Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

F-number

View on Wikipedia

An f-number is a measure of the light-gathering ability of an optical system such as a camera lens. It is defined as the ratio of the system's focal length to the diameter of the entrance pupil ("clear aperture").[1][2][3] The f-number is also known as the focal ratio, f-ratio, or f-stop, and it is key in determining the depth of field, diffraction, and exposure of a photograph.[4] The f-number is dimensionless and is usually expressed using a lower-case hooked f with the format f/N, where N is the f-number.

The f-number is also known as the inverse relative aperture, because it is the inverse of the relative aperture, defined as the aperture diameter divided by the focal length.[5] A lower f-number means a larger relative aperture and more light entering the system, while a higher f-number means a smaller relative aperture and less light entering the system. The f-number is related to the numerical aperture (NA) of the system, which measures the range of angles over which light can enter or exit the system. The numerical aperture takes into account the refractive index of the medium in which the system is working, while the f-number does not.

The f-number is used as an indication of the light-gathering ability of a lens, i.e. the illuminance it delivers to the film or sensor for a given subject luminance. Although this usage is common, it is an approximation that ignores the effects of the focusing distance and the light transmission of the lens. When these effects cannot be ignored, the working f-number or the T-stop is used instead of the f-number.

Notation

[edit]The f-number N is given by:

where f is the focal length, and D is the diameter of the entrance pupil (effective aperture). It is customary to write f-numbers preceded by "f/", which forms a mathematical expression of the entrance pupil's diameter in terms of f and N.[1] For example, if a lens's focal length were 100 mm and its entrance pupil's diameter were 50 mm, the f-number would be 2. This would be expressed as "f/2" in a lens system. The aperture diameter would be equal to f/2.

Camera lenses often include an adjustable diaphragm, which changes the size of the aperture stop and thus the entrance pupil size. This allows the user to vary the f-number as needed. The entrance pupil diameter is not necessarily equal to the aperture stop diameter, because of the magnifying effect of lens elements in front of the aperture.

Ignoring differences in light transmission efficiency, a lens with a greater f-number projects darker images. The brightness of the projected image (illuminance) relative to the brightness of the scene in the lens's field of view (luminance) decreases with the square of the f-number. A 100 mm focal length f/4 lens has an entrance pupil diameter of 25 mm. A 100 mm focal length f/2 lens has an entrance pupil diameter of 50 mm. Since the area is proportional to the square of the pupil diameter,[6] the amount of light admitted by the f/2 lens is four times that of the f/4 lens. To obtain the same photographic exposure, the exposure time must be reduced by a factor of four.

A 200 mm focal length f/4 lens has an entrance pupil diameter of 50 mm. The 200 mm lens's entrance pupil has four times the area of the 100 mm f/4 lens's entrance pupil, and thus collects four times as much light from each object in the lens's field of view. But compared to the 100 mm lens, the 200 mm lens projects an image of each object twice as high and twice as wide, covering four times the area, and so both lenses produce the same illuminance at the focal plane when imaging a scene of a given luminance.

Conventional scales

[edit]

The word stop is sometimes confusing due to its multiple meanings. A stop can be a physical object: an opaque part of an optical system that blocks certain rays. The aperture stop is the aperture setting that limits the brightness of the image by restricting the input pupil size, while a field stop is a stop intended to cut out light that would be outside the desired field of view and might cause flare or other problems if not stopped.

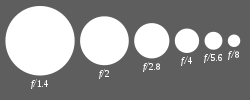

In photography, stops are also a unit used to quantify ratios of light or exposure, with each added stop meaning a factor of two, and each subtracted stop meaning a factor of one-half. The one-stop unit is also known as the EV (exposure value) unit. On a camera, the aperture setting is traditionally adjusted in discrete steps, known as f-stops. Each "stop" is marked with its corresponding f-number, and represents a halving of the light intensity from the previous stop. This corresponds to a decrease of the pupil and aperture diameters by a factor of 1/√2 or about 0.7071, and hence a halving of the area of the pupil.

Most modern lenses use a standard f-stop scale, which is an approximately geometric sequence of numbers that corresponds to the sequence of the powers of the square root of 2: f/1, f/1.4, f/2, f/2.8, f/4, f/5.6, f/8, f/11, f/16, f/22, f/32, f/45, f/64, f/90, f/128, etc. Each element in the sequence is one stop lower than the element to its left, and one stop higher than the element to its right. The values of the ratios are rounded off to these particular conventional numbers, to make them easier to remember and write down. The sequence above is obtained by approximating the following exact geometric sequence:

In the same way as one f-stop corresponds to a factor of two in light intensity, shutter speeds are arranged so that each setting differs in duration by a factor of approximately two from its neighbour. Opening up a lens by one stop allows twice as much light to fall on the film in a given period of time. Therefore, to have the same exposure at this larger aperture as at the previous aperture, the shutter would be opened for half as long (i.e., twice the speed). The film will respond equally to these equal amounts of light, since it has the property of reciprocity. This is less true for extremely long or short exposures, where there is reciprocity failure. Aperture, shutter speed, and film sensitivity are linked: for constant scene brightness, doubling the aperture area (one stop), halving the shutter speed (doubling the time open), or using a film twice as sensitive, has the same effect on the exposed image. For all practical purposes extreme accuracy is not required (mechanical shutter speeds were notoriously inaccurate as wear and lubrication varied, with no effect on exposure). It is not significant that aperture areas and shutter speeds do not vary by a factor of precisely two.

Photographers sometimes express other exposure ratios in terms of 'stops'. Ignoring the f-number markings, the f-stops make a logarithmic scale of exposure intensity. Given this interpretation, one can then think of taking a half-step along this scale, to make an exposure difference of a "half stop".

Fractional stops

[edit]Most twentieth-century cameras had a continuously variable aperture, using an iris diaphragm, with each full stop marked. Click-stopped aperture came into common use in the 1960s; the aperture scale usually had a click stop at every whole and half stop.

On modern cameras, especially when aperture is set on the camera body, f-number is often divided more finely than steps of one stop. Steps of one-third stop (1⁄3 EV) are the most common, since this matches the ISO system of film speeds. Half-stop steps are used on some cameras. Usually the full stops are marked, and the intermediate positions click but are not marked. As an example, the aperture that is one-third stop smaller than f/2.8 is f/3.2, two-thirds smaller is f/3.5, and one whole stop smaller is f/4. The next few f-stops in this sequence are:

To calculate the steps in a full stop (1 EV) one could use

The steps in a half stop (1⁄2 EV) series would be

The steps in a third stop (1⁄3 EV) series would be

As in the earlier DIN and ASA film-speed standards, the ISO speed is defined only in one-third stop increments, and shutter speeds of digital cameras are commonly on the same scale in reciprocal seconds. A portion of the ISO range is the sequence

while shutter speeds in reciprocal seconds have a few conventional differences in their numbers (1⁄15, 1⁄30, and 1⁄60 second instead of 1⁄16, 1⁄32, and 1⁄64).

In practice the maximum aperture of a lens is often not an integral power of √2 (i.e., √2 to the power of a whole number), in which case it is usually a half or third stop above or below an integral power of √2.

Modern electronically controlled interchangeable lenses, such as those used for SLR cameras, have f-stops specified internally in 1⁄8-stop increments, so the cameras' 1⁄3-stop settings are approximated by the nearest 1⁄8-stop setting in the lens.[citation needed]

Standard full-stop f-number scale

[edit]Including aperture value AV:

Conventional and calculated f-numbers, full-stop series:

| AV | −2 | −1 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | 0.5 | 0.7 | 1.0 | 1.4 | 2 | 2.8 | 4 | 5.6 | 8 | 11 | 16 | 22 | 32 | 45 | 64 | 90 | 128 | 180 | 256 |

| calculated | 0.5 | 0.707... | 1.0 | 1.414... | 2.0 | 2.828... | 4.0 | 5.657... | 8.0 | 11.31... | 16.0 | 22.62... | 32.0 | 45.25... | 64.0 | 90.51... | 128.0 | 181.02... | 256.0 |

Typical one-half-stop f-number scale

[edit]| AV | −1 | −1⁄2 | 0 | 1⁄2 | 1 | 1+1⁄2 | 2 | 2+1⁄2 | 3 | 3+1⁄2 | 4 | 4+1⁄2 | 5 | 5+1⁄2 | 6 | 6+1⁄2 | 7 | 7+1⁄2 | 8 | 8+1⁄2 | 9 | 9+1⁄2 | 10 | 10+1⁄2 | 11 | 11+1⁄2 | 12 | 12+1⁄2 | 13 | 13+1⁄2 | 14 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | 0.7 | 0.8 | 1.0 | 1.2 | 1.4 | 1.7 | 2 | 2.4 | 2.8 | 3.3 | 4 | 4.8 | 5.6 | 6.7 | 8 | 9.5 | 11 | 13 | 16 | 19 | 22 | 27 | 32 | 38 | 45 | 54 | 64 | 76 | 90 | 107 | 128 |

Typical one-third-stop f-number scale

[edit]| AV | −1 | −2⁄3 | −1⁄3 | 0 | 1⁄3 | 2⁄3 | 1 | 1+1⁄3 | 1+2⁄3 | 2 | 2+1⁄3 | 2+2⁄3 | 3 | 3+1⁄3 | 3+2⁄3 | 4 | 4+1⁄3 | 4+2⁄3 | 5 | 5+1⁄3 | 5+2⁄3 | 6 | 6+1⁄3 | 6+2⁄3 | 7 | 7+1⁄3 | 7+2⁄3 | 8 | 8+1⁄3 | 8+2⁄3 | 9 | 9+1⁄3 | 9+2⁄3 | 10 | 10+1⁄3 | 10+2⁄3 | 11 | 11+1⁄3 | 11+2⁄3 | 12 | 12+1⁄3 | 12+2⁄3 | 13 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | 0.7 | 0.8 | 0.9 | 1.0 | 1.1 | 1.2 | 1.4 | 1.6 | 1.8 | 2 | 2.2 | 2.5 | 2.8 | 3.2 | 3.5 | 4 | 4.5 | 5.0 | 5.6 | 6.3 | 7.1 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 13 | 14 | 16 | 18 | 20 | 22 | 25 | 29 | 32 | 36 | 40 | 45 | 51 | 57 | 64 | 72 | 80 | 90 |

Sometimes the same number is included on several scales; for example, an aperture of f/1.2 may be used in either a half-stop[7] or a one-third-stop system;[8] sometimes f/1.3 and f/3.2 and other differences are used for the one-third stop scale.[9]

Typical one-quarter-stop f-number scale

[edit]| AV | 0 | 1⁄4 | 1⁄2 | 3⁄4 | 1 | 1+1⁄4 | 1+1⁄2 | 1+3⁄4 | 2 | 2+1⁄4 | 2+1⁄2 | 2+3⁄4 | 3 | 3+1⁄4 | 3+1⁄2 | 3+3⁄4 | 4 | 4+1⁄4 | 4+1⁄2 | 4+3⁄4 | 5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | 1.0 | 1.1 | 1.2 | 1.3 | 1.4 | 1.5 | 1.7 | 1.8 | 2 | 2.2 | 2.4 | 2.6 | 2.8 | 3.1 | 3.3 | 3.7 | 4 | 4.4 | 4.8 | 5.2 | 5.6 |

| AV | 5 | 5+1⁄4 | 5+1⁄2 | 5+3⁄4 | 6 | 6+1⁄4 | 6+1⁄2 | 6+3⁄4 | 7 | 7+1⁄4 | 7+1⁄2 | 7+3⁄4 | 8 | 8+1⁄4 | 8+1⁄2 | 8+3⁄4 | 9 | 9+1⁄4 | 9+1⁄2 | 9+3⁄4 | 10 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | 5.6 | 6.2 | 6.7 | 7.3 | 8 | 8.7 | 9.5 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 19 | 21 | 22 | 25 | 27 | 29 | 32 |

Effect on exposure

[edit]Camera equation

[edit]Upon taking a photograph, the exposure H received by the surface of the film or sensor is defined as

where E is the illuminance falling on that surface and t is the exposure time. The illuminance in turn depends on the brightness of the subject being photographed, and on the aperture of the lens. If we assume the lens has no transmission losses and is focused at infinity, the image-plane illuminance is:[10][11]

where L is the subject luminance (an objective measure of its brightness).

If the lens is focused at close range, the illuminance is lower, and this can be accounted for by replacing the f-number with the so-called “working f-number”. In the same vein, if the transmission losses cannot be neglected, the f-number should be replaced by the T-stop.

Working f-number

[edit]The f-number accurately describes the light-gathering ability of a lens only for objects an infinite distance away.[12] This limitation is typically ignored in photography, where f-number is often used regardless of the distance to the object. In optical design, an alternative is often needed for systems where the object is not far from the lens. In these cases the working f-number is used. The working f-number Nw is given by:[12]

where N is the uncorrected f-number, NAi is the image-space numerical aperture of the lens, is the absolute value of the lens's magnification for an object a particular distance away, and P is the pupil magnification. Since the pupil magnification is seldom known it is often assumed to be 1, which is the correct value for all symmetric lenses.

In photography this means that as one focuses closer, the lens's effective aperture becomes smaller, making the exposure darker. The working f-number is often described in photography as the f-number corrected for lens extensions by a bellows factor. This is of particular importance in macro photography.

T-stop

[edit]A T-stop (for transmission stops, by convention written with capital letter T) is an f-number adjusted to account for light transmission efficiency (transmittance). A lens with a T-stop of N projects an image of the same brightness as an ideal lens with 100% transmittance and an f-number of N. A particular lens's T-stop, T, is given by dividing the f-number by the square root of the transmittance of that lens: For example, an f/2.0 lens with transmittance of 75% has a T-stop of 2.3: Since real lenses have transmittances of less than 100%, a lens's T-stop number is always greater than its f-number.[13]

With 8% loss per air-glass surface on lenses without coating, multicoating of lenses is the key in lens design to decrease transmittance losses of lenses. Some reviews of lenses do measure the T-stop or transmission rate in their benchmarks.[14][15] T-stops are sometimes used instead of f-numbers to more accurately determine exposure, particularly when using external light meters.[16] Lens transmittances of 60%–95% are typical.[17] T-stops are often used in cinematography, where many images are seen in rapid succession and even small changes in exposure will be noticeable. Cinema camera lenses are typically calibrated in T-stops instead of f-numbers.[16] In still photography, without the need for rigorous consistency of all lenses and cameras used, slight differences in exposure are less important; however, T-stops are still used in some kinds of special-purpose lenses such as Smooth Trans Focus lenses by Minolta and Sony.

H-stop

[edit]An H-stop (for hole, by convention written with capital letter H) is an f-number equivalent for effective exposure based on the area covered by the holes in the diffusion discs or sieve aperture found in Rodenstock Imagon lenses.

ASA/ISO numbers

[edit]Photographic film's and electronic camera sensor's sensitivity to light is often specified using ASA/ISO numbers. Both systems have a linear number where a doubling of sensitivity is represented by a doubling of the number, and a logarithmic number. In the ISO system, a 3° increase in the logarithmic number corresponds approximately to a doubling of sensitivity. Doubling or halving the sensitivity is equal to a difference of one T-stop in terms of light transmittance.

Gain

[edit]

Most electronic cameras allow the user to adjust the amplification of the signal coming from the image sensor. This amplification is usually called gain and is measured in decibels. A 6 dB of gain is roughly equivalent to one T-stop in terms of light transmittance. Many camcorders have a unified control over the lens f-number and gain. In this case, starting from (arbitrarily defined) zero gain and a fully open iris, one can either increase the f-number by reducing the iris size while gain remains zero, or increase the gain while the iris remains fully open.

Sunny 16 rule

[edit]An example of the use of f-numbers in photography is the sunny 16 rule: an approximately correct exposure will be obtained on a sunny day by using an aperture of f/16 and the shutter speed closest to the reciprocal of the ISO speed of the film; for example, using ISO 200 film, an aperture of f/16 and a shutter speed of 1⁄200 second. The f-number may then be adjusted downwards for situations with lower light. Selecting a lower f-number is "opening up" the lens. Selecting a higher f-number is "closing" or "stopping down" the lens.

Effects on image sharpness

[edit]

Depth of field increases with f-number, as illustrated in the image here. This means that photographs taken with a low f-number (large aperture) will tend to have subjects at one distance in focus, with the rest of the image (nearer and farther elements) out of focus. This is frequently used for nature photography and portraiture because background blur (the aesthetic quality known as 'bokeh') can be aesthetically pleasing and puts the viewer's focus on the main subject in the foreground. The depth of field of an image produced at a given f-number is dependent on other parameters as well, including the focal length, the subject distance, and the format of the film or sensor used to capture the image. Depth of field can be described as depending on just angle of view, subject distance, and entrance pupil diameter (as in von Rohr's method). As a result, smaller formats will have a deeper field than larger formats at the same f-number for the same distance of focus and same angle of view since a smaller format requires a shorter focal length (wider angle lens) to produce the same angle of view, and depth of field increases with shorter focal lengths. Therefore, reduced–depth-of-field effects will require smaller f-numbers (and thus potentially more difficult or complex optics) when using small-format cameras than when using larger-format cameras.

Beyond focus, image sharpness is related to f-number through two different optical effects: aberration, due to imperfect lens design, and diffraction which is due to the wave nature of light.[18] The blur-optimal f-stop varies with the lens design. For modern standard lenses having six or seven elements, the sharpest image is often obtained around f/5.6–f/8, while for older standard lenses having only four elements (Tessar formula) stopping to f/11 will give the sharpest image.[citation needed] The larger number of elements in modern lenses allow the designer to compensate for aberrations, allowing the lens to give better pictures at lower f-numbers. At small apertures, depth of field and aberrations are improved, but diffraction creates more spreading of the light, causing blur.

Light falloff is also sensitive to f-stop. Many wide-angle lenses will show a significant light falloff (vignetting) at the edges for large apertures.

Photojournalists have a saying, "f/8 and be there", meaning that being on the scene is more important than worrying about technical details. Practically, f/8 (in 35 mm and larger formats) allows adequate depth of field and sufficient lens speed for a decent base exposure in most daylight situations.[19]

Human eye

[edit]

Computing the f-number of the human eye involves computing the physical aperture and focal length of the eye. Typically, the pupil can dilate to be as large as 6–7 mm in darkness, which translates into the maximal physical aperture. Some individuals' pupils can dilate to over 9 mm wide.

The f-number of the human eye varies from about f/8.3 in a very brightly lit place to about f/2.1 in the dark.[20] Computing the focal length requires that the light-refracting properties of the liquids in the eye be taken into account. Treating the eye as an ordinary air-filled camera and lens results in an incorrect focal length and f-number.

Focal ratio in telescopes

[edit]

In astronomy, the f-number is commonly referred to as the focal ratio (or f-ratio) notated as . It is still defined as the focal length of an objective divided by its diameter or by the diameter of an aperture stop in the system:

Even though the principles of focal ratio are always the same, the application to which the principle is put can differ. In photography the focal ratio varies the focal-plane illuminance (or optical power per unit area in the image) and is used to control variables such as depth of field. When using an optical telescope in astronomy, there is no depth of field issue, and the brightness of stellar point sources in terms of total optical power (not divided by area) is a function of absolute aperture area only, independent of focal length. The focal length controls the field of view of the instrument and the scale of the image that is presented at the focal plane to an eyepiece, film plate, or CCD.

For example, the SOAR four-meter telescope has a small field of view (about f/16) which is useful for stellar studies. The LSST 8.4 m telescope, which will cover the entire sky every three days, has a very large field of view. Its short 10.3 m focal length (f/1.2) is made possible by an error correction system which includes secondary and tertiary mirrors, a three element refractive system and active mounting and optics.[21]

History

[edit]The system of f-numbers for specifying relative apertures evolved in the late nineteenth century, in competition with several other systems of aperture notation.

Origins of relative aperture

[edit]In 1867, Sutton and Dawson defined "apertal ratio" as essentially the reciprocal of the modern f-number. In the following quote, an "apertal ratio" of "1⁄24" is calculated as the ratio of 6 inches (150 mm) to 1⁄4 inch (6.4 mm), corresponding to an f/24 f-stop:

In every lens there is, corresponding to a given apertal ratio (that is, the ratio of the diameter of the stop to the focal length), a certain distance of a near object from it, between which and infinity all objects are in equally good focus. For instance, in a single view lens of 6-inch focus, with a 1⁄4 in. stop (apertal ratio one-twenty-fourth), all objects situated at distances lying between 20 feet from the lens and an infinite distance from it (a fixed star, for instance) are in equally good focus. Twenty feet is therefore called the 'focal range' of the lens when this stop is used. The focal range is consequently the distance of the nearest object, which will be in good focus when the ground glass is adjusted for an extremely distant object. In the same lens, the focal range will depend upon the size of the diaphragm used, while in different lenses having the same apertal ratio the focal ranges will be greater as the focal length of the lens is increased. The terms 'apertal ratio' and 'focal range' have not come into general use, but it is very desirable that they should, in order to prevent ambiguity and circumlocution when treating of the properties of photographic lenses.[22]

In 1874, John Henry Dallmeyer called the ratio the "intensity ratio" of a lens:

The rapidity of a lens depends upon the relation or ratio of the aperture to the equivalent focus. To ascertain this, divide the equivalent focus by the diameter of the actual working aperture of the lens in question; and note down the quotient as the denominator with 1, or unity, for the numerator. Thus to find the ratio of a lens of 2 inches diameter and 6 inches focus, divide the focus by the aperture, or 6 divided by 2 equals 3; i.e., 1⁄3 is the intensity ratio.[23]

Although he did not yet have access to Ernst Abbe's theory of stops and pupils,[24] which was made widely available by Siegfried Czapski in 1893,[25] Dallmeyer knew that his working aperture was not the same as the physical diameter of the aperture stop:

It must be observed, however, that in order to find the real intensity ratio, the diameter of the actual working aperture must be ascertained. This is easily accomplished in the case of single lenses, or for double combination lenses used with the full opening, these merely requiring the application of a pair of compasses or rule; but when double or triple-combination lenses are used, with stops inserted between the combinations, it is somewhat more troublesome; for it is obvious that in this case the diameter of the stop employed is not the measure of the actual pencil of light transmitted by the front combination. To ascertain this, focus for a distant object, remove the focusing screen and replace it by the collodion slide, having previously inserted a piece of cardboard in place of the prepared plate. Make a small round hole in the centre of the cardboard with a piercer, and now remove to a darkened room; apply a candle close to the hole, and observe the illuminated patch visible upon the front combination; the diameter of this circle, carefully measured, is the actual working aperture of the lens in question for the particular stop employed.[23]

This point is further emphasized by Czapski in 1893.[25] According to an English review of his book, in 1894, "The necessity of clearly distinguishing between effective aperture and diameter of physical stop is strongly insisted upon."[26]

J. H. Dallmeyer's son, Thomas Rudolphus Dallmeyer, inventor of the telephoto lens, followed the intensity ratio terminology in 1899.[27]

Aperture numbering systems

[edit]

At the same time, there were a number of aperture numbering systems designed with the goal of making exposure times vary in direct or inverse proportion with the aperture, rather than with the square of the f-number or inverse square of the apertal ratio or intensity ratio. But these systems all involved some arbitrary constant, as opposed to the simple ratio of focal length and diameter.

For example, the Uniform System (U.S.) of apertures was adopted as a standard by the Photographic Society of Great Britain in the 1880s. Bothamley in 1891 said "The stops of all the best makers are now arranged according to this system."[28] U.S. 16 is the same aperture as f/16, but apertures that are larger or smaller by a full stop use doubling or halving of the U.S. number; for example f/11 is U.S. 8 and f/8 is U.S. 4. The exposure time required is directly proportional to the U.S. number. Eastman Kodak used U.S. stops on many of their cameras at least in the 1920s.

By 1895, Hodges contradicts Bothamley, saying that the f-number system has taken over: "This is called the f/x system, and the diaphragms of all modern lenses of good construction are so marked."[29]

Here is the situation as seen in 1899:

Piper in 1901[30] discusses five different systems of aperture marking: the old and new Zeiss systems based on actual intensity (proportional to reciprocal square of the f-number); and the U.S., Continental or International System (C.I.), and the Dallmeyer system, based on exposure (proportional to square of the f-number). He calls the f-number the "ratio number", "aperture ratio number", and "ratio aperture". He calls expressions like f/8 the "fractional diameter" of the aperture.

Beck and Andrews in 1902 talk about the Royal Photographic Society standard of f/4, f/5.6, f/8, f/11.3, etc.[31] The Royal Photographic Society had changed their name and moved off of the Uniform System some time between 1895 and 1902.

Typographical standardization

[edit]

By 1920, the term f-number appeared in books both as F number and f/number. In modern publications, the forms f-number and f number are more common, though the earlier forms, as well as F-number are still found in a few books; not uncommonly, the initial lower-case f in f-number or f/number is set in a hooked italic form: ƒ.[32]

Notations for f-numbers were also quite variable in the early part of the twentieth century. They were sometimes written with a capital F,[33] sometimes with a dot (period) instead of a slash,[34] and sometimes set as a vertical fraction.[35]

The 1961 ASA standard PH2.12-1961 American Standard General-Purpose Photographic Exposure Meters (Photoelectric Type) specifies that "The symbol for relative apertures shall be ƒ/ or ƒ: followed by the effective ƒ-number." They show the hooked italic 'ƒ' not only in the symbol, but also in the term f-number, which today is more commonly set in an ordinary non-italic face.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b Smith, Warren Modern Optical Engineering, 4th Ed., 2007 McGraw-Hill Professional, p. 183.

- ^ Hecht, Eugene (1987). Optics (2nd ed.). Addison Wesley. p. 152. ISBN 0-201-11609-X.

- ^ Greivenkamp, John E. (2004). Field Guide to Geometrical Optics. SPIE Field Guides vol. FG01. Bellingham, Wash: SPIE. p. 29. ISBN 9780819452948. OCLC 53896720.

- ^ Smith, Warren Modern Lens Design 2005 McGraw-Hill.

- ^ ISO, Photography—Apertures and related properties pertaining to photographic lenses—Designations and measurements, ISO 517:2008

- ^ See Area of a circle.

- ^ Harry C. Box (2003). Set lighting technician's handbook: film lighting equipment, practice, and electrical distribution (3rd ed.). Focal Press. ISBN 978-0-240-80495-8.

- ^ Paul Kay (2003). Underwater photography. Guild of Master Craftsman. ISBN 978-1-86108-322-7.

- ^ David W. Samuelson (1998). Manual for cinematographers (2nd ed.). Focal Press. ISBN 978-0-240-51480-2.

- ^ Jack (2023-02-26). "Angles and the Camera Equation". Strolls with my Dog. Retrieved 2025-07-22.

- ^ Greivenkamp, John E. (2019). "OPTI-502 Optical Design and Instrumentation – Radiative Transfer" (PDF). University of Arizona College of Optical Sciences. University of Arizona. Retrieved 2025-07-22.

- ^ a b Greivenkamp, John E. (2004). Field Guide to Geometrical Optics. SPIE Field Guides vol. FG01. SPIE. ISBN 0-8194-5294-7. p. 29.

- ^ Transmission, light transmission Archived 2021-05-08 at the Wayback Machine, DxOMark

- ^ Sigma 85mm F1.4 Art lens review: New benchmark Archived 2018-01-04 at the Wayback Machine, DxOMark

- ^ Colour rendering in binoculars and lenses - Colours and transmission Archived 2018-01-04 at the Wayback Machine, LensTip.com

- ^ a b "Kodak Motion Picture Camera Films". Eastman Kodak. November 2000. Archived from the original on 2002-10-02. Retrieved 2007-09-02.

- ^ "Marianne Oelund, "Lens T-stops", dpreview.com, 2009". Archived from the original on 2012-11-10. Retrieved 2013-01-11.

- ^ Michael John Langford (2000). Basic Photography. Focal Press. ISBN 0-240-51592-7.

- ^ Levy, Michael (2001). Selecting and Using Classic Cameras: A User's Guide to Evaluating Features, Condition & Usability of Classic Cameras. Amherst Media, Inc. p. 163. ISBN 978-1-58428-054-5.

- ^ Hecht, Eugene (1987). Optics (2nd ed.). Addison Wesley. ISBN 0-201-11609-X. Sect. 5.7.1

- ^ Charles F. Claver; et al. (2007-03-19). "LSST Reference Design" (PDF). LSST Corporation: 45–50. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2009-03-06. Retrieved 2011-01-10.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Thomas Sutton and George Dawson, A Dictionary of Photography, London: Sampson Low, Son & Marston, 1867, (p. 122).

- ^ a b John Henry Dallmeyer, Photographic Lenses: On Their Choice and Use – Special Edition Edited for American Photographers, pamphlet, 1874.

- ^ Southall, James P. C. (1910). The Principles and Methods of Geometrical Optics: Especially as applied to the theory of optical instruments. Macmillan. p. 537.

- ^ a b Siegfried Czapski, Theorie der optischen Instrumente, nach Abbe, Breslau: Trewendt, 1893.

- ^ Henry Crew, "Theory of Optical Instruments by Dr. Czapski," in Astronomy and Astro-physics XIII pp. 241–243, 1894.

- ^ Thomas R. Dallmeyer, Telephotography: An elementary treatise on the construction and application of the telephotographic lens, London: Heinemann, 1899.

- ^ C. H. Bothamley, Ilford Manual of Photography, London: Britannia Works Co. Ltd., 1891.

- ^ John A. Hodges, Photographic Lenses: How to Choose, and How to Use, Bradford: Percy Lund & Co., 1895.

- ^ Piper, C. Welborne (1901). A First Book of the Lens: An Elementary Treatise on the Action and Use of the Photographic Lens. London: Hazell, Watson, and Viney. p. 101. "There are three systems of classification according to exposure; one known as the Uniform System (U.S.) of the Royal Photographic Society, in which an aperture of f/4 is taken as requiring a unit exposure. Another is the Dallmeyer System, in which f3.16 [sic] gives a unit exposure. The third is the Continental or International System, also known as the C.I. system, in which f/10 requires a unit exposure. The two former are now practically obsolete, but the third is still in use. Then there are two Zeiss systems, in which apertures are classified according to intensity, f/100 having a unit intensity in the 'old' system, and f/50 in the 'new' system."

- ^ Beck, Conrad; Andrews, Herbert (1902). "Section IV: Properties of Lenses; 3. Rapidity". Photographic Lenses: A Simple Treatise (2nd ed.). London: R. & J. Beck Ltd. pp. 96–107.

- ^ Google search

- ^ Ives, Herbert Eugene (1920). Airplane Photography (Google). Philadelphia: J. B. Lippincott. p. 61. ISBN 9780598722225. Retrieved 2007-03-12.

{{cite book}}: ISBN / Date incompatibility (help) - ^ Mees, Charles Edward Kenneth (1920). The Fundamentals of Photography. Eastman Kodak. p. 28. Retrieved 2007-03-12.

- ^ Derr, Louis (1906). Photography for Students of Physics and Chemistry (Google). London: Macmillan. p. 83. Retrieved 2007-03-12.

External links

[edit]F-number

View on GrokipediaDefinition and Notation

Notation

The f-number is denoted as , where represents the focal length of the lens and is the numerical f-number value. This notation expresses the f-number as a ratio, indicating that the diameter of the aperture opening is the focal length divided by . For example, f/2.8 specifies an aperture diameter equal to the focal length divided by 2.8.[1][4] The f-number is synonymous with the term relative aperture, which quantifies the proportion of the focal length to the aperture diameter, yielding a dimensionless measure of the lens opening relative to its optical design.[5][6] Historically, the notation for the f-number has included variations such as "f/", "f-", or "1:" in early photographic contexts to denote the relative aperture ratio.[6] The mathematical formulation derives the f-number as , where is the diameter of the entrance pupil, standardizing the representation across different lens focal lengths.[1][3]Basic Principles

The f-number, denoted as , quantifies the relative aperture of an optical system by defining the ratio of the lens's focal length to the diameter of the entrance pupil, expressed as .[3] This ratio determines the size of the cone of light that converges onto the image plane, where a smaller corresponds to a wider cone and thus greater light collection efficiency.[1] In practical notation, it is often written as f/N, such as f/2.8, to indicate the system's light-gathering capability.[1] The illuminance, or light intensity, on the image plane follows the inverse square law in relation to the f-number, with intensity proportional to .[7] This means that halving the f-number (e.g., from f/4 to f/2) quadruples the light intensity, as the area of the aperture scales with the square of its diameter while the focal length remains fixed.[3] Unlike absolute aperture size, which varies with lens design, the f-number provides scale-invariance across different focal lengths, allowing consistent comparison of light-gathering ability for lenses of varying sizes.[3] For instance, a 50 mm lens at f/2 and a 100 mm lens at f/2 both deliver the same relative light intensity per unit area on the image plane, independent of their physical scale.[1] From a physics perspective, larger apertures (smaller ) enhance light collection but increase the angle of incidence for marginal rays, exacerbating optical aberrations such as spherical aberration, which degrades image sharpness at the edges.[8] This trade-off necessitates careful lens design to balance brightness with optical fidelity.[9]Aperture Scales

Full-Stop Scale

The full-stop scale for f-numbers constitutes a standardized series in photography and optics, where each increment doubles or halves the effective aperture area, resulting in a corresponding change in light intensity by a factor of two. This logarithmic progression ensures consistent exposure adjustments, with each step termed a "full stop." The scale originates from the need to quantify light transmission in a manner that aligns with the quadratic relationship between aperture diameter and area. The conventional full-stop sequence is f/1, f/1.4, f/2, f/2.8, f/4, f/5.6, f/8, f/11, f/16, f/22, f/32, and continues similarly for higher values.[10] These values approximate powers of , reflecting the geometric nature of the scale. The derivation stems from the f-number definition, , where is the focal length and is the aperture diameter. Light intensity is proportional to the aperture area , so . To halve the light (one full stop), the new f-number satisfies , yielding . Thus, each successive f-number is the previous multiplied by , halving transmission while maintaining the proportional exposure change.[10] In practice, photographic lenses often feature maximum apertures aligned with this scale for optimal performance; for instance, fast prime lenses commonly achieve f/1.4, enabling superior low-light capability and shallow depth of field, while professional zoom lenses frequently max out at f/2.8.[11] This full-stop framework underpins finer subdivisions like half-stops for precise control in contemporary systems.Half-Stop Scale

The half-stop scale extends the full-stop f-number series by inserting intermediate values that enable more precise exposure control. Typical half-stop insertions include f/1.2 between f/1.0 and f/1.4, f/1.7 between f/1.4 and f/2.0, f/2.5 between f/2.0 and f/2.8, f/3.5 between f/2.8 and f/4.0, and f/6.3 between f/5.6 and f/8.0.[12] These half-stops are achieved by multiplying the preceding f-number by , which corresponds to a change in light transmission by a factor of , equivalent to approximately a 41% adjustment in exposure value.[12] The half-stop scale is widely used in consumer cameras to provide balanced, incremental exposure adjustments that closely approximate the granularity of analog exposure metering in traditional film systems.[12] Some manual lenses feature aperture rings with clicks at half-stop positions for tactile reference, though many classic designs, such as Nikon AI-series primes, mark only full stops and allow manual positioning between them.[13]Third-Stop and Quarter-Stop Scales

The third-stop scale provides finer granularity than half-stop increments, dividing each full stop into three equal parts for more precise aperture adjustments in modern photography. This scale uses a multiplier of applied to the f-number for each step, resulting in approximately a 26% change in light transmission per increment, as the area of the aperture varies by .[14] Common examples include f/2.0, f/2.2, f/2.5, and f/2.8, allowing photographers to fine-tune exposure without large jumps in depth of field or light intake.[15] The quarter-stop scale offers even greater precision, subdividing a full stop into four parts. Increments typically follow a multiplier of for the f-number, yielding about an 18.9% light change per step via . Some cameras use internal 1/8-stop steps to approximate 1/3-stop settings for more accurate electronic control, though user-selectable adjustments are usually limited to 1/3-stop in most high-end DSLRs and mirrorless systems as of 2025. Nominal values often round, such as f/2.2 for positions approximating both third- and quarter-stops due to manufacturing conventions.[16] These scales enhance digital workflows by enabling subtle adjustments that align closely with in-camera histograms, reducing the risk of clipping highlights or shadows during capture. In RAW processing, the finer steps support post-production corrections with minimal noise introduction, as initial exposures can be optimized more accurately before editing.[12][4] The adoption of third-stop scales evolved with the shift from film to digital photography, where coarser full- or half-stop markings sufficed for film's latitude, but digital sensors demanded tighter control for dynamic range management.[17]Exposure Calculation

Camera Exposure Equation

The camera exposure equation quantifies the relationship between the f-number, shutter speed, and ISO sensitivity to determine the total light exposure on the image sensor or film. In its logarithmic form, known as the exposure value (EV) at ISO 100 (EV_{100}), the equation is given by where is the f-number and is the shutter speed in seconds.[18] This formulation links the f-number directly to light accumulation, as EV represents the base-2 logarithm of the exposure, with each unit corresponding to a doubling or halving of the light reaching the sensor at ISO 100. For other ISO values , the adjusted exposure value is , allowing consistent exposure across sensitivities. The squared term in the equation arises from the geometry of the lens aperture. The f-number is defined as the ratio of the lens focal length to the aperture diameter , so and . The aperture area, which determines the light-gathering capacity, is proportional to . Thus, the illuminance on the sensor is inversely proportional to , reflecting how smaller apertures (higher ) reduce light intake quadratically.[19][18] A one-stop change in the f-number, which multiplies or divides by (approximately 1.414), doubles or halves the aperture area and thus the light exposure, since . This adjustment compensates exactly for a one-stop change in shutter speed (doubling or halving ) or ISO sensitivity (doubling or halving the ISO value), maintaining constant EV and proper exposure. For instance, increasing from f/5.6 to f/8 (a one-stop reduction in light) requires halving (e.g., from 1/60 s to 1/30 s) or doubling ISO (e.g., from 100 to 200) to preserve the same exposure level.[19][18][20] In practice, for a typical midday outdoor scene at ISO 100, a balanced exposure might use f/8 and 1/125 s, yielding EV_{100} ≈ 13, as .[18][20]Transmission Adjustment (T-Number)

The effective f-number accounting for transmission, often called the T-number, adjusts the marked f-number for actual light transmission through a lens, which is typically less than 100% due to absorption and reflection losses. It is defined as , where is the marked f-number and is the lens transmission factor representing the fraction of incident light that reaches the image plane.[10] Lens transmission is reduced primarily by reflections at air-glass interfaces, with each uncoated surface reflecting about 4-5% of light, compounded by the number of elements in the lens design; absorption in glass materials contributes minimally in the visible spectrum. Anti-reflective coatings mitigate these losses by reducing surface reflectivity to below 1% per interface, while increased element counts in complex lenses (e.g., zooms with 10+ elements) can still lower overall if coatings are suboptimal. For instance, a lens marked as f/2.8 with (common for mid-20th-century designs) has a T-number of approximately f/3.2, meaning it transmits about 23% less light than an ideal lens at the same marked aperture.[21][22] Typical transmission factors for photographic lenses range from 0.7 to 0.9, depending on design complexity and coating quality, with simpler prime lenses often achieving higher values than zooms. Multi-layer anti-reflective coatings, introduced in the early 1970s by manufacturers like Asahi Pentax with their Super-Multi-Coating (SMC), dramatically improved transmission by optimizing reflectivity across wavelengths, boosting to over 95% in modern high-end lenses and reducing flare for better image contrast.[23]Film and Sensor Sensitivity

The ISO/ASA film speed system, standardized by the American National Standards Institute (ANSI) in 1974 through adoption of ISO 6, defines sensitivity such that each doubling of the ISO number represents a one-stop increase in film speed, meaning the film requires half the exposure to produce the same density.[24] For example, ISO 100 film is twice as sensitive as ISO 50, allowing photographers to adjust exposure by changing the f-number, shutter speed, or ISO to maintain proper illumination on the film plane. This arithmetic progression aligns directly with f-number stops, where opening the aperture one stop (e.g., from f/8 to f/5.6) doubles the light intake, compensating for a halving of sensitivity when shifting from ISO 100 to ISO 200.[24] A practical heuristic for exposure in bright conditions is the Sunny 16 rule, which states that on a clear, sunny day at midday, correct exposure for a subject in full sunlight can be achieved by setting the aperture to f/16 and the shutter speed to the reciprocal of the ISO value (e.g., 1/100 second for ISO 100).[25] This rule ties the f-number directly to scene luminance and film sensitivity, providing a quick estimate without a light meter; for instance, with ISO 400 film, the shutter speed would be 1/400 second at f/16, assuming EV 15 lighting typical of bright sun.[25] It integrates with the broader camera exposure equation by balancing f-number against ISO and shutter speed for scenes around 1000 lux illuminance. In digital sensors, ISO adjustments primarily involve analog gain applied after photon capture but before analog-to-digital conversion, amplifying the signal to simulate higher sensitivity while introducing noise from read-out electronics and photon shot noise.[26] Unlike film, where ISO is fixed by emulsion chemistry, digital gain boosts at higher settings (e.g., from ISO 100 to 200) effectively double the output but amplify thermal and pattern noise, reducing dynamic range; for example, ISO 800 may yield usable images in low light but with visible grain compared to base ISO 100.[26] Exposure adjustments for accessories like neutral density (ND) filters or bellows extension scale the effective f-number to account for reduced light transmission or increased lens-to-sensor distance. ND filters, rated in stops (e.g., a 3-stop filter halves light thrice, requiring a three-stop wider aperture like f/8 to f/2.8 for equivalent exposure), maintain the marked f-number while compensating via shutter speed or ISO.[27] Bellows factor in macro or large-format photography increases the working f-number by the factor (1 + e/f), where e is the extension and f the focal length (e.g., at 1:1 magnification where e = f, the working f-number doubles, effectively halving light and raising f/8 to f/16 equivalent), necessitating longer exposures or higher ISO to preserve image density.[28]Image Quality Effects

Depth of Field

The depth of field (DoF) refers to the range of distances in object space over which objects appear acceptably sharp in an image, determined primarily by the lens's f-number, focal length, subject distance, and the acceptable circle of confusion. A larger f-number, corresponding to a smaller aperture diameter, increases the DoF by narrowing the cone of light rays passing through the lens, which reduces the rate at which defocus blur accumulates away from the focal plane.[29][30] An approximate formula for the total DoF when the subject distance is much greater than the focal length is given by where is the f-number, is the circle of confusion diameter (typically around 0.03 mm for 35 mm format sensors), is the subject distance, and is the focal length.[31] This approximation highlights the direct proportionality of DoF to , showing how stopping down the aperture extends the sharp focus range. The hyperfocal distance , defined as the closest focusing distance at which the DoF extends to infinity, is calculated as Focusing at maximizes the DoF for scenes with distant subjects, such as landscapes, where everything from approximately to infinity remains sharp.[32][31] In practice, photographers select smaller f-numbers like f/2.8 to achieve shallow DoF for isolating subjects in portraits, creating pronounced background blur, while larger f-numbers such as f/11 are used for expansive landscapes to maintain sharpness across foreground and background elements.[33]Diffraction and Sharpness

In optical imaging, diffraction imposes a fundamental limit on the sharpness of an image formed by a lens, particularly as the aperture is stopped down to higher f-numbers. When light passes through a circular aperture, it does not converge perfectly to a point but instead spreads out due to wave interference, forming a central bright spot known as the Airy disk surrounded by concentric rings. The radius of this Airy disk, which represents the smallest resolvable detail in a diffraction-limited system, is given by the formula , where is the wavelength of light (typically around 550 nm for visible green light) and is the f-number of the lens.[34] As increases, the Airy disk enlarges proportionally, causing adjacent points in the subject to blur together and reducing overall image resolution. This effect becomes noticeable at small apertures, such as f/16 or higher, where the diffraction blur can exceed other optical imperfections like lens aberrations.[35] For typical 35mm full-frame sensors, the optimal f-number for maximum sharpness often falls in the range of f/8 to f/11, where lens aberrations are minimized while diffraction remains negligible. At these settings, the system achieves peak resolution by balancing the reduction in spherical aberration and field curvature from stopping down with the onset of diffraction. Beyond f/11, diffraction progressively dominates, leading to a measurable decline in fine detail, though modern image processing can partially mitigate this in post-production.[35][36] Modulation transfer function (MTF) curves illustrate this tradeoff quantitatively, plotting contrast retention (modulation) against spatial frequency (line pairs per millimeter) for different f-numbers. These curves typically peak in resolution around f/5.6 to f/8 for high-quality lenses, with a gradual decline at higher f-numbers as diffraction attenuates high-frequency details. For instance, an excellent 35mm lens might resolve 60 lp/mm at 50% MTF at f/8, dropping to about 40 lp/mm at f/16 due to the expanding Airy disk overlapping more closely spaced lines.[35][37] The impact of diffraction is more pronounced in systems with smaller pixels, such as those in smartphone cameras, where pixel pitches are often 1-2 μm. Here, the diffraction limit is reached at lower f-numbers like f/2.8 to f/4, as the Airy disk size quickly exceeds the pixel dimensions, limiting the effective resolution regardless of sensor megapixel count. In contrast, larger full-frame sensors with 4-6 μm pixels can tolerate higher f-numbers before diffraction significantly degrades sharpness.[38][39]Specialized Applications

T-Stops in Cinematography

In cinematography, T-stops provide a measure of the actual light transmission through a lens, accounting for losses due to absorption, reflection, and scattering in the glass elements, which ensures precise and consistent exposure across multiple shots and lenses.[40] The T-number relates to the f-number by the formula , where is the f-number and is the transmittance (the fraction of incident light passing through the lens), typically ranging from 0.70 to 0.90 for modern cinema lenses.[41] This adjustment results in T-stops being approximately 1/3 to 1/2 stop slower than corresponding f-stops, as real-world light losses reduce effective illumination by 10–30% compared to the theoretical aperture.[42] Cinema lenses are specifically calibrated and marked in T-stops—such as T/2.0 or T/4—for use in film and video production, enabling cinematographers to match exposures seamlessly when changing lenses, using multiple cameras, or editing sequences where even minor variations would be visible.[43] This transmission-based marking originated as a standard in motion picture optics to prioritize exposure uniformity over theoretical calculations.[40] While general lens transmission affects all photography, T-stops extend this principle into production-specific calibration for consistent results in dynamic shooting environments.[41]Focal Ratio in Astronomy

In astronomy, the focal ratio, often denoted as f/D, represents the ratio of a telescope's focal length (f) to the diameter of its primary mirror or objective lens (D). This parameter, equivalent to the f-number in optical systems, determines the telescope's speed and field of view. For instance, a wide-field telescope designed for observing extended objects like galaxies might have a focal ratio of f/8 or lower, providing a broader sky coverage, while planetary telescopes often feature slower ratios such as f/20, which yield higher magnification and finer detail resolution on small, bright targets.[44][2] The focal ratio significantly influences exposure times in astronomical imaging and observation. Faster focal ratios (lower f/D values) concentrate light over a shorter focal length, allowing more photons to reach the detector or eyepiece per unit time, which reduces the required exposure duration for faint objects. Conversely, slower ratios demand longer exposures to achieve comparable signal-to-noise ratios, as the light is spread over a longer path; however, they offer improved sampling of fine details, minimizing issues like undersampling in high-resolution planetary or lunar imaging. This trade-off is particularly relevant in astrophotography, where faster systems enable shorter sub-exposures to mitigate atmospheric turbulence.[45][46] Accessories such as eyepieces and Barlow lenses alter the effective focal ratio experienced by the observer or imager. An eyepiece primarily affects magnification by dividing the telescope's focal length by its own, but the base focal ratio remains unchanged; however, it influences the exit pupil size and overall image brightness. A Barlow lens, functioning as a diverging optic, increases the effective focal length—typically by a factor of 2x or more—thereby slowing the effective focal ratio (e.g., transforming an f/5 system to f/10), which enhances magnification but requires brighter conditions or longer exposures to maintain image quality. These adjustments are common in visual astronomy to optimize for specific targets without changing the telescope itself.[47][48] Modern catadioptric telescopes, combining refractive and reflective elements, have pushed focal ratios to exceptionally fast levels for astrophotography. Designs like the Celestron Rowsell-Allen Schmidt Astrograph (RASA) achieve f/2 ratios with apertures up to 11 inches, enabling wide-field imaging of nebulae and star clusters in significantly reduced exposure times compared to traditional refractors or reflectors. These systems prioritize light-gathering efficiency for deep-sky objects, often incorporating corrector plates to maintain edge-to-edge sharpness across large sensor formats.[49][50]Comparison to Human Eye

The human eye's optical system can be approximated using the f-number concept, where the effective f-number is the ratio of the eye's focal length to the diameter of the entrance pupil (the pupil). The focal length of the relaxed human eye is approximately 17 mm, while the pupil diameter ranges from about 2 mm in bright light to 8 mm in dim conditions. This yields an effective f-number of roughly f/8.5 during daylight viewing and f/2.1 in low-light scenarios.[51][52][53] The iris regulates pupil size to modulate light intake, analogous to a camera lens's adjustable aperture, enabling adaptation to varying illumination levels. Constriction in response to bright light occurs rapidly, peaking within 0.5 to 1 second, whereas dilation in darkness is slower, often requiring several seconds for initial changes and up to minutes for complete dark adaptation due to photochemical processes in the retina. In contrast, modern camera apertures adjust mechanically in fractions of a second, allowing faster exposure shifts without the biological delays inherent to the eye.[54] The depth of field in human vision—the range of distances appearing acceptably sharp—benefits from the eye's accommodation mechanism, which adjusts focus dynamically from near objects to infinity, extending beyond what a fixed-focus camera at equivalent f-numbers would achieve. Instantaneously, with a typical pupil size of 3–4 mm (f/4 to f/5.6), the sharp focus plane resembles an f/8 equivalent in photography, limited by optical aberrations and the eye's small circle of confusion. However, the brain enhances perceived depth of field by integrating information from rapid eye movements (saccades) and selectively filling perceptual gaps, creating an illusion of greater overall sharpness.[55][56] In low-light conditions, the dilated pupil (low f-number) minimizes diffraction effects, which would otherwise blur fine details as seen with high f-numbers in cameras; instead, night vision blur arises primarily from increased spherical aberrations due to the larger pupil and the reliance on rod cells, which provide lower resolution in the eye's periphery. This contrasts with bright-light viewing, where the constricted pupil (high f-number) introduces more diffraction but sharper central acuity through reduced aberrations.[57][58]Historical Development

Origins of Relative Aperture

The concept of relative aperture emerged in the mid-19th century as photographers and opticians sought to quantify the light-gathering efficiency of lenses independent of focal length, drawing from earlier optical traditions. In the nascent field of photography, apertures were initially determined empirically to balance exposure times with image clarity, laying the groundwork for more systematic approaches. The Daguerreotype process, publicly announced in 1839 by Louis Daguerre, exemplified this early empirical approach. Cameras for daguerreotypes featured fixed apertures sized by trial and error to suit the slow sensitivity of the silvered copper plates, often equivalent to modern f/14 to f/17 ratios, which allowed exposures of several minutes in bright light without a formalized relative measure.[59] These practical adjustments highlighted the need for a standardized way to compare lens performance across different focal lengths, leading to conceptual shifts by the 1860s. Influences from telescope optics further shaped these ideas, with Galileo Galilei's 1610 use of aperture stops in his refracting telescopes to minimize spherical aberration and enhance image sharpness providing an early model for controlling light cones in imaging systems.[60] This principle of restricting the aperture to optimize optical quality resonated in photography, where similar light bundle management became essential for reproducible results. A pivotal advancement came in 1867 with Thomas Sutton and George Dawson's A Dictionary of Photography, which defined the "apertal ratio" as the diameter of the aperture divided by the focal length—essentially the reciprocal of the modern f-number—allowing photographers to express lens speed relatively.[61] Building on this, William de Wiveleslie Abney's 1878 Treatise on Photography elaborated on relative aperture measures to guide exposure calculations and lens selection, emphasizing their role in achieving consistent photographic outcomes. These contributions established relative aperture as a foundational concept before the widespread adoption of formal f-number notation.Evolution of Numbering Systems

The f-number system, denoting the ratio of a lens's focal length to its aperture diameter, gained prominence in the early 20th century as manufacturers sought consistent methods for specifying light transmission across lenses of varying focal lengths. Carl Zeiss pioneered its widespread adoption with the introduction of the Unar lens design in 1899, which incorporated f-number markings to standardize aperture settings independent of focal length. This approach built on 19th-century concepts of relative aperture but marked the first practical implementation in commercial photographic lenses, enabling photographers to predict exposure outcomes more reliably regardless of lens type.[62] The system rapidly spread through influential European and American firms. Ernst Leitz, founder of what would become Leica, integrated f-numbers into their early microscope and camera objectives by the 1910s, aligning with the growing demand for precision optics in scientific and amateur photography. Similarly, Eastman Kodak transitioned to f-stops in their lens designs during the 1910s and 1920s, replacing inconsistent diameter-based markings on earlier models to facilitate universal exposure calculations. By the mid-1920s, Kodak had largely abandoned alternative scales, promoting f-numbers as the basis for interchangeable lens compatibility in their popular folding cameras.[63][64] Regional variations persisted, particularly in the United States, where the Uniform System (US)—established by the Royal Photographic Society in 1881—remained common into the early 20th century. Under this scheme, aperture numbers directly corresponded to relative exposure times, such that US 1 equated to an f/4 opening (requiring one unit of exposure time), US 2 to f/5.6, and US 4 to f/8, with each step doubling the exposure. This system, favored for its simplicity in calculating exposures without focal length considerations, was marked on many American lenses and Kodak products until the 1920s. However, as the f-number system's advantages in precision and international consistency became evident, the Uniform System was phased out by the 1930s, fully supplanted by f-stops in mainstream photography.[63][65] In the 1920s, advancements in exposure metering and shutter technology led to unified scales that integrated f-stops with shutter speeds, simplifying overall exposure determination. This era saw the development of exposure tables and early coupled systems where f-stop increments aligned with shutter speed doublings, laying groundwork for later logarithmic frameworks like the Exposure Value (EV) system introduced in the 1950s. These integrations allowed photographers to balance aperture and time for consistent results across diverse lighting conditions.[63] World War II accelerated the standardization of f-stops in military optics, as allied forces required interoperable sighting and reconnaissance equipment. The U.S. military's adoption of MIL-STD specifications for lenses emphasized f-number uniformity to ensure consistent performance in shared photographic and targeting systems, reducing errors in field operations across multinational units.[66]Standardization Efforts

The efforts to standardize f-number notation and its integration into exposure systems gained momentum in the mid-20th century through international bodies. In 1974, the International Organization for Standardization (ISO) introduced ISO 6:1974, which harmonized the American Standards Association (ASA) arithmetic scale and the Deutsche Industrie Norm (DIN) logarithmic scale for film speed into a single ISO system. This convergence simplified global exposure calculations by aligning film sensitivity ratings with f-stop apertures and shutter speeds, reducing inconsistencies in photographic practice across regions.[67][24] Typographical conventions for denoting f-numbers also underwent formalization during this period, shifting from earlier formats like colons (f:5.6) or parentheses to the slash notation (f/5.6), which improved readability in technical printing and lens markings by the 1970s. This change was driven by industry needs for consistent documentation in manuals and equipment labeling, ensuring universal interpretation of aperture values.[6] In the post-2000 digital era, ISO standards for camera performance, such as ISO 12232 for digital still camera sensitivity, have incorporated finer exposure increments, including third-stops for f-number adjustments (e.g., f/3.5 to f/4 as one-third stop). This update reflects advancements in sensor technology and allows precise control in digital specifications, aligning with the traditional f-stop scale while accommodating electronic adjustments.References

- https://camera-wiki.org/wiki/Le_Daguerreotype