexane units, mimic the core structures of terpenoid natural products and serve as versatile intermediates in their synthesis. For example, enantiomerically pure decalins provide a preorganized scaffold for appending side chains in the total synthesis of clerodane diterpenes, streamlining the assembly of polycyclic terpenoids through stereocontrolled functionalizations.[86] Such mimics reduce synthetic steps by exploiting the inherent rigidity of the decalin system to dictate subsequent bond formations. The incorporation of cyclic elements in synthetic design enhances overall efficiency by constraining molecular conformations, thereby reducing degrees of freedom and improving reaction selectivity. This preorganization minimizes entropic penalties in transition states, favoring desired pathways over competing ones and enabling higher yields in stereoselective transformations./17:Aldehydes_and_Ketones-_The_Carbonyl_Group/17.08:_Acetals_as_Protecting_Groups)In Materials and Polymers

Cyclic compounds play a pivotal role in the development of advanced polymers through cycloaddition reactions, particularly in the synthesis of conjugated materials like polyacetylene derivatives. These polymers are produced via ring-opening metathesis polymerization (ROMP) of cyclooctatetraene (COT) derivatives, where the strained eight-membered ring undergoes metathesis to yield soluble, highly conjugated chains with enhanced electronic properties suitable for optoelectronic applications.[87] For instance, substituted COT monomers enable the formation of polyacetylenes with controlled solubility and conductivity, addressing the insolubility issues of traditional polyacetylene.[88] In polymer production, cyclic oligomers serve as intermediates or by-products that influence material properties and processing. During nylon 6 synthesis, cyclic oligomers such as dimers and higher trimers form through transamidation reactions, comprising up to 1-2% of the product and contributing to melt viscosity while requiring removal for high-purity applications.[89] Similarly, ring-opening metathesis polymerization of norbornene yields poly(norbornene), a versatile elastomer with exceptional toughness and low gas permeability, widely used in optical films and tires due to the rigid bicyclic structure retained in the polymer backbone.[90] Supramolecular materials leverage cyclic hosts like calixarenes and cyclodextrins to form dynamic assemblies with tunable functionalities. Calixarenes, with their basket-shaped cavities, act as selective hosts in chemical sensors by forming inclusion complexes with ions or neutral molecules, enabling detection of analytes through changes in fluorescence or conductivity.[91] Cyclodextrins, toroidal oligosaccharides, create inclusion complexes with hydrophobic guests in aqueous environments, facilitating the design of self-assembling hydrogels and drug-delivery matrices with improved stability and responsiveness.[92] Nanocarbons represent another class where cyclic motifs define structural integrity and performance. Fullerenes, exemplified by C60 (buckyball), feature a fused polycyclic cage of 60 carbon atoms, imparting electron-accepting capabilities essential for photovoltaic devices and lubricants with reduced friction. Carbon nanotubes, conceptualized as rolled-up sheets of graphene forming seamless cylindrical cycles, exhibit extraordinary mechanical strength and thermal conductivity, making them ideal reinforcements in composite materials for aerospace and electronics.[93] The incorporation of cyclic units in these materials generally enhances rigidity and thermal stability by restricting chain mobility and increasing decomposition temperatures. For example, polymers with cyclic topologies, such as those from ROMP, show glass transition temperatures elevated by 20-50°C compared to linear analogs, due to the reduced conformational entropy.[94] Macrocycles further contribute to structural roles in these systems by promoting ordered packing in thin films and assemblies.[95]In Biological and Medicinal Chemistry

Cyclic compounds are ubiquitous in biological systems, serving essential structural and functional roles. Steroids, such as cholesterol, exemplify fused carbocyclic rings that form the backbone of cell membranes and precursors for hormones like cortisol and testosterone, maintaining membrane fluidity and signaling pathways. Porphyrins, featuring a tetrapyrrole macrocyclic structure, are central to heme in hemoglobin and myoglobin, enabling oxygen transport and storage through coordination with iron. Alkaloids, often containing nitrogen heterocycles like the pyrrolidine and pyridine rings in nicotine, occur in plants as defense mechanisms and influence neurotransmission in animals upon ingestion. In medicinal chemistry, cyclic structures underpin many antibiotics by exploiting their reactivity and steric properties. Beta-lactam antibiotics, including penicillins, feature a strained four-membered beta-lactam ring that mimics the D-alanyl-D-alanine substrate of bacterial penicillin-binding proteins (PBPs), irreversibly inhibiting cell wall synthesis and leading to bacterial lysis.[96] Macrocyclic antibiotics like vancomycin, a tricyclic glycopeptide with a rigid heptapeptide core, bind to the D-ala-D-ala terminus of peptidoglycan precursors via hydrogen bonding, preventing cross-linking and exhibiting potent activity against Gram-positive bacteria, including methicillin-resistant strains.[97] Cyclic compounds enhance drug design by providing conformational rigidity that improves target binding affinity and selectivity. In cyclic peptides, such as cyclosporine, the macrocyclic constraint reduces entropy loss upon binding, stabilizing interactions with protein targets like calcineurin and enabling oral bioavailability despite their size. Heterocycles dominate pharmaceutical scaffolds, with approximately 90% of approved small-molecule drugs incorporating at least one ring system, often nitrogen-containing, to optimize solubility, metabolic stability, and receptor interactions.[98] Enzymatic metabolism frequently involves ring modifications to facilitate detoxification or activation. Cytochrome P450 enzymes (CYPs), such as CYP3A4, catalyze epoxidation of unsaturated rings in substrates like alkenes or aromatics, inserting oxygen to form epoxides that can rearrange or conjugate for excretion, as seen in the metabolism of carbamazepine to its 10,11-epoxide.[99] These transformations occur via a reactive iron-oxo intermediate, with regioselectivity determined by substrate orientation in the active site.[100] Strained cyclic structures can generate reactive metabolites contributing to toxicity. Epoxides from CYP-mediated ring oxidation, such as those derived from furans, act as electrophiles that covalently bind nucleophilic sites on proteins and DNA, inducing hepatotoxicity or carcinogenicity, as evidenced in the metabolism of lamotrigine where the arene oxide intermediate depletes glutathione.[101] Cyclopropyl rings in drugs like AZD1979 undergo glutathione S-transferase-catalyzed ring-opening to form thioether adducts, highlighting how ring strain amplifies bioactivation risks.[102]Notable Examples

Monocyclic Compounds

Monocyclic compounds, featuring a single ring structure, serve as foundational examples in organic and inorganic chemistry, illustrating key principles of stability, reactivity, and applications across disciplines. These molecules range from highly strained small rings to stable aromatic systems, each exhibiting unique properties that influence their industrial and biological roles. Among carbocyclic monocycles, cyclopropane exemplifies extreme ring strain due to its 60° bond angles deviating significantly from the ideal tetrahedral 109.5°, resulting in an estimated strain energy of approximately 29 kcal/mol.[103] This strain confers high reactivity, making cyclopropane useful in pharmaceutical synthesis where the ring acts as a bioisostere for ethylene, appearing in over 60 marketed drugs.[104] Cyclopentadiene, a five-membered carbocycle with two conjugated double bonds, is renowned for its role as a diene in Diels-Alder cycloadditions, enabling efficient construction of bicyclic frameworks due to its fixed s-cis conformation and high reactivity.[105] Benzene stands as the archetypal aromatic monocycle, a six-membered ring with delocalized π-electrons providing exceptional stability; its resonance energy, derived from hydrogenation experiments, is about 36 kcal/mol, far exceeding that of hypothetical localized structures.[106] This aromaticity was first conceptualized by August Kekulé in 1865 through a visionary dream of a snake biting its tail, proposing the cyclic structure that resolved benzene's enigmatic stability and reactivity.[107] Heterocyclic monocycles incorporate heteroatoms into the ring, altering electronic properties and enabling diverse biological functions. Pyrrole, a five-membered ring with nitrogen, forms the core subunit in porphyrin biosynthesis, where four pyrrole-like units derived from porphobilinogen assemble into the heme prosthetic group essential for oxygen transport in hemoglobin.[108] Furan, an oxygen-containing five-membered ring, is produced industrially from biomass via dehydration of pentoses in lignocellulosic materials, yielding furfural as a key platform chemical for resins and biofuels.[109] Piperidine, a saturated six-membered ring with nitrogen, serves as the structural base for numerous alkaloids, such as piperine from black pepper, imparting pharmacological properties like analgesia through its secondary amine functionality.[110] Inorganic monocycles highlight elemental ring formations beyond carbon frameworks. Elemental sulfur's predominant allotrope is cyclo-S₈, a puckered eight-membered ring with S-S bond lengths of 206 pm and angles near 108°, stable at room temperature and melting to a viscous liquid above 118°C due to ring opening and polymerization.[111] These examples underscore how monocyclic structures, despite their simplicity, underpin reactivity patterns observed in more complex cyclic systems.Polycyclic and Complex Structures