Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

United States Department of Homeland Security

View on Wikipedia

| |

Flag of the U.S. Department of Homeland Security | |

| |

Headquarters of the U.S. Department of Homeland Security in Washington D.C. | |

| Agency overview | |

|---|---|

| Formed | November 25, 2002 |

| Jurisdiction | U.S. federal government |

| Headquarters | St. Elizabeths West Campus, Washington, D.C., U.S. 38°51′17″N 77°00′00″W / 38.8547°N 77.0000°W |

| Employees | 240,000 (2018)[1] |

| Annual budget | $103.2 billion (FY 2024)[2] |

| Agency executives | |

| Child agency |

|

| Key document | |

| Website | dhs.gov |

| Agency ID | 7000 |

"The DHS March" | |

The United States Department of Homeland Security (DHS) is the U.S. federal executive department responsible for public security, roughly comparable to the interior, home, or public security ministries in other countries. Its missions involve anti-terrorism, civil defense, immigration and customs, border control, cybersecurity, transportation security, maritime security and sea rescue, and the mitigation of weapons of mass destruction.[3]

It began operations on March 1, 2003, after being formed as a result of the Homeland Security Act of 2002, enacted in response to the September 11 attacks. With more than 240,000 employees,[1] DHS is the third-largest Cabinet department, after the departments of Defense and Veterans Affairs.[4] Homeland security policy is coordinated at the White House by the Homeland Security Council. Other agencies with significant homeland security responsibilities include the departments of Health and Human Services, Justice, and Energy.

History

[edit]Creation

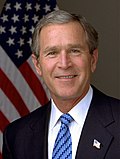

[edit]In response to the September 11 attacks, President George W. Bush announced the establishment of the Office of Homeland Security (OHS) to coordinate "homeland security" efforts. The office was headed by former Pennsylvania governor Tom Ridge, who assumed the title of Assistant to the President for Homeland Security. The official announcement states:

The mission of the Office will be to develop and coordinate the implementation of a comprehensive national strategy to secure the United States from terrorist threats or attacks. The Office will coordinate the executive branch's efforts to detect, prepare for, prevent, protect against, respond to, and recover from terrorist attacks within the United States.[5]

Ridge began his duties as OHS director on October 8, 2001.[6] On November 25, 2002, the Homeland Security Act established the Department of Homeland Security to consolidate U.S. executive branch organizations related to "homeland security" into a single Cabinet agency. In January 2003, the office was superseded, but not replaced by the Department of Homeland Security and the White House Homeland Security Council, both of which were created by the Homeland Security Act of 2002. The Homeland Security Council, similar in nature to the National Security Council, retains a policy coordination and advisory role and is led by the assistant to the president for homeland security.[5] The Gilmore Commission, supported by much of Congress and John Bolton, helped to solidify further the need for the department. The DHS incorporated the following 22 agencies.[7]

List of incorporated agencies

[edit]| Original agency | Original department | New agency or office after transfer |

|---|---|---|

| U.S. Customs Service | Treasury | U.S. Customs and Border Protection U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement |

| Immigration and Naturalization Service | Justice | U.S. Customs and Border Protection U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services |

| Federal Protective Service | General Services Administration | Management Directorate |

| Transportation Security Administration | Transportation | Transportation Security Administration |

| Federal Law Enforcement Training Center | Treasury | Federal Law Enforcement Training Center |

| Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service (part) |

Agriculture | U.S. Customs and Border Protection |

| Federal Emergency Management Agency | none | Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) |

| Strategic National Stockpile | Health and Human Services | Originally assigned to FEMA, but returned to HHS in July 2004 |

| National Disaster Medical System | Health and Human Services | Originally assigned to FEMA, but returned to HHS in August 2006 |

| Nuclear Incident Response Team | Energy | Responsibilities distributed within FEMA |

| Domestic Emergency Support Team | Justice | Responsibilities distributed within FEMA |

| Center for Domestic Preparedness | Justice (FBI) | Responsibilities distributed within FEMA |

| CBRN Countermeasures Programs | Energy | Science & Technology Directorate |

| Environmental Measurements Laboratory | Energy | Science & Technology Directorate |

| National Biological Warfare Defense Analysis Center |

Defense | Science & Technology Directorate |

| Plum Island Animal Disease Center | Agriculture | Science & Technology Directorate |

| Federal Computer Incident Response Center | General Services Administration | US-CERT, Office of Cybersecurity and Communications National Programs and Preparedness Directorate (now CISA) |

| National Communications System | Defense | Office of Cybersecurity and Communications National Programs and Predaredness Directorate |

| National Infrastructure Protection Center | Justice (FBI) | Office of Operations Coordination Office of Infrastructure Protection |

| Energy Security and Assurance Program | Energy | Office of Infrastructure Protection |

| U.S. Coast Guard | Transportation | U.S. Coast Guard |

| U.S. Secret Service | Treasury | U.S. Secret Service |

According to political scientist Peter Andreas, the creation of DHS constituted the most significant government reorganization since the Cold War[8] and the most substantial reorganization of federal agencies since the National Security Act of 1947 (which had placed the different military departments under a secretary of defense and created the National Security Council and Central Intelligence Agency). Creation of DHS constitutes the most diverse merger ever of federal functions and responsibilities, incorporating 22 government agencies into a single organization.[9] The founding of the DHS marked a change in American thought towards threats. Introducing the term "homeland" centers attention on a population that needs to be protected not only against emergencies such as natural disasters but also against diffuse threats from individuals who are non-native to the United States.[10]

Prior to the signing of the bill, controversy about its adoption was focused on whether the Federal Bureau of Investigation and the Central Intelligence Agency should be incorporated in part or in whole (neither was included). The bill was also controversial for the presence of unrelated "riders", as well as for eliminating certain union-friendly civil service and labor protections for department employees. Without these protections, employees could be expeditiously reassigned or dismissed on grounds of security, incompetence or insubordination, and DHS would not be required to notify their union representatives. The plan stripped 180,000 government employees of their union rights.[11] In 2002, Bush officials argued that the September 11 attacks made the proposed elimination of employee protections imperative.[12]

In an August 5, 2002, speech, President Bush said: "We are fighting ... to secure freedom in the homeland."[13] Prior to the creation of DHS, U.S. Presidents had referred to the U.S. as "the nation" or "the republic" and to its internal policies as "domestic".[14] Also unprecedented was the use, from 2002, of the phrase "the homeland" by White House spokespeople.[14]

Congress ultimately passed the Homeland Security Act of 2002, and President Bush signed the bill into law on November 25, 2002. It was the largest U.S. government reorganization in the 50 years since the United States Department of Defense was created.

Tom Ridge was named secretary on January 24, 2003, and began naming his chief deputies. DHS officially began operations on January 24, 2003, but most of the department's component agencies were not transferred into the new department until March 1.[5]

After establishing the basic structure of DHS and working to integrate its components, Ridge announced his resignation on November 30, 2004, following the re-election of President Bush. Bush initially nominated former New York City Police Department commissioner Bernard Kerik as his successor, but on December 10, Kerik withdrew his nomination, citing personal reasons and saying it "would not be in the best interests" of the country for him to pursue the post.

Changes under Secretary Chertoff

[edit]On January 11, 2005, President Bush nominated federal judge Michael Chertoff to succeed Ridge. Chertoff was confirmed on February 15, 2005, by a vote of 98–0 in the U.S. Senate and was sworn in the same day.[5]

In February 2005, DHS and the Office of Personnel Management issued rules relating to employee pay and discipline for a new personnel system named MaxHR. The Washington Post said that the rules would allow DHS "to override any provision in a union contract by issuing a department-wide directive" and would make it "difficult, if not impossible, for unions to negotiate over arrangements for staffing, deployments, technology and other workplace matters".[12] In August 2005, U.S. District judge Rosemary M. Collyer blocked the plan on the grounds that it did not ensure collective-bargaining rights for DHS employees.[12] A federal appeals court ruled against DHS in 2006; pending a final resolution to the litigation, Congress's fiscal year 2008 appropriations bill for DHS provided no funding for the proposed new personnel system.[12] DHS announced in early 2007 that it was retooling its pay and performance system and retiring the name "MaxHR".[5] In a February 2008 court filing, DHS said that it would no longer pursue the new rules, and that it would abide by the existing civil service labor-management procedures. A federal court issued an order closing the case.[12] Chertoff’s successor, Secretary Janet Napolitano deployed full body scanners to assist the United States Secret Service in 2012.[15]

First Trump administration

[edit]A 2017 memo by Secretary of Homeland Security John F. Kelly directed DHS to disregard "age as a basis for determining when to collect biometrics."[16]

On November 16, 2018, President Donald Trump signed the Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency Act of 2018 into law, which elevated the mission of the former DHS National Protection and Programs Directorate and established the Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency.[17] In fiscal year 2018, DHS was allocated a net discretionary budget of $47.716 billion.[2]

Biden administration

[edit]In 2021, the Department of Justice began carrying out an investigation into white supremacy and extremism in the DHS ranks.[18]

DHS also halted large-scale immigration raids at job sites, saying in October 2021 that the administration was planning "a new enforcement strategy to more effectively target employers who pay substandard wages and engage in exploitative labor practices."[19]

In 2023, the U.S. Customs and Border Patrol began using an app which requires asylum seekers to submit biometric information before they enter the country.

In June 2024, John Boyd, the head of the DHS Office of Biometric Identity Management, announced at a conference that the agency "is looking into ways it might use facial recognition technology to track the identities of migrant children." According to Boyd, the initiative is intended to advance the development of facial recognition algorithms. A former DHS official said that every migrant processing center he visited engaged in biometric identity collection, and that children were not separated out during processing. DHS denied collecting the biometric data of children under 14.[16]

Function

[edit]Whereas the Department of Defense is charged with military actions abroad, the Department of Homeland Security works in the civilian sphere to protect the United States within, at, and outside its borders. Its stated goal is to prepare for, prevent, and respond to domestic emergencies, particularly terrorism.[20] On March 1, 2003, the DHS absorbed the U.S. Customs Service and Immigration and Naturalization Service (INS) and assumed its duties. In doing so, it divided the enforcement and services functions into two separate and new agencies: Immigration and Customs Enforcement and Citizenship and Immigration Services. The investigative divisions and intelligence gathering units of the INS and Customs Service were merged forming Homeland Security Investigations, the primary investigative arm of DHS. Additionally, the border enforcement functions of the INS, including the U.S. Border Patrol, the U.S. Customs Service, and the Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service were consolidated into a new agency under DHS: U.S. Customs and Border Protection. The Federal Protective Service falls under the Management Directorate.[21]

Organizational structure

[edit]

The Department of Homeland Security is headed by the secretary of homeland security with the assistance of the deputy secretary. DHS contains operational components, executing specific missions under the purview of the DHS; support components, supporting the mission of the DHS and operational components; and components in the Office of the Secretary, supporting department leadership, DHS components, and the secretary by overseeing and establishing policy.[22]

U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services

[edit]United States Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS) oversees lawful immigration into the United States.[23] Note that Passports for U.S. citizens are issued by the U.S. Department of State, not the Department of Homeland Security.

Executives

[edit]- Director, Joseph B. Edlow[24]

- Deputy Director, Angelica Alfonso-Royals[25]

Subordinate components

[edit]- Office of Performance and Quality

- Office of Investigations

- Office of Privacy

- Office of Administrative Appeals

- Immigration Records and Identity Services Directorate

- Field Operations Directorate

- External Affairs Directorate

- Fraud Detection and National Security Directorate

- Management Directorate

- Service Center Operations Directorate

- Asylum and International Operations Directorate

U.S. Coast Guard

[edit]The United States Coast Guard (USCG) is the maritime security, search and rescue, and law enforcement service branch of the U.S. Armed Forces.[26] It is under the Department of Homeland Security during times of peace, and under the U.S. Department of the Navy during wartime.[27]

Executives

[edit]- Commandant, Admiral Kevin E. Lunday (Acting)

- Vice Commandant, Vice Admiral Peter W. Gautier (Acting)

Subordinate components

[edit]- Atlantic Area

- Coast Guard Northeast District

- Coast Guard East District

- Coast Guard Southeast District

- Coast Guard Heartland District

- Coast Guard Great Lakes District

- Pacific Area

- Coast Guard Southwest District

- Coast Guard Northwest District

- Coast Guard Oceania District

- Coast Guard Arctic District

U.S. Customs and Border Protection

[edit]United States Customs and Border Protection (CBP) is a law enforcement agency responsible for protecting the U.S. border against illegal entry, illicit activity, and other threats; combatting transnational crime and terrorism that's a threat to the economic and national security of the United States; and facilitating lawful trade and lawful entry into the United States.[28]

Executives

[edit]- Commissioner, Pete R. Flores (acting)

- Deputy Commissioner, John Modlin (acting)

Subordinate components

[edit]- U.S. Border Patrol

- Office of Field Operations

- Air and Marine Operations

- Office of Trade

- Enterprise Services Office

- Operations Support Office

U.S. Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency

[edit]

The United States Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency (CISA) is the leading entity of the U.S. federal government in understanding, managing, and reducing risk to cyber and physical infrastructure across the United States.[29]

Executives

[edit]- Director, Bridget Bean (acting)

- Deputy Director, vacant

Subordinate components

[edit]- Cybersecurity Division

- Infrastructure Security Division

- Emergency Communications Division

- Integrated Operations Division

- Stakeholder Engagement Division

- National Risk Management Center

U.S. Federal Emergency Management Agency

[edit]

The United States Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) invests in, improves, and supports capabilities to respond to, mitigate, protect against, recover from, and to prepare for all hazards that may threaten the security of the United States and its citizens, such as natural disasters.[30]

Executives

[edit]- Administrator, David Richardson (acting)

- Deputy Administrator, MaryAnn Tierney (acting)

Subordinate components

[edit]- Mission Support

- Regional Offices (Regions 1-10)

- Resilience

- Response and Recovery

- U.S. Fire Administration

U.S. Federal Law Enforcement Training Centers

[edit]

The United States Federal Law Enforcement Training Centers (FLETC) provides training services to U.S. law enforcement.[31]

Executives

[edit]- Director, Benjamine C. Huffman

- Deputy Director, Paul E. Baker

- Associate Director for Training Operations, Ariana M. Roddini

Subordinate components

[edit]- Training Management Operations Directorate

- National Capital Region Training Operations Directorate

- Core Training Operations Directorate

- Technical Training Operations Directorate

- Mission and Readiness Support Directorate

U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement

[edit]

United States Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) enforces federal laws governing border control, customs, immigration and trade.[32]

Executives

[edit]- Director, Todd Lyons (acting)

- Deputy Director, Madison Sheahan

Subordinate components

[edit]U.S. Secret Service

[edit]

The United States Secret Service (USSS) is charged with the protection of the President of the United States and other government officials and persons designated by law. It also safeguards U.S. financial infrastructure and fights against counterfeiting.[33]

Executives

[edit]- Director, Sean M. Curran

- Deputy Director, vacant

Subordinate components

[edit]- Uniformed Division

- Office of Protective Operations

- Office of Investigations

U.S. Transportation Security Administration

[edit]

The United States Transportation Security Administration (TSA) protects U.S. transportation systems (e.g. airport security) and ensures freedom of movement for people and commerce.[34] It was created as a result of the September 11 attacks in the United States by the Aviation and Transportation Security Act of 2001.[35]

Executives

[edit]- Administrator, Ha Nguyen McNeil (acting)

- Deputy Administrator, Vacant

Subordinate components

[edit]- Federal Air Marshal Service

- Security Operations

- TSA Investigations

- Operations Support

- Enterprise Support

DHS Management Directorate

[edit]

The Department of Homeland Security Management Directorate (MGMT) manages department finance, appropriations, accounting, budgeting, expenditures, procurement, human resources and personnel, information technology systems, biometric identification services, facilities, property, equipment, other material resources, protection of department personnel, information and resources, performance metrics, and the security of federal infrastructure.[36]

Executives

- Under Secretary, Benjamine C. Huffman (acting)

- Deputy Under Secretary, vacant

Subordinate components

[edit]- Office of the Chief Financial Officer

- Office of the Chief Human Capital Officer

- Office of the Chief Information Officer

- Office of the Chief Procurement Officer

- Office of the Chief Readiness Support Officer

- Office of the Chief Security Officer

- Office of Program Accountability and Risk Management

- Office of Biometric Identity Management

- U.S. Federal Protective Service

DHS Science and Technology Directorate

[edit]

The Department of Homeland Security Science and Technology Directorate (S&T) is the department's research and development arm.[37]

Executives

- Under Secretary, Julie S. Brewer (acting)

- Deputy Under Secretary, Joseph "Jay" F. Martin (acting)

Subordinate components

[edit]- Office of Innovation and Collaboration

- Office of Mission and Capability Support

- Office of Enterprise Services

- Office of Science and Engineering

DHS Countering Weapons of Mass Destruction Office

[edit]

The Department of Homeland Security Countering Weapons of Mass Destruction Office (CWMD) works to prevent chemical, biological, nuclear, and radiological attacks against the United States.[38]

Executives

[edit]- Assistant Secretary, David Richardson

- Principal Deputy Assistant Secretary, Deborah Kramer

Subordinate components

[edit]- BioWatch Program

- Securing the Cities Program

- Mobile Detection Deployment Program

- Training and Exercise Program

- CBRN Intelligence

- National Biosurveillance Integration Center

DHS Office of Intelligence and Analysis

[edit]

The Department of Homeland Security Office of Intelligence & Analysis (I&A) is the department's intelligence arm, and disseminates timely information across the DHS enterprise and to local, state, tribal, territorial, and private sector partners.[39]

Executives

[edit]- Under Secretary, Daniel Tamburello (acting)

- Principal Deputy Under Secretary, Adam Luke (acting)

Subordinate components

[edit]- Counterterrorism Center

- Cyber Intelligence Center

- Nation-State Intelligence Center

- Transborder Security Center

- Current and Emerging Threats Center

- Office of Regional Intelligence

- Homeland Identities, Targeting & Exploitation Center

DHS Office of Homeland Security Situational Awareness

[edit]

The Office of Homeland Security Situational Awareness (OSA) provides operations coordination, information sharing, situational awareness, common operating picture, and executes the Secretary's responsibilities across the homeland security enterprise.[40]

Executives

[edit]- Director, Rear Admiral Christopher J. Tomney

- Deputy Director, Frank DiFalco

Subordinate components

[edit]- National Operations Center

- Integration Division

- Mission Support Division

DHS Office of Health Security

[edit]

The Department of Homeland Security Office of Health Security (OHS) is the principal medical, workforce health and safety, and public health authority for DHS.[41]

Executives

[edit]- Director & Chief Medical Officer, Dr. Herbert Wolfe (acting)

- Deputy Director & Deputy Chief Medical Officer, Dr. Herbert Wolfe

Subordinate components

[edit]- Total Workforce Protection Directorate

- Health, Food & Agriculture Resilience Directorate

- Healthcare Systems & Oversight Directorate

- Health Information Systems & Decision Support

- Regional Operations

DHS Office of Inspector General

[edit]

The Department of Homeland Security Office of Inspector General (OIG) provides independent oversight and promotes excellence, integrity, and accountability within DHS.[42]

Executives

[edit]- Inspector General, Joseph V. Cuffari

- Principal Deputy Inspector General, Glenn Sklar

Subordinate components

[edit]- Office of Audits

- Office of Investigations

- Office of Integrity

- Office of Management

- Office of Innovation

- Office of Inspections and Evaluations

DHS Office of the Secretary

[edit]

The Office of the Secretary of Homeland Security oversees the Department of Homeland Security's execution of its mission to safeguard the nation.[43]

Executives

[edit]- Chief of Staff, vacant/none.

Subordinate components

[edit]- Office for Civil Rights and Civil Liberties

- Climate Change Action Group

- Office of the Executive Secretary

- Family Reunification Task Force

- Office of the General Counsel

- Joint Requirements Council

- Office of Legislative Affairs

- Office of the Military Advisor

- Office of the Immigration Detention Ombudsman

- Office of the Citizenship and Immigration Ombudsman

- Office of Partnership and Engagement

- DHS Privacy Office

- Office of Public Affairs

- Office of Strategy, Policy, and Plans

- Office for State and Local Law Enforcement

- Center for Countering Human Trafficking

- Committee Management Office

- Council on Combating Gender-Based Violence

- Forced Labor Enforcement Task Force

DHS Advisory Panels

[edit]DHS advisory panels and committees provide advice and recommendations on mission-related topics from academic engagement to privacy.[44]

- Homeland Security Academic Partnership Council (HSAPC)

- Artificial Intelligence Safety and Security Board (AISSB)

- Counternarcotics Coordinating Council (CNCC)

- Faith-Based Security Advisory Council (FBSAC)

- Homeland Security Advisory Council (HSAC)

- Data Privacy and Integrity Advisory Committee (DPIAC)

- Tribal Homeland Security Advisory Council (THSAC)

National Terrorism Advisory System

[edit]In 2011, the Department of Homeland Security phased out the old Homeland Security Advisory System, replacing it with a two-level National Terrorism Advisory System. The system has two types of advisories: alerts and bulletins. NTAS bulletins permit the secretary to communicate critical terrorism information that, while not necessarily indicative of a specific threat against the United States, can reach homeland security partners or the public quickly, thereby allowing recipients to implement necessary protective measures. Alerts are issued when there is specific and credible information of a terrorist threat against the United States. Alerts have two levels: elevated and imminent. An elevated alert is issued when there is credible information about an attack but only general information about timing or a target. An Imminent Alert is issued when the threat is very specific and impending in the very near term.[citation needed]

On March 12, 2002, the Homeland Security Advisory System, a color-coded terrorism risk advisory scale, was created as the result of a Presidential Directive to provide a "comprehensive and effective means to disseminate information regarding the risk of terrorist acts to Federal, State, and local authorities and to the American people". Many procedures at government facilities are tied into the alert level; for example a facility may search all entering vehicles when the alert is above a certain level. Since January 2003, it has been administered in coordination with DHS; it has also been the target of frequent jokes and ridicule on the part of the administration's detractors about its ineffectiveness. After resigning, Tom Ridge said he did not always agree with the threat level adjustments pushed by other government agencies.[45]

Seal

[edit]The seal was developed with input from senior DHS leadership, employees, and the U.S. Commission on Fine Arts. The Ad Council – which partners with DHS on its Ready.gov campaign – and the consulting company Landor Associates were responsible for graphic design and maintaining heraldic integrity.

The seal is symbolic of the Department's mission – to prevent attacks and protect Americans – on the land, in the sea and in the air. In the center of the seal, a graphically styled white American eagle appears in a circular blue field. The eagle's outstretched wings break through an inner red ring into an outer white ring that contains the words "U.S. DEPARTMENT OF" in the top half and "HOMELAND SECURITY" in the bottom half in a circular placement. The eagle's wings break through the inner circle into the outer ring to suggest that the Department of Homeland Security will break through traditional bureaucracy and perform government functions differently. In the tradition of the Great Seal of the United States, the eagle's talon on the left holds an olive branch with 13 leaves and 13 seeds while the eagle's talon on the right grasps 13 arrows. Centered on the eagle's breast is a shield divided into three sections containing elements that represent the American homeland – air, land, and sea. The top element, a dark blue sky, contains 22 stars representing the original 22 entities that have come together to form the department. The left shield element contains white mountains behind a green plain underneath a light blue sky. The right shield element contains four wave shapes representing the oceans alternating light and dark blue separated by white lines.

- DHS June 6, 2003[46]

Headquarters

[edit]

Since its inception, the department's temporary headquarters had been in Washington, D.C.'s Nebraska Avenue Complex, a former naval facility. The 38-acre (15 ha) site, across from American University, has 32 buildings comprising 566,000 square feet (52,600 m2) of administrative space.[47] In early 2007, the department submitted a $4.1 billion plan to Congress to consolidate its 60-plus Washington-area offices into a single headquarters complex at the St. Elizabeths Hospital campus in Anacostia, Southeast Washington, D.C.[48]

The move was championed by District of Columbia officials because of the positive economic impact it would have on historically depressed Anacostia. The move was criticized by historic preservationists, who claimed the revitalization plans would destroy dozens of historic buildings on the campus.[49] Community activists criticized the plans because the facility would remain walled off and have little interaction with the surrounding area.[50]

In February 2015 the General Services Administration said that the site would open in 2021.[51] DHS headquarters staff began moving to St. Elizabeths in April 2019 after the completion of the Center Building renovation.[52][53]

Disaster preparedness and response

[edit]Congressional budgeting effects

[edit]During a Senate Homeland Security and Governmental Affairs Committee hearing on the reauthorization of DHS, Deputy Secretary Elaine Duke said there is a weariness and anxiety within DHS about the repeated congressional efforts to agree to a long-term spending plan, which had resulted in several threats to shut down the federal government. "Shutdowns are disruptive", Duke said. She said the "repeated failure on a longtime spending plan resulting in short-term continuing resolutions (CRs) has caused "angst" among the department's 240,000 employees in the weeks leading up to the CRs."[54] The uncertainty about funding hampers DHS's ability to pursue major projects and takes away attention and manpower from important priorities. Seventy percent of DHS employees are considered essential and are not furloughed during government shutdowns.[54]

Ready.gov

[edit]

Soon after formation, the department worked with the Ad Council to launch the Ready Campaign, a national public service advertising (PSA) campaign to educate and empower Americans to prepare for and respond to emergencies including natural and man-made disasters. With pro bono creative support from the Martin Agency of Richmond, Virginia, the campaign website "Ready.gov" and materials were conceived in March 2002 and launched in February 2003, just before the launch of the Iraq War.[55][56][57] One of the first announcements that garnered widespread public attention to this campaign was one by Tom Ridge in which he stated that in the case of a chemical attack, citizens should use duct tape and plastic sheeting to build a homemade bunker, or "sheltering in place" to protect themselves.[58][59] As a result, the sales of duct tape skyrocketed, and DHS was criticized for being too alarmist.[60]

On March 1, 2003, the Federal Emergency Management Agency was absorbed into the DHS and in the fall of 2008 took over coordination of the campaign. The Ready Campaign and its Spanish-language version Listo.gov asks individuals to build an emergency supply kit,[61] make a family emergency plan[62] and be informed about the different types of emergencies that can occur and how to respond.[63] The campaign messages have been promoted through television, radio, print, outdoor and web PSAs,[64] as well as brochures, toll-free phone lines and the English and Spanish language websites Ready.gov and Listo.gov.

The general campaign aims to reach all Americans, but targeted resources are also available via "Ready Business" for small- to medium-sized business and "Ready Kids" for parents and teachers of children ages 8–12. In 2015, the campaign also launched a series of PSAs to help the whole community,[65] people with disabilities and others with access and functional needs prepare for emergencies, which included open captioning, a certified deaf interpreter and audio descriptions for viewers who are blind or have low vision.[66]

National Incident Management System

[edit]On March 1, 2004, the National Incident Management System (NIMS) was created. The stated purpose was to provide a consistent incident management approach for federal, state, local, and tribal governments. Under Homeland Security Presidential Directive-5, all federal departments were required to adopt the NIMS and to use it in their individual domestic incident management and emergency prevention, preparedness, response, recovery, and mitigation program and activities.

National Response Framework

[edit]In December 2005, the National Response Plan (NRP) was created, in an attempt to align federal coordination structures, capabilities, and resources into a unified, all-discipline, and all-hazards approach to domestic incident management. The NRP was built on the template of the NIMS.

On January 22, 2008, the National Response Framework was published in the Federal Register as an updated replacement of the NRP, effective March 22, 2008.

Surge Capacity Force

[edit]The Post-Katrina Emergency Management Reform Act directs the DHS Secretary to designate employees from throughout the department to staff a Surge Capacity Force (SCF). During a declared disaster, the DHS Secretary will determine if SCF support is necessary. The secretary will then authorize FEMA to task and deploy designated personnel from DHS components and other Federal Executive Agencies to respond to extraordinary disasters.[67]

Cyber-security

[edit]The DHS National Cyber Security Division (NCSD) is responsible for the response system, risk management program, and requirements for cyber-security in the U.S. The division is home to US-CERT operations and the National Cyber Alert System.[68][69] The DHS Science and Technology Directorate helps government and private end-users transition to new cyber-security capabilities. This directorate also funds the Cyber Security Research and Development Center, which identifies and prioritizes research and development for NCSD.[69] The center works on the Internet's routing infrastructure (the SPRI program) and Domain Name System (DNSSEC), identity theft and other online criminal activity (ITTC), Internet traffic and networks research (PREDICT datasets and the DETER testbed), Department of Defense and HSARPA exercises (Livewire and Determined Promise), and wireless security in cooperation with Canada.[70]

On October 30, 2009, DHS opened the National Cybersecurity and Communications Integration Center. The center brings together government organizations responsible for protecting computer networks and networked infrastructure.[71]

In January 2017, DHS officially designated state-run election systems as critical infrastructure. The designation made it easier for state and local election officials to get cybersecurity help from the federal government. In October 2017, DHS convened a Government Coordinating Council (GCC) for the Election Infrastructure Subsection with representatives from various state and federal agencies such as the Election Assistance Commission and National Association of Secretaries of State.[72]

Secretaries

[edit]To date there have been eight confirmed secretaries of the Department of Homeland Security:[73]

- Tom Ridge (January 24, 2003 – February 1, 2005)

- Michael Chertoff (February 15, 2005 – January 21, 2009)

- Janet Napolitano (January 20, 2009 – September 6, 2013)

- Jeh Charles Johnson (December 23, 2013 – January 20, 2017)

- John F. Kelly (January 20, 2017 – July 28, 2017)

- Kirstjen M. Nielsen (December 6, 2017 – April 10, 2019)

- Alejandro Mayorkas (February 1, 2021 – January 20, 2025)

- Kristi Noem (January 25, 2025–Present)

Criticism

[edit]Excess, waste, and ineffectiveness

[edit]The department has been dogged by persistent criticism over excessive bureaucracy, waste, ineffectiveness and lack of transparency. Congress estimates that the department has wasted roughly $15 billion in failed contracts (as of September 2008[update]).[74] In 2003, the department came under fire after the media revealed that Laura Callahan, Deputy Chief Information Officer at DHS with responsibilities for sensitive national security databases, had obtained her bachelor, masters, and doctorate computer science degrees through Hamilton University, a diploma mill in a small town in Wyoming.[75] The department was blamed for up to $2 billion of waste and fraud after audits by the Government Accountability Office revealed widespread misuse of government credit cards by DHS employees, with purchases including beer brewing kits, $70,000 of plastic dog booties that were later deemed unusable, boats purchased at double the retail price (many of which later could not be found), and iPods ostensibly for use in "data storage".[76][77][78][79]

A 2015 inspection of IT infrastructure found that the department was running over a hundred computer systems whose owners were unknown, including Secret and Top Secret databases, many with out-of-date security or weak passwords. Basic security reviews were absent, and the department had apparently made deliberate attempts to delay publication of information about the flaws.[80]

Data mining

[edit]On September 5, 2007, the Associated Press reported that the DHS had scrapped an anti-terrorism data mining tool called ADVISE (Analysis, Dissemination, Visualization, Insight and Semantic Enhancement) after the agency's internal inspector general found that pilot testing of the system had been performed using data on real people without required privacy safeguards in place.[81][82] The system, in development at Lawrence Livermore and Pacific Northwest National Laboratory since 2003, has cost the agency $42 million to date. Controversy over the program is not new; in March 2007, the Government Accountability Office stated that "the ADVISE tool could misidentify or erroneously associate an individual with undesirable activity such as fraud, crime or terrorism." Homeland Security's Inspector General later said that ADVISE was poorly planned, time-consuming for analysts to use, and lacked adequate justifications.[83]

Fusion centers

[edit]Fusion centers are terrorism prevention and response centers, many of which were created under a joint project between the Department of Homeland Security and the U.S. Department of Justice's Office of Justice Programs between 2003 and 2007. The fusion centers gather information from government sources as well as their partners in the private sector.[84][85]

They are designed to promote information sharing at the federal level between agencies such as the CIA, FBI, Department of Justice, U.S. military and state and local level government. As of July 2009[update], DHS recognized at least seventy-two fusion centers.[86] Fusion centers may also be affiliated with an Emergency Operations Center that responds in the event of a disaster.

There are a number of documented criticisms of fusion centers, including relative ineffectiveness at counterterrorism activities, the potential to be used for secondary purposes unrelated to counterterrorism, and their links to violations of civil liberties of American citizens and others.[87]

David Rittgers of the Cato Institute notes:

A long line of fusion center and DHS reports labeling broad swaths of the public as a threat to national security. The North Texas Fusion System labeled Muslim lobbyists as a potential threat; a DHS analyst in Wisconsin thought both pro- and anti-abortion activists were worrisome; a Pennsylvania homeland security contractor watched environmental activists, Tea Party groups, and a Second Amendment rally; the Maryland State Police put anti-death penalty and anti-war activists in a federal terrorism database; a fusion center in Missouri thought that all third-party voters and Ron Paul supporters were a threat ...[88]

Mail interception

[edit]In 2006, MSNBC reported that Grant Goodman, "an 81-year-old retired University of Kansas history professor, received a letter from his friend in the Philippines that had been opened and resealed with a strip of dark green tape bearing the words "by Border Protection" and carrying the official Homeland Security seal."[89] The letter was sent by a devout Catholic Filipino woman with no history of supporting Islamic terrorism.[89] A spokesman for U.S. Customs and Border Protection "acknowledged that the agency can, will and does open mail coming to U.S. citizens that originates from a foreign country whenever it's deemed necessary":

All mail originating outside the United States Customs territory that is to be delivered inside the U.S. Customs territory is subject to Customs examination," says the CBP Web site. That includes personal correspondence. "All mail means 'all mail,'" said John Mohan, a CBP spokesman, emphasizing the point.[89]

The department declined to outline what criteria are used to determine when a piece of personal correspondence should be opened or to say how often or in what volume Customs might be opening mail.[89]

Goodman's story provoked outrage in the blogosphere,[90] as well as in the more established media. Reacting to the incident, Mother Jones remarked "unlike other prying government agencies, Homeland Security wants you to know it is watching you."[91] CNN observed "on the heels of the NSA wiretapping controversy, Goodman's letter raises more concern over the balance between privacy and security."[92]

Employee morale

[edit]In July 2006, the Office of Personnel Management conducted a survey of federal employees in all 36 federal agencies on job satisfaction and how they felt their respective agency was headed. DHS was last or near to last in every category including;

- 33rd on the talent management index

- 35th on the leadership and knowledge management index

- 36th on the job satisfaction index

- 36th on the results-oriented performance culture index

The low scores were attributed to concerns about basic supervision, management and leadership within the agency. Examples from the survey reveal most concerns are about promotion and pay increase based on merit, dealing with poor performance, rewarding creativity and innovation, leadership generating high levels of motivation in the workforce, recognition for doing a good job, lack of satisfaction with various component policies and procedures and lack of information about what is going on with the organization.[93][94]

DHS is the only large federal agency to score below 50% in overall survey rankings. It was last of large federal agencies in 2014 with 44.0% and fell even lower in 2015 at 43.1%, again last place.[95] DHS continued to rank at the bottom in 2019, prompting congressional inquiries into the problem.[96] High work load resulting from chronic staff shortage, particularly in Customs and Border Protection, has contributed to low morale,[97] as have scandals and intense negative public opinion heightened by immigration policies of the Obama administration.[98]

DHS has struggled to retain women, who complain of overt and subtle misogyny.[99]

MIAC report

[edit]In 2009, the Missouri Information Analysis Center (MIAC) made news for targeting supporters of third party candidates (such as Ron Paul), anti-abortion activists, and conspiracy theorists as potential militia members.[100] Anti-war activists and Islamic lobby groups were targeted in Texas, drawing criticism from the American Civil Liberties Union.[101]

According to DHS:[102]

The Privacy Office has identified a number of risks to privacy presented by the fusion center program:

- Justification for fusion centers

- Ambiguous Lines of Authority, Rules, and Oversight

- Participation of the Military and the Private Sector

- Data Mining

- Excessive Secrecy

- Inaccurate or Incomplete Information

- Mission Creep

Freedom of Information Act processing performance

[edit]In the Center for Effective Government analysis of 15 federal agencies which receive the most Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) requests, published in 2015 (using 2012 and 2013 data), the Department of Homeland Security earned a D+ by scoring 69 out of a possible 100 points, i.e. did not earn a satisfactory overall grade. It also had not updated its policies since the 2007 FOIA amendments.[103]

Fourteen Words slogan and "88" reference

[edit]In 2018, the DHS was accused of referencing the white nationalist Fourteen Words slogan in an official document, by using a similar fourteen-worded title, in relation to unlawful immigration and border control:[104]

We Must Secure The Border And Build The Wall To Make America Safe Again.[105]

Although dismissed by the DHS as a coincidence, both the use of "88" in a document and the similarity to the slogan's phrasing ("We must secure the existence of our people and a future for white children"), drew criticism and controversy from several media outlets.[106][107]

Calls for abolition

[edit]While abolishing the DHS has been proposed since 2011,[108] the idea was popularized when Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez suggested abolishing the DHS in light of the abuses against detained migrants by the Immigration and Customs Enforcement and Customs and Border Protection agencies.[109]

In 2020, the DHS was criticized for detaining protesters in Portland, Oregon. It even drew rebuke from the department's first secretary Tom Ridge who said, "It would be a cold day in hell before I would consent to an uninvited, unilateral intervention into one of my cities".[110]

On August 10, 2020, in an opinion article for USA Today by Anthony D. Romero, the ACLU called for the dismantling of DHS over the deployment of federal forces in July 2020 during the Portland protests.[111]

ACLU lawsuit

[edit]In December 2020, ACLU filed a lawsuit against the DHS, U.S. CBP and U.S. ICE, seeking the release of their records of purchasing cellphone location data. ACLU alleges that this data was used to track U.S. citizens and immigrants and is seeking to discover the full extent of the alleged surveillance.[112]

Nejwa Ali controversy

[edit]The DHS came under fire from pro-Israel politicians in October 2023 for employing Nejwa Ali, who supported Hamas following its deadly terror attack against Israel. Her social media posts were first reported on by the Daily Wire and the Washington Examiner reported on Ali being placed on administrative leave.[113]

Surveillance

[edit]ICE

[edit]American Dragnet, a report, from the Center on Privacy and Technology documents the scope of ICE's surveillance capabilities. The report found that ICE has access to the driver’s license data of 3 in 4 adults, could locate 3 in 4 adults through their utility records and tracks the movements of drivers in cities home to 3 in 4 adults.[114][115] The report also claimed "the agency spent approximately $2.8 billion between 2008 and 2021 on new surveillance, data collection and data-sharing initiatives".[116][117] ICE has also used data brokers to circumvent laws restricting government bodies sharing information with ICE.[118][119][120] ICE has reportedly been a customer of Paragon Solutions and confirmed its use of Clearview AI.[121][122][123][124]

The Second Trump administration reportedly worked to obtain and centralize data on Americans as outlined in Executive Order 14243 relying heavily on products from Palantir Technologies.[125] This data has been desired to support expanded deportation efforts carried out by DHS. The administration has sought data from the IRS,[126][127] Medicaid[128] and Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program.[129][130]

Office of Intelligence and Analysis

[edit]The office of intelligence and analysis (I&A) has a history of problematic surveillance.[131][132][133] In 2020, the I&A authorized "collecting and reporting on various activities in the context of elevated threats targeting monuments, memorials, and statues".[134][135] The office surveilled protestors at the George Floyd protests in Portland, Oregon[136][137] In September 2023, Congress considered revoking some of the agency’s collection authorities over concerns about overreach.[138] According to Politico, "a key theme that emerges from internal documents is that in recent years, many people working at I&A have said they fear they are breaking the law".[139] In 2025, sexual orientation and gender identity were removed from I&A's list of characteristics that "personnel are prohibited from engaging in intelligence activities based solely on".[140]

See also

[edit]- Container Security Initiative

- E-Verify

- Electronic System for Travel Authorization

- Emergency Management Institute

- History of homeland security in the United States

- Homeland Security USA

- Homeland security grant

- Home Office, equivalent department in the United Kingdom

- List of state departments of homeland security

- National Biodefense Analysis and Countermeasures Center (NBACC), Ft Detrick, MD

- National Interoperability Field Operations Guide

- National Strategy for Homeland Security

- Project Hostile Intent

- Public Safety Canada, equivalent department in Canada

- Shadow Wolves

- Terrorism in the United States

- United States visas

References

[edit]- ^ a b "About DHS". Homeland Security. June 29, 2016.

- ^ a b "DHS FY 2024 Budget in Brief (BIB)" (PDF). Homeland Security. p. 4. Retrieved May 4, 2025.

- ^ "Our Mission". Homeland Security. June 27, 2012.

- ^ "Department of Homeland Security Executive Staffing Project". National Academy of Public Administration. Archived from the original on March 10, 2010. Retrieved May 31, 2011.

- ^ a b c d e "National Strategy For Homeland Security" (PDF). DHS. Archived from the original (PDF) on November 14, 2007. Retrieved October 31, 2007.

- ^ "EPIC Fact Sheet on OHS". www.epic.org. Retrieved November 13, 2020.

- ^ "Who Joined DHS". Department of Homeland Security. July 27, 2012. Retrieved May 27, 2021.

- ^ [Peter Andreas: Redrawing the line 2003:92], additional text.

- ^ Perl, Raphael (2004). "The Department of Homeland Security: Background and Challenges", Terrorism—reducing Vulnerabilities and Improving Responses, Committee on Counterterrorism Challenges for Russia and the United States, Office for Central Europe and Eurasia Development, Security, and Cooperation Policy and Global Affairs, in Cooperation with the Russian Academy of Sciences, page 176. National Academies Press. ISBN 0-309-08971-9.

- ^ Gessen, Masha (July 25, 2020). "Homeland Security Was Destined to Become a Secret Police Force". The New Yorker. Retrieved July 26, 2020.

- ^ Chomsky, Noam (2005). Imperial Ambitions, page 199. Metropolitan Books. ISBN 0-8050-7967-X.

- ^ a b c d e Stephen Barr. "DHS Withdraws Bid to Curb Union Rights", The Washington Post page D01, February 20, 2008. Retrieved on August 20, 2008.

- ^ Bovard, James. "Moral high ground not won on battlefield", USA Today, October 8, 2008. Retrieved on August 19, 2008.

- ^ a b Wolf, Naomi (2007). The End of America, page 27. Chelsea Green Publishing. ISBN 978-1-933392-79-0.

- ^ "Freedom of Information Act Request and Request for Expedited Processing" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on December 3, 2021.

- ^ a b Guo, Eileen (August 14, 2024). "The US wants to use facial recognition to identify migrant children as they age". MIT Technology Review. Retrieved August 17, 2024.

- ^ "Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency". DHS.gov. November 20, 2018. Retrieved November 24, 2018.

- ^ Kanno-Youngs, Zolan (April 26, 2021). "D.H.S. will review how it identifies and addresses extremism and white supremacy in its ranks". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved April 27, 2021.

- ^ Miroff, Nick (October 12, 2021). "Biden administration orders halt to ICE raids at worksites". The Washington Post. Retrieved March 19, 2022.

- ^ "One Team, One Mission, Securing Our Homeland - U.S. Department of Homeland Security Strategic Plan Fiscal Years 2008–2013" (PDF). DHS. Archived from the original (PDF) on February 21, 2012. Retrieved July 29, 2016.

- ^ "Who We Are". DHS.gov. Retrieved February 20, 2025.

- ^ "Organization | Homeland Security". www.dhs.gov. Retrieved December 4, 2024.

- ^ "What We Do | USCIS". www.uscis.gov. February 27, 2020. Retrieved December 4, 2024.

- ^ "Joseph B. Edlow, Director, U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services | USCIS". www.uscis.gov. July 18, 2025.

- ^ "Leadership | USCIS". www.uscis.gov. September 10, 2025.

- ^ "About U.S. Coast Guard Missions". www.uscg.mil. Retrieved December 4, 2024.

- ^ "Our Forces". U.S. Department of Defense. Retrieved December 5, 2024.

- ^ "About CBP | U.S. Customs and Border Protection". www.cbp.gov. Retrieved December 4, 2024.

- ^ "About CISA | CISA". www.cisa.gov. Retrieved December 4, 2024.

- ^ "About Us | FEMA.gov". www.fema.gov. November 14, 2024. Retrieved December 4, 2024.

- ^ "Our Mission and Core Values | Federal Law Enforcement Training Centers". www.fletc.gov. Retrieved December 4, 2024.

- ^ "ICE's Mission | ICE". www.ice.gov. May 8, 2024. Retrieved December 4, 2024.

- ^ "About Us". www.secretservice.gov. Retrieved December 4, 2024.

- ^ "Mission | Transportation Security Administration". www.tsa.gov. Retrieved December 4, 2024.

- ^ "TSA History | Transportation Security Administration". www.tsa.gov. Retrieved December 4, 2024.

- ^ "Management Directorate | Homeland Security". www.dhs.gov. Retrieved December 4, 2024.

- ^ "About S&T | Homeland Security". www.dhs.gov. Retrieved December 4, 2024.

- ^ "About CWMD | Homeland Security". www.dhs.gov. Retrieved December 4, 2024.

- ^ "Office of Intelligence and Analysis | Homeland Security". www.dhs.gov. Retrieved December 4, 2024.

- ^ "Office of Homeland Security Situational Awareness | Homeland Security". www.dhs.gov. Retrieved December 4, 2024.

- ^ "Office of Health Security | Homeland Security". www.dhs.gov. Retrieved December 4, 2024.

- ^ "About Us | Office of Inspector General". www.oig.dhs.gov. Retrieved December 5, 2024.

- ^ "Office of the Secretary | Homeland Security". www.dhs.gov. Retrieved December 5, 2024.

- ^ "Advisory Panels & Committees | Homeland Security". www.dhs.gov. Retrieved December 5, 2024.

- ^ "Remarks by Governor Ridge Announcing Homeland Security Advisory System". Retrieved May 5, 2017.

- ^ "Fact Sheet: Department of Homeland Security Seal", DHS press release, June 19, 2003. DHS website Archived October 24, 2006, at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved on August 26, 2008.

- ^ "Statement of Secretary Tom Ridge". DHS. Retrieved October 31, 2007.

- ^ Losey, Stephen (March 19, 2007). "Homeland Security plans move to hospital compound". Federal Times. Archived from the original on January 2, 2013. Retrieved October 31, 2007.

- ^ "Most Endangered Places". 2/2009. National Trust. Retrieved February 4, 2009.

- ^ Holley, Joel (June 17, 2007). "Tussle Over St. Elizabeths". The Washington Post. p. C01. Retrieved October 31, 2007.

- ^ "DHS headquarters consolidation has a new tentative plan at St. Elizabeths". July 10, 2020.

- ^ Heckman, Jory (June 21, 2019). "DHS St. Elizabeths campus gains 'center of gravity' with new headquarters". Federal News Network. Retrieved August 9, 2019.

- ^ Sernovitz, Daniel J. (July 9, 2019). "DHS reveals more detail on what's to come for St. Elizabeths West". Washington Business Journal. Retrieved August 9, 2019.

- ^ a b Roberts, Ed (February 7, 2018). "Spending stalemate has costs at Department of Homeland Security – Homeland Preparedness News". Homeland Preparedness News. Retrieved February 27, 2018.

- ^ Forbes, Daniel (May 28, 2004). "$226 Million in Govt Ads Helped Pave the Way for War". Antiwar.com. Retrieved October 31, 2007.

- ^ "Homeland Security: Ready.Gov". Outdoor Advertising Association of America. Archived from the original on October 17, 2007. Retrieved October 31, 2007.

- ^ "CNN Live at daybreak". Aired February 20, 2003. CNN. Retrieved October 31, 2007.

- ^ "Homeland Security Frequently Asked Questions". ready.gov. Archived from the original on November 6, 2007. Retrieved October 31, 2007.

- ^ "Clean Air". ready.gov. Archived from the original on October 17, 2007. Retrieved October 31, 2007.

- ^ "Are You Ready.gov?". February 21, 2003. lies.com. Retrieved October 31, 2007.

- ^ "Build A Kit | Ready.gov". www.ready.gov. Archived from the original on November 1, 2016. Retrieved October 31, 2016.

- ^ "Make A Plan | Ready.gov". www.ready.gov. Retrieved October 31, 2016.

- ^ "About the Ready Campaign | Ready.gov". www.ready.gov. Retrieved October 31, 2016.

- ^ "Emergency Preparedness". AdCouncil. Archived from the original on October 25, 2016. Retrieved October 31, 2016.

- ^ Newswire, MultiVu - PR. "FEMA, Ad Council Launch New PSA Focused on People with Disabilities Preparing for Emergencies". Multivu. Retrieved October 31, 2016.

- ^ "Individuals with Disabilities and Others with Access and Functional Needs | Ready.gov". ready.gov. Retrieved October 31, 2016.

- ^ "Surge Capacity Force – Homeland Security". January 30, 2013. Retrieved April 18, 2019.

- ^ "National Cyber Security Division". U.S. Department of Homeland Security. Retrieved June 14, 2008.

- ^ a b "FAQ: Cyber Security R&D Center". U.S. Department of Homeland Security S&T Directorate. Retrieved June 14, 2008.

- ^ "Ongoing Research and Development". U.S. Department of Homeland Security S&T Directorate. Retrieved June 14, 2008.

- ^ AFP-JiJi, "U.S. boots up cybersecurity center", October 31, 2009.

- ^ Murtha, Alex (October 17, 2017). "DHS, partners convene for government council on protecting election infrastructure". Homeland Preparedness News. Retrieved December 20, 2017.

- ^ "Secretaries of Homeland Security | Homeland Security". www.dhs.gov.

- ^ Hedgpeth, Dana (September 17, 2008). "Congress Says DHS Oversaw $15 Billion in Failed Contracts". The Washington Post. Retrieved November 17, 2008.

- ^ Diplomas For Sale – Retrieved August 5, 2015

- ^ Lipton, Eric (July 19, 2006). "Homeland Security Department Is Accused of Credit Card Misuse". The New York Times. Retrieved October 31, 2007.

- ^ Jakes Jordan, Lara (July 19, 2006). "Credit Card Fraud at DHS". Homeland Security Weekly. Archived from the original on October 17, 2007. Retrieved October 31, 2007.

- ^ "Government's Katrina credit cards criticized". Associated Press. September 15, 2005. Retrieved October 31, 2007.

- ^ Hedgpeth, Dana (September 17, 2008). "Congress says DHS oversaw $15 billion in failed contracts". The Washington Post. Retrieved September 17, 2008.

- ^ McCarthy, Kieren (November 20, 2015). "Who's running dozens of top-secret unpatched databases? The Dept of Homeland Security". The Register. Retrieved January 3, 2016.

- ^ "ADVISE Could Support Intelligence Analysis More Effectively" (PDF). pdf file. DHS. Retrieved October 31, 2007.

- ^ Singel, Ryan (March 20, 2007). "Homeland Data Tool Needs Privacy Help, Report Says". Wired. Retrieved October 31, 2007.

- ^ Sniffen, Michael J. (September 5, 2007). "DHS Ends Criticized Data-Mining Program". The Washington Post. Associated Press. Retrieved October 31, 2007.

- ^ Monahan, T. 2009. The Murky World of 'Fusion Centres'. Criminal Justice Matters 75 (1): 20-21.

- ^ "Smashing Intelligence Stovepipes | Security Management". Archived from the original on April 29, 2011. Retrieved February 2, 2011.

- ^ Report on Fusion Centers July 29, 2009, Democracy Now

- ^ Monahan, T. and Palmer, N.A. 2009. The Emerging Politics of DHS Fusion Centers. Security Dialogue 40 (6): 617–636.

- ^ Rittgers, David (February 2, 2011) We're All Terrorists Now Archived April 15, 2011, at the Wayback Machine, Cato Institute

- ^ a b c d Meeks, Brock (January 6, 2006) Homeland Security opening private mail, NBC News

- ^ Cole, John (January 9, 2006) Your Mail- Free for Government Inspection, Balloon Juice

- ^ Dees, Diane (January 9, 2006) Department of Homeland Security opens Kansas professor's mail, Mother Jones

- ^ Transcript Archived July 8, 2011, at the Wayback Machine from The Situation Room (January 12, 2006)

- ^ "Homeland Security employees rank last in job satisfaction survey". ABC Inc., WLS-TV Chicago. February 8, 2007. Archived from the original on March 18, 2007. Retrieved October 31, 2007.

- ^ Conroy, Bill (January 31, 2007). "DHS memo reveals agency personnel are treated like "human capital"". Narco News. Archived from the original on October 17, 2007. Retrieved October 31, 2007.

- ^ "Best Places to Work Agency Rankings". Partnership for Public Service. Archived from the original on February 23, 2016. Retrieved February 22, 2016.

- ^ Neal, Jeff (January 16, 2020). "Layers of problems drive morale issues at DHS". Federal News Network. Retrieved May 23, 2020.

- ^ Miroff, Nick (January 19, 2018). "U.S. customs agency is so short-staffed, it's sending officers from airports to the Mexican border". The Washington Post. Retrieved May 23, 2020.

- ^ Fernandez, Manny; Jordan, Miriam; Kanno-Youngs, Zolan; Dickerson, Caitlin; Brinson, Kendrick (September 15, 2019). "'People Actively Hate Us': Inside the Border Patrol's Morale Crisis". The New York Times. Retrieved May 23, 2020.

- ^ "Federal law enforcement has a woman problem". Politico. November 14, 2017.

- ^ "'Fusion Centers' Expand Criteria to Identify Militia Members". Fox News. March 23, 2009. Archived from the original on August 3, 2009. Retrieved December 19, 2018.

- ^ "Fusion Centers Under Fire in Texas and New Mexico | Security Management". Archived from the original on April 8, 2012. Retrieved July 13, 2012.

- ^ Privacy Impact Assessment for the Department of Homeland Security State, Local, and Regional Fusion Center Initiative December 11, 2008

- ^ Making the Grade: Access to Information Scorecard 2015 Archived March 13, 2016, at the Wayback Machine March 2015, 80 pages, Center for Effective Government, retrieved March 21, 2016

- ^ "Did Trump administration send a coded signal to neo-Nazis? Maybe not — but is that reassuring?". Salon. July 6, 2018.

- ^ "We Must Secure The Border And Build The Wall To Make America Safe Again". DHS. February 15, 2018.

- ^ "Homeland Security Officials Say Claims That Statement Mimics A White Supremacist Slogan Are Merely Conspiracy Theories". BuzzFeed. June 29, 2018.

- ^ "Are '14' And '88' Nazi Dog Whistles In Border Security Document – Or Just Numbers?". The Forward. June 28, 2018.

- ^ Rittgers, David (September 8, 2011). "Abolish the Department of Homeland Security". Cato Institute. Retrieved July 15, 2019.

- ^ Iati, Marisa (July 11, 2019). "Ocasio-Cortez wants to ax Homeland Security. Some conservatives didn't want it to begin with". The Washington Post. Retrieved July 11, 2019.

- ^ "Ex-DHS Secretary Tom Ridge: 'It would be a cold day in hell' before 'personal militia' would be welcomed uninvited in Pa". triblive.com. July 21, 2020.

- ^ Romero, Anthony D. (August 10, 2020). "Dismantle the Department of Homeland Security. Its tactics are fearsome: ACLU director". USA TODAY. Retrieved August 10, 2020.

- ^ Zakrzewski, Cat (December 2, 2020). "The Technology 202: ACLU sues DHS over purchase of cellphone location data used to track immigrants". The Washington Post. Retrieved December 2, 2020.

- ^ Kaminsky, Gabe (October 18, 2023). "Biden DHS official placed on leave after pro-Palestinian ties revealed". The Washington Examiner. pp. 2–3. Retrieved October 24, 2023.

- ^ "American Dragnet: Data-Driven Deportation in the 21st Century". law.georgetown.edu.

- ^ Harwell, Drew (July 7, 2019). "FBI, ICE find state driver's license photos are a gold mine for facial-recognition searches". The Washington Post. ISSN 0190-8286. Archived from the original on April 22, 2021.

- ^ "American Dragnet | Data-Driven Deportation in the 21st Century". American Dragnet. Center on Privacy and Technology. Archived from the original on February 23, 2025.

- ^ Carcamo, Cindy (May 10, 2022). "Immigration officials created network that can spy on majority of Americans, report says". Los Angeles Times.

- ^ Faife, Corin (May 10, 2022). "ICE uses data brokers to bypass surveillance restrictions, report finds". The Verge.

- ^ Hodge, Rae (April 22, 2022). "ICE Uses Private Data Brokers to Circumvent Immigrant Sanctuary Laws, Report Says". CNET.

- ^ Walter-Johnson, Shreya Tewari, Fikayo (July 18, 2022). "New Records Detail DHS Purchase and Use of Vast Quantities of Cell Phone Location Data | ACLU". American Civil Liberties Union.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Reichert, Corinne (March 2, 2020). "Clearview AI facial recognition customers reportedly include DOJ, FBI, ICE, Macy's". CNET.

In an emailed statement, ICE confirmed its use of Clearview AI, saying it's primarily for agents with Homeland Security Investigations who are involved in child exploitation and cybercrime cases.

- ^ "Contract to Clearview AI, Inc". usaspending.gov.

- ^ "Pressley, Jayapal, Markey, Merkley Urge Federal Agencies to End Use of Clearview AI Facial Recognition Technology". Ayanna Pressley. February 9, 2022.

- ^ Cox, Joseph (September 8, 2025). "ICE Spends Millions on Clearview AI Facial Recognition to Find People 'Assaulting' Officers". 404 Media. Archived from the original on September 9, 2025.

- ^ Frenkel, Sheera; Krolik, Aaron (May 30, 2025). "Trump Taps Palantir to Compile Data on Americans". The New York Times. Archived from the original on July 8, 2025.

- ^ "DHS Lands Legal Victory in IRS Data Sharing Case: "Win for the American People and for Common Sense"". dhs.gov.

- ^ Rose, Joel (April 8, 2025). "The IRS finalizes a deal to share tax information with immigration authorities". NPR.

- ^ KINDY, KIMBERLY; SEITZ, AMANDA (July 17, 2025). "Trump administration hands over Medicaid recipients' personal data, including addresses, to ICE". AP News.

- ^ "States file lawsuit against Trump administration over efforts to collect SNAP recipients' data". AP News. July 28, 2025.

- ^ Badger, Emily; Frenkel, Sheera (April 9, 2025). "Trump Wants to Merge Government Data. Here Are 314 Things It Might Know About You". Archived from the original on June 6, 2025.

- ^ Reynolds, Spencer (January 17, 2024). "Recent Reforms Won't Fix DHS Intelligence Abuses". Brennan Center.

- ^ Levinson-Waldman, Rachel; Panduranga, Harsha; Patel, Faiza (July 30, 2024). "Social Media Surveillance by the U.S. Government | Brennan Center for Justice". Brennan Center.

- ^ Reynolds, Spencer (March 5, 2025). "How DHS Laid the Groundwork for More Intelligence Abuse". Brennan Center.

- ^ Vladeck, Steve; Wittes, Benjamin (January 18, 2023). "DHS Authorizes Domestic Surveillance to Protect Statues and Monuments". Lawfare.

- ^ Harris, Shane (July 20, 2020). "DHS authorizes personnel to collect information on protesters it says threaten monuments". The Washington Post. ISSN 0190-8286.

- ^ Selsky, Andrew (October 28, 2022). "New report shows Department of Homeland Security gathered intel on Portland Black Lives Matter protestors". PBS News.

- ^ "Wyden Releases New Details About Surveillance and Interrogation of Portland Demonstrators by Department of Homeland Security Agents". wyden.senate.gov. October 27, 2022. Archived from the original on November 18, 2022.

- ^ Sullivan, Eileen (January 18, 2025). "Little-Known Intelligence Agency Outlines Limits on Spying". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331.

- ^ Woodruff Swan, Betsy (March 6, 2023). "DHS has a program gathering domestic intelligence — and virtually no one knows about it". Politico.

- ^ Adamczeski, Ryan (February 26, 2025). "DHS quietly eliminates ban on surveillance based on sexual orientation and gender identity". advocate.com.

Further reading

[edit]- Bullock, Jane, George Haddow, and Damon P. Coppola. Introduction to homeland security: Principles of all-hazards risk management (Butterworth-Heinemann, 2011)

- Ramsay, James D. et al. Theoretical Foundations of Homeland Security: Strategies, Operations, and Structures (Routledge, 2021)

- Sylves, Richard T. Disaster policy and politics: Emergency management and homeland security (CQ press, 2019).

- MacMartin, Steven M. Et al. "The History and Evolution of Homeland Security in the United States" ISBN 978-1032756622 (CRC Press 2025)

Primary sources

[edit]- United States. Office of Homeland Security. National strategy for homeland security (DIANE Publishing, 2002) online.

External links

[edit] Media related to United States Department of Homeland Security at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to United States Department of Homeland Security at Wikimedia Commons Works on the topic United States Department of Homeland Security at Wikisource

Works on the topic United States Department of Homeland Security at Wikisource- Official website

- Department of Homeland Security on USAspending.gov

- DHS in the Federal Register

United States Department of Homeland Security

View on GrokipediaHistory

Formation Following 9/11 Attacks

The September 11, 2001, terrorist attacks by al-Qaeda operatives, resulting in 2,977 deaths across New York City, Washington, D.C., and Pennsylvania, revealed critical deficiencies in U.S. federal coordination for counterterrorism, including fragmented intelligence analysis and inadequate integration of domestic security functions across agencies.[9] These failures, compounded by pre-attack warnings that were not effectively shared or acted upon, underscored the need for a centralized structure to prevent future mass-casualty events originating from abroad or within U.S. borders.[2] In direct response, President George W. Bush proposed establishing a new cabinet-level Department of Homeland Security (DHS) to unify disparate homeland protection efforts, emphasizing prevention of terrorist acts as the federal government's paramount responsibility.[10] The proposal aimed to address causal gaps in threat detection and response by consolidating responsibilities previously scattered across multiple departments, such as border enforcement, cybersecurity, and emergency management, into a single entity better equipped for rapid decision-making and resource allocation.[1] Congress passed the Homeland Security Act of 2002 (H.R. 5005) after debates on organizational scope and oversight mechanisms, with the House approving it 295–132 on November 13, 2002, followed by Senate concurrence.[11] President Bush signed the legislation into law on November 25, 2002, creating DHS as the third-largest cabinet department and marking the most significant federal reorganization since the National Security Act of 1947 established the Department of Defense.[12] The Act transferred all or portions of 22 existing agencies to DHS, including components from the Departments of Transportation, Justice, Treasury, and Agriculture, to streamline operations without duplicating military-focused national security roles.[9] DHS officially commenced operations on March 1, 2003, under initial leadership tasked with integrating these entities amid logistical challenges like employee transitions and IT system mergers.[13] This formation prioritized empirical enhancements in risk assessment and inter-agency communication, driven by the imperative to mitigate vulnerabilities exposed on 9/11 rather than reactive measures alone, though early implementation faced criticism for potential over-centralization of power.[2]Initial Agency Incorporations and Structure

The Homeland Security Act of 2002, enacted as Public Law 107-296 and signed by President George W. Bush on November 25, 2002, authorized the creation of the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) by consolidating functions from all or part of 22 existing federal departments and agencies to centralize efforts against terrorism and enhance national security coordination.[2] [11] DHS became operational on January 24, 2003, with full integration of transferred entities effective March 1, 2003, absorbing approximately 170,000 employees from predecessor organizations.[14] [2] Major agencies and offices transferred included the U.S. Customs Service (from the Department of the Treasury, responsible for customs enforcement and trade facilitation), the Immigration and Naturalization Service (from the Department of Justice, handling immigration adjudication and enforcement), the Transportation Security Administration (from the Department of Transportation, focused on aviation security), the Federal Emergency Management Agency (independent agency for disaster response), the U.S. Coast Guard (from the Department of Transportation, for maritime security and law enforcement), and the U.S. Secret Service (from the Department of the Treasury, for protective and financial crime investigations).[15] Additional transfers encompassed the Federal Protective Service (from the General Services Administration, for federal facility security), the Federal Law Enforcement Training Center (from the Treasury, for law enforcement training), and elements of the Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service (from the Department of Agriculture, for agroterrorism prevention), among others such as the Office for Domestic Preparedness and the National Domestic Preparedness Office.[2] These incorporations aimed to eliminate redundancies in border control, emergency management, and intelligence analysis identified post-September 11, 2001, though critics noted potential disruptions from rapid consolidation without sufficient integration planning.[16] The initial structure, as outlined in the March 2003 organizational chart, placed the Secretary and Deputy Secretary at the apex, with five under secretaries leading directorates tailored to core missions: the Directorate of Border and Transportation Security Directorate (integrating customs, immigration enforcement, and TSA functions into bureaus like Customs and Border Protection and Immigration and Customs Enforcement), the Emergency Preparedness and Response Directorate (primarily FEMA for disaster mitigation), the Information Analysis and Infrastructure Protection Directorate (for threat assessment and critical infrastructure safeguards), the Science and Technology Directorate (for R&D in detection and response technologies), and the Management Directorate (for administrative support).[17] [18] Legacy components such as the Coast Guard and Secret Service reported directly to the Secretary rather than directorates, preserving operational autonomy while aligning under unified leadership.[15] This framework, directed by first Secretary Tom Ridge, emphasized horizontal integration across silos but faced early challenges in unifying disparate cultures and IT systems from the transferred entities.[16]Reorganizations and Reforms (2006-2016)